Abstract

In this article, I seek to demonstrate how the 1986 massacre of nearly 250 inmates at El Frontón and Lurigancho prisons can shed light on the political and social exclusion faced by Shining Path militants, during and since Peru’s internal armed conflict (1980–2000). I will analyse how Peruvian prisons have been historically used as sites of exclusion for political opponents of the Peruvian state. Then, through an analysis of literary responses to the massacres and the wider conflict, I will demonstrate how cultural producers have sought to recover Shining Path memories of violence, in order to highlight both the persistent socioeconomic conditions that precipitated Shining Path’s insurrection and the continuing impunity for perpetrators of state violence. Finally, I will show that the recuperation of Shining Path memories in literary sources is undermined by the continuing silence of El Frontón in Lima’s memoryscape, and say what this tells us about the limits of acceptable memory discourse in present day Peru.

Introduction

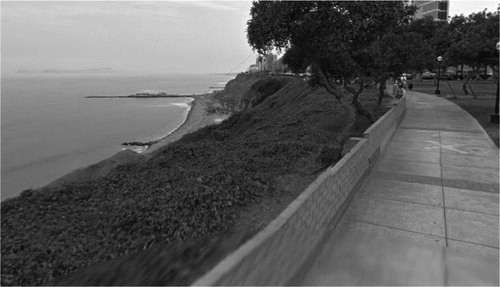

In June 1986, after several days of rioting in three penitentiaries across Lima, the Peruvian armed forces attempted to quash the unrest by bombarding the state’s own prison fortress on the island of El Frontón. One hundred and eighteen inmates, most of them accused of belonging to the insurgent group Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), died at the San Juan Bautista de la Isla (El Frontón) prison, in addition to the One hundred and twenty-four who had died at the San Pedro (Lurigancho) prison the day before. These prison massacres represented the failure of President Alan García’s ostensible attempts to conduct a more humane counterinsurgency operation against the threat posed to the Peruvian state by Shining Path, and to a lesser extent the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (MRTA). The prison’s ruins, located just a short distance from Lima’s coastline, are therefore an important symbol of the counterinsurgent violence perpetrated by the Peruvian state, acting as a physical testament to the internal armed conflict which claimed the lives of almost 70,000 Peruvians between 1980 and 2000 (Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación [CVR] Citation2003, VIII, 315). Thus, Peru’s recent history has come to be inscribed into the landscape and El Frontón remains, in the words of Peruvian artist Gustavo Buntinx, “a liminal space where geography and history intermingle” (Buntinx Citation2014, 44).

Figure 1. The island of El Frontón. Photograph by Gladys Alvarado Jourde (Buntinx Citation2014, 73) © Gladys Alvaro Jourde.

Yet whilst the former prison island () stands as a physical reminder of the violent erasure of Shining Path militants (or Senderistas), cultural producers are increasingly exploring El Frontón as a cultural space in which Senderista memories of the internal armed conflict can be reclaimed. Whilst these works reject the “heroic” narrative of the massacres espoused by Shining Path leaders such as Abimael Guzmán, in which the massacres are remembered as a necessary sacrifice in Sendero’s guerra popular, they can be seen to reclaim Senderista narratives by focusing on the political motivations and marginalised social positions of rank-and-file Shining Path militants. For example, José Carlos Agüero (Citation2015b) has attempted to recuperate Senderista memories by humanising the inmates who died during the suppression of the riots, representing them not solely as perpetrators of violence, but also as victims. “Flood”, a short story by Daniel Alarcón (Citation2006), highlights the marginalised social position of prisoners at Lurigancho prison, whilst Hunt (Citation2017) has argued that Peruvian prisons are an important literary site for the reclamation of Senderista citizenship in her analysis of Santiago Roncagliolo’s novel Abril rojo.1 In a similar manner, Gladys Alvarado Jourde’s photographs (Buntinx Citation2014; Vich Citation2015, 79–94) of the now abandoned island depict the prison ruins, acting as a form of testimony to the lives of Shining Path prisoners who were detained there, as well as to the Peruvian state’s destruction of its own fortress and citizens. Here (), a large hammer and sickle can be seen inscribed upon a stone wall, framed by the sky and rubble. The symbol has been deliberately erased, seemingly scratched out in order to remove evidence of Shining Path’s presence on El Frontón in a symbolic recreation of the massacre. Ironically, however, whoever was tasked with erasing the hammer and sickle has only endeavoured to scratch out the paint, with the effect that the shape of the symbol can still be seen in a blurred grey form. This photograph stands in for the experience of the massacres as a whole, in which by trying to erase Shining Path, the state has only managed to inscribe them further into history (Vich Citation2015, 91). By photographing the island and documenting the stories of those who died there, these cultural producers are reversing the symbolic erasure of Senderistas from current memory discourse in Peru. In this sense, both these recent cultural works and the prison’s physical ruins can be seen as “lieux de mémoire” (Nora Citation1989), repositories for memories of the massacres and of the wider conflict.

Figure 2. A hammer and sickle inscribed into a wall on El Frontón, which has later been erased. Photograph by Gladys Alvarado Jourde (Buntinx Citation2014, 35) © Gladys Alvaro Jourde.

Shining Path memories remain a controversial subject largely due to the group’s actions from 1983 onwards, which became, Kimberly Theidon argues, “increasingly authoritarian and lethally violent, unmatched by any other armed Leftist group in Latin America” (Citation2012, 324). Furthermore, as José Rénique (Citation2003) argues, the group’s use of prison space for political ends and the belief, of their leaders at least, that the suffering and sacrifice of militants would further their anti-imperialist cause, has given Shining Path a reputation for brutality that many find it difficult to sympathise with. As a result, many commemorations and scholarly works on the conflict produced by Peru’s community of “memory activists” (Willis Citation2018, 35) which are even mildly sympathetic to Shining Path militants have been denounced as apología del terrorismo.2 This is demonstrated by the polemical reactions from Peruvian politicians and journalists to recent controversies surrounding the inclusion of victims of the 1992 Castro Castro prison massacre in the El ojo que llora memorial (Drinot Citation2009), the opening of an exhibition of artistic works produced by prison inmates (La República Citation2014), and the creation of a mausoleum for Senderistas who died during the 1986 prison massacres (BBC Mundo Citation2016).

Cultural producers who seek to recuperate memories of the prison massacres therefore do so in a cultural environment which is highly critical, and at times censorious, of Shining Path perspectives on the internal conflict, suggesting that the victims of the massacres are considered “ungrievable” (Butler Citation2009, 24). In order to understand why this is the case, I will firstly set out below how Peruvian prisons have facilitated the violent exclusion of politically and socially marginalised groups. I will then explore how cultural producers have begun to reverse this exclusion by seeking to better understand Shining Path militants, reconstituting Senderistas as grievable lives in the process. Finally, I will demonstrate that the recuperation of Senderista perspectives in these works stands in contrast to the broader lack of engagement with, and censorship of, the memories of those who perished on El Frontón in public space.

“Bare life” and ungrievable populations

Attempts to exclude Senderista memories from commemorative practice can be seen as a continuation of the demonisation of Shining Path members during the conflict, particularly in official narratives, which almost exclusively described the group as terrorists or terrucos. As Aguirre (Citation2011) and Burt (Citation2006) have argued previously, the categories of “terrorist” and “terruco” were deeply racialised, and Shining Path militants were usually “seen as indigenous (...) and, thus, dangerous, deceitful, and undeserving” (Aguirre Citation2013, 203). This raises the question as to whether the exclusion of Senderista memories can simply be attributed to Shining Path’s position as major perpetrators of violence, or whether anti-Senderista interventions are more deeply motivated by the same fears of social upheaval and the racialised Other which underpinned state violence during the conflict.

To understand how these fears are deployed to justify state violence, it is important to consider the work of Giorgio Agamben and Judith Butler on “bare life” and grievability.3 Aguirre has argued that, between 1850 and 1930, approaches to incarceration were shaped by a desire to punish rather than to reform, “if not always in the official discourse, certainly in the perception and behaviour of prison experts” (Aguirre Citation2005, 85). The evidence from the CVR suggests that these attitudes largely prevailed in the 1980s, as long before the 1986 riots there were severe failures in the infrastructure of prison space and provision of food to inmates. According to the CVR (Citation2003, VII, 738), these conditions amounted to “the absence of the minimum conditions of life” in Peruvian state prisons. Prisoners lived in a state which Agamben refers to as “bare life”, a condition in which inmates were beyond the protection of the law and denied basic rights (e.g. sustenance, hygiene, due process) in order to be punished rather than rehabilitated (Agamben Citation1995, 7). The reduction of Senderistas to “bare life” can be seen as the exercise of violent state power over political opponents. As has been argued previously, there are parallels between the violent exercise of power on Senderista bodies in prisons and the disciplinary and exclusionary functions of state violence conducted against Leftist groups and indigenous communities during the state’s counterinsurgency operation (Willis Citation2018, 237–47). Both forms of violence reflect the exercise of necropolitics; in the words of Mbembe, the power to “dictate who may live and who must die” (Mbembe Citation2003, 11). In this sense, “bare life” is not just the condition of detainment, but a position of political and social exclusion. The reduction of Senderista militants to “bare life” acted as a means of excluding undesirable elements from society, disciplining communities, and sustaining class and racial hierarchies.

This exclusion has deeply influenced how the conflict has been remembered. Butler argues that “why and when we feel politically consequential affective dispositions such as horror, guilt, righteous sadism, loss, and indifference” is contingent upon the individuals or populations whom violence has been inflicted upon (Citation2009, 24). She goes on to argue that “forms of racism (…) tend to produce iconic versions of populations who are eminently grievable, and others whose loss is no loss, and who remain ungrievable” (Butler Citation2009, 24). In the context of the Peruvian conflict, this suggests that the exercise of state violence against Senderistas and indigenous communities is accepted because they are ungrievable, and that subsequently these victims of violence will not be remembered or grieved. This was particularly the case before the publication of the CVR’s Informe final, which found that “the tragedy suffered by the populations of rural Peru, the Andean and jungle regions (...) was neither felt nor taken on as its own by the rest of the country” (CVR Citation2003, VIII, 316). Since the publication of the Informe final, the victimisation of peasant communities at the hands of state agents has been strongly reconsidered in Peruvian literature and cinema to such an extent that some communities may now be considered eminently grievable.4 As I demonstrate below, there is increasing attention being paid to the grievability of Senderista militants and victims of the 1986 massacres in Peruvian culture, but this has met with a wave of opposition and repression which reflects earlier attempts to exclude, discipline, and punish political opponents of the Peruvian state.

Understanding Shining Path through the current literature

After initial studies by North American scholars such as Cynthia McClintock (Citation1984) and David Scott Palmer (Citation1986) interpreted the conflict as a peasant-led rebellion in the context of subsistence crises in Ayacucho, a second historiographical phase, heavily influenced by the work of Carlos Iván Degregori (Citation2012, 159–71), emphasised the role of Shining Path’s “all-powerful” Maoist ideology as a primary explanatory factor for its “astonishing violence”. The CVR’s final report on the conflict revealed almost three times the number of victims than had previously been assumed (CVR Citation2003, VIII, 315) and was heavily critical of the role played by Shining Path and state agents in militarising the conflict (317). This view of Shining Path represents a marked difference with instances of Leftist insurgency and state counterinsurgency in the Southern Cone, where Leftist groups tend to be referred to as victims of state terrorism (Fried Amilivia Citation2016).

In recent years, however, scholars have increasingly paid greater attention to the remaining silences and hidden stories in the literature on the internal armed conflict. Scholars such as Jaymie Heilman (Citation2010), Miguel de La Serna (Citation2012), and Ponciano Del Pino (Citation2017) have contested the CVR’s representation of Shining Path by arguing that they were a syncretic movement, inspired equally by Maoist ideology and the local socioeconomic conditions of the south-central Andes. Furthermore, Olga González (Citation2011), Américo David Meza Salcedo (Citation2014), Leslie Villapolo Herrera (Citation2003), Theidon (Citation2012), and Del Pino (2017) have demonstrated how peasant and Asháninka communities have regularly concealed their own violent response to Shining Path, or have gone about “erasing their sympathies with and participation in Shining Path” (Theidon Citation2012, 322) in order to repress these “taboo” memories and protect themselves from retribution. Taken together, these works suggest a far broader popular participation in Shining Path than had been acknowledged previously, and highlight the multiple forms of violence enacted against, as well as by, Shining Path militants.

The 1986 massacres themselves have also come under greater attention. Whilst early responses (Ames et al. Citation1988; Haya de la Torre Citation1987) criticised the state’s response, more recent analyses have examined “heroic” Senderista narratives of the massacres (Rénique Citation2003), how these memories are claimed and contested by different Leftist groups (Feinstein Citation2014), and how the political and ethnic identities of Senderista militants made them targets for “punishment and extermination” (Aguirre Citation2013). It is important to question, therefore, whether violence perpetrated against Shining Path militants has largely been occluded from memory narratives of the conflict because of their political and ethnic identities. As Feinstein’s research (Citation2014) highlights, Shining Path militants have accused human rights advocates of co-opting and sanitising memories of the massacres without recognising the inherently political identities of the victims (suggesting that the victims can be commemorated, as long as they are not associated with Sendero). By contrast, Milton (Citation2018) has demonstrated how the Peruvian armed forces have cultivated a narrative about the actions of so-called buenos militares during the conflict. This narrative gives additional weight to the ethical complexities of the counterinsurgency operation faced by soldiers and dismisses human rights violations as the work of a few bad apples. The result is that state actors appear individualised as both victims and perpetrators of the conflict and the institutional racism and violence of the military are largely downplayed. The buenos militares narrative fashions a discursive space through which military memories have been rehabilitated and have become part of acceptable memory discourse in Peru in a way that Senderista memories have not. This is despite the knowledge that state agents were also major perpetrators of violence. The ongoing memory battles in Peru today therefore reflect not only competing versions of the past and claims to truth, but also a contest between political actors to define the limits of mainstream political discourse and how different forms of violence are remembered.

Despite the atrocities committed by Shining Path militants, it is important for the 1986 massacres to be fully understood in the context of the conflict. The death of nearly 250 inmates in 1986 is a reminder of the state violence perpetrated not only during the counterinsurgency operation, but also against Leftist militants in the 1960s, Apristas in the 1930s, and other members of non-violent Leftist groups throughout Peruvian history. These stories are crucial for understanding why the Peruvian state’s counterinsurgency operation was not simply a military conflict against an armed opponent, but an example of widespread state violence (with historical precedents) conducted against “political and biopolitical enemies” (Drinot Citation2011, 187).

As well as their implications for understanding Peru’s past, the prison massacres are important to Peru’s present. As Theidon has argued, accusations of apología del terrorismo are used “to delegitimize opposition and civil society groups that voice their demands for change” (Citation2012, 325). In other words, it is particularly important for scholars to address why so many militants took to arms, and analyse the violence deployed against them, whilst many of the socioeconomic conditions which precipitated the conflict exist. Only by bringing into scholarly literature the experiences of Shining Path militants and the practices commemorating the conflict can we understand the role played by the Peruvian state in sustaining racialised hierarchies and limiting political change.

The 1986 prison massacres in context

The massacres at El Frontón and Lurigancho were perpetrated at a time when the internal conflict was becoming increasingly brutal and militarised. After Shining Path achieved some initial success in gaining peasant support and establishing control over areas of northern Ayacucho, Apurímac, and Huancavelica, the Peruvian state’s counterinsurgency operation began in earnest in 1983 with the establishment of military bases across the sierra. As the conflict moved north into the selva central and intensified in Lima in the mid to late 1980s, Shining Path conducted high-profile bombings and assassinations of military figures, civil society leaders, and trade unionists in the capital, whilst enslaving Asháninka communities in jungle regions and perpetrating reprisals against peasant communities in the Andes. The CVR’s Informe Final (Citation2003, VIII, 317) estimates that, of the conflict’s 70,000 victims, Shining Path were responsible for 54% of the deaths. Nonetheless, the CVR was also heavily critical of the role of state forces in militarising the conflict, conducting extrajudicial executions in a systematic manner, and perpetrating numerous atrocities against indigenous communities.

Due to poor prison infrastructure (and a series of high-profile breakouts) in Ayacucho, the Peruvian state began transferring accused Senderistas to prisons in Lima from 1983. As Aguirre has argued, Peruvian prisons have a history of “poorly paid guards and employees, corrupted authorities, and a general state of abandonment” which grew worse as the conflict intensified throughout the 1980s (Aguirre Citation2013, 199). Despite being in a state of disrepair, El Frontón was reopened and hundreds of accused insurgents were detained in dreadful conditions (often without charge or evidence). This decision backfired, however, as Shining Path took control of their prison wards, recruited inmates, and held political education lessons.

This was not the first time that El Frontón had been used to detain political prisoners. As Aguirre (Citation2014, 12) highlights, when around 2000 Apristas were imprisoned during the 1930s, many referred to El Frontón as their place of greatest torture and suffering, an experience which contributed significantly to APRA’s vision of prisoners as revolutionary heroes. Fernando Belaúnde Terry (President of Peru 1963–68 and 1980–85) and Hugo Blanco were also imprisoned on the island during the decades preceding the conflict (Gorriti Citation1999, 244).5

El Frontón was not originally designed as a detention centre for political prisoners. Aguirre argues that, between 1850 and 1930, attempts were made to modernise and reform the prison system (Aguirre Citation2005, 86–87). However, a “despotic approach to punishment, one that emphasised revenge and deterrence over rehabilitation and reform” generally prevailed, with the result that prisoners continued to be “treated like savage beasts”, facing persistent problems of overcrowding, poor sanitation, and a lack of resources. As Buntinx describes, “El Frontón was to be the model jail, the modern jail. Soon, however, it became Devil’s Island (...) a place of terrible suffering” (interview with author, April, 2016). The island prison therefore held a very specific place within the Peruvian imaginary which meant that, even before the internal conflict began, it was associated with the incarceration and punishment of political prisoners.

The proselytising and propagandising actions of Senderistas once inside the prison’s walls, in this sense, built upon the way that El Frontón was imagined as a site of heroic incarceration. As Rénique argues, “not since the martyrdom of the Partido Aprista Peruano in the thirties and forties had a political organisation made a similar political use of prison space” (Citation2003, 15). The combination of El Frontón’s history and Shining Path’s use of the prison space ensured that the prison was converted from a strategic asset of the Peruvian state into a key symbolic battleground in the wider conflict.

The symbolic importance of state prisons was demonstrated during several earlier incidents in 1985–86, when state forces quickly and violently suppressed riots at the Canto Grande, El Sexto, and Chorrillos prisons in Lima, and at institutions in Arequipa, Cusco, Huánuco, and Piura (Feinstein Citation2014, 7). Then, on 18 June 1986, Shining Path prisoners initiated three days of riots in the El Frontón, Lurigancho, and Santa Bárbara prisons. Motivated by awful living conditions and the government’s attempts to move them to the new Canto Grande prison, the inmates took members of the Republican Guard and prison staff hostage (CVR Citation2003, VII, 743). They also released a list of demands including the provision of sufficient clothing and food, repair of the lighting and water systems, and the speeding up of judicial processes.

After the failure of the Comisión de Paz to resolve the situation, President García ordered the armed forces to suppress the uprisings. At Santa Bárbara the prison was quickly retaken with only two fatalities, but when the army retook Lurigancho, 124 prisoners were extrajudicially executed under the orders of Coronel Cabezas. The uprising at El Frontón lasted a day longer but, after the island fortress was shelled and destroyed by the Navy, the remaining rioters surrendered and over 70 were extrajudicially executed (Obando Citation1998, 391). In total, there were 118 deaths in El Frontón. García’s government was later criticised in a report commissioned by Congress for magnifying the gravity of the situation and creating a narrative of the riots which “would later be used to justify the high cost of human life caused by state agents” (Ames et al. Citation1988, 245).

Responses to the massacres in the Peruvian media have tended to represent these incidents either as a justified response to the threat of insurgency, or as an over-zealous and excessive, but ultimately necessary, response to the crisis (Aguirre Citation2013, 209). Such justifications are only possible when the lives of the victims of the massacres are considered unworthy. This logic justifies state violence by weighing the lives of rioting Senderistas against those whose lives, power, and wealth they threatened (in this case, whiter and more middle-class communities in suburban Lima). Not only do such responses reflect the ungrievable position ascribed to Senderistas in Peruvian society, there are also strong parallels between these justifications and those which continue to be deployed in support of the Peruvian military’s counterinsurgency operation. In this sense, Senderistas and indigenous communities held a social position during the conflict, which meant that their deaths could be justified, by some, through appeals to national security.

The suppression of the riots at El Frontón and Lurigancho therefore had a deeper significance than simply restoring order. Having struggled to locate evasive Shining Path patrols in the sierra, the armed forces took the opportunity to eliminate a highly visible (and, for limeños, worryingly proximate) insurgent presence through direct confrontation. This was not simply an attempt to defeat Shining Path militants, but an opportunity to exterminate a dangerous Other. Furthermore, the suppression of Shining Path was shaped by a distinct understanding of what type of population ought to represent the modern Peruvian nation, a project which Drinot argues expresses “racialized understandings of the ontological capacity of different population groups to contribute to, and indeed be subjects of, projects of ‘improvement’ and national ‘progress’ more generally” (Citation2011, 186).

Prisons did not function effectively as a mechanism for rehabilitating and reintegrating insurgents back into the population, but instead were used to isolate Senderismo and anyone who ostensibly could have come into contact with it. The goal of such a repressive mechanism is, Calveiro argues, the “extermination of the Other who is unremittingly excluded and eliminated, whether s/he represents a real threat or is subject to a pre-emptive course of action” (Citation2014, 218). This Other which the state was trying to segregate, contain, and eliminate was nominally Shining Path militants, yet the way in which state agents conducted their operations meant that the profile of those suspected of being insurgents was highly racialised.

Furthermore, prisons were not the only example of spaces of exception created during the conflict; they existed within a range of mechanisms deployed by the Peruvian state to exercise a form of disciplinary sovereign power against target populations. The creation of clandestine detention centres as part of the military’s counterinsurgency operation in the interior, including Cuartel Los Cabitos and La Casa Rosada in Huamanga (CVR Citation2003, VII, 71), also represents this logic of exclusionary violence. These spaces of exception operated through a medicalised understanding of political radicalism and indigeneity, viewed through the logic of contagion and quarantine. This logic is deeply embedded in other aspects of Peruvian culture in an imagined form of permanent colonial confrontation between constructed ideas about Peru’s “modern”, clean, whiter colonial core (centred on Lima) and an Orientalised, violent, radical Andean interior (Willis Citation2018, 135). As Theidon (Citation2012, 10) notes, the idea that there are “two Perus” was most infamously described by the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa in response to the murder of eight journalists by the community of Uchuraccay in 1983. He argued that in Peru there are “men who participate in the twentieth century and men (...) who live in the nineteenth century”, the latter in an “Andean world that is so backwards and so violent” Theidon (Citation2012, 10).

In this sense, the state’s military response to Shining Path was informed by a desire to keep this supposedly barbaric, uncivilised world at bay. The logics of violence deployed during the counterinsurgency operation were simultaneously exclusionary, disciplinary, and intensely racialised, and they also came to shape the state’s response to the 1986 prison riots. This exercise of state violence was both reflective and productive of attitudes towards prison inmates and Senderista militants which persist to this day. Because accused insurgents were not considered to have grievable lives, the state was able to perpetrate the massacres. Media responses justified the killing of Senderistas, and these justifications continue to be deployed today to support the discursive exclusion of Shining Path memories from acceptable memory discourse.

Recuperating Senderista memories in Peruvian culture

As alluded to earlier, however, cultural producers have begun to re-examine the motivations of Shining Path militants and have, to an extent, reconstituted Shining Path militants as grievable lives.6 Some, such as Santiago Roncagliolo, have rebalanced representations of Senderista violence with depictions of the human rights violations perpetrated by the Peruvian armed forces. In Roncagliolo’s Abril rojo (Citation2011), for example, the author does not deny that Senderistas committed atrocities, but renders a relatively sympathetic portrait of Shining Path through comparisons with the military, with the protagonist told by an imprisoned Senderista that he has a “mania for distinguishing between terrorists and innocents” (Roncagliolo, Citation2011, 119). The graphic artist Jesús Cossio has used comics to highlight the dual position of Senderistas as perpetrators and victims of violence, particularly in his collection Barbarie: Violencia política en el Perú, 1985–1990 (Cossio Citation2015) which ends with the bombing of El Frontón. Other artefacts, such as Joel Calero’s film La última tarde (2016) and Alarcón’s “Flood” (2006), have explored the social marginalisation of working-class communities to communicate something of the initial liberatory potential of Shining Path’s mobilisation and why so many joined the group, and other radical organisations, in the 1980s. The latter makes an explicit connection between marginalised communities on the periphery of Lima (in the San Juan de Lurigancho neighbourhood) and those detained without charge in El Frontón and Lurigancho before the riots. Alarcón also alludes to the reduction of these inmates to an expendable mass of “bare life” when the story culminates with the suppression of the riots: “Someone, at the very highest level of government, decided that none of it was worth anything. Not the lives of the hostages, not the lives of the terrucos” (Citation2006, 15).

Out of this range of sources which have sought to understand and explain, if never vindicate, Shining Path, perhaps the most significant is José Carlos Agüero’s (Citation2015b) memoir Los rendidos.7 As with Lurgio Gavilán’s Memorias de un soldado desconocido (Gavilán Citation2014), it offers valuable insight into the perspectives of those who, although not involved in the central command of Shining Path, had a personal connection to the group. In the case of Los rendidos, the parents of the author were both Shining Path militants who were extrajudicially executed by state agents: his father at El Frontón, his mother after the riots at Canto Grande prison in 1992. Agüero’s memoir focuses on complicity, guilt, and forgiveness after episodes of political violence, and highlights the stigma attached to him through the memory of his parents.

The first two chapters deal with the nature of stigma and guilt, themes which continue throughout the book. Agüero refers to a kind of internal shame, the “vergüenza de la piel enrojecida o los manos sudorosas” (shame of blushed skin and sweaty hands) and the need to accept that “miembros de tu familia (...) tus amigos más queridos (...) cometieron actos que trajeron muerte” (members of your family, your friends and loved ones committed acts that brought death) (Agüero Citation2015b, 24). Yet he must also deal with the fear that neighbours or friends will discover who his parents were, and that he too will be socially castigated because he has “una familia que para una parte de la sociedad está manchada por crímenes, que es una familia terrorista” (a family that for a part of society is marked by crimes, that is a terrorist family) (19). In short, Agüero talks both about his internal guilt for his parents’ actions, and about a kind of socially enforced shame which he suffers as a result of being the son of Senderistas. This is significant, insofar as it points to another way in which Shining Path militants and those who died in the prison massacres are excluded from society, their memories and perspectives deemed unworthy of being heard. As Claudia Salazar Jiménez (Citation2017) argues, Agüero uses his narrative to demonstrate the manner in which the children of Senderistas are constructed as Other.

There are clues, in the language used and scenarios portrayed by Agüero, that there is an intersectional dimension to this Otherness. When he says that social castigation made him feel “contagioso” (contagious) (40), or that “además de pobres, estábamos sucios” (beyond being poor, we were dirty) (30), Agüero conjures up a narrative of cleanliness and decency in which associations to Shining Path have permanently tarnished his family’s reputation. As De la Cadena (Citation2000) argues, discourses of decency and cleanliness in Peruvian history have distinctly racial and class-based connotations which position the subject as an unclean, undesirable element, unable to meet middle-class standards of decency. Within the context of the internal conflict, this narrative has further meaning, considering that, as Drinot (Citation2011, 188) argues, Lima’s more middle-class population began to see indigenous families as vehicles for Senderista violence throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Furthermore, when Agüero refers to others calling his mother a “terruca” (colloquial term for “terrorist”) (28), or his family “terroristas” (37), there are highly political and racialised connotations to these terms (Burt Citation2006, 34; Aguirre Citation2011, 103) which go beyond their debatable immediate accuracy. Despite the fact that the social exclusion to which Agüero refers is ultimately enforced by his own neighbours and community, the framing of Los rendidos through this language can be seen to reflect the pervasiveness and internalisation of the narrative that not only were Shining Path primarily responsible for the internal armed conflict, but so were Peru’s working-class and indigenous communities.

By investigating the nature of culpability and innocence, Agüero therefore asks whether the children of Senderistas should be ostracised because of the crimes of the parents, and explores how he can remember his parents’ lives without forgetting their crimes. On this point he is unequivocal; his parents “no son inocentes” (were not innocent), but militants who “hicieron la guerra” (made war) and contributed to the damage done to Peruvian society (Agüero Citation2015b, 67). It would be a mistake to think that Agüero aims to vindicate his parents, but he does contextualise his criticisms of Sendero with parallel criticisms of state violence: “Los enemigos. Los culpables. Mis padres lo fueron. También lo fueron estos políticos” (enemies, the guilty. My parents were, but so are these politicians) (Agüero Citation2015b, 128). Their violent acts, he argues, do not preclude their right to have their story told, nor for their children to grieve for them. That is to say, Agüero’s shame stems from a desire to grieve for his parents which he feels the need to suppress due to the assertion of others that their lives are ungrievable, and not worth remembering.

This right to bear witness may seem abstract, but it is central to how we understand the prison massacres. The state’s actions at El Frontón and Lurigancho were not just a suppression of the riots but an attack on the rights of Senderistas to exist, an impulse that is replicated in the stigma that castigates prisoners as terrorists deserving of death. In a television interview, Agüero (Citation2015a) argued that his work was not designed to pardon his parents, but to contextualise their actions: “Qué ganamos diciendo que solamente fueron (...) patológicos, enfermedades, manchas, simplemente ‘terroristas’? Yo creo que no lo eran. Eran seres complejos, que tenían motivaciones complejas, equivocados sin ninguna duda, pero no pueden estar reducidos a ser seres del mal que debemos destruir” (What do we gain from saying that they were pathological, diseased, simply ‘terrorists’? I don’t think they were. They were complex, they had complex motivations, wrong without doubt, but they cannot be reduced to something bad we ought to destroy). The importance of recognising the complexity of war is further discussed in Los rendidos as Agüero argues that the time has come to decentre the category of “víctima” (victim) in discourse around the conflict: “[no es que] las demandas de verdad, justicia y reparación hayan sido atendidas. Es que la necesidad de comprender la guerra también se hace poderosa” (it’s not that the demands of truth and justice have been attended to, but that the need to understand the war has become more powerful) (Agüero Citation2015b, 96). So when he talks about “personas con experiencias complejas, que no se dejan encasillar en las categorías de víctima y perpetrador” (people with complex experiences that cannot be pigeonholed into categories of victim and perpetrator), Agüero (Citation2015b, 97) is talking about the complexity of human experience in the lives not just of his parents, but of all participants in the conflict.

In this sense, Agüero humanises his parents not by forgiving them, but by dismissing the categories that might have been used to describe them: Senderista, perpetrator, terruco, victim, guerrilla, hero. He uses his memoir as a symbolic cultural space in which it is possible to reverse the violent, physical erasure of Senderistas on the island itself. It is clear that this reversal does not aim to justify his parents’ actions; Agüero is in constant conflict between the “alivio” (relief) and “culpa” (guilt) which he feels when he thinks about his mother’s death (Citation2015b, 43). But he also ties these complex personal feelings to his interpretation of the wider conflict, condemning state violence and the “padecer injusto que miles de personas han vivido” (unjust suffering that thousands have suffered) (Agüero Citation2015b, 43) as they wait for relatives to return from places like El Frontón, the ESMA, or the DINA.8

By humanising and adding complexity to the memories of Senderistas such as his parents, Agüero posthumously ascribes value to the lives that were lost during the massacres. Los rendidos renders Senderistas as grievable not by forgiving their actions, but by drawing attention to their complex motivations, human fallacies, and the forms of violence that have been inflicted upon them in life and in death. In this sense, Agüero creates a symbolic cultural space in which Senderista memories can be integrated into a fuller understanding of the internal conflict. This cultural space is necessary because of the forms of censorship which have limited debate around Senderista memories in Peruvian society and which prevent El Frontón itself from being used as a physical space for the recuperation of Shining Path memories.

El Frontón in Lima’s post-conflict memoryscape

Los rendidos is therefore an important cultural artefact that can help us to identify the limits of acceptable memory discourse: the line between who should and who should not be remembered. Whilst the memoir draws attention to the forms of castigation and exclusion inflicted upon Senderista memories, however, it is important to recognise that this discursive exclusion is reinforced through a combination of direct and indirect interventions in public space. An analysis of how different forms of commemorative practice are privileged, excluded, and “curated” (Milton Citation2018) in public space reveals that Senderista memories of the prison massacres, and the conflict as a whole, continue to be underrepresented and excluded in Lima’s memoryscape.

El Frontón is situated a short distance off the coast opposite the Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y Inclusión Social (LUM), itself just off the Malecón which runs along the clifftops of southern Lima’s Costa Verde. Whereas El Frontón stands silent and closed to the public, at times impossible to see through the murky garúa (a low-lying fog which descends on Lima in winter months), the LUM and the Malecón are in the lively and tourist-friendly district of Miraflores, a Lima suburb known for its fashionable restaurants, well-kept green spaces, and the popular Larcomar shopping centre. Taken together, the combination of the former prison island, the LUM, and the Malecón is revealing as to the versions of history presented to Miraflores’s relatively affluent residents, and indeed its many international tourists.

For example, one of the Malecón’s parks is named after Miguel Grau (a Peruvian Admiral during the War of the Pacific) and another after Antonio Raimondi (a Peruvian-Italian scientist and geographer from the nineteenth century). Ironically, in another park El Frontón can be seen from the base of the Faro de la Marina, Miraflores’s infamous lighthouse designed by Gustav Eiffel and dedicated to the Peruvian Navy (who bombarded El Frontón in 1986). This commemoration of military heroes and figures from the nineteenth century promotes a limited degree of engagement with a nostalgic view of a paternalistic Peruvian Republic.9 Whilst there are numerous Pre-Pizarrian huacas dotted across Lima that are walled off, protected and preserved for tourists as sites of “transcendental importance”, the destroyed prison fortress of a not-distant past is disregarded as rubble (Gordillo Citation2014, 256). This suggests the fetishisation of one type of ruin, and the privileging of particular narratives about Peru’s pre-Incan and Republican history, because it represents a past that is both uncontroversial and lucrative for the tourism industry. By contrast, El Frontón, a site that has had far greater political consequences for the lives of modern Peruvians, is closed off and abandoned, along with the memories that reside there.

The LUM disrupts and adds something different to this landscape to some extent, yet the museum has undoubtedly been designed to attract a particular audience through its emplacement and through the narrative it evokes. Mario Montalbetti argues that, by choosing to locate the museum in Miraflores, “a beautiful landscape, the gastronomic cordon, a zone for tourists and cafés (...) the Commission seems to want to say that the LUM ought to be part of Lima’s tourist circuit” leading to the “banalisation of experience through tourist commercialisation” (Montalbetti Citation2013, 65–66). In this sense, the LUM’s emplacement risks contributing to a sanitised and depoliticised narrative of the conflict, particularly because of the stark contrast between the museum’s affluent environs and the social inequalities which precipitated the conflict (and persist to this day).

Inside the LUM, the massacres are not entirely absent from the discussion as they are featured both in the introductory timeline of the conflict and in José Carlos Agüero’s recorded video interview. However, in a manner similar to the cultivated green spaces along the Malecón, the museum’s content is carefully curated to limit criticism of the armed forces to the bare minimum. As Milton has highlighted (Citation2018), this is in no small part due to interventions by state and military figures to diminish the role of state violence in the LUM’s museography. Such interventions not only make the exhibition of Senderista memories in the museum impossible, but have also led to the condemnation of human rights-based narratives on the grounds of apología del terrorismo (Feinstein Citation2014).

For instance, in 2017, LUM Director Guillermo Nugent left his position after a controversy emerged around a temporary exhibition entitled Resistencia visual 1992, curated by the artist Karen Bernedo. Nugent resigned after complaints from Fujimorista politician Francesco Petrozzi that the exhibit at the LUM, depicting acts of violence perpetrated by Shining Path and the Fujimorista state in 1992, was “full of hatred against Fujimorismo” (Willis Citation2018, 308). This prompted Culture Minister Salvador del Solar to meet with Nugent to discuss the exhibit (which was eventually removed). The incident acts as further proof of Milton’s argument that Fujimoristas and military figures have used forms of “hard” and “soft power” to intervene in memory debates in post-conflict Peru, criticising the CVR’s human rights narrative and promoting their own supposed role as saviours of the nation (2018, 189). Whilst the naming of streets and parks after military figures reflects the military’s soft cultural power (Milton Citation2018, 189), Nugent’s departure reflects a more direct, “hard” form of intervention into memory discourse.

Beyond the LUM, similar interventions have been made to limit engagement with Senderista memories in public space across Lima. The 2012 Ley de Negacionismo made illegal any act considered to be “expressing approval for, justifying, denying or minimising” acts of terrorism and the impact of Shining Path and MRTA violence upon Peru (Human Rights Watch Citation2012). In 2014, Interior Minister Daniel Urresti intervened when an arts exhibition, entitled En tu nombre, was opened which displayed artwork by Senderista prisoners (La República Citation2014). And in September 2016, a controversy erupted when the Peruvian press discovered that a mausoleum had been built in northern Lima for Senderista militants who died during the 1986 prison massacres, and that commemorative marches had been held in their memory (BBC Mundo Citation2016). President Kuczynski stated that the bodies should be removed and the mausoleum closed, and a complaint was filed that such an act constituted apología. These events demonstrate two things: firstly, that there is some limited appetite in Peru to commemorate the prison massacres and Senderista memories of the conflict; secondly, that state figures are willing to deploy more formalised means of silencing Shining Path voices when necessary.

For these reasons, there is a clear disconnection between the image of Peru presented to visitors to the LUM/the Malecón and the recent history of state violence represented by El Frontón, obscured but still often visible from the cliff top. El Frontón is what Schindel might call “an abjected space”, one which evokes memories of those violently excluded from society but whose significance appears to be being re-articulated by processes of capitalism (Schindel Citation2014, 199). The forms of urban planning and limited commemorative practice that have been enacted on the Malecón have reshaped the area as an attractive site for tourists and middle-class communities alike. In this sense, Lima’s memoryscape, its geography of sites that commemorate the internal conflict and other moments from Peru’s past, reflects the lack of engagement with Senderista memories in memory discourse, and the low status of episodes of violence in which Shining Path militants could potentially be cast as victims. To an extent, El Frontón is the antithesis of Lucanamarca, the site of the massacre of 69 campesinos by Shining Path, which Almeida Goshi argues is an emblematic case because it was committed by Senderistas, and not by the armed forces (Citation2016, 241).

It might be tempting to believe that these voices have been excluded from memory debates because of the violent acts, “fundamentalist” ideology (Degregori Citation1991, 181), and quasi-religious organisational structure (Portocarrero Citation2012) associated with Shining Path. However, it is also crucial to recognise the active role played by the Peruvian state in facilitating the political, social, and discursive exclusion of Shining Path militants, during the conflict and in commemorative practice. In this sense, accounts such as Los rendidos (and others highlighted above) are essential for reconstituting Senderistas as grievable lives, yet for many these sources on the conflict remain outside of the limits of acceptable memory discourse in Peru.

Conclusion

Today, El Frontón is a space that gives testimony to the forms of power deployed by the Peruvian state during the internal conflict, as well as over a longer period of the twentieth century. The history and continued silence of El Frontón tell us that Shining Path militants are, to this day, not considered grievable in Peruvian society and that their lives should not be remembered. Although some have tried to recuperate Senderista memories through forms of cultural production, a lack of engagement with the island’s history (as well as opposition to controversial projects which commemorate Shining Path militants) tells us that some forms of memory-making in Peru are privileged over others. For example, it is very difficult to imagine a situation in which Senderista memories could be recuperated to the same extent as the military memories discussed by Milton (Citation2018). As Greene (Citation2016, 42) argues, in post-conflict Peru there exists a “retrospective demonization” of Shining Path, a situation in which it is deemed necessary to be vocally anti-Shining Path in order to avoid accusations of apología del terrorismo and which leaves “scant political or discursive space in Peru to explore why so many people joined Sendero” (Theidon Citation2012, 323).

The Ley de Negacionismo confirms this, but it can also be read from Alarcón’s and Agüero’s work, and be witnessed in Lima’s memoryscape. Whereas Los rendidos highlights the continued social exclusion and castigation of Shining Path militants, Lima’s memoryscape demonstrates the image of Peru which state agents and the Peruvian armed forces believe in: the image of a paternal, masculine state with a tradition of naval and military heroes. El Frontón is almost absent from this city-text, but it can never be fully erased from the landscape. So today it remains in silence but ever-present, periodically emerging from the fog ().

Acknowledgment

The research for this article was supported by the award of a PhD Studentship from the London Arts and Humanities Partnership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Willis

Daniel Willis conducts research and writes on the themes of space, violence, and memory in Peru’s internal armed conflict (1980–2000). In 2018 he completed a PhD in History and Latin American Studies at the Institute of the Americas, University College London. The research for this article was supported by the award of a PhD Studentship from the London Arts and Humanities Partnership.

Notes

1 Alongside Abril rojo, Roncagliolo has also attempted to understand the motivations of Senderista militants through his journalistic account of the conflict, La cuarta espada (2007). Other cultural sources on prisons and political exclusion in Peru include Alberto Durant’s film Alias: ‘La Gringa’ (1991), which deals directly with the 1986 massacres, Hombres y rejas (1937) by Juan Seoane, and José María Arguedas’s El sexto (1961). The latter describes the prison experiences of Apristas and Peruvian Communists in the 1930s based on the author’s own experience of incarceration.

2 Apología del terrorismo (“terrorist apologism”) has been made illegal in Peru and carries heavy jail sentences for anyone charged. Although legally apología del terrorismo refers to any act which seeks to justify violence perpetrated by Shining Path and other militant groups, the phrase has been deployed to criticise and delegitimise the work of the CVR and criticism of state violence during the conflict.

3 Similar theoretical frameworks which utilise the work of Agamben, Butler, and Michel Foucault have been deployed previously to analyse Peruvian social formations in the work of Drinot (Citation2011; Citation2014) and Boesten (Citation2014).

4 Examples include Claudia Llosa’s La teta asustada (2009) and Palito Ortega’s La casa rosada (2016).

5 Belaúnde was briefly imprisoned in 1959 after opening a proscribed convention for his newly formed political party Acción Popular. The revolutionary peasant leader Hugo Blanco was arrested in Cusco in 1963 and transferred to El Frontón, which he described as a “notorious hell” (Wall Citation2018, 60–61).

6 The existence and circulation of these cultural artefacts demonstrate that there is no “hard” ban on sources sympathetic to Shining Path, but that a combination of censorship and forms of “soft” power is deployed to condemn, contest, and denounce these artefacts as apología. See Milton (Citation2018, 164–85).

7 José Carlos Agüero is a poet and historian involved in numerous projects associated with memories of political violence in Peru, including the Lugar de la Memoria, Tolerancia y Inclusión Social in Lima, where there is a video recording of him speaking about his experiences as the son of Senderista militants.

8 As Agüero (Citation2015b, 44) notes, ESMA and DINA were clandestine detention centres used to disappear political activists during periods of military dictatorship in Argentina and Chile respectively.

9 Majluf (Citation1994, 38) has also identified a wave of public sculptures in mid-nineteenth-century Lima which she argues attempted to “create and mould a collective memory and national spatiality”. Elements of this expansion are still highly visible in central Lima and continue to greatly outnumber public artworks related to the internal conflict.

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 1995. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Agüero, José Carlos. 2015a. “José Carlos Agüero: ‘Los Rendidos es una historia de amor’.” LaMula, July 7. https://redaccion.lamula.pe/2015/07/07/jose-carlos-aguero-sobre-los-rendidos/jorgepaucar/.

- Agüero, José Carlos. 2015b. Los rendidos: Sobre el don de perdonar. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Aguirre, Carlos. 2005. The Criminals of Lima and Their Worlds: The Prison Experience, 1850–1935. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Aguirre, Carlos. 2011. “Terruco de m…: Insulto y estigma en la guerra sucia peruana.” Histórica 35 (1): 103–139.

- Aguirre, Carlos. 2013. “Punishment and Extermination: The Massacre of Political Prisoners in Lima, Peru, June 1986.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 32 (Suppl 1): 193–216.

- Aguirre, Carlos. 2014. “Hombres y rejas. El APRA en prisión, 1932–1945.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines 43 (1): 7–30.

- Alarcón, Daniel. 2006. “Flood.” Chapter 1. In War by Candlelight. London: Harper Perennial.

- Almeida Goshi, Claudia. 2016. “Entre sombras y silencios: los testimonios acerca de las muertes de Marcian Huancahuari y Olegario Curitomay.” In Dando Cuenta, edited by Francesca Denegri and Alexandra Hibbett, 239–264. Lima: Fondo Editorial de PUCP.

- Ames, Rolando, Jorge del Prado, Javier Bedoya, Felipe V. Oscar, Agustín Haya de la Torre, and Aureo Zegarra. 1988. Informe al Congreso sobre los sucesos de los penales. Lima: Comisión Investigadora sobre los Sucesos de los Penales.

- BBC Mundo. 2016. “El controvertido mausoleo de Sendero Luminoso que crearon en Perú.” BBC Mundo, September 29. http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-37513361.

- Boesten, Jelke. 2014. “Inequality, Normative Violence, and Livable Life: Judith Butler and Peruvian Reality.” In Peru in Theory, edited by Paulo Drinot, 217–243. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Buntinx, Gustavo. 2014. “Su cuerpo es un isla en escombros: derivas icónicas desde las ruinas de El Frontón.” In Frontón. Demasiado pronto / Demasiado tarde. Junio 1986 / Marzo 2009. edited by Gustavo Buntinx and Víctor Vich, 12–53. Lima: Micromuseo e Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Burt, Jo-Marie. 2006. “Quien habla es terrorista’: The Political Use of Fear in Fujimori’s Peru.” Latin American Research Review 41 (3): 32–62.

- Butler, Judith. 2009. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? London: Verso.

- Calveiro, Pilar. 2014. “Spatialities of Exception.” In Space and the Memories of Violence, edited by Estela Schindel and Pamela Colombo, 205–218. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (CVR). 2003. Informe Final. Lima: Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación.

- Cossio, Jesús. 2015. Barbarie: Violencia política en el Perú, 1985–1990. Lima: Contracultura.

- De la Cadena, Marisol. 2000. Indigenous Mestizos: The Politics of Race and Culture in Cuzco, Peru, 1919–1991. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Degregori, Carlos Iván. 1991. Ayacucho 1969–1979: El surgimiento de Sendero Luminoso. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Degregori, Carlos Iván. 2012. How Difficult It is to Be God: Shining Path’s Politics of War in Peru, 1980–1999. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Del Pino, Ponciano. 2017. En nombre del gobierno. El Perú y Uchuraccay: un siglo de política campesina. Lima: La Siniestra.

- Drinot, Paulo. 2009. “For Whom the Eye Cries: Memory, Monumentality, and the Ontologies of Violence in Peru.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 18 (1): 15–32.

- Drinot, Paulo. 2011. “The Meaning of Alan García: Sovereignty and Governmentality in Neoliberal Peru.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 20 (2): 179–195.

- Drinot, Paulo. 2014. “Foucault in the Land of the Incas: Sovereignty and Governmentality in Neoliberal Peru.” In Peru in Theory, edited by Paulo Drinot, 167–189. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Feinstein, Tamara. 2014. “Competing Visions of the 1986 Lima Prison Massacres: Memory and the Politics of War in Peru.” A Contracorriente 11 (3): 1–40.

- Fried Amilivia, Gabriela. 2016. State Terrorism and the Politics of Memory in Latin America: Transmissions across the Generations of Post-Dictatorship Uruguay, 1984–2004. Amherst, MA: Cambria Press.

- Gavilán, Lurgio. 2014. Memorias de un soldado desconocido. Autobiografía y antropología de la violencia. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- González, Olga M. 2011. Unveiling Secrets of War in the Peruvian Andes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gordillo, Gastón. 2014. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Gorriti, Gustavo. 1999. The Shining Path: A History of the Millenarian War in Peru. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Greene, Shane. 2016. Punk and Revolution: Seven More Interpretations of Peruvian Reality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Haya de la Torre, Agustín. 1987. El retorno de la barbarie: La matanza en los penales de Lima en 1986. Lima: Bahía Editorial.

- Heilman, Jaymie Patricia. 2010. Before the Shining Path: Politics in Rural Ayacucho, 1895-1980. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Human Rights Watch. 2012. “Peru: Reject ‘Terrorism Denial’ Law.” April 9. https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/09/peru-reject-terrorism-denial-law.

- Hunt, Roseanna. 2017. “The Mausoleum and the Prison: Material and Literary Sites for the Reclamation of the Citizenship of the Senderista.” Paper presented at the annual Radical Americas Conference, London, September 11–12.

- La República. 2014. “Daniel Urresti intervino exposición de pinturas de Sendero Luminoso.” La República, December 26. http://larepublica.pe/26-12-2014/daniel-urresti-intervino-exposicion-de-pinturas-de-sendero-luminoso.

- La Serna, Miguel. 2012. The Corner of the Living: Ayacucho on the Eve of the Shining Path Insurgency. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Majluf, Natalia. 1994. Escultura y espacio público. Lima, 1850–1879. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Meza Salcedo, Américo David. 2014. “Memorias e identidades en conflicto: el sentido del recuerdo y del olvido en las comunidades rurales de Cerro de Pasco a principios del siglo XXI.” PhD diss., Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

- Mbembe, Achille. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40.

- McClintock, Cynthia. 1984. “Why Peasants Rebel: The Case of Peru’s Sendero Luminoso.” World Politics 37 (1): 48–84.

- Milton, Cynthia. 2018. Conflicted Memory: Military Cultural Interventions and the Human Rights Era in Peru. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Montalbetti, Mario. 2013. “El lugar del arte y el lugar de la memoria.” In La memoria histórica y sus configuraciones temáticas: una aproximación interdisciplinaria, edited by Juan Andrés Bresciano, 243–256. Montevideo: Ediciones Cruz del Sur.

- Nora, Pierre. 1989. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations, no. 26: 7–24.

- Obando, Enrique. 1998. “Civil-Military Relations in Peru, 1980–1996: How to Control and Coopt the Military (and the Consequences of Doing so).” In Shining and Other Paths, edited by Steve J. Stern, 385–410. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Palmer, David Scott. 1986. “Rebellion in Rural Peru: The Origins and Evolution of Sendero Luminoso.” Comparative Politics 18 (2): 127–146.

- Portocarrero, Gonzalo. 2012. Profetas del odio: Raíces culturales y líderes de Sendero Luminoso. Lima: Fondo Editorial de PUCP.

- Rénique, José. 2003. La voluntad encarcelada: las ‘luminosas trincheras de combate’ de Sendero Luminoso del Perú. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Roncagliolo, Santiago. 2011. Red April. Translated by Edith Grossman. London: Atlantic Book

- Salazar Jiménez, Claudia. 2017. “Cuando los hijos recuerdan: Escrituras del yo y construcción de la memoria en la narrativa peruana del post conflicto armado.” Paper Presented at the Annual Congress of the Latin American Studies Association Congress, Lima, April 28–May 1.

- Schindel, Estela. 2014. “A Limitless Grave, Memory and Abjection of the Río de la Plata.” In Spaces and the Memories of Violence, edited by Estela Schindel and Pamela Colombo, 188–201. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Theidon, Kimberly. 2012. Intimate Enemies: Violence and Reconciliation in Peru. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Vich, Víctor. 2015. Poéticas del duelo. Ensayos sobre arte, memoria y violencia política en el Perú. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Villapolo Herrera, Leslie. 2003. “Senderos del desengaño: construcción de memorias, identidades colectivas y proyectos de futuro en una comunidad Asháninka.” In Luchas locales, comunidades e identidades, edited by Elizabeth Jelin and Ponciano del Pino, 145–174. Madrid: Siglo veintiuno de España.

- Wall, Derek. 2018. Hugo Blanco: A Revolutionary for Life. London: Merlin Press.

- Willis, Daniel. 2018. “The Testimony of Space: Sites of Memory and Violence in Peru’s Internal Armed Conflict.” PhD diss., University College London.