ABSTRACT

The idea of increasing the power of the ‘pure people’ at the expense of a ‘corrupt elite’ lies at the core of populism. One way for populist parties to do this is to push for a greater use of referendums. Previous research shows that populist parties mention in general in their communications the referendums as suitable avenues for the direct involvement of the people in the decision-making process. However, we miss details about how they refer to referendums. This article addresses this gap in the literature and explores how populist parties talk about referendums in their election manifestos. It seeks to identify what type of referendum populist parties tend to support, and to analyze whether their support for referendums is generic or policy-specific. Our qualitative content analysis draws on the election manifestos used by 38 populist parties in 21 European democracies in national elections taking place between 2016 and 2023.

Introduction

Most of the literature on populism claims that there is a strong preference for referendums among populist actors. Even if, as appears to be the case in this special issue, there are debates concerning the exact definition of populism (see the article by Borriello, Pranchère and Vandamme), most scholars would consider populism to be based upon a conception of politics in which people-centrism and anti-oligarchism are core components. According to many authors working on populist parties, the conception of politics that populism promotes translates into strong support for referendums. For Mudde (Citation2007, p. 152), ‘virtually all populist radical right parties call for its (referendum’s) introduction or increased use’. As a more recent study explains, ‘Referendums fit with each of the (three) key aspects of populism: they are people-centered, reduce the power of the elite and are a means to keep the corrupt elite in check (at least to some extent)’ (Jacobs et al., Citation2018, p. 520).

Yet, several recent studies show that the support for referendums proclaimed by populist parties is not as straightforward as many have assumed. On the one hand, in comparing the election manifestos of populist and non-populist parties, Gherghina and Pilet (Citation2021) observed that populist parties in several European countries were not making more references to referendums than non-populist parties. On the other hand, once they gain power, populist elites make little use of referendums in defining new policies (Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2020). These elements already add nuance to the linkages that are often assumed between populist parties and referendums. In this article, we propose to dig deeper into this question by analyzing how these parties talk about referendums in their election manifestos. Manifesto documents are a standard accessory of elections in democratic countries used by political parties to present summaries of their policies to the voters, to communicate with interest groups, and to use in the post-electoral government formation process (Däubler, Citation2011). They are rich sources of information about the positions that parties want to communicate to voters, but also to other parties with whom they might seek to form coalitions after elections. In this paper, we analyze how 38 populist parties across 21 European democracies talked about referendums in recent elections between 2016 and 2023.

We specifically examine two elements. First, we study what kind of referendum populist parties tend to support (e.g. citizen-initiated and mandatory ones, as opposed to elite-initiated ones). Second, we examine whether their support for referendums is generic, in that it does not specify which kind of policy issues should be put to popular vote, or whether it is limited to specific policy domains. By doing so, we aim to shed light on what populists promote about referendums. This will clarify if they see the referendums as instruments that match their vision of a more people-centered democratic system, or if their support for referendums is conditioned by other considerations related to vote or policy-seeking strategies, or to the ‘thick ideology’ to which their populist views are attached. If the former applies, then we might expect populist parties to make claims in their manifestos about the general use of referendums in all policy domains. If the conditional support applies, then we might expect populist parties to associate referendums to specific policies but not to others.

Our article is structured into four sections. The first section will elaborate on the extant literature on how we might expect populist parties to talk about referendums. The second section of the paper will present our method and data. Next are the main findings, before the final section discusses the main implications of our results and suggests further directions for research.

Populist parties and referendums

Even if the model of democracy promoted by populist ideology remain debated, there is general agreement that it implies increasing the direct role that citizens can play in shaping policy decisions, whether against or in collaboration with elected representatives. For Meny and Surel (Citation2002b, p. 9), ‘populist movements speak and behave as if democracy meant the power of the people and only the power of the people’. Canovan (Citation1999, p. 10) connects populism to the redemptive vision of democracy that its proponents defend, and for which ‘The people are the only source of legitimate authority, and salvation is promised as and when they take charge of their own lives’. Therefore, democracy should allow ‘direct, unmediated expression of the people’s will’ (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 13). This logic is also found in the ‘ideational approach of populism’ according to which one of its core traits is its people-centric nature. Populism, in this approach, promotes a model of democracy in which the people should lie at the core of democracy and ‘politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the People’ (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 543).

Several authors have derived from these elements the view that populist parties, as the main vehicles of populism as an ideology, are likely to push for a model of government in which referendums will be a central instrument as the ‘closest institutional arrangement in which an unmediated people’s will is expressed’ (Caramani, Citation2017, p. 62) as well as an efficient way of keeping the elite under scrutiny (Abrial et al., Citation2022). For a long time, most scholars followed Cas Mudde’s observation that ‘virtually all populist radical right parties call for its [referendum’s] introduction or increased use’ (Mudde, Citation2007, p. 152). However, recent studies of populist parties have examined whether they actually push for a greater use of referendums in their communication and actions when in parliament or in government. The link between populist parties and support for referendums is not always straightforward. In their in-depth analysis of references made to referendums across 27 European countries in over 800 electoral manifestos put out by populist and non-populist parties, Gherghina and Pilet (Citation2021) found that populist parties were not pushing more for a greater use of referendums than non-populist parties. These authors even observed that about half of the election manifestos issued by populist parties were silent about direct democracy. In a similar vein, looking at the capacity of populist parties to push to organise more referendums upon entering government, previous studies have found that populist parties have not been initiating more referendums than non-populist parties (Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2020). It therefore seems that populist parties voice this policy much more when they are in the opposition than they do in government. A series of referendums have been called by some populist parties while in government (Fidesz in Hungary, M5S in Italy, or SVP in Switzerland), but more systematic accounts have tended to provide rather mixed evidence about the extent to which populist parties call referendums once in power. Referendums do not appear to be at the core of their action, especially as they become more accustomed to power within representative institutions (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Citation2015; Albertazzi & Mueller, Citation2013; Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2020; Pappas, Citation2019). It has also been stressed that populist parties dominated by strong authoritarian leaders might push less for referendums, and could be reluctant to call referendums that may constrain the role of that strong leader (Mudde, Citation2004; Taggart, Citation2000). In this special issue, this logic is clearly confirmed by Angelucci, Vittori, and Rojon in their analyses of referendums held across 29 European countries in the past 20 years.

These elements tend to indicate that the relationship of populist parties with referendums is not as straightforward as may have been theoretically expected. Those studies highlight the need to explore in more detail why populist parties call for a greater use of referendums in their election manifestos. The general explanation provided for these parties’ support for referendums is linked to their vision of democracy. Referendums can be a relevant instrument in that regard (Mudde, Citation2004), but there are also instances in which the role of referendums is unclear, e.g. when populism is attached to a vision of democracy in which strong leaders are empowered (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012). However, strong leaders can also use referendums in a plebiscitarian way to create a direct link with voters and bypass the mediating role of political parties or social movements (Topaloff, Citation2017).

Ideology is not the sole motivation behind populist parties’ support for the use of referendums. Populists, like any other parties, are both vote and policy-seekers. Their position on referendums as expressed in their election manifesto is conditioned by how they evaluate its impact on their capacity to attract voters and to push their policies. In terms of vote-seeking motivations, calling for a greater use of referendums could help populist parties to attract citizens who are more dissatisfied with the way democracy is working in their country. Those citizens are indeed more likely to be in favour of referendums (Schuck & de Vreese, Citation2015). Nevertheless, the support for referendums is not a major driver of the vote for populist parties (Rooduijn, Citation2018). An explanation for this might be that the topic is not very salient for many voters. In context in which the use of referendums is more contentious – such as in the UK after Brexit or in Spain after the referendum on the independence of Catalonia – supporting referendums might be regarded as a risky electoral strategy. When it comes to the policy-seeking motivations of populist parties, the core question is whether they can hope to push some of their policy priorities more easily via a direct vote than via representative institutions. This might be the case when populist parties are in opposition, and in relation to issues that are of high interest among voters. By contrast, when populist parties are in power or on issue positions that they believe are not widely supported within the population, they might be less willing to call for a greater use of referendums.

All these elements call into question the theory that populist parties always support referendums, are precise on how they should be implemented, and call for its use on a wide range of policy issues and under any circumstances. This doubt is in line with an earlier observation that some populist parties stay quite silent about referendums in their election manifestos (Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021). We therefore propose in this article to dig deeper into the actual support for referendums by populist parties by examining the election manifestos of populist parties that mention referendums in order to gain a better understanding of how they talk precisely about referendums.

Hypotheses

Building on the literature that explains that populist parties defend referendums as a core characteristic of their model of democracy (Caramani, Citation2017; Meny & Surel, Citation2002a), we can expect that populist parties will primarily develop proposals in their party manifestos calling for a central role for referendums in the democratic system of the country. Such claims will not target specific policies, nor will specific details about the rules and regulations of referendums be given; instead, they will mostly be general claims in favour of referendums.

Yet, there are a wide variety of institutional arrangements for referendums across democracies (Morel & Qvortrup, Citation2018). One of the key distinctions in that respect is how the referendum is initiated. There are three main types of referendums: (1) referendums initiated by citizens (based on collecting a certain number of signatures), (2) referendums called by representative authorities (parliament, government, or president), and (3) referendums that are automatically initiated based upon constitutional provisions (like referendums on international treaties in Ireland and Denmark). Considering populism as a people-centric and anti-oligarchic conception of democracy, we expect populist parties to be more in favour of citizen-initiated referendums and mandatory referendums, and less supportive of referendums that are controlled by elected politicians. Moreover, we might expect populist parties to call in their election manifestos to facilitate citizens’ initiatives, for example by lowering the threshold number of signatures required to call a referendum.

Another important characteristic of referendums is the policy domain they can cover. Here, the debates relate to how important the populist ideology is to the parties that promote it. Within the ideational approach, populism is general conceived as a thin-centered ideology associated with a host ideology (with, for instance, radical right and radical left populist parties) (Kaltwasser et al., Citation2017). The question that remains is whether populism dominates, or is dominated by, the host ideology. Regarding how populist parties talk about referendums, the answer to the question could have direct implications. If populism dominates, then populist parties should promote a greater use of referendums on a wide range of policy issues, as much as possible. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Populist parties primarily make general claims about a greater use of referendums without references to specific rules, regulations or even policies.

H2: When calling for a greater use of referendums, populist parties are especially in favor of citizen-initiated (H2a) and mandatory referendums (H2b).

H3: Populist parties call for a greater use of referendums in a wide range of policy domains.

H4: Radical right populist parties will particularly call for a greater use of referendums on issues related to immigration (H4a) and European integration (H4b).

H5: Radical left populist parties will particularly call for a greater use of referendums on issues related to socio-economic policies (H5a) and the extension of minority rights (H5b).

H6: Opposition populist parties are more likely to call for a greater use of referendums on many policy issues compared to those in government.

Method and data

To test these hypotheses, we collected the electoral manifestos used by populist parties in the most recent legislative elections at the national level in 21 European countries. The case selection involved two phases. In the first phase we selected the countries. These were drawn from the same continent to ensure homogeneity in terms of party roles in the political system and a relatively common conceptualisation of populism, which is different from that encountered elsewhere (Gherghina et al., Citation2013; Heinisch et al., Citation2021; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012). The countries selected are Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. They were selected to maximise variation with respect to the topic of the study: populist parties and their attitudes towards referendums. Our sample includes countries in which direct democracy is not used at all, or is very rarely used (Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands) and others where it is a recurrent instrument of policy-making (Ireland or Italy). Some countries have strong populist parties (Netherlands, France), which are even sometimes in power (Italy, Hungary, Spain, Bulgaria). In others, populist parties remain constantly in opposition (Belgium, Portugal) or are very weak electorally (Luxembourg, Ireland, the UK). All these elements allow an examination of how the context in which populist parties are active (their participation in power) might affect the way they talk about referendums.

In the second phase, we selected from these countries those political parties that are labelled as populists in the PopuList project (Rooduijn et al., Citation2019). The parties must either have parliamentary presence, or have gained more than 1% of a popular vote. Our analysis covers 38 populist parties, which are listed in Appendix 1. There are three exceptions in our chosen cases compared to what PopuList provides for these 15 countries. These exceptions are based on assessments drawn from the existing literature: we do not consider Forza Italia as a populist party (Gattinara & Froio, Citation2021), and we label USR-PLUS as populist in line with previous studies about Romanian politics (Dragoman, Citation2021). We also add the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) to the list of populists as a newly emerged political party which contested elections for the first time in 2020 (Gherghina & Mișcoiu, Citation2022; Soare & Tufiș, Citation2021).

The analysis covers the electoral manifestos used by these parties in the most recent national elections (those held between 2017 and 2023).Footnote1 To identify how parties speak about referendums, we conducted a qualitative content analysis using a basic dictionary including four keywords in the national language of the manifesto: referendum, direct democracy, plebiscite, popular (vote), and (citizen) initiative. The excerpts from the manifestos were coded using the procedures of deductive thematic analysis (Kiger & Varpio, Citation2020) in which the themes correspond to elements included in the hypotheses: citizen-initiated referendums, mandatory or constitutionally provided referendums, and policy domains (immigration policy, European integration, socioeconomic policies, and minority rights). The sentence was the unit of analysis and sentences were grouped into these themes according to their meaning. There was a residual thematic category that we discuss at the end of the following section. The coding was directly performed by the authors of the study. In relation to countries for which the authors were not masters of the national language in which the manifestos were written, the coding was done in collaboration with national experts from the country by combining the excerpts in the original language and their translation into English. We used double-blind coding for many countries, with more than two coders per country.

Empirical analysis

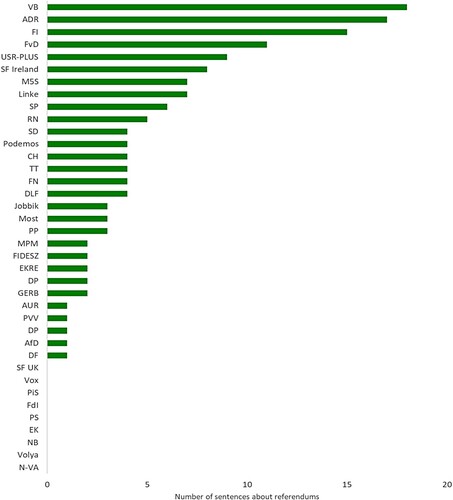

summarises the frequency of sentences about referendums in the manifestos. A total of nine populist political parties did not refer to referendums in their manifestos at all: N-VA (Belgium), Volya (Bulgaria), NB (Denmark), EK (Estonia), PS (Finland), FdI (Italy), PiS (Poland), Vox (Spain) and Sinn Fein UK (United Kingdom). In the case of Sinn Fein, it is not surprising that their manifesto for the UK general election does not mention a referendum. However, the party did develop a different manifesto for the elections in Ireland in which several references to referendums are made (see the following section). Four other populist parties – AfD in Germany, DP in Lithuania, PVV in the Netherlands, and AUR in Romania – have only one sentence in their manifestos about referendums. More than half of the remaining parties have less than five sentences about referendums. Several populist parties refer extensively to referendums: Forum for Democracy (FvD) in the Netherlands, France Insoumise (FI), Alternative Democratic Reform Party (ADR) in Luxembourg, and Vlaams Belang (VB) in Belgium. This overview indicates a great variation between the populist political parties in Europe regarding the space provided in their manifestos to referendums on the one hand, and on the other hand, that most populist parties make quite few references to referendums.

The first hypothesis we test here is that populist parties see referendums as a core component of the democratic model they propose. We expect that they mention referendums in general terms, call for greater use, and insist on making them a central instrument of policy-making. However, we do not expect them to go into much detail, such as specifying rules to organise them or emphasising particular policies that should be subject to popular vote. The frequency of statements shown in provides a preliminary indication that it is unlikely that many parties will be very specific about referendums, as there are too few statements in the manifestos of many populist parties to allow them to give many details. The content analysis illustrates that this hypothesis finds empirical support to a large extent.

The election manifestos of 15 populist parties from Belgium, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, and Romania refer to the need to implement more referendums in general (see ). These parties make a general point regarding the implementation of more referendums, but do not comment on how these should be organised, and do not specify clear policy domains in which the citizens should have more power, instead making general statements such as: ‘As we firmly believe that the best governance can only be democratic governance, any initiative that enhances transparency, promotes accountability and can serve as an example in our relations with citizens should be supported’ (Fidesz, 2018). In Luxembourg, the populist party makes a similar argument: ‘Through the direct route of the referendum, the ADR ensures that the voter participates in important national decisions’ (ADR, 2018).

Table 1. Summary of empirical support for each hypothesis per populist party.

We observe the same logic from populist parties like USR-PLUS in Romania, DLF and National Rally (RN) in France, Order and Justice (TT) in Lithuania, and the Popular Party (PP) in Belgium. These parties all call for change to national legislation to allow for more types of referendums or to change the requested steps to initiate the referendum process. They do not explicitly mention their preferred types of referendums, instead making general statements about the need to use more referendums per year. For example, one proposes to: ‘Hold a referendum to revise the constitution and make any future revision of the constitution conditional on a referendum’ (RN, 2017), and another that:

‘Citizens must return to the centre of the decision-making process through the establishment of the referendum at all levels of power. Citizens must be able to be consulted on political and ethical questions but also on public investments. The results of the referendum must be binding on the authorities’ (PP, 2019).

Following a similar path regarding the use and/or importance of referendums, the Estonian Conservative People’s Party and Sweden Democrats (SD) each promote in their party manifestos the idea that the referendums should be respected as mentioned in the law, and that this direct procedure should strengthen direct democracy in the country: ‘Referendums and fair elections strengthen democracy, the judiciary and the justice system and limiting the arbitrary power of bailiffs will protect the Estonian people’ (EKRE, 2019). SD also adds a component related to the European Union to the ideas expressed above, proposing to: ‘Strengthen Sweden's negotiating position in the EU through a referendum instrument that gives the Swedish people the opportunity to take a position on crucial choices in the EU’ (SD, 2022).

We also identified several populist parties that supported the idea that the results of previous referendums should be respected and implemented in the legislation from their respective countries. For example, USR-PLUS in Romania argues that: ‘Despite the consultative nature of that referendum (number of MPs), the Constitutional Court ruled that the result of the popular vote cannot be ignored, in the sense that Parliament must implement it sooner or later, and until then it is bound not to adopt legislation to the contrary’ (USR-PLUS 2020). In a neighbouring country, Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) claims that ‘In this programme we once again state our firm belief that the results of the Referendum, held simultaneously with the Presidential elections of late 2016, should be translated into legislation and subsequent governance actions’ (GERB, 2017). Summing up our findings regarding H1, we see that populist parties most often make general claims about referendums and the intention to make their use more frequent. But, there are few references to specific rules for implementing the instruments. For example, provisions like a threshold of participation or how referendum questions should be formulated are never specified.

Our second line of expectation was that populist parties would be less enthusiastic about referendums that are called on the initiative of representative institutions, instead preferring to support citizen-initiated referendums (H2a) or referendums that are mandatory in the Constitution (H2b). reports on the parties for which we found electoral manifesto sentences confirming our second set of hypotheses. A first observation from our analysis of the party manifestos is that very few populist parties refer both to citizen-initiated referendums and mandatory referendums: Sinn Fein in Ireland, ADR in Luxembourg, Five Star Movement (M5S) in Italy, and Chega in Portugal. Sinn Fein considers the mandatory referendum as a way through which people can set the policy-agenda. Chega, in Portugal, calls for a general revision of the constitution, pointing out that the current document was written while the country was under military control:

Thus, bearing in mind that the current Constitution was the product of a military imposition (the so-called MFA – Parties pact) which preceded the 1975 elections for the Constituent Assembly and that, therefore, this Constitution was not a genuine product of the sovereign will of the People, we demand a referendum on the 1975 Constitution (Chega, 2019).

These populist parties call for regulations that would allow citizens to initiate new referendums when enough signatures are collected. The TT 2016, DLF 2017, RN 2017, ADR 2018, and USR-PLUS 2020 party manifestos all explicitly refer to the need to reduce the number of signatures required to trigger a referendum on a certain topic. Some of them propose a certain number of signatures which should be necessary to initiate the process, which is relative to the voting age population in the country: ‘We will reduce the number of initiators needed to call a referendum to 100,000’ (TT, 2016); ‘Create a popular initiative referendum when a project is supported by 500,000 registered voters’ (DLF, 2017 and RN, 2017); and ‘In order to be able to hold a referendum through the people's initiative, the necessary number of voters who demand it must be reduced to 5% – currently there would be around 12,500 people’ (ADR, 2018). In addition to stating a specific number of signatures, there are references to the unjustified territorial distribution of signatures required to initiate a referendum (USR PLUS, 2020). In the latter case, the initiative procedure refers exclusively to referendums on constitutional matters since those are the only ones for which citizens’ initiatives are considered in the country.

The empirical support for H1b is more limited. Some parties propose to modify the constitution of their country in order to make referendums on some issues mandatory, but only seven parties are in this category (FI and RN in France, Sinn Fein Ireland, Lega and M5S in Italy, ADR in Luxembourg, and Chega in Portugal). The references to constitutionally mandatory referendums refer mainly to future revisions of the constitution and to international and European integration treaties. For example, RN in France explains that once in power it will ‘hold a referendum to revise the constitution and make any future revision of the constitution conditional on a referendum’ (RN, 2017). Similar ideas are available in the Sinn Fein manifesto in Ireland: ‘We propose to hold a referendum on enshrining neutrality into Bunreacht nah Éireann. The referendum would decide whether to amend the constitution to ensure Ireland will not and cannot aid foreign powers in any way in preparation for a war’ (Sinn Fein, 2020).

We now turn to hypothesis 3, that refers to the policy domains. The empirical evidence for our theoretical expectation that populists will push for referendums in wide policy domains is very weak. On the one hand, most populist parties make general references to referendums, proposing to use them on a regular basis to associate citizens with decision-making. For that to happen, referendums would need to be held on a wide range of topics, yet there is only indirect evidence in favour of H3, while direct evidence is scarce. We have not found explicit references to a wide range of policy domains that could be submitted to referendums in the manifestos of the populist parties. Populist parties tend to speak in broad terms about the use of referendums rather than specifying the policy domains in which popular votes should be called. However, there are also several instances in which populist parties explicitly mention specific policy domains.

We mostly observe references to economic decisions and to decisions related to national sovereignty (i.e. European integration, international treaties). Explicit references to other policy domains are fairly rare. For example, Moviment Partijotti Maltin (MPM) in Malta make explicit reference to hunting policies, an area in which they even organised a referendum: ‘Hunting in our country is a tradition that was confirmed in a referendum by the Maltese people and therefore we will insist that this tradition be respected but it will be a regulated hunt in order to reduce abuses’ (MPM, 2017). A few populist parties also propose to organise referendums regarding institutional arrangements, particularly to remove or re-elect certain members of government or parliament. For example, FdI (2022) claims that: ‘We know that difficult years lie ahead and that only a government legitimised by the popular vote, together with a new national cohesion, can lead Italy out of the crisis into which it has been dragged by short-sighted and irresponsible politics’, while FI (2017) intends to: ‘Create a right to remove an elected official during his or her term of office, by referendum, upon request of a portion of the electorate’.

We do not find much empirical support for the remaining hypotheses that distinguish between types of populist parties and the policies they would prefer, except for H4b. First, there is no evidence to support H4a. The immigration theme is not mentioned in any of the party manifestos in relation to referendums. Instead, the manifestos refer to immigration in relation to the country’s security, economy, and migration policies. Most of the populist parties point out that their countries need effective laws to regulate the migration of illegal migrants: ‘Every state has to have an immigration system with well-functioning rules and regulation that everyone understands and that serves the interest of the people of the country’ (SF Ireland, 2020). We can also see that these populist parties propose to manage immigration based on their country’s economic capacities; for example, ‘Immigration must be controlled at a level consistent with France's capacity to receive immigrants’ (DLF, 2017); and ‘Immigration will be dealt with in accordance with the needs of the Spanish economy and the immigrant's capacity for integration’ (Vox, 2019). Even though there is no relation between immigration and referendums, we could observe calls by these parties for migration policies through which the country can keep its level of security, such as: ‘To this end, the N-VA wants a regulated, organised and limited migration policy. We go full steam ahead to reform European directives and regulations that make a strict migration policy impossible’ (N-VA, 2019); ‘Our laws and our judges are regularly condemned by the European authorities, who dictate our social choices or our immigration policy’ (DLF, 2017); and ‘Migration must take place in conditions of security for people, and the State must articulate mechanisms to guarantee human rights, especially the right to life’ (Podemos, 2019).

The references to referendums in relation to European integration are more frequent. Overall, we observe explicit references by five radical right parties (ADR, FvD, MPM, RN, and VB) in their manifestos to referendums on European integration. In its 2017 manifesto, RN in France speaks about a referendum on sovereignty issues and EU membership: ‘To regain our freedom and the control of our destiny by restoring to the French people their sovereignty (…) followed by a referendum on our membership in the European Union’. VB considers that the citizens of a country should be able to decide on their own country’s future, and that no political institution should take a decision without consulting them:

Vlaams Belang recognizes the self-determination of the European peoples. If a people within Europe speaks democratically for independence (for example by referendum), or vice versa for attachment to another state, this must be recognized as such by all European institutions (VB, 2019).

Furthermore, we demand a mandatory referendum for changes to the European Treaty, for the admission of new members to the European Union, for the transfer of greater sovereignty rights to the European Union and for important changes to the Luxembourg constitution. Even for possible inclusion of new countries in the European Union, a national referendum must be voted on (ADR, 2018).

Continuing with radical left populist parties, our fifth hypotheses was that such parties will also connect claims in favour of referendums to the policy domains at the very core of their ideology: economic redistribution (H5a) and minority rights (H5b). However, support for those two hypotheses proved to be very thin. The only reference to a referendum on economic issues could be found in the manifesto of a radical right populist party, Chega in Portugal: ‘Until a referendum is held on the Constitution, we propose an amendment to its economic part, the part that establishes the progressive nature of the tax’ (Chega, 2019).

Thus, we have seen that the populist parties from the 21 countries included in the study refer to referendums in various different ways. In terms of the differences between the types of referendums promoted by populist parties in government and opposition (H6) we can conclude that no party in opposition calls for a greater use of referendums on many policy issues. These parties tend to speak about referendums in general terms, like the parties in government, and do not make any specific connections with policies that they consider important or of high interest to citizens.

Discussion and conclusion

The goal of this paper was to examine how populist parties talk about referendums. Existing research has widely elaborated on the close connection between populism and direct democracy (Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021; Heinisch et al., Citation2021; Van Crombrugge, Citation2020). Referendums are one of the main instruments that can reflect the people-centric nature of populism. Yet, the precise ways in which populist parties translate this idea into actual statements presented to the electorate in elections has never been examined closely before.

We used the recent electoral manifestos of 38 populist parties across 21 European countries to test six hypotheses (see ). The first hypothesis was that populist parties would primarily include general claims about referendums, their importance in democracies, and the need to organise more of them, but without mentioning specific rules as how to organise them, or specific policies that should be put to the people’s vote. There is strong evidence confirming that many populist parties refer to referendums broadly, as a signal of what kind of democracy they want, to give a direct voice to the people in the decision-making process.

Table 2. A summary of the empirical evidence for the hypotheses.

The second hypothesis related to the types of referendum that populist parties seem to promote. Our expectations were that they would primarily support citizen-initiated referendums and constitutionally mandatory referendums. Only the first expectation finds strong support. We observed clear references in the manifestos of populist parties across Europe to referendums that are to be initiated when the signatures of many citizens have been collected. This confirms that the comprehension of direct democracy by populist parties is a model of policy-making by the people, rather than as a plebiscitary instrument controlled by elected politicians. Regarding constitutionally mandatory referendums, empirical support has been less strong; references could be found in the manifestos of a few populist parties (see ).

The next three sets of hypotheses concerned the policy domains that populist parties link to referendums. We did not observe calls by populist parties for referendums on a wide range of issues; in fact, the vast majority of references to direct democracy in populist parties’ manifestos are policy blind. Referendums are discussed as an instrument of democratic renewal, but without details on which policies should be submitted directly to the people. We have also not observed populist parties making explicit pledges about referendums to be held on issues central to their ideology, nor have we observed proposals by radical right populist parties to hold referendums on immigration, nor claims by radical left populist parties to put decisions on economic redistribution or on minority rights directly to voters. The only exception relates to European integration; in this case, several populist parties make explicit in their election manifestos that they want to organise referendums on European integration, either to ratify any new European treaties or even to ask citizens whether they would like to leave the European Union.

Lastly, we find no difference between populist parties in government and in opposition (H6). The manifestos present similar ideas regarding referendums as a tool to strengthen democracy, but no opposition party claims that it wants to use referendums to address multiple policy issues. Those elements seem to indicate that calling for referendums would be associated with the populist nature of those parties (their thin-centered ideological component). Referendums are thus not conceived as a policy-seeking instrument that is just to be used to more easily pass specific pieces of legislation related to the host ideology (either far right or far left) of the populist parties. This appeal for referendums as a democratic principle holds even when populist parties come to power – but we should bear in mind that this paper has studied the discourses of populist parties in their manifestos, not their actual actions in power.

All these elements lead to a twofold conclusion. First, most populist parties call for a greater use of referendums, as has been shown in earlier research (Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021). These references to referendums are mainly general claims about the transformation of democracy, from a predominantly representative model to a model that combines representative institutions with direct democracy. According to populist parties, the latter should be a central component of the political system they promote. Yet, as our second main conclusion indicates, populist parties rarely provide details about what types of referendums they wish to implement, how they would like them to be organised, or on what topics. They usually do not mention the specific rules and regulations nor the policy domains that they believe should be decided via referendums. Populists appear to be content with the existing trend around the world in which referendums are organised on an increasing number of topics (Qvortrup, Citation2018; Silagadze & Gherghina, Citation2020). They have limited preferences regarding specific policy issues. The only two elements that stand out in several populist parties’ manifestos is their support for citizen-initiated referendums and the idea that European integration should more often be submitted to popular vote. In other words, our study confirms that when populist parties talk about direct democracy, they do so more in relation to the model of democracy they promote rather than specific plans or detailed ideas.

Further research can build on these findings and may go in at least three directions. One possible avenue could be to seek to identify the reasons behind this general approach towards referendums. Some of the results provided in our exploratory study could form the basis for interviews with the political elites involved in drafting the manifestos. A second direction could be a comparative analysis between manifestos drafted for different levels of electoral competition. For example, in some countries political parties use manifestos in national, regional and/or local elections. A comparison of these documents could reveal whether political parties use references to referendums depending on their target audience. A third potential direction for further research could be to compare the references to referendums in populist manifestos to the popular demand for direct democracy. This approach could help to establish whether populists adjust to or shape public opinion with respect to the use of referendums.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sergiu Gherghina

Sergiu Gherghina is an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at University of Glasgow. His research interests lie in party politics, democratization, political participation and direct democracy.

Jean-Benoit Pilet

Jean-Benoit Pilet is a Professor of Political Science at Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. He is specialized in elections, electoral systems, political parties, Belgian politics and democratic innovations.

Bettina Mitru

Bettina Mitru is a PhD Candidate in Internaitonal Studies at Babes-Bolyai University Cluj and in Political Science at Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Her research interests include party politics, democratic innovations and political participation.

Notes

1 The full list of party manifestos we coded is provided in Appendix 1. The length of the manifestos (in number of words) is also specified. There is significant variation in length, which indicates that not all parties put the same effort into preparing their manifestos and in using them as an accurate reflection of all their policy priorities.

References

- Abrial, S., Alexandre, C., Bedock, C., Gonthier, F., & Guerra, T. (2022). Control or participate? The Yellow Vests’ democratic aspirations through mixed methods analysis. French Politics, 20(3), 479–503. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-022-00185-x

- Akkerman, T., de Lange, S. L., & Rooduijn, M. (2016). Radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: Into the mainstream? Routledge.

- Albertazzi, D., & McDonnell, D. (2015). Populists in power. Routledge.

- Albertazzi, D., & Mueller, S. (2013). Populism and liberal democracy: populists in government in Austria, Italy, Poland and Switzerland. Government and Opposition, 48(3), 343–371. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2013.12

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Däubler, T. (2011). The preparation and use of election manifestos: Learning from the Irish case. Irish Political Studies, 27(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2012.636183

- Dragoman, D. (2021). “Save Romania” union and the persistent populism in Romania. Problems of Post-Communism, 68(4), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2020.1781540

- Gattinara, P. C., & Froio, C. (2021). Italy: The Italian mainstream right and its allies. 1994–2018. In T. Bale & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), Riding the populist wave: Europe’s mainstream right in Crisi (pp. 170–192). Cambridge University Press.

- Gherghina, S., & Mișcoiu, S. (2022). Faith in a new party: The involvement of the Romanian Orthodox Church in the 2020 election campaign. Politics, Religion & Ideology, (online first).

- Gherghina, S., Mișcoiu, S., & Soare, S. (Eds.). (2013). Contemporary populism: A controversial concept and its diverse forms. Cambridge Publishing Scholars.

- Gherghina, S., & Pilet, J.-B. (2021). Do populist parties support referendums? A comparative analysis of election manifestos in Europe. Electoral Studies, 74, 102419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102419

- Gherghina, S., & Silagadze, N. (2020). Populists and referendums in Europe: Dispelling the myth. The Political Quarterly, 91(4), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12934

- Heinisch, R., Holtz-Bacha, C., & Mazzoleni, O. (2021). Political populism: Handbook of concepts, questions, strategies (2nd ed.). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Jacobs, K., Akkerman, A., & Zaslove, A. (2018). The voice of populist people? Referendum preferences, practices and populist attitudes. Acta Politica, 53(4), 517–541. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0105-1

- Kaltwasser, C. R., Taggart, P., Espejo, P., & Ochoa Ostiguy, P. (Eds). (2017). The Oxford handbook of populism. Oxford University Press.

- Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Meny, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002a). Democracies and populist challenge. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meny, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002b). The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Yves Mény & Yves Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 1–21). Palgrave.

- Morel, L., & Qvortrup, M. (2018). The Routledge handbook to referendums and direct democracy. Routledge.

- Mouffe, C. (2018). For a left populism. Verso Books.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas. Threat or corrective for democracy? Cambridge University Press.

- Pappas, T. (2019). Populists in power. Journal of Democracy, 30(2), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0026

- Qvortrup, M. (2018). Referendums around the world: With a foreword by Sir David Butler. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000145

- Rooduijn, M., van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., de Lange, S. L., Halikiopoulou, D., Lewis, P. G., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2019). The PopuList: An overview of populist, far right, far left and Eurosceptic parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org

- Schuck, A. R. T., & de Vreese, C. H. (2015). Public support for referendums in Europe: A cross-national comparison in 21 countries. Electoral Studies, 38(1), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.02.012

- Silagadze, N., & Gherghina, S. (2020). Bringing the policy in: A new typology of national referendums. European Political Science, 19(3), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-019-00230-4

- Soare, S., & Tufiș, C. D. (2021). No populism’s land? Religion and gender in Romanian politics. Identities, (online first).

- Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Open University Press.

- Topaloff, L. (2017). The rise of referendums: Elite strategy or populist weapon? Journal of Democracy, 28(3), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0051

- Van Crombrugge, R. (2020). Are referendums necessarily populist? Countering the populist interpretation of referendums through institutional design. Representation, (online first).