ABSTRACT

This article investigates the relationship between populism in power and the expansion of mechanisms of direct democracy (MDDs) in Latin America. We hypothesise that the introduction of new or additional MDDs is more likely under populist than non-populist presidents due to core populist ideas. We then add a conditional explanation to this ideational argument grounded in a strategic calculus and hypothesise that the expansion of MDDs is even more likely if the political context in which populist presidents are embedded provides strategic incentives to promote MDDs. We test these hypotheses by means of logistic and Poisson regression analyses using a newly compiled data set covering information on the introduction and reform of MDDs in 18 Latin American countries from 1980 to 2018. Our results indicate that expansion of MDDs is, indeed, more likely promoted by populist presidents and that this association is conditioned by the degree of presidential approval.

The consequences of populism have been on the public and academic agenda for quite some time now, especially due to the rise of populist forces to power in both new and established democracies across the globe. One of the unresolved and most debated questions surrounding the topic is the potential impact populism may have on modern representative democracy. Several theoretical arguments have been made about the ambiguous relationship between populism and democracy (see Canovan, Citation1999; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012). On the one hand, populism seems to have a fierce relationship with institutions of liberal democracy, like checks and balances or press freedom (e.g. Kenny, Citation2020). On the other hand, researchers ascribe populism the potential to strengthen political participation due to its inclination towards vertical mechanisms of democratic accountability, like direct democratic institutions or elections (e.g. Mény & Surel, Citation2002).

While empirical research provides considerable insights into the impact of populism on the liberal model of democracy (e.g. Huber & Schimpf, Citation2016; Juon & Bochsler, Citation2020), empirical research on the effect of populism on democratic participation is scarce (e.g. Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021; Ruth-Lovell & Grahn, Citation2023). Most research on Latin America has focused on a few highly visible populist governments (e.g. Hugo Chávez in Venezuela) or on local-level participatory institutional change (e.g. participatory budgeting, citizen assemblies, communal councils) (see Balderacchi, Citation2017; Rhodes-Purdy, Citation2015). Research on Western Europe, in contrast, mainly focusses on the use of already existing direct democratic instruments through populist elites (e.g. Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2020) or the (attitudinal) support of populist citizens for direct democratic processes (e.g. Jacobs et al., Citation2018; Mohrenberg et al., Citation2021).

To the best of our knowledge, the relationship between populism and the legal introduction of mechanisms of direct democracy has not been systematically analysed in a large-N cross-national research design. The lack of empirical research on the consequences of populism for direct democratic institutional change is surprising, especially in the Latin American context, where democratic institutions are weaker and institutional change processes more frequent than in Europe (see Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012; Negretto, Citation2013). Moreover, in such contexts, populist forces often come to power with an institutional change agenda, directed against traditional institutions of modern representative democracy (e.g. Levitsky & Loxton, Citation2013; Ruth, Citation2018).

Hence, the Latin American region offers us a set of crucial-most likely cases to address this research lacunae (Levy, Citation2008). The aim of this article, therefore, is to investigate the partial effect of populism on the expansion of legal provisions of mechanisms of direct democracy (hereafter: MDDs) in Latin America since the beginning of the Third Wave of democratisation. We focus on MDDs on the national level since they figure prominent among the variety of instruments of direct citizen participation.

To do so, we test several arguments as to why the introduction of MDDs should be more likely under populist rule. Our first line of reasoning traces back to a core set of populist ideas and how they shape the incentives of political actors to increase legal opportunities for citizens to influence democratic decisions directly (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018). However, once introduced these mechanisms are difficult to control and may be used by opposition actors to bring about decisions that go against the preferences of the government. Thus, our second line of reasoning is based on a strategic calculus, arguing that political actors are more likely to introduce MDDs if they anticipate that these institutions change the power balance in their system to their advantage. More specifically, we expect populist actors to be more inclined to introduce new MDDs if they command high levels of popular support (Corrales, Citation2016; Weyland, Citation2001). We, first, collected original data that covers the historical trajectory of constitutional and legal provisions of MDDs in 18 Latin American democracies from 1980 to 2018. We then test our theoretical arguments by means of logistic and Poisson regression analyses. Our results particularly support the (conditional) strategic calculus hypothesis. While populist presidents are, on average, more likely to introduce (more) MDDs in their respective countries than their non-populist counterparts, this association is moderated by the level of presidential approval they command.

Direct democratic institutional change: populism, power, and the people

Mechanisms of direct democracy (MDDs) are defined as a set of procedures allowing citizens to influence political decisions directly through a vote beyond regular elections of representatives (see Altman, Citation2010). Theoretically, these mechanisms offer ways to institutionalise democratic ideas, like popular sovereignty and self-government, and they are often associated (or even equated) with a participative model of democracy (Held, Citation2006). Modern democracies are, however, first and foremost representative democracies, nevertheless, MDDs have often been identified as a potential solution to remedy some of the pitfalls of democratic representation (Altman, Citation2010). However, the relationship between direct and representative democracy may also be conflictive, depending on the type of MDDs that are added to the mix of democratic institutionalisations (Welp, Citation2022).

Hence, designing and changing institutions of direct democracy within the context of representative democracies is a delicate task and usually involves several political actors (Negretto, Citation2013; Scarrow, Citation2001). Mechanisms of direct democracy touch upon the power balance between political actors, and therefore, entail high stakes (Hug & Tsebelis, Citation2002). For example, a referendum in the hands of the executive can erode the power of the legislature (e.g. Durán-Martínez, Citation2012); while mandatory referendums or citizen initiatives can be activated beyond the control of governments and may even be directed against the policies a government pursues (e.g. Leemann & Wasserfallen, Citation2016). Thus, it can be expected that the introduction of MDDs will most likely be resisted by some political actors. We argue here that governments play a crucial role in these processes. This is especially the case in Latin American presidential systems, where the presidency is the most important prize to win, and usually, presidents are veto players in institutional change processes (Corrales, Citation2016; Negretto, Citation2013). Therefore, to analyse the institutional consequences of populism, we focus on populism in power as opposed to populists seeking power (De La Torre, Citation2010). But why should populist presidents strengthen citizens’ direct political participation? In the following section, we elaborate on why the introduction of MDDs should be more likely under populist than under non-populist rule.

To theorise the relationship between populism and direct democracy, we use a minimalist ideational conceptualisation that defines populism as ‘a moral discourse that not only exalts popular sovereignty, but understand the political field as a cosmic struggle between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’’ (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018, p. 3). Conceptually, the ideational definition of populism is based on three core ideas that form the necessary defining characteristic of populism: people-centrism, anti-elitism, and an antagonistic relationship between the ‘virtuous people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’ (e.g. Hawkins, Citation2009; Mudde, Citation2004; Rooduijn, Citation2013).

This definition of populism lends itself well to compare populism across time and space as well as to compare historical cases with contemporary populism (Hawkins, Citation2009; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2018). Most importantly, the ideational foundation allows us to theorise about the link between populism and different democratic ideas, like accountability, popular sovereignty, self-government, or majoritarianism (see Ruth-Lovell & Grahn, Citation2023).

The inclination of populism towards direct democratic procedures can be linked back to the ideational core inherent to the concept itself. More specifically, at its core, populism is about ‘the ‘who’ of politics’ (Stanley, Citation2008, p. 102) and due to its people-centrist and anti-elitist inclination, populist ideas gravitate towards certain democratic institutionalisations. For example, since ‘the corrupt elite’ plays a central role in the system of horizontal checks and balances, populists often advocate against these core liberal democratic institutions, which is why they are perceived as a threat to liberal democracy in particular (e.g. Juon & Bochsler, Citation2020; Kenny, Citation2020; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012). More importantly, due to ‘the good people’s’ central role in mechanisms of direct democracy populists across many different contexts have been strong advocators of these institutions in their political discourse (e.g. Hawkins, Citation2009; Mohrenberg et al., Citation2021). Taken together populism has an ideational inclination towards a radical democratic model based on a plebiscitarian style of participation that runs counter to liberal democratic institutions (Caramani, Citation2017).

Furthermore, MDDs do not just resonate well with the idea of popular sovereignty, a key component of people-centrism, but also with the implicit majoritarianism evoked to identify ‘the will of the people’ (see Stanley, Citation2008). As such, MDDs reverberate with the binary, decisive logic of direct democratic decision-making as well as the simplicity of a majority vote (usually based on yes/no questions) (Ruth-Lovell & Grahn, Citation2023, p. 682). Hence, the format of decision-making by means of MDDs also falls in line with the antagonistic worldview of populists, ‘the us versus them’.

Consequently, based on these core principles of their discourse populist presidents have a substantive-ideational interest to introduce and expand MDDs. This leads us to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Populist presidents are more likely to introduce or expand MDDs, due to their ideational appeal.

However, irrespective of their populist ideas, political actors may want to introduce MDDs based on strategic grounds as well. For instance, presidents will only be capable of both effectively use these instruments and engage in institutional change if they anticipate to have the public on their side (Corrales, Citation2016; Negretto, Citation2013). Although MDDs are a means to bring the voice of the people into public policy-making, in essence, elites have plenty of leverage to strategically use these instruments, once they are institutionalised (e.g. Morel & Quortrup, Citation2017). Favourable public support levels of presidents open a window of opportunity that may encourage them to engage in contentious politics and expand the provisions of MDDs in their respective country, as observed in presidential impeachment processes or the abolition of constitutional checks on presidential re-election (Corrales, Citation2016; Hochstetler, Citation2006). Moreover, several arguments can be made that populist presidents are especially dependent on the support of the public to increase their power vis-à-vis other political actors in the system. For one, populism frequently correlates with organisational features emphasising charismatic, delegative leadership and the reliance on unmediated support of the masses (e.g. Barr, Citation2009; Weyland, Citation2001). As such, populist presidents particularly gravitate towards MDDs, if they expect them to be a useful strategic weapon to authenticate and legitimise their governments’ interpretation of the ‘will of the people’ (Stanley, Citation2008; Welp, Citation2022).

Second, populist presidents need to live up to their voters high expectations in doing politics differently than their predecessors, since they often portray themselves as ‘caretakers’ who ‘get things done’ and deliver on their electoral promises (Müller, Citation2016; Rooduijn, Citation2013). More specifically, there are two political programs closely related to populist mandates: complex economic policy change and institutional change (Levitsky & Loxton, Citation2013; Weyland, Citation2001). In both instances, populist presidents face strong incentives to additionally legitimise these complex political changes through MDDs. The introduction of MDDs is, therefore, perfectly suited to address such promises once they are in office. Thus, we hypothesise an interactive relationship between populist ideas and popular support, arguing that the likelihood of populist presidents to introduce MDDs is conditioned by their ability to sustain high levels of popular support. This leads us to the following conditional hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (conditional): The propensity of populist presidents to introduce or expand MDDs is magnified by their popularity, due to a strategic calculus.

Since these hypotheses are assumed to hold, ceteris paribus, we have to control for other factors that might influence our hypothesised relationship. First, we control for the institutional status quo of direct democratic mechanisms. The introduction of new MDDs is related to already existing provisions of MDDs. The need to introduce MDDs should be less pressing if some provisions for citizens’ direct involvement in decision-making exist already. However, in line with Scarrow (Citation2001) we argue that the presence of some MDDs does not fully deter actors from introducing additional and more far reaching provisions, since ‘there is no single recipe for optimally balancing direct and delegated decision making, institutional solutions are often re-engineered to address perceived shortcomings with existing practices’ (Scarrow, Citation2001, p. 652).

Second, presidential regimes may vary considerably with respect to the distribution of presidential power. Institutional provisions of checks and balances as well as electoral and party systems characteristic may considerably constrain presidents in realising their political agenda (Shugart & Carey, Citation1992). To successfully implement their political agenda presidents rely either on partisan support in the legislature or on other constitutional means – like executive decree authority or the provision of a presidential veto – to push their political projects through Congress (Samuels & Shugart, Citation2003). The presence of different presidential power resources may, hence, decrease the incentives of presidents to engage in the time-consuming processes of institutional change. Thus, we expect powerful presidents to be less likely to introduce or expand MDDs.

Third, irrespective of the role political actors’ play in advocating institutional change towards more MDDs, we also need to factor in the intensity of public demand for more direct citizen participation in politics (Welp, Citation2022). One of the major political debates in Latin America in the last decade circulated around an on-going ‘crisis of representation’. Protestors took to the streets to express a lack of confidence in representative institutions and demanded more direct citizen intervention, for instance, in Argentina (2001), more recently in Chile (2019) and Colombia (2019, 2021). The perceived level of crisis of representative institutions within the citizenry may pave the way for alternative forms of direct citizen participation in the political arena. Therefore, we expect the level of protest against the representative system of government to increase the likelihood of the introduction of MDDs.

Forth, several studies indicate that ideology may play a role in the introduction of MDDs as well as with respect to the types of populist governments the Latin American region experienced in the last decades (e.g. Levitsky & Roberts, Citation2011). To disentangle the effect of the ‘thin’ ideational core of populism from the ‘thick’ left-right ideology we need to control for this factor as well (see Mudde, Citation2004). Independently of populism, we expect a positive effect of left-ideology on the introduction of new MDDs.

Finally, we also control for two country level factors that indicate the democratic and economic development of the system. The degree of democratic experience and the level of economic development in a country may influence the demand for democratic innovations such as direct democratic mechanisms (e.g. Inglehart, Citation2015).

Research design

Case selection

We consider Latin American Third Wave democracies to offer a set of crucial-most likely cases to put our arguments to the test (Levy, Citation2008). We do so for the following reasons: first, all countries in this region are presidential regimes which may be beneficial for the rise of populism due to the higher degree of personalisation and the direct legitimacy of presidents (Linz, Citation1990). Second, populism has a long history in Latin America (Di Tella, Citation1965; Germani, Citation1978) and several countries in this region experienced populism in power over the last three decades (Ruth, Citation2018). Finally, the region experienced an unprecedented increase in both the legal provision as well as the use of direct democratic mechanism since the beginning of the Third Wave (Welp & Ruth, Citation2017). For example, only five countries in Latin America provided their citizens with a direct say in national policy-making at the beginning of the 1980s (Ecuador, El Salvador, Panama, Uruguay, and Venezuela) (see ).Footnote1 This pictures changes drastically and by the end of our period of investigation all 18 countries in the region include some MDDs. Moreover, the procedures through which MDDs were introduced (or changed) vary from regular laws, to presidential decrees, and constitutional reforms.

Table 1. Introductions and Expansions of MDD Norms (1900-2018).

To study in how far populism can be considered a driver in explaining this drastic expansion of MDDs in Latin America, we analyse all presidential terms (both elected and non-elected) since the Third Wave of democratisation (1980-2018). Our units of analysis are, hence, presidential terms. Note, that we consider (both immediate and non-immediate) re-elections as independent cases. However, we include only those presidents who served a minimum of six months in office, since time is of the essence in institutional change processes. Based on these criteria we compiled a data set covering 18 Latin American democracies from 1980 until 2018Footnote2 including a total of 133 presidential terms.Footnote3

In the next section, we will describe in detail how we operationalise our dependent variables, our main explanatory variables, as well as our control variables.Footnote4

Operationalisation

Introduction of MDDs. For our dependent variable we consider MDDs as ‘introduced’ if a legal norm clearly specifies the two criteria necessary to use an instrument as theorised by Hug and Tsebelis (Citation2002) as well as Breuer (Citation2007): the clear specification of, first, the procedure and political actors involved in the activation of a mechanism (initiator), and second, the procedure and political actors involved in setting the agenda of the direct vote (agenda-setter). Sometimes MDDs have only been mentioned by name in the constitution but effectively became available only after a regulating law or decree has been enacted (for example, Colombia introduced MDDs in its 1991 Constitution, which became available only after the enactment of a regulating law in 1994). Hence, considerable time may pass between the symbolic (nominal) introduction of MDDs in a constitution and the effective introduction through the regulation of these mechanisms by laws or decrees (in our sample this time period ranges from a minimum of four months in the case of Peru (1993-1994) to a maximum of ten years in Brazil (1988-1998). Nevertheless, most constitutions that incorporate MDDs clearly specify the regulatory requirements to effectively use these instruments, and hence, do not require the subsequent regulation through other legal norms. Moreover, as mentioned in the theoretical section, we only consider MDDs that lead to a binding vote by the citizens, which exclude both consultative measures as well as instruments that allow citizens to set the legislative agenda.

Systematic data on change in constitutional provisions of these instruments and on the design of direct democratic mechanisms is provided by the C2D database (http://www.c2d.ch). We complement this information through an in-depth analysis of legal norms regulating direct democratic mechanisms most of which were either provided by the Political Database of the Americas (http://pdba.georgetown.edu) or through national legislative databases (detailed information on these sources is provided in Table S2 in the supplement). The latter was necessary since, although many countries regulate MDDs in their constitution, we found several examples where MDDs have been introduced or reformed through the regular legislative process (e.g. Bolivia in 2004) or by presidential decree (e.g. Honduras in 2010).

Based on this novel dataset we, first, create a dummy variable (MDD Intro) that takes on the value 1 if there has been an amendment to a countries constitution or the introduction of a new law or decree which regulates at least one new MDD on the national level. The coding is irrespective of the previous status quo of MDDs, since there are cases in our sample where some instruments have been provided in the constitution but the present government nevertheless expanded these instruments through the introduction of new MDDs (e.g. Rafael Correa 2008 in Ecuador and Evo Morales 2009 in Bolivia).Footnote5 The variable indicates that in about 12 per cent of the cases in our sample new MDDs have been introduced.

Second, we also account for the number of MDDs in a country (MDD N) at the end of a presidential term. We count MDDs as separate instruments due to the following criteria: first, if they differ according to the political actors that can initiate a procedure (initiator) and that can formulate the question (agenda-setter). Second, we count MDDs as separate instruments if the same procedure has different normative functions (enacted laws or pending bills, see Uleri 1996) or aims at different scopes (policy vs. constitutional change, see Durán-Martínez, Citation2012). This count variable enables us to tap into the extensiveness of provisions for direct citizen participation in a given administration.Footnote6 The variable ranges from 0 to 9 with a mean of 2.73 and a standard deviation of 2.45.

Furthermore, we code the main independent variables and the control variables stated in the theoretical part as follows:

Populist President. To distinguish populist from non-populist presidents, we use Ruth’s (Citation2018) data set on presidential terms and populist mandates. The data set provides binary codes for all presidential terms during our period of study (1980-2018). To be considered a populist (1), presidents necessarily need to be elected and must have used a populist discourse in their electoral presidential campaign. Ruth (Citation2018) identifies presidents with a populist mandate following a two-step procedure combining both qualitative literature review and expert validation. This results in a list of 16 presidents with populist mandates accounting for 24 presidential terms (or 21 per cent) in our sample of 117 presidential terms.Footnote7

Presidential Approval. To capture a president’s popular support we use presidential approval ratings from public opinion surveys provided by Carlin et al. (Citation2019). Data on quarterly net approval ratings for most of our presidential terms is available online via the webpage of the project: www.executiveapproval.org. In total, data on presidential approval ratings was available for 117 out of 133 presidential terms in our sample. To account for the time structure in our argument and period effects in presidential approval ratings (i.e. the honeymoon phase as well as electoral dynamics) we calculate the mean presidential approval rating for the first two years in each presidential term. The variable has a mean of 0.48 and a standard deviation of 0.13 in our sample.

Status Quo MDD. In Models 1 and 2 below, we include a dummy variable for the presence of any MDD before the inauguration of a president (SQ MDD). The variable indicates that in about 52 per cent of our cases MDDs have been legally available before the inauguration of a new administration (see ). In Models 3 and 4 below, we include a count variable indicating the number of MDDs available before the inauguration of a president (SQ MDD N). Presidents in our sample have, on average, 2.21 MDDs at their disposal when they enter office.

Table 2. Logistic Regression Analyses (MDD Intro).

Constitutional Power. We account for the constitutional powers a president has to influence the legislative decision-making process (Shugart & Carey, Citation1992). We follow the reasoning of Samuels and Shugart (Citation2003, p. 43) to code constitutional provisions of three presidential powers over legislation at the beginning of a presidential term: veto power, agenda setting power, and decree power. Constitutions (including amendments and reforms) are provided by the Political Database of the Americas (http://pdba.georgetown.edu). The constitutional power index that results from our coding ranges from 0 (no powers at all) to 7 (all three powers). The variable has a mean of 2.71 with a standard deviation of 1.98 in our sample.

Partisan Power. Here we need to measure the partisan power a president has to influence the legislative decision-making process through his or her party (Samuels & Shugart, Citation2003). We use seat share data for the lower chamber of the legislature to code this control variable. Data on legislative seats was taken from national election statistics. The variable has a mean of 0.36 with a standard deviation of 0.19 in our sample.

Left-Ideology. To control the ideological leaning of each president, we use the Dataset on Political Ideology of Presidents and Parties in Latin America (Murillo et al., Citation2010). The dummy variable we code based on this data includes both left and centre-left presidents, which account for 70 presidential terms (or 60 per cent of the cases) in our sample.

Anti-System Protest. We proxy the often cited citizen alienation from representative politics by using data from the Global Data on Events, Location and Tone (GDELT) Project on the frequency of anti-system protest (https://www.gdeltproject.org). Therefore, we calculate the average monthly number of anti-system protest events in the first two years of a presidential term. We count all root events coded by the GDELT Project by citizens directed against the respective country’s political institutions (executive, legislative, judicative branches of government, as well as the security apparatus). The variable has a mean of 2.1 protests per month and a standard deviation of 4.6 in our sample.

Economic Development. To capture this variable we include the per capita gross domestic product in our model (GDP per capita) provided by the World Development Indicator data set (The World Bank Group, Citationn.d.). The variable has a mean of 3788 current US$ and a standard deviation of 3082 current US$ in our sample.

Democratic Quality. We capture the level of democracy by taking the polity2 score at the beginning of a presidential term provided by the Polity IV project (Marshall et al., Citation2019). The indicator ranges from -10 (full-fledged autocracy) to +10 (full-fledged democracy) it has a mean of 7.85 and a standard deviation of 1.64 in our sample.

Empirical analysis

To test our hypotheses, we employ two sets of analyses with the two dependent variables specified in the previous section: MDD Intro and MDD N. First, we present results from multivariate logistic regression models for our binary dependent variable MDD Intro (Hosmer et al., Citation2013). Second, we present results from multivariate Poisson regression models for our count dependent variable MDD N (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2013). As recommended, we use robust country clustered standard errors to control for violations of underlying assumptions and the nestedness of presidential terms in countries (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2013). We also include the inauguration year for each president to control for an increasing time trend with respect to the introduction of MDDs. Moreover, we also include a lagged dependent variable in our models to account for potential omitted variable bias in our estimations due to the time structure of our data (McGrath, Citation2015).Footnote8

reports the results of two logistic regression models (an unconditional and a conditional specification of the expected relationship between populism and direct democratic institutional change): both models capture the likelihood of the introduction of MDDs (MDD_Intro) throughout a presidential term. The models lend support to our two hypotheses formulated in the theoretical section. More specifically, Model 1 indicates a moderately significant and positive association between populism and the likelihood of the introduction of (new) MDDs (H1). With an odds ratio of 4.221 (se = 3.005)Footnote9, the odds of an expansion of MDDs in a country are four times higher under a populist than a non-populist ruler. This coefficient is significant at a 95 per cent confidence level. Model 1 also indicates that popular support plays a crucial role in direct democratic institutional change processes, with an odds ratio of 1.043 (se = 0.019) per 1 percentage point increase in presidential approval. Substantively, this means that a difference of 10 percentage points in presidential approval ratings increases the odds of this president to expand MDDs by a factor of 1.524.

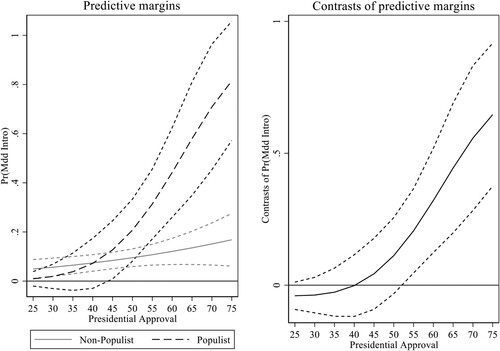

In line with our conditional hypothesis (H2), Model 2 indicates that the likelihood of populist presidents to introduce or expand MDDs in their country is conditioned by their approval ratings. Both goodness of fit measures confirm that the conditional model has a higher explanatory power than the unconditional model and a Wald test (χ2 = 4.2, p = 0.041) confirms that the interaction term is significant and adds value to our model. Since interaction terms in logistic regression models cannot be directly interpreted we inspect this further by plotting the predictive margins of populism conditional on presidential approval in (Brambor et al. Citation2006). The figure shows, first, that the likelihood of populist presidents to introduce or expand MDDs is more strongly conditioned by their support in the public than for their non-populist counterparts, i.e. it increases considerably with higher approval ratings. Second, the association between populist rule and the likelihood of the expansion of MDDs only turns significant at an approval rating of 44 per cent or higher. This hints to the conclusion that, although populist presidents are more inclined to introduce MDDs than their non-populist counterparts, they do not discount strategic factors when considering the legal expansion of MDDs.

To give a few examples: among those populist presidents in our sample who introduced or expanded MDDs, Alberto Fujimori in Peru had the lowest average presidential approval ratings with 47 per cent, while Rafael Correa in Ecuador disposed of the highest average approval ratings in our sample with 75 per cent. In contrast, the range of approval ratings for non-populist presidents who introduced MDDs in our sample is larger – with Carlos Mesa in Bolivia disposing of an average approval rate of 32 per cent and Felipe Calderón in Mexico disposing of an average presidential approval rate of 64 per cent.

With respect to the control variables, two stand out as significant across both Models 1 and 2. For one, the presence of MDDs before the inauguration of a president significantly reduces the likelihood of direct democratic institutional change, in general. More specifically, the likelihood of an expansion of MDDs is less likely than the first time introduction of MDDs by a factor of 0.083 (odds ratio in Model 2, se = 0.064). The second control variable that stands out here is a president’s partisan power. As can be seen in , the association between partisan power and the introduction of MDDs is negative. With an increase of one percentage point in the seat share of the presidential party in the legislature, the likelihood of direct democratic institutional change decreases by a factor of 0.972 (odds ratio in Model 2, se = 0.014).

To evaluate the extensiveness of MDD provisions, we need to take into account how many instruments presidents actually introduce in these processes. Therefore, we created a second dependent variable, which counts the number of MDDs at the end of each presidential term. The variable ranges from 0 (no MDDs) to 9 in our sample. To analyse count data Poisson regression is recommended (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2013). We use the same independent variables in our Poisson models in to explain the variation in our dependent variable as in the logic regression analyses, with the exception of the status quo and the lagged dependent variable, which in the following analysis is represented by the variable SQ MDD N, capturing the number of MDDs available at the end of the previous administration.

Table 3. Poisson Regression Analyses (MDD N).

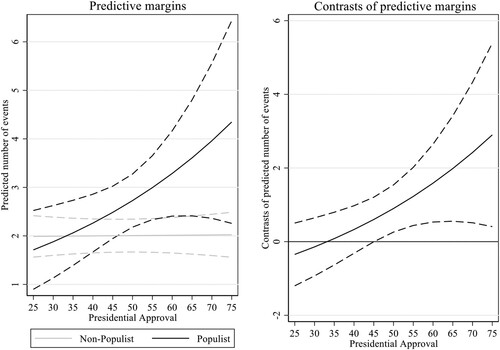

reports the results of an unconditional and a conditional specification of the expected relationship between populism and the change in the number of MDDs throughout a presidential term. The results mirror the findings reported in the first part of the analysis to a considerable extent with respect to our main independent variables (H1 and H2). Although we do not find a significant effect of presidential approval in the unconditional model, the inclusion of the interaction term between populism and presidential approval in Model 4 again indicates that with higher levels of presidential approval, populists are more likely to increase the number of MDDs while in office.Footnote10 To interpret this relationship further we plot the predictive margins of populism conditional on presidential approval ratings in .

As can be seen in the left panel of the graph, this time the conditional relationship only applies to populist presidents (black line), for example, predictive margins indicate that a populist president with an approval rate of 25 per cent will introduce, on average, 1.71 MDDs (se = 0.41) which is considerably lower compared to the 4.35 MDDs (se = 1.07) for a populist president with an approval rate of 75 per cent. Non-populist presidents (grey line), in contrast, introduce on average 2.01 MDDs (se = 0.17) – a number that does not differ considerably across presidential approval ratings. The right panel in shows the contrast between the predictive margins of populist vs non-populist presidents. It indicates that populist presidents are likely to introduce more MDDs than non-populist presidents. However, in line with H2, this difference only reaches significance at presidential approval rates around 50 per cent or higher. For example, at an approval rate of 50 per cent a populist president is predicted to introduce 0.90 MDDs (se = 0.33) more than a non-populist president.

This contrast rises to 2.90 MDDs (se = 1.27) at a very high approval rate of 75 per cent. Hence, in addition to our findings in the first part of the analysis, we can confirm that populists are not only more likely to introduce new MDDs, in general, but also more likely to considerably increase the number of MDDs introduced along the way, i.e. the extent of MDD provisions. That said, in both analyses we find that this populist mandate is conditioned by a strategic calculus, based on a president’s approval ratings.

Finally, with respect to the control variables, the positive and significant coefficient of our lagged dependent variable (SQ MDD N) indicates that in those cases in which some MDDs existed at the beginning of a presidential term actors were also more likely to increase these provisions considerably if they engaged in institutional change. While counter-intuitive at first, this finding highlights that the change in MDDs over time is not only a story of ‘first introductions’ but also of expansions of MDDs. Substantively this may indicate that some type of democratic learning takes place with respect to these instruments, not just on the side of the citizenry, but also among political actors. Which is also mirrored in the slightly significant and positive association between democratic quality and the expansiveness of MDD introductions. Hence, MDDs may be of interest to political actors for many different reasons, even if some instruments are already at their disposal. For example, among the populist presidents that expanded MDDs during their time in office despite the presence of some MDDs at the beginning of their terms are Evo Morales in Bolivia (4 new MDDs), Rafael Correa in Ecuador (1 new MDD) and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (7 new MDDs). Non-populist cases that expanded MDDs during their term in office are Jamil Mahuad in Ecuador (1 new MDD), Porfirio Lobo Sosa in Honduras (1 new MDD), as well as Violeta Chamorro in Nicaragua (5 new MDDs). Finally, the significant and positive association of the lagged dependent variable also indicates that legal provisions of direct citizen participation are sticky and very unlikely to be abolished. In our sample, there has been not one case of abolishment of MDDs.

Conclusion

In this article we delve into the relationship between populism and direct democratic institutional change in Latin America. Our main goal was to systematically analyse the often assumed but never tested positive association between populism and direct democracy. Bridging the literature on the consequences of populism and institutional change we theorise two causal mechanisms that may induce political actors to promote direct democratic institutional change. First, we argue that due to the ideational core of their discourse, populist actors in power are more likely to engage in the expansion of MDDs throughout their time in office. Second, we argue that political actors only engage in institutional engineering that favours the expansion of direct citizen participation if they command high popular support (we call this the strategic calculus). To test our arguments we compiled a presidential term data set covering 18 Latin American countries from 1980–2018 as well as the development of legal provisions of MDDs (including reforms) in these countries.

While our empirical results confirm the widespread assumption that populist presidents are more likely to pursue the expansion of MDDs and increase the potential of direct citizen participation in democratic decision-making in Latin America than their non-populist counterparts, we also find this positive association between populism and direct democratic institutional change to be conditioned by a strategic calculus of those actors. More specifically, populist presidents are more likely to introduce MDDs only if they can count on high levels of public support – anticipating their ability to instrumentalise these mechanisms in their favour later on.

However, two restrictions have to be made with respect to this conclusion. First, many of the institutional change processes that took place under the leadership of populist presidents also bore a lot of symbolic weight through their incorporation into a populist agenda of democratic change (e.g. Balderacchi, Citation2017; Rhodes-Purdy, Citation2015). Second, although citizens may help populist presidents to circumvent the legislative decision-making process through MDDs, these instruments also introduce a new veto player in the political arena, i.e. the people (Hug & Tsebelis, Citation2002). Once in place, these instruments are at the disposal of different political actors and it is entirely unclear if the same actors who promoted their introduction will be able to dominate and control their actual use. For example, the attempted constitutional reforms by Hugo Chávez in 2007 and Evo Morales in 2016 both failed due to their rejection by means of a mandatory referendum.

Based on these findings we see several avenues for future research disentangling the relationship between populism and direct democracy: First, although Latin America is an analytically interesting region to investigate this relationship, the generalisability of results from intra-regional analyses has its limitations. While the institutional and cultural similarities of Latin American democracies allow us to control for certain aspects, they make the travelling of results more difficult. For example, it remains an open question in how far our arguments about populist presidents can be transferred to populist parties or coalition governments in parliamentary systems including populist parties. Hence, future research should heed the plea by Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Citation2018) urging researchers in the field of populism studies to engage in more cross-regional interactions to foster the accumulation of knowledge on the topic.

Second, direct democracy is not one thing but many. Arguments can be made that populists gravitate towards different types of MDDs, for example, those triggered by the authorities (top down), automatically (mandatory), or by the citizens themselves (bottom up) (e.g. Setälä, Citation1999). This could add more fine-grained insights into the ideational or strategic motivation of populist actors supporting direct democratic institutional change.

Finally, another logical next step to investigate the relationship between populism and direct democracy is to study in how far the institutional changes analysed in this article effectively increase citizen participation in the long run. As of now, many of the instruments introduced since the Third Wave of democratisation have only been used occasionally. The introduction of MDDs by populist presidents in Latin America is just part of a larger story which needs further exploration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Saskia P. Ruth-Lovell

Saskia P. Ruth-Lovell is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. In her research she focuses on the impact of clientelism and populism on different facets of representative democracy in Latin America and beyond. She has published articles among others in The Journal of Politics, European Journal of Political Research, Political Studies, and Latin American Politics and Society.

Yanina Welp

Yanina Welp is a Research Fellow a the Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy, at the Geneva Graduate Institute, Switzerland. She holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences from the Pompeu Fabra University Spain and has been awarded her Habilitation in 2015 at the University of St. Gallen. She is co-founder of the Red de Politólogas. In her research she focuses on regime change, political institutions, comparative politics, participatory democracy, democratic innovations, mechanisms of direct democracy.

Notes

1 Nevertheless, despite the lack of regulation, at least 19 referendums were activated ad hoc in several Latin American countries between 1900 and 1990 (Welp & Ruth, Citation2017).

2 Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

3 Note that the estimations are based on 117 cases due to missing data in the presidential approval data (see below and Table S4 in the supplement).

4 Descriptive statistics can be found in Table S1 in the supplement.

5 This also informs our decision to code presidential terms following the introduction (or expansion) of new MDDs as 0 and not as missing (see McGrath, Citation2015). To correct for the potential bias introduced by this data coding decision, we include a one-period lag of our dependent variable (LDV MDD Introt-1) in Model 1 and 2 below (McGrath, Citation2015, p. 539).

6 We contend that the emphasis on the ‘extensiveness’ of MDD provision is a considerable simplification of the impact of MDDs on participatory democracy, and as a consequence our coding assigns each MDD equal weight. To effectively judge the ‘participativeness’ of different MDDs, however, goes beyond the theoretical and empirical scope of this article.

7 For an overview of populist presidents and their terms covered in our sample see Table S3 in the supplement.

8 We code a one-period lag of MDD Intro, to account for an expansion of MDDs in the directly preceding presidential term (LDV MDD Introt-1), to be included in Models 1 and 2. Moreover, the variable SQ MDD N serves as a one-period lagged dependent variable in our Models 3 and 4 below.

9 To ease the interpretation of the coefficients reported in Table 2, we will refer to odds ratios throughout this section, i.e. the exponentiated coefficients.

10 A Wald test (χ2 = 5.4, p = 0.020) confirms the interaction term is significant and adds value to our model.

References

- Altman, D. (2010). Direct democracy worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

- Balderacchi, C. (2017). Participatory mechanisms in Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela: Deepening or undermining democracy? Government and Opposition, 52(1), 131–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2015.26

- Barr, R. R. (2009). Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics. Party Politics, 15(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068808097890

- Brambor T., Clark, W. R., Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Breuer, A. (2007). Institutions of direct democracy and accountability in Latin America’s presidential democracies. Democratization, 14(4), 554–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340701398287

- Cameron, C. A., & Trivedi, P. (2013). Regression analysis of count data. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press.

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. Reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Carlin, R. E., Hartlyn, J., Hellwig, T., Love, G. J., Martinez-Gallardo, C., & Singer, M. M. (2019). Executive Approval Database 2.0. https://www.executiveapproval.org

- Corrales, J. (2016). Can anyone stop the president? Power asymmetries and term limits in Latin America, 1984-2016. Latin American Politics and Society, 58(2), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2016.00308.x

- De La Torre, C. (2010). Populist seduction in Latin America. 2nd ed. Ohio University Press.

- Di Tella, T. (1965). Populism and reform in Latin America. In C. Véliz (Ed.), Obstacles to change in Latin America (pp. 47–73). Oxford University Press.

- Durán-Martínez, A. (2012). Presidents, parties, and referenda in Latin America. Comparative Political Studies, 45(9), 1159–1187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011434010

- Germani, G. (1978). Authoritarianism, fascism, and national populism. Tansaction.

- Gherghina, S., & Pilet, J. B. (2021). Do populist parties support referendums? A comparative analysis of election manifestos in Europe. Electoral Studies, 74, 102419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102419

- Gherghina, S., & Silagadze, N. (2020). Populists and referendums in Europe: Dispelling the myth. Political Quarterly, 91(4), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12934

- Hawkins, K. A. (2009). Is chávez populist?: Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 42(8), 1040–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009331721

- Hawkins, K. A., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). Introduction: The ideational approach. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Held, D. (2006). Models of democracy. 3rd Ed. Stanford University Press.

- Hochstetler, K. (2006). Rethinking presidentialism: Challenges and presidential falls in South America. Comparative Politics, 38(4), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.2307/20434009

- Hosmer, D. W., Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. X. (2013). Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. John Wiley.

- Huber, R. A., & Schimpf, C. H. (2016). Friend or Foe? Testing the influence of populism on democratic quality in Latin America. Political Studies, 64(4), 872–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12219

- Hug, S., & Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto players and referendums around the world. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 14(4), 465–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/095169280201400404

- Inglehart, R. (2015 [1977]). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles Among western publics. Princeton University Press.

- Jacobs, K., Akkerman, A., & Zaslove, A. (2018). The voice of populist people? Referendum preferences, practices and populist attitudes. Acta Politica, 53(4), 517–541. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0105-1

- Juon, A., & Bochsler, D. (2020). Hurricane or fresh breeze? Disentangling the populist effect on the quality of democracy. European Political Science Review, 12(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000259

- Kenny, P. D. (2020). The enemy of the people’: Populists and press freedom. Political Research Quarterly, 73(2), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918824038

- Leemann, L., & Wasserfallen, F. (2016). The democratic effect of direct democracy. American Political Science Review, 110(4), 750–762. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000307

- Levitsky, S., & Loxton, J. (2013). Populism and competitive authoritarianism in the Andes. Democratization, 20(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738864

- Levitsky, S., & Roberts, K. M. (2011). The resurgence of the Latin American left. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Levy, J. S. (2008). Case studies: Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388940701860318

- Linz, J. J. (1990). The perils of presidentialism. Journal of Democracy, 1(1), 51–69.

- Marshall, M. G., Jaggers, K., & Gurr, T. R. (2019). Manual POLITY IV PROJECT: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018 Dataset Users’ Manual. In Polity IV Project.

- McGrath, L. F. (2015). Estimating onsets of binary events in panel data. Political Analysis, 23(4), 534–549. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpv019

- Mény, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002). The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Y. Mény, & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 1–21). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Mohrenberg, S., Huber, R. A., & Freyburg, T. (2021). Love at first sight? Populist attitudes and support for direct democracy. Party Politics, 27(3), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819868908

- Morel, L., & Quortrup, M. (2017). Introduction. In L. Morel, & M. Quortrup (Eds.), The routledge handbook to referendums and direct democracy (pp. 1–7). Routledge.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2012). Populism in Europe and the americas: Threat or corrective for democracy? Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018789490

- Müller, J.-W. (2016). What Is populism? University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Murillo, M. V., Oliveros, V., & Vaishnav, M. (2010). Dataset on Political Ideology of Presidents and Parties in Latin America. Columbia University. http://mariavictoriamurillo.com/data/

- Negretto, G. L. (2013). Making constitutions: Presidents, parties, and institutional choice in Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

- Rhodes-Purdy, M. (2015). Participatory populism: Theory and evidence from bolivarian Venezuela. Political Research Quarterly, 68(3), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915592183

- Rooduijn, M. (2013). The nucleus of populism: In search of the lowest common denominator. Government and Opposition, 49(4), 573–599. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2013.30

- Ruth, S. P. (2018). Populism and the erosion of horizontal accountability in Latin America. Political Studies, 66(2), 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717723511

- Ruth-Lovell, S. P., & Grahn, S. (2023). Threat or corrective to democracy? The relationship between populism and different models of democracy. European Journal of Political Research, 62(3), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12564

- Samuels, D. J., & Shugart, M. S. (2003). Presidentialism, elections and representation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 15(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692803151002

- Scarrow, S. E. (2001). Direct democracy and institutional change: A comparative investigation. Comparative Political Studies, 34(6), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034006003

- Setälä, M. (1999). Referendums in Western Europe - A wave of direct democracy? Scandinavian Political Studies, 22(4), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.00022

- Shugart, M. S., & Carey, J. M. (1992). Presidents and assemblies. Constitutional design and electoral dynamics. Cambridge University Press.

- Stanley, B. (2008). The thin ideology of populism. Journal of Political Ideologies, 13(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569310701822289

- The World Bank Group. (n.d.). World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

- Welp, Y. (2022). The will of the people: Populism and citizen participation in Latin America. De Gruyter.

- Welp, Y., & Ruth, S. P. (2017). The motivations behind the Use of direct democracy. In S. P. Ruth, Y. Welp, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Let the people rule? Direct democracy In the twenty-first century (pp. 99–119). ECPR Press.

- Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: Populism in the study of Latin American politics. Comparative Politics, 34(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/422412