ABSTRACT

This article explores how sharing and listening to stories linked children and young people, educators, artists, civil society workers, and policymakers as part of a continuum of transitional justice processes in the aftermath of conflict Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) initiative. We argue that sharing stories within a peace education context can potentially help to address everyday conflicts and personal and social wounds, often due to the residue of past conflicts. MAP facilitates a community of listening and/or a community of listeners through arts-based approaches that engages the individual to listen to oneself, the community to listen to the other, and the society to listen to inform everyday peacebuilding.

This article explores how sharing and listening to stories linked children and young people, educators, artists, civil society workers, and policymakers as part of a continuum of transitional justice processes in the aftermath of conflict in Rwanda through our Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) initiative. In Rwanda, an Indigenous form of mediation called gacaca (meaning justice in the grass in Kinyarwanda) was used for both justice and reconciliation to adjudicate crimes connected to the 1994 Rwandan Genocide against the Tutsi. Testimonies were collected in every village or cell between the opening of the local level courts from 2004 to the closing of the courts in 2012. During that time, the whole of the population was mandated by law to attend the local level courts weekly to share what they witnessed and to testify to crimes committed during the time of the genocide. Persons of integrity or inyangamugayo were elected by the local community to serve as judges. Although most attendees were adults, many children attended the local level courts with their family members and heard testimonies first-hand. This essay provides an example of how arts-based methods and performance were used for sharing stories a decade following the closing of gacaca within a peace education context. We argue that sharing stories within a peace education context can potentially help to address everyday conflicts and personal and social wounds, often due to the residue of past conflicts ().

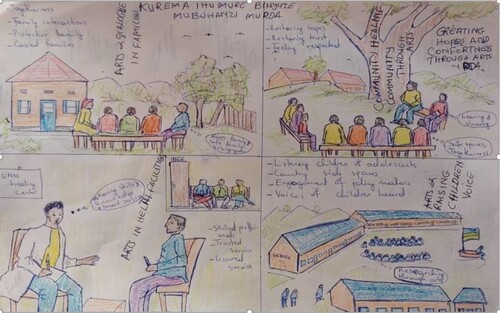

Figure 1. ‘Kurema ihumure mu muryango binyuze mu bugeni’ meaning Creating Hope and Comfort in Rwanda through Arts: A drawing made by Chaste Uwihoreye and Uyisenga Ni Imanzi (UNM) team. It represents examples of people from communities listening to people from the same communities in different settings such as schools, families, communities and health facilities.

Concerning listening to young voices, Virginie Ladisch (Citation2018, iii–iv) states:

As adults in positions of power, we need to open our ears to hear the reality of how young people are impacted by human rights violations, how they see their society, where it is going, what role they see for themselves, and their vision for the present and future … Opening spaces for children and youth to speak also lays the groundwork for their ongoing civic engagement.

Transitional justice and peace education

The interrelation between transitional justice and peace education has increasingly become an area of praxis involving state-sanctioned education reform policies and curriculum in post-conflict contexts alongside peacebuilding campaigns in formal and informal sectors of society. In an article included in a special 2017 issue of Comparative Education, M.J. Bellino, J. Paulson, and E. Worden highlight three primary foci within this area of scholarship: (1) transitional justice, education and the lens of the past; (2) transitional justice inside the classroom; and (3) transitional justice as education writ large. They provide an overview of the interplay between transitional justice and peace education that is useful for the framework of this paper:

We conceive of education as underpinning all transitional justice activities in formal, informal, and non-formal ways. Non-formal ‘outreach’ activities, such as government publications or radio broadcasts, aim to inform the public about transitional justice processes and outcomes … Schools, as formal education institutions, have been sites of substantial investment as well as national and transnational collaboration geared towards curricular reform. The nature of these collaborations and engagements, however, has been widely variable across contexts, and in many cases, the educational sector remains an afterthought (Ramirez-Barat and Duthi Citation2017). From the perspective of transitional justice poised to contribute to thick democracy and sustainable peace, education emerges as a vital mechanism and not merely an institutional context for transmitting messages that unfold outside educational spaces in the political sphere (Bellino Citation2016, Citation2017; Murphy Citation2017) (Bellino, Paulsen, and Worden Citation2017, 317).

Although there are theoretical models that explore the role of peacebuilding in education (Novelli, Lopes Cardozo, and Smith Citation2017), there is a lack of empirical studies related to how peacebuilding initiatives engage with children and young people in the design and delivery of education with a focus on both ‘peacebuilding’ and addressing factors related to social, cultural and political hindrances to peace (Taka Citation2020). While working towards the understanding of positive peace (Galtung Citation1976, Citation1990) it is important to consider how young people in a post-conflict context might position themselves regarding some of the competing agendas that impact their daily lives, for example, between not having enough food to eat, serving as the primary carer when parents migrate for work, earning money for the family, and resolving inner and outer instances of conflict and mental health issues. Johan Galtung expanded on the concept of structural positive peace:

Structural positive peace would substitute freedom for repression and equity for exploitation, and then reinforce this with dialogue instead of penetration, integration instead of segmentation, solidarity instead of fragmentation, and participation instead of marginalization. Some large, vertical (alpha) structures may be necessary, but small, horizontal (beta) structures are more beautiful (avoiding too much structuration). This also holds for inner peace: the task is to bring about the harmony of body, mind, and spirit. Key: outer and inner dialogue with oneself (Galtung Citation1996, 32).

How might young people communicate their individual and communal needs and issues to best position themselves as a subject in their own lives and schooling processes? How can teachers and decision-makers respond to the needs and issues of young people to create a ‘peace culture’?

MAP used arts-based approaches drawing on the richness of Rwandan cultural forms, such as proverbs and storytelling practices, to explore knowledge and processes of meaning-making about trauma, memory, and everyday forms of conflict from the perspectives of children and young people (Pells et al. Citation2021). Peace culture in schools, as described by MAP research participants, was largely considered a mechanism for enhancing social relations between students, teachers, and the larger community. The use of arts-based approaches helped to situate the knowledge with the young people and provided confidence to share skills in conflict management both at school and at home. Several participants noted the importance of training and skill development in arts-based methods as a vehicle for communication and social cohesion by enabling young people to express their needs and issues and to engage parents, community members, and decision-makers to resolve the issues and respond to the problems that could inform local everyday peace (Mac Ginty Citation2014).

Listening

Listening involves being fully present and open to both verbal and non-verbal communication cues. Listening in the context of MAP is to listen to oneself, to listen to the other or the group, and to listen to the community, for change. A Rwandan proverb states ubwira uwumva ntavunika, meaning that when an individual or teller shares a story with someone who gives attention, the teller becomes open and expresses his or her feelings because there is the belief that the listener will help him or her to heal wounds. The noted proverbs were used to inform a local and contextualised approach to mental health and well-being through the co-production of a psychosocial module that was used to link mental health service users to mental health service providers during the pandemic (Breed et al. Citation2022). The objective to ‘listen for change’ creates concrete reasoning for how and why an individual would share or gift their story, and relates to how one receives the story towards a desired purpose to create change or solve a problem. This involves not only the individual or teller, but also the listener and listeners and may extend from sharing stories in pairs, to small groups, or a community context. In this way, there is a cycle for listening through which the connection and embodiment of stories creates a community of listening and/or a community of listeners.

In the MAP project, sharing and listening to stories entailed several steps and ongoing interaction between a community of participants. In Kinyarwanda, there is a saying, ugira imana abona umugira inama, which means that a teller is very lucky when she or he finds a listener with integrity with whom to share a story, and the listener responds with advice. For this article, activities will be described from week-long residential training camps that were delivered to prepare youth facilitators to create MAP clubs in their schools. Often, there was a series of exercises that moved towards the culminating moment of sharing personal stories or the ‘story circle’. The games or activities were designed to make one feel relaxed, to enable freedom of expression, to allow a space to explore and experience emotions and to practice listening and embodiment through a range of art forms. Games allowed the individuals to mix as a group and to establish trust. It enabled young people and adults to mix in a way that helped to alleviate hierarchies based on age or profession and to create an equilibrium of balance and equality. Eye to eye and shoulder to shoulder, participants began by sharing small day-to-day stories that led into larger life stories that could be equated as life histories. Another Rwandan proverb states habwirwa benshi hakumva beneyo, meaning that sharing different life stories with different kinds of people allows an individual to listen intentionally for change and choose what is most important and useful.

Listening with the intention for change entailed an extended listening or third ear; an ear that was outside of the dialogue and situated within the community to consider how one story might connect to the stories of others. The sharing of stories did not end with the testimony but extended into finding solutions together. Thus, listening involved action. In Kinyarwanda the saying ujya gutera uburezi arabwibanza highlights that you can’t give what you don’t have, which implies the importance of listening carefully and attentively to avoid mistrust. There was a responsibility for the listener to hold the story and for the community of listeners to consider solutions alongside the teller.

Sharing stories

In Kinyarwanda, the proverb ababiri bashyize hamwe baruta umunani barasana means ‘two friends working together are greater than eight people that are in a fight’. We use this proverb to show how working together collectively can contribute towards making positive social change and support community aspirations. Collective and social support fosters space to express emotions and establish trust between young people and their community. The sharing of stories focuses on understanding self and others, expressing oneself through visual and performance-based methods.

Research has proven that as a result of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, elements of trust and hope were adversely affected. In Rwanda, it has been found that psychosocial interventions are an important contribution to building individual and community resilience, social cohesion and trust (NURC Citation2019). Another Rwanda proverb umwana uzi ubwenge bamusiga yinogereza explains that once you get an opportunity to share your story with someone who gives you time and helps you to cope with wounds and emotional problems it is up to you to build your resilience. The lack or absence of trust has been shown to not only affect victims of the genocide but also to impact later generations, including young people as they encounter issues with developing meaningful relationships. Arts-based approaches and their core conventions of trust-building and team-building can support psychosocial well-being. MAP exercises aim to combine arts-based approaches with psychosocial interventions for young people to explore emotions and develop trust. The Rwandan proverb ahari abagabo ntihapfa abandi means ‘where there are men, others could never die’. The proverb emphasises collective working to support the resolution of internal psychological conflicts whilst developing positive social outcomes.

In Kinyarwanda, the proverb igihishe kirabora na nyiracyo akabora can be translated to ‘not being able to externalize one’s painful story undermines psychological and mental health wellness’. Other proverbs that can be translated as ‘it’s God’s blessing to have an advisor’ and ‘it is really good to talk to someone who understands you’ illustrate the cultural importance to hear and to listen deeply to the stories of others, for stories to have a healing affect/effect. Another proverb, ukize inkuba arayiganira, ‘it is noble and supportive to talk about hard conquered battles’, supports the encouragement of participants to share deeply their personal stories – the stories that have impacted their psychological life – as well as to develop advanced listening skills that can be further engaged through arts-based methods.

Negotiating pain by listening to your own internal story and the stories of others

Active listening entails being fully present and open to communication by listening for both verbal and non-verbal information as communicated through gestures, tones, pauses, and emotions. According to Nancy Kline (Citation1999), the quality of a person's attention while listening also determines the quality of other people's thinking; active listening ignites the brain to enable the teller to think better. This, in turn, can enable participants to listen to themselves and others while aiming to identify and solve problems. Within MAP, listening created a kind of space for tellers to use symbolic and metaphoric means to both communicate verbally and nonverbally through the use of symbols (drawings), gestures (images and physical movements), and narratives (stories). It also created social belonging through week-long residential training and ongoing connection through MAP clubs and both online and face-to-face workshops (workshop sizes varied from 30 to over 100 with smaller break-out sessions). John Dewey describes what is ‘the process of creating participation, of making common what had been isolated and singular;’ and adds that ‘part of the miracle it achieves is that, in being communicated, the conveyance of meaning gives body and definiteness to the experience of the one who utters as well as to that of those who listen’ (Dewey Citation2005, 253). Listening gives body and definiteness to experience and changes a singular experience into a shared one. In MAP, active listening can be illustrated through the positioning of an open versus closed body, eye contact (as culturally appropriate and with sensitivity for working with individuals with autism), and the response to the teller by playing back the essence of a story through a still image, for instance. In this way, dialogue is created through images as well as words, using metaphor and symbols for meaning-making. Here is an example of how performance was used to enable active listening and deep connection through a description of the ‘musical dialogue’ exercise.

Participants are guided to move around the room to music while noticing how their body is moving, what they are feeling and to become aware of the visual elements of the space (light and dark spaces, objects in the room, etc.). Then, to begin making eye contact with one another; to greet one another with the eyes. After participants have connected to one another through eye contact, then the music stops and individuals are directed to form pairs. In pairs, participants sit across from one another with an open stance and are instructed to take turns sharing and listening to stories. The listener receives the story and pays attention to verbal and non-verbal cues to hone-in on the essence of the story. After the teller has shared their story, the listener or receiver stands up in front of the teller and makes eye contact to thank them for their story, then creates a frozen image to communicate the essence of the story. Then, the listener or receiver becomes the teller and the former teller becomes the listener and shares an image that communicates the essence of the story. Following the sharing of a happy story, the exercise continues. Participants stand up and move through the space again until the music stops. Participants are directed to form new pairs to share a sad story. The exercise continues as described previously until the final prompt to share a story relating to a hope for the future. ‘Musical Dialogue’ ends with a reflection circle to explore what participants observed and felt during the exercise and to share any general findings or possible applications for the exercise based on the knowledge gained. In this way, participants move from personal experiences to group reflections to potential engagement with the wider community and/or society. Stories often involve key life events that enable participants to see and to understand one another at a deeper level that establishes trust and narrates a personal account of oneself.

Social belonging involves deep connectedness (Allen et al. Citation2021) and ‘remains one of the most important psychosocial strategies for promoting resilience and fostering recovery, adjustment, and growth’ (Slavich, Roos, and Zaki Citation2022, 2). Deep connectedness was forged in MAP through active listening during the sharing of personal stories from day-to-day to more significant events. However, this also incorporated compassion concerning understanding stories and events as part of a larger human experience using exercises such as one we call ‘obstacle tree’ to explore root causes of problems and kindness as prosocial acts to support others through the engagement with potential solutions. During the exercise, participants discuss a problem that they face and identify the root causes and possible consequences of the problem. This exercise generated information concerning the issues that young people face and the challenges to peacebuilding (core to the project aims and research questions). Here, listening is a group activity in a learning environment. In addition, it is facilitated by someone equipped with psychosocial skills to mitigate the risks concerning the act of listening to personal stories that may relate to traumatic experiences and/or memories.

To provide an example of how the MAP project navigated painful histories and emotions, we will share participant observation notes that Ananda Breed took from a training-the-trainer (TOT) session with MAP youth and adult master trainers led by our resident psychosocial expert, Chaste Uwihoreye, from Uyisenga Ni Imanzi, in July 2020.

Chaste led the session with a song in Kinyarwanda that can be translated as: ‘We need to restore the heart and nurse the wound. The wounds in this life come from what we have heard and seen. Opening hearts. This world is difficult. Others pass through well. Others go through difficulty. When I follow them, I don't know where to go. I want to wipe my tears and then you give me blessings. I try my best. I touch the grass. The grass goes with me. I am taken by the grass.’

Chaste asked the workshop participants what they heard. A female MAP master trainer responded: ‘The problems and anguish. Being confused. You fail. I have heard that there are things you can do to change the situation. I have heard that some people are examples. You want to live like him or her, but you fail.’ Chaste responded: ‘All those things are life. Everyone comes here. No one had an application to come here. I didn't know I would be born in Kibuye. Wherever you are from, you struggle.’ He then led the group through a meditation to go through the different phases of their life. Individuals stated that they passed through difficult periods and reflected that the dark periods seemed to override any joy or good times in their memory. After the meditation, one male MAP master trainer stated: ‘We think about the bad events that we experience. We see the community and what we experienced.’ Another male MAP master trainer stated: ‘I don't have answers. When watching the internal film [story] of my memories, I see stress and horrible things. Then, in the end, I thought about why people write or compose music and songs … why the ones who write or sing often give no solutions. They often sing about the situation.’ Chaste then led the group to consider their role as MAP master trainers and as individuals who experienced painful pasts; that the participants may have the same kinds of memories and painful stories that the MAP master trainers have experienced in their own lives. One male master trainer stated: ‘Now, I have seen that we always have the same problems. We struggle the same. I understand that those we are going to train are individuals who have the same problems. Let us listen to their internal films [stories] and help to build their future and to have hope in the future. The lesson I have gotten from this exercise, I can express in two parts. One part is reminding myself about what happened. I was sharing my story with myself, as a Master Trainer, I tried to remember but also I think that I have the responsibility to keep others safe. As a Master Trainer, I need to connect my memories to theirs because it is the same. I can't be too emotional because I need to help others. I think about myself, but have the responsibility to help others.’

This exercise focused on the importance of shared life experiences to create deep connection between individuals who experienced the events of genocide and/or the aftermath of genocide through the intergenerational transmission of trauma. Through one's pain, to connect to the pain of others. Uwihoreye referred to this as an ‘opening of the heart’. He emphasised the point that ‘life is suffering’ is a basic fact. This relates to the Rwandan concept of kubabarira or shared suffering, often described to Breed as the uniting factor between survivors and perpetrators when establishing grassroots arts associations (Breed Citation2014). The meditation connected trainees with their life stories: The awareness of their life stories and building trust by sharing personal stories within previous training-of-trainer sessions is an important step for them to prepare to listen to stories from other people from their community. A MAP female youth master trainer stated:

We live with ups and downs and good things and bad things. Some of us lost our relatives, others lost friends. Of course, there is another positive side. That is why we are patient. In terms of how problematic is life today? I see there is a change and an improvement. There is education and understanding. There are fewer problems. Now, we have a future and see where we are heading. Even though life is difficult, we see a future.

According to the research participants, the arts allow people to momentarily free themselves from their bad histories. They allow them to address their problems. Arts and drama are described by participants as a source of joy in society. Through the arts and drama, people can gain knowledge about issues surrounding well-being and prepare better for their future as is exemplified in the quote from a teacher below:

Artists perform about daily life in society and engage with issues in our lives, our aspirations and our needs. Art is a good medium to convey messages about the rebuilding of our country, respect, [and] happiness. The message reaches a broad and diverse audience, and people are happy and entertained. Because we can teach unity, love, and teamwork using theatre, drama and arts. Through [the arts], peace messages are delivered to people who, [in turn], can become peacemakers. Arts and drama are pathways for peace education. Arts and drama are tools for communication (feelings and ideas). The communication of feelings and ideas is the first step towards peace education. By observing or using the arts and drama, people are excited, [and] happy. It is a source of joy. Arts and drama bring people together. By sharing their creative [pieces] and drama, communities are coming together.

Although we have provided a general example of how sharing and listening to stories through arts-based approaches can address issues and enable spaces for personal and collective healing, there are possible risks to the sharing of personal stories in a post-conflict context. According to Karen Brounéus (Citation2010) longer exposure to truth-telling has not lowered the levels of psychological ill health, nor the prevalence of PTSD over time. Concerning her randomized study that was conducted with over 1200 Rwandans, the effects of truth-telling through the gacaca courts did not evidence a positive association with sharing stories. We would argue that the context of truth-telling or the sharing of stories during gacaca was directly associated with a judicial system and that any act of telling could be linked to incrimination. Additionally, participation was mandated by law versus given voluntarily and the tellers and listeners did not have options about what kinds of stories were told and heard and how the stories would be shared. In this way, there are extreme differences between sharing stories during a transitional justice process like gacaca and potentially in the aftermath of gacaca as part of peace education, as is suggested through the MAP project.

In short, what are the risks? There is a risk that individuals can share stories without the building up of a container or safe space that has been established through expectations/agreements and trust-building exercises. Without this foundation, individuals can be at risk to share information that might not be supported or held appropriately. While building up to the sharing of stories, participants need to become skilled in active listening and to practice telling and listening with a series of exercises that focus on low-risk stories. After the trust is established and the knowledge and understanding of how to hold the stories of others are established (with supervision and training from psychosocial workers), then individuals are invited to share stories that might be considered as having more substance with wider social/cultural/political issues. Facilitators learn how to use varied arts-based approaches to engage each individual, monitor group dynamics to ensure equity across genders and socio-economic and political backgrounds and build a safe and inclusive space. Artists, educators, and MAP youth and adult trainers work in tandem with psychosocial workers to create safe spaces in such contexts. MAP provides a method to not only establish a space for telling and listening to personal stories but also to incorporate the engagement of a wider network to support youth-led initiatives for change.

In terms of accountability, the MAP approach required the knowledge and understanding of research participants alongside the wider community for the issues and concerns of young people to be listened to. This required information meetings conducted with parents and community members, approval from regional government institutions and local government bodies, and the engagement of relevant stakeholders (in response to issues raised by the young people). Additionally, the methodology incorporated exercises developed by young people, educators and artists, and the adaptation of artistic forms. A week-long training of trainers further co-produced the curriculum and engaged the adult and youth master trainers to make any necessary adaptations. Participant information forms and consent forms were shared with care-givers, research participants, and schools. The project incorporated ongoing consent to ensure that individuals were aware that they could opt out of exercises or refrain from sharing when needed. The role of the psychosocial workers was crucial throughout the process to monitor group dynamics, provide personal one-to-one support when needed, and coach groups through difficult stories. MAP included a safeguarding lead and incorporated a safeguarding policy alongside training workshops for MAP researchers and trainers.

Conclusion

MAP used arts-based methods as a vehicle for expression in consultation with young people, artists and educators. The week-long residentials enabled a space for dialogue through a series of exercises focused on trust-building, teambuilding, sharing stories, and deep listening. Young people identified the root causes of conflict and analysed solutions. Performance was used to identify themes through ‘story circle’ followed by the analysis of issues through a ‘conflict tree’ and by devising a theatrical production through storyboarding and disseminating findings to voice the varied issues that were identified by the young people. In the MAP project that has extended to Kyrgyzstan, Indonesia, and Nepal, there are additional examples of how young people created youth-led arts-based research projects to illustrate issues.Footnote1 In Kyrgyzstan, youth researchers focused on migrant children and girls’ lack of access to education through film. In Nepal, youth researchers focused on gender-based violence through dance and music. In Indonesia, youth researchers focused on youth-to-youth brawls through comics. In Rwanda, youth researchers focused on mental health and wellbeing through visual arts, theatre, dance, music, and creative writing. Once the issues were identified, relevant stakeholders such as local-level district and sector decision-makers were consulted to serve as a responsive audience to stand as witnesses and to be held accountable for their own proposed solutions to the problem(s). Finally, local decision-makers and policy-makers were engaged as key partners for young people to serve as ‘agents of change’, to influence the issues and problems of concern to them.Footnote2 Here, we rethink politics and institutional changes as requiring a kind of listening and talking or a politics of dialogue (Farinati and Firth Citation2017). In this essay, we’ve highlighted the importance of sharing stories and listening to hold memories, emotions, and multiple narratives that can cross-over between personal and collective experiences and stories.

When asked about the role of MAP in post-conflict Rwanda, a current MAP master trainer who was previously a youth grassroots arts association member during the time of gacaca stated:

MAP activities bring out different ideas of how people can behave through arts. It can help communities to see how they can be involved to build their country together. MAP activities create a psychological way of bringing people together. When we start to mingle, we come together and it is easy to communicate. Art can raise the emotions of people. When people are emotionally ok, then they can make the right decisions. This can help with creating tolerance and humour among people. Where there is art, justice can be done well.

This last statement emphasises the mechanisms for ‘justice done well’ as bringing people together, facilitating and easing communication, and supporting emotional wellbeing. MAP and other arts-based approaches can enable individuals and communities to redefine spaces (physical, relational, and emotional) for transitional justice and peace education as an ongoing component of peacebuilding.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of University of Leeds for Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) project Changing the Story (PVAR 17-016) and the University of Lincoln for AHRC Follow On Funding (2020-0587) and UKRI/GCRF Newton Fund (2020-3851).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and from guardians for all children and young people. Consent was given for both participation in the studies involved and for the publication of data.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to acknowledge and thank MAP team researchers, staff members, and research participants who contributed to the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For more information about Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) and to see in-country artistic outputs and policy briefs from Kyrgyzstan, Rwanda, Indonesia and Nepal, please go to: https://map.lincoln.ac.uk.

2 For further information about the role of young people as ‘agents of change’ please see the following article that provides an example of how young people used performance and a policy brief to address issues related to disability rights: Breed et al. (Citation2022).

References

- Allen, Kelly-Ann, Margaret L. Kern, Christopher S. Rozek, Dennis M. McInerney, and George M. Slavich. 2021. “Belonging: A Review of Conceptual Issues, an Integrative Framework, and Directions for Future Research.” Australian Journal of Psychology 73 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409.

- Bellino, Michelle J. 2016. “So That We Do Not Fall Again: History Education and Citizenship in ‘Postwar’ Guatemala.” Comparative Education Review 60 (1): 58–79. doi:10.1086/684361

- Bellino, Michelle J. 2017. Youth in Postwar Guatemala: Education and Civic Identity in Transition. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Bellino, Michelle J., Julia Paulson, and Elizabeth Anderson Worden. 2017. “Working Through Difficult Pasts: Toward Thick Democracy and Transitional Justice in Education.” Comparative Education 53 (3): 313–332. doi:10.1080/03050068.2017.1337956

- Breed, Ananda. 2014. Performing the Nation: Genocide, Justice, Reconciliation. Chicago: Seagull Books.

- Breed, Ananda, Chaste Uwihoreye, Eric Ndushabandi, Matthew Elliott, and Kirrilly Pells. 2022. "Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) at Home: Digital Art-Based Mental Health Provision in Response to COVID-19." Journal of Applied Arts & Health 13 (1): 77–95. doi:10.1386/jaah_00094_1.

- Breed, Ananda, Kirrily Pells, Matthew Elliott, and Tim Prentki. 2022. “Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP): Creating Arts-Based Communication Structures Between Young People and Policymakers from Local to National Levels.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 27 (3): 304–321. doi:10.1080/13569783.2022.2088274.

- Brounéus, Karen. 2010. “The Trauma of Truth Telling: Effects of Witnessing in the Rwandan Gacaca Courts on Psychological Health.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 54 (3): 408–437. doi:10.1177/0022002709360322

- Dewey, John. 2005. Art as Experience. New York: The Berkely Publishing Group.

- Farinati, Lucia, and Claudia Firth. 2017. The Force of Listening. Berlin: Errant Bodies Press.

- Galtung, Johan. 1976. “Three Realistic Approaches to Peace: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking and Peacebuilding.” Impact of Science on Society 26 (1-2): 103–115.

- Galtung, Johan. 1990. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 27 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1177/0022343390027003005

- Galtung, Johan. 1996. Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. London: Sage.

- Kline, Nancy. 1999. Time to Think: Listening to Ignite the Human Mind. London: Cassell Illustrated.

- Ladisch, Virginie. 2018. Foreward to Listening to Young Voices: A Guide to Interviewing Children and Young People in Truth Seeking and Documentation Efforts, edited by Valerie Waters. International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ).

- Lloyd, Karina J., Diana Boer, Avraham N. Kluger, and Sven C. Voelpel. 2015. “Building Trust and Feeling Well: Examining Intraindividual and Interpersonal Outcomes and Underlying Mechanisms of Listening.” The International Journal of Listening 29: 12–29. doi:10.1080/10904018.2014.928211.

- Mac Ginty, Roger. 2014. “Bottom-up and Local Agency in Conflict-Affected Societies.” Security Dialogue 45 (6): 548–564. doi:10.1177/0967010614550899

- Murphy, Karen. 2017. “Education Reform Through a Transnational Justice Lens: The Ambivalent Transitions of Bosnia and Northern Ireland.” In Transitional Justice and Education: Learning Peace, edited by C. Ramirez-Barat, and R. Duthie, 65–98. New York: Social Science Research Council.

- National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC). 2019. Assessment of the Healing Approaches in use in Rwanda. Kigali: Republic of Rwanda.

- Novelli, Mario, Mieke T. A. Lopes Cardozo, and Alan Smith. 2017. “The 4Rs Framework: Analyzing Education’s Contribution to Sustainable Peacebuilding with Social Justice in Conflict-Affected Contexts.” Journal on Education in Emergencies 3 (1): 14–43. doi:10.17609/N8S94K

- Pells, Kirrily, Ananda Breed, Chaste Uwihoreye, Eric Ndushabandi, Matthew Elliott, and Sylvestre Nzahabwanayo. 2021. “‘No-One Can Tell a Story Better Than the One Who Lived It’: Reworking Constructions of Childhood and Trauma Through the Art in Rwanda.” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry: An International Journal of Cross Cultural Health Research 46 (3): 1–22. doi:10.1007/s11013-021-09760-3.

- Ramírez-Barat, Clara, and Roger Duthie. 2017. Transitional Justice and Education: Learning Peace. New York: Social Science Research Council.

- Slavich, George M., Lydia G. Roos, and Jamil Zaki. 2022. “Social Belonging, Compassion, and Kindness: Key Ingredients for Fostering Resilience, Recovery, and Growth from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 35 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/10615806.2021.1950695.

- Taka, Miho. 2020. “The Role of Education in Peacebuilding: Learner Narratives from Rwanda.” Journal of Peace Education 17 (1): 107–122. doi:10.1080/17400201.2019.1669146.