ABSTRACT

The global comparison of planning systems faces several theoretical and normative challenges. Against the background of ongoing debates on the comparability of emerging and existing ideas and practices of planning in the Global North and South, we propose a comparative approach based on field theory. Comparisons of planning systems often focus on the institutional dimension or are mere juxtapositions of cases studies. A comparison based on field theory is more appropriate for the comparative study of planning cultures as the approach allows to interpret planning as an emerging practice influenced (or not) by globalized or European knowledge communities. The two planning systems under scrutiny in this paper are Germany and Brazil. Germany presents a mature field of planning while Brazil’s field of planning is emergent. The paper is based on a literature review that supports the formulation of assumptions and tests the approach through a comparison of Brazil and Germany.

1. Introduction

Comparative studies of regions and cities in geography and urban studies are frequent, and these studies address many different aspects (Keil Citation2017; Robinson Citation2016; Schmidt et al. Citation2021). In addition, comparisons between local government systems and urban policies are common. Comparative studies in the planning sciences do not have such a long tradition and rich discourse in terms of their methods and theories. Although it is difficult to define a clear start date, comparative planning studies began in the 1990s in a more comprehensive way. This was triggered by a desire to learn from the experiences of other countries, particularly in Europe (Nadin and Stead Citation2013). In Europe, the integration process has driven comparative studies of systems, cultures and practices of territorial governance and planning since the 1990s (CEC Citation1997; Nadin and Stead Citation2013; Rivolin Citation2008). The number and density of cross-references of publications shows that a resurgence of interest in international comparative studies with a stronger focus on methodological issues took place in the European context (Nadin and Stead Citation2013, 1543; see Appendix). However, the global comparison of planning systems lags behind Europe and is a more recent phenomenon. Global comparisons face several theoretical and normative challenges and many contributions in the field of comparative urbanism in the context of post-colonial studies point to the hidden normative assumptions of many studies (McFarlane and Robinson Citation2012; Robinson Citation2016; Watson Citation2016). Often, a study’s reference point is not clarified and it is accused of being centred on Western culture.

Spatial planning has been institutionalized as a practice conducted around the world by people who consider themselves planners. However, is this fact strong enough to constitute a frame of reference for a systematic comparison that goes beyond an instrumental north–south policy transfer? This paper will discuss this question and suggest an approach for the global comparison of planning systems and planning cultures, with Germany and Brazil as illustrative case studies. The two countries have little in common, except for the fact that they are federal states. Concerning the challenges of territorial development and the maturity of planning systems, their differences could not be greater. Brazil’s metropolitan cities and urban regions constitute extreme challenges in terms of spatial planning, infrastructure management, and housing policies. Other areas in Brazil have severe social and environmental problems. Many of these problems are non-existent in the German context. In the European discourse, the German planning system is considered comprehensive, integrative and mature, while still underperforming in the reduction of land consumption (Schmidt et al. Citation2021; Siedentop, Fina, and Krehl Citation2016). A comparison of these two profoundly different systems will illuminate something about the universal aspects of planning. This question is also raised against the backdrop of contemporary global challenges and the driving forces that change global planning discourse, such as climate change or extensive urbanization. Global agendas and agreements such as the New Urban Agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement have facilitated the emergence of global platforms and knowledge communities dealing with contemporary social-environmental trends and challenges that constitute common points of reference for global urban policies (Pieterse Citation2010; Xu and Yeh Citation2010).

Comparing two profoundly different planning systems against the background of globalized knowledge and planning norms poses a methodological challenge. Jenny Robinson described the dilemma of international comparison (of cities) in the following quote:

The demands for comparison are perhaps heightened in an era in which the study of ‘globalisation’ draws more and more urbanists to consider the experiences of cities across the globe, since economic and social activities as well as governance structures in different cities are linked together through spatially extensive flows of various kinds and intense networks of communication. For urban policy, this connectedness has driven an eagerness to learn from experiences around the world with a sometimes frenzied interest in the apparently frictionless circulation of knowledge from city to city through the identification of model cities or best-practice initiatives, for example. But while international urban policy might at times seem prepared to compare almost anything with anywhere in order to apply the best available ideas, scholars in the field of urban studies generally have been extraordinarily reluctant to pursue the potential for comparativism that stands at the heart of the field (Pierre Citation2005). And even where an interest in globalisation draws authors to explicit exercises in comparison, both the methodological resources and the prevalent intellectual and theoretical landscape limit and undermine these initiatives. As a result, promising edited collections, which take care to juxtapose case studies from different parts of the world, still do so without allowing them to engage either with each other or with more general or theoretical understandings of cities. (Robinson Citation2011, 2)

2. Comparative analysis: implications for planning research

There are many motivations for comparing planning systems. Some are more theoretical in nature, while others are based on solving problems of territorial development (Smas and Schmitt Citation2020; Schmidt et al. Citation2021). Comparing planning practices may also be driven by the quest for universal planning theories or the ultimate goal of a typology based on a full inventory of planning systems in a given geographical unit. In particular for the purpose of teaching planning, a comparison may demonstrate what works in a specific context and what remains an appealing but unrealistic idea (Hein Citation2014; Othengrafen and Galland Citation2020). Many studies of OECD countries follow this principle and are usually medium-n studies that implement variation-finding comparisons (Schmidt et al. Citation2021). According to Tilly (Citation1984), variation-finding comparison is a methodology that allows researchers to find gradual variation of patterns within of a group of rather similar systems.

This approach found repercussions in the European debate. Comparative planning studies emerged in Europe as a subdiscipline of planning studies beginning in the 1990s (Nadin and Stead Citation2013; Othengrafen and Galland Citation2020). There are two reasons for this: (1) it is assumed that European states, and EU member states in particular, share some fundamental elements despite all their differences; (2) the European integration process created a framework for policy diffusion and common standards for policymaking. The commonalities of the states in Western Europe can be seen in the post-war economic recovery that was followed by a period of deindustrialization. Most of the planning systems in Western Europe took shape during this period, and in terms of the comparative method, many comparative studies in Europe implicitly refer to these commonalities. These studies are based on matching several variables that are not central to the research (i.e. the evolution of post-war welfare states) and a difference in some key variables explaining the convergence or divergence of planning. However, recent comparative studies have shown that welfare states in Europe can go in very different directions. As the diversity of planning systems increases, so their comparability decreases (Smas and Schmitt Citation2020). In fact, one may ask what states such as Romania, Germany and Estonia share in terms of comparability (not to mention non-EU states such as Serbia, Switzerland and the UK) (Peric and Hoch Citation2017). Geographical proximity and EU membership do not ensure comparability in any case. Other comparisons often focus on a limited number of cases that are considered demonstrative of crucial developments or of massive changes in a specific dimension (such as neoliberalization) in order to explain the variation in outcomes (Roodbol-Mekkes and van den Brink Citation2015). The increasing divergence of planning systems calls for a reinterpretation of the existing European typologies, but also questions the usefulness of typologies as such. Hence, diversity (meaning incomparability) is no longer a privilege of north–south comparisons. Diversity and contrasting contexts call for more interpretative approaches, particularly because comparison in planning studies is seen as context-based.

In a global context, with a high variation of institutional frameworks, political legacies and socio-economic conditions, the limits of variation-finding comparison are even greater. It is not that the three notions of convergence, divergence and persistence do not have their merits in a global context. Many cases may confirm a global trend of change, such as decentralization, informalisation, financialization or privatization, that would also be interpreted in the context of policy diffusion. However, comparing planning in the global North and South requires a methodological solution for comparing systems with fundamental differences in institutional backgrounds, socio-economic conditions and political cultures, at least if the shortcomings of a juxta positioning of a number of cases from different regions of the world is to be avoided (Rubin et al. Citation2020). Despite the widespread application of comparisons using the co-variational template (dependent and independent variables), a global comparison of planning systems may use (a) more qualitative and interpretative approaches and (b) encompassing comparisons. The research project ‘global suburbanisms’ (Keil Citation2017) is a good example in this regard. First, it is an application of a different system design that seeks to describe the global emergence of a phenomenon under a variety of local circumstances (or variables). However, the researchers in this project did not use the explanatory co-variational template, but instead interpreted the phenomenon with all its ramifications. But even the idea of encompassing comparison has its limits as the phenomena of local resistance, idiosyncrasy or appropriation of global planning ideas cannot be operationalized (Robinson Citation2011, 7) (a criticism that the authors also have for world system theory, see McMichael Citation1990). This paper is interested in the ways in which two planning systems from very different contexts have evolved and matured in an emerging global policy context. Against this background, three methodological reflections were made:

The emergence and dissemination of global knowledge on planning theories, planning policies and issues of sustainable urban development and spatial planning can be used as a common reference point for comparison. In the same way, wider supra-national forces might affect planning systems regardless of their degree of difference.

This paper uses field theory to identify system-specific elements that ‘operationalize the same concept in distinct ways in different context’ (Collier Citation1993, 110). Another term for this is ‘functional equivalents’. This paper will do this particularly with regard to planning education (a function that the authors hope to find in every planning system) and the planning organizations (and the relational power) that comprise the field.

Field theory, especially the theory of strategic action fields, allows this study to show that change and stability in the field of planning are the result of relational positions and the relative autonomy of fields.

3. Comparing to understand how global dynamics affect and are affected by the planning field in different national contexts

In terms of categories that guide comparison, existing approaches usually start with institutions. The locus of power in a system and the distribution of competences, functions and veto-options in a multilevel governance framework are referred to as explanatory factors for divergence or convergence (Nadin and Stead Citation2013; Rivolin Citation2008). In addition, many studies have compared the use of instruments and specific planning procedures. Quite often, case studies of planning processes of cities are used as proxies for planning systems. These studies are more qualitative in terms of methodology, usually shedding light on power relations or the relevance of local planning cultures. The planning culture approach goes beyond the systems approach and sheds light on the unspoken cultural premises of spatial planning (Othengrafen and Reimer Citation2013). The methodological stance remains vague, not least because it is difficult to differentiate between a universal planning culture and the specific context of its articulation (Sanyal Citation2016; Zimmermann, Chang, and Putlitz Citation2017). In the following section, the authors demonstrate that field theory is an appropriate perspective for showing that planning cultures are not necessarily homogeneous, but are instead fragmented or even in disagreement. In addition, our interpretation of field theory shows that national planning cultures are not isolated but permeable to international influences.

3.1. Our approach: the theory of fields

Our own approach incorporates the insights of previous studies (not only European) and will also test new ground by using the theory of field theory (Bourdieu Citation2004; Fligstein and McAdam Citation2011). Field theory allows to identify relevant knowledge communities and their relationships within the respective national planning system, as well as an eventual international influence. Field theory also facilitates the consideration of planning education and professional socialization of planners in a community of professionals with shared norms, values and models of what is considered good practice in planning.

3.1.1. What is a field?

The most advanced field theory is certainly that of Bourdieu (Citation2001, Citation2004). According to Bourdieu, fields are a result of social differentiation and the quest for distinction. Each field, such as the scientific field or the field of art, follows its own logic, which has no meaning or relevance in other fields. Standards of appropriate behaviour, evaluation criteria for good practice and knowledge from fields such as the fine arts are more or less worthless in the political or planning fields, for example. Fields have a logic of their own, which is expressed in collective belief systems, symbolic frameworks and related practices that predominate in that field. Still, as a microcosm, societal fields are embedded in a macrocosm. Each microcosm has a different relationship with the imposition of a macrocosm subjected to social laws (Bourdieu Citation2004). This is what Bourdieu called nomos, or what gives a field gradual autonomy and closure in relation to the macrocosm (Bourdieu Citation2001, 41, 353). Not everybody is allowed to enter and become recognized as a member of the field, and career paths and standards of professionalism, education and certification are relevant in this regard (Bourdieu Citation2004). For instance, the political field is characterized by elements such as competition between political parties, the interplay of politics and bureaucracy and typical career paths for politicians and bureaucrats. The standards dominating a field influence the perception of evaluation schemes within it for what is considered good practice.

Other authors see fields as characterized by lasting and, in some cases, formally regulated relationships between organizations (Janning Citation1998; Scott Citation1994). These relationships and the distribution of roles are very complex, but patterns of core–peripheral positioning often emerge. Janning identified the following characteristics of organizational fields (Janning Citation1998, 329; see Scott Citation1994, 216): high interaction density, established patterns of cooperation and domination, increased flow of information, mutual recognition of participating actors, existence of several networks and fractions and recognition of a system of divided or interdependent meaning systems. As will be demonstrated in the next section, the perspective of organizational fields is helpful for comparative analysis of planning systems and cultures.

3.2. The field of planning in theoretical terms

The practice of planning takes place in a highly organized political field equally structured by interests, cultures, regulatory systems, professional values, and knowledge stocks that gain weight against the actors and organizations forming them. As a political field, planning also contains the technical principles, norms, instruments, guiding principles and values of spatial planning, largely defined by laws. Institutionally guaranteed power gives state actors a special position in the planning field. All this is available as collective knowledge and must be learned by new entrants through professional socialization. To understand the dynamics of the planning field, the work of Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011) on the general theory of strategic action fields (SAFs) is useful. The SAF is a meso-level social order with boundaries that are not fixed but constructed situationally. The dynamics of stability and change in SAFs represent greater or fewer power relations in and between the fields. Among others, three sets of characteristics describe the nature of these fields and their relationships with any given SAF: distance and proximity, vertical and horizontal relationships that exist between a specific pair of proximate fields, and state and non-state fields. The interdependence of fields is a source of continuous change in modern societies, caused by exogenous shocks and disruptions. With these conceptual elements, Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011) define the conditions of stability and change in SAFs and distinguish emergent fields, stable fields and fields in crisis (which is particularly relevant for unstable planning systems in the global South). In particular, the SAF approach allows for the identification of periods where statutory planning has lost relevance or has been delegitimized and became a distant, if not non-state field. Economic and political crises or disasters can cause changes or result in the maintenance of the status quo (Pelling and Dill Citation2010). These changes affect the macrocosm (Bourdieu Citation2004), and shifts in planning culture and its system, considered the microcosm, are the consequence of relational stability or fragility. Considering the relative autonomy of the field of planning, climate change, extensive urbanization or the neoliberalism may be considered driving forces that affect the field.

The recognition of planning as an autonomous field, finding acceptance in other societal spheres, as well as the interpretation of what planning entails and how planners should do their job differs considerably between countries. There is a variety of professional conceptions and educational models used in different countries. Still, according to Fürst (Citation2009), the education system is an aspect to be considered in the standardization of practices and stabilization of the field. Fürst (Citation2009) also claims that the internationalization of planning education and the international exchange of ideas within the field play an important role in this standardization process.

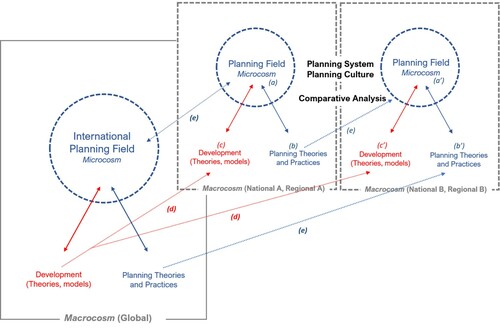

Based on the reflections made in Section 2 and the elements of theory addressed in this section, the figure below schematizes the main aspects and concepts of our approach. The authors view Bourdieu’s microcosm concept (Citation2004) as the planning field (a), or meso-level according to Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011), inserted in a macrocosm as the macro level (being a national or regional level, or supranational or global level) with social laws, rules and norms related to the social development model (c) that affects and is affected by the practices and theories produced by the field (b) .

The field of planning has low autonomy with a low capacity to refract influences from the macrocosm into the field (or microcosm). For this reason, the line (in blue) that defines the field as permeable, the same as the line that defines the macrocosm on a national level, in this case is affected by the global circulation of ideas and other drivers of change. The arrows in blue indicate the relationship between theory and practice. From a global comparative perspective, it is interesting to understand the relationship between the macrocosm and individual fields, and the relationship between international aspects of the field and the global circulation of development theories (d) (e). This comparative framework tries to understand how planning systems and practices emerge and devolve in a horizontal relationship with other contexts and in a vertical relationship with the international field. This discussion covers how specific macro and microcosms have more influence over the production of theories, methods, and techniques.

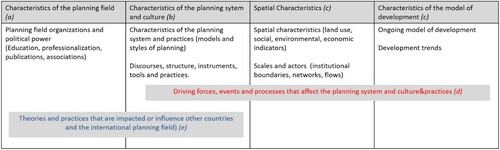

Transforming the scheme into an operational framework, the chart below is the basis for the comparative analysis of the cases. The theoretical-methodological framework is organized into two levels: columns and rows (). The columns address the characteristics of the cases to be compared. Going from the microcosm to the macrocosm, the chart is based on the theories of the social fields (a); the models, styles and practices of planning (b); and spatial characteristics and characteristics of the ongoing and trends of the development model (c). For the first columns associated with the microcosm, this paper uses the categories of SAFs (Fligstein and McAdam Citation2011) associated with the discussion of planning systems, models and practices in each country or region. The right columns are the theories of development (Pieterse Citation2010) and spatial characteristics related to land use, indicators and the institutionalization of scales and actors. The second level of comparison comes from the rows that cross the columns and refer to the influences and forces that affect the cases. From the right side, row (d) comes from the macrocosm, expressing driving forces and events that affect the columns. On the left, this row is related to the international field of planning and endogenous practices and how this affects or is affected by other countries and models (e).

4. Comparing planning systems and practices in Brazil and Germany from a global perspective

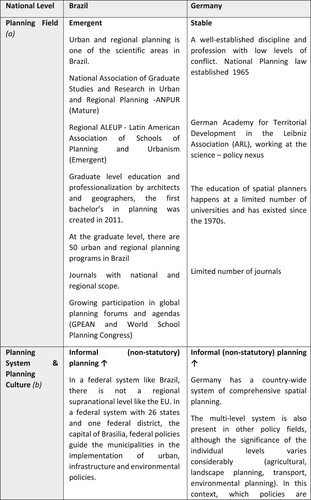

Based on the framework elaborated on in the previous section, the following section presents a comparison of Brazil (4.1) and Germany (4.2). These cases are described separately, and their comparison is presented in Section 4.3.

4.1. Brazil: an emergent field of planning with changes and disruptions

4.1.1. The field of planning in Brazil. Systems and practices, and the development model

The field of planning in Brazil is an ‘emergent field’. This is in line with what Galland and Elinbaum (Citation2018b) concluded about Latin America in the context of a southern turn in planning thought. For Klink et al. (Citation2016), the field of regional planning and urban planning has a strong, but recent, tradition in the Brazilian context, which can be observed in the various newly institutionalized organizations, such as the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Urban and Regional Planning (ANPUR) and the definition of the subarea of ‘Urban and Regional Planning’ within the Programme for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). The planning field in Brazil is characterized by a significant academic output in journals such as RBEUR from the ANPUR (Klink et al. Citation2016), but only with a national reach. In 2016, Brazil hosted the IV World Planning School Congress in Rio de Janeiro and the president (2019–2021) of the Global Planning Education Association Network (GPEAN) was from the ANPUR.

Planning education in Brazil takes place mainly in schools of architecture, urbanism and geography. With the growth of management courses for public policies, territorial planning and environmental management over the recent years, new professional formations have been incorporated into the offer for undergraduates in this area. The graduate level is a distinct field – urban and regional planning – with a clear interdisciplinary and spatial approach. Professionals from the areas of economics, public policies, social sciences and environmental studies also work in the field. Recently, the Council of Architects and Urbanists stipulated that only these professionals are entitled to coordinate urban master plans, causing significant tension within the field (Moura, Follador, and de Freitas-Firkowski Citation2018).

The planning system in Brazil is structured around a federation with 26 states and the Federal District, which guides municipalities and state governments in the implementation of urban, infrastructure and environmental policies. Recently, specific areas such as metropolitan regions and river basins have experienced specific instruments and laws, but with a low degree of institutionalization and implementation. Urban planning, as a subfield, is more important than regional planning and other policy sectors.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, numerous public policies following participative, social justice and sustainability-oriented goals established new values, practices, techniques and instruments regarding planning (Momm-Schult et al. Citation2013). Since the Federal Constitution (FC) of 1988, several approaches and practices of participatory planning have become widespread, as well as terminologies linked to the ideals of sustainability and social justice, but these have not been totally successful (Cabral de Souza, Klink, and Denaldi Citation2020; Momm-Schult et al. Citation2013). During this period, many endogenous practices related to social precariousness and civil insurgence have increased. In terms of field theory, these policies and practices contributed to the increase of the autonomy of the field of planning in Brazil. Still, what is considered to be the accepted and appropriate knowledge in the field of planning is rather based on disparate practices of sustainable and participatory planning in a limited number of city-regions and cities such as São Paulo, Porto Alegre and Belo Horizonte than on nationwide institutionalization.

The obligation to implement master plans in cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants, metropolitan areas and cities with significant tourism or environmental relevance re-emphasized the idea of strategic planning already present in FC-1988 (Fernandes Citation2013). The master plan in Brazil is a statutory instrument that determines how the social functions of properties can be implemented in cities (Fernandes Citation2013). However, according to Randolph (Citation2007), Brazil’s experience with master plans is complex. Brazil has 5,570 municipalities in 26 states. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, only 51.5% of municipalities in 2018 had a master plan and implemented land use management (MUNIC Citation2019). In some bigger cities, master plans were oriented toward strategic planning but influenced by neoliberal ideas. In other cities, the articulation of different interests resulted in a participatory and socially inclusive method (Randolph Citation2007).

Since the FC-1988, there has been a communicative turn in Brazilian planning, but according to Randolph (Citation2007, 4), the real problem is that most of the conceptions and achievements of participatory planning remain attached to the traditional instrumental, technical and sometimes bureaucratic logic of state (public) planning. This does not significantly or more radically redefine the relationship between state and society, and thus contributes to the perpetuation of the status quo (Randolph Citation2007, 4).

4.1.2. Trends and forces that affect Brazil within a global context

In Latin America, there is no supranational level comparable to that of the EU. In recent decades, the Brazilian federal system has provided guiding principles for public policies that were influenced by global platforms and agreements such as the Sustainable Development Goals, the New Urban Agenda and the Paris Climate Change Agreement. Economic and political turbulence led to disruptions in the political viability of these agendas in Brazil, culminating in the election of a federal government with an ultra-liberal agenda and far-right populist orientation in 2018.

With a colonial past with unequal urban and rural land distribution, the contemporary process of space production in Brazil includes extensive and large-scale urbanization under the hegemony of a flexible, post-Keynesian and neoliberal development model. In this context, the role of the metropolitan region as a layer for planning policies is emergent. However, with its low level of institutionalization, Brazil is trying to organize the pattern of extensive urbanization and, on the other hand, is being co-opted by the investment and infrastructure agenda of sector policies, corporations, and municipalities. Without adequate regional equalization schemes and compensatory policies, precariousness and informality exist in addition to capital flows and investments, seeking niches for cheap housing and generating income (Zioni et al. Citation2019).

4.2. Germany: a stable but isolated field of planning

4.2.1. The field of planning in Germany

Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel (Citation2014) conclude in their volume on spatial planning in Europe that, in the past two decades, there has been a common shift towards a more strategic, development-oriented spatial planning in Europe, aimed at a better coordination of land use planning and regional development and sector policies. Furthermore, strategic objectives refer to the incorporation of the principles of sustainability and territorial cohesion, improving the horizontal and vertical coordination of public policies across sectors and jurisdictions. Germany is no exception from this trend, but at the same time its planning system is considered mature, as the integrative and coordinative functions of spatial planning in a multilevel governance system were established in Germany decades ago. The German planning system is usually called a plan-led or plan-conforming system, meaning that statutory spatial plans are the main instrument and point of reference for decisions about land use at all levels (Rivolin Citation2008). The concept of spatial planning in Germany refers to institutionalized planning practices at different levels, including local land use planning, regional planning and state planning (Länder level). Planning at all of these levels shares a common idea of comprehensive and integrated territorial development, largely following the idea of the ordering of land use and coordinating the goals of social, environmental or economic development (Blotevogel, Danielzyk, and Münter Citation2014). The German planning system is surprisingly stable, particularly when compared to neighbouring countries such as the Netherlands or Denmark (Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel Citation2014; Roodbol-Mekkes and van den Brink Citation2015). Change happens, but only in an adaptive and incremental way through new practices or minor adaptations of existing legal frameworks. The planning system in Germany is also quite immune to European and international influences. This stability is at least partly the result of power relations in the German planning field.

In German federalism, the federal government has limited competencies in spatial planning, which is considered the domain of the 16 states or Länder (Fürst Citation2010, 47). Binding spatial plans are made only from the state level downward (Landesplanung). The national planning law sets out the fundamental goals and principles of spatial planning, such as sustainable development and equal living conditions across the country. Within this framework, the 16 states have their own planning laws (Siedentop, Fina, and Krehl Citation2016, 73).Footnote1 The practice and organizational forms of regional planning systems differ between the 16 states. In addition, the aims and principles set in the national law are more qualitative, leaving room for interpretation and evaluation on subnational levels. This planning system was established between the 1960s and early 1970s, and it has not changed in its basic premises since then because the 16 states are strongholds of local interests. The internationalization of planning is of low strategic relevance, and any shifting of planning power towards the EU was viewed with strong scepticism.

4.2.2. Trends and forces that affect German planning within a global and European context

This past decade has demonstrated that this pattern of incremental change has resulted in the creeping loss of relevance of regional planning. Following the rather short period of planning euphoria within the welfare state expansion in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when many states followed extensive planning schemes and established regional planning as a government function, spatial planning was reduced to the core function of regulating land use (Blotevogel Citation2018). A limited revival took place in the 1980s and 1990s due to the emerging paradigms of sustainable regional development (late 1980s) and endogenous regional development (1990s) (Fürst, Nijkamp, and Zimmermann Citation1986). Within these two discursive frameworks, regional planning in particular gained recognition as the appropriate instrument (and level) for implementing the principles of sustainable regional development. In terms of field theory, new coalitions have emerged, including closer cooperation between environmental planning and spatial planning, and the support of environmental associations. However, during the 2000s, statutory spatial planning slowly lost relevance, and the authors see three reasons for this:

Changes in the legal framework more often referred to urban planning and improved local governments’ capacity to act in the realm of urban development. State and regional planning did not keep pace with these improvements.

In addition, sectoral planning (transport infrastructure in particular, but also energy infrastructure) gained importance, limiting the coordinative role of state planning (ARL Citation2011).

Finally, within the system of spatial planning, there was an incremental shift of tasks and power from state planning to regional planning (Blotevogel, Danielzyk, and Münter Citation2014, 27). In some Länder, state planning has been reduced to a minimum number of activities, leaving the bulk of the work to the regions.

The latter development can be seen in the context of austerity and deregulation. However, compared to Brazil, neoliberalization and other global trends have only the most minor impact on German planning.

As a result, the expert planning community (state and regional planning) remained isolated in their field, while urban planning and urban design gained much more recognition. It remains to be seen whether the current discourse on climate adaptation and resilience will open a new window of opportunity for regional planning.

The institutionalization of planning education reflects these developments. Planning education as an academic discipline is well established but still an interdisciplinary endeavour, bringing engineers and urban designers together with social scientists, lawyers, economists and geographers (Kunzmann Citation2015). Spatial planning is an academic discipline of its own with dedicated bachelor’s and master’s programmes offered by a limited number of universities (Kassel, Kaiserslautern, TU Berlin, HafenCity University Hamburg, Cottbus, Dortmund, and a few poly-technique schools). Planning education at these planning schools has different characteristics but shares a common understanding of spatial planning.

In terms of field theory, the German planning field is a fairly stable constellation of cohesive national knowledge communities that share a set of fundamental values and principles of spatial planning. Hence, conflict and competition between antagonistic groups of actors is rather low. It is also highly institutionalized, and there is a considerably high standard of professional socialization. However, there is a slow ongoing process of disintegration separating regional planning and urban planning into two distinct knowledge communities. What used to be proximate fields are on their way to becoming distant fields. Spatial planning in the defined normative sense of integrated and comprehensive territorial development finds less support in politics at different state levels. State and regional planning were much more en vogue in the 1970s and 1980s. This explains the incremental rate of change and low performance in the reduction of land consumption. The weak relationship between the planning field and the political field is one of ambivalence as it can be interpreted as lack of interest and a guarantee of stability at the same time. It is unlikely that a future government will fundamentally change the planning system (as has happened in the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark) because state and regional planning are not seen as a public policy of high political relevance.

4.3. Comparison of emerging and a mature fields of planning

Our study compares an emerging and a mature field of planning from two different political and economic contexts. Closer scrutiny shows that both planning systems experienced an increase in sectoral initiatives and sectoral planning, weakening the political relevance of integrated regional planning. Seeing these changes in the planning system through the lens of field theory demonstrates that the field of planning is less autonomous and institutionalized in Brazil than in Germany, although a certain degree of isolation is observable in both systems (though for different reasons: political instability in the case of Brazil, inability to follow the co-evolution of fields in Germany). The degree of institutionalization is higher in Germany in conjunction with the decentralized and federal character of the system, which gives it greater stability (as changes require the consent of the 16 states). However, this slows down the system’s capacity to adapt to societal changes and global influences. Many sectoral policies such as transport and environmental planning are more effective in this regard. This contrasts with Brazil, where a national law can prescribe the elaboration of master plans with defined standards for participation. The initiative for change usually comes from the outside, as the planning field does not generate enough support for deeper changes and is reactive. As a mature and closed field, Germany reveals only a limited degree of international orientation, but Europeanisation is still relevant due to regulatory frameworks for environmental planning and regional cohesion policies.

Global driving forces and platforms have been influential in the field of planning and have modified its characteristics, as was formulated as a hypothesis in our framework. Global challenges demand new ideas in planning, but these are articulated differently through field-specific norms (a market-led response in Brazil vs. prevailing norms of territorial welfare policies in Germany; openness to informal planning in both systems).

In the German case, a solid multilevel federative system and the presence of EU programmes in the field of territorial development ensure a balance between these forces and national public and collective interests. In the Brazilian case, despite its path toward maturation, current ruptures in the political field have had an immediate impact on the planning system and planning culture, and changes in normative frameworks and federal public policies have been frequent. One example from the state level is the extinction of institutions as EMPLASA – Sao Paulós State Planning Company – so that reducing the capacity of comprehensive long-term regional planning continues.

Regarding the production of field-specific knowledge, Brazil and Germany have very different positions though facing similar challenges. As a wealthy country in the European Union, Germany has a consistent position, but low visibility or influence in the international field of planning, as can be seen in the difference between the number of documents and citations identified in the literature review (see Appendix). Brazil, in a geographically opposite situation in Latin America, faces challenges in asserting itself as an agent in the international field, in the production of theories and practices of planning. As in Germany, the point is not that these theories and practices are undeveloped, but probably because of the language, they suffer from endogeneity. In the German case, this refers to the tradition of state-led comprehensive planning in a federal system, and in the Brazilian case, to several experiences over the last decades with participatory planning and informality. After hosting the Rio 1992 Conference on sustainable development and witnessing the blossoming of a civil society, Brazil now faces a federal government (2019–2022) that has threatened to break with agreements and trajectories in the environmental arena.

The institutionalization of planning education in the two states illustrates the differences with regard to the influence of globalized planning ideas and norms. While the high level of professional socialization in the German planning field displays a certain degree of closure and an inward orientation, planning education in Brazil is still maturing and more open for external influences.

As shown in , globalized drivers, such as extensive urbanization and climate change, affect planning in several different countries and regions. However, the responses to planning in terms of theories, practices and planning systems are different, as the position of each country in the geopolitics of global knowledge production is different. For example, the debate on postcolonialism and decolonialism shows how practices and theories circulate differently around the globe. The chart below summarizes this paper’s arguments using the elements defined in the author’s framework ().

5. Final considerations

Regarding the grounded theory of this paper’s analysis, it is important to note that the theory of Strategic Action Fields (SAF) by Fligstein and McAdam represents a possibility of analysis going beyond Bourdieu’s approach, because it incorporates the dynamics and interrelationship between the fields. Regarding the concept of planning culture, field theory, particularly SAF, demonstrates how power relations in and between fields affects planning practice. The fields’ characteristics and their relationships with others (e.g. distant and proximate fields, vertical and horizontal relationships that exist between a specific pair of proximate fields, and state and non-state fields) are very useful for understanding the relationships between planning and other disciplines, such as architecture and geography. The interdependence of fields and the low autonomy of the planning field are sources of ongoing disorder modern societies caused by exogenous shocks and disruptions.

Chart 2. Comparative analysis of Brazil and Germany (letters in the first column refer to the framework in and ).

The application of field theory demonstrated that the comparison of planning cultures and planning systems does not necessarily need to tap into the trap of national containers or homogenous national planning cultures. The relational perspective and configurational analysis show that national planning systems and cultures are composed of fields and subfields, that are partly antagonistic, partly in a state of equilibrium, partly proximate or distant. The relation between the field of planning and the field of politics seems to be of utmost importance. Also, the differentiation of the field of planning into competing subfields (regional planning, urban planning, urban design, infrastructure planning) has explanatory power for what is happening in Germany and Brazil. The relational analysis also shows how external references to the globalized (but selective) circulation of planning ideas and norms are built and used (Brazil) or ignored (Germany). Again, the theory of strategic action fields will allow to show that only some groups or professional planning communities refer to globalized planning ideas. In any case, the relational configuration of fields and subfields as a framework for the comparative study of planning in a global context seems to be a viable perspective. A comparison of fields rather than institutions, practices or cases demonstrates that a focus on the relationships and autonomy of fields can explain the openness, maturity, closure and change of national planning systems and cultures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Bavaria opted to leave this system in 2006 and has a state planning law that substitutes the national one.

2 We used the Scopus index keywords: comparative study; planning system; planning culture; planning practice.

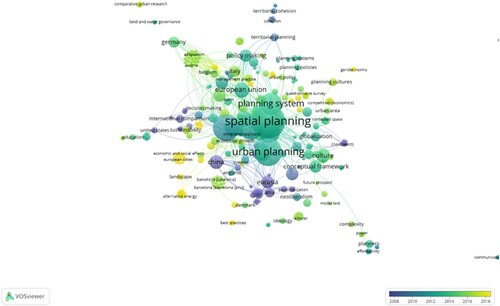

3 For the quantitative analysis the software Vosviewer was used. http://www.vosviewer.com/.

References

- ARL (Academy for Spatial Research and Planning). 2011. Strategic Regional Planning (Position Paper No. 84). Hannover: ARL.

- Binder, G., and J. M. Boldero. 2012. “Planning for Change: The Roles of Habitual Practice and Habitus in Planning Practice.” Urban Policy and Research 30 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1080/08111146.2012.672059.

- Blotevogel, H. H. 2018. Geschichte der Raumordnung, In Handwörterbuch der Stadt- und Raumentwicklung, edited by ARL, 793–803. Hannover: ARL.

- Blotevogel, H. H., R. Danielzyk, and A. Münter. 2014. “Spatial Planning in Germany. Institutional Inertia and New Challenges.” In Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes, edited by M. Reimer, P. Getimis, and H. Blotevogel, 83–107. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 2001. Science de la science et reflexivité. Paris: Raisons d´Agir.

- Bourdieu, P. 2004. Os usos sociais da ciência: por uma sociologia clínica do campo científico. São Paulo: Ed. UNESP.

- Cabral de Souza, C., J. Klink, and R. Denaldi. 2020. “Planificación reformista-progresista, instrumentos urbanísticos y la (re)producción del espacio en tiempos de neoliberalización. Una exploración a partir del caso de São Bernardo do Campo (São Paulo).” Revista De Estudios Urbano Regionales 46 (137): 199–219.

- CEC (Commission of the European Communities). 1997. The EU Compendium of Spatial Planning Systems and Policies. Luxembourg: Commission of the European Communities.

- Collier, D. 1993. “The Comparative Method.” In Political Science: The State of the Discipline II, edited by Ada W. Finifter, 105–119. Washington, DC: APSA.

- Fernandes, A. 2013. “Tendências e desafios no fomento à pesquisa na área de Planejamento Urbano e Regional: uma análise a partir do CNPq (2000–2012).” Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais 15 (1): 59–76. doi:10.22296/2317-1529.2013v15n1p59.

- Fligstein, N., and D. McAdam. 2011. “Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields.” Sociological Theory 29 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01385.x.

- Fürst, D. 2009. “Planning Cultures en Route to a Better Comprehension of ‘Planning Processes’?” In Planning Cultures in Europe. Decoding Cultural Phenomena in Urban and Regional Planning, edited by J. Knieling and F. Othengrafen, 23–38. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Fürst, D. 2010. Raumplanung: Herausforderungen des deutschen Institutionensystems. Detmold: Rohn.

- Fürst, D., P. Nijkamp, and K. Zimmermann. 1986. Umwelt-Raum-Politik: Ansätze zu einer Integration von Umweltschutz, Raumplanung und regionaler Entwicklungspolitik. Berlin: Edition Sigma.

- Galland, D., and P. Elinbaum. 2018a. “A “Field” Under Construction: The State of Planning in Latin America and the Southern Turn in Planning.” DISP – The Planning Review 54 (1): 18–24. doi:10.1080/02513625.2018.1454665.

- Galland, D., and P. Elinbaum. 2018b. “Positioning Latin America Within the Southern Turn in Planning: Perspectives on an “Emerging Field”.” DisP – The Planning Review 54 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1080/02513625.2018.1454696.

- Hein, C. 2014. “The Exchange of Planning Ideas from Europe to the USA after the Second World War: Introductory Thoughts and a Call for Further Research.” Planning Perspectives 29 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1080/02665433.2014.886522.

- Janning, F. 1998. Das politische Organisationsfeld. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Keil, R. 2017. Suburban Planet: Making the World Urban from the Outside In. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Klink, J. J., S. Momm, S. Zioni, A. Favareto, and M. Mencio. 2016. “O Campo e a Práxis Transformadora Do Planejamento: Reflexões Para Uma Agenda Brasileira.” Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais 18 (3): 381. doi:10.22296/2317-1529.2016v18n3p381.

- Kunzmann, K. R. 2015. Germany. DisP - The Planning Review 51 (1): 38–39. doi:10.1080/02513625.2015.1038055.

- McFarlane, C., and J. Robinson. 2012. “Introduction—Experiments in Comparative Urbanism.” Urban Geography 33 (6): 765–773.

- McMichael, P. 1990. “Incorporating Comparison Within a World-Historical Perspective: An Alternative Comparative Method.” American Sociological Review 55 (3): 385–397.

- Momm-Schult, S. I., J. Piper, R. Denaldi, S. R. Freitas, M. L. P. Fonseca, and V. E. Oliveira. 2013. “Integration of Urban and Environmental Policies in the Metropolitan Area of São Paulo and in Greater London: The Value of Establishing and Protecting Green Open Spaces.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 5: 89–104.

- Moura, R., D. Follador, and O. L. C. de Freitas-Firkowski. 2018. “Brazil.” DisP – The Planning Review 54 (1): 28–30. doi:10.1080/02513625.2018.1454671.

- MUNIC. 2019. Perfil dos municípios brasileiros: 2018, Coordenação de População e Indicadores Sociais. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE.

- Nadin, V., Fernández Maldonado, A. M., Zonneveld, W., Stead, D., Dąbrowski, M., Piskorek, K., Sarkar, A., Schmitt, P., Smas, L., Cotella, G., Janin Rivolin, U., Solly, A., Berisha, E., Pede, E., Seardo, B. M., Komornicki, T., Goch, K., Bednarek-Szczepańska, M., Degórska, B., … Münter, A. 2018. COMPASS - Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Applied Research 2016- 2018: Final Report. ESPON and TU Delft. Luxembourg.

- Nadin, V., and D. Stead. 2013. “Opening up the Compendium: An Evaluation of International Comparative Planning Research Methodologies.” European Planning Studies 21 (10): 1542–1561. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722958.

- Othengrafen, F., and D. Galland. 2020. “International Comparative Planning.” In The Routledge Handbook of International Planning Education, edited by Leigh G. Nancey, Steven P. French, S. Guhathakurta, and B. Stiftel, 217–226. London: Routledge.

- Othengrafen, F., and M. Reimer. 2013. “The Embeddedness of Planning in Cultural Contexts: Theoretical Foundations for the Analysis of Dynamic Planning Cultures.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (6): 1269–1284.

- Pelling, M., and K. Dill. 2010. “Disaster Politics: Tipping Points for Change in the Adaptation of Sociopolitical Regimes.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (1): 21–37.

- Peric, A., and C. Hoch. 2017. “Spatial Planning Across European Planning Systems and Social Models: A Look Through the Lens of Planning Cultures of Switzerland, Greece and Serbia.” In E-Proceedings of the AESOP 2017 Conference “Spaces of Dialog for Places of Dignity: Fostering the European Dimension of Planning”, edited by José Antunes Ferreira, et al., 1247–1258. Lisbon: University of Lisbon.

- Pierre, J. 2005. “Comparative Urban Governance: Uncovering Complex Causalities.” Urban Affairs Review 40 (4): 446–462.

- Pieterse, J. N. 2010. Development Theory. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Randolph, R. 2007. “Do planejamento colaborativo ao planejamento “subversivo”: reflexões sobre limitações e potencialidades de Planos Diretores no Brasil.” Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales XI (17): 245. http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-24517.htm.

- Reimer, M., P. Getimis, and H. Blotevogel. 2014. Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes. London: Routledge.

- Rivolin, U. J. 2008. “Conforming and Performing Planning Systems in Europe: An Unbearable Cohabitation, Planning.” Practice & Research 23 (2): 167–186. doi:10.1080/02697450802327081.

- Robinson, J. 2011. “Cities in a World of Cities: The Comparative Gesture.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (1): 1–23.

- Robinson, J. 2016. “Comparative Urbanism: New Geographies and Cultures of Theorizing the Urban.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (1): 187–199.

- Roodbol-Mekkes, P. H., and A. van den Brink. 2015. “Rescaling Spatial Planning: Spatial Planning Reforms in Denmark, England, and the Netherlands.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (1): 184–198. doi:10.1068/c12134.

- Rubin, M., A. Todes, P. Harrison, and A. Appelbaum, eds. 2020. Densifying the City? Global Cases and Johannesburg. Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar.

- Sanyal, B. 2016. “Revisiting Comparative Planning Cultures: Is Culture a Reactionary Rhetoric?” Planning Theory & Practice 17 (4): 658–662. doi:10.1080/14649357.2016.1230363.

- Schmidt, S., W. Li, J. Carruthers, and S. Siedentop. 2021. “Planning Institutions and Urban Spatial Patterns: Evidence from a Cross-National Analysis.” Journal of Planning Education and Research. doi:10.1177/0739456X211044203.

- Scott, R. W. 1994. “Conceptualizing Organizational Fields.” In Systemrationalität und Partialinteresse, edited by H. U. Derlien, U. Gerhardt, and F. W. Scharpf, 203–221. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Siedentop, S., S. Fina, and A. Krehl. 2016. “Greenbelts in Germany’s Regional Plans—An Effective Growth Management Policy?” Landscape and Urban Planning 145: 71–82.

- Smas, L., and P. Schmitt. 2020. “Positioning Regional Planning Across Europe.” Regional Studies. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1782879.

- Tilly, C. 1984. Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Watson, V. 2016. “Shifting Approaches to Planning Theory: Global North and South.” Urban Planning 1 (4): 32–41. doi:10.17645/up.v1i4.727.

- Xu, J., and A. G. O. Yeh. 2010. Governance and Planning of Mega-City Regions: An International Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Zimmermann, K., R. Chang, and A. Putlitz. 2017. “Planning Culture: Research Heuristics and Explanatory Value.” In Planning Knowledge and Research, edited by Thomas W. Sanchez, 35–50. London: Routledge.

- Zioni, S., L. Travassos, S. Momm, and A. Leonel. 2019. “A Macrometrópole Paulista e os desafios para o planejamento e gestão territorial.” In Adaptação às Mudanças Climáticas na Macrometrópole Paulista – diálogos entre a ciência e a política, edited by P. Jacobi, et al., 90–100. São Paulo: Annablume.

Appendix

Comparative planning studies: what is the state of the art?

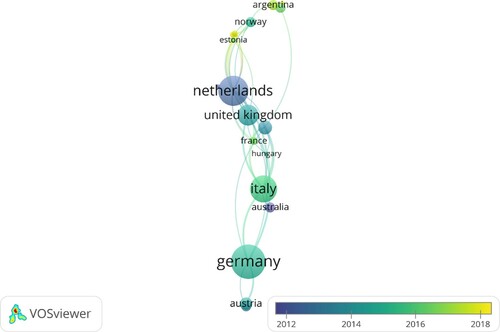

Global comparisons of planning systems are rare and a majority of publications is more of an encyclopedia type rather than a contribution to a comparative methodology (see discussion in: McFarlane and Robinson Citation2012). Considering that the subject under discussion here is recent and without clearly defined theoretical lines or academic traditions, the bibliographic research method seems to be most appropriate for the review of the literature. It was done based on keywords in articles reviewed by pairsFootnote2 and followed by the Snowball Method Citation Network Analysis. This combination allows the assessment of the recent publications, with main authors, subjects and places of research in a time span from 1999 to 2019. This period covered what Nadin and Stead (Citation2013) define as the period of increase of comparative studies in planning – at least in Europe.

The first search based on keywords resulted in 55 papers from which 16 were selected based on their affinity with the proposed subject. The next step – the snowball with documents cited by 16 articles – resulted in 149 documents including journal articles, books, chapters, conference papers, editorials and reviews from which 65 papers and 12 books or chapters were selected. The final total number of documents was 93.

For quantitative analysesFootnote3 regarding the countries of the authors and coauthors, it is possible to identify the dominance of Germany, Netherlands, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Regarding the period of the publications, 76% of them were from 2010. It demonstrates the rise of interest and an expansion of comparative planning studies in other continents beyond Europe and the ‘resurgence’ of international comparative studies (Nadin and Stead Citation2013) (see Figure A2). In Latin America and Brazil, however, this is a recent development.

The analysis of the keywords of the documents selected shows the dominance of planning system studies. Heuristic such as planning culture and practices are a more recent phenomenon and more dispersed. The scales and subjects referred to more often are: the European Union, spatial planning and urban planning, and as a more recent trend, climate change and adaptation.

Among the current studies we want to highlight a special issue edited by Galland and Elinbaum (Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The special issue covers seven Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay). Hence, it is one of the few comprehensive comparative analysis and synthesis based on a survey among experts in each country. The survey included topics such as the present status of planning in politics and the society; links between planning theory and practice; social, economic and spatial differences; planning education and planning knowledge exchange. One important conclusion is that planning in Latin America is an emerging field within the Southern turn in planning.

The existing work in Europe, in contrast, follows the tradition of comparative studies in Europe and includes a critical discussion about the past studies (i.e. the four families of planning systems) (Nadin et al. Citation2018; Nadin and Stead Citation2013; Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel Citation2014). The works present and represent a diversity of methodologies and theoretical references for comparatives studies in the contemporary period. This research is concentrated in Europe, as the quantitative results of the state the art have shown, but it is expanding its scope, considering more aspects on different levels and scales.