ABSTRACT

This paper conducts an in-depth case study of the 2010 Greek entrepreneurship attempts that led to the EFSF's creation, aiming to theorise crisis-induced institutional change in the EU. This research aims to cover the theoretical gap left by existing literature by combining theoretical elements derived from historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship. Crises function as critical junctures. During critical junctures, the structural grip of path dependency loosens; thus, a multitude of paths forward are available. The choice of a specific path, if any, heavily relies on the concept of institutional entrepreneur. In 2010 the Greek government was such an agent, with interest in altering EU institutional design to overcome its financial ordeal and with direct access to the EU Council, the primary decision-making body regarding institutional change. The entrepreneur triggers a process of institutional change through their proposal. Once the entrepreneur chooses a path forward, this is further moulded by path dependencies.

1. Introduction

In the aftermath of the 2010 Euro-crisis, the European institutional landscape changed. The founding of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) led to a change in the European institutional architecture through the institutionalisation of economic crisis management (Kreuder-Sonnen, Citation2019). However, a European crisis response through the formation of an institution which functioned as a lender of last resort (Strauch, Citation2019) seems paradoxical if one revisits the political context of the era. The legality of such mechanisms within the European Union (EU) legal framework was questionable (Hinarejos, Citation2013; Rompuy, Citation2014). At the same time, major stakeholders of the ‘would-be’ EFSF, such as Germany, had rejected a European response to the Greek prelude of the Eurozone crisis (Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Traynor, Citation2010). The main actor embedded in the EU framework which had tabled the proposal of a European institutional solution to the crisis was the Greek government (Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Papandreou, Citation2021).Footnote1

The despite the odds fruition of the Greek proposal begs the question: What explains the formation of EFSF? I treat the case of the EFSF as one of European crisis-induced institutional change. This article aims to cover existing gaps in the European institutional change literature through the combination of elements from historical institutionalism and the concept of the institutional entrepreneur (Dimaggio, Citation1988; Mahoney, Citation2001; Zahariadis, Citation2008). This combination results in an agent-driven historical institutionalism. This endeavour is necessary as the rational assumptions of European integration theories, such as liberal intergovernmentalism and functionalism, delimit their usefulness in times of uncertainty, such as a crisis (Haas, Citation1961; Moravcsik & Schimmelfennig, Citation2018; Swinkels, Citation2020). At the same time, historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship literature, which are compatible with a crisis, have until now been used in mutual exclusion, thus, failing to map a coherent mechanism of crisis-induced institutional change. Their combination is mandated because institutional entrepreneurship literature neglects the impact of structural constraints in the process of institutional change. At the same time, historical institutionalism is overly structural and fails to explain why a specific path of institutional change was chosen over others during a crisis.

The main argument of this paper is that an agent-driven historical institutionalism can offer a coherent mechanism of crisis-induced institutional change in the EU. More specifically, I argue that crises challenge the perception of a system's structural, normative, and functional validity, forcing policymakers to decide under conditions of uncertainty and limited information (Ansell et al., Citation2016). In this setting, crises function as what historical institutionalists would define as critical junctures. Critical junctures are periods of uncertainty, such as a crisis when the structural grip of path dependency loosens, and thus a multitude of paths forward are available (Mahoney, Citation2001). This is where the role of the institutional entrepreneur is crucial. I argue that the choice of a specific path, if any, heavily relies on the concept of institutional entrepreneur. Institutional entrepreneurs are agents already embedded in the organisational architecture of an institution, with access to its decision-making body and motive to alter its structure (Dimaggio, Citation1988; Garud et al., Citation2007). In 2010 the Greek government was such an agent, with an interest in altering EU institutional design to overcome its financial ordeal and with direct access to the European Council, the primary decision-making body with regards to institutional change(Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; TFEU, Citation2008; Papandreou, Citation2021). Overall, I argue that within the setting of a crisis, a window of opportunity opens, and multiple institutional reform paths are available(Mahoney, Citation2001; Zahariadis, Citation2008). Those paths are not unlimited; their ‘availability’ depends on previous path dependencies. The entrepreneur triggers a process of institutional change through their proposal. Once the entrepreneur chooses a path forward, this is further moulded by the historical institutionalist concept of path dependency (Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009; Mahoney, Citation2001). The empirical data gathered, to a great extent, verify these theoretical expectations and suggest that they might need to be amended by the concept of organisational cultural contestation (Finnemore & Sikkink, Citation1998).

In examination of the research question, I am conducting an in-depth case study focusing on the related events (Bennett & Elman, Citation2007; Rohlfing, Citation2012). This allows me to deduce the broader mechanism explaining European crisis-induced institutional evolution (Machamer et al., Citation2000; Starman, Citation2013). To shed light on the case and trace the underlying mechanism, I conducted four semi-structured interviews with George A. Papandreou, the Greek Prime Minister during the 2010 Eurozone crisis, two members of his cabinet who were involved in the EFSF negotiations and today belong to different political families within the Greek political spectrum and a member of the 2010 International Monetary Fund (IMF) Executive Board.Footnote2

The choice to conduct the interviews with Greek officials is based on three criteria. First, they provide insight into the strategies of the entrepreneur related to the formation of the institutional-change proposal and its framing. Secondly, they can uncover whether the acting entities felt bound by the existing institutional framework. Thirdly, they provide an inside view of the negotiations. The latter will be particularly useful in extracting information about the rationale of the actors, leading to the intergovernmental nature of the EFSF and IMF involvement. The drawback of interviews is that the respondents offer their version of reality (Mosley, Citation2013). This methodological hazard is partly negated because I execute internal triangulation by interviewing multiple participants of the Greek entrepreneurship attempts, whose political paths split after the crisis and today hold divergent positions within the Greek political spectrum (Nøkleby, Citation2011). This is complemented through interviews with a member of the 2010 IMF Board and authorised biographies and autobiographies of European Council members who were ‘sitting on the opposite side of the table. Further triangulation is conducted through data gathered from archived primary and secondary sources, such as already published academic research, synchronous to the events news coverage and official government documents (Nøkleby, Citation2011). The use of sources other than interviews is necessary for the examination of the actions and views of agents to whom I do not have access through interviews (Howell & Prevenier, Citation2001).

The structure of the paper is the following: In the next section, I review the main theories discussing institutional change in the EU. Subsequently, I elaborate on the theoretical framework, which builds upon elements from historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship literature. In the latter half of the paper, I analyze the empirical data and draw a broader mechanism linking the entrepreneur and crisis-induced institutional change. Finally, I summarise the main findings of the paper and identify avenues for further research in the conclusion.

2. Theories of EU institutional change

European institutional evolution has been analyzed under multiple scopes covering European integration theories, historical institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism through the lens of institutional entrepreneurship. Most of these theories have offered us valuable tools to explain the 2010 crisis-induced EU institutional evolution. Nonetheless, their application in insulation of each other has led to occasional theoretical blind spots. In what follows, I review these theoretical camps and argue that a more comprehensive explanation of European crisis-induced institutional evolution is possible through the combination of historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship.

The issue of European crisis-induced institutional evolution falls within the frame of European integration. This thematic has been thoroughly discussed under the umbrella of liberal intergovernmentalism (Moravcsik & Schimmelfennig, Citation2018) and the various functionalisms (Haas, Citation1961; Niemann & Ioannou, Citation2015; Sandholtz & Sweet, Citation1997). However, these theories fail to capture crisis-induced institutional change. The epicentre of contention between these theories is related to the question of whether national governments (Moravcsik & Schimmelfennig, Citation2018) or European bureaucracy (Haas, Citation1961; Niemann & Ioannou, Citation2015; Sandholtz & Sweet, Citation1997) propel regional integration. Intergovernmentalists argue that institutional evolution is fueled by the states’ need to reduce information asymmetries (Keohane, Citation1982; Moravcsik & Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). Functionalists claim that regional bureaucracies’ previous successes trigger further integration (Haas, Citation1961; Niemann & Ioannou, Citation2015; Sandholtz & Sweet, Citation1997). Regardless of their differences, both theories assume that the actors involved are rational, with a predetermined set of preferences, making decisions on a cost-benefit analysis. However, crises confront actors handling them with limited information and unclear preferences, mandating decision-making based on heuristics (Swinkels, Citation2020; Zahariadis, Citation2008). Thus, the rationalist spine of these theories delimit their usefulness in periods such as the one examined here.

Institutional entrepreneurship literature is more compatible with a crisis-prone environment; however, it suffers from limitations of its own. The entrepreneurship concept has always been focused on either the Council as a collective actor (Pircher, Citation2020), the Commission (Ackrill et al., Citation2013; Schön-Quinlivan & Scipioni, Citation2017) or a country group (Saurugger & Terpan, Citation2016). Additionally, the entrepreneur concept has been used with a government ‘on the driver’s seat’ discussing solely failed reform attempts (Dikaios & Tsagkroni, Citation2021). To the best of my knowledge, it has not been researched in the context of a successful entrepreneurship attempt originating from a national government. Finally, entrepreneurship literature insightfully argues that crises open a window of opportunity during which the entrepreneur can introduce institutional change proposals (Ackrill et al., Citation2013; Saurugger & Terpan, Citation2016). However, it disregards the structural limitations posed by previous institutional settings. The extreme version of this blind spot is the perception that the degree and the nature of institutional change are predominately dependent on the ability of the entrepreneur.

On the contrary, historical institutionalism literature successfully analyzes the factors delimiting institutional change, but it fails to explain how these limitations are surpassed. Historical institutionalists insightfully describe crises as events that potentially enable institutional change (Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Pollack, Citation2019), they mark the structural boundaries of this change (Pollack, Citation2019; Verdun, Citation2015), and they provide a comprehensive institutional-evolution typology (McNamara & Abraham, Citation2009; Salines et al., Citation2012; Schwarzer, Citation2012). However, they fail to explain how and why institutional change takes place, a drawback shared by the historical institutionalist literature focusing on the 2010 Eurozone crisis (Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Pollack, Citation2019; Verdun, Citation2015). Additionally, most of the historical institutionalist work, relative to the Eurozone crisis is more concerned with the accurate categorisation of the crisis-induced evolution rather than the mechanisms through which such an evolution was achieved (McNamara & Abraham, Citation2009; Salines et al., Citation2012; Schwarzer, Citation2012).

Overall, except for the integration theories, the frameworks discussed above view crises as opportunities for institutional evolution. However, they fail to explain how this evolution materialises. Sociological institutionalism literature neglects institutional boundaries, and historical institutionalism is ‘overly institutionalist’. This is a byproduct of the dichotomous application of the relative academic literature, which can be mended if one combines elements from the two institutionalisms. This combination of historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship is what I propose in the theoretical framework that follows.

3. Theoretical framework

The theoretical building blocks of this paper lie in the combination of elements from historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship literature. First, I discuss the crisis concept as a chain link to these theories. Secondly, I present the theoretical tools provided by historical institutionalism, which mark the broad lines within which institutional change is possible. Subsequently, I introduce the concept of institutional entrepreneurship. I argue that institutional entrepreneurship has an important role in the mechanism of crisis-induced institutional change because it resolves historical institutionalism’s inability to explain why and how institutional evolution occurs. Finally, I express my expectations regarding the manifestation of these theoretical elements in the case of the EFSF and Greek entrepreneurship. Overall, I argue that historical institutionalism ‘thins’ available institutional responses during a crisis. From these limited choices, the entrepreneur ‘picks’ one which is further moulded by path dependencies.

3.1. Crises as theoretical chain links

Crises are moments which challenge the perception of structural, normative and functional validity of a system, forcing decision-makers to act under conditions of uncertainty, unclear preferences, limited information and time (Ansell et al., Citation2016; Boin et al., Citation2009). I treat them as scope conditions and chain links for historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship (Dimaggio, Citation1988; Mahoney, Citation2001; Zahariadis, Citation2008). More concretely, the conditions of uncertainty characterising a crisis relax existing institutional bonds, creating what historical institutionalists define as a critical juncture (Mahoney, Citation2001). The conditions of uncertainty combined with the unclear preferences of the decision-makers, which are typical in a crisis environment, offer the entrepreneur an opportunity to successfully pitch their proposal through what entrepreneurship scholars call a policy window (Zahariadis, Citation2008).

3.2. Historical institutionalism

Historical institutionalists examine how historical processes, critical choices in the past, and existing institutional structure limit and shape institutional architecture (Mahoney, Citation2001; Pierson, Citation2000; Skocpol, Citation1992). They argue that choices made when an institution is created or a decision is taken matter for both the temporal framework synchronous to the choice and for the future. Once a path forward has been selected, each passing day makes it more difficult to reverse it, and thus, future decisions will be bounded by that past choice. Consequently, future institutional-change options are ‘thinned’ to those in accordance with those past choices. Historical institutionalists have named this process path dependency (Mahoney, Citation2001; Pierson, Citation2000).

The causal factor behind those path dependencies lies with certain ‘feedback mechanisms’. One such mechanism relates to the fact that institutions condition actors to certain thought processes through institutional stimulants and deterrents (Esping-Anderson, Citation1990; Streeck, Citation1992). In my case, a potential manifestation of this institutional ‘deterrent’ could be the treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) no-bailout clause, which would block the thought processes leading to an unconditional financial-help package. The second feedback mechanism highlights that power distribution at institutional birth or during critical junctures entrusts decision-making to certain groups, which in turn will aspire to further entrench it (Hanrieder, Citation2015; Skocpol, Citation1992). In the present case study, a manifestation of the above could be the de-jure competence of the Council to propose institutional amendments leading to a transmutation of the Council’s intergovernmental nature to the EFSF structure. A third feedback mechanism relates to the function of ‘institutional precedence’ as a trial-and-error playground (Verdun, Citation2015). In this setting, previous institutions, which enjoyed some degree of success, and which are of similar function to the crisis-born institution, will be copied, and key aspects of their structure and/or function will be transposed to the new institution. In the present case, a potential manifestation of this copying mechanism is the institutional precedence of the Greek Loan Facility (GLF). The relative success of the GLF can shed further light on the intergovernmental nature of the EFSF and, most importantly, the implication of the IMF as a junior partner to the programme (Verdun, Citation2015). Those path dependent trajectories set off during critical junctures, setting the extreme boundaries for institutional change (Hogan, Citation2006; Mahoney, Citation2001; Pierson, Citation2000)

Critical junctures are moments of uncertainty in history, such as a crisis, when an institution's structural bonds relax (Hogan, Citation2006). Thus, multiple but not unlimited paths forward are available. The one chosen will shape the nature of the institution for the years to come. In the lifespan of an institution, multiple critical junctures may occur, and each one will drive the institution down a certain path, restricting the choices available at the next critical juncture (Hogan, Citation2006; Mahoney, Citation2001; Pierson, Citation2000). However, historical institutionalism does not provide us with the theoretical tools to explain why and how one of the paths available during a critical juncture is followed. This is the point of conjunction between entrepreneurship and historical institutionalist literature. Critical junctures are moments in time when an entrepreneur can shape the road ahead.

3.3. The institutional entrepreneur

The structural ‘sclerosis’ of historical institutionalism can be mended by the introduction of the sociological concept of the institutional entrepreneur. The inclusion of the institutional entrepreneur is crucial because it explains why in certain instances, institutional change is preferred instead of stability, why a specific change pathway of the multiple available is followed and under which circumstances this choice enjoys better chances of materialisation.

Public policy (Kingdon, Citation1995; Zahariadis, Citation2008) and sociology scholars (Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009; Dimaggio, Citation1988; Fligstein & Mara-Drita, Citation1996), have ‘painted’ ` institutional entrepreneurs as actors embedded in the organisational structure of an institution, possessing a vested interest to change the existing institutional framework and the tools to intervene in the decision-making process to achieve it (Dimaggio, Citation1988; Garud et al., Citation2007). The concept itself was formulated by sociological institutionalists who identified the conditions facilitating the activation of entrepreneurial attempts (Bakir & Jarvis, Citation2017; Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009; Fligstein & Mara-Drita, Citation1996; Greenwood et al., Citation2002). Public-policy scholars picked up the string and explained how an entrepreneur can achieve change. In the present paper, I argue that among the multiple choices available during a critical juncture, the one followed is chosen by the entrepreneur.

Sociological institutionalists elucidated the enabling conditions for entrepreneurial activity. More concretely, they argue that structure is not a restricting element, but an enabling factor for an entrepreneur embedded in it, because it offers direct access to the decision-making bodies (Bakir & Jarvis, Citation2017; Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009). A second enabling condition lies with moments of uncertainty, such as a crisis, because they upset the existing status quo and shatter old normative beliefs, paving the way for new ideas, which can translate to a new institutional order (Fligstein & Mara-Drita, Citation1996; Greenwood et al., Citation2002).

Public-policy academia created a volatile approach explaining how an entrepreneur can achieve change (Kingdon, Citation1995; Zahariadis, Citation2008). They argue that during opportunity windows such as a crisis, an entrepreneur can steer decision-making towards its preferred direction. More concretely, the entrepreneur capitalises on its position within the institutions’ structure, which grants it access to the decision-making body to pitch its proposal and push it into the ‘to-do’ list of the decision-makers (Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009). The entrepreneur having access to the decision-making body frames the proposed institutional change (European Stability Mechanism) in the political context (risk of financial crisis contagion) and presents this institutional change as the best solution to the problem (financial crisis)(Kingdon, Citation1995; Zahariadis, Citation2008). According to Zahariadis (Citation2008), in cases when the entrepreneurial proposals represent substantial changes to the existing status quo, such as the present case, the entrepreneurs enjoy better odds if they frame their solution as a loss-aversion stratagem. Thus, in the present case study, a potential manifestation of the above could be that the Greek government will use its position in the EU council to propose the creation of a European support mechanism. To achieve the adoption of its proposal, it will frame it in the context of the risk of crisis-contagion as a losses-minimization solution to the Eurozone economic crisis.

3.4. The case of Greece and EFSF

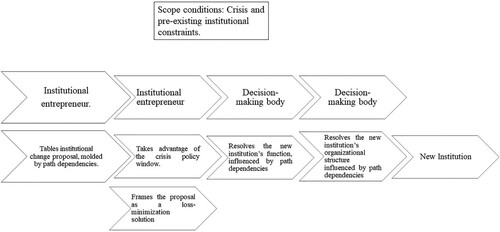

According to all the above, I expect that the empirical evidence gathered will uncover the following process in the case of the Eurozone crisis-induced institutional evolution. The Greek government was activated as an entrepreneur because it had a vested interest in creating a European support mechanism since Greece was a country in financial distress. The entrepreneur was enabled by its position within the institutional structure, as Greece is de-jure a member of the EU Council, the main decision-making body for amendments in European architecture. Additionally, the financial crisis infused uncertainty in the system, opening a window of opportunity. Subsequently, the Greek government engaged in the coupling of the financial instability problem and the political context related to the crisis-contagion risk, putting forward its own solution of a European mechanism as a loss-aversion proposal. I believe that the entrepreneur's proposal was partially pre-moulded by existing path dependencies. More specifically, I expect that the political weight of TFEU will shape the function of the new institution. Moreover, I believe that the intergovernmental nature of EFSF was mandated by the EU institutionalised power relations. The actors responsible for the creation of a new institution in terms of both resources and mandate are the Council member-states. Based on the theoretical discussion above, I expect that they will attempt to further entrench their power, transmuting an intergovernmental modus-operandi to the new institution. Finally, I hypothesise that the lack of previous European experience in the formation of a large-scale and not country-specific institution which would function as a lender of last resort, combined with the previous success of the GLF, resulted in the scavenging of its function and organisational structure. The outcome of the process kickstarted by the entrepreneur and shaped by the limitations posed by path dependencies was the EFSF. The projected process is consolidated and depicted in below:

4. A European odyssey

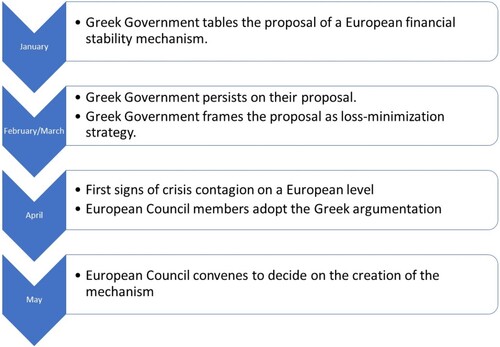

Based on the theory above, I expect that the institutional entrepreneurship attempts of the Greek government triggered a process leading to the formation of a new European Institution, the EFSF. In this chapter, first, I examine the actions establishing the entrepreneurship identity of the Greek government leading up to the adoption of its proposal by the Council. Subsequently, I explore the forces that shaped the function and the organisational structure of the EFSF. The narration follows the historical timeline of the events that unfolded in 2010, as summed in below:

4.1. The Greek government as odysseus

In 2010 the Greek government was an actor with the ability to propose an EU institutional amendment since it is a by-treaty member of the primary EU decision-making body, the European Council (TFEU, Citation2008). In January 2010, Papandreou's administration capitalised on this ability proposing the formation of a European financial support mechanism (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Papandreou, Citation2021). At the outbreak of the Greek crisis in late February 2010, the Greek government (Papandreou, Citation2010b) stressed that ‘The case of Greece shows the need for more Europe, for more institutions’. This is corroborated by the interviews (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023). Characteristically (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023) narrates, ‘we were arguing that regardless of the fiscal-consolidation measures that we were taking, the crisis was European and would not be surpassed without a European support institution’. According to Papandreou (Citation2021), even when it was clear that Greece would need support, his government insisted on a European institutional solution as this would calm the markets, and the need for a costly bail-out would be diminished. Papandreou narrates that during the initial stages of the crisis, his calls for an institutional solution instead of money for Greece fell on deaf ears, yet he insisted on a European solution (Papandreou, Citation2021). This is echoed in van Rompuy's autobiography as he narrates that when discussing the prospective Greek crisis, ‘Papandreou said a few times that he was not asking for money’. The calls of the Greek government for a European solution to the problem are further corroborated by the interview conducted with a member of the IMF executive board. They narrate that ‘in late 2009 – early 2010, we were signalling that Europe as a whole might have to deal with a crisis. However, the only actor pushing for a European solution – probably out of necessity – was the Greek Government’ (Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023). The above showcase that the Greek government was an actor with access to the EU decision-making body and motivation to alter the European institutional architecture to solve its financial predicaments, thus meeting the institutional entrepreneurship definition criteria.

The initial Greek calls for a European solution to the looming crisis fell on deaf ears (Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Traynor, Citation2010). It became clear that for the proposal to materialise, the entrepreneur needed a compelling argument (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023). According to the interviews, it is in this context that the Greek government argued in various international fora that without a European institution, it would be impossible to contain the crisis in Greece (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023). According to interviewee 2 (2021) in the 2010 Davos World Economic Forum, the Greek government argued that: ‘there is a Greek component in a European Crisis. If we [the EU] don't create a European Institution, we will not be ready when the crisis spreads, we will fail to contain it, and the financial cost then will be greater than the cost of a European solution now’. A month later, in March 2010 the Greek PM Papandreou (Citation2010a) highlighted the risk of crisis contagion telling Brookings institute that ‘If the crisis spreads, it could create a new global financial crisis with implications as grave as the one that originated in the US two years ago’ (p. 12) and that it presents ‘for Europe, a chance to become more fully integrated’. (p. 16).

The initial attempts of the Greek government were not sufficient to persuade its peers until the first signs of the spread of the crisis on a European level could be spotted (Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Rompuy, Citation2014; Sarkozy, Citation2020). It was not until April 2010, when the spread costs of the Portuguese bonds began to rise that the Greek argument persuaded its former militants (Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Inman & Traynor, Citation2010; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Sarkozy, Citation2020). Quoting interviewee 1, ‘At this point, what was seen as a Greek crisis, now was considered to be a European’. It is in this light that the Greek narrative about the formation of a European support mechanism as a solution to crisis contagion resonated with its previous critics. German Finance Minister Wolfgang (Schäuble, Citation2010) went as far as stating: ‘Don’t test the consequences of a euro country's insolvency’ and ‘the member states of the eurozone will act decisively and in a coordinated manner if the stability of the euro as a whole is at risk’. This is echoed in the authorised biography of Angela Merkel, which states that the crisis in Spain and Italy showcased that ‘the problem was not only one of debt but that the Eurozone had a major flaw in its construction that could not be remedied by pouring in money’(Kornelius, Citation2013, p. 158). In effect, it was the risk of crisis contagion that led the European leaders, quoting French president Sarkozy, to ‘fight speculators’ and their ‘attack on the whole eurozone’ through the formation of a European mechanism (Charlemagne, Citation2010). The above is verified by the recount of interviewee 3, who states that: ‘only when it was clear that Greece could be contagious and that Spain, Portugal or even Italy could be next, the European leadership and especially the French and the Germans accepted the inevitability of a forward-looking institution like the EFSF’.

The examination of the empirical evidence showcased suggests that the coupling of the entrepreneur's proposal with the crisis-induced policy window persuaded the European leaders to create a European mechanism. However, it can only be considered part of a wider process initiated by the entrepreneur since it did not directly lead to the creation of the EFSF. At this point, the organisational structure and functional status of the potential mechanism were yet to be determined.

4.2. The legal ‘Scylla and Charybdis’

On the 7th of May 2010, the EU leaders convened in an unofficial Council meeting as they were eventually persuaded about the need for a European stability mechanism. Nonetheless, there were two legal hurdles that had to be surpassed for the formation of a European mechanism. These were article 122 and the combination of articles 125 and 126 of the TFEU. These legal hurdles would shape the function of what would be EFSF.

Article 122 TFEU prescribes the financial support of an EU member-state in the event of a crisis. Article 122 did not explicitly prohibit the financial support of EU member states, but until 2010 its dominant legal interpretation prescribed that a country’s economic distress should be directly caused by a crisis and not merely triggered by it (Hinarejos, Citation2013; Ryvkin, Citation2012). In the case of the Eurozone crisis, Sibert (Citation2010) states in her report to the EU parliament: ‘it is difficult to argue that the severe difficulties faced by some member states were akin to being hit by hurricanes or earthquakes, rather than being mostly of their own making’. Despite this long-term interpretation, the European leaders opted to stick to the boundaries set by the lexical formulation of the treaty's provision and used article 122 of TFEU as EFSF's legal foundation because they could not bypass it (Council of the European Union, Citation2010a; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Papandreou, Citation2021). It is worth noting that while the EFSF's legal basis was never successfully questioned, the European leaders felt compelled to revise TFEU before establishing the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the successor of EFSF (Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Rompuy, Citation2014).

The second legal hurdle refers to articles 125 and 126 TFEU, which contain the no bail-out clause. The no bail-out clause prohibits any EU entity, be it a member-state or institution, from assuming the debt of another (article 125) and mandates that each member-state must be fiscally responsible (article 126) (TFEU, Citation2008). Thus, no direct money transfers or debt transactions were possible, and even if these restrictions were circumvented, it would be politically and legally unacceptable to finance the debt of economically imprudent countries (Hinarejos, Citation2013; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Rompuy, Citation2014; Ryvkin, Citation2012). The boundaries set by these two provisions did trigger path dependencies which shaped the function of EFSF.

The prohibitions prescribed in article 125 moulded the type of the institution to a facility issuing loans. In this manner, no financial hand-outs were issued, and the lending countries of the Eurozone would not assume the debt of the debtor countries since the assistance provided would have to be returned with interest. Thus no direct bail-out would take place (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Rompuy, Citation2014; Ryvkin, Citation2012; Schäuble, Citation2011). Moreover, alternative solutions proposed at the time, such as the mutualisation of European debt through ‘Eurobonds’, were quickly discarded as they ran contrary to TFEU provisions (Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Sarkozy, Citation2020). Characteristically, Papandreou (Citation2021) narrates, ‘I eventually went for a Stability Mechanism even though I initially argued for a Green-Eurobond, because back then this was considered to be outside the EU legal framework’.

Similarly, article 126 of TFEU affected the function of the loan facility. More specifically, any form of financial assistance would run contrary to the European legal framework requiring the fiscal responsibility of EU member states (TFEU, Citation2008). Unconditional assistance would signify that regardless of the economic malpractices of the EU member states, the Union would step in to save them (European Central Bank, Citation2011; Kornelius, Citation2013; Ryvkin, Citation2012). This would render article 126 null and void. The solution to this problem was the issuance of loans under the auspices of strict conditionality (Council of the European Union, Citation2010b; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Rompuy, Citation2014; Schäuble, Citation2011). The term conditionality refers to the enforcement of structural reforms by the debtor country as a precondition for each loan instalment. These structural reforms were supposed to mend the causes of the crisis in the receiving countries, and therefore the would-be EFSF programmes would abide by article 126 (Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Rompuy, Citation2014; Ryvkin, Citation2012; Schäuble, Citation2011).

It is important to highlight that within those legal boundaries, institutional solutions other than a Financial Stability Mechanism were viable. An example of the above is the provision of bilateral loans or the creation of a European debt managing agency (Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Leterme, Citation2010). However, these solutions were not supported by an institutional entrepreneur and never made it to the Council's agenda (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023). According to Papandreou (Citation2021), no solutions were proposed because ‘they wanted to scapegoat the problem. If they [the European partners] had initially perceived the crisis as a European problem, then everyone would have to propose their solutions, but when there was time, they didn't’.

4.3. Sealing the contagion aeolus bag through EFSF

In their extraordinary Council meeting on the 9th of May 2010, the EU leaders, having resolved the legal concerns, settled the specificities of the function and organisational structure of the new institution. These decisions were made under conditions of extreme pressure and uncertainty, as the EU leaders needed to resolve these issues before the financial markets opened in the morning. Interviewee 1 (2021) offers us a glimpse of the decision-making environment; ‘the leaders were receiving calls, saying you need to hurry, Tokyo is open, Sydney is open … ’. It is in this context that the EU leaders decided the intergovernmental nature of the EFSF and the implication of the IMF as a Junior partner.

The intergovernmental nature of EFSF was underpinned by two factors. First, the EU Council member-states believed that their decision-making power as represented in the Council should be transmuted to the EFSF because ‘ … the member-states are not outside of it (the EU) but form its constituent parts’ (European Council, Citation2010). This is validated by the interviews with Interviewee 2 (2021), stating that ‘the Council wanted to ensure that the mechanism would be controlled by the existing power configuration, where the member-states are the unchecked decision makers’. The EU Council, in effect, states that the power-wielders in the Union are the member states, and this should be reflected in any new institution with a critical decision-making mandate (European Council, Citation2010; Kornelius, Citation2013). This is further corroborated by the IMF side as ‘in the semi-formal and informal communique with the Europeans, they were adamant – we are putting our money in, and thus, we need to have control’ (Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023).

A second contributing factor to the intergovernmental nature of the EFSF was uncovered during the interviews and referred to the mistrust of the Council towards the Commission. Characteristically, interviewee 1 (2021) claimed that ‘the Council held the Commission in contempt’. This mistrust was caused by what was perceived by the Council members as ineffective Commission practices with regard to its mandate to fiscally oversee the EU member states. More precisely, the Council thought that the Commission had assumed a lenient overseeing mentality, which led to the aggravation of the crisis (Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023). Papandreou (Citation2021) narrates: ‘I told Barroso (the sitting president of the Commission) ‘where were you the last five years? Had you been strict with the previous government, Greece would not have this problem now. You covered for Karamanlis (the previous Greek PM)’. It is important to underscore that this manifestation was not included in my expectations and does not fit into the prescribed theoretical framework, something that I will elaborate on in the discussion which follows.

The IMF's implication as a Junior partner to the EFSF programmes was based on two premises. The first was the shared understanding of all EU Council members and especially Germany, that the Union had no experience in handling bail-out programmes based on conditionality or the resolution of national debt crises(Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Rompuy, Citation2014). At the same time, GLF was perceived as an endeavour which enjoyed relative success and whose practices, structure and function were efficient and, most importantly, politically acceptable. IMF was an integral part of the GLF and the troika that oversaw the first bail-out programme to Greece (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Rompuy, Citation2014). These facts, combined with the time pressure described above and the need to reduce the uncertainty concerning the function of the new institution turned the attention of the European leaders to an already existing institution with relative know-how. The already existing institution in possession of such experience and mandate was the GLF which in turn contained the IMF as a partner and copied a lot of its practices. This copying mechanism resulted in the inclusion of IMF as a Junior partner to the EFSF (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023). The above was verified in my interviews with Interviewee 1, stating that ‘The Council needed the IMF because it already knew how to structure a programme, how to implement a program and how to monitor a programme; EU did not’. Interviewee 2 narrates that ‘the Germans insisted in the inclusion of the IMF in EFSF as a sequence to their insistence for the Fund's inclusion in the GLF. They believed that Europe was inexperienced in dealing with such a crisis and there was no time for experimentation’. These sentiments are echoed from the IMF side, with interviewee three stating that ‘the Europeans pushed the IMF to participate to the degree that we had to change the Fund's constituting treaties. They considered our participation vital as they did not have previous experience with the implementation and oversight of such large fiscal consolidation programmes. Our inclusion in the EFSF was perceived as an extension of the GLF programme both by ourselves and the Europeans. The reason why we engaged in the Greek crisis was the danger of a second global economic crisis through the destabilisation of the Eurozone. This danger was still there’.

The IMF partnership as a result of path dependencies, concluded a process which was triggered by the entrepreneurship activity of the Greek government and resulted in the creation of EFSF, an intergovernmental European Institution, issuing loans based on conditionality. The empirical evidence demonstrates that the process broadly corresponds to my theoretical expectations. The role and strategies of the entrepreneur are present in the analysis above, as expected. At the same time, the empirical evidence provides support for the effect of path dependencies in both pre-moulding the entrepreneur's proposal and shaping the final function and organisational structure of the new institution. However, the empirics beheld surprises which escaped my theoretical expectations. This is related to the Council's distrust towards the Commission being a contributing factor to the intergovernmental nature of the EFSF. The relevance and systematic review of all the above is discussed in the following section.

5. Discussion

The examination of the empirics uncovers the effect of the entrepreneur in triggering the process leading to European institutional change. The process itself to a significant extent mirrors my theoretical expectations. First, the entrepreneur triggered the process through the conception and tabling of their proposal, which was espoused by the decision-making body after it was framed as a loss-minimization solution. Subsequently, the function and organisational structure of the new institution were moulded by path dependencies. However, the data gathered also presented an unforeseen factor, the relevance of which needs to be assessed. This refers to the contempt of the Council towards the Commission as a contributing factor to the intergovernmental nature of the EFSF. In this section, I reflect on the above and attempt to deduce the broader mechanism linking the entrepreneur and European crisis-induced institutional change.

To begin with, the entrepreneur was necessary for both the triggering of the process and the choice of a specific path of institutional change. This is displayed by the fact that both the call for a European lender of last resort, which was eventually implemented and that of a European debt managing agency that was overlooked was on the table prior to the Greek government's entrepreneurship attempts(Gocaj & Meunier, Citation2013; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Papandreou, Citation2021). On the one hand, the bypassing of solutions that were not supported by an entrepreneur suggests the deciding factor among various paths of institutional change is the institutional entrepreneur. On the other hand, the disregard of the EU for the idea of a European solution, when communicated by the IMF, provides support for the enabling conditions of institutional entrepreneurship discussed in the theoretical framework (Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023).

More concretely, a proposal of change must be championed by an actor with the motivation to pursue change and de-jure access to an institution's decision-making body to make it into the agenda (Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009; Dimaggio, Citation1988). In 2010 the Greek government was such an actor with the motivation to create a new institution to safeguard its economy and access to the European Council (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; TFEU, Citation2008; Papandreou, Citation2021). This motivation is evident in the Greek formulation and international communication of a concrete institutional change proposal that took into consideration potential institutional limitations. The latter is highlighted by the overlooking of the ideal solution for the Greek government, which was the issuance of a green Eurobond (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Papandreou, Citation2021). The empirical evidence suggests that the Greek government felt limited by the provisions of article 125 of TFEU, and this is the reason it opted for a loan-issuing institution instead of a Eurobond (Papandreou, Citation2021). This perceived limitation of the Greek government echoes my theoretical expectations, and the entrepreneur's proposal is pre-moulded by existing path dependencies (Esping-Anderson, Citation1990; Pierson, Citation2000; Streeck, Citation1992).

However, the analysis showcases that the support of the entrepreneur is not a sufficient condition for institutional change. Despite the Greek support, the EU member states rejected the idea of a European mechanism until the Greek government framed its creation as the best solution to limit the European-wide contagion of the crisis. This framing had to be coupled with the first signs of crisis contagion to force EU leaders into action (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Rompuy, Citation2014). The unwillingness of the EU member-states to support the Greek proposal until they perceived the Eurozone crisis as such provides support for three theoretical bedrocks of the paper. First, the spread of the crisis on a European level acted as a policy window and second that this policy window was a prerequisite for the entrepreneur's proposal to be contemplated as a solution (Ackrill et al., Citation2013; Kingdon, Citation1995; Zahariadis, Citation2008). Finally, the adoption of the Greek argument that the creation of a European institution would halt the crisis contagion by its critics suggests that the loss-minimization framing tactic enjoys significant chances of success (Zahariadis, Citation2008).

Once the entrepreneur's proposal enjoys the support of the member states over potential alternatives, the discussions about the new institution's actual function and organisational structure commences. Thus, the scope of the acting entity shifts from the entrepreneur to the responsible decision-making body.

The decision-making body, in this case, the European Council, needs to determine the function of the new institution. In doing so, it is delimited by the structural bonds of the existing treaty provisions (Esping-Anderson, Citation1990; Hogan, Citation2006; Pierson, Citation2000; Streeck, Citation1992). These bonds relax thanks to the crisis scope condition, which creates a critical juncture within which the formation of a new institution is possible(Hogan, Citation2006; Pierson, Citation2000). The piece-by-piece examination of the empirical evidence uncovers that the Eurozone crisis relaxed but did not vanish these institutional constraints, setting the extreme institutional confine at the literal meaning of article 122 of the TFEU. The persistence of these limits is observable through the EU leaders need to set a legal basis derived from TFEU for the EFSF and their choice to include article 122 as such on the official Council proceedings (Council of the European Union, Citation2010a; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023). The revision of the treaties prior to the establishment of the ESM, the permanent institution created after EFSF, shows that in the crisis’ aftermath, the institutional bonds recovered their interpretational layer, and EU leaders revised TFEU to extinguish any doubt about the legality of the mechanism (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Rompuy, Citation2014). This fluctuation, yet retainment of the perceived structural boundaries of the Union, allows the inference that the Eurozone crisis acted as a critical juncture (Hogan, Citation2006; Pierson, Citation2000).

Within a critical juncture, persisting limitations trigger path dependencies screening the potential solutions and excluding those violating them (Esping-Anderson, Citation1990; Streeck, Citation1992). Thus, the entrepreneur's proposal must fall within the path dependent institutional boundaries. If the proposal is consistent with existing path dependencies, it is then further moulded by them. In this case, the entrepreneur managed to exploit the window of reform opened by the critical juncture because they heeded the persisting path dependencies and pre-moulded their proposal according to the limitations posed by them. Thus, the institutional change mechanism progresses to its next phase, the final design of the new institution's function and structure based on pre-existing path dependencies.

In this context, the empirical evidence suggests that the EFSF conditionality function was determined based on the path dependency feedback mechanism, which conditions actors to specific perceptions about what is possible through institutional deterrents (Esping-Anderson, Citation1990). The analysis highlights that in the case of the EFSF, the institutional deterrent was the no bail-out clause of 126 TFEU. The EU leaders included the provision of conditionality as an explicit means to abide by article 126 TFEU (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013; Papandreou, Citation2021; Rompuy, Citation2014). This shows support for the theoretical assumption that the functional specificities of the entrepreneurship-originating institution will be further moulded by path dependencies.

Once the functional specificities of the new institution are set, the decision-making body decides on the organisational structure of the new institution. The organisational structure of the new institutions is shaped by both theoretically expected and unforeseen factors.

To begin with, the inclusion of the IMF as a junior partner in the EFSF structure echoes one of my theoretical expectations. More precisely, it suggests that in times of uncertainty, copying path dependencies will lead policymakers to scavenge the organisational structure of existing institutions (Verdun, Citation2015). In this case, decision-making under conditions of Eurozone crisis-induced uncertainty, in combination with the absence of ‘know-how’ within the EU, mandated the copy of the prototype from an already existing organisation. This organisation was the GLF, to which IMF was a junior partner, and its inclusion was perceived as a guarantee for the success of the conditionality-based programmes (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013). In order to ensure the new institution’s smooth function and keeping in mind that Europe had not attained the necessary experience in the handling of conditionality-based programmes, the European leadership copied GLF’s structure and included the IMF as EFSF’s junior partner.

The intergovernmental or supranational organisational structure of the new institution is influenced by power-related path dependencies, as expected (Hanrieder, Citation2015; Skocpol, Citation1992). The empirical evidence uncovers that the decision-making body will aspire to entrench its authority over others by transmuting its modus-operandi to the new institution. In this case, the data gathered verify that the Council aspired to further its institutional reach by instilling an intergovernmental organisational structure in the ESFF (European Council, Citation2010; Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation3, Citation2023; Kornelius, Citation2013).

The intergovernmental nature of the EFSF, according to the empirics, was further influenced by another unexpected factor, namely, the contempt of the Council towards the Commission (Interviewee Citation1, Citation2023; Interviewee Citation2, Citation2023; Papandreou, Citation2021). This finding does not fit in the theoretical framework discussed above. It rather seems to be compatible with the theoretical element of organisational cultural contestation. Organisational cultural contestation refers to the divergent managing attitudes between different bodies of the same organisation, which lead to competition between them. This competition can be manifested as a struggle related to the functional and managing culture of a new Institutional apparatus in the Organisation (Finnemore & Sikkink, Citation1998). It is unclear whether this finding could claim generalizability or whether it is a case-specific particularity. However, the long academic debate of intergovernmentalism versus supranationalism in the EU, indicates that the theoretical element of organisational cultural contestation could be an integral part of the causal mechanism. Thus, I include it in the broader causal mechanism until future studies prove otherwise.

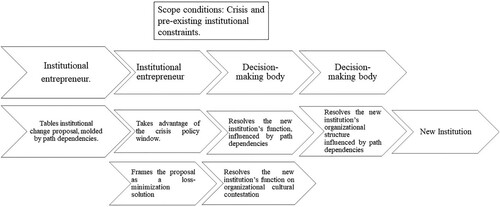

Overall, the case of Greece and the EFSF, to a significant extent, provides supporting evidence for the mechanism envisioned in the theoretical framework. More concretely, Greece acted as an entrepreneur and triggered a process which produced a new institution, the EFSF. The proposal of the entrepreneur, the function and the structure of the new institution was moulded by path dependencies. However, the empirics suggest that the mechanism in question could be complemented by the theoretical concept of organisational cultural contestation. The theoretical framework discussed three specific feedback mechanisms all of which manifested in the present case study producing the relevant path dependencies. I need to clarify that I do not claim that the path dependencies shaping the entrepreneur’s proposal, the function and the structure of a new institution will be the result of these specific feedback mechanisms or that they will appear in the exact same order. The argument in place is simply that the above-mentioned elements will be shaped by path dependencies. This is the reason-why in that follows and summarises the crisis-induced institutional change mechanism; the activities in steps one, three and four of the mechanism reference path dependencies and not a depiction of specific feedback mechanisms.

6. Conclusion

In my attempt to bridge the structure versus agency split of historical institutionalism and institutional entrepreneurship literature, I conducted an in-depth single case study to answer the following research question: What explains the formation of EFSF? My theoretical expectations accompanying the research question and covering the relative gap were that in conditions of crisis, the entrepreneur triggers a process of institutional change through its proposal. This proposal is further moulded by path dependencies which shape the function and organisational structure of the new institution. More concretely, I argued that the proposal enjoys chances of success thanks to a crisis-induced critical juncture. During this critical juncture, the structural bonds of historical institutionalism relax but do not evaporate. Thus, the entrepreneur has more leeway with regard to the nature of their proposal but is not completely unrestrained as institutional entrepreneurship literature would suggest. In this context, the entrepreneur formulates their proposal taking into consideration the persisting path dependencies. Once the entrepreneur chooses a path forward, the specificities regarding the structure and the function of the new institution are further moulded by path dependencies.

The explicit answer to the research question above is that the Greek government, through its proposal of a European financial stability mechanism, kickstarted a process resulting in an increase in the EU's institutional density and the formation of EFSF. The process linking the Greek entrepreneurial activity and the formation of EFSF has been discussed above and to a great extent verified the mechanism of crisis-induced institutional change envisioned in the theoretical framework. The mechanism combines elements from institutional entrepreneurship and historical institutionalism literature. This results in an agent-driven historical institutionalism which acknowledges the importance of agency in crises but does not disregard the boundaries of the entrepreneurial activity posed by pre-existing structural limitations. In addition to these expected steps of the causal mechanism, the analysis indicated that organisational cultural contestation could also be a part of the mechanism. The answer to the research question at hand contributes to existing knowledge as it covers an existing theoretical gap in explaining EU crisis-induced institutional change. This is achieved through the uncovering of the mechanism linking entrepreneurial activity and institutional evolution and highlighting the boundaries of the entrepreneurial activity and the sources of those boundaries.

Parallelly, my findings function as road signs for future research. The execution of a case study, while useful in terms of theory deduction, reduces the generalizability of my findings. In this case, the novel theoretical underpinning is the combination of the institutional entrepreneurship agency with the structural limitations of historical institutionalism to explain EU crisis-induced institutional change. Future research should focus on testing whether this combination travels to other cases of EU crisis-induced institutional change. Recent events, from the covid crisis to the EU response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, offer a unique yet unfortunate opportunity to test the theoretical framework developed in this paper. Similarly, future research should test whether organisational cultural contestation is a case-specific manifestation or whether it enjoys some degree of portability across cases. The interinstitutional talks between the parliament, the Commission and the Council could serve as a testing ground for this potential aspect of the mechanism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eleftherios (Lefteris) Karchimakis

Lefteris Karchimakis ([email protected]) is a PhD candidate and a Leiden University Institute of Political Science lecturer. His research interests include the EU's crisis-induced institutional evolution, organisational adaptation and the evolution of norms and ideas in EU governance.

Notes

1 Within this paper, the term ‘Greek Government’ refers to the Greek Prime Minister and the team that, under his leadership, was tasked to solve the Greek debt crisis and negotiate the formation of EFSF. This includes multiple ministries, statal officials and technocrats who, on a political level, were represented by the Prime Minister in the European Council.

2 The interviews were conducted after written consent was obtained. The former Prime Minister opted to go on the record eponymously, while the ministers and the IMF executive board member preferred to keep their anonymity.

References

- Ackrill, R., Kay, A., & Zahariadis, N. (2013). Ambiguity, multiple streams, and EU policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(6), 871–887.

- Ansell, C., Boin, A., & Kuipers, S. (2016). Institutional crisis and policy agenda. In N. Zahariadis (Ed.), Handbook of public policy agenda setting (pp. 415–432). Edgar Elgar Publishing.

- Bakir, C., & Jarvis, D. S. L. (2017). Contextualizing the context in policy entrepreneurship and institutional change. Policy and Society, 36(4), 465–478.

- Battilana, J., & D’Aunno, T. (2009). Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. In T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (1st ed., Issue 2002, pp. 31–58). Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, A., & Elman, C. (2007). Case study methods in the international relations subfield. Comparative Politics Studies, 40(2), 170–195.

- Boin, A., ’t Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2009). Crisis management in political systems: five leadership challenges. In A. Boin, E. Stern, & B. Sundelius (Eds.), The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure (pp. 1–17). Cambridge University Press.

- Charlemagne. (2010). EU leaders vow to fight contagion in the Eurozone, details to follow on Sunday. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/charlemagne/2010/05/07/eu-leaders-vow-to-fight-contagion-in-the-euro-zone-details-to-follow-on-sunday.

- Council of the European Union. (2010a). Main results of the Council. Extraordinary Council Meeting Economic and Financial Affairs.

- Council of the European Union. (2010b). Press release, extraordinary council meeting, economic and financial affairs.

- Dikaios, G., & Tsagkroni, V. (2021). Failing to build a network as policy entrepreneurs: Greek politicians negotiating with the EU during the first quarter of SYRIZA in government. Contemporary Politics, 27(5), 611–630.

- Dimaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organizations: Culture and environment. Ballinger Publishing.

- Esping-Anderson, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press.

- European Central Bank. (2011). The European stability mechanism. ECB Monthly Bulletin, July 2011, 71–84.

- European Council. (2010). The European Council in 2010.

- Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International organization at fifty: Exploration and contestation in the study of world politics. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917.

- Fligstein, N., & Mara-Drita, I. (1996). How to make a market: Reflections on the attempt to create a single market in the European Union1. American Journal of Sociology, 102(1), 1–33.

- Garud, R., Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies, 28(7), 957–969.

- Gocaj, L., & Meunier, S. (2013). Time Will Tell: The EFSF, the ESM, and the Euro Crisis. Journal of European Integration, 35(3), 239–253.

- Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. The Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58–80.

- Haas, E. B. (1961). International integration: The European and the Universal Process. International Organization, 15(3), 366–392.

- Hanrieder, T. (2015). The path-dependent design of international organizations: Federalism in the World Health Organization. European Journal of International Relations, 21(1), 215–239.

- Hinarejos, A. (2013). The court of justice of the EU and the legality of the European Stability Mechanism. The Cambridge Law Journal, 72(2), 237–240.

- Hogan, J. (2006). Remoulding the critical junctures approach. Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 39(3), 657–679.

- Howell, M., & Prevenier, W. (2001). From reliable sources: An introduction to historical methods. Cornell University Press.

- Inman, P., & Traynor, I. (2010). Euro crisis goes global as leaders fail to stop the rot. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/may/07/euro-crisis-global-leaders-greece.

- Interviewee 1. (2023). Greek Government.

- Interviewee 2. (2023). Greek Government.

- Interviewee 3. (2023). IMF Executive Board Member.

- Keohane, R. (1982). The Demand for international regimes. International Organization, 36(2), 325–355.

- Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agendas, Alternatives, and public policies, 2nd Edition. Harper Collins.

- Kornelius, S. (2013). Angela Merkel. The Chancellor and her world. The authorized biography. Alma Books LTD.

- Kreuder-Sonnen, C. (2019). Emergency powers of international organizations: Between normalization and contestation. Oxford University Press.

- Leterme, Y. (2010). Pour une agence européene de la dette. Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2010/03/05/pour-une-agence-europeenne-de-la-dette-par-yves-leterme_1314894_3232.html.

- Machamer, P., Darden, L., & Craver, C. F. (2000). Thinking about mechanisms. Philosophy of Science, 67(1), 1–25.

- Mahoney, J. (2001). Path-dependent explanations of regime change: Central America in comparative perspective. Studies in Comparative International Development, 36(1), 111–141.

- McNamara, K., & Abraham, N. (2009). The European union as an institutional scavenger: international organization ecosystems and institutional evolution. 11th Biennial EUSA Conference, April 24-26, 2009 Los Angeles, 1–37.

- Moravcsik, A., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). Liberal intergovernmentalism. In A. Wiener, T. Börzel, & T. Risse (Eds.), European integration theory (3rd ed., pp. 64–84). Oxford University Press.

- Mosley, L. (2013). Interview Research in Political Science. In Interview research in political science. Cornell University Press.

- Niemann, A., & Ioannou, D. (2015). European economic integration in times of crisis: A case of neofunctionalism? Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 196–218.

- Nøkleby, H. (2011). Triangulation with diverse intentions. Karlstads Universitets Pedagogiska Tidskrif, 140–156.

- Papandreou, G. (2010a). Rising to the challenge of change: Greece, Europe and the United States (Discussion at Brookings Institute Transcript).

- Papandreou, G. (2010b). We need the support to implement our program. https://papandreou.gr/en/we-need-the-support-to-implement-our-program/.

- Papandreou, G. (2021). Interview 26/4.

- Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. The American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267.

- Pircher, B. (2020). The Council of the EU in times of economic crisis: A policy entrepreneur for the internal market. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 16(1), 65–81.

- Pollack, M. A. (2019). Institutionalism and european integration. In A. Wiener, T. Börzel, & T. Risse (Eds.), European integration theory (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Rohlfing, I. (2012). Types of case studies and case selection. In Case studies and causal inference (pp. 61–96). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rompuy, H. v. (2014). Europe in the storm : Promise and prejudice. Davidsfonds.

- Ryvkin, B. (2012). Saving the Euro: Tensions with european treaty law in the european union’s efforts to protect the common currency. Cornell International Law Journal, 45, 228–255.

- Salines, M., Glöckler, G., & Truchlewski, Z. (2012). Existential crisis, incremental response: The Eurozone's dual institutional evolution 2007-2011. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(5), 665–681.

- Sandholtz, W., & Sweet, A. S. (1997). European integration and supranational governance revisited. Journal of European Public Policy, 6(1), 144–154.

- Sarkozy, N. (2020). Le Temps des Tempêtes. l’Observatoire.

- Saurugger, S., & Terpan, F. (2016). Do crises lead to policy change? The multiple streams framework and the European Union’s economic governance instruments. Policy Sciences, 49(1), 35–53.

- Schäuble, W. (2010). Im Gespräch: Wolfgang Schäuble: „Erst die Strafe, dann der Fonds“ - Konjunktur - FAZ. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/konjunktur/im-gespraech-wolfgang-schaeuble-erst-die-strafe-dann-der-fonds-1954060-p2.html.

- Schäuble, W. (2011). Speech at the Walter Hallstein-Institut of the Humboldt-Universitat in Berlin.

- Schön-Quinlivan, E., & Scipioni, M. (2017). The Commission as policy entrepreneur in European economic governance: A comparative multiple stream analysis of the 2005 and 2011 reform of the Stability and Growth Pact. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(8), 1172–1190.

- Schwarzer, D. (2012). The Euro area crises, shifting power relations and institutional change in the european union. Global Policy, 3(1), 28–41.

- Sibert, A. (2010). The EFSM and the EFSF: Now and what follows. European Parliament, DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES ECONOMIC AND MONETARY AFFAIRS.

- Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers the political origins of social policy in the United States. Harvard University Press.

- Starman, A. (2013). The case study is a type of qualitative research. Journal of Contemporary Educational Studies, 1, 28–43.

- Strauch, R. (2019). Can the euro area respond adequately to the next crisis with its current instruments? | European Stability Mechanism. https://www.esm.europa.eu/speeches-and-presentations/can-euro-area-respond-adequately-next-crisis-its-current-instruments.

- Streeck, W. (1992). Social institutions and economic performance : Studies of industrial relations in advanced capitalist economies. Sage Publications.

- Swinkels, M. (2020). Beliefs of political leaders: Conditions for change in the Eurozone crisis. West European Politics, 43(5), 1163–1186.

- TFEU. (2008.

- Traynor, I. (2010, the 11th of February). Angela Merkel dashes Greek hopes of rescue bid. https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/feb/11/germany-greece-merkel-bailout-euro.

- Verdun, A. (2015). A historical institutionalist explanation of the EU’s responses to the euro area financial crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 219–237.

- Zahariadis, N. (2008). Ambiguity and choice in European public policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(4), 514–530.