ABSTRACT

Theoretical works suggest that populist attitudes are associated with demands for direct democracy in the form of referendums. However, it remains unclear how populist attitudes relate to other direct-democratic instruments such as citizens’ initiatives. We therefore examine whether populist attitudes affect the attitudes toward the Citizens’ Agenda Initiative (CI) in Finland with the help of the national election study from 2019 (n = 1598). We study (1) whether populist attitudes are associated with positive attitudes towards the CI (2) whether populist attitudes increase the use of the CI, and (3) the interplay between anti-elitism, anti-immigration, and anti-pluralism as driving forces behind attitudes towards and using the CI. The results suggest that anti-elitism has a negative link to satisfaction with the CI, and anti-pluralism is associated with lower likelihood of using the CI. Hence there is little to suggest that populist attitudes are strong drivers of involvement in this kind of direct-democratic participation.

Introduction

Several studies have examined the association between populist attitudes and support for making mechanisms of direct democracy (Bengtsson & Mattila, Citation2009; Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021; Manucci & Amsler, Citation2018; Mohrenberg et al., Citation2021; Trüdinger & Bächtiger, Citation2023). While several studies indicate that holding populist attitudes is connected to support for making political decisions through referendums, these results have been criticised for being (at least) borderline tautological since measures of populist attitudes frequently include indicators that probe support for referendums (Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021). Furthermore, it is important to consider the interplay between different dimensions of populist attitudes (Christensen & Saikkonen, Citation2022; Neuner & Wratil, Citation2022; Silva et al., Citation2023). It may be that certain mixes of populist ideological aspects are mutually reinforcing in creating expressions of populist attitudes (Neuner & Wratil, Citation2022). Finally, even if people with higher populist attitudes are more likely to support direct democracy, this does not necessarily entail that they also become active participants (Trüdinger & Bächtiger, Citation2023). While studies show that ideals of political decision-making may affect involvement (Bengtsson & Christensen, Citation2016; Gherghina & Geissel, Citation2017), it is not necessarily the case for populist attitudes, which is why it is important to consider active participation in direct democracy in addition to general support for direct democratic instruments.

In connection to this, it is important to note that direct democratic instruments cover a variety of institutions and practices (Altman, Citation2011; Qvortrup, Citation2013; Setälä & Schiller, Citation2012). Nevertheless, most studies on populism and direct democracy confine themselves to examining the link to referendums. However, direct democratic instruments may have very different functions in democratic systems (Smith, Citation1976), and there are a variety of ways of combining direct democratic instruments such as initiatives and referendums with each other and with representative politics (e.g. Jäske & Setälä, Citation2020). Accordingly, it has been argued that there cannot be ‘a general theory of referendums’ (Smith, Citation1976), and that the whole concept of ‘direct democracy’ may be quite misleading (el-Wakil & McKay, Citation2020). It is therefore valuable to examine whether populist attitudes are also linked to other direct democratic mechanisms than referendums.

We therefore explore the associations between populist attitudes and use of and attitudes to the Finnish Citizens’ Initiative (CI), which constitutes a direct-democratic instrument that in several regards differ from referendums. The Finnish CI, introduced in 2012, is an agenda or indirect initiative, which makes it possible for at least 50.000 citizens to make a legislative proposal to parliament (Schiller & Setälä, Citation2012). While this instrument does not make citizens the final decision-makers, it has become a popular element of Finnish democracy that engages wide segments of the population (Christensen et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Huttunen & Christensen, Citation2020). The Finnish CI therefore provides an excellent possibility for whether populist attitudes are also connected to other direct-democratic instruments.

Our data come from the Finnish National Election Survey conducted following the Finnish elections for parliament in April 2019. This survey provides adequate measures for both measuring relevant aspects of populist attitudes as well as involvement in using the CI and attitudes towards the CI. We conceive our study as exploratory in nature since we do not know whether populist attitudes as linked to the CI. We therefore do not propose any hypotheses, but we do discuss general expectations based on previous literature.

In our empirical examination, we operate with three dimensions of populist attitudes: anti-elitism, anti-pluralism, and anti-immigration. Our findings suggest that populist attitudes do not boost neither using the CI, nor satisfaction with the impact of the CI. However, people who combine anti-immigration and anti-pluralist attitudes are more likely to sign initiatives, showing that the relationship between populist attitudes and direct democracy is complex and necessitates examining the interplay between different aspects of populism.

In the following, we outline the research on populist attitudes and their implications such as attitudes to referendums as a way of making political decisions. We conclude this section by explaining why it may be worthwhile to extend this research to alternative direct-democratic instruments such as citizens’ (agenda) initiatives. Following this, we present the Finnish CI and explain why we believe that the Finnish case provides possibilities for examining use of and attitudes towards citizens’ initiatives. We then go on to present our data and variables, before moving on to the empirical analyses. We conclude with some reflection on what the results may entail for research on populist attitudes.

Populist attitudes and direct democracy

Several studies examine dimensions of populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Castanho Silva et al., Citation2020; Geurkink et al., Citation2020; Neuner & Wratil, Citation2022; Olivas Osuna & Rama, Citation2022; Rico & Anduiza, Citation2019; Schulz et al., Citation2018; Wuttke et al., Citation2020). Despite noticable differences in how populism and key dimensions are conceptualised and operationalised, a common starting point for this line of research is that it is possible to identify these populist attitudes by analysing batteries of survey questions. The empirical study of populist attitudes frequently depart from Mudde (Citation2004, p. 543) ideational definition of populism as an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people. This definition clearly entails that populism involves an anti-elitist sentiment, but also a conception of the people as a homogenous unity. According to Mudde (Citation2004), populism thus conceived has two polar-opposites: elitism and pluralism. Furthermore, it involves a Manichean outlook, meaning a dualistic world view where the world is divided into friends and foes, and where compromise is unwarranted since it distorts the ‘will of the people’ that should prevail. According to Mudde (Citation2004, p. 544), populism is a thin-centred ideology that does not possess the same intellectual refinement as traditional ideologies such as liberalism and socialism. Instead, it can be combined with a range of ‘thick’ ideological positions to appeal to different groups in society.

Based on this conceptualisation, several studies have tried to identify suitable measures of populist attitudes. Akkerman et al. (Citation2014) provide a suitable starting point to the recent debate on populist attitudes, as they depart from Mudde´s definition and develops a battery of survey statements tapping into the three dimensions: populism, elitism, and pluralism. The populist scale includes indicators with a focus on three core features of populism: sovereignty of the people, opposition to the elite, and the Manichean division between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ (Akkerman et al., Citation2014, pp. 1330–1331). Nevertheless, in their empirical work, populist attitudes are conceived as one-dimensional, while pluralism and elitism are measured with separate indexes.

Subsequent studies have identified new dimensions of populist attitudes. Consequently, there is little agreement on what components should complement the anti-elitist sentiments, how they should be measured, and their conceptual relationships (Olivas Osuna & Rama, Citation2022; Wuttke et al., Citation2020). Some studies complement anti-elitism with dimensions covering people’s sovereignty and homogenous people (Castanho Silva et al., Citation2020; Schulz et al., Citation2018). While these additions may improve construct validity, this approach also makes it necessary to make hard choices about how to adequately measure the concept (Wuttke et al., Citation2020).

A related question examines how populism as a thin ideology coalesces with thick positions such as positions concerning immigration policies or welfare issues (Christensen & Saikkonen, Citation2022; Neuner & Wratil, Citation2022; Silva et al., Citation2023). Here the emphasis is on examining the interplay between thin and thick dimensions of populist attitudes to see how different combinations can appeal to different groups in society, which can thereby help to understand the success of populist leaders or parties in particular elections. For example, Neuner and Wratil (Citation2022) show that when it comes to candidate favourability, thin components in the form of anti-elitism matter less than the thick ideological components such as an anti-immigration position. They also find that people with thin populist attitudes are no more swayed by thin populist appeals than non-populists or thick populists. These findings suggest that there is a need to examine the interplay between different dimensions of populist attitudes to understand the implications.

We here focus on the consequences of populist attitudes for the Finnish Citizens’ Initiative (CI) as an instrument of direct democracy. There are several reasons for why this is an interesting research question.

First, several studies have examined the links between populism and support for direct democracy in the form of political decision-making through referendums (Bengtsson & Mattila, Citation2009; Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021; Iakhnis et al., Citation2018; Kokkonen & Linde, Citation2023; König, Citation2022; Manucci & Amsler, Citation2018; Mohrenberg et al., Citation2021, p. 2021; Trüdinger & Bächtiger, Citation2023; Werner & Jacobs, Citation2022). Logically, this approach seems plausible since populism emphasises that political power ought to be vested in the hands of the pure people as opposed to the corrupt politicians, which is in line with the definition by Mudde (Citation2004). Hence it may seem unsurprising that studies find a positive effect of populist attitudes on support for direct democracy and especially the use of referendums (Mohrenberg et al., Citation2021; Zaslove et al., Citation2021). Werner and Jacobs (Citation2022) even find that, not only are populists more supportive of referendums, they are also more likely to support even an unfavourable outcome. On the other hand, populist leaders are not necessarily more likely to introduce direct-democratic instruments (Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2020; Welp, Citation2022), and some studies fail to establish a connection between populism and support for direct democracy (Castanho Silva et al., Citation2022; Jungkunz et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, the bulk of the evidence suggests that a linkage exists. Some even claim that the link between populist attitudes and support for referendums risk becoming tautological due to the close relationship between the empirical measures (Gherghina & Pilet, Citation2021). Hence it is unsurprising that populist attitudes predict support for the use of referendums when using abstract measures of support. It is therefore important to examine the link with the CI as an example of another type of direct democratic instrument.

Second, populist attitudes may be linked to a preference only for certain forms of direct democracy. Populism seems to be associated with plebiscitary democracy where strong leaders rely on the ‘will of the people’, for example through referendums, bypassing mediating, representative institutions such as parliaments. This seems to entail far-reaching reforms that entail dismantling representative democracy in favour of a pervasive use of referendums to make political decisions. However, direct democracy includes various instruments and practices that interact with representative politics in a different ways (Altman, Citation2011; el-Wakil & McKay, Citation2020; Qvortrup, Citation2013). For example, some direct democratic practices such as popular initiatives can be used to challenge those in power by proposing alternative policies on the political agenda. It is therefore important to examine whether other forms of empowerment will appeal to populists. There seems to be no immediate reason why a feature such as the Manichean world view or anti-pluralism should lead to a greater preference for popular initiatives which may actually enhance pluralism of public discourse. Nevertheless, it may be possible to satisfy the populist demands by introducing less far-reaching measures that still provide a role for elected representatives. There is therefore a need for more nuanced analyses of associations between populism and different forms of direct democracy.

Citizens’ initiatives form permanent avenues for participation and allow agenda setting powers, which may be an important vehicle for popular influence (Qvortrup, Citation2013). In this way, they are more in line with more participatory visions of democracy (Barber, Citation1984). In principle, citizens’ initiatives can also serve to increase the deliberative capacity of the political system by creating new spaces for discussion and debate around political issues (Schiller & Setälä, Citation2012, p. 2). In practice, the capacity of citizens’ initiatives to enhance participation and deliberation varies a great deal, which may be largely explained by the design features of initiative institutions.

Agenda initiatives are particularly ‘soft’ forms of direct democracy because they do not lead to a popular vote but rather propose issues to be dealt with by elected representatives (Altman, Citation2011; Jäske, Citation2017; Qvortrup, Citation2013). In other words, agenda initiatives make it possible for citizens to interact with their elected representatives. There are great differences between agenda initiative institutions and practices in different countries, however (Setälä & Schiller, Citation2012). At their best, agenda initiatives can enhance parliamentary deliberation and action on policy problems recognised by the civil society. When used by non-partisan actors, they can also counteract the impediments of parliamentary deliberation such as government-opposition divide. It is therefore central to examine what aspects of populism are relevant and how they are associated with different forms direct democracy such as the CI.

Third, it is important to distinguish between support for direct democracy and actual usage of these instruments, for example by voting in referendums or signing citizens’ initiatives. While studies on preferences for democratic decision-making indicate that these have implications for political behaviour as well (Bengtsson & Christensen, Citation2016; Gherghina & Geissel, Citation2017), Trüdinger and Bächtiger (Citation2023) find that populists support direct-democratic instruments but that they fail to participate when given the chance. This indicates that there may be important differences between abstract support and actual involvement when it comes to direct-democratic instruments.

For these reasons, we here examine the extent to which thick and thin populist attitudes are associated with (1) using the Finnish CI; and (2) satisfaction with the impact of the CI on Finnish democracy. Furthermore, we also examine the interplay between thick and thin populist attitudes in shaping participation and attitudes.

The connections between populist attitudes and the CI is not clear-cut. Based on the literature review, we would expect populist attitudes to have positive associations with both using the CI and satisfaction with the CI. There are, however, also reasons to believe that the connections may be more complicated. Generally speaking, agenda initiatives can be used to express and mobilise support or opposition against governmental policies. In some systems, political parties, especially those in the opposition, have played an important role in launching initiatives (Lutz, Citation2012). In this sense, we may expect populist supporters to use the CI to express their dissatisfaction with the ruling elites when their party is in opposition. However, since agenda initiatives, in particular, would need the support of a parliamentary majority to be passed, the prospects of opposition parties or their supporters to achieve their policy goals through initiatives are often rather slim in the presence of majority governments.

As is the case for voting for populist parties, the impact of populist attitudes may well differ depending on whether populist parties are in opposition or in office (Jungkunz et al., Citation2021). Populist attitudes may increase the use of agenda initiatives when populists are represented in government, as this will increase the likelihood that their initiatives are also enacted. Nevertheless, the opposite argument could also be made since there is less of a need for launching citizens’ initiatives if their demands already form part of governmental politics.

In the following, we present the case of Finland and the national Citizens’ Initiative (CI) that was introduced in 2012 and explain why we believe this provide an important case for examining the links between populist attitudes and the CI as a type of ‘soft’ direct democracy.

The Finnish Citizens’ Initiative

The Finnish Citizens’ agenda initiative allows citizens to raise issue on the parliamentary agenda by collecting 50.000 signatures in six months. The motivation for the adoption of the CI was to invigorate the Finnish democracy (Christensen et al., Citation2017). The Finnish CI was adopted in the Finnish constitution in 2012 as a part of a larger constitutional reform, which was prepared in a specific parliamentary committee including all parliamentary parties. The introduction of the CI was supported by all main political parties and there was rather little public debate on the adoption of the CI. This may be because the constitutional reform dealt with more high-profile and contested issues such as the division of powers between the president, the parliament and the government, whereas the adoption of the CI did not involve any major shifts in formal legislative powers. However, there were some disagreements within the constitutional committee on procedural details, for example, the number of signatures required for an initiative and methods used in collecting online signatures (Oikeusministeriö, Citation2010).

The political impact of the Finnish CI is strengthened by the requirement that successful initiatives that exceed the threshold of 50.000 signatures within the designated deadline need to be dealt with in the parliamentary committees like any other legislative proposals. This ensures that the initiatives cannot be easily dismissed in parliament. To facilitate launching initiatives and collecting signatures in support of an initiative, the Finnish government provided an online system kansalaisaloite.fi. This has ensured that the process is user-friendly and accessible.

Studies have found that the CI has been considered beneficial for Finnish democracy and has succeeded in mobilising large segments of the population (Christensen et al., Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2019; Huttunen & Christensen, Citation2020). This is also evident in the data used in this study (more information on this below), according to which a large majority of Finns (75%) think that the CI has improved the quality of democracy in Finland and about 49% have signed at least one initiative.

This popularity is also evident in the number of launched initiatives. Presently about 1465 initiatives have been launched at kansalaisaloite.fi. However, only 77 of these have reached the threshold of 50.000 signatures by August 2023 and 68 have been handed over to parliament. The direct legislative impact has been rather limited since only seven CIs have been accepted by the parliament, either as such or after some changes. These initiatives have concerned a variety of topics, namely same-sex rights for marriage, equal rights for maternity law, criminalisation of female genital mutilation, privatisation of water resources, free psychotherapy education, abortion law, and the conditions for wolf hunting. Moreover, several initiatives have influenced legislation indirectly and many have led to parliamentary and public debates on issues such as fur farming, euthanasia, forest management and so on (Christensen et al., Citation2016, Citation2017).

Overall, the Finnish CI has largely fulfilled the expectations regarding increased opportunities for public influence on legislation and political debate. This is significant because the Finnish CI lacks the leverage created by a possible referendum that characterises, for example, the Swiss system of popular initiatives (Lutz, Citation2012). The initiative process has also helped make the parliamentary procedures more accessible and transparent for the public at large. For example, initiators are regularly heard in parliamentary committees. What is more, these committee hearings are often open to the general public, which is otherwise a rather uncommon practice in the Finnish parliamentary system (Su Seo & Raunio, Citation2017).

Because the Finnish CI involves rather low thresholds for making an initiative and favours campaigning in social media, CIs have been typically launched by civil society associations, activists, or even individual lay citizens. Overall, party political actors have been active in launching CIs only in a handful of cases, and in some cases (e.g. euthanasia, motherhood law), the groups of initiators have included politicians and public figures representing different parts of the party political spectrum.

There have been at least two initiatives dealt with the parliament where populist politicians and party affiliated organisations have played an active role, namely the initiative against compulsory Swedish tuition at schools (2013), and the initiative for a referendum on Finland’s membership in Euro (2015). When it comes to populist topics, two anti-immigration initiatives have passed the threshold of 50.000 signatures, namely the initiative requiring the expulsion of foreigners sentenced for crimes (2014) and for sex offences (2018). This shows that the CI can serve as an instrument to further populist sentiments, even though these initiatives were subsequently rejected by the Finnish parliament.

Finland also provides an interesting case for examining the link between populist attitudes and supporting CIs since a radical right populist party The Finns Party was represented in government during the 2015–2019 term and is again following the 2023 elections. The Finns Party entered government after the 2015 parliamentary elections in a government coalition consisting of the Centre Party, led by Prime Minister Juha Sipilä and the National Coalition Party. This was an unusually genuine centre-right wing government for Finnish standards, where broad coalition governments across ideological divides have been the norm. Internal divisions in 2017 meant that the Finns Party left government, but key figures including former party leader Timo Soini and all cabinet ministers formed a new party Blue Alternative that remained part of the government. After the 2019 elections, the Blue Alternative was left without representation in parliament and the Finns Party regained the position as the only radical right populist party in Finland with parliamentary representation. This is still the case following the 2023 elections.

Data and variables

Description of data

Our data come from the Finnish National Elections Study collected following the 2019 national elections for parliament on 14 April 2019 (Grönlund & Borg, Citation2021). FNES forms part of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), but in addition to the comparative module also include several other relevant questions on society (see more at https://www.vaalitutkimus.fi/en/front-page/). The 2019 survey data were collected after the elections through face-to-face interviews (n = 1598) and a self-administered drop-off questionnaire (n = 753). The sample was drawn with the help of quota sampling, in which the quotas were based on NUTS3 region of residence, type of municipality of residence, mother tongue, gender and age of the respondents. In our analyses, we only rely on questions included in the face-to-face part of the survey, but some respondents are excluded due to missing data on the relevant variables. We use weighting to ensure that the reported results are valid for the Finnish population.

Dependent variables

Our two dependent variables gauge using the CI by supporting individual proposals and satisfaction with the impact of the CI on Finnish democracy. Using the CI is measured with a question where respondents are asked whether they supported any state-level citizens’ initiatives since the launch in 2012. There were four answer categories (‘Have not signed and is not going to’, ‘Have not signed but might sign’, ‘Has signed 1-2 citizens’ initiatives’, and ‘Has signed at least three citizens’ initiatives’). Since we are here interested in whether respondents have used rather than the extent of usage, this was recoded to a dichotomy (0 = ‘Did not sign’ and 1 = ’Signed at least one initiative’). Satisfaction with the CI is measured with a single question where respondents indicate their level of agreement with the statement ‘The state-level citizens’ initiative has improved the performance of democracy in Finland’. Although there may be different reasons for why people may not feel that the CI has improved democracy, this provides a proxy for support for the CI. Answers were given on a four-point Likert scale (Totally disagree – Totally agree). To make results comparable, we also dichotomise this measure (0 = Totally or Somewhat disagree; 1 = Somewhat or Totally agree). Since our dependent variables are dichotomous, we rely on binary logistic regression analyses to examine the relationships with populist attitudes.

Independent variables

Our independent variables are populist attitudes. To measure these, we follow the previous work on populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Castanho Silva et al., Citation2020; Geurkink et al., Citation2020). We rely on answers to several statements on aspects of Finnish political life, where respondents are asked the extent to which they agree. The statements in different ways probe attitudes to key populist ideas such as anti-elitism, people-centrism, and pluralism. We also include statements on attitudes towards immigration. The focus on this thick ideological position is warranted since their anti-immigration stance are frequently seen as an important part of the success of populist right-wing parties such as the Finns Party (Christensen & Saikkonen, Citation2022; Mudde, Citation2007; Schmuck & Matthes, Citation2015). Answers were given on a five-point Likert scale (Totally disagree – Totally agree). shows the statements and the distribution of answers.

Table 1. Statements on Finnish society that concern populist attitudes.

To condense the information and identify components of populist attitudes, we used exploratory factor analyses (principal component factor analysis with promax rotation). Here all items were recoded, so a higher score indicates a more populist position. The results in indicate that the variables can be condensed to three separate dimensions.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis (PCF with promax rotation).

The first dimension concerns various anti-elitist statements, which as mentioned have traditionally formed the core of research on populist attitudes (Wuttke et al., Citation2020). The second dimension we label anti-immigration since it concerns potentially negative effects of immigration. While negative attitudes to immigration does not necessarily form part of the definition of populism, it is a central thick element of ideological positions of right-wing populist parties such as the Finns Party and is therefore central for examining the interplay between thin and thick elements (Christensen & Saikkonen, Citation2022; Neuner & Wratil, Citation2022; Silva et al., Citation2023). We interpret the third and final dimension as concerning anti-pluralism since all items where respondents agree that a homogenous society with clear leadership is preferable. This dimension is also a common element in research on populist attitudes and forms part of the ideational approach to the concept (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Galston, Citation2020; Krzyżanowska & Krzyżanowski, Citation2018). While these dimensions are not the only relevant populist attitudes, they allow us to explore how both thin and thick populist attitudes are connected to using the CI.

Based on the results, we construct three sum indexes to measure each of the latent constructs. For each of these, we include all observed items with a loading > .60 and recoded them to vary between 0 and 1 with higher scores indicating more populist attitudes (Anti-elitism M = .57, SD = .23, Alpha = .79; Anti-immigration M = .50, SD = .26, Alpha = .77; Anti-pluralism M = .45, SD = .24, Alpha = .59). The coding means that higher scores on all three scales indicate more ‘populist’ attitudes. These three indexes form the independent variables in our analyses.Footnote1

Control variables

We also include various control variables that has been known to affect the propensity to use the CI (Christensen et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Huttunen & Christensen, Citation2020). These include basic demographic characteristics, namely age (age in years divided by 100 to approximate a variation between 0 and 1), gender (0 = female, 1 = male), education (four categories of educational attainment basic, intermediate, lower tertiary and tertiary) and unemployment (Employed = 0, 1 = Unemployed). We also include generalised social trust (‘Would you say that people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people’, answer on scale 0–10 recoded to vary between 0 and 1 = High social trust).

We do not include other attitudinal variables such as ideology, political trust, and satisfaction with democracy. Since there are valid reasons to expect that populist attitudes are mediated through these, this would potentially distort the results (Keele, Citation2015; Li, Citation2021; Rico & Anduiza, Citation2019).Footnote2

shows descriptive information on all variables.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

The following section contains our empirical analyses. We first examine mean values of the independent variables across levels of using the CI and satisfaction with the CI, before moving on to binary logistic regression analyses to examine the associations in more detail.

Analyses

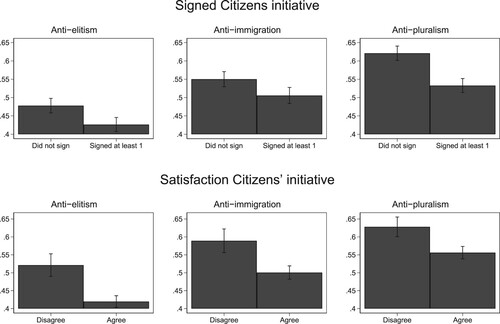

show mean scores for the three dimensions of populist attitudes depending on whether respondents had signed a citizens’ initiative or not and their level of satisfaction with the CI.

Figure 1. Mean scores across Signed a citizens’ initiative and Satisfaction with CI.

Note: The bars indicate mean scores of populist attitudes depending on having signed at least one citizens’ initiative or nor and satisfaction with CI (Agree that the CI improved Finnish democracy). Spikes are 95% confidence intervals. All scales vary between 0 and 1. Weighted data.

The mean scores show that people who have signed at least one citizens’ initiative hold lower scores on all three dimensions of populism. Those who have signed an initiative have an anti-elitist mean score of .43 compared to .48 for non-users (t(1373) = 3.65, p < .000). The anti-immigration mean score for users is .51 compared to .55 for non-users (t(1414) = 2.90, p = .004), and the anti-pluralist mean score for users is .52 compared to .62 for non-users (t(1435) = 6.34, p < .000). There is therefore no indication that people with high populist attitudes are more likely to use the CI, but rather the opposite. We see a similar pattern for satisfaction with the CI. Those who are satisfied with the CI have a score of about .42 for anti-elitism compared to about .52 for the dissatisfied (t(1224) = 5.64, p < .000), about .50 compared to .59 for anti-immigration (t(1245) = 4.61, p < .000), and .56 compared to .63 for anti-pluralism (t(1273) = 4.35, p < .000).

There is therefore consistent evidence that people with higher scores on both thick and thin populist dimensions are less likely to use or support the agenda initiative in Finland. The magnitudes of the differences vary, but at least in some cases the differences are pronounced on the scales coded 0–1.

But since populist attitudes are likely to differ across basic socio-demographic characteristics that also affect use of and attitude to the CI, we also used multiple regression analyses (binary logistic) to explore the associations when we also consider possible confounding factors. We show in the results of a series of regression models examining the results M1-M3 concern signing a citizens’ initiative while M4-M6 concerns satisfaction with the CI. M1 and M4 only include the three indexes of populist attitudes, M2 and M5 include control variables, while M3 and M6 also include interaction terms between the populist indexes.

Table 4. Regression results (Binary logistic regressions).

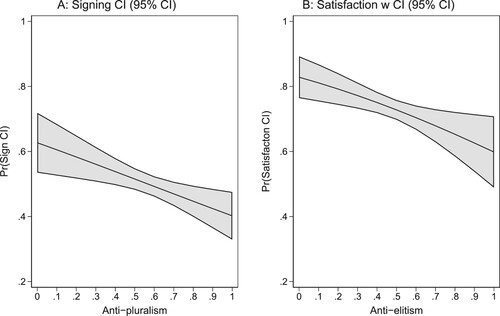

When considering other characteristics, the associations between the populist attitudes and both using the CI and satisfaction with the CI generally weakens. For using the CI, anti-elitism in M1 has a weak negative coefficient (b = −.69, p = .035), but this disappears when including the control variables in M2, indicating that this is probably due to other factors. It is only the negative association with anti-pluralism that remains significant in both M1 (b = −1.66, p < .000) and M2 (b = −1.05, p = .005). For satisfaction with the CI, anti-elitism retains a significant negative association in M1 (b = −1.51, p < .000) and M2 (b = −1.22, p = .006). To show what these associations entail, we in plot the predicted likelihood of using the CI/Being satisfied with the CI as a function of these variables.

Figure 2. Predicted developments.

Note: Plot A: predicted probability of signing a CI as a function of anti-pluralism based on M2 and M5 in Table 4. The shaded area is 95% confidence intervals. Plot B: predicted probability of being satisfied with the CI as a function of anti-elitism. The shaded area is 95% confidence intervals. Weighted data.

Populist attitudes in the form of anti-pluralism considerably reduce the predicted probability of signing CIs. Anti-elitism, in turn, reduces the likelihood of being satisfied with the CI. There is a gap of about 22 percentage points in the predicted likelihood of having signed an initiative when comparing the minimum value of anti-pluralism to the maximum value. The reduction in the increased likelihood of being satisfied with the CI decreases with about 23 percentage points as anti-elitism moves from its minimum to its maximum value.

Hence there is some evidence to suggest that populist attitudes have negative associations with the satisfaction with and the use of CIs when we consider other factors. And there is again nothing to suggest that people with higher populist attitudes are more likely to use or be satisfied with the CI.

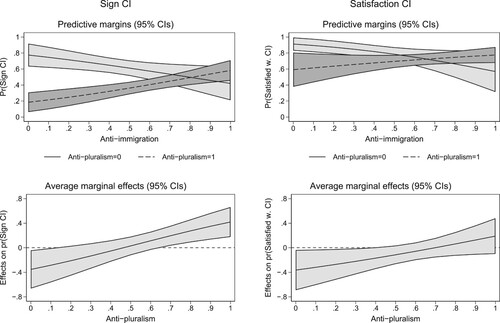

As the final part of the empirical analysis, we turn to the possibility of interplays between the three measures of populist attitudes. The results in M3 and M6 indicate that there is a significant interaction term between anti-immigration and anti-pluralism for both Signing a CI (b = 3.84, p = .004) and for Satisfaction with the CI (b = 3.09, p = .040), indicating that their associations with the dependent variables are interdependent. We in show what these significant interaction terms entail for the substantive results.

Figure 3. Implications of interaction effects: Anti-immigration x Anti-pluralism.

Note: The figure visualises how the associations for anti-immigration differ depending on the values of anti-pluralism based on M3 and M6 in Table 4. The panels on the left show results for signing a CI and the panels on the right results for Satisfaction with the CI. The top panels show developments in predicted outcomes with 95% confidence intervals as a function of anti-immigration when anti-pluralism is at minimum (0) and maximum (1) values. The bottom panels show the predicted slopes of anti-immigration with 95% confidence intervals at all possible values of anti-pluralism.

These results help explain the negligible effects of anti-immigration in previous analyses since the associations differ drastically depending on the values of anti-pluralism. This is most pronounced for having signed a citizens’ initiative, where there is a negative association between anti-immigration and the propensity to use the CI for people with low levels of anti-pluralism. In other words, people who are opposed to immigration are less likely to use the CI if they at the same time support a pluralistic society. This is reversed when people are simultaneously against immigration and a pluralist society. Under these circumstances, people become more likely to use the CI. Hence a combination of thick and thin populist attitudes may be needed to propel people into action.

The results are similar, albeit less pronounced for satisfaction with the CI. The main difference is that while there is still a positive association between anti-immigration and satisfaction when combined with high levels of anti-pluralism, the association is not significant at a conventional p < 0.05. That people who score high on both anti-pluralism and anti-immigration are more satisfied with the CI may indicate that the CI can to some extent serve as an instrument for radical right-wing demands, but anti-elitism as the essential populist trait does not necessarily contribute.

In light of these results and their deviation from previous studies examining the links between populist attitudes and referendums, we ran additional analyses to see whether the implications of populist attitudes were similar for supporting the use of referendums, which a been a customary measure in previous studies.Footnote3 In this way, we can shed light on whether the results only indicate that the Finnish context deviates from what is found elsewhere, and whether the results are related to CI as a soft form of direct democracy.

The results of these analysis are in line with previous studies on support for direct democracy since they show that the mean populist attitudes are higher for those supporting the use of referendums compared to those who do not (anti-elitism M = .53 compared to M = .34; anti-pluralism M = .61 vs M = .52; and anti-immigration M = .57 vs M = .45). When including control variables in a logistic regression model, the coefficients for anti-elitism (B = 3.56, p < .001) and anti-pluralism (B = 0.84, p = .024) remain significant while it becomes insignificant for anti-immigration (B = 0.52, p = .141). We find no significant interaction terms for the support of referendums. All these results therefore indicate that populist attitudes have different implications depending on the type of direct-democratic instrument.

Conclusions

Our findings have important implications for research on populist attitudes and their consequences for direct-democratic participation. Most previous studies have focused on populists’ attitudes on referendums, thus ignoring the variety of direct democratic institutions. Our study provides a more nuanced picture of how populist attitudes are linked to direct democratic institutions.

Our results demonstrate that populist attitudes do not generally advance neither using the CI nor being satisfied with this instrument since we find either a negative or a non-existent relationship between our three components of populist attitudes, be they thick or thin. While populist attitudes may well promote positive attitudes to the use of referendums, this is not necessarily the case for other direct-democratic instruments. This finding confirms the view that the term ‘direct democracy’ fails to account for the diversity between different types of institutions for popular initiatives and popular votes.

The Finnish agenda initiative seems to be more in line with participatory visions of democracy. It is important to note that while giving citizens opportunities to influence political decisions, the Finnish CI still leave the final decisions in the hands of elected representatives. It would seem like these ‘soft’ forms of direct democracy do not particularly cater to the demands of the populists. Hence it is important to recognise that populists seem to demand decisive instruments that place decision-making powers in the hands of the people, not just instruments that lead to greater involvement.

As concerns the difference between attitudes and actions (Trüdinger & Bächtiger, Citation2023), we find some evidence that there are differences in associations, since anti-elitism is tied to satisfaction with the CI and anti-pluralism to actually using the CI. This corroborates the finding that it is important to distinguish between attitudes and actions since they do not necessarily have the same predictors. Here it is worth noting that there may also be an intricate relationship between attitudes and actions, since belief in the instrument may spur involvement, but this involvement may cause disappointment when the involvement does not have the intended consequences (Christensen, Citation2019). It may therefore be necessary to use longitudinal data to disentangle these relationships.

Finally, our results also demonstrate that it is important to examine the interplay between thick and thin populist attitudes to understand their consequences (Christensen & Saikkonen, Citation2022; Neuner & Wratil, Citation2022). Our results show that while anti-immigration attitudes do not boost neither satisfaction with nor use of the CI, this is different when it is combined with feelings of anti-pluralism. In other words, when people combine nativism with beliefs that society should be united, it can provide a mobilising force. This is even in the absence of anti-elitism, which is often considered central to populism. This may help explain the difficulties in determining the impact of populist attitudes conclusively in previous studies, even when it comes to seemingly self-evident consequences such as voting for populist parties or candidates. Consequently, future research on consequences of populist attitudes should to a greater extent consider the possibility that it may be the interplay between these attitudes that shapes outcomes.

Our findings were obtained in a context where a populist party was in office. It would be important to examine whether the interplay between populist attitudes is similar under different circumstances, namely in situations where populist leaders are not in office and in systems with different types of citizens’ initiatives. Nevertheless, our results clearly suggest that it is important to acknowledge that the implications of populist attitudes depend on the type of direct-democratic instrument.

Author bio.docx

Download MS Word (12.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Henrik Serup Christensen

Henrik Serup Christensen is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at Åbo Akademi University in Turku, Finland. His research interests include political behaviour broadly defined and the implications for democracy.

Maija Setälä

Maija Setälä is a Professor in Political Science at the University of Turku, Finland. Setälä specialises in democratic theory, especially theories of deliberative democracy, direct democracy and democratic innovations.

Notes

1 There were moderate levels of correlations between the three indexes (anti-elitism & anti-immigration r = .43; anti-elitism & anti-pluralism r = ..41 and anti-pluralism & anti-immigration r = .49).

2 We tested the inclusion of political trust in some models, and the results suggest that there is a positive association, meaning higher trust is associated with greater involvement. Nevertheless, due to the complications involved in disentangling the relationships between populist attitudes, political trust, and the CI, we refrain from exploring this issue further here since it goes beyond our aspirations in this study.

3 Question phrasing Important national issues should more often be decided by a referendum, answers ’To some extent agree ’ or ’Strongly agree’ coded 1, ’To some extent disagree’ and ’Strongly disagree’ coded 0.

References

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Altman, D. (2011). Direct democracy worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

- Barber, B. R. (1984). Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. University of California Press.

- Bengtsson, Å, & Christensen, H. S. (2016). Ideals and actions: Do citizens’ patterns of political participation correspond to their conceptions of democracy? Government and Opposition, 51(02), 234–260. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.29

- Bengtsson, Å, & Mattila, M. (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: Support for direct democracy and ‘stealth’ democracy in Finland. West European Politics, 32(5), 1031–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903065256

- Castanho Silva, B., Fuks, M., & Tamaki, E. R. (2022). So thin it’s almost invisible: Populist attitudes and voting behavior in Brazil. Electoral Studies, 75, 102434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102434

- Castanho Silva, B., Jungkunz, S., Helbling, M., & Littvay, L. (2020). An empirical comparison of seven populist attitudes scales. Political Research Quarterly, 73(2), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919833176

- Christensen, H. S. (2019). Boosting political trust with direct democracy? The case of the Finnish citizens’ initiative. Politics and Governance, 7(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i2.1811

- Christensen, H. S., Jäske, M., Setälä, M., & Laitinen, E. (2016). Demokraattiset innovaatiot Suomessa – Käyttö ja vaikutukset paikallisella ja valtakunnallisella tasolla (pp. 96–96). http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/79817

- Christensen, H. S., Jäske, M., Setälä, M., & Laitinen, E. (2017). The Finnish citizens’ initiative: Towards inclusive agenda-setting? Scandinavian Political Studies, 40(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12096

- Christensen, H. S., & Saikkonen, I. A.-L. (2022). The lure of populism: A conjoint experiment examining the interplay between demand and supply side factors. Political Research Exchange, 4(1), 2109493. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2022.2109493

- Christensen, H. S., Setälä, M., & Jäske, M. (2019). Self-reported health and democratic innovations: The case of the citizens’ initiative in Finland. European Political Science, 18(2), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0167-6

- el-Wakil, A., & McKay, S. (2020). Introduction to the special issue ‘beyond “direct democracy”: Popular vote processes in democratic systems’. Representation, 56(4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2020.1820370

- Galston, W. A. (2020). Anti-Pluralism: The populist threat to liberal democracy. Yale University Press.

- Geurkink, B., Zaslove, A., Sluiter, R., & Jacobs, K. (2020). Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: Old wine in new bottles? Political Studies, 68(1), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719842768

- Gherghina, S., & Geissel, B. (2017). Linking democratic preferences and political participation: Evidence from Germany. Political Studies, 65(1_suppl), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716672224

- Gherghina, S., & Pilet, J.-B. (2021). Populist attitudes and direct democracy: A questionable relationship. Swiss Political Science Review, 27(2), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12451

- Gherghina, S., & Silagadze, N. (2020). Populists and referendums in Europe: Dispelling the myth. The Political Quarterly, 91(4), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12934

- Grönlund, K., & Borg, S. (2021). Finnish National Election Study 2019 [dataset]. Version 2.0 (2021-09-15). Finnish Social Science Data Archive [distributor]. http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:fsd:T-FSD3467

- Huttunen, J., & Christensen, H. S. (2020). Engaging the millennials: The citizens’ initiative in Finland. YOUNG, 28(2), 175–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308819853055

- Iakhnis, E., Rathbun, B., Reifler, J., & Scotto, T. J. (2018). Populist referendum: Was ‘Brexit’ an expression of nativist and anti-elitist sentiment? Research & Politics, 5(2), 205316801877396. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018773964

- Jäske, M. (2017). ‘Soft’ forms of direct democracy: Explaining the occurrence of referendum motions and advisory referendums in Finnish local government. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(1), 50–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12238

- Jäske, M., & Setälä, M. (2020). A functionalist approach to democratic innovations. Representation, 56(4), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1691639

- Jungkunz, S., Fahey, R. A., & Hino, A. (2021). How populist attitudes scales fail to capture support for populists in power. PLoS One, 16(12), e0261658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261658

- Keele, L. (2015). The statistics of causal inference: A view from political methodology. Political Analysis, 23(03), 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpv007

- Kokkonen, A., & Linde, J. (2023). Nativist attitudes and opportunistic support for democracy. West European Politics, 46(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2007459

- König, P. D. (2022). Support for a populist form of democratic politics or political discontent? How conceptions of democracy relate to support for the AfD. Electoral Studies, 78, 102493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102493

- Krzyżanowska, N., & Krzyżanowski, M. (2018). ‘Crisis’ and migration in Poland: Discursive shifts, anti-pluralism and the politicisation of exclusion. Sociology, 52(3), 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518757952

- Li, M. (2021). Uses and abuses of statistical control variables: Ruling out or creating alternative explanations? Journal of Business Research, 126, 472–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.037

- Lutz, G. (2012). Switzerland: Citizens’ initiatives as a measure to control the political agenda. In M. Setälä & T. Schiller (Eds.), Citizens’ initiatives in Europe: Procedures and consequences of agenda-setting by citizens (pp. 17–36). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Manucci, L., & Amsler, M. (2018). Where the wind blows: Five star movement’s populism, direct democracy and ideological flexibility. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica, 48(01), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2017.23

- Mohrenberg, S., Huber, R. A., & Freyburg, T. (2021). Love at first sight? Populist attitudes and support for direct democracy Party Politics, 27(3), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819868908

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Neuner, F. G., & Wratil, C. (2022). The populist marketplace: Unpacking the role of “thin” and “thick” ideology. Political Behavior, 44(2), 551–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09629-y

- Oikeusministeriö. (2010). Perustuslain tarkistamiskomitean mietintö (Sarjajulkaisu 9/2010; Mietintöjä ja lausuntoja). Oikeusministeriö. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/76201

- Olivas Osuna, J. J., & Rama, J. (2022). Recalibrating populism measurement tools: Methodological inconsistencies and challenges to our understanding of the relationship between the supply- and demand-side of populism. Frontiers in Sociology, 7, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fsoc.2022.970043

- Qvortrup, M. (2013). Direct democracy: A comparative study of the theory and practice of government by the people. Manchester University Press.

- Rico, G., & Anduiza, E. (2019). Economic correlates of populist attitudes: An analysis of nine European countries in the aftermath of the great recession. Acta Politica, 54(3), 371–397. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-017-0068-7

- Schiller, T., & Setälä, M. (2012). Introduction. In M. Setälä & T. Schiller (Eds.), Citizens’ initiatives in Europe (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Schmuck, D., & Matthes, J. (2015). How anti-immigrant right-wing populist advertisements affect young voters: Symbolic threats, economic threats and the moderating role of education. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(10), 1577–1599. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.981513

- Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2018). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(2), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw037

- Setälä, M., & Schiller, T. (2012). Citizens’ initiatives in Europe: Procedures and consequences of agenda-setting by citizens (M. Setälä & T. Schiller, Eds.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Silva, B. C., Neuner, F. G., & Wratil, C. (2023). Populism and candidate support in the US: The effects of “thin” and “host” ideology. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 10(3)438–447. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2022.9

- Smith, G. (1976). The functional properties of the referendum. European Journal of Political Research, 4(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1976.tb00787.x

- Su Seo, H., & Raunio, T. (2017). Reaching out to the people? Assessing the relationship between parliament and citizens in Finland. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23(4), 614–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2017.1396694

- Trüdinger, E.-M., & Bächtiger, A. (2023). Attitudes vs. Actions? Direct-democratic preferences and participation of populist citizens. West European Politics, 46(0), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2023435

- Welp, Y. (2022). The will of the people: Populism and citizen participation in Latin America. De Gruyter.

- Werner, H., & Jacobs, K. (2022). Are populists sore losers? Explaining populist citizens’ preferences for and reactions to referendums. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1409–1417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000314

- Wuttke, A., Schimpf, C., & Schoen, H. (2020). When the whole is greater than the sum of its parts: On the conceptualization and measurement of populist attitudes and other multidimensional constructs. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000807

- Zaslove, A., Geurkink, B., Jacobs, K., & Akkerman, A. (2021). Power to the people? Populism, democracy, and political participation: A citizen’s perspective. West European Politics, 44(4), 727–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1776490