ABSTRACT

This article argues that contrary to cyber-pessimist beliefs, citizens’ internet use in authoritarian regimes still generates anti-regime sentiment. Using a multilevel regression analysis with country- and individual-level data for 21 authoritarian regimes (2010–2015), it shows that there is a positive effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment and that stringent internet controls do not weaken this effect. An in-depth case study of Malaysia under the BN (1957–2018) examines the causal mechanisms. Interviews with activists (22), protestors (17), and online journalists (2) reveal how the internet gave alternative Malaysian voices a platform, essentially breaking the regime’s monopoly as an information broadcaster. The consequential circulation of alternative political information exposed online Malaysians to new perspectives on the regime, which sometimes very swiftly, but most often gradually increased their anti-regime sentiment. The BN regime was unable to prevent this. It first underestimated the internet’s potential, but later failed to effectively control it.

Introduction

Once embraced for its liberating potential, current scholarship studying cyberspace in authoritarian regimes primarily sees the internet’s darker sides (i.e. Gunitsky, Citation2015; Morozov, Citation2011; Deibert, Citation2015). Contemporary authoritarian regimes allegedly have a firm control over the internet and have even managed, using surveillance and online propaganda, to craft cyberspace to their own advantage. Based on this, Deibert (Citation2015, p. 64) claims that ‘authoritarian systems of rule are showing not only resilience, but a capacity for resurgence’ (italics in original). In this article I go against this cyber-pessimist view of cyberspace in authoritarian regimes, arguing that the internet still helps to break authoritarian regimes’ control over information and communication. In particular, I argue and demonstrate that cyberspace facilitates the circulation of alternative political information in authoritarian regimes, thereby occasionally exposing online citizens to content that is critical of the regime in power. Such exposure will sometimes very swiftly, but most often gradually generate anti-regime sentiment among internet users. Contrary to cyber-pessimist beliefs, I moreover show that authoritarian regimes’ internet controls are thus very ineffective at stopping this: systems of censorship are often incomplete and easily circumvented while online propaganda frequently lacks the necessary credibility to make an impact.

I come to this conclusion on the basis of quantitative regression analyses in triangulation with 43 in-depth interviews with Malaysian activists, protestors and journalists. The multilevel regression analyses first enable a systematic investigation into the casual effect. Using country- and individual-level data for 21 authoritarian regimes (2010–2015), I show that there is a general positive effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment and that strict internet controls do not mitigate this effect. My Malaysia material subsequently examines how internet use increases anti-regime sentiment and why authoritarian regimes cannot prevent this. I describe how my fieldwork in Malaysia urged me to reconsider my initial assumptions about internet use and dissent: rather than for instant mobilisation, my interviews stressed the internet’s importance in changing the information environment. By providing alternative voices a platform the internet offered Malaysians a different outlook on their government, thereby gradually increasing their anti-regime sentiment. I finally show that the regime itself was unable to prevent this. It first underestimated the internet’s potential as a mass medium, and later simply failed to effectively control it.

My article makes two contributions. First, the argument that the internet can increase anti-regime sentiment, despite authoritarian interventions to prevent that, challenges the predominant cyber-pessimist understanding of cyberspace under authoritarian regimes. Second, I explain how internet use challenges regimes by focusing on citizens’ ideas of the regime in power. Recent research suggests that rising internet use in authoritarian regimes reduces the likelihood of anti-government protest (Weidmann & Rød, Citation2019) while having no effect on the prospect of democratisation (Weidmann & Rød, Citation2015). My article shows that internet use still challenges authoritarian regimes, yet in a less dramatic, visible way than through (directly) facilitating the overthrow of the regime or igniting mass protest. By offering online citizens a possibility to access information that is not available elsewhere, the use of the internet can gradually undermine authoritarian control.

The article starts with a short review of existing research on cyberspace in authoritarian regimes, with a particular focus on the effect of internet use on citizens’ anti-regime sentiment. This review results in two hypotheses: one predicting that internet use increases anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes, and the other that internet controls can mitigate this effect. A research design is then presented, and the results section that follows shows strong support for the more cyber-optimist hypothesis. My Malaysia material subsequently provides insight into the causal mechanisms. Finally, I explain in the conclusion why the Malaysia story is likely to hold in other regimes as well and I reflect on what my findings mean for the sustainability of authoritarian regimes.

Internet use and anti-regime sentiment

Anti-regime sentiment can be understood as the illegitimacy of a regime in the eyes of those who are ruled by it. Building on Gerschewski’s work, I define legitimacy as ‘a relational concept between the ruler and the ruled in which the ruled sees the entitlement claims of the ruler as being justified, and follows them based on a perceived obligation to obey’ (Citation2018, p. 655). A lack of legitimacy, or anti-regime sentiment, is different from the absence of political support. While the latter might derive from utilitarian cost–benefit calculations, anti-regime sentiment reflects attitudes towards the regime.

Not only democratic governments can be legitimate; citizens in authoritarian regimes might also believe that their rulers are entitled to rule (Rivetti & Cavatorta, Citation2017; Gerschewski, Citation2018). Two (interrelated) factors are important in explaining this: first, the extent to which the regime ‘delivers’ in terms of economic success, internal order and social security, and second, how the regime controls information and communication flows. It is this latter factor that the internet challenges. Traditional media – like radio, television and newspapers – was relatively easy to control for authoritarian regimes, allowing the state to strictly regulate what information subordinates were exposed to (Friedrich & Brzezinski, Citation1965; Geddes & Zaller, Citation1989). The internet challenges this ‘old media model’ in three different ways: First, it massively increases the availability and speed of information, which means today’s authoritarian regimes need to control and censor an enormous bulk of information in very little time. Second, the internet’s infrastructure does not follow national borders. Websites often operate in other countries than where their servers are based, which further complicates a state’s regulating efforts. Third, the internet blurs the distinction between information providers and consumers. The authoritarian state is no longer the sole ‘sender’ of information, as the internet’s ‘many-to-many communication’ system allows each individual to become a broadcaster (Castells, Citation2008).

What does this mean for how citizens think about the regime in power? Various scholars argue that the wealth and diversity of online information is likely to decrease the support for authoritarian regimes (e.g. Bailard, Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2014; Wagner & Gainous, Citation2013; Stoycheff & Nisbet, Citation2014; Gainous et al., Citation2018; Gainous et al., Citation2018; You & Wang, Citation2020), while increasing demands for democracy (Nisbet et al., Citation2012) and positive attitudes about the West (Wagner & Gainous, Citation2013). Once online, citizens are expected to be exposed to information – from electoral fraud to human right abuses – that the regime in power would not want them to see. This is what Bailard (Citation2014) describes as the internet’s ‘mirror function’: through the internet, a regime’s abuse of power gets revealed, and as a logical consequence, people’s approval of the regime is expected to diminish, possibly up to a point where they do not accept the status quo. Simultaneously, the internet offers a ‘window’ to learn about democratic practices in mature democracies (idem), as well as about protests that take place in other authoritarian regimes. This too could increase citizens’ anti-regime sentiment. My first hypothesis can therefore be formulated as:

H1: Individual internet use increases anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes

Other research is sceptical. First and foremost, the logic outlined above requires the internet to be an ‘open commons’, i.e. a separate, alternative sphere that exists outside of the influence of the state or corporate power. This is not the case. As documented extensively by scholars and other observers (for instance Deibert et al., Citation2012; Deibert, Citation2015, Citation2019; Gunitsky, Citation2015; Morozov, Citation2011), cyberspace is a highly contested sphere where various actors, public and private, fight for influence. In the realm of authoritarian politics, it is the state in particular – with actions ranging from censorship to polluting social media – that attempts to constrain or minimise the impact of information that could increase citizens’ anti-regime sentiment (Gunitsky, Citation2015). In line with this, various studies demonstrated that the effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment is dependent on the level of internet controls (Wagner & Gainous, Citation2013; Gainous et al., Citation2016).

Critics have also contested the notion that internet users under authoritarian rule are interested in political information about the regime in the first place. Kendzior (Citation2012, p. 5), for instance, reports that most Uzbeks do not go online for political purposes, but to socialise and go on entertainment websites. Reuter and Szakonyi (Citation2015) also found that during the 2011 Russian parliamentary election many Russians used non-politicized social media, and that their perceptions on electoral fraud therefore remained unaffected. Morozov (Citation2011, p. 80) has even suggested that the internet’s endless entertainment is an ideal distraction from politics, thereby depoliticising citizens living under authoritarian rule.

Social media platforms’ algorithms make it furthermore questionable whether alternative political information will travel to all sections of society and not merely circulate among those who already dislike the government (Deibert, Citation2019). And even if news about a government wrongdoing reaches beyond the opposition-minded ‘echo chambers’, while the theory assumes that the internet user would automatically think less about those in power, such a conclusion cannot be so easily drawn. For instance, research by Robertson (Citation2017, p. 592) on perception of electoral fraud among Russians suggests that people have ‘a tendency to treat evidence that confirms existing opinions in an uncritical manner but to discount more heavily information that does not fit a person’s prevailing view of the world’.

In sum, cyber-pessimists expect the effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment (H1) to be negligible or even negative due to the regime’s own online propaganda. They moreover expect strict internet controls to weaken the internet’s effect on anti-regime sentiment, which can be formulated as:

H2: The effect of individual internet use on anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes diminishes with a high level of internet controls

Quantitative analysis

My quantitative analysis testing the two hypotheses distinguishes itself from existing quantitative research on the topic (e.g. Bailard, Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2014; Stoycheff & Nisbet, Citation2014) in three ways. First, unlike the other studies, I integrate regimes’ internet controls in the empirical analysis (with the exception of Wagner & Gainous, Citation2013; Gainous et al., Citation2016). Hence, rather than an ‘open commons’, I treat cyberspace as a contested sphere. Second, I use a wide geographical and temporal scope, covering the period 2010–2015 for authoritarian regimes worldwide. Third, I use multiple operationalizations of anti-regime sentiment.

The effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment is likely to work primarily in regimes where citizens have limited access to alternative information and freedom of expression. Hence, it is important to include these dimensions in my definition of authoritarianism and to use these as selection criteria for my sample of authoritarian states. Freedom House’s (FH) data (Citation2018) meets these requirements. It is known for its broad understanding of democracy including states’ control over the information environment. More specifically, its index is based on expert surveys that ascribe countries a score between 1 and 7 on both political and civil liberties. FH makes a tripartite division of countries separating them into ‘free’, ‘partially free’ and ‘non-free countries’. In my analysis, I include both non-free and partially free countries, as citizens’ civil and political rights are severely restricted in both.

To test the two hypotheses I use a multilevel (hierarchical) regression model. The advantage of such an analysis is that it allows an individual-level analysis to be made, while at the same time accounting for important systematic variation at the country level. Individual-level data is needed on internet use, anti-regime sentiment, as well as on important control variables such as age and education. While various research projects gather data on politically relevant attitudes worldwide, I use data from the Asian Barometer (Citation2010, 2011, 2014), Afrobarometer (Citation2012–2015) and Arab Barometer (Citation2010, 2013, 2014) data projects, as their coverage is most complete, both in terms of countries/years that are covered, and the questions that are asked to respondents. As the Barometer projects do not have data on the post-Soviet region, data from the World Value Survey (WVS) (Inglehart et al., Citation2014) is used to cover this region. WVS data had to be recoded to make it in line with the Barometer data. Details on the recoding can be found in the endnotes.

Looking through surveys into citizens’ anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes could be problematic as respondents might be too afraid to speak freely (Tannenberg, Citation2017). The Barometer projects and WVS acknowledge this problem and try to address it in their surveys. Their interviews are always conducted face to-face and not by telephone, and the Barometer projects train interviewers to create an atmosphere of trust. All interviewers furthermore stress the confidentiality of the interview, emphasising that the interviewee remains completely anonymous. Moreover, a potential bias in the data that might still exist is likely to lead to an underestimation rather than an overestimation of the anti-regime sentiment in society, making it less problematic for the causal inferences drawn in this article. Taken together, while not treating the measurement validity issue lightly, I am confident that the Barometer and WVS data in my analysis is the most valid, reliable and comparable measurement of anti-regime sentiment under authoritarian regimes.

Dependent variables (ind. level)

My analysis uses four different indicators to gauge citizens’ anti-regime sentiment.

Trust in state institutions: This variable is a combined index of various questions in which respondents were asked how much trust they have in state institutions (the president or PM, the courts, the national government,Footnotei the parliament, the civil service, the military, the police, and the local government). For all these ordinal variables respondents had four options, ranging from ‘no trust at all’, ‘not very much trust’ and ‘quite a lot of trust’, to ‘a great deal of trust’.Footnoteii A Cronbach alpha of 0.88 demonstrates the internal consistency of the different items and justifies treating the different variables as one concept: trust in state institutions. The newly made index variable is continuous, ranges from −2.05 to 1.55, has a mean of 0, and a standard deviation of 0.75. A high score on this variable indicates high trust in state institutions.

Perceived level of democracy: This dependent variable combines three different questions. The first question asks how satisfied respondents are with the way democracy works in their country (four categories), the second asks how much of a democracy the respondent’s country is (four categories),Footnoteiii and the third question asks the respondent to rank his or her country on a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 means completely undemocratic and 10 means completely democratic (ten categories).Footnoteiv There is unfortunately no data on the post-Soviet states for these variables. A Cronbach alpha of 0.81 shows the internal consistency of the items and justifies changing the three items into a continuous variable –the perceived level of democracy – that goes from −1.69 to 1.77 with a mean of −0.03 and a standard deviation of 0.90. A high score on this variable indicates a high perceived level of democracy.

Perceived level of corruption: This variable was originally an ordinal variable with four categories measuring whether respondents believe that officials who commit crimes go unpunished in their country (‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’).Footnotev To be able to run a logistical regression, the variable is changed into a dummy by combining ‘rarely’ with ‘sometimes’ (=0) and ‘most of the time’ with ‘always’ (=1). Data on this variable is only available for Asian and African countries, but not for the post-Soviet or Arab/Middle Eastern states.

Perceived fairness of the elections: This variable was also originally ordinal in nature, measuring the extent to which respondents believe the last general elections were free and fair (‘not free and fair’, ‘free and fair, major problems’, ‘free and fair, minor problems’ and ‘completely free and fair’). Here too the variable was recoded into a dummy by combining ‘not free and fair’ with ‘free and fair, but with major problems’ (=0), and ‘free and fair, but with minor problems’ with ‘completely free and fair’ (=1). There is no data available on the post-Soviet states for this variable.

Independent variable (ind. level)

Internet use: This is an ordinal variable measuring the frequency of internet use, ranging from ‘never’, ‘hardly ever/few times a year’ or ‘at least once a month’ to ‘at least once a week’ or ‘almost daily’.Footnotevi A high score indicates high internet use.

Interaction variable (ind.level*country level)

Internet use*internet controls: To test whether the effect of internet use decreases with a high level of internet controls (H2) an interaction variable is required combining the two. To measure internet controls, I make use of FH’s Freedom of the Net data. From 2007 onwards, FH has attempted to capture countries’ freedom of the internet on a global scale. Whereas in the early days only 15 countries were included, in more recent years this number has increased to 65. The major advantage of using this data over other recent attempts to measure internet controls is that FH understands internet controls rather broadly, and acknowledges that internet freedom can be affected by many different types of state (and non-state) interference such as obstacles to access, limits to content and violations to user rights. By contrast, other existing measurements look at specific types of internet control such as censorship and filtering (Open Net Initiative, Citation2017 and the V-Dem Project from Coppedge et al., Citation2017) or at internet shutdowns (Howard et al., Citation2011) and are therefore too narrow to capture the overall level of internet controls in society. Countries get a score between 0 (no internet controls) and 100 (extreme internet controls).

Control variables (ind. level)

At the individual level I control for age,Footnotevii gender,Footnoteviii urbanisation,Footnoteix education,Footnotex employmentFootnotexi and political interest.Footnotexii For specific details on the control variables I refer to the endnotes. Other media useFootnotexiii and incomeFootnotexiv are also important controls but have a lot of missing data, which is why I put them in separate models in the online appendix. At the country level, it is important to control for factors that are likely to determine anti-regime sentiment. While it is impossible to include every phenomenon that could influence citizens’ evaluation of their government, I incorporate the most important ones by including: The level of transparency,Footnotexv repression,Footnotexvi GDP per capita,Footnotexvii the level of democracy,Footnotexviii the fairness of the elections,Footnotexix and internet penetration rates.Footnotexx In the online appendix under Table A1 I present the descriptives.

There are 21 authoritarian regimes for which both the required country-level as well as the individual-level data is available. The dataset contains 52,848 respondents covering the period 2010–2015. For some countries multiple waves were available, so these countries have observations for more than one year. displays the countries included, the year in which the survey was held and the level of internet controls. To prevent endogeneity issues, data on internet controls is used from one year prior to the year in which the survey was conducted.

Table 1. Included Countries, Year, Internet Controls and Internet Penetration.

Estimation technique

As two of my dependent variables – the trust in state institutions and the perceived level of democracy – are continuous, a normal multilevel model can be used to test the hypotheses. The results here can be interpreted similarly to a standard OLS with unstandardised coefficients, standard errors and significance tests of the intercept and the explanatory variable reported. To test the hypotheses with the other two variables – the perceived level of corruption and the perceived fairness of the elections – I run logistic multilevel regression models. My models contain random effects for internet use, meaning that internet use (at the individual level) is allowed to vary across countries to account for additional variation in the dependent variables. Comparing a model with no random effects for internet use with one that has random effects shows a better model fit for the latter. I present fixed effects models for countries in the online appendix. With the exception of the logistic models where weighting is impossible, respondents are weighted in the models. Because of missing data, the variables income and other media use are left out of my base models, but included in models shown in the online appendix.

Results

shows whether internet use increases anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes (H1). As becomes clear in all four models, this is indeed the case. Controlling for a variety of factors, both at the individual and country level, internet use decreases trust in state institutions, the perceived level of democracy, and the perceived fairness of the elections, while it increases the perceived level of corruption in the country. As the first two models have a newly made index as a dependent variable, interpreting the coefficient is not very intuitive. Nevertheless, it does provide information if one takes into account what the new dependent variables look like. The variable trust in state institutions is a variable that runs from −2.04 to 1.52 with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.74. Controlling for all other variables, the model shows that a 1-step increase on the ordinal variable internet use (with 5 categories) only leads to a drop of 0.02 in trust. Hence, the difference between people who never use the internet and people who use the internet almost on a daily basis is rather small, at around 0.08 (there are five categories, so 4 × 0.02). For the perceived level of democracy, the results look rather similar. Here the difference between people who never use the internet and those who use it on a daily basis is only 0.014 × 4 = 0.06 on a scale of −1.69 to 1.77 (with a mean of −0.02 and a standard deviation of 0.89). Thus, again, one sees that with increasing internet use, the perceived level of democracy decreases, but the effect is quite small.

Table 2. Models testing H1.

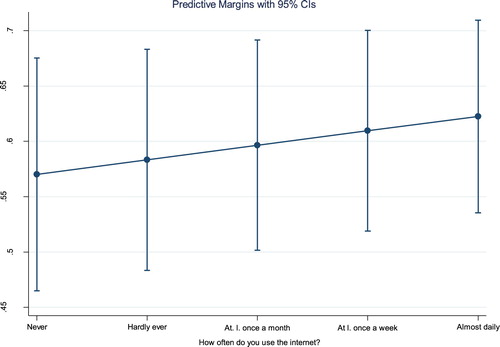

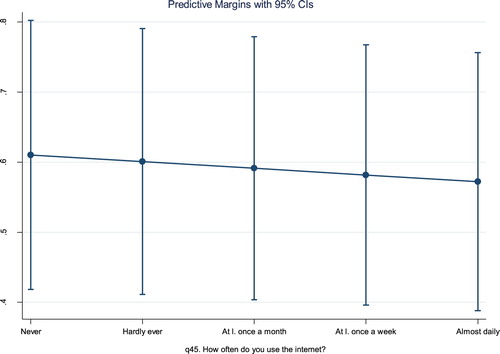

As the third and fourth models are logistic regression models, the interpretation of those coefficients is different. With regard to the perceived corruption variable, the model shows that with every 1-point increase in internet use, the log odds of thinking officials are corrupt increase by 0.059. In other words, the odds of thinking government officials are corrupt increase by around 6% with a 1-point increase in internet use. shows the probability an individual thinks government officials are corrupt at different levels of internet use, while the other variables are held at their mean. As one can see, for someone not using the internet this probability is 57%. Among those who use the internet almost daily the probability is 62%, so there is a difference of 5%. The model on the perceived fairness of the elections shows similar results (). With a 1-point increase in internet use, the log odds of thinking the elections are fair decrease by −0.077. The odds of thinking the last elections were fair decrease by 7% when internet use goes up one point. Here, among the people who never use the internet, the probability that someone thinks the elections were free and fair is 4% higher than someone using the internet daily.

In the fixed effects model (Table A2 in the online appendix, including their standardised coefficients) the results look similar, with the model predicting the perceived level of democracy and the perceived fairness of the elections now also showing significance at the 99% CI. When income is included in the models (online appendix Table A3), and the sample size shrinks as a result, the effect of internet use remains significant and only increases in terms of strength. However, once the variables measuring other media use are included (online appendix Table A4), and the Asian countries are dropped from the analysis as a consequence, the effect of internet use becomes insignificant in explaining the perceived level of democracy. The effect of internet use on the other three indicators measuring anti-regime sentiment remains similar, however. In short, internet use had a moderate positive effect on anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes in the period 2010–2015. However, the effect’s strength is not overly strong, which might be the result of regimes successfully intervening in cyberspace. In order to further examine this, I test H2.

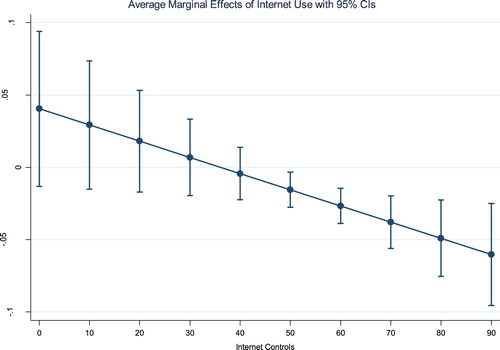

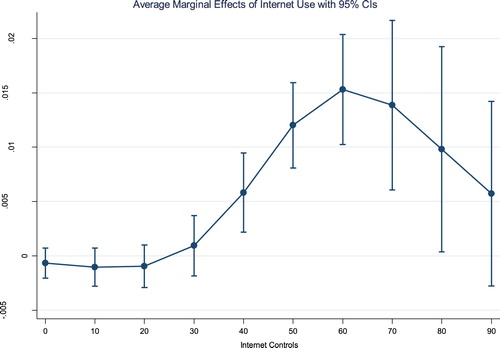

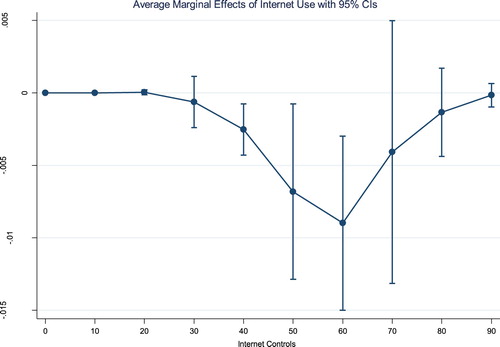

The second hypothesis tests whether the effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes decreases with a high level of internet controls (). In the first model the interaction effect is still insignificant, but the other three models show that regimes with a higher level of internet controls face a stronger positive effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment. present the marginal effects of internet use across the different levels of internet controls for the three significant models. The figures reveal that internet use starts to increase anti-regime sentiment only for higher levels of internet controls (CI interval is above zero from internet controls above +/– 40), while the last two models lose their significance for the highest level of internet controls. This might also be due to the few regimes that are included with very strict internet controls (only Vietnam and China have scores above 70).

Figure 3. Average marginal effect on the perceived level of democracy of internet use for different levels of internet controls.

Figure 4. Average marginal effect on the perceived level of corruption of internet use for different levels of internet controls.

Figure 5. Average marginal effect on the perceived fairness of the elections of internet use for different levels of internet controls.

Table 3. Models testing H2.

The fixed effects models (online appendix Table A5) further confirm the findings. All models become significant and the strength of the (interaction) effect only increases. When income is included (online appendix Table A6), the last two models lose their significance, while the first and second model again show that higher internet controls lead to a more positive effect of internet use. For the models with other media use (online appendix Table A7) it is exactly the opposite. Here, the last two models are significant but the first two models not. Also here however, the significant models show that the effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment is stronger in regimes with a high level of internet controls.

How to make sense of the counterintuitive finding that regimes with a high level of internet controls face more anti-regime sentiment due to citizens’ internet use? First, it is possible that a ‘backlash effect’ exists, which means that citizens are triggered because of the internet controls to search for what the government wants to hide (Roberts, Citation2018). Relatedly, the ‘gateway effect’ predicts that a sudden blockage of information will incentivize internet users to acquire censorship tools to access the same content that they previously had access to, which subsequently increases their exposure to other censored information. Censorship can thereby politicise internet users that were initially apolitical (Hobbs & Roberts, Citation2018). Second, citizens might get angry with the regime because of the internet controls themselves. A third explanation is that the positive effect of internet use on anti-regime sentiment was already there prior to the implementation of the internet controls. Possibly, authoritarian governments were responding to a strong effect of internet use, yet so far unsuccessfully. Fourth, it could also be the case that in regimes with strict internet controls the impact of alternative news is stronger. The more limited the circulation of alternative information, the stronger the effect might be of information that does make it through the state’s control systems. To put it simply, one critical news item a week might do more to you than dozens daily.

To conclude, the quantitative analyses show robust evidence for the claims that (1) internet use generates anti-regime sentiment in authoritarian regimes, and (2), contrary to cyber-pessimist beliefs, high internet controls do not mitigate this effect. The analyses do not, however, shine much light on how internet use increases anti-regime sentiment and why authoritarian regimes cannot prevent this. For an examination of the causal mechanisms, I therefore move the analysis from many authoritarian regimes to one: Malaysia under the Barisan Nasional (1957–2018).

Malaysia can be considered a ‘pathway case’ (Gerring, Citation2007), not serving to confirm or disconfirm my causal hypotheses, as I have already done that, but to elucidate the causal mechanisms. As Gerring (Citation2007, p. 245) outlines, ‘the obvious choice for a pathway case is a country (or unit) that undergoes variation in X1 and Y through time, as predicted by the theory, whereas all other factors (X2) hold constant’. In Malaysia from the 1990s onwards, in line with confirmed hypothesis H1, both internet use and anti-regime sentiment increased: Internet use grew from practically zero in the 1990s to almost 90% of the population in 2018, while the BN’s electoral performance worsened with each subsequent election since 2004. In practice, the rise of X1 and Y against the background of the same authoritarian regime ruling the country means that nearly all of the people I spoke to during my fieldwork in Malaysia experienced both a political life with and without the internet, allowing them to reflect on how internet use changed Malaysian politics and their own ideas about the BN coalition. Additionally, Malaysia under the BN is also an interesting case to explore the causal mechanisms behind the (rejected) second hypothesis. As the subsequent analysis will show, the BN deliberately allowed some freedoms online at first, but later ramped up its efforts to control cyberspace. Exploring how and why these attempts were (un-)successful, provides insight into the mechanisms behind H2.

Importantly, Malaysia under the BN did not resemble a North-Korean-style polity, making some authors label the regime as ‘electoral-’, ‘competitive-’, or ‘semi-authoritarian’ (Schedler, Citation2006; Levitsky & Way, Citation2010; Ottaway, Citation2003). Also Malaysia’s internet controls were even after it increased its efforts less stringent compared to other authoritarian regimes (see ). Hence, although the cross-country analysis showed that even in more repressive regimes with more stringent internet controls internet use increases anti-regime sentiment, thereby making representativeness of the case less of an issue (Gerring, Citation2007, p. 249), some caution is needed when extrapolating the Malaysian findings on the causal mechanisms to other authoritarian contexts. Potentially, different dynamics are at play in more repressive regimes. In the conclusion, I further discuss this.

Qualitative evidence

How internet use increased anti-regime sentiment in Malaysia

The initial focus of my fieldwork in 2016 was not on anti-regime sentiment but on how internet use affects protest under authoritarian rule. From 2007 onwards the Bersih movement challenged the BN regime by organising mass protests demanding clean elections and an end to the corruption in the country. Bersih’s protests brought thousands of Malaysians onto the streets on various occasions. These protests were often harshly clamped down upon by the government, who deployed teargas and water cannons, and arrested protesters. One question I went to Malaysia with was what role internet use played in the decision to join a Bersih protest. Could online information perhaps convince fence-sitters that enough other people would also be joining a protest? Or could dramatic online videos give them a decisive push? To explore this question, I held seventeen semi-structured interviews with Bersih supporters about their decision to go for a Bersih protest. Some of the interviewees actually went to Bersih rallies; others refrained from doing so because the perceived risks were deemed too high. In Tables A8 & A9 in the online appendix I include a list of my interviewees with some basic characteristics, and I explain why I use pseudonyms for the Bersih supporters but not for the activists. Although the sample was based on snowballing and can therefore not be considered as representative of the population of Bersih supporters, the interviews do give interesting insights into how internet use changed Malaysians’ political ideas.

My interviews, held in the first three months of 2016, provided only weak evidence for the internet’s immediate effects on the decision-making to join a protest. However, they did emphasise something that I was initially not very interested in: that internet use had changed the way the Bersih supporters looked at the regime. Whereas the radio, television and newspapers only broadcast the government’s narrative, on the internet my interviewees were exposed to a less rosy picture of the BN regime. For instance, Jin, a filmmaker (36), told me how through the internet, he and his parents saw ‘the other side of the story’ for the first time:

In this country the media is heavily controlled, it’s all propaganda. It’s only one side of the story. The good side of the government. That's it. So for people like my parents and me … it’s very hard to get to know the other side as well … ..My mom and dad are on FB now … and on social media, on alternative media, where they could read about the other side of the story. And that’s very important. That's the power of online media. (Jin, personal communication, 17 February 2016)

The Internet has created awareness. We can know now exactly what is happening. People have access to real information. (Li Jing, personal communication, 12 February 2016)

I think the internet played a huge role in the political awakening of many Malaysians. The press here is one narrative, the government narrative. But publications like Malaysiakini and Malaysian Insider, Raja Petra's blogs back then exposed people to alternative modes of thinking … . thinking like … .Why does it need to be this way? Why is the government basically behaving like a big parent telling us what to do when we have developed our own beliefs, our own perspective on things …

My mum is indicative of a generation of Chinese parents that likes to play it safe and that doesn’t really have an interest in politics. But until a point … she got on the internet recently and now she is sharing me all these things like ‘Oh my god, what is NajibFootnote21 doing’. ‘Look at this, what is the government doing? (Wang, personal communication, 10 February 2016)

The internet has helped in manufacturing and disseminating a sense of frustration, a collective anger. (Ibrahim, personal communication, 20 February 2016)

The empowerment of people must start through their knowledge about what is happening in this country. So I think internet and social media was the platform for them to get know what the issues are, what is actually going on in this country. (Hilman Idham, personal communication, 6 February 2016)

With internet people have access to all kinds of information. We get access to a website which tells us so much about corruption scandals and so many other issues. This has helped to create negative images of the ruling elite in the minds of people. (Toh Kih Woon, personal communication, 14 February 2016)

And for the last two years, online social media have only accelerated the awareness among the public. Malaysians don't really visit independent news websites unless they're really politically inclined or interested in what's happening. But Facebook and WhatsApp make it really easy to share stuff and short messages like a paragraph, link or an infographic. So there's a lot of that going around now, even exposing Malaysians that are not politically interested in political materials. (Anil Netto, personal communication, 15 February 2016)

How the Malaysian regime’s internet controls were insufficient

How could this happen? Did the Malaysian regime not try to control the internet? Some scholars have suggested that authoritarian states deliberately allow some freedoms online (Roberts, Citation2018; MacKinnon, Citation2012). One reason might be that it prevents a ‘backlash effect’: If it is clear the government wants to hide something, citizens might actually get incentivized to seek this information. Another is that it could help the regime in collecting valuable information on its population and the functioning of local bureaucrats (MacKinnon, Citation2012, p. 34). In Malaysia, however, it was the regime’s mismanagement of the internet that allowed cyberspace to function in the way that it did. Up until 2007, the regime underestimated the powers of the internet in shaping public opinion, and after 2007 they simply failed to bring it under their control.

Coming just out of the Asian Crisis and hence desperate to attract foreign investment, the Malaysian regime promised in 1997 to potential investors not to censor the internet (George, 2005). This did not turn out to be an empty pledge. Up until 2007, even during the Reformasi protests (1998–1999) when government critics were extensively using the internet, the regime remained committed to a free internet. This freedom allowed Malaysia’s critical online platforms, such as Malaysiakini, to flourish (Abbott et al., Citation2013, pp. 113–6). Corruption scandals, human rights abuses, ethnic discrimination and other government wrongdoings could be exposed to a growing online crowd in the early 2000s.

The regime came to realise that leaving cyberspace undisturbed came at a high political price when in late 2007 the first Bersih protest took place and a year later the BN government lost its two-thirds majority in the Malaysian parliament for the first time since independence. Internet use – by then more than half of the Malaysian population was online – greatly contributed to this political ‘tsunami’ (Miner, Citation2015). Even the BN government itself admitted this. PM Badawi remarked that the government had lost the online ‘war’ and said the authorities had made a serious misjudgement in thinking that the internet was not important. His predecessor Mahatir Mohamad said: ‘When I said there should be no censorship of the Internet, I really did not realize the power of the Internet to undermine moral values, the power to create problems and agitate people’ (as quoted in Abbott et al., Citation2013, p. 467).

From that moment on, the regime started to invest heavily in controlling cyberspace. While these investments might have been effective in some ways, they were insufficient in stopping the circulation of alternative information in cyberspace. To explain why, I use the example of the regime’s failure to ‘manage’ the corruption scandal involving former PM Najib Razak. When the corruption scandal broke in 2015, the Malaysian regime was doing everything it could to control cyberspace: it paid cyber-troopers (Yangyue, Citation2014), used Italian surveillance software (Marczak et al., Citation2014), bought off online commentators (Hopkins, Citation2014), punished online dissidents that could not be co-opted (Open Net Initiative, Citation2017), and used DDoS attacks against critical online platforms (Freedom House, Citation2017). The regime also blocked access to the portals covering the scandal once the story was published (Human Rights Watch Report, Citation2016). Yet despite all this, information on the ‘1MDB’ scandal could flourish in cyberspace, up to a point where even most Malaysians in the rural areas knew about the issue (Tapsell, Citation2018).

How was this possible? First of all, many Malaysians were internet-savvy enough to use VPN connections to access the blocked portals. One of the censored websites even explained in its Facebook posts how its content could be read from within Malaysia. Secondly, and in line with Zukerman’s ‘cute-cat theory’ (2008), Facebook and WhatsApp could become so important for the diffusion of news because the regime feared a large public outcry that a blockage of these highly popular platforms would cause. In 2018, 24 million Malaysians had a Facebook account, meaning that censoring the platform would have angered roughly three quarters of the population. Thirdly, the regime failed to steer the online discussions. Commenting on the attempt to frame the money that landed in Razak’s account as a donation from the Saudis, a government campaigner said: ‘1MDB is hard to stop. All we can do is put out material saying what the Saudis said, denying it, and making enough doubt in the voter minds that this is all “political” rather than factual' (as quoted in Tapsell, Citation2018, p. 21). On similar lines, the chief-editor of The Malaysian Insider, which was blocked for covering the 1MDB scandal, said to me:

The government still doesn’t know how to deal with the internet, the online audience is a bit higher educated. They are online to ask questions and find answers themselves. They try to find answers with their peers. The government’s online campaign is very glossy, and people don’t buy it. It is not honest. (Jahabar Sadiq, personal communication, 1 March 2016)

In a watershed moment in Malaysia’s history, the BN regime led by Razak lost the general election in May 2018. While Malaysians’ internet use cannot be seen as the only cause for the fall of the regime, it certainly played an important role (Tapsell, Citation2018; Funston, Citation2018). By exposing a vast amount of Malaysians to information that the regime itself would have liked to sweep under the carpet, internet use could steadily increase citizens’ anti-regime sentiment. This led, as we saw earlier, to increased support for Bersih, but the same process helped in toppling the regime in the 2018 elections. The regime first underestimated the internet’s powers, and later failed to control it.

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that despite authoritarian regimes’ interventions in cyberspace, internet use can still generate anti-regime sentiment. While the quantitative analysis showed systematic proof for this claim using survey data from 21 authoritarian regimes (2010–2015), my 43 interviews from Malaysia revealed how internet use can increase anti-regime sentiment and why authoritarian regimes cannot prevent this: the internet broke the Malaysian regime’s information monopoly and provided alternative voices a platform. This facilitated the circulation of alternative information and exposed online Malaysians to a different perspective on their own government. As a consequence, Malaysian internet users became increasingly critical of the BN government over time, and no longer bought the regime’s narrative. In the internet’s early years, the regime deliberately allowed a free internet, emphasising its importance for economic development. After 2007, the regime tried but failed to control cyberspace more strictly. Blockages of websites were easily circumvented, online propaganda campaigns were not credible, and the regime did not dare to take Facebook or WhatsApp down, fearing the nationwide public anger that this would cause.

As demonstrated in the quantitative analysis, internet use increases anti-regime sentiment not just in the ‘electoral-’, ‘competitive-’ or ‘semi-authoritarian’ regimes with low internet controls, but in all authoritarian regimes. But what is the external validity of the Malaysian causal mechanisms? Caution is needed here, and future research is invited to further examine the mechanisms in more repressive authoritarian contexts. Some authors suggest that authoritarian regimes deliberately allow some freedom in cyberspace (Roberts, Citation2018; MacKinnon, Citation2012): One reason might be that it prevents the earlier mentioned ‘backlash’ effect, another might be that by using porous rather than complete censorship, the regime can separate the minority of people that is willing to pay the small price of evasion from those who are not, ‘enabling the government to target repression toward the most influential media producers while avoiding widespread repressive policies’ (Roberts, Citation2018, p. 7). Alternatively, regimes might also benefit from the open online chatter on social and political issues by ‘alerting officials to potential unrest and better enabling authorities to address issues and problems before they get out of control’ (MacKinnon, Citation2012, p. 34).

And yet, there are other indications that the Malaysian mechanisms apply broadly to more repressive authoritarian contexts as well. In China for instance, operating the world’s most advanced internet control system (Freedom House, Citation2017), various studies have found – in line with my results – that internet use generates dissatisfaction with the CCP government (Lei, Citation2011; Citation2018; Xiang & Hmielovski, Citation2017). The point of these studies is not that China’s internet controls are completely ineffective, but that compared to China’s traditional media, the regime’s control over cyberspace is still less tight. Its online censorship system, for instance, cannot delete all sensitive political content (Bamman et al., Citation2012; Qiang, Citation2011, p. 55), while around 20 million Chinese citizens bypass censorship completely using VPNs (Freedom House, Citation2019). Scholars have moreover documented the ‘boundless creativity and ingenuity’ with which China’s internet users evade censorship (Link & Qiang, Citation2013, p. 81; Yang, Citation2009). Especially a ‘digital storm’, which Navarra (Citation2019, pp. 238–9) describes as a ‘brief, politically charged disturbance that suddenly begins online and quickly spreads through daily life’, has the potential to hit the Chinese regime hard. Partly due to the rise of Chinese social media platforms, the regime has in recent years increasingly been caught off guard by news about corruption and other government malpractices that in no time went viral (Lei, Citation2018, p. 142). In other words, while far from problem-free, even the Chinese internet can function as a ‘quasi-public space’ where the CCP’s dominance can be ‘exposed, ridiculed, and criticized’ (Qiang, Citation2011, p. 52).

In the aftermath of the (mostly ‘failed’) Arab Spring protests, a lot of scepticism has come to surround the idea of the internet as an enabler of positive change under authoritarian rule: perhaps internet use might sometimes facilitate short-lived collective action, but it is unlikely to foster anything positive in the long run. My research suggests, however, that the internet’s role in authoritarian regimes should not only be evaluated by looking at whether an internet-enabled protest succeeds in achieving its goals, but also by taking a more long-term perspective, considering whether internet use contributes to the availability of alternative information in society, and how citizens’ political ideas might change as a result. While we are primarily concerned with the latest internet controls, we might miss how internet use slowly undermines the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (60.8 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Marlies Glasius and Ursula Daxecker for their invaluable help and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kris Ruijgrok

Kris Ruijgrok is an Information Controls Fellow with the Open Technology Fund and teaches courses in Politics and International Relations at the University of Amsterdam.

Notes

21 Najib refers to Najib Razak, who was Malaysia’s PM at the time of the interview.

i For data purposes, the ruling party in Africa is treated as equal to the national government.

ii For the Afrobarometer and Arab Barometer data the categories were slightly different, comprising ‘not at all’, ‘just a little’, ‘somewhat’ and ‘a lot’ for Africa, and ‘I absolutely do not trust it’, ‘I trust it to a limited extent’, ‘I trust it to a medium extent’ and ‘I trust it to a great extent’ for Arab countries. The WVS data on the post-Soviet countries speaks about confidence instead of trust.

iii Categories comprise ‘not at all satisfied’, ‘not very satisfied’, ‘fairly satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’. The Afrobarometer data has five instead of four categories; here, ‘country is not a democracy’ and ‘not at all satisfied’ are collapsed into the category ‘not very satisfied’.

iv Categories comprise ‘not democratic’, ‘a democracy with major problems’, ‘a democracy with minor problems’ and ‘a full democracy’.

v The categories in the African data are slightly different: ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘often’ and ‘always’.

vi For Africa the categories comprise ‘never’, ‘less than once a month’, ‘a few times a month’, ‘a few times a week’ and ‘every day’. For the post-Soviet countries the categories comprise ‘never’, ‘less than monthly’, ‘monthly’, ‘weekly’ and ‘daily’

Extra info on control variables:

vii Age = actual age of the respondent.

viii Gender is a dichotomous variable where 1 = male, 2 = female.

ix Urbanisation, 0 = rural, 1 = urban. For some Barometer data there is information on the number of inhabitants. If so: Towns <50,000 inhabitants = rural. Towns >50,000 inhabitants = urban.

x Education, 1 = No education, incomplete primary, 2 = Complete primary, incomplete secondary, 3 = Complete secondary/Vocational type, 4 = Some university education, and 5=MA and Above.

xi Employment, 0 = not employed, 1 = employed.

xii Political interest, 1 = not interested at all, 4 = very interested.

xiii Media use, 1 = daily use of the specific medium, 5 = no use of the medium at all.

xiv Income, asks the respondent in which income group his/her household falls (5 categories). For the Post-Soviet states 10 categories are changed into 5, by combining two categories into one.

xv Level of transparency, from the corruption perception index (Transparency International, Citation2018). Scale 1 (low) to 10 (high).

xvi Repression, from the Political Terror Scale (Gibney et al., Citation2016). 1 = low repression, 5 = extreme repression.

xvii GDP per capita, from the World Bank (Citation2018). Converted to international dollars based on power purchasing parity rates.

xviii Level of democracy, measured using Freedom of the World data (Freedom House, Citation2018). 1 = least degree of freedom, 7 = most freedom.

xix Fairness of the elections, based on Freedom of the World subcomponent (0 = not fair, 12 = completely fair).

xx Internet penetration rates, data from ITU (Citation2018), measured in percentage of the population.

References

- Abbott, J., MacDonald, A. W., & Givens, J. W. (2013). New social media and (Electronic) democratization in East and Southeast Asia: Malaysia and China compared. Taiwan Journal of Democracy, 9(2), 105–137.

- Afrobarometer Data. [Egypt, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, Sudan, Morocco, Tunisia], [Round 5 & 6], [2012-2015]. Available at http://www.afrobarometer.org

- Arab Barometer Data. [Libya, Jordan, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia], [Wave 2 & 3], [2010, 2013, 2014]. Available at http://www.arabbarometer.org

- Asian Barometer Data. [Malaysia, Vietnam, China, Thailand, Philippines], [Wave 3 & 4], [2010, 2011, 2014]. Available at http://www.asianbarometer.org

- Bailard, C. S. (2012a). Testing the Internet’s effect on democratic satisfaction: A multi methodological approach, cross national approach. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 9(2), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2011.641495

- Bailard, C. S. (2012b). A field Experiment on the internet’s effect in an African election: Savvier citizens, disaffected voters, or both? Journal of Communication, 62(2), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01632.x

- Bailard, C. S. (2014). Democracy’s double edged sword: How internet use changes citizens’ Views of their government. John Hopkins University Press.

- Bamman, D., O’Connor, B., & Smith, N. A. (2012). Censorship and deletion practices in Chinese social media. First Monday, 17(3), 5. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v17i3.3943

- Castells, M. (2008). The new public sphere: Global civil society, communication networks and global governance. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207311877

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Lindberg, S.I., Skaaning, S-E., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, S., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Knutsen, C.H., Krusell, J., Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K.L., McMann, K., Mechkova Olin, M., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., Pernes, J., Petrarca, C.S., von Römer, J., Saxer, L., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Staton, J., Stepanova, N., & Wilson, S. (2017). V-Dem [country-year/country-Date] dataset v7. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Available at https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data-version-10/

- Deibert, R. (2015). Authoritarianism goes global: Cyberspace under Siege. Journal of Democracy, 26(3), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0051

- Deibert, R. (2019). The Road to digital Unfreedom: Three Painful Truths about social media. Journal of Democracy, 30(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0002

- Deibert, R., Palfrey, J., Rohozinski, R., & Zittrain, J. (2012). Access contested: Security, identity and resistance in Asian cyberspace. The MIT Press.

- Freedom House. (2017). Freedom on the Net 2017. Available at https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedomnet-2017

- Freedom House. (2018). Freedom in the world. Available at https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world

- Freedom House. (2019). Freedom on the Net 2019 China Report. Available at https://freedomhouse.org/country/china/freedom-net/2019

- Friedrich, C. J., & Brzezinski, Z. (1965). Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press.

- Funston, J. (2018). Malaysia's 14th general election (GE14) – The contest for the Malay Electorate. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 37(3), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341803700304

- Gainous, J., Wagner, K. M., & Gray, T. (2016). Internet freedom and social media effects: Democracy and citizen attitudes in Latin America. Online Information Review, 40(5), 712–738. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2015-0351

- Gainous, J., Wagner, K. M., & Ziegler, C. E. (2018). Digital media and political opposition in authoritarian systems: Russia’s 2011 and 2016 Duma elections. Democratization, 25(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1315566

- Geddes, B., & Zaller, J. (1989). Sources of popular support for authoritarian regimes. American Journal of Political Science, 33(2), 319–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111150

- Gerring, J. (2007). Is there a (Viable) crucial-case method? Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006290784

- Gerschewski, J. (2018). Legitimacy in autocracies: Oxymoron or essential feature? Perspectives on Politics, 16(3), 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717002183

- Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R., Haschke, P., & Arnon, D. (2016). The political terror scale 1976-2015. Available at http://www.politicalterrorscale.org

- Gunitsky, S. (2015). Corrupting the cyber-commons: Social media as a tool of autocratic stability. Perspectives on Politics, 13(1), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714003120

- Hobbs, W. R., & Roberts, M. E. (2018). How sudden censorship can increase access to information. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 621–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000084

- Hopkins, J. (2014). Cybertroopers and tea parties: Government use of the internet in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Communication, 24(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2013.851721

- Howard, P. N., Agarwal, S. D., & Hussain, M. M. (2011). When do states disconnect their digital networks? Regime responses to their political uses of social media. The Communication Review, 14(3), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2011.597254

- Human Rights Watch. 2016. Deepening the culture of fear: The criminalization of peaceful expression in Malaysia.

- Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., & Puranen, B., et al. (eds.). (2014). World values survey: Round six – country-pooled Datafile 2010-2014. Madrid: JD Systems Institute

- ITU Statistics. (2018). Available at http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

- Kendzior, S. (2012). Digital freedom of expression in Uzbekistan: An example of social Controland censorship in the 21st Century. New America Foundation.

- Lei, Y.-W. (2011). The political consequences of the rise of the internet: political beliefs and practices of Chinese Netizens. Political Communication, 28(3), 291–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2011.572449

- Lei, Y.-W. (2018). The Contentious public sphere: Law, media & authoritarian rule in China. Princeton University Press.

- Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

- Link, P., & Qiang, X. (2013). China at the Tipping point? From “fart people” to citizens. Journal of Democracy, 24(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2013.0014

- MacKinnon, R. (2012). Consent of the networked: The worldwide struggle for internet freedom. Basic Books.

- Marczak, B. Guarnieri, C., Marquis-Boire, M., & Scott-Railton, J. (2014). Mapping hacking team’s “untraceable” spyware. Available at https://citizenlab.ca/2014/02/mapping-hacking-teams-untraceable-spyware/

- Miner, L. (2015). The unintended consequences of internet diffusion: Evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Public Economics, 132, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.10.002

- Morozov, E. (2011). The net delusion: The dark side of internet freedom. Public Affairs.

- Navarra, G. (2019). The networked citizen: Power, politics and resistance in the internet Age. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nisbet, E. C., Stoycheff, E., & Pearce, K. E. (2012). Internet use and democratic demands: A multinational multilevel model of internet use and citizen attitudes about democracy. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01627.x

- Open Net Initiative. (2017). ONI country reports. Available at https://opennet.net/

- Ottaway, M. (2003). Democracy challenged: The rise of semi-authoritarianism. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Qiang, X. (2011). The battle for the Chinese internet. Journal of Democracy, 22(2), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2011.0020

- Reuter, O. J., & Szakonyi, D. (2015). Online social media and political awareness in authoritarian regimes. British Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000203

- Rivetti, P., & Cavatorta, F. (2017). Functions of political trust in authoritarian settings. In S. Zmerli, & T. W. G. van der Meer (Eds.), Handbook on political trust (pp. 53–68). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Roberts, M. E. (2018). Censored: distraction and diversion inside China's great firewall. Princeton University Press.

- Robertson, G. B. (2017). Political orientation, information and perceptions of election fraud: Evidence from Russia. British Journal of Political Science, 47(3), 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000356

- Schedler, A. (2006). Electoral authoritarianism: The dynamics of unfree competition. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Stoycheff, E., & Nisbet, E. C. (2014). What’s the Bandwith for democracy? Deconstructing internet penetration and citizen attitudes about governance. Political Communication, 31(4), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.852641

- Tannenberg, M. (2017). The autocratic trust bias: Politically sensitive survey items and self-censorship. Working Paper. Series (49). The Varieties of Democracy Institute.

- Tapsell, R. (2018). The smartphone as the “weapon of the weak”: Assessing the role of communication technologies in Malaysia’s regime change. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 37(3), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341803700302

- Transparency International. (2018). Corruption perceptions index. Available at https://www.transparency.org/research/cpi/overview

- Wagner, K. M., & Gainous, J. (2013). Digital uprising: The internet revolution in the Middle East. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 10(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2013.778802

- Weidmann, N. B., & Rød, E. G. (2015). Empowering activists or autocrats? The internet in authoritarian regimes. Journal of Peace Research, 52(3), 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343314555782

- Weidmann, N. B., & Rød, E. G. (2019). The internet and political protest in autocracies. Oxford University Press.

- World Bank, World Development Indicators (2018). Available at http://data.worldbank.org/topic

- Xiang, J., & Hmielovski, J. D. (2017). Alternative views and eroding support: The conditional indirect effects of foreign media and internet use on regime support in China. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 29(3), 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw006

- Yang, G. (2009). The power of the internet in China: citizen activism online. Columbia University Press.

- Yangyue, L. (2014). Controlling cyberspace in Malaysia: motivations and constraints. Asian Survey, 54(4), 801–823. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2014.54.4.801

- You, Y., & Wang, Z. (2020). The internet, political trust, and regime types: A cross-national and multilevel analysis. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 21(2), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109919000203