ABSTRACT

A substantial literature demonstrates that in advanced democracies the public generally prefer for MPs to be focused on their constituencies. However, prior research fails to prove that the general public is aware when MPs are doing so, and whether their views of the MP change correspondingly. I test this using a high-quality proxy for constituency focus – talking about the constituency in the House of Commons – linking this to British Election Study survey data on perceived constituency focus and trust. I show that ‘real' constituency focus strongly predicts perceived constituency focus and also predicts trust. As expected, these effects exist only for constituents who know (recall) their MP's name. While previous studies argue that the public want ‘workhorses' who offer ‘value for money’ by speaking in Parliament, I instead suggest that the focus, not the volume, of activity can be a more productive route for MPs to develop trust.

Introduction

The ‘focus’ of representation is one of the most familiar concepts in the study of the democratic process. One of the available ‘foci’ for representatives is their constituency, and surveys suggest that in many Western democracies MPs make the constituency their principle focus. Research has uncovered how representatives are often expected to focus on their constituencies, and that people especially value representatives who perform the role of ‘local promoter’, advocating for their constituency on a national stage. These studies have made significant contributions to our understanding of both the demand-side and supply-side of constituency focus. However, demand and supply have largely been studied in isolation from each other. Consequently, little is understood about whether constituency focus leaves the impression on the public that would be predicted from these literatures. Indeed, there is some reason to doubt that constituents notice their MPs’ activities at all.

This question is highly pertinent because of the substantial turn towards a constituency focus among MPs: something especially well documented for this article’s specific case, the UK. This shift has occurred in response to both growing demand and supply. Searing (Citation1994) identifies the expansion and nationalisation of the post-war welfare state as a key factor in increasing demand. Citizens’ encounters with the state became more frequent, sometimes more complicated, and the fact that services were often organised at the national level meant it made sense to refer issues to MPs, who could have an influence at that level. On the supply-side, MPs, observing the gradual ‘dealignment’ of British politics, saw that they could rely less on voting blocs, and felt increasingly incentivised to build a personal vote through constituency focus (Zittel, Citation2017). To these accounts, we might add two more recent trends. On the demand-side, post-2010 austerity has both added to constituent grievances and reduced alternative sources of advice and advocacy, swelling MPs’ caseloads (Fox, Citation2012). In terms of supply, there has been a tendency towards Parliament facilitating the discussion of constituency concerns. In 2010, the Wright Committee reforms created a Backbench Business Committee: constituency relevance is a criterion for selecting proposed business (Kelly, Citation2015).

This article addresses the effects of constituency focus, drawing together a measure of MPs’ constituency focus using their speeches in the House of Commons with high-quality survey data on evaluations of MPs. Despite the commonplace belief and media trope that MPs are ‘all the same’ (Crewe, Citation2015), there is a very wide spread between MPs in the proportion of ‘constituency-focused’ speeches (linked to factors such as tenure, marginality, and being a minister). These differences matter: I show that constituents do respond to MPs’ constituency focus. This occurs for a direct measure of perceived local focus, but also translates to a measure (trust) that has an intrinsic positive valence. However, each of these relationships are conditional on constituents knowing who their MP is. At the same time, I find no evidence that the overall effort MPs make to speak in Parliament (on any topic) has any effect on trust, while it may actually decrease perceived local focus.

Together, these findings have potentially important implications. They indicate that MPs need not present themselves as workhorses who give constituents ‘value for money’ by constantly attending Parliament, since the focus, not the volume, of activity is what affects trust. Further, they suggest that measures of representative ‘performance’ created for public benefit by Parliamentary Monitoring Organisations (PMOs) might consider taking account of the focus as well as the quantity of activity. However, the findings raise several important questions, including where effects occur, who is affected, and what they are really responding to.

Literature and theory

What is constituency focus – and how do MPs display it?

Although theoretical definitions have been proposed for understanding ‘constituency focus’, prior literature approaches this topic above all as a matter of how MPs undertake the practical business of being an elected representative. In the UK literature, the topic of constituency focus has largely been approached through inquiries into MPs’ role selection (Searing, Citation1994). Searing’s typology identifies four ‘informal, backbench’ roles: Policy Advocates, Ministerial Aspirants, Parliament Men and Constituency Members. The latter, he argued, were clearly identifiable through several characteristics: an orientation towards the local and away from the national, a sense of duty to constituents and a desire to feel competent through the small wins associated with constituency service and advocacy. However, recent scholarship has moved towards seeing MPs’ roles as more fluid (Rush & Giddings, Citation2011).

This shift is consistent with contemporary empirical work on representational focus. Although MPs may have some underlying preference over ‘focus’, they want to represent several ‘principals’ at once. For instance, in the 2009 PARTIREP survey of Westminster MPs, they gave high scores to the importance of representing ‘all people’, their party, their own voters, and the constituency (Dudzińska, Poyet, Costa, & Weßels, Citation2014). However, the simple practicalities of political life force them to emphasise some over others. The literature, for instance, highlights the importance of resource constraints in provoking decisions over ‘focus’. For example, in the United States, representatives must keep a full-time staff in their districts and Washington D.C., but have limited budgets. Studies have thus sought to access constituency focus through how the representative splits staffing between home and capital (Bond, Citation1985; Fenno, Citation1978; Fiorina & Rivers, Citation1989).

However, the most fundamental resource of MPs is time. This emerges particularly in Parliamentary debates, where, as Killermann and Proksch (Citation2013, p. 7) argue, there is a fundamental trade-off between using one’s time to participate in ‘government-opposition debate’ and for constituency representation. This trade-off is, however, not merely automatic, but part of an MP’s calculus in deciding what to say in the House: Crewe (Citation2015) finds that, in practice, raising local issues is often a means to avoid issues of national controversy. This basic insight contributes to my choice of the parliamentary record as the raw material for discerning MPs’ focus, building on other work about constituency focus (Blidook & Kerby, Citation2011; Bulut & İlter, Citation2018; Kellermann, Citation2016; Martin, Citation2011; Soroka, Penner, & Blidook, Citation2009).

However, my methodology differs in one important regard. In other studies, scholars have considered only a small subset of MPs’ oral contributions to give an indication of their constituency focus – such as their contributions to Canada’s Question Period (Soroka et al., Citation2009). Yet there are good reasons to instead consider their contributions as a whole. Crewe (Citation2015, pp. 84–86) highlights how nearly every kind of Parliamentary business can be an opportunity to talk about the constituency. The half-hour adjournment debate is the most common vehicle, and where MPs go into ‘greatest depth about a constituency concern or interest’. In budget debates, MPs often show interest in how a policy will affect constituents. However, ‘Even the lesser-known rituals provide opportunities’. At Business Questions, where the following week’s agenda is announced, backbenchers can raise any question, often ‘plugging constituents’ demands, requests or opinions’. Even Points of Order, which formally concern breaches of parliamentary rules, can be ‘harnessed to the constituency cause’.

Though I have centred on practice-oriented understandings, there is much to be gained from putting these in conversation with theory. ‘The focus of representation defines whom MPs represent’ (Deschouwer, Depauw, & André, Citation2014, p. 12), and constituency focus denotes how far MPs represent constituents above and beyond other possible groups. What it means to ‘represent’ is, of course, deeply contested and the previous discussion has illuminated how activities which highlight local focus fit with multiple conceptions of representation. For instance, ‘plugging constituents’ demands’ could be seen as delegate representation; discussing localised policy impacts sounds like substantive representation; and so on.

What, if any, is the common denominator of these activities? All of them entail ‘representative claims’, in which the MP aims to ‘give the impression of making present’ the (absent) constituents (Saward, Citation2010, p. 37). Constituency representation is in fact Saward’s first example of a representative claim: ‘the MP (maker) offers himself or herself (subject) as the embodiment of constituency interests (object) to that constituency (audience)’. When quantified in the way I set out here, what is measured is the cumulative strength of the claim to constituency representation that is being made. This is not inconsistent with the idea of constituency focus as a role MPs select, but understands it as a role that is performed in the service of their claim, rather than embodied (Rai & Spary, Citation2019). A particular benefit of this conceptualisation is to avoid essentialising the constituency in the way that traditional subject-object formulations can fall victim to. It usefully acknowledges that the complexity of any given ‘real’ constituency, which will contain diverse and often conflicted groups (Crewe, Citation2015; Judge, Citation2014), will typically be downplayed or erased by such claims. For this reason, among others, claims can be ‘contested, rejected or ignored’ (Saward, Citation2010): it is a live question as to what impression an MP’s activities leave on their audience, to which this study may supply some partial and cautious answer.

Demand and supply for constituency focus

Internationally, where the public have been asked their preferences over ‘focus’, they have generally opted for constituency. Grant and Rudolph (Citation2004) find that a key priority for U.S. voters is that their Member of Congress ‘work on bills concerning local issues’. This is echoed for mainland Europe (André, DePauw, & Andeweg, Citation2018; Bengtsson & Wass, Citation2011), and the same appears to apply to the UK. Campbell and Lovenduski (Citation2015) find a substantial tendency towards preferring constituency-focused activity. Meanwhile, research by the Hansard Society (Citation2010, p. 101) showed that ‘representing the views of local people in the House of Commons’ was ranked first of ten activities as a desired priority for MPs. The fact that speaking for the constituency in Parliament had such weight is an important reason for the use of focus in speeches as an independent variable.

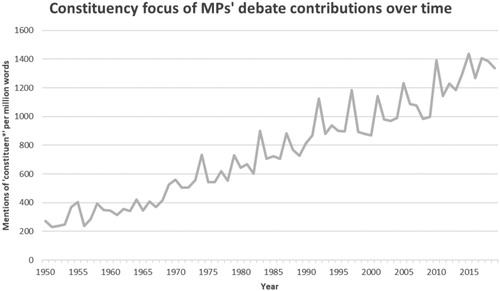

However, in the same Hansard Society survey, just 10 per cent of constituents felt this was one of MPs’ actual priorities. How fair is this assessment? The supply-side does not seem to be lacking: depending on the indicators used, elite surveys show that the UK comes out average or high in constituency focus compared to other Western democracies. Dudzińska et al. (Citation2014) and Heitshusen, Young, and Wood (Citation2005) find that UK MPs claim to give constituency their highest priority, though this does not make them exceptional. André, Gallagher, and Sandri (Citation2014) find that Westminster MPs are much more likely than those of other countries to adopt a ‘welfare officer’ role (helping individuals), although they are more average in how often they adopt a ‘local promoter’ role (representing the constituency as a whole). This is the product of a long-term trend towards constituency focus (Judge & Partos, Citation2018; Norris, Citation1997), which is also reflected in the content of their speeches: as shows, the relative frequency of mentioning constituency or constituent(s) increased nearly six-fold between 1950 and 2019.Footnote1

Figure 1. Constituency focus of all MPs’ debate contributions, 1950–2000 (words beginning constituen* in Hansard per million words by year).

Nonetheless, constituency focus has not been uniformly adopted. André, Depauw, and Martin (Citation2015) suggest that variation within Parliaments is more significant than variation across them. This is supported by André et al. (Citation2014), who use cross-national data from the PARTIREP survey of MPs. They find eighteen percent of the variance in constituency focus is at country level, and six percent at party level, implying that a large majority of variance is between individuals. Given that so many constituents expect local focus, this variance may be politically significant in shaping evaluations of the MP.

This is nonetheless conditional on MPs successfully publicising their activities. Crewe (Citation2015) discusses several ways MPs do so, such as press releases, websites and social media. This seems to be norm rather than exception: Franklin and Norton (Citation1993) found that four in five MPs who asked a written question stated that they notified their local newspaper. Indeed, some constituents might directly observe their MP contributing in the House on television, especially if it occurs in the more widely viewed setting of Prime Minister’s Question Time (Hansard Society, Citation2014). MPs certainly believe that some of their contributions ‘resonate with the people in their constituency’ (Tinkler & Mehta, Citation2016, p. 13). This is perhaps because they are confident about earning media coverage: in PARTIREP surveys, UK MPs estimated that on average, over two in five of the ‘initiatives (e.g. bills, written and oral questions)’ they raised in Parliament were reported (Midtbø, Walgrave, Van Aelst, & Christensen, Citation2014).

Do MPs’ activities matter?

Little research directly looks for effects of constituency focus on public evaluations of their MPs, and no such work at all exists for the UK. However, two U.S. studies find indications of a link. Grant and Rudolph (Citation2004) find that ‘constituency focus’ of U.S. House Members is associated with positive evaluations of the member. However, their measure of ‘constituency focus’ collapses indicators associated with traditional ‘constituency service’ together with indicators of constituency representation within the legislature, producing a single index, despite low correlations. As such, we remain in some doubt which activities truly matter to constituents.

Greater specificity is provided by Box-Steffensmeier, Kimball, Meinke, and Tate (Citation2003), who measure constituency focus by looking at the bills sponsored by House incumbents, calculating the percentage of bills addressing local concerns. Their results are mixed: members with proportionately more local bills had higher name recognition and higher vote intention, but their constituents were no more likely to mention anything that made them ‘like’ the member. An issue with this analysis, however, is that the focus measure is calculated from an infrequent activity, which means that variance in the focus measure is restricted: for instance, over one-quarter of members score zero for local focus, somewhat implausibly. Using more frequent activities is important to establishing sufficient variance in focus. The method of this study applies both these insights, clearly delineating Parliamentary from constituency activity, and using a highly frequent activity in Commons contributions.

Activity and perception: a simple theory

Given the above, we can set out some relatively strong prior considerations. UK MPs often have a constituency focus, and this is reflected in their activities, including their Parliamentary work: however, there is a large degree of variance between MPs. MPs often try to tell the public about what they are doing in Parliament, so it is plausible that the public uses these signals to form an impression about their MPs. The public generally expect MPs should be constituency-focused: in particular, they expect to see constituency focus in the MP’s Parliamentary work (moreso than through service). Finally, there is evidence that, at least in the U.S., constituency focus does have a bearing on how representatives are evaluated (although these studies have limitations). Considering this, I propose H1:

H1: The extent of constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity profile is associated with perceptions of constituency over national focus.

H2: The extent of constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity profile is associated with trust in the MP.

Which constituents respond? The role of minimal knowledge

It is generally recognised that some level of citizen knowledge is required for people to connect activity and perceptions. Some, such as Arnold (Citation1993, p. 405) contend that the required knowledge is not at all common. Loewen, Koop, Settle, and Fowler (Citation2014, p. 190) state that ‘only the most attentive voters are aware of representatives’ efforts’: a view supported by Stein and Bickers (Citation1994), who find that only 16 per cent of Americans could recall ‘something special’ achieved by their representative. Data from YouGov (Citation2013) suggests a similar picture for the UK: just 16 per cent stated that they knew ‘a lot’ or ‘a fair amount’ about what their member of Parliament did in Westminster.

However, this view may be excessively pessimistic. Constituents may not recall specifics, but may nevertheless have a sense for their representative’s activity. In the same YouGov survey, only one in three said that they knew ‘nothing at all’ about their MP’s activities in Westminster: the modal response was ‘not a lot’. Thirdly, it is possible that more minimal forms of knowledge enable activity to have an effect. As Navarro and Francois (Citation2018) argue, the most important condition for activity to have electoral rewards is simply ‘that the voters know who their representatives are’. Chiru (Citation2018) also states this as a necessary condition. For instance, if MPs’ activities matter because they earn media coverage for the representative, then knowing that who is being talked about is the local member may be all that is needed for constituents to link activity and evaluation. Therefore, I propose two further hypotheses.

H3: When constituents know the name of their MP, the association between the constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity profile and perceptions of constituency focus is positive and stronger than when constituents do not know the name of their MP.

H4: When constituents know the name of their MP, the association between the constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity profile and trust in the MP is positive and stronger than when constituents do not know the name of their MP.

Data and method

MPs’ constituency focus

To measure constituency focus, I utilise a method similar to that employed by Blidook and Kerby (Citation2011), Martin (Citation2011) and Kellermann (Citation2016). In this formulation, an MP’s constituency focus can be expressed by the number of their parliamentary contributions that mention the constituency as a proportion of their total contributions to parliamentary debates. As Martin (Citation2011) has discussed, what it means to talk about one’s constituency is not always easy to pinpoint. He identifies six categories of ‘constituency mentions’: (1) the constituency by name or reference, (2) geographic locations within the constituency, (3) individuals identified as constituents, (4) buildings or facilities within the constituency, (5) companies or organisations specific to the constituency, and (6) festivals or events within the constituency. As in other studies, some trade-off is generally required between a sufficiently comprehensive measure and a feasible and replicable measure.

I build on the approach of Kellermann, capturing contributions in categories (1) and (3) in close to their totality, and many contributions in category (2). While an ideal measure would capture within-constituency locations, buildings etc. more exhaustively, available databases in the UK context have limitations which are liable to perform unevenly across different geographical areas, inducing error (see Appendix 1 for an explanation of this issue). Given the risk of error, others (e.g. Middleton, Citation2019) have chosen to manually code MPs speeches, yet this is not practical given the size of the ‘corpus’ used here. It could be objected that a smaller corpus could be selected, by restricting to a smaller amount of time or a particular type of Parliamentary contribution: however, as argued above, it is important to have a large denominator to establish sufficient variance. Furthermore, being more selective builds in potentially incorrect assumptions: for instance, MPs’ constituency focus may vary over the course of a Parliamentary session (Rush & Giddings, Citation2011). Nonetheless, given the method’s limitations, I place significant emphasis below on validation.

Constituency mentions are identified in two ways, and a debate contribution which falls into either category is counted in the sum of constituency-mentioning contributions. First, by use of the words ‘constituency’ or ‘constituent(s)’, where it is clear that the reference is not being made to other MP’s constituencies or constituents.Footnote2 Second, by use of whole or part of the constituency name. Since MPs may not reference the whole constituency name, I decompose constituency names into a group of words, retaining only those which make specific local reference. I remove a set of common geographic references, such as compass directions, and typical ‘stopwords’ such as ‘the’. For instance, from the constituency name ‘Dulwich and West Norwood’, only the geographic identifiers ‘Dulwich’ and ‘Norwood’ are retained, such that appearances of either of those words in the text denote a ‘constituency-focused’ debate contribution.

Validation of constituency focus

To validate the measure, I first test for the expected relationships with Member and constituency characteristics. As Blidook and Kerby (Citation2011) find, MPs’ speech tends to be constituency-focused when their constituencies are more marginal.Footnote3 I find a strong relationship to constituency focus. Where Majority is the difference in vote share between the 1st and 2nd placed candidates at the prior election, for 614 MPsFootnote4, the correlation of constituency focus to Majority is r = −.26 (p < 0.001). I also test the association with being a backbencher rather than a Cabinet or Shadow Cabinet member (Kellermann, Citation2016): the differences are significant at the p < 0.001 level. Finally, I test whether more recently elected MPs are more constituency focused. The longer the MP had been representing the constituency in Parliament, the less constituency-focused they were (r = −.37, p < 0.001).Footnote5

A further validation leverages data on local and national media coverage across the same time period (2010–2015). A detailed explanation is available in Appendix 2. Constituency-focused MPs should consider constituents their most important audience, and thus appear more in local and less in national media. Furthermore, MPs who mostly talk about their local areas are probably less newsworthy to national newspapers (Amsalem, Sheafer, Walgrave, Loewen, & Soroka, Citation2017) but moreso to local newspapers. Indeed, I find that for 205 MPs where data on local and national media coverage is available, constituency focus is positively correlated with local newspaper quotes (r = .14, p < .01) and negatively correlated with national newspaper quotes (r = −.36, p < .001).

The ranking of least and most constituency-focused MPs is also face-value credible. Near the bottom are Ed Miliband and Jim Murphy, then-leaders of the UK Labour Party and Scottish Labour respectively, who would be expected to speak to the widest possible audiences. So too are many ministers and shadow ministers with security and international briefs, whose day-to-day work presumably has little constituency relevance.

Survey data

My survey data derives from the British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP) 2014–2019, a large-N online longitudinal study of the British electorate. Specifically, I use Wave Four (March 2015), which fielded a unique survey battery concerning knowledge and perceptions of local MPs. Carried out at the end of the 2010–2015 Parliament, this fits well with using MPs 2010–2015 speeches as the source for the independent variable.

Dependent variables

Two dependent variables are used. First, I use an item in which respondents were asked to place their MP on a scale of local-national focus, where one represents ‘focused on national issues’ and seven represents ‘focused on the constituency’.Footnote6 Second, I utilise a trust item, where one represents ‘no trust’ and seven ‘a great deal of trust’. For simplicity of presentation (especially of graphs), I treat this outcome as interval and use linear regression.

Name recall as a mediator

I utilise a name recall measure for whether people ‘know’ their MP’s name, included in the Wave 4 BESIP module. This requires substantial processing of the raw, ‘text-box’ data to generate the final binary variable, which is explained in Appendix 3.

Control variables

In terms of respondent demographics, I control for age, which reliably predicts positive evaluations of a local MP (Bowler, Citation2010; Costa, Johnson, & Schaffner, Citation2018; Frederick, Citation2008; Lawless, Citation2004). I control for gender, since some studies show women are more approving of their constituency representatives (Bowler, Citation2010; Gay, Citation2002). I also control for education (as measured by highest qualifications) – higher qualifications have occasionally been found to have negative effects on MP evaluations (Lawless, Citation2004) – as well as a three-category measure of occupational class derived from the NS-SEC.

I include a control for the relationship between one’s own party identification and the party they thought their MP represented: a consistent predictor in the literature. Respondents who thought their MP represented the party they supported were classified as ‘matching’; those who thought their MP represented a different party to theirs were defined as ‘clashing’. Two further categories denote respondents with no party identification and those who did not try to guess their MP’s party. Alongside parties, any realistic model must control for evaluations of politics and politicians more generally, which have large effects (Cain Ferejohn, & Fiorina, Citation1979; Bowler, Citation2010; Frederick, Citation2008). Thus, I control for trust in MPs ‘in general’.

I also control for respondents’ political attention: several studies support a link between attention (or similar variables) and positive evaluations of MPs (Box-Steffensmeier et al., Citation2003; Frederick, Citation2008; Parker & Goodman, Citation2009; Schaffner, Citation2006; although see Sulkin, Testa, & Usry, Citation2015). The final individual-level factor is recalled contacting of the MP, which, where included, consistently predicts positive evaluations (Cain et al., Citation1979; Wagner, Citation2007).

The more important set of controls relate to MPs’ own characteristics and activities, which are likely to be correlated with constituent evaluations and crucially with the constituency focus of parliamentary activity. More senior MPs are, in general, viewed more positively (Box-Steffensmeier et al., Citation2003; Parker & Goodman, Citation2009; Stein & Bickers, Citation1994; although see Branton, Cassese, & Jones, Citation2012), but may engage less in constituency-focused activities due to a sense of electoral security (Fernandes, Leston-Bandeira, & Schwemmer, Citation2018). As such, a control for seniority (in years) is essential. Leadership roles, such as ministerial positions, have sometimes been linked to more negative evaluations (Parker & Goodman, Citation2009), particularly where these evaluations concern constituency representation. Since ministers and shadow ministers are expected to be less constituency-focused (Kellermann, Citation2016), it is important to control for ministerial status. It is less clear how an MP’s majority relates to constituent evaluations: however, since electoral marginality is a major motivator of constituency focus (Heitshusen et al., Citation2005), this must also be controlled.

Results

Can MPs’ constituency focus affect public perceptions? shows the results of linear regression models of perceived local focus and trust, where positive coefficients indicate that higher values of the variable are associated with perceiving the MP as more locally-focused, or with higher levels of trust.

Table 1. Results of linear regression models of perceived local focus of MP and trust in MP, with and without interactions.

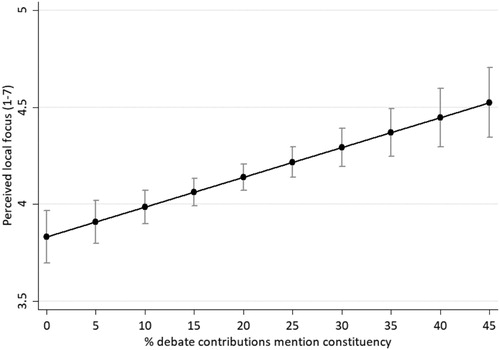

I first discuss the results for perceived local focus. Hypothesis 1 stated that as the constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity increases, perceptions of the MP’s constituency focus increase. I am able to reject the null: as shows, the main effect of constituency focus on perceived focus is positive and significant at the p < .001 level. I also confirm that adding the key independent variable improves the model fit, according to likelihood-ratio tests (p < .001).

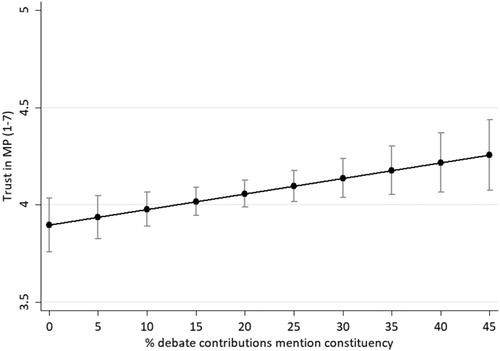

Does the same apply to trust? Hypothesis 2 stated that as the constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity increases, constituents’ trust in the MP increases. confirms that this is the case, and that we may reject the null hypothesis of no relation with 95 per cent confidence. Again, adding the key independent variable leads to a significant improvement in the model fit (p < .05).

The substantive size of effects is best indicated graphically. In , I plot the predicted value of perceived local focus, where a value of one represents the minimum and seven the maximum. I plot results from X-values of zero percent to forty-five percent, roughly the 95th percentile of constituency focus. The confidence intervals are relatively narrow, showing a high degree of certainty that evaluations of the MP differ over this range of X-values.

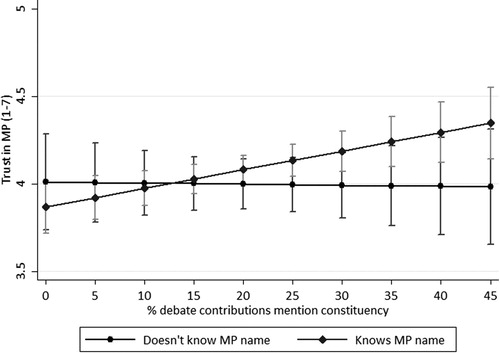

In , I plot the predicted value of trust in the local MP, which is identically scaled to perceived focus, again using the same range of X-values. The relationship is positive, though the slope is considerably flatter than for perceived focus.

However, although these results most closely approximate the effect of constituency focus on the public at large, they are likely to mask significant heterogeneity concerning who responds to MPs’ constituency focus. The literature suggests that effects are likely to be concentrated among people very high in political attention, though I have countered that a more minimal form of ‘competence’ may be sufficient. I have thus theorised one major moderator: knowing the name of one’s MP. therefore also reports, in Columns 2 and 4, the interaction effects between name recall and the constituency focus of the MP’s Commons contributions.

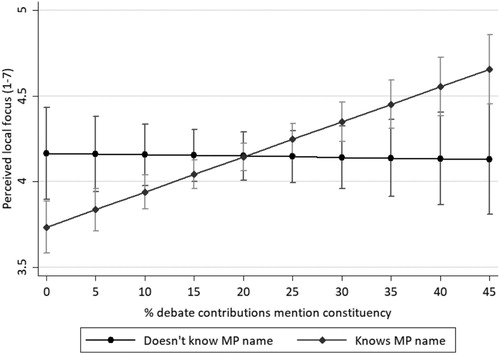

Hypothesis 3 stated that when constituents know the name of their MP, the association between the constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity and perceptions of constituency focus will be positive and stronger than for those constituents who do not know the name of their MP. supports this expectation. The interaction, where constituency focus is the dependent variable, is highly significant and in the anticipated (positive) direction: we can therefore reject the null. Using a likelihood-ratio test, model fit also improves compared to a model without the interaction (p < 0.001). Moreover, the main effect of constituency focus is indistinguishable from zero, such that the effect of constituency focus occurs only for those who know the name of their MP.

Note also that here, the main effect of name recall is negative, and highly significant (p < .01). More precisely, this represents the effect of name recall at the zero value of constituency focus. People who know their MPs, and who see them never talking about the constituency, develop more negative views than people who do not know their MPs at all.

As regards Hypotheses 1 and 2, the same relationship was found using either local focus or trust as dependent variable. Does the same apply for the interaction effect? Hypothesis 4 stated that when constituents know the name of their MP, the association between the constituency focus of an MP’s parliamentary activity and trust in the MP will be positive and stronger than for those constituents who do not know the name of their MP. No such interaction could be found at the p < .05 confidence interval, though at the more relaxed p < .1 confidence interval, there is such a relationship. Subgroup analysis suggests that the result for trust could be understood as a Type II error associated with the larger standard errors caused by interaction. Using only those respondents who knew their MP’s name [n = 1447], there was a significant effect of constituency focus on trust (β = .010, p < .01), but using those respondents who did not [n=490] there was no such effect (β = .001, p > .1).

What do these effects look like? shows plots the predicted value of perceived local focus, with separate predictions for those who do and do not know the name of their MP. The picture suggested by is confirmed here. The confidence intervals are somewhat higher, but they still show a strong degree of confidence that perceived local focus increases across values of an MP’s constituency focus. In line with the findings of , less clear conclusions can be drawn as concerns trust ().

Figure 4. Predicted value of perceived local focus by MP’s constituency focus and constituent name recall.

Figure 5. Predicted value of trust in local MP by MP’s constituency focus and constituent name recall.

In , we observe a cross-over point: when around twenty percent of an MP’s debate contributions mention their constituency, they are viewed as equally locally focused by both those who do and do not know their MP. Notably, the mean value among MPs is nineteen percent. It seems that, on average, MPs are sufficiently focused on their constituencies to avoid drawing the ire of knowledgeable constituents, but the generic MP does not make a strong impression.

Since the dependent variable should technically be considered an ordinal variable, it may be objected that treating it as interval, by using linear regression, may alter the results. For this reason, I re-specify models as ordered logits. The tables, and predicted probability plots for the main effects, are shown in Appendix 4. No substantive conclusions are affected by the type of regression chosen.

A potential challenge to these findings is as follows. MPs who devote more of their time to talking about the constituency are likely talking about constituency more in absolute terms as well as relative. Is it really the balance that matters? To rule out the possibility that it is the absolute number of times MPs talk about their constituency that is causing the effect, I run alternative models substituting in this variable for the ‘focus’ variable (see Appendix 5 for tables). For neither perceived focus, nor trust, do I find any effect. This differs from other findings: Chiru (Citation2018) used an ‘absolute’ measure – the total number of constituency-focused questions – and found significant effects on the personal vote in Romania.

It is also instructive to make a comparison with the effects of the quantity of debate contributions per se. This bears the closest analogy to, for instance, tests conducted by Bowler (Citation2010) and Kellermann (Citation2013), who show respectively that Private Members’ Bills and Early Day Motions contribute to MPs’ personal vote. It is also a useful exercise because some data collection and research is founded – implicitly or explicitly – on the view that MPs’ regular attendance in the House is desirable. For instance, Besley and Larcinese (Citation2011) use a ratio of expense spending to attendance at Parliamentary divisions as an indicator of ‘value for money’, while one of the key statistics reported by the website TheyWorkForYou, which helps the public monitor their MP, is the number of times an MP has spoken in debates.

Therefore, I substitute the ‘quantity’ variable for the ‘focus’ variable (Appendix 5). I find no effect on trust, but a significant negative effect on perceived focus: the more an MP spoke in the House, the less locally-focused they were seen to be (p < .001). This makes sense: very frequent speech in the House likely entails less time in the constituency. The implication is that time in the House can be valuably spent establishing a reputation for local focus, but too long in the chamber and they will face diminishing returns.

This study also represents an opportunity, given the controls included, to retest the broader findings of the existing literature on more up-to-date data and in the UK context. Demographics, for the most part, have the predicted effects. Older people and women were more likely to trust their MP, consistent with previous literature. Political engagement – both with politics in general and with the MP specifically – were also included as controls. Contacting one’s MP was correlated with trust, as would be expected from the literature (Cain et al., Citation1979; Wagner, Citation2007) though not with perceived local focus. Political attention, which was expected to be associated with trust, was not (and was in fact associated with perceived national focus).

The role of attitudes to politicians and parties broadly repeat expected patterns. As was assumed, a powerful determinant of evaluations – particularly of trust – was the ‘partisan match’ with the local MP. Those who identified with their MP’s party (or, more specifically, the party that they thought their MP belonged to), rated MPs higher in trust and local focus than those who identified with another party. Those with no party identification, however, trusted their local MPs nearly as little as ‘clashers’, although on local focus they rated them the same as ‘matchers’ did. Unsurprisingly, trust in MPs ‘in general’ was highly correlated with both perceived local focus and trust in the local MP, with the link to the latter being much stronger.

The previous literature also suggested a role for MP-level factors. Time-consuming national positions – such as being a minister or shadow minister – were expected to diminish perceived constituency focus and trust. However, this did not transpire. On closer inspection, these non-effects occur because the variable for ‘real’ constituency focus is included: before controlling for ‘constituency mentions’, frontbench MPs are indeed seen as less constituency-focused (though not less trusted). Seniority, on the other hand, was expected to increase trust (even though senior MPs are generally less focused on constituency). This was replicated here, although the effect is relatively weak.

Conclusion

Research on constituency focus has tended to show that it is something that constituents (a) expect and (b) respond positively to when it does occur. These studies also indicate that constituency focus of MPs can be captured through their Parliamentary work, which MPs use to portray themselves as constituency-focused. The above formed the basis for the fundamental expectation tested in this article: that the more constituency-focused an MP’s parliamentary activity was, the more likely constituents would be to perceive their MP as constituency-focused and to trust them. This expectation was confirmed. I also test for moderating influences, based around a concern with citizens’ ability to assess representation. In line with expectations, I find that constituency focus in Parliament only affected perceived constituency focus among those who knew the name of their MP. In the following section, I discuss some important considerations, considering the limitations of this study and the opportunities for future inquiry.

First, it is well-known that political surveys – especially online surveys – over-represent the politically interested (Karp & Lühiste, Citation2016). In addition, over one-third of respondents could not place their MP on the scale of local-national focus. Taking the survey mode effect and the item non-response into account, the findings may not be externally valid to the entire population, but to a politically engaged segment of it.

We may also question whether these findings translate to other democracies, particularly because of differences in electoral system. Virtually all national parliaments have some constituency representation. However, less than half utilise UK-style plurality/majority systems with single-winner districts, with many other countries using proportional representation (PR) or a mixed system (CitationInternational Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance). In many PR systems, MPs are elected on a ‘closed list’, where voters cannot express a preference for an individual candidate. MPs may still make efforts to show a constituency focus (Poyet, Citation2014), but it is questionable whether the public hold meaningful attitudes about local representatives. For instance, name recall is lower in such systems (Holmberg, Citation2009), which was a crucial enabling factor in this study. However, the connection found here could apply in ‘open list’ systems, where constituency focus among members is very common (Bowler & Farrell, Citation1993; Carey & Shugart, Citation1995) and may reap rewards (Martin, Citation2010). Besides electoral systems, different political ‘cultures’ may place different emphasis on local focus: for instance,, the political culture of France traditionally deprecates the constituency role (Brouard, Kerrouche, Deiss-Helbig, & Costa, Citation2013, p. 179), perhaps mitigating the beneficial effect of ‘constituency focus’.

The ambiguities in constituency focus, discussed above, leave room for questioning what precisely constituents are responding to: is it the substantive or the tokenistic that is driving these effects? Chiru (Citation2018) suggests that constituents in Romania respond to substantive displays of constituency focus, such as questions about local infrastructure, but also to more superficial manifestations, such as celebrating a local event or festival. Certainly, this could be a fruitful area for further work. We might also ask to what extent media ‘spin’ may be effective. Grimmer, Messing, and Westwood (Citation2012) evaluates the effect of credit-claiming press releases for funding allocation to the incumbent’s constituency. He finds that Senators in the same states – receiving the same federal funds – who claim credit more frequently in their press releases receive higher approval than their counterparts. Future research could investigate this question by considering the insight analysis of MPs’ media presence might offer.

Indeed, the media is likely to be the crucial ‘missing link’ in the relationships found here: as acknowledged, MPs consider it a key channel for displaying their ‘focus’. However, media trends have developed in ways that may curtail the ability of MPs to send these signals, including declining audiences, media ‘deserts’ and a weaker presence for political news, especially Parliamentary reporting (Franklin, Citation1996; Howells, Citation2015; Ramsay & Moore, Citation2016). As Hayes and Lawless (Citation2018) have shown for the United States, the decline of local media has negative impacts on constituency politics, causing reductions in knowledge of local representatives and candidates, as well as decreased participation. Future work could assess how this structural phenomenon affects MPs’ incentive and ability to successfully signal local focus. This may have real significance to policy debates. In the UK, the decline of local media is on Westminster’s radar, with the recent Cairncross Review (Citation2019) making local democratic engagement a key consideration, but its focus and recommendations have been centred on coverage of local authorities rather than of MPs. Improving the evidence base in this regard might broaden the case for institutional support, but suggest a more complex policy challenge.

The findings here also have some bearing on how we evaluate the ‘cost’ of appearing to be a ‘good local MP’. Any claim that, to assure constituents of good local representation, MPs must do more of anything runs into the objection of impracticality. MPs are increasingly overworked: often working ‘60 or 70 h a week’ (Commons Committee on Standards, Citation2013). Furthermore, if MPs must do more in the House specifically, then this is evidently traded off against personally rendering casework, which conventional wisdom would suggest is crucial to a good local reputation (Thomas, Citation1992). Thus, while useful in understanding electorates, the finding from previous research that more effort improves evaluations is a poor guide to action for MPs concerned with their constituents’ opinion. This study reaches a rather different conclusion, however. It is not so much the quantity as the focus of activity that matters. This finding implies that MPs can potentially surmount the issue of time constraint and casework demands: where other paths to being perceived as a ‘good local MP’ are often onerous, exhibiting constituency focus may be an achievable route.

The costs of a ‘constituency focus’ may lie elsewhere. According to Searing (Citation1994), the constituency role is at odds with serious political ambition, including becoming a minister in government or shadow minister. This represents a ‘cost’ in that MPs do, by and large, want to achieve these offices (King & Allen, Citation2010). ‘Constituency focus’ may be costly to ambition for two main reasons. First, the constituency role may be held in lower esteem (Searing, Citation1994), although this may have changed over time (Rush & Giddings, Citation2011). Second, a focus on constituency is likely to constrain opportunities in debates or on TV to impress those making decisions over appointments (Heppell & Crines, Citation2016). Leslie (Citation2018) shows that MPs who made constituency-focused speeches were indeed less likely to be promoted to the frontbench in future. Yet some MPs may judge that it is worth the cost to make a good impression on constituents.

A final implication concerns parliamentary monitoring. Globally, Parliamentary Monitoring Organisations (PMOs) are growing in number and importance. These often create websites such as TheyWorkForYou, providing key statistics to measure and compare the performance of individual MPs (Mandelbaum, Citation2011). As Thompson (Citation2015, p. 70) notes, these privilege pure quantity: ‘attendance, the number of contributions made to debates and the number of written questions tabled’, potentially creating ‘perverse incentives’ (Speaker’s Commission on Digital Democracy, Citation2013). Edwards, de Kool, and van Ooijen (Citation2015) questioned to what extent these websites fill true ‘information needs’ among voters, identifying a key unmet need as information about MPs’ constituency advocacy. Data on public expectations of MPs would already suggest this concern, as ‘representing the views of local people in the House of Commons’ is a major public priority.

This study suggests a case that PMOs rethink their assumptions about what constitutes worthwhile ‘performance’ information. In the UK, it is talk about the constituency that makes a difference. In a possible example of ‘perverse incentives’, sheer quantity has minimal real-world impression, besides eroding perceived local focus. If what an MP talks about matters more than how much they speak, then this perhaps furthers the case advanced by critics that PMOs should provide more qualitative information. For instance, the PMO Hansard At Huddersfield uses wordclouds to display the discussions of Parliament as a whole: this could be applied to MPs as individuals in order to convey information such as their ‘focus’ without the use of dubiously precise statistics.

In the UK, constituency focus has been surging since the 1960s. Researchers have not neglected this phenomenon, but have developed a stronger account of its causes than its effects. This study begins to address this gap, but in so doing raises a number of important questions in legislative studies. Who is affected by constituency focus? Which electoral systems political cultures and media structures facilitate its effects on the public? How do MPs present their records? And what information should we make available about MPs’ ‘focus’? Although much remains uncertain, we can be confident that the public – or, at least, part of it – is paying attention: looking at the outcomes of constituency focus should therefore be a concern for the discipline.

Supplemental Material_Appendix

Download MS Word (73.1 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Edward Fieldhouse, Professor Maria Sobolewska and Dr Rosalind Shorrocks for their advice and encouragement with the manuscript. Thanks are also due to TheyWorkForYou and Hansard At Huddersfield for providing easy-to-use access to Parliamentary data. Matthew Somerville at TWFY and Fransina Stradling at Hansard At Huddersfield deserve particular credit for their help with using their tools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributor

Lawrence McKay is a PhD candidate in politics at the University of Manchester. His research concerns how people perceive the quality of representation at a local level, including contextual determinants and the activities of representatives themselves. He also works with the Westminster-based democracy charity the Hansard Society, studying public discontent and engagement with politics.

ORCID

Lawrence McKay http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2071-3943

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Hansard at Huddersfield tool calculates the relative frequency with which a word is used in the Commons (per million words). URL: https://hansard.hud.ac.uk/site/site.php (Last accessed 24/04/2019).

2 Specifically, I do not count as a ‘constituency mention’ incidences where the ‘constituen*’ string is preceded by ‘their’, ‘his’, ‘her’, ‘your’ or ‘our’.

3 It is true that Kellermann and Martin do not find such a relationship, but Kellermann provides a credible explanation for this: they use written questions for the measure of constituency focus, not debate contributions. Given the constraints on speaking in the House, they argue that MPs will be more strategic and electorally focused in how they use their time.

4 Northern Ireland (NI) excluded, as are non-NI MPs who did not serve for the entire 2010–2015 period, for instance, having won or lost their constituency in a by-election.

5 Readers may also be curious about how constituency focus differs between parties. In surveys, Labour and Lib Dem MPs claim to be more locally-focused than Conservative MPs (Rush & Giddings, Citation2011), and Kellermann finds that Labour MPs’ parliamentary questions were more locally focused, though Searing (Citation1994, p. 125) cautions that it is ‘unusual to find large partisan differences in parliamentary roles’. In this dataset, as measured at the median, Labour MPs emerge as slightly higher in focus than Conservatives and Liberal Democrat MPs. The result for Liberals is perhaps unexpected, but it is possible that in this period they were less constituency focussed and more ‘policy-seeking’ (Searing, Citation1994) because the coalition presented a rare opportunity to achieve policy aims.

6 A ‘Don’t Know’ category was also available to respondents for both dependent variables.

References

- Amsalem, E., Sheafer, T., Walgrave, S., Loewen, P. J., & Soroka, S. N. (2017). Media motivation and elite rhetoric in comparative perspective. Political Communication, 34(3), 385–403. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2016.1266065

- André, A., DePauw, S., & Andeweg, R. B. (2018). Public and politicians’ preferences on priorities in political representation. In K. Deschouwer (Ed.), Mind the gap: Political participation and representation in Belgium (pp. 51–73). London: Rowman & Littlefield Int./ECPR Press.

- André, A., Depauw, S., & Martin, S. (2015). Electoral systems and legislators’ constituency effort: The mediating effect of electoral vulnerability. Comparative Political Studies, 48(4), 464–496. doi: 10.1177/0010414014545512

- André, A., Gallagher, M., & Sandri, G. (2014). Legislators’ constituency orientation. In K. Deschouwer & S. Depauw (Eds.), Representing the people: A survey among members of statewide and substate parliaments (pp. 166–187). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arnold, R. D. (1993). Can inattentive citizens control their elected representatives? In L. C. Dodd & B. I. Oppenheimer (Eds.), Congress reconsidered (pp. 401–416). Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Bengtsson, Å, & Wass, H. (2011). The representative roles of MPs: A citizen perspective. Scandinavian Political Studies, 34(2), 143–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00267.x

- Besley, T., & Larcinese, V. (2011). Working or shirking? Expenses and attendance in the UK Parliament. Public Choice, 146(3), 291–317. doi: 10.1007/s11127-009-9591-z

- Blidook, K., & Kerby, M. (2011). Constituency influence on ‘constituency members’: The adaptability of roles to electoral realities in the Canadian case. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17(3), 327–339. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2011.595125

- Bond, J. R. (1985). Dimensions of district attention over time. American Journal of Political Science, 29, 330–347. doi: 10.2307/2111170

- Bowler, S. (2010). Private members’ bills in the UK Parliament: Is there an ‘electoral connection’? The Journal of Legislative Studies, 16(4), 476–494. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2010.519457

- Bowler, S., & Farrell, D. M. (1993). Legislator shirking and voter monitoring: Impacts of European Parliament electoral systems upon legislator-voter relationships. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 31(1), 45–70.

- Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., Kimball, D. C., Meinke, S. R., & Tate, K. (2003). The effects of political representation on the electoral advantages of house incumbents. Political Research Quarterly, 56(3), 259–270. doi: 10.1177/106591290305600302

- Branton, R. P., Cassese, E. C., & Jones, B. S. (2012). Race, ethnicity, and U.S. House incumbent evaluations. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 37(4), 465–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-9162.2012.00058.x

- Brouard, S., Kerrouche, E., Deiss-Helbig, E., & Costa, O. (2013). From theory to practice: Citizens’ attitudes about representation in France. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 19(2), 178–195. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2013.787196

- Bulut, A. T., & İlter, E. (2018). Understanding legislative speech in the Turkish Parliament: Reconsidering the electoral connection under proportional representation. Parliamentary Affairs [early view].

- Cain, B. E., Ferejohn, J. A., & Fiorina, M. P. (1979). The roots of legislator popularity in Great Britain and the United States (Social Science Working Paper, 288). California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA.

- Cairncross, F. (2019). The cairncross review: A sustainable future for journalism. Unknown place of publication: Department for Culture, Media and Sport. [ Online]. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-cairncross-review-a-sustainable-future-for-journalism

- Campbell, R., & Lovenduski, J. (2015). What should MPs do? Public and parliamentarians’ views compared. Parliamentary Affairs, 68(4), 690–708. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsu020

- Carey, J. M., & Shugart, M. S. (1995). Incentives to cultivate a personal vote: A rank ordering of electoral formulas. Electoral Studies, 14(4), 417–439. doi: 10.1016/0261-3794(94)00035-2

- Chiru, M. (2018). The electoral value of constituency-oriented parliamentary questions in Hungary and Romania. Parliamentary Affairs, 71(4), 950–969. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsx050

- Costa, M., Johnson, K., & Schaffner, B. (2018). Rethinking representation from a communal perspective. Political Behavior, 40(2), 301–320. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9393-9

- Crewe, E. (2015). The House of Commons: An anthropology of MPs at work. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Deschouwer, K., Depauw, S., & André, A. (2014). Representing the people in parliaments. In K. Deschouwer & S. Depauw (Eds.), Representing the people: A survey among members of statewide and substate parliaments (pp. 1–18). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dudzińska, A., Poyet, C., Costa, O., & Weßels, B. (2014). Representational roles. In K. Deschouwer & S. Depauw (Eds.), Representing the people: A survey among members of statewide and substate parliaments (pp. 19–38). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Edwards, A., de Kool, D., & van Ooijen, C. (2015). The information ecology of parliamentary monitoring websites: Pathways towards strengthening democracy. Information Polity, 20(4), 253–268. doi: 10.3233/IP-150372

- Fenno, R. F. (1978). Home style: House members in their districts. New York: HarperCollins.

- Fernandes, J. M., Leston-Bandeira, C., & Schwemmer, C. (2018). Election proximity and representation focus in party-constrained environments. Party Politics, 24(6), 674–685. doi: 10.1177/1354068817689955

- Fiorina, M. P., & Rivers, D. (1989). Constituency service, reputation, and the incumbency advantage. In M. P. Fiorina & D. Rohde (Eds.), Home style and Washington work (pp. 17–45). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Fox, R. (2012). Disgruntled, disillusioned and disengaged: Public attitudes to politics in Britain today. Parliamentary Affairs, 65(4), 877–887. doi: 10.1093/pa/gss053

- Franklin, B. (1996). Keeping it ‘bright, light and trite’: Changing newspaper reporting of Parliament. Parliamentary Affairs, 49(2), 298–315. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pa.a028681

- Franklin, M. N., & Norton, P. (1993). Parliamentary questions. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Frederick, B. (2008). Constituency population and representation in the U.S. House. American Politics Research, 36(3), 358–381. doi: 10.1177/1532673X07309740

- Gay, C. (2002). Spirals of trust? The effect of descriptive representation on the relationship between citizens and their government. American Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 717–732. doi: 10.2307/3088429

- Grant, J. T., & Rudolph, T. J. (2004). The job of representation in Congress: Public expectations and representative approval. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 29(3), 431–445. doi: 10.3162/036298004X201249

- Grimmer, J., Messing, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2012). How words and money cultivate a personal vote: The effect of legislator credit claiming on constituent credit allocation. American Political Science Review, 106(4), 703–719. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000457

- Hansard Society. (2010). Audit of political engagement 7. London: Hansard Society.

- Hansard Society. (2014). Tuned in or turned off? Public attitudes to Prime Minister’s questions. London: Hansard Society.

- Hayes, D., & Lawless, J. L. (2018). The decline of local news and its effects: New evidence from longitudinal data. The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 332–336. doi: 10.1086/694105

- Heitshusen, V., Young, G., & Wood, D. M. (2005). Electoral context and MP constituency focus in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. American Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 32–45. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00108.x

- Heppell, T., & Crines, A. (2016). Conservative ministers in the Coalition government of 2010–15: Evidence of bias in the ministerial selections of David Cameron? The Journal of Legislative Studies, 22(3), 385–403. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2016.1202647

- Holmberg, S. (2009). Candidate recognition in different electoral systems. In H.-D. Klingemann (Ed.), The comparative study of electoral systems (pp. 158–170). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- House of Commons Committee on Standards. (2013, October 15). Response to the IPSA consultation: MP's pay and pensions, HC 751 2013-14.

- Howells, R. (2015). Journey to the centre of a news black hole: examining the democratic deficit in a town with no newspaper (PhD Thesis). Cardiff University. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1036

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Electoral system design database. Retrieved from https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/electoral-system-design

- Judge, D. (2014). Democratic incongruities: Representative democracy in Britain. London: Palgrave.

- Judge, D., & Partos, R. (2018). MPs and their constituencies. In C. Leston-Bandeira & L. Thompson (Eds.), Exploring parliament (pp. 264–273). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Karp, J. A., & Lühiste, M. (2016). Explaining political engagement with online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(3), 666–693. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw014

- Kellermann, M. (2013). Sponsoring early day motions in the British House of Commons as a response to electoral vulnerability. Political Science Research and Methods, 1(2), 263–280. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2013.19

- Kellermann, M. (2016). Electoral vulnerability, constituency focus, and parliamentary questions in the House of Commons. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(1), 90–106. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.12075

- Kelly, R. (2015, October 23). House business committee (House of Commons Library Briefing Paper 06394).

- Killermann, K., & Proksch, S.-O. (2013). Dynamic political rhetoric: Electoral, economic, and partisan determinants of speech-making in the UK Parliament. Paper presented at 7th ECPR General Conference 2013, Bordeaux, France.

- King, A., & Allen, N. (2010). ‘Off with their heads’: British Prime Ministers and the power to dismiss. British Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 249–278. doi: 10.1017/S000712340999007X

- Lawless, J. L. (2004). Politics of presence? Congresswomen and symbolic representation. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 81–99. doi: 10.1177/106591290405700107

- Leslie, P. A. (2018). Political behaviour in the United Kingdom: An examination of members of parliament and voters (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Essex, Colchester, England.

- Loewen, P., Koop, R., Settle, J., & Fowler, J. (2014). A natural experiment in proposal power and electoral success. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 189–196. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12042

- Mandelbaum, A. G. (2011). Strengthening parliamentary accountability, citizen engagement and access to information: A global survey of parliamentary monitoring organizations. Washington, DC: National Democratic Institute and World Bank Institute.

- Martin, S. (2010). Electoral rewards for personal vote cultivation under PR-STV. West European Politics, 33(2), 369–380. doi: 10.1080/01402380903539003

- Martin, S. (2011). Using parliamentary questions to measure constituency focus: An application to the Irish case. Political Studies, 59(2), 472–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00885.x

- Middleton, A. (2019). The personal vote, electoral experience, and local connections: Explaining retirement underperformance at UK elections 1987–2010. Politics, 39(2), 137–153. doi: 10.1177/0263395718754717

- Midtbø, T., Walgrave, S., Van Aelst, P., & Christensen, D. (2014). Do the media set the agenda of parliament or is it the other way around? Agenda interactions between MPs and mass media. In K. Deschouwer & S. Depauw (Eds.), Representing the people: A survey among members of statewide and substate parliaments (pp. 188–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Navarro, J., & Francois, A. (2018, April 10–14). The missing link? Parliamentary work, citizens’ awareness and votes in French legislative elections. Nicosia: ECPR Joint Sessions University of Nicosia.

- Norris, P. (1997). The puzzle of constituency service. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 3(2), 29–49. doi: 10.1080/13572339708420508

- Parker, D. C., & Goodman, C. (2009). Making a good impression: Resource allocation, home styles, and Washington work. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 34(4), 493–524. doi: 10.3162/036298009789869709

- Poyet, C. (2014). Explaining MPs constituency orientation: A QCA approach. Paper presented at the 2014 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2452549

- Rai, S., & Spary, C. (2019). Performing representation: Women members in the Indian parliament. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Ramsay, G., & Moore, M. (2016). Monopolizing local news: Is there an emerging democratic deficit in the UK due to the decline of local newspapers? Report, CMCP, Policy Institute, King's College London.

- Rush, M., & Giddings, P. (2011). Parliamentary socialisation. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Saward, M. (2010). The representative claim. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schaffner, B. F. (2006). Local news coverage and the incumbency advantage in the U.S. House. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 31(4), 491–511. doi: 10.3162/036298006X201904

- Searing, D. (1994). Westminster's world: Understanding political roles. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Soroka, S., Penner, E., & Blidook, K. (2009). Constituency influence in parliament. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 563–591. doi: 10.1017/S0008423909990059

- Speaker’s Commission on Digital Democracy. (2013). Background to digital scrutiny. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/business/commons/the-speaker/speakers-commission-on-digital-democracy/digital-scrutiny/background-to-digital-scrutiny/

- Stein, R., & Bickers, K. (1994). Congressional elections and the Pork Barrel. The Journal of Politics, 56(2), 377–399. doi: 10.2307/2132144

- Sulkin, T., Testa, P., & Usry, K. (2015). What gets rewarded? Legislative activity and constituency approval. Political Research Quarterly, 68(4), 690–702. doi: 10.1177/1065912915608699

- Thomas, S. (1992). The effects of race and gender on constituency service. The Western Political Quarterly, 45(1), 169–180. doi: 10.2307/448769

- Thompson, L. (2015). Making British law: Committees in action. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Tinkler, J., & Mehta, N. (2016). Report to the House of Commons administration committee on the findings of the interview study with members on leaving parliament. London: Department of Information Services.

- Wagner, M. W. (2007). Beyond policy representation in the U.S. House: Partisanship, polarization, and citizens’ attitudes about casework. American Politics Research, 35(6), 771–789. doi: 10.1177/1532673X07299867

- Zittel, T. (2017). The personal vote. In K. Arzheimer, J. Evans, & M. S. Lewis–Beck, (Eds.), The sage handbook of electoral behaviour (pp. 668–687). London: Sage.

- YouGov. (2013). YouGov/IPSA survey results [Data set].