ABSTRACT

This study examines the relationship between employee voice suppression by workplace authorities (i.e. supervisors) and the formation of employees’ attitudes towards political authority. We test whether the effect of experienced voice suppression by supervisors on employees’ preference for authoritarian governance is positive, negative or nonlinear. The hypotheses are tested on original data gathered within the Dutch Work and Politics Survey 2017 (N = 7599), which allows for a wide range of demographic and organisational control variables. The results favour a nonlinear effect of suppression on employees’ authoritarianism. These results support the notion that political attitudes are dynamic and that the workplace plays a role in shaping them.

Introduction

Parallel with the current increase in global political tensions, the concept of authoritarianism is (re)gaining popularity, often appearing in headlines of both academic and popular sources. Mainstream media use the term generously to describe certain political leaders and their supporters, most commonly Trump (Chomsky, Citation2017; Frum, Citation2017; Taub, Citation2016), Putin (Douglas, Citation2017; Kaylan, Citation2016) and Erdogan (Beesley, Citation2017; Cook, Citation2016; Stephan & Snijder, Citation2017). In such circumstances, it is increasingly important to study factors that explain support for authoritarianism. Specifically, this study sets out to examine the effect of employee voice suppression by the supervisors on employees’ authoritarian attitudes.

Authoritarianism is the attitude concerned with obedience to authority on the one hand and individual autonomy on the other. Interpersonal differences in authoritarianism are commonly explained trough the effects of upbringing (Altemeyer, Citation1988), genes (Ludeke et al., Citation2013) and personality (Butler, Citation2000). However, other potential antecedents of authoritarianism remain under researched. Traditionally, authoritarianism is viewed as a stable disposition, personality trait, or even a syndrome (Adorno et al., Citation1950), meaning that one’s authoritarianism is not expected to vary much in adulthood. Contrary to this static view we follow the notion that socialisation is a life-long process (Dawson & Prewitt, Citation1968; Sapiro, Citation1994) and argue that formative socialisation experiences in adulthood also have an effect on authoritarianism. Thus, our study investigates the potential effect of socialisation in adulthood on authoritarianism. We focus on the effect of workplace social interactions as one of the primary sources of adult socialisation. Specifically, we investigate how suppression of employees’ voices by the supervisor influences employees’ preferences for authoritarian political leadership.

We argue that voice suppression by supervisors – as the authority figures at the workplace – affects employees’ attitudes toward workplace authorities, and that these attitudes may generalize to attitudes regarding political authorities. The experience of voice suppression by supervisors can be differently interpreted by suppressed employees, depending on a multitude of individual and contextual factors. Ultimately, perceived authoritarian treatment by the supervisor, such as voice suppression, is likely an experience formative for authoritarian attitudes. For example, suppression may incite fear or anger towards the supervisor; and, in line with these emotions, justification of or aversion to workplace authority. Authoritarian attitudes formed at the workplace due to experienced suppression may spillover to authoritarian attitudes regarding society at large. While there is some research on the relationship between structural work factors and political authoritarianism (Kitschelt & Rehm, Citation2014; Lipset, Citation1959), we focus on the effect of specific interactions with workplace authority on authoritarian attitudes.

Our approach not only sheds a different light on authoritarianism as a malleable attitude rather than a personality trait or a stable ideology – it also emphasises the importance of considering adult political socialisation at the workplace as a plausible factor in life-long formation of political attitudes. We find that supervisor suppression indeed affects authoritarian attitudes. However, the direction of this relationship depends on the experienced severity of the suppression incidence. Employees who experienced suppression as very severe hold more authoritarian attitudes than ones who did not experience suppression, while those who experienced medium severity of suppression hold less authoritarian attitudes. In the following sections, we explain the main concepts and outline the theoretical rationale.

The effect of adult socialisation on authoritarianism

Authoritarianism can broadly be defined as an attitude characterised by belief in absolute obedience or submission to someone else’s authority, as well as the administration of that belief through the oppression of others (Altemeyer, Citation1981). Therefore, two dimensions of authoritarianism can be distinguished: authoritarian submission (of oneself to the authority) and authoritarian aggression (through oppression of others).

Most explanations for individual differences in authoritarianism focus on the effects of genetic factors and early parental socialisation. Findings of behavioural genetic research suggest that approximately 50% of variance in political attitudes can be attributed to genetic influence. For example, several studies independently confirmed that heritability of conservatism is over 50% (Eaves et al., Citation1999; Martin et al., Citation1986; Bouchard, Citation2004). These studies imply that the remaining half of variance in the said political attitudes is affected by environmental effects.

The influence of environmental factors on social attitudes, including political ones, is referred to as socialisation. Socialisation is commonly defined as a process of learning to participate in social life (Mortimer & Simmons, Citation1978). Extensive research has been done on the influence of early parental socialisation on political attitudes (Achen, Citation2002; Dalton, Citation1980; Jennings et al., Citation2009). For example, studies consistently show that children of parents holding authoritarian political attitudes tend to grow up to hold authoritarian attitudes themselves (Altemeyer, Citation1988; Duriez et al., Citation2008; Duriez & Soenens, Citation2009). This concordance can be at least partly attributed to parental socialisation (Bouchard & McGue, Citation2003). Namely, people who hold authoritarian attitudes in a political sense tend to also apply an authoritarian parenting style (Peterson et al., Citation1997; Rohan & Zanna, Citation1996), which entails close supervision, high demands, frequent and harsh punishments, and a distinct hierarchy (Baumrind, Citation1968). The finding that this parenting style tends to incite children’s authoritarianism is commonly interpreted in psychological literature as children learning to conform to rules imposed on behalf of authority. They also cease to develop their own strategies for coping with stressful events or threats, relying on authority particularly in those instances, as it provides a sense of security (Oesterreich, Citation2005). Furthermore, their anger toward the authoritarian parents cannot be expressed; therefore, it is misplaced and manifests as authoritarian aggression toward various ‘non-compliant’ groups and individuals (Adorno et al., Citation1950; Milburn & Conrad, Citation2016). Thus, experiences with suppression in childhood seem to amplify authoritarianism.

On the other hand, the influence of adult socialisation on authoritarianism is less studied, as is the case with the effect of adult socialisation on political attitudes in general. This lack is probably because children and adolescent attitudes are considered malleable, while adult attitudes are considered relatively stable (Alwin & Krosnick, Citation1991; Sears & Funk, Citation1999). However, the few longitudinal studies that had been conducted conclude that party identification is stable, but not fixed throughout adulthood (Lewis-Beck et al., Citation2008), while basic political attitudes are even less stable (Alwin et al., Citation1991; Converse & Markus, Citation1979; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008). Therefore, more recent political socialisation research draws attention to adult political socialisation. For example, Niemi and Hepburn (Citation1995) posit young adulthood as the critical period of political socialisation, while Sears and Brown (Citation2013) appeal for considering political socialisation throughout the entire life span. Following these recent developments we argue that adult socialisation may have an important effect on political attitudes such as authoritarianism, even though perhaps not as strong as the effect of socialisation in the critical period of childhood. Thus, we investigate what occurs when one experiences authoritarian behaviour in adulthood, particularly at one’s workplace.

The spillover from the workplace to political life

Because work is central to people’s lives, both in terms of its importance and the time spent on it, the workplace is one of the primary sources of adult socialisation (Greenberg et al., Citation1996). We argue that attitudes formed at the workplace spill-over from the workplace to the political realm. The literature on political behaviour offers at least three sociological mechanisms that explain how the workplace might have an effect on the political realm: (1) skill development, (2) occupational autonomy and task structure, and (3) the workplace as a facilitator of crosscutting discourses.

The first mechanism is the use of skills developed at the workplace in political life. The idea is that involvement in organisational decision making enhances political skills (Bandura, Citation1994; Carter, Citation2006; Greenberg et al., Citation1996). The mechanism claimed responsible for this spillover is that people generalise problem-solving techniques developed and practiced in the workplace and use them in other spheres of life, particularly in political life (Kohn, 2001; as cited in Kitschelt & Rehm, Citation2014). This way, workplace participation affects political participation.

The second work-to-politics spillover mechanism operates via ‘occupational autonomy and task structure’ (Boix & Posner, Citation1998; Kohn, Citation1969; Oesch, Citation2008, Citation2014). The idea is that the characteristics of one’s occupation, particularly people’s experiences with job autonomy and authority, are generalised and transposed to other social spheres and thus form one’s political attitudes (Kitschelt & Rehm, Citation2014).

The third and final spillover mechanism is crosscutting discourse. The arena for political deliberation at work is less subject to self-selection than one’s usual social environments, and thus likely to induce encounters between people with differing viewpoints. Such encounters increases political tolerance toward people with political perspectives other than one’s own (Mutz & Mondak, Citation2006). Therefore, participation in crosscutting discourse at work is expected to influence political attitudes.

What described three mechanisms have in common is generalization as the mechanism underlying the spillover from workplace to political realm. Generalisation theory posits that people transpose values, attitudes and behaviours developed and proved effective in one social context to other contexts (Mortimer & Simmons, Citation1978). This is precisely what is observed in the described workplace-to-politics spillover mechanisms: generalisation of behaviour developed at the workplace in the first, and generalisation of attitudes formed at the workplace in the second and third mechanism.

Building on this literature, we propose a new, fourth mechanism of generalisation from workplace to political attitudes: generalization of interactions with workplace authority. This mechanism assumes that attitudes towards workplace authority formed through interactions with workplace authority generalise to attitudes towards political authority. We believe interpersonal interactions between supervisors and employees reflect the occupational autonomy and task structure. As such, the new mechanism we propose is a refinement of the previously mentioned generalisation mechanism that describes the effect of occupational autonomy and task structure on political attitudes. Kitschelt and Rehm (Citation2014) find that occupations with low skill and authority levels are associated with higher levels of political authoritarianism. In this paper, we focus on social interactions that reflect workplace authority (such as voice suppression), rather than on structural workplace characteristics. This helps uncover more specific mechanisms underlying the spillover on political attitudes, since authority relations are more clearly expressed through social interactions than through formal hierarchical positions (Stanojevic et al., Citation2020). Moreover, generalisation is more successful the more a certain stimulus or situation resembles the context linked to the initial socialisation (Shepard, Citation1987). Since the supervisor is perceived as an authority figure at the workplace, we argue that interaction with the supervisor can affect employees’ attitudes regarding workplace authority, which then generalise to attitudes regarding authority on a societal level.

Perception of supervisor suppression as authoritarian behaviour

A crucial social interaction with the supervisor that may affect employees’ attitudes regarding authority is voicing discontent with a problem at work. According to Hirschman (Citation1970), members of different kinds of organisations faced with an organisation-related problem can react in one of two ways: with exit or voice. The same choice is available when an employee is faced with a problem at work. While exit means simply leaving the company, voice can take many forms. There is an impressive body of literature on the predictors and consequences of employee voice, in particular on employee’s voice, generally understood as the expression of ideas, suggestions and opinions in order to improve work and work organisations (Van Dyne & LePine, Citation1998). In the present study, we define voice as any activity of individual employees, groups of employees or their representatives aimed at improving either personal work conditions or the work conditions of an entire group one belongs to. Thus, voice in our definition is exclusively directed at improving employment conditions for oneself or one’s group, such as signalling high work pressure, unsafe working conditions, demanding higher wages or claiming unpaid wages. Examples of the way of how employees can express their voice are raising the problem at work directly to the supervisor or going on strike.

Supervisors can respond in several ways to employees voicing discontent. Depending on the situation, supervisors might choose to support employees (e.g. by accommodating them or complimenting the voicing act), to take a neutral stance (e.g. by explaining why the problem cannot be solved), to punish the employee, or to ignore the problem and the employee’s expression of it. We build on Tilley (Citation1978) and define employee voice suppression as any supervisor’s attempt to discourage, prevent, or curtail the volume, intensity, or duration of employees’ individual or collective voice. As such, employee voice suppression can take many forms and can differ in severity. Following this definition, punishing and ignoring employee voice can be considered suppressive responses to employee voice.

Moreover, research by Husband, Schenck, and Cooper (1988; as cited in Lobdell et al., Citation1993) suggests that employees voicing discontent to their supervisor perceive this as uncomfortable social interactions. This discomfort comes as no surprise considering the findings of Cooper and Husband (Citation1993), who find that employees often have the impression that the supervisors are not willing to listen to their complaints, while supervisors, on the contrary, far more often perceive that they are willing to listen. Lobdell and associates (Citation1993) build on this finding, and find additionally a negative relationship between employees’ perception of supervisors’ willingness to listen and perceived supervisors’ responsiveness. Given these findings, it is plausible that employees who voice work related discontent to their supervisors are likely to perceive a lack of willingness to listen and lack of responsiveness by the supervisors, which might be perceived as authoritarian behaviour by the supervisors.

To the extent that employees perceive punishment and ignoring by the supervisor as voice suppression, they might experience these events as authoritarian behaviour, comparable to previously mentioned parental authoritarianism. Such voice suppression is likely to be perceived as perpetuating a strict hierarchical structure in which the authority is on top and does not adhere to the interests of employees lower in the hierarchy. Employees who experience punishment by the supervisor in response to voice are especially likely to perceive such a response as authoritarian behaviour, as suppression is a defining characteristic of authoritarian behaviour, at least in regard to parenting styles (Robinson et al., Citation1995). Therefore, we argue that experiences of workplace voice suppression by the supervisor potentially affect employees’ authoritarianism, similar to how authoritarian behaviour by parents directed toward children affects children’s authoritarianism.

Thus, the research question this study attempts to answer is: how do these experiences of suppression by the supervisor affect authoritarianism?

What spills over? How voice suppression affects authoritarianism

So far, we have argued that perceived suppression of employee voice by the supervisor can be seen as authoritative behaviour and that such interaction with the supervisor can affect authoritarian attitudes within the workplace context, and finally generalise to societal-level authoritarian attitudes. However, the proposed generalisation mechanism assumes nothing about how employee voice suppression by supervisors affects attitudes towards authority. While it seems intuitive that perceived suppression by workplace authority would influence employees attitudes regarding workplace authority and generalise to attitudes regarding political authorities, the direction of the effect in question is less straight forward. Theoretically, opposing effects on authoritarian attitudes are plausible. On the one hand, experiencing suppression by an authority figure at work could increase employees’ authoritarianism, making people more submissive to authority. On the other hand, suppression could actually decrease authoritarianism, making individuals authority-averse.

It is important to note that consequences of an objective event depend on ones’ subjective interpretation of the event (Thomas & Thomas, Citation1928). In other words, employees’ subjective interpretation of experienced suppression incidence determines which affective and cognitive mechanisms are offset. Since attitudes are conceptualised as consisting of an affective, cognitive and behavioural component (Muran, Citation1991; Jain, Citation2014), we assume affective and cognitive mechanisms triggered by suppression by authority affect attitudes towards authority. These different potential affective and cognitive mechanisms lead to competing hypotheses which we empirically test. In what follows, we present the psychological mechanisms that explain the effect of suppression by the supervisor on workplace authoritarianism, which ultimately generalises to political authoritarianism.

Several psychological theories predict that having experienced suppression induces authoritarianism. First, suppression might incite fear, which is known to induce a rise in authoritarianism. Studies have found a correlation between fear and authoritarian political attitudes (Butler, Citation2013; Eigenberger, Citation1998). Some hypothesise that fear activates authoritarian tendencies because strict rules and hierarchical structures provided by authoritarian systems restore people’s sense of safety (Oesterreich, Citation2005). Therefore, fear-provoking events, such as workplace suppression, might increase one’s authoritarian submission and suppression in the workplace context, which ultimately generalise to political authoritarianism.

Furthermore, system justification theory (Jost et al., Citation2004) claims that people are generally intrinsically motivated to defend and justify any system of which they are a part, especially if that system disadvantages them. This is an unconscious tendency that helps alleviate the discomfort of cognitive dissonance that would arise from holding negative attitudes toward a system one (albeit passively) sustains. In extreme cases of hostage situations, a similar phenomenon is referred to as Stockholm syndrome, in which hostages develop positive feelings and empathy toward their captors (McKenzie, Citation2004). This behaviour is, similar to system justification, believed to be a spontaneous ego defense strategy, which can also be adaptive. For hostages, the change in attitude might increase the likelihood of obtaining freedom from captors, while for a suppressed individual in an authoritarian system, the change in attitude might improve their coping abilities with and within the system. In the case of employee voice suppression, system justification theory would suggest that suppressed employees tend to justify the suppression they are experiencing to reduce the cognitive dissonance between their attitude and their behaviour. To justify the suppression, they might adapt a more authoritarian attitude, meaning they might increase their favouring of submission to authority at work and hostility toward people who do not submit to it. This increased authoritarian attitude adaptive for the suppressive workplace context may then generalise into authoritarianism as a political attitude. Thus, based on the generalisation of workplace fear, observational learning, workplace role and system justification, we formulate Hypothesis 1:

Compared to employees who are not subjected to suppression, employees subjected to voice suppression have higher levels of authoritarianism.

While the above psychological mechanisms predict a positive effect of voice suppression on authoritarianism, suppression of voice by authority could also lessen peoples’ readiness to submit to authority and punish on its behalf, thus decreasing employees’ authoritarianism. Suppression by the supervisor might also incite anger (rather than fear) toward workplace authority and, therefore, workplace system aversion (rather than system justification). This possibility is not only intuitive on the basis that suppression is an unpleasant experience with authority, which might lead to a negative affect and attitudes toward authority. It is also supported by findings of social movements research. The social movements and mobilisation literature elaborates on this logic in the context of state suppression of protests. Gurr (Citation1970) and Oberschall (Citation1973) argue that suppression will lead to new grievances and negative emotions (mainly anger) for the suppressed protesters, especially when the suppression is considered illegitimate. This may be why, in many cases, state suppression in an attempt to stop a protest actually resulted in exacerbating it (Bayat, Citation2003; Sinjab, Citation2013). Therefore, it is plausible to assume that in some cases suppression of voice by the supervisor would result in rejecting workplace authority, and such attitude change may generalise to rejecting political authorities, thereby reducing authoritarianism. Following these suggestions from the mobilisation literature, we formulate Hypothesis 2 as follows:

Compared to employees who are not subjected to suppression, employees subjected to voice suppression have lower levels of authoritarianism.

Alternatively, some authors hypothesised a nonlinear, inverted U-shaped effect of state suppression on protest intensity, which suggests that moderate suppression causes an increase in protest intensity, while extreme suppression causes protests to decline in intensity. The evidence on this is mixed: Hibbs (Citation1973) and Francisco (Citation1996) refuted the inverted U hypothesis, but Muller and Weede (Citation1990) confirmed it. Despite the mixed empirical evidence, the theoretical reasoning for this hypothesis is that, moderate levels of suppression incite protests by creating new grievances, but the risks of protesting become too high as the suppression further increases toward the highest level; thus, protests quell (Johnston, Citation2012).

We follow this line of reasoning and theorise that employees’ authoritarianism depends on the subjective impact of experienced suppression. Although to our knowledge no research examines the possible decrease in protesters’ authoritarianism after governmental suppression, we assume that protesting an authoritarian government is inversely related to authoritarianism and that the empirical findings on increased protesting after government suppression indicate aversion to authoritarianism. Thus, we expect that voice suppression at work leads to new grievances and negative emotions towards authority, and therefore decreases employees’ authoritarianism, at least for medium subjective impact of suppression. Further, following the finding of social movements research that extremely high levels of state suppression curb protests, we expect that high subjective impact of suppression would leave employees with little choice but to adapt to the suppressive environment by aligning their attitudes to the authoritarian organisational climate.

In terms of emotional responses, we argue that moderate suppression elicits anger, while the highest levels of perceived suppression elicit fear. Anger and fear are similar emotions but differ in one’s perception of the ability to act, control or change the situation (Lerner & Tiedens, Citation2006). Therefore, if employees feel like they can (re)act (as with moderate levels of suppression), they would likely experience anger toward the suppressive authority. However, if employees perceive (re)action as too dangerous and have no control over the events in the company (as a consequence of severe suppression), they would likely experience fear of the suppressive authority.

In response to fear related to high impact of suppression, system justification may be employed, as it alleviates anxiety, uncertainty, and fear elicited by threats to the societal status quo (Fergina et al., Citation2010). Due to justifying the authoritarian organisational system, employees highly impacted by the suppression experience would adapt to the submissive role they are expected to enact within it, and even imitate the supervisor’s suppressive behaviour. These are adaptive psychological mechanisms that help coping with high-intensity suppression. By accepting one’s role and the system, the employee reduces the risk of further suppression. Similarly, by imitating the suppressive employee’s behaviour toward coworkers, employees might help keep the entire group of workers out of trouble. Generalisation of these behaviours and attitudes formed as an adaptation to a suppressive workplace would finally cause employees to adapt more authoritarian political attitudes.

We do not expect an effect of low levels of subjective impact of suppression on authoritarianism, as a low level of employers’ authoritarian behaviour is generally expected and accepted as a manifestation of corporate hierarchy. Rather, we expect an effect only of medium and high subjective impact of suppression, in opposite directions. Thus, we formulate Hypothesis 3 as follows:

Compared to employees who are not subjected to suppression, employees who report medium subjective impact of suppression have lower levels of authoritarianism, while those who report the highest subjective impact of suppression have higher levels of authoritarianism.

Methods

Data

To test these hypotheses, we use the Work and Politics 2017 Dataset created for the purpose of the ‘Linking the Discontented Employee and Discontented Citizen’ research project, of which our study is a part (Akkerman, Manevska, Sluiter & Stanojevic, Citation2017). The data were collected by administering the web-based questionnaire to 7599 Dutch citizens. Because the research aims to study the spillover from the workplace to political preferences, we limited our sample to the labour force (meaning working or looking for work). This prerequisite also limited the age range, so all participants were between 15 and 67 years old. The survey was conducted by a professional survey company (Kantar Public) that maintains a panel of households from which they recruit survey participants. The recruitment of participants is done via traditional recruitment methods, so every person in society has an equal chance of being recruited. These panels are regularly updated to enable high response rates, and participants receive monetary incentives. For the survey developed for the present study, participants were recruited from a randomly sampled panel of 145,000 households (approximately 235,000 respondents) in a manner that ensured representativeness with regard to age, gender and education. Potential participants received an email inviting them to participate in a survey that takes no longer than 20 min. Out of 12,013 approached participants, 7599 participants filled out the survey, which accounts for a 64% response rate.

The current analysis is conducted on 6414 cases, which means an additional 15% of the sample was excluded. This is because some participants could not answer the relevant questions (not employed in the past 3 years, do not have a contract, or do not have a supervisor).

Measures

To measure authoritarianism, we constructed a scale by selecting and adapting items from existing authoritarianism scales (Altemeyer, Citation1998; Rattazzi et al., Citation2007; Zakrisson, Citation2005). Since the study aims to examine the effect of workplace suppression on authoritarianism as a political attitude, the authoritarianism items are focused on ideas about proper organisation of the society, rather than more ‘personal’ reflections of authoritarian tendencies such as those related to child rearing. Furthermore, following the recent work of Van Hiel et al. (Citation2006) we allow for the possibility of left wing authoritarianism, and therefore select items that are applicable across the political spectrum. Although the initial set of items included an equal number of items focused on authoritarian submission and aggression, after examining the items’ content and the results of principal component analysis, the final scale was constructed from 4 submission and 1 aggression items, loading on one general factor of authoritarianism (for the detailed process of constructing authoritarianism scale see Appendix, Tables A1 and A2). This result should come as no surprise not only because there is a considerable similarity between the content of submission and aggression items but also because submission and aggression were often empirically found to constitute a single dimension (Rattazzi et al., Citation2007). Although the two dimensions are theoretically distinguishable, the theory also predicts that the same people who score high on submission score high on aggression. The final scale thus contains 5 items with a Cronbach’s alpha of .81.

To measure employee voice suppression by supervisors, the main explanatory variable, as a first step, participants were asked whether they had experienced discontent with a problem at work during the past three years. Subsequently, all respondents who reported one or more forms of discontent were asked whether they voiced this problem, and if yes, how. Participants who indicated having had a problem and who voiced this to their supervisor were then presented with a list of possible supervisor responses, so they could recognise responses they experienced. This list consisted of two supportive, two neutral and nine suppressive responses (see Appendix, ), presented to participants mixed within one list of possible responses to voice. The nine suppressive responses were constructed based on previous findings (Bernhardt et al., Citation2009), expert judgement, and a pilot study (N = 440). Additionally, participants could indicate supervisor responses they experienced that were not covered by the list, which were subsequently judged by experts to determine if they correspond to suppression or not. Participants could indicate having experienced multiple types of suppression from the listed ones. From these responses, we constructed a dichotomous variable indicating suppression, for which 1 indicates having experienced at least one of the nine suppressive responses, while 0 indicates not having experienced any of the suppressive responses (including employees who did not have an issue at work, had an issue but have not voiced to the supervisor, or voiced it and experienced a supportive or a neutral response).

In addition to the dichotomous measure, we use a continuous measure of suppression that captures the subjective impact of suppression. Although some types of suppression (e.g. bullying or threatening) cause on average greater subjective impact than others (e.g. ignoring), as shown in of the Appendix, subjective impact also depends on the individual characteristics of the suppressed employee. Namely, the same suppression incidence could be interpreted differently by different employees, and therefore affect them in different ways. Therefore, it is important to account for subjective impact of suppression. After indicating their supervisor’s response, participants were asked to indicate how much they feel each type of suppression they reported affected them on a scale from 1 to 5 (using a Dutch phrase that implies emotional impact), where 1 corresponds to ‘it did not affect me at all’, and 5 to ‘it affected me very much’. The subjective impact of suppression measure was computed using the maximum subjective impact of suppression score participants reported among all of the experienced instances of suppression (1–5), while 0 was assigned to participants who did not experience suppression. Thus, in cases of participants who reported having experienced multiple instances of suppression, subjective impact of suppression reflects the highest impact participant had reported. This measure contains all information contained in the dichotomous suppression variable, with the additional aspect of subjective impact (as participants who had a score of 0 on the dichotomous variable have a score of 0 on the subjective impact variable as well, while those who scored 1 on the dichotomous measure have a score ranging from 1 to 5 on the subjective impact measure).

We controlled for gender, age, education, the type of employment contract, union membership,Footnote1 sector, whether employees are supervisors themselves, and the number of work hours per week. Educational data were collected according to 8 ordinal categories but split into low, middle and high for the analysis. The sector was determined based on the Standard Industrial Classification (United Nations, Citation2008) as private or public. We controlled for several types of contract, including temporary with a prospect of a permanent contract, temporary without such a prospect, solo self-employed (freelancers’), and contracts with flexible arrangements (including working for a temp agency, working on a on call or zero hour contract). presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analyses, and the correlations between them.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Correlation matrix.

Results

We first test a null-model, predicting authoritarianism only using control variables. shows that having lower or middle education level and working more hours per week are both related to higher authoritarianism, while having a temporary contract is related with lower authoritarianism. Next, in Model I we test Hypotheses 1 and 2 using OLS regression analysis. To test the effect of suppression on authoritarianism we use the dichotomous measure of suppression, which signifies whether (1) or not (0) respondents were subjected to suppression by supervisors. Using this dichotomous measure, we find no significant difference between employees who experienced suppression, and those who did not as shown in . Furthermore, we find that Model I, which uses the dichotomous suppression measure, does not explain the variance in authoritarianism any better than Model 0, which uses only control variables. Thus, the mere occurrence or absence of voice suppression has neither a significant positive nor negative effect on employees’ authoritarianism, therefore refuting both Hypothesis 1 (predicting positive effect) and Hypothesis 2 (predicting negative effect).

While the dichotomous measurement of suppression treats all suppressive responses of the supervisor as being equally severe, the subjective impact of suppression measurement allows for assessing the experienced intensity of suppression. In the remainder of this section, we report on the tests of our hypotheses with this measure of suppression.

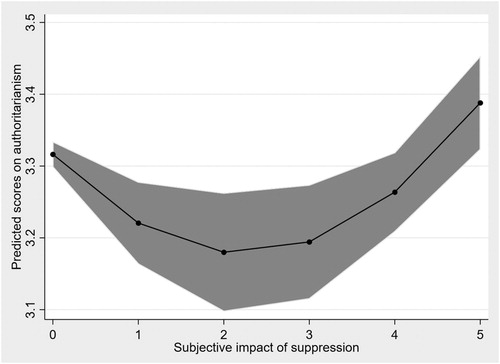

To test Hypothesis 3 on the nonlinear effect of different levels of suppression, we test a linear (Model II) and a quadratic (Model III) OLS regression model. The results in , Model II refute the prospect of a linear effect of subjective impact of suppression on authoritarianism, as predicted in Hypotheses 1 and 2. Conversely, the results of testing Model III confirm the presence of a quadratic effect (as both the squared and the linear effect of subjective impact of suppression are significant). We observe that, in the function form f(x) = ax2 + bx + c, our model can be expressed as f(x) = 0.026 × 2 − 0.114x + 3.032, which indicates a parabola. If a > 0 (as in our case where a = 0.026), the parabola opens upwards. The fitted regression line with confidence intervals shown in confirms this U-shaped relationship. Thus, these results confirm Hypothesis 3 on the nonlinear effect of subjective impact of suppression on employees’ authoritarianism, whereby medium subjective impact of suppression is associated with lower, and high subjective impact with higher authoritarianism compared to the employees who were not suppressed. As a robustness check, we also conduct a regression with dummies for each level of subjective impact of suppression. The results of this analysis are in line with the results of nonlinear regression model and can be found in the Appendix, .

Table 3. Results of regression analysis predicting authoritarianism: model 0 using only control variables, and model 1 using occurrence or absence of suppression, N = 6610.

Discussion and conclusion

We investigated the spillover of suppression of employee voice by the supervisor to authoritarianism. We analysed the responses of employees on a questionnaire regarding their experiences of suppression by supervisors and their (dis)agreement with statements on authoritarianism. We find no difference in authoritarianism if we only distinguish between people who experienced and those who have not experienced suppression by the supervisor. However, examining the subjective impact of suppression reveals a nonlinear relationship between suppression and authoritarianism: in line with hypothesis 3 based on the empirical findings of the social movements research, employees who reported medium subjective impact of suppression exhibit lower levels of authoritarianism compared to those who did not experience suppression, whereas those employees who reported high subjective impact of suppression exhibit higher levels of authoritarianism. Such U-shaped relationship indicates that a medium experienced subjective impact of suppression incites frustration and anger towards workplace authority, thus reducing the tendency to hold authoritarian attitudes. High experienced subjective impact of suppression, however, incites fear because the consequences of confronting workplace authority are experienced as severe. Therefore, high subjective impact of suppression offsets adaptive responses to fear – system justification, imitation and role assignment. Once attitudes concerning the workplace authority are formed, they generalise to attitudes concerning political authority due to the similarity of the two social contexts.

Table 4. Results of regression analysis predicting authoritarianism with subjective impact of suppression, N = 6610.

Our study offers valuable insights in at least four respects. Firstly, the association found between the impact of employee voice suppression and authoritarianism suggests that authoritarianism is not necessarily a stable disposition or personality trait, as traditionally assumed, but that experiences in adulthood can serve as formative for people’s authoritarianism. This finding also supports the more recent adult socialization approach to political attitudes (Dekker & Meyenberg, Citation1999), particularly the workplace socialization approach (Greenberg et al., Citation1996).

Secondly, our study offers an alternative, ‘social’ approach to the known ‘structural’ approach to workplace socialisation, emphasising interactions with workplace authority as formative political socialisation experiences. While previous studies focus on static work characteristics, such as task structures, occupation and job security (e.g. Kitschelt & Rehm, Citation2014; Kohn & Schooler, Citation1969), our study suggests an alternative mechanism – namely, the generalisation of attitudes formed through interactions with workplace authority. This shift of focus from the structures to interactions is in line with Clegg et al. (Citation2006), who point out that interactions are key signifiers of power relations.

Furthermore, our finding is of practical importance, because workplace interactions between supervisors and employees are easier to influence than organisational structures, for instance through procedures or awareness-training of supervisors. Awareness of the subjective impact of suppression by the supervisor is important because of its potential far reaching consequences. Ideally, awareness about the possible emotional and political consequences of voice suppression would incite conscious, careful consideration of ways in which they respond to voice, especially since the consequences cannot be foreseen (i.e. depending on both the specific instance of suppression and employees’ subjective interpretation of it). As mentioned in the measures section, our data reveals that different examples of supervisors’ reactions to voice elicit differing average intensities of emotional response, but also that some variability per specific supervisors’ response (see Appendix, ), meaning that employees differ in their subjective affective interpretation of the same perceived supervisor response. This might imply that it is not only important which specific supervisor response is given in reaction to voice, but other factors that might influence the subjective interpretation of such response play a role (i.e. workplace climate, job satisfaction, previous interactions with the supervisor and other contextual factors).

Lastly, our micro-level theory on the spillover of interactions at the workplace warns of the potential far reaching consequences of recent labour market trends. Several recent labour market developments have changed the employees’ position vis à vis the supervisor, increasing their susceptibility to suppression. Here, we name two. Firstly, European labour markets in particular have witnessed a change from traditional permanent contracts to more flexible contract forms (part-time work, teleworking, flexible and fixed contracts, pay-rolling, and temporary agent hiring). Traditional vehicles for collective expressions of discontent, e.g. union representation or works councils, are less suitable for these flexible workers (Jansen et al., Citation2017; Jansen & Akkerman, Citation2014). Therefore, these workers must rely on individual voice, which makes them vulnerable to suppression (Sluiter et al., Citation2020). Secondly, since the creation of the internal EU market, the free flow of labour has facilitated labour migration across EU member state borders. Given their (initial) language disadvantages, lack of union representation and frequent relocation, labour migrants have a vulnerable position in the labour market, and examples of the exploitation of labour migrants abound (SCP, Citation2013). These labour market developments fundamentally change employees’ position in the organisation and potentially increase the likelihood of experiencing voice suppression by the supervisor. Our findings suggest that these labour market trends can affect political trends. For example, increased instances of suppression that are perceived as severe or threatening might drive a surge in authoritarian attitudes.

Turning to limitations, the cross-sectional design of our study prompts some caution with regard to causality claims. In this case, a third variable could be at play affecting both authoritarianism and subjective impact of suppression, or previous levels of authoritarianism may affect subjective impact of suppression. We attempted to reduce the chances of the former by controlling for eight relevant potential confounders. As for potential reversed causality, we believe that the findings support the interpretation that suppression affects employees’ authoritarianism instead of vice versa. If authoritarianism were to affect how people experience suppression, we would expect that the more authoritarian people are, the more accepting of suppression by authority they may be. Thus, if employees’ authoritarianism is affecting their subjective impact of suppression, we would expect highly authoritarian employees to be less subjectively impacted by the experience of suppression. Conversely, employees low on authoritarianism would experience stronger subjective impact of suppression, because they would not perceive it as legitimate. However, this is not the pattern we find. Conversely, high levels of authoritarianism are connected with a high (rather than low) subjective impact of suppression, and low levels of authoritarianism with a medium (rather than high) subjective impact. We therefore tentatively conclude that our findings support the causal effect of suppression by supervisors on authoritarianism.

Another limitation is the inability to empirically test the theorised mechanisms we assumed drive the effect of suppression on attitudes towards workplace authority. We theorised that medium subjective impact of suppression would elicit anger toward authority and corresponding adaptive reactions to suppression in situations when one feels in control, while high subjective impact would elicit fear and corresponding mechanisms adaptive when one does not feel in control. While the findings certainly suggest that different mechanisms must be at work at different levels of subjective impact of suppression, the current study design does not allow for an empirical test of the proposed five mechanisms (fear, role enactment, imitation, system justification and anger).

Notwithstanding these limitations and suggestions for further research, our study shows that experiences with suppression of voice by the supervisor influence employees’ authoritarianism, the direction of the association being dependent upon the impact of suppression. This finding is important for the literature on adult political socialisation, especially the role of interactions with workplace authority and its spillover to politics. Additionally, it shows the practical importance of workplace interactions between supervisors and employees, and its potential impact on politics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Antonia Stanojevic is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Management Research, Radboud University, where she investigates effects of workplace socialisation on political attitudes and voting. Her interdisciplinary research has recently been published in Political Psychology Journal. Her research interests also include environmental psychology, behavior change and intergroup relations. [[email protected]]

Agnes Akkerman is Professor of Labour Market Institutions and Labour Relations at the Department of Economics, Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Her research interests include industrial conflict, co-determination, and worker participation and voice; protest mobilisation and repression. She has recently published her interdisciplinary research in the American Journal of Sociology, Political Psychology, Socio Economic Review, and Comparative Political Studies. [[email protected]]

Katerina Manevska is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Radboud University, Nijmegen. She is a Cultural Sociologist with a special interest in employment relations, interethnic relations, and political change in the West (see: www.katerinamanevska.com). She recently published in American Journal of Cultural Sociology, Political Psychology and Socio Economic Review.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The data on union membership was – retrospectively – collected at a later time point than the other variables (Akkerman, Geurkink, Manevska, Sluiter & Stanojevic, Citation2018). Due to panel attrition, by this point 1591 participants dropped out of the study, so we were unable to obtain the information on their union membership. Thus, in order to control for it we included a dummy variable for the missing cases on union membership, alongside the dummy for union membership.

References

- Achen, C. H. (2002). Parental socialization and rational party identification. Political Behavior, 24(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021278208671

- Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswick, E., Levinson, D. J., & Stanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. Harper Brothers.

- Akkerman A., Manevska K., Sluiter R., Stanojevic A. (2017). Work and Politics Panel Survey 2017, Nijmegen, Radboud University.

- Akkerman A., Geurkink B., Manevska K., Sluiter R., Stanojevic A. (2018). Work and Politics Panel Survey 2018, Nijmegen, Radboud University.

- Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism. University of Manitoba press.

- Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. Jossey-Bass.

- Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 47–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60382-2

- Alwin, D. F., Cohen, R. L., & Newcomb, T. M. (1991). Political attitudes over the life span: The Bennington women after fifty years. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Alwin, D. F., & Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 169–195. https://doi.org/10.1086/229744

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). Academic Press.

- Baumrind, D. (1968). Authoritarian vs. authoritative parental control. Adolescence, 3(11), 255–272.

- Bayat, A. (2003). The “street” and the politics of dissent in the Arab world. Middle East Report, 33(1; ISSU 226), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1559277

- Beesley, A. (2017, March 8). Alarm raised on Turkey’s drift towards authoritarianism. https://www.ft.com/content/975eb990-035b-11e7-aa5b-6bb07f5c8e12

- Bernhardt, A., Milkman, R., Theodore, N., Heckathorn, D., Auer, M., DeFilippis, J., González, A. L., Narro, V., Perelshteyn, J., Polson, D., & Spiller, M. (2009). Broken laws, unprotected workers: Violations of employment and labor laws in America’s cities. California Digital Library, University of California.

- Boix, C., & Posner, D. N. (1998). Social capital: Explaining its origins and effects on government performance. British Journal of Political Science, 28(4), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123498000313

- Bouchard Jr., T. J. (2004). Genetic influence on human psychological traits: A survey. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 148–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00295.x

- Bouchard, T. J., & McGue, M. (2003). Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences. Developmental Neurobiology, 54(1), 4–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/neu.10160

- Butler, J. C. (2000). Personality and emotional correlates of right-wing authoritarianism. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 28(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2000.28.1.1

- Butler, J. C. (2013). Authoritarianism and fear responses to pictures: The role of social differences. International Journal of Psychology, 48(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.698392

- Carter, N. (2006). Political participation and the workplace: The spillover thesis revisited. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 8(3), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2006.00218.x

- Chomsky, N. (2017, May 11). Trump’s only ideology is ‘me’, deeply authoritarian & very dangerous. RT. https://www.rt.com/news/387981-chomsky-trump-dangerous-interview/

- Clegg, S. R., Courpasson, D., & Phillips, N. (2006). Power and organizations. Pine Forge Press.

- Converse, P. E., & Markus, G. B. (1979). Plus ca change … : The new CPS election study panel. American Political Science Review, 73(1), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1954729

- Cook, S. A. (2016, July 11). How Erdogan made Turkey authoritarian again. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/07/how-erdogan-made-turkey-authoritarian-again/492374/

- Cooper, L. O., & Husband, R. L. (1993). Developing a model of organizational listening competency. International Listening Association Journal, 7(1), 6–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.1993.10499112

- Dalton, R. J. (1980). Reassessing parental socialization: Indicator unreliability versus generational transfer. American Political Science Review, 74(2), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/1960637

- Dawson, R. E., & Prewitt, K. (1968). Political socialization: An analytic study. Little, Brown.

- Dekker, H. H., & Meyenberg, R. H. (1999). Politics and the European younger generation: Political socialization in Eastern, Central and Western Europe. BIS Verlag.

- Douglas, L. (2017, July 20). Trump’s favourite G20 dinner date? An authoritarian, of course. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jul/20/donald-trump-vladimir-putin-meeting-g20-authoritarianism

- Duriez, B., & Soenens, B. (2009). The intergenerational transmission of racism: The role of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 906–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.05.014

- Duriez, B., Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2008). The intergenerational transmission of authoritarianism: The mediating role of parental goal promotion. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(3), 622–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.08.007

- Eaves, L., Heath, A., Martin, N., Maes, H., Neale, M., Kendler, K., Kirk, K., & Corey, L. (1999). Comparing the biological and cultural inheritance of personality and social attitudes in the Virginia 30,000 study of twins and their relatives. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 2(2), 62–80. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.2.2.62

- Eigenberger, M. E. (1998). Fear as a correlate of authoritarianism. Psychological Reports, 83(3_suppl), 1395–1409. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3f.1395

- Fergina, I., Jost, J. T., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2010). System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of “system-sanctioned change”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(3), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209351435

- Francisco, R. A. (1996). Coercion and protest: An empirical test in two democratic states. American Journal of Political Science, 1179–1204. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111747

- Frum, D. (2017, March 1). How to build an autocracy. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/03/how-to-build-an-autocracy/513872/

- Greenberg, E. S., Grunberg, L., & Daniel, K. (1996). Industrial work and political participation: Beyond “simple spillover”. Political Research Quarterly, 49(2), 305–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299604900204

- Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton University Press.

- Hibbs, D. A. (1973). Mass political violence: A cross-national causal analysis (Vol. 253). Wiley.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states (Vol. 25). Harvard university press.

- Jain, V. (2014). 3D model of attitude. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 3(3), 1–12.

- Jansen, G., & Akkerman, A. (2014). The collapse of collective action? Employment flexibility, union membership and strikes in European companies. In M. Hauptmeier & M. Vidal (Eds.), Comparative political economy of work (p. 186–204). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jansen, G., Akkerman, A., & Vandaele, K. (2017). Undermining mobilization? The effect of job flexibility and job instability on the willingness to strike. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 38(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X14559782

- Jennings, M. K., Stoker, L., & Bowers, J. (2009). Politics across generations: Family transmission reexamined. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 782–799. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609090719

- Johnston, H. (2012). State violence and oppositional protest in high-capacity authoritarian regimes. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-2930

- Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25(6), 881–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x

- Kaylan, M. (2016, September 16). Putin brings back the KGB as Russia moves from authoritarian to totalitarian. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/melikkaylan/2016/09/20/putin-brings-back-the-kgb-as-russia-moves-from-authoritarian-to-totalitarian/#3fcf1db8398a

- Kitschelt, H., & Rehm, P. (2014). Occupations as a site of political preference formation. Comparative Political Studies, 47(12), 1670–1706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013516066

- Kohn, M. L. (1969). Class and conformity: A study in values. Dorsey Press.

- Kohn, M. L., & Schooler, C. (1969). Class, occupation, and orientation. American Sociological Review, 659–678. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092303

- Lerner, J. S., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2006). Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger's influence on cognition. Journal of behavioral decision making, 19(2), 115–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.515

- Lewis-Beck, M., Norpoth, H., Jacoby, W. G., & Weisberg, H. F. (2008). “The American voter” revisited. University of Michigan Press.

- Lipset, S. M. (1959). Democracy and working-class authoritarianism. American Sociological Review, 482–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089536

- Lobdell, C. L., Sonoda, K. T., & Arnold, W. E. (1993). The influence of perceived supervisor listening behavior on employee commitment. International Listening Association Journal, 7(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.1993.10499116

- Ludeke, S., Johnson, W., & Bouchard, T. J. (2013). “Obedience to traditional authority:” A heritable factor underlying authoritarianism, conservatism and religiousness. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.018

- Martin, N. G., Eaves, L. J., Heath, A. C., Jardine, R., Feingold, L. M., & Eysenck, H. J. (1986). Transmission of social attitudes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 83(12), 4364–4368. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.12.4364

- McKenzie, I. K. (2004). The Stockholm syndrome revisited: Hostages, relationships, prediction, control and psychological science. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, 4(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J173v04n01_02

- Milburn, M. A., & Conrad, S. D. (2016). Raised to rage: The politics of anger and the roots of authoritarianism. MIT Press.

- Mortimer, J. T., & Simmons, R. G. (1978). Adult socialization. Annual Review of Sociology, 4(1), 421–454. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.04.080178.002225

- Muller, E. N., & Weede, E. (1990). Cross-national variation in political violence: A rational action approach. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 34(4), 624–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002790034004003

- Muran, J. C. (1991). A reformulation of the ABC model in cognitive psychotherapies: Implications for assessment and treatment. Clinical psychology review, 11(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(91)90115-B

- Mutz, D. C., & Mondak, J. J. (2006). The workplace as a context for cross-cutting political discourse. Journal of Politics, 68(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00376.x

- Niemi, R. G., & Hepburn, M. A. (1995). The rebirth of political socialization. Perspectives on Political Science, 24(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10457097.1995.9941860

- Oberschall, A. (1973). Social conflict and social movements. Prentice-Hall.

- Oesch, D. (2008). The changing shape of class voting: An individual-level analysis of party support in Britain. Germany and Switzerland. European Societies, 10(3), 329–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690701846946

- Oesch, D. (2014). Redrawing the class map. Stratification and Institutions in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Oesterreich, D. (2005). Flight into security: A new approach and measure of the authoritarian personality. Political Psychology, 26(2), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00418.x

- Peterson, B. E., Smirles, K. A., & Wentworth, P. A. (1997). Generativity and authoritarianism: Implications for personality, political involvement, and parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(5), 1202–1216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1202

- Rattazzi, A. M. M., Bobbio, A., & Canova, L. (2007). A short version of the right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 1223–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.013

- Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819

- Rohan, M. J., & Zanna, M. P. (1996). Value transmission in families. In C. Seligman, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium, volume 8 (pp. 253–276). Erlbaum.

- Sapiro, V. (1994). Political socialization during adulthood: Clarifying the political time of our lives. Research in Micropolitics, 4, 197–223.

- SCP. (2013). Burgerperspectieven 2013, 4 Kwartaalbericht van het Continu Onderzoek Burgerperspectieven (Kwartaalthema: Arbeidsmigranten uit Oost-Europa).

- Sears, D. O. & C. Brown. (2013). Political development. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, & J. Levy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology (2nd ed., pp. 59–95). Oxford University Press.

- Sears, D. O., & Funk, C. L. (1999). Evidence of the long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions. The Journal of Politics, 61(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647773

- Shepard, R. N. (1987). Toward a universal law of generalization for psychological science. Science, 237(4820), 1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3629243

- Sinjab, L. (2013, March 15). Syria conflict: From peaceful protest to civil war. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-21797661

- Sluiter, R., Manevska, K., & Akkerman, A. (2020). Atypical work, worker voice and supervisor responses. Socio-Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwaa022

- Stanojevic, A., Akkerman, A., & Manevska, K. (2020). Good workers and crooked bosses: The effect of voice suppression by supervisors on employees’ populist attitudes and voting. Political Psychology, 41(2), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12619

- Stephan, M. J., & Snijder, T. (2017, June 20). Authoritarianism is making a comeback. Here’s the time-tested way to defeat it. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/20/authoritarianism-trump-resistance-defeat

- Stoker, L., & Jennings, M. K. (2008). Of time and the development of partisan polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 619–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00333.x

- Taub, A. (2016, March 1). The rise of American authoritarianism. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2016/3/1/11127424/trump-authoritarianism

- Thomas, W. I., & Thomas, D. S. (1928). The child in America: Behavior problems and programs. Knopf.

- Tilley, C. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. Addision-Wesley.

- United Nations. Statistical Division. (2008). International standard industrial classification of all economic activities (ISIC) (No. 4).

- Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.5465/256902

- Van Hiel, A., Duriez, B., & Kossowska, M. (2006). The presence of left-wing authoritarianism in Western Europe and its relationship with conservative ideology. Political Psychology, 27(5), 769–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00532.x

- Zakrisson, I. (2005). Construction of a short version of the right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(5), 863–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.026

Appendix

Table A1. Principal component analysis on initial set of items measuring authoritarianism.

Even though theoretically authoritarianism consists of aggression and submission, previous research rarely empirically established these as separate dimensions (Altemeyer, Citation1981, Citation1988, Citation1998; Rattazzi et al., Citation2007). Arguably, authoritarian aggression in practice implies a certain degree of submission, and vice versa. Thus, when items that focus on submission and aggression make up a single factor, it should come as no surprise.

However, our initial analysis suggests two factors: the first five items loading on the first, and the last three items loading on the second factor. Examining content of the items led to the conclusion that the last three items load separately not because they tap into authoritarian aggression, but because they imply physical violence and might therefore measure a different, violent tendency. Item number five also measures authoritarian aggression, but does not have the violent component, so it loads together with the submission items. Therefore, we decided to construct the authoritarianism scale using the first 5 items suggested by the principal component analysis, as they represent both submission and aggression, and are not confounded with the factor of violence favorability. presents the principal component analysis on the final set of items.