ABSTRACT

Democratic innovations scholars note that deliberation has the potential to counteract populism. However, so far, we do not know what the theoretical foundation would be to expect such an effect, nor do we know to what extent the supposed effect actually materialises empirically. This study adds to the literature by offering a theoretical framework and by testing this framework empirically. Specifically, we examine to what extent citizens with a high degree of populist attitudes became less populist after participating in a deliberative event. We study an actual citizens' assembly on climate mitigation policy in the Netherlands via pre- and post-surveys and carry out an SEM analysis (N = 105). We find that citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes do become less populist, but find no evidence that this is due to the (perceived quality of the) deliberation. At the same time, the climate skeptics who participated became more populist.

There is certainly a large dose of redemptive faith intermingled with the rationalism of most theories of ‘deliberative’ or ‘discursive’ democracy: faith in the transforming power of deliberation, and faith that if the people at the grassroots were to be exposed to it, their opinions would be transformed in the correct (antipopulist) direction. (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 15)

Introduction

Populism is one of the important challenges to contemporary representative democracies. Populist parties, for instance, have been found to erode the quality of democracy (Huber & Schimpf, Citation2017; Ruth-Lovell & Grahn, Citation2023). Populism among citizens can also matter. Not only are populist attitudes among citizens an important factor driving voting for populist parties, they may also be challenging to (representative) democracy in a more direct way.Footnote1 A meta-analysis by Marcos-Marne et al. (Citation2023, p. 6) noted that ‘more populist individuals are less likely to support coalition partners and concede victory to the most voted party’ and are ‘less supportive of democratic norms’.Footnote2 This has spurred many pundits and scholars to look for ‘remedies’ to chip away at the fertile soil of populism among citizens upon which populist parties root themselves. Scholars of deliberative democracy in particular have been optimistic that ‘[d]eliberation promotes considered judgment and counteracts populism’ (Dryzek et al., Citation2019, p. 1145).

Yet, the theoretical and empirical foundation upon which this claim rests is fairly small. Theoretically, the two fields, the populism field and the democratic innovations one, remain largely disconnected. As a result, our theoretical insight into how and why deliberation would ‘counteract’ populism is limited because it starts from the promise of deliberation, not how populist citizens would perceive deliberation. If anything, the populism literature is skeptical of the potential of deliberation. Populists, it is claimed, ‘want more leadership and less participation (…), they want politicians who know (rather than ‘listen to’) the people, and who make their wishes come true’ (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 558). Empirically, there are also important gaps in our knowledge. Some recent studies have studied to what extent citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes support deliberative democracy. These analyses do find that populist citizens support deliberation (Heinisch & Wegscheider, Citation2020; Zaslove et al., Citation2021). However, even these studies suggest that this may indicate a lack of support for representative democracy in practice rather than actual support for deliberative democracy. Moreover, what is lacking is studies that examine what happens when citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes are exposed to real-life deliberation. As we will highlight below, there are reasons to expect that while populists may support the abstract idea of deliberation, they may become disappointed once they actually participate in deliberation, be it because the actual deliberations in smaller groups, or their experiences with politicians and civil servants organising the deliberative event. In short, we do not why and how populist citizens would be affected by deliberation in theory nor do we know whether populism is actually affected by deliberation in empirical practice.

This study aims to fill these two gaps. Theoretically, it links both fields and incorporates insights from both in one framework and empirically tests this. The main research question we wish to answer is: To what extent (if at all) does participation in a deliberative process change populist attitudes among citizens, directly, via the perceived quality of deliberation and/or via evaluations of the organization? To answer this question, we conduct a structural equation model analysis based on data from pre- and post-surveys handed out at a citizens’ assembly about more far-reaching climate policies in Gelderland (the Netherlands). Specifically, we zoom in on the first day that included small-group deliberation. We find that populist citizens did become less populist at the end of that day, but that the indirect paths via deliberation or evaluations of the organisation were not significant. We also find that citizens’ assemblies can actually increase populist attitudes. In line with the literature on outcome favorability, climate skeptics became more populist at the end of the day. This study makes contributions to both the populism and the democratic innovations literature. It adds to the literature on populism by studying not simply the causes or effects of populist attitudes, but also examining what changes populist attitudes. It adds to the literature on democratic innovations by being the first to study the effects of participating in a citizens’ assembly of populist attitudes and thereby offering an empirical test of the claim that deliberation can ‘remedy’ populism. Lastly, this study shows that democratic innovations in the form of deliberative events are no panacea and can actually backfire for some participants.

Theoretical framework: populism meets deliberation

Both deliberation and populism are big and sometimes controversial concepts. Fully unpacking them can thus be a tricky endeavour and requires book-length discussions about their precise nature and meaning. In this article-format study we have to be humbler, and take a pragmatic approach: given that we want to know the potential impact of deliberation on populist citizens in practice, we mainly focus on that subset of the literature on deliberation that deals with deliberation in practice (i.e. as a feature of actual democratic innovations), and on that subset of the literature on populism that deals with populism from a citizens’ perspective (i.e. the ideational approach to populism, operationalised in a set of populist attitudes) (Kaltwasser et al., Citation2017).Footnote3 After discussing the two concepts, we apply insights from the deliberation and populism literature to develop a framework to examine to what extent and how deliberation may counteract (or reinforce) populism at the citizen-level.

Starting point: the potential of deliberation

Deliberation starts from a pluralistic view of society and centres on ‘[m]utual communication that involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values, and interests regarding matters of common concern’ (Mansbridge, Citation2015, p. 27). At its core, deliberation ‘entails civility and argumentative complexity’ (Dryzek et al., Citation2019) and is founded ‘on argumentative exchanges, reciprocal reason giving, and on public debates which precede decisions’ (Floridia, Citation2014, p. 305). It is in essence, ‘talk-centric’ or discursive in nature (Chambers, Citation2003).

In practical democratic innovations, deliberation can materialise at the level of the ‘mode of participation’ and the ‘mode of decision-making’ (Elstub & Escobar, Citation2019, p. 25).Footnote4 As a mode of participation, deliberation encompasses listening, openness to persuasion and discursive expression. Equal participation, mutual respect and reasoned argument form the core of the deliberation (Harris, Citation2019, p. 48). As a mode of decision-making, it is the opposite of simple voting and involves the exchange of arguments and discursive decision-making. While the ideal level of deliberation not always reached in practice, many ‘micro-design choices’ are typically made to enable it as much as possible. Facilitators play an important role in ensuring that everybody at the table has a chance to speak and be listened to, as does the practice of allowing for small group discussions. Another important feature is the provision of information often by experts, ideally presented in ‘clear, plain language’ (Harris, Citation2019, p. 51).

What effects can participating in deliberative processes have? Some might say participation may well have no effect at all. After all, one of the main insights of the recent literature on democratic innovations is that outcome favourability plays a role in how participants perceive the process and its outcomes (and correspondingly what effect participation can have on them). Indeed, people tend to favour and are influenced by procedures that deliver the outcomes that they wanted to begin with (Arnesen, Citation2017; Beiser-McGrath et al., Citation2022; Werner, Citation2020). Nevertheless, even when this factor is considered, deliberation can still have effects on participants.

At a general level, deliberation can have an impact on political attitudes, behaviour, and capabilities (Van der Does & Jacquet, Citation2023). In this study we are interested in the potential impact on populist attitudes, one specific type of political attitudes, so we will zoom in on the empirical literature analysing the effects of deliberation on political attitudes. There are quite a few studies on this topic: it is the most examined area of the effects of deliberation (Jacquet & van der Does, Citation2021, p. 134). Several meta-reviews exist (Boulianne, Citation2019; Gastil, Citation2018; Michels, Citation2011; Theuwis et al., Citation2021; Van der Does & Jacquet, Citation2023). Empirically, the picture that emerges is that experiencing deliberation often has a positive effect on political attitudes. Participating in a deliberative process lets citizens experience the need for compromises and trade-offs in order to reach an outcome (cf. Boulianne, Citation2019, p. 6). Importantly, ‘deliberative events might foster a feeling among participants that their perspectives are being taken seriously by decision-makers and that their interests are being fairly represented within the political process’ (cf. Boulianne, Citation2019, p. 6). It also shifts the focus from a pure representative logic to one where there is room for citizens to contribute more directly. In sum, the mere existence and experience of a deliberative event can already have an effect. Clearly, there are objective elements to reaching a higher quality of the deliberation, such as the micro-design choices mentioned earlier. However, other studies have highlighted that in order for deliberation to have an actual effect on political attitudes, a higher quality of deliberation also needs to be perceived as such by the participants (cf. Gastil, Citation2018, p. 281).

Populism and deliberation in theory: an uneasy relationship

Before being able to apply the aforementioned insights to populism, we first dig deeper into populism at the citizen level. Following Mudde’s seminal definition, populists consider ‘society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus the “corrupt elite,” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Citation2004, p. 543).Footnote5 This definition includes an element of people-centrism and one of anti-elitism. These two core elements are connected together via the notions of popular sovereignty (the people should rule, not the elite) and Manicheanism (a black and white view of society: the people are good, the elite is evil). Whereas populism in parties is often described as an ideology, a strategy or even a communication style, for citizens it is a set of ideas, a lens through which they view political reality (cf. Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 97).Footnote6 Applied to deliberation, this means that populists pay special attention to different behaviours and actions of other citizens, organisers or politicians involved in deliberative processes. They notice different things and interpret them in their own way.

For populists, the people are ‘good’ and ‘pure’. Contrary to the notion of a pluralistic society central in theories of deliberation, populists view the people as homogenous: ‘a single entity devoid of fundamental divisions and unified and solidaristic’ (Taggart, Citation2000, p. 92).Footnote7 Similarly, populists do not see the need for discursive exchanges: ‘[t]he people’ are, in populist thinking, already fully formed and self-aware’ (Taggart, Citation2000, p. 92). Neither do they feel the need to acquire information from experts. When it comes to reasoning and informed opinions, populists ‘see wisdom as residing in the common people. From common people comes common sense and this is better than bookish knowledge’ (Taggart, Citation2000, pp. 94–95). Moreover, they have a Manichean, black and white view of society, a world divided between friends and foes. This entails that the phrase that the people ‘have had enough of experts’ may not be true per se, but rather that for populists there is no such thing as ‘an expert’. Instead you have our experts, and their experts: the ones that know the people and are with us, and the ones that serve the elite and are against us. Populists are also skeptical of procedures. They ‘love transparency and distrust mystification, they denounce backroom deals, shady compromise, complicated procedures, secret treaties and technicalities only experts can understand. All this complexity is a self-serving racket perpetuated by professional politicians’ (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 5). As a result, ‘[s]traightforwardness, simplicity and clarity are the clarion calls for populists’ (Taggart, Citation2000, p. 97).

Yet, at the same time deliberative processes are also an opportunity to be listened to by other citizens and be taken seriously by them. Moreover, deliberation is embedded in political reality. Participating in deliberative processes can bring populist citizens into contact with politicians and if these politicians show a serious commitment to the process, it may reduce feelings that politicians are ‘enemies of the people’. Furthermore, by definition, deliberation is a way to involve citizens in decision-making and take (some) power back from the elites. It can give them a genuine voice (cf. Curato & Parry, Citation2018, p. 3), something that is likely to be appreciated by populists. After all, populists feel their voice is the voice of the silent majority, a voice that is not listened to. As such, deliberative processes may well have the potential to counter the feeling of the lack of responsiveness that is often seen as fuelling populism (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 101).

The practice of populist citizens experiencing deliberation

As mentioned above, the mere act participating in an actual deliberative event can already have an effect because it signals to citizens that they are being taken seriously. This holds especially for populists, a group of citizens who care particularly about how (political) elites treat them. Our first, simple hypothesis is therefore:

H1. Populist citizens participating in a deliberative citizens’ assembly become less populist, compared to non-populist citizens.

Building on the premise that populism among citizens acts a lens through which citizens view reality, it matters first and foremost how populist citizens perceive and view the quality of deliberation with their fellow-citizens. As such, one can expect the way people enter (i.e. populist attitudes right before the start of the day) affects how they perceive the quality of the deliberation and this in turn affects whether their populist attitudes change (and in which direction). While the presence of facilitators may ensure that everybody’s voices are heard, in practice this do not always work well, which in turn may backfire (cf. supra). As there are both reasons to expect a positive effect and reasons to expect a negative one, we formulate no explicit direction of the effect in our hypothesis:Footnote8

H2: Populist citizens participating in a deliberative citizens’ assembly are likely to perceive the quality of the deliberations differently compared to non-populist ones, and this in turn is likely to affect their change in populist attitudes.

H3: Populist citizens participating in a deliberative citizens’ assembly are more likely to be negative about the organization compared to non-populist ones and this in turn is likely yield an increase in populist attitudes.

Method and data

Based on our theoretical framework, we can thus expect that being a populist influences how one views the interactions with fellow-citizens and the broader political-institutional context. This then in turn influences a potential change in populist attitudes. In short, we theoretically expect a set of mediation effects. To test our hypotheses, we therefore carry out a mediation analysis by using structural equation modelling (SEM). We do so for two reasons. First, SEM allows us to test direct and indirect effects between several pathways in a single model (Kline, Citation2016). Classic regressions are possible, but then multiple models have to be run separately. Given that we have two mediators, using regression models becomes cumbersome and unwieldy. A second reason is that one of our mediators is a latent variable (perceived quality of the deliberation), and one of the key advantages of SEM is that it is well-suited to deal with latent variables (Kline, Citation2016, p. 12).Footnote9 Below we discuss the case, data collection and operationalisation in more detail.

Democratic innovation type and case

To test our hypotheses, we collected data at an actual case of deliberation. While there are several ‘families’ of democratic innovations, the one that focuses most on deliberation is the mini-public. We therefore selected a mini-public, specifically a citizens’ assembly held in the province of Gelderland (the Netherlands). The citizens’ assembly we studied gathered 152 citizens from across the province to deliberate on the provincial policies regarding climate mitigation.Footnote10 It is thus an example of a growing body of mini-publics that deal with the climate question. The participants were drawn by lot. The sortition procedure consisted of two steps. First, 30,000 citizens were randomly selected and invited. Of the 3300 who answered positively, 160 were selected via stratified random sampling (in order to be representative regarding age, gender and education in particular). 152 citizens participated in the first session. The citizens’ assembly took place from September to December 2022 and consisted of four full-day sessions, one per month. The first day consisted of getting the necessary background information and getting acquainted with the other participants. The second one consisted of getting expert information, input from online consultations and group deliberation in groups of six. All tables had a professional facilitator and composition of the tables (randomly) rotated once during the day. Given that this second day was the first time the participants actually deliberated we decided to examine this particular day in our SEM analysis. The third session also consisted of deliberations and expert information, now focused on specific sub-topics where groups had to craft recommendations on the topics at hand. Again, the group discussions involved moderation and rotation (though not random this time, but based on first and second preferences for topics). The final session dealt with finishing the recommendations in small groups and plenary voting on the 44 detailed policy recommendations.

As such, the Gelderland citizens’ assembly was a typical citizens’ assembly in terms of its key features: the selection of participants was based on sortition, the activities of the assembly consisted of information gatherings (with presentations by experts and stakeholders), small group-moderated deliberations (led by independent professional facilitators) and consultation (via online polls). The result consisted of detailed policy recommendations. All of this is in line with the key characteristics of a typical citizens’ assembly (cf. Harris, Citation2019, pp. 46–47). When comparing the Gelderland assembly to other climate-related citizens’ assemblies, is again a typical case in terms of key features, such as timing remit, the number of participants and internal practices (Boswell et al., Citation2023, p. 187). In terms of commissioner, at first glance it stands out as the Gelderland assembly was commissioned by the provincial parliament (rather than the executive), but in practice the citizens’ assembly was supported by the provincial executive as well, signalling broad support to the participants. The main difference is that this assembly took place at the provincial level, rather than the national or local one. Substantively this made sense – the Dutch provinces have substantial competences in terms of climate policies. However, one should note that citizens’ knowledge of and experience with provincial politics is relatively limited, which may potentially influence the effects of participating. We discuss this in the conclusion when we address the limitations of this study.

Data collection and operationalisation

We surveyed the participants twice each day (paper survey, right before and right after). We first surveyed them when they entered the room. In these questionnaires, we included a standard battery measuring populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014). At the end of the day right before they left the room, we surveyed them a second time and asked a series of questions about that day of the deliberative event, alongside the same populist attitudes items.Footnote11 As said, for this study we use the data collected the second day (i.e. the first time they embarked on deliberation). That second day 141 participants were present, all of whom had participated in the first day as well. The response rates were 94.3% and 90.1% respectively (133/141 and 127/141).Footnote12 The pre- and post-measurement right before and right after increases the confidence that any change in populist attitudes is due to what happened during the day. The programme was intensive and the participants did not leave the building in-between. Nevertheless, theoretically we cannot rule out that a participant browsed their mobile phone during a coffee break or lunch to look at news sites. Given that no major events happened that day, it seems unlikely that participants were influenced by external factors even if they consumed news.Footnote13

Dependent variable: change in populist attitudes. Populist attitudes are measured using the six items originally developed in the article by Akkerman et al. (Citation2014). lists the six populist attitudes items. For each of these, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with the statement on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Our dependent variable is change in populist attitudes, calculated by subtracting the average populist attitudes score at the end of the day from the average at the start of the day.

Table 1. Items measuring populist attitudes.

As they are considered attitudes, populist attitudes are typically measured using scales. Several scales have been developed (for an overview see: Wuttke et al., Citation2020 or Castanho Silva et al., Citation2020). For this study, we opted for the Akkerman et al. (Citation2014) scale as it aligns best with the theoretical holistic notion of populism as a lens through which (populist) citizens perceive reality. As said, other scales exist, but are less aligned with this notion of populism as a lens. Indeed, the Akkerman et al. (Citation2014) scale has a holistic, non-compensatory approach to measuring populism, often encompassing multiple elements of populism at once in one item (cf. Wuttke et al., Citation2020, p. 361).Footnote14

Independent variables

Populist citizen. The studies upon which our theoretical framework is built, speak of how ‘populists’ relate themselves to deliberation (e.g. Canovan, Citation1999; Mudde, Citation2004), hence in line with these studies, we transform a respondent's populist attitudes score to a dummy. This also has the additional added value of yielding results that can be easily interpreted. We put the threshold at 3.5/5. Obviously, any threshold is always going to be arbitrary to a certain extent, so we ran a robustness check where we include the full populist attitudes scale.Footnote15

Deliberation. The post-questionnaire included four questions that inquire about how the respondent perceived the group deliberations (cf. Caluwaerts, Citation2016). They inquire to what extent the respondent thought the small-scale discussions entailed equal participation, mutual respect and listening (cf. theoretical section).Footnote16 Specifically, the following questions were asked (likert scales, completely disagree to completely agree):

I had ample opportunities to express my opinion during the discussions

In general, the group discussions were respectful

The opinions of other participants did not differ much from my own opinions

I have changed my mind as a result of the discussions

Negative evaluation of the organisation. The post-questionnaire included an open question inquiring which elements of the event the respondent liked, and which she disliked. We coded these answers scoring a ‘1’ when the respondent mentioned a negative aspect of the organisation that entailed influencing the participants. Specifically, we examined whether the respondent negatively mentioned words/deeds of the politician, civil servants and facilitators that entailed pressuring citizens or not taking them seriously. Excluded were: the quality of the cake or coffee, complaints about the location or time constraints. All of these were scored ‘0’. An example of a score ‘1’ is: ‘Crucial topics were missing (…). This pressures participants in a certain direction.’ An example of a ‘0’ is: ‘the room was noisy’.Footnote17

Climate skepticism. As mentioned in the theoretical section, whether participants get ‘the outcomes’ that they want to begin with – outcome favourability – can influence how they perceive the process, and what effect participation has. Hence, it is an important factor to include in any study of effects of democratic innovations. How to apply that to the case we study? The second day of citizens’ assembly in Gelderland did not yield a specific outcome (that came later in the process), but the citizens’ assembly started from the point that climate change was happening and was man-made.Footnote18 If a respondent is climate skeptic in the sense that (s)he doubted the evidence of man-made climate change, the outcomes of the assembly, whatever they were specifically, would go against that. Hence, we measured climate skepticism at the start of the day to capture outcome favourability. The item we use is one that specifically taps into the respondents’ view regarding the assumption underlying the Gelderland citizens’ assembly that man-made climate change is happening. The specific question was the following: Which statement resembles your personal opinion the most? (1) the climate changes mainly due to human actions, (2) the climate changes, whereby human actions play a small role (3) the climate changes, but not due to human actions and (4) the climate is not changing. All but the first are indications of (a degree of) climate skepticism (cf. Van Rensburg, Citation2015).

Next to these substantive variables, we control for age, gender and highest education attained. shows the descriptives of the variables included in the models.

Results

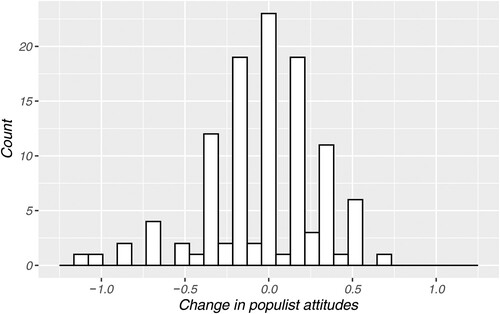

Before we move to the main analysis, we first zoom in on populism among the participants and how that changed after the second day of the citizens’ assembly. One could wonder whether populist citizens attend citizens’ assemblies to begin with. This was the case in Gelderland: at the start of the second day, 35% of the respondents could be considered populist citizens. There was also a wide range in terms of the degree of populist attitudes at the start of that day: the lowest value was two, the highest five (on a scale from one to five). At the end of the second day of the Gelderland citizens’ assembly, the majority of the respondents changed in terms of populist attitudes.Footnote19 shows the distribution of our dependent variable, change in populist attitudes. All in all, the variable is clearly normally distributed, with more values below zero than above, as is reflected in the negative mean value (−0.035).

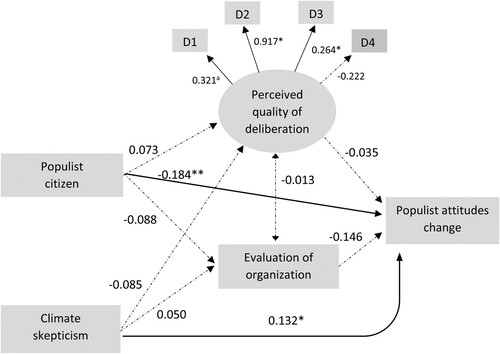

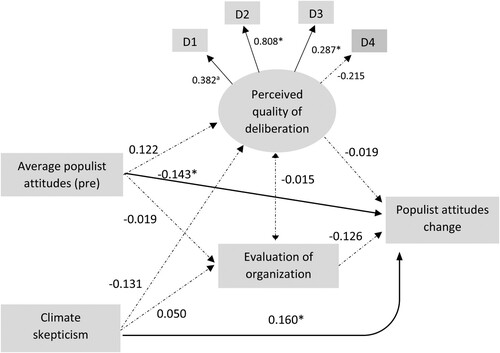

Moving to our main analysis, shows the coefficients and factor loadings for our measurement model. We use the standard goodness-of-fit measures to assess the model fit. Taken together they suggest that the model fits the data sufficiently well. The χ2 statistic is insignificant, which indicates that the model fits the sample well. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.95) and the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < 0.06) also indicate a good fit. The model includes one latent variable, perceived quality of the deliberation.

Figure 2. Indirect model of populist attitudes change.

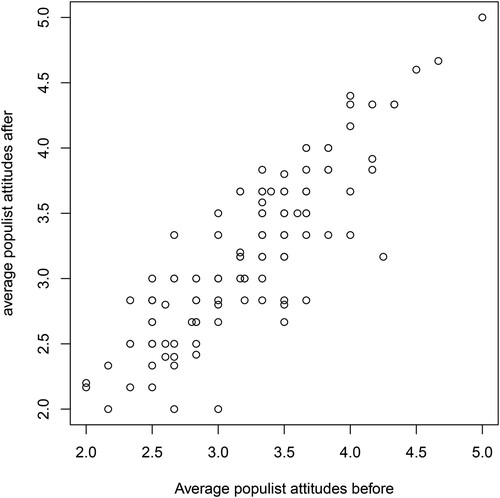

Notes: N = 105. aNo significance level because factor loading is fixed for identification purposes. The estimates for D1–4 are standardised factor loadings. Double-arrowed lines indicate covariances. Dotted lines indicate insignificant effects, bold lines indicate statistically significant effects (p < 0.05); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Goodness of fit: χ2 = 16.075 (df = 23, N = 105), p-value = 0.852; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.000; SRMR = 0.040. Indirect effects and total indirect effects are reported in Appendix 2. Endogenous variables are controlled for gender, age, and education. Control variables are excluded for visualisation purposes. Some might advance that the significant direct effect of the ‘populist citizen’ variable may be due to a ceiling effect. Indeed, if a sizable chunk of the respondents already has the maximum score on populist attitudes, they can increase no further, making it more likely that we find a significant negative effect. Related, others may advance that these results may be driven by a process of regression to the mean, whereby due to random error extreme scores tend to moderate when the same unit/respondent is measured over time (Barnett et al., Citation2005). This may make natural variation look like real change. To examine these, we checked whether a sizable chunk of our respondents scored the maximum score on average populist attitudes in the pre-questionnaire and we checked whether these high scorers saw large drops in average populist attitudes. Specifically, we looked at the populist attitude scores in the pre-questionnaire, and examined their populist attitude change (cf. Appendix 2.4, which also includes a scatter plot showing average populist attitudes before and after). Only one respondent scored the maximum score on average populist attitudes in the pre-questionnaire and their populist attitudes did not change at the end of the day. The second-highest score was a score of 4.67/5, and again did not change. The third highest was 4.5/5. This respondent actually increased slightly (+0.1). As such, both the ceiling effect and regression to the mean seem unlikely to account for the effects found: the number of respondents scoring a maximum or even close to maximum score is too limited for that (versus ceiling effect) and the high-scoring respondents’ scores remained stable or even slightly increased (versus regression to the mean). As an extra robustness check, we also ran a T-test which indicated that the difference in populist attitudes change between populist and non-populist citizens was significant (–0.144, p < 0.05).

The results of our model indicate that a change in populist attitudes is most notably linked to two variables: being a populist citizen and the degree of climate skepticism. In line with H1, the direct effect of being a populist citizen is negative and significant (−0.184, p < 0.01). Counter to hypothesis 2 and 3, none of the indirect paths is significant. This indicates that at the end of the day, populist citizens became less populist, compared to non-populist citizens, but that this is not due to a negative evaluation of the organisation or the perceived quality of the deliberation.

At least three interpretations of this result are possible. A first one may be related to the operationalisation of the perceived quality of the deliberation. The questions used do tap into several theoretical aspects of the group discussions mentioned in our theoretical overview. However, other elements of deliberation can be thought of (e.g. the exposure to information of experts or the degree of nuance of the argumentation). Moreover, the questions we use may be too specific to capture differences in perceived quality of the deliberation. However, this may account for the measures regarding deliberation, but this does not apply to the variable capturing the evaluation of the organisation. Nevertheless, this pathway is also insignificant. This suggests something else may be at play. A second interpretation is that methodologically, there simply was not enough variance to explain. As shows, most respondents agreed on the items measuring the perceived quality of the deliberation and the evaluation of the organisation, as is nicely illustrated by the relatively low standard deviations for the questions about deliberation and the low proportion of respondents that was negative about the organisation. All in all, the overwhelming majority of the participants was content with the group discussion and the organisation. This leads us to a third interpretation: may be the actual practice of a citizens’ assembly works as a ‘grand treatment’ by itself signalling that political elites (at least in the short term) are taking everybody seriously.Footnote20 While this may be in line with original perceptions of non-populist citizens, it goes against the populist worldview. Indeed, one of the core elements of the populist set of ideas is that the elite is self-serving, corrupt and, most importantly, unresponsive (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 101). This in turn would explain why populist citizens’ degree of populist attitudes drops compared to those of non-populists.

Table 2. Descriptives.

Next to populism, the initial degree of climate skepticism of a respondent also played a role. In line with the literature on outcome favourability, the more a respondent was a climate skeptic, the more their populist attitudes actually increased. Here as well, the indirect pathways do not mediate this relationship: skepticism had no significant effect on the perceived quality of the deliberation or the evaluation of the organisation.

As a robustness check we examined if the effect of populism holds when climate skepticism is not included in the analysis (see Appendix 2.2). This is the case: the results are similar and the direct effect of being a populist citizen persists and is roughly the same (−0.160; p < 0.05). This suggests that the two variables thus seem to add up rather than eat away at each other, something that has also been observed in the context of referendums (cf. Werner & Jacobs, Citation2022). As an additional, exploratory analysis, we also checked if climate skepticism moderates the effect of populism (see Appendix 2.3). This is not the case, suggesting that outcome favourability in the form of climate skepticism affects populists and non-populists in the same way.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined whether populist citizens became less populist after participating in a deliberative event. Our main research question was: To what extent (if at all) does participation in a deliberative process change populist attitudes among citizens, directly, via the perceived quality of deliberation and/or via evaluations of the organization? Our results suggest that populist citizens indeed become less populist compared to non-populist citizens, but we do not find evidence that this occurs via their perceived quality of the deliberation or their evaluation of the organisation. To return to the quote that started this study, there does seem to be some merit in the ‘faith in the transforming power of deliberation’ regarding populism, but perhaps more as a grand treatment – participation in a deliberative event – rather than in the form of small-group deliberations. Our study also showed that outcome favourability matters and that participation in a deliberative event can actually increase populist attitudes. By doing so this study adds to both the literature on populism and the study of democratic innovations as a ‘remedy to the ills of democracy’.

Above we already mentioned some potential limitations of our study. Reflecting on these limitations, we wish to suggest five ways forward. (1) While our case is a typical case of a (climate) citizens’ assembly, it took place at the provincial level instead of the local or national one. Citizens’ experience with and knowledge of the provincial level is relatively limited. As a result, the participants may have been more open to be influenced during the participation as their views of provincial political ‘elites’ may have been less crystalised and more open to change. Hence, while we expect our findings to travel to other cases of climate assemblies, the size of the effect may be different in local and/or national cases. Further studies replicating our study at the local and national level are thus needed. (2) Another way forward concerns our operationalisation. The operationalisation of the perceived quality of the deliberation that we used, can be improved. This can be done in particular by adding items covering the element of reason-giving. Other specific elements of deliberation can also be added, such as exposure to information of experts or the degree of nuance of the exchanged argument. (3) Next to the operationalisation, it is important to note that we examine short-term effects in a citizens’ assembly, effects of participation in one session. It remains to be examined whether similar patterns occur after the complete event. A important venue for further research is therefore to analyse effects of the complete event, surveying the participants before the start of the event and afterwards; while collecting data on a control group alongside. This way, a difference-in-difference analysis can be carried out as to examine what the effect is of several days of deliberation. (4) The ‘stickiness’ of the effect is a fourth important topic for further research. Indeed, citizens’ assemblies typically are advisory. One can expect that if the outcome of the citizens’ assembly is simply ignored, this may undo or even reverse reductions in populist attitudes (see also Van Dijk & Lefevere, Citation2023). Examining effects after the follow-up of the event is thus useful. (5) A final promising venue for future research is populism outside the mini-public. How does the maxi-public react to deliberative events being held? Are they more likely to support its outcomes? Does it reduce their feelings that citizens are not being heard? Or does the effect of deliberation only materialise when one is submerged in it? Similar questions can be asked regarding populist parties. How do populist parties react to citizens’ assemblies and their outcomes?

Almost 25 years after the original observation by Canovan that deliberative theorists often assume that deliberation reduces populism – almost like an argument of faith. Much remains to be examined, but our analyses nevertheless offer a first suggestion that there may be some empirical merit to that argument of faith.

Ethics approval

This research has been approved by the Radboud Faculty of Management Sciences Ethics assessment committee (EACLM) on 30 September 2019 (reference: ECFLM Ref. No: 2019.05).

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for input and help with the data collection from Rosa Kindt, Marie Theuwis, Heleen Osse and Koert Rang.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kristof Jacobs

Kristof Jacobs is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science (IMR, Radboud University). His research focuses on contemporary challenges to democracy, the responses to them, and whether these responses work as proposed (or not). One of these challenges to democracy is populism, one of the responses to populism is to implement democratic innovations. Whether or not these innovations work as proposed, is his current research focus. He was the director of the Dutch 2016 and 2018 national referendum study and the co-director of the 2021 and 2023 Dutch national election study.

Notes

1 There is strong and consistent evidence that populist attitudes have a significant effect on voting for populists (Marcos-Marne et al., Citation2023). However, not all populist citizens vote for populist parties (yet). Indeed, it may well be that there is only a right-wing populist party available, leaving left-wing populist citizens without a viable populist option to vote for. Moreover, some voters for populist parties vote for such parties because they support its leader or the substantive policies that party advocates. Hence, when studying the effect of deliberation on populism, it is more accurate to focus on populist attitudes among citizens directly rather than via the proxy of voting for populist parties.

2 It should be noted that this does not mean citizens with a higher degree populist attitudes are a danger to democracy as such, and the overall picture that emerges is a complex one, better ‘described by lights and shades rather than as a clear threat to it’ (Marcos-Marne et al., Citation2023, p. 7). Indeed, studies have found that such citizens do support democracy as an ideal, but are dissatisfied with democracy in practice and favour more direct forms of government, such as referendums (Zaslove et al., Citation2021). Hence, we prefer to speak of ‘challenge’ rather than ‘danger’ or ‘threat’.

3 For a broader and more in-depth discussion on deliberation and deliberative democracy, one can look at, among others (Bächtiger et al., Citation2018; Burkhalter et al., Citation2002; Gutmann & Thompson, Citation2004; Myers & Mendelberg, Citation2013). For a broader and more in-depth discussion on populism, one can look at, among others (Canovan, Citation1999; Kaltwasser et al., Citation2017; Mudde, Citation2004; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017; Taggart, Citation2000).

4 Note that the authors only formally label it deliberation in the mode of decision-making.

5 There is still debate in the literature about the ontology of populism when applied to political parties – some scholars consider populism to be a strategy, others a communicative style and still others consider it a thin-centered ideology (cf. Kaltwasser et al., Citation2017). However, when studying populism among citizens such debates do not occur for the simple reason that citizens are not in the business of getting elected, it makes little sense to consider populism an electoral strategy or communication style of them.

6 Note that considering populism as a ‘lens’ through which a citizen views society implies a holistic approach to populism, where its different elements come together, rather than are treated as separate sub-dimensions existing alongside each other.

7 It should be noted that scholars studying left-wing populist parties have shown that this is also a matter of degree: some variants of populism exhibit a more inclusionary and pluralist conception of the people, and the people can be defined in a less or more pluralist way (Katsambekis, Citation2019). The two thus need not necessarily be at odds: even for left-wing populists there are no fundamental divisions between the people. The different groups constituting ‘the people’ may have different ideas, but share the same interests (cf. Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2013).

8 Empirically this means we only expect to find (1) a significant relationship between being a populist citizen and perceived quality of the deliberation and (2) a significant relationship between perceived quality of the deliberation and change in populist attitudes.

9 As a robustness check we conducted an OLS regression excluding the mediators. Where applicable (i.e. to estimate the direct effect), the results are similar to those of the SEM analysis.

10 The question the participants had to answer was three-fold: Which key dilemma's do citizens perceive regarding the climate policies of Gelderland, how can we address them and how can we make broadly accepted climate policy choices? (Gelders Burgerberaad Klimaat, Citation2023, p. 20).

11 At the end of the first day we did not ask the populism items.

12 The fairly low number of cases may influence the efficiency of our estimator. Specifically, there is an increased risk of type II errors – or: false negatives. If we find insignificant effects for some variables, it is thus possible that this is due to the lower number of cases.

13 In terms of news relevant to climate or environmental discussions that appeared in the media on the day the session was held, the government announced that it would accept some of the outcomes of negotiations between the government and farmers (indicating responsiveness on the topic), who had protested during the summer, while some other recommendations were to be investigated further (indicating a lack of responsiveness on the topic). All in all, the statement did not attract a lot of media attention. Due to the fairly low-key nature of the announcement and the mixed message as well as the assumption that participants must first have noticed it, it is unlikely to have influenced our study in a significant way, though obviously we cannot rule it out completely.

14 One corollary of this is that the scale does not allow to investigate effects on the different sub-dimensions/elements of populism.

15 A robustness check including the whole populist attitudes scale shows that this does not change the results: the full scale also has a significant effect (coefficient = –0.143, p < 0.05).

16 Of the three concepts, listening is the most difficult to capture, so we included two items regarding this element. Item four of our battery showed the least variance (cf. below): most people indicated they did not change their minds as a result of the discussions. We nevertheless decided to keep it for reasons of content validity: openness to persuasion and opinion change based on argumentation are considered important elements of deliberation (cf. Dryzek et al., Citation2019).

17 Two coders coded the data. In a first iteration, Krippendorf’s Alpha was 0.561, below the threshold of being acceptable. It turned out that the two coders had a different interpretation of when to code remarks about the program and the selection of experts as a ‘1’or ‘0’. The codebook was refined, in line with the theory: both subjects were coded a ‘1’ when the program/selection of experts was linked to an attempt of the organization to pressure respondents in a certain direction. Afterwards, the coders did a second round of coding. The Alpha increased to a level that was acceptable (0.834). Remaining disagreements were solved on a case-by-case basis by each coder outlining the arguments for their coding of that specific answer, followed by deliberation and a decision based on consensus.

18 Conceptually, one can distinguish between three types of climate skepticism: evidence skepticism (doubting whether man-made climate change exists to begin with), process skepticism (doubting the process and motives of the scientific process leading to this evidence) and response skepticism (doubting the efficacy of climate mitigation/adaptation measures; cf. Van Rensburg, Citation2015). The three can be related, but need not automatically be: one can firmly believe that man-made climate change is happening, but still doubt the efficacy of climate mitigation policies. Within the Gelderland citizens' assembly, there was room for process skepticism and response skepticism, but not for evidence skepticism. Hence, we specifically measure evidence skepticism.

19 More information about the distribution of respondents' populist attitudes before and after can be found in the scatterplot in Figure A4 in Appendix 2.

20 Or the effect runs via different mechanisms such as exposure to expert information or the degree of nuance of the argumentation. We return to this point in the conclusion.

21 Here, we use the average for the populist attitudes items, as we use that variable as the basis to compute the populist citizen-variable we use in . By using the average, and Figure A1 are can be compared more easily. To be complete, we also ran a model using populist attitudes as a latent variable, which shows similar effects: a negative effect of populist attitudes on change in populist attitudes (–0.258; though p < 0.1, namely: p = 0.095) and no effect on deliberation and evaluation of the organization. In this model as well, climate skepticism has a significant, positive effect on change in populist attitudes (0.142; p = 0.045).

22 We exclude the pathways (i.e. deliberation and evaluation of the organization) from this analysis. Adding moderator effects in SEM models can be demanding for the data, which is especially a concern given the medium size N we have. Additionally, none of the pathways showed a significant effect in our main analysis. Hence, we decided to exclude them from this moderator analysis.

References

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Arnesen, S. (2017). Legitimacy from decision-making influence and outcome favourability: Results from general population survey experiments. Political Studies, 65(1_suppl), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716667956

- Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J., & Warren, M. E. (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford University Press.

- Barnett, A. G., Van Der Pols, J. C., & Dobson, A. J. (2005). Regression to the mean: What it is and how to deal with it. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(1), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh299

- Beiser-McGrath, L. F., Huber, R. A., Bernauer, T., & Koubi, V. (2022). Parliament, people or technocrats? Explaining mass public preferences on delegation of policymaking authority. Comparative Political Studies, 55(4), 527–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211024284

- Boswell, J., Dean, R., & Smith, G. (2023). Integrating citizen deliberation into climate governance: Lessons on robust design from six climate assemblies. Public Administration, 101(1), 182–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12883

- Boulianne, S. (2019). Building faith in democracy: Deliberative events, political trust and efficacy. Political Studies, 67(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718761466

- Burkhalter, S., Gastil, J., & Kelshaw, T. (2002). A conceptual definition and theoretical model of public deliberation in small face-to-face groups. Communication Theory, 12(4), 398–422.

- Caluwaerts, D. (2016). Evaluatierapport: Publiek Debat over de Eindtermen. Vlaamse Overheid.

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Castanho Silva, B., Jungkunz, S., Helbling, M., Littvay, L. (2020). An empirical comparison of seven populist attitudes scales. Political Research Quarterly, 73(2), 409–424.

- Chambers, S. (2003). Deliberative democratic theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085538

- Curato, N., & Parry, L. J. (2018). Deliberation in democracy’s dark times. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 14(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.304

- Dryzek, J. S., Bächtiger, A., Chambers, S., Cohen, J., Druckman, J. N., Felicetti, A., Fishkin, J. S., Farrell, D. M., Fung, A., Gutmann, A., Landemore, H., Mansbridge, J., Marien, S., Neblo, M. A., Niemeyer, S., Setälä, M., Slothuus, R., Suiter, J., Thompson, D., & Warren, M. E. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science, 363(6432), 1144–1146. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694

- Elstub, S., & Escobar, O. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of democratic innovation and governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Floridia, A. (2014). Beyond participatory democracy, towards deliberative democracy: Elements of a possible theoretical genealogy. Rivista italiana di scienza politica, 44(3), 299–326.

- Gastil, J. (2018). The lessons and limitations of experiments in democratic deliberation. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 14(1), 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113639

- Gelders Burgerberaad Klimaat. (2023). Gelders burgerberaad klimaat 2023 en verder. Samen voor de toekomst. https://media.gelderland.nl/Gelders_Burgerberaad_Klimaat_2023_en_verder_digitaal_d8e835738e.pdf?updated_at=2023-01-30T10:45:10.689Z

- Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D. (2004). Why deliberative democracy? Princeton University Press.

- Harris, C. (2019). Mini-publics: Design choices and legitimacy. In S. Elstub & O. Escobar (Eds.), Handbook of democratic innovation and governance (pp. 45–59). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Heinisch, R., & Wegscheider, C. (2020). Disentangling how populism and radical host ideologies shape citizens’ conceptions of democratic decision-making. Politics and Governance, 8(3), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i3.2915

- Huber, R. A., & Schimpf, C. H. (2017). On the distinct effects of left-wing and right-wing populism on democratic quality. Politics and Governance, 5(4), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v5i4.919

- Jacquet, V., & van der Does, R. (2021). The consequences of deliberative minipublics: Systematic overview, conceptual gaps, and new directions. Representation, 57(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2020.1778513

- Kaltwasser, C. R., Taggart, P. A., Espejo, P. O., & Ostiguy, P. (Eds.). (2017). The Oxford handbook of populism. Oxford University Press.

- Katsambekis, G. (2019). The populist radical left in Greece. Syriza in opposition and in power. In G. Katsambekis & A. Kioupkiolis (Eds.), The populist radical left in Europe (pp. 21–46). Routledge.

- Kline, R. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

- Mansbridge, J. (2015). A minimalist definition of deliberation. In P. Heller & R. Vijayendra (Eds.), Deliberation and development: Rethinking the role of voice and collective action in unequal societies (pp. 27–50). World Bank Group.

- Marcos-Marne, H., Gil de Zúñiga, H., & Borah, P. (2023). What do we (not) know about demand-side populism? A systematic literature review on populist attitudes. European Political Science, 22(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-022-00397-3

- Michels, A. (2011). Innovations in democratic governance: How does citizen participation contribute to a better democracy? Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives, 77(2), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.3917/risa.772.0275

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2013). Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Myers, C. D., & Mendelberg, T. (2013). Political deliberation. In L. Huddy, D. Sears, & J. Levy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 699–734). Oxford University Press.

- Ruth-Lovell, S. P., & Grahn, S. (2023). Threat or corrective to democracy? The relationship between populism and different models of democracy. European Journal of Political Research, 62(3), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12564

- Taggart, P. A. (2000). Populism. Open University Press.

- Theuwis, M., van Ham, C., & Jacobs, K. (2021). A meta-analysis of the effects of democratic innovations on citizens in advanced industrial democracies [ConstDelib Working Paper Series, No. 15 / 2021]. https://constdelib.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/WP15-2021-CA17135.pdf

- Van der Does, R., & Jacquet, V. (2023). Small-scale deliberation and mass democracy: A systematic review of the spillover effects of deliberative minipublics. Political Studies, 71(1), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211007278

- Van Dijk, L., & Lefevere, J. (2023). Can the use of minipublics backfire? Examining how policy adoption shapes the effect of minipublics on political support among the general public. European Journal of Political Research, 62(1), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12523

- Van Rensburg, W. (2015). Climate change scepticism: A conceptual re-evaluation. Sage Open, 5(2), 215824401557972. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015579723

- Werner, H. (2020). If I'll win it, I want it: The role of instrumental considerations in explaining public support for referendums. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12358

- Werner, H., & Jacobs, K. (2022). Are populists sore losers? Explaining populist citizens’ preferences for and reactions to referendums. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1409–1417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000314

- Wuttke, A., Schimpf, C., & Schoen, H. (2020). When the whole is greater than the sum of its parts: On the conceptualization and measurement of populist attitudes and other multidimensional constructs. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000807

- Zaslove, A., Geurkink, B., Jacobs, K., & Akkerman, A. (2021). Power to the people? Populism, democracy, and political participation: A citizen's perspective. West European Politics, 44(4), 727–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1776490

Appendices

Appendix 1. Supplementary data about the measurement model underlying

Table A1. Regression estimates of the measurement model.

Table A2. Direct, indirect and total effects of the populist citizen variable.

Appendix 2. Robustness checks and additional analyses

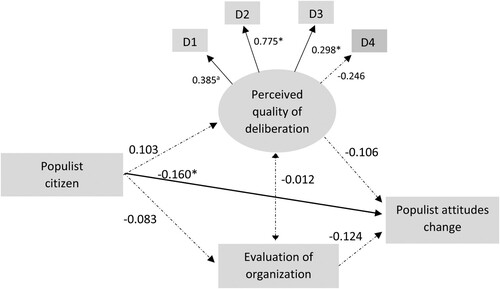

2.1. Robustness check: including the full populist attitudes scale

Below we show the results of the SEM analysis using the full populist attitudes scale. As Figure A1, shows, the results are very similar to those in .Footnote21

Figure A1. Indirect model of populist attitudes change (full populist attitudes scale).

Notes: N = 105. aNo significance level because factor loading is fixed for identification purposes. The estimates for D1–4 are standardised factor loadings. Double-arrowed lines indicate covariances. Dotted lines indicate insignificant effects, bold lines indicate statistically significant effects (p < 0.05); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Goodness of fit: χ2 = 20.096 (df = 23, N = 105), p-value = 0.636; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.000; SRMR = 0.046. Endogenous variables are controlled for gender, age, and education. Control variables are excluded for visualisation purposes.

2.2. Robustness check excluding climate skepticism

The analysis excluding climate skepticism again shows that the effects are similar (cf. Figure A2).

Figure A2. Indirect model of populist attitudes change (excluding climate skepticism).

Notes: N = 106. a No significance level because factor loading is fixed for identification purposes. The estimates for D1–4 are standardised factor loadings. Double-arrowed lines indicate covariances. Dotted lines indicate insignificant effects, bold lines indicate statistically significant effects (p < 0.05); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Goodness of fit: χ2 = 8.198 (df = 20, N = 106), p-value = 0.990; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.000; SRMR = 0.031. Endogenous variables are controlled for gender, age, and education. Control variables are excluded for visualisation purposes.

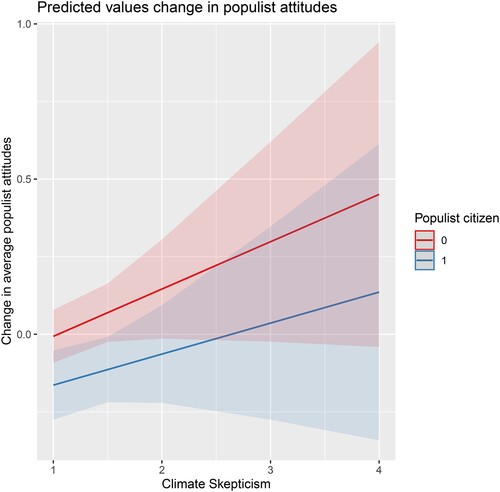

2.3. Examining whether climate skepticism moderates the effect of being populist

To test to what extent the effect of being a populist citizen is moderated by climate skepticism, we estimated a simple multivariate regression with the moderator effect.Footnote22 We find no significant effect of the moderator variable, indicating that the effect of skepticism is the same for populist and non-populist citizens alike. Theoretically, this suggests that populist citizens are not more (nor less) susceptible to instrumental motivations than their non-populist counterparts.

Table A3. Moderator model: populism * climate skepticism.

We also did an extra test visualising the moderator effect (Figure A3), which showed that the confidence intervals overlap for the full scale while the two axes remain almost parallel, again corroborating the absence of a moderator effect between populism and climate skepticism.

2.4. Ceiling effect and regression to the mean

To examine the ceiling effect we examined the highest scores in the dataset. To examine regression to the mean we looked at the highest scorers – all the respondents with an average score of 4.5 or higher on a scale from 1 to 5 (cf. ) and their change. We also analysed a scatter plot showing the before and after values (cf. Barnett et al., Citation2005, p. 217, see Figure A4). Again no clear signs of regression to the mean were found.

Table A4. Highest scores of average populist attitudes before and their change.