ABSTRACT

This article investigates whether self-organized initiatives are able to undermine the underlying dynamics of spatial fragmentation in Brazilian metropolises by promoting social connections between groups that are extremely diverse. Since self-organized initiatives not only promote spatial connections but also social connections between different groups, the central question here is: To what extent can self-organized initiatives promote social connection in the public spaces of highly fragmented and unequal urban contexts? The analysis was based on data collected from 22 in-depth interviews with members of self-organized initiatives, experts as well as field observations during some actions of the initiatives. The interviews were conducted in Brasília, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo during two months of fieldwork. The results show that the self-organized initiatives studied were capable to mitigate conflicts and to create social connections. Nevertheless, it is still unclear how strong and long-lasting these social connections are.

1.1. Introduction

Brazilian metropolises are highly fragmented. Opportunity-led development has created a disconnected urban patchwork where walls and inequality reign. However, the barriers in fragmented cities go beyond the physical ones. Breaking down invisible walls and connecting spatially disconnected areas does not necessarily erode the social inequality behind them or promote social connections. The walls in Brazilian metropolises are also social (Cortes Citation2008). The result is that traditional urban policies often fail to confront the spatial fragmentation in Brazil. At the same time, it is also common to observe bottom-up, informal and self-organized initiatives in such fragmented contexts. These initiatives are abundant and range from housing construction to upgrading public spaces.

Self-organizing initiatives are not only often recognized as important in shaping the city, but they are frequently led or supported by planners. It is interesting to observe that planners are taking part in these movements and pushing their agendas forward. Understanding the participation of planners in self-organized initiatives was not the initial aim of this research; however, it became clear during the fieldwork that planners were playing a significant role. The reasons for planners joining these initiatives were not investigated in this thesis, as there is already research explaining why young planners are trying non-traditional paths of practice. According to Taşan-Kok and Oranje (Citation2017), young planners feel that it is necessary to explore new paths in order to express their ideological position and move beyond a purely technocratic function. This is mainly the result of a mismatch between the expectations of the profession created during their education and their professional practice after graduation. It seems that traditional top-down planning is failing to fulfil the aspirations of young planners in Brazil.

In this context, it is not clear how these informal, bottom-up and self-organized initiatives, supported by urban planners, are shaping the built environment. Aspects such as spatial fragmentation are being influenced by these initiatives, through building new social connections and increasing the level of integration. This article investigates whether these self-organized initiatives are able to undermine the underlying dynamics of spatial fragmentation in Brazilian metropolises by promoting social connections between groups that are extremely diverse. Since self-organized initiatives not only promote spatial connections but also social connections between different groups, the primary premise of this study is that they will have a positive impact on reducing the spatial fragmentation present in Brazilian metropolises. Therefore, the central question here is: To what extent can self-organized initiatives promote social connection in the public spaces of highly fragmented and unequal urban contexts?

To answer this question, the research used qualitative methods to understand the social dynamics in these self-organized initiatives. The analysis was based on data collected from 12 in-depth interviews with members of self-organized initiatives as well as field observations during some actions of the initiatives. Additionally, 10 in-depth interviews with public servants and experts were conducted to provide a complimentary perspective on these initiatives. The interviews were conducted in Brasília, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo during two months of fieldwork. These three cities were chosen because they are the three main metropolises of Brazil (according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) and have an abundant mix of self-organized initiatives. The results show that self-organized initiatives can create new social ties even in public spaces with patent social inequalities.

1.2. Theoretical explorations of spatial fragmentation and social connection

Spatial fragmentation is common in cities of the Global South, with many researchers focusing on understanding the phenomenon. While Balbo (Citation1993) and Çakir et al. (Citation2008) focused more on the physical and land use aspects of spatial fragmentation, Bayón and Saraví (Citation2013) addressed the cultural dimensions of fragmentation. In addition, Janoschka (Citation2002) and Klaufus (Citation2017) shed some light on the inequality, segregation and market aspects related to fragmentation. Moreover, Bénit-Gbaffou (Citation2008) and Santos (Citation1990) analyzed spatial fragmentation in terms of the differences in services and opportunities depending on locational aspects. Brazilian metropolises are no exception and are also known for their spatial fragmentation, with walls separating different urban fragments, and many in-between, left-over spaces, as well as cultural differences and inequality of access to services and opportunities.

While researchers have pointed out these characteristics of Brazilian metropolises (Santos Citation1990; Klink and Denaldi Citation2012), it seems that spatial fragmentation in the Global South will not be resolved by merely connecting different fragments. Other social forces, such as violence, inequality and stigmatization, for example, play an important role in maintaining urban fragmentation and keeping residents separated. Different theoretical frameworks, for example, the Just City (Fainstein Citation2010), or Planning and Diversity in the City (Fincher and Iveson Citation2008), suggest the creation of spaces of encounter to promote social ties between diverse groups. Nevertheless, social challenges, such as the striking inequality within Brazilian cities, are not considered in these approaches. It is hard to believe that residents of slums will come together with well-off residents of gated communities if merely provided with a well-designed public space. Fragmentation in Brazil is not only spatial but also social. Spatial fragmentation is intrinsically connected to social disconnection, but tackling the spatial component only does not guarantee the improvement of social connection. This does not mean that public spaces in Brazil do not need good design, but urban planning needs to go beyond design and address the social issues that make these encounters more difficult when they occur in spaces of extreme inequality.

Attempts to create spaces of encounter in the metropolises of the Global South have faced difficulties (Maricato, Lobo, and Leitão Citation2009; Friedmann Citation2010). Authors have highlighted the importance of planning, due to the social challenges and inequality present in Brazilian metropolises (Vilaça Citation2011). Design-based and top-down approaches to the renewal of public spaces, for example, rarely manage to tackle the complex social challenges of Brazilian metropolises. As a result, planners have used different strategies to promote changes in the built environment. It has become more common to observe planners taking part in self-organized initiatives, for example. This not only points to a possible change in the role of planners (Taşan-Kok and Oranje Citation2017) but also demonstrates that these initiatives can be seen as important agents in shaping cities. Regarding the capacity to work with an extremely diverse group, self-organized initiatives seem to be able to succeed better compared to top-down planning, since they are based on an already existing local social network and have a more inclusive approach. The capacity of these initiatives to create social ties between extremely diverse and unequal groups is fundamental to an understanding of how these initiatives can counteract the spatial fragmentation logic of Brazilian metropolises.

Spatial fragmentation, understood as the sum of autonomous parts in the same city (Balbo and Navez-Bouchanine Citation1995), is constructed in an extremely unequal manner. From a broader perspective, this can be seen as a difference in levels of autonomy. Nevertheless, spatial fragmentation in Brazilian metropolises also has a social inequality aspect, with Santos pointing out that it is connected to unequal access to services and opportunities (Santos Citation1990). For example, gated communities and informal settlements can be seen as autonomous parts of a city, and it is clear that both possess a high level of autonomy. However, they operate in very distinct ways and have different access to services and opportunities. In this sense, unlike other kinds of fragmentation, the social inequality present in Brazilian metropolises makes it harder to connect such unequal urban fragments. Gated communities and informal settlements greatly rely on the social networks within their own communities, but the level of social connection between the two realms in South American cities is traditionally quite superficial or merely professional (Sabatini and Salcedo Citation2007). To develop public spaces in such a fragmented context is challenging, especially spaces that foster social connections between people from extremely diverse socio-economic backgrounds.

Even acknowledging that the pattern of social connections has changed due to the influence of social media, the effect that the built environment has on the promotion of these connections remains paramount. Using the concept of the Network Society, Manuel Castells, for example, points out how social connections are being created differently today (Castells Citation2004). Nevertheless, this does not undermine the importance of the spatial variable in relation to this issue, despite increasing the complexity of the way in which social connections are created nowadays.

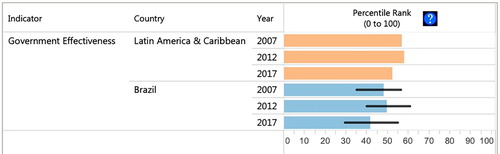

Distinct planning theories have addressed the importance of developing strong social connections within the built environment. As mentioned above, Susan Fainstein’s ‘Just City’ (Fainstein Citation2010) is one of these. The framework presents social connection as one of the fundamental requirements for attaining what, according to the author, are the three most important elements of a just city: diversity, equity and democracy. Although the Just City framework is extremely helpful for establishing criteria which orient planning policy towards fairer built environments, the cases of New York, London and Amsterdam, addressed in the book, do not accommodate the complex and extreme scenario of inequality occurring in metropolises of the Global South. Several scholars have pointed out the difficulties of creating just cities in the Global South (Maricato, Lobo, and Leitão Citation2009; Winkler Citation2009; Musset Citation2015). One reason commonly mentioned to explain this failure is the quality of government in cities of the Global South, which is said to generate unequal services. The worldwide governance index (WGI) of the World Bank demonstrates how the Brazilian government is facing challenges to improve its effectiveness. According to the WGI, the country has lower government effectiveness even compared to other Latin American countries ().

Figure 1. Government effectiveness from World Bank (Kaufmann and Kraay Citation2018).

Fincher and Iveson (Citation2008) also explored social connection as a tool to ‘plan for diversity’, in an attempt to incorporate the challenges of planning in diverse cities. They developed a normative strategy to improve what they referred to as the ‘three social logics of urban planning’: redistribution, encounter and recognition. Ahmadi has shown that other factors, such as poverty, play a bigger role than diversity in influencing the interactions of inhabitants, even in North American cities (Ahmadi Citation2017). In Brazilian metropolises, diversity is also present, but planning for diversity seems not to be sufficient when inequality is even higher than in North America. In the case of Brazil, it is evident that inequality plays a fundamental role not only in spatial fragmentation but also with regard to how people interact. In aiming to promote stronger social connections within Brazilian metropolises, adopting the framework of ‘planning within inequality’ would be a better fit than planning for diversity.

In this context, self-organized initiatives seem to have a greater potential to plan within inequality. They are capable of fostering social connections between their participants because the success of their work depends on these social ties. It is common for informal settlements and gated communities, for example, to have some self-organized initiatives. Nevertheless, these initiatives mainly operate inside their own communities. Thus, it is interesting to shed light on self-organized initiatives that aim to improve public spaces outside informal settlements and gated communities, which inevitably have to work with a more diverse group of people. These self-organized initiatives are often led, influenced or supported by architects and planners.

At this point, it is important to clarify what type of self-organization is being referred to here. There are two main interpretations of ‘self-organization’ in urban studies. The first relates to complexity science (Ashby Citation1947; Foerster and Zoepf Citation1962; Eigen Citation1971; Haken Citation1983), while the second is used in governance studies (van Dam, Eshuis, and Aarts Citation2009; Kotus and Hławka Citation2010; Wunsch Citation2013; Nunbogu et al. Citation2017). Although both fields use the term ‘self-organization’ and the definitions have some similarities, they are fundamentally different. Rauws (Citation2016) developed a framework to distinguish the two in an attempt to avoid possible confusion. While self-organization, as seen through a complexity science lens, focuses on the emergence of spontaneous urban patterns from individual local interactions (Portugali Citation1999; Heylighen Citation2008), in governance studies, the focus is on processes of self-governance, where citizens take the lead rather than the government and produce a kind of bottom-up, grassroots, ‘do-it-yourself’ urbanism (Newman et al. Citation2008; Kee and Miazzo Citation2014). The latter interpretation, aligned with governance studies, is used in this study.

According to Rauws, self-organization considered from a governance studies perspective has four main characteristics that clearly distinguish it from the complexity science perspective: first, there is internal coordination, where members develop a participation and decision-making process; second, actions are undertaken with a collective intent, where there is a common goal, for example the renewal of a public space; third, a change in the urban environment is the result of this deliberate action designed to achieve this common goal; and fourth, the transformation of the urban system is to some extent predictable (Rauws Citation2016). In summary, the initiatives rely on an internal process of coordination, have a common goal, bring people together to act to achieve this goal and the result of this change is relatively predictable. Additionally, these self-organized initiatives work independently from the government (van Dam, Eshuis, and Aarts Citation2009; Swyngedouw and Moulaert Citation2010; Schmidt-Thome et al. Citation2014) and usually operate around the established networks of governance and institutions (Lydon and Garcia Citation2015). Moreover, the self-organized initiatives investigated in this research relied on the participation of planners.

1.3. Methods

The research mainly used qualitative methods to understand how self-organized initiatives operate in fragmented contexts. A set of semi-structured interviews was developed to shed light on different issues related to how the initiatives function. The questions, for example, were focused on the following topics (although they were not limited to these topics): their organization methods, communication, finance, the agenda and area of action, the interaction between members from the initiative and the local inhabitants, and expected and achieved results. The plan was to have semi-structured interviews and give the respondents the opportunity to highlight other relevant factors related to their operation. Thirty interviews were conducted in two months of fieldwork in Brasília, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The strategy behind selecting different cities was to avoid being limited by the fragmentation dynamics of one city and to be able to look for common patterns in the way initiatives work.

The interviews took place in July and August 2016, in public places, cafés, in the interviewee’s home or in the work place of the initiative. In total, 12 self-organized initiatives were studied and an additional set of interviews with public servants and local experts were conducted to gather external views. Most of the interviewees were planners and architects, with a total of 20 interviewees having this professional background. It is important to clarify that, in Brazil, architecture and urban planning are always taught together. The interviews were audio-recorded and analyzed later with Atlas.ti software. Additionally, field observations during physical meetings and participation in the online groups associated with these initiatives also provided insights for the analysis ().

Table 1. Initiatives interviewed.

The preparation for the fieldwork was done from abroad, so the first attempt to contact the initiatives was made using email and social media. Although the physical distance was an initial challenge, the strategy of contacting the initiatives using the internet proved to be relatively successful. This online scanning of possible initiatives generated a schedule of 10 interviews before the fieldwork itself started. The personal network of the researcher, who is a planner himself, was also used to contact possible interviewees.

Subsequently, a snowballing technique was utilized to find new contacts, which produced the remaining interviews. It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the snowballing technique. Since the initiatives suggested contacts in their own network, this meant that they led us to others who were working on related topics or in the same areas of the city. Notwithstanding this limitation, the aim of the research was not undermined, as the first group of initiatives contacted through the online scan was quite diverse and, moreover, the research focused more on how these initiatives operated in the city rather than on how they were related to each other. In this sense, the snowballing technique was extremely efficient, since there was an active network of different initiatives and they were less concerned about providing an interview when recommended by a colleague from another initiative.

1.4. Self-organized initiatives as a planner’s tool

Firstly, it is important to clarify that the concept of planning used in this article is not limited to the design of the built environment or the creation of norms to regulate the physical development of cities. It also refers to the processes that create these spaces and norms. In this respect, planning can vary considerably between different places. In many cities of the Global South, for example, planning occurs with and without the formal support of public institutions (Watson Citation2014), including through the work of self-organized initiatives. Not surprisingly, these initiatives also rely on the participation of planners. The interviewees often explained that their participation in the initiatives was motivated by a desire to further an agenda that they believed in as a planner. This was the case for one planner who explained how his group decided to act after they noticed that the traditional way of working in conjunction with public authorities was not leading to any action:

A lot of autonomous actions started, things that we would like the municipality or the state to do, for example … but the people got there and thought ‘well, if they [the municipal authority] don’t do it, let’s do it ourselves’ and this was very interesting. (Member of Organismo Parque Augusta)

In this short quote, it is possible to identify a sense of disappointment with the work of the public authorities. This frustration was mentioned in all of the interviews of members of self-organized initiatives. The data collected showed that the frustration with the government’s inertia was an intrinsic aspect of these self-organized initiatives. The complaints varied from simple annoyance with governmental red tape to a general discontent concerning governmental urban policies at the macro level. The interviews showed that these planners acted in self-organized initiatives as a direct response to governmental inefficiency. Planners from these initiatives demonstrated confidence about the possibility of furthering their agendas or implementing specific actions more efficiently through these initiatives, rather than using official government channels.

In the specific case of Parque Augusta mentioned above, which involved the occupation and renewal of a public park located on private land, the interviewee expressed surprise at the positive result of the action. Although the initiative did not achieve by then its long-term goal of permanently opening the park to the general public, it was possible to partially implement their wishes without waiting for the public authorities to intervene. This led to the realization among the planners of the potential of self-organized initiatives. Although the planners interviewed were enthusiastic about their impact as members of these initiatives, this does not mean that they did not face difficulties and drawbacks. Nonetheless, they were convinced that these actions were effective and, from their perspective, had generated positive results.

It is like putting together urban planning with society … but with what society really needs. Sometimes urban planning comes too much from above. It’s not something authoritarian, but mainly vertical. And there is not a dialogue … but if you only get this dialogue, you don’t know much what to do. You need to have this meeting between the two. (Member of Bela Rua)

It is interesting to note that this confidence in the work of self-organized initiatives and the disappointment with public authorities did not keep members away from the local government. Three interviewees from self-organized initiatives were also working in different departments of the local government. The data from the interviews showed that they did not see a contradiction between these two functions but understood them to be complementary. They referred to their work as a public servant as something more ‘bureaucratic’ and their participation in self-organized initiatives as more connected to their ‘ideologies’, or what they believed was better for the city.

Nevertheless, this division is not that clear cut. It is misleading to believe that their ideology does not influence their technical work and that their technical knowledge does not influence the way they participate in these initiatives. Additionally, this perception of participating in self-organized initiatives based on an ‘ideology’ does not seem connected to the profile of activist planning presented by Sager (Citation2016). The planners interviewed did not justify their actions in self-organized initiatives based on a response to neoliberal planning, but rather as a way to be more closely connected to civil society, as mentioned in the quote.

Planners have different perspectives from the regular citizens who also take part in these initiatives. It was interesting to note that all of the planners interviewed had prior knowledge of the urban challenges and policies of the city as a whole. As a consequence, planners taking part in self-organized initiatives saw their actions as being integrated into a broader context. Although the actions of these initiatives focused on a restricted local context, such as a square or an alley, for example, all of the interviewees contextualized their actions in terms of a comprehensive solution to challenges faced by the city, such as improving mobility, increasing the amount of green space, developing better infrastructure, or increasing community participation. As shown in the quote from the Bela Rua member above, urban planners who are engaged in self-organized initiatives are both conscious of the general challenges in the city and also expect that these self-organized initiatives will contribute to and confront these challenges. This perspective goes well beyond that of ordinary citizens, who do not have technical knowledge gained from professional planning education but become involved because they are interested in solving a specific challenge in their neighbourhood. The data from the interviews showed that planners actively take part in these initiatives because they believe in their capacity to tackle the macro challenges facing the city, even if their activities related to the initiatives are limited, for example, to the scale of a public square. Additionally, this perception that planners have a pluralist and managerial role is increasingly being acknowledged among planners (Fox-Rogers and Murphy Citation2016). The self-organized initiatives researched are definitely seen by the planners interviewed as a possible tool to reshape the city.

1.5. Planning in cities with high socio-economic inequality

Planning for just cities or planning for diversity must also recognize that inequality is extremely high in Brazilian metropolises. According to the World Bank, based on the GINI index, Brazil ranks as the eleventh most unequal country in a list of 144 nations (Bank Citation2016). As previously discussed in the theoretical section, it is difficult to develop public spaces in such an unequal context (Maricato Citation2011; Vilaça Citation2011). Even excellent quality public design can fail to foster redistribution, recognition and encounter, as suggested by Fincher and Iveson (Citation2008). This is definitely more striking in central metropolitan areas, where inequality is greater than in the peripheral zones (Paulo Citation2019). The renewal of the Largo da Batata, a public square in São Paulo, is emblematic because it was a successful project in terms of design and functionality led by the municipality. However, it did not manage to integrate the higher and lower income residents in the use of the public space. This integration only occurred after a self-organized initiative called ‘a batata precisa de você’ – ‘The batata square needs you’ – which developed the social connections in this unequal context (Da Silva and Rojas-Pierola Citation2018). In order to understand how these self-organized initiatives work in extremely unequal environments, the interviews addressed topics related to the diversity of the public involved in their activities and affected by their work.

All 12 initiatives mentioned that the public affected by their work was extremely diverse, which is an inherent characteristic of central areas of Brazilian metropolises. The interviewees referred not only to the financial inequality between users but also to the social contrasts and conflicts concerning how the public space was being used. Initiatives would try, for example, to renew public spaces by giving different uses to marginalized areas; however, it was common that these areas were used by vulnerable groups, such as homeless people. As a consequence, it was a challenge to reconcile the new uses of the public space – bringing more activities to these areas but still serving the needs of the vulnerable groups already established in these marginalized areas. This was the task of another case study, Terreyro Coreográfico, which attempted to use dance activities to develop new functions in marginalized public spaces such as those under viaducts. These conflicts concerning the use of public space are well expressed in the following quote:

There is this thing of the people living there. So, there is the smell of shit, of pee, of cooked beans. You are in a way in contact with these peoples’ intimacy, which is an experience that a lot of people can’t stand … to be so close to this. To be there doing a class [dance classes] and having a person waking up next to you. (Member of Terreyro Coreográfico)

The quote provides an example of extreme contrasts in the use of public space. Despite the natural conflicts created by these different uses, the initiative attempted to bring together these two diverse groups, which would rarely interact otherwise. The data from the interviews indicates that these encounters were not previously planned nor were they part of the initial strategy of the self-organized initiatives. However, the initiatives were aware that this was an inevitable challenge when working on public spaces in Brazilian metropolises. In the specific case of Terreyro Coreográfico, the initiative maintained a dialogue with the homeless people living in the area and included them in their activities. As a result, the self-organized initiative not only brought a new function to a marginalized space but developed new social ties between the users:

For example, last year we made a ‘festa junina’ [a party based on Brazilian country folklore]. And there were like people from the neighbourhood, workers and middle-class people … there were the real homeless people … also a transgender person who lives under this viaduct … there were some artists. It was crazy, everybody was dancing together […] I thought it was beautiful to have this integration between people from such different groups. (Member of Terreyro Coreográfico)

The quote not only reveals the positive result of the interaction promoted by the initiative within this diverse group but also the surprise of the interviewee to witness this success. As mentioned above, this interaction was not the aim of any of the initiatives. Nevertheless, the strategy used to provide a new function to this marginalized space generated an opportunity to create social connections within this diverse group. The necessity of accommodating extremely diverse people was referred to in all of the interviews. Although the initiatives did not follow traditional strategies of urban renewal, such as focusing mainly on design, the data indicated that they were able to promote interaction between users of the public spaces on which they were working. The interviewees revealed that this process of do-it-yourself urbanism (Finn Citation2014) created strong social connections between users. Despite not following the normative strategy suggested by Fincher and Iveson (Citation2008), and not using traditional planning strategies, the self-organized initiatives were able to foster redistribution, recognition and encounter when renewing public spaces. Their success indicates that public authorities could definitely learn something from the modus operandi of these initiatives.

Notwithstanding the above, there were some conflicts and internal challenges to be overcome by the initiatives. The diversity found among the group of people affected by the work of the initiatives was definitely not the same as that within the group working on the initiatives. Although the interviewees mentioned that they were diverse to some extent, this diversity did not compare with that of the people affected by their work. This divergence of social differences between the users of the public spaces in Brazilian metropolises and the members of the initiatives was confirmed by the field observations. When observing an open meeting from the initiative ‘A Batata precisa de você' it was clear that there was a clear socio-economic difference between the leaders of the initiative and the local public space users that were attending that evening. The self-organized initiatives that participated in the interviews and in which urban planners were involved, were mainly composed of highly educated middle-income earners. As such, the initiatives were more homogenous than the public affected by their work and this could be one of the reasons why they had more difficulties acting in neighbourhoods with a predominantly low-income population, with whom the initiative’s members did not have strong social ties previously. Only one initiative interviewed focused mainly on areas with a predominantly low-income population, and they mentioned the difficulties that they faced acting in these areas. The data from the interviews reflected this, indicating that the self-organized initiatives interviewed had difficulties establishing dialogue with the residents of less affluent neighbourhoods.

Despite the relative socio-economic uniformity of the members of the initiatives, their work was still successful in creating social ties in areas known to have a predominantly less affluent population. Although planning in extremely unequal contexts has proven to be challenging (de la Espriella Citation2007), the self-organized initiatives were able to operate successfully. The interviews and field observations confirmed that inequality was present in all of the public spaces in which the initiatives were working; however, this difficulty did not compromise their capacity to create social connections and implement their actions.

1.6. Discussion and conclusions

Aligned with the frustration of young planners nowadays (Taşan-Kok and Oranje Citation2017), this active attitude towards the built environment perhaps indicates a change in the manner that planners perceive these initiatives. In the past, traditional top-down planning might have considered these initiatives to disrupt the planned order, but today, planners have joined these initiatives and are using them to shape the built environment. The interviews suggest that planners are taking part in these initiatives because they believe that such activities can be effective in tackling urban challenges within their cities on local and macro scales. Although it is still unclear what the greater impacts of these initiatives will be in the city as a whole, the positive perception of planners and their interest in these initiatives already indicates that they might play a greater role than previously expected. As pointed out by Watson and Siame, there is still a lot to be learned from these co-creation processes, especially those coming from the Global South (Watson and Siame Citation2018).

Additionally, it is interesting to note that planners are assuming different roles in these initiatives compared to traditional planning practice. As pointed out in different interviews, they perceive their work in self-organized initiatives to be closer to what is wanted by civil society. In this sense, planners are positioning themselves as mediators between the technical realm and the local community. Also, in all of the initiatives that participated in the interviews, the planners seem to reject the status of leadership. Instead, they are trying to promote more horizontal relationships with local citizens and to avoid being labelled as the drivers of the actions, even when their leadership position was clear. Additionally, they portray their work in the initiatives as being more ideological and less technocratic than that of traditional planning practice. Nevertheless, the interviews showed that is difficult to separate the two dimensions. The planners involved in self-organized initiatives still used very technical terminology to describe their actions, aims and results from working in such initiatives. Thus, it is hard to believe that planners working in the municipality, developing very technical functions, are not influenced by their own ideology.

The research revealed that these initiatives were indeed able to work closely with civil society and function even in contexts of extreme inequality. Perhaps this is one of the factors that led urban planners to work more closely with them. Based on Sabatini and Salcedo’s framework (Citation2007), there is definitely a change from functional integration, when the relationship between residents is basically dictated by power and money, to symbolic integration between these extremely diverse groups, when there is a common sense of belonging. This means that besides mitigating conflicts, the interaction revealed in the interviews and field observation shows a clear collaboration in the level of symbolic integration, with this diverse socio-economic groups voluntarily working together with a common goal to improve their common space. This does not mean that the social connections created are sustainable and will lead to long-term social connections. The incorporation of a temporal factor to verify the durability of these social connections could be beneficial in future studies. Furthermore, these social connections do not reach the level of community integration, when there is a notion of intimacy and complicity (Sabatini and Salcedo Citation2007). The results show only that these initiatives were able to create social connections that were effective while renewing public space.

This contrasts with projects led by public authorities, where the main focus is on delivering a good design, but which often fail to promote social connection within unequal environments. This capacity to create social connections in contexts of extreme inequality is interesting because it undermines the logic of spatial fragmentation in Brazilian metropolises, which is not only based on the disconnection of spaces but also on extreme social division. Although the interviews revealed that this was not their initial aim, the self-organized initiatives studied here managed to go beyond the renewal of a public space in also fostering social connections between diverse groups.

The research presented here was limited to the central areas of the three cities and to initiatives that were receiving support of urban planners. This revealed interesting insights about the role of planners and their strategies. However, it does not show a complete picture and a further investigation over other types of self-organized initiatives and other locations would be very fruitful. A closer look into initiatives in peripheral areas or with a majority of low-income members, for example, could reveal different dynamics, aims or challenges. It would be interesting to investigate if there are initiatives based on more marginalized areas that are also succeeding to promote social connection with people from more affluent neighbourhoods.

It is important to note that the research could only understand the local impacts of these initiatives, and the macro effects in the three cities are still unclear. While the study generates insights into the modus operandi of self-organized initiatives and how planners are engaging with them, the research could still be broadened in scale, using quantitative methods, and also in scope. It would be particularly interesting to understand how those implementing public policies could work with these initiatives to achieve better results. While self-organized initiatives have a strong capacity to create social ties, municipalities have the experience and power necessary to implement spatial changes. It could be mutually beneficial to promote more cooperation between the public authorities and self-organized initiatives. The possibility of cooperation opens new questions and avenues for research. For example, how might public authorities support these initiatives? In an environment with an array of initiatives, how can central planning work with them to promote cohesion and not fragmentation?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmadi, D. 2017. Living With diversity in Jane-Finch. TU Delft, A+BE|Architecture and the Built Environment. No. 12. Retrieved from http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:d1f12d39-a25f-44e3-a2e6-3c8dafbb113a.

- Ashby, W. R. 1947. “Principles of the Self-Organizing Dynamic System.” The Journal of General Psychology 37 (2): 125–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1947.9918144.

- Balbo, M. 1993. “Urban Planning and the Fragmented City of Developing Countries.” Third World Planning Review 15: 23–35.

- Balbo, M., and F. Navez-Bouchanine. 1995. “Urban Fragmentation as a Research Hypothesis: Rabat-Salé Case Study.” Habitat International 19 (4): 571–582.

- Bank, W. 2016. GINI Index.

- Bayón, M. C., and G. A. Saraví. 2013. “The Cultural Dimensions of Urban Fragmentation: Segregation, Sociability, and Inequality in Mexico City.” Latin American Perspectives 40 (2): 35–52.

- Bénit-Gbaffou, C. 2008. “Unbundled Security Services and Urban Fragmentation in Post-Apartheid Johannesburg.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 39 (6): 1933–1950.

- Çakir, G., C. Ün, E. Z. Baskent, S. Köse, F. Sivrikaya, and S. Keleş. 2008. “Evaluating Urbanization, Fragmentation and Land Use/Land Cover Change Pattern in Istanbul City, Turkey from 1971 to 2002.” Land Degradation and Development 19 (6): 663–675.

- Castells, M. 2004. The Network Society: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar Pub.

- Cortes, J. M. G. 2008. Politicas Do Espaço: Senac Editora.

- Da Silva, C. C. R., and R. R. Rojas-Pierola. 2018. “Economic Dynamics of an Urban Space in Dispute. Largo da Batata, São Paulo (Brazil).” Bitacora Urbano Territorial 28 (1): 163–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v28n1.68331.

- de la Espriella, C. 2007. “Designing for Equality: Conceptualising a Tool for Strategic Territorial Planning.” Habitat International 31 (3-4): 317–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2007.04.003.

- Eigen, M. 1971. “Molecular Self-Organization and the Early Stages of Evolution.” Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 4 (2&3): 149–212.

- Fainstein, S. S. 2010. The Just City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Fincher, R., and K. Iveson. 2008. Planning and Diversity in the City: Redistribution, Recognition and Encounter. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Finn, D. 2014. “DIY Urbanism: Implications for Cities.” Journal of Urbanism 7 (4): 381–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2014.891149.

- Foerster, H., and G. W. Zoepf. 1962. Principles of Self-Organisation. New York: Pergamon.

- Fox-Rogers, L., and E. Murphy. 2016. “Self-Perceptions of the Role of the Planner.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 43 (1): 74–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813515603860.

- Friedmann, J. 2010. “Place and Place-Making in Cities: A Global Perspective.” Planning Theory & Practice 11 (2): 149–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649351003759573.

- Haken, H. 1983. Synergetics: An Introduction: Nonequilibrium Phase Transitions and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology. Berlin; New York: Springer.

- Heylighen, F. 2008. “Complexity and Self-Organization.” In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences, edited by M. J. Bates and M. N. Maack, 250–259. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Janoschka, M. 2002. “New Urban Structure Models of Latin American Cities: Fragmentation and Privatization.” EURE - Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Urbano Regionales 28 (85): 11–29.

- Kaufmann, D., and A. Kraay. 2018. The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) from World Bank. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/wgidataset.xlsx.

- Kee, T., and F. Miazzo. 2014. We Own the City: Enabling Community Practice in Architecture and Urban Planning. Amsterdam: TrancityxValiz.

- Klaufus, C. 2017. “All-inclusiveness Versus Exclusion: Urban Project Development in Latin America and Africa.” Sustainability 9: 11.

- Klink, J., and R. Denaldi. 2012. “Metropolitan Fragmentation and Neo-Localism in the Periphery: Revisiting the Case of Curitiba.” Urban Studies 49 (3): 543–561.

- Kotus, J., and B. Hławka. 2010. “Urban Neighbourhood Communities Organised on-Line – A New Form of Self-Organisation in the Polish City?” Cities 27 (4): 204–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2009.12.010.

- Lydon, M., and A. Garcia. 2015. Tactical Urbanism. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Maricato, E. 2011. O Impasse da Política Urbana no Brasil. Petrópolis, RJ - Brazil: Vozes.

- Maricato, E., B. G. Lobo, and K. Leitão. 2009. “Fighting for Just Cities in Capitalism's Periphery.” In Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice, edited by Peter Marcuse, James Connolly, Johannes Novy, Ingrid Olivo, Cuz Potter, and Justin Steil, 194–213. London: Routledge.

- Musset, A. 2015. “The Just City's Myth, a Neoliberal Cheatings.” Bitacora Urbano Territorial 25 (1): 11–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v1n25.53216.

- Newman, L., L. Waldron, A. Dale, and K. Carriere. 2008. “Sustainable Urban Community Development from the Grassroots: Challenges and Opportunities in a Pedestrian Street Initiative.” Local Environment 13 (2): 129–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701581879.

- Nunbogu, A. M., P. I. Korah, P. B. Cobbinah, and M. Poku-Boansi. 2017. “Doing it ‘Ourselves’: Civic Initiative and Self-Governance in Spatial Planning.” Cities, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.022.

- Paulo, R. N. S. 2019. Mapa da Desigualdade. São Paulo, Rede Nossa São Paulo.

- Portugali, J. 1999. Self-organization and the City. New York: Springer.

- Rauws, W. 2016. “Civic Initiatives in Urban Development: Self-Governance Versus Self-Organisation in Planning Practice.” Town Planning Review 87 (3): 339–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2016.23.

- Sabatini, F., and R. Salcedo. 2007. “Gated Communities and the Poor in Santiago, Chile: Functional and Symbolic Integration in a Context of Aggressive Capitalist Colonization of Lower-Class Areas.” Housing Policy Debate 18 (3): 577–606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2007.9521612.

- Sager, T. 2016. “Activist Planning: A Response to the Woes of Neo-Liberalism?” European Planning Studies 24 (7): 1262–1280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1168784.

- Santos, M. 1990. Metrópole Corporativa Fragmentada: O Caso de São Paulo. São Paulo: Nobel.

- Schmidt-Thome, K., S. Wallin, T. Laatikainen, J. Kangasoja, and M. Kyttä. 2014. Exploring the Use of PPGIS in Self-Organizing Urban Development: Case softGIS in Pacific Beach (Vol. 10).

- Swyngedouw, E., and F. Moulaert. 2010. “Can Neighbourhoods Save the City?: Community Development and Social Innovation.” In Regions and Cities, edited by F. Moulaert, 219–234. New York: Routledge.

- Taşan-Kok, T., and M. Oranje. 2017. From Student to Urban Planner: Young Practitioners’ Reflections on Contemporary Ethical Challenges. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- van Dam, R., J. Eshuis, and N. Aarts. 2009. “Transition Starts With People: Self-Organising Communities ADM and Golf Residence Dronten.” In Transitions: Towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Chains in Peri-Urban Areas, edited by K. Poppe, C. Termeer, and M. Slingerland, 81–92. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Vilaça, F. 2011. “São Paulo: Segregação Urbana e Desigualdade.” Estudos Avançados 25 (71): 37–58.

- Watson, V. 2014. “Co-production and Collaboration in Planning – The Difference.” Planning Theory and Practice 15 (1): 62–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.866266.

- Watson, V., and G. Siame. 2018. “Alternative Participatory Planning Practices in the Global South: Learning from Co-Production Processes in Informal Communities.” In Public Space Unbound: Urban Emancipation and the Post-Political Condition, edited by Sabine Knierbein and Tihomir Viderman, 143–157. New York: Routledge.

- Winkler, T. 2009. “Prolonging the Global Age of Gentrification: Johannesburg's Regeneration Policies.” Planning Theory 8 (4): 362–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095209102231.

- Wunsch, J. S. 2013. “Analyzing Self-Organized Local Governance Initiatives: Are There Insights for Decentralization Reforms?” Public Administration and Development 33 (3): 221–235.