ABSTRACT

For the last two decades, the death penalty in the US has steadily declined. During this time, governors have at rare but crucial moments participated in shaping the death penalty in their respective states by issuing vetoes. Gubernatorial vetoes have in some cases been used not only to prevent abolition from occurring, but also to bar the state from enacting legislation to expand it. However, little is known about what factors influence the decision to veto these often very controversial bills. Analysis of a unique dataset of death penalty bills covering years 1999–2018 suggests that a governor’s individual attributes, as well as institutional factors, have an effect on the likelihood of a veto in the legislative context of the death penalty, with different aspects of time in office, experience and partisanship being of particular relevance.

Introduction

In May of 2019, New Hampshire Governor Chris Sununu vetoed a death penalty repeal bill for the second year in a row. This time, the veto was narrowly overridden and the only remaining retentionist state in New England removed the death penalty from its statutes, 80 years after the state’s last execution. In contrast with Governor Sununu’s actions, the decision by a majority of New Hampshire’s legislators to push for abolition followed the ongoing trend of a declining death penalty of the last two decades (Death Penalty Information Center, Citation2019a, Citation2021).

This paper aims to examine the actions of governors like Sununu when they in the context of the death penalty make use of their only formal legislative power beyond signing bills passed by the legislature, namely the veto (Kousser & Phillips, Citation2012). Previous research suggests that the act of issuing a veto can in part be explained by analysing individual factors pertaining to the governor’s characteristics and background (Barrilleaux & Berkman, Citation2003; Ferguson, Citation2014). A number of scholars have highlighted aspects such as personality types, professional background, moral stance and religious beliefs when highlighting the role of governors at crucial moments in the development of death penalty policies throughout the US (Culver & Boyens, Citation2002; Entzeroth, Citation2012; Galliher & Galliher, Citation1997; Stewart, Citation1992; Warden, Citation2012; Wozniak, Citation2012). Alternatively, and oftentimes in conjunction with the above approach, research has sought explanations to vetoes in the institutional factors such as term limits and variations in veto power (e.g. Baker & Hedge, Citation2013; Ferguson, Citation2003; Hedge, Citation1998; Herzik & Wiggins, Citation1989; Klarner & Karch, Citation2008; Wilkins & Young, Citation2002).

Yet even though governors are able to step in and shape state policy at crucial moments, they have been surprisingly neglected in the study of state policymaking (Barrilleaux & Berkman, Citation2003; Bernick, Citation2016; Ferguson, Citation2014; Kousser & Phillips, Citation2012; Thrower, Citation2019). A search for literature that puts Governor Sununu’s vetoes into context both in time and across death penalty states, therefore, comes up short. This paper aims to shed light on the vetoes issued against death penalty legislation by examining bills in all death penalty states from 1999 to 2018. The results indicate that some aspects pertaining to the governor’s background and characteristics play a role in the probability of a veto being issued, with the governor’s party affiliation being of particular importance when it comes to legislation that aims to restrict the death penalty. Gubernatorial term limits also help shape governors’ actions on death penalty legislation, making the controversial decision to issue a veto more likely as a gubernatorial term is ending. The paper thus contributes to the wider literature on how individual aspects, as well as institutional design, may affect political outcomes, but also complements the literature on individual state’s experiences on one of the few state policies that concern life and death in a literal sense (e.g. Culver & Boyens, Citation2002; Galliher & Galliher, Citation1997; Koch & Galliher, Citation1993).

Explaining gubernatorial vetoes

Previous research offers two main approaches when explaining vetoes; the individual and the institutional approach, paralleling research on presidential vetoes (e.g. Gilmour, Citation2002; Lee, Citation1975; Shields & Huang, Citation1997).

The individual approach

Among factors hypothesised as having a dampening effect on veto use is legislative experience, i.e. from Congress or the state legislature, based upon the idea that former legislators may be more understanding of how frustrating vetoes can be (Herzik & Wiggins, Citation1989; Klarner & Karch, Citation2008). Former state legislators, in particular, may also be less likely to issue vetoes as they already have a network of allies and supporters in place, reducing conflict (Ferguson, Citation2013). Legal training has also been found to have a modest negative effect as such training can provide useful negotiation skills (Sigelman & Smith, Citation1981). Relatedly, gubernatorial experience has been examined, based upon the reasoning that the longer governors serve, the more they learn in terms of expectations both on themselves and of others, and may also become more skilled at gaining the support of allies, leading to fewer vetoes (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008). The completely opposite idea has, however, also been presented, suggesting that the longer governors serve, the more they veto (Cohen & Nice, Citation1985).

Gender is another factor examined, yet one that suffers from a general lack of data (Dickes & Crouch, Citation2015). One study nevertheless hypothesises that the veto in terms of constituting a conflict between the legislative and executive branches may play out differently depending on whether the governor is a man or a woman due to either differences in policy preferences or gubernatorial personalities (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008). A broader approach on personality and gender in the context of gubernatorial leadership furthermore finds that female governors, while retaining certain differences, have learned how to ‘play the game’ and are willing to lead by exercising power over others (Barth & Ferguson, Citation2002, p. 76). However, a recent study of governors and legislative success finds no difference between male and female governors (Dickes & Crouch, Citation2015).

Another area in the context of vetoes that has not received substantial attention is party affiliation. One study argues that Democratic governors issue more vetoes due to a belief in more forceful, activist leadership by the executive (Cohen & Nice, Citation1985), yet the results have been subject to criticism (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008). Others have concluded that party may matter, yet in terms of party organisational features (e.g. Morehouse, Citation1973). In the context of the death penalty, however, a considerable body of research points to a relationship between Republican Party affiliation and support for the death penalty (e.g. Banner, Citation2003; Galliher et al., Citation2002; Steiker & Steiker, Citation2006), which would arguably translate into having an effect on the use of vetoes. Such an effect would, however, be conditioned upon the category of bill rather than aspects of gubernatorial leadership. However, research at the same time points to neither Republican support nor Democratic opposition being necessarily consistent (e.g. Koch & Galliher, Citation1993; Wozniak, Citation2012), especially when extending the time perspective historically (Amidon, Citation2018), indicating uncertainty regarding the effect of party.

The individual approach, while thus tested in a variety of ways, has provided limited evidence. In their comprehensive examination of gubernatorial vetoes, Klarner and Karch (Citation2008) find support for only one of the above factors, and very modest as such, namely that governors with prior experience as state legislators issue fewer vetoes. Herzik and Wiggins (Citation1989) likewise do not find convincing explanatory value for vetoes in factors relating to the governor’s background, nor in institutional factors, and argue that analysis should focus on state-specific politics. Ferguson (Citation2003), who applies a broader approach beyond the use of vetoes, examining overall executive leadership success in the states and an examination of multiple personal factors, likewise concludes that factors pertaining to the governor personally, including prior legislative experience and tenure, are of mixed importance to leadership success.

Despite the very mixed results in applications of the individual approach, literature that provides narratives of central courses of events in death penalty states provide grounds for incorporating these factors when examining vetoes. Examples include research highlighting Florida Governor Reubin Askew’s pivotal role in the state’s reinstatement in 1972 and the governor’s actions in relation to his professional background as a lawyer and prosecutor (Stewart, Citation1992), as well as South Carolina Governor and former lawyer and army veteran John C. West’s unsuccessful veto against a reinstatement bill in 1974 (Koch et al., Citation2012). There is also Kansas Governor Joan Finney’s decision not to veto a law reinstating capital punishment in 1994 despite her opposition to it (Galliher & Galliher, Citation1997), Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley’s religious arguments in the legislative debates regarding an abolition bill in 2009 (Wozniak, Citation2012), Illinois Governor Pat Quinn’s religious convictions when signing the bill to abolish the death penalty in 2011 (Warden, Citation2012), and Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber’s personal reasons for declaring a moratorium on executions that same year (Entzeroth, Citation2012). Two recent examples provide explicit insight into how governors publically refer to themselves at these types of pivotal events. In 2019, when California Governor Gavin Newsome signed an executive order that placed a moratorium on executions, he stated ‘I cannot in good conscious sign a death warrant for someone. This is coming on me … I just can’t do it’ (Allen et al., Citation2019). Two years prior, Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson had made his mark on the administration of the death penalty in his state in a diametrically opposite way by signing multiple death warrants at the same time. When asked about how he squared his religious beliefs with his support of capital punishment, he stated

From my standpoint, I have two convictions: One, I think the death penalty is appropriate punishment for the most serious and heinous crimes in our society. Secondly, I have a duty as governor to faithfully execute the laws of our state. (Millar, Citation2017)

What these examples, moreover, show is the range of involvement by the governor when it comes to the death penalty, from what is primarily in focus in this paper, i.e. vetoes, to moratoriums, to the explicit role of the governor when it comes to either signing a death warrant, or in rare instances granting clemency and putting a halt to an execution altogether (Sarat, Citation2008). Furthermore, none of these actions are taken in a vacuum. In fact, when examining factors that can explain the slow but steady decline in public support for the death penalty over the last two decades as mentioned in the introduction, dramatic events such as those involving significant decisions by governors have been shown to constitute one factor that can affect public opinion (Baumgartner et al., Citation2008). While public opinion on the death penalty is complex and can be considered both a cause and a consequence of death penalty policies (Shirley & Gelman, Citation2015), detaching background aspects from an examination of gubernatorial vetoes of such policies limits possible influences when stakes are high and governors may face public scrutiny over their actions.

The institutional approach

Gubernatorial vetoes can also be explained by factors that lie beyond the control of the individual governor. An important foundation and major theme of the study of institutional factors and gubernatorial leadership is the development of indices of formal powers and identifying how such powers are employed by governors (e.g. Beyle, Citation1968, Citation1990; Ferguson, Citation2013; Kousser & Phillips, Citation2012; Schlesinger, Citation1965). The original index by Schlesinger (Citation1965) covered tenure potential, appointment power, budget-making power and the veto, whereas additional dimensions such as how executive branch officials are elected and party control in the legislature have been added since (e.g. Beyle, Citation1990; Ferguson, Citation2013). Research has been able to conclude that gubernatorial formal powers have strengthened over time, in all states (Ferguson, Citation2014).

Scholars have examined how these formal powers relate to gubernatorial leadership; research that has most commonly focused upon the governor’s actions in the budget-making process, as well as the use of the veto (Ferguson, Citation2014). Overall, the literature points to governors with greater formal powers using the veto more often. For example, when the bar to counter a governor’s veto is higher, i.e. when the number of legislators required to override a veto increases, governors issue more vetoes (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008). Scholars have also found that governors use their veto power more frequently under a divided government as a consequence of proposed legislation not reflecting the politics of the governor’s party (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008; Wiggins, Citation1980). In veto override situations, governors have indeed been found to be more likely to be able to influence a legislator belonging to the same party than a member from the opposition party, even under circumstances when two legislators do not disagree markedly regarding a policy (Wilkins & Young, Citation2002). Conflict between the branches, and subsequently more vetoes, may also occur when governors face a term limit. In particular, so-called lame-duck governors reaching the end of their terms may have run out of some of their previously held political leverage, affecting cooperation with the legislature and potentially increasing inter-branch conflict (Baker & Hedge, Citation2013; Klarner & Karch, Citation2008; Lewis et al., Citation2015).

An approach that takes into account institutional features of legislatures may result in alternative analyses uncovering additional veto dynamics. Clues to gubernatorial power being situated outside of the executive branch have been demonstrated by Kousser and Phillips (Citation2012), who find strong evidence that increasing legislative professionalism causes executive power to decline. Professionalised legislatures may be more likely to experience gubernatorial vetoes as the legislation they produce is more complex (Squire & Moncrief, Citation2015), and are more inclined to ‘assert their institutional will’ (Baker & Hedge, Citation2013, p. 247). Ferguson (Citation2003) in contrast finds that more professionalised legislatures enhance governors’ legislative success and effectiveness (see also Dilger et al., Citation1995). Research has also found that there is a tendency for fewer veto overrides in professional legislatures as legislators make strategic calculations of the actual political costs of opposing vetoes (Baker & Hedge, Citation2013).

Expectations

The first expectation is that gubernatorial veto decisions are in part determined by individual aspects, with previous research pointing to how prior positions in Congress or the state legislature, legal training, or experience from the gubernatorial office itself in terms of years, reduce the propensity for executive-legislative conflict in the form of vetoes as governors with such experience avoid conflicts and are also more skilled in building coalitions (e.g. Cohen & Nice, Citation1985; Herzik & Wiggins, Citation1989; Klarner & Karch, Citation2008; Sigelman & Smith, Citation1981).

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Experience from prior membership in Congress, the state legislature and from legal training, as well as in experience in terms of years in gubernatorial office is negatively associated with vetoes.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Female governors are positively associated with vetoes.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Democratic governors are positively associated with vetoes, but this effect is conditioned by bill category.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Strong veto powers and gubernatorial term limits are positively associated with vetoes.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): More professionalised legislatures are negatively associated with vetoes.

Research design and data

This study examines the use of gubernatorial vetoes in the 38 states which retained the death penalty in 1999, to the end of 2018 when 30 states remained;Footnote1 meaning the study covers a substantial part of a time period marked by a declining death penalty that begun in the late 1990s (Baumgartner et al., Citation2018). The bills were collected from each state’s official state legislature website, comprising all death penalty-related bills that were either enacted or vetoed during the selected time period, including those which were unsuccessfully vetoed. The dependent variable is a dichotomous variable, where 1 indicates that the bill was vetoed, 0 that it was not. In order to avoid inflating the number of vetoes, instances, when the essentially same bill is vetoed multiple times in the same year is per previous research (Herzik & Wiggins, Citation1989) counted as one single veto.Footnote2

Primary independent variables

Starting with individual characteristics, a number of straightforward indicators are added. The governor’s professional experience is examined by including dummy variables indicating whether the governor had been a member of Congress, a state legislator or had a law degree obtained prior to becoming governor. Adding to the emphasis of experience, I also include a variable indicating the number of years in office at the time the decision was made on each individual bill (i.e. vetoed or signed). For example, if a governor vetoed a bill during his or her first year in office, a 0 is recorded, while a governor vetoing a bill in his or her third year is recorded as a 2. The individual aspects gender and party affiliationFootnote3 are also added as dichotomous variables.

When it comes to institutional factors, a measurement of gubernatorial veto power is first of all included. Veto power is one of six elements included in the gubernatorial formal power index originally developed by Schlesinger (Citation1965) and updated and/or modified by others since (e.g. Beyle, Citation1999; Ferguson, Citation2013; Kousser & Phillips, Citation2012). As useful as an index covering multiple decades can be, I agree with scholars who argue that the composite index of institutional powers is better served broken up or modified to suit different contexts (e.g. Daley et al., Citation2007; Dometrius, Citation1979, Citation2002). Additionally, the index may not be comparable over time for all dimensions due to varying coding principles (Krupnikov & Shipan, Citation2012). The veto power element is thus broken out forming its own scale based upon the coding conducted by Ferguson (Citation2013), with missing years complemented by data from Council of State Governments (Citationvarious years). It is measured from 1 to 5, where the strongest veto power 5 means that the governor has item veto, and in order to override the veto, a special majority is needed (three-fifths of elected lawmakers or two-thirds of them present), and 1 means that the governor has a regular veto, and only a simple majority is needed to override (Ferguson, Citation2013). I also include a dummy variable for gubernatorial term limits, another element included in the formal power index. Lastly, I use Squire’s widely applied legislative professionalism index for the year 2009 (Squire & Moncrief, Citation2015).

Control variables

I add a variable controlling for the number of annual executions. This most explicit outcome of having a death penalty statute varies greatly between the states, to the point where they can be classified as ‘symbolic’ and ‘executing’ considering the great contrast between states where executions rarely occur and those where they are more common (Steiker & Steiker, Citation2006). A relatively high number of executions in a state could for example send a signal to a governor regarding the possible political cost of opposing legislation that aims to support the continued use of the death penalty, as opposed to a state where executions are rare. I also control for two aspects pertaining to the individual bill. The first dummy variable controls for bill type, meaning either restrictive, i.e. legislation with the ultimate aim of limiting the number of death sentences and executions, even ending them altogether, or supportive, meaning legislation that aims to facilitate if not more, but at least the continued existence of such (see Appendix 1 for details on bill categorisation). The second bill-level control variable tracks if the bill was introduced by a committee as multiple co-sponsorship has been found to predict bill success in state legislatures (Browne, Citation1985). I control for whether the governor is in opposition with a unified legislature, i.e. a simple divided government is in place thus theoretically increasing conflict between the governor and the legislators (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008; Wiggins, Citation1980). Lastly, I also control for the very last year a governor’s term under term limits, i.e. the ‘lame-duck’ year, building upon the reasoning that governors have less to lose during that time period of their tenure.Footnote4

Modelling strategy

The study of gubernatorial vetoes within a specific policy area comes with substantial statistical difficulty, as vetoes are very rare events (Herzik & Wiggins, Citation1989; Wiggins, Citation1980). I test my hypotheses by estimating logistic regression models, but also present an alternative estimation method specifically designed to address issues of rare events data (see Appendix 3). I address potential issues of within-sample dependence by clustering standard errors by state, and temporal dependence with fixed effects for year.Footnote5

Results

Before presenting the statistical regression analyses, an overview of the vetoes and enacted bills examined in this study is presented in . One general pattern the table displays is that restrictive bills were proportionally more commonly vetoed than supportive bills (7.8 versus 5.2 per cent); a pattern which also includes a wider geographical spread of vetoes (11 states compared to 3). Only three governors issued vetoes against supportive bills, where Virginia Governor Tim Kaine, Democrat and long-time opponent to capital punishment (Stolberg & Kaplan, Citation2016), stands out above the rest. Overall activity in terms of both vetoes and enacted bills has, however, declined over time as the number of death penalty states have shrunk.

Table 1. Vetoed and enacted bills by year and category.

Moving on to the logistic regression models, the results presented in confirm some expectations and contradicts others. Regarding individual characteristics, the expectation in H1 was that four different types of professional experience inside and outside the governor’s mansion would be associated with a lower probability for a death penalty bill being vetoed. According to Model 1, experience from Congress is not a statistically significant variable, as opposed to experience from the state legislature and holding a law degree, yet these are positively associated with vetoes. Years in office is as hypothesised negatively associated with vetoes, meaning that newly elected governors are more likely to issue vetoes. The hypothesis regarding different types of professional experience having a dampening effect on vetoes is thus not confirmed.Footnote6

Table 2. Determinants of gubernatorial vetoes, 1999–2018.

Regarding H2 and the gender of governors, the results show support for the expectation that women are more likely to issue vetoes as the indicator reaches a modest level of significance. The result should nevertheless be interpreted with caution considering the limitations of the small dataset.Footnote7

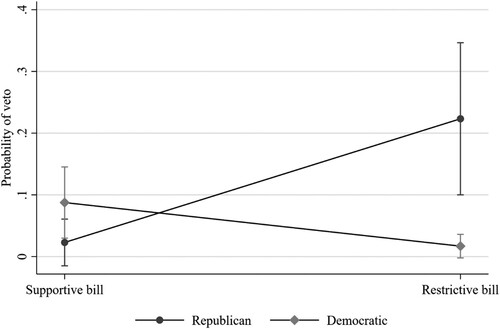

Regarding the third hypothesis (H3), Democratic governors are according to Model 1 contrary to previous research (Cohen & Nice, Citation1985) less likely to issue vetoes. The expectation formulated in H3 was, however, that bill type would be of importance due to the general partisan divide on the death penalty, meaning an interaction effect needs to be examined in a separate model. According to Model 2 in , the interaction is indeed significant, but the interpretation is facilitated by plotting the average marginal effects (with 95 per cent confidence intervals). confirms a noticeable difference between governors of the two parties and vetoes against anti-death penalty legislation as hypothesised, while also noting that the confidence intervals are large for Republican governors. It also shows that the differences when it comes to supportive bills exist but are less clear.

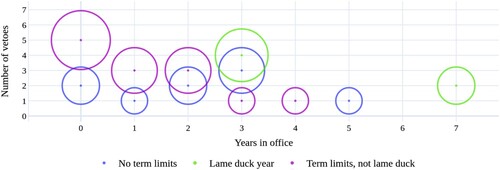

Findings regarding institutional factors are also mixed. Both veto powers and term limits are statistically significant, but contrary to expectations formulated in H4 negatively associated with the probability of a veto. A higher bar to overriding a veto may simply not be an important aspect when the decision to veto is made regarding this type of legislation, and simply having term limits does not increase conflict in the shape of vetoes. However, when it comes to governors who do have to abide by a term limit, the results show that such governors are still more likely to issue a veto, only at a specific point in time. The indicator controlling for ‘lame-duck’ governors is positively associated with vetoes, meaning that this increased propensity for conflict, in line with previous research (Klarner & Karch, Citation2008) and in the context of the death penalty, can be an effect of the issue being potentially very controversial. In relation to the indicator regarding gubernatorial experience in office, this aspect can be illustrated by plotting all vetoes in a simple chart. According to , there is indeed a pattern of vetoes being issued during lame-duck years, i.e. during years 3 and 7. When not in their lame-duck year, governors under term limits more commonly issue vetoes during earlier years of their tenure per the results discussed earlier, and governors under no term limits act similarly.

Figure 2. Vetoes by gubernatorial term limit type and gubernatorial years in office.

Note: The year 0 reflects that the veto was issued during the governor’s first year in office.

Turning to the last hypothesis regarding legislative professionalism, the results indicate that there is support for H5 as higher levels of professionalism are negatively associated with vetoes. Looking at New Hampshire, the least professionalised legislature (Squire & Moncrief, Citation2015), it is indeed where vetoes against three separate repeal bills were issued during the period of study. Rather than seeing vetoes as some kind of failure on the governor’s part (e.g. Beyle, Citation1990), unable to prevent certain legislation to pass legislative chambers via bargaining and negotiations, it is possible that vetoes in this context exemplify demonstrations of executive strength against a less professionalised body of lawmakers. This finding is further demonstrated in which summarises the predicted probabilities of the key variables in Model 1, showing the negligent probability of a veto in states with higher levels of legislative professionalism.

Table 3. Predicted probabilities associated with vetoes.

Finally, when it comes to remaining control variables, the number of executions is first of all negatively associated with the probability of a veto, meaning governors are less likely to engage in death penalty legislation via vetoes if the state actively implements the policy.Footnote8 By a similar logic, if a bill is introduced by a committee and signals support already at an early stage of the legislative process, the results show that this has an even stronger negative effect on the likelihood of a veto. Governors whose party opposes that of the legislature, however, has a strong positive effect, an expected result based upon the idea of a veto illustrating tension between the two, used as a way for governors to strengthen their position (Herzik & Wiggins, Citation1989; Sharkansky, Citation1968).Footnote9

Discussion

By issuing vetoes, governors have affected the trajectory of death penalty policies in their respective states during the last two decades. Sometimes, this has occurred at pivotal moments. In this study, I draw upon a unique dataset of death penalty bills that have reached the governor’s desk to examine what factors can influence this very rare decision. The results suggest both individual and institutional factors play a role, but point especially to aspects of partisanship and time.

Regarding the party affiliation of a governor facing death penalty legislation, the result that indicates that Democratic governors are less likely to veto bills that aim to restrict the death penalty compared to their Republican counterparts is in line with previous research (e.g. Banner, Citation2003; Steiker & Steiker, Citation2006). On the other hand, the difference was not as clear when it came to bills that aim to support the continued use of the death penalty. Further problematising the idea of a distinct party difference is that among the many enacted bills supporting the continued use of the death penalty included in above, the vast majority were not vetoed by Democratic governors such as Governors Jerry Brown of California, Ted Kulongoski of Oregon, and Terry McAuliffe of Virginia, despite their expressed anti-death penalty sentiments (Connor & Helsel, Citation2017; Pitkin, Citation2008; Shafer & Lagos, Citation2019). This inconsistency in terms of partisanship and the death penalty, as argued in previous research (e.g. Koch & Galliher, Citation1993; Wozniak, Citation2012), thus applies in this study as well. It is possible that this inconsistency relates to the discussion presented by Steiker and Steiker (Citation2006), as well as Garland (Citation2010), regarding Democratic-dominated states where executions are rare yet the death penalty as a statute remains intact year after year, illustrating a political situation where attitudes towards the death penalty vary among government branches, causing some friction yet in the end still reaches a state of equilibrium. Such states stand in contrast with those where there is a general political consensus regarding the administration of the death penalty, and where less conflict in the shape of gubernatorial vetoes would be expected.

The results also show evidence of inconsistency when considering gubernatorial term limits. Based upon , a strategic window for bill passage could exist somewhere in the middle of a governor’s term under the most optimal institutional circumstances. Petitioning a lame-duck governor to via a veto block certain oftentimes very controversial death penalty legislation may also pay off. Overall, what the results show is that the tendency to veto death penalty legislation should not be seen as static but perhaps instead dynamic under certain circumstances. This is applicable when analysing gubernatorial vetoes looking forward, as both governors and lawmakers in the shrinking number of states where the death penalty is retained will likely face a number of issues growing in complexity and potential level of contention among voters. These issues include but are not limited to claims of racial bias in sentencing, lengthy and costly appeals processes, mental illness among the condemned, the availability and efficacy of lethal injection drugs, and an elderly death row. Additionally, the aspect of innocence and wrongful convictions has become an increasingly important factor when it comes to public opinion on the death penalty (Baumgartner et al., Citation2008); an aspect future studies on gubernatorial actions in the context of the death penalty should examine.

While the findings discussed above offer some indications on the importance of not neglecting the effect of party, experience and certain institutional circumstances in the context of executive-legislative relations and gubernatorial leadership, as has been pointed out in the literature and above, there are important methodological concerns that follow from the existence of very limited data. Some of these concerns have been addressed by including additional modelling while others remain, such as that in the current dataset, there are only 12 female governors, compared to 92 men, representing roughly the same proportions of the total amount of bills (10.8 per cent involving female governors versus 89.2 per cent involving male). This general lack of data regarding gender and governors is nothing unusual (Dickes & Crouch, Citation2015) whereby an extended study including additional years could strengthen the results, possibly also catching relevant patterns of veto use under very different circumstances, such as the time period preceding the turning point towards a declining death penalty at the end of the 1990s.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emma Ricknell

Emma Ricknell is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Linnaeus University in Växjö, Sweden.

Notes

1 At the time of writing, there are 27 death penalty states (Death Penalty Information Center, Citation2021).

2 This pertains to two instances. First, Governor Ronnie Musgrove’s vetoes against HB1603 and HB1604 in 2001, two almost identical bills that if successfully vetoed would have reduced the ability for indigent defendants facing capital charges to obtain defense attorneys, count as one veto. Second, during the years 2007, 2008 and 2009, Governor Tim Kaine issued 12 vetoes, but some for identical bills and in the same year. In 2007, five bills were vetoed, but in reality they account for only two as identical bills are proposed multiple times. In 2008, the same bill was successfully vetoed twice, but counts as one veto. In 2009, two identical bills were both successfully vetoed and count as one veto. The remaining three were vetoes against similar, but not identical bills.

3 Nebraska’s unique, unicameral, non-partisan legislature typically excludes it from analyses on partisanship. However, lawmakers in Nebraska are affiliated with one of the two major parties. The Nebraska Blue Books, provided by the legislature itself (Clerk of the Legislature, Citationvarious years), indeed list party affiliation of each senator. This information has therefore been collected by the author and treated as affiliation equal to that of lawmakers in other states.

4 See Appendix 2 for measurements of all independent variables, and Appendix 4 for descriptive statistics.

5 To ensure that the predictors do not suffer from multicollinearity, I also examine the variance inflation factor (VIF). The mean VIF of 2.32 indicates that multicollinearity is not a considerable issue (Menard, Citation1995).

6 Research applying the individual approach (e.g. Ferguson, Citation2003; Klarner & Karch, Citation2008) suggests the inclusion of an assessment of the effect of electoral mandate on vetoes. The variable, measured as the percentage of votes the governor received in each election, did however not reach statistical significance, nor did it improve the model fit, and was therefore not included in the present study. Earlier models also included a control variable for state homicide rate, but its inclusion did not improve the model fit nor did it significantly alter the performance of other variables, whereby it was omitted.

7 A test of the possibility of gender interacting with bill type was examined, yet no statistically significant interaction term was found.

8 The existence of an interaction effect between the number of executions and bill type was examined, considering the possibility that governors in states where executions are more frequent could be more likely to veto restrictive bills, as well as less likely to veto supportive ones. No statistically significant interaction term was however found.

9 Research applying the individual approach (e.g. Ferguson, Citation2003; Klarner & Karch, Citation2008) suggests the inclusion of an assessment of the effect of electoral mandate on vetoes. The variable, measured as the percentage of votes the governor received in each election, did however not reach statistical significance, nor did it improve the model fit, and was therefore not included in the present study. Earlier models also included a control variable for state homicide rate, but its inclusion did not improve the model fit nor did it significantly alter the performance of other variables, whereby it was omitted.

References

- Allen, K., Parks, M. A., & Parkinson, J. (2019, March 14). California Gov. Gavin Newsom announces moratorium on death penalty, calls decision ‘personal’. ABC News. Retrieved March 15, 2019, from https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/california-gov-gavin-newsom-announces-moratorium-death-penalty/story?id=61647302

- Amidon, E. (2018). Politics and the death penalty: 1930–2010. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(4), 831–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-018-9441-y

- Baker, T., & Hedge, D. M. (2013). Term limits and legislative-executive conflict in the American states. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 38(2), 237–258. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42703800. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12012

- Banner, S. (2003). The death penalty: An American history. Harvard University Press.

- Barrilleaux, C., & Berkman, M. (2003). Do governors matter? Budgeting rules and the politics of state policymaking. Political Research Quarterly, 56(4), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/3219802

- Barth, J., & Ferguson, M. R. (2002). Gender and gubernatorial personality. Women & Politics, 24(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1300/J014v24n01_04

- Baumgartner, F., Davidson, M., Johnson, K., Krishnamurthy, A., & Wilson, C. (2018). Deadly justice: A statistical portrait of the death penalty. Oxford University Press.

- Baumgartner, F. R., De Boef, S. L., & Boydstun, A. (2008). The decline of the death penalty and the discovery of innocence. Columbia University Press.

- Bernick, E. L. (2016). Studying governors over five decades: What we know and where we need to go? State and Local Government Review, 48(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X16651477

- Beyle, T. L. (1968). The governor’s formal powers: A view from the governor’s chair. Public Administration Review, 28(6), 540–545. https://doi.org/10.2307/973331

- Beyle, T. L. (1990). The powers of the governor in North Carolina: Where the weak grow strong – Except for the governor. North Carolina Insight, 12(2), 27–45.

- Beyle, T. L. (1999). The governors. In V. Gray, R. Hanson, & H. Jacob (Eds.), Politics in the American states: A comparative analysis (pp. 191–231). CQ Press.

- Browne, W. P. (1985). Multiple sponsorship and bill success in US state legislatures. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 10(4), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.2307/440070

- Clerk of the Legislature. (Various years). The Nebraska blue book. Nebraska Legislative Reference Bureau. http://govdocs.nebraska.gov/epubs/L3000/D001.html

- Cohen, J. E., & Nice, D. G. (1985, August 29–September1). A decision theoretic model of gubernatorial vetoes [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Connor, T., & Helsel, P. (2017, July 6). Virginia executes William Morva for 2006 killings. NBC News. Retrieved 2 November, 2019, from: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/virginia-gov-terry-mcauliffe-won-t-stop-william-morva-execution-n780236

- Council of State Governments. (Various years). The book of the states. Council of State Governments. http://knowledgecenter.csg.org/kc/category/content-type/content-type/book-states

- Culver, J. H., & Boyens, C. (2002). Political cycles of life and death: Capital punishment as public policy in California. Albany Law Review, 65(4), 991–1015.

- Daley, M. D., Haider-Markel, D. P., & Whitford, A. B. (2007). Checks, balances, and the cost of regulation: Evidence from the American states. Political Research Quarterly, 60(4), 696–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907307517

- Death Penalty Information Center. (2019a). The death penalty in 2019: Year-end report. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/dpic-reports/dpic-year-end-reports/the-death-penalty-in-2019-year-end-report

- Death Penalty Information Center. (2019b). Execution database. Retrieved January 5, 2019, from: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/executions/execution-database

- Death Penalty Information Center. (2021, March 24). Statement by Robert Dunham. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from https://documents.deathpenaltyinfo.org/pdf/DPICVirginiaAbolitionStatement.pdf

- Dickes, L. A., & Crouch, E. (2015). Policy effectiveness of US governors: The role of gender and changing institutional powers. Women’s Studies International Forum, 53, 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2015.06.018

- Dilger, R. J., Krause, G. A., & Moffett, R. R. (1995). State legislative professionalism and gubernatorial effectiveness, 1978–1991. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 20(4), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.2307/440193

- Dometrius, N. C. (1979). Measuring gubernatorial power. The Journal of Politics, 41(2), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/2129780

- Dometrius, N. C. (2002). Gubernatorial approval and administrative influence. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 2(3), 251–267.

- Entzeroth, L. (2012). The end of the beginning: The politics of death and the American death penalty regime in the twenty-first century. Oregon Law Review, 90(3), 797–835. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/12127

- Ferguson, M. R. (2003). Chief executive success in the legislative arena. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 3(2), 158–182. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40421486. https://doi.org/10.1177/153244000300300203

- Ferguson, M. R. (2013). Governors and the executive branch. In V. Gray, R. L. Hanson, & T. Kousser (Eds.), Politics in the American states: A comparative analysis (pp. 208–249). CQ Press.

- Ferguson, M. R. (2014). State executives. In D. P. Haider-Markel (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of state and local government (pp. 319–342). Oxford University Press.

- Galliher, J. F., Koch, L. W., Keys, D. P., & Guess, T. J. (2002). America without the death penalty: States leading the way. Northeastern University Press.

- Galliher, J. M., & Galliher, J. F. (1997). ‘Déjà vu all over again’: The recurring life and death of capital punishment legislation in Kansas. Social Problems, 44(3), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.2307/3097183

- Garland, D. (2010). Peculiar institution: America’s death penalty in an age of abolition. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Gilmour, J. B. (2002). Institutional and individual influences on the president’s veto. The Journal of Politics, 64(1), 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00124

- Hedge, D. M. (1998). Governance and the changing American states. Westview Press.

- Herzik, E. B., & Wiggins, C. W. (1989). Governors vs. legislatures: Vetoes, overrides, and policy making in the American states. Policy Studies Journal, 17(4), 841–862. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1989.tb00822.x

- King, G., & Zeng, L. (2001). Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Analysis, 9(2), 137–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a004868

- Klarner, C. E. (2013a). Governors dataset. Harvard Dataverse, V1. Retrieved October 18, 2018, from: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PQ0Y1N

- Klarner, C. E. (2013b). State partisan balance data, 1937–2011. Harvard Dataverse, V1. Retrieved October 18, 2018 from: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LZHMG3

- Klarner, C. E., & Karch, A. (2008). Why do governors issue vetoes? The impact of individual and institutional influences. Political Research Quarterly, 61(4), 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908314200

- Koch, L. W., & Galliher, J. F. (1993). Michigan’s continuing abolition of the death penalty and the conceptual components of symbolic legislation. Social and Legal Studies, 2(3), 323–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/096466399300200304

- Koch, L. W., Wark, C., & Galliher, J. F. (2012). The death of the American death penalty: States still leading the way. Northeastern University Press.

- Kousser, T., & Phillips, J. H. (2012). The power of American governors: Winning on budgets and losing on policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Krupnikov, Y., & Shipan, C. (2012). Measuring gubernatorial budgetary power: A new approach. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 12(4), 438–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440012453591

- Lee, J. R. (1975). Presidential vetoes from Washington to Nixon. The Journal of Politics, 37(2), 522–546. https://doi.org/10.2307/2129005

- Lewis, D. C., Schneider, S. K., & Jacoby, W. G. (2015). Institutional characteristics and state policy priorities: The impact of legislatures and governors. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 15(4), 447–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440015586315

- Menard, S. W. (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis. Sage university series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage Publications.

- Millar, L. (2017, April 13). Governor Hutchinson meets the press to talk capital punishment [Blog post]. Retrieved August 3, 2019, from https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2017/04/13/governor-hutchinson-meets-the-press-to-talk-capital-punishment

- Morehouse, S. M. (1973). The state political party and the policy-making process. American Political Science Review, 67(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/1958527

- Pitkin, J. (2008, January 22). Killing time. Willamette Week. Retrieved November 3, 2019, from https://www.wweek.com/portland/article-8334-killing-time.html

- Sarat, A. (2008). Memoralizing miscarriages of justice: Clemency petitions in the killing state. Law & Society Review, 42(1), 183–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2008.00338.x

- Schlesinger, J. A. (1965). The politics of the executive. In H. Jacob, & K. N. Vines (Eds.), Politics in the American states (pp. 207–238). Little, Brown and Company.

- Shafer, S., & Lagos, M. (2019, March 12). Gov. Gavin Newsom suspends death penalty in California. KQED. Retrieved March 15, 2019, from: https://www.npr.org/2019/03/12/702873258/gov-gavin-newsom-suspends-death-penalty-in-california

- Sharkansky, I. (1968). Agency requests, gubernatorial support and budget success in state legislatures. American Political Science Review, 62(4), 1220–1231. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953914

- Shields, T., & Huang, C. (1997). Executive vetoes: Testing presidency-versus president-centered perspectives of presidential behavior. American Politics Quarterly, 25(4), 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X9702500402

- Shirley, K. E., & Gelman, A. (2015). Hierarchical models for estimating state and demographic trends in US death penalty public opinion. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 178(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12052

- Sigelman, L., & Smith, R. (1981). Personal, office and state characteristics as predictors of gubernatorial performance. Journal of Politics, 43(1), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130245

- Squire, P., & Moncrief, G. (2015). State legislatures today: Politics under the domes (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Steiker, C. S., & Steiker, J. M. (2006). A tale of two nations: Implementation of the death penalty in ‘executing’ versus ‘symbolic’ states in the United States. Texas Law Review, 84(7), 1869–1929.

- Stewart, M. (1992). Enactment of the Florida death penalty statute, 1972: History and analysis. Nova Law Review, 16(3), 1299–1355. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr/vol16/iss3/10

- Stolberg, S. G., & Kaplan, T. (2016, July 23). On death penalty cases, Tim Kaine revealed inner conflict. New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2019, from: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/24/us/politics/tim-kaine-death-penalty.html

- Thrower, S. (2019). The study of executive policy making in the US states. Journal of Politics, 81(1), 364–370. https://doi.org/10.1086/700727

- Warden, R. (2012). How and why Illinois abolished the death penalty. Law & Inequality, 30(2), 245–286. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol30/iss2/2

- Wiggins, C. W. (1980). Executive vetoes and legislative overrides in the American states. Journal of Politics, 42(4), 1110–1117. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130738

- Wilkins, V. M., & Young, G. (2002). The influence of governors on veto override attempts: A test of pivotal politics. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 27(4), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3598659

- Wozniak, K. H. (2012). Legislative abolition of the death penalty: A qualitative analysis. In A. Sarat (Ed.), Studies in law, politics, and society, 57 (pp. 31–70). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1059-4337(2012)0000057005

Appendices

Appendix 1. Coding of bill categories

In order to construct the two main categories of bills – restrictive and supportive – all bills were coded based upon the below subcategories, building upon categories applied in Baumgartner et al. (Citation2018). A fundamental basis for the categorisation is that the main purpose of a bill can either favour or disfavour capital defendants, both from a short- and long-term perspective. Bills which aim to, for example, reform the criminal justice system in a more broad manner and do not state explicit consequences for capital defendants are not included in the dataset. Also, some enacted bills are heavily amended during the legislative process, for example, introduced as a repeal bill but the bill presented to the governor is one creating a commission to study the death penalty. Such bills are coded based upon what the governor either signed or vetoed. Resolutions are not included in the dataset.

Table A1. Specification of bill categories.

Appendix 2. Measurements and sources of data

Table A2. Measurements and original sources of all independent variables.

Appendix 3. Alternative model specification: ReLogit

Considering the methodological concerns or studying a rare event such as the veto, an alternative estimation method aimed at reducing the bias common with rare event data is employed. The alternative model applies a bias correction method, meaning it estimates the same logit model yet applies an estimator that provides a lower mean square error for coefficients and probabilities. This rare-events logistic regression is available as the user-written Stata module ReLogit (King & Zeng, Citation2001). By default, ReLogit calculates robust variance estimates, and I also cluster by state.

A number of limitations apply when estimating this alternative model. First, ReLogit does not report Pseudo-R2. As a consequence of a reduction in bias, reduction in model fit is, however, to be expected and not a main concern to begin with. Second, it does not allow for interaction effects. Third, the variable controlling for year cannot be included in the model as a fixed variable, meaning the loss of data the original logistic regression displays due to the lack of variation in the dependent variable (i.e. no vetoes) is not applicable.

With these aspects in mind, the rare-events logistic regression model presented below provides more conservative results, yet not substantially different estimated coefficients at least in terms of overall pattern and coefficient signs. The coefficient for the variable tracking governor background characteristic regarding experience as state legislator, as well as that of the variable controlling for the bill having been introduced by a committee are not statistically significant in the rare-events logistic regression.

Table A3. Determinants of gubernatorial vetoes, 1999–2018 (ReLogit).

Appendix 4. Descriptive statistics

Table A4. Descriptive statistics for all variables.