ABSTRACT

This article challenges the prima facie differences between the Scottish independence and pro-Brexit movements, drawing similarities based on shared promotion of nationalism, incorporation of populism, and policy radicalism challenging consensuses over austerity/immigration. The analysis tests four hypotheses: first, their respective supporters hold nationalist beliefs; second, their supporters adhere to different but relatively radical policy preferences (tested on three dimensions: economic, cultural, immigration); third, their supporters adhere with populism; and fourth, their supporters are cynical towards perceived experts. The article finds the expected nationalist support, as well as supporters of independence/Brexit holding more radical policy beliefs compared to anti-independence/anti-Brexit voters. Furthermore, the analysis reveals a clearer picture of anti-expert and anti-elite populism support for Brexit, with little evidence showing these being features of Scottish independence support. This leaves the conclusion of some voter-level similarities between supporters of both movements, but also differences in the levels of populism among their respective voters.

1. Introduction

To say that British politics was in a period of flux during the 2010–2020 period would perhaps be an understatement. The dominance of the centre-right Conservative Party was challenged by the radical right-wing challenger UKIP. The centre-left Labour Party was torn from its longstanding convergence by the internal uprising of a more radically left-wing faction, led by Jeremy Corbyn, to take the party’s leadership. The centuries-old union itself was challenged by the rise of Scottish nationalism, which has left lasting effects including the serious erosion of previous Labour Party dominance in Scotland. Perhaps overriding all of these, and dominating the UK’s politics in the latter part of that decade, was the UK’s departure from the European Union.

These were four especially prominent changes in UK politics during the 2010s, with complex causes which continue to be debated and effects which continue to unravel. But, if they were to be distilled down to a set of common characteristics and themes, perhaps the following can be specifically highlighted: populism, nationalism and radicalism.

The purpose of this article is to explore two of these prominent changes: the rise of Euroscepticism which led to the UK leaving the EU, and the rise of Scottish nationalism which continues to dominate politics in Scotland. This article will show how both are plausibly unified by the nationalist nature of their core ideologies, the presence of populism in their respective discourses, and both of them making more radical ideological appeals that challenge mainstream political parties and/or policy consensuses. The ultimate purpose of my analysis, though, is to quantitatively analyse the respective support of both these case studies (i.e. the individual-level), and explore the following research question: How similar is the support received by Scotland’s pro-independence movement versus for the UK’s pro-Brexit movement? The implication of finding similarity between supporters of both of these nationalisms, would place doubts in the claims of ‘Civic nationalism’ from the Scottish independence movement (Manley, Citation2022), as the attitudes of its supporters would be shown to be comparable with the (in large part) more ethnically-orientated pro-Brexit movement (Valluvan & Kalra, Citation2019). Likewise, evidence of voter-level differences between supporters of these two movements – despite sharing the characteristics of nationalism, populism and radicalism – would bolster the prima facie differences between them.

To begin with, I refine definitions of nationalism and populism, as these are much-discussed and debated concepts. Following this, my first section will discuss the respective policy radicalism of both British Euroscepticism and Scottish nationalism, and how each challenged established political parties/institutions. In brief, the pro-Brexit movement is radically anti-immigration, whereas the pro-independence movement takes more radical left-wing positions on economics. Overall, this discussion will also draw on tangible examples, raised by existing research, of nationalist, populist and radical discourse emanating from these two examples.

The purpose of this first section is to derive a set of commonalities between the pro-Brexit and Scottish pro-independence movements. From this, in the second section, I explain my quantitative analysis. To examine this question, I use British Election Study (BES) data to analyse and compare the roles of individual-level policy beliefs and populist sentiments in support of both these movements. With the specifics of my methodology set up here, I also clearly state a set of theoretical expectations in this section.

In the third part of this article, I then carry out the testing of these expectations, relating to voter-level policy preferences, nationalist sentiments, and populist anti-elite and anti-expert attitudes. More specifically, I expect the pro-Brexit and pro-independence voters to hold radical policy views (but on different dimensions: Brexit = immigration, independence = economics). I also expect to find support for both movements coming from nationalist voters, and from voters with elevated levels of anti-elite populist and anti-expert sentiments.

The analysis itself takes place on two levels. In the first, it compares pro-Brexit/independence voters with anti-Brexit/independence (’internal comparison’ between each movement’s voters) using multiple logistic regression analysis. For the second, I compare pro-Brexit voters with pro-independence voters (’external comparison’ across voters supporting each movement) using Forest plots to compare each group’s mean scores on nationalism, policy preferences, anti-elite populism and anti-expert views.

This leads me to conclude that support for both movements is similar in terms of nationalism and policy radicalism. However, their support is not similar in terms of anti-expert views or anti-elite populism.

2. Nationalism, populism, radicalism

The purpose of this section is to demonstrate the UK’s Eurosceptic and Scottish Nationalist movements’ respective relationships with the concepts of Nationalism, Populism and Radicalism. Although both demonstrate these three features in different ways, they are still fundamentally unified by having them as part of their ideology and discourse. Furthermore, an especially important function of this section is to define these three somewhat nebulous terms before they become the justification of my study.

Another thing to clarify is that both the pro-Brexit and Scotland’s pro-independence movements are prominently promoted by political parties. Specifically, before the 2016 referendum the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and after the 2016 referendum, the Conservative Party, have been the primary promoters of the pro-Brexit movement. Scottish independence is promoted by several political parties, but most prominently by the Scottish National Party (SNP) which currently holds a majority of Scotland’s seats in the UK’s parliament and has led the devolved government since 2007. My focus is on support for the wider movements. As a result, although looking at the parties is useful at times for refining their relationships with nationalism, populism and radical policy, I generally avoid looking at the parties in my analysis.

2.1. Nationalism

Nationalism has had a prolonged existence as a concept, and long-running prominence in the political world. Furthermore, it has come in many different guises, whether economic, ethnic-based, extreme in form, or taking on more ‘civic’ forms. These different appearances of nationalism have led to it being described as a ‘thin-centred ideology’, attaching itself to different host ideologies (such as conservatism, fascism, or liberalism) which have allowed for these different appearances (Freeden, Citation2017). Leaving these differing appearances aside, my focus is on the key underlying feature of nationalism: the promotion of ‘the nation’ and its perceived interests.

The research of Benedict Anderson (1983/Citation2006) refined three key characteristics of the nationalist’s conception of ‘the nation’. First, ‘the nation’ is limited: this makes the nation distinguishable from others; for example, British people being distinct from non-British people, or Scots from non-Scots. Second, ‘the nation’ is a community: those within the nation are organically part of this national community. This community is united by shared culture, customs, territory and history. Third, ‘the nation’ is sovereign: the nation can make its own decisions independently from the influence of others outside of it. The promotion of ‘the nation’ is the core feature of nationalism, with this nation recognised as distinct from others. To further this, nationalism distinguishes horizontally between ‘the nation’ and its people as an in-group, versus other nations and their people with different customs, cultures, territories and histories as an encompassing out-group (De Cleen et al., Citation2020).

Scottish nationalism has long identified itself as being a ‘Civic nationalist’ movement. The distinctness of ‘Civic nationalism’ is an area of dispute. Existing research has identified this as a more democratic face of nationalism, in contrast to the authoritarian nature of its opposing ‘Ethnic nationalism’ (Ignatieff, Citation1993). Additionally, this concept is argued to be a way for left-wing movements to challenge the ownership of patriotism by the political right (Viroli, Citation1995, pp. 19–20). Alternately, ‘Civic nationalism’ is potentially more of a self-sought moral distinction, designed and pursued only to allow a moral distinction between these movements in contrast to the connotations of racist ‘Ethnic nationalism’ and the brutal history of totalitarian fascist and communist nationalists (Tamir, Citation2019). The concept of ‘Civic nationalism’ has been important to acknowledge, given its connection with the more inclusive and generally left-wing Scottish nationalism. However, underneath this label, the same crucial concept remains: the promotion of this distinct, sovereign nation and its community of citizens.

Continuing with the theme of Scottish nationalism, I want to demonstrate how this is specifically expressed and promoted. Coinciding with the 2014 independence referendum, where the messages of Scottish nationalism were most clearly expressed, Ben Jackson (Citation2014) carried out research into the ideological bedrock of Scottish nationalism. The ideological starting point is founded upon the UK being an antiquated relic of imperialism, which through a lack of a ‘full-blooded bourgeois revolution’ maintains a pre-eminent aristocratic class that excludes the working classes from political significance. Against this obsolescent social and political setup, Scotland should free itself to pursue a separate future as a modern, European social democracy. Furthermore, a key catalysing factor has been the UK’s turn towards ‘neo-liberal’ economics since the 1980s – primarily propelled by English voters – and the Labour Party’s subsequent convergence leaves the left-wing, social democratic and anti-‘neo-liberal’ views of Scots outvoted and routinely unrepresented.

Taking a step back from the political thought at the bedrock of Scottish nationalism, there are themes here which link back to the concept of nationalism. Specifically, the proposition that Scotland is distinctly more left-wing and socially democratic than the rest of the UK, and therefore needs to separate itself to pursue this separate and distinctly Scottish ideological direction.

The most prominent political conduit for Scottish nationalism is the Scottish National Party (SNP), which has formed the executive of the devolved Scottish government since 2007. As I said before, I am not assuming the SNP and the Scottish nationalist movement are entirely the same in this article; however, looking at the SNP’s policies and pronouncements does help to flesh out the ideology of this movement. In 2007, the SNP sold independence to the public as ‘full control of Scottish over affairs’ and ‘would give Scotland the same rights and the same responsibilities as other nations’ (SNP, Citation2007). In further research on the ideology of Scottish nationalism, the key concept of sovereignty is highlighted from this language, which is described as ‘clearly based on the classical nationalist doctrine’ (Ichijo, Citation2009).

Bringing this back to Benedict Anderson’s (1983/Citation2006) characteristics of nationalism, the desire for separation from the UK is motivated by Scotland making its own decisions, independent from the influence of the UK and as a sovereign state. Scotland itself is a limited entity, with its own ideological path distinct from the wider UK’s direction. Finally, Scottish nationalism takes a fairly broad conception of the community, embracing the concept of ‘New Scots’ (i.e. those who have immigrated to Scotland) and their right to vote in the 2014 referendum (Hepburn, Citation2015). This demonstrates a liberal attitude towards immigration, combined with the identification as Scots promoting personal bonds with the nation itself.

Moving to the Eurosceptic pro-Brexit movement, a 2016 study suggested that Britain’s relationship with the EU was affected by feelings of nostalgia for political independence and separated sovereignty, with the EU standing in the way of reclaiming imperial ‘glory days’ (Grob-Fitzgibbon, Citation2016). Furthermore, previous research suggested that English nationalists perceive the EU as political elites who encroach upon their national sovereignty (Gifford, Citation2015). Additionally, Euroscepticism has been identified as ‘the most coherent expression of contemporary English nationalism today’ (Vines, Citation2014, p. 256). Of these three views of the Eurosceptic movement, the latter two have connected it with ‘English nationalism’. Although the pro-Brexit movement gained substantial support in all four nations of the UK in the 2016 referendum, including majority support in Wales, it may plausibly be seen as an English movement as England was the most pro-Brexit of the four nations. As a result, although English nationalism is not analogous to the pro-Brexit movement (thus, I do not refer to this movement as ‘English nationalism’ in this paper), it has been conflated with it in some existing research (Brown, Citation2017).

Looking further at the pro-Brexit movement, it is also right to remember what it constitutes ideologically. As a political endeavour, Brexit was about reclaiming power, previously held in London but later exercised by the European Union’s political institutions. The movement sought to ‘Take Back Control’ of these powers, including powers to control immigration, reinforcing the sovereignty of the UK’s parliament. Tracing this back to the three conceptions of ‘the nation’ (Anderson, 1983/Citation2006), the core intentions of the pro-Brexit movement align with the idea of ‘the nation’ being sovereign. By separating the UK from the European Union, the pro-Brexit movement’s intent was to enhance the UK’s ability to make decisions independently from the interference of EU member states. Furthermore, the intent to ‘Take Back Control’ constituted a national-chauvinist appeal, by presenting British political institutions as inherently superior to European ones – placing a clear distinction between Britain and Europe, which aligns with the idea of ‘the nation’ as a limited political entity and national community, with a distinct set of outsiders in the EU/Europe (Bell, Citation2021).

The intent of this article is not to say that the pro-Brexit and Scottish independence movements are entirely the same, but one of their similarities is nationalism. Both construct a distinct ‘nation’ and promote its people, sovereignty and political institutions. Against this nation, the pro-Brexit movement identifies the European Union and its members as the distinct ‘out-group’ undermining UK national sovereignty. In the case of the Scottish independence movement, the ‘out-group’ is the UK (primarily England) which has supported ‘neo-liberal’ economic policies and separation from the EU, restricting the ability of Scotland to be a modern, socially democratic European state (Jackson, Citation2014).

2.2. Populism

An especially prominent definition of the famously nebulous concept of populism is the one promoted in particular by Cas Mudde (Citation2004, Citation2007, Citation2010). Populist political actors suggest that they and they alone understand and will truly promote the ‘general will’ of ‘the people’. Populism casts ‘the people’ as being in an antagonistic relationship with ‘the elites’, which may consist of wealthy citizens, large corporations, media organisations and established political parties/institutions. Additionally, this view defines populism as a ‘thin-centred’ ideology, in which the key feature is the appeal to ‘the people’ in opposition to ‘the corrupt elite’. Instances of populism may then attach themselves to broader ideologies. For example, populism may be attached to nativism and subsequently propose anti-immigration and welfare chauvinist policies, with the potential for this to also incorporate Euroscepticism in the case of UKIP in the UK (Ennser-Jedenastik, Citation2017). Alternately, populism may attach to socialist ideology to propose greater state involvement in the economy, higher taxes on wealth and businesses, and increased spending on welfare policies (March & Mudde, Citation2005), such as Podemos in Spain (Ramiro & Gomez, Citation2016).

Populism and nationalism have a degree of similarity. Both populism and nationalism have been described in existing literature as ‘thin-centred’ ideologies, with a narrow ‘nodal point’: ‘the nation’ for nationalism, and ‘the people’ for populism. Both have also attached themselves to broader host ideologies. In the case of the pro-Brexit movement, its frequently-expressed desire to limit immigration suggests it has incorporated nativist attitudes, whereas the Scottish independence movement has generally embraced left-wing social democratic ideology. Furthermore, both distinguish an ‘out-group’ from their ‘nodal point’: for nationalism, the ‘out-group’ consists of non-members of ‘the nation’, whereas for populism this is ‘elites’.

Populism is not necessarily a core feature of the Scottish independence movement’s discourse or ideology. Populist discourse is instead more of an option for this movement given the closeness in meaning between populism’s ‘the people’ and nationalism’s ‘the nation’. What makes populism an even clearer option is the potential to target ‘elites’ among the political in-stitutions/classes of the state from which this movement desires separation. As a result, existing research suggests the potential for this movement to set the regional nation (in this case, Scotland) against the host state’s political elites (Massetti, Citation2018) – in this case, the UK and its political heart at Westminster. Expanding on this point, an analysis of the appeals made by the pro-independence campaign in 2014 identified a number of populist appeals:

‘This referendum isn’t about politicians. […] it’s about the people of Scotland’. This statement, from the Yes to Independence campaign’s leader and Scottish First Minister (2007–2014) Alex Salmond, invokes ‘the people of Scotland’ against politicians and shows a ‘populist, anti-elitist streak’ (McAnulla & Crines, Citation2017, p. 480). By itself, the ‘people-centredness’ of this statement, calling upon ‘the people’ is not considered enough to justify the populist label, according to existing knowledge on this concept (March, Citation2017). However, the theme Salmond added to this was opposition towards established politics. Salmond, in his leading role in the 2014 pro-independence campaign, ‘took advantage of the wider context of UK politics to develop a popular case for independence’ (McAnulla & Crines, Citation2017, p. 425).

Scotland’s pro-independence movement promotes a critique of Westminster politicians and institutions. For example, West-minster politicians and institutions are held responsible for the regional inequalities within the UK, which then catalyse this call for Scotland’s separation (McAnulla & Crines, Citation2017, p. 482). Furthermore, this movement draws a nationalist distinction by saying Westminster does not understand ‘the Scottish character’ according to Salmond (McAnulla & Crines, Citation2017, p. 483). Westminster is also positioned as politically different and threatening to Scotland via policies of austerity, continuation/renewal of the UK’s nuclear weapons arsenal, suggestions of privatisation of the NHS, and the prominence of the Conservative Party leading UK governments relative to their poor electoral performances in Scotland (McAnulla & Crines, Citation2017, p. 484). Additionally, at the partisan level existing research has used the term ‘Populist Nationalism’ to describe the Scottish National Party, identifying the party’s argument favouring distancing Scotland from an ‘exploitative English-dominated Britain’ (Eatwell & Goodwin, Citation2018, p. 80). Cumulatively, there is strong evidence supporting the notion of Scotland’s pro-independence movement using populism as part of its appeal.

Looking at the pro-Brexit movement’s populism, previous research has evidenced the prevalence of populist sentiments at the voter level among pro-Brexit voters (Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019, p. 392). This support for the pro-Brexit movement from populist voters by itself implies a positive link between this thin-centred ideology and sympathy for secession from the EU. However, more explicit evidence of populism within this movement is evident when reviewing the rhetoric of some of its prime advocates. Nigel Farage – perhaps the most prominent of the consistently pro-Brexit voices in UK politics – identified a populist ‘elites’ group as including a ‘deep-state’ of ‘establishment’ civil servants working to subvert the UK’s secession from the EU (Eatwell & Goodwin, Citation2018, p. 45). Additionally, the language of opposition towards ‘Brussels bureaucrats’ and an out-of-touch pro-EU political class, as well as the notion of a ‘gravy train’ of European Parliament politicians wasting tax-payers’ money are all features identified in pro-Brexit talking points from existing discourse analysis research (Ruzza & Pejovic, Citation2021).

One interesting aspect of the pro-Brexit movement was demonstrated by the then Justice Secretary Michael Gove in one of the 2016 referendum’s televised debates. Gove publicly stated that ‘people in this country have had enough of experts’ (Clarke & Newman, Citation2017). Populism does tend to draw upon a dichotomy of power: ‘the people’ have little, and are subject to the accumulated power and influence of ‘the elite’. However, this anti-expert sentiment perhaps imbues the dichotomy of populism with an intellectual dynamic rather than one of power. Potentially, the pro-Brexit campaign drew support – publicly urged by Michael Gove – from people whose opposition to ‘elites’ stretches to include perceived experts. The Brexit campaign itself was quick to counter the views of these experts in economic and political circles, lambasting their anti-Brexit contributions as ‘Project Fear’ (Clarke & Newman, Citation2017). Similarly, experts raised critical questions against the pro-independence movement in Scotland in 2014, with the anti-independence campaign also being criticised as another instance of ‘Project Fear’ (McAnulla & Crines, Citation2017; Black et al., Citation2023). This common anti-expert sentiment underlying both movements is another notion that I explore in my analysis later in this paper.

In summary, both the pro-independence movement in Scotland, and the pro-Brexit movement in the wider UK, plausibly draw upon populism as part of their appeal. However, although to an extent this may be a feature these two movements have in common, the nature of their ‘outgroup’ – their opposition – is embodied by different institutions. For the pro-independence movement, this is ‘Westminster’ – the term embodying the political institutions of the UK which this movement desires separation from. Whereas, for the pro-Brexit movement this is the EU – perhaps referred to as Brussels, and again embodying the political institutions this movement promotes separation from.

2.3. Radicalism

The radicalism of both the pro-Brexit and pro-independence movements across the UK and Scotland, respectively, is a little more nuanced. It is important to clarify two things: first, both movements are radical, but these radical positions are on different policy dimensions; and second, the radicalism of both movements is relative to the political norms of their context. This latter point is something previously emphasised when identifying examples of radically left-wing political actors (Goodger, Citation2022). Additionally, the role of context is apparent from the ‘pathological normalcy’ thesis, identified by Cas Mudde (Citation2010) to define the radical right. These political actors are distinguished by more hardline and dogmatic interpretations of mainstream right-wing policy, meaning that on this side of the political spectrum as well the notion of radicalism starts from a context of what is considered to be mainstream policy.

The pro-Brexit campaign in the UK’s 2016 EU referendum was a broad movement and drew support from across the political spectrum. The analysis of Ford and Goodwin (Citation2014), for example, showed how the UK Independence Party (UKIP) – the longtime single-issue political vehicle of the pro-Brexit movement – drew substantial support from Labour Party voters (Ford & Goodwin, Citation2014). However, many well-known pro-Brexit politicians achieved their prominence through political parties on the right – most frequently the Conservative Party or UKIP – and support for Brexit has been more commonly found among right-wing voters in existing research (Henderson et al., Citation2017). Thanks to both of these factors, the pro-Brexit movement is generally a movement of the political right in the UK.

The way that the right-wing pro-Brexit movement becomes a radical feature in UK politics is by its ideological challenge towards converged parties, and in particular the converged right. This challenge was perhaps most publicly seen with the bulk of the Conservative Party during the 2016 EU membership referendum, including the party leader and Prime Minister David Cameron and all three of the UK’s other ‘Great Offices of State’,Footnote1 supporting the campaign to remain in the EU. Relative to this more moderate strain in the Conservative Party, which unified behind David Cameron’s pragmatic ‘remain and reform’ case opposing secession, the pro-Brexit movement is the more radical challenger. Whereas 25 members of the 2016 Conservative cabinet endorsed the pro-Remain campaign, only 5 cabinet members backed the campaign to leave the EU. Those five were joined by many backbench MPs who had long been identified as being on the right of the party; for example, Jacob Rees-Mogg, John Hayes, John Redwood and Peter Bone.

The radicalism of the pro-Brexit movement is also evident in policy terms. The 2016 EU referendum had the ‘remain and reform’ argument alongside the general appeal towards the status quo of EU membership. Pitched against this was the pro-Brexit movement’s policy of complete secession from this decades-old political and economic union – a more radical proposal, relative to the status quo and prospects of reforming the EU from within. Looking at another example of policy radicalism, opposition towards immigration is a prominent feature of right-wing radicalism (Mudde, Citation2007). This is also true of the pro-Brexit movement in 2016. Part of the pro-Brexit movement’s appeal in 2016 was to control the UK’s borders and impose a points-based immigration system, with this nativism illustrated through the ‘Breaking Point: The EU has failed us all’ billboard (Eatwell & Goodwin, Citation2018, p. 35). Previous research has also identified anti-immigration sentiment to have been significantly associated with support for the pro-Brexit movement (Goodwin & Milazzo, Citation2017).

In general, the pro-Brexit movement has been a right-wing phenomenon, promoted most consistently by the radical right UK Independence Party as well as many of the more hard-right members of the Conservative Party, and commonly aligned with strongly nativist policies and rhetoric. However, whereas the pro-Brexit movement has generally arisen from the right of British politics in recent years, the pro-independence movement in Scotland has predominantly arisen from the left.

Looking now to Scotland and its pro-independence movement, the SNP made their critical electoral breakthroughs in the first half of the 2010s. Throughout that decade, the UK was administered by Conservative-led governments which promoted policies of fiscal restraint. During the second half of the 2010s, these policies were most stridently challenged by the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn, which broke from the party’s long-standing convergence to pursue a more radically left-wing ideology (Goodger, Citation2022). However, in the first half of this decade, it was the SNP which sought to make the anti-austerity case and stand up to the pro-austerity political consensus at Westminster (Massetti, Citation2018).

In contrast to the Corbyn-led Labour Party, the SNP does not prioritise their anti-austerity economic policy. First and foremost is its advocacy for Scotland’s separation from the UK. Therefore, the SNP is a left-wing separatist party, and similarly draws on some of the European radical left’s strident opposition towards austerity policies. However, given the SNP’s focus on separation from the UK, it should not be counted among Europe’s radical left.

Nevertheless, the SNP has embraced some of the economic messages of Europe’s radical left. The undercurrent of austerity policies, which fomented rhetoric of NHS privatisation and a need to separate to make more progressive policy choices, were important to the breakthrough of the pro-independence movement in the early 2010s (Beland & Lecours, Citation2021). Additionally, an element of the pro-Brexit movement’s radicalism was its commitment to secession from the EU, rejecting the status quo and the ‘remain and reform’ case. The 2014 Scottish independence referendum featured a comparable argument to ‘remain and reform’ when Westminster leaders agreed on a set of future powers to be devolved to Scotland should it choose to remain in the UK – what later became known as ‘The Vow’ and was formalised first as the Smith Commission in late 2014, and then as the Scotland Act of 2016. Like the pro-Brexit movement’s more radical positioning in 2016, the pro-independence movement in 2014 was taking a relatively more radical position (versus the status quo) by also advocating for outright secession instead.

This sub-section has focused on the radicalism of the pro-Brexit and pro-Scottish independence movements. To clarify, neither movement is especially radical as a consequence of their respective core aims: separation from the EU/UK. Instead, the pro-Brexit movement’s radicalism arises from its stridently anti-immigration appeals, which have drawn substantial support from strongly anti-immigration voters. In contrast to the right-wing and, specifically, migrant-exclusionary radicalism emanating from much of the pro-Brexit movement, there is a different radicalism from the pro-independence movement in Scotland. Scotland’s pro-independence movement emanates more inclusionary policy on immigration, but has also made radical policy appeals. However, this movement’s radicalism has been in relation to economics instead, with pursuit of a strongly anti-austerity agenda.

The salient point is that policy has an important role in the appeal of both these movements, given how they have both promoted radical ideological positions (on different policy dimensions). Crucially, this raises policy as another area where support for both movements may be understood, especially as voters’ policy preferences have long been considered significantly predictive of political support (Downs, Citation1957).

Overall, the pro-Brexit movement and Scotland’s pro-independence movement have similarly imbued nationalism, similarly made populist appeals, and similarly occurred as more radical political movements challenging mainstream political parties and institutions. This leaves three critical commonalities uniting both of these movements, which are themselves unified by their fundamental ideological appeals to separate from long-standing political and economic unions. I take these three commonalities forward to explore their roles in support for both of these movements: nationalist feelings, populist sentiments and policy beliefs at the voter level.

3. Methodology and expectations

Progressing from the three similarities, I ask the critical question of my research once again: How similar is the support received by Scotland’s pro-independence movement versus for the UK’s pro-Brexit movement?

The primary variables through which I analyse this question are as follows: policy preferences (relating to economic, cultural and immigration policy), nationalist sentiments, anti-expert attitudes and anti-elite populist attitudes. I examine this with data from the British Election Study; specifically, their rolling panel data.

3.1. Quantitative data: British Election Study

The starting point for my empirical analysis is to identify pro-independence voters in Scotland and pro-Brexit voters across the UK. From there, I identify and compare their respective support based on policy, populism and nationalism. The British Election Study provides measures of support for both of these movements (Fieldhouse et al., Citation2023). The ‘scotReferendumIntention’Footnote2 and the ‘euRefVote’.Footnote3 Both of these questions allow me to measure and then understand the more recent support both these movements receive.

As I have said, I analyse and compare support for both of these movements on the basis of voters’ nationalist attitudes, their policy preferences, and their populist sentiments (anti-elite and anti-expert). The BES provides measures relating to all of these explanatory variables. All of the BES’s measures used for the analysis are included under Appendix 1, which details the specific wording of these questions and the answers that respondents were able to provide.

In terms of policy, I look at this based on a comprehensive set of different issues: economics (tax and spending), cultural issues (e.g. abortion, law and order, LGBT + rights) and immigration (treatment of immigrants, attitudes towards immigration). The BES provides measures of economic policy views via its five-item ‘Values1’ battery, provided as a set of statements to which respondents are given a five-level Likert response scale. The ‘Values2’ battery provides an equivalent set of five statement-based Likert-scaled measures relating to cultural policy. Finally, the BES provides three measures of migration policy views: ‘immigEcon’ asking for appraisals of the impact of immigration on the economy, ‘immigCultural’ relating to impacts on national culture, and ‘immigGrid’ – a 0–10 self-placement question relating to personal views regarding allowing or restricting immigration. I address all scales of responses appropriately to make sure all answers coherently line up with a particular side of the policy dimension (e.g. a respondent supporting traditional values from one question and obedience to authority on another will have both these views counted as being culturally-conservative).

The BES’s ‘subnatAttach’ battery – asked only in wave 19 (December 2019) – asked six questions relating to sub-national (English/Scottish/Welsh) attachments within the UK. For example, ‘When someone criticizes [country], I don’t take it as a personal insult’. Respondents indicate their agreement/disagreement with a true or false answer to these six items.

Finally, the BES’s provides measures of populist sentiments in their ‘Populism’ battery – a series of five statements with a Likert scale of possible responses. The broad themes of these prompt beliefs regarding popular sovereignty, political compromises, and differences between politicians and ‘the people’. This set of populism-based questions has found use in existing research (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; van Hauwert & van Kessel, Citation2018). Populism is predominantly about cynicism or opposition towards ‘elites’. A further angle which I also explore is the notion of anti-expert sentiments. Criticism of perceived expertise was a feature of the pro-Brexit campaign in 2016, so may be a notable feature of support for this movement. I also compare the extent this is present in the pro-independence movement. The BES includes a measure for anti-expert sentiments under the ‘efficacyGrid’, entitled ‘antiIntellectual’, and is answered with another five-level Likert scale.

Accompanying my analysis is a series of control variables covering factors including education levels, respondent gender, age group, ethnicity and identification with a political party.

All of these measures appear in wave 19 of the BES’s panel data. This wave occurred in mid-2020, providing fairly recent data that provides relevant insights into the motivations behind support for the pro-Brexit and pro-independence movements. These measures do also appear in later BES waves but with diminished responses. To examine Brexit/Independence support from a larger sample of respondents, I have opted for data from wave 19. The exception is the populism data, which did not feature in wave 19. To preserve as many responses as possible in my analysis, I have drawn populism responses from a wave with more responses – wave 10 (Nov./Dec. 2016). Also not in wave 19 was the anti-expert question, which I have subsequently drawn from wave 17, which occurred only a month prior (November 2019).

3.2. Theoretical expectations

The theoretical expectations I have derived from the earlier discussion reflect both the identified similarities and differences between these two political movements. They are as follows:

H1: Firstly, in terms of policy preferences, I expect supporters of Scottish independence will on average hold more economically left-wing views, culturally-liberal views, and migrant-inclusive views, relative to pro-Brexit voters. This would reflect the differing ideological background of Scotland’s pro-independence movement versus the pro-Brexit movement, in particular with the pro-independence movement making great efforts to proclaim ‘civic nationalism’.

H2: In contrast to the policy differences, I have identified populist appeals as a similarity between these two movements. As a result, I expect that supporters of Scottish independence and of Brexit will have populist attitudes. I also compare the levels of populism among these voters with those who hold the opposing views: opposition to Scottish independence/Brexit.

H3: Thirdly, as an extension of the anti-elite nature of populism, I also consider the role of anti-expert sentiments in support for both of these movements. I expect that supporters of Scottish independence and of Brexit will hold attitudes which are sceptical of the views of experts. Again, I compare the anti-expert sentiments of these respondents with those of anti-independence and anti-Brexit voters.

H4: Finally, given the common elements of nationalism in the ideologies of both movements, I expect that supporters of Scottish independence and of Brexit will have significantly higher nationalist sentiments compared to anti-independence and anti-Brexit voters.

4. Analysis

My analysis comes about at two levels. First, an internal comparison: how does the pro-independence/pro-Brexit movement’s support compare with anti-independence/anti-Brexit voters? Second, I compare externally: how do pro-independence voters compare to pro-Brexit voters? In total, I have pursued three different means of analysing support for both of these movements here: logistic regression analysis for the internal comparison and Forest plots demonstrating the external comparison.

4.1. Internal comparison

The purpose of my analysis here is to explore how supporters of Brexit and Scottish independence differ from their respective counterparts – anti-Brexit and anti-independence voters – on the variables of policy preferences (economic, cultural, migration), anti-expert and anti-elite populist feelings and nationalist sentiments. To do this, I have carried out multiple logistic regression. Recorded under is the regression of pro-Brexit respondents, and under is the same model with the pro-independence respondents.

Table 1. Logistic model of policy, populism and anti-expert effects on support for Brexit.

Table 2. Logistic model of policy, populism, nationalism and anti-expert effects on support for Scottish independence.

To clarify, in both models the ‘Nationalism Scale’ represents averaged responses to the six ‘subnatAttach’ questions, ‘Econ Scale’ represents the averaged response to the five economics-related questions in the ‘Values1’ battery, with higher values reflecting more right-wing responses. Equally, ‘Cultural Scale’ reflects the five ‘Values2’ measures (higher values = more conservative views), ‘Immig Scale’ the three migration policy questions (higher values = migrant-inclusive views) and ‘Populism Scale’ the five measures from the ‘Populism’ battery (higher values = greater populism). The ‘anti-IntellectualW17’ variable is from a single measure, with higher values demonstrating more cynical attitudes towards perceived experts.

shows that elevated levels of populist sentiments are significantly associated with a greater chance of supporting Brexit, as is holding anti-expert views. Additionally, holding nationalist attitudes is associated with greater support for leaving the EU in , with this variable’s coefficient also reaching statistical significance. Finally, support for Brexit is significantly associated with holding more economically right-wing policy preferences, compared to Brexit opponents. Furthermore, the negative coefficient for the migration policy variable shows that holding more migrant-inclusive views is associated with a lower likelihood of supporting Brexit.

Looking back at my hypotheses, I expected populism to be a significant driver of support for Brexit – something I have found evidence for in . Moreover, the anti-expert coefficient does suggest that this movement attracted support from voters who had perhaps (in the words of Michael Gove) ‘had enough of experts’. Furthermore, the nationalism variable’s significant positive coefficient conforms with my expectation. Therefore, has provided support for H2, H3 and H4 – relating to the populism, anti-expert and nationalism coefficients, respectively. I shall return to H1 later, as this relates to the external comparison across these two nationalist movements regarding the policy variables; however, at this point my findings from the policy variables fit with the broadly left-wing pro-independence movement and the generally right-wing pro-Brexit movement.

provides equivalent analysis with pro-/anti-independence voters in Scotland. I have had to present this as three simpler models. Which has the disadvantage of not comparing nationalism, populism and policy effects together. However, I found that including these variables in one model left too few respondents, leading me to the approach I have taken in . shows the effects of nationalism (with controls) in column 1, of anti-expert and anti-elite populism in column 2 and preferences on the three policy dimensions in column 3.

The Scottish independence model shows that holding more economically right-wing, culturally-conservative and migrant-exclusive views were all significantly associated with lower likelihood of supporting Scottish independence (compared with anti-independence voters). This is plausible, considering the generally left-wing and liberal nature of this movement, which made efforts to characterise itself as being an example of ‘civic nationalism’. The ‘Populism Scale’ coefficient is not statistically in , suggesting populism is not associated with being either pro- or anti-independence. Meanwhile, the statistically significant negative anti-intellectual coefficient suggests holding anti-expert views is associated more with opposition towards independence than support for it. Finally, the ‘Nationalism Scale’ coefficient is positive and significant, pointing to higher levels of nationalist sentiment among pro-independence voters than those opposed to separation from the UK.

Bringing this back to the hypotheses, I do not find evidence supporting H2, and find evidence which runs completely counter to H3 with anti-expert sentiment less a feature of in-dependence support compared to its opponents. However, I did find support for H4, with pro-independence voting significantly associated with holding more nationalist sentiments.

4.2. External comparison

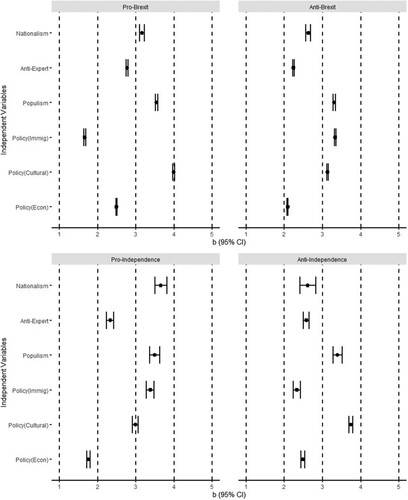

The external comparison refers to comparing support for Brexit with support for Scottish independence, rather than comparing with the respective counterparts of each of these movements. Below, under , is a Forest plot demonstrating the patterns of support for Brexit (top) versus for Scottish independence (bottom). Like the logistic models just discussed, the independence plot is also completed with wave 19 data, with the exception of the populism and anti-intellectual variables (waves 10 and 17, respectively). Under Appendix 2, I have also included a table that states the precise numerical means (with .95 CIs) that underpin the graphical summary in .

Figure 1. Forest plot of mean Brexit/independence support from policy, populism and anti-expert variables (with .95 CIs).

Looking down the left side through , I can compare the supporters of Brexit with the supporters of Scottish independence. In brief, it shows that supporters of Scottish independence on average hold more nationalist attitudes than supporters of Brexit. also shows pro-Brexit voters to be more anti-expert than Scottish independence supporters. Finally, shows both groups of voters to be similarly populist; however, not clearly distinguished from anti-Brexit or anti-independence voters on this variable either.

is especially important for my test of H1, under which I expected pro-Brexit and pro-independence voters to hold different views on the three policy dimensions. provides a chance to test this. It shows that pro-independence voters are more migrant-inclusive than pro-Brexit voters – an expected conclusion given the contrast between the pro-independence movement’s commitments towards ‘civic nationalism’ versus the anti-immigration rhetoric that notably emanated from elements of the pro-Brexit movement. On cultural policy, pro-independence voters on average hold views that are more liberal compared to the pro-Brexit voters. Finally, shows that pro-independence voters are substantially more left-wing on economics compared to pro-Brexit voters.

Put together, these policy-based results lend support to H1, with considerable differences in mean scores on these three dimensions from the pro-Brexit and pro-independence voters. Also as expected, the pro-independence group hold more economically left, culturally-liberal and migrant-inclusive views on average compared to pro-Brexit voters.

Expanding on this, I showed earlier how radicalism is one of the unifying factors of these two movements. They challenge mainstream political views in terms of policy: the pro-independence movement primarily by opposition towards austerity, and the pro-Brexit movement mainly by opposition towards immigration. Looking again at , what does this show about the respective radicalism of these two movements? Yes, they differ in terms of the specific policies which each of their supporters align with, but perhaps their supporters are unified by being positioned in more radical positions on each dimension.

Looking at the ‘Policy(Immig)’ row, the pro-Brexit voters have on average much lower scores on this dimension, in comparison with all other voting groups. Furthermore, under ‘Policy(Cultural)’ these voters also on average hold more culturally-conservative views than all of the other voting groups. Most importantly, it is the anti-immigration views that stand out most from this group, with its voters well away to the fringes of this dimension. This provides initial evidence for policy radicalism among supporters of one of these two movements. Looking at the other movement – pro-independence – and its supporters in the bottom-left plot, the ‘Policy(Econ)’ line shows that voters who support Scottish independence on average hold views on this dimension which are radically to the left – further left than all other voting groups. Consequently, although supporters of Brexit and Scottish independence have very different policy preferences (as expected), they are united by a tendency towards radical policy beliefs.

5. Discussion and conclusions

At the outset of this article, my intent was to analyse and compare support for two movements which rose to particular prominence in the UK’s political context in the 2010s. Both are defined by presenting themselves as radicals on policy, albeit in very different areas (pro-independence = economics, pro-Brexit = immigration). Both are defined by their tendency to make populist appeals, calling on ‘ordinary people’ to oppose ‘political elites’. Furthermore, both are defined by their nationalism, drawing strict lines around their respective nations and opposing the influence of polities outside of this: the UK government at Westminster and the European Union’s political institutions. Although these two movements are unified by these three elements – radicalism, populism and nationalism – I have acknowledged and tested the plausible differences between their supporters in terms of their policy preferences. I identified clear evidence that supporters of Scottish independence on average hold radically left-wing economic policy beliefs, and supporters of Brexit on average hold culturally-conservative and radically migrant-exclusive policy preferences – findings which supported H1. Therefore, while both these movements are adhered to by voters with substantially different policy beliefs, both are supported by voters with radical policy views.

I also found further evidence of differences between the pro-Brexit and pro-independence movements; however, this time running contrary to my expectations. Firstly, I had expected both movements to similarly draw support from voters with high levels of populist sentiments. Although I found evidence of significant support for Brexit from populist voters, I did not find evidence of this in support for Scottish independence (H2). Secondly, I analysed the role of anti-expert sentiments and expected to find significant support for both movements from anti-expert voters. However, although present in support for Brexit, I did not find this among Scottish independence support (H3).

Finally, after testing nationalist sentiments and how they were tied to supporters of Brexit/independence H4, I ultimately found that this was indeed a unifying factor of these two movements at the voter-level. Specifically, supporters of the UK leaving the EU, and of Scotland leaving the UK, both held significantly more nationalist sentiments, compared to opponents of each movement. Therefore, my findings from the nationalism variable ultimately conformed with my expectations H4.

In short, I expected to find a degree of similarity between the pro-Brexit movement and the pro-independence movement at the individual level, especially considering the shared characteristics of these two movements. I ultimately found a mixed picture: both supported by nationalists and policy radicals, but of the two only Brexit supported by anti-expert and anti-elite populist respondents. Previous research has not necessarily made such a direct analysis of supporters for both of these movements together; however, there is existing evidence of support for Scottish independence from economically left-wing voters (Niedzwiedz & Kandlik-Eltanani, Citation2014). Research that pointed out the independence movement’s populism also picked up upon its anti-austerity nature, and how this was plausibly a major element of the SNP’s appeal when it made its electoral breakthrough at Westminster in 2015 (Massetti, Citation2018). The fact the party’s support then slumped in the 2017 UK election may be due to the then more radically left-wing Corbyn-led Labour Party picking up support from anti-austerity voters, with the SNP no longer the sole option for these voters in Scotland (Massetti, Citation2018). Meanwhile, in relation to pro-Brexit voters, mine is not the first study to have identified its support among those holding nativist views and anti-elite sentiments (Iakhnis et al., Citation2018).

The differences between the pro-independence movement from the pro-Brexit movement have been evident for a fairly long time when looking at the party-/campaign-level. The more liberal and inclusive appeals of prominent politicians like Nicola Sturgeon and Humza Yousaf are prominent examples of this, and stand in stark contrast to the more exclusive language around migration from the likes of Nigel Farage. However, what this article has contributed is a view of the individual-level. Overall, that demonstrates a deeper comparison between these two movements, with this permeating the face-level ideologies and appeals by also gauging the views of their respective voters. Finally, the wider contribution my analysis makes is to bolster the concept of ‘Civic Nationalism’, which has had its distinction from ethnic nationalism disputed (Tamir, Citation2019), and to bolster this concept among voters rather than just at the party-/campaign-level.

My analysis has not been without impediments. Ideally, enough data – especially from the ‘subnatAttach’ questions – would have been available to allow me to include the nationalism scale alongside populism, anti-expert views, and policy views in a single model. Although I have worked to mitigate this in , this has hindered my test of all of these variables and how far they may explain the pro-independence movement’s support in Scotland.

Moreover, whereas the pro-Brexit movement has received a great deal of research attention further research on Scotland’s independence movement may be fruitful. For example, I have found strong evidence of leftist, liberal, and inclusive views among this movement’s adherents; however, this may be a result of the left-wing, liberal, and inclusive appeals made by the likes of Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon and other prominent pro-independence figures during the SNP’s tenure at the forefront of Scottish politics. By reaching further back, a transition point may be identifiable where the pro-independence movement shifted towards these policy stances relatively recently – perhaps motivated by maximising support among disillusioned Labour voters in Scotland. Altogether, the pro-independence movement is an area that warrants further research, especially as it remains a highly relevant and electorally persistent political force in the UK.

Author Biography.docx

Download MS Word (12.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Edward Goodger

Edward Goodger is currently a Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Manchester. He received his PhD from Durham University in 2022 for a thesis entitled ‘Policy and Populism: Explaining Support for Radical Left Political Actors in Contemporary Western Democracies’ and is an alumnus of the ‘Centre for Institutions and Political Behaviour’.

Notes

1 Prime Minister, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Foreign Secretary, Home Secretary.

2 ‘If there was another referendum on Scottish independence, how do you think you would vote?’.

3 ‘If there was another referendum on EU membership, how do you think you would vote?’.

References

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso. (Original work published 1983)

- Beland, D., & Lecours, A. (2021). Nationalism and the politics of austerity: Comparing Catalonia, Scotland, and Quebec. National Identities, 23(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2019.1660312

- Bell, E. (2021). Post-Brexit nationalism: Challenging the British political tradition? In A. Alexandre-Collier, P. Schnapper, & S. Usherwood (Eds.), The nested games of Brexit (pp. 51–67). Routledge.

- Black, I., Baines, P., Baines, N., O’Shaughnessy, N., & Mortimore, R. (2023). The dynamic interplay of hope vs fear appeals in a referendum context. Journal of Political Marketing, 22(2), 143–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2021.1892900

- Brown, H. (2017). Post-Brexit Britain: Thinking about ‘English Nationalism’ as a factor in the EU referendum. International Politics Reviews, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41312-017-0023-7

- Clarke, J., & Newman, J. (2017). ‘People in this country have had enough of experts’: Brexit and the paradoxes of populism. Critical Policy Studies, 11(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2017.1282376

- De Cleen, B., Moffitt, B., Panayotu, P., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2020). The potentials and difficulties of transnational populism: The case of the democracy in Europe movement 2025 (DiEM25). Political Studies, 68(1), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719847576

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 65(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1086/257897

- Eatwell, R., & Goodwin, M. (2018). National populism: The revolt against liberal democracy. Pelican.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, L. (2017). Welfare chauvinism in populist radical right platforms: The role of redistributive justice principles. Social Policy Administration, 52(1), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12325

- Fieldhouse, E., Green, J., Evans, G., Mellon, J., Prosser, C., de Geus, R., Bailey, J., Schmitt, H., & van der Eijk, C. (2023). British election study internet panel waves (pp. 1–23).

- Ford, R., & Goodwin, M. (2014). Revolt on the right: Explaining support for the radical right in Britain. Routledge.

- Freeden, M. (2017). Is nationalism a distinct ideology?: Revisiting populism as an ideology. Political Studies, 46(4), 1–11.

- Gifford, C. (2015). The UK’s ‘Brexit’ referendum represents a victory for the forces of populist Euroscepticism. Democratic Audit UK, 15th December 2015. http://www.democraticaudit.com

- Goodger, E. (2022). ‘From convergence to Corbyn: Explaining support for the UK’s radical left’. Electoral Studies, 79, 102503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102503

- Goodwin, M., & Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 450–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117710799

- Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. (2016). Continental drift. Cambridge University Press.

- Henderson, A., Jeffery, C., Wincott, D., & Wyn Jones, R. (2017). How Brexit was made in England. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(4), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117730542

- Hepburn, E. (2015). New Scots and migration in the Scottish independence referendum. Scottish Affairs, 24(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2015.0093

- Iakhnis, E., Rathbun, B., Reifler, J., & Scotto, T. (2018). Populist referendum: Was ‘Brexit’ an expression of nativist and anti-elitist sentiment? Research & Politics, 5(2), 205316801877396. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018773964

- Ichijo, A. (2009). Sovereignty and nationalism in the twenty-first century: The Scottish case. Ethnopolitics, 8(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449050902761624

- Ignatieff, M. (1993). Blood and belonging: Journeys into the new nationalism. Macmillan.

- Jackson, B. (2014). The political thought of Scottish nationalism. The Political Quarterly, 85(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2014.12058.x

- Manley, G. (2022). Reimagining the enlightenment: Alternate timelines and utopian futures in the Scottish independence movement. History and Anthropology, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2022.2056167

- March, L. (2017). Left and right populism compared: The British case. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(2), 282–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117701753

- March, L., & Mudde, C. (2005). What’s left of the radical left? The European radical left after 1989: Decline and mutation. Comparative European Politics, 3(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110052

- Massetti, E. (2018). Left-wing regionalist populism in the ‘Celtic’ peripheries: Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party’s anti-austerity challenge against the British elites. Comparative European Politics, 16(6), 937–953. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-018-0136-z

- McAnulla, S., & Crines, A. (2017). The rhetoric of Alex Salmond and the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. British Politics, 12(4), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0046-8

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2010). The populist radical right: A pathological normalcy. West European Politics, 33(6), 1167–1186. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.508901

- Niedzwiedz, C., & Kandlik-Eltanani, M. (2014). Attitudes towards income and wealth inequality and support for Scottish independence over time and the interaction with national identity. Scottish Affairs, 23(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2014.0004

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

- Ramiro, L., & Gomez, R. (2016). Radical-left populism during the great recession: Podemos and its competition with the established radical left. Political Studies, 65(1), 108–126.

- Ruzza, C., & Pejovic, M. (2021). Populism at work: The language of the Brexiteers and the European Union. In F. Zappettini & M. Krzyzanowski (Eds.), “Brexit” as a social and political crisis (pp. 52–68). Routlege.

- Scottish National Party. (2007). SNP Manifesto: 2007.

- Tamir, Y. (2019). Not so civic: Is there a difference between ethnic and civic nationalism? Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-022018-024059

- Valluvan, S., & Kalra, V. (2019). Racial nationalisms: Brexit, borders and Little Englander contradictions. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(14), 2393–2412. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1640890

- van Hauwert, S., & van Kessel, S. (2018). Beyond protest and discontent: A cross-national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 68–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12216

- Vines, E. (2014). Reframing English nationalism and Euroscepticism: From populism to the British political tradition. British Politics, 9(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2014.3

- Viroli, M. (1995). For love of country: An essay on patriotism and nationalism. Clarendon Press.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Support/opposition towards Scottish independence: ‘scotReferendumIntention’ – ‘If there was another referendum on Scottish independence, how do you think you would vote?’

0: ‘I would vote ‘No’ (stay in the UK)’ 1: ‘I would vote ‘Yes’ (leave the UK)’

Support/opposition towards leaving the European Union: ‘euRefVote’ – If there was another referendum on EU membership, how do you think you would vote?

0: ‘Remain in the EU’ 1: ‘Leave the EU’

Nationalist Sentiments: ‘subnatAttach’ – Please tell us whether the following statements about $countrytext are true or false:

subnatAttach1: When someone criticizes $countrytext, I don’t take it as a personal insult.

subnatAttach2: I’m not very interested in what others think about $countrytext.

subnatAttach3: When I talk about $countrytext, I usually say ‘they’ rather than ‘we.’

subnatAttach4: $countrytext ‘s successes are my successes. subnatAttach5: When someone praises $countrytext, it feels like a personal compliment.

subnatAttach6: I act like a $countrydesc person to a great extent.

1: True

2: False

Economic Policy Preferences: ‘Values1’ – ‘How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements?’:

lr1: ‘Government should redistribute income from the better off to those who are less well off’

lr2: ‘Big business takes advantage of ordinary people’

lr3: ‘Ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth’

lr4: ‘There is one law for the rich and one for the poor’

lr5: ‘Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance’

1: ‘Strongly Disagree’

2: ‘Disagree’

3: ‘Neither Agree nor Disagree’ 4: ‘Agree’

5: ‘Strongly Agree’

al1: ‘Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values’

al2: ‘For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence’

al3: ‘Schools should teach children to obey authority’

al4: ‘Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards’

al5: ‘People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences’

1: ‘Strongly Disagree’

2: ‘Disagree’

3: ‘Neither Agree nor Disagree’ 4: ‘Agree’

5: ‘Strongly Agree’

Migration Policy Preferences 1: ‘immigSelf’ – ‘Some people think that the UK should allow *many more* immigrants to come to the UK to live and others think that the UK should allow *many fewer* immigrants. Where would you place yourself and the parties on this scale?’

Migration Policy Preferences 2: ‘immigEcon’ – ‘Do you think immigration is good or bad for Britain’s economy?’

Migration Policy Preferences 3: ‘immigCultural’ – ‘And do you think that immigration undermines or enriches Britain’s cultural life?’

(Response scales for each of the three above have been adapted to be 1 (migrant-exclusive) to 5 (migrant-inclusive)).

Populist Sentiments: ‘Populism’ – ‘Do you agree or disagree with the following statements?’’:

populism1: ‘The politicians in the UK Parliament need to follow the will of the people’

populism2: ‘The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions.’

populism4: ‘I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician’

populism5: ‘Elected officials talk too much and take too little action’

populism6: ‘What people call ‘compromise’ in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles’

1: ‘Strongly Disagree’

2: ‘Disagree’

3: ‘Neither Agree nor Disagree’ 4: ‘Agree’

5: ‘Strongly Agree’

Anti-Expert: ‘antiIntellectual’ – ‘I’d rather put my trust in the wisdom of ordinary people than the opinions of experts’

1: ‘Strongly Disagree’

2: ‘Disagree’

3: ‘Neither Agree nor Disagree’ 4: ‘Agree’

5: ‘Strongly Agree’

Controls:

Ethnicity – ‘p ethnicity’ – ‘To which of these groups do you consider you belong?’

Education – ‘p education’ – ‘What is the highest educational or work-related qualification you have?’

Gender – ‘gender’

Party Identification – partyID – ‘Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat or what?’

Age Group – ‘ageGroup’

Appendix 2

Please find below, under caption ‘’.

Table B1. Mean positions of pro-/anti-independence & pro-/anti-Brexit voters (.95 CIs).