ABSTRACT

This article analyses the organisational development of political parties in new democracies. In particular, focusing on Korean cases, it extends the existing discussions over party organisation into Asian democracies by examining the ways of overcoming the traditions of clientelism. Employing a dimensional approach, the evaluation relies on three core characteristics of party organisation by utilising a novel source of the official data of party organisation in Korea and a data of the Comparative Manifesto Project. Covering the long-term variations on organisational development, 1992–2018, it finds that Korean parties have experienced the waning power of the Party Central Office and the weakening ties with civil society. Despite these characteristics of development of a cartel-party type organisation, analysis does not confirm the expected of convergence of programmatic appeals between parties. These mixed findings lead to the conclusion that Korean parties have developed toward not a catch-all organisation, but a loosely cartelised organisation.

1. Introduction

How do political parties in new democracies develop their organisations in the process of democratic reform? Over 30 years after the third wave of democratisation (Huntington, Citation1991), much of the literature on political parties in new democracies has found that because of the clientelistic relationships between parties and voters with various origins or degrees, political parties are relatively weak and suffer from a lack of formal organisational faces (Ágh, Citation1993; Hellmann, Citation2011a; Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Citation2007; Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002; Steinberg & Shin, Citation2006; Tomsa & Ufen, Citation2015). Another and equally interesting finding is that to the extent that a certain type of party organisation has successfully developed, the catch-all type is dominant, as evidenced in studies of political parties in central and eastern post-communist countries (Kopecký, Citation1995; Poguntke et al., Citation2016) and new democracies in Asia including South Korea (Hellmann, Citation2011b; Vincent, Citation2017), Taiwan (Clark & Tan, Citation2012), and Thailand (Hicken, Citation2006). These two findings together may suggest a fairly clear historical path of party organisational development in new democracies and have substantial implications for the study of political parties and democracies in those countries. In addition, the development pattern seems to be consistent with Kirchheimer’s (Citation1966) theoretical argument of homogenising trends in party organisational development by which the success of one type of party organisation coerces other parties to imitate it.

However, empirical evidence does not always confirm the unidirectional development of party organisation in new democracies. For instance, the convergence of programmatic appeals among political parties in Taiwan and South Korea (hereafter Korea) is not a stable characteristic, but parties frequently polarise away from one another depending on electoral contexts (Clark & Tan, Citation2012; Han, Citation2017; Moon, Citation2016). In addition, given the traditional clientelistic relationship between parties and voters, the political market environments in which Asian political parties compete do not perfectly match those in which Western catch-all parties emerged. Some studies of political parties in Asia, in this regard, have relied on alternative categorizations conceptually more apt to the analysis of non-Western parties, including the typologies suggested by Kitschelt (Citation2000) and Gunther and Diamond (Citation2001). While the alternative typology may provide a promising basis to study party types across the world, it weakens comparability at the same time by treating unequally various features of party organisation.

Moreover, the overemphasis on specific features of party organisation might often produce a biased identification of the type of Asian party organisation. This is particularly caused by a lack of data resulting from both the instability of party organisations and parties’ indifference towards archiving their practices and activities. Under these conditions, existing literature shows a tendency to focus only on the electoral contexts over a short period (Chambers, Citation2005; Clark & Tan, Citation2012; Hellmann, Citation2011b; Vincent, Citation2017). Failing to cover the long-term organisational development in the process of democratic reforms, the literature is thus more likely to be exposed to selection bias and the omitted variable problem by ignoring parties’ adaptation strategies to reforms. Thus, we are not yet sure how effectively the dominant type of party organisation expected from exiting literature has addressed the blame laid at the feet of parties for being the ‘weakest link’ in the democratisation process (Carother, Citation2006).

Due to these weaknesses in studies of party organisation in new democracies, unresolved questions remain, including whether the development of a catch-all type party organisation in new democracies is an equilibrium path in the process of democratisation and whether parties with such organisation play an inevitable role for any degree of success in democratisation (Schattschneider, Citation1942; Stokes, Citation1999). This article addresses these theoretical puzzles by re-examining the development of party organisational type in a new democracies under the condition that there have been democratic reforms aimed at redressing traditional clientelistic relationships between parties and voters. In so doing, this article first takes the dimensional approach to party organisation, recently suggested by Scarrow et al. (Citation2017), as a starting point. As an alternative framework for a comparative study of party organisation, this approach helps us examine the diverse and often changing combination of parties’ organisational features in three dimensions: structure, resources, and representative strategies (Scarrow et al., Citation2017, p. 316). It is, in this regard, particularly conducive in showing the long-term variation of organisational development through democratic reforms.

In its application, this article chooses the two main political parties in Korea as cases for studying party organisation beyond clientelism. In particular, for analytic simplicity, this article applies the concept of ‘party family’ to study party organisation from a long-term perspective,Footnote1 and forms two groups of parties, denoted here as the ‘Democratic Party’ and the ‘Conservative Party’. From a methodological perspective, the case of Korean parties provides a perfect experimental setting for observing how party organisations develop beyond clientelism in new democracies in two respects. First, as Korea has experienced two remarkable party related reforms with 15 years of time lag, specifically aiming at developing a new political culture by stamping out the old money politics and clientelistic relationship between parties and voters, political parties in Korea are good cases to examine the long-term adaptation of party organisation to the institutional reforms.

Second and more importantly, the focus on Korean parties is warranted due to the shortage of party information in new democracies. That is, the Korean government has accumulated information on party activities, financial records, and membership and publicly released this data since 2004. Some information from before 2004 is missing and collected inconsistently. But, information from 1998 and some data from 1992, which has been collected by a government agency, the National Election Commission (NEC), can be easily accessed. Although a few scholars have already partly utilised these documents (Kim, Citation2015; Kwak, Citation2003), this article is the first attempt to collect all available information relevant to party organisation during the period of 1992–2016 from the NEC documents and systematically use it to evaluate party organisation types. In terms that that institutional reforms can remarkably constrain the possible paths of long-term organisational development of political parties in new democracies (March & Olsen, Citation1983), the usage of long-term data makes it possible to cover both the diverse impacts of institutional reforms and parties’ strategic responses to them. Moreover, the analysis of this novel Korean data is supplemented by expert survey data collected by the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) (Volkens et al., Citation2019). Analysing both data sets together allows us to check the cross validation of the evaluation on the organisational development of Korean political parties.

This article empirically shows, after reviewing the possible paths of organisational development that may emerge following the institutional reforms to end the clientelistic relationship between parties and voters in Korea, that the long-term evidence points towards Korean parties developing ‘loosely cartelised parties’. This identification highlights the weak linkage between parties and voters, heavy reliance on state subventions, and the waning power of the party centre on the one hand, and the lack of strong evidence for a power shift between the Party Central Office (PCO) and the Party in Public Office (PPO), using the terms suggested by Katz and Mair (Citation1993), and the low degree of programmatic assimilation on the other.

This article thus provides three key contributions to the literature. First, the analysis of Korean parties makes the role of Korean parties in contemporary Korean democracy much clearer. The finding here indicates that political parties in Korea are still in struggling for their very survival and have yet to contribute effectively to the newly established democracy in Korea. Second, from a more general perspective, it provides evidence that rather than unidirectional development, political parties in new democracies have multiple paths they may choose as they adapt their organisations to reform measures in the process of democratisation. Finally, the collection of novel Korean data through this analysis will be a good resource for further comparative research on party politics or party organisation.

This article is organised as follows. It first begins with discussions on theoretical frameworks for evaluating party organisational development. Next, it describes how institutional reforms undertaken in Korea over the last 20 years might redress the clientelistic traditions and consider the hypothetical organisational development expected from the reforms. This is followed by an empirical analysis of the evolution of party organisation in Korea. Finally, it summarises the findings and presents several implications for future development of Korean democacy.

2. A minimalist framework for the evaluation of party organization

Theories of political parties have explained the emergence and development of political parties from many different perspectives. Among others, scholars have focused on social cleavages (Lipset & Rokkan, Citation1967), political contexts of electoral competitions (Downs, Citation1957; Sartori, Citation1976), and certain institutional settings (Duverger, Citation1954; Panebianco, Citation1988). However, when it comes to political parties in new democracies, it may be particularly necessary to consider institutional settings since democratisation itself is closely related to rule change. Indeed, many studies of Asian political parties argue the importance of institutional reforms as they point out that collusive and clientelistic traditions are the main obstacles to any development of party organisation (Chambers, Citation2005; Choi, Citation2012; Hellmann, Citation2011b; Park, Citation2008; Stockton, Citation1998; Tomsa & Ufen, Citation2015).

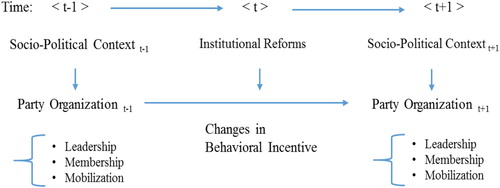

In line with the emphasis on institutional settings, this article suggests a theoretical framework outlining the relationship between institutional reforms and the organisational change of political parties. According to this framework in , the development of party organisation in time t + 1 is a function of the changes in behavioural incentives of political parties which develop from the institutional reforms redressing the old socio-political context in time t − 1. In particular, denoted as a ‘minimalist approach’, it focuses on three core components extracted from each dimension of party organisation: leadership, membership, and mobilisation.

The strength of this approach can be found in several respects. First, theoretically, the three components capture the core aspects of traditional definitions of political party. According to Weber (Citation1978, p. 284), the two main characteristics of parties are voluntary membership and the goal of its activities which is to secure power within an organisation to realise certain objective policies. The latter is mainly contested through the power struggle for leadership. Katz and Mair (Citation1993)’s discussion on the power balance between PCO and PPO can be understood from this perspective. But, for the former characteristic, existing literature has further specified it into two different dimensions. One dimension concerns the number of party members, declining pattern of which is well documented (e.g. Dalton & Wattenberg, Citation2009). The other is related to parties’ programmatic appeals or involvement in public activities in mobilising members (e.g. Kirchheimer, Citation1966; Panebianco, Citation1988). The three components thus cover the theoretical development of parties’ defining characteristics.

Second, the three components are selected from a theoretical understanding of party organisation, particularly disentangling party organisation into three dimensions consisting of structure, resources, and representative strategies. Recently introduced as an alternative framework for a comparative study of party organisation (Scarrow et al., Citation2017, p. 316), this dimensional approach helps us to avoid the over-identification of a certain ideal type of party organisation in case there are diverse and changing combinations of parties’ organisational features. In this regard, this approach particularly redresses the weakness of existing literature on political parties in Asian countries such that the type of party organisation in the literature is often identified by highly restricted attention to either party membership or party programmes over a short period of time (Chambers, Citation2005; Clark & Tan, Citation2012; Hellmann, Citation2011b; Vincent, Citation2017). Thus, this approach helps us avoid producing a biased identification from the restricted attention to specific parts of party organisation.

Related to the second, the third advantage of this approach is to test the expectation of the potential equilibrium path of organisational development under the condition that there is no data comprehensively covering all aspects of party organisation. While many scholars, including Janda (Citation1980), Katz and Mair (Citation1995), and Poguntke et al. (Citation2016), have made significant efforts to assemble data on party organisation, the lack of data is still prevalent in studies of Asian political parties. This may be partly due to political parties’ inability or unwillingness to archive data about their practices or organisational characteristics (Scarrow et al., Citation2017). But more generally, the instability of party organisations in those countries is a major obstacle preventing the accumulation of data. In this regard, it is practically impossible to take a more comprehensive approach and examine as many empirical indicators of party organisation as possible. Therefore, given the daunting challenge posed by insufficient data, the minimalist approach can help us to develop a better understanding of at least the core aspects of party organisation in new democracies and pave the way for further comparative research.

In the following section, after briefly introducing two major institutional reforms and the ways they change parties’ incentive structures on organisational development, I apply this framework to analyse the development of party organisation in Korea.

3. Institutional reforms beyond clientelism in South Korea

Considering clientelism was a main obstacle to the development of party organisation in Korea (Hellmann, Citation2011b), understanding the characteristics of clientelism and how they are related to party organisation are required. Clientelism originally refers to a personalised and reciprocal relationship between a patron and his client. Political clientelism, in this regard, can be defined as a more or less personalised, affective, and reciprocal relationship between actors, involving mutually beneficial transactions that have political ramifications beyond the immediate sphere of the dyadic relationship (Lemarchand & Legg, Citation1972). Thus, clientelistic parties, according to Kitschelt (Citation2000, p. 849), create bonds with their followers through direct, personal, and typically material side payments.

This mode of clientelism in Korea can be traced back to the relationship between political elites and large businesses under the authoritarian regime of the 1970s and 1980s (Nam, Citation1995; Park, Citation2008). Rapid industrialisation and the concentration of political power in politicians who served the regime were the social background of facilitating clientelism. Meanwhile, democratisation in 1987 had the potential to be the end of clientelism and corrupt practices in Korea. Yet, such a blueprint was not realised, however, until Chung Ju-yong, the leader of the Hyundai Conglomerate, made an unprecedented bid for the presidency in 1992 (Nam, Citation1995). Chung wanted to end the old tradition of reciprocity existing between government and big business and publicly disclosed the informal ties. Chung’s campaign was indeed a tipping point in that Korean people began to recognise the seriousness of clientelism and the necessity of urgent innovative measures to redress the problem.

But, clientelism in Korea was not significantly addressed at that time, and no one even dared to say that it had completely disappeared. The reasons can be found from two other aspects of Korean clientelism. One is the political influence of the ‘three Kims’.Footnote2 The ‘three Kims’ are three strongly influential political figures all with the surname ‘Kim’. As they had respective strongholds of public support in different regions of Korea, they had significant influence in Korean politics during the period of democratisation. In addition, concerning the parties’ clientelistic relationship with voters, their political performance was not very helpful weakening it because they financially supported factional politics sustained by clientelistic networks with the electorate (Park, Citation1994, Citation2008). To that extent, the early institutional reforms against the parties’ clientelistic relationships with voters were less effective and more likely to have only gradual and slow effects.

The other noticeable social phenomenon preserving clientelism is ‘regionalism’ in Korea.Footnote3 Deeply rooted in Korean society, it mainly refers to the public support for political leaders according to either the region of birth or residence (Kang, Citation2003; Moon, Citation2005). The fundamental basis of this type of regionalism is the strong belief of regional voters that the leader they choose will solve the problem of unbalanced industrial development between regions and make their regions more prosperous. To the extent that this regionalism establishes a reciprocity between parties and the public based on the materialistic rewards bestowed to the region, not persons, it is functionally equivalent to group-based clientelism. Thus, as far as regionalism in Korea persists, political parties, despite the strong demands for organisational renovation posed by the institutional informs, might have an incentive to rely on traditional local networks.

Given these characteristics of clientelism in Korea, two, among a series of institutional reforms conducted since democratisation in 1987, are markedly important for the renovation of party organisation. The first concerns unfair political competitions and opaque party finance. Since clientelism under the authoritarian regime relatively favoured the governing party over the opposition, political parties found it easy to agree that the resource privilege enjoyed by the governing party under the authoritarian regime had to be abolished quickly (Kim, Citation2001, pp. 11–13). This is evident in that one of the reformative measures taken just after democratisation was the revision of the ‘Political Funds Act’ in 1989. Although the revision had many purposes for political reform in Korea, one of them was to ‘fairly distribute political funds between parties and help deepen balanced development’.Footnote4 As a consequence, it stipulated the budgetary basis of state subsidies to political parties, which was not formalised in the previous version of the Act.Footnote5

The second notable institutional reform to correct the parties’ clientelistic relationship with voters in Korea was to revise the ‘Political Parties Act’ in 2004. In particular, the revision focuses on the articles concerning the parties’ local branches, a basic element of party organisation (Duverger, Citation1954), and the number of the salaried party staff members working for the PCO. From a practical perspective, the revision was considered to break the inefficient, high-cost structure of party politics in Korea. But a more fundamental reason was, described in the draft of the revision in 2004, ‘to create an advanced political culture by fostering new political soil’.Footnote6 That is, the reform aimed to renovate parties’ organisational structures by redressing the traditional clientelistic relationships between parties and the public. Indeed, as the 2004 revision legally banned local branches of political parties, the two major parties had to abolish on average about 230 local branches which were considered to be little more than personal support organisations for district representatives, staffed by friends and relatives (Hellmann, Citation2011b; Kim, Citation2015). In addition, following the regulation that the number of salaried party staff members working for the PCO shall not exceed 150 in the 2000 revision and 100 in the 2004 revision, almost 40 per cent of those who previously worked for the PCO lost their jobs.Footnote7 Thus, the two reforms provided an opportunity, or pressure, for political parties in Korea, pushing them to devise strategies to guide their organisational development away from old clientelistic traditions.

4. Hypothetical organizational development after reforms

The purposes of institutional reforms concerning the party finance in 1989 and the parties’ local branches in 2004 were fairly broad in that they aimed to restructure interparty competitions and redress the local clientelistic networks of political parties. To assess whether or how the organisational development of political parties in Korea has been actually affected by these reforms or how political parties have responded to them over time, this article applies a dimensional approach and focuses on the three core components of party organisation – internal power shifts, the number of party members, and voter mobilisation programmes – over two different time periods: the periods before and after the 2004 institutional reform.

First, regarding internal power shifts, the two institutional reforms might not have a consistent impact on the distribution of power between the PCO and the PPO. According to Katz and Mair (Citation1993), the introduction of substantial state subsidies to political parties by the 1989 reform and the subsequent revisions of it may positively redress a particular balance within the party or even simply marginalise the PCO. But, this expectation might not be properly realised during the early periods of the reform because of the materialistic privilege enjoyed by the ‘three Kims’. As large businessmen sought to buy their high chance of winning the presidency (Park, Citation2008), party resources were commonly concentrated in the hands of the ‘three Kims’ and allowed them to successfully mobilise the factional leaders of their party without significantly relying on the state subsidies. Thus, it might be only after the ‘three Kims’ lost their influence that we observe any change in the balance of power between the PCO and the PPO. Indeed, Roh Moon-hyun’s struggle to be the candidate of the ‘Millenium Democratic Party’ for the 2002 presidential election was the first severe internal conflict between the old and the new generation of faction leaders within a Democratic Party at that time, occurring just before Kim Dae-jung’s retirement. Thus, if we regard this internal power struggle between faction leaders as an evidence of the potential for power shifts, the early reform on party finance might have only a delayed impact.

In addition, the 2004 reform of abolishing local branches might distort the potential development of a power shift within a party. As the reform is expected to weaken the traditional local clientelistic networks, it definitely dissolves the relative dominance of several faction leaders and promotes the redistribution of power within a party. Nevertheless, this decentralising effect does not necessarily benefit the members of National Assembly. Instead, active debates over how to respond to the reform often produce requests for the re-establishment of the local branches and the strengthening of the role of the PCO to unify the party (e.g. Lee, Citation2005, p. 109). In this regard, while it seems to be fairly plausible to assume that the two reforms might weaken the power of the PCO to some extent, it is less clear whether the PPO might gain relatively more power than the PCO in the years since democratisation.

Second, regarding the number of party members, it is less clear how parties’ incentives to recruit more members may vary following the institutional reforms. Theoretically, state subventions are, as Katz and Mair (Citation2009, p. 764) argue, likely to reduce parties’ need or desire to provide a linkage to society, producing a weak membership structure. However, the situation concerning the recruitment of party members becomes much more complicated with the 2004 reform of abolishing local branches. As parties lose their traditional clientelistic supporters via the reform, one of the urgent tasks of parties would be to find an alternative way of replacing the old relationship with local voters if they do not want to irreparably lose their previous connections to and support from voters. Meanwhile, considering that traditional regionalism has not completely disappeared despite the dissolution of the formal local channels of parties, parties may have incentives to use informal networks to sustain regionalism without cultivating new recruitment strategies. In this regard, the expectation for how the membership structure of party organisation will evolve following the reform is not clear. Even though we focus on parties’ adaptation strategies to the institutional reforms, we could expect multiple possible changes in the number of party members.

Third, how programmatic appeals change might also depend on parties’ adaptation strategies. However, unlike the other two components of party organisation, there have been two empirical observations allowing for a more confident hypothesis that party programmes are less likely to converge to the median. One of them is the persistent influence of regionalism in Korean elections (Choi & Cho, Citation2005), which makes parties less likely to take the risk of losing the support of regional voters by campaigning on party programmes which do not represent distinct regional interests. The 1989 reform of party finance in this respect facilitates this incentive by stabilising party resources. The 2004 reform abolishing local branches is also more likely to make local party members care about the weakening connection to local voters, and thus in turn hamper the development of programmes focusing on median voters. The other observation is a drastically aggressive electoral strategy that a dominant party confident in winning elections adopts at times. That is, the two major parties in Korea often provide manifestoes crossing over into the ideological orientations of competing parties when they assume they will win the election. The most prominent example of this would be the 2004 election for the National Assembly when the Uri party, a Democratic Party at that time, successfully mobilised a majority of voters by promising to complement the existing welfare policies with measures of market liberalisation (Kang, Citation2009). This was a rather unexpected policy stance for the Uri party since it has been historically considered one of the leftist parties of Korea. While this sole move by the dominant party tends to minimise the differences in the two major parties’ programmes, that does not necessarily mean they will converge to the median. Existing Korean literature also does not support the notion that the convergence of programmatic appeals is common in Korean elections (Choi & Cho, Citation2005; Kang, Citation2003; Moon, Citation2016),

Therefore, while the institutional reforms in Korea address the problems of clientelistic relationship between parties and voters, they may not chart a course for party organisational development, but pose multiple paths over different dimensions of party organisation. In this regard, only through an empirical analysis with a long-term data can we understand how parties have actually developed their organisations as they respond to the democratic reforms.

5. Development of ‘loosely cartelized parties’ in South Korea

5.1. Data and operationalisation

This article utilises two different sources of data. First, for the analysis of leadership and membership structures, the information on the six indicators at the top in has been collected from the ‘Annual Summary Report of Party Activity and Finance’ published by the Korean NEC.Footnote8 The structure of the documents is highly consistent after first being opened to the public in 2004. Although records have been kept by the NEC since 1992, some records before 2004 are missing and incomplete. Thus, presents the best available data relevant to the indicators.

Table 1. Summary statistics and descriptions on main indicators, (year).

Specifically, for the analysis of internal power shifts, this article focuses on two empirical indicators commonly used in the existing literature: the number of salaried party staff members at the PCO and the number of party executives and candidates selected through competitive elections (e.g. Bardi et al., Citation2017; Katz & Mair, Citation2009; Van Biezen, Citation2003). If there has been a power shift within a party, we expect the number of salaried staff members at the PCO to be reduced, and competitive elections to be used for the selection of party executives and candidates more frequently than the appointment by party leaders.

At first glance, does not confirm these expectations. Among the total number of salaried staff members, about 54 per cent of staff members on average work for the PCO in both parties, which implies the PCO still holds strong power over party leadership. The number of party executives and candidates selected by competitive elections also tells a similar story. On average only about 30 per cent of them are selected by competitive elections, leaving the remaining majority selected via appointment by party leaders, or approval by party convention. However, this picture at the aggregate level is not a perfect reflection of the long-term trend. In the following analysis, we examine it in more detail

The other four indicators measure party membership structure: the number of party members, total annual revenue, membership fees, and state subsidies. While most existing literature mainly focuses on only party membership data under the assumption of long-term maintenance of membership status, Korean party members often do not remain in good standing due to the frequent change of party labels or organisations. To that extent, the variation in the total amount of membership fees would be a more valid measure of voluntary membership by showing whether the members actually contribute to the party despite organisational changes. With these indicators, the main expectation is that if party organisation has become cartelised over time, the actual contribution by members, measured by the ratio of membership fees to total annual revenue, will be decreased. While the comparison of average ratios between membership fees and state subsidies in shows the relatively higher proportion of state subsides than membership fees, whether this difference survives over time will be tested in the next section.

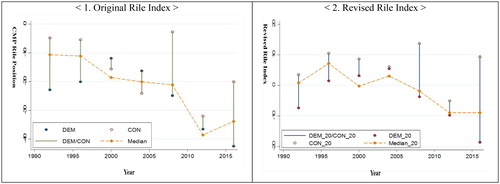

The second main source of data is the expert survey data collected by the CMP (Volkens et al., Citation2019). Using the Rile index which measures the Right/Left position of political parties provided by the CMP, parties’ mobilisation strategies can be analysed between 1992 and 2016. The merit of the Rile index is, in spite of the debates over the coding scheme (Gemenis, Citation2013), that it is easy to calculate with high internal validity. But, since it was originally developed for Western European countries, some of the defining components of the index might not be applicable to non-Western countries (Franzmann & Kaiser, Citation2006). In , the ideological positions of the Conservative Party based on the original Rile index magnify this doubt since the Conservative Party often takes more left positions than the Democratic Party. While this unexpected ideological locations of the Conservative Party might reflect the party’s distinct characteristics (Han, Citation2012), a more plausible guess would be that some of the issues used to differentiate the Right/Left ideological position by Rile Index might not be appropriate in the context of Korean politics. In this regard, it should be noted that studies which seek to measure ideological positions in Korea argue that Korean society is more likely to be ideologically divided along some political issues rather the economic or social issues (Han, Citation2017).

In line with this argument, this article proposes a slightly revised version of the Rile index. To calculate it, this article drops six components of the original Rile index. Three of them, ‘protectionism: positive’, ‘welfare state expansion’, and ‘education expansion’ originally measure the ideologically left orientation, and the other three, ‘protectionism: negative’, ‘welfare state limitation’, and ‘civic mindedness: positive’ represent the right orientation. Although the revised Index shows that the Conservative Party has a much weaker orientation toward leftist appeals compared to the original Index, the periodical trend based on maximum and minimum values is fairly consistent and satisfies the construct validity. Thus, this article, for a robustness check, compares outcomes from the original Rile index with the revised one.

5.2. Empirical results

5.2.1. Leadership structure: waning PCO vs. steady PPO

The two empirical measures for the power of the PCO confirm the institutional reforms are more likely to weaken the power of the PCO among Korean parties. First, shows that measured by the percentage of the salaried party staff members at the PCO, the power of the PCO has weakened over time. If we use the record of 2004 as a baseline for comparison, we find the high ratios of staff members at the PCO observed before the 2004 reform have been decreasing over time. The only minor exception was the Democratic Party in 2016–2018, showing a 0.2 per cent increase compared to the previous period. While the high records in 2002–2003 represent the concentration of power in the PCO, they quickly decreased after the reforms and found an equilibrium at a nearly equal 50–50 split of party staff members between the PCO and the provincial offices.

Table 2. The salaried party staff members*.

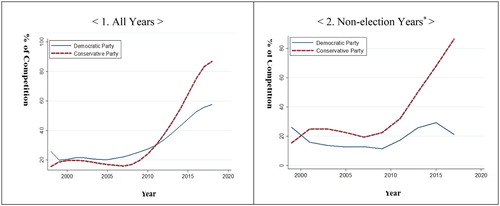

Second, the weakening power of the PCO is confirmed again by the analysis of parties’ internal decision-making over how to choose their executives and candidates. illustrates the LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing), which is the line of best fit to a time plot of the annual ratio of those selected by competitive elections from 1998 to 2018. Considering that parties use three different methods for selection, the general increasing pattern in (a) shows that Korean parties have reduced their reliance on appointment by party leader or party convention, which implies the PCO’s power is decreasing. Contrary to the situation in the early 2000s, this trend began when the Millennium Democratic Party drew huge public attention by holding a primary election for the 2002 presidential election and thus greatly influenced the existing power balance at that time (Park, Citation2016, p. 77). (b), which controls for election years and thus addresses the suspicion that the increasing pattern might result from the usage of primary elections of candidates for the National or Local Assembly, also shows a similar pattern. That is, even when limiting our attention to party executives, we still find that party leaders’ power to appoint executives has decreased over time.

Figure 2. Ratio of executives and candidates selected by competitive elections.

Notes: *For the party executives selected by competitive elections only for non-election years, I drop the data of the National and Local election years, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2018. Data Source: Original source of data is the annual reports of party activities and finance, 1998-2018, published by the National Election Commission of Korea.

Another interesting point in is that the significant change in the power of the PCO occurs after 2010, not beginning in the mid 2000s. Two things can be pointed out to make sense of this development. First, it should be noted that if the internal power struggle within parties after the retirement of the ‘three Kims’ boiled down to the concentration of power in the PCO, the pattern should have been a decreasing one, which means more party executives and candidates were appointed by leaders, not by competitive elections. Thus, the seemingly stable years between 2004 and 2010 do not exactly reflect the preservation of the concentration of power. Second, if we examine the actual annual data, the ratio of party executives and candidates selected by competitive elections before 2009 shows a fluctuation over and below the average percentages before 2002, which were 17.7 and 19.5 per cent for the Democratic Party and the Conservative Party respectively. Thus, although the ratio before 2009 does not show a clear pattern, it can be said that such a fluctuation is not an expected outcome from parties with strong central leadership.

However, this finding of waning PCO power should not be overemphasised to conclude that there has been a power shift between the PCO and the PPO. First, we do not have enough information on the number of salaried party staffs at the PPO for a direct comparison. Second, according to a recent survey, party members still think that leaders of the PCO are more influential in the decision-making processes within a party rather than the PPO.Footnote9 About 54 per cent of the survey respondents agree that the leaders of the PCO are the most influential figures in their parties while only 23 per cent see the leaders of the PPO as the most influential. Therefore, it might be more valid to say that, as a set of institutional reforms has been made to redress the problems of clientelism in Korea, political parties have seen the power of the PCO wane, although it is premature to assess that the PPO is now dominant.

5.2.2. Membership: more members without significant financial contributions

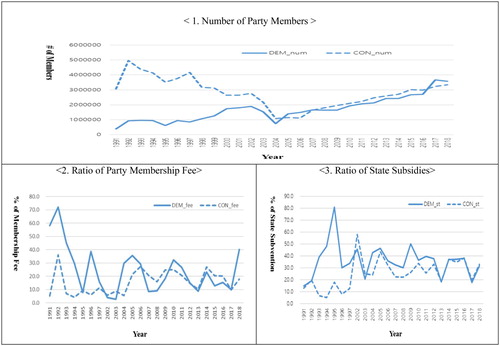

In terms of party membership, the expected impact of the institutional reforms is not completely clear. As was discussed above, the two reforms in Korea may pull organisational development in opposite directions. At first glance, (a) might show that political parties in Korea seem to be making a serious effort to find new ways of building closer relationships with civil society. For the Conservative Party, it was not until 2004 that it began to regain its lost members. Meanwhile, beginning with a relatively small number of members, the Democratic Party increased the number of members earlier than the Conservative Party, particularly just after Kim Dae-jung became president in 1997. And after a sudden reduction in membership due to the party splitting in 2004, the number has continued to grow again. Thus, the 2004 abolishment of parties’ local branches might have had a positive influence in increasing party membership. In contrast, the reform on state subventions in 1989 might have had a negligible influence on recruiting new members, implying that the ‘three Kims’ did little to renovate the party organisation at that time and relied heavily on the existing regional networks.

Figure 3. Number of party members and party finance, 1991–2018.

Data Source: Author edited, the original source is the annual reports of party activities and finance, 2004-2018, National Election Commission of Korea.

However, if we take a second look with other relevant information to party membership, the seemingly increasing number of members does not reflect reality. That is, for the new trend after 2004 to represent the parties’ sincere effort to form a new close relationship with the public, new members should actively contribute to political parties compared to the previous clientelistic parties. Both (b,c) do not confirm this expectation. Specifically, the ratio of membership fees to total annual party revenue has not improved with the enlarged membership. In (b), we observe a rather stable pattern, fluctuating between 10 and 30 per cent of annual revenue. This implies that although parties might have recruited more members, most of them are at best so-called ‘paper members’, referring to those who register for party membership but do not often pay their membership fees. Instead, political parties are shown to heavily rely on state subventions for their annual budget. According to (c), while the share from state subsides is less than that found in some European societies (Van Biezen & Kopecký, Citation2017, p. 88), both parties have relied more heavily on subventions recently compared to the early 1990s with the only exception being the 1994 Democratic Party.

Therefore, although changes in membership structure do not perfectly match the expectation of the cartel party thesis, it is clear that Korean political parties have not been successful in building an alternative way to close the gap with the public after the unravelling of the traditional clientelistic networks. Political parties in Korea indeed have heavily relied on state subsidies for their financial status without exerting serious effort to boost the number of paying members, the real voluntary members who are expected to actively participate in and contribute to parties.

5.2.3. Mobilisation strategies: non-converging parties’ programmatic appeals

In terms of parties’ mobilisation strategy, the common expectation from both the catch-all and the cartel party thesis is the convergence of programmatic appeals of political parties. For catch-all type parties, they put less emphasis on target audiences, termed as the class gardée by Kirchheimer (Citation1966, p. 190), as they seek votes from all social divisions. For the cartel parties, as they increasingly resemble one another in terms of their electorates, policies, goals, and styles, there is less and less dividing them (Katz & Mair, Citation2009, p. 757). However, the two theories do not expect exactly the same location of programmatic convergence. As the driving impetus of the convergence among catch-all parties is to win elections, the programmatic appeals are more likely to converge toward the median. Meanwhile, in order to maintain organisational survival, cartel parties do not necessarily move toward the median. Instead, where the policy assimilation among cartel parties occurs more likely depends on the electoral contexts.

Bearing this in mind, this article examines two aspects of programmatic appeals among Korean parties: programmatic convergence itself and its location. According to (a), Korean parties might show converging programmatic appeals in three elections held in 2000, 2004, and 2012. Since two of them happened in the early 2000s when the ‘three Kims’ were retiring from politics and before local branches were legally banned, the records may be understood as a new mobilisation strategy focusing on general voters rather than the traditional regional supporters.

Figure 4. Programmatic convergence to median.

Source: Comparative Manifesto Data (Volkens et at. 2019).

A few exogenous contexts might also lead us to expect the adoption of catch-all strategies. For example, the Democratic Party, when she became the governing party for two sequential elections in the late 1990s and early 2000s, preferred to conduct aggressive campaigning activities to mobilise right-leaning voters, which made her almost indifferent from the Conservative Party at those times. Moreover, social welfare expansion was considered to be a mission of the times just after economic hardships like the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. According to the CMP data, the Conservative Party’s preference for social welfare expansion under the Kim Dae-jung government (1998–2002) was 1.5 times higher than the Democratic Party, and it became stronger during the Roh Moo-hyun government (2003–2007), increasing to 2.7 times. All this evidence thus might lead some studies to argue that catch-all party organisation had become prevalent in Korea (e.g. Hellmann, Citation2011b; Vincent, Citation2017).

However, this article argues against this programmatic convergence by showing that the data does not completely support the catch-all argument. First, the convergence we observe is not a general trend. The majority of elections during the period between 1992 and 2016 indeed shows clear divisions in the parties’ programmatic appeals. If we use the standard deviation of the distribution of the Rile index of all political parties as a basic criterion of the ideological gaps between the two parties, four elections have a much wider deviation than 11.7 which is one standard deviation. Second, as is observed in (a), the convergence of party programmes does not satisfy the theoretical expectation of convergence at the median, a claim of the catch-all party thesis (Kirchheimer, Citation1966). Both parties’ electoral programmes were far from the median in 2000 and 2012 elections. Although the programmes in 2004 converged at the median, it is less reliable since the ideological positions were absurdly reversed between parties.

Third, the revised Rile index in (b), devised from the consideration of the distinct political context in Korea, does not confirm the convergence at the median either. The revised Rile index, compared to the original one, satisfies the face and construct validity of the ideological positions of the two major parties in that they are located on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum. While those identifications are consistent with the previous findings (Han, Citation2017). they are also more reliable if we consider the historical experiences of Korea. That is, as Korean society experienced the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, the competing parties for a while supported similar economic policies including privatisation of public sector businesses, huge layoffs, and weakening the labour movement, and consequently came to support ideologically more rightist positions. However, despite a similar pattern in the original index, it does not support the conclusion that there is convergence toward the median. This means that Korean parties go back and forth between representing traditional regional interests and assimilating programmatic appeals without locating at the median. In this regard, it is more valid to argue that Korean parties are more likely to be trending toward cartel-type party organisation rather than the catch-all type.

6. Conclusion

This article has shown an emerging pattern of organisational development of political parties as parties respond to democratic reforms in a new Asian Democracy, South Korea. In particular, it has empirically demonstrated with long-term data that as Korean society has tried to overcome the traditional clientelism inimical to the development of formal party organisational faces, two major Korean parties themselves also have strategically adapted to the democratic reforms and developed their organisations toward a specific type of party organisation although it has not always been in a consistent or ‘linear’ pattern.

More specifically, results from the analysis of two sources of data find that political parties in Korea are developing into ‘loosely cartelised organisations’, a pattern resulting from the changes in the three core aspects of party organisation. First, the leadership at the PCO has been weakened although it is yet too early to assess that the PPO has become dominant. Second, political parties have not replaced the close relationship with civil society they had through the traditional clientelistic networks. Rather they tend to rely more on the state subventions without seeking out greater contributions from members. Third, it is not clear whether political parties are more likely to assimilate their programmatic appeals. A few cases of programmatic convergence occurred, but they fail to form a general pattern as they do not terminate their old practice of targeting regional voters.

This finding thus suggests that Korean political parties are no longer dysfunctional, relying on the interests of local clientelistic networks independent from wider societal conflicts. However, they are still in struggling for their very survival and have yet to contribute effectively to the newly established democracy in Korea. In addition, from the institutionalist point of view suggested by Rose and Mackie (Citation1988, p. 536), the emerging pattern of party organisation can be said to be a fairly institutionalised one rather than ephemeral since it has been identified over more than two decades. Although it is still fluctuating, responding to new political contexts emerging from the waning impact of regionalism and the active social requests for political reforms, what is clear from the analysis is that the organisational development of political parties in Korea is advancing to accommodate the democratic decision-making process and moving away from traditional clientelism.

From these findings, one important implication would be that any hasty assessment of the organisational development of political parties in new democracies is profoundly flawed by overemphasising ephemeral phenomenon. For the Korean case as well, there is swaths of potential evidence directing us to conclude quickly that parties are either catch-all or cartel (Hellmann, Citation2011b; Kwak, Citation2003; Vincent, Citation2017). For example, from the limited focus on short-term variations of party organisation, we may find either the decentralised power of the PCO, strong reliance of state subsidies, or often assimilated party programmes between competing parties in Korea. However, if we reconsider additional relevant information, we may arrive at different conclusions. The weakening power of the PCO might be predestined by the existence of the powerful ‘three Kims’ in the past. The slowly waning leadership of the PCO after 2005 is not sufficient enough evidence to predict an on-going power shift within a party. Also, without studying further parties’ activities invigorating relationship with civil society, the increase of potentially ‘paper members’ cannot be accepted as an evidence of the development of new relationship between parties and voters after the traditional clientelistic relationship. Finally, as clientelistic networks have collapsed, it might be natural for parties to target more general voters and thus their programmatic appeals would converge. But, without examining how frequently and consistently this happens, we are more likely to end up with a selection bias toward a false positive finding, which rejects the true null hypothesis. All these concerns thus imply that a necessary condition for a valid assessment of changing party organisation would be a consistent pattern of organisational development over the course of several institutional reforms. Reached with these concerns in mind, the identification of the ‘loosely cartelized’ Korean parties does not support the dominant expectation of a unidirectional organisational development among political parties in new democracies, but provides evidence that there will be multiple paths political parties in new democracies can choose in the process of democratisation.

This article also contributes by enhancing the understanding of political representation in newly established democracies. Mair (Citation2009) has noticed that unlike the other types of party, cartelised parties are more likely to play the role of responsible government rather than the role of representatives of the public. As a consequence, the diminishing accountability to the national constituency of voters by mainstream parties tends to stimulate the possibility that peripheral parties constitute a conduit for popular challenges within the party system (Mair, Citation2011, p. 14). In line with this argument, the ‘loosely cartelised parties’ in Korea might echo the frequent emergence and collapse of third parties in Korea. Also, the long-term disappointment of voters due to the increasing distance between parties and voters caused by cartelisation often instigates social protests against the government (Lee, Citation2009). In this regard, the long-term development of party organisation among political parties in newly established democracies requires further investigation of the impacts of the development of a specific type of party organisation on the degree of representation as well as the development of participatory democracies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

JeongHun Han

JeongHun Han is an associate professor in the Graduate School of International Studies at Seoul National University. His research interests include institutional design, party government, political polarization, and new media politics, particularly focusing on new democracies as well as Europe. JeongHun recently edits the Oxford Handbook of South Korean Politics and published articles in international journals including European Journal of Public Policy, Korea Observer, etc.

Notes

1 The application of the ‘party family’ concept to the non-Western societies is debatable (Von Beyme, Citation1985; Ware, Citation1996). But, for analytic simplicity, this article follows the research tradition in Korean literature (see e.g. Han, Citation2017). The groupings in this study are constituted as follows: in the category of the ‘Democratic Party’ are the ‘Democratic Party (1991–1995, 2005–2007, 2008–2011, 2013–2014, 2015–)’, ‘National Congress for New Politics (1995–2000)’, ‘Millenium Democratic Party (2000–2005)’, ‘Uri Party (2004–2007 )’, ‘United Democratic Party (2007–2008)’, ‘Democratic United Party(2011–2013)’, ‘New Politics Alliance for Democracy (2014–2015) and parties included in the category of the ‘Conservative Party’ are ‘Democratic Liberal Party (1990–1995)’, ‘New Korea Party (1995–1997)’, ‘Grand National Party (1997–2012)’, ‘New Frontier Party (2012–2017)’, and ‘Liberty Korea Party (2017–)’.

2 Two of them, Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung, are liberal political leaders who led the democratisation movement and later became president. Their regional strongholds were the Southerneast Gyeongsang provinces (a.k.a.Youngnam), and the Southernwest Jeonla province(a,k.a.Honam) respectively. The other, Kim Jong-pil, led the military coup with President Park Chung-hee, but had experienced a political suppression under the succeeding authoritarian government after President Park. His regional stronghold was the Choongchung provinces.

3 Regionalism in Korea has been defined from many different perspectives. For a good summary of the debates on regionalism and voting behaviour according to it, see Choi (Citation1999), and Lee (Citation1998).

4 The text of this bill is available in the legislative archive of Korean National Assembly, https://likms.assembly.go.kr/bill/billDetail.do?billId=009127

5 See ‘Political Funds Act’, Article 17 (Law number 4186, 1989.12.31). The most recent English version is available at https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do

6 The text of this bill is available at the legislative archive of Korean National Assembly, https://likms.assembly.go.kr/bill/billDetail.do?billId=027866

7 See ‘Political Parties Act’, Article 30.2 (Law number 6269, 2000.2.16) and ‘Political Parties Act’, Article 30.2 (Law number 7190). The most recent English version is available at https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do

8 The ‘Political Parties Act’ obliges parties to report annually their number of members and the summary of annual activities (Article 35). Also, the ‘Political Funds Act’ stipulates that parties are obliged to report their annual revenue and expenditures (Article 24). Both Acts can be accessed at the following National Law Information Center, https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do.

9 See Yoon and Jung (Citation2019) for the detailed explanation of the survey data and the outcomes of analysis.

References

- Ágh, A. (1993). The comparative revolution and the transition in Central and Southern Europe. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 5(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692893005002004

- Bardi, L., Calossi, E., & Pizzimenti, E. (2017). Which face comes first? The ascendency of the party in public office. In S. E. Scarrow, P. D. Webb, & T. Poguntke (Eds.), Organizing political parties: Representation, participation and power (pp. 62–84). Oxford University Press.

- Carother, T. (2006). Confronting the weakest link: Aiding political parties in new democracies. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Chambers, P. (2005). Evolving toward what? Parties, factions and coalition behaviour in thailand today. Journal of East Asian Studies, 5(3), 495–520. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1598240800002083

- Choi, J.-j. (2012). Democracy after democratization: The Korean experience. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center.

- Choi, J. Y., & Cho, J. (2005). Jiyeokgyunyeorui byeonhwaganeungseonge daehan gyeongheomjeong gochal: je17dae gukoeuiwon seongeoeseo natanan inyeomgwa sedae gyunyeorui hyogwareul jungsimeuro [Is the regional cleavage in korea disappearing? Empirical analysis of the ideological and generational effects on the outcomes of the seventeenth national assembly election]. Hangukjeongchihakoebo [Korean Political Science Review], 39, 375–394.

- Choi, Y.-j. (1999). Hangukjiyeokjuuiwa jeongcheseongui jeongchi [Regionalism and identity politics in South Korea]. Oreum.

- Clark, C., & Tan, A. C. (2012). Political polarization in Taiwan: A growing challenge to catch-all parties? Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 41(3), 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261204100302

- Dalton, R. J., & Wattenberg, M. P. (2009). Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper and Row.

- Duverger, M. (1954). Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state. John Wiley & Sons.

- Franzmann, S., & Kaiser, A. (2006). Locating political parties in policy space: A reanalysis of party manifesto data. Party Politics, 12(2), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068806061336

- Gemenis, K. (2013). What to do (and not to do) with the comparative manifestos project data. Political Studies, 61(1_suppl), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12015

- Gunther, R., & Diamond, L. (2001). Types and functions of parties. In L. Diamond & R. Gunther (Eds.), Political parties and democracy (pp. 3–39). The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Han, J. (2012). Hangung gukoe nae ipbeopgaldeung: Bogeonbokjibunya jeongchaegeul jungsimeuro [Legislation conflicts in the Korean national assembly: Focusing on health and welfare policies]. Hangukjeongchiyeongu [Journal of Korean Politics], 22, 35–62.

- Han, J. (2017). Preferences on security issues and ideological competitions: A case of the Korean national assembly. Korea Observer – Institute of Korean Studies, 48(4), 639–668. https://doi.org/10.29152/KOIKS.2017.48.4.639

- Hellmann, O. (2011a). Parties and electoral strategy: The development of party organization in East Asia. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hellmann, O. (2011b). A historical institutionalist approach to political party organization: The case of South Korea. Government and Opposition, 46(4), 464–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01346.x

- Hicken, A. (2006). Party fabrication: Constitutional reform and the rise of thai rak thai. Journal of East Asian Studies, 6(3), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1017/S159824080000463X

- Huntington, S. P. (1991). The third wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Janda, K. (1980). Political parties: A cross-national survey. The Free Press.

- Kang, B. I. (2009). Jeongdangchegyewa bokjijeongchi: Bosu-jaujuui jeongdangchegyeeseo yeollinuridanggwa minjunodongdangui bokjijeongchireul jungsimeuro [Party system and welfare politics: Focused on the welfare politics of uri party and KDLPO under “dominant conservative-liberal party system”]. Geokgwa Jeonmang [Memory and Prospects], 20, 109–146.

- Kang, W.-t. (2003). Hangugui seongeojeongchi [Electoral politics in South Korea]. Pureungil.

- Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (1993). The evolution of party organization in Europe: The three faces of party organization. American Review of Politics, 14, 595–617.

- Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy: The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics, 1(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068895001001001

- Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (2009). The cartel party thesis: A restatement. Perspectives on Politics, 7(4), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709991782

- Kim, D. T. (2001). Hanguk Jeongdangchegyewa gukgobojogeu jedo: Moonjejemkwa hyoyulseong jegobangan [Koran political party system and governmental subsidy: Problems and solution]. Sahoekwahakyeongu [Journal of Social Science], 17, 5–27.

- Kim, J. (2015). Juyo jeongdangui jigudang jojikgwa unyeonge daehan siljeung bunseok: jigudang pyeji ijeon jipapjaryoreul jungsimeuro [How political parties organized and funded local party chapters before the enactment of the 2004 political party act]. Hangukjeongdanghakoebo [Korean Party Studies Review], 14, 5–39.

- Kirchheimer, O. (1966). The transformation of Western European party Systems. In J. LaPalombara & M. Weiner (Eds.), Political parties and political development (pp. 237–259). Yale University Press.

- Kitschelt, H. (2000). Linkages between citizens and politicians in democratic politics. Comparative Political Studies, 33(6–7), 845–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041400003300607

- Kitschelt, H., & Wilkinson, S. I. (2007). Patrons, clients, and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition. Cambridge University Press.

- Kopecký, P. (1995). Developing party organizations in East Central Europe: What type of party is likely to emerge? Party Politics, 1(4), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068895001004005

- Kwak, J. Y. (2003). The party-state Liaison in Korea: Searching for evidence of the cartelized system. Asian Perspective, 27, 109–135.

- Lee, H.-c. (2005). Jeongdanggaehyeokgwa jigudang pyeji [Reform of political parties and abolishment of local party branches]. Hangukjenogdanghakoebo [Korean Party Studies Review], 4, 91–120.

- Lee, H.-W. (2009). Political implications of candle light protests in South Korea. Korea Observer, 40, 495–526.

- Lee, N. Y. (1998). Regionalism and voting behavior in South Korea. Korea Observer, 29, 611–633.

- Lemarchand, R., & Legg, K. (1972). Political clientelism and development: A preliminary analysis. Comparative Politics, 4(2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/421508

- Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. (1967). Party systems and voter alignment: Cross national perspective. Free Press.

- Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government. MplfG Working Paper 09/0.

- Mair, P. (2011). Bini Smaghi vs. the parties: Representative government and institutional constraint. EUI Working Paper, RSCAS 2011/22.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1983). The new institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life. American Political Science Review, 78(3), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961840

- Moon, W. (2005). Decomposition of regional voting in South Korea: Ideological conflicts and regional interests. Party Politics, 11(5), 579–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068805054981

- Moon, W. (2016). Hanguk seongeogyeongjaenge isseoseo inyeom galdeungui jisokgwa byeonhwa [Continuity and change in ideological conflicts in Korean electoral competition: An analysis of the cumulative data set since the fifteenth presidential election]. Hangukjeongdanghakoebo [Korean Party Politics Review], 15, 37–60.

- Nam, C.-H. (1995). South Korea’s big business clientelism in democratic reform. Asian Survey, 35(4), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645800

- Panebianco, A. (1988). Political parties: Organisation and power. Cambridge University Press.

- Park, C. H. (2008). A comparative institutional analysis of Korean and Japanese clientelism. Asian Journal of Political Science, 16(2), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185370802203992

- Park, C. P. (2016). Gungminchamyeogyeongseonjeui jedo chaiui balsaengbaegyeonge daehan yeongu: 16–18 dae daeseonhubo gyeongseonjedo bigyo [A study of the presidential primaries rules of two major parties in South Korea, 2002–2012]. Miraejeongchiyeongu [Journal of Future Politics], 6(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.20973/jofp.2016.6.1.65

- Park, C. W. (1994). Financing political parties in South Korea: 1988–1991. In H. E. Alexander & R. Shiratori (Eds.), Comparative political finance among the democracies (pp. 173–186). Westview Press.

- Poguntke, T., Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., Allern, E. H., Aylott, N., van Biezen, I., Calossi, E., Lobo, M. C., Cross, W. P., Deschouwer, K., Enyedi, Z., Fabre, E., Farrell, D. M., Gauja, A., Pizzimenti, E., Kopecký, P., Koole, R., Müller, W. C., Kosiara-Pedersen, K., … Verge, T. (2016). Party rules, party resources, and the politics of parliamentary democracies: How parties organize in the 21st century. Party Politics, 22(6), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068816662493

- Randall, V., & Svåsand, L. (2002). Political parties and democratic consolidation in Africa. Democratization, 9(3), 30–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000266

- Rose, R., & Mackie, T. (1988). Do parties persist or fail? The big trade-off facing organizations. In K. Lawson & P. H. Merkl (Eds.), When parties fail: Emerging alternative organizations (pp. 533–558). Princeton University Press.

- Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., & Poguntke, T. (2017). Organizing political parties: Representation, participation and power. Oxford University Press.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1942). Party government. Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

- Steinberg, D. I., & Shin, M. (2006). Tensions in South Korean political parties in transition: From entourage to ideology? Asian Survey, 46(4), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2006.46.4.517

- Stockton, H. J. (1998). Democratization of the public sector: Democracy and clientelism in South Korea and Taiwan [PhD diss.]. Texas A&M University.

- Stokes, S. C. (1999). Political parties and democracy. Annual Review of Political Science, 2(1), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.243

- Tomsa, D., & Ufen, A. (2015). Party politics in Southeast Asia: Clientelism and electoral competition in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. Routledge.

- Van Biezen, I. (2003). Political parties in new democracies: Party organization in Southern and East-Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Biezen, I., & Kopecký, P. (2017). The paradox of party funding: The limited impact of state subsidies on party membership. In S. E. Scarrow, P. D. Webb, & T. Poguntke (Eds.), Organizing political parties: Representation, participation, and power (pp. 84–105). Oxford University Press.

- Vincent, S. (2017). Dominant party adaptation to the catch-all model: A comparison of former dominant parties in Japan and South Korea. East Asia, 34(3), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-017-9273-2

- Volkens, A., Krause, W., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., Regel, S., & Weßels, B. (2019). The Manifesto data collection. Manifesto project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2019a. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2019a

- Von Beyme, K. (1985). Political parties in Western democracies. Gower.

- Ware, A. (1996). Political parties and party systems. Oxford University Press.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology, Vol. 1. University of California Press.

- Yoon, J., & Jung, S. (2019). Hangugui dangwoneul malhanda [Party members in Korea]. Pureungil.