ABSTRACT

This article analyses how the World Bank formulates healthcare financing recommendations by examining the cases of Argentina and Croatia, two representative cases of socio-political transformations in Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe during the Washington (1987–1997) and post-Washington Consensus (1997–2007) periods. It argues that when formulating recommendations, the World Bank is involved in the process of policy bricolage, defined as a process in which policy actors draw on multiple sources of knowledge and information to piece together contextualised policy solutions instead of relying on textbook blueprints or predefined solutions. By conducting a document analysis of World Bank publications, our findings suggest that, in formulating healthcare financing recommendations, the organisation does not dogmatically follow a particular policy paradigm. Instead, it contextualises and recombines existing ideas to tailor recommendations to country-specific conditions, namely economic and political circumstances, as well as healthcare system performance.

1. Introduction

Healthcare financing policy, although it is adopted and implemented within state boundaries, is a matter of global concern: Healthcare financing is a core functional dimension of healthcare systems, and it greatly influences the extent of coverage and financial protection (Frisina Doetter et al., Citation2021; World Health Organization [WHO], Citationn.d.). Healthcare (financing), therefore, is considered a global matter, increasingly impacted by international organisations (IOs). Notably, the World Bank (WB) has become the greatest lender in healthcare policy and one of the most influential actors over the last five decades (Deacon, Citation2007; Kaasch, Citation2015). In line with global social policy research, IOs are regarded as key and legitimate sources of advice for national health policymaking (Niemann et al., Citation2021). One of the main instruments IOs use to shape domestic policies is recommendations, which entail ideas, normative standards, and practical models of desirable forms of social policies (Deacon, Citation2007; Schmitt, Citation2020).

Unlike pension policy, where the WB had a defined reform blueprint (Orenstein, Citation2008), there is limited understanding of the WB's preferences for healthcare financing reform. Moreover, the process of how the WB formulates the content of healthcare financing recommendations is not entirely clear. Does the WB provide healthcare financing policy advice based on top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions? Or does the WB adjust general, established blueprints in view of concrete national conditions? Several studies touch on this topic, but none specifically address it. Although some scholars have argued that the WB favoured a Social Health Insurance (SHI) model in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (Cerami, Citation2006; Nemec & Lawson, Citation2008), recent literature suggests otherwise (Kaminska et al., Citation2021). Similarly, studies on Latin America have revealed that the WB did not offer a clearly defined healthcare reform plan for different countries (Noy, Citation2017; Weyland, Citation2006). Furthermore, some argue that the WB often disregarded specific national conditions (Nemec & Kolisnichenko, Citation2006), while others indicate that it does take them into account (Noy, Citation2017; Weyland, Citation2006; Wireko & Béland, Citation2017).

Following the latter line of thought, this paper argues that the WB formulates healthcare financing recommendations by reinterpreting prevailing policy paradigms in the light of national conditions in a process labelled policy bricolage. To investigate this process, the paper analyses the WB's healthcare financing recommendations in Argentina and Croatia and focuses on the period between 1987 and 2007. During this time, the WB was influenced by two prominent paradigms, the Washington Consensus (WC) (1987–1997) and the post-Washington Consensus (post-WC) (1997–2007). These two paradigms represented significant shifts in the WB's healthcare priorities and were influential worldwide.

Argentina and Croatia are representative cases for the socio-political transformations experienced in Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe during the observation period (Misztal, Citation1992; Vidučić, Citation2000). Both countries shared a preceding statist regime (rightist military dictatorship in Argentina and communism in Croatia) and their transition to democracy and a market economy was marked by wide-ranging reforms as well as the involvement of the WB in social reforms, including healthcare financing (Misztal, Citation1992; Noy, Citation2017; Radin, Citation2008; Weyland, Citation2006). Clearly, both countires underwent numerous significant changes throughout the observed period, thus making them good cases for investigating how the WB responds to continually evolving national conditions.

By means of a dual twofold comparison (Argentina vs. Croatia, WC vs. post-WC periods), this article aims to provide a better understanding of IOs’ healthcare policy recommendation making in middle-income countries that experienced significant changes during the period of observation in terms of social, political and economic contexts. Moreover, the article introduces a novel analytical framework for assessing policy bricolage in IOs’ policy recommendation making. Consequently, it makes valuable contributions to the literature on global social policy and policy bricolage.

The following section provides theoretical background and presents an analytical framework to examine policy bricolage in healthcare policy recommendation making. The third section describes the data used in this research and the data collection and analysis processes. The subsequent empirical sections present national conditions, map WB healthcare financing recommendations in Argentina and Croatia and analyse whether and how the WB acted as a policy bricoleur. Finally, discussions and conclusions of the study are presented.

2. The WB as a policy bricoleur

The analytical framework of this paper derives from the concept of bricolage, an ‘innovative recombination of elements that constitutes a new way of configuring organisations, social movements, institutions, and other forms of social activity’ (Campbell, Citation2005, p. 56). Policy bricolage embodies an evolutionary process where certain policy elements undergo change while others remain unchanged. In this process, policy bricoleur plays a crucial role (Carstensen, Citation2011). It is a policy actor who takes stock of an ‘existing set of ideas, policies, and instruments and reinterprets them in the light of concrete circumstances’ (Carstensen, Citation2011, pp. 155–156). Bricoleurs are, above all else, flexible and pragmatic. They use and combine ideas to make them work within a specific context. In this process, bricoleurs do not strictly adhere to the dominant policy paradigm and can choose ‘ideas that may answer multiple logics simultaneously’ (Carstensen, Citation2011, p. 160). Therefore, their policy ideas are not rigid but are like a toolkit in which multiple ideational perspectives co-exist and in which old and new ideas can be combined and adjusted to create something new (Carstensen, Citation2011). In this perspective, paradigms are viewed as flexible and adaptable frameworks, susceptible to continuous reinterpretation and modification over time (Carstensen & Matthijs, Citation2018).

Existing research on bricolage usually deals with policy change topics in which disparate existing policies were repurposed and recombined to offer (new) policy solutions (e.g. Allain & Madariaga, Citation2020; Carstensen, Citation2017; Hannah, Citation2020). For instance, Allain and Madariaga (Citation2020) argue that in Chile, environmental organisations successfully garnered wider political support and integrated their ideas into a new energy policy by creatively combining existing policy ideas. These ideas included multiple perspectives such as environmental protection, economic efficiency, local development and democratisation, and supply security.

This paper conceptualises policy bricolage primarily as a process in which policy actors draw on multiple sources of knowledge and information to piece together contextualised policy solutions instead of relying on textbook blueprints or predefined solutions. This paper argues that the WB uses bricolage to formulate policy recommendations by reinterpreting and/or combining current and/or past policy paradigms in view of current national conditions. Accordingly, the WB, as a bricoleur, follows a four-step approach: It (1) takes stock of past and current policy paradigms (existing set of ideas), (2) evaluates current national conditions (concrete circumstances), (3) reinterprets the existing ideas in light of domestic conditions, and (4) formulates recommendations. These four necessary steps, then, constitute the process of policy bricolage.

Even though policy bricolage considers any extant, past or present, ideas to develop policy solutions, we operationalise the stock of ideas by considering the dominant and distinct policy paradigms existing during our observation period. The literature argues that during this period, the WB was focused on healthcare system reform and that its recommendations followed two different paradigms, WC (1987–1997) and post-WC (1997–2007) (Tichenor & Sridhar, Citation2017).

The WC refers to homogeneous neoliberal solutions for (social) policies promoted by International Financial Institutions (IFIs), such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the WB (Almeida, Citation2015). These solutions were mainly designed for Latin American countries to assist them in recovering from the economic and financial crises they experienced during the 1980s; however, the WC ideas rapidly spread to other regions, such as CEE (Lütz & Kranke, Citation2014; Williamson, Citation1993). The approach revolved around the principles of liberalisation, privatisation and macro-stability to expand private markets and, consequently, minimise (and replace) the role of the state (de Carvalho & Frisina Doetter, Citation2022). Improving health conditions was understood as a way to leverage economic development, with a ‘selective increase of social spending focused on the poorest’ (Almeida, Citation2015, p. 211, own translation). With regards healthcare financing, these neoliberal solutions were mostly laid out in the WB's publications such as Financing health services in developing countries (1987) and Investing in Health (1993). The main instruments promoted by the WB during the WC period were related to the establishment and/or expansion of private financing sources (such as voluntary private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments), encouragement of non-government provision of health services, decentralisation to lower levels of government, and the introduction or expansion of risk-coverage programmes (i.e. schemes in which individuals participate in some form of risk-sharing agreement). Further, the WB insisted that public healthcare spending should be focused on ‘a basic basket of services based on a cost-effectiveness evaluation of each medical procedure’ (Tobar, Citation2010, p. 119, own translation) that prioritises primary care, and vulnerable groups (Almeida, Citation2015; Deacon, Citation2007; Noy, Citation2017; Tichenor & Sridhar, Citation2017; World Bank [WB], Citation1987, Citation1993).

As the limitations of the WC became more apparent, a new approach emerged known as the post-WC. The main difference to the WC was the view that the state and the market should complement each other (Krogstad, Citation2007; Öniş & Şenses, Citation2005). Moreover, the primary goals were not only economic growth and efficiency but also social protection, e.g. alleviation of unemployment, poverty, and inequality (Öniş & Şenses, Citation2005). The concept of health was also redefined as an end in itself rather than an investment in human capital and economic growth (Noy, Citation2017). While the WB remained concerned about efficiency, it also started emphasising universal healthcare coverage, equity, risk protection, increased access, quality of services, and health outcomes (Deacon, Citation2007; Kaasch, Citation2015; Noy, Citation2017). To achieve these goals, the WB advocated for an increased role of the state, mobilisation of additional resources, less reliance on user-fees, expansion of risk pooling and taxation instruments (Deacon, Citation2007; Fair, Citation2008; Kaasch, Citation2015; Noy, Citation2017). Noy (Citation2017) argues that the WB shifted its emphasis from neoliberal ends to neoliberal instruments. For instance, performance-based management or targeting were sometimes used to achieve equity and universalism. Finally, the post-WC emphasised government ownership and adapting lending policies to the country's needs (WB, Citation1997).

This study refers to existing national conditions which have a significant impact on social and health policymaking: namely, economic, political, and healthcare system performance factors. Economic conditions impact the resources available for healthcare, dictating the level and quality of service provision (Polte et al., Citation2022; Wilensky, Citation1975). Political factors are also said to explain changes in welfare. There is a strong causal relationship between the alignment of parties in government with social groups and social policy change (e.g. Myles & Quadagno, Citation2002). Further, pressing health issues and the performance of the healthcare system stimulate the development of healthcare policy to adjust and/or advance health policy outputs and outcomes (Cacace et al., Citation2008; Schmid et al., Citation2010).

In this paper, evidence of bricolage relies on the necessary condition that the WB considers the existing stock of ideas and national conditions to formulate recommendations. This may be presented in two different ways. First, the WB may adjust policies associated with the dominant paradigm of the time (WC or post-WC) to different national conditions. In other words, although the recommendations follow the paradigm, they differ depending on the country. Second, recommendations may deviate from and/or contradict the dominant paradigm. For example, the observation of non-neoliberal principles in the WC period and neoliberal, pro-market principles in the post-WC years. It should be noted that this paper only analyses the WC and post-WC paradigms.

3. Data collection and analysis

The data used in this article comes from two main sources: Secondary scholarship and documents published by the WB. The former was used to outline internal national conditions in each country, namely, political and economic conditions and healthcare system performance. These factors were selected in accordance to scholarship, as stated in the previous section. To map WB healthcare financing recommendations, all reports and strategy papers published by the WB regarding the cases of Argentina (1987–2007) and Croatia (1993–2007)Footnote1 were collected. These were identified via structured searches in the WB's public database using the filters ‘Argentina’ OR ‘Croatia’ AND ‘Health Systems Development and Reform’ in English and Spanish/Croatian equivalents. In addition, an unstructured search was conducted to account for non-indexed documents. Searches were conducted between June and August of 2022.

The documents selected for analysis meet five criteria: They (a) were produced between 1987 and 2007; (b) addressed the topics of healthcare and/or healthcare financing; (c) contained recommendations related to healthcare financing; (d) do not contain a disclaimer that the document does not represent the opinion of the WB; and (e) addressed the whole country, as opposed to specific regions/provinces. After excluding documents that did not meet the pre-established criteria, 14 publications related to Argentina and 11 to Croatia were identified for analysis.Footnote2

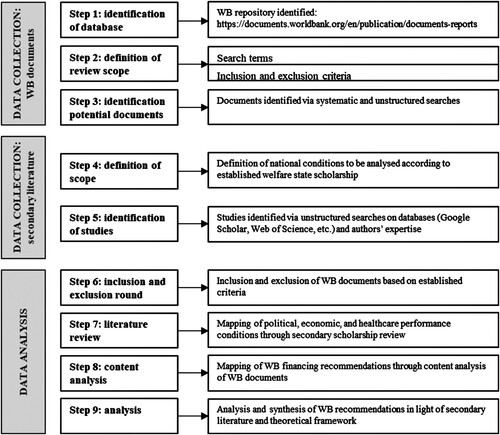

The methods employed were a literature review of the secondary scholarship and a qualitative content analysis of WB documents. The analysis is divided into two periods corresponding to the WC and post-WC paradigms. For both countries, national conditions are first described, accounting for, among others, shifts in the party in power, political (in)stability during the period, economic recession and growth/recovery, and healthcare system performance. Then, healthcare financing recommendations published by the WB in each period are mapped. Finally, an analysis considering the aforementioned analytical framework is used to determine whether and how the WB acted as a policy bricoleur. details the data collection and analysis steps employed in this research.

4. 1987–1997: Washington Consensus paradigm

4.1. ArgentinaFootnote3

Between 1987 and 1997, Argentina transitioned back to democracy after seven years of military dictatorship characterised by a weak economy and hyperinflation (Blake, Citation1998; Colonna, Citation2019; O’Donnell, Citation2008). The previous statist model was restructured and pro-market, neoliberal reforms were advanced by Menem from the leftist Partido Justicialista (Justicialist Party, PJ) (Blake, Citation1998; Nochteff, Citation2002) in order to control the early 80s economic crisis (Cerruti & Ciancaglini, Citation1992). These reforms resulted in lower inflation, lower unemployment, higher foreign investment and an annual GDP increase of about 6.5% (García-Lema, Citation1994). The initial success of neoliberal policies in the economy opened the door to further market-oriented reforms in social areas, such as pension and healthcare (Etchemendy & Palermo, Citation1998).

In this period, the expenditure on health was around 8% of GDP and Argentina's healthcare system was characterised by segmentation with different financing schemes targeting distinct societal groups (Alonso, Citation2003; Guerrero Espinel et al., Citation1999; Stillwaggon, Citation1998; WB, Citation2023). A SHI scheme covered more than 50% of the population, comprising more than 300 different funds which only pooled risks for their members (Rubinstein et al., Citation2018; Tobar, Citation2012). To compensate for the differences between poorer and richer funds, the Fondo Solidario de Redistribucion (Solidarity Redistribution Fund, FSR) was created in 1989. Although not fully implemented at the time, the FSR reimbursed money to different health insurance funds for complex and expensive treatments and provided subsidies to the poorest funds. A private insurance scheme was financed by monthly premiums and targeted the upper classes. Finally, a tax-funded scheme targeted the most vulnerable segments of society not covered by SHI or private insurance, particularly informal workers and the poor (Cavagnero, Citation2008). The SHI and tax-funded schemes were not able to cover the costs of all available health treatments (D7). In terms of health conditions, it is important to note that the poor, in particular children and mothers, suffered from inadequate healthcare (D2).

During this period, the WB supported PJ's neoliberal agenda and pushed for (public) cost control, liberalisation, increasing private sector involvement, and reducing the role of the state. The WB argued that public healthcare expenditure was too high due to a large number of doctors and hospital beds and a growing demand for healthcare services (D7). In order to reduce costs, moderate demand, and guarantee basic services to the whole population, the WB recommended that every healthcare financing scheme should (1) create and standardise a basic benefits package (D4) and (2) implement cost-recovery from individuals and third-party payers by billing for services provided by public facilities. At the same time, the WB recognised the high mortality and morbidity levels of poor children and mothers and recommended that the tax-funded scheme (3) expand health services (such as prenatal, child delivery, and postnatal care) to these groups (D2) and (4) define priority services to be financed by government subsidies (D3).

Most recommendations concerned the SHI scheme, which covered the largest portion of the population due to low unemployment. The WB aimed to liberalise the sector and introduce market mechanisms to reduce the number of funds. Accordingly, the WB recommended to (5) ‘introduce consumer choice of insurer’ (D7, p. 24); (6) allow ‘competition among private and public insurance institutions’ (D6, p.19) and among union-run health insurers (D6); (7) ‘leave employees to purchase additional coverage if they wish’ (D7), and (8) ‘reduce payroll taxes from 7 to 5.5% for health insurance to a level that would just cover the cost of the standard package for everyone’ (D5b, p.25). Moreover, the WB tried to tackle the issues associated with risk pooling and recommended that FSR (9) automatically allocate funds on the basis of members’ income, starting with the poorest, and (10) compensate for household differences in income and health risk.

4.2. Croatia

Croatia began transitioning away from the communist regime in the early 1990s. This transition was led by the Croatian Democratic Union (CDU), a right-wing party determined to achieve democratisation, liberalisation, marketisation, and independence from the Yugoslav Federation. This period was characterised by economic and political crises and the Croatian War of Independence (1991–1995), which followed Croatia's secession from the Yugoslav Federation (Ramet, Citation2013). Inflation and unemployment surged while GDP declined dramatically compared to pre-war levels (D15; Ramet, Citation2013; Stubbs & Zrinščak, Citation2007). After the war, the political and economic situation started to improve. Although GDP grew by 6% in 1996 and 1997, 9.7% of the population remained unemployed (WB, Citation2023). The CDU became increasingly dependent on voter support which was acquired by increasing public spending (Schönfelder, Citation2013). Consequently, disempowered groups, such as war veterans, their families, and, to a certain extent, pensioners, could claim generous social benefits (Puljiz et al., Citation2008; Stubbs & Zrinščak, Citation2007).

Regarding healthcare financing, Croatia inherited a heavily decentralised SHI system in which multiple SHI funds were organised at the municipal level according to Bismarckian and self-management principles (Malinar, Citation2022). Healthcare benefits and coverage were practically universal. However, the system faced numerous issues due to heavy decentralisation, lack of financial expenditure controls, duplication of procedures, inequality of access, lack of medical equipment and drugs, as well as economic and political crises (Chen & Mastilica, Citation1998; Šarić & Rodwin, Citation1993). The reforms initiated in the early 1990s aimed to contain costs, introduce liberal and market policies, and, at the same time, maintain solidarity (Malinar, Citation2022). In 1993, SHI was centralised into one national health fund, the Croatian Institute for Health Insurance (CIHI), which collected and pooled payroll tax contributions.Footnote4 Co-payments for selected services were established, while groups such as war veterans, the unemployed, and children were exempted (Kovačić & Šošić, Citation1998; Vončina et al., Citation2007). Finally, substitutive and supplementary private insurance were introduced (Zrinščak, Citation2007). Despite the reforms, healthcare expenditure rose from 6.4 to 8.6% of GDP during the 1993–1996 period (D16). The expenditure was driven by inappropriate management and resource allocation, outdated technology, and high demand for services, especially pharmaceuticals (Langenbrunner, Citation2002; Vončina et al., Citation2007; WHO, Citation1999).

The WB only became involved in Croatian healthcare in 1995 because the war interrupted and delayed its dialogue with Croatia (D15). At this time, the WB praised the 1993 reforms, highlighting the importance of redefined healthcare benefits, centralising SHI, and enabling private insurance involvement. Moreover, to support their implementation, the WB financed the Health Project, which was primarily prepared by the government itself (D15). However, as public healthcare expenditure began to rise, the WB noted that the previous reforms should be extended to preserve the sustainability of the healthcare system and fiscal sustainability (D16; D17).

In particular, the WB wanted to address post-war social entitlements by reducing the benefits and shifting the burden of financing on to those who could pay. Moreover, the WB argued that increased unemployment and the growing informalisation of the economy hindered the collection of payroll taxes. Efforts to raise revenue from other sources (e.g. co-payments) were necessary to reduce reliance on payroll contributions. In addition, the WB noted that the tax burden was too high, which created incentives to misreport wage income and discouraged formal employment (D16; D17). To address these issues, the WB recommended: (1) reducing payroll tax; (2) moderating the demand for healthcare services by removing co-payment exemptions (except for the poor) and increasing the scope and rate of co-payments; and (3) further developing a private insurance market and its regulation (D16; D17).

4.3. Analysing policy bricolage in the WC period

During the 1987–1997 period, the WB recommendations for Argentina and Croatia were heavily aligned with WC and neoliberal ideas, such as curbing public spending on health and encouraging private sources of revenue, be it through private insurance or out-of-pocket payments. However, the WB also considered the different national conditions in both countries when it formulated its recommendations. In Argentina, the WB supported the government's pro-market neoliberal programmes and took into account SHI fragmentation, healthcare system segmentation, issues associated with risk pooling, and high mortality and morbidity levels of poor children and mothers. The WB was mainly focused on reducing the role of the state, increasing competition between SHI funds, instituting complementary private insurance and a basic benefits package, and targeting health services to poor mothers and children. These recommendations are strongly associated with cost-saving and efficiency, which were extensively promoted during the WC.

In Croatia, the WB offered a loan to support the government's pro-market initiatives and implementation of the 1993 healthcare financing reforms. Later, the WB noted the rise in public healthcare expenditure, high unemployment, a growing informal economy, and issues concerning post-war social claims-making. Compared to Argentina, where the WB favoured competition between SHI funds, in Croatia, the WB favoured a centralised model of SHI insurance, which increased the role of the state. Moreover, the focus in Croatia was on diversifying the sources of revenue collection, private insurance development (substitutive and supplementary), and moderating the demand for healthcare services by increasing the role of co-payments while exempting the poor.

The evidence shows that the WB formulated its recommendations by considering and combining different sources of knowledge, i.e. the WC and an evaluation of different national conditions found in Argentina and Croatia, in particular healthcare system performance and healthcare policies which were already in place. It can be observed that most of the recommendations reflect the ideas of the WC, but at the same time, they are contextualised for different national conditions. However, the WB did not strictly adhere to the established paradigm because some recommendations diverged from what is usually associated with neoliberalism. For instance, the WB showed a preference for a centralised SHI model in Croatia and FSR's redistribution of funds from wealthier to poorer SHI funds in Argentina. The WB did not have a uniform approach for both countries and deviated from the WC to adjust its recommendations to national conditions. Therefore, it can be argued that during this period, the WB indeed acted as a policy bricoleur. However, for the most part, this role was limited to contextualising the WC to different national conditions.

5. 1997–2007: post-Washington consensus paradigm

5.1. Argentina

After ten years in power, the PJ lost the election to the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Civic Union) led by Fernando de la Rúa (1999–2001) (Corrales, Citation2002; Ollier, Citation2001). Between 1998 and 2002, the economy shrank by 28%, GDP decreased by 11%, private consumption fell by 14.4% while unemployment and poverty increased dramatically, with 56% of the population living below the national poverty line (Bernhardt, Citation2008; Cibils et al., Citation2002; WB, Citation2023). The economic turmoil was accompanied by social unrest and political instability. Although de la Rúa favoured increased social spending to address the crises, his attempts failed, and he was eventually forced to resign (Auyero, Citation2007; Corrales, Citation2002; Hochstetler, Citation2006). Soon after, Argentina had five provisional and congress-elected presidents and announced a default on the government's debt to foreign investors (Bernhardt, Citation2008).

The political and economic situation stabilised only when Nestor Kirchner (PJ) (2003–2007) came to power. Kirchner was highly critical of the US and the constraints imposed by IFIs (Becerra, Citation2015). He distanced himself from the pro-market agenda and promoted greater state intervention, poverty and unemployment reduction, and income redistribution (Busso, Citation2016; Levitsky & Murillo, Citation2008). His election was followed by high GDP growth rates of around 8% annually and low inflation levels (Mercado, Citation2007). Unemployment fell from 13.5 to 8.5% in the period, while poverty decreased from 60% in 2002 to 19% in 2007 (D12; WB, Citation2023).

During the WC period, several healthcare financing changes were introduced (Barrientos & Lloyd-Sherlock, Citation2000; Cavagnero, Citation2008; Tobar, Citation2012). First, co-payments and complementary insurance were introduced in both the tax-funded and SHI sector (Machado, Citation2018). Second, public hospitals were allowed to charge user-fees, although this did not translate into more resources (Cavagnero, Citation2008; Lloyd-Sherlock & Novick, Citation2001). Third, the FSR established criteria to redistribute revenue between richer and poorer healthcare funds (Cavagnero, Citation2008). Fourth, the private sector was growing because public healthcare funds could transfer provision and regulation responsibilities to private providers and companies (Arnaudo et al., Citation2017). According to Tobar (Citation2012), an expansion of private services and insurance offerings was driven by state incentives, which ‘reaffirms the notion of health as a commodity’ (Tobar, Citation2012, p. 14, own translation). Fifth, employers’ contributions were reduced from 7% to 5% to cut labour costs. Ultimately, in an attempt to reduce the high number of healthcare funds, the SHI sector was liberalised, and workers were free to select their funds (Cavagnero, Citation2008; Machado, Citation2018). However, the number of funds remained high, e.g. 268 in 2003 (D7; D10).

Between 1998 and 2002, healthcare expenditure decreased by 2% of GDP (WB, Citation2023). Low contribution rates, the growing informal economy, and high unemployment caused a decrease in revenue and coverage in the SHI sector (Lloyd-Sherlock & Novick, Citation2001). Moreover, 9% of the population lost SHI coverage, and most transferred to the tax-funded sector. This put additional pressure on the already underfinanced system (Lloyd-Sherlock & Novick, Citation2001). Moreover, the crises exacerbated further health inequalities, especially the rise of infant mortality and the incidence of infectious diseases in mothers and children in poorer areas (Johannes, Citation2007).

During the tenure of the UCR/de la Rúa and the provisional presidents, the WB was particularly concerned with deteriorating healthcare coverage caused by increased poverty and high unemployment. The WB was willing to support de la Rúa's and the provisional presidents’ intent to increase social spending to cushion the effects of ongoing political and economic crises. In general, the WB encouraged the expansion of coverage to vulnerable groups; however, it recommended that public spending should target social groups that could not be integrated into the SHI.

The WB made several recommendations regarding the SHI scheme. It recommended that the scheme should (1) not only cover formal employees but also be expanded to those in the informal sector. The WB also suggested that (2) eligible beneficiaries to SHI should be clearly defined. These two measures were proposed to strengthen social protection for beneficiaries. It also suggested (3) the creation of parallel and alternative health plans for uninsured non-poor households (D8; D9; D10).

To extend coverage to those ineligible for or unable to be covered by the existing SHI scheme, the WB suggested the creation of tax-funded alternative health plans for the uninsured population. The first scheme involved the (4) establishment of health insurance for the poor, which offered (5) a fiscally affordable basic benefit package. Additionally, the WB proposed (6) creating the Maternal-Child Health Insurance Programme. This policy targeted pregnant women and children up to age six who were not covered by the SHI scheme. The programme would also (7) define a basket of services tailored to the specific needs of mothers and children (D13; D14).

These recommendations were an active response from the WB to the economic crisis. They aimed to compensate for the loss of insurance, the significant growth in demand in the tax-funded sector, and to mitigate health challenges among vulnerable populations.

Moreover, the WB recommended measures for both SHI and tax schemes. It encouraged the (8) decentralisation of the systems by separating financing from the service delivery functions in the public sector at the provincial level. This can be seen as an attempt to transfer authority to provincial governments in response to central government turmoil, with continued emphasis on targeting and tailoring schemes (and services) for disadvantaged segments of society (D10; D11; D12).

When Kirchner came to power, health spending constituted around 7% of GDP, and a three-tier system continued to exist (D12; WB, Citation2023). The economic and political crises of 1999–2002 had long-lasting effects on the delivery of public programmes, impacting public responses, especially in relation to the control of diseases (D13; D14). Kirchner's government restored contributions to 6% of payroll and increased the percentage of contributions channelled through the FSR to mitigate the consequences of health spending cuts promoted by the government and the WB in the WC period (Cavagnero, Citation2008). Moreover, a system for uninsured mothers and children was implemented, which secured funding for priority services and achieved 65% coverage of the eligible population (D13; D14). Nevertheless, great inequalities between society's vulnerable and wealthier segments in terms of mortality (especially for mothers and children) and morbidity remained and were aggravated by the 1998–2002 economic crisis (Bossio et al., Citation2020; Finkelstein et al., Citation2016; Tobar, Citation2002; D12).

During Kirchner's administration, the WB produced the lowest number of recommendations on healthcare financing. Kirchner's open opposition to IFIs may have discouraged the WB from pushing for new and bolder reforms. Instead, it can be observed that the WB aligned with Kirchner's agenda and continued promoting already established measure that targeted vulnerable populations. Even though the WB had already tried to tackle health problems caused by the 1998–2002 crisis prior to Kirchner's election, the effects of the turmoil, including declining health outcomes and increasing health disparities, continued to be a prominent issue in the WB's agenda. The IO focused on these pressing issues rather than healthcare financing itself (D12, p. 9).

Consequently, the recommendations the WB put forth remained somewhat unchanged between de la Rua's and Kirchner's administrations, with continued emphasis on targeting and tailoring schemes (and services) for disadvantaged segments of society. There was still a clear focus on mothers and children; however, other vulnerable groups, such as indigenous and rural peoples, were also targeted. Moreover, concerns about the benefits package continued with the WB pushing for a revision of the basket of benefits for uninsured mothers and children to increase cost-effectiveness.

5.2. Croatia

In the late 1990s, the CDU weakened considerably and in 2000 a coalition headed by the left-wing Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the centrist Croatian Social Liberal Party (HSLS) came to power (Bičanić & Franičević, Citation2003, p. 24; Stubbs & Zrinščak, Citation2007). The new government continued pro-market reforms, initiated social policy reforms, consolidated Croatian democracy, and began to westernise (Bičanić & Franičević, Citation2003; Stubbs & Zrinščak, Citation2007). However, the government suffered from internal struggles and negative public opinion and had to fulfil high expectations for economic growth and social justice (Bičanić & Franičević, Citation2003; Kasapović, Citation2005). In 2003, a new centre-right government led by the CDU came to power, lasting until 2007. It continued social and economic policy reforms but also faced internal disagreements and was reliant on support from its coalition partners, mainly the Pensioner's Party and the Serbian Democratic Party (Stubbs & Zrinščak, Citation2007).

GDP growth slowed from 6.1% in 1997 to −0.9% and 2.9% in 1999 and 2000, respectively. However, from 2002–2007, GDP recovered significantly, averaging around 5% growth annually. Inflation surged to 8.2% in 1998 but quickly decreased in the following year. Until 2007 it remained relatively stable, between 3% and 4%. Unemployment peaked at 16.1% in 2001 and gradually decreased to 9.9% in 2007 (WB, Citation2023). Moreover, Croatia was still recovering from the war, and had to tackle excessive trade and fiscal deficits, rising public debt, and insolvencies of banks and state-owned enterprises (Bičanić & Franičević, Citation2003, p. 18; D20 Bebek & Santini, Citation2013; Schönfelder, Citation2013; WB, Citation2008).

In healthcare, public expenditure continued to rise as issues from the previous period persisted. The adverse economic situation created an additional mismatch between revenue and expenditure (Langenbrunner, Citation2002). In 2000, total healthcare expenditure amounted to 10.2% of GDP (Croatian Parliament, Citation2006), and CIHI's debts were about EUR 500 million (Zrinščak, Citation2007). Private insurance played a marginal role, amounting to 6% of total healthcare expenditure in 2002 (Langenbrunner, Citation2002; Vončina et al., Citation2007).

The WB tried to use the reform-motivated and market-oriented SDP-led government to break the status quo and push for healthcare financing reforms. The WB was particularly concerned about the CIHI's deficit and debts, high public healthcare expenditure, generous healthcare benefits, and lack of revenue diversification (D18; D19; D20). Moreover, the WB argued that dwindling CIHI revenues were caused by the growth in unemployment and the informal economy and warned that high labour costs discouraged formal employment (D21). To address these issues, the WB recommended (1) reducing payroll tax; (2) moderating the demand for healthcare services by removing co-payment exemptions and increasing the scope and rate of co-payments. However, compared to the WC period, the WB recommended that besides the poor, other groups, such as chronic patients, should remain exempted from co-payments. The WB further recommended to (3) introduce a basic basket of healthcare services; (4) levy additional SHI contributions from non-wage labour, i.e. honoraria, and (5) centralise SHI by merging CIHI with the government budget (D20; D21; D22).Footnote5

Eventually, the SDP-led government introduced several changes: (1) payroll tax was reduced twice, eventually down to 15% in 2003; (2) the scope and rate of co-payments were increased while exemptions from co-payments were decreased. However, groups such as war veterans, the unemployed, and the disabled remained exempted; (3) complementary health insurance (CHI), which covered co-payments, was introduced. Monthly premiums were fixed at EUR 10.50 and EUR 6.50 for pensioners. CIHI was given the exclusive right to initially offer CHI while private insurers could not enter the market for two years (Vončina et al., Citation2007; Zrinščak, Citation2007); (4) substitutive private insurance was abolished to pull more insurers into the SHI (Vončina et al., Citation2007); (5) CIHI was incorporated into the government budget (Vončina et al., Citation2007; Zrinščak, Citation2007).

Despite these reforms, healthcare expenditure rose (Vončina et al., Citation2010). Financing remained reliant on payroll tax, and CIHI still experienced sizeable deficits between 2003 and 2006. Moreover, CHI introduced the problem of adverse selection and contributed to moral hazard, which co-payments were meant to mitigate (Langenbrunner, Citation2002; Vončina et al., Citation2007, Citation2010). After the change of government in 2003, the WB worked with the CDU-led government, insisting on healthcare financing reforms.

The WB was unsatisfied because public healthcare expenditure and CIHI's deficit remained high. Although the payroll tax rate was reduced and the economy was recovering, the WB still argued that it ‘place[d] a heavy burden on the productive labour force and the economy’ and that additional revenue from co-payments and CHI was necessary (D23, p. 40). In response to the abolished substitutive private insurance, the WB stated that sustainability of the SHI was increased as it enabled it to pool more insurers. However, the WB also stated that it was a setback in private insurance development and that a private voluntary health insurance market should be promoted instead (D23). Finally, the WB argued that broad co-payment exemptions and the existence of CHI exacerbated the moral hazard issue and that CHI suffered from adverse selection and increased administrative costs (D23).

This time the WB recommended (1) reducing payroll tax; (2) moderating demand for healthcare services by introducing means-testing criteria for co-payment exemptions and further increasing the scope and rates of co-payments; (3) introducing a basic basket of healthcare services, and (4) abolishing CHI and instituting ceilings on co-payments for chronic patients or allowing only private insurance companies to offer CHI (D23; D24; D25). The WB argued that the premiums of private CHI would appropriately reflect the cost of services and ensure that excessive demand for services would be controlled (D25).

However, during the appraisal of reform progress, the WB recognised that the CDU-led government was unwilling to shift the CHI to the private insurance market or introduce a basic basket of services. Consequently, the WB recommended alternative policies acceptable to the CDU government (D25). These included: (1) the introduction of user-fees for primary care visits, referrals, recommendations, and visits to specialists without referrals, (2) reducing the scope of pharmaceutical coverage by introducing essential (fully covered by SHI) and non-essential (subject to co-payments) lists of pharmaceuticals and (3) reducing the scope of CHI coverage which should not include user-fees nor pharmaceuticals on the non-essential list.

5.3. Analysing policy bricolage in the post-WC period

The empirical evidence presented here shows that during the post-WC period, the WB formulated its recommendations in both countries by considering principles consistent with the post-WC, as well as the WC. Moreover, as in the WC period, the WB also considered national conditions when formulating its recommendations. In Argentina, the WB considered the effects of political and economic crises and was particularly concerned about increased poverty and high unemployment, which shrank healthcare coverage, deteriorated health outcomes, and fuelled health inequalities. The WB also considered the positions of different governments. For instance, it backed UCR's proposal to increase social spending and acknowledged Kirchner's reluctance to collaborate with IFIs and introduce further healthcare financing reforms. The WB still advocated for neoliberal ideas such as defining basic health services to increase cost-effectiveness, decentralising the tax-funded and SHI healthcare financing schemes, and targeting. It is important to note that even though targeting is usually associated with neoliberalism, in this period it served as an instrument to restore and/or expand coverage to vulnerable population groups, such as the poor, mothers and children, indigenous people, and those not covered by SHI. Therefore, it can be observed that the WB recommendations began to move away from the fundamental principles of neoliberalism, such as prioritising cost-effectiveness, promoting efficiency through privatisation, and minimising the role of the state. Instead, the WB was focused on restoring and expanding coverage in both SHI and tax-funded schemes by increasing the role of the state and mobilising additional resources for vulnerable groups.

In Croatia, the WB recognised the growth in the unemployment rate and the informal economy as well as issues facing the healthcare system more directly, such as CIHI's deficits and debts, lack of revenue diversification, moral hazard, and adverse selection in CHI. Similar to the case of Argentina, the WB was also adjusting to the government agenda, e.g. changing its recommendations to better suit the preferences within the CDU-led government coalition. In contrast to the recommendations made for Argentina, the WB was still focused on reducing public healthcare expenditure and social protection. Consequently, neoliberalism was more prominent. Most of the recommendations revolved around reducing healthcare benefits, expanding private sources of revenue (e.g. out-of-pocket payments and private voluntary health insurance) and promoting individual responsibility for health. However, the WB also recommended policies which were consistent with the post-WC. For instance, some neoliberal recommendations were more nuanced (e.g. co-payment exemptions, not only for the poor, but also for other groups such as chronic patients), while some recommendations completely diverged from neoliberalism (e.g. expansion of payroll taxes, endorsing the abolishment of private substitutive insurance, and further centralisation of SHI). It can be observed that post-WC principles were less emphasised in the WB's recommendations for Croatia. They mostly involved the increased role of the state in the mandatory SHI, mobilisation of additional resources, and expansion of taxation instruments. Interestingly, in both countries, during times of economic crisis, the WB recommended policies which increased the role of the state, aligning with post-WC ideas. For instance, in Croatia, the WB advocated for stricter control of the SHI fund, while in Argentina, the WB supported the expansion of the tax-funded scheme.

Considering the points mentioned above, it is clear that the WB began to embrace post-WC principles. This was more evident in Argentina than in Croatia, where the WB still prioritised WC and neoliberal tenets. Much like during the WC period, the WB's approach in formulating healthcare financing recommendations was neither uniform nor monolithic. The WB considered specific national conditions, leading to divergent suggestions for each country. Moreover, the WB did not strictly follow the post-WC paradigm. Compared to the previous period, where the WC principles were primarily contextualised to different national conditions, the WB formulated its recommendations by taking inspiration from two different paradigms simultaneously, WC and post-WC. In other words, the WB did not just contextualise the post-WC to national conditions but also deviated from it by recommending ideas aligned with the WC. This was particularly notable in Croatia, thus further supporting the argument that the WB did not rely on paradigms as dogmas. Instead, the WC and post-WC were regarded as toolkits providing different tools which were used to respond and adjust to the concrete circumstances in Argentina and Croatia. Therefore, the WB was involved in the process of bricolage when it formulated its recommendations. During this process, the WB considered the principles found in the WC and post-WC, as well as different national conditions. summarises the empirical findings of the study.

Table 1. The WB approach to Argentina and Croatia during the WC and post-WC period.

6. The WB as policy bricoleur: final remarks and future research

This study investigated WB healthcare financing recommendations in Argentina and Croatia from 1987 to 2007. Literature suggests that during this period, WB recommendations were framed within WC (1987–1997) and post-WC (1997–2007) paradigms (Tichenor & Sridhar, Citation2017). However, the cases of Argentina and Croatia demonstrate that by considering national conditions when formulating recommendations, the WB did not strictly adhere to mentioned paradigms.

In the first period, the WB primarily promoted neoliberal ideas associated with the WC which were contextualised to unique domestic circumstances. Moreover, in its attempt to adjust to national conditions, the WB went as far as diverging from the WC and neoliberalism. The second period saw the WB considering national conditions as well as neoliberal and post-WC principles, with the latter more evident in Argentina than Croatia. Neoliberal rhetoric began to evolve in both countries, with some recommendations being abandoned or becoming less pervasive (e.g. reducing the role of the state in Argentina) while others were more nuanced (e.g. co-payment policy in Croatia). Moreover, in Argentina, neoliberal instruments such as targeting were utilised to advance post-WC goals (e.g. coverage expansion) rather than promoting cost saving.

It can be observed that in both periods the WB acted as a policy bricoleur. It took stock of existing ideas (WC and post-WC) and reinterpreted or deviated from them to adjust recommendations to Argentinian and Croatian national conditions. As a result, the WB did not consider the WC and post-WC as paradigms to be followed rigorously or dogmatically but rather as tools to be used and (re)combined to address country specific issues. Furthermore, it is evident that the WB does not ignore ideas from past paradigms. This is most clearly seen during the post-WC period, when the WB still formulated recommendations which can be associated with the WC, especially in Croatia. This nuanced approach shows that the WB considers multiple sources of knowledge when formulating healthcare financing policy recommendations. In these particular cases, past and contemporary policy paradigms, national political and economic conditions, and healthcare system performance.

It can be argued that, as a policy bricoleur, the WB is more capable to adapt, innovate its approach and provide country tailored recommendations in the face of diverse and changing national conditions. This is particularly crucial for an organisation dealing with a wide range of countries with distinct political, economic, and social conditions. By providing country tailored recommendations in such diverse environments, the WB can preserve and extend its authority and expert legitimacy (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004). Moreover, bricolage can also be used to garner wider political support for reform (Allain & Madariaga, Citation2020), thus improving the prospects for implementing WB's policies.

Furthermore, the concept of the WB as a policy bricoleur has implications for understanding WC and post-WC periods. It suggests that WB policy recommendations cannot be strictly categorised within distinct paradigms and policy eras. Instead, the WB selectively incorporates and combines elements from different policy paradigms, thus blurring the boundaries between them. Consequently, WC and post-WC should be viewed with more nuance, aligning with the argument that paradigms are flexible frameworks open to continuous reinterpretation (Carstensen & Matthijs, Citation2018).

To conclude, the paper has shown that the WB did not rely on pre-cooked ideas which should be blindly implemented despite the particularities of each country. Instead of proposing one-size-fits-all recommendations, the WB appeared as a policy bricoleur, a pragmatic and reflexive actor which formulates its recommendations by reinterpreting current and/or past paradigms in light of concrete circumstances.

These findings are consistent with the scholarship which argues that the WB does not offer a single blueprint for healthcare financing reforms and that it accounts for specific national conditions (Noy, Citation2017; Weyland, Citation2006). Consequently, the paper provides further evidence that the WB does not act as a neoliberal hegemon in healthcare financing and is willing to use the ‘logic of accommodation’ (Noy, Citation2017; Wireko & Béland, Citation2017). Conversely, the paper diverges from studies contending that the WB provides a well-defined reform blueprint and disregards national conditions (e.g. Cerami, Citation2006; Nemec & Kolisnichenko, Citation2006). The findings also show that the WB operates differently across policy sectors. For instance, in the pension sector, the WB pushed for a standardised three-pillar pension system (Orenstein, Citation2008).

The paper contributes to the growing literature on global social policy and provides a novel concept on how the WB formulates recommendations in healthcare financing policy. It advances the theory of policy bricolage, putting forth a novel definition and an analytical framework to measure policy bricolage in IOs’ policy recommendation making. In addition, the paper shows that there should be a more nuanced understanding of WC and post-WC and how they are used to define WB's impact.

Finally, it is worth noting some study limitations and possible avenues for future research. The paper was primarily based on document analysis. Further research, including additional methods such as interviews with national and IO stakeholders, and data, such as national documents, is needed to support the findings of the paper. Furthermore, future research should offer insights on this topic by focusing on different timeframes, countries/regions, and policy sectors. On a final note, the findings of the paper show adaptation and deviation from the WB's global reports on healthcare financing (e.g. Financing health services in developing countries and Investing in Health). This suggests a potential divergence in recommendations between WB's headquarters and its country offices. As a result, a promising avenue for future research would be to investigate and compare the extent of such divergence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ante Malinar

Ante Malinar is a doctoral researcher within the Collaborative Research Centre 1342, project B08 ‘Transformation of Health Care Systems in Central and Eastern Europe’, University of Bremen. He holds a master degree in political science from University of Zagreb. His research focuses on healthcare system reforms in Central and Eastern Europe and the role international organisations have in shaping healthcare policy.

Gabriela de Carvalho

Gabriela de Carvalho is a postdoctoral researcher within the Collaborative Research Centre 1342, project A04 ‘Global developments in health care systems', University of Bremen. She holds a doctoral degree in Economics and Social Sciences from the University of Bremen. Her current research focuses on comparative health care systems of the Global South and the role of global actors in shaping social policies.

Notes

1 The differences in the timeframe are due to WB membership: Argentina joined the WB in 1956, Croatia in 1993.

2 For a list of all analysed documents, see Appendix 1.

3 The analysed documents are cited according to the numbering system (Document Code) in Appendix 1, Tables and .

4 In addition to SHI, healthcare was partly financed by the government and county budgets (WHO, Citation1999).

5 The rationale behind this idea was to achieve better control over expenditure, debt collection, and management (Vončina et al., Citation2007).

References

- Allain, M., & Madariaga, A. (2020). Understanding policy change through bricolage: The case of Chile's renewable energy policy. Governance, 33(3), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12453

- Almeida, C. (2015). O Banco Mundial e as reformas contemporâneas do setor saúde. In J. M. Pereira, & M. Pronko (Eds.), A Demolição de direitos: Um exame das políticas do Banco Mundial para a educação e saúde (pp. 183–122). Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio.

- Alonso, V. (2003). Consumo de medicamentos y equidad en materia de salud en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 13(6), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892003000500009

- Arnaudo, F., Lago, F., & Viego, V. (2017). Assessing equity in the provision of primary healthcare centers in Buenos Aires Province (Argentina): A stochastic frontier analysis. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 15(3), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-016-0303-9

- Auyero, J. (2007). Routine politics and violence in Argentina: The gray zone of state power. Cambridge University Press.

- Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. Cornell University Press.

- Barrientos, A., & Lloyd-Sherlock, P. (2000). Reforming health insurance in Argentina and Chile. Health Policy and Planning, 15(4), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/15.4.417

- Bebek, S., & Santini, G. (2013). Hrvatska kao članica Europske Unije: Put u (Ne)poznatu Budućnost [Croatia as European Union member: Road to (Un)familiar future]. Ekonomija, 20(1), 1–28.

- Becerra, M. (2015). De la concentración a la convergencia. Políticas de medios en Argentina y América Latina. Paidós.

- Bernhardt, T. (2008). Dimensions of the Argentine crisis 2001/02. A critical survey of politico-economical explanations. Intervention: European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies, 5(2), 254–266.

- Bičanić, I., & Franičević, V. (2003, November). Understanding reform: The case of Croatia. GDN/WIIW Working Paper. The Wiiw Balkan Observatory. https://wiiw.ac.at/understanding-reform-the-case-of-croatia-dlp-3287.pdf

- Blake, C. H. (1998). Economic reform and democratization in Argentina and Uruguay: The tortoise and the hare revisited? Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs, 40(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/166198

- Bossio, J. C., Sanchis, I., Herrero, M. B., Armando, G. A., & Arias, S. J. (2020). Mortalidad infantil y desigualdades sociales en Argentina, 1980-2017 [Infant mortality and social inequalities in Argentina, 1980–2017]. Revista panamericana de salud publica=Pan American journal of public health, 44, e127.

- Busso, A. (2016). Neoliberal crisis, social demands, and foreign policy in Kirchnerist Argentina*. Contexto Internacional, 38(1), 95–131. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100003

- Cacace, M., Götze, R., Schmid, A., & Rothgang, H. (2008). Explaining convergence and common trends in the role of the state in OECD healthcare systems. Harvard Health Policy Review, 9(1), 5–16.

- Campbell, J. L. (2005). Where do we stand? Common mechanisms in organizations and social movements research. In G. F. Davis, D. McAdam, W. R. Scott, & M. N. Zald (Eds.), Social movements and organization theory (pp. 41–68). Cambridge University Press.

- Carstensen, M. (2011). Paradigm man vs. the bricoleur: Bricolage as an alternative vision of agency in ideational change. European Political Science Review, 3(1), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773910000342

- Carstensen, M. (2017). Institutional bricolage in times of crisis. European Political Science Review, 9(1), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773915000338

- Carstensen, M., & Matthijs, M. (2018). Of paradigms and power: British economic policy making since Thatcher. Governance, 31(3), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12301

- Cavagnero, E. (2008). Health sector reforms in Argentina and the performance of the health financing system. Health Policy, 88(1), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.02.009

- Cerami, A. (2006). Social policy in Central and Eastern Europe : The emergence of a new European welfare regime. Lit Verlag.

- Cerruti, G., & Ciancaglini, S. (1992). El óctavo círculo: Crónica y entretelones del poder menemista (3a ed). Editorial Planeta.

- Chen, M. S., & Mastilica, M. (1998). Health care reform in Croatia: For better or for worse? American Journal of Public Health, 88(8), 1156–1160. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.8.1156

- Cibils, A., Weisbrot, M., & Kar, D. (2002, September 3). Argentina Since Default: The IMF and the Depression. CEPR Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://www.cepr.net/report/argentina-since-default-the-imf-and-the-depression/

- Colonna, M. de la P. (2019). Los años 90 en la Argentina: Transformación y complejización del sindicalismo argentino. Revista de Investigación Del Departamento de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, 1(15), 57–78.

- Corrales, J. (2002). The politics of Argentina’s meltdown. World Policy Journal, 19(3), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1215/07402775-2002-4002

- Croatian Ministry of Health & World Bank. (2000). The reform of health care in Croatia. Revija za socijalnu politiku, 7(3), 311–325.

- Croatian Parliament. (2006). Nacionalna strategija razvitka zdravstva 2006. – 2011 [National strategy of healthcare development]. Narodne Novine, 72, 1–43.

- Deacon, B. (2007). Global social policy and governance. SAGE.

- de Carvalho, G., & Frisina Doetter, L. (2022). The Washington consensus and the push for neoliberal social policies in Latin America: The impact of international organisations on Colombian healthcare reform. In F. Nullmeier, D. González de Reufels, & H. Obinger (Eds.), International impacts on social policy: Short histories in global perspective (pp. 211–224). Springer International Publishing.

- Etchemendy, S., & Palermo, V. (1998). Conflicto y concertación. Gobierno, Congreso y organizaciones de interés en la reforma laboral del primer gobierno de Menem (1989–1995). Desarrollo Económico, 37(148), 559. https://doi.org/10.2307/3467412

- Fair, M. (2008). From population lending to HNP results : The evolution of the World Bank’s strategies in health, nutrition and population. World Bank.

- Finkelstein, J. Z., Duhau, M., & Speranza, A. (2016). Trend in infant mortality rate in Argentina within the framework of the Millennium Development Goals. Archivos argentinos de pediatria, 114(3), 216–222.

- Frisina Doetter, L., Schmid, A., de Carvalho, G., & Rothgang, H. (2021). Comparing apples to oranges? Minimizing typological biases to better classify healthcare systems globally. Health Policy OPEN, 2, 100035–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpopen.2021.100035

- García-Lema, A. (1994). La reforma por dentro: La dificil construcción del consenso constitucional. Editorial Planeta.

- Guerrero Espinel, E., Levcovich, M., Lima Quintana, L., Santich, I., & Jasín, M. (1999). Transformaciones del sector salud en la Argentina: Estructura, proceso y tendencias de la reforma del sector entre 1990 y 1997. Representación OPS/OMS Argentina, 48, 1–152.

- Hannah, A. (2020). Evaluating the role of bricolage in US Health Care policy reform. Policy & Politics, 48(3), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15734252004022

- Hochstetler, K. (2006). Rethinking presidentialism: Challenges and presidential falls in South America. Comparative Politics, 38(4), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.2307/20434009

- Johannes, L. (2007). Output-based aid in health: The Argentine maternal-child health insurance program. 11033. The World Bank Group.

- Kaasch, A. (2015). Shaping global health policy. Global social policy actors and ideas about health care systems. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kaminska, M. E., Druga, E., Stupele, L., & Malinar, A. (2021). Changing the healthcare financing paradigm: Domestic actors and international organizations in the agenda setting for diffusion of social health insurance in post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. Social Policy & Administration, 55(6), 1066–1081. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12724

- Kasapović, M. (2005). Koalicijske vlade u Hrvatskoj: prva iskustva u komparativnoj perspektivi [Coalition Governments in Croatia: First experiences in a comparative perspective]. In G. Čular (Ed.), Izbori i konsolidacija demokracije u Hrvatskoj [Elections and consolidation of democracy in Croatia] (pp. 181–209). Biblioteka Politička misao. Hrvatska politologija, 11. Fakultet političkih znanosti.

- Kovačić, L., & Šošić, Z. (1998). Organization of health care in Croatia: Needs and priorities. Croatian Medical Journal, 39(3), 249–255.

- Krogstad, E. (2007). The post-Washington consensus: Brand new agenda or old wine in a new bottle? Challenge, 50(2), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.2753/0577-5132500205

- Langenbrunner, J. C. (2002). Supplemental health insurance: Did Croatia miss an opportunity? Croatian medical journal, 43(4), 403–407.

- Levitsky, S., & Murillo, M. (2008). Argentina: From Kirchner to Kirchner. Journal of Democracy, 19(2), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2008.0030

- Lloyd-Sherlock, P., & Novick, D. (2001). “Voluntary” user fees in Buenos Aires hospitals: Innovation or imposition? International Journal of Health Services, 31(4), 709–728. https://doi.org/10.2190/0AKN-3N3E-3C9K-V3G5

- Lütz, S., & Kranke, M. (2014). The European rescue of the Washington Consensus? EU and IMF lending to Central and Eastern European countries. Review of International Political Economy, 21(2), 310–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2012.747104

- Machado, C. V. (2018). Health policies in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico: Different paths, many challenges [Políticas de Saúde na Argentina, Brasil e México: Diferentes caminhos, muitos desafios]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 23(7), 2197–2212. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018237.08362018

- Malinar, A. (2022). Anti-communist backlash in the Croatian Healthcare System. In J. J. Kuhlmannm, & F. Nullmeier (Eds.), Causal Mechanisms in the Global Development of Social Policies (pp. 239–270). Springer International Publishing.

- Mercado, R. (2007). The Argentine recovery: Some features and challenges. VRP Working Paper. https://explore.openaire.eu/search/publication?articleId=od_645::a6e406fa86d8b8674279ca0bb04c3141

- Misztal, B. (1992). Must Eastern Europe follow the Latin American way? European Journal of Sociology, 33(1), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600006391

- Myles, J., & Quadagno, J. (2002). Political theories of the welfare state. Social Service Review, 76(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/324607

- Nemec, J., & Kolisnichenko, N. (2006). Market-based health care reforms in Central and Eastern Europe: Lessons after ten years of change. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 72(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852306061611

- Nemec, J., & Lawson, C. (2008). Health care reforms in CEE: Processes. Outcomes and Selected Explanations, NISPAcee Yearbook, 1, 27–50.

- Niemann, D., Martens, K., & Kaasch, A. (2021). The architecture of arguments in global social governance: Examining populations and discourses of international organizations in social policies. In K. Martens, D. Niemann, & A. Kaasch (Eds.), International Organizations in Global Social Governance (pp. 3–28). Springer International Publishing.

- Nochteff, H. (2002). La experiencia argentina de los años 90 desde el enfoque de la competitividad sistémica. In T. Altemburg, & D. Messner (Eds.), America Latina Competitiva: Desafíos para la economía, sociedad y el estado (pp. 205–221). Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE); Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ); Nueva Sociedad.

- Noy, S. (2017). Banking on health: The World Bank and health sector reform in Latin America. Springer International Publishing.

- O’Donnell, G. A. (2008). Catacumbas (1 ed). Prometeo Libros.

- Ollier, M. M. (2001). Las coaliciones políticas en la Argentina: El caso de la Alianza (1a ed). Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Öniş, Z., & Şenses, F. (2005). Rethinking the emerging post-Washington consensus. Development and Change, 36(2), 263–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00411.x

- Orenstein, M. A. (2008). Privatizing pensions: The transnational campaign for social security reform. Princeton University Press.

- Polte, A., Haunss, S., Schmid, A., de Carvalho, G., & Rothgang, H. (2022). The Emergence of Healthcare Systems. In M. Windzio, et al. (Ed.), Networks and geographies of global social policy diffusion: Culture, economy, and colonial legacies (pp. 111–138). Springer International Publishing.

- Puljiz, V., Bežovan, G., Matković, T., Šućur, Z., & Zrinščak, S. (2008). Socijalna politika Hrvatske [Croatian Social Policy]. Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu.

- Radin, D. (2008). World Bank funding and health care sector performance in Central and Eastern Europe. International Political Science Review, 29(3), 325–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512107088392

- Ramet, S. P. (2013). Politika u Hrvatskoj od 1990. [Croatian politics since 1990]. In K. Klewing, R. Lukic, B. Marjanovic, & S. P. Ramet (Eds.), Hrvatska od osamostaljenja: rat, politika, drustvo, vanjski odnosi [Croatia since independence: War, politics, society, external relations] (pp. 33–59). Golden Marketing-Tehnicka Knjiga.

- Rubinstein, A., Zerbino, M. C., Cejas, C., & López, A. (2018). Making universal health care effective in Argentina: A blueprint for reform. Health Systems & Reform, 4(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2018.1477537

- Šarić, M., & Rodwin, V. G. (1993). The once and future health system in the former Yugoslavia: Myths and realities. Journal of Public Health Policy, 14(2), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/3342966

- Schmid, A., Cacace, M., Götze, R., & Rothgang, H. (2010). Explaining health care system change: Problem pressure and the emergence of “hybrid” health care systems. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 35(4), 455–486. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2010-013

- Schmitt, C. (2020). External actors and social protection in the Global South: An overview. In C. Schmitt (Ed.), From colonialism to international aid. External actors and social protection in the global south (pp. 3–18). Springer International Publishing.

- Schönfelder, B. (2013). Utjecaj rata na gospodarstvo [The influence of war on economy]. In R. Lukić, S. Ramet, & K. Clewing (Eds.), Hrvatska od osamostaljenja: rat, politika, društvo, vanjski odnosi [Craotia since independence: War, politics, society and external relations] (pp. 201–223). Golden Marketing-Tehnicka Knjiga.

- Stillwaggon, E. (1998). Stunted lives, stagnant economies: Poverty, disease, and underdevelopment. Rutgers University Press.

- Stubbs, P., & Zrinščak, S. (2007). Croatia. In B. Deacon, & P. Stubbs (Eds.), Social policy and international interventions in South East Europe (pp. 85–103). Edward Elgar.

- Tichenor, M., & Sridhar, D. (2017). Universal health coverage, health systems strengthening, and the World Bank. BMJ, 358, j3347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3347

- Tobar, F. (2002). Una reforma estructural del sistema de salud. Tram[p]as de La Comunicación y La Cultura, 7(1), 46–48.

- Tobar, F. (2010). ¿Qué aprendimos de las Reformas de Salud? Evidencias de la experiencia internacional y propuestas para Argentina. Fundación Sanatorio Güemes.

- Tobar, F. (2012). Breve historia del sistema argentino de salud. In O. E. Garay (Ed.), Responsabilidad Profesional de los Médicos. Ética, Bioética y Jurídica. Civil y Penal (pp. 1–19). La Ley.

- Vidučić, L. (2000). Progress in the Croatian transition and prospects for Croatia-EU relations. SEER: Journal for Labour and Social Affairs in Eastern Europe, 3(1), 47–64.

- Vončina, L., Džakula, A., & Mastilica, M. (2007). Health care funding reforms in Croatia: A case of mistaken priorities. Health Policy, 80(1), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.02.016

- Vončina, L., Kehler, J., Evetovits, T., & Bagat, M. (2010). Health insurance in Croatia: Dynamics and politics of balancing revenues and expenditures. The European Journal of Health Economics, 11(2), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-009-0163-4

- Weyland, K. (2006). Bounded rationality and policy diffusion: Social sector reform in Latin America. Princeton University Press.

- Wilensky, H. (1975). The welfare state and equality: Structural and ideological roots of public expenditures. University of California Press.

- Williamson, J. (1993). Democracy and the “Washington consensus”. World Development, 21(8), 1329–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(93)90046-C

- Wireko, I., & Béland, D. (2017). Transnational actors and health care reform: Why international organizations initially opposed, and later supported, social health insurance in Ghana. International Journal of Social Welfare, 26(4), 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12257

- World Bank. (1987). Financing health services in developing countries: An agenda for reform. World Bank Publications.

- World Bank. (1993). World development report 1993: Investing in health, Volume 1. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (1997). Health, nutrition and population sector strategy. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2008). Country partnership strategy for The Republic of Croatia for the period FY09-FY12. Report No. 44879-HR. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2023). World Bank open data. https://data.worldbank.org/

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Health financing. Retrieved April 26, 2023 from https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-financing#tab=tab_1

- World Health Organization. Regional office for Europe & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. (1999) Health care systems in transition: Croatia. WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Zrinščak, S. (2007). Zdravstvena politika Hrvatske. U vrtlogu reformi i suvremenih društvenih izazova [Croatian health policy. In the whirlwind of reforms and contemporary social challenges]. Revija Za Socijalnu Politiku, 14(2), 193–220.

Appendix 1.

Analysed documents

Table A1. Argentina.

Table A2. Croatia.