?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examines whether the possession of a credit rating has an impact on firms leverage ratio. The issue of access to alternative sources of debt finance has received special attention in the wake of 2007–2009 financial crisis when banks significantly cut back on loans and firms became credit-constrained. Consequently, policy makers have been examining ways of facilitating access to non-bank finance. An overreliance on bank sourced debt finance when credit markets tighten has the potential to slow down the speed of economic recovery. This paper provides empirical evidence in support of the hypothesis that the possession of a credit rating is associated with higher leverage ratios. The effect for UK firms seems higher than that observed for similar US firms. This might be because there is greater financial transparency in the US implying lower levels of information asymmetry and so negating somewhat the effects of possessing a rating.

1. Introduction

Access to debt finance has become one of the major issues of concern for finance directors, trade bodies such as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) and public policy makers, such as the Bank of England since the 2007–2009 financial crisis. In March 2009, the Confederation of Business Industry’s Access to Finance survey reported that a net balance of 30% of companies indicated that financing conditions had adversely affected their output over the past three months. Concerns about the wider implications for the economy of the tightening credit conditions were also raised by public policy makers. For example, researchers at the Bank of England, Barnett and Thomas (Citation2013), suggest that tighter credit conditions played a significant role in explaining the weakness in output seen during the crisis. They find that between 2007 and the third quarter of 2012 tightening credit supply could have accounted for between a third and a half of the overall fall in GDP compared to its historic trend. This evidence suggests that the ease with which credit flows to the corporate sector is an important driver of economic activity and that tighter credit conditions during and after the financial crisis slowed the recovery in the UK economy by constraining consumption and investment.

The corporate finance literature is replete with studies that investigate the determinants of capital structure. Since the seminal work of Modigliani and Miller (Citation1958) most of the empirical research in this area has concentrated on the demand-side determinants of capital structure, while very little emphasis has been placed on the role played by the availability or supply of debt capital. The implicit assumption of the prior empirical literature is that the supply of capital is infinitely elastic and firms’ borrowing decision depends solely on the demand for debt with no role for the supply side (Rajan and Zingales Citation1995; Frank and Goyal Citation2007). In a real world context, information asymmetry and other market imperfections imply that the supply of capital is not perfectly elastic and some firms might find themselves credit-constrained and unable to raise the desired level of debt (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006). It follows that these firms could be significantly under-levered relative to those firms that are not faced with supply-side constraints.

Only in the last decade and a half have researches recognised the importance of the supply-side as a potential determinant of capital structure. Several recent studies have argued that possessing a credit rating provides a ‘key which opens the door’ for accessing the public debt markets and consequently facilitates the take-up of greater leverage. For example, Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006), Mittoo and Zhang (Citation2008), Kisgen (Citation2009) show that companies with a credit rating have access to greater sources of debt, and consequently are more highly levered. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) argue that in the presence of information asymmetry firms with a credit rating can access the arm’s length capital markets and are able to borrow more and so consequently face lower financial constraints. Leary (Citation2009) finds that following the 1966 Credit Crunch in the United States, larger firms with access to public debt market were less affected by contraction in loan supply due to their greater ability to substitute toward arm’s length debt financing.

It would seem then that a credit rating can potentially provide several benefits to a firm. It can widen the investor base and the greater transparency can improve the pricing of debt. A credit rating provides an opportunity to enter foreign bond markets and gain international visibility, thereby reducing the reliance on local banks. This is especially important for UK corporates given the relatively small size of the local capital market relative to that in the US, which is the largest source of debt capital in the world. Given these supply side benefits recent capital structure research suggests that firms that possess a credit rating are likely to have higher leverage ratios than those without one. We test this prediction using a sample of UK non-financial firms over the period 1989–2010.

This paper by providing an additional and highly pertinent case study on the role of credit ratings in determining firm financing decisions makes an important contribution to the empirical literature. Up till now the extant empirical literature on the role played by credit ratings in determining capital structure has employed in the main samples of US or Canadian firms (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006; Mittoo and Zhang Citation2008; Leary Citation2009), while paying little attention to the importance of having a credit rating outside a North American context. Farrant et al. (Citation2013) point out that corporate bond issuance in the United Kingdom has increased significantly since the early 1990s. They note that the stock of outstanding debt securities issued by UK companies rose from around 10% of nominal GDP in 1992 to around 25% in 2012. Furthermore, they find that bond issuance since 2009 was stronger than the average between 2003 and 2008. It would seem that the UK provides a very good setting to investigate the role of access to public debt markets in determining capital structure choice. Furthermore, this research is highly relevant in the context of the public policy debate on firms’ access to non-bank finance. During the financial crisis and for several years after the peak of the crisis, the UK economy was subjected to a period of severe tightening of credit market conditions resulting in a significant reduction in the availability of bank credit and deterioration in the non-price terms and conditions of bank loans offered to the corporate sector. Many firms, and in particular small and medium sized firms, were starved of credit as banks restricted the level of lending. Public policy makers, such as Adam Posen, former member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, has suggested that UK firms are over reliant on the banks for their debt funding (Posen Citation2009). Tight credit markets and the lack of debt funding diversification coupled with the limited availability of non-bank sources of debt finance was deemed to have held back the UK recovery. Butt and Pugh (Citation2014) suggest that the tightening in credit conditions have been one of the main headwinds stifling economic recovery in the UK since the financial crisis. Using a range of econometric techniques, as well as controlling for endogeneity, the empirical analysis in our paper provides strong evidence that rated firms are more highly levered than their unrated counterparts. These findings imply that public policy makers and perhaps the credit ratings agencies should be looking at ways of improving access to bond markets for UK firms.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the empirical literature with a particular focus on studies investigating the importance of supply-side determinants of leverage. Section 3 describes our sample and the data employed and presents empirical results obtained from pooled OLS and panel estimation methods. In Sec. 4 we use instrumental variable and treatment effect regression methods to control for a range of endogeneity related issues. Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature review

2.1. Supply-side determinants of capital structure and hypothesis development

The main assumption of the seminal work of Modigliani and Miller (Citation1958) is that in the world with no market imperfections the supply of capital is unrestricted and firms can raise the desired amount of capital at the same cost of capital. This implies that the amount of debt in the capital structure is determined by the demand-side factors only. This was the underlying assumption of the most of the previous literature, which concentrated largely on the demand-side characteristics, while paying little attention to the supply-side factors. For example, Rajan and Zingales (Citation1995) in their cross-sectional study of the determinants of capital structure choice across G-7 countries concentrate on the four factors of capital structure: size (measured by sales), profitability, asset tangibility, and market-to-book ratio. They justify their choice by stating that previous studies have shown consistent correlation of these four factors with leverage (for example, Harris and Raviv Citation1991). However, they also mention that limitations on data availability restricted their ability to develop proxies for other determinants, implying that there might be other factors that determine corporate capital structure. Frank and Goyal (Citation2007) suggest that Rajan and Zingales (Citation1995) omit two crucial variables in their model—the effect of expected inflation and median industry leverage. They add these two factors to those four used by Rajan and Zingales (Citation1995). Frank and Goyal (Citation2007) refer to these six factors as ‘core factors’ that explain variation in capital structure and describe the model including these factors as the ‘core model’.

The above arguments fail to recognise the possibility that the supply of debt capital can be restricted and firms might not always raise the desired amount of debt due to both cost of debt and its availability. Market frictions such as information asymmetry can impact a firm's ability to raise finance such that debt funds are rationed by lenders. Informationally opaque firms are likely to be credit constrained. As banks have structures in place to determine which of these firms are creditworthy, these types of firms are more likely to borrow from banks. Theory predicts that an opaque firm is very likely to be credit constrained (Stiglitz and Weiss Citation1981). Banks tend to have the expertise and therefore an advantage at collecting information to evaluate the credit risk of opaque firms. It follows then that opaque firms are more likely to borrow from banks. However, these funds are likely to be a more expensive source of debt capital than that available from the public debt markets. The higher cost of bank debt is likely due to the expenses incurred in the monitoring of opaque borrowers. Furthermore, if the monitoring and additional scrutiny performed by a bank cannot completely eliminate the information asymmetry, then bank credit still may be rationed. As it is not always the case that a firm can source debt funds from both bank and public debt markets we could have a situation where a firm is debt capital constrained. So it follows that if credit markets are tight such that firms cannot raise the amount of bank debt they desire (some loan applications are rejected), and these firms don’t have access to the public debt markets we should see this manifest itself by way of lower leverage ratios for these bank debt constrained firms. It follows then that a firm’s capital structure (leverage ratio) could be related to a firm’s ability to access public debt markets. In this paper, we investigate this potential link.

The importance of the supply of debt has been acknowledged in recent years with several researchers recognising that information asymmetry can impact the firms’ ability to raise finance. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) show that firms with access to capital markets are able to borrow more and at lower rates of interest, whereas, firms without access can be significantly under-levered. As a result, firms with access to public debt markets have higher leverage ratios relative to those that do not have such access. Leary (Citation2009) also argues that firms with limited access to non-bank capital can be financially constrained. He finds that larger firms with access to capital market have a greater ability to substitute towards arm’s length financing. As a result, these firms were less affected by a contraction in bank loan supply during the 1966 Credit Crunch in the United States than firms without access. Leary (Citation2009) shows that following the 1966 Credit Crunch the use of public debt by firms with access to public debt markets increased, relative to that of small, bank-dependent firms. As a consequence, the leverage of bank-dependent firms significantly declined compared to firms with access to public bond markets.

It follows that market inefficiencies can influence firms’ ability to borrow and their desired level of leverage can differ from what they can obtain. Thus firms with limited access to additional sources of debt capital that fail to obtain their desired level of leverage are likely to be under-levered (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006). A credit rating by providing firms with access to public debt market helps to reduce information asymmetry between issuers and outside investors thereby widening the potential investors’ base for rated firms. As a result firms with a rating face fewer financial constraints and are able to borrow more, which could be especially important during periods when credit conditions are tight. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006), Mittoo and Zhang (Citation2008), Kisgen (Citation2009) find that firms with a rating can access public debt market, and consequently have higher leverage ratios than those without a rating. It follows that since a credit rating facilitates access to additional sources of debt finance over and above those sources available to all firms such as bank and non-bank private debt, companies with a rating should be able to raise more debt capital than companies without one.

With access to public debt markets and consequently credit ratings being a potentially important driver for firms financing decisions it is surprising that only a relatively small but growing number of papers have examined the relationship between credit ratings and capital structure decisions. Given the widespread use of credit ratings in the US, largely due to the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC thereafter) regulatory requirements, the overwhelming majority of the studies that have investigated the effect of credit ratings on capital structure employ US data. In the UK credit ratings have gained significant importance in recent years and the need for having a credit rating in the UK has been recognized by many corporates during the 2007–2009 financial crisis as a means to access alternative sources of finance (Bacon, Grout, and O’Donovan Citation2009).

2.2. Overview of the empirical literature examining the link between capital structure and credit ratings

A credit rating represents an opinion made by one of the major credit rating agencies (Standard and Poor’s (S&P thereafter), Moody’s Investor Service or Fitch IBCA) of general creditworthiness of either an issuer (individual, corporation or country) or a particular issue (a loan) (Eades and Benedict Citation2006). It provides information about the credit quality of a firm and hence broadens the scope of potential investors for rated companies, such as pension funds, hedge funds and mutual funds thereby increasing the supply of debt capital (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006; Kisgen Citation2007; Leary Citation2009).

Unlike most of the prior literature which focus mainly on the demand-side determinants of debt, a few recent studies have demonstrated that access to public debt markets measured by the possession of a credit rating play an important role in determining corporate capital structure is an important determinant of capital structure (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006; Kisgen Citation2006; Mittoo and Zhang Citation2008; Leary (Citation2009). However, as Kisgen (Citation2007) indicates, neither the trade-off nor the pecking order theories explicitly take the possession of a credit rating into account. Boot, Milbourn, and Schmeits (Citation2004) argue that credit ratings ‘play an economically meaningful role’ (Boot, Milbourn, and Schmeits Citation2004, 1). They point out that according to Standard and Poor’s document (in Dallas, 1997) ‘ratings often provide the issuers with an “entry” ticket into public debt markets, broadening the issuers’ financing opportunities’ (Boot, Milbourn, and Schmeits Citation2004, 3). Thus they argue that ‘credit ratings could act as “information equalizer” thereby enlarging the investor base’ (Boot, Milbourn, and Schmeits Citation2004, 3).

Rating agencies assign ratings by evaluating company’s information that is not publicly available (Kisgen Citation2007). Eades and Benedict (Citation2006) indicate that such agencies operate without any government mandate, and their opinions are independent from the investment community. A credit rating therefore helps to reduce information asymmetry between issuers and outside investors through the disclosure of new information and thereby facilitate a firm’s credit market access (Tang Citation2009). Tang (Citation2009) mentions that without certification from Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs thereafter) firms may be unable to borrow from public debt markets. Furthermore, by reducing information asymmetry a credit rating can increase firm value. An and Chan (Citation2008) in their study of the relationship between credit rating and IPO pricing document that firms without a credit rating can still go public by obtaining a loan issue rating only. However, according to An and Chan (Citation2008) they will be underpriced more than firms with a credit rating.

The quality of the assigned rating may also be relevant. Kisgen (Citation2007) suggests that having a good credit rating is important because regulations for both pension and mutual funds require limiting their investments in low-rated bonds (which are defined as having a rating A or less) (Kisgen Citation2007, 67). He argues that maintaining a particular credit rating level provides benefits to a firm, such as ‘the ability to issue commercial paper, access to investors otherwise restricted from investing in the firm’s bonds, lower disclosure requirements, reduced investor capital reserve requirements, improved third-party relationships, and access to interest rate swap or Eurobond markets’ (Kisgen Citation2007, 65). As a result companies in order to obtain the required financing, ‘target’ a particular rating and try to maintain it over time (Kisgen Citation2007). Kisgen (Citation2007) suggests that during adverse economic conditions obtaining financing becomes especially difficult for firms without an investment grade rating and they may have to forgo positive-NPV projects.

Graham and Harvey (2001) survey 392 CFOs in the US about the cost of capital, capital budgeting, and capital structure. They find that CFOs consider credit rating to be the second important debt factor following financial flexibility (57% of CFOs ranked credit rating as important or very important with mean of 2.46). Credit rating is especially important for large firms (mean of 3.14). Thus, Graham and Harvey (Citation2001) find financial flexibility and credit ratings to be the most important debt policy factors.

Bancel and Mittoo (Citation2004) conducted a similar survey to that of Graham and Harvey (Citation2001) that spanned 16 European countries although their sample was smaller than that of Graham and Harvey (Citation2001) (only 87 respondents compared to 392 respondents in the US survey). They find that a credit rating and target debt ratios are important issues for managers in firms across 16 European countries. Consistent with Graham and Harvey (Citation2001) their research shows that credit rating is ranked as the second most important determinant of debt after financial flexibility (73% of managers consider credit rating important or very important). By comparing managers’ responses from the US with European ones, they find that a credit rating is considered to be more important by European rather than US managers (73% of the European managers consider credit rating to be important or very important versus to 57% of the US managers).

Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) argue that a credit rating provides access to the public debt market and thus reduces dependence on local banks. Using a large panel dataset they find that firms which have access to the public bond market as proxied by having a debt rating have 6 to 8 percent more leverage even after controlling for firm characteristics that determine observed capital structure.

Sufi (Citation2009) examines the effect of the introduction of syndicated bank loan ratings (a loan made to a firm jointly by more than one financial institution) on company’s financial and investment policy. A loan rating is given to a specific tranche of borrowing tied to a particular project rather than to the company as a whole. This study finds evidence that firms that obtain a loan rating experience an increase in the supply of available debt financing, an increase in their equilibrium use of debt, and a permanent increase in their leverage ratio. In particular, Sufi (Citation2009) shows evidence that loan ratings allow borrowers to expand the set of creditors beyond domestic commercial banks toward less informed investors such as foreign banks and non-bank institutional investors. The results are significantly stronger in magnitude among firms that are of lower credit quality and do not have an existing public bond rating before the introduction of loan ratings. For instance, unrated firms that obtain a loan rating experience an increase in their leverage ratio by 0.11 more than rated firms that obtain a loan rating, which is more than 40% at the mean. These results suggest that loan ratings increase the supply of available debt financing. Although it seems that loan ratings increase the supply of available debt financing the affect on information asymmetry may not be as great as that caused by having a credit rating. An and Chan (Citation2008) in their study of the relationship between credit rating and IPO pricing document that firms without a credit rating can still go public by obtaining a loan issue rating only. However, according to An and Chan (Citation2008) they will be underpriced more than firms with a credit rating. Thus by reducing information asymmetry by a greater amount a credit rating can increase firm value.

Kisgen (Citation2006) and Kisgen (Citation2007) consider the effect of credit rating changes on firms leverage levels before and after a credit rating up- or downgrade, respectively. Unlike Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006), both Kisgen’s (Citation2006) and (2007) samples only include firms with a credit rating. Kisgen (Citation2006) finds that firms near either a credit rating upgrade or downgrade issue less debt relative to equity than firms not near a change in rating. His results indicate that firms near a ratings change issue approximately 1.0% less net debt relative to net equity annually than firms not near a ratings change. Kisgen (Citation2007) finds that firms reduce leverage following credit rating downgrades, whereas, rating upgrades do not affect subsequent capital structure activity, suggesting that firms target minimum rating levels. Firms that have been downgraded issue over 2.0% less net debt as a percentage of assets relative to equity the subsequent year than firms that have not been downgraded. Kisgen (Citation2007) finds the results of both papers to be complementary, since both papers find that it is consistent for firms to try to avoid/reverse downgrades and achieve upgrades. Tang (2009) examines Moody’s credit rating format refinement in 1982 to study the effects of information asymmetry on firms’ credit market access, financing decisions, and investment policies. Tang (2009) finds that a refinement rating upgrade leads to a 20 basis points reduction in firms’ borrowing costs over a refinement downgrade. He also finds that a higher refined rating allows firms to issue significantly more long-term debt than a lower refined rating in the one-year period subsequent to the rating refinement: a rating refinement upgrade leads to a 2% increase in firms’ subsequent long-term debt issuance over its previous debt issuance, relative to a rating downgrade. More recently, Kemper and Rao (Citation2013a, Citation2013b) have also looked at the effect of credit rating changes and argue that Kisgen's (Citation2006) results don’t hold for all financial circumstances. They find that only firms with a very low rating, such as B or below, consider credit ratings when determining their capital structure. Their findings also suggest that credit ratings do not seem to influence leverage decisions in firms that issue short-term debt such as commercial paper, that have investment opportunities, or make use of the debt capital markets. Furthermore, Kemper and Rao (Citation2013a, Citation2013b) suggest that rating changes are less likely to impact capital structure when firms have other means to manage their ratings levels, such as restructuring assets or lowering operating costs.

Several studies examine the relation between the level of a credit rating and a firm’s capital structure. In this respect, Hovakimian, Kayhan, and Titman (Citation2009) examine how firms target their credit ratings. They find that below-target firms tend to make financing, payout, and acquisition choices that decrease their leverage whereas above-target firms tend to make choices that increase their leverage. They also find these reactions to be asymmetric with firms reacting stronger when their rating is below the target than when the rating is above the target. Furthermore Hovakimian, Kayhan, and Titman (Citation2009) show that since a high rating requires a firm to include a substantial amount of equity in its capital structure (which can be very costly), high credit ratings are observed only for firms that are likely to benefit the most from a higher credit rating, e.g. growth firms that expect to be raising substantial capital in the future. In contrast, smaller firms may require proportionally more equity in their capital structures to achieve the same rating, which may be costly; hence, small firms tend to have lower ratings. Mittoo and Zhang (Citation2010) find that speculative grade firms have leverage ratios around nine percent higher than their investment grade counterparts for a sample of Canadian and US firms. These findings are consistent with the idea that investment grade firms maintain lower leverage levels because they are concerned about downgrades, while speculative grade firms increase their leverage to improve their financial flexibility. In the latter case, speculative grade debt can be an important source of financing for high growth firms, which can help to prevent the impact of adverse economic conditions and credit rationing. Similarly, Wojewodzki, Winnie, and Shen (Citation2018) show that the credit rating level is negatively associated with leverage and that firms with a low rating adjust their capital structure faster than firms with a high credit rating. The role of financial flexibility also plays a role in Byoun’s (Citation2011) study. He finds an inverted-U relationship between leverage and having a credit rating. Small firms with no credit ratings have lower leverage ratios since they issue much more equity than debt to ease their lack of financial flexibility, medium growing firms with credit ratings have high leverage ratios by issuing debt against large future expected cash flows, while large mature firms with good credit ratings have moderate leverage ratios as they rely on internal funds and use only safe debt in order to preserve financial flexibility. He considers these findings to be important since previous studies overlooked the roles of these variables and their non-linear relationship with the leverage ratio.

Some recent studies have examined whether there is an asymmetric effect on capital structure resulting from a rating change. Maung and Chowdhury (Citation2014) investigate the time it takes firms to adjust their capital structure when either an upgrade or downgrade of a credit rating occurs. They find that a rating change induces an adjustment in the leverage ratio, however, in the case of a rating downgrade the change in leverage takes place over a longer time period and is persistently significant compared to a rating upgrade. Similarly, Huang and Shen (Citation2015) find that a sample of global firms adjust their capital structure when ratings are downgraded, but they do not significantly adjust the capital structure when ratings are upgraded. In related research, Samaniego‐Medina and di Pietro (Citation2019) examine the effect of the plus or minus signs of a credit rating on the speed of leverage adjustment within a European context and include the 2007–2009 financial crisis years in their sample period. Their results confirm that companies with signs in their ratings slow their speed of adjustment to the target leverage ratio. In particular, when a rating is accompanied by a minus sign, a firm adjusts more slowly than firms either with a plus sign or without a sign. When the rating has a plus sign, the firm’s leverage adjustment is slower than when the rating has no sign. If a firm is close to losing its investment grade status they find the speed of leverage adjustment is close to zero.

The majority of the extant research employs US data. However, the factors driving the capital structure decisions of European corporates might differ significantly compared to those of US firms and across countries in Europe, especially since the legal systems, bankruptcy codes, corporate governance rules and tax regimes vary considerably across Europe all of which may influence firm financing decisions (see, for example, Antoniou et al. Citation2008; Rajan and Zingales Citation1995).

3. Sample, data and empirical analysis

3.1. Sample and data description

Our sample utilises data for the top 500 of UK listed non-financial firms by market capitalization for the period 1989 through to 2010. All financial firms are excluded from the analysis, resulting in a panel of 7,828 firm-year observations. All firms with zero debt (785 firms) are also dropped from the sample, resulting in a panel of 7,043 firm-year observations. This is done in order to avoid a misclassification bias caused by the assumption that these firms do not have debt because they do not qualify to have a rating. These firms might qualify for a rating but choose equity as a preferred source of finance (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006; Chava and Purnanandam Citation2011).

We obtain credit rating data directly from Standard and Poor’s (S&P) and Fitch credit rating agencies. We use a company’s long-term credit rating to proxy for access to the public debt markets. We use a credit rating dummy variable set equal to one if a firm possesses a rating (S&P and/or Fitch) in a particular year and zero otherwise. Credit rating data from S&P covers the 22 years from 1989 to 2010 and Fitch credit rating data covers 20 years from 1989 to 2008. We merge the two sets of data and use a firm’s S&P rating in cases where it has two ratings. Overall, 1,373 (17.5%) of firms in our sample have a rating (S&P and/or Fitch).

Data on leverage and other the firm-level characteristics is sourced from DataStream. Leverage is measured as a ratio of total debt over either market or book value of assets. Total debt includes short-term and long-term debt. It reflects the proportion of debt in the firm’s total assets. A full list of variables, their definitions and predicted relationship with leverage are reported in Appendix 1. All variables that contain firm-level data are winzorised at the 1% level. This minimises the chance of outliers having an effect on the results.

We include two variables that measure macroeconomic conditions. These are annual GDP growth rate, which intends to control for the economic conditions in the country and stock market return, proxied by the FTSE All-Share Index.

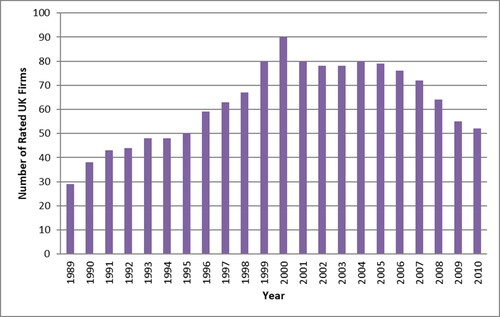

shows the frequency (left hand side) and the proportion (right hand side) of rated firms with S&P and/or Fitch ratings over the 22 year period from 1998 to 2010. The number of rated firms in our sample increases steadily from 1989 to 2000 and then starts to fall, due in part to mergers between rated firms, stock market de-listings and firms ceasing to possess a rating. This could also be due to the fact that Fitch ratings data is only available up to the year 2008.

3.2. Empirical analysis

In this study we utilise data for the period 1989 through to 2010. We employ both univariate and multivariate techniques in our empirical analysis. First of all, univariate independent sample t-test analysis compares leverage and other financial characteristics of firms with and without access proxied by having a credit rating. Multivariate regression analysis presents empirical results on whether the possession of a credit rating (i.e. access to public bond markets) can explain variation in leverage ratios, holding other things constant.

In our analysis we employ firm size as an alternative measure of access to debt capital markets. According to Leary (Citation2009) size is highly correlated with bond market access and therefore can help to verify the robustness of our results. Similar to Leary (Citation2009) we use book value of assets to generate proxies for bond market access based on firm size. We sort the firm-year observations by book value of assets and create three separate size dummies. In our first measure, firms in the top 30% of the distribution are classified as having access, whereas the remaining 70% of firms are considered as not having access. In our second measure, firms in the top 30% of the distribution are classified as having access, and firms in the bottom 30% are classified as not having access. In the last measure, firms with a rating are classified as having access, and firms in the bottom 30% are considered as not having access.

It is important to note that in the second and the third measures we have to drop a considerable number of observations. In our second measure we keep the top and bottom 30% for the firm size distribution and drop the middle 40% of firms. For the third measure we include all rated firms and those in the bottom 30% of the firm size distribution.

3.2.1. Differences in leverage ratios and other firm characteristics between rated and non-rated firms

In this section, we conduct univariate independent sample t-tests to verify whether leverage and other firm-level data differs between firms with and without public bond market access. Firm characteristics include size, age, profitability, asset tangibility, growth opportunities, business risk, tax shields—which are predicted to be related to firm’s indebtedness. Here we test whether these characteristics are also related to a firm’s ability to access capital markets. reports differences in mean and median values of firm leverage and other firm-level financial characteristics between firms with and without access.

Table 1. Differences in leverage and other firm characteristics between firms with access (A) and without access (NA).

Panel A of shows that firms with a rating have significantly more leverage in their capital structure than firms without a rating. The results are similar whether we measure leverage by market or book value of assets. The univariate t-test shows that companies with rating have on average 7% more market leverage and 9% more book leverage. When we measure access by size the percentage difference is even higher: almost 9% in Panel B1; 15% in Panel B2; and 14% in Panel B3.

Firms with a rating are also noticeably larger than firms without one, which is consistent with Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) who suggested that only large firms issue public debt due to higher fixed costs associated with issuing bonds. Firms with rating appear to be 33% older (both mean and median differences are statistically significant) and more profitable; possess on average 14% more tangible assets (the mean and median differences are statistically significant), but spend less on research and development and have lower growth opportunities as measured by the market-to-book ratio. Rated firms have lower risk, measured by asset volatility and have higher equity returns. Firms with a rating have 12% less short-term debt, which is consistent with the notion that public debt is likely to have longer maturity periods (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006). Average tax rates ratios, proxy for marginal tax rates, are expected to be higher for the rated firms because of the higher tax shields effect. We have some evidence in support of this. In Panel A the difference is positive but insignificant. However, in unreported analysis, when access is measured by firm size, the difference becomes statistically significant.Footnote1 In this section we have verified that firm-level factors are different for firms with and without access. It is thus essential to control for these factors in order to separate the effect of having a rating (access) on leverage in our multivariate regression.

Table B.1 reports a pairwise correlation matrix of the variables used in our analysis. It is apparent from this table that all the correlation values between variables are well below 0.7, in fact the highest correlation between the independent variables is 0.37 suggesting relatively weak levels of correlation. It follows that our multivariate estimations are not likely to have a multicollinearity problem.

3.2.2. Multivariate analysis

In the second stage of our empirical analysis we test whether the possession of a credit rating (access to public bond market) has an impact on firm’s leverage in a multivariate setting by estimating EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) :

(1)

(1)

Leverage is measured by the debt-to-asset ratio;

CreditRating measures a firm’s access to public debt markets;

Xit is a vector of firm-specific control variables that measure firm’s demand for debt (firm size, age of firm, profitability, asset tangibility, debt maturity, market-to-book ratio, R&D spending, asset volatility, equity return, debt tax shield). This allows us to measure the effect of having a rating on leverage ratios while holding other factors constant.

IDi—is a vector of industry-specific control variables;

GDP and FTALLSH—macroeconomic control variables.

The coefficient of our interest is α1 which measures the change in leverage due to the possession of a credit rating. We estimate EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) using first, pooled OLS regression with clustered standard errors by firms to control for the residual correlation across years for a given firm.

One of the major concerns with the pooled OLS estimation technique is the omitted variable problem. It is possible that the estimates of coefficients derived from the OLS regression may be subject to omitted variable bias. To mitigate the omitted variable problem we can use panel regression estimation methods, such as random effects or fixed effects techniques. If the omitted variables are uncorrelated with the explanatory variables in the model then a random effects model is the most appropriate technique. However, if the omitted variables are correlated with the variables in the model, then a fixed effects estimation will most likely provide the best means for controlling for omitted variable bias. In our setting, it is possible that there is an unobserved explanatory variable, which cannot be controlled for, that affects the dependent variable. This suggests a fixed effects estimation. This technique is also more appropriate when there is a relatively small cross-section and a lengthy time-period, which fits the characteristics of our panel dataset.Footnote2

In all models leverage is regressed on a set of firm characteristics to control for firm’s demand-side factors and a proxy for bond market access (credit rating dummy) to control for the supply of debt. Leverage is measured as a ratio of gross total debt to market value of assets. Bond market access is proxied by a possession of a credit rating. Firm characteristics include factors most commonly used in the capital structure literature: firm size, firm age, asset tangibility, profitability, market-to-book ratio, and spending on R&D. We also include asset volatility and firm’s equity return as two additional control variables. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) suggest that maturity of debt is positively associated with leverage, since public debt tends to be of longer maturities. Following Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) we incorporate the portion of short-term debt to control for debt maturity. In our analysis we also control for debt tax shield effects. We estimate our specifications with and without firm size. presents results from pooled OLS with cluster standard errors and panel estimation techniques from EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) .

Table 2. The impact of bond market access (measured by credit rating) on leverage: Pooled OLS and panel estimation methods.

The key variable of interest in our analysis is the credit rating dummy. The results in show that the coefficient on the credit rating dummy is positive and highly statistically significant across all specifications. After controlling for firms’ demand for debt we find strong evidence that firms with a rating have between 3% (OLS results) and 4.6% (Panel results) higher leverage ratios compared to their unrated counterparts.Footnote3 Our coefficient is lower than the 8% reported by Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) for US firms and 6% found by Mittoo and Zhang (Citation2008) for Canadian firms, but is slightly higher than Leary’s (Citation2009) coefficient on predicted probability of having a bond rating 2.8% (Leary Citation2009: 1179).

The coefficients on the firm characteristics are generally consistent with the extant literature, except for the coefficient on the size variable, which is negative. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) and Leary (Citation2009) also find a negative relationship between size and leverage. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) suggest that this could be explained by the positive correlation between size and credit rating and by using total debt-to-asset ratio, whereas some of the previous papers use long-term debt to assets. Similar to Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) we use total debt-to-asset ratio as a measure of a firm’s leverage. Leary (Citation2009) also find’s a negative coefficient on size when he uses the predicted rating probability to proxy for bond market access. We replicate models (1), (2) and (3) without size.

We find strong evidence that age and leverage are positively related. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006), however, find strong negative relationship between age and leverage in their study. We find a negative relationship between leverage ratios and profitability as measured by return on invested capital. This is consistent with the notion that more profitable firms rely less on external funding and use retained earnings for financing purposes. Tangible assets can serve as collateral when raising debt and therefore firms with more tangible assets are likely to have higher leverage ratios. Our results mirror previous studies in that we provide strong evidence that tangible assets are positively related to leverage across all specifications. We find some evidence that firm’s leverage ratios and market-to-book ratio are inversely related, however, our coefficient on R&D spending is not significant.

We measure riskiness of operations by asset volatility, which is calculated by multiplying standard deviation of daily equity return by the equity-to-asset ratio. Firms with more volatile assets are expected to have higher probabilities of default, and therefore, lower leverage ratios. As predicted the coefficient on asset volatility is negative and highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). Following Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) equity return over the previous year is included to account for partial adjustment in the firm’s capital structure. They argue that following an increase (decrease) in its equity value a firm should make a corresponding adjustment of debt in order to maintain its debt-to-asset ratio, otherwise the firm will de-lever. The coefficient on equity return is negative and statistically significant across all six specifications (p < 0.01), indicating that an increase in firm’s equity over the past year lowers its leverage ratio.

Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) suggest that rated firms issue bonds that tend to have longer maturities than private debt. Unrated firms, on the other hand, find it difficult to access public markets and are more likely to raise short term financing from private investors such as banks. To examine this we include the fraction of short-term debt that is due in one year including current portion of long-term debt due within one year. Consistent with our a priori expectation, the coefficient on short-term debt is negative and highly statistically significant.

One of the benefits of debt for firms is the tax shield effect. Firms with higher marginal tax rates should have higher interest tax shields, and therefore should be more leveraged. We use average tax rates to proxy for marginal tax rates. Contrary to the prediction, the coefficient on tax paid is negative and statistically significant. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) also find negative and significant coefficient on their marginal tax rate.

Similar to Leary (Citation2009), in addition to the firm-specific variables that control for firms’ demand for debt, we include macroeconomic variables that control for time-specific conditions that can influence the capital structure decision of a firm. Following Leary (Citation2009) we include two proxies for macroeconomic conditions in all our models: annual GDP growth rate and annual stock market return.Footnote4 The coefficient on our annual stock market return variable is negative and statistically significant in all specifications. Consistent with the market timing theory this indicates that following favorable stock market conditions firms issue less debt and more equity. According to Huang and Ritter (2004) who test the market timing theory of capital structure, firms issue equity when the relative cost of equity is low, and issue debt otherwise. The coefficient on annual growth in GDP is also negative and significant, which is in line with the arguments presented for favourable stock market conditions. Leary’s (Citation2009) coefficients on macroeconomic variables vary in signs. In summary our key finding is that firms with access as measured by a possession of credit rating have higher leverage ratios compared to their unrated counterparts.

3.2.3. Robustness tests: alternative measures of access

To verify that our results are not driven by the way we measure access (credit rating) and are robust to using alternative measures of public debt market access, we re-estimate EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) using three additional measures of access based on the book value of assets distribution:

Top30%–Remaining70%

Top30%–Bottom30%

Rated—30%Small

presents results from both Pooled OLS and Panel estimation techniques.

Table 3. The impact of access (measured by Size30–Remaining70, Size30–Bottom30, Rated—Small 30%) on leverage: Pooled OLS and panel estimation methods.

In the key variable of interest is access measured by the firm size dummy. Following Leary (Citation2009) we do not include a variable proxying for firm size in these specifications due to high correlation between our proxy for access and firm size:

Correlation between size and Top30%–Remaining70% = 0.66

Correlation between size and Top30%–Bottom30% = 0.85

Correlation between size and Rated—Small30% = 0.85

The results from are generally consistent with the results in . Whether we measure access by the possession of a credit rating or firm size, firms with bond market access have higher leverage ratios. When we measure access by Top30%–Remaining70% (columns 1–3) we find that firms with access have about 2% more leverage (OLS and RE). When we measure access by Top30%–Bottom30% (columns 4–6) we find that firms with access have between 2–4% more leverage (OLS and RE). When the possession of a credit rating is benchmarked against the smallest 30% of firms in our sample we find that the leverage difference between firms with and without access is greater (firms with access have between 6–7% more leverage), suggesting that firms without access are more credit constrained than firms with access. Coefficients on the demand-side characteristics coefficients are consistent with the results in .

4. Addressing endogeneity

4.1. Instrumental variable method

In our study, we control for the possible endogeneity of the firms' decision to possess a credit rating. Endogeneity arises when credit rating is correlated with the error term, thereby violating the exogeneity assumption. As a result OLS estimates can be biased and inconsistent. If there is a firm-level factor that affects a firm's decision of possessing a credit rating and also determines its leverage that we do not observe, then our coefficients from OLS and panel regressions can be biased. To control for the potential endogeneity we first use 2SLS instrumental variables (IV) estimation.Footnote5 We use two methods to estimate our model using instrumental variable approach. In the first method we use a probit specification in the first stage to estimate the probability of possessing a credit rating.Footnote6 In the second stage we use the predicted probability for possessing a credit rating from the first stage probit regressions to estimate the impact of having a rating on firm’s leverage.Footnote7 Bascle (Citation2008) however suggests that researchers should refrain from using a probit or logit method when the endogenous variable is binary and use a linear regression instead. He argues that this method will give consistent estimates in the second stage, whereas estimates obtained from a probit and plugged in the second stage will not be consistent unless the non-linear model is exactly right (Bascle Citation2008, 217–218). In the second method we therefore estimate our model using a linear regression in the first stage instead of probit and compare these results to the ones obtained using a probit regression.

In both IV estimations the first stage involves regressing the endogenous variable (credit rating dummy) on exogenous regressors (firm-level factors) plus instruments. In the context of this work instruments are variables that are related to whether a firm has a credit rating but are not directly related to a firm’s demand for debt (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006). We follow the literature to identify the variables that need to be included in the first stage estimation of the determinants of having a rating. An and Chan (Citation2008), Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) and Liu and Malatesta (Citation2005) suggest that the possession of a rating is likely to be related to size, profitability, growth opportunities and the tangibility of a firm's assets. For example, An and Chan (Citation2008) point out that large firms are more likely than small firms to have a credit rating due to the large fixed cost of issuing public debt and securing a credit rating. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) note that firms need to be of a certain minimum size to make it cost effective to issue capital market debt.

Liu and Malatesta (Citation2005) argue that firms with low profit levels and therefore a high risk of default are less likely to use public debt because of the higher costs in financial distress of negotiating with wide ranging public debt holders than with a group of private debt holders. An and Chan (Citation2008), however, make an opposite prediction in relation to firm profitability and suggests that more profitable firms are less likely to get a rating since they have more internal funds and thus lower demand for external funds such as bond market debt.

Growth opportunities are measured by R&D expenditure and market-to-book ratio and are expected to be negatively related to having a rating as firms with higher growth opportunities tend to use private debt rather than public debt (An and Chan Citation2008). An and Chan (Citation2008) argue that it is easier for firms with more tangible assets to issue public bonds and therefore obtain a rating as tangible assets serve as a collateral when issuing debt. Additionally, An and Chan (Citation2008) and Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) argue that firm age might also be an important determinant of whether a firm has a rating or not as more mature firms have a better track record of issuing debt, hence, they are more likely to get a rating.

For our first instrument we include variables that measure the percentage of firms in a given industry with a credit rating. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) argue that if more firms in an industry have public debt and therefore a rating the easier it is for firms to issue public debt because the bond market possesses greater knowledge about this industry which lowers the costs of collecting information for a bond underwriting. We use the percentage of firms in the industry and the natural log of 1 plus the percentage of firms.

For the next two instruments we use indicators of how well a firm is known to the market. Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) argue that the more known a debt issuer is the easier it is for a bank to introduce the firm to the capital markets and therefore the more likely the firm will raise public debt and thus require a credit rating.Footnote8 In this study we use two measures of firm visibility. These are:

Whether the firm is in the top 30% of firms according to market capitalization. Larger firms have higher probability having a rating due to large costs associated with issuing a rating.

Whether it is cross-listed in the United States. A firm that is cross-listed in the US is going to be visible to potential investors in the US capital markets, which includes the world’s largest public debt market. A cross-listing in the US establishes name recognition of the firm in the US capital market, thus paving the way for the firm to source new equity or debt capital in this market. Therefore as well as promoting firm visibility we would argue that firms that are listed in the US are more likely to source the US capital markets for debt funding. Furthermore, since in order to source debt funds in the US firms require a rating from a recognised credit rating agency, we would expect cross-listed firms to more likely possess a credit rating.Footnote9 In this study we use the existence of American Deposit Receipts (ADRs) as an indicator of having a listing on the US exchanges.

4.2. Instrumental variable regression results

We report our results from the 2-SLS IV regression and a standard OLS IV approach in . In columns 1–2 we present results from the first stage probit regression; in columns 3–4 we present results from the second stage IV regression;Footnote10 and in columns 5–6 we present results from a standard OLS IV regression.

Table 4. Instrumenting for having a rating: 2SLS IV regression (probit based method and method based on linear regression in the first stage).

Our results in , columns 1 and 2, show that the more firms in a given industry have a rating the higher the probability of a firm in that industry to have a debt rating and that larger firms are more likely to possess a credit rating. This is consistent with Faulkender and Petersen's (Citation2006) results. Having an ADR is positively correlated with having a debt rating, and the relationship is statistically significant (p-value < 0.01). Our instruments possess good statistical properties for an instrument in the first stage. Furthermore first stage F-statistics are considerably greater than 10 (F-stat = 684.79) (as a rule of thumb for a single endogenous regressor), hence we can conclude that our instruments are very strong.

Similar to Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) we find that some of our firm-level factors that are associated with higher leverage ratios are also related to the possession of a credit rating. Older firms are more likely to have a rating. However contrary to Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) we do not find evidence in support that firms with more tangible and less volatile assets have access to bond markets. An and Chan (Citation2008) also do not find support for positive relationship between asset tangibility and credit rating. We find that profitability is positively and significantly related to rating, which is contrary to the findings of Faulkender and Petersen (Citation2006) and An and Chan (Citation2008), however is consistent with the argument of Liu and Malatesta (Citation2005) that firms with low profitability tend to avoid issuing public debt. We also find evidence in support of rated firms having less short-term debt in their structure, which is consistent with the notion that rated firms have access to debt of longer maturities.

After instrumenting for having a rating our results from the second stage IV regression show that rated firms have higher leverage ratios. Possession of a credit rating increases firm leverage by 5.7% (columns 3 and 4, ). When we use linear regression instead of probit in the first stage, the effect of credit rating on leverage ratios is even larger, 6.7%.

4.3. Treatment effects method

According to Bascle (Citation2008) measurement errors in dummy variables cannot be adequately addressed with traditional IV methods like the 2SLS estimation (Bascle Citation2008, 287). If there is a self-selection problem then an alternative method, such as a Heckman-type model, should be used in conjunction with the IV approach. Self-selection occurs when firms in our sample are not randomly selected into the rated category. When self-selection is present the parameter estimates from the ordinary OLS regression model will be inconsistent and biased. An and Chan (Citation2008) argue firms to some extent determine whether they obtain a rating by assessing the costs and benefits of possessing a rating. Firms choose to have a rating if the benefits of having a rating, such as having access to the public bond markets, offset the costs of acquiring and maintaining a rating. Therefore the rating dummy variable is not statistically independent of leverage. Liu and Malatesta (Citation2005) also mention that credit ratings arise endogenously as a consequence of a decision made between firms and rating agencies, which can lead to biased estimates of the effect of having a credit rating on leverage.

To account for self-selection bias in our analysis we use a treatment effect model. Treatment effect is a Heckman-type model which is relevant to our analysis as our sample includes firms with and without credit rating, i.e. CreditRating dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when a firm has got a rating and CreditRating dummy variable that equals to zero otherwise. This method was also used by An and Chan (Citation2008) and Liu and Malatesta (Citation2005) to address self-selection problem in their analyses.

The treatment effect model consists of two stages. Following An and Chan (Citation2008) and Liu and Malatesta (Citation2005) we first estimate a selection equation, which models a firm’s decision to receive a rating:

(2)

(2)

CreditRatingit = 1 if CreditRating*it >0, and CreditRatingit = 0 otherwise

Prob(CreditRatingit = 1) = Ф(γZit)

Prob(CreditRatingit = 0) = 1 − Ф(γZit)

When CreditRating*it > 0, CreditRatingit = 1: Leverageit = δ0 + λ(γZit + uit) + δ1Xit + εit

When CreditRating*it≤ 0, CreditRatingit = 0: Leverageit = δ0 + δ1Xit + εit

where Zit are a set of observed variables that affect the probability of a firm being rated; uit is an error term with mean zero and variance equal to one; Ф(γZit) is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal random variables. Zit includes instrumental variables and other firm-level factors associated with having a rating. We use the same instrumental variables for the selection equation in this section as in the previous instrumental variable section 4.1. These include: 1. the percentage of firms in a given industry with a credit rating, and the natural log of 1 plus the percentage of firms; 2. two measures of firm visibility: whether the firm is in the top 30% of firms according to market capitalisation; 3. whether it is cross-listed in the United States.

In the second stage we estimate the following regression equation:

(3)

(3)

where Xit is a set of exogenous firm-specific variables;

CreditRatingit is a dummy variable equal to one if the firm has a credit rating and 0 otherwise;

εit is an error term with zero mean and variance equal to one.

Similar to the previous section we include macroeconomic control variables and industry dummies in the model.

The coefficient of interest is λ, which measures the average effect of possessing a rating on a firm’s leverage. By using a treatment effects model, we can estimate the regression coefficients λ on our endogenous dummy variable CreditRating by using the observed variables Zit. We estimate a treatment effect model using both the maximum likelihood estimator and a two-step procedure.

reports the results using a treatment effect maximum likelihood estimator and a two-step procedure. The first stage results (columns 1, 3, 5 and 7) suggest that all our instruments are positively and significantly related to leverage. They show firms that operate in industries with higher proportions of rated firms and those with higher visibility, measured by firm size and cross-listing in the US, are more likely to have credit ratings. Consistent with our expectation we find that older firms are more likely to possess a credit rating. However, contrary to our prediction we find that more profitable firms are more likely to have a credit rating, which is consistent with the result in the Instrumental Variable section. The coefficient on short-term debt is negative and significant, providing evidence that rated firms have less short-term debt in their capital structure.

Table 5. Treatment effects model: MLE and two-step estimation methods.

Our second stage results in suggest that applying the treatment effect model is appropriate. Columns 1–4 report results from the treatment effect MLE. Here we test the hypothesis that the correlation coefficient between the error term of the regression Eq. (2.3) and the error term of the selection Eq. (2.2) equal to zero, i.e. corr(eit,uit)=ρ = 0.The values of the chi-square test are χ2= 9.63 (p < .001) and χ2= 8.62 (p < .001). We can therefore reject the null hypothesis at a statistically significant level (columns 1–4) and conclude that the correlation coefficient rho (ρ) is not equal to zero. This result suggests that there is a self-selection bias and justifies the use of the treatment effect model. Columns 5–8, , report results from the two-step treatment effect model. In this estimation one of the key parameters is the inverse Mills ratio. The inverse Mills ratio, denoted as lambda, (lambda, column 6 = −0.0159*** and lambda, column 8 = −0.0151***) also confirms that there is a selection bias.

The goodness of fit of the model is given by the Wald test of all coefficients in the regression model being equal to zero. In all our treatment models the Wald test is large and significant at 1% level (χ2 = 7485, p < .0001). We can therefore conclude that at least one of the variables used in the regression model is not equal to zero and the variables fit the model well.

Consistent with our previous results firms with a credit rating have more leverage. The estimated coefficients on a credit rating dummy are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. The results suggest that credit ratings by providing access to capital markets increase debt and lead to higher leverage ratios. The coefficients on the control variables are mostly consistent with the previous results. Firm size is positive but insignificant. Older firms with more tangible assets have more leverage. Firms with higher growth opportunities measured by market-to-book ratio have less leverage. The coefficient on R&D expenditure is not significant. Our results show that profitability, the level of short-term debt, equity return, asset volatility and tax paid are negatively related to leverage consistent with our previous results.

5. Conclusion

This paper examines the role played by credit ratings in determining capital structure choice for a large sample of UK non-financial firms. A credit rating benefits firms not only by providing access to local public bond markets, but having a rating from one of the major agencies (S&P or Fitch) gives an opportunity to issue bonds in the international debt capital markets. For UK firms this is especially important, since a rating can ‘open the door’ to the U.S. capital market—the largest and most liquid source of debt capital.

The empirical analysis in this study utilises data over a 22 year period from 1989 to 2010. In line with the empirical literature (Faulkender and Petersen Citation2006; Kisgen Citation2007; Leary Citation2009) public debt market access is measured by the possession of a credit rating and firm size dummies. Using both pooled OLS and panel regression methodology our results indicate that firms with access to public debt markets have higher leverage ratios after controlling for demand-side determinants of capital structure. The empirical results demonstrate that supply side factors are an important determinant of capital structure choice for UK non-financial firms. The results suggest that for the full sample of firms the possession of a rating increases leverage by around 4 per cent for UK firms over the period 1989 through to 2010. When we restrict our sample to rated firms and those in the bottom 30 per cent of the firm size distribution the effect of having a rating on leverage is much greater, with the rating coefficient ranging between 5.7 and 7.2 per cent. When we control for endogeneity of having a rating our results remain qualitatively similar. After instrumenting for having a rating we find that the coefficient is around 5.5–6.7 per cent. When controlling for self-selection bias we find that rated firms have around 5 per cent higher leverage. Overall, our results show that access to bond markets as measured by the possession of a credit rating had an economically and statistically significant positive effect on the level of leverage for UK firms over our sample period.

The effect of possessing a rating on leverage reported in this study is larger than the 2.8 per cent found by Leary (Citation2009) in a comparable study that employs a sample of US firms during the period 1965 to 2000. This difference might be in part due to differences in the composition of the samples employed in our study or the period under investigation, compared to that of Leary (Citation2009). For example, our period, 1989 to 2010, incorporates two recessions and three episodes of severe credit market tightening, whereas the years covered by Leary (Citation2009) were relatively benign when it comes to credit market conditions according to the US Federal Reserve Loan Officer data. We would expect the importance of having a rating to be greater during tighter credit markets. Alternatively, it might also be due to differences in the level of corporate disclosure between the UK and the US. It has been suggested that US companies have a relatively easy time raising external finance and enjoy a highly liquid capital market because the United States imposes fairly stringent disclosure laws. In the US the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) set the rules for corporate disclosure. These rules require substantial disclosure of financial information and regular reporting to the SEC. Thus, the US is a richer reporting environment with strong monitoring and regulation. Although reporting and disclosure standards in the UK are rigorous they are not as stringent as those in the US. In markets where there is less disclosure investors will be less willing to buy stock at higher prices, market liquidity is likely to be lower, and debt capital for corporate expansion will be more difficult to raise. Given that there is far greater corporate financial transparency in the US compared to the UK it follows that the additional financial information released to investors from having a rating is likely to be greater in the UK than the US. All else being equal this would result in greater debt access effects from having a rating in the UK. Another explanation for the higher debt rating effect we find is that leverage levels on average in the UK are lower than those in the US. For example, Rajan and Zingales (Citation1995) report that firms in the UK are ‘substantially less levered’ than their counterparts in the US. It follows that if UK firms are starting from a lower base the incremental impact on leverage due to having a credit rating would be greater for UK than US firms.

An important implication of our findings is that as having a credit rating (i.e. access to debt capital markets) increases firm leverage it could have a positive impact on firms investment spending decisions. Firms without a rating could find themselves financially constrained and therefore not fully able to undertake the investment opportunities available to them. Perhaps more so during a period of credit market tightening when you might find that bank lending has contracted. We leave it to future research to examine whether access to capital market debt via a credit rating plays an important role in explaining firm investment.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Standard and Poor’s and Fitch Ratings for providing us with credit rating data. We thank an anonymous referee for useful comments and suggestions. Thanks also to Ian Stewart, John Grout, Blaise Ganguin, Aneel Keswani, Marian Rizov, David Kernohan and Valeria Unali for their suggestions. We thank seminar participants at the University of Santiago de Compostella, Cass Business School, University of Porto, ISCTE Business School, Bank of England, Standard and Poor’s, Joint Seminar at the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and HM Treasury, GdRE Symposium on Money, Banking and Finance at Reading University and Middlesex University for helpful comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimer applies.

Notes

1 Results are available from the authors upon request.

2 As a robustness test we also estimate each specification using a random effects model. To test whether the results (i.e. the estimated coefficients) from the fixed effects and random effects model are significantly different we run a Hausman test.

3 A Hausman test suggests that the coefficients of our FE and RE model are different and so the RE estimator is inconsistent. We therefore prefer the FE estimation. This also suggests that there is omitted variable bias that the RE model has not accounted for whereas the FE model has.

4 Leary (2009) includes three macroeconomic control variables: growth in GDP over the previous year, aggregate nonfinancial corporate profit growth and the equity market return.

5 We note that the General Methods of Moments (GMM) Arellano and Bond estimator is not valid on a long panel in the time dimension. If many firms of the sample are present during more than 10 consecutive years, the GMM method will lead to too many instrumental variables.

6 Following Faulkender and Petersen (2006) we use Probit estimation method in the first stage due to our credit rating variable being a dummy, instead of a standard instrumental variable estimation where first stage is a linear probability model. According to Faulkender and Petersen (2006) a linear probability model in the first stage would not work as this is a misspecification of the data, whereas the Probit method should give consistent coefficients and correct standard errors.

7 This method was used by Faulkender and Petersen (2006) and An and Chan (2008) to control for endogeneity of having a rating.

8 Faulkender and Petersen (2006) use whether a firm is in the S&P 500 and whether it trades on the NYSE as proxies for firm visibility and therefore as instrumental variables.

9 Two formal credit ratings are required to issue a public bond in the US debt markets.

10 Following Faulkender and Petersen (2006) and An and Chan (2008), we use the predicted probability of first stage Probit estimation as an instrument in the second stage of the estimation.

References

- An, H., and K. C. Chan. 2008. Credit Ratings and IPO Pricing. Journal of Corporate Finance 14 (5): 584–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2008.09.010.

- Antoniou, A., Y. Guney, and K. Paudyal. 2008. The Determinants of Capital Structure: “Capital Market Oriented versus Bank Oriented Institutions”. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 43 (1): 59–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109000002751.

- Bacon, G., J. Grout, and M. O’Donovan. 2009. “Credit Crisis and Corporates – Funding and Beyond”. Report by The Association of Corporate Treasurers, February. https://www.treasurers.org/ACTmedia/ACTReport-creditcrisis-and-corporates.pdf

- Bancel, F., and U. R. Mittoo. 2004. The Determinants of Capital Structure Choice: A Survey of European Firms. Financial Management 33: 103–132.

- Barnett, A., and R. Thomas. 2013. Has Weak Lending and Activity in the United Kingdom Been Driven by Credit Supply Shocks. Bank of England Working paper No. 482, December 2013. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Document/workingpapers/2013/wp482.pdf.

- Bascle, G. 2008. Controlling for Endogeneity with Instrumental Variables in Strategic Management Research. Strategic Organization 6 (3): 285–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127008094339.

- Boot, A. W. A., T. T. Milbourn, and A. Schmeits. 2004. Credit Ratings as Coordination Mechanisms. Working Paper, University of Amsterdam, January 29. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=305158

- Byoun, S. 2011. Financial Flexibility and Capital Structure Decision. Working Paper, Baylor University, March 19. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=1108850

- Booth, L., V. Aivazian, A. Demirguc-Kunt, and V. Maksimovic. 2001. Capital Structure in Developing Countries. The Journal of Finance 56 (1): 87–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00320.

- Butt, N., and A. Pugh. 2014. Credit Spreads: Capturing Credit Conditions Facing Households and Firms. Banks of England Quarterly Bulletin 54 (2): 137–147. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q203.pdf.

- Chava, S., and A. Purnanandam. 2011. The Effect of Banking Crisis on Bank-Dependent Borrowers. Journal of Financial Economics 99 (1): 116–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.08.006.

- Eades, K. M., and R. Benedict. 2006. Overview of Credit Ratings. Case and Teaching Paper, University of Virginia. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=909742

- Faulkender, M. W., and M. A. Petersen. 2006. Does the Source of Capital Affect Capital Structure? Review of Financial Studies 19 (1): 45–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhj003.

- Farrant, K., M. Inkinen, M. Rutkowska, and K. Theodoridis. 2013. What Can Company Data Tell Us about Financing and Investment Decisions. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 53 (4): 361–370. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2013/qb130407.pdf.

- Frank, M. Z., and V. K. Goyal. 2007. Capital Structure Decisions: Which Factors Are Reliably Important? University of Minnesota, Working Paper. October 10. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=567650

- Graham, J. R., and C. R. Harvey. 2001. The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance: Evidence from the Field. Journal of Financial Economics 60 (2–3): 187–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00044-7.

- Harris, M., and A. Raviv. 1991. The Theory of Capital Structure. The Journal of Finance 46 (1): 297–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb03753.x.

- Hovakimian, A. G., A. Kayhan, and S. Titman. 2009. How Do Managers Target Their Credit Ratings? A Study of Credit Ratings and Managerial Discretion. Working paper, Zicklin School of Business, April 29. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=1098351

- Huang, R., and J. Ritter. 2004. Testing the Market Timing Theory of Capital Structure. Working Paper, University of Florida, September 15. https://www3.nd.edu/∼pschultz/HuangRitter.pdf

- Huang, Y. L., and C. H. Shen. 2015. Cross‐Country Variations in Capital Structure Adjustment. The Role of Credit Rating. International Review of Economics & Finance 39: 277–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2015.04.011.

- Kemper, K. J., and R. P. Rao. 2013a. Do Credit Ratings Really Affect Capital Structure? Financial Review 48 (4): 573–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/fire.12016.

- Kemper, K. J., and R. P. Rao. 2013b. Credit Watch and Capital Structure. Applied Economics Letters 20 (13): 1202–1205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2013.799746.

- Kisgen, D. J. 2006. Credit Ratings and Capital Structure. The Journal of Finance 61 (3): 1035–1072. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00866.x.