ABSTRACT

The international circulation of urban design concepts often leads to their characterization as transferable ideals defined by a set of universalized ‘best practices’ that are simply implemented in new localities, as is typical of top-down approaches to planning. Recently, the compact city and New Urbanism have become trendy concepts informing the development of urban projects across geographies. This research draws on ANT sensitivities and policy mobilities studies to examine the regeneration of Copenhagen’s Southern Harbour (Sydhavn) wherein the compact city and New Urbanism ideals, together with a declared inspiration from Dutch architecture, were originally incorporated in the masterplan. Through the analysis of documents and semi-structured interviews, the paper illustrates how these ideals – merged as 'New Compactism' – were mobilized and re-intepreted by local actors in Sydhavn. It thus adds to our understanding of how the circulation of such ideals is not a matter of implementation, but a complex social process of translation that entails struggle and transformation.

1. Introduction

Contemporary urban development is characterized by an international circulation of urban planning and design concepts that shape ‘the global imaginary of urban practitioners and thus have very real effects, although their merits are often not proven’ (Rosol, Béal, and Mössner Citation2017, 1713) when they are implemented in the local context. According to Tait and Jensen (Citation2007, 107), ‘the speed and intensity with which these ideas travel seems historically unprecedented’. Among those travelling concepts, the compact city has been idealized ‘as the preferred response to the goal of sustainable development’ (Hofstad Citation2012, 2).

Such concept has travelled worldwide by means of ‘best practices’ (Stead Citation2012) or the use of measurable indicators (Vicenzotti and Qviström Citation2018) of compactness, both falling into an ‘over-generalizing’ (Healey Citation2012, 202) approach that treats local context as an unproblematic receptacle. This idealization and overgeneralization of the compact city are exacerbated when such a concept is interpreted through the manifestos of urban movements such as New Urbanism (CNU Citation2000). Such movements, and on a more general level all types of developments under the compact city umbrella, promote an abstract and decontextualized use of exemplary projects as best practices (Moore Citation2013). This undermines their compatibility with ‘local environments, which include the conventions, customs and local values’ (Zhang and Gao Citation2018, 218). It has been argued that such compatibility is required when ‘ideas and techniques from outside would become the inspiration for cultivating local best practices’ (Zhang and Gao Citation2018). Indeed, as Latour (Citation2005) has pointed out, transportation necessarily entails transformation, a notion encapsulated in the concept of translation which lies at the heart of actor-network theory (ANT) and has proven useful in the study of how ideas travel, materialize and change in new localities (Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996; Tait and Jensen Citation2007).

In this sense, there is a knowledge gap in regards to the way the Compact City and New Urbanism ideals are translated into different contexts whereby the original idea is subject to a ‘mutation’ (Albrecht et al. Citation2017) as it travels globally, ‘meshing with the requirements and problematizations of each context’ (Albrecht et al. Citation2017, 74). This paper aims to examine how the compact city and New Urbanism concepts travel internationally and are re-interpreted in the local context, focusing on the redevelopment of Copenhagen’s Southern Harbour (Sydhavn). In doing so, it adds to our understanding of how urban planning and design concepts modify, and are modified by, the adopting locality. Even though this case also embodies characteristics of waterfront regeneration projects, whose ideas are also circulating internationally (Garcia Ferrari and Fraser Citation2012), the focus of this paper is mainly on the local reinterpretation of the compact city and New Urbanism, for their value as ‘persuasive concepts in planning rhetoric’ (Grant Citation2003, 234).

The compact city and New Urbanism mix have been previously defined as ‘New Compactism’ (CORDIS Citation2015). Despite the lack of substantial literature using this term, we assume it and use it exclusively for the purpose of describing the mixture of New Urbanism and the compact city. The Sydhavn case is therefore considered as representative of a local version of New Compactism. The idea of compact and mixed-use development in this central part of the Danish capital is forged through a declared inspiration from Dutch Architecture and the inclusion, at least in part, of a New Urbanism or post-modernist approach. In contrast to the characterization of New Compactism as a singular transferable concept defined by a set of universalized ‘best practices’, this paper aims to foreground its contingent character by conceiving of it as a string of varied movements of translation mixing heterogeneous actors, such as people, models, standards and indicators, in particular locations of practice. In this paper, we build on a stream of critical policy research focused on policy mobilities (McCann Citation2011; McCann and Ward Citation2012; Peck Citation2011) as well as on ANT-inspired literature on the travel of ideas (Clarke et al. Citation2015; Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996; Tait and Jensen Citation2007). These streams of research converge on the notion that the translation and circulation of policy or planning ideas into new settings is not merely a matter of implementation or adoption, but a complex social process that entails struggle and transformation, foregrounding the relationality and uncertainty inherent to translation efforts. Policy mobilities literature has tended to focus mostly on the movement of knowledge and models, which has prompted growing calls to develop a more thorough understanding of how policy shapes, and is shaped by, the importing locality (Wood Citation2021). For instance, Prince (Citation2016, 424) has suggested that rather than ‘overly fetishizing the actual movement of policy’, researchers would do well in paying ‘more careful attention to the specific circumstances in which policy is adopted’. In this case, we contribute to such an effort by showing how the ideal of the New Compactism is translated and negotiated over time by various translocal actors in the case of Copenhagen’s Sydhavn. The following research questions are formulated

RQ1: How is New Compactism, as a meld of the compact city and New Urbanism ideals, translated in the Sydhavn development?

RQ2: What is the role of local actors in the mutation/translation process of such travelling ideals?

2. The compact city & New Urbanism as overgeneralized practices

This section is preparatory towards the empirical work as it highlights the rhetoric that stands behind the diffusion and international circulation of the compact city and New Urbanism as idealized urban design models, which, similarly to the case study of this paper, have both been used in waterfront and/or harbour regeneration projects – e.g. for the compact city, see examples in Oslo (Garcia Ferrari, Jenkins, and Smith Citation2012) and Gothenburg (Soneryd and Lindh Citation2019); for New Urbanism, see examples in Toronto (Grant Citation2003) but also in Malmö, where ‘the top-down development in Western Harbour’s urban form (…) is completely in line with new urbanism principles’ (Medved Citation2017, 119). The section is not therefore intended either as a description or as an exhaustive state-of-the-art regarding both concepts, since they have been already widely explained and examined in the literature – e.g. for the compact city: Jenks, Burton, and Williams Citation1996; Churchman Citation1999; Dieleman and Wegener Citation2004; Newman and Kenworthy Citation2006; Boyko and Cooper Citation2011; Westerink et al. Citation2013; Fertner and Große Citation2016; Adelfio et al. Citation2018; Adelfio, Hamiduddin, and Miedema Citation2021; Kain et al. Citation2020; Kain et al. Citation2021; e.g. for New Urbanism: CNU Citation2000; Beauregard Citation2002; Grant Citation2003; Grant and Bohdanow Citation2008; Hirt Citation2009; Moore Citation2013).

The rhetoric of the compact city has been fuelled by a wide institutional endorsement (EU Citation2007; European Commission Citation2011; OECD Citation2012; UN-Habitat Citation2012), which has contributed to its global diffusion, in spite of an insufficient precision and agreement on its definition (Kain et al. Citation2020), The institutionalization (Gorgolas Citation2018) of the compact city has shaped its idealistic and paradigmatic connotation (Adelfio, Hamiduddin, and Miedema Citation2021), to the point that it has become in the European Nordic countries a ‘pervasive “urban norm’” (Tunström, Lidmo, and Bogason Citation2018, 8) for urban design, planning and development. The ‘institutional embedding’ of compact cities served as a way to legitimate them, increase the level of resources and power in their development and achieve ‘reproducibility resulting from the standardization of practice’ (Neuman Citation2005, 21). Even when ‘planners are well aware of this trap of overgeneralization’ (Campbell Citation2016, 395) in the spreading of urban ideas, professionals have shown a ‘deference to the compact city ideal’ (Campbell Citation2016, 393) contributing to its diffusion as a set of ‘institutionalized’ best practices (Gorgolas Citation2018, 56).

New Urbanism, similarly to the compact city, ‘sustains itself as a universal movement’ belonging to the realm of ‘mainstream planning’ (Moore and Trudeau Citation2020, 384). Although in its origins it was ‘dedicated to halting urban sprawl’, it is nowadays also related to ‘the process of urban regeneration within the city’ (Cysek-Pawlak Citation2018, 21), which is in line with the case study presented by this paper. Its global diffusion, idealization and mainstreaming have fuelled its marketing appeal more than a consistent implementation into practice (Grant and Bohdanow Citation2008), producing rather heterogenous results which motivate the need for a better understanding of the ‘translations of the principles of the movement into specific contexts’ (Moore and Trudeau Citation2020). In fact, understanding its local translations can help to counteract the simplistic acceptance of ‘New Urbanism as ‘best practice’’ composed of ‘a formalistic, even ritualistic, set of norms, practices and policies’ (Moore Citation2013, 2382).

In this work, New Urbanism is associated with post-modernism (Audirac and Shermyen Citation1994; Denslagen and Gardner Citation2009), although we acknowledge that such an association has been the object of debate (Beauregard Citation2002; Hirt Citation2009). Here, we embrace this linkage as it emerged from the sources (see the section on method) used in the empirical work – e.g. reference to Soeters as post-modernist and to Sluseholmen as New Urbanist – following also Hirt’s (Citation2009, 248) argument that New Urbanism ‘rejects the key design tenets of modernist planning and strives to revive premodern urban forms (and in this sense qualifies as “post-modern”)’.

3. Exploring the translation of planning concepts through ANT sensitivities

This paper deals with the international circulation and adoption of urban development/planning concepts (Harris and Moore Citation2013). Such topic has been approached through different theoretical lenses – e.g. interpretive policy analysis (IPA) (Healey Citation2013), urban assemblages (McFarlane Citation2011a), actor-network theory (ANT) (Tait and Jensen Citation2007), geography of mobilities (Temenos and McCann Citation2013), and circuits of knowledge (McCann Citation2011; Healey Citation2013). While these approaches differ in their emphasis and assumptions about what is circulating and how (Healey Citation2013), they have in common an interest in ‘mobilities’, converging on the understanding that the movement of knowledge across localities over time is a convoluted social process (Wood Citation2021). In the field of urban studies, over the last decade, the burgeoning interest in the movement of policies and models across geographies has given rise to a research agenda built around the notion of ‘policy mobilities’ (Peck and Theodore Citation2010a; McCann Citation2011; Baker and Temenos Citation2015; Wood Citation2021). This research has shown how travelling ideas are transformed in the embodied practices and social connections made by actors (McCann Citation2011), in ‘a profoundly geographical process, in and through which different places are constructed as facing similar problems in need of similar solutions’ (Ward Citation2006, 70). A number of studies of policy mobilities have shed light on, for instance, the travel of city strategies (Peck Citation2012; Robinson Citation2015), sustainable building assessment models (Faulconbridge Citation2015), waterfront redevelopment schemes (Cook and Ward Citation2012), welfare programmes (Peck and Theodore Citation2010b), harm reduction drug policies (Longhurst and McCann Citation2016) and urban planning concepts (Wood Citation2019). This literature has highlighted the role of circulating nonhumans such as models, texts and photographs (Faulconbridge Citation2010) as particularly relevant, enabling local ‘communities of practice’ (Amin and Roberts Citation2008) to get acquainted with the work of ‘wider constellations of practice’ (Faulconbridge Citation2010, 2855), such as globally circulating projects of architects. Yet, by focusing primarily on the movement of knowledge, policy mobilities studies have paid less attention to how policy shapes, and is shaped by, the appropriating locality (Wood Citation2021). Wood (Citation2016, 392) has suggested a ‘Latourian approach’ to policy mobilities to unravel the procedures through which concepts from elsewhere become rooted in a new locality, attending to ordinary practices ‘be it through engagements with fellow practitioners, with their toolbox of material solutions, or after a particular moment of discovery’.

In this paper, taking our cue from Wood (Citation2016) and Clarke et al. (Citation2015), we mobilize the ANT sensitivities that to a great extent have informed existing literature on the travel of ideas (Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996; Tait and Jensen Citation2007) and combine them with insights from policy mobilities studies, particularly in relation to the role of ‘policy mobilizers’ (McCann Citation2011, 114) and the ‘mutation of travelling policy’ (Albrecht et al. Citation2017, 74). As Mol (Citation2010, 253) argues, ANT is not a coherent theoretical or methodological framework that one simply ‘applies’, but can be better grasped as ‘a set of sensitivities’ that, far from building a solid and fixed scheme, are meant to be used as an adaptable repertoire to help the analyst be attuned to a world in the making. Within such ANT sensitivities, translation appears as a key concept that evokes both notions of movement and transformation, comprising both immaterial – e.g. ideas, knowledge or policies – and material objects (Czarniawska and Sevón Citation1996) – e.g. artefacts or models. As both a semiotic and material movement, translation is helpful to describe how ideas materialize into objects and actions as they circulate from one locality to another (Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996) – a costly process that entails acts of (re-)interpretation and (re-)negotiation (Callon Citation1986). According to Latour (Citation1986), this understanding of translation can be contrasted with the more traditional notion of diffusion. The latter assumes a chain of passive intermediaries who supposedly transmit or transfer a stable object or token, whereas the former foregrounds the uncertainty inherent to ‘the spread in time and space of anything’ whereby human and non-human translators ‘may act in many different ways, letting the token drop, or modifying it, or deflecting it, or betraying it, or adding to it, or appropriating it’ (Latour Citation1986, 267). Translation challenges popular notions of ‘policy transfer’ that rely on this model of diffusion (see Peck Citation2011; Clarke et al. Citation2015).

From this perspective, a travelling policy can be conceptualized as a metamorphosing script inserted into a new network of relations that both changes and is changed by said relations, rather than a stable object that is simply transplanted or transferred from one site to another. In this sense, there is not ‘a global’ concept of the compact city or New Urbanism but only an array of local translations of them. Its ‘global’ character is nothing but a relational achievement resulting from the process of translation. Indeed, ‘policies, models, and ideas are not moved around like gifts at a birthday party or like jars on shelves’, and thus the ‘need to understand and identify who mobilizes policy is crucial precisely because mobilities are social processes’ (McCann Citation2011, 110–111). Hence, apprehending the compact city and New Urbanism as travelling concepts necessitates a ‘post-transfer approach’ (McCann and Ward Citation2012, 328) that highlights how the practice is modified when it is translated in a different location. Since ‘the roles and identities of actors, are negotiated and settled in different contexts (…) policy has to be socially embedded in the target audience by connecting it to particular problems or opportunities within each locality’ (Albrecht et al. Citation2017, 74). In this manner, our analysis dissents from the conventional ‘rationalist-formalist tradition’ (Peck Citation2011, 774) of policy transfer literature, deploying these ANT sensitivities to unpack how the compact city and New Urbanism ideals are translated into a different context.

4. Method

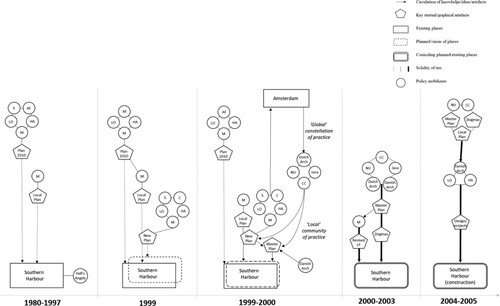

This paper draws mainly on qualitative research methods used to explore the historical narrative (Montgomery Citation2016) of the case study (Sydhavn, Copenhagen) and highlights the process of translation of imported urban design/development ideas. Within the Sydhavn area, special attention is given to the Sluseholmen scheme, inspired by Dutch architecture and incorporating New Urbanist and Compact City perspectives. The analysis of the historical narrative of the project is aimed to define a timeline with project phases. Each phase is a result of interconnected policy mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters – a term coined in this paper as a variant of McFarlane’s ‘coordination tools’ (McFarlane Citation2011b, 364) focusing only on events. The combination between an ANT-sensitivity and the use of a historical narrative approach enables ‘the potential of narratives to be simultaneously descriptive and explanatory by fostering an explicit deployment of temporal order, connectedness, and unfolding of events’ (Ponti Citation2012, 1).

For the analysis of the narrative, ten semi-structured interviews with thirteen persons, conducted during the first six months of 2019, were directed to a wide range of actors representing different profiles, including two residents, retired from work; two residents, children; one resident, blogger and local guide; one resident and consultant in the architectural firm; one developer; two architects; one planner from the Copenhagen municipality; two architects from the Copenhagen municipality; and one politician. The snowball sampling technique was used taking into account the need to ensure diversity of stakeholders’ profiles.

Moreover, document analysis of planning documents and relevant literature was added to obtain further information about the historical process and involvement of actors as policy mobilizers in the Sydhavn and Sluseholmen in particular. The following themes were considered for the coding of interviews and documents: New Urbanism; post-modernism; compact city; Copenhagen local character; actors as mobilizers; process steps; and mutation.

5. Contextualization of case study

5.1 The inner-city focus and the compact, mixed-use development approach in Copenhagen before the Southern Harbour regeneration

The continuous urban area of Copenhagen, which includes several municipalities, has around 1.3 million inhabitants. The central municipality, the City of Copenhagen (henceforth Copenhagen), had around 620,000 inhabitants in 2019 (source: https://www.statbank.dk/) and is growing with about 10,000 inhabitants every year – a growth which has been going on for more than two decades. However, during the 40 years prior to that, Copenhagen experienced a steep decrease in population, mainly caused by suburbanization, decay of inner-city areas and deindustrialization (Bamford Citation2009). The turn came in the 1990s with a new interest in inner-city locations for living and working and a new political focus on rehabilitating urban areas (Jørgensen and Ærø Citation2008), including the decision to build the Øresund bridge and tunnel, the Copenhagen metro, an extension of the airport, various public and cultural institutions and the new urban district Ørestad. This was also mirrored in the return of private investment (Andersen and Winther Citation2010). According to Urban (Citation2019, 4), an important contribution towards an approach based on urban regeneration, urban compaction, liveability and sustainable development came from Jan Gehl, whose ‘model of a dense, mixed-use city dominated by pedestrians and cyclists was often mentioned in Copenhagen’s strategic plans and political programs’ since the 1990s. Urban (Citation2019) also mentions two more factors that favoured such an inner-city regeneration focus. First, the crisis of the Danish welfare state producing a shift from institutionally controlled planning and construction towards a more market-based urban development approach (Hansen and Engberg Citation2017). Second, specific changes in housing policies and subsidies including deregulation for cooperative housing that led to an increase in prices (Kristensen Citation2007).

5.2 The Sydhavn plan: case study description and justification

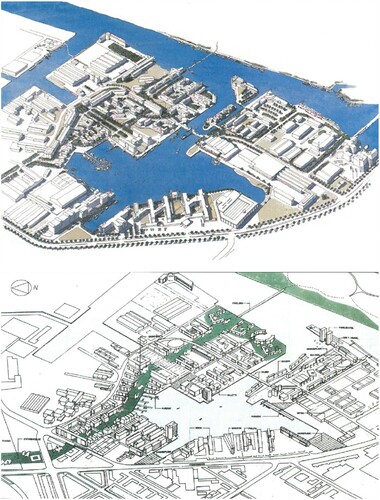

The case study for this paper is the Southern Harbour (Sydhavn in Danish) of Copenhagen, Denmark. Since the 1990s, the area has undergone a process of regeneration from being obsolete, almost neglected dockland with a heavy industry past to a mixed-use urban district. In 2009, it won the Danish Urban Planning Award ‘for the fine proportions and emphasis of the human scale’ (Danish Town Planning Institute Citation2009). The Sydhavn masterplan, from the beginning of the twenty-first century, incorporated the Compact City and New Urbanism concepts as well as inspiration from Dutch architecture. The Dutch influence came from the masterplanner, Sjoerd Soeters, a post-modern architect who took inspiration from his Amsterdam’s Java Island project () and Adriaan Geuze’s Borneo-Sporenburg scheme (Abrahamse and Buurman Citation2006), which can be set against the backdrop of a historical Danish-Dutch connection in urban development.

Figure 1. Compact and dense urban development on Java Island, Amsterdam. Courtesy of Sjoerd Soeters.

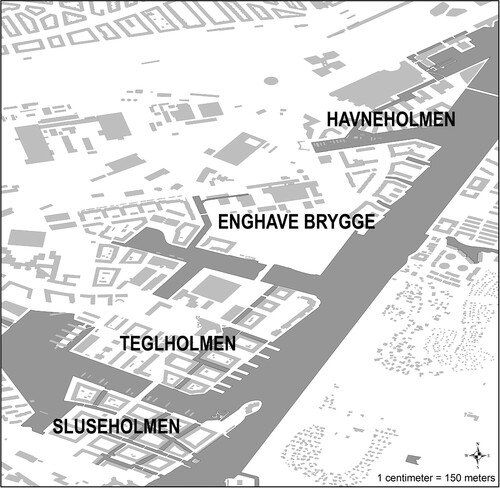

In Sydhavn, Soeters’ post-modernism is forged through a structure of canals and direct frontage of buildings into the water, resembling Amsterdam and even Venice (Smith and García Ferrari Citation2012). Such a nostalgic reinterpretation of the past in the architectural and urban form provides the project with a New Urbanist flavour. Moreover, the masterplan proposed a compact morphology of urban blocks and the inclusion of a mixed-use boulevard. While the compact city and New Urbanism concepts were more or less explicitly addressed in the original masterplan by Soeters – as, usually, compact city and New Urbanism projects tend to be masterplanned – the later intervention of the different land buyers, developers and builders in the project produced a juxtaposition of diverse forms. Hence, the translation process from a masterplanned development into a mosaic of different urban forms should be given special attention as well as a reflection on what remains of the initial compact city and New Urbanism ideas in the project outcome. At present, only the sub-areas named Sluseholmen, Teglholmen and Havneholmen are developed fully or in part (), with the first case being the one where the import of international urban knowledge concepts is more evident.

6. Analysis of policy mobilizers and travelling concepts: historical narrative

In this section the historical narrative of the Sydhavn is described and structured into development phases, highlighting the main actors as policy mobilizers of each phase. The textual information of the narrative is complemented with specific tables referred to each phase. Each table is not a repetition of the text but instead summarizes in one place altogether the key events of each phase, the actors, enrolled artefacts, as well as coordination encounters necessary to the translation of New Compactism in the Southern Harbour.

6.1. Phase 1: until the 1990s

The Southern Harbour was developed as an industrial harbour in the 1870s. By the 1920s, with the arrival of international car manufacturers, the area came to be known as ‘Little Detroit’. Similar to other industrial areas in the city, the harbour progressively lost its industrial function from the 1970s and became a meeting place for gang members and prostitution. The presence of these actors contributed to the decay and bad reputation of the area and triggered a political response. During the 1980s, several plan proposals for the harbour were developed by different actors (the harbour administration, the state and the municipality), but none of them were ultimately realized. From 1984, small citizen groups started to emerge and use part of the harbour for recreational purposes, financing and developing, among other things, the Islands Brygge harbour park. More information about this phase is included in .

Table 1. Phase 1: Summary of key events, actors/mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters.

6.2. Phase 2: 1990–1997 – recovery of Copenhagen

At the turn of the decade, following the recovery of Copenhagen’s economy, construction of office buildings along the harbour area began, prompting the cleaning of the water and putting the harbour in new focus. Yet, as it stood, the 1993 Municipal plan still conceived the harbour area for port-related conventional functions (e.g. mercantile and logistics). The main actors/mobilizers of this phase (see also for more information) were composed of an emerging office building industry, the local Danish architectural firms and property developers who expressed their interest in rehabilitating the area.

Table 2. Phase 2: Summary of key events, actors/mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters.

The first construction projects (mostly office buildings and hotels) took place in a central part of the harbour area, Kalvebod Brygge. This development was monofunctional and criticized for its design, which isolated the city from the harbour with long buildings running in parallel to the waterfront and without public space in front. At the time, the idea of a compact and dense development was still not in vogue and there was no reference to any postmodern or New Urbanist development approach in planning documents. Furthermore, the shape of the real estate market precluded the introduction of mixed uses. Housing construction was at an all-time low, and there was scepticism around the notion that housing could be attractive and sold in the harbour (Bisgaard Citation2010).

6.3. Phase 3: 1997–1999 – plans for the redevelopment of the harbour

In 1997, the harbour administration met with landowners to elaborate a comprehensive plan (i.e. ‘Plan 2010’) for the port area together with Danish architectural firms, such as Arkitektgruppen Aarhus, later renamed as Arkitema (Havn and Kjærsgaard Citation1997). This plan proposed large office development, but also included residential buildings in various locations within the harbour. According to Faber (Citation1998), the lead developer of the harbour administration, Karl-Gustav Jensen, declared in 1998 that Copenhagen was lacking housing along the waterfront area and that housing was needed for a positive development of the harbour. This can be considered as the first sign of a paradigm shift in terms of urban development ideas, towards a more mixed-use type of development () which is at the core of compact city ideals. Still, the focus was on the use of buildings rather than other compact city principles, like the quality of public space, social interaction or diversity.

Figure 3. The beginning of a new mixed-use development approach. On the top, illustration from Plan 2010 by the Harbour, showing a bridge connecting Sluseholmen and Teglholmen and a variety of office and residential buildings mainly formed as long blocks, referring to typical harbour warehouse buildings (Havn and Kjærsgaard Citation1997). On the bottom, illustration from the local plan (Københavns Kommune Citation1998), adding a green wedge and more housing.

Together with the municipality, the general harbour plan was further developed (e.g. by adding a green wedge going east–west) and simultaneously a local plan, a legally binding plan to regulated urban development, for the part of the Southern Harbour called Teglværkshavnen (Sluseholmen and Teglholmen) was initiated (Københavns Kommune Citation1998). A different approach to the redevelopment of the harbour started to emerge, including ‘quality buildings using the special qualities of the water area. There should be place for architectural new-thinking and experiments in new construction’ (Havn and Kjærsgaard Citation1999, 1). Even if the ‘Plan 2010’ and the first local plan of Sluseholmen/Teglholmen still had ‘strong modernistic ideas regarding light, air and view lines’, it highlighted that ‘it should be possible to see the water from the street behind the buildings. This was a dogma at all other locations in the city in the 1980s/1990s. It was the first planning principle in Southern Harbour’ (Christiansen and Stamer Citation2015, 240).

The city council adopted the Local plan Nr 310, based on the aforementioned ‘Plan 2010’, on 16 June 1999. Office construction continued in the Southern Harbour, including the local headquarters of Nokia (now Aalborg University) and Daimler/Benz, still in the form of modernistic rectangular office buildings. Further, in 1999, the first public harbour baths were built, setting a new precedent beyond office that provided a clear ‘indication of a potential for developing the area’, as one resident/blogger told us during an interview. The key events, mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters of this phase are displayed in .

Table 3. Phase 3: Summary of key events, actors/mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters.

6.4. Phase 4: 1999–2000 – a new masterplan for Sydhavn

Around 2000, the ‘Copenhagen Harbor was (…) quite desperate for a different kind of business’ (Interviewee. Architect, municipality of Copenhagen) that could give new life to the harbour area. As a policy mobilizer (see for more information on this and other mobilizers), the municipality had a twofold role embodied by its technical and financial departments.

Table 4. Phase 4: Summary of key events, actors/mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters.

Whereas the Local Plan nr 310 had been adopted in mid-1999 due to the work of the municipality’s technical department, the financial department responsible for the municipal plan, a higher-level urban development plan for the whole city, was lobbying for the elaboration of a new plan for the whole harbour. On 6 May 1999, the city council agreed to start such a process, to be completed within a year. A steering group, a secretariat and a contact group were established. Members were overlapping and came from the municipality (from both aforementioned departments), the state (Ministry of the environment), the public landowner company (Freja) and the harbour. The group decided quickly to work with three focus areas (north, inner and south) instead of the harbour as a whole. The focus was ‘mainly on participation from the different groups of political institutions involved and on developers, rather than on the residents or existing small businesses’ (Smith and Garcia Ferrari Citation2012, 182).

From the very beginning, the steering group agreed to obtain inspiration from other projects in Europe. The rationale, as an architect working at the municipality of Copenhagen told us, was that ‘in town planning, you are allowed to take references. When you see something beautiful in another part of the world, you can steal it’. Thus, fieldtrips were organized to new urban developments in Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin, Hamburg, Malmö and Oslo. In the end, Amsterdam has deemed the most appropriate inspiration for the redevelopment of the harbour.

The steering group decided to hire two Dutch architects, Sjoerd Soeters for the Southern Harbour and Adriaan Geuze for the Northern Harbour. There was an initial reluctance about their involvement on the part of the Danish architectural community and local planners, who ‘were against it because they thought they were the ones who should do it’ (Interviewee. Architect and masterplanner). For some of the disgruntled, a notable issue of contention was their desire to keep with tradition and develop ‘simple buildings’ that would be evocative of traditional harbour warehouses (‘pakhus’), rather than adopting a foreign style, as a chief planner from the municipality mentioned in an interview.

In particular, the acceptance of post-modern or New Urbanist ideas was initially problematic so these concepts were introduced with some difficulties, as stated in the interviews. Despite this, the involvement of the Dutch architects effected a shift from the initial modernistic or office-oriented urban development ideas dominating the Danish planning imagination for the harbour into what can be considered as a combination of post-modernist and compact city principles.

If there is one thing we agree on in Denmark, it is that post-modernism in architecture is no good. (…) You know when we got down to the project, it actually turned out the ideas that Sjoerd has regarding urban planning are very interesting and very easy to translate into Danish architecture and Danish contexts. (Interviewee. Architect, private Danish firm)

In mid-2000, the new plans for three parts of the harbour were presented publicly in an exhibition with about 20,000 visitors, according to an informant at the municipality. Particularly relevant in terms of policy mobilization was the role of the local press, which shaped public opinion and ultimately contributed to the legitimation and success of the project and also acted as an intermediary between local authorities and residents. ‘The press was very impressed. They thought we had done a good work. The clue was that we had made housing in the harbour and not offices. People want to go down to the harbour’ (Interviewee. Planning Department, Copenhagen municipality).

That same year, the New Urbanist flavour was invoked in Soeters’ first masterplan for the Southern Harbour. But the implementation of New Urbanism was a matter of debate. It was recognized as an inspiration in terms of broad principles, but also criticized by some actors for not being ‘place-specific’, as one architect and masterplanner put it. For this reason, the reinterpretation of New Urbanist ideas, in the application of Soeters’ post-modernism to the Sluseholmen case, took inspiration, on the one hand, from foreign influence, particularly looking at Amsterdam and Venice and, on the other, from local Copenhagen historical areas – e.g. Christianshavn. Soeters’ masterplan used historical developments in these three cities as references and examples for densities, urban design, mixed-use development and the compaction of public spaces. At a later stage, social housing was included in the plan to promote social diversity. However, the masterplan already highlighted the need for a mix of different housing types for balanced city development.

Specifically, the 2000 masterplan included a mixed-use boulevard with retail on the ground floor, contributing to the rising of a compact city concept in the area. A mutation from the inspirational Amsterdam Java’s project towards enhanced densification and intensification of use of the leftover public space () was achieved ‘by introducing the crossing canals and having the buildings with one foot in the canal’, as one architect and masterplanner explained.

In general, in terms of planning and design, the interviewees noticed how urban design concepts are reformulated and improved when travelling.

You have to do it better and you have to translate it into Danish traditions and architecture. So, my point of view is, that we did translate this. (Interviewee. Architect, municipality of Copenhagen)

The thing that struck me more in Amsterdam was that it was more uniformed, it was more kind of regimental; straight lines. The canals here are more curved. It feels friendlier here. As I remember, there was some difference in the facades. It was quite child-friendly in Amsterdam. I get the sense that this is more diverse and even more compact, more densely populated. In Amsterdam, I got the sense that it was more spread out. (Interviewee. Resident, guide and blogger)

6.5. Phase 5: 2001–2004 – translating and detailing the masterplan and the plan for Sluseholmen

This phase was characterized by a range of policy mobilizers () intervening in different aspects of the Southern Harbour redevelopment ().

Figure 5. First Soeters’ masterplan from 2000 top (Soeters van Eldonk architecten Citation2000), and final comprehensive plan from 2002 bottom (City of Copenhagen Citation2004).

Table 5. Phase 5: Summary of key events, actors/mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters.

The Harbour administration was the owner of most of the land, while from 2001 the land developers formed a consortium and collaborated with the municipality, Arkitema and the Harbour administration. They all collaborated in the revision of the masterplan, although ‘Soeters was 100% the most important person in developing the idea behind the master plan’ (Interviewee. Architect, private Danish firm).

The Danish architectural firm Arkitema had a key role within policy mobilization, involving a process of mediation and translation which is particularly well described in the interviews:

We were engaged by the land buyers. Sjoerd Soeters was engaged by the land owners. Our job was first and foremost to translate Sjoerd Soeters masterplan to a Danish local plan. And our job was, on the developer side, to bring the local plan to life, so that developers could measure the square metres, the building costs, whatever. Actually, we had a very close collaboration with Sjoerd Soeters in the process of developing the local plan. (Interviewee. Architect, private Danish firm)

The Arkitema role was to bring the urban development to life. How should we transform this very overall idea about a masterplan to actually a new city which could be built according to Danish building laws, Danish building tradition, could be sold to Danish housing consumers and so on. (Interviewee. Architect, private Danish firm)

We copied that and decided that we should have 10 architectural dogmas in Sluseholmen. (…) An example of an architectural dogma was that no two houses could have the same height. They had to have variation. No two houses could have the same windows, entrances, colors and so on. (Interviewee. Architect n.2, Copenhagen municipality)

In the dogmas, we stated that every courtyard should have a certain typology from Venice; to get from the courtyard, directly down to the canal. (…) Yes, the houses all going down into the water, is Venice inspired. (Interviewee. Architect n.2, Copenhagen municipality)

Within the translation process, the local conditions of land have had a clear impact on the project.

Well, there was physical local context, there was of course silo-buildings, there was the power plant that has a kind of environmental circle around it, there was a loading dock for the power plant, and there was an explosion risk, there were office buildings and buildings where they experimented with diesel engines for ships. So, there were a load of environmental issues. (Interviewee. Architect and masterplanner)

At the same time, the flexibility of local planning has had an impact on the possibility to alter initial ideas or design proposals and the design manual was part of such an open-minded urban planning approach.

The local plan at that time, it was quite simple. Here you must build in this height, this building percentage is … and so on. Then we introduced the design guide but it wasn’t a part of the local plan. So, if we, together with architects from the municipality, decided to change something, because we got a new idea, we could do it without asking the politicians. (Interviewee. Former developer)

6.6. Phase 6: from 2004 – construction of Sluseholmen and Teglholmen

This phase starts with the construction of Sluseholmen. The main actors/mobilizers (see , including those and other actors of phase 6) involved in the Sluseholmen development were the municipality, the aforementioned developers and a Swedish building contractor who implemented an egalitarian system of construction based on the repetition of the same construction units and residents moving into the area.

Table 6. Phase 6: Summary of key events, actors/mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters.

A joint company for the site development was created, Sluseholmen A/S. It was terminated in 2012, soon after all construction finished. Sluseholmen was built with ‘a Swedish construction system; all the apartments in Sluseholmen are placed on the water and (…) are totally equal’. The variation in the facades was then created in spite of such an egalitarian construction system and it was not well accepted by local architects in the beginning. As noted in the interviews, ‘it is a bit fake to create the differences on the facades. But we did that. And that was a task, from my point of view, as an architect’ (Interviewee. Architect n.2, Copenhagen municipality).

According to the interviewees, the economic crisis of 2007–2008 clearly affected the development of Sluseholmen and Teglholmen. In Sluseholmen ‘the last contractor was commissioned 2005 (…) and then the finance crisis started 2007/2008 (…) when we were in the early beginning of Teglholmen’ (Interviewee. Architect, private Danish firm). This caused an interruption in the development of Teglholmen between 2007 and 2012. In 2009 the municipality won the Danish Town Planning award (‘Byplansprisen’) for Sluseholmen although the expectancy for a mixed-use, compact and accessible area was in part unattended. A mutation of the initial urban compaction concept emerged when the first residents moved in and the mixed-use and compact city idea was missing, since ‘there were much less people, obviously. Nothing on this street. No shops’ (Interviewee. Resident and consultant in Danish architectural firm).

Moreover, transport and accessibility were particularly problematic as

in the beginning, it was much more comfortable to get here in a car, because you had to go all the way around. And it was muddy and dark. The bus connections were very bad. There was no harbour bus and no cycling. (Interviewee. Resident and consultant in Danish architectural firm)

Another significant aspect within this gap between theory and implementation in terms of compact city principle is related to public spaces, which emerge in the interviews as lacking and working well exclusively in certain seasons, e.g. summer or for certain age categories, e.g. smaller children playing in the yards. The role of local residents in Sluseholmen emerges in the interviews in relation to self-management and selforganization of local initiatives, as for example, ‘Miljøkajakken’, where residents collect plastic and rubbish in the harbour. More formally, ‘each island has its own kind of committee that takes care of (…) practical issues, investments, developments of the buildings, things like that’ (Interviewee. Resident, guide and blogger). Notwithstanding, the interviewees also highlighted that social media have become the reference for residents to discuss local issues, more than formal institutions.

Besides Sluseholmen, Teglholmen is probably the place where the most significant mutation from the original Dutch travelling ideas and their resulting Danish reinterpretation took place. This area is still under construction. Particularly, in Teglholmen and the rest of the Southern Harbour, the initial coherence of the original Sydhavn’s masterplan is lost. According to the interviews, developers and local authorities ‘neglected the total plan completely (…). They just look at time and money and they have not clue for quality. So if you see the difference of the first phase and what they did after, it’s shocking’ (Interviewee. Architect and masterplanner). Therefore Teglholmen ‘was messy and it felt like a lack of intimacy. ‘Where is the public space’. It felt like a no place. It was like the buildings had been dumped there’ (AR). The focus has increasingly been towards profit at the expense of architectural quality, as stated in the interviews. After Sluseholmen, and after the financial crisis most of all, ‘they just wanted to have ‘a quick fix’; a lot of things going on, just for the money’ (Interviewee. Architect, municipality of Copenhagen).

As a result, Teglholmen ‘hasn’t been the very compact and intense process as it has been on Sluseholmen’ There, ‘projects are seen more as solitary architectural pieces, more than a coherent tight woven together cityscape (…) the municipality had the chance to set the team right’ but ‘they didn’t have the capacity and the time to very tight follow up on the architects so they could change direction to try to make a more coherent, precise architectural expression in the development’ (Interviewee. Architect, private Danish firm).

7. Sluseholmen as a model? From idealization to mutation

Sluseholmen has become a model for later urban development, as

the project became an eye-opener for how to build along the long Danish waterfront. It became a simple plan with small but articulated variations together with a relatively high floor-area ratio for a pure residential area which clearly takes distance from functionalist planning doctrines. (Lund Citation2016, 153, own translation)

To back up this idea of Sluseholmen as a model for future projects, several exemplary outcomes of the Southern Harbour development have been underlined in the interviews, including compact city qualities such as its bike-friendly environment, the presence of social housing and the role of the Teglholmen’s school as a social catalyst. Particularly, the yards within the blocks have played an important role in sustaining social interactions, depicted in the interviews as a semi-public space where people meet each other.

The translation and contextual mutation of New Compactism in Sluseholmen also led to controversial outcomes. Several critical aspects have been raised by the interviewees undermining the successful application of compact or neotraditional city principles in the final outcome of the Sluseholmen project. Such factors might hinder the idea of replicability and idealization of Sluseholmen as a model of New Compactism. For instance, the interviewees agree that there is some degree of mixed-use on Sluseholmen and Teglholmen, although the residential character is still predominant.

I think it is about 80/20. (…) On Teglholmen, we have TV2 news, we have the university, there is a Hugo Boss down the road. So, there is an emphasis on commercial uses on this side. However, on Sluseholmen North, there is also commercial and small business like this. [the café they are sitting in] There should be more but it takes time. (Interviewee. Resident, guide and blogger)

One specific element pinpointed in the interviews as a failure in terms of defining Sluseholmen as mixed-use compact development is related to the use of ground floors for retail.

But of course, one thing is saying: ‘we want to have shops at the ground floor.’ You can say whatever you want but if the market does not … (…) I think we probably have to be a bit more innovative on how we should use the ground floors. (Interviewee. Former politician)

Another problematic aspect which was mentioned in the historical narrative of Sydhavn was the deficiency in the phasing of public transport, which was improved gradually and will be enhanced with the future implementation of a new metro line. The connection with the old part of Sydhavn is still problematic and the outflow of inhabitants from Sluseholmen towards the old Sydhavn, for example for cultural events, is not compensated by an inflow arrival of people from there.

The main thing is connecting the new part of Sydhavn to the old part (…). I think, more people living here will probably go into the old part, because there are some great places to visit but it is difficult to get the people from the other side to visit here. (Interviewee. Resident, guide and blogger)

So the mix gets lost. You see that in all successful cities prices go up and less wealthy people get pushed out.(…) Neoliberalism is wrecking our cities in the end. (Interviewee. Architect and masterplanner)

8. Discussion and conclusions

This study shows how, in the Sydhavn redevelopment, policy mobilizers, enrolled artefacts and coordination encounters interact and reshape urban development ideals forged in the global constellation of practice. The empirical material of this case shows the complexity inherent to the process of translation, from abstract concepts (compact city, New Urbanism) shaped by concrete objects in remote locations (Java Island), towards their local reinterpretation and concrete implementation (Sluseholmen), in a movement through time and space.

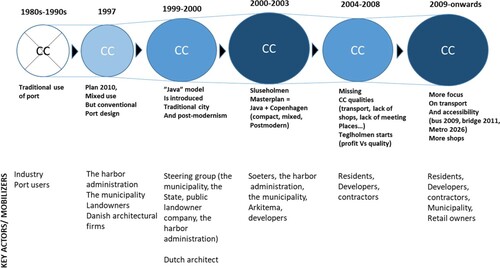

The historical narrative approach has gone beyond the production of a project timeline (which served as a starting point) with its corresponding phases. By introducing an ANT-sensitivity, this research contributes to the theoretical corpus about policy mobility resulting from the circulation of knowledge between humans and non humans and its evolution over time. Here, Sluseholmen and Sydhavnen are a complex product of different interactions and relations changing over time (, ANT-based diagram). The planned vision of places is not a fixity that is merely ‘implemented’ or rendered ‘concrete’; rather, its ‘implementation’ is contingent upon the (not simply discursive but emphatically material) negotiations and associations between different actors, which, as the project unfolds, make the planned vision evolve and gradually become stabilized in the actuality of the built place, as displayed in .

Figure 6. ANT-based diagram showing circulation and ties of places, artefacts and policy mobilizers.

Moreover, the research has shown how apparently ‘external’ factors (e.g. economic crisis, difficult market for retail units on ground floor) set new conditions for local alliances, bringing about new concerns and shaping new compromises, ultimately contributing to the mutation of initial ideas. In the relational ontology of ANT, actors move in a flat, immanent landscape; actors are actors insofar as their emergence has an effect on other actors. That is to say, there are no ‘internal’ or ‘external’ factors, only effects.

As ‘spatial concepts are not stable over time’ (Hajer and Zonneveld Citation2000, 341), from research findings, a compact city appears in the Sydhavnen/Sluseholmen redevelopment as a fluctuating concept with variable ontology (). That is, the concept of the Compact City was forged in relational patterns of the association through time, ‘reinvigorated’ through its ‘reinterpretations’ (Vicenzotti and Qviström Citation2018, 120) and intersected with the New Urbanist urban design from the end of 1990s. These ideals were enacted into being and combined in situated practices as shown in our findings. Both concepts, the Compact City and the New Urbanism, moved along three interlinked vectors of translation: (1) form, from abstract to concrete when implemented in urban planning, urban design and building/space construction; (2) time, as shown in the historical narrative; and (3) space, from one context to another through policy mobilizers, artefacts and coordination encounters. Within the group of policy mobilizers, a specific role is embodied by the local community of practice which locally translates the New Urbanism and Compact City concepts circulating globally in the ‘wider constellations of practice’ (Faulconbridge Citation2010, 2855). The latter is travelling by means of ‘incoming policy consultants’, as part of the ‘global policy consultocracy’ (McCann Citation2011, 114), such as the Dutch architects.

Figure 7. Translating the compact city (CC) through different mutations, including the introduction of a post-modernist design approach at the end of 1990s.

Through the action of a local community of practice within the local context, this research has overcome the idea that urban development should be based on leading paradigms and the international transfer of allegedly replicable best practices. Here, the compact city and New Urbanism are re-interpreted locally as the local community of practice is inspired by global constellations of practice but, at the same time, is giving something back to the global constellation of practice, for example, Dutch architects influenced by Copenhagen’s tradition of urbanism. Our research also calls into question common understandings of the global/local duality in planning discourse. ‘Global’ ideas or best practices do not stand on some metaphysical realm ‘beyond’ the local. Rather, the adjective ‘global’ attaches itself to things that have been ‘globalized’ (Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996), that is, things that are enlisted to form an extended network of interconnected localities. As our findings demonstrate, ideas and policies that make up these extended networks are redefined and transformed as they connect and expand in new contexts (e.g. New Compactism), which challenges unilinear, top-down notions of policy implementation. In this sense, we contribute to a more nuanced understanding of mobility that falls under ‘the local globalness’ approach to policy transfer (McCann Citation2011). Further, our empirical insights contribute to calls to take seriously the role of apparently mundane practices in shaping and facilitating the travels of policy (McCann Citation2011). Our case lends itself to these efforts by providing an empirical account of the genesis and development of the Sluseholmen project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahamse, J. E., and M. Buurman. 2006. Eastern Harbour District Amsterdam: Urbanism and Architecture. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers.

- Adelfio, M., I. Hamiduddin, and E. Miedema. 2021. “London’s King’s Cross Redevelopment: A Compact, Resource Efficient and ‘Liveable’ Global City Model for an Era of Climate Emergency?” Urban Research & Practice 14 (2): 180–200.

- Adelfio, M., J-H. Kain, L. Thuvander, and J. Stenberg. 2018. “Disentangling the Compact City Drivers and Pressures: Barcelona as a Case Study.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography 72 (5): 287–304.

- Albrecht, M., J. Kortelainen, M. Sawatzky, J. Lukkarinen, and T. Rytteri. 2017. “Translating Bioenergy Policy in Europe: Mutation, Aims and Boosterism in EU Energy Governance.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 87: 73–84.

- Amin, A., and J. Roberts. 2008. “Knowing in Action: Beyond Communities of Practice.” Research Policy 37 (2): 353–369.

- Andersen, H. T., and L. Winther. 2010. “Crisis in the Resurgent City? The Rise of Copenhagen.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34 (3): 693–700.

- Arkitema. 2003. Sluseholmen. Oplæg til tekst for arkitektoniske retningslinjer. [Sluseholmen. Proposal for architectural guidelines]. Arkitema.

- Audirac, I., and A. Shermyen. 1994. “An Evaluation of Neotraditional Design’s Social Prescription: Postmodern Placebo or Remedy for Suburban Malaise?” Journal of Planning Education and Research 13: 161–173.

- Baker, T., and C. Temenos. 2015. “Urban Policy Mobilities Research: Introduction to a Debate.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (4): 824–827.

- Bamford, G. 2009. “Urban Form and Housing Density, Australian Cities and European Models: Copenhagen and Stockholm Reconsidered.” Urban Policy and Research 27 (4): 337–356.

- Beauregard, R. 2002. “New Urbanism. Ambiguous Certainties.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 19 (3): 181–194.

- Bisgaard, H. 2010. Københavns genrejsning 1990–2010 [Copenhagen's Regeneration]. Nykøbing Sjælland: Bogværket.

- Boyko, C. T., and R. Cooper. 2011. “Clarifying and Re-conceptualising Density.” Progress in Planning 76 (1): 1–61.

- Callon, M. 1986. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation.” In Power, Actions and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge?, edited by J. Law, 196–233. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Campbell, S. D. 2016. “The Planner's Triangle Revisited: Sustainability and the Evolution of a Planning Ideal That Can't Stand Still.” Journal of the American Planning Association 82 (4): 388–397.

- Christiansen, J., and L. Stamer. 2015. Det ny København: Stadsarkitektens optegnelser 2001-10 [The new Copenhagen—Notes by the City Architects 2001-10]. Copenhagen: Strandberg Publishing.

- Churchman, A. 1999. “Disentangling the Concept of Density.” Journal of Planning Literature 13 (4): 389–411.

- City of Copenhagen. 2004. “Lokalplan Nr. 310-1&2 “Teglværkshavnen” [Local plan No. 310-1&2].” Københavns Kommune.

- Clarke, J., D. Bainton, N. Lendvai, and P. Stubbs. 2015. Making Policy Move: Towards a Politics of Translation and Assemblage. Bristol: Policy Press.

- CNU (Congress for the New Urbanism). 2000. Charter of the New Urbanism. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill.

- Cook, I., and K. Ward. 2012. “Relational Comparisons: The Assembling of Cleveland’s Waterfront Plan.” Urban Geography 33 (6): 774–795.

- CORDIS (Community Research and Development Information Service). 2015. “Final Report Summary – Newcompactism [WWW document].” Accessed 6 March 2020. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/103751/reporting/en .

- Cysek-Pawlak, M. 2018. “The New Urbanist Principle of Quality of Life for Urban Regeneration.” Architecture, Civil Engineering, Environment 11: 21–30.

- Czarniawska, B., and B. Joerges. 1996. “Travels of Ideas.” In Translating Organizational Change, edited by B. Czarniawska and G. Sevón, 13–48. Berlin, NY: De Gruyter.

- Czarniawska, B., and G. Sevón. 1996. “Introduction.” In Translating Organizational Change, edited by B. Czarniawska and G. Sevón, 1–12. Berlin, NY: De Gruyter.

- Danish Town Planning Institute. 2009. “Sluseholmen.” Byplan Nyt 2009 (4): 7.

- Danish Town Planning Institute. 2011. Fra Jakriborg til Sluseholmen – New urbanism i den virkelige verden [From Jakriborg to Sluseholmen – New Urbanism in real life].” Accessed 6 March 2020. http://www.byplanlab.dk/sites/default/files1/20110531FraJakriborgtilSluseholmen.pdf.

- Denslagen, W., and D. Gardner. 2009. Romantic Modernism: Nostalgia in the World of Conservation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Dieleman, F., and M. Wegener. 2004. “Compact City and Urban sprawl.” Built Environment 30 (4): 308–323.

- Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K. 2000. “Copenhagen in the Water.” [København i vandet.] Arkitekten 2000 (18): 2–9.

- EU. 2007. Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities. Final draft (2 May 2007). Accessed September 2021. http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/themes/urban/leipzig_charter.pdf.

- European Commission. 2011. Cities of Tomorrow – Challenges, Visions, Ways Forward. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Faber, K. 1998. “Når det grønne område er blåt.” Havn & By 6: 3–3.

- Faulconbridge, J. 2010. “Global Architects: Learning and Innovation Through Communities and Constellations of Practice.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42: 2842–2858.

- Faulconbridge, J. 2015. “Mobilising Sustainable Building Assessment Models: Agents, Strategies and Local Effects.” Area 47 (2): 116–123.

- Fertner, C., and J. Große. 2016. “Compact and Resource Efficient Cities? Synergies and Trade-offs in European Cities.” European Spatial Research and Policy 23 (1): 65–79.

- Garcia Ferrari, M. S., and D. Fraser. 2012. “Design Strategies for Urban Waterfronts: The Case of Sluseholmen in Copenhagen’s Southern Harbour.” In Waterfront Regeneration: Experiences in City-building, edited by H. Smith and M. S. García Ferrari, 177–200. London: Routledge.

- Garcia Ferrari, M. S., P. Jenkins, and H. Smith. 2012. “Successful Placemaking on the Waterfront.” In Waterfront Regeneration: Experiences in City-Building, edited by H. Smith and M. S. García Ferrari, 153–176. London: Routledge.

- Gorgolas, P. 2018. “El Reto De Compactar La Periferia Residencial Contemporánea: Densificación Eficaz, Centralidades Selectivas Y Diversidad Funcional.” ACE 13 (38): 57–80.

- Grant, J. 2003. “Exploring the Influence of New Urbanism in Community Planning Practice.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 20 (3): 234–253.

- Grant, J. L., and S. Bohdanow. 2008. “New Urbanism Developments in Canada: A Survey.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 1 (2): 109–127.

- Hajer, M. A., and W. Zonneveld. 2000. “Spatial Planning in the Network Society-Rethinking the Principles of Planning in the Netherlands.” European Planning Studies 8 (3): 337–355.

- Hansen, J. R., and L. A. Engberg. 2017. “Sydhavn, Copenhagen: Why Different Types of Self-Organization Have Varying Adaptive Qualities.” In Planning Projects in Transition: Interventions, Regulations and Investments, edited by F. Savini and W. Salet, 114–139. Berlin, NY: Jovis Verlag.

- Harris, A., and S. Moore. 2013. “Planning Histories and Practices of Circulating Urban Knowledge.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (5): 1499–1509.

- Havn, Københavns, and Hasløv Kjærsgaard. 1997. “Plan 2010 og bemærkninger til Forslag til Kommuneplan 1997.” [Plan 2010 and Comments on the Proposed Municipal Plan 1997].

- Havn, Københavns, and Hasløv Kjærsgaard. 1999. “Plan – Vision 2010: Status og visioner.” [Plan – Vision 2010: Status and Visions]. Københavns Havn.

- Healey, P. 2012. “The Universal and the Contingent: Some Reflections on the Transnational Flow of Planning Ideas and Practices.” Planning Theory 11 (2): 188–207.

- Healey, P. 2013. “Circuits of Knowledge and Techniques: The Transnational Flow of Planning Ideas and Practices.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (5): 1510–1526.

- Hirt, S. A. 2009. “Premodern, Modern, Postmodern? Placing New Urbanism into a Historical Perspective.” Journal of Planning History 8 (3): 248–273.

- Hofstad, H. 2012. “Compact City Development: High Ideals and Emerging Practices.” European Journal of Spatial Development 49: 1–23.

- Jenks, M., E. Burton, and K. Williams, eds. 1996. The Compact City: A Sustainable Urban Form? London: Spon.

- Jørgensen, G., and T. Ærø. 2008. “Urban Policy in the Nordic Countries—National Foci and Strategies for Implementation1.” European Planning Studies 16 (1): 23–41.

- Kain, J. H., M. Adelfio, J. Stenberg, and L. Thuvander. 2021. “Towards a Systemic Understanding of Compact City Qualities.” Journal of Urban Design. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2021.1941825

- Kain, J. H., J. Stenberg, M. Adelfio, M. Oloko, L. Thuvander, P. Zapata, and M. J. Zapata Campos. 2020. “What Makes a Compact City? Differences Between Urban Research in the Global North and the Global South.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 24 (4): 25–49.

- Kommune, Københavns. 1998. Planorientering: Lokalplanforslag “Teglværkshavnen” med tilhørende forslag til kommuneplantillæg [Plan Orientation: Local Plan Proposal “Teglværkshavnen” with Accompanying Proposal for a Municipal Plan Supplement].

- Kristensen, H. 2007. Housing in Denmark. København: Centre for Housing and Welfare – Realdania Research. Accessed 6 March 2020. http://boligforskning.dk/node/124.

- Latour, B. 1986. “The Powers of Association.” In Power, Actions and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge?, edited by J. Law, 264–280. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Longhurst, A., and E. McCann. 2016. “Political Struggles on a Frontier of Harm Reduction Drug Policy: Geographies of Constrained Policy Mobility.” Space and Polity 20 (1): 109–123.

- Lund, D. 2003. “Editorial: Byplanshopping.” [Urban Planning Shopping.] Byplan 2003 (2): 37–39.

- Lund, D. 2016. Den italesatte planlægning: Dansk byplanlægning 1992–2015. Nykøbing Sjælland: Bogværket.

- McCann, E. 2011. “Urban Policy Mobilities and Global Circuits of Knowledge: Toward a Research Agenda.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (1): 107–130.

- McCann, E., and K. Ward. 2012. “Policy Assemblages, Mobilities and Mutations: Toward a Multidisciplinary Conversation.” Political Studies Review 10 (3): 325–332.

- McFarlane, C. 2011a. “The City as Assemblage: Dwelling and Urban Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (4): 649–671.

- McFarlane, C. 2011b. “The City as a Machine for Learning.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 (3): 360–376.

- Medved, P. 2017. “Leading Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Europe: Exploring the Key Principles and Processes.” Urbani Izziv 28: 107–121.

- Mol, A. 2010. “Actor-Network Theory: Sensitive Terms and Enduring Tensions.” Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie 50 (1): 253–269.

- Montgomery, R. 2016. “State Intervention in a Post-war Suburban Public Housing Project in Christchurch. New Zealand.” Articulo - Journal of Urban Research 13. doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/articulo.2928

- Moore, S. 2013. “What’s Wrong with Best Practice? Questioning the Typification of New Urbanism.” Urban Studies 50 (11): 2371–2387.

- Moore, S., and D. Trudeau. 2020. “New Urbanism: From Exception to Norm—The Evolution of a Global Movement.” Urban Planning 5: 384–387.

- Neuman, M. 2005. “The Compact City Fallacy.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 25: 11–26.

- Newman, P., and J. Kenworthy. 2006. “Urban Design to Reduce Automobile Dependence.” Opolis: An International Journal of Suburban and Metropolitan Studies 2 (1): 35–52. Accessed 7 July 2021. http://repositories.cdlib.org/cssd/opolis/vol2/iss1/art3.

- OECD. 2012. Compact City Policies, A Comparative Assessment, OECD Green Growth Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Peck, J. 2011. “Geographies of Policy.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (6): 773–797.

- Peck, J. 2012. “Recreative City: Amsterdam, Vehicular Ideas and the Adaptive Spaces of Creativity Policy.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (3): 462–485.

- Peck, J., and N. Theodore. 2010a. “Mobilizing Policy: Models, Methods, and Mutations.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 41 (2): 169–174.

- Peck, J., and N. Theodore. 2010b. “Recombinant Workfare, Across the Americas: Transnationalizing “Fast” Social Policy.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 41 (2): 195–208.

- Ponti, M. 2012. “Uncovering Causality in Narratives of Collaboration: Actor-network Theory and Event Structure Analysis.” Forum: Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1659

- Prince, R. 2016. “The Spaces in Between: Mobile Policy and the Topographies and Topologies of the Technocracy.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34 (3): 420–437.

- Robinson, J. 2015. “‘Arriving At’ Urban Policies: The Topological Spaces of Urban Policy Mobility.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (4): 831–834.

- Rosol, M., V. Béal, and S. Mössner. 2017. “Greenest Cities? The (Post-)Politics of New Urban Environmental Regimes.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (8): 1710–1718.

- Smith, H. C., and M. S. García Ferrari. 2012. Waterfront Regeneration: Experiences in City Building. Routledge.

- Soneryd, L., and E. Lindh. 2019. “Citizen Dialogue for Whom? Competing Rationalities in Urban Planning, the Case of Gothenburg, Sweden.” Urban Research & Practice 12 (3): 230–246.

- Stead, D. 2012. “Best Practices and Policy Transfer in Spatial Planning.” Planning Practice and Research 27 (1): 103116.

- Tait, M., and O. B. Jensen. 2007. “Travelling Ideas, Power and Place: The Cases of Urban Villages and Business Improvement Districts.” International Planning Studies 12 (2): 107–128.

- Temenos, C., and E. McCann. 2013. “Geographies of Policy Mobilities.” Geography Compass 7 (5): 344–357.

- Tunström, M., J. Lidmo, and Á. Bogason. 2018. “The Compact City of the North – Functions, Challenges and Planning Strategies.” Nordregio Report 2018:4.

- UN-Habitat. 2012. Urban Patterns for a Green Economy: Leveraging Density. Accessed September 2021. https://unhabitat.org/leveraging-density-urban-patterns-for-a-green-economy.

- Urban, F. 2019. “Copenhagen’s “Return to the Inner City” 1990-2010.” Journal of Urban History 47 (3): 651–673.

- van Eldonk architecten, Soeters. 2000. “Masterplan COPENHAGEN Sydhavnen.” Phase 1.

- Vicenzotti, V., and M. Qviström. 2018. “Zwischenstadt as a Travelling Concept: Towards a Critical Discussion of Mobile Ideas in Transnational Planning Discourses on Urban Sprawl.” European Planning Studies 26 (1): 115–132.

- Villadsen, J. 2006. “De Udenlandske Arkitekter [The Foreign Architects].” KBH 16: 14–22.

- Ward, K. 2006. “Policies in Motion’, Urban Management and State Restructuring: The Trans-Local Expansion of Business Improvement Districts.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30 (1): 54–75.

- Westerink, J., D. Haase, A. Bauer, J. Ravetz, F. Jarrige, and C. B. E. M. Aalbers. 2013. “Dealing with Sustainability Trade-Offs of the Compact City in Peri-Urban Planning Across European City Regions.” European Planning Studies 21 (3): 473–497.

- Wood, A. 2016. “Tracing Policy Movements: Methods for Studying Learning and Policy Circulation.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (2): 391–406.

- Wood, A. 2019. “Circulating Planning Ideas from the Metropole to the Colonies: Understanding South Africa’s Segregated Cities Through Policy Mobilities.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 40 (2): 257–271.

- Wood, A. 2021. “Policy Mobilities: How Localities Assemble, Mobilise, and Adopt Circulated Forms of Knowledge.” In Companion to Urban and Regional Studies, edited by A. M. Orum, J. Ruiz-Tagle, and S. V. Haddock, 1st ed., 329–348. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Zhang, R., and B. Gao. 2018. “Eco-city Planning in China.” In Vertical Urbanism, edited by Z. Lin and J. Gámez, 210–220. London: Routledge.