ABSTRACT

On the surface, contemporary urban megaprojects suggest a convergence in form: office towers, hotels, museums, shopping and renewed public spaces often involving transnational firms and renowned architectsHowever, framing local policiesas instances of a ‘serial reproduction’ of iconic landscapes obscures more than reveals how circulating planning models are reproduced and institutionalized. To this effect, this paper suggests a complementary approach between the literature of policy mobilities and new institutionalism focusing on how policies are ‘arrived at’ and the role of ideas in the policy process. An analytical framework is applied to the case study of a large-scale waterfront regeneration programme in Rio de Janeiro to examine the mutual evolvement between ideas, interests and institutions. The paper concludes by stressing the importance ofpaying attention to how policy knowledge is assembled, institutionalized and interests identified.

1. Introduction

After decades of studies, lobbying and proposals the regeneration of the port area of Rio de Janeiro was announced in June 2009 in an official ceremony attended by the president of Brazil, the governor of the state of Rio, and the city mayor. The presence of the government leaders symbolized a political coalition capable to overcome jurisdictional barriers and turn the megaproject into reality. The Porto Maravilha programme aims to regenerate five million m² of docklands, industrial buildings and warehouses into a new mixed-use neighbourhood. Signature buildings by global architects are changing the landscape with office towers, hotels, museums, and renewed public spaces. Despite not featuring any prominent Olympic venue, the programme was heralded as one of the main legacies of the 2016 Games.

Once made official there was an effort to position the project alongside waterfront regenerations programmes elsewhere. The publication ‘Porto Maravilha + 6 Successful Case Studies of Waterfront Renewal’ edited by the municipality in 2010 compared it to the experiences of Baltimore, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Hong Kong and Rotterdam. The programme was presented as ‘one of the most important urban experiences of our times, a true historic mark in the development of Latin American port cities’ (Dias Citation2010, 231).

However, for all the inter-referencing efforts and previous attempts that drew on foreign examples more explicitly, it was a nearby experience that influenced more significantly the modelling of Porto Maravilha. Complying with the norms of the Brazilian federal law 10.251 known as the City Statute, the programme incorporated features learned from São Paulo’s Urban Operation experiences. As the proponents of the project have found, rather than appealing to aesthetic visioning inspired by other places, the key drivers to turn the proposal into reality was the definition of the institutional and financial model. In this sense, the Porto Maravilha programme can be seen both as an example of circulating practices of waterfront regeneration schemes worldwide (Brownill Citation2013; Cook and Ward Citation2012; Ward Citation2006) and as an intrinsically ‘homemade’ solution to the legal and political challenges imposed by the national and local contexts. This paper argues that in addition to critically evaluate how policy ideas travel (McCann and Ward Citation2011; Peck and Theodore Citation2015) it is necessary to examine how they interact with other key dimensions in the policy process. Debates in the new institutionalism literature argue for greater attention to the role of ideas and their mutually constitutive dynamics with interests and institutions (Béland and Cox Citation2011; Dilworth and Weaver Citation2020). An analytical framework based on the interactions between ideas, interests and institutions is applied to examine how the Porto Maravilha megaproject was ‘arrived at’ and implemented during its first years up to 2016. Nonetheless, the project has been significantly impacted by the economic downturn and political crisis in the post-Olympic period and this context is also considered.

This paper is structured in three sections. The first section reviews the literature on the circulation of policy models and institutional analysis known as constructivist institutionalism. It argues that in adopting a socio-constructivist stance to the analysis of policymaking and the circulation of policy ideas, both sets of literature are complementary in the examination of how policies are arrived at and are institutionalized. The second section examines the making of the Porto Maravilha programme through three key elements in the policy process: ideas, in the approaches to urban regeneration; interests, in the convergence among the main stakeholders; and institutions, in the articulation of the delivery and financing of the operation. This empirical section draws on fieldwork undertaken between 2013 and 2015 comprising of 21 semi-structured interviews with key policy actors (development authorities, consultants, developers, and senior civil servants) and discourse analysis of policy and media material. The final section concludes by revisiting the recent debates raised in the review of the literature with an analysis of the project delivery while demonstrating the benefits of bridging circulating policy and institutional analysis used in the analytical framework.

2. ‘Arriving at’ megaprojects and the role of ideas in the policy process

Contemporary urban megaprojects attract much attention, in part, for their reinforcing global-local dynamic: global processes shape local change which in turn reshape how the former is conceptualized and understood before it is again reinforced elsewhere. As ‘mechanisms par excellence through which globalization becomes urbanized’ (Moulaert, Rodríguez, and Swyngedouw Citation2003, 3), the ‘new wave’ of megaprojects targets large ‘obsolete’ inner-city areas for a structural transformation characterized by mixed land-uses that combine residential, commercial, leisure and natural amenities (Diaz Orueta and Fainstein Citation2008; Lehrer and Laidley Citation2008; del Cerro Santamaría Citation2013). With the help of transnational architecture, planning, and engineering firms; promoted images of iconic and vibrant landscapes circulate globally (Rapoport Citation2015; Sklair Citation2017) encouraging the learning and mobilization of planning, financing, and governance mechanisms. Waterfront renewal schemes are paradigmatic approaches to large-scale regeneration projects (Jajamovich Citation2019; Oakley Citation2011) and their ‘striking resemblance to each other, suggest that a formula or ‘instant mix’ recipe for regeneration is being followed’ (Brownill Citation2013, 45). Academic criticism of the ubiquitous manifestation of urban megaprojects is levelled at its regressive approach in concentrating high volumes of public investment in speculative real estate programmes, the lack of transparency in governance arrangements, the ‘exceptionality’ surrounding planning approval processes, the privatization of the urban space and the worsening of social inequalities (Cuenya, de Novais, and Vainer Citation2012; Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez Citation2002; Tarazona Vento Citation2017). Urban megaprojects such as waterfront regeneration are thus seen as vehicles of neoliberal urbanism and uneven spatial development (Boland, Bronte, and Muir Citation2017; Peck, Theodore, and Brenner Citation2009).

In order to mediate the tension between structural analysis of policy convergence and empirical examinations of how circulating ‘best practices’ are negotiated locally, the policy mobilities literature advocates an approach capable of ‘tacking back and forth between specificity and generality, relationality and territoriality’ (McCann Citation2011, 109, emphasis added). A central tenet of the scholarship is to critically examine how models and people move between places while recognizing that there is a politics structuring the process of circulation and replication. However, as Temenos, Baker, and Cook (Citation2019, 113) note, one of the ‘more prominent approaches has been to ‘follow the policy’ as it moves across global landscapes’. While this has attended concerns to examine the relational in urban policymaking – i.e. networks and knowledge that stretch beyond the city and shape local policies – it has been less attentive to the territorial in how local actors ‘arrive at’ (Robinson Citation2013) policies within an environment of multiple references. To remediate this, Robinson (Citation2013, 31) suggests to ‘invert the problematic’; i.e. rather than ‘tracking connections and following where they go … we might take as our lens the question of how urban policies are arrived at’.

Taking a grounded perspective to the politics in how local policies are relationally produced; recent debates have highlighted three tendencies in the policy mobilities literature that require addressing. Firstly, there is a tendency to examine policy circulation through a global-local dualism that overlooks the importance of other scales such as national, regional or intra-urban (Borén, Grzyś, and Young Citation2020; Prince Citation2017; Varró and Bunders Citation2020). Temenos and Baker (Citation2015, 842) raise important questions about the scales needed for a policy to be considered mobile when learning can take place among cities in the same country and even within departments in the same governance context. The second tendency is to overemphasize the role of highly mobile policy actors such as consultants or international organizations at the expense of local actors at the ‘demand side’ who are also mobile and act in strategic ways in the mobilization of expertize (Bunnell, Padawangi, and Thompson Citation2018; Grandin and Haarstad Citation2021; Silvestre and JajamovichCitation2021). Recent discussions on developers as embedded ‘relational actors’ for instance, has called attention to their ability to draw on circulating models of financing and urbanism while coordinating complex institutional contexts (Brill Citation2020; Mouton and Shatkin Citation2020). Thirdly, there is also a tendency to fetishize the speed at which policies circulate as ‘ready-made’ and ‘quick fixes’ that disregards the often long temporal processes in which policies mature and are implemented (Grimwood et al. Citation2021; Ward Citation2018; Wood Citation2015). Policymaking is often characterized by non-linearity with learning taking on multiple references and by the legacies of previous studies and non-successful attempts. An analysis of how relational policies are arrived at needs thus to be sensitive issues of scale through which knowledge circulate (including what is already present), the local agency in assembling and coordinating multiple references and institutions, and temporality in the longue durée of a policy idea.

This paper argues that there is a complementarity to be found with the new institutionalism literature concerned with the role of ideas in the public policy process. Developed in reaction to other strands of the policy literature that had arguably over-emphasized the role of material interests (rational choice) or institutional and cultural constraints to behaviour (historical institutionalism, sociological institutionalism), constructivist institutionalism privileges ideas as the entry point for examining policy change (Béland and Cox Citation2011; Blyth Citation2002; Gofas and Hay Citation2010; Schmidt Citation2008). In what is a diverse body of approaches and methods, ideas have been examined for their role as ‘road maps’, ‘focal points’, ‘strategic weapons’, or ‘frames of reference’ among other nominations (for a review see Béland Citation2009), that can ‘structure or limit policy debate and action’ (Hogan and Howlett eds Citation2015, 5). Nevertheless, from the ‘innumerable ideas in circulation’ only a few gain prominence in politics (Berman Citation2001, 233), which brings to the fore ‘the way ideas are packaged, disseminated, adopted, and embraced’ (Béland and Cox Citation2011, 13). ‘The muddle of politics’, add Béland and Cox (Béland and Cox Citation2011, 13), ‘is the muddle of ideas’. It is this ‘muddling through’ informed by multiple sources of knowledge that policies are arrived at.

The concern of constructivist institutionalism analysis is to consider the dynamic interplay between actors with constructed interests; institutional spaces and norms that can limit what is acceptable; and frames of reference to how policy issues can be understood and addressed. Rather than taking interests as given, Hay (Citation2011, 69) indicates that actors’ ability to ponder what is ‘feasible, legitimate, possible, and desirable’ is influenced both by ‘the institutional environment in which they find themselves and by existing policy paradigms and worldviews’. In its turn, institutional spaces are more than simply the background where interests are articulated, and ideas promoted. When entering institutions, ideas find historically formed practices and policy legacies that influence their acceptability unless there is also pressure from higher levels of authority. Once embedded, ideas influence future behaviour (Berman Citation2013).

A combinatory perspective drawn from how policies are arrived and the role of ideas in policy making, both reasoned on a socio-constructivist approach, offers the opportunity to acknowledge the influence of ideas in circulation while paying close attention to the processes through which they are assembled, transformed and institutionalized in policy outputs. As new institutionalists have noted (Béland and Cox Citation2011; Blyth Citation2002; Dilworth and Weaver Citation2020), such approach must be attentive to the mutually constitutive relationship between ideas, interests and institutions, or ‘the three I’s’, which provide the analytical framework employed to examine the case study.

3. Ideas, interests and institutions in the delivery of the Porto Maravilha regeneration programme

Between 2009 – when the regeneration of the port area was announced – and 2011 – when Porto Maravilha became a reality – the programme was carefully designed to overcome the barriers identified in previous studies, especially in the articulation of different government levels and in finding a suitable financial model. The sections below examine how ideas, interests and institutions evolved in close interaction to give form and content to the programme. These are, according to Dilworth and Weaver (Citation2020, 1), the ‘holy trinity’ for the study of politics, although the focus on ideas has tended to be overshadowed in relation to the other two dimensions. An analysis of the dialectical relationship between these three key variables of policy making offers important methodological gains. Accordingly, they serve to delimit the axes of the analysis and decompose a complex policy dynamic into identifiable dimensions that can help to explain a policy outcome (Palier and Surel Citation2005). Applying the ‘three I’s’ allows the researcher to examine the explanatory weight of each dimension and how they are mutually constituted (Surel Citation2018). For this reason, the analytical framework applied below is inherently relational, that is, each dimension is scrutinized in relation to other factors in a processual manner.

3.1 The idea: waterfront regeneration templates for Rio

The challenges imposed by containerization technology since the 1960s and the construction of the Port of Itaguaí in 1982 led to the decline of activities and to the dereliction of Rio de Janeiro’s historic port area. Urban interventions isolated the region and contributed to the decay of its neighbourhoods such as the construction of a 5.5 km elevated highway in the 1960s. Plans for urban renewal came in succession but were not able to overcome conflicting public interests between different government levels, institutional resistance, and insufficient demand from private investors. In the first half of the 1980s, businesses in the foreign trade engaged with experiences and consultants from abroad to lobby for approaches ranging from the creation of Special Economic Zones, Japanese-style Teleports, and the replication of many of the features of waterfront areas elsewhere, most noticeably that of Baltimore’s inner harbour. After a period of more modest interventions, the idea of a flagship project capable of stimulating trickle-down effects was presented in the early 2000s. Influenced by the visibility acquired by the city of Bilbao, the City Hall announced the construction of an iconic branch of New York’s Guggenheim Museum, but plans were brought to a halt by legal challenges concerned with the high volume of public investment involved. Nevertheless, the studies concerning infrastructural improvement and enhancement of public areas carried out by the planning office remained as a blueprint for future interventions.

After decades of plans that failed to progress beyond the study phase, a new approach to large-scale urban regeneration was developed by some of the largest Brazilian construction companies at the end of the 2000s. It responded to a public call for the elaboration of a feasibility study having a public-private partnership (PPP) as a central element. The final report focused on establishing a financial and institutional design able to facilitate the regeneration programme (Rio Mar e Vila Citation2007). In relation to the former, it proposed to apply the planning instrument of Urban Operation (Operação Urbana Consorciada) and a self-financing mechanism with the sale of building rights (Certificates of Additional Potential of Construction, CEPACs). In accordance with the specifications of the National City Statute, this model of urban intervention gives the basis for the flexibilization of existing planning controls in a delimited area () to stimulate real estate demand and thus be financially leveraged by the state and used exclusively to finance the operation (Klink and Stroher Citation2017). The governance model foresaw the need to establish a development authority responsible for the delivery of the programme in close coordination with a private partner. Such an institution would have its assets formed by the transfer of public-owned land and the sale of CEPACs.

The programme was designed to be property-led and thus dependent on real estate interest to which the report confidently forecasted a demand of 24.5 million m² until 2024 in ‘a conservative scenario’ (Rio Mar e Vila Citation2007, 76). The option for the Urban Operation was justified having the experience of São Paulo as an explicit reference:

After the [enactment of the] City Statute only two urban operations involving the issuing of CEPACs were developed, both in São Paulo. The results obtained were positive; especially considering it was a pioneering experience. São Paulo’s successful experience indicates that its model should be followed. Any different arrangement will be noticed by investors and thus compromise the attractiveness of the certificates. (Rio Mar e Vila Citation2007, 62–3)

The report thus established that São Paulo’s regeneration programmes self-financed with the sale of building rights were the yardstick for Rio’s proposal This was paramount to make the programme attractive for investors:

For a new security such as CEPAC, the main causes of concern are certainly that of legal nature. For this reason, we have always pointed in this study to the most cautious institutional modelling … It concerns simply of considering as an absolute priority the interest of investors, whom the financing of the operation is dependent upon. (Rio Mar e Vila Citation2007, 63)

Differently from previous regeneration studies, the focus of the proposal was on the financial and governance model rather than on the aesthetics of the project. It argued that it incorporated the studies developed by the municipality in previous decades and the recommendations from an inter-ministerial federal group regarding appropriate planning instruments for the area (Sarue Citation2016). A senior planner of the Secretariat of Urbanism who assisted in the study explained this position:

When the [construction] companies sat with us to prepare their proposals, the study was refined. [They said they] did not have interest in the operation from an urbanism perspective. “We are construction companies, so what we want? We want to put our trucks in movement, our machines in operation and the workforce to work.” That was it … They started the studies, saw that it was feasible, that it could be sustained and it worked out. It really blossomed. (interview, senior planner, 19/11/2013)

The proposal was the basis of the Porto Maravilha programme officially announced in 2009 under a new government at the City Hall that reproduced the political coalition formed in 2006 at the regional and national governments. It proposed an extensive list of large-scale civil engineering works such as tunnels, expressways, and infrastructure upgrading. In addition, it outsourced the concerted delivery of basic public services such as street lighting, sweeping, waste collection, road maintenance, and traffic management to a private partner. The PPP contract would last for 15 years at an estimated cost of BRL eight billion over the period (USD 2.8 bi in 2012 prices).

3.2 Interests: aligning big capital with big politics

A consideration of the mutual relation between ideas and interests serves to avoid accruing to ideas a force on their own and instead pay attention to how they are socially constructed and championed by ‘carriers or entrepreneurs, individuals or groups capable of persuading others to reconsider the ways they think and act’ (Berman Citation2013, 228). The relationship between ideas and interests is according to John (Citation2012) key for examining the causes of stability and change in public policy. As the author argues, while interests realize ideas to attain them, ideas are also constitutive of interests. In this sense, different interests converged to the materialization of the Porto Maravilha. Central to the process were the changes in the oil and gas industry that fuelled demand for office spaces in Rio combined with the high rates of economic growth that the Brazilian economy experienced in the decade. Politicians, international developers, and construction companies identified in the programme opportunities for their interests.

The project epitomized the alliance between two of the main political parties controlling the federal and Rio’s state governments. The election of a new mayor in 2008 signalled a novel situation of multi-scalar political alignment capable of galvanizing support to the regeneration of the port area. As previous proposals had found out, the coordination of different land interests was key. The largest areas for the application of CEPACs were public land belonging to the federal government (63%), the state government (6%) and the municipality (6%) with the remaining 25% being made of numerous smaller private properties (CDURP Citation2010). The weight of political support from the federal government, especially after the programme was associated with the 2016 Olympics, was able to overcome the entrenched interests of the port authority to sell the land to the municipality and thus release it for real estate. Late in 2009, having an ample support in the city council, the mayor got approval for the Porto Maravilha programme and for the creation of the Urban Development Company of the Port Area (CDURP).

The rising demand for office spaces was a turning point for the chances of a large-scale project. According to a study by Colliers International Real Estate (Citation2009), the local vacancy rate of 0.64% was among the lowest in the world. There was particular pressure in the city centre near the port area, especially in the demand of companies having the state-run oil company Petrobrás and other Federal Government agencies as clients. The study concluded that Rio had the highest average price by square metre of top corporate space in the country. The contribution of the oil and gas industry to the regional GDP grew from 1.25% in 1995 to 12.03% in 2005 and 17.65% in 2012 (Ceperj Citation2014). In 2006 a large oil basin was detected along with the pre-salt layer of the south-eastern coast of Brazil near Rio, with an estimated potential of generating four times more oil than the national production and make the country the sixth-largest world producer by 2035 (IEA Citation2013).

During the second half of the 2000s, a host of new developments and the retrofitting of existing stock were delivered in Central Rio and rented exclusively to tenants such as Petrobrás, the Brazilian Development Bank, and the State Grid Corporation of China. The market signs encouraged international developers to evaluate opportunities. After the approval of Porto Maravilha, CDURP’s chief executive prospected the interest of potential investors to finance the operation, as he explained:

We were planning [a piecemeal operation] but then the gentlemen from [US-based developer] Tishman [Speyer] came here in 2011 … He said, “I put BRL 1 billion if I am given the preference over the land around Francisco Bicalho [avenue]”. We said, “Great you will have the preference, we will include this in the design of the real estate fund so you sit there during the auction [of CEPACs] and you can table a bid of BRL 1 billion”. However, we still needed 3.5 billion to cover the operation. (interview, CDURP CEO 15/01/2015)

At this stage, Rio’s urban operation pointed to a different financing dynamic than that in São Paulo where the sale of CEPACs was carried over a long period and was negotiated at each stage of the development process. A decision was made by the municipality to sell all the certificates in a single package. The financing of the 15-year programme was secured upfront when the state-run Federal Savings Bank announced it would invest the semi-public funds of the national Employee Severance Indemnity Fund (FGTS) to buy the whole stock of CEPACs at the cost of BRL 3.5 billion. FGTS is constituted of compulsory payments by employers to provide financial compensation to employees in case of dismissal and retirement. The fund also assists the Brazilian state to finance key public policies such as housing and infrastructure but recent changes to its constitution led to an increase in the activity as a real estate investor, as exemplified in the Porto Maravilha programme (Royer and Oliveira Citation2021). The symbolic auction of a single package of certificates of building rights in 2011 guaranteed the payment of the construction companies chosen in the tendering to appoint the private partner. A consortium formed by the same companies that designed the feasibility study that gave origin to Porto Maravilha was chosen.

The consortium was formed by some of the largest Brazilian construction companies – OAS, Odebrecht, and Carioca Engenharia – that are regularly awarded tendered contracts to deliver public projects. The interest of the construction companies was motivated by two factors. First by the delivery of the large-scale infrastructural projects they helped to define in the feasibility study. Second, as aforementioned, by the outsourcing of basic public services under one single contractor, which was a novel feature in Brazilian PPPs. According to an executive of the consortium ‘the provision of services in an integrated model under the responsibility of a single company as it is done here, is an innovation, a pioneering one’ (interview 15/01/2015). Therefore, these companies played a central role in the design, budgeting and implementation of the programme and stood to gain financial and intellectual capital from the experience. Porto Maravilha constituted a laboratory for a new approach of Brazilian urban regeneration through PPPs and the construction companies were active in disseminating the model . While protocols were put in place to receive ‘missions’ of policy makers from other Brazilian cities – turning the port area into a policy tourism destination (González Citation2011) – the companies were also involved in new feasibility studies of regeneration projects in other cities in the country that argued for similar approaches (Stroher and Dias Citation2019). Elsewhere, the programme has been promoted by the World Bank as a case study on urban regeneration ‘meant to distil good practices and lessons learned’ (World Bank Citation2020).

Nevertheless, the ability of the construction companies in influencing the design and delivery of public policies was also carried out via informal and illicit channels. Featuring as some of the major donors in Brazilian political campaigns, they were able to lobby in favour of the project at different government levels (Carazzai and Carvalho Citation2014). The major criminal investigation ‘Operation Car Wash’ launched in 2014 unveiled an extensive kickback scheme involving these and other construction companies alongside the mainstream of political parties. Large public contracts were systematically tendered at inflated prices with the companies returning the favour via campaign donations. Representatives of the three construction companies involved with the Porto Maravilha project confessed having paid bribes to the speaker of the lower house of the federal Congress for his influence over the executive management at the Federal Savings Bank (Coutinho Citation2015; Ministério Público Federal Citation2018). Although some of the involved were sentenced, the case is still ongoing and was not sufficient to halt the project. However, the economic downturn and the implications of the corruption investigation have tested the mechanisms of project delivery.

3.3 Institutions: risk-proofing project delivery

Institutions are constituted of ideas that become established over time and thus affect the policy decisions that follow. However, new ideas can also challenge existing ones leading to institutional change. Institutions thus provide the space in which the abstraction of ideas are realized into policy action (Muller Citation2000). Important in the analysis is to examine the process of institutionalization of ideas, how they become embedded and come to influence norms, behaviour and decision-making (Radaelli Citation1995). The Porto Maravilha project was designed to institutionalize a particular rationale of urban development aimed to reduce risks from political interference, guarantee the payment of the private partner, and stimulate real estate demand.

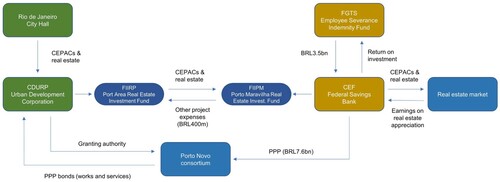

The regeneration programme is sustained by a sophisticated financial architecture that institutionalizes the relationship between three sets of actors (). First is the state, represented by Rio de Janeiro City Hall and CDURP as development authority, owner of public land and of the CEPAC building rights. Second is the ‘market’, in this case represented by the state-run Federal Savings Bank as the main investor after purchasing the totality of certificates and acquiring large areas where CEPACs are applied, whose gradual payment will cover the costs of the project while renegotiating them with developers at each project. The third is the private partner, represented by the consortium of construction companies responsible for delivering works and services. The relationship among these actors is regulated through the financial instruments of real estate investment funds, public-private partnerships, and joint ventures in new developments. As noted earlier, this architecture was facilitated by a positive economic scenario and the cooperation among different government levels, critical factors in the initial years of the Porto Maravilha programme.

CDURP was created as a semi-public development company with shares that were owned by the municipality. The company recruited key personnel from outside the municipal staff, most noticeably executives with a relationship with the employees’ pension fund of the Federal Savings Bank, the third largest in the country. According to its Chief Financial Officer (CFO), this was an important feature to gain the confidence from investors, as CDURP staff ‘do not talk in different languages. We talk the language of the real estate market’ (interview, CDURP CFO 11/12/2013).

Following the recommendation of the feasibility study to ‘segregate’ the delivery company from ‘risk’ – in an allusion to the changes of political cycles – a key feature in CDURP’s design was to create a real estate fund to which the company’s assets were subscribed to. This fund (the Real Estate Investment Fund of the Port Region, FIIRP), constituted the official channel of the company with the market. Institutionalizing the relationship among the different actors via real estate regulation served to address both the fundamental issues of credibility and risk, as the CFO further explained:

What instruments do we understand that talk the market language? The market didn’t know CDURP. It thinks ‘gosh, a relationship with a municipal company, well there is a risk in this’. How can this be a little more palatable for the market? So, before we made CEPAC, we put all our assets, which are land and CEPAC, and we allocated in FIIRP, which has CDURP as single shareholder. (interview, CDURP CFO 11/12/2013)

The estimated cash flow to pay for the costs of BRL eight billion over the 15 years of the operation had to be financed with the sale of assets from CDURP to investors. As discussed in the previous section, all the building rights were auctioned in a single offer won by the Federal Savings Bank paying BRL 3.5 billion in the application of resources from FGTS. According to the terms and conditions of the auction, the bank assumed all the costs of the programme operationalized via the constitution of another investment fund (the Porto Maravilha Real Estate Investment Fund, FIIPM). In this fund, CDURP transferred the assets of FIIRP – CEPACs and land – in return for the continuous payment of the operation over 15 years. The bank’s role, as detailed by their regional manager, is to generate surpluses from the negotiation of CEPACs and land to other investors as to pay for all the programme costs and provide a return on investment to FGTS:

FGTS subscribes to FI Porto Maravilha BRL 3.5 billion and this BRL 3.5 billion will serve to make all the payments of the operation. But this is the key issue, the operation doesn’t cost 3.5 billion, the operation costs around BRL 8 billion [over 15 years] and is this difference between the 3.5 and the 8 billion that the [FII] Porto Maravilha has to perform in order to pay the operation while also returning the investment to FGTS. (interview, Federal Savings Bank manager 09/12/2013)

The relationship among the actors involved in the operation is thus institutionalized through real estate investment funds and their decisions constrained by commitments on returns on investment and performance indicators. The delivery of the urban operation is intrinsically tied with the demand from the real estate market while the risk of the operation is underwritten by the Federal Savings Bank and FGTS. Coupled with the dominant office demand coming from companies working in the oil and gas sector it exposes the programme to multi-scalar risks. Indeed, this has been the case since 2014. The slump in global oil prices at the end of that year and the crisis affecting the Brazilian economy and politics since 2015 have seriously affected the delivery of Porto Maravilha.

The Federal Savings Bank plays as the de facto developer of the region by virtue of detaining the land and the building rights. However, up to September 2020 less than 10% of the certificates were negotiated (CDURP Citation2020), indicating the slow real estate activity for high rise developments. This has affected the cash flow of the operation and in 2018 the bank announced the illiquidity of its investment fund and stopped making payments to the private partner. More recently, it has been declared that the investment was known since the beginning not to be viable (Nogueira Citation2020). As a result, the municipality has resumed the delivery of public services after the dissolution of the private consortium. Despite not making public announcements, the bank is withholding the acquired land while waiting for a recovery of the economic activity. The role of the institution in the regeneration programme through the investment of FGTS funds demonstrates its transformation from a federal agency aimed to implement public policies to a real estate speculator. The rationale of the regeneration programme has thus been ‘locked in’ in the public institutions that underwrite the risks of a property-led scheme with investment from public funds aimed to provide social welfare and finance development.

4. Conclusion

At a first sight, the landscape emerging in the Porto Maravilha regeneration programme resembles that of waterfront renewal schemes found elsewhere. New spaces of consumption have been renovated, modern transport systems have been implemented, and iconic images of office and cultural buildings dot the urban space, including signature projects by global architects like Santiago Calatrava and Norman Foster (). This, in part, confirms earlier analyses of large-scale urban development projects in the Global North as vehicles for neoliberal urbanization (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez Citation2002). However, as this paper has shown, this analysis of a ‘serial reproduction’ provides only a cursory view of the dynamics of megaproject delivery, or a ‘trap’, as Ponzini (Citation2020, 18) argues, of ‘placeless images and critiques’. An understanding of how policies are ‘arrived at’ – and potentially leading to new ‘best practices’ – is required. An attention to how ideas, interests and institutions can be mutually constituted offers an analytical tool to examine policy making and interrogate the politics of urban change.

Figure 3. Aerial view of the regenerated port area of Rio having the Museum of Tomorrow at front and new office towers at the back, right (source: CDURP/Bruno Bartholini).

The analysis provided in this paper contributed to addressing some of the concerns raised in recent debates in the policy mobilities literature regarding the slow and non-linear evolvement of policies, the multiple scales from which policy actors draw on and assemble knowledge, and the role of ‘relational actors’ embedded in the policy context who mobilize models while navigating complex institutional landscapes. Firstly, the several visions and projects developed for the port area of Rio de Janeiro over decades created a milieu of references – or multiple elsewheres (Robinson Citation2013) – through which public and private policy actors sifted through with some practices sedimented in studies while others were short-lived. Rather than the continuous development of a coherent policy, proposals for the regeneration of the area were characterized by multiple entry points (Ward Citation2018) and by ‘serial introductions before the innovations [took] root locally’ (Wood Citation2015, 578). Secondly, while such mobilization of knowledge drew in some instances from globally circulating ‘best practices’ in waterfront renewal, it was from the nearby experience of São Paulo with urban regeneration programmes that the financial and governance designs were modelled after. In the assembling of policy ideas, what is desirable and feasible involves as much legitimation of persuasive ‘policies that work’ from distant sites as from proximate ones (Grandin and Haarstad Citation2021) indicating how legal and institutional implications can be addressed. In order to mitigate ‘risk’ in the Porto Maravilha programme, institutional relations were designed to ‘lock-in’ a property-led regeneration rationale (both in staffed officials in the development authority and in the use of investment funds to regulate relationships) and minimize political interference. Thirdly, the analysis has also contributed to ongoing efforts in gaining a better understanding of the practices of local private actors who ‘represent an important juncture at which universalizing global forces and contingent local contextual factors meet’ (Mouton and Shatkin Citation2020, 405). In this case, it also reinforced the attention to other scales as the large Brazilian construction companies exerted their influence, in many instances through illicit practices, over both national and subnational scales by establishing coalitions to mitigate risk (Brill and Robin Citation2020). As a deeply embedded actor, these companies designed a proposal with large-scale civil engineering works and outsourced public services that offered them not only the prospect of relevant financial returns but also the chance of experimenting a new model of urban regeneration for Brazilian cities that they were keen to disseminate. Lobbying occurred at multiple networks, especially at the national level given that the position of the federal government as major landowner of the area and the role of the Federal Savings Bank in underwriting the risks of the operation by virtue of purchasing the totality of certificates of building rights. Although this proximate relationship between large private companies and major political decision-makers is a long-standing feature of Brazilian development politics (Campos Citation2014; Sarue Citation2016) the Porto Maravilha programme presents empirical evidence on how it evolves through new arrangements.

Lastly, this paper has contributed to approximate debates in the policy mobilities with that of new institutionalism examining the role of ideas in the policy process. It has responded to Robinson’s (Citation2013) call for ‘inverting the problematic’ and analyse how policies are arrived at. This opens the way for a critical urban policy analysis that interrogates how ideas shape actors’ motivations and become institutionalized (Berman Citation2013). The examination of the case study demonstrated the need for a closer analysis of the reproduction of urban models beyond their cosmopolitan veneer as it may reveal more fundamental issues of dynamics in megaproject delivery and the arrangements between public and private parties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Béland, D. 2009. “Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Change.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (5): 701–718.

- Béland, D., and R. H. Cox. 2011. Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berman, S. 2001. “Ideas, Norms, and Culture in Political Analysis.” Comparative Politics 33 (2): 231–250.

- Berman, S. 2013. “Ideational Theorizing in the Social Sciences Since “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State”.” Governance 26 (2): 217–237.

- Blyth, M. 2002. Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boland, P., J. Bronte, and J. Muir. 2017. “On the Waterfront: Neoliberal Urbanism and the Politics of Public Benefit.” Cities 61: 117–127.

- Borén, T., P. Grzyś, and C. Young. 2020. “Intra-urban Connectedness, Policy Mobilities and Creative City-Making: National Conservatism vs. Urban (neo) Liberalism.” European Urban and Regional Studies 27 (3): 246–258.

- Brill, F. 2020. “Complexity and Coordination in London’s Silvertown Quays: How Real Estate Developers (re) Centred Themselves in the Planning Process.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (2): 362–382.

- Brill, F. N., and E. Robin. 2020. “The Risky Business of Real Estate Developers: Network Building and Risk Mitigation in London and Johannesburg.” Urban Geography 41 (1): 36–54.

- Brownill, S. 2013. “Just add Water: Waterfront Regeneration as a Global Phenomenon.” In The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration, edited by M. E. Leary, and J. McCarthy, 45–55. London: Routledge.

- Bunnell, T., R. Padawangi, and E. C. Thompson. 2018. “The Politics of Learning from a Small City: Solo as Translocal Model and Political Launch pad.” Regional Studies 52 (8): 1065–1074.

- Campos, P. H. P. 2014. Estranhas Catedrais: As Empreiteiras Brasileiras e a Ditadura Civil-Militar, 1964-1988. Niterói: Eduff.

- Carazzai, E. H., and M. C. Carvalho. 2014. Empreiteiro Relata Lobby para Fazer Obra no Porto do Rio. Folha de São Paulo, December 7. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2014/12/1558759-empreiteiro-relata-lobby-para-fazer-obra-no-porto-do-rio.shtml.

- CDURP. 2010. Apresentação do Projeto Porto Maravilha para a Ademi. http://www.ademi.org.br/IMG/pdf/doc-873.pdf.

- CDURP. 2020. Relatório trimestral de atividades. Período julho, agosto e setembro de 2020. https://portomaravilha.com.br/conteudo/relatorios/2020/_RELATORIO_JUL_AGO_SET%202020_FINAL.pdf.

- Ceperj. 2014. Produto Interno Bruto do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. http://www.ceperj.rj.gov.br/ceep/pib/pib.html.

- Colliers International. 2009. The Knowledge Report – Offices, Second Semester. Rio de Janeiro.

- Cook, I. R., and K. Ward. 2012. “Relational Comparisons: The Assembling of Cleveland's Waterfront Plan.” Urban Geography 33 (6): 774–795.

- Coutinho, F. 2015. “Eduardo Cunha Cobrou R$ 52 mi em Propina para Liberar Dinheiro do FI-FGTS, diz PGR”. Época, December 16. http://epoca.globo.com/tempo/noticia/2015/12/exclusivo-eduardo-cunha-cobrou-r-52-mi-em-propina-para-liberar-dinheiro-do-fi-fgts-diz-pgr.html.

- Cuenya, B., P. de Novais, and C. B. Vainer. 2012. Grandes Proyectos Urbanos: miradas críticas sobre la experiencia argentina y brasileña. Buenos Aires: Editorial Café de las Ciudades.

- del Cerro Santamaría, G. 2013. Urban Megaprojects: A Worldwide View. Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Dias, S. 2010. “Rio de Janeiro e o Porto Maravilha.” In Porto Maravilha + 6 Casos de Sucesso de Revitalização Portuária, edited by V. Andreatta, 208–231. Rio de Janeiro: Casa da Palavra.

- Dilworth, R., and T. P. Weaver. 2020. “Ideas, Interests, Institutions, and Urban Political Development.” In How Ideas Shape Urban Political Development, edited by R. Dilworth, and T. P. Weaver, 1–18. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Gofas, A., and C. Hay. 2010. The Role of Ideas in Political Analysis: A Portrait of Contemporary Debates. London: Routledge.

- González, S. 2011. “Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in Motion’. How Urban Regeneration ‘Models’ Travel and Mutate in the Global Flows of Policy Tourism.” Urban Studies 48 (7): 1397–1418.

- Grandin, J., and H. Haarstad. 2021. “Transformation as Relational Mobilisation: The Networked Geography of Addis Ababa’s Sustainable Transport Interventions.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 39 (2): 289–308.

- Grimwood, R., T. Baker, L. Humpage, and J. Broom. 2021. “Policy, Fast and Slow: Social Impact Bonds and the Differential Temporalities of Mobile Policy.” Global Social Policy. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018121997809.

- Hay, C. 2011. “Ideas and the Construction of Interests.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by D. Béland, and R. H. Cox, 65–82. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hogan, J., and M. Howlett eds. 2015. Policy Paradigms in Theory and Practice: Discourses, Ideas and Anomalies in Public Policy Dynamics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- International Energy Agency. 2013. World Energy Outlook 2013. https://www.iea.org/Textbase/npsum/WEO2013SUM.pdf.

- Jajamovich, G. 2019. Puerto Madero en movimiento. Un abordaje a partir de la circulación de la Corporación Antiguo Puerto Madero (1989-2017). Buenos Aires: Teseo.

- John, P. 2012. Analysing Public Policy. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Klink, J., and L. E. M. Stroher. 2017. “The Making of Urban Financialization? An Exploration of Brazilian Urban Partnership Operations with Building Certificates.” Land Use Policy 69: 519–528.

- Lehrer, U., and J. Laidley. 2008. “Old Mega-Projects Newly Packaged? Waterfront Redevelopment in Toronto.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32 (4): 786–803.

- McCann, E. J. 2011. “Urban Policy Mobilities and Global Circuits of Knowledge: Toward a Research Agenda.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (1): 107–130.

- McCann, E., and K. Ward. 2011. Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ministério Público Federal. 2018. Operação Sépsis. http://www.mpf.mp.br/df/sala-de-imprensa/docs/alegacoes-finais-sepsis.

- Moulaert, F., A. Rodríguez, and E. Swyngedouw. 2003. The Globalized City: Economic Restructuring and Social Polarization in European Cities. Oxford: OUP.

- Mouton, M., and G. Shatkin. 2020. “Strategizing the for-Profit City: The State, Developers, and Urban Production in Mega Manila.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (2): 403–422.

- Muller, P. 2000. “L'Analyse Cognitive des Politiques Publiques: Vers une Sociologie Politique de l'Action Publique.” Revue Française de Science Politique 50 (2): 189–208.

- Nogueira, I. 2020. Caixa diz que Porto Maravilha do Rio era inviável desde o início. Folha de São Paulo, June 4. https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2020/06/apos-prejuizo-bilionario-ao-fgts-caixa-diz-que-revitalizacao-do-porto-do-rio-e-inviavel.shtml.

- Oakley, S. 2011. “Re-imagining City Waterfronts: A Comparative Analysis of Governing Renewal in Adelaide, Darwin and Melbourne.” Urban Policy and Research 29 (3): 221–238.

- Orueta, F. D., and S. S. Fainstein. 2008. “The New Mega-Projects: Genesis and Impacts.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32 (4): 759–767.

- Palier, B., and Y. Surel. 2005. “Les « Trois I » et l'Analyse de l'État en Action.” Revue Française de Science Politique 55 (1): 7–32.

- Peck, J., and N. Theodore. 2015. Fast Policy: Experimental Statecraft at the Thresholds of Neoliberalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Peck, J., N. Theodore, and N. Brenner. 2009. “Neoliberal Urbanism: Models, Moments, Mutations.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 29 (1): 49–66.

- Ponzini, D. 2020. Transnational Architecture and Urbanism: Rethinking how Cities Plan, Transform, and Learn. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Prince, R. 2017. “Local or Global Policy? Thinking About Policy Mobility with Assemblage and Topology.” Area 49 (3): 335–341.

- Radaelli, C. M. 1995. “The Role of Knowledge in the Policy Process.” Journal of European Public Policy 2 (2): 159–183.

- Rapoport, E. 2015. “Globalising Sustainable Urbanism: The Role of International Masterplanners.” Area 47 (2): 110–115.

- Rio Mar e Vila. 2007. Projeto Rio Mar e Vila. Vol. I. Rio de Janeiro.

- Robinson, J. 2013. “‘Arriving at’ Urban Policies/the Urban: Traces of Elsewhere in Making City Futures.” In Critical Mobilities, edited by O. Söderström, S. Randeria, D. Ruedin, G. D'Amato, and F. Panese, 23–51. Lausanne: EPFL Press.

- Royer, L., and V. Oliveira. 2021. “O fundo público na era da dominância da valorização financeira. O caso do FGTS.” In Habitação e o direito à cidade – desafios paras as metrópoles em tempos de crise, edited by A. L. Cardoso, and C. D’Ottaviano, 211–233. Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital.

- Sarue, B. 2016. “Os Capitais Urbanos do Porto Maravilha.” Novos Estudos CEBRAP 35 (2): 78–97.

- Schmidt, V. A. 2008. “Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse.” Annual Review of Political Science 11: 303–326.

- Silvestre, G., and G. Jajamovich. 2021. “The Role of Mobile Policies in Coalition Building: The Barcelona Model as Coalition Magnet in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro (1989–1996).” Urban Studies 58 (11): 2310–2328.

- Sklair, L. 2017. The Icon Project: Architecture, Cities, and Capitalist Globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stroher, L. E. M., and N. R. Dias. 2019. “Operações Urbanas Consorciadas 2.0: origem e performatividade de um modelo em constante adaptação”. Proceedings XVIII ENANPUR 2019. anpur.org.br/xviiienanpur/anais.

- Surel, Yves. 2018. “La mécanique de l’action publique.” Revue Française de Science Politique 68 (6): 991–1014.

- Swyngedouw, E., F. Moulaert, and A. Rodriguez. 2002. “Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large–Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy.” Antipode 34 (3): 542–577.

- Tarazona Vento, A. 2017. “Mega-project Meltdown: Post-politics, Neoliberal Urban Regeneration and Valencia’s Fiscal Crisis.” Urban Studies 54 (1): 68–84.

- Temenos, C., and T. Baker. 2015. “Enriching Urban Policy Mobilities Research.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (4): 841–843.

- Temenos, C., T. Baker, and I. R. Cook. 2019. “Inside Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policy Mobilities.” In Handbook of Urban Geography, edited by T. Schwanen, and R. van Kempen, 103–118. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Varró, K., and D. J. Bunders. 2020. “Bringing Back the National to the Study of Globally Circulating Policy Ideas: ‘Actually Existing Smart Urbanism’ in Hungary and the Netherlands.” European Urban and Regional Studies 27 (3): 209–226.

- Ward, S. V. 2006. “Cities are Fun: Inventing and Spreading the Baltimore Model of Cultural Urbanism.” In Culture, Urbanism and Planning, edited by J. Monclús, and M. Guàrdia, 271–285. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Ward, K. 2018. “Urban Redevelopment Policies on the Move: Rethinking the Geographies of Comparison, Exchange and Learning.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (4): 666–683.

- Wood, A. 2015. “Multiple Temporalities of Policy Circulation: Gradual, Repetitive and Delayed Processes of BRT Adoption in South African Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (3): 568–580.

- World Bank. 2020. Case Studies on Urban Regeneration. World Bank Open Learning Campus. https://olc.worldbank.org/content/case-studies-urban-regeneration.