ABSTRACT

This article will provide an overview of how the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) project Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) has attempted to explore the use of interdisciplinary art-based practices for peacebuilding in Rwanda. In particular, we will detail how performance has been used to create a two-way system of communication between young people and policy-makers based on the issues that young people face towards developing an approach to teaching and learning informed by and with young people.

Introduction

This article will outline key stages in the co-production of challenge-led, art-based research to improve our understanding of the affective and effective engagement of children and youth in policymaking processes for peacebuilding in Rwanda. Art-based peacebuilding strategies have gained increasing attention as international agencies and local organisations utilise diverse cultural art forms for conflict transformation. We define art-based peacebuilding as an ‘artistic and creative practice that represents, responds to, seeks to transform or prevent the occurrence and negative impacts of conflict and violence’ (Hunter and Page Citation2014, 120). This includes the use of art for healing and reconciliation, promoting dialogue, preventing conflict, engaging marginalised communities, challenging injustices, and influencing policy (e.g. Cohen, Gutiérrez Varea and Walker Citation2011; Kanyako Citation2015; Pruit and Jeffrey Citation2020; Mitchell et al. Citation2020).

Between 2004–2012 in Rwanda, every community was mandated by law to attend the local level gacaca courts for the espoused objectives of justice and reconciliation in relation to the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda. During that time, the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission had tracked over 350 associations that were using art-based methods that aimed to create an alternative space to enable perpetrators, survivors and community members to live together after the wake of genocide (Breed Citation2014). The former Minister of Culture described this phenomenon as a kind of kugangahura or cleansing ritual. In numerous interviews with contributor Ananda Breed, association participants explained that art-based methods enabled kubabarira or an ability to understand ‘shared suffering’ between perpetrators and survivors. This initial research and in particular, the work of youth-led grassroots associations, inspired the development of the Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) research project. The term ‘mobile’ is to emphasise the importance of flexibility within the project to adapt to the varied socio-economic, political and cultural contexts of each country and communities where we work. The term ‘peace’ relates to ‘peace with oneself’ as a notion of wellbeing that has been more thoroughly explored by another UKRI GCRF Newton Fund project entitled Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) at Home: online psychosocial support through the arts in Rwanda (2020–2022) alongside the more generalised notion of positive peace as defined by Johan Galtung (Citation1969).Footnote1

We will provide a case study of MAP in Rwanda through the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project Ubwuzu (Joy): Shaping the Rwandan National Curriculum through Arts (2019–2020), followed by an analysis of the MAP project to inform teaching and learning in 25 MAP schools in Rwanda as delivered through a series of activities including curriculum workshops with cultural artists, training of trainers, youth camps, MAP clubs, and policy-informing events (Breed Citation2019). In particular, we will detail how performance has been used to create a two-way system of communication between young people and policy-makers based on the issues that young people face towards developing an approach to teaching and learning informed by and with young people.

In his pivotal paper, What Is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes, Ball (Citation1993, 13) commented on the relationship between power and policy:

Power is multiplicitous, overlain, interactive and complex, policy texts enter rather than simply change power relations. Hence again the complexity of the relationship between policy intentions, texts, interpretations and reactions.

As Bacchi (Citation2009) argues, policy can be utilised by the state to ‘produce problems’ with unconstructive representations of societal issues with no intention for critical consultation. The ‘WPR’ (What's the problem represented to be?) approach developed by Bacchi proposes six questions which are necessary for critical engagement in policymaking processes. This article will highlight question six:

How/where has this representation of the ‘problem’ been produced, disseminated and defended? How has it been (or could it be) questioned, disrupted and replaced? (Bacchi Citation2012, 21)

Applied theatre: effect vs affect

One of the main debates to have surfaced in recent years among researchers within applied theatre, performance, and drama education has been that between effect and affect (Freebody et al. Citation2020; Hughes and Nicholson Citation2015; Shaughnessy Citation2015; Thompson Citation2009). The early years of the practice which came to be known as applied theatre were characterised by an overwhelming concern with effect, frequently at the expense of any consideration of the aesthetics of theatre. In the hands of development agencies the genre was taken up as a means of producing ‘better’, that is, more effective, development outcomes. The sense of participation and excitement of creating theatre would be more likely to produce a commitment on the part of communities engaged through this process to the aims and objectives of the agency running the project. This was found to be especially true for non-literate societies for whom pamphlets and posters would have scant appeal. Even crude role-plays illustrating the benefits of pit-latrines or safe sex were an improvement upon a lecture from an NGO worker or nurse. The evaluation of these projects was conducted according to sociological metrics which had no room for theatrical perspectives and impact assessment was usually determined by changes to behaviour manifested outside any artistic context. Statistics about the number of participants and the lowering of instances of teenage pregnancy or vandalism tell us nothing about the effect of the theatrical experience upon participants and audiences.

This is the context into which James Thompson (Citation2009) was intervening with his call to pay attention to the affects of applied theatre and to which Michael Balfour (Citation2009) added with his notion of ‘small changes’ as opposed to the grand narrative of rehearsed revolution. If the theatre experience is of a high enough quality, participants will be affected in ways which are positive for their wellbeing and which may, directly or indirectly, produce an effect upon the situations in which they find themselves. This idea of the quality or nature of the performance producing affects can readily be extended to a variety of art forms such as dance, music, documentary video, radio, as well as pictorial or literary forms such as painting, drawing, photography, and poetry. We will be primarily focusing on performance in this article, although dance, music, film, visual arts and poetry was also integrated into the MAP project. Frequently underpinning the use of such forms is the personal story. Once we commit ourselves to telling our story to another, we become artists. We arrange events, decide what to suppress, what to highlight, which words best communicate. In other words, we take artistic decisions. Depending upon how effective the communication strategies are, we and our listener(s) will be more or less affected. When the basis for performance moves from an issue to a story, it becomes possible for the realities of lived experience to begin to determine the agenda for change. As the Control Chorus concludes in Brecht's play The Measures Taken, ‘taught only by reality, can reality be changed’ (Brecht Citation1977).

The question of how reality might be changed is seminal to the effect/affect debate. As more and more research into the neurological functions of the brain, enabled by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scanning, shows, we, as a species, are primed for action by the ways in which we are affected when we act or when we watch the actions of others (Bråten Citation2007). For action to be sustained and therefore, perhaps, change to occur, it is essential that we are so affected by our experience or by witnessing the experience of another that our whole emotional being requires changes, be these small personal ones or large political ones. However, if the artistic performance of individual stories is regarded as a fundamentally therapeutic process designed to make the performers feel better about themselves and their circumstances, it is unlikely that any sort of change will seep out into the wider world. The ‘problem’ will be located in the participant/artist/patient rather than in the inequalities, injustices, and inhumanities to which that person is being subjected (Pitruzzella Citation2017). Although the effect/affect debate has proved fruitful in stimulating ideas around what applied theatre is, once the terms become fossilised as binaries, they cease to represent the practice in ways that allow it to achieve its full potential. Applied theatre, like a tourist lying down across the equatorial line, has always been located on the boundary between development and art. Development only becomes sustainably effective if it engages those caught up in its processes affectively; if they feel an emotional commitment to ‘developing’ themselves. Applied art is only effective at the point when the sum of its affects leads to a process of change.

The MAP project is situated within the binary of this debate, focused on the knowledge and understanding of how local cultural forms and artistic approaches can be used as a tool to foster dialogue in post-conflict societies; primarily with and for young people. Art-based research methods are used to create an environment that supports the design and delivery of both an affective space for individuals and communities to share personal stories and to develop skills in facilitation, communication, conflict analysis, and a range of artistic disciplines (music, dance, drama, visual arts, filmmaking) alongside an effective space that engages a range of systems and structures to enable youth-based issues to be heard and addressed. Likewise, to inform teaching and learning in Rwanda through the development of curriculum materials, training of trainers, and employment of MAP participants as trainers and Master Trainers as part of MAP research initiatives.Footnote2

Background of youth engagement and policy in Rwanda

In tandem with applied theatre and how that relates to wider socio-political dynamics and policy, MAP has been positioned within wider youth engagement and education practices and the challenges inherent in such contexts. Developing effective policy engagement is complicated with a mixture of issues impacting on processes including political party interests, budget restrictions and inadequate resources. These issues are compounded when considering youth engagement in informing policy (Byrne and Lundy Citation2015, 18).

Irrespective of efforts to overcome issues affecting youth engagement, research has shown that problems such as adultism, lack of training, and exclusive processes continue to reduce possibilities of youth agency. Within the fields of childhood studies, critical psychology, and education, adultism refers to the idea that ‘adults are superior to children’ and young people are significantly disadvantaged by the dominance of adult-centric institutions in public life (Perry-Hazan Citation2016, 112; LeFrançois Citation2013). Adultism can lead to young people being patronised in processes leading to a tokenistic engagement of young people (Perry-Hazan Citation2016). In addition to the issue of adultism, the resources available to young people can be limited or exclusive, specifically in Global South contexts. From research on youth engagement in Malawi, it was found that youth policies were written in English as opposed to Chichewa which led to young people being left unaware of policy decisions or basic rights (Wigle, Paul, and Birn Citation2020, 384). Shier et al. (Citation2014, 10) also identified that there is an absence of training for young people to develop communication skills and relevant knowledge to have effective dialogue between young people and policy makers. The intersection of these issues lead to a context whereby young people are excluded from formal political processes as described by Byrne and Lundy (Citation2015).

In the Rwandan context, the Republic of Rwanda (Citation2015) outlines the Government's approaches and position of young people. With 69% of the population being aged between 0 and 30 years (African Institute for Development Policy Citation2020), the National Youth Policy identifies that young people are a ‘major asset’ and are the ‘key drivers of sustainable development’ (Republic of Rwanda Citation2015, 8). The National Youth Policy is wide-ranging with areas of focus including youth employment, youth and agriculture, and ‘youth delinquency’. Attention is focussed on outreach and engagement with proposals of bolstering the existing National Youth Council with extending reach to village level, ensuring youth representation at national and local levels (Republic of Rwanda Citation2015). In addition to this, Rwanda has developed the YouthConnekt initiative, a nationwide programme that focusses on ‘Youth Employability, Entrepreneurship and Civic Engagement’ (YouthConnekt Citation2021). With multiple strands including a national convention and mentorship opportunities, the programme has won international awards from the UN Development Programme and the African Union (YouthConnekt Citation2021). The success of the YouthConnekt programme has led to its adoption across the continent with sister programmes being developed including YouthConnekt Africa.

On a national level, Rwanda has advanced its efforts to engage young people in policymaking processes with an active Youth Council and programmes such as YouthConnekt. However, common issues surrounding youth engagement persist in Rwanda. USAID (Citation2019, 2) argue that there are still issues surrounding adultism in Rwanda with young people wanting to see more youth-led initiatives and a re-envisaging of the role of adults in youth engagement. In tandem with this, a range of economic and social barriers restrict young people from accessing education and employment opportunities which leads to disillusionment with wider social and political activities (USAID Citation2019). The relationship between economic development and civic development is intertwined when considering aspects of youth civic engagement in Rwanda. Young people have not necessarily benefitted from the rapid social and economic development that has taken place in Rwanda which leads to young people experiencing a range of uncertainties and hardships (Grant Citation2014, 106). A disillusionment with formal political processes has led to youth engagement being focussed on issue-based campaigning and mediums such as popular music being used to engage young people in civic action (Never Again Rwanda Citation2019; Grant Citation2014).

Taking into account the country context and debates surrounding both applied theatre and youth engagement, MAP's approach to policymaking focusses on building from the bottom-up. Its research data include the stories and lived experiences of the young people who serve as the primary research participants. In accordance with Article 13 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx), participants choose the means of expression with which to articulate their experience; in the case of MAP, through music, dance, drama, visual arts and filmmaking. Since the inauguration of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) there has been some impact upon the applied arts and education sectors (Boon and Plastow Citation2004; Etherton Citation2004, Citation2006; Etherton and Prentki Citation2006; Prentki and Abraham Citation2021). Perhaps because the CRC emanates from the UN there has been a tendency to affiliate it with the development sector, rather than as a key enabler of young people's access to arts processes as a right. The CRC is a two-way process; the right to access art and culture but also regarding how arts enable access to rights. Due to the way in which MAP has been established in collaboration with the Rwanda Education Board (REB), schools and civil society organisations, there have been changes both to the content of the curriculum and approaches to teaching and learning alongside the inclusion of young people into the developmental and accumulative affects and effects of MAP on local and national levels. Affects on a personal level have the opportunity to become effects related to the design and delivery of Music, Dance and Drama and the potential impact on informing policy through youth-led, art-based initiatives.

Networks, systems, and structures

Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) emerged as part of the Phase One activities of a project entitled Changing the Story: Building Inclusive Societies with and for Young People in 5 Post-Conflict Countries (2017–2021).Footnote3 This project was focused on working alongside civil society organisations to consider some of the varied opportunities to research the use of participatory arts for youth-centred approaches to civil society building in post-conflict societies. As Co-Investigator of this project, Breed conducted an initial mapping of civil society organisations using art-based approaches with and for young people and implemented a series of activities to research how the arts could be used to inform the national curriculum for the subject of Music, Dance and Drama in response to an explicit need evidenced by a 2017 UNESCO report and interviews, focus groups and surveys.Footnote4 The primary networks incorporated into the project included cultural organisations (Rwanda Film Centre, Mashirika), civil society organisations (Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace, Aegis Trust, Never Again Rwanda), higher education institutions (University of Rwanda), schools (25 schools located in the five provinces), governmental organisations (Rwanda Education Board), and local authorities. Due to formal and informal structures of communication and governance in Rwanda that operate from a village, cell, district, sector, and province level, the MAP project aimed to co-produce and deliver the project from the bottom-up.Footnote5

Activities included an initial scoping visit to map the varied youth-led, art-based initiatives being conducted by CSOs alongside a curriculum workshop conducted with 10 cultural organisations to explore the use of art-based approaches to support dialogue with and for young people. Based on initial findings, a residential week-long Training-of-Trainers (TOT) was conducted with educators from five schools in the Eastern Province of Rwanda. Educators were selected from a range of schools including non-governmental organisation schools, government schools, private schools, and schools in both rural and urban settings. During the TOT, educators further developed the teaching and learning resources by integrating Rwandan art-based exercises with a focus on building dialogue, adjusting existing MAP exercises into the cultural context of Rwanda, and translating the MAP manual into Kinyarwanda. Primarily, the workshops were conducted in Kinyarwanda with a focus on supporting the development of educators to serve as facilitators for the subsequent youth camp. During the week-long residential youth camp training, the youth participants were trained to serve as facilitators to co-facilitate alongside the adult facilitators and to serve within a leadership capacity within school-based MAP clubs.

As a leading civil society and research organisation for MAP in Rwanda, the Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace (IRDP) brokered an initial Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with REB to develop the curriculum to inform the subject of Music, Dance, and Drama. Local authorities were notified of the project through letters and field visits, then cultural organisations and schools were contacted based on their possible affiliation with the aims of the project. Heads of Schools selected educators who would serve as MAP trainers within their schools and communities, and educators selected young people who demonstrated leadership qualities to develop the MAP clubs. Adult educators and youth facilitators who served as research participants eventually facilitated MAP activities as Master Trainers for subsequent workshops. The MAP project was situated within an overarching administrative structure that served to inform education policy. In terms of the ability of MAP to scale up from regional (Eastern Province) to national coverage (Eastern Province, Western Province, Northern Province, Southern Province, and Kigali City), it was important to implement the project in conjunction with overarching administrative structures and to consider some of the existing policies and practices to further support the national curriculum through additional resources and trainings that relied on combined support mechanisms between local and regional structures.

Additionally, it is important to note the longitudinal nature of the work. The MAP project was initially piloted as part of the Changing the Story (2017–2021) project, later to be provided follow on impact funding to extend the research from the Eastern Province of Rwanda to the remaining four provinces through the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) follow on funding of Ubwuzu (2019–2020)Footnote6 and eventually to being funded to explore art-based practices in Kyrgyzstan, Rwanda, Indonesia, and Nepal through AHRC Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) Network Plus project Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP): Informing the National Curriculum and Youth Policy for Peacebuilding in Kyrgyzstan, Rwanda, Indonesia and Nepal (2020–2024).Footnote7 Due to the close association with civil society organisations and government institutions, MAP was able to deliver a GCRF Newton Fund rapid response project to address mental health service delivery during the pandemic entitled MAP at Home: online psychosocial support through the arts in Rwanda (2020–2021).Footnote8 As a result, there is evidence to support the need for both top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal approaches to co-produce projects that address existing needs as articulated by project partners, stakeholders, and research participants. Young people who originally served as research participants in the Changing the Story project served as facilitators for the Ubwuzu project and then as Master Trainers for the MAP at Home project illustrating capacity building and leadership development as core to the methodology and longitudinal design and delivery of MAP.

Story circle: disability

The MAP approach focuses on the stories and issues of young people; providing varied artistic structures for narratives to emerge and to further explore the root causes and solutions to proposed problems that young people experience through story circles, conflict analysis, performance and dialogue with relevant stakeholders. We will focus on the issue of disability to illustrate how a personal story transforms to a community or archetypal story, to then analyse the varied issues related to the story regarding the effects on young people and to propose solutions, mapping the journey from the personal story to policy informing structures that have been put in place to communicate issues to a wider audience. MAP informs policy through an approach that enables young people to communicate their issues through art-based modes and develops a network between civil society organisations, local authorities, schools, and policy-making bodies. We will provide an overview of two stories that were shared during a MAP exercise called story circle based on the theme of disability, the play that was produced based on the story, and the workshop and policy brief that was designed to engage policymakers.

Story circle usually takes place on day three of a week-long MAP residential training. Leading up to the story circle, participants hone their skills in active listening, understanding, and embodying the story of another, sharing their regional and cultural forms, and considering different viewpoints on a range of topics and debates. Individuals share their feelings, thoughts and ideas through games, images, songs, dances, and drawings. There are resident psychosocial workers who pay special attention to group dynamics, safeguarding, and to any emotional and psychological reactions from the activities. There is a strategic building up of trust among the group and increased self-awareness that leads to the story circle. The facilitator begins by noting that we aim to address community issues by first exploring our own stories based on a time in which we had a goal or objective but were faced with obstacles that inhibited our ability to achieve the goal. The participants are guided to consider these stories in relation to community-based problems that they would like to solve. During the youth camp residency in Rwanda, there were up to eight story circles with up to seven young people and up to three adult trainers that included psychosocial workers and MAP staff in each story circle.

The story circle that focused on the theme of disability in two out of the 10 stories started with the narrative of a family who raised a child with disabilities. One day, there was a visitor. During the visitation, the child was hidden in the toilet. When the child was discovered, the parent did not claim the child. The visitor took the child and provided treatment. When the child was returned, the parent asked for forgiveness. The second story relates to a disabled boy who was raised by an alcoholic parent. He was sent to live with a family member. He was mistreated, bullied at school and eventually dropped out of school to serve as a house boy for his family. He was repeatedly beaten until he eventually shared his story with a neighbour who consulted the police. He is now studying but struggling with life. In both of these stories, the disabled young person has been mistreated within the family due to neglect, shame, poverty, and alcoholism. There is some indication of outside support and structures (neighbours, extended family members, school, police), but indications that mechanisms for safeguarding, reporting, and protecting vulnerable children may be missing. Additionally, a number of stories were shared during story circle that indicated immediate family members were often the cause of sexual and domestic violence. In this case, there are numerous taboos against speaking out or voicing the experiences of young people for fear of varied repercussions. In MAP, the members of the story circle express their appreciation to each other for sharing their stories and additional counselling and one-to-one support is given by the psychosocial workers. The participants select a story from the circle that they think would best demonstrate a community issue that they’d like to explore. In the case of this story circle, the group decided to select the issue of disability, but further fictionalised the story and added additional information to best represent some of the varied issues that face children with disabilities and to anonymise the teller. After the teller gives permission to use the story, the transformation of the personal story to the community story is crafted through a series of exercises including a ‘hot seat’ exercise in which the participants ask clarifying questions of the teller to better understand the situation and root causes to the problem, followed by the creation of frozen images to represent the story through five freeze-frames, and the improvisation of dialogue to develop the script.

Nkore Iki? (What can I do?)

The play depicts the plight of a young man, Kalisa, who has experienced stigmatisation since childhood. The preface to the play, written by MAP Master Trainer Fred Kabanda based on a production devised by MAP youth participants, notes that due to his disability, Kalisa is perceived as being someone who brings misfortune to his family and village. In the church and religious institutions, he is deemed as cursed by God. In relation to leadership, Kalisa is perceived as useless, someone who can't support the development of the community and the country in general.

Extracts from Scene One illustrate underlying reasons for the discrimination against Kalisa:

Everyone in my church can remember how I prayed for the sick and they were healed, right? That is why they believed in me and gave us money to build our beautiful house. Now the members of our church are coming to visit us, you have been asking why I don’t want to stay near my church with my family, but I ignore you …

I see a problem now; we are in trouble!

What is the problem? God is on our side. Remember the book of Psalms 91:5-7 ‘thou shall not be afraid for the terror by night nor by the arrow that flies by day nor by the pestilence that walks in darkness nor for the destruction that wastes at noon day a thousand shall at the sides and ten thousand at your right hand but it shall not come near you’. Now, have you started to doubt?

Not at all, but our child Kalisa is a very big problem!

How and why are you saying that?

As I told you earlier, the whole congregation knows that we are holy and servants of God. They know that we talk to God and ask him to do everything. Now they are going to find our own child is like that … what do you think will follow? We shall lose our believers who will call us liars and scammers. We are going to look like fools and pagans before them! That is why I have decided to hide him.

Creating spaces for children, young people and policy engagement

Central to the MAP approach is the creation of spaces for dialogue between young people and policy actors, whether those responsible for enacting policy in schools or communities (such as head teachers or local leaders) or those working on policy at national level in ministries (for example). We used two principal approaches for the creation of dialogue, namely MAP games and exercises and policy briefs. Performance was used in relation to the use of theatre to illustrate the problems that a community may face in order for the audience to resolve the problem. The MAP approach includes a range of games and exercises to enable the young people to share their stories, to analyse the conflict issues and perform their stories that incorporates local cultural forms that are adapted for dialogic purposes.

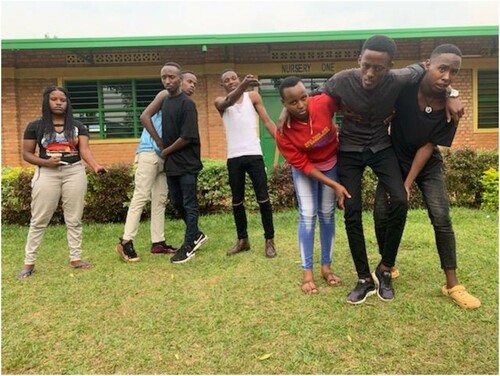

Policy briefs are often technical documents, written by those with highly specialised professional expertise and offer either a series of possible courses of action or recommendations to decision-makers. During the youth camp held in November 2019, we experimented with an approach to the creation of policy briefs, which built on key components of the MAP methodology including art-based methods (drawings and images), dialogue (performance and participatory action research methods) and conflict analysis tools. Crucially, the approach taken enabled the knowledge and perspectives of young people with lived experiences of the issues discussed to inform the curating of the briefs. The briefs aimed to be both evidence-based and art-based by incorporating the chosen story from the story circle used for the creation of the performance, as well as the obstacle tree activity to identify the root causes of the problem represented and frozen images that were developed further into a performance. Following the performance, the youth participants, supported by adult facilitators created a solution tree, based on the dialogue that emerged following the performance and created a series of recommendations for children and youth, families and communities, institutions and organisations, and government. In the supplementary material of this Special Issue is an example of the policy brief that accompanied the play on discrimination towards children with disabilities, explored in the previous section. Briefs were also produced on the following topics: child abuse; listening to children's needs in the family; child domestic workers; and teenage pregnancy ().

During a dissemination event in August 2020 held at IRDP in Kigali, the young people performed the play on disability and presented the policy brief to policy actors to serve as a basis for further dialogue.Footnote9

The MAP approach challenges dominant social constructions of children and childhood, in international policy discourses, as well as at the national level in Rwanda, whereby children are frequently situated as ‘the future’ (Pells, Pontalti, and Williams Citation2014; Benda and Pells Citation2020). Instead, of positioning young people as future leaders or future policy makers, children's knowledge and perspectives in the present underpin the whole process of knowledge generation and dialogue. Throughout the project teachers, community members and policy makers reflected on the sophistication of children's critical analysis of social problems and their creativity in identifying possible solutions. At the dissemination event, a representative from REB observed how the MAP approach aligned with the new Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC) stating: ‘you do not consider students as empty vessels but you consider how they can produce their own content’.

A key critique levelled at participatory processes, particularly as adopted within policy and programming development, is that these processes can be seen as ‘tick box’ exercises; something which is important to be seen to be done, rather than an opportunity to truly learn (Tisdall Citation2015). This dilutes the transformational potential of participatory approaches to enable the creation of new knowledge and practices and to challenge normative assumptions and power relations (Gallacher and Gallagher Citation2008). In terms of adultism, traditional adult–child power relations position the adult as the expert, the child as the learner and unless these are negotiated, challenged and reworked, these relations of power act as a barrier to the participation of children, since children will be seen (and may act) as present to listen and learn, not express and share. Within MAP we have found that performance has been an effective tool to create a space for dialogue between young people and adults, given the ways in which the model challenges traditional power dynamics, with the children and young people serving as actors and so the audience watches the story unfold from the perspective of the children. The structure of performance, in which a facilitator actively engages the audience to respond to the issues represented, was also one which encourages deeper dialogue.

At the same time there is potential for performance and the ensuing dialogue to reproduce social norms and inequalities of power, particularly when there is limited time for the problematisation of audience interventions (Elliott Citation2019). In the example of discrimination experienced by a child with disabilities, the subsequent dialogue was one that created new understandings among the adult audience. However, the extent to which the dialogue was transformational rested on the story that was initially told and how it was explored but told in another way might actually reinforce existing ways of thinking and doing. It is sometimes assumed that participation in and of itself will yield new, and possibly more progressive, perspectives, but those engaging in these processes are themselves part of communities with strong existing norms and challenging these may be difficult (even if people wish to) and so stories chosen can end up reinforcing as much as challenging these norms. Another instance of a performance produced during the Training-of-Trainers workshop in August 2019, told the story of an orphaned girl who was preyed upon and raped at school by a male head teacher. The dialogue that emerged from some of the participating educators focused on what the girl could have done differently and of having CCTV cameras at school, and not on the root causes of gender-based violence. However, the discussion was facilitated to bring out other perspectives and differing viewpoints. Therefore, the way in which workshops and performances are facilitated is important. The role of the facilitator to address different perspectives is central. Additionally, the importance of exercises used in MAP including Conflict Tree is necessary to further explore the root causes to varied conflicts. The stakeholders should also include researchers and representatives from varied organisations who can help to address the necessary structures for change to occur. Within the workshop and performance structures, it is necessary for the artistic form to engage with social representations in order to question assumptions and embedded stereotypes. However, this is reliant on highly crafted facilitation skills. Within MAP, there is the continued training of participants as facilitators and the use of the experiential learning model (Kolb Citation1984) in order to process exercises and for individuals and groups to provide feedback (which also serves as monitoring and evaluation) in relation to: experiencing (What happened? What did you feel?); publishing (What were your observations and any patterns of behaviour that emerged?); processing (What is your response to some of these observations and behaviours?); and generalising (What can we conclude and how might we apply this knowledge and understanding to our work as facilitators or to the application of MAP in our communities?). MAP does not take a didactic or agit prop approach to exploring the problems that young people experience, but rather engages young people and relevant power structures and allies (REB, schools, health centres, CSOs, research institutions) to address issues using an experiential, exploratory and dialogic approach.

Finally, a key strength of the MAP approach is to enact the personal as political to move from personal transformation to social transformation. The former Director General from REB, Sebaganwa Alphonse, has praised the work of MAP in a testimonial based on the research conducted by Breed stating:

In relation to her work with REB, Breed has sought to serve an existing need; to inform the National Curriculum in the subject of Music, Dance and Drama alongside Peace Education. Breed's research and sustained practical training of teachers across all five provinces of Rwanda has had a profound effect on the teaching and learning environment of participants. Young people have increased their self-confidence and motivation to learn … research and practice conducted by Breed for REB has created participatory methodologies for conflict prevention in Rwanda; supported new extra-curricular opportunities for young people and integrated participatory practices as a method of teaching and learning; and contributed to conflict prevention strategies and problem solving in partnership with key stakeholders. Through using art-based techniques, which encourage dialogue and foster trust and communication, participants from formerly antagonistic groups have been able to work together to create conflict prevention strategiesFootnote10

Conclusion

This project offers a concrete example of the ways in which affect and effect, rather than being considered antagonistic components of applied arts processes, are invaluable companions on the journey from personal transformation to social change. The springboard or energy for the trajectory of the project arose from the way in which story-tellers, listeners and participants in the subsequent dramas were affected by the performance aesthetics. However, those initial affects would have been dissipated to the point of frustration and futility were it not for the network of relations into which those affects were channelled in order to be developed into effective strategies for sustained and sustainable changes to the ways in which young people in Rwanda contribute to attempts to create a more just and peaceful society.

In an evaluation interview, a young MAP master trainer said the following when discussing the personal and political impact of MAP projects:

I will not sit down and say it is ok. I have to fight, I have to fight for young people's wellbeing … so, they can be free of their problems, share their problems and share what to do as a means of advocacy.

The debate surrounding affective and effective practices in applied performance, discussed earlier, has been represented throughout this paper. The opportunity for a fluid and dialogical relationship, as opposed to a binary discussion, between affect and effect is possible and has proved to be a strength in art-based policymaking processes in the MAP project. Drawing on Ganguly's description of the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ revolution, theatre plays the role of ‘connecting collective action with introspective action’ (Ganguly Citation2010, 127). But, Ganguly (Citation2010, 77) is also explicit that an ‘internal’ affective process must take place first before beginning to envisage concrete effects of applied performance. Whilst the MAP project is not following this process there are parallels with young trainers describing deep personal changes, especially in relation to story sharing, which has led to political agency. The testimony of the young MAP master trainer above is one example of this.

Whilst the successes of MAP as a two-way communication between young people and policy makers are outlined in this article, there is an understanding that such practice is not always replicable or follows similar processes. Matters of cultural context and a particular epoch play a significant role but as Ball (Citation1993) states the power relations in policymaking are complex and multiplicitous therefore providing an unpredictable and precarious nature to art-based policymaking processes. The multiple and complex nature of power relations therefore affords the possibility both for opening up as well as shutting down spaces for youth engagement. At the time of writing, MAP Rwandan partner organisation IRDP and MAP researchers and youth and adult master trainers (as part of the project design) were awarded further funding to continue youth engagement with policy-makers through a United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF) project entitled Promoting Youth Engagement with Policy-makers through Performing Arts in Rwanda (2022–2024).Footnote11 The project aims to build the capacity of youth to document and share issues and for policymakers to respond to young people and enhance local participatory governance and conflict transformation. Additionally, MAP has developed a Continuing Professional Development (CPD) programme for the subject of Music, Dance and Drama in partnership with the University of Rwanda (UR) to embed art-based approaches to teaching and learning into the Competency-Based Curriculum and another CPD programme in partnership with the School of Medicine at UR to integrate the MAP at Home approach into mental health service training and delivery. Thus illustrating the ongoing use of performing arts and the MAP methodology to activate and engage with policy and governance structures to create sustainable and meaningful change with and for young people.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank MAP team researchers and staff members who contributed to the Ubwuzu project including Eric Ndushabandi, Sylvestre Nzahabwanayo, Chaste Uwihoreye, Laure Iyaga, Gisele Sandrine Irakoze, and Kurtis Dennison; MAP master trainers including Fred Kabanda, Esther Musabyimana, Germain Mbona, Florence Nyiransengiyumva, Jean Claude Ngaboyabahizi, and Jean Marie Vianney Ntawirema; MAP youth master trainers including Jeanette, Elia, Dorcas, Erick, Leonard, Sandrine A, Sandrine U, Assia, Samuel, and Reuben; and cultural artists including Rukundo Jean Baptiste, Alexandre Iteriteka, and Deus Kwizera. Additionally, to thank all of our partnering organisations including Rwanda Education Board and the teachers and students from participating schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ananda Breed

Ananda Breed is a Professor of Theatre at University of Lincoln. She is author of Performing the Nation: Genocide, Justice, Reconciliation (2014), co-editor of Performance and Civic Engagement (2018), co-editor of Creating Culture in Post-Socialist Central Asia (2020), and co-editor of The Routledge Companion to Applied Performance: Volume One & Two (2020).

Kirrily Pells

Kirrily Pells is an Associate Lecturer in Childhood at University College London. Her work concerns global childhoods and children’s rights especially in relation to poverty, intersecting inequalities, and violence. Her PhD focused on the lives of children and young people in the aftermath of conflict, with a case study of Rwanda.

Matthew Elliott

Matthew Elliott is a Wellcome Trust ISSF Fellow at University of Leeds. After training at the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, he worked collaboratively with a range of companies including Collective Encounters (UK), Colectivo Sustento (Chile), and Lagnet (Kenya).

Tim Prenti is Emeritus Professor of Theatre for Development at University of Winchester. He is co-editor of The Applied Theatre Reader (2008), author of Applied Theatre: Development (2015), and The Fool in European Theatre: Stages of Folly (2011), co-editor of Performance and Civic Engagement (2018), and co-editor of The Routledge Companion to Applied Performance: Volume One & Two (2020).

Notes

1 For further information about the use of MAP for psychosocial support during COVID-19 in Rwanda, please see journal article ‘Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) at Home: Digital Art-based Mental Health Provision in response to COVID-19’ Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 13 (1).

2 Trainers are trained in the MAP methodology in a week-long residential training intensive. Following initial training, the trainers are paid to facilitate subsequent training of trainers, youth camps, and other workshops. As part of additional MAP related projects including Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP): Informing the National Curriculum and Youth Policy for Peacebuilding in Kyrgyzstan, Rwanda, Indonesia and Nepal, six Rwandan Master Trainers led a week-long workshop for ten lecturers from the University of Rwanda to further embed MAP into the National Curriculum Framework by developing bespoke units that could be included into the curriculum. Additionally, Co-I Sylvestre Nzahabwanayo is leading the developing of a CPD programme using the MAP approach. For GCRF Newton Fund project MAP at Home: online psychosocial support through the arts in Rwanda, six adult Master Trainers and nine youth Master Trainers were employed to deliver online participatory arts workshops alongside psychosocial workers for the provision of mental health support during the time of COVID. The MAP manual has been written in Kinyarwanda and English and the workshops are primarily conducted in Kinyarwanda. Due to the affective nature of the projects and context of Rwanda, psychosocial workers have also been integrated into all stages of the design and implementation of MAP in partnership with Sana Initiative and Uyisenga Ni Imanzi. For further information about MAP Network Plus, please see the following website: https://map.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk For MAP at Home, please see the following project website: https://map.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/map-at-home/.

3 For further information about Changing the Story, see the project website: https://changingthestory.leeds.ac.uk.

4 For further information about the MAP methodology and Phase One activities for Changing the Story, see Breed A 2019 ‘Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP): Youth and participatory arts in Rwanda’ Participatory Arts in International Development. (eds) Paul Cooke & Inés Soria-Donlan, Routledge.

5 For further information about the administrative structures in Rwanda, please see: https://www.gov.rw/government/administrative-structure [accessed 1 June 2021].

6 Ubwuzu worked in partnership with Eric Ndushabandi from the Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace (IRDP) and 25 participating schools; five schools in each of the five districts in Rwanda. Laure Iyaga from Sana Initiative and Chaste Uwihoreye from Uyisenga Ni Imanzi served as the resident psychosocial workers and Uwihoreye was the safeguarding lead. Kirrily Pells from University College London led participatory action research workshops and Sylvestre Nzahabwanayo from University of Rwanda served as a researcher and delivered a final impact report that was conducted through interviews, surveys and focus groups with research participants. Ananda Breed from University of Lincoln served as the Principal Investigator and led the development of the curriculum, training of trainers, and design and delivery of the scoping visit, curriculum workshop, training of trainers, and youth camp. The project involved all of the above noted individuals throughout the process with a focus on co-production.

7 The MAP Network Plus project includes 8 Co-Investigators (Kirrily Pells, UCL; Koula Charitonos, Open University; Tajyka Shabdanova, FTI; Harla Sara Octarra, Atma Jaya Catholic University; Rajib Timalsina, Tribhuvan University; Bishnu Khatri, Human Rights Film Centre; Eric Ndushabandi, IRDP; Sylvestre Nzahabwanayo, University of Rwanda; and 23 partnering organisations. Ananda Breed from University of Lincoln serves as the Principal Investigator.

8 For more information about MAP at Home, please see Breed et al. (Citation2022).

9 Please see related blog: https://map.lincoln.ac.uk/2020/08/27/arts-based-methods-and-digital-technology-for-peacebuilding-during-the-time-of-covid/

10 Testimony letter from Dr Sebaganwa Alphonse, the Director General of the Rwanda Education Board, 26 January 2021.

11 For more information, please see the IRDP website: https://www.irdp.rw/promoting-youth-engagement-with-policy-makers-through-performing-arts-in-rwanda/

References

- African Institute for Development Policy. 2020. Regional Analysis of Youth Demographics: Rwanda. (Online) Accessed 16 May 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5af954b2e5274a25dbface35/Rwanda_briefing_note__Regional_Analysis_of_Youth_Demographics_.pdf.

- Bacchi, C. 2009. ‘Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to be?’ Approach. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education.

- Bacchi, C. 2012. “‘Introducing the ‘What’s the Problem Represented to Be?’ Approach’.” In Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic Interventions and Exchanges, edited by Angelique Bletsas, and Christine Beasle, 21–24. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press.

- Balfour, M. 2009. “The Politics of Intention: Looking for a Theatre of Little Changes.” Research in Drama Education 14 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1080/13569780903072125.

- Ball, S. J. 1993. “What Is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 13 (2): 10–17. doi:10.1080/0159630930130203.

- Benda, R., and K. Pells. 2020. “The State-as-Parent: Reframing Parent-Child Relations in Rwanda.” Families, Relationships and Societies 9 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1332/204674319X15740695651861.

- Boon, R., and J. Plastow. 2004. Theatre and Empowerment: Community Drama on the World Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bråten, S., ed. 2007. On Being Moved: From Mirror Neurons to Empathy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. doi:10.1075/aicr.68

- Brecht, B. 1977. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Breed, A. 2014. Performing the Nation: Genocide, Justice, Reconciliation. Chicago: Seagull Books.

- Breed, A. 2019. “Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP): Youth and Participatory Arts in Rwanda.” In Participatory Arts in International Development, edited by Paul Cooke, and Inés Soria-Donlan, 124–142. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Breed, A., and T. Prentki. 2017. Performance and Civic Engagement. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-66517-7_11

- Breed, A., C. Uwihoreye, E. Ndushabandi, M. Elliott, and K. Pells. 2022. “Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) at Home: Digital Art-based Mental Health Provision in Response to COVID-19.” Journal of Applied Arts and Health 13 (1): 77–95. doi:10.1386/jaah_00094_1.

- Byrne, B., and L. Lundy. 2015. “Reconciling Children’s Policy and Children’s Rights: Barriers to Effective Government Delivery.” Children and Society 29 (4): 266–276. doi:10.1111/chso.12045.

- Byrne, B., and L. Lundy. 2019. “Children’s Rights-based Childhood Policy: A six-P Framework.” The International Journal of Human Rights 23 (3): 357–373. doi:10.1080/13642987.2018.1558977.

- Cohen, C., R. Gutiérrez Varea, and P. O. Walker. 2011. Acting Together Performance and the Creative Transformation of Conflict. Oakland, CA: New Village Press.

- Elliott, M. D. 2019. “Embodying Critical Engagement - Experiments with Politics, Theatre and Young People in the UK and Chile.” PhD diss. University of Leeds.

- Etherton, M. 2004. “South Asia’s Child Right Theatre for Development: The Empowerment of Children who are Marginalised, Disadvantaged and Excluded.” In Theatre and Empowerment: Community Drama on the World Stage (Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre) edited by Richard Boon, and Jane Plastow, 188–219. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Etherton, M. 2006. African Theatre: Youth. Oxford: James Currey.

- Etherton, M. 2021. “Child Rights Theatre for Development with Disadvantaged and Excluded Children in South Asia and Africa.” In The Applied Theatre Reader, edited by Tim Prentki, and Nicola Abraham, 272–277. London & New York: Routledge.

- Etherton, M., and T. Prentki. 2006. “Drama for Change? Prove it! Impact Assessment in Applied Theatre.” Research in Drama Education 11 (2): 139–155. doi:10.1080/13569780600670718.

- Freebody, K., M. Balufour, M. Finnernan, and M. Anderson. eds. 2020. Applied Theatre: Understanding Change. Cham: Springer.

- Freire, P. 1996. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin.

- Gallacher, L. A., and M. Gallagher. 2008. “Methodological Immaturity in Childhood Research?: Thinking Through `Participatory Methods’.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 15 (4): 499–516.

- Galtung, J. 1969. "Violence, Peace, and Peace Research." Journal of Peace Research 6 (3): 167–191.

- Ganguly, S. 2010. Jana Sanskriti – Forum Theatre and Democracy in India. London: Routledge.

- Grant, A. 2014. “‘Bye-bye Nyakatsi’: Life Through Song in Post-Genocide Rwanda.” Moving Worlds 14 (1): 105–118.

- Hughes, J., and H. Nicholson. 2015. Critical Perspectives on Applied Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hunter, M. A., and L. Page. 2014. "What is 'The Good' of Arts-Based Peacebuilding? Questions of Value and Evaluation in Current Practice." Peace and Conflict Studies 21: 117–134.

- Kanyako, V. 2015. "Arts and War Healing: Peacelinks Performing Arts in Sierra Leone." African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review 5 (1): 106–122.

- Kolb, D. A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- LeFrançois, B. A. 2013. “Adultism.” In Encyclopaedia of Critical Psychology: Springer Reference, edited by T. Teo, 47–49. Berlin: Springer.

- Mitchell, J., G. Vincett, T. Hawksley, and H. Culbertson. 2020. Peacebuilding and the Arts. Manchester: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Never Again Rwanda. 2019. Engaging Youth in Building an Equal and Inclusive Society. (Online) Accessed 21 May 2021. https://neveragainrwanda.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/INZIRA-NZIZA-TRAINING-MANUAL-2019-26-Apr.pdf.

- O’Connor, P. and B. O’Connor. 2018. “Hearing Children’s Voices: Is Anyone Listening?” In: Applied Theatre: Understanding Change edited by Kelly Freebody et al., 135–152. New York: Springer.

- Pells, K., K. Pontalti, and T. P. Williams. 2014. “Promising Developments? Children, Youth and Post-Genocide Reconstruction Under the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8 (2): 294–310.

- Perry-Hazan, L. 2016. “Children’s Participation in National Policymaking: ‘You’re so adorable, adorable, adorable! I’m speechless; so much fun!’.” Children and Youth Services Review 67: 105–113.

- Pitruzzella, S. 2017. Drama, Creativity and Intersubjectivity. London: Routledge.

- Prentki, T., and Abraham, N. 2021. The Applied Theatre Reader. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pruitt, L., and E. R. Jeffrey. 2020. Dancing through the Dissonance: Creative Movement and Peacebuilding. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Republic of Rwanda. 2015. National Youth Policy. Kigali: Rwanda. https://nyc.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/template_new/documents/National_Youth_Policy.pdf.

- Shaughnessy, N. 2015. Applying Performance: Live Art, Socially Engaged Theatre and Affective Practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shier, H., M. H. Méndez, M. Centeno, I. Arróliga, and M. González. 2014. “How Children and Young People Influence Policy-Makers: Lessons from Nicaragua.” Children and Society 28: 1–14.

- Thompson, J. 2009. Performance Affects: Applied Theatre and the End of Effect. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tisdall, K. 2015. “Children and Young People’s Participation: A Critical Consideration of Article 12.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Children’s Rights Studies, edited by Wouter Vanenhole, 185–220. London: Routledge.

- USAID. 2019. USAID/Rwanda Youth Assessment. (Online) Accessed 15 April 2021. https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/USAID%20Rwanda%20Youth%20Assessment_Public_10-15-19.pdf.

- Wigle, J., P. Stewart, A. E. Birn, B. Gladstone, and P. Braitstein. 2020. “Youth Participation in Sexual and Reproductive Health: Policy, Practice, and Progress in Malawi.” International Journal of Public Health 65: 379–389.

- Youth Connekt. 2021. About. (Online) Accessed 14 May 2021. https://youthconnekt.rw/site/home.