?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Recent work in political economy suggests that autocratic regimes have been moving from an approach of mass repression based on violence, towards one of manipulation of information, where highlighting regime performance is a strategy used to boost regime popularity and maintain control. While the evolving strategies autocratic governments use to legitimise their rule have been the subject of much analysis, the role of third parties in adding to such strategies is less examined. This paper argues that corporations confer legitimacy on autocratic governments through a number of material and symbolic activities, including by praising their economic performance. We trace out the implications of adopting legitimation as a key concept in the analysis of corporate relations to autocratic regimes. We identify the ethically problematic aspects of legitimation, present new quantitative evidence suggesting that corporate legitimation of regimes matters empirically and outline a research agenda on legitimation.

1. Introduction

China's done an unbelievable job of lifting people out of poverty. They’ve done an incredible job – far beyond what any country has done – we were talking about mid-90s to today – the biggest change is the number of people that have been pulled out of poverty, by far. And we should all applaud that, and we should all feel good about it.

Apple CEO Tim Cook at the Fortune Global Forum, 6 December 2017Footnote1

The idea that there has been a shift among autocratic leaders to increasingly rely on information manipulation and performance legitimation over repression strategies is not uncontroversial. Przeworski (Citation2023) suggests that attempts to improve perceived regime legitimacy through the appearance of improved performance may in practice meet with little success, and Gitmez and Sonin (Citation2023) argue that information manipulation may be used as a complement rather than a substitute for repression. Moreover, the Putin regime's extensive use of repression strategies domestically and internationally could indicate that an increased prominence of informational autocrats is a temporary pattern subject to reversal or a limited phenomenon internationally (Gel’man, Citation2023). And to be clear, any shift towards information manipulation does not entail the end of the use of force, violence and intimidation by undemocratic regimes, the end of harm inflicted on their citizens. In analysing the moral obligations and role of corporations in societies governed by autocratic regimes, the concept of complicity – whether direct, indirect, beneficial, or silent – will remain important.Footnote2 However, to the extent that there has been a shift in autocratic strategies, the concept of complicity begins to seem incomplete for an ethical analysis of corporate activities. If autocrats increasingly rely on manipulation of information and boosting their apparent performance in the eyes of the population, symbolic acts by corporations and their executives which play into and make this revised strategy of autocratic governments more effective, need to be understood and assessed in terms of ethical status. In other words, we need more focus on the various ways in which corporate actors legitimise autocratic governments, adding to their moral or actual authority.

The above statement by the CEO of Apple provides an example of how a corporate executive can lend legitimacy to an undemocratic regime. In principle, the statement can be read as praise for the citizens of China for lifting themselves out of poverty. In practice, however, the statement will be read as praise for the government of China, for having enacted policies that over recent decades have led to large decreases in poverty. This is a regime that killed unknown thousands in the 1989 crackdown on protests at Tiananmen Square, that persecutes ethnic and religious minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang, and heavy-handedly suppressed political and civil rights in Hong Kong (not to mention in mainland China). It is also a regime that uses its apparent economic success for what it is worth, in shoring up regime support in China, and deflecting criticism of its human rights record abroad. The type of statement made by Tim Cook seems to play right into this strategy.

This article provides a systematic analysis of corporate legitimation of autocratic governments. While a number of studies in political science have analysed the strategies autocratic regimes employ to influence perceptions of the legitimacy of their rule (e.g. Gerschewski, Citation2013), the narratives they provide to justify being in power (Tannenberg et al., Citation2021), there seems to be much less attention to how third party activities may play into these regime legitimation strategies, including by corporations. The article makes two main contributions, one conceptual and one empirical, and use these to construct a research agenda for further work. In the conceptual part, we position our analysis in the literature on autocratic stability and regime legitimation, and elaborate on different types of corporate acts of regime legitimation, which go beyond the example of praising regime performance provided above. We argue that approaching corporate relations to undemocratic regimes through the concept of legitimation highlights commonly (and problematically) taken for granted assumptions of legitimate authority which underlie the ability of autocratic regimes to perpetrate harm. Regimes of this kind lack the substantive legitimacy which would make symbolic contributions to maintaining or increasing their perceived legitimacy acceptable. They exercise authority without the moral basis to do so, without the explicit consent of the citizens on whose behalf they act. Against this backdrop, we discuss and identify challenges in assessing the moral status of corporate acts of legitimation, in view also of the (often imperfectly discharged) obligations of other parties.

In our empirical contribution, we present new evidence on the relationship between multinational corporate activity and democracy in countries that host them, addressing the literature on foreign direct investment (FDI) and regime type. Early empirical studies of the effect of FDI or openness to capital suggested a positive (Li and Reuveny, Citation2003; Eichengreen and Leblang, Citation2008) or a conditionally positive (Rudra, Citation2005) effect on democracy. In contrast, a more recent study by Escribá-Folch (Citation2017) finds a negative association between FDI inflows and democracy, and suggests that one mechanism behind such a negative effect may be that high FDI inflows are perceived as international endorsement of a regime and its policies. Using panel data from and country and year fixed effects estimation, we probe the importance of this mechanism, in part addressing the critique that studies of the interrelationships between FDI and democracy have paid too little attention to pathways and mechanisms (Li et al., Citation2018).

More specifically, we test whether the association between FDI inflows and democracy is more negative where host country regimes rely more heavily on a performance legitimation strategy. Our results show that an overall negative association between FDI and democracy is indeed driven by a negative association in polities where regimes rely heavily on performance arguments to justify being in power, which is consistent with the idea that multinational corporations lend legitimacy to host country regimes through their investment activity, thereby reducing the chances of democracy. We stress that our analysis is descriptive; our fixed effects and time-variant covariates rule out a large set of potential confounders, but we do not claim to estimate causal effects of FDI on democracy under different regime legitimation strategies. Nevertheless, the uncovered empirical regularities represent prima facie evidence suggesting that corporations may have important legitimising effects on host country regimes, potentially playing into regime strategies of performance legitimation. Combined with the conceptual arguments of the paper, we argue that this evidence provides a strong reason to develop a research agenda further analysing corporate legitimation of autocratic regimes, which we proceed to do in our final section.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 situates our analysis in the literature on autocratic stability, and provides a conceptual discussion of corporate acts of regime legitimation and their moral status. Section 3 presents the empirical analysis of the relationship between FDI inflows and democracy. Section 4 concludes with our proposal for a research agenda on corporate legitimation activities.

2. Corporate legitimation of autocratic regimes

Legitimation is defined here as adding to the authority of an agent. In contrast to work in discourse analysis, which defines legitimation as ‘the process by which speakers accredit or licence a type of social behavior’ (Reyes, Citation2011, p. 782), our definition focuses on giving licence or accreditation to someone acting in a particular role. In other words, while the definitions are clearly related, our definition centres not on acts of justification of behaviour, but on acts of justification of the position from which someone acts or behaves. When we talk about legitimation, we refer to activities which confer legitimacy on someone, we focus on the process through which authority is added to, rather than the state of legitimacy which is the focus in management studies (Suchman, Citation1995). In line with this literature, though, legitimation is about perceptions, it entails adding to the authority of someone in the eyes of some beholder or social audience. Importantly, the concept conveys the notion that perceived legitimacy is something that we not only can possess, gain, or lose, but also something we confer on others through our activities. Activities in this sense are interpreted broadly, encompassing action and inaction, material and symbolic (including words and silence).

Strategies of legitimation have been given increasing attention in the political science literature on comparative authoritarianism and autocratic stability in recent years. In a review of the evolution of the scientific literature on autocracies, Gerschewski (Citation2013) argues that the renewed attention to autocracies that started in the late 1990s initially focused on strategic repression and co-optation (through the use of institutions like parties and elections) as major strategies used by autocrats to stay in power. To these two pillars of autocratic stability, more recent work has added a third, that of legitimation, pointing out autocratic regimes typically make some claim as to why they are entitled to rule, and that legitimation provides an alternative or a complement to costly strategies of repression (Dukalskis & Gerschewski, Citation2017; Gerschewski, Citation2013; Gerschewski, Citation2018; Tannenberg et al., Citation2021). To avoid any unfortunate connotations that autocracies can be legitimate in any normative sense, this literature focuses on the process of legitimation rather than a state of autocratic legitimacy (Gerschewski, Citation2018), largely in line with the above definition of legitimation.

Work on autocratic legitimation strategies distinguish clearly between legitimacy claims of a regime, which are empirically fairly easy to map, and legitimacy beliefs of citizens, which in an autocratic context are hard to measure accurately (Dukalskis & Gerschewski, Citation2017). As an indication that legitimacy beliefs are also a concern for autocratic rulers, avenues for consultation with and participation of citizens are sometimes provided by autocratic regimes (Gerschewski, Citation2018). Dukalskis and Gerschewski (Citation2017) argue that legitimation strategies aim to bolster regime stability and longevity through four mechanisms, with the latter two becoming more dominant in recent times; (i) ideological indoctrination of the population, (ii) inducing passivity and apathy through displays of power making the rule of the regime seem inevitable and impervious, (iii) highlighting performance of the regime in terms of order, stability and growth and (iv) a democratic-procedural mechanism through which heavily manipulated democratic institutions such as elections are used to give an appearance of democratic legitimacy. Building on these mechanisms, Tannenberg et al. (Citation2021) propose four distinct forms of legitimation strategies by autocrats as based on (i) ideology, (ii) the person of the leader, (iii) rational-legal procedures and/or (iv) performance.

Case studies and comparative work has been conducted to assess the forms and importance of legitimation strategies and legitimacy to autocratic stability or instability and popular resistance (see e.g. Thyen & Gerschewski, Citation2018). The concept has also been applied in studying transnational autocratic strategies, where strategies of repression, co-optation and legitimation are used to stem criticism of autocratic regimes from abroad (Tsourapas, Citation2021). What has so far attracted less systematic attention, is third-party legitimation of autocratic governments. This can include actions by private individuals, other governments, international organisations, civil society organisations and corporations that directly legitimise or play into the legitimising strategies of autocratic governments.

Here we focus on the actions of corporations and corporate leaders, who through their power and position in particular when it comes to large multinational corporations, can have a substantial influence in this respect. While corporations could in principle influence autocratic legitimation based on ideology or the person of the autocratic leader, we argue that given the centrality of corporations in the legal-economic system and in providing the capital and technology to generate growth, their role in legitimising regimes through actions that play into legitimation efforts based on rational-legal or performance arguments, deserve attention. One aspect of this is the sheer size of some of the larger corporations in the world, with revenues greater than many countries (Babic et al., Citation2017), but this may be especially relevant when size is combined with visibility as for consumer brand companies. This also ties in with the idea from Bourdieu (Citation1977) that material capital can be converted to symbolic capital. Moreover, while the apolitical company is a myth (Frynas, Citation2005), corporations sometimes attain an appearance of being technical rather than political, which may set them apart from other more political third parties. These aspects speak to the capacity of corporations to legitimate political regimes, in addition, their interests may in certain cases be more aligned with those of the ruling elite of a country than with the population (Wiig & Kolstad, Citation2010) giving them an incentive to legitimise governments.

In the following, we distinguish four forms of legitimation by corporations:

Acceptance of the formal authority of an agent

Submission to the power of an agent

Accepting or condoning the goals set by an agent

Praising the performance or results of an agent

Below, we elaborate in more detail on ways in which corporations may engage in these forms of legitimation and discuss the implications thereof. The first three forms highlight how corporations in certain cases add to the rational-legal legitimation strategies of regimes, the fourth form returns to the question of performance legitimation raised in the introduction. While the literature on autocratic legitimation strategies draws a useful distinction between a positive analysis of which strategies autocrats actually use, and a normative analysis of the more fundamental issue of regime legitimacy, we believe that in discussing the role of corporations it is necessary to also discuss the normative status of their activities in relation to regime legitimation. Notably, the commonalities of the four forms allow us to identify the reasons why and instances in which these practices become morally questionable.

A first form of legitimation is the acceptance of the formal authority of an agent. Importantly in our case, this includes the acceptance of formal authority to act as the representative or on behalf of a client or a population. In typical business interactions with a third party through a middle-man or agent, the legitimacy of the interaction is commonly premised on the agent having the consent of the third party to act on their behalf. The agent in other words has a form of substantive legitimacy in acting on someone else's behalf, primarily based on consent. It is a disconcerting feature of international politics that government and companies tend to routinely enter into interactions with, and hence accept the formal authority of, governments that do not have any mandate from the population to act on their behalf, that lack any form of substantive legitimacy. It is pretty clear that autocratic governments rule without the explicit consent of their citizens, and therefore lack substantive legitimacy to act on their behalf. In any other context, we would call acting on behalf of a client whose consent you do not have to do so, fraud. Nevertheless, corporations routinely accept them as contract partner, as borrower, as levier of taxes, as regulator and as resource extractor. The dubious claims of such regimes to act on behalf of their population have been noted in the international relations literature with respect to international borrowing (Pogge, Citation2001) and resource extraction (Wenar, Citation2008). One implication of these observations seems clear; if acceptance of formal authority confers legitimacy, there is no meaningful way we can say that corporations can stay out of politics. The precise implications for corporate obligations may not be as straightforward; for instance, how should a multinational corporation act towards an autocratic government that its own home government accepts as an economic partner? That this need not be an easy discussion, however, does not imply that it is unimportant. And the point remains; accepting the authority of an agent to act on behalf of others is a form of legitimation.Footnote3

A second form of legitimation is to submit to the power of an agent. This is similar to the first form, insofar as it entails acceptance of the authority of the agent to act on behalf of others, but here the focus is on the authority to punish rather than enter into transactions. It is widely noted that while government trade sanctions imposed by democratic countries have had limited effectiveness, they are increasingly employed for foreign policy purposes by undemocratic regimes, and to some effect. In the case of China, trade sanctions imposed on countries receiving the Dalai Lama at a political level have reduced exports from these countries to China (Fuchs & Klann, Citation2013), and sanctions against Norway after the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize to the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo significantly reduced exports to China and may have shifted Norwegian foreign policy (Kolstad, Citation2020). Similar sanctions tactics have more recently been used against Canada after the detention of Huawei chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou and against Lithuania after the opening of a de facto Taiwan embassy in the country. These kinds of sanctions are often met with calls from the business community to normalise political relations, which essentially translates to recognising the sanctioning autocratic government as an appropriate party to engage with in these forms of disputes. Given the lack of substantive legitimacy in inflicting punishment on other countries on behalf, and to the detriment of, their own population, questions can again be raised about this type of response. These kinds of situations are no doubt challenging to the companies involved, and there is again a need to take the discussion of what obligations they have given that their home government also plays an important part. But in principle, companies can be influential parties in this kind of situation. As seen from past sanctions, their effect can be undermined in creative ways including by relabelling goods and shipping them through third countries. In relation to sanctions from regimes that lack substantive legitimacy, further analysis of the conditions under which sanctions busting is appropriate (and perhaps even required), would seem an important avenue to pursue.

Accepting or condoning the goals set by an agent is a third form of legitimation. Autocratic governments actively use rhetoric stressing threats to public order, a breakdown of the rule of law, sectarian violence and chaos, in the event that the regime is challenged or overthrown (Edel & Josua, Citation2018; Heydemann & Leenders, Citation2011). Protests are cast as a threat to security and stability, and protestors as terrorists or foreign agents, with the regime portrayed as a keeper of the peace (Dukalskis, Citation2015). These strategies were evident in local and central government responses to the 2019 protests in Hong Kong. There are various ways in which companies and other governments can respond to these situations. One is to stress the rights and liberties of the protestors. Another more problematic option is to express concern for the conflict, call for a de-escalation of the violence (from both sides), and a return to order and stability. While this may be the product of genuine concern for human safety, it risks playing into the autocratic regime's reframing of protests and opposition as a security issue, implicitly accrediting the regime's authority to prioritise goals of security and stability on behalf of their population. Again, these may not be easy situations to navigate, but statements congruent with goals set by autocratic governments without substantive legitimacy to set such goals on behalf of their citizens at the very least require critical consideration.

The fourth and final form of legitimation we discuss here is praise of the performance or results of an agent. This brings us back to Tim Cook's praise for the Chinese government in lifting people out of poverty. It should be noted that this is not a singular case, there are many examples of praise for autocratic regimes in international politics and also in business.Footnote4 As noted in the introduction, this form of symbolic legitimation plays directly into a strategy autocratic regimes increasingly use to justify their position of power. The fundamental problem with these kinds of statements is that they accord licence to an autocratic government to decide and enact policy without having any explicit mandate from their citizens to do so. As with the other forms of symbolic legitimation discussed above, these types of activities are ethically problematic as they increase the perceived legitimacy of agents who do not have the substantive legitimacy to act on behalf of their population. They add to the authority of governments whose moral basis for exercising power is flimsy or absent.

To date, much of the discussion of the role of multinational corporations in autocracies has focused on questions of their complicity in repression or their role in (economic) co-optation. The preceding elaboration should make clear that using the concept of legitimation shifts the focus on corporate relations to autocratic regimes. Legitimation highlights authority, acts of justification of the position from which someone acts or behaves, while complicity tends to focus on the actions themselves. In particular, the above forms and examples of symbolic legitimation highlight authority to act on behalf of others, and the extent to which it has a substantive basis or not. The focus on authority means that we focus more on power and on the positions from which harm is done, which leads directly to questions of accountability of governments and the role of corporations in its continued absence.

The extent to which a symbolic or material corporate action leads to increases in the perceived legitimacy of an agent's position of authority will of course vary with both who performs the action, and in what context. Ultimately, the effect of a particular activity on the perceived legitimacy of an agent is an empirical question, and an understudied one in the context of our discussion of corporate – government relations. In theory, however, the effect is likely to depend on the authority and inferred motives of the person or entity performing the act. The CEO of Apple is likely to have more of an effect on perceptions than the CEO of a company that is smaller, less visible and lacks knowledge of China. On the other hand, to the extent that a CEO's actions are perceived as self-serving, this may paradoxically reduce the impact on perceptions of regime legitimacy. Legitimising actions are also likely to have more of an effect the less the social audience has access to alternative sources of information. Moreover, these kinds of actions are likely to be more problematic in relation to performance oriented autocratic regimes (a point we return to in the next section), where results are actively and effectively used to motivate continued rule of the government, or in situations where anti-democratic forces are actively challenging the record of a democratically elected government. The gravity of legitimising activities hence depends on who has the potential to affect whose perceptions towards whom. While this is a matter of degree, even adding to the authority of an agent in more minor ways may be morally problematic, or may at least warrant ethical assessment.

3. Multinational corporations, regime legitimation strategies and democracy

3.1. Background

The fundamental takeaway from the above argument is that adding to the authority of an agent that lacks substantive legitimacy to act on behalf of others is problematic. But how important are the activities of multinational corporations in this respect? To what extent do their presence and activities serve to bolster the political position of a regime, with negative effects for democracy? Multinational corporations do help to build or deliver the symbols autocratic regimes rely on to boost their perceived legitimacy, such as skyscrapers and sports events, which can be problematic in itself. But to assess the extent to which these activities have a negative effect on regime accountability in autocratic states, we would ideally have to perform an analysis on their impact on citizen perceptions of regime legitimacy. Given the challenges inherent in collecting accurate survey data on such issues in repressive autocracies (Dukalskis & Gerschewski, Citation2017), this type of empirical analysis is difficult to conduct.

In what follows, we instead employ a more indirect empirical strategy to assess the effects of corporate legitimation activities. Several studies have argued that high foreign direct investment inflows generally may increase the popular legitimacy of regimes, that being attractive to foreign investment ‘may be interpreted as a form of international endorsement and recognition of the regime's policies’ (Escribá-Folch, Citation2017, p. 65). If this is the case, this suggests a negative link between FDI inflows and democracy in host countries, a relationship that should become more negative the more a regime relies on performance arguments to justify its hold on power. In our empirical contribution, this is what we test.

In theory, multinational corporations may undermine democratic institutions in many ways, including through corruption, increased scope for patronage and repression, risk of civil conflict or foreign intervention (Dube et al., Citation2011; Guidolin & La Ferrara, Citation2007; Shaxson, Citation2007; Wiig & Kolstad, Citation2010). On the other hand, multinational corporations may improve chances of democracy through increased income, diffusion of norms and empowerment of agents in a country that can hold a government accountable (see Escribá-Folch (Citation2017) for a comprehensive summary of these arguments). While these effects are much debated, the empirical literature that attempts to estimate the impact of FDI on democracy is surprisingly limited. By comparison, more studies have been conducted on the reverse impact of democratic institutions on a country's attractiveness to FDI (Asiedu & Lien, Citation2011; Li et al., Citation2018; Li & Resnick, Citation2003; Mathur & Singh, Citation2013).

An early study by Li and Reuveny (Citation2003) found a positive association between FDI and democracy, but their analysis faces a number of methodological challenges which make the results difficult to interpret. In particular, the use of pooled estimation leaves open the possibility that the results are driven by unobservable country characteristics, and the inclusion of trade in the specification seems inappropriate given that trade is highly endogenous to FDI. Rudra (Citation2005) finds a positive effect of gross capital inflows on democracy conditional on an increase in social spending providing a safety net that averts instability and generates political support for financial openness. In including country and time-fixed effects, this study is more methodologically convincing, but disaggregated results for FDI flows are only discussed as insignificant but not reported in the paper. A similarly methodologically more convincing empirical study is conducted by Escribá-Folch (Citation2017), who finds that FDI reduces chances of democracy by reducing the likelihood of democratic transitions. In a more recent contribution, Kim (Citation2022) finds a positive effect of non-primary sector FDI on democratic survival, but as the analysis only permits region fixed effects and depends on an instrumental variable that can be questioned, the question of how to interpret this association is left open.

Our empirical analysis adds to these previous studies by explicitly testing whether FDI has more of a negative effect on the degree of democracy in autocratic countries with regimes that use performance as a strategy of self-legitimation. In other words, our study looks into a possible form of heterogeneity in the impact of FDI on democracy, that is consistent with multinational activity having a legitimising effect on autocratic regimes. Our analysis has been made possible through the recent compilation of data on regime legitimation strategies under the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project, which contains a variable measuring performance legitimation (described more closely in the next section). This allows us to test whether any negative overall association between FDI inflows on democracy is mainly driven by a negative effect in countries whose regimes score high on the performance legitimation index. In the following subsections, we describe in more detail the data we use and our empirical strategy, before presenting and discussing our results.

3.2. Data and empirical strategy

Definitions and descriptive statistics for the variables used in our analyses are presented in Tables A1 and A2 in Appendix 1, respectively. Our main dependent variable, Democracy, is the Regimes of the world index from the V-Dem dataset, which classifies countries as a closed autocracy (value 0), an electoral autocracy (1), an electoral democracy (2), or a liberal democracy (3). We restrict our sample to autocracies, so in practice our dependent variable is a dummy variable for closed versus electoral autocracies. In additional analyses, however, we show that our results are robust to using the revised combined polity score from the Polity IV dataset as the dependent variable.Footnote5

Our base specification is captured by the following equation:

(1)

(1) In other words, we use a standard fixed effects estimation that includes both country i fixed effects

and year t fixed effects

. Our main independent variable is net foreign direct investment inflows in 1000 constant 2010 US dollars, which we normalise by dividing by populations size (which we also do for the other economic covariates).Footnote6 The vector

contains additional time-variant covariates. These include the main time-variant determinants of democracy discussed in the relevant literature. GDP per capita is included to reflect the large literature on the modernisation hypotheses due to Lipset (Citation1959), a hypothesis challenged by the results of Acemoglu et al. (Citation2008) which suggest that the association between income and democracy is due to other unobserved characteristics of countries. Informed by the extensive literature suggesting that industrial concentration in general (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2018) and natural resource rents specifically (Aslaksen, Citation2010; Caselli & Tesei, Citation2016; Ross, Citation2001; Tsui, Citation2011) have detrimental effects on the probability of democracy, we include oil and gas rents per capita in our covariates. Based on the literature suggesting that democratisation occurs in waves (Huntington, Citation1991), spreading among countries that are geographical neighbours, we include the average level of democracy in countries whose capital is within 4000 km of the capital of each country in our sample. We also include civil and interstate war as covariates, defined as in the study of Escribá-Folch (Citation2017) with zero values indicating no war, a value of one a low-intensity conflict, and a value of two a high-intensity conflict with more than 1000 yearly casualties.

Our focus is on the association between FDI inflows and democracy, as reflected in the parameter. Our main research question is whether there is a more negative effect of foreign investment activity on levels of democracy under regimes that rely more heavily on performance legitimation strategies to justify staying in power. To this end, we employ an index of Performance legitimation from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset, which rates the extent to which a government refers to performance to justify the regime in place. On this index, countries are ranked by country experts on an ordinal scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (almost exclusively).Footnote7

In estimations, we use this index in two ways that entail slightly different interpretations of results. Firstly, we split the sample into low-performance legitimation regimes (0–2 on the Performance legitimation index), and High-performance legitimation regimes (3–4 on the index; 3 also being the median value on the index in our sample), and estimate Equation (1) separately for each sub-sample. The results tell us whether FDI tends to have more of a negative point estimate in the sample of all country years with regimes that use performance legitimation extensively to justify being in power, compared to the sample where this type of legitimation is less used. Secondly, we add the Performance legitimation and its interaction with FDI per capita to Equation (1). This is to test whether the association between changes in FDI and in democracy becomes more negative in situations where there is also an increase in Performance legitimation.

We stress that while novel in the literature on FDI and democracy, our results are descriptive. The inclusion of country-fixed effects means that the uncovered associations between FDI and democracy are not driven by time-invariant differences between the countries in our sample, such as geography or history. We also cluster standard errors at the country level. Year-fixed effects similarly capture any year-specific events that change the overall level of democracy in the world. Nor are our results driven by any of the time-variant covariates included. To reduce the possibility that results are driven by reverse causality, we also lag all independent variables one period. These methodological choices notwithstanding, as both FDI and Performance legitimation are endogenous variables potentially influenced by time-variant unobservables which could also affect democracy, our results are to be interpreted as correlations, not as evidence of causal relationships.

3.3. Results

Our main results are reported in . The first column presents results from the estimation in Equation (1) on the full sample available, which includes 123 autocratic countries over the period 1971–2019. As shown in the first row, increases in FDI per capita are significantly associated with reductions of democracy levels in our sample, consistent with previous results of Escribá-Folch (Citation2017). The substantially new evidence our analysis adds, however, is highlighted by the results in columns two and three of . Here we estimate Equation (1) separately for Low-performance legitimation regimes and high-performance legitimation regimes, respectively. And the results strongly suggest that the negative association between FDI and democracy uncovered in the full sample is driven by a negative association in the high-performance legitimation sample. The relation is insignificant for the low-performance legitimation sample, but negative and highly significant in regimes that use performance extensively as justification of their power.

Table 1. Main results.

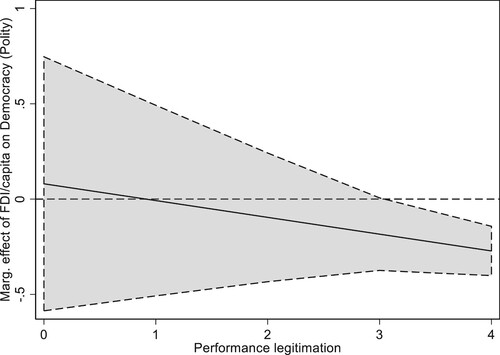

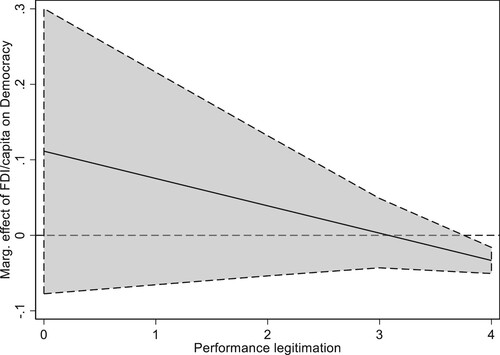

These findings are reinforced by the results presented in column four, where the Performance legitimation index and its interaction with FDI are added to the specification. The full implications of the results are traced out in , which is a plot of the effect of FDI on democracy at different levels of the Performance legitimation index. While the effect of FDI is statistically indistinguishable from zero at low values of Performance legitimation (0 through 3), it becomes significantly negative at the highest value. In other words, to the extent that FDI affects democracy negatively, this seems to be the case mainly in regimes that legitimise their power and position through their performance. In Table A3 and Figure A1 in Appendix 2, we present corresponding results using the democracy variable from Polity as the dependent variable; the results are qualitatively the same.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of FDI per capita on Democracy, by performance legitimation levels (95% confidence interval).

For the covariates, the strongest results emerge for the Neighbouring countries democratic variable, which measures average democracy levels in countries that are geographically close. The correlation here is positive and strongly significant, consistent with the literature emphasising regional waves of democratisation. Oil and gas rents per capita has a positive correlation with democracy in our sample, driven by countries with a low level of performance legitimation. While this is at odds with previous findings in the literature on natural resources and institutions, keep in mind that our estimates capture variation at the lowest levels of democracy, and that we are measuring short term effects on democracy. For the other covariates, there are few robust results of note. Income levels display no association with democracy, which on the whole is consistent with the lack of empirical support for the modernisation hypothesis found by Acemoglu et al. (Citation2008). Finally, there is little significant association between conflict and democracy in our sample.

3.4. Discussion

Multinational corporations hold a major, and in some cases dominant, position in most economies. With that position comes influence on political institutions and policy, tacitly through decisions to expand or restrict economic activities in a host country, or explicitly through lobbying and/or indue influence on a country's political institutions and organisations. The above empirical results provide initial evidence of an additional channel through which corporations can impact political institutions, i.e. through increasing the perceived legitimacy of regimes that base their power on performance-related arguments, with detrimental effects on the level and probability of democracy. Since we control for GDP per capita, our results likely pick up an effect of multinational corporation presence rather than any economic progress they may contribute to.

As noted, the above analysis is not without its limitations. Estimating the interacted effect of two endogenous variables, FDI and Performance legitimation, needs to be seen as documentation of an empirical regularity, rather than a causal effect of these variables on democracy, even if we have taken care to exclude the impact of time-invariant country characteristics through fixed effects estimation, and theoretically important time-variant characteristics through our covariates. Ideally, one should attempt to find sources of exogenous variations in both these independent variables to get at the question of causality, but that is of course a very challenging enterprise. Admittedly, the above analysis also relies on data and categorisations that are macro-level and somewhat coarse. This may in particular be the case for the Performance legitimation variable we have used, which despite extensive quality control from the V-Dem project, remains the subjective opinions of country experts. At present, however, this is the data available to work with.

Even with these caveats in mind, it seems clear that the potential legitimising effect corporate activities have on autocratic regimes should be taken seriously. These questions clearly merit further attention, and extensive research. This goes beyond the association between corporate presence and activity in the form of FDI and democracy, and beyond addressing the limitations of the above analysis. Other manifestations of corporate activity that can have a legitimising effect should be examined. And the ways and mechanisms through which corporate activities affect political institutions should be more carefully analysed. Based on the conceptual arguments made in the previous section, and the empirical evidence presented here, the following section therefore presents our proposal for a broad research agenda within which these important questions can be pursued.

4. Concluding remarks: towards a research agenda

Billions of people worldwide live under the thumb of autocratic governments, with limited say in how their societies are run, and more are at risk of doing so given the increasing economic power of autocratic regimes and their efforts to influence the institutions of other countries. To help make their situation better, and avoid making it worse, we have to understand the strategies of autocratic regimes. This also goes for corporations operating in or otherwise relating to countries with undemocratic governments. We should not add to the perceived legitimacy of regimes whose substantive legitimacy is in question. We should not play into these regimes’ evolving methods of cementing their own power and authority.

In this article, we have argued that the concept of legitimation highlights authority and positions from which acts are made and power wielded, the importance of legitimacy to act on behalf of others and accountability to them, and the role corporations play in conferring legitimacy through material and symbolic actions. In important ways, this complements conventional analysis of corporate government relations centred around the concept of complicity. It also entails a reversal of a traditional perspective in business ethics and management studies, where the focus is on how corporations gain or lose legitimacy in the contexts in which they operate (Suchman, Citation1995). We need to recognise that corporations not only acquire legitimacy, they also confer legitimacy on other parties, including governments.

An intention of this paper is for our analysis to lead up to a research agenda. We outline here three key components of such an agenda; a conceptual, a normative and an empirical part. All three would take as their point of departure the central idea that symbolic acts of legitimation are problematic where they increase perceived legitimacy in the absence of substantive legitimacy. Conceptually, though we have distinguished between four forms of symbolic acts of legitimation – acceptance of formal authority, submission to power, accreditation of goals, and praise of performance – this list is not meant to be exhaustive; there might be other forms that are important. A key concept in the analysis is that of substantive legitimacy, which we have tied to having the consent of the people you claim to act on behalf of, and which at the government level we have argued is based on democratic accountability. While autocratic governments cannot in any realistic way claim to rule with the consent of its citizens, there are nuances here with respect to how democracies are structured and what this means for substantive legitimacy. Clearly, formal democracy is not enough for substantive legitimacy of governments, the influence of citizens must in some sense be real, and this is something that would benefit from further elaboration. Relatedly, while most of our discussion has revolved around autocratic regimes, our arguments are obviously also relevant to cases of governments seeking to undermine democracy, where the basis for regime substantive legitimacy is eroding, as evident in what Lührmann and Lindberg (Citation2019) term the third wave of autocratisation. Moreover, one should consider how requirements of substantive legitimacy of governments relate to other concepts in international relations, including the concept of sovereignty. Here, substantive legitimacy will likely be more consistent with an idea of citizen sovereignty rather than government sovereignty, which would entail a shift in how these types of arguments are presented and debated in international relations.

The normative part of the research agenda should aim at analysing and distinguishing the moral status of different acts of legitimation performed by different actors towards different agents in different contexts, in much greater detail than what has been done here. This includes a more elaborate delineation of negative and positive obligations than we could perform here, also given the obligations of other non-corporate agents, and including the non-ideal setting where their obligations are not observed. The relative obligations of home country governments and corporations need to be analysed here; the primary obligations for recognising and adding authority to foreign governments are likely to reside with the former. However, how should we think about corporate obligations where a home government chooses to disregard substantive legitimacy in its relation to other governments? The failure of a home government to include these dimensions in foreign policy does not necessarily absolve corporations of negative obligations to avoid legitimising autocratic regimes. One could also imagine instances in which the legitimising power of corporations could be stronger than that of their home governments, for instance in terms of lending credibility to claims of high autocratic economic performance, which could make blindly following the policy of the home government problematic. A final aspect that may be even more challenging to analyse, are the positive obligations corporations may have to legitimize pro-democracy forces in autocracies. Here considerable creativity is possible in terms of recognising and interacting with non-regime controlled unions and organisations are possible, and these options merit further consideration. In the classic terms of Hirschman (Citation1970), the only alternative to (all too frequent) loyalty to undemocratic regimes need not be to exit the country, it can also be to exercise voice, or more broadly to empower and legitimize individuals and groups that can hold a government accountable.Footnote8

The empirical part of the agenda would include an analysis of when and how different forms of legitimation are used for strategic advantage by corporations. How is this shaped by business opportunities and threats in societies governed by autocratic regimes, how are these strategies affected by regime type and the self-legitimising strategies of autocratic regimes, and other aspects of the economic, social and cultural context? Is there any potential backlash from consumers, workers, regulators or other stakeholders in democratic countries where a company operates, and how does this measure up against any strategic advantages generated in the markets of autocratically governed countries? We know from previous work that autocracies have higher levels of corruption and elite capture (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2016), which likely makes connections and goodwill from autocratic elites more central to doing business and accessing opportunities in these types of societies, or to protect investors from downside risks. Previous studies have also documented how corporations use corporate social responsibility activities strategically to access market opportunities controlled by elites (Wiig & Kolstad, Citation2010). More work is, however, needed on the exact mechanisms through which regime legitimation affects corporate competitive advantage.

The other main empirical question to pursue is the extent to which symbolic acts of legitimation actually increase the perceived legitimacy of an autocratic regime. This will likely vary with the position and authority of the company and executive performing these acts. Paradoxically, it is also possible that praise of an autocratic regime that is seen as self-serving, may have little effect on the perceived legitimacy of the regime. Nevertheless, an emerging literature on the effects of large sporting events suggest that this is used by autocratic regimes to increase support, possibly to some effect (Baade & Matheson, Citation2016; Næss, Citation2018). Their formal status notwithstanding, it probably makes sense to view international organisations like the International Olympic Committee and FIFA as corporations rather than NGOs. There is, however, a lack of knowledge on how statements and actions by corporations and their executives affect perceptions of regime legitimacy more broadly. This should be a matter of further study for both qualitatively and quantitatively oriented researchers.

On a more general note, corporations and their executives not only confer legitimacy on governments, but also other agents, like business partners, business associations, or even unions. In cases of compensation for corporate wrongdoing, legitimacy is also conferred by recognising certain individuals or organisations as representatives of the populations suffering harm. We would be quick to call middle-men of these types fraudulent if lacking the consent of the people they claim to represent. As for the case of corporate government relations discussed in this article, the corporation as legitimiser rather than legitimisee has been largely overlooked in the corporate social responsibility literature. We should also recognise and analyse the ways in which the legitimacy of corporations and that of governments are linked. It is hard to see how accreditation, recognition or permission received from an autocratic government that lacks substantive legitimacy, actually provides a licence to operate commercial enterprise that affects the interests of the citizens of a country. Even the defence that corporations provide jobs and activity in undemocratic countries seems to fail given recent empirical evidence clearly indicating that the causal impact of democracy on development is positive (Acemoglu et al., Citation2019); more jobs and greater economic activity would likely be available under a different regime.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ivar Kolstad

Ivar Kolstad is a Professor of Business Ethics at the Norwegian School of Economics, and an Associated Senior Researcher at the Chr. Michelsen Institute in Bergen, Norway. His research focuses on corporate social responsibility and the political economy of globalization and development.

Notes

1 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rqi8ZM2UW14, last accessed 9 November 2019. The statement is made approximately 1:55 into the video.

2 Complicity is conventionally defined as knowingly contributing to a wrongdoing or the ability of another party to perform a wrongdoing (Wettstein, Citation2010, Citation2012). A somewhat broader definition is given by Kutz (Citation2000), as intentionally participating in the wrong others do or the harm they cause, independent of the difference you make.

3 An extreme example of this form of legitimation by a corporate leader is Tesla CEO Elon Musk's suggestion that Taiwan should become a special economic zone in China akin to Hong Kong. See ft.com/content/5ef14997-982e-4f03-8548-b5d67202623a, last accessed 8 October 2022.

4 See for instance https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2018-09-03/secretary-generals-remarks-china-africa-cooperation-summit-delivered and https://www.businesstelegraph.co.uk/hsbc-chief-exec-john-flint-comes-under-fire-after-praising-chinas-communist-regime/, both last accessed 23 November 2019.

5 This index is created by subtracting the Polity autocracy score from the Polity democracy score, and we restrict the sample to democracy scores from 0 to -10.

6 We do not normalize FDI by GDP, since income can have an independent effect on democracy, making results hard to interpret. Nor do we log FDI values, since standard transformations of negative values (such as setting them to zero) entail a loss of information contained in these values.

7 More elaborately, the V-Dem country experts code each country-year on the question ‘To what extent does the government refer to performance (such as providing economic growth, poverty reduction, effective and non-corrupt governance, and/or providing security) in order to justify the regime in place?’, with response categories 0: Not at all, 1: To a small extent, 2: To some extent but it is not the most important component, 3: To a large extent but not exclusively, 4: Almost exclusively. As can be seen in in Appendix 1, there is considerable variation in how countries score on this variable. For further details on the theoretical basis and methodology behind the index, please see Tannenberg et al. (Citation2019).

8 More broadly, this is related to the notion in the corporate citizenship literature that corporations can be enablers of and conduits for civil and political rights (Matten & Crane, Citation2005).

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2008). Income and democracy. American Economic Review, 98(3), 808–842. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.3.808

- Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restropo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(11), 47–100. https://doi.org/10.1086/700936

- Asiedu, E., & Lien, D. (2011). Democracy, foreign direct investment, and natural resources. Journal of International Economics, 84(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2010.12.001

- Aslaksen, S. (2010). Oil and democracy: More than a cross-country correlation? Journal of Peace Research, 47(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310368348

- Baade, R. A., & Matheson, V. A. (2016). Going for the gold: The economics of the Olympics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.2.201

- Babic, M., Fichtner, J., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2017). State versus corporations: Rethinking the power of business in international politics. International Spectator, 52(4), 20–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1389151

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Caselli, F., & Tesei, A. (2016). Resource windfalls, political regimes, and political stability. Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(3), 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00538

- Dube, A., Kaplan, E., & Naidu, S. (2011). Coups, corporations, and classified information. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3), 1375–1409. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjr030

- Dukalskis, A. (2015). Endorsing repression – Nonviolent movements and legitimizing regime violence in autocracies. Paper presented at the ECPR General Conference, Montreal, August 26–29, 2015, https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/8375ff3e-eb14-4030-9fd5-61a7d2999001.pdf

- Dukalskis, A., & Gerschewski, J. (2017). What autocracies say (and what citizens hear): proposing four mechanisms of autocratic legitimation. Contemporary Politics, 23(3), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304320

- Edel, M., & Josua, M. (2018). How authoritarian rulers seek to legitimize repression: Framing mass killings in Egypt and Uzbekistan. Democratization, 25(5), 882–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1439021

- Eichengreen, B., & Leblang, D. (2008). Democracy and globalization. Economics and Politics, 20(3), 289–334.

- Escribá-Folch, A. (2017). Foreign direct investment and the risk of regime transition in autocracies. Democratization, 24(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2016.1200560

- Frynas, J. G. (2005). The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. International Affairs, 81(3), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00470.x

- Fuchs, A., & Klann, N. H. (2013). Paying a visit: The Dalai Lama effect on international trade. Journal of International Economics, 91(2013), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2013.04.007

- Gel’man, V. (2023). Exogenous shock and Russian studies. Post-Soviet Affairs, 39(1-2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2022.2148814

- Gerschewski, J. (2013). The three pillars of stability: Legitimation, repression and co-optation in autocratic regimes. Democratization, 20(1), 13–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738860

- Gerschewski, J. (2018). Legitimacy in autocracies: Oxymoron or essential feature? Perspectives on Politics, 16(3), 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717002183

- Gitmez, A. A., & Sonin, K. (2023). The dictator’s dilemma: A theory of propaganda and repression. Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2023-67. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Gjerløw, H., & Knutsen, C. H. (2019). Leaders, private interests, and socially wasteful projects: Skyscrapers in democracies and autocracies. Political Research Quarterly, 72(2), 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919840710

- Guidolin, M., & La Ferrara, E. (2007). Diamonds are forever, wars are not: Is conflict bad for private firms? American Economic Review, 97(5), 1978–1993. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.5.1978

- Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2019). Informational autocrats. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 100–127. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.100

- Heydemann, S., & Leenders, R. (2011). Authoritarian learning and authoritarian resilience: Regime responses to the ‘Arab awakening’. Globalizations, 8(5), 647–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2011.621274

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

- Huntington, S. P. (1991). Democracy’s third wave. Journal of Democracy, 2(2), 12–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1991.0016

- Kim, N. K. (2022). Foreign direct investment and democratic survival: A sectoral approach. Democratization, 29(2), 232–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1950143

- Kolstad, I. (2020). Too big to fault? Effects of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize on Norwegian exports to China and foreign policy. International Political Science Review, 41(2), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118808610

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2016). Does democracy reduce corruption? Democratization, 23(7), 1198–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1071797

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2018). Diversification and democracy. International Political Science Review, 39(4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512116679833

- Kutz, C. (2000). Complicity. Ethics and law for a collective age. Cambridge University Press.

- Li, Q., Owen, E., & Mitchell, A. (2018). Why do democracies attract more or less foreign investment? A metaregression analysis. International Studies Quarterly, 62(3), 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy014

- Li, Q., & Resnick, A. (2003). Reversal of fortunes: Democratic institutions and foreign direct inflows to developing countries. International Organization, 57(1), 175–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303571077

- Li, Q., & Reuveny, R. (2003). Economic globalization and democracy: An empirical analysis. British Journal of Political Science, 33(01), 29–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007123403000024

- Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/1951731

- Lührmann, A., & Lindberg, S. I. (2019). A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization, 26(7), 1095–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

- Mathur, A., & Singh, K. (2013). Foreign direct investment, corruption, and democracy. Applied Economics, 45(8), 991–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.613786

- Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.15281448

- Næss, H. E. (2018). The neutrality myth: Why international sporting associations and politics cannot be separated. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 45(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2018.1479190

- Pogge, T. (2001). Achieving democracy. Ethics & International Affairs, 15(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7093.2001.tb00340.x

- Przeworski, A. (2023). Formal models of authoritarian regimes: A critique. Perspectives on Politics, 21(3), 979–988. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722002067

- Reyes, A. (2011). Strategies of legitimization in political discourse: From words to actions. Discourse & Society, 22(6), 781–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926511419927

- Ripstein, A. (2004). Authority and coercion. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 32(1), 2–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00003.x

- Ross, M. L. (2001). Does oil hinder democracy? World Politics, 53(3), 325–361. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2001.0011

- Rudra, N. (2005). Globalization and the strengthening of democracy in the developing world. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 704–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00150.x

- Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Economic integration, democracy and the welfare state. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017697344217

- Shaxson, N. (2007). Poisoned wells: The dirty politics of African oil. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Tannenberg, M., Bernhard, M., Gerschewski, J., Lürhmann, A., & van Soest, C. (2019). Regime legitimation strategies (RLS) 1900 to 2018. Working paper 2019:86. Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

- Tannenberg, M., Bernhard, M., Gerschewski, J., Lürhmann, A., & van Soest, C. (2021). Claiming the right to rule: Regime legitimation strategies from 1900 to 2019. European Political Science Review, 13(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000363

- Thyen, K., & Gerschewski, J. (2018). Legitimacy and protest under authoritarianism. Explaining Student Mobilization in Egypt and Morocco During the Arab Uprising. Democratization, 25(1), 38–57.

- Tsourapas, G. (2021). Global autocracies: Strategies of transnational repression, legitimation, and co-optation in world politics. International Studies Review, 23(3), 616–644. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viaa061

- Tsui, K. K. (2011). More oil, less democracy: Evidence from worldwide crude oil discoveries. Economic Journal, 121(551), 89–115.

- Weber, M. (1964). The theory of social and economic organization. Free Press.

- Wenar, L. (2008). Property rights and the resource curse. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 36(1), 2–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2008.00122.x

- Wettstein, F. (2010). The duty to protect: Corporate complicity, political responsibility, and human rights advocacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0447-8

- Wettstein, F. (2012). Silence as complicity: Elements of a corporate duty to speak out against the violation of human rights. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20122214

- Wiig, A., & Kolstad, I. (2010). Multinational corporations and host country institutions: A case study of CSR activities in Angola. International Business Review, 19(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.11.006

Appendices

Appendix 1. Variables and descriptive statistics

Table A1. Main variables.

Table A2. Summary statistics.