ABSTRACT

Why do citizens support holding a referendum? In this article, we argue that citizens are instrumental by using heuristics and cues from parties, independent experts, and the population to decide whether to hold a referendum. We further expect that populist and non-populist citizens differ in how they respond to these cues. Using pre-registered survey experiments in Austria and Germany, we find that citizens’ support depends mainly on their attitudes towards the respective policy and the opinion of their preferred party, while the views of experts and the public play only a subordinate role. Crucially, we find no systematic differences between populist and non-populist citizens, suggesting that even populists’ support for holding a referendum depends mainly on instrumental rather than normative considerations. This study provides comprehensive insights into the causal mechanisms of support for direct democracy and their implications for liberal and representative democracy.

1. Introduction

In the wake of the contentious Brexit referendum, the discussion surrounding the political significance of direct democracy has resurfaced with increased intensity. This controversial debate has been fuelled in particular by populist actors who promote the direct involvement of the people in decision-making processes as a counter-model to liberal and representative democracy. Moreover, given the high public approval of direct democratic procedures in Western democracies (Dalton et al., Citation2001), previous research aimed to better understand which citizens support referendums and why (Schuck & De Vreese, Citation2015).

One strand of research suggests dissatisfaction with the policies pursued by representatives as the main argument for citizens to demand a referendum on policy issues (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Citation2002). Accordingly, people tend to support holding a referendum if they expect it to deliver the desired political outcome (Landwehr & Harms, Citation2020). Others, by contrast, find that citizens who are both deeply engaged in politics and committed to democratic practices are also more supportive of direct democratic instruments (Schuck & De Vreese, Citation2015). At the same time, referendums such as the Brexit vote have also made citizens more aware of potential negative consequences (Steiner & Landwehr, Citation2023).

Most studies, however, do not consider the complexity of the decision-making process, in which citizens are influenced by various factors when deciding whether or not to hold a referendum on a particular policy issue. Moreover, the question of whether populist and non-populist citizens differ in how they respond to these factors has not yet been sufficiently explored. Given the seemingly conflicting trends about how populations may think about referendums and the varying accounts offered by the literature, our research question is: Why do citizens support holding a referendum?

In this article, we argue that support for holding referendums can be explained by citizens’ normative or instrumental considerations. By normative considerations, we mean that citizens base their expectations on general ideas about how they want democracy to work (Bowler et al., Citation2007). Instrumental considerations refer to citizens taking a more rational approach by anticipating the mode of democratic decision-making that would deliver the desired policy outcome (Werner, Citation2020). Put differently, the support for referendums among citizens depends on whether they see themselves as winners of the process (Marien & Kern, Citation2018).

In addition, a common explanation of political attitudes and political decision-making in behavioural research is that individuals employ certain heuristics and short-cuts: This may matter whenever a party favoured or disfavoured by a voter supports or rejects the idea of a referendum on a given policy proposal (Grotz & Lewandowsky, Citation2020). Besides party cues, also the opinion of experts or the public at large on a proposed referendum may sway voters in their evaluation of whether to hold a referendum on a proposed policy (Beiser-McGrath et al., Citation2022). This way, citizens can overcome informational deficits and gaps in their knowledge by relying on other sources they trust (Darmofal, Citation2005; Hobolt, Citation2007).

Drawing on the theoretical conception of the ideational approach to populism, we expect that populist citizens would prefer referendums because it represents a form of decision-making that transfers power away from elites and closer to the people (Jacobs et al., Citation2018). By implication, this also means that normative considerations about how democracy is to work is inherent in the concept of populism (Wegscheider et al., Citation2023). We also expect the mechanism of cue-taking in decision-making to work in different ways for citizens with a populist mindset than for those without. Our argument here is based on the idea that the central tenant of ideational populism divides society into two antagonistic homogenous groups: the good people functioning as the in-group and the nefarious, corrupt elite forming the out-group (Mudde, Citation2004; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017). Following Bos et al. (Citation2020), we argue that populism leads to a stronger connection with the in-group and a stronger rejection of the out-group. This effect should be observable in cue-taking as well. Therefore, we expect the effect of decision-taking through cues to be stronger for populist citizens than for non-populists if the cues come from the populist in-group (e.g. the party favoured by the populist citizen and the public) and weaker than for non-populists when the cue is considered coming from the populist out-group (e.g. independent experts and parties not favoured by the populist citizen).

Our goal is to explain the factors that influence citizens’ decision-making when it comes to how they decide on a particular policy issue. In order to explain under which circumstances citizens are in favour of holding a referendum and under which circumstances they are against, we will first account for the difference between normative and instrumental considerations in the decision-making process, then we examine how each is related to cue-taking mechanisms of decision-making, and lastly, we ascertain to what extent populist citizens differ from non-populist citizens in these aspects.

To test this, we conduct a pre-registered conjoint experiment embedded in original surveys in Austria and Germany. Prior to the experimental components, we measure respondents’ policy preferences, party identification, preference for direct democracy, and populist attitudes. In the conjoint experiment, we randomise the proposed policy as well as the support or rejection of holding a referendum as expressed by the public, experts, and political parties. We formulate seven hypotheses designed to test the various effects on people’s preferences for referendums shaped by their own policy positions as well as by party cues, expert cues, and popular support cues. In a second step, we differentiate between populists and non-populists, i.e. people who hold populist attitudes and those who do not and assess differences in strength and direction of the respective effects of cues between the two groups.

In our analysis, we show that people are indeed more likely to support holding a referendum if it reflects their policy preferences. We also determine that party cues matter in the hypothesised direction and find a positive effect on holding a referendum resulting from expert cues and public support. With respect to the populist mindset, by contrast, we find very few differences in both countries. Interestingly, German populists do not react to the public cue while non-populists do, which might be rooted in a general skepticism of German populists towards the societal ‘mainstream’. This cross-national study significantly adds to the literature by providing new insight into the causal mechanisms of approval and disapproval of holding a referendum.

Our paper is organised as follows: First, we reflect the state of the literature and present our theoretical argument and hypotheses. Subsequently, we introduce our research design and describe the survey experiment in detail. In the fourth section, we present the analysis and findings to be followed by our conclusions.

2. Theoretical argument

2.1. Who supports holding a referendum and why?

Previous research shows that citizens’ support for holding a referendum depends on a combination of variables. The explanations for why someone is in favour or against a particular political issue to be decided by referendum rather than by parliament and/or government in Western democracies are diverse (Beiser-McGrath et al., Citation2022; Bowler et al., Citation2007; Donovan & Karp, Citation2006; Rojon & Rijken, Citation2021; Schuck & De Vreese, Citation2015; Werner, Citation2020). In the following, we provide an overview of hypotheses and explanations from previous research on the causes for favouring and opposing referendums in general. As a first step, we describe the general reasoning behind considerations related to referendums before turning to the question as to what extent populists differ from non-populists in this regard.

First, we explain the role of the citizens’ policy position vis-à-vis the position brought forth by the referendum in question, before turning to explaining the mechanisms by which we expect citizens to rely on different cues in deciding whether or not to hold a referendum. More concretely, we discuss the role of the following cues: the preferred and non-preferred parties, independent experts, and a majority of the general public. We argue that citizens not only have general attitudes towards referendums, but they also act in an instrumental way in their support for referendums and therefore take into account the content of the policy, the opinion of their preferred (non-preferred) parties on holding a referendum, and the opinion of independent experts and a majority of the public.

2.2. The dimension of political attitudes

In addition to what Werner calls ‘baseline attitude towards referendums which is shaped by values and evaluation of politicians generally’ (Werner, Citation2020, p. 314), more issue- and policy-driven components of decision-making about supporting or opposing holding referendums have received attention in the recent literature. Political positions not only influence which party citizens choose on election day, but also how they want to make decisions more generally. For example, Wojcieszak (Citation2014) finds that, on average, citizens in Spain prefer decisions on ‘simple’ and symbolic issues such as abortion to be made with more citizen participation. In contrast, for more complex questions, such as issues related to the economy, citizens prefer representatives to make the decisions rather than involving citizens as people tend to embrace the concept of stealth democracy for these types of topics (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Citation2002).

Regarding the policy position on the issues, Wojcieszak (Citation2014) finds that citizens with extreme positions on the issues of abortion and immigration are more likely to prefer participatory processes in decision-making over representatives’ decision-making. We argue that this is the case because extreme policy preferences are, on average, further away from the status quo established by representative political decisions with relatively little citizen participation, that is, without a referendum (see also Beiser-McGrath et al., Citation2022). Following Werner’s (Citation2020) reasoning that preferred processes of policymaking are also instrumental, we argue that citizens choose the arena in which they believe their preferred policy outcome is most likely to be achieved. Dyck and Baldassare (Citation2009), for example, find a correlation between rejection of direct democratic elements and rejection of the proposed policies that are subject of these referendums in U.S. states.

In this sense, we expect citizens to try to maximise their chances to receive the desired policy outcome and take into account which democratic decision-making process is likely to increase that potential. On any given policy issue, citizens might favour keeping the status quo (0), or moving from the status quo in one direction (−1) or the other (1). We hypothesise that citizens are more likely to support a referendum to be held if it calls for a change in the status quo in the direction that aligns with their attitude on that policy. This preference, we argue, results from the fact that the referendum offers at least a greater than zero chance of changing the status quo in the preferred direction. Although citizens may have a baseline attitude whether they favour or oppose referendums, we nevertheless expect the content of the policy to affect this general attitude. Therefore, our first hypothesis is:

(H1) Policy preference: People are more likely to support holding a referendum if it reflects their policy preferences.

In other words, citizens tend to follow heuristics and cues without delving deeper into the content. Instead, depending on the degree of confidence or trust in the cue, they adjust the preferences shaped by the cue. In this paper, we put three types of cues to the test: a favoured (non-favoured) political party, independent experts, and a majority of the public.

2.3. The party cue

When a referendum is pending, a party may, for political or strategic reasons, promote resolving the issue in question through a referendum or oppose holding a referendum on the issue. We expect citizens to respond to the opinion of their favoured or non-favoured party by adopting the favoured party's position or by supporting having a referendum if the unfavoured party opposes it. Citizens might do this for two reasons: As noted earlier, lack of interest and/or knowledge in a policy field or in politics altogether might lead them to use cues as heuristic short-cuts and thus as a rational means of avoiding efforts of a deeper engagement with the issue. In contrast, scholars have also identified a different reason for using cues, which is used by citizens who are highly engaged in politics and have high levels of political sophistication. This latter form of cue-taking is not about saving effort but expressing one's party affiliation by aligning one's opinion with that of a preferred party (Bakker et al., Citation2020; Cohen, Citation2003; Huddy et al., Citation2015). In this sense, Petersen et al. (Citation2013) suggest that considering party cues makes some people even more likely to engage in effortful motivated-reasoning because they want to figure out why their party is supposedly right about the issue at hand.

Research has indeed found both mechanisms at play when participants of experiments were confronted with policy positions to be decided and the stated positions of preferred and non-preferred parties on the matter at hand (Bakker et al., Citation2020; Kam, Citation2005; Malka & Lelkes, Citation2010). In a slightly modified form, we are interested in when citizens use cues if considering how to decide on an issue. More specifically, whether or not to hold a referendum about the issue at hand. We expect this mechanism to work in the same direction for opinions about process as it does for opinions about policies, which is also evident when citizens are asked to vote in a referendum (Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2021; Hobolt, Citation2006). This means that we expect people to rely on their favoured party heuristic and decide against the heuristic of the non-favoured party when deciding whether or not to support holding a referendum. Therefore, we hypothesise:

(H2) Party cue: People are more likely to support holding a referendum if it is (H2a) supported by a favored party or (H2b) opposed by a non-favored party.

2.4. The expert cue

Scholars have identified that in addition to party cues, citizens also use heuristics drawn from other sources in a variety of policy areas (Case et al., Citation2021; Darmofal, Citation2005; Thon & Jucks, Citation2017). The role of experts and scientists in influencing attitudes towards policies should similarly serve as a reference point to which citizens refer when deciding whether or not to hold a referendum when deciding on a given policy issue.

While populists, amongst others, have become known for their distrust in experts and scientists (Merkley, Citation2020), this finding does not hold for the population in total (Darmofal, Citation2005). Juen et al. (Citation2021) find, for example, that in the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, citizens not only followed party cues, but also those by public health experts with regard to mandatory vaccinations in Germany. However, citizens differentiate between reliable and unreliable experts (Hendriks et al., Citation2015). The role of experts is crucial as the citizens need to trust them about complex scientific findings that they are themselves not able to observe. This also means that trusting what experts say is a vulnerability when citizens are intentionally or unintentionally lied to. Citizens may for different reasons trust one expert but mistrust another. They might also put trust in alleged experts that are actually not trustworthy (Mihelj et al., Citation2022). We have to keep the ambivalence in mind when interpreting our results.

While some research indicates ambivalent effects of citizens’ support for expert governments (Gherghina & Geissel, Citation2017), we follow the general findings of previous studies that citizens use experts as information short-cuts and expect the heuristic mechanisms when following expert cues to work similar to the ones being at work when following party cues. The causal mechanism of effort-avoidance implies that citizens follow experts’ advice because it is a convenient and efficient way to make a decision. By comparison, the motivated-reasoning model implies a more in-depth engagement with a political subject matter as reaction to an expert’s recommendation (Gilens & Murakawa, Citation2002).

Again, we deviate from other studies by asking for the preferred arena of the decision instead of for the preferred policy:

(H3) Expert cue: People are more likely to support holding a referendum if it is supported by independent experts.

2.5. The public support cue

The final cue we analyse is public support for holding a referendum. We assume that citizens use the heuristic of being part of a majority when deciding whether to favour or oppose holding a referendum on an issue at hand. The mechanism used in this form of cue-taking goes back to social identity theory (Tajfel et al., Citation1971). Applied to voting behaviour, Coleman (Citation2004) finds evidence for conformist voting behaviour in general, arguing that social-psychological mechanisms lead citizens to adopt the majority viewpoint (Bond & Smith, Citation1996). This effect of voting coherently with peers and therefore being in the majority has also been found in neighbourhoods that tend to align with the party for which these citizen vote (MacAllister et al., Citation2001). Again, we are interested in the attitude towards the process of decision-making rather than in the opinion on the respective policy. Wratil and Wäckerle (Citation2023), for example, show that political decisions are perceived as more legitimate if the majority of the public approves.

We follow this reasoning and formulate our hypothesis accordingly:

(H4) Public support: People are more likely to support holding a referendum if it is supported by the public.

2.6. Populist citizens and support for holding a referendum

There is a considerable literature suggesting that citizens may favour supporting direct and participatory models of democracy as an alternative to parliamentary decision-making (i.e. Bedock & Pilet, Citation2020, Citation2021; Coffé & Michels, Citation2014; Gherghina & Geissel, Citation2019, Citation2020; von Schoultz & Christensen, Citation2016). Here, the drivers are factors such as dissatisfaction with democracy, general doubts about politicians’ commitment to public interest, a citizen’s political efficacy and interest, and/or personal experiences with participatory forms of democracy (for a detailed analysis, see Gherghina and Geissel (Citation2020)). Nonetheless, Bedock and Pilet (Citation2020) demonstrate that while citizens who are enraged (politically dissatisfied) and citizens who are engaged (politically efficacious) are both more supportive of participatory models of democracy.

But what about citizens with populist inclinations? In short, we wonder about the support for referendums among people whose ideological predispositions, as explained below, would make them inherently suspicious of decisions made by political actors and institutions that might be viewed as elitist and potentially nefarious. More specifically, what kinds of cues matter to such citizens? Following our concept of populism presented below, we test whether there are differences between populist and non-populist citizens with respect to the types of cues presented above. The literature to date has treated the question of populism and the use of direct democratic means in a variety of ways and with different emphases:

The most commonly used concept of populism as a set of ideas that (also) reside at the individual-level and thus on the demand-side (Hawkins et al., Citation2018; Mudde, Citation2017) has recently been shown to be a relevant explanatory factor for attitudes towards referendums. With respect to the sub-dimensions of populism, namely people-centeredness, anti-elitism, and a Manichean worldview, the argument is as follows: Part of being anti-elite, apparently, is that populist citizens themselves claim to know what is best for the people, which in turn is seen as volonté générale. Moreover, as referendums by nature result in presenting a dichotomous choice, winners do not have to make compromises with the losing side, which in general should be favourable for populist citizens (Rose & Weßels, Citation2021). This means that referendums add a clearly majoritarian element to democracy that fits better with the populists’ Manichean idea of a society divided between good and evil, between the elite and the people (Heinisch & Wegscheider, Citation2020; Werner & Jacobs, Citation2021). In general, previous research found that populist citizens are more likely to support referendums than non-populist citizens (Jacobs et al., Citation2018; Mohrenberg et al., Citation2021).

In addition to this argument, we expect that all three cues discussed above (party cue, expert cue, and public support cue) differ in their effects between populist and non-populist citizens. As the measure of populism on the individual-level is a more recent approach in comparison to measuring populism in parties (Dolezal & Fölsch, Citation2021), research applying populist attitudes as an independent variable to explain direct democracy is likewise a new strand of research. Gherghina and Pilet (Citation2021) point to the caution that should be exercised when analysing the effects of individual-level populism on attitudes towards direct democracy. To address possible difficulties arising from that, we focus in our study on the difference between populist and non-populist citizens’ perceptions of cue-taking when deciding a policy by a referendum. By being as specific as possible about the referendum at hand, we avoid measuring only vague approval of the instruments of direct democracy.

To begin with, we assume that the party cue explained above works differently for populist citizens than for non-populist citizens. The Manichean worldview of populists (i.e. the perception of the world essentially as a struggle between the good and the evil) leads to a stronger effect of the good, favoured party or the bad, non-favoured party. The mechanism explained above that concerns the alignment of citizens in homogenous groups, is supposed to be an even stronger factor for the group of populist citizens. In fact, division in in-groups and out-groups and therefore a distinction between us and them is a facet associated with populism (Brubaker, Citation2017; Obradović et al., Citation2020). We therefore expect the effect of party cue to be even stronger for populist citizens:

(H5) Party cue: The expected effect in (H2) is stronger for populist citizens: Populist citizens are more supportive of holding a referendum than non-populist citizens if it is (H5a) supported by their party or (H5b) opposed by a non-favored party.

In general though, we expect that populist citizens perceive experts as being collaborators of the bad side of the Manichean divide and suppress the will of the good people (Mede & Schäfer, Citation2020).

(H6): Expert cue: The expected effect in (H3) is reversed for populist citizens: Populist citizens are more likely to oppose holding a referendum than non-populist citizens if it is supported by independent experts.

(H7): Public support: The expected effect in (H4) is stronger for populist citizens: Populist citizens are more supportive of holding a referendum than non-populist citizens if it is supported by the public.

3. Research design

To test the hypotheses described above, we employed pre-registered conjoint experiments embedded in two original surveys conducted in Austria and Germany.Footnote1 We consider these two countries to be good cases to show the interplay of populist attitudes and stances on direct democracy. While these two countries speak to all those cases with comparable parliamentary systems, Germany and Austria are not only politically similar to each other in many ways, but they are both also neighbours of Switzerland, which has the most direct-democratic political system worldwide. Due to the latter’s linguistic, cultural, and geographic proximity, Switzerland has always served as a reference case in political discourses on direct democracy issues. For these reasons, we included Switzerland as a heuristic for the Austrian and German respondents in our experiment.

Importantly, however, Germany and Austria differ in two important respects that matter here: the success of populist radical right parties and the constitutional possibilities of direct democratic instruments. While the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), founded in 1956, has a long tradition and entered state and federal governments several times, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) was founded only in 2013 and has, by this point, not been in any government. Another difference between Austria and Germany is that the latter also includes a leftist populist party, the Left (Linke), which is represented both in the national parliament and at the state level. Since populist parties tend to argue for direct democracy as a means to empower the people, the levels of exposure of Austrians and Germans to these arguments differ.

As regards the availability of direct democratic instruments, it should be noted that in Austria both binding and non-binding referendums are possible on the federal level, while in Germany referendums are only possible on sub-national matters (apart from a new delimitation of the federal territory). Nevertheless, thus far only three national referendums have been held in Austria: on nuclear power (1978), on EU membership (1994), and (non-binding) on compulsory military service (2013). Therefore, we argue that the experience with referendums is mostly similar for Austrian and German citizens, while Switzerland is generally regarded as a country with more extensive direct democratic possibilities. Given these differences and similarities, we believe that our case selection adds to the robustness of our research design and further validates our findings.

Our survey experiments were conducted by the Austrian survey company Market Institute at the end of May 2022. The surveys comprised a targeted sample size of 1,100 respondents each for Austria and Germany.Footnote2 The samples are representative of the Austrian and German electorates by gender, age, region, and education.Footnote3 We use completely randomised conjoint experiments in which respondents are exposed to short vignettes containing information about two hypothetical referenda (Hainmueller et al., Citation2014). As shown in the example in , these vignettes vary concerning (1) the proposed policy of the referendum as well as the support of (2) the public, (3) independent experts, and (4) political parties for holding the referendum. As we are not interested in respondents’ policy positions per se, we included policy areas that are salient in both countries so that most respondents have an opinion on them. We included policies related to welfare, carbon tax, immigration, and public security and thus cover the political spectrum from rather left to rather right policy proposals. Among the public and independent experts, we vary between support, opposition, and no clear opinion on holding the referendum, while political parties either demand or reject holding a referendum. All dimensions and attributes of the conjoint experiments are shown in Table A2 in the Online Appendix.Footnote4 Respondents are introduced to the experiment with the following informational text:

In Switzerland, major political issues are decided not by elected politicians but directly by the people through referendums. Imagine that this model is also applied in Austria [Germany]. Below we show you two different referendums where there are different views on the implementation among the population, experts, and parties. Please tell us which referendum you think should be held: A or B?

Table 1. Example of the conjoint experiment.

Prior to the conjoint experiment, respondents answer a series of questions that allows us to match their party and policy preferences with the attributes in the experiment.Footnote8 To measure party preference, we use the individual propensity to vote (PTV) for all parties represented in the national parliaments of Austria and Germany. Respondents are asked on an 11-point scale from ‘very unlikely’ (0) to ‘very likely’ (10) how likely it is that they would ever vote for each of the parties. Franklin and Lutz (Citation2020) show that the PTV question is well suited to provide information on party preference. We use values of ≥ 5 as the cutoff point and match this information with the respective party in the experiment.Footnote9 To measure policy congruence, respondents were asked on an 11-point scale about their position on the four policies used in the experiment. We use this information and calculate whether a respondent is congruent, neutral, or incongruent with the policy position in the experiment.Footnote10

To analyse whether populist and non-populist citizens differ in how they respond to the treatments, we measure respondents’ populist attitudes using the scale developed by Castanho Silva et al. (Citation2018). The items and theoretical sub-dimensions are listed in . Respondents are asked on a five-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5) how much they agree with each statement. Following the approach of Castanho Silva et al. (Citation2018), we use confirmatory factor analyses to calculate factor scores for each of the sub-dimensions and multiply these scores to estimate respondents’ populist attitudes. We distinguish between populist and non-populist citizens by using the mean of populist attitudes as a threshold. As shown in Figure A5 in the Online Appendix, this results in 437 (40%) of 1104 respondents in Austria and 400 (36%) of 1107 respondents in Germany being classified as populists. As additional robustness tests, we also use a scale calculated from the arithmetic mean of all nine items and use the median, terciles and quartiles to further distinguish between populist and non-populist citizens.

Table 2. Items for measuring populist attitudes.

To test the hypotheses about how the treatments affect citizens’ support for holding referendums (H1-H4), we follow Leeper et al. (Citation2020) by estimating and plotting marginal means. Marginal means describe the average probability of choosing a referendum with a particular characteristic and are thus the effects of the treatments in our experiments on support for holding a referendum. To analyse the hypotheses whether populist and non-populist citizens differ significantly in how they respond to the treatments (H5-H7), we compute conditional marginal means representing the differences in marginal means between the subgroups (Leeper et al., Citation2020). Marginal means are shown with their respective 95% confidence intervals representing the uncertainty of the estimation.

In addition to the marginal means, we report average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for the main analyses in the Online Appendix.Footnote11 We calculate the AMCEs using linear regression models with standard errors clustered by respondents. To control for potential imbalances in sample composition or randomisation, we compute the linear regression models with and without the following covariates:Footnote12 We include the age of the respondents in years, their stated gender (female/male), whether they have received a high-school diploma (Matura/Abitur), and their income situation. We further include political interest using a five-point scale as well as the left-right self-placement using an 11-point scale.

4. Empirical results

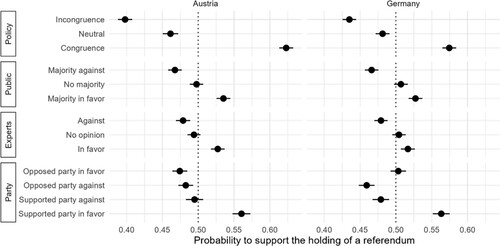

In the first step of the analysis, we test hypotheses H1 to H4, which state that respondents are more likely to support holding a referendum if it matches their policy preference as well as provides positive cues from the public, independent experts, and their preferred party. shows the marginal means of each treatment in the conjoint experiments for Austria and Germany, according to which coefficients on the left of the dashed line indicate a negative effect and coefficients on the right indicate a positive effect on support for holding a referendum. The figure only shows the analysis with the recoded treatments for reasons of space and readability. The original results of the analyses without recoding can be found in Figures A9 and A10 and Tables A9 and A10 in the Online Appendix.

Figure 1. Marginal means of support for holding a referendum. Notes: Plot shows marginal means with 95% confidence intervals. Tables A11 and A12 in the Online Appendix shows the respective results when estimating AMCEs.

shows in both countries a very strong confirmation of hypothesis H1 that people favour holding a referendum if it reflects their policy preferences. While agreement with the policy position increases the support for holding a referendum by about 7.5-12.5%, disagreement decreases the probability by a similar effect size. This illustrates that instrumental considerations about the preferred policy have a strong influence on the support of direct democratic instruments.

Turning to hypothesis H2, we investigate whether people are more likely to support holding a referendum if it is (H2a) supported by a favoured party or (H2b) opposed by a non-favoured party. As shown in , we find strong support for hypothesis H2a in both Austria and Germany, as respondents are about 6% more likely to support holding a referendum if a preferred party demands it. This result illustrates the strong impact of partisan cues in shaping public opinion. However, with respect to hypothesis H2b, we do not find that respondents in general support holding a referendum when it is opposed by a disliked party. In both Austria and Germany, we find that respondents are more likely to oppose holding a referendum when an unfavoured party opposes it. As shown in , the effect for Germany is even stronger than for Austria. Interestingly, we find that if an unfavoured party supports holding a referendum, Austrian respondents are more likely to oppose the referendum, while we do not find a significant effect for Germany. In other words, we do not find evidence for citizens in Germany reacting to cues of an unfavoured party. A possible explanation might be the difference in size of the unfavoured party. We find that in our sample most citizens feel negative towards the FPÖ and the AfD, respectively. As the AfD in Germany is small compared to the FPÖ in Austria, citizens might dismiss their opinion on referendums more easily.

Furthermore, allows us to examine hypotheses H3 and H4 stating that the positive opinion of experts and the public increases respondents’ support for holding a referendum. We find that both hypotheses hold in both countries, as the probability of supporting the holding of a referendum increases with the support by experts and the public and decreases with opposition from these two groups. However, we also find that the effects play a smaller role compared to the importance of policy and party preferences, increasing or decreasing the probability to support by only about 2.5%. Interestingly, the effects of the expert and public cues are a bit more pronounced in Austria than in Germany. This could simply reflect the different constitutional possibilities, that the idea of holding a referendum is not as tangible for German respondents as it is for Austrians, where this idea is established at least as a rare but possible political step and in line with the constitution. Nonetheless, there is a manifest effect when experts and the public speak out for or against a referendum, leading us to confirm both H3 and H4.

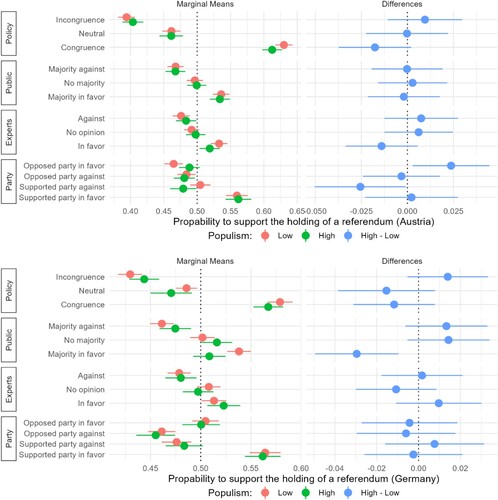

In the next step of the analysis, we examine our hypotheses H5 to H7 that populist and non-populist citizens differ in how they respond to party, expert, and public cues. The left plots in show the marginal means for populist and non-populist citizens, while the right plots indicate whether the differences are statistically significant. As explained in the section on our research design, respondents are classified as populists if they score above average on the populist attitudes scale.

Figure 2. Marginal means for populist and non-populist citizens. Notes: The left plots show marginal means with 95% confidence intervals for populists and non-populists grouped by the mean. The right plots illustrate the estimated differences in marginal means between the groups.

First, we test hypothesis H5 that populist citizens are more responsive to party cues because of their stronger position on in-groups versus out-groups. As shown in , there are no significant differences with respect to the party cue, as populist respondents are neither more supportive of holding a referendum when it is supported by a preferred party nor when it is opposed by a non-preferred party. Austrian respondents with populist attitudes, however, show a slightly stronger reaction to the party cues than do those without populist attitudes. Yet, this too, confirms that populists follow the parties’ views to the same extent as non-populist respondents.

Finally, we turn to hypotheses H6 and H7 to test whether populist and non-populist citizens react differently to the views of experts and the public in their support for holding a referendum. Hypothesis H6 states that the support by experts for a referendum decreases the probability of support by populists. However, as can be seen in , we have to reject this hypothesis as there are no significant differences in evidence between populist and non-populist respondents in either Austria or Germany. Accordingly, populist citizens follow the opinions of experts to the same small extent as non-populist citizens. However, we must note that this could also be affected by the type of experts as well as the corresponding policy. As explained above, respondents might think of different experts and thus differ in ascribing trustworthiness to them. Moreover, when thinking of different experts, respondents might even have associated their own experts with the question and thus endorsed their expertise, as we explored in more detail above. In addition, perceptions of expertise might differ across different policy fields. This potentially leads to ambiguity in our measurement.

Hypothesis 7 states that the positive effect of the public’s support is stronger among populist respondents compared to non-populists. shows no such effect in Austria and even the opposite effect in Germany, which is why we must reject this hypothesis. German populists are no more likely to choose a referendum if the public supports it, while non-populists are more likely to support the holding of a referendum. This speaks to a certain distrust of German populists towards their country’s general public which might be rooted in the experience of the rejection of Germany’s largest populist party, the Alternative for Germany, by large segments of the mainstream society and the resulting political polarisation.

Overall, we have to conclude that there are hardly any significant differences between populists and non-populists in responding to party, expert, and public cues in both Austria and Germany. This leads to derive the following important insights: First, there is no evidence of a stronger reaction to cues among populist citizens compared to their non-populist counterparts. This also means that populists follow instrumental considerations in the form of party and policy preferences in the same way as non-populist respondents do. Conversely, the normative claims regarding citizen participation and reform of the democratic system that are often part of populist discourse are likely to be a pretext for promoting one's own policy preferences and thus grounded in instrumental arguments to improve representation (Huber et al., Citation2023). Second, despite the constitutional differences in referendum options in Germany and Austria, there is no evidence that this affects the way people respond to cues, with the exceptions outlined in the subsequent paragraph. In Austria, where populism has been politically more successful and where people have some experience with referendums at the national level, respondents for the most part do not react differently to cues than they do in Germany. This suggests that referendums as a heuristic tool are viewed very similarly by the Austrian and German publics, and that existing differences between the regimes do not matter much when all factors are equal.

Finally, we performed additional analyses to check the robustness of our results. As described in the research design, we created an additional scale from the arithmetic mean to measure populist attitudes. As shown in Figure A14 and A15 in the Online Appendix, the results remain substantively the same. Yet, we find that populists in Germany respond more strongly to congruence and neutrality with policy positions. However, as shown in Figures A16 to A21 in the Online Appendix, we find hardly any divergent results when grouping respondents’ populist attitudes by the median, terciles or quartiles, which confirms the robustness of our results. Furthermore, we checked whether the response to the treatments differs between individuals who support or oppose direct democracy in general.Footnote13 As shown in Figures A22 and A23 in the Online Appendix, we find few systematic and significant differences between supporters and opponents of direct democracy in the two countries, supporting our argument about the role of instrumental considerations in supporting the holding of referendums. In addition, we examined whether the effects of the treatments differ by the respective policy position, as shown in Figures A24 and A25. Last, we examined whether voters of populist parties (the FPÖ, the Left, and the AfD) differ in how they respond to the treatments. As shown in Figures A26, A27, and A28 in the Online Appendix, we find no substantial differences between voters and opponents of these populist parties.

5. Conclusion

We started out by asking why people support or oppose holding a referendum. Our specific interest lay in how people respond to cues as a key influence on the approval or disapproval of holding referendums. Our interest in cue-taking is based on the argument that in complex situations people rely on cognitive short-cuts and heuristics to make decisions. Moreover, we also drew on a rich literature suggesting a special affinity of populists for referendums because they empower people and curb elite decision-making. Thus, we formulated expectations that would identify differences between populists and non-populists when it came to cue-taking from, as we hypothesised, the favoured or non-favoured party, experts, and the public. We selected two countries, Austria and Germany, in which the Swiss referendum tradition often serves as a reference point. Both countries are politically and culturally similar but differ on the constitutional possibilities of referendums and the political success and longevity of radical populism in the political system. This allowed us to conduct a survey experiment that put the various attitudinal positions and behaviour choices systematically to the test.

We were able to demonstrate the complexity of factors involved in how citizens decide on whether they support or oppose holding a referendum. By doing so, we contribute to the literature beyond merely assessing the attitudes towards direct democracy in general, but rather how others’ opinions influence decision-making, and specifically the relationship between populism and direct democracy. Our object thus was to explain different sources of influence (i.e. cues) and to distinguish the way in which populists differ from non-populists in how they use them.

Using a conjoint experiment embedded in original surveys in Austria and Germany, we tested in a first step four hypotheses related to policies and cues that citizens rely on when deciding whether to support or oppose holding a referendum. In a second step, we tested three additional hypotheses in which we demonstrated interaction effects between populist attitudes and adherence to one of the cues: a favoured party, independent experts, and the public. While we found evidence for all our cue-based hypotheses, we found little differences between populist and non-populist citizens when it comes to differentiating between a normative and an instrumental support of referendums.

This has important implications for understanding citizens’ attitudes towards referendums and the relationship to populism: We expected populist citizens to have a strong normative baseline attitude in favour of this type of direct democratic instrument as it corresponds to the populism’s advocacy of people-centrism and the rejection of elite rule. However, we did not find evidence of this and conclude that populist and non-populist citizens alike support or reject holding referendums mainly for instrumental reasons. This diminishes the distinctiveness of populism and any normative claims associated with this in the debate on demand-side attitudes towards direct democracy.

Since the experimental treatment is to some extent based on hypothetical assumptions, we suppose that our results are more generalisable to countries with similar legal designs, essentially representative systems with direct democratic instruments in Western Europe. A differentiated treatment might be necessary for (1) countries with a unique tradition of direct democracy such as Switzerland (Kriesi, Citation2006) and (2) countries with different contextual factors such as Eastern European countries (Gherghina & Silagadze, Citation2021). However, the general similarity of findings between Austria and Germany also suggests that the idea of referendums and cue-taking implies that people have formed general opinions on a conceptual level but seem less affected by the differences in the political context.

Before suggesting the next steps for further research, we want to acknowledge that our study is not without empirical limitations. First, even though Hainmueller et al. (Citation2014) do not generally identify uncommon combinations in vignettes in survey experiments as an empirical problem, we cannot rule out the possibility that respondents were puzzled by unrealistic party positions that appeared due to the randomisation of the treatments’ parts and in consequence changed their response behaviour. Second, respondents were given 10 different tasks in which they had to choose one of two proposals. This means that respondents had to evaluate 20 different hypothetical settings. Bansak et al. (Citation2018) show that this number of tasks does not lead to less valid responses. However, as we were not able to record speeders and trackers in our survey experiment, both of these factors have to be considered when interpreting the results.

As our study suggests that the role of populism in attitudes towards direct democracy is less important than previously assumed, future research should examine further the question of populist citizens’ attitudes towards referendums and their cue-taking in conjunction with the dimensions of anti-elitism and people-centeredness. With populism having a much smaller than anticipated role in normative attitudes towards holding referendums, future research needs to focus on other factors. Furthermore, Trüdinger and Bächtiger (Citation2023), for example, suggest that populist citizens’ affirmation of referendums does not mean that they participate more in actual referendums. Instead, they find that it is primarily the political sophistication of the individual that has an impact on voter turnout in referendums. Such variables need to be taken more into account in future studies of the complex relationship between populism and direct democracy.

A related question for future research on the relationship between populism at the individual-level and referendums is the issue of acceptance of the results. Interestingly, Werner and Jacobs (Citation2021) find that populist citizens are more likely to accept the results of referendums even if it is not the outcome they voted for. More comprehensive analyses are needed to clarify which group of populist citizens participates in referendums and whether this has an impact on the acceptance of the results. Such research should also reexamine the relationship between direct democracy and trusting experts as well as what trustworthiness of experts means with regard to democratic decision-making (Hendriks et al., Citation2015). Lastly, it would be necessary to expand the universe of cases to capture different contextual factors, especially those associated with the success of populist parties.

In summary, we want to reiterate the three crucial insights with which this study adds to the literature: first, it underscores the importance of instrumental considerations in citizens’ decisions about direct democratic instruments; second, it demonstrates the different importance of cues depending on the source; and third, it challenges the often assumed ideological or normative difference in the way populists and non-populists approach referendums, other things being equal.

ccpo_a_2297507_sm3207.pdf

Download PDF (717.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank André Bächtiger, Achim Hildebrandt, Eva-Maria Trüdinger as well as the participants at the 11th Biennial Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on the European Union and the 2022 ECPR General Conference for their feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marco Fölsch

Marco Fölsch is a PhD Fellow at the Department of Political Science at the University of Salzburg. His research interests include aspects of political participation, political psychology and party competition.

Martin Dolezal

Martin Dolezal is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science at the University of Salzburg and at the Institute of Public Law and Political Science at the University of Graz. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. His research interests include political participation (both conventional and 'unconventional' forms) and party competition.

Reinhard Heinisch

Reinhard Heinisch is Professor of Comparative Austrian Politics at the University of Salzburg and chair of the department. His main research is centered on comparative populism, Euroscepticism, political parties, the radical right and democracy. His research has appeared in journals such as the Journal of Common Market Studies, Journal of European Political Research, Party Politics, West European Politics, Democratization, a.a. His latest book publications are The People and the Nation: Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics (Routledge 2019), Political Populism/Handbook (Nomos 2021), Politicizing Islam in Austria (Rutgers University Press 2024).

Carsten Wegscheider

Carsten Wegscheider is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Political Science at the University of Münster. His main area of research is comparative politics with an interest in democratization, populism, and political behavior. His research has been published among others in West European Politics, Politics and Governance, and Politische Vierteljahresschrift.

Annika Werner

Professor Annika Werner is Head of School at the School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University. She is an expert on comparative and European politics, with a special research focus on populism, party behaviour, representation and public attitudes in democracies. Her research has been published in journals such as the Journal of European Public Policy, Democratization, Party Politics, and Electoral Studies. Her book “International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament”, co-authored with Duncan McDonnell, is published with Hurst/Oxford University Press. Annika is Steering Group member of the Manifesto Project (MARPOR, former CMP) and of the ECPR Standing Group Extremism and Democracy.

Notes

1 The pre-registration is available at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/28qy5.

2 The conjoint experimental setup allows for 720 (8*3*3*10) possible combinations of characteristics in Austria and for 864 (8*3*3*12) combinations in Germany. We base our sample size on the German case at it poses a higher threshold. To avoid the empty cell problem in the analysis matrix, we determine the following: (1) To make sure that every such combination is evaluated at least 25 times, 21,600 combinations must be evaluated (864*25). (2) Every respondent evaluates 2 such possible combinations in every iteration of the experiment. Every respondent is confronted with 10 such iterations, meaning every respondent evaluates 20 random possible combinations of characteristics. (3) Thus, 21,600 combinations divided by 20 combinations per respondent, equals a minimum of 1,080 respondents. We round this up to 1,100.

3 See Table A1 and Figure A1 in the Online Appendix for descriptive statistics on the sample distributions of demographics and regions.

4 While some combinations might seem unlikely to respondents, we follow the recommendation of Hainmueller et al. (Citation2014) and do not exclude any of the possible combinations during randomization.

5 The specific question is: If you had to choose one of the two referendums, which one do you think should be held? ‘Referendum A’ (1) or ‘Referendum B’ (2)

6 The specific wording of the question is: How strongly would you agree with holding each referendum? Respondents indicate their preferences for each of the two referendums on an eleven-point scale ranging from ‘I fully reject the holding of this referendum’ (0) to ‘I fully support the holding of this referendum’ (10). As shown in the Online Appendix (Figures A9 and A10, Tables A9 to A12), the results of the main analyses for the binary and continuous dependent variables are substantially the same. We therefore only report the results for the binary dependent variable in the manuscript.

7 As shown by Bansak et al. (Citation2018), even with a significantly higher number of tasks, there are only limited increases in survey satisficing, which is why we follow established conventions with the number of 10 tasks. Figures A31 and A32 in the Online Appendix show that the effects for each attribute do not differ significantly depending on the particular task in the experiment.

8 Table A3 in the Online Appendix lists all variables and question wordings.

9 Figures A2 and A3 in the Online Appendix show the distributions of propensity to vote in Austria and Germany, respectively. As shown in Figure A11 in the Online Appendix, the results of the main analysis are robust when changing the threshold.

10 Figure A4 in the Online Appendix shows the distributions of support for the policies in Austria and Germany. Respondents that neither agree nor disagree with the statement are coded as neutral towards the respective policy.

11 As shown in Tables A9 to A12 in the Online Appendix, results remain substantially the same when estimating AMCEs with and without control variables. Furthermore, Figures A29 and A30 in the Online Appendix show that all levels occurred equally in the experiments.

12 Figures A7 and A8 in the Online Appendix show the distributions of the control variables for Austria and Germany.

13 To classify respondents as supporters or opponents of direct democracy, we measured support for direct democracy using the question ‘Citizens should have the final say in important political decisions by voting on them directly in referendums’. The distribution of support for direct democracy and the division into supporters and opponents is shown in Figure A6 in the Online Appendix.

References

- Bakker, B. N., Lelkes, Y., & Malka, A. (2020). Understanding partisan cue receptivity: Tests of predictions from the bounded rationality and expressive utility perspectives. The Journal of Politics, 82(3), 1061–1077. https://doi.org/10.1086/707616

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2018). The number of choice tasks and survey satisficing in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 26(1), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2017.40

- Bedock, C., & Pilet, J.-B. (2020). Enraged, engaged, or both? A study of the determinants of support for consultative vs. binding mini-publics. Representation, 1–21.

- Bedock, C., & Pilet, J.-B. (2021). Who supports citizens selected by lot to be the main policymakers? A study of French citizens. Government and Opposition, 56(3), 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.1

- Beiser-McGrath, L. F., Huber, R. A., Bernauer, T., & Koubi, V. (2022). Parliament, people or technocrats? Explaining mass public preferences on delegation of policymaking authority. Comparative Political Studies, 55(4), 527–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211024284

- Bickerton, C., & Accetti, C. I. (2017). Populism and technocracy: opposites or complements? Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 20(2), 186–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2014.995504

- Boecher, M., Zeigermann, U., Berker, L. E., & Jabra, D. (2022). Climate policy expertise in times of populism–knowledge strategies of the AfD regarding Germany’s climate package. Environmental Politics, 31(5), 820–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2022.2090537

- Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch's (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.111

- Bos, L., Schemer, C., Corbu, N., Hameleers, M., Andreadis, I., Schulz, A., Schmuck, D., Reinemann, C., & Fawzi, N. (2020). The effects of populism as a social identity frame on persuasion and mobilisation: Evidence from a 15-country experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 59(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12334

- Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Karp, J. A. (2007). Enraged or engaged? Preferences for direct citizen participation in affluent democracies. Political Research Quarterly, 60(3), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907304108

- Brubaker, R. (2017). Why populism? Theory and Society, 46(5), 357–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-017-9301-7

- Case, C., Eddy, C., Hemrajani, R., Howell, C., Lyons, D., Sung, Y.-H., & Connors, E. C. (2021). The effects of source cues and issue frames during COVID-19. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1–10.

- Castanho Silva, B., Andreadis, I., Anduiza, E., Blanuša, N., Corti, Y. M., Delfino, G., Rico, G., Ruth-Lovell, S. P., Spruyt, B., & Steenbergen, M. (2018). Public opinion surveys: A new scale. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism (pp. 150–177). Routledge.

- Coffé, H., & Michels, A. (2014). Education and support for representative, direct and stealth democracy. Electoral Studies, 35, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2014.03.006

- Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 808–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808

- Coleman, S. (2004). The effect of social conformity on collective voting behavior. Political Analysis, 12(1), 76–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpg015

- Dalton, R. J., Burklin, W. P., & Drummond, A. (2001). Public opinion and direct democracy. Journal of Democracy, 12(4), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2001.0066

- Darmofal, D. (2005). Elite cues and citizen disagreement with expert opinion. Political Research Quarterly, 58(3), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290505800302

- Dolezal, M., & Fölsch, M. (2021). Researching populism quantitatively: Indicators, proxy measures and data sets. In R. Heinisch, C. Holtz-Bacha, & O. Mazzoleni (Eds.), Political populism: Handbook of concepts, questions and strategies of research (Vol. 3, pp. 177–190). https://doi.org/10.5771/9783748907510-177

- Donovan, T., & Karp, J. A. (2006). Popular support for direct democracy. Party Politics, 12(5), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068806066793

- Dyck, J. J., & Baldassare, M. (2009). Process preferences and voting in direct democratic elections. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(3), 551–565. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfp027

- Eberl, J.-M., Huber, R. A., & Greussing, E. (2021). From populism to the “plandemic”: why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(sup1), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730

- Fernández-Vázquez, P., Lavezzolo, S., & Ramiro, L. (2023). The technocratic side of populist attitudes: evidence from the Spanish case. West European Politics, 46(1), 73–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2027116

- Franklin, M. N., & Lutz, G. (2020). Partisanship in the process of party choice. In H. Oscarsson & S. Holmberg (Eds.), Research handbook on political partisanship (pp. 308–327). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Gherghina, S., & Geissel, B. (2017). Linking democratic preferences and political participation: Evidence from Germany. Political Studies, 65(1_suppl), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716672224

- Gherghina, S., & Geissel, B. (2019). An alternative to representation: Explaining preferences for citizens as political decision-makers. Political Studies Review, 17(3), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807713

- Gherghina, S., & Geissel, B. (2020). Support for direct and deliberative models of democracy in the UK: understanding the difference. Political Research Exchange, 2(1), 1809474. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1809474

- Gherghina, S., & Pilet, J. B. (2021). Populist attitudes and direct democracy: A questionable relationship. Swiss Political Science Review, 27(2), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12451

- Gherghina, S., & Silagadze, N. (2021). Party cues and pre-campaign attitudes: Voting choice in referendums in Eastern Europe. Problems of Post-Communism, 70(6), 581–592.

- Gilens, M., & Murakawa, N. (2002). Elite cues and political decision-making. Research in Micropolitics, 6(1), 15–49.

- Grotz, F., & Lewandowsky, M. (2020). Promoting or controlling political decisions? Citizen preferences for direct-democratic institutions in Germany. German Politics, 29(2), 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2019.1583329

- Guasti, P., & Buštíková, L. (2020). A marriage of convenience: Responsive populists and responsible experts. Politics and Governance, 8(4), 468–472. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i4.3876

- Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024

- Hawkins, K. A., Carlin, R. E., Littvay, L., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis. Routledge.

- Heinisch, R., & Wegscheider, C. (2020). Disentangling how populism and radical host ideologies shape citizens’ conceptions of democratic decision-making. Politics and Governance, 8(3), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i3.2915

- Hendriks, F., Kienhues, D., & Bromme, R. (2015). Measuring laypeople’s trust in experts in a digital age: The Muenster Epistemic Trustworthiness Inventory (METI). PLoS One, 10(10), e0139309.

- Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how government should work. Cambridge University Press.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2006). How parties affect vote choice in European integration referendums. Party Politics, 12(5), 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068806066791

- Hobolt, S. B. (2007). Taking cues on Europe? Voter competence and party endorsements in referendums on European integration. European Journal of Political Research, 46(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00688.x

- Huber, R. A., Jankowski, M., & Wegscheider, C. (2023). Explaining populist attitudes: The impact of policy discontent and representation. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 64(1), 133–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-022-00422-6

- Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

- Jacobs, K., Akkerman, A., & Zaslove, A. (2018). The voice of populist people? Referendum preferences, practices and populist attitudes. Acta Politica, 53(4), 517–541. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0105-1

- Juen, C.-M., Jankowski, M., Huber, R. A., Frank, T., Maaß, L., & Tepe, M. (2021). Who wants COVID-19 vaccination to be compulsory? The impact of party cues, left-right ideology, and populism. Politics, 02633957211061999.

- Kam, C. D. (2005). Who toes the party line? Cues, values, and individual differences. Political Behavior, 27(2), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-005-1764-y

- Kriesi, H. (2006). Role of the political elite in Swiss direct-democratic votes. Party Politics, 12(5), 599–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068806066790

- Landwehr, C., & Harms, P. (2020). Preferences for referenda: Intrinsic or instrumental? Evidence from a survey experiment. Political Studies, 68(4), 875–894. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719879619

- Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2020). Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 28(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.30

- MacAllister, I., Johnston, R. J., Pattie, C. J., Tunstall, H., Dorling, D. F., & Rossiter, D. J. (2001). Class dealignment and the neighbourhood effect: Miller revisited. British Journal of Political Science, 31(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123401000035

- Malka, A., & Lelkes, Y. (2010). More than ideology: Conservative–liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Social Justice Research, 23(2), 156–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-010-0114-3

- Marien, S., & Kern, A. (2018). The winner takes it all: Revisiting the effect of direct democracy on citizens’ political support. Political Behavior, 40(4), 857–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9427-3

- Mede, N. G., & Schäfer, M. S. (2020). Science-related populism: Conceptualizing populist demands toward science. Public Understanding of Science, 29(5), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520924259

- Merkley, E. (2020). Anti-intellectualism, populism, and motivated resistance to expert consensus. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 24–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz053

- Mihelj, S., Kondor, K., & Štětka, V. (2022). Establishing trust in experts during a crisis: expert trustworthiness and media use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Science Communication, 44(3), 292–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221100558

- Mohrenberg, S., Huber, R. A., & Freyburg, T. (2021). Love at first sight? Populist attitudes and support for direct democracy. Party Politics, 27(3), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819868908

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2017). An ideational approach. Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Obradović, S., Power, S. A., & Sheehy-Skeffington, J. (2020). Understanding the psychological appeal of populism. Current Opinion in Psychology, 35, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.009

- Petersen, M. B., Skov, M., Serritzlew, S., & Ramsøy, T. (2013). Motivated reasoning and political parties: Evidence for increased processing in the face of party cues. Political Behavior, 35(4), 831–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9213-1

- Rojon, S., & Rijken, A. J. (2021). Referendums: increasingly unpopular among the ‘winners’ of modernization? Comparing public support for the use of referendums in Switzerland, The Netherlands, the UK, and Hungary. Comparative European Politics, 19(1), 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00222-5

- Rose, R., & Weßels, B. (2021). Do populist values or civic values drive support for referendums in Europe? European Journal of Political Research, 60(2), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12399

- Schuck, A. R., & De Vreese, C. H. (2015). Public support for referendums in Europe: A cross-national comparison in 21 countries. Electoral Studies, 38, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.02.012

- Steiner, N. D., & Landwehr, C. (2023). Learning the Brexit lesson? Shifting support for direct democracy in Germany in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum. British Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 757–765. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000382

- Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

- Thon, F. M., & Jucks, R. (2017). Believing in expertise: How authors’ credentials and language use influence the credibility of online health information. Health Communication, 32(7), 828–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1172296

- Trüdinger, E.-M., & Bächtiger, A. (2023). Attitudes vs. actions? Direct-democratic preferences and participation of populist citizens. West European Politics, 46(1), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2023435

- von Schoultz, Å, & Christensen, H. S. (2016). Ideals and actions: Do citizens’ patterns of political participation correspond to their conceptions of democracy? Government and Opposition, 51(2), 234–260. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.29

- Wegscheider, C., Rovira Kaltwasser, C., & Van Hauwaert, S. M. (2023). How citizens’ conceptions of democracy relate to positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. West European Politics, 46(7), 1235–1263. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2199376

- Werner, H. (2020). If I'll win it, I want it: The role of instrumental considerations in explaining public support for referendums. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12358

- Werner, H., & Jacobs, K. (2021). Are populists sore losers? Explaining populist citizens’ preferences for and reactions to referendums. British Journal of Political Science, 1–9.

- Wojcieszak, M. (2014). Preferences for political decision-making processes and issue publics. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(4), 917–939. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu039

- Wratil, C., & Wäckerle, J. (2023). Majority representation and legitimacy: Survey-experimental evidence from the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 62(1), 285–307. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12507