ABSTRACT

As an example of a typical right-wing populist, Jair Bolsonaro downplayed Covid-19 and rejected scientific evidence to address the pandemic. We argue that both his communication style and approach to crisis management had consequences for the behavioural patterns of his followers, which, in turn, had public health implications. Building on survey research, we demonstrate how Bolsonaro’s supporters were less likely to consider the pandemic as a key challenge for the country, less worried about getting infected and less likely to wear masks. We show that this ‘riskier’ behaviour had concrete repercussions. Even after controlling for confounders such as population density, age, education and wealth, municipalities with higher aggregate support for Bolsonaro had higher Covid-19 infection rates in 2020 and saw more people dying from the virus.

Introduction

‘In my opinion, it is more of a fantasy, this question of the Coronavirus, which it not actually the big deal the media makes out and propagates around the world.’

President Bolsonaro, 10 March 2020Footnote1

In this article, we demonstrate the behavioural consequences of a populist’s polarising behaviour and anti-science stance in the critical context of a global health crisis. In such a pandemic context, individuals’ social behaviour and adherence to sanitary measures are crucial to limit the spread of the virus. Based on the argument that people ‘follow the leader’ (Lenz, Citation2013) and that the attitudinal and communicative signals by a populist leader affects followers’ behaviour, we elaborate and empirically test two hypotheses. First, we hypothesise that followers of a populist leader are less afraid of Covid-19 and more willing to defy science-based behavioural patterns such as wearing masks. Our second hypothesis is that this lower risk-awareness of Bolsonaro’s supporters increased infection rates and death tolls in areas where the Brazilian populist leader had stronger support. We find evidence supporting the first hypothesis with the help of an original, nationally representative survey, which we put into the field in December 2020 at the height of the pandemic. We also find evidence for the second hypothesis, using municipal-level data for nearly all 5,570 Brazilian municipalities.

This article proceeds as follows: in the next section, we theoretically discuss the link between right-wing populism, polarisation and anti-science positions and formulate our hypotheses. In the third part, we discuss the data, methods, and statistical procedures. Fourth, we display and analyse the results from both our survey and aggregate-level study. Finally, we summarise the main arguments and findings of this article.

The populist leader and her/his influence on supporters

Lenz (Citation2013) illustrates that politicians influence citizens’ policy positions and policy compliance (see also Levi, Citation1988). Voters first decide to support a particular candidate and then adopt his/her policy views (Lenz, Citation2013, p. 216ff). We expect this to be particularly the case for supporters of populist leaders. The populist leader is central to populism; he/she is a polarising figure who bifurcates the world into two opposite camps: the virtuous people versus the corrupted enemies. To spread this bifurcation, he or she uses a simplistic, emotional, polarised and negative ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ rhetoric (Hawkins et al., Citation2017; Moffitt, Citation2016). These discourses strategically stimulate audiences’ antagonism towards their main objects of attack (the elite and the others) by emotionally blaming established political elites for all failure of policy. Political campaigns by populists are ‘negative’; they entice people to choose sides (i.e. in favour of the in-group) to avoid being identified with an opposing camp of ‘them’ (Hawkins & Littvay, Citation2019). This strategy can ultimately result in affective polarisation among publics, especially in contexts where the level of polarisation was already increasing when the populist came to power (Iyengar et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the populist leader can influence beliefs and behaviours of people through different means, for instance by shortening asymmetry of information and by limiting coordination problems (e.g. Dewan & Myatt, Citation2008), by establishing social norms (e.g. Acemoglu & Jackson, Citation2015) or by emotionally and symbolically transmitting messages (e.g. Antonakis et al., Citation2014; Hermalin, Citation2017). Weyland (Citation2021) illustrates that the figure of the leader is central to understanding populism. Moreover, Ferreira da Silva and De Angelis (Citation2020) argue that leader evaluations are more important for populist radical right voters than for other voters. They also trump left–right self-placement.

The populist’s crisis management, COVID-19 and affective polarisation

The Covid-19 pandemic has transformed societies around the globe, including the Brazilian society, into so-called risk societies, where ‘concerns about personal safety and health as well as collective security have risen to the top of the social and political agendas’ (Boin & ’t Hart, Citation2003, p. 546). In such a situation, ideological differences frequently wane, as citizens expect their leaders to put measures in place to save their lives. Many populists in power took the Covid-19 emergency seriously and put in place restrictive measures (Meyer, Citation2020). For example, Hungary’s Victor Orban or India’s Narendra Modi imposed extensive lockdown measures. Yet, there is another group of populists, including Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, who downplayed the crisis. They adopted a denialist response, characterised by misleading communication, the withholding of key official Covid-19 statistics, failure to initiate or coordinate lockdowns, and the firing of public health officials who did not agree with the leader. Our research is about those populists who downplayed and denied the crisis. We argue that the signals emitted by such populists – neglecting the Covid-19 disease and discouraging compliance with health guidelines – have cued their supporters’ attitudes and behaviours, which, in turn, has had broader public health consequences.

More precisely, we add to the budding literature on the effects of populist leadership on political outcomes during the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, Pevehouse (Citation2020) argues that populist leaders can pose barriers to international cooperation that are crucial to overcoming a transboundary crisis like Covid-19 because they are more likely to attenuate the informational effects of international organisations, discourage the delegation of authority, and create concerns about relative gains, domestically and internationally.Footnote3 We add a more individual lens to this literature and argue that in a polarised society such as that of Brazil when it was governed by a right-wing populist leader who adopted a denialist approach to Covid-19, polarised opinions, rather than fading away, could actually be extenuating. As a pandemic response, we would normally expect a ‘rally around the flag’ effect and a united reliance on expertise for effective crisis management (Bækgaard et al., Citation2020). Yet, in a polarised society, we would expect the combination of high polarisation and a populist denialist response to intensify societal divisions, which could foster harmful social behaviour patterns and have detrimental effects on public health. Because of the strength of the connection between the supporters of populists and their leader, we argue that following populist cues and signals puts his/her supporters’ health and lives at risk during a pandemic.

This danger mainly emanates from the incompatibility between a populist leadership style and effective crisis management on the one hand and supporters’ willingness to follow their leader on the other. First, populist leaders are unlikely to rely on scientific evidence to make sense of the crisis and they will not listen to scientific expertise for decision-making. In addition, populists are anti-system (Sartori, Citation1976) and reject all actors who represent the system, including the scientific elite. Instead, populist leaders believe that they embody the civic virtues of the masses and that they have the sovereign right to decide on their behalf (Fennema, Citation2005). They work on impulse and let their gut instincts, or the ‘common sense’, guide them (Laclau, Citation2005); this is the antithesis of consistent, predictable and moderate behaviour, much needed during times of transboundary crises.

Second, in an unfolding crisis, populists – as do other political leaders – need to take decisions in an environment of high uncertainty, imperfect knowledge and under time pressure, which would require them to engage in a multi-organizational, polycentric response network (Boin et al., Citation2016). This poses a major problem for populists who embody a top-down decision-making process. A pandemic with severe and long-term health and economic damage is a blow to populists’ self – conception, even more so because populists frequently style themselves as the saviour of the ordinary man or even as a superhero with exceptional qualities (Schneiker, Citation2020). A populist leader cannot have a crisis expose these weaknesses (Hawkins, Citation2009). Instead, in the populist mindset, the outpacing and destruction of competitors is of higher priority than strategic contingency planning (McCormick, Citation2001).

Third, effective crisis management would require the populist to narrate a persuasive story about the origins of the crisis and the government’s response to it with a view to mobilising the collective crisis management efforts of the public (Boin et al., Citation2016). This requires communication that builds a sense of ‘we’ rather than ‘me’ and brings citizens together (Platow et al., Citation2015). These qualities are incompatible with a populist leadership style. Populist leaders develop a dichotomy between ‘friends and foe’, further polarising, rather than uniting, society. They ‘express more what they dislike than what they like’ (Kitschelt & McGann, Citation1995, p. 201) and are unable to develop a coherent narrative and strategy to address the crisis. Altogether, these behavioural patterns make it likely that, rather than sound, concerted and science-based decision-making, the right-wing populist leader will likely engage in denying or belittling the crisis and further polarising society.

In our case, there are multiple examples of Bolsonaro neglecting the seriousness of the Covid-19 pandemic, refusing to adhere to scientific evidence to contain the health emergency and further polarising society (Batista Pereira & Nunes, Citation2021; Burni & Tamaki, Citation2021; Rennó et al., Citation2021). Initially, when Brazil registered the first case of Covid-19 in the city of São Paulo on 26 February 2020, Bolsonaro did not explicitly deny that Covid-19 was a worldwide problem. On a first and short nationally televised statement (on 6 March 2020), he recognised the circulation of a new virus, called for a unified and collaborative effort of health professionals and institutions, but did not display any sense of urgency. In subsequent media appearances, however, Brazil’s President began to minimise the seriousness of the disease, explicitly. Over time he maintained a consistent approach of denial (Calvo & Ventura, Citation2021). He declared that the coronavirus was a ‘fantasy’ inflated by the media,Footnote4 that there was ‘no reason to panic’, and that the disease was a ‘measly cold’. On top of such trivialising language, Bolsonaro urged that people should ‘go back to normal’Footnote5 and prioritised saving the economy.

Not only did Bolsonaro minimise the disease, but he openly attacked governors and mayors for putting lockdown measures in place and for closing some sectors of the economy, blaming them for the rising unemployment (Burni & Tamaki, Citation2021). Ignoring the recommendations of health authorities to avoid spreading the virus, Bolsonaro participated in many street demonstrations organised by his supporters. Contradicting health guidelines in place, Bolsonaro did not wear facemasks, shook hands with his supporters and ignored social-distancing measures. In particular, between March and September 2020 Bolsonaro explicitly opposed lockdown measures by some state and local governments and used decrees to re-open churches and non-essential shops.Footnote6 In addition, Bolsonaro repeatedly pushed for the use of Chloroquine to treat Covid-19 patients, despite the lack of scientific evidence about its efficacy. At of the end of 2020 Bolsonaro was continuing to downplay the disease, despite the increasing number of infections and deaths. Urging people to get back to ‘normal’ the president associated the feeling of fear and protective measures against Covid-19 to ‘queerness’.Footnote7 Bolsonaro’s denialist tone persisted and he went on to target Covid-19 vaccines after their approval for distribution. Between the approval of vaccines and the start of the vaccination campaign in January 2021, he did not engage in a national campaign promoting the Covid-19 vaccination. On the contrary, he questioned the efficacy of the vaccine and claimed, ‘no one can force anyone to take the vaccine’ (31 August 2020).Footnote8

The starting point of our analysis is that such denial of the crisis can have strong repercussions on the beliefs and behaviour of supporters in a polarised society. In a polarised society, citizens, and particularly supporters, tend to rely on leaders’ cues in order to get information about the evolving situation and to decide on how to act (Banerjee et al., Citation2020; Kearney & Levine, Citation2015). In a pandemic, such polarisation should increase the extent to which supporters are prone to believe false information (Abramowitz & Webster, Citation2016; Van Bavel & Pereira, Citation2018). Polarisation should also lead to what the literature labels an ‘informational cascade’ (Çelen et al., Citation2004); that is, individuals interpret others’ actions through their own preconceived ideas. This gives rise to ‘social confirmation bias’, a state of mind in which people incorporate ‘good news’ into their beliefs while they largely discount ‘bad news’ (Festinger, Citation1954). Such belief homogenisation emerges in the contexts where the network structure exhibits homophily (an interaction of like-minded individuals) (Golub & Jackson, Citation2010). In such a situation, individuals draw inferences from small circles of people and their trusted leaders and consider them representative and true. Anyone locked into such a mindset might fail to recognise the inherent correlation of the information they receive. As a result, the whole group may experience an informational cascade in a wrong direction and end up locked in a false belief that might be difficult to recover from (Banerjee, Citation1992; Golub & Jackson, Citation2010).

This information processing can have detrimental consequences in a crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic, even more so because an inscrutable and invisible phenomenon like a virus offers a breeding ground for conspiracy theories to flourish, especially when the political leader promotes them. Citizens constantly hear from their populist leader that the crisis is imaginary, harmless, and just not as bad as anyone makes them believe. We expect that most of the Brazilian population will not follow the President’s denialist views of the pandemic, whereas Bolsonaro’s supporters are expected to agree with his positions (see also Rennó et al., Citation2021 for a similar argument). In such a situation, populist supporters suffering from belief polarisation might not have realised or might not want to have realised the severity of the crisis. This would have had serious repercussions for their daily attitudes and behaviour vis-a-vis the pandemic.

H(1): Compared to opponents, supporters of the populist leader are more likely to downplay a pandemic such as Covid-19 and defy crisis containment measures, such as wearing masks.

H(2): Municipalities with more support for the populist leader have higher infection rates and higher death tolls than municipalities with lower support for the populist leader.

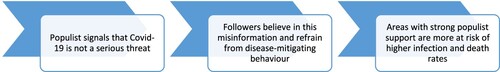

summarises our theoretical reasoning. It follows a signalling game. At the top of the game is the populist leader, in whom her/his followers put their trust. These followers are likely to act contingent on signals they receive from their leader. If he/she signals that Covid-19 is not a serious health threat, his/her followers, who put more trust in their preferred leader than scientific evidence, might believe this misinformation, and might not act with the necessary care. They might either do so because of trust in their leader or because they might want to deliberately defy science, or both. Batista Pereira and Nunes (Citation2021) show that Bolsonaro’s open neglect of the Covid-19 crisis influenced his supporters to oppose containment measures and to advocate for keeping the economy open. However, existing research has not yet, to our knowledge, assessed the impact of support for Bolsonaro on his supporters’ behaviour and on infection and death rates, respectively. According to our framework, the consequences of opposing containment measures could be dire. In areas with higher populist support, Covid-19 might spread faster and more people might die, because the limitation of the spread of the virus largely depends on the behaviour of individuals, in particular the limitation of social contacts, and the use of facemasks.

Data and methods

We conducted an original representative survey in December 2020, when Covid-19 infection and death rates were particularly high in Brazil with little signs of improvement. Our original questionnaire tapped into citizens’ electoral support patterns and their attitudes and reactions toward Covid-19 at a critical moment of the Covid-19 pandemic. To put it in the field, we collaborated with the local survey company Vox Populi, who administered our telephone survey. The survey company retrieved a representative sample of the entire Brazilian population aged 18 years and over (error + −3.5 percentage points) with a total of 2,000 participants (see in the appendix for a more detailed discussion of the sampling procedure).

To determine whether there was a difference in attitudes and behaviours between Bolsonaro and non-Bolsonaro supporters, we analysed four dependent variables from the survey: (1) respondents’ belief in science, (2) respondents’ assessment of whether or not Covid-19 is the most important topic in Brazilian politics, (3), the interviewees’ fear of catching Covid-19, and (4) the respondents’ likelihood to wear masks in a public space. The first variable, belief in science, is an 11-point scale, ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’. The second variable is a binary variable, coded 1 if the respondent thinks that Covid-19 is the most important topic that Brazil is currently facing and 0 if otherwise. The third variable is again an 11-point scale ranging from ‘not afraid at all’ of catching Covid-19 to ‘very afraid’. The final variable, wearing masks, is a five point Likert scale going from ‘always’ to ‘never’.

We measure our independent variable (support for Bolsonaro) in two ways. First, we look at the self-declared voting choice in the first round of the presidential elections of 2018, coded 1 if the respondent voted for Bolsonaro and 0 if he or she voted for another party or did not vote at all.Footnote9 918, or nearly 46 percent, of our sample respondents affirmed that they voted for Bolsonaro in the first round. This number corresponds to the 46.1 percent that actually voted for Bolsonaro in the first round of the presidential elections 2018. Second, we look at satisfaction ratings for the Brazilian president at the time we conducted the survey. This second indicator uses an 11-point scale ranging from ‘not satisfied at all’ with the president to ‘very satisfied’ with the head of the government.

To isolate the effect of the Bolsonaro vote and the satisfaction ratings with the Brazilian president on the attitudes and behaviour of Brazilian citizens, we add several control variables. The first control variable is age, which we operationalise by the actual age of the respondent, as collected in the survey. We expect older individuals to show more risk-averse behaviour, given that the virus affects the elderly more severely (Kluwe-Schiavon et al., Citation2021). Second, we control for gender (coded 0 for male respondents and 1 for female interviewees). Given that there is a rather voluminous literature in the field of gender studies, which portrays women as more cautious in life-threatening situations and more sensitised to risk than men (see Hollander, Citation2001; Maxfield et al., Citation2010), we deem it likely that women take Covid-19 more seriously than men and show behaviour that is more careful. For our third control variable, education, we also follow the literature and hypothesise that risky behaviour decreases with the respondent’s education level (see Outreville, Citation2015). Highly educated people are likely to inform themselves better about the pandemic and hence be more aware of its dangers (Grönlund & Milner, Citation2006). To operationalise education, we use a 6-value ordinal variable ranging from ‘no formal education’ to ‘post-graduate level studies’. The fourth control variable is religious affiliation. In more detail, we distinguish six groups via a dummy coding (i.e. Catholic, Evangelical, Spiritist/Kardecist, Afro-Brazilian religion, other, not religious). We include information on religion for two reasons. First, some churches insisted on in-person meetings despite the dangers of the pandemic. Second, and relatedly, religious services are responsible for several large-scale Covid-19 outbreaks, including in Brazil (Wildman et al., Citation2020).Footnote10 Finally, we control for the colour or race of the respondent and distinguish between five skin colours (i.e. white, black, brown, indigenous and Asian).Footnote11 We expect white people to be more cautious because of the overall more privileged socio-economic, sanitary and livelihood conditions they experience compared to black or brown people in Brazil. In the context of the pandemic, economic insecurity experienced by the black and brown population dramatically decreased their ability to practise social distancing and stop going to work. This group is highly dependent on staying in their often-precarious jobs, which often require long commuting journeys, despite the threat it poses to their health. In addition, poorer neighbourhoods, suburbs and unplanned urban settlements (e.g. slums) are mainly inhabited by black and brown people.Footnote12

For each dependent variable, we present six models (i.e. three models featuring Bolsonaro’s vote share as the dependent variable and three models featuring satisfaction ratings, with Bolsonaro as the dependent variable). Models 1 and 4 in each set of models measure the relationship between our two proxy variables measuring support for Bolsonaro and our four dependent variables in the bivariate realm. Models 2 and 5 include all control variables. For these, our main models, we also present so-called marginal effects plots to visualise the predicted difference for any of our four outcome variables for Bolsonaro supporters and non-Bolsonaro supporters. Models 3 and 6 are robustness checks. In these additional specifications, we add a control variable for political ideology (i.e. citizens’ self-placement on a 0–10 left–right scale). Despite the fact that political ideology is correlated with support for Bolsonaro (i.e. the correlation coefficient between satisfaction with President Bolsonaro and the left–right scale is 0.5), we add this control variable to capture the effect of populism that goes beyond political ideology, and includes the polarising and anti-science stance the populist’s messaging entails. We also add federal state fixed effects to all multivariate models, given that Brazil is a federation, in which federal states could decide upon Covid-19 related policies such as measures to contain the crisis.

The differences in the operationalisation of our four dependent variables necessitate catered modelling strategies. The first dependent variable, respondents’ belief in science, has 11 categories (i.e. 0–10), which renders ordinary least squares (OLS) regression a viable option. The second dependent variable is binary, measuring whether respondents consider Covid-19 to be the most important topic faced by the country. The binary nature of this variable makes binary logistic regression a preferred choice. Analogous to our first dependent variable, the third dependent variable, on whether interviewees are fearful of catching the disease, uses an 11 point-scale, which again allows for OLS. The final dependent variable on wearing masks in public is a five-value ordinal scale, which necessitates the use of ordered logistic regression analyses.

The second part of our analysis looks at whether the potential attitudinal and behavioural differences between supporters and opponents of Bolsonaro have real world consequences when it comes to citizens’ Covid-19 response. We gauge whether both have an impact on infection rates and death rates caused by Covid-19. To reduce the effect of an ecological fallacy as much as possible, we collected data on the lowest available administrative unit, namely the municipal level. We are interested in whether municipalities with high levels of support for Bolsonaro are hit harder by Covid-19 than municipalities with lower levels of presidential support. To test this relationship, we tried to collect data on Covid-19 infections and death rates for each of the 5,570 municipalities, as of 8 December 2020, the final day the survey was in the field. We succeeded in collecting data for nearly all municipalities (i.e. we base our bivariate model on 5,569 municipalities and our multivariate model on 5,553 municipalities). This implies that our municipal level analysis covers at least 99.6% of the municipalities in Brazil.

We measure both dependent variables as the total number of Covid-19 cases and the total number of Covid-deaths per 10,000 inhabitants, respectively. The independent variable that serves as proxy for Bolsonaro’s support is the vote share President Bolsonaro received in the first round of the presidential elections 2018. Given that Covid-19-induced death and infection rates depend on a slew of other factors, we include four control variables in our analysis: population density; education; affluence of the municipality; and the share of the elderly population over 65. For population density, which we measure as the number of inhabitants per square kilometre, we expect less densely populated municipalities to have lower infection and death rates, as inhabitants are more likely to have fewer contacts with others (Bhadra et al., Citation2021). We further predict a positive relationship between education and material affluence on the one hand and infection and death rates on the other hand (Daniel, Citation2020). More educated and richer municipalities should be more likely to follow health guidelines and ought to have the means to provide the sanitary material and health services necessary to fight the disease (Baena-Díez et al., Citation2020). We operationalise education by the percentage of the municipality’s population with at least some tertiary education. Finally, we hypothesise that older municipalities might suffer from higher death rates, as statistically 80 percent of the Covid-19-caused deaths are in those over 65 years of age (Dowd et al., Citation2020). Our proxy for the ‘old age’ of municipalities is the percentage of citizens 65 and over.Footnote13

To test the influence of the municipal level vote share on infection and death rates, we first present some descriptive statistics displaying the effect of electoral support for Bolsonaro on Covid-19-induced infection and death rates. In a second step, we present the results of two multiple OLS regression analyses. On the left-hand side of each model is the infection and death rate, respectively. On the right-hand side are our independent variable of interest, Bolsonaro’s vote share as well as the four control variables. To control for variation in policy such as lockdown orders or confinement measures, we control for the federal state the municipality is located in, through state fixed effects. The fixed effects control for the fact that federal states in Brazil varied significantly in their response to the pandemic. For instance, the states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Amazonas adopted considerably less stringent measures than others like São Paulo. Mato Grosso do Sul and Amazonas adopted measures to prohibit large-scale events, to hold campaigns to inform the public, and to control the influx of passengers. Others, like São Paulo, went much further, declared state-wide closures of non-essential services, and prohibited gatherings.

Results

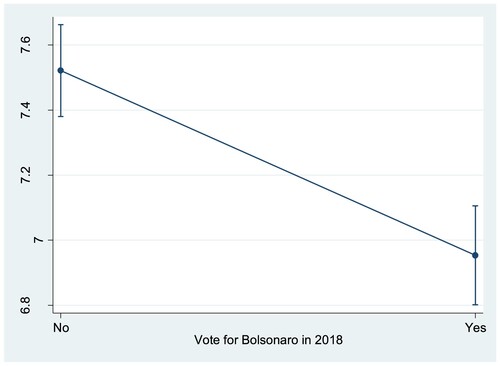

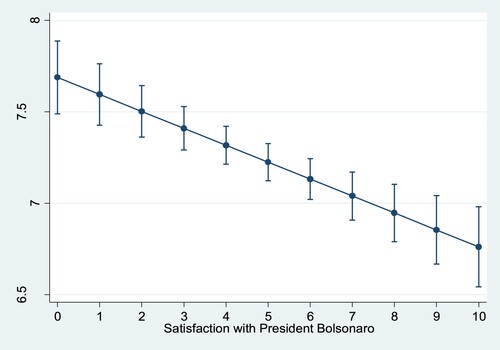

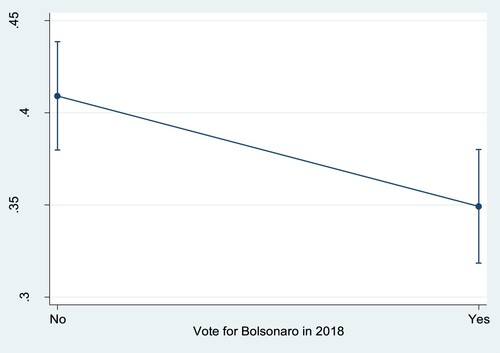

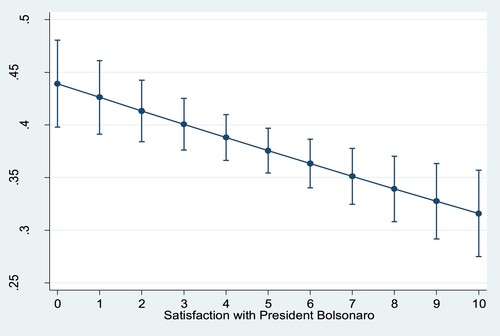

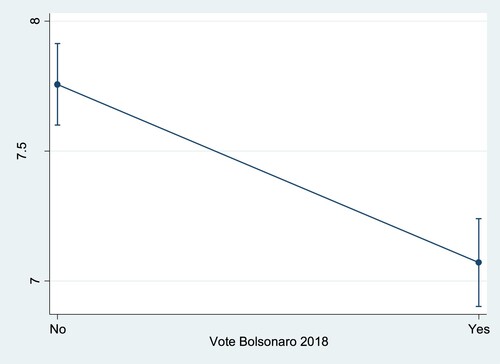

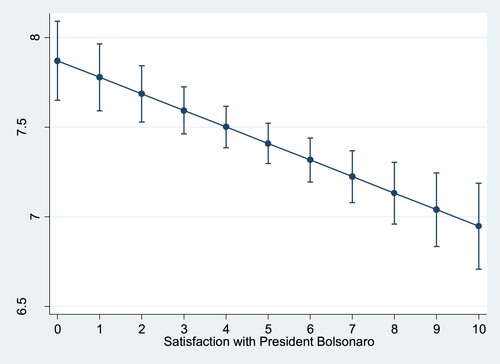

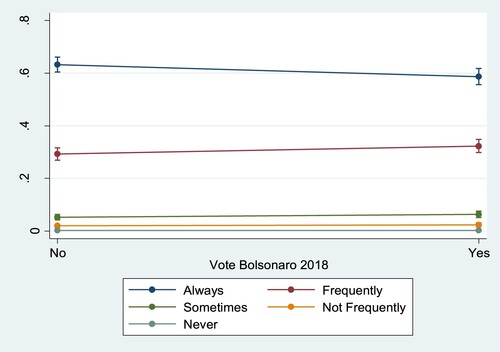

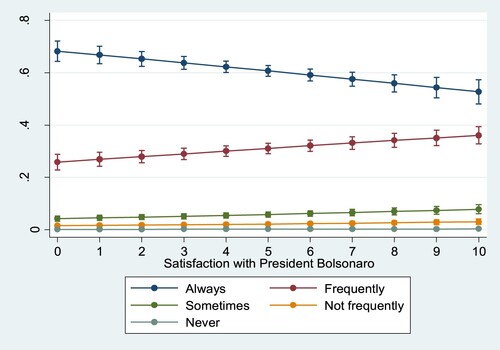

When it comes to individual attitudes and behaviours, we find clear differences between Bolsonaro supporters and non-Bolsonaro supporters (see as well as ). In support of our hypothesis, our 24 regression analyses illustrate that both proxies measuring support for the Brazilian president – the self-declared voter choice in favour of Bolsonaro in 2018 and the president’s satisfaction rating in 2020 – influence our four dependent variables in the expected direction. That is, support for Bolsonaro seems to limit respondents’ belief in science, might entice them to attribute little importance to the disease, might decrease their fears of catching the disease, and might reduce their likelihood of wearing masks. Any of these associations is statistically significant both in the bivariate and multivariate realm. If we consider the proxy variable satisfaction with President Bolsonaro, our models predict that individuals who are satisfied with the president

have a one-point lower support rating for science than individuals who are not satisfied with the president (on a 11-point scale) (see )

are more than a third less likely to rate Covid-19 as the most important topic in the country (see )

are by approximately 1 point less afraid of catching the infectious disease (on the 11-point scale) (see )

have a nearly 10 percentage points lower likelihood of wearing a mask in public all the time (see ).Footnote14

Figure 3. The predicted effect of satisfaction ratings with Bolsonaro on respondents’ belief in science

Figure 4. The predicted effect of voting for Bolsonaro in 2018 on respondents’ belief that Covid-19 is the most important topic Brazil is currently facing

Figure 5. The predicted effect of satisfaction ratings with Bolsonaro on respondents’ belief that Covid-19 is the most important topic Brazil is currently facing

Figure 6. The predicted effect of voting for Bolsonaro in 2018 on respondents’ fear of catching Covid-19

Figure 7. The predicted effect of satisfaction ratings with Bolsonaro on respondents’ fears of catching COVID-19

Figure 8. The predicted effect of voting for Bolsonaro in 2018 on respondents’ likelihood of wearing a facemask in public

Figure 9. The predicted effect of satisfaction ratings with Bolsonaro on respondents’ likelihood of wearing a facemask in public

Table 1. The effect of support for Bolsonaro on respondents’ belief in science (OLS)Table Footnotea

Table 2. The effect of support for Bolsonaro on respondents’ belief that Covid-19 is the most important topic in Brazilian politics (Binary Logistic Regression Analysis)Table Footnotea

Table 3. The effect of support for Bolsonaro on respondents’ fear of catching COVID-19 (OLS)Table Footnotea

Table 4. The effect of support for Bolsonaro on respondents’ likelihood to wear a mask in public (Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis).

If we look at Models 3a to 3d, as well as 6a to 6d, we also find that these effects for support for Bolsonaro appear unchanged if we include political ideology as an additional control variable. Thus, our robustness checks give further credence to our argument that the attitudinal and behavioural effects of populism go beyond the left–right dichotomy. We thus find some evidence that with his propagation of conspiracy theories, the (deliberate spread of misinformation), and his bifurcation of society into good and bad, Bolsonaro seems to entice his supporters to follow his bad example.

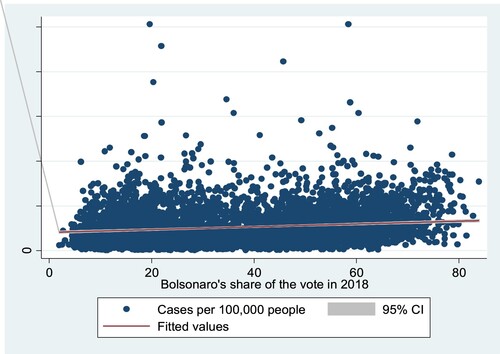

The second part of the analysis illustrates that these more careless attitudes and behaviours of Bolsonaro supporters do not appear to be without consequence. Rather on the contrary, it seems that they directly help spread the disease and increase deaths’ figures caused by the illness. This spread of disease tends to be visible at the municipal level. Municipalities with more electoral support for Bolsonaro in the presidential elections of 2018, appear to have more people infected by the disease and more people succumbing to the virus (see also Razafindrakoto et al., Citation2021; Xavier et al., Citation2022 for similar results). If we graph just the bivariate relationship between the Brazilian president’s vote share and the infection rate per 100,000 inhabitants, we find that for every 10-percentage points’ increase in the president’s vote share, infection rates tend to increase by 156 cases per 100,000 (see ). If we take the average infection rate, which is 2,646 people per 100,000 inhabitants, an increase or decrease of 156 cases for every 10-point change in the Bolsonaro vote seems to be meaningful. This effect becomes even stronger if we consider that in the multivariate realm, the predicted effect of the vote share for Bolsonaro on Covid-19 infection rates surges to a predicted 420 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants for every 10 percentage points’ increase in the president’s vote share (see ). This implies that if we control for other confounders and state-level characteristics such as the laws and procedures in place in the various federal states, the net effect of the president’s vote appears to increase rather substantially.

Figure 10. The effect of the electoral support for Bolsonaro in 2018 on the number of Covid-19 cases per 100,000 inhabitants

Table 5. The effect of the municipal level electoral support for Bolsonaro on COVID-19 cases (see Models 7 and 8) and COVID-19 related death (see Models 9 and 10) (OLS).

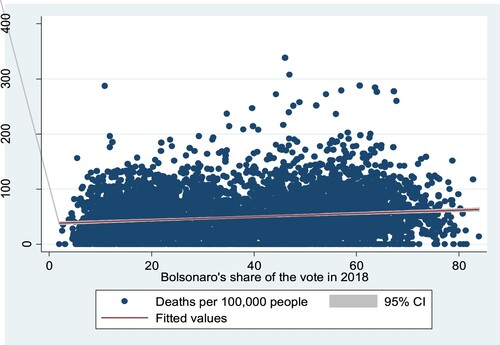

As hypothesised, our results also portray a positive relationship between the vote percentages Bolsonaro received in a municipality, and the municipality’s official death rates caused by Covid-19. On average, in the municipalities we covered in our study, 50 people had died from Covid-19 for every 100,000 inhabitants by December 2020. highlights that this number increases by 3 more deaths for every 10 percentage points’ boost in the vote share for the Brazilian President. If we look at the multivariate model, this number seems to increase to a predicted 7 more deaths per every 10 percentage points’ growth in Bolsonaro’s vote share; again, this illustrates a predicted higher net effect if we control for federal state-level characteristics such as the rules and regulations in place in each state.

Figure 11. The effect of the electoral support for Bolsonaro in 2018 on the number of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants

Illustrating that there is a clear connection between populist communication, a leader’s supporters’ behaviour and health outcomes at the municipal level, this study adds to the growing research on how leaders’ cues and communication impact voters’ attitude and behaviour (Acemoglu & Jackson, Citation2015; Antonakis et al., Citation2014; Dewan & Myatt, Citation2008; Hermalin, Citation2017; Merkley & Stecula, Citation2020). More specifically, we contribute to research on the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and its political dynamics, which suggests that in polarised societies partisanship affects individuals’ beliefs and compliance with health measures (Allcott et al., Citation2020; Gadarian et al., Citation2020; Pickup et al., Citation2020). More clearly, we illustrate that populist supporters follow the signals of their leader; they have a higher likelihood than non-populist supporters to defy crisis mitigation measures. These behavioural patterns, in turn, can have clear practical implications; they can affect life and death.

Conclusion

Jair Bolsonaro is part of an illustrious group of populists who have consistently downplayed the pandemic. Other members in this group are Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus, Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua and Donald Trump (see Meyer, Citation2020). In this research, we have shown that the actions of these populists matter in a pandemic such as Covid-19, particularly in highly polarised societies. If, as President Bolsonaro did repeatedly, the populist downplays the pandemic, defies scientific recommendations and rejects basic preventative measures, the leader’s messages shape his/her supporters’ beliefs, and those followers join the leader in these behavioural patterns. Bolsonaro’s supporters seem to be less likely to believe in science, less likely to give the pandemic the importance it deserves, less fearful of catching the disease, and less likely to wear masks. These more risk-taking attitudes and behaviours can have real-world consequences, not only for Bolsonaro’s supporters themselves, but also for the community in which they live; our results suggest that they increase both infection and death rates in villages, town and cities with high support for the Brazilian president.

Our study complements previous research showing that Bolsonaro’s communication promoted polarisation and affected his supporters’ perceptions about the Covid-19 outbreak (Batista Pereira & Nunes, Citation2021), and that Bolsonaro’s actions stimulated noncompliance with collective efforts to mitigate the pandemic, especially among his supporters (Ajzenman et al., Citation2020; Cabral et al., Citation2021; Calvo & Ventura, Citation2020). Our results tie into Gramacho et al. (Citation2021), who illustrate that Bolsonaro’s supporters know significantly less about the Covid-19 virus and illness, and are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories about the origins of the virus (Gramacho et al., Citation2021). Moreover, our findings are in line with Xavier et al. (Citation2022) and Razafindrakoto et al. (Citation2021) who show that municipalities with high support for Bolsonaro were hit hardest by Covid-19.

We can observe the same patterns of cueing when it comes to vaccines. As soon as vaccination campaigns kicked off around the world, Bolsonaro started to raise questions about the jab and fostered mistrust about it, and the rejection of Covid-19 vaccines was particularly strong among his supporters (Gramacho & Turgeon, Citation2021). We believe that identity connections with Bolsonaro provided a strong rationale for his supporters to follow him and defy science and Covid-19 protective measures.

A short thought experiment illustrates that ‘the Bolsonaro effect’ appears strong in our analysis. Let us assume a hypothetical municipality with 100,000 inhabitants, a population density of 200, an average GDP per capita of 10,000, a 5 percent tertiary education rate and with 20 percent of the population aged 65 or above. If in this municipality the Bolsonaro support rate were 10 percent, the predicted Covid-19 infection rate would be approximately 2,730 people per 100,000 inhabitants. If we were to assume that half the population voted for Bolsonaro, the predicted infection rate would increase to approximately 3,710 based on the predictions from Model 8. The predicted death rates also illustrate an impressive divergence for the same two hypothetical municipalities. Model 10 would predict a death rate of 18 people per 100,000 if Bolsonaro gained 10 percent of the vote in the respective municipality and a death rate of 48 people per 100,000 if the Brazilian president had attracted 50 percent of the vote. This example tells us that a populist right-wing leader in a polarised environment can have dire consequences not only for the internal coherence of the country, but also for the life and death of its citizens.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aline Burni

Aline Burni is a Policy Analyst at FEPS Europe - Foundation for European Progressive Studies and an associate researcher at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). Her research focuses on populism and European development policy.

Daniel Stockemer

Daniel Stockemer is a full Professor at the University of Ottawa and Konrad Adenauer Research Chair in Empirical Democracy Studies. His research interests include among others political participation, elections, social movements and right-wing extremism.

Christine Hackenesch

Christine Hackenesch is a senior researcher at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). Her research focuses on EU development policy and democracy support, EU-Africa relations, China's foreign policy and populism.

Notes

1 See https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-51823908, translation by the authors.

2 Felipe Frazão and Nicholas Shores (2020, May 22). ‘Previsão e que o coronavírus tenha menos mortes que o H1N1, diz Bolsonaro. Uol Notícias. https://noticias.uol.com.br/ultimas-noticias/agencia-estado/2020/03/22/previsao-e-que-coronavirus-tenha-menos-mortes-que-a-h1n1-diz-bolsonaro.htm

3 More from an individualistic stance, Eberl et al. (Citation2021) show that populist attitudes are an important predictor of Covid-19 conspiracy.

4 Tom Phillips (2020, Mar 23). ‘Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro says coronavirus crisis is a media trick’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/brazils-jair-bolsonaro-says-coronavirus-crisis-is-a-media-trick

5 BBC News Brasil (2020, Jul 7). ‘Relembre frases de Bolsonaro sobre a covid-19’. BBC News Brasil https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-53327880 ; Reuters Staff (2020, Jun 28). ‘Fact box: Quotes of fear, defiance and hope as the coronavirus pandemic spans the globe’. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-health-coronavirus-quotes-idUKKBN23Z04M

6 Lisandra Paraguassu and Jamie McGeever. (2020, Mar 27). ‘Brazil government ad rejects coronavirus lockdowns, saying #BrazilCannot Stop’. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-brazil-idUSL1N2BK1XY

7 Tom Phillips. (2020, Jul 08). ‘Brazil: Bolsonaro reportedly uses homophobic slut to mock masks’. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/08/bolsonaro-masks-slur-brazil-coronavirus

8 Daniel Carvalho, Gustavo Uribe and Natalia Cancian. (2020, Sep 1). ‘Ninguém pode obrigar ninguém a tomar vacina, diz Bolsonaro’ Folha de São Paulo https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2020/09/ninguem-pode-obrigar-ninguem-a-tomar-vacina-diz-bolsonaro.shtml

9 Please note that we did not create a separate category for non-voters for our main analyses because this category makes up less than 9 percent of the survey respondents. However, if we exclude this group and run all analyses separately, the results do not change.

10 We also ran all models with the additional control variable the financial situation of the respondent’s household. Adding this control does not change any of the models. However, we did not include the personal financial situation of the respondent in the models, because more than 20 percent of the respondents did not want to answer this question.

11 Racial measurement in the Brazilian census has always referred to skin colour, which relates to the phenotype (physical appearance) and not to ancestry (origin) (Travassos & Williams, Citation2004). According to data from the 2019 National Household Sample Survey (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios / PNAD), 42.7% of Brazilians declared themselves as white, 46.8% as brown, 9.4% as black, and 1.1% as yellow or indigenous. Brazil has the largest population of African ancestry in the Americas. Miscegenation is part of the country’s history. The official term referring to admixed population in the census is ‘pardo’, translated to ‘brown’.

12 For example, Tavares and Betti (Citation2021) illustrate that death rates in Brazil caused by Covid-19 are highest among the most vulnerable groups and that brown and black people are more severely affected compared to Asian or white people. See also: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) (2020, Nov. 13). 'Segundo Boletim Socioepidemiológico da Covid-19 nas Favelas'. https://portal.fiocruz.br/documento/boletimsocioepidemiologico-da-covid-19-nas-favelas-ed-2.

13 We obtained data at the level of municipalities from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística / IBGE). We retrieved the percentage of elderly people in each municipality from the Health Indicators and Policy Monitoring System for the Elderly (Sistema de Indicadores de Saúde e Acompanhamento de Políticas do Idoso / SISAP idoso).

14 Because there is some discussion in econometrics (see Angrist & Pischke, Citation2009) on whether we can run maximum likelihood estimations as OLS models, we also ran all models in and as OLS models (see Tables 2A and 4A in the appendix). The coefficients in these models are analogous to those in our main models.

References

- Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. Elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.11.001

- Acemoglu, D., & Jackson, M. O. (2015). History, expectations, and leadership in the evolution of social norms. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(2), 423–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdu039

- Ajzenman, N., Cavalcanti, T., & Da Mata, D. (2020). More than words: Leaders’ speech and risky behavior during a pandemic. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3582908

- Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J. C., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & D. Yang (2020). Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. Working Paper 26946. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26946

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist's companion. Princeton University Press.

- Antonakis, J., d’Adda, G., Weber, R., & Zehnder, C. (2014). Just words? Just speeches? On the economic value of charismatic leadership. NBER WP. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.4219

- Bækgaard, M., Christensen, J., Madsen, J. K., & Mikkelsen, K. S. (2020). Rallying around the flag in times of COVID-19: Societal lockdown and trust in democratic institutions. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.32.172

- Baena-Díez, M. J., Barroso, M., Cordeiro-Coelho, S. A., Díaz, J. L., & Grau, M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 outbreak by income: Hitting hardest the most deprived. Journal of Public Health, 42(4), 698–703. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa136

- Banerjee, A., Alsan, M., Breza, E., Chandrasekhar, A., Chowdhury, A., Duflo, E., Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., & Olken, B. (2020). Messages on COVID-19 prevention in india increased symptoms reporting and adherence to preventive behaviors among 25 million recipients with similar effects on non-recipient members of their communities. Working Paper 27496. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27496

- Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797–817. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118364

- Batista Pereira, F., & Nunes, F. (2021). Media choice and the polarization of public opinion about COVID-19 in Brazil. Revista Latinoamericana De Opinión Pública, 10(2), 39–57. (Anexo 59). https://doi.org/10.14201/rlop.23681

- Bhadra, A., Mukherjee, A., & Sarkar, K. (2021). Impact of population density on COVID-19 infected and mortality rate in India. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 7(1), 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-020-00984-7

- Boin, A., & ’t Hart, P. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Public Administration Review, 63(5), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00318

- Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2016). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure (2nd ed). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339756

- Burni, A., & Tamaki, E. (2021). Populist communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Brazil’s president bolsonaro. Partecipazione & Conflitto, 14(1), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v14i1p113

- Cabral, S., Ito, N., & Pongeluppe, L. (2021). The disastrous effects of leaders in denial: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis in Brazil. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract = 3836147 or http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3836147

- Calvo, E., & Ventura, T. (2021). Will I get COVID-19? Partisanship, social media frames, and perceptions of health risk in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society, 63(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2020.30

- Çelen, B., Mukherjee, A., & Kariv, S. (2004). Distinguishing informational cascades from herd behavior in the laboratory. American Economic Review, 94(3), 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464461

- Daniel, S. J. (2020). Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. PROSPECTS, 49(1), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3

- Dewan, T., & Myatt, D. (2008). The qualities of leadership: Direction, communication, and obfuscation. The American Political Science Review, 102(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055408080234

- Dowd, J., Andriano, L., Brazel, D. M., Rotondi, V., Block, P., & Ding, X. (2020). Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(18), 9696–9698. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004911117

- Eberl, J. M., Huber, R., & Greussing, E. (2021). From populism to the ‘plandemic’: Why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(sup1), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730

- Fennema, M. (2005). Populist parties of the right. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), Movements of exclusion: Radical right-wing populism (pp. 1–24). Nova Science Publishers.

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Gadarian, S. K., Goodman, S. W., & Pepinsky, T. B. (2020). Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3562796. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3562796

- Golub, B., & Jackson, M. O. (2010). Naïve learning in social networks and the wisdom of crowds. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2(1), 112–149. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.2.1.112

- Gramacho, W. G., & Turgeon, M. (2021). When politics collides with public health: COVID-19 vaccine country of origin and vaccination acceptance in Brazil. Vaccine, 39(19), 2608–2612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.080

- Gramacho, W., Turgeon, M., Kennedy, J., Stabile, M., & Mundim, P. S. (2021). Political preferences, knowledge, and misinformation about COVID-19: The case of Brazil. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 646430. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.646430

- Grönlund, K., & Milner, H. (2006). The determinants of political knowledge in comparative perspective. Scandinavian Political Studies, 29(4), 386–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2006.00157.x

- Hawkins, K. A. (2009). Is chávez populist?: Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective.”. Comparative Political Studies, 42(8), 1040–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009331721

- Hawkins, K., & Littvay, L. (2019). Contemporary US populism in comparative perspective (1st ed). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108644655

- Hawkins, K., Read, M., & Pauwels, T. (2017). Populism and its causes. Edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.13

- Hermalin, B. E. (2017). At the Helm, Kirk or Spock? Why even wholly rational actors may favor and respond to charismatic leaders. Technical Report. Working paper, UC Berkeley. https://www.tse-fr.eu/sites/default/files/medias/stories/sem_13_14/IO/hermalin.pdf

- Hollander, J. A. (2001). Vulnerability and dangerousness: The construction of gender through conversation about violence. Gender and Society, 15(1), 83–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015001005

- Hunter, W., & Power, T. J. (2019). Bolsonaro and Brazil’s illiberal backlash. Journal of Democracy, 30(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0005

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotrt, N., & Westwood, S. N. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

- Kearney, M. S., & Levine, P. B. (2015). Media influences on social outcomes: The impact of MTV’s 16 and pregnant on teen childbearing. American Economic Review, 105(12), 3597–3632. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20140012

- Kingstone, P. R., & Timothy, J. P. (eds.). (2017). Democratic Brazil divided. Pitt latin American series. Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Kitschelt, H., & McGann, J. A. (1995). The radical right in Western Europe: A comparative analysis. University of Michigan Press.

- Kluwe-Schiavon, B., Wendt, T., Viola, Bandinelli, L. P., Castro, S. C. C., Kristensen, C. H., Costa da Costa, J., & Grassi-Oliveira, R. (2021). A behavioral economic risk aversion experiment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 16(1), e0245261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245261

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso Books.

- Lenz, G. S. (2013). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. University of Chicago Press.

- Levi, M. (1988). Of rule and revenue. University of California Press.

- Maxfield, S., Shapiro, M., Gupta, V., & Hass, S. (2010). Gender and risk: Women, risk taking and risk aversion. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(7), 586–604. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411011081383

- McCormick, J. P. (2001). Machiavellian democracy: Controlling elites with ferocious populism. The American Political Science Review, 95(2), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055401002027

- Merkley, E., & Stecula, D. (2020). Party cues in the news: Democratic elites, republican backlash and the dynamics of climate skepticism. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1439–1456. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000113

- Meyer, B. (2020). Pandemic populism: An analysis of populist leaders’ responses to Covid-19. Tony Blair Institute for Global Governance Working Paper. https://institute.global/policy/pandemic-populismanalysis-populist-leaders-responses-covid-19

- Michel, E., Garzia, D., Ferreira da Silva, F., & De Angelis, A. (2020). Leader effects and voting for the populist radical right in Western Europe. Swiss Political Science Review, 26(3), 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12404

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Outreville, J. F. (2015). The relationship between relative risk aversion and the level of education: A survey and implications for the demand for life insurance. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12050

- Pevehouse, J. C. W. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic, international cooperation, and populism. International Organization, 74(S1), E191–E212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000399

- Pickup, M., Stecula, D., & van der Linden, C. (2020). Novel coronavirus, old partisanship: COVID-19 attitudes and behaviours in the United States and Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 53(2), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000463

- Platow, M. J. S., Haslam, A., Reicher, D. S., & Steffens, N. (2015). There is no leadership if no-one follows: Why leadership Is necessarily a group process. International Coaching Psychology Review, 10(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsicpr.2015.10.1.20

- Razafindrakoto, M., Roubaud, F., Saboia, J., Reis Castilho, M., & Pero, V. (2021). Municípios in the time of COVID-19 in Brazil: Socioeconomic vulnerabilities, transmission factors and public policies. The European Journal of Development Research. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00487-w

- Rennó, L., Avritzer, L., Carvalho, & de Carvalho, P. D. (2021). Entrenching right-wing populism under COVID-19: Denialism, social mobility, and government evaluation in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política, 36. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-3352.2021.36.247120

- Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems. Cambridge University Press.

- Schneiker, A. (2020). Populist leadership: The superhero Donald Trump as savior in times of crisis. Political Studies, 68(4), 857–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720916604

- Tavares, F. F., & Betti, G. (2021). The pandemic of poverty, vulnerability, and COVID-19: Evidence from a fuzzy multidimensional analysis of deprivations in Brazil. World Development, 139, 105307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105307

- Travassos, C., & Williams, D. R. (2004). The concept and measurement of race and their relationship to public health: A review focused on Brazil and the United States. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 20(3), 660–678. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2004000300003

- Van Bavel, J. J., & Pereira, A. (2018). The partisan brain: An identity-based model of political belief. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.004

- Weyland, K. (2021). Populism as a political strategy: An approach’s enduring – and increasing – advantages. Political Studies, 69(2), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211002669

- Wildman, W. J., Bulbulia, J., Sosis, R., & Schjoedt, U. (2020). Religion and the COVID-19 pandemic. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 10(2), 115–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2020.1749339

- Xavier, D. R., e Silva, E. L., Lara, F., e Silva, G. R. R., Oliveira, M. F., Gurgel, H., & Barcellos, C. (2022). Involvement of political and socio-economic factors in the spatial and temporal dynamics of COVID-19 outcomes in Brazil: A population-based study. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas, 10, 100221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100221

Appendix

Table A1. Sampling Techniques used by the survey company.

Table A2. The effect of support for Bolsonaro on respondents’ belief that COVID-19 is the most important topic in Brazilian politics (OLS).

Table A3. The effect of support for Bolsonaro on respondents’ likelihood to wear a mask in public (Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis).