ABSTRACT

This article argues that the European Central Bank’s legitimacy mainly rests upon ‘throughput legitimacy’ in practice and, in particular, upon perceptions of accountability among the ECB’s main political audiences, including the members of the European Parliament. This thin and contingent ‘legitimacy-as-accountability’ gives rise to a tension post-crisis: on the one hand, the ECB’s enlarged monetary policy role requires ever-wider scrutiny and parliamentary debate; on the other hand, the quality of accountability hinges on the specialisation of those involved. To address the paradoxical challenge of both wider and more in-depth oversight, the article discusses a number of recent policy proposals. Empirically, it draws on survey and interview data covering the decade 2009–2019, i.e. the ‘crisis parliament’ of 2009–2014 and the ‘post-crisis parliament’ of 2014-2019. It concludes with a reflection on the promises and pitfalls of the ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability towards the European Parliament(s) during the COVID-19 crisis.

Introduction.Footnote1, Footnote2

After more than a decade of crises, the European Central Bank (ECB)’s role within Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) has expanded in myriad ways, whereas its formal mandate has remained broadly unchanged. As a result, pertinent questions have emerged as to whether the supranational central bank is sufficiently democratically legitimised given its ever-growing set of responsibilities (Schmidt, Citation2020). At least five areas can be identified in which the ECB’s powers have increased over time (Fromage et al., Citation2019; Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a). First, the ECB has become responsible for monitoring and safeguarding not only price stability but also financial stability in the euro area, including through its chairing of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). Second, it has gained responsibilities within the Troika of institutions that have administered macroeconomic adjustment programmes in crisis-hit member states (Dermine, Citation2019; European Parliament, Citation2015). Third, it has obtained supervisory powers through the Banking Union’s Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) located at the ECB.Footnote3 Fourth, it has assumed, at least implicitly, lender of last resort powers for banks (through the granting of Emergency Liquidity Assistance) and arguably also for sovereigns (through the Outright Monetary Transactions programme) (De Grauwe & Ji, Citation2013). And fifth, the ECB’s unconventional monetary policies – from large-scale refinancing operations to a range of asset-purchase programmes – have entailed at least some degree of quasi-fiscal power (Buiter, Citation2020; Diessner, Citation2019; Schelkle, Citation2014).Footnote4

At the same time, a number of new parliamentary fora have been created to hold policy-makers to account for some of their newfound responsibilities. The first three of the aforementioned powers have been matched by novel parliamentary hearings with the chair of the ESRB (the ECB president), the chair of the supervisory board, and the financial assistance working group, while part of the fourth power, Emergency Liquidity Assistance, is administered by national central banks which are subject to scrutiny by their national parliaments (Akbik, Citation2022; Fromage & Ibrido, Citation2018; Högenauer & Howarth, Citation2019).Footnote5 Beyond this, the ECB president has made ad hoc visits to selected national parliaments, in order to discuss crisis policies with national MPs (Heldt & Müller, Citation2021; Tesche, Citation2019).

These laudable efforts notwithstanding, they have not yet sufficed to dispel concerns related to the ECB’s democratic legitimacy altogether. This is not only because the ECB has assumed extra-monetary policy roles, for which the above extra-monetary policy-related accountability fora have been created. Rather, it is due to the fact that the central bank’s intra-monetary policy responsibilities have both deepened and widened throughout the crisis, thereby straying into the fiscal realm, without a related deepening and widening of the democratic accountability arrangements for its core monetary policy-making (Macchiarelli et al., Citation2020). This perilous state of affairs calls for an investigation into what constitutes the democratic legitimacy of the ECB’s monetary policy-making post-crisis, not merely in theory, but also in practice.

In principle, the democratic legitimacy of the ECB can be conceived of as at least four-fold, departing from common distinctions in the literature between input, output, and ‘throughput’ legitimacy (Diessner, Citation2022; Scharpf, Citation1999; Schmidt, Citation2013). Firstly, it manifests itself as limited input legitimacy, namely by means of a one-time act of delegation of policy autonomy codified in the European Treaties. Secondly, it hinges on output legitimacy, that is, fulfilling the central bank’s mandated primary objective of price stability – and, in particular, its self-defined inflation target of around two percent, the achievement of which has been called into question over the past decade. Thirdly, the ECB has increasingly come to rely on ‘throughput’ legitimacy in the form of accountability towards the European Parliament (EP), as an imperfect substitute for its limited input and output legitimacy during the crisis (cf. Torres, Citation2013). While throughput legitimacy also encompasses the sub-dimensions of transparency, inclusiveness, and openness of governance processes – especially towards civil society (Schmidt, Citation2013) –, accountability has come to be viewed as the central counterpart and ‘flipside’ to the ECB’s far-reaching statutory independence (Braun, Citation2017), while transparency is commonly viewed as a precondition to achieve it. And lastly, the central bank arguably also depends on perceptions of all of the other three dimensions, namely among European citizens and their elected representatives (see Jones, Citation2009; Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2019).

Against this backdrop, the article argues that the ECB’s democratic legitimacy predominantly rests upon its accountability towards the EP, or what it calls ‘legitimacy-as-accountability’. It further contends that the ECB’s legitimacy is in question along several of the aforementioned dimensions. On the one hand, its throughput legitimacy is in question due to the limited degree of substantive accountability the ECB has towards the EP. On the other hand, while perceptions of legitimacy matter, they are hard to grasp and even harder to steer, and are thus difficult to rely upon with confidence. To illustrate both points, the article leverages survey data (Collignon & Diessner, Citation2016) as well as élite interviews with members of the European Parliament and their staff (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).Footnote6 The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The second and third sections dissect the ECB’s ‘legitimacy-as-accountability’ in theory as well as in practice. The fourth section introduces and discusses different policy proposals to enhance the ECB’s accountability and, by implication, its democratic legitimacy. The fifth and final section concludes with a reflection on the promises and pitfalls of the ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability towards the European Parliament(s) during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

The ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability in theory: perceptions matter

When it comes to legislative and executive scrutiny of the ECB’s actions, the central bank is primarily accountable to MEPs in the European Parliament, while also regularly reporting to the Council of the EU, the European Commission and the European Council (at least on an annual basis) (Article 284(3) TFEU; Article 15(3), Statute of ESCB & ECB). Over the years, however, the ECB’s quarterly hearings with the EP’s Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee (ECON) – known as the ‘Monetary Dialogue’ –, have arguably become the ‘main accountability channel’ for the central bank, alongside the presentation and discussion of its annual report as well as timely responses to written questions formulated by MEPs (see Fraccaroli et al., Citation2018). The Monetary Dialogue stems from an initiative based on a sub-clause of Article 284(3) TFEU, which states that ‘[t]he President of the European Central Bank and the other members of the Executive Board may, at the request of the European Parliament or on their own initiative, be heard by the competent committees of the European Parliament’. The clause eventually led to an initiative report – or ‘INI report’ in European Parliament parlance – by the former ‘Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs and Industrial Policy’ of the EP under the pioneering leadership of its then-chair, Christa Randzio-Plath (see European Parliament, Citation1998). The INI report invoked a range of Treaty provisions to suggest an involvement of the Parliament in monetary affairs through ‘assent’, ‘cooperation’, and ‘consultation’ procedures, and by building on prior experience with exchanges between the EP and the European Monetary Institute (the forerunner of the ECB). It stipulated that the ECON Committee and the central bank engage one another in three ‘fields of action’, namely ‘the procedure for appointing members of the ECB’s Executive Board; reporting to the European Parliament; [and] the ECB’s publications’ (European Parliament, Citation1998, pp. 10–11), which were further specified and laid down in the EP’s Rules of Procedure (see Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).

Over the course of the past two decades, successive ECB Presidents and corresponding parliamentary legislatures have leveraged these structures to develop a range of practices with the aim of ensuring an ex post answerability of the central bank to the elected representatives of European citizens. At the same time, however, the central bank’s accountability in general, and the Monetary Dialogue in particular, have never been free of critique from both academics and think tanks (Dawson et al., Citation2019; Gros, Citation2004; Wyplosz, Citation2005). These criticisms have typically centred around the predominantly procedural nature of the ECB’s accountability towards the EP, which has no substantive means at its disposal to sanction or reward the central bank (Schmidt & Wood, Citation2019, p. 8). In this context, several recent reports by civil society organisations have highlighted issues with the current accountability arrangements for the ECB (Braun, Citation2017) and have formulated concrete proposals to improve both the structures and the practice of the Monetary Dialogue (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).

On top of this procedural dimension of the ECB’s legitimacy, which we can operationalise through the lens of accountability, Europe’s central bankers are arguably also faced with another kind of legitimation challenge, namely one which is of a more perceptual nature. In short, whether the actions and decisions of an institution can be found to be legitimate (or not) is also a matter of whether these are perceived to be legitimate (or not). A growing literature in the social sciences – purportedly going back to Max Weber and finding its latest incarnation in international relations debates – has come to stress the importance of public perceptions and ‘legitimacy beliefs’, highlighting their foundational role in processes of legitimation (see Anderson et al., Citation2019; Nielson et al., Citation2019).Footnote7 In Tallberg and Zürn’s words, for instance, reconciling the institutions of international organisations (IOs) – including those of the EU – with ‘democracy’s preservation requires that IOs both are structured in accordance with democratic principles and are perceived by citizens as legitimate systems of governance’ (Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2019, p. 2, emphasis added). To this end, the authors suggest conceptualising perceptions of legitimacy as ‘beliefs of audiences that an IO’s authority is appropriately exercised’ (ibid.: 3). As a supranational EU institution with delegated responsibilities, the ECB can reasonably be expected to care about, and be affected by, such perceptions of its legitimacy as well (Jones, Citation2009).

On the whole, this section suggests that the ECB’s legitimacy mostly manifests itself in the form of perceived throughput legitimacy and, in particular, perceived accountability towards the EP. In line with these suggestions, the next section zooms into the central bank's legitimacy-as-accountability in practice. Before proceeding, however, a caveat is in order. Ascertaining the legitimacy perceptions among the public as well as other audiences is far from straightforward. Therefore, the article pursues an indirect and inductive approach. It surveys the views of citizens’ elected representatives in the European Parliament and thereby aims to shed light on both the ECB’s procedural and perceived legitimacy through the lens of democratic accountability.

The ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability towards the European Parliament in practice

Democratic accountability is a multi-dimensional concept which encompasses both substantive and non-substantive (or procedural) elements. Given the lack of substantive accountability mechanisms foreseen in the Treaties, the ECB’s accountability in practice is perhaps best thought of as an ‘answerability’ to European citizens and their elected representatives (Akbik, Citation2022; Braun, Citation2017; Diessner, Citation2018). However, answerability is a rather broad and qualitative category which requires careful operationalisation if one is to gain an empirical sense of an institution’s de facto accountability (ibid.; Kluger Dionigi, Citation2018; Schonhardt-Bailey et al., Citation2022). This article seeks to examine answerability by means of leveraging the views of those actors whom the ECB ultimately finds itself answerable to, namely MEPs in the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) who engage the central bank through the quarterly Monetary Dialogue. It does so in a two-fold manner, drawing on primary data from a survey conducted for Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016) as well as interview data collected for Jourdan and Diessner (Citation2019a).

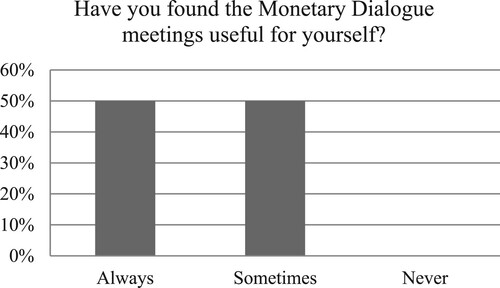

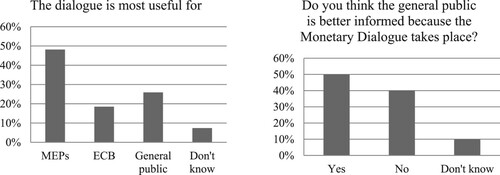

For an EP study which exploited the changeover in ECB presidents from Jean-Claude Trichet to Mario Draghi during the legislature of 2009–2014, Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016) collected data through a survey of members of the ECON Committee which was conducted towards the end of the Parliamentary term.Footnote8 Specifically, the survey items of interest to this article entail three broad categories, namely: the overall usefulness of the Monetary Dialogue; the perceived impact of the dialogue both in general and on the management of the Eurozone crisis in particular; and the ECB’s transparency as a precondition for successful accountability.Footnote9 In terms of Tallberg and Zürn’s (Citation2019) conception of institutional legitimacy, these perceptions among elected representatives arguably constitute a point at which the procedural and perceived legitimacy of the ECB overlap. On the whole, the survey data suggest a cautiously optimistic assessment of the ECB’s accountability in the eyes of MEPs, with all participants considering the hearings with the ECB president to be at least sometimes useful for themselves and, to a lesser extent, for the general public (see as well as ) below).

Figure 1. Perceived usefulness of the Monetary Dialogue in the eyes of MEPs. Source: Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2020a) based on data from Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016)

Figures 2(a) and 2(b). Perceived usefulness of the Monetary Dialogue for different audiences and for the audience of the general public in the eyes of MEPs. Source: Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2020a) based on data from Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016)

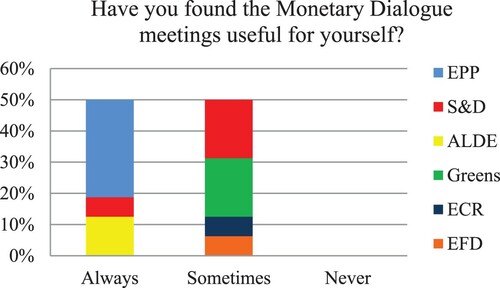

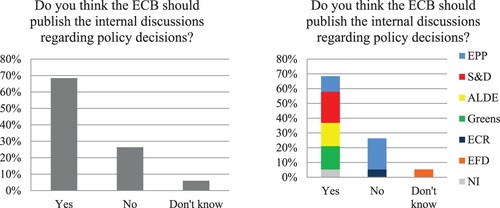

At the same time, however, several noteworthy patterns can be detected. To begin with, MEPs’ assessment of the Monetary Dialogue appears to be subject to partisan dynamics, with Parliamentarians from conservative and liberal parties generally being more content with the dialogue, and MEPs from centre-left, green and Eurosceptic parties displaying some more reservation (see below).

Figure 3. Perceived usefulness of the Monetary Dialogue in the eyes of MEPs from different groups in the EP. Source: Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2020a) based on data from Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016). Note: Acronyms for parties during the seventh EP legislature; EPP = European People’s Party, S&D = Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, ALDE = Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, Greens = The Greens-European Free Alliance, ECR = European Conservatives and Reformists, EFD = Europe of Freedom and Democracy

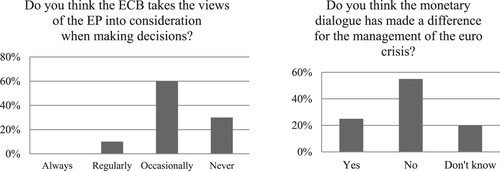

Second, MEPs reveal an acute awareness of the fact that their interventions tend to be of limited input into the ECB’s decision-making, both in general and especially so during times of crisis (see ) below), a circumstance which is closely intertwined with the central bank’s extraordinary degree of independence. However, MEPs accept this far-reaching independence both tacitly and explicitly: when directly asked about ECB independence, every single respondent declared it to be ‘a good thing’ that is deemed to be worthy of preservation (Diessner, Citation2018, p. 29).

Figures 4(a) and 4(b). Perceived input from the Monetary Dialogue into the ECB’s decision-making in the eyes MEPs. Source: Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2020a) based on data from Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016)

As argued above, one way through which the central bank has sought to make up for its limited input legitimacy has been to augment the quality of its throughput legitimacy over time. Among the different sub-dimensions of throughput legitimacy, central bank transparency in particular has been seen as an indispensable prerequisite to achieve successful accountability in the first place, be it of a substantive or non-substantive nature (Dinçer et al., Citation2019; van der Cruijsen & Eijffinger, Citation2010; cf. Koop & Reh, Citation2019). But how do MEPs perceive the ECB’s transparency? ) below suggest that most representatives would appreciate a higher degree of central bank transparency, particularly when it comes to the internal deliberation leading up to the formulation of policy decisions. Once again, however, some evidence for a partisan dynamic is detectable, with MEPs from parties to the right of the centre tending to be more satisfied with current levels of ECB transparency than those on the centre-left.

Figures 5(a) and 5(b). Perceived transparency of the ECB’s decision-making among MEPs from different groups in the EP. Source: Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2020a) based on data from Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016). Note: Acronyms for parties during the seventh EP legislature; EPP = European People’s Party, S&D = Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, ALDE = Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, Greens = The Greens-European Free Alliance, ECR = European Conservatives and Reformists, EFD = Europe of Freedom and Democracy

Beyond these survey responses by MEPs from the 2014–2019 legislature, Jourdan and Diessner (Citation2019a) have sought to collect interview data from key members of the ECON committee and their staff towards the end of the 2014–2019 legislature as well. The interview data tend to confirm the mixed survey results. While most interviewees echo the general appreciation of President Draghi’s handling of the Monetary Dialogue with skill and shrewdness throughout his tenure, several MEPs also critically reflect on the ECON committee’s somewhat submissive attitude towards the ECB, pointing to a lack of focused participation among many members of the committee (Interviews 3, 4 and 5).

Although an ethos of collegiality and mutual trust between the central bank and MEPs may have proven expedient for both institutions during the Eurozone crisis (Collignon & Diessner, Citation2016; Torres, Citation2013), interviewees suggest that it would be inappropriate for successful parliamentary oversight if the ECON committee were to be ‘too bending’ (Interview 3) towards the central bank or if MEPs were to ‘just flatter’ (Interview 4) or have a mere ‘thank you attitude’ (Interview 5) towards the ECB and its president (see also Buiter, Citation1999; cf. Issing, Citation1999; Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a). One potent channel through which the ECON committee has increasingly sought to make its voice heard, however, is that of appointments to the ECB’s Executive Board, for which MEPs have long demanded to obtain gender-balanced shortlists well in advance, and as a consequence of which the ECON committee has at times formally withheld its support for nominated candidates (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019b). Nonetheless, there remains significant scope for improving the ECB’s accountability and, by implication, its (throughput) legitimacy.

Enhancing the ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability towards the European Parliament post-crisis

Many of the aforementioned issues have their roots both in the structures and in the practices of the Monetary Dialogue as well as the EMU's broader accountability framework (Markakis, Citation2020). As a result, several recent reports prepared by think tanks and academics have put forward a number of different reform proposals, on top of long-standing calls for greater transparency of the ECB.Footnote10 Engaging with these proposals – and with the people or organisations that formulate them – constitutes one way in which the ECB may be able to enhance its throughput legitimacy in terms of ‘inclusiveness and openness to civil society’ (Schmidt, Citation2013, p. 7; see Smismans, Citation2003; Zeitlin & Pochet, Citation2005). This may entail granting access to interviewees (Braun, Citation2017) or taking part in expert roundtables and through follow-up discussions (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).

This type of engagement has recently become more formalised in the context of the ECB’s strategy review, which was preceded by a series of ‘ECB Listens’ events (ECB, Citation2021). The central bank has announced that this outreach activity with a range of different stakeholders beyond financial market participants will not remain a one-off but will become a regular exercise (Lagarde, Citation2021).Footnote11 Such a ‘civil society dialogue’ (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a) could initially take place on an annual basis and be dedicated to a set of pre-specified topics of public concern, such as climate change or inequality. In terms of democratic legitimation, these efforts might amount to enhancing the ECB’s limited input legitimacy, depending on the extent to which they do provide ‘inputs’ that are reflected in ECB decision-making – or, at the very least, the perception thereof. While laudable, engagement with civil society organisations can only be one building block in the broader endeavour to ramp up the ECB’s democratic legitimacy, however.

This is because, at a deeper level of analysis, the central bank – and those who are tasked with holding it to account – find themselves faced with a seemingly paradoxical situation post-crisis. On the one hand, the ECB’s enlarged monetary policy role implies the need for oversight over a wider range of issues. On the other hand, however, it is frequently suggested that more effective scrutiny by the European Parliament would require deeper specialisation and a better focus among MEPs (Interview 2; Claeys & Domínguez-Jiménez, Citation2020). A way to square the circle of both wider and deeper scrutiny could lie in making more substantive use of existing but underappreciated channels of accountability (such as the EP’s annual resolution on the ECB) (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a) and, in particular, in considering the creation of a parliamentary sub-committee dedicated to overseeing the central bank (Chang & Hodson, Citation2019; Lastra, Citation2020).Footnote12 The latter could be accomplished without amending the EU Treaties and could much rather be accommodated within the existing rules of procedure of committees in the EP (Interview 1).Footnote13

Among the issues that an ECB oversight sub-committee would help address is the sheer size of the ECON committee, which is arguably in need of reduction to ensure greater continuity among a roster of returning MEPs who specialise in ECB policy-making (see also Tucker, Citation2021, p. 1024). In practice it is already the case that only a fairly limited number of MEPs regularly takes part in the Monetary Dialogue – a reality that could be reflected by downsizing the dialogue to those MEPs, for example (as long as these reflect the different party groups represented in the parliament). While reducing the size of ECON could also be achieved by limiting participation to MEPs from Eurozone member states, this type of differentiation is likely to pose challenges in terms of Articles 9 and 10 TEU, amongst others things (Curtin & Fasone, Citation2017; Fromage, Citation2018).

A sub-committee would primarily be in charge of the following, non-exhaustive set of tasks: preparing and conducting the quarterly monetary dialogues with the ECB president; concerting and coordinating written questions to the ECB; drafting the annual resolution on the ECB; preparing the work of ECON as regards non-/legislative acts concerning the ECB; and participating in appointment procedures for members of the ECB executive board. It could make use of other parliamentary scrutiny powers as well, such as requesting in-camera hearings with ECB officials where need be. It may also act as a visible interlocutor for civil society on issues relating to Eurozone monetary policy as well as draw on the advice of the external expert panel more flexibly when it deems necessary (Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).Footnote14 A pertinent question remains, however, in terms of the incentives for the ECON committee to reduce its own size. While a push towards forming a sub-committee had been undertaken by the coordinators of the political groups within ECON ahead of the EP elections in early-2014, a renewed effort would arguably be warranted nowadays in order to future-proof the ECB’s accountability.

This becomes all the more relevant in light of the fact that the central bank’s responsibilities are bound to remain extensive as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, in response to which the ECB launched a Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme in a bid to do ‘whatever it takes 2.0’ (Quaglia & Verdun, Citation2021). This suggests that the ECB’s balance sheet will remain enlarged and its entanglements with fiscal policy-making will remain deepened for the foreseeable future (Diessner, Citation2020a), compounding the need for better parliamentary oversight. At the same time, the Monetary Dialogue could only be carried out remotely during the pandemic, with the help of digital conferencing tools, although it seemingly continued without significant disruptions (European Parliament, Citation2022). Whereas the ECB revamped its monetary policy strategy by means of a wide-ranging review which came to its belated conclusion in the summer of 2021, we are yet to see a similarly structured process in terms of reviewing and revamping its accountability arrangements with the European Parliament. A first step in this direction would be to launch talks about an inter-institutional agreement between the ECB and the EP, as recently put forward by the Socialists and Democrats group, which would include ‘[e]nhancing the Monetary Dialogue’, ‘[s]trengthening the role of the European Parliament in ECB nominations’, and sending ECON ‘committee delegations to the ECB bi-annually’ (S&D, Citation2021).

Conclusion: promises and pitfalls of the ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability towards the European Parliament(s) post-covid

This article has sought to assess the ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability towards the European Parliament in light of the recent academic and policy-oriented literature, and by means of invoking data from élite interviews and a survey of MEPs’ perceptions of the central bank’s accountability. While the ECB enjoys decidedly limited input legitimacy, it has come to rely on a non-substantive form of accountability as the key pillar of its democratic legitimation instead. The latter is perceived relatively positively by citizens’ representatives. However, interview and survey data also reveal that MEPs are aware of the need to enhance the accountability structures and practices currently in place in the monetary policy domain of EMU, which has been echoed in several recent policy reports as well as calls for an inter-institutional agreement between the ECB and the EP. These findings not only imply that the ECB’s fractional input legitimacy increases the overall pressure on monetary policy-makers to achieve their mandated outputs (Jones, Citation2009), but also suggest that such ‘input deficits’ can only partially be offset by improvements in throughput legitimacy (cf. Schmidt, Citation2013, p. 18). Like other major central banks, the ECB has reacted to this challenge by paying increased attention to public perceptions of its legitimacy. As a result, it has started to engage with new kinds of stakeholders, such as civil society organisations. The jury is still out, however, in terms of whether these outreach activities will prove capable of shaping the public’s legitimacy beliefs in the long run, given the highly uncertain political-economic outlook after the COVID-19 crisis.

Yet, the potential power of the ECB’s legitimacy-as-accountability should not be discounted altogether either, at least in the short run. After all, the tumultuous year of 2020 has produced remarkable evidence of how powerful the mere perception of throughput legitimacy, and especially that of accountability, can sometimes turn out to be. When the ultra vires ruling of the German Federal Constitutional Court on the ECB’s Public Sector Purchase Programme stunned even the more seasoned observers of European affairs in May 2020 (de Boer & van ‘t Klooster, Citation2020; Diessner, Citation2020b), few would have anticipated just how smoothly the conflict would eventually come to be defused. All that it seemingly took was a textbook exercise in procedural and perceived legitimacy, as outlined by the Court itself: the ECB made available previously undisclosed documents via the Bundesbank and provided more detailed minutes which showed that it had taken the proportionality of its unconvential policies into account (transparency); the Bundesbank discussed these and other issues with a committee of the Bundestag behind closed doors (non-substantive accountability); the Bundestag, the Bundesbank and the federal government (in the person of then-finance minister Olaf Scholz) deemed this procedural resolution to have been sufficient (perceptions); and the Court agreed with this interpretation.

Having said this, a healthy dose of scepticism appears warranted nevertheless. Further court cases are looming, not least with regard to the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, and it is unclear whether the fallout from these could be defused just as easily by making recourse to procedural means.Footnote15 Thus, it remains a pertinent question for future research whether the all but bruising episode of the German ultra vires ruling – and its eventual resolution with the help of perceived throughput legitimacy – will come to be seen as the new norm or much rather remain an anomaly in the politics of monetary policy and legislative oversight in EMU.

List of interviewees

Code – Institution, Position, Place, Date

01 – European Parliament, ECON Committee Secretariat, Official, Brussels, November 2018

02 – European Parliament, Member of Parliament Staff, Brussels, November 2018

03 – European Parliament, Member of Parliament Staff, Brussels, November 2018

04 – European Parliament, Member of Parliament, Brussels, November 2018

05 – European Parliament, Member of Parliament, Brussels, November 2018

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sebastian Diessner

Sebastian Diessner is an assistant professor at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. His research focuses on the politics of economic policy in Europe and Japan and on the interaction between technological and institutional change across capitalist democracies.

Notes

1 The author would like to thank the special issue workshop participants, in particular Anna-Lena Högenauer and Marcel Magnus, as well as the editors Diane Fromage and Karolina Boronska-Hryniewiecka for their detailed and helpful comments.

2 This article draws substantively on Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2020) as well as Jourdan and Diessner (Citation2019a) and Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016).

3 Note, however, that the Single Supervisory Mechanism and Single Resolution Mechanism functions are formally separated from the central bank.

4 Note that these extended responsibilities do not necessarily have to be thought of as novel or unprecedented powers for a central bank and in many cases rather suggest a return to some of the historical core functions of central banking (see Goodhart, Citation2010; Monnet, Citation2021).

5 The bewildering variety of hearings and dialogues is said to confuse members of the European Parliament themselves sometimes. During Mario Draghi’s presidency, hearings with the ESRB Chair took place immediately after the regular Monetary Dialogues, but this practice seems to have changed during the presidency of Christine Lagarde.

6 As such, the article can be seen as a complement to Fraccaroli et al. (Citation2022), in the sense that the latter focusses on the messages that the ECB sends when in Parliament, while the former aims to shed light on how the ECB is received by said Parliamentarians. For a recent and illuminating study of the messages that Parliamentarians send to the ECB, in turn, see Ferrara et al. (Citation2021).

7 Note, however, that a significant strand of social science research departs from the recognition that “the (supposedly) Weberian ‘belief-in-legitimacy’ concept is problematic” (see Stanley, Citation2014, p. 899, and sources cited therein, including but not limited to, Beetham, Citation1991; Clark, Citation2003; Reus-Smit Citation2007).

8 For further information on the survey data, see Collignon and Diessner (Citation2016:, pp. 1307–1309).

9 To be sure, the perceived usefulness of the Monetary Dialogue on behalf of MEPs does not translate perfectly to the perceived throughput legitimacy of the ECB, but it can arguably serve as a first proxy.

10 The focus on reforms of the Monetary Dialogue in this article does not imply that other reforms are less important or pressing, but rather that the former are deemed to be more realistically achievable than the latter within the confines of the existing Treaty framework (see Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).

11 On the recent proliferation of stakeholder engagement among EU agencies = and the promises and pitfalls thereof = see Arras and Braun (Citation2018), Braun and Busuioc (Citation2020) or Busuioc and Jevnaker (Citation2022).

12 Such a ‘Sub-Committee on Monetary Affairs’ had, in fact, existed before the creation of the ECB, facilitating consultations between the Parliament and the European Monetary Institute. An alternative arrangement may consist of an EP working group, as has been the case for Banking Union-related matters (see Fromage & Ibrido, Citation2018; Jourdan & Diessner, Citation2019a).

13 Procedurally, the establishment of a sub-committee would require authorization from the Conference of the Presidents of the EP, while its workings would be subject to the control of the ECON committee (Article 203, EP Rules of Procedure) (see Curtin & Fasone, Citation2017, pp. 131–134).

14 The Monetary Dialogues are informed by a group of external experts who write briefing papers (and sometimes present those papers to MEPs and their staff) on the two topics chosen ahead of each dialogue. For examples of reflection papers around the end of the 2009–2014 and 2014–2019 legislatures, see Collignon (Citation2014) and Macchiarelli et al. (Citation2019), respectively.

15 For a more optimistic take on why procedural remedies may suffice after all, see the speech by the president of the Court of Justice of the EU, Lenaerts (Citation2021), at the ECB Legal Conference in 2021.

References

- Akbik, A. (2022). The European Parliament as an accountability forum: Overseeing the Economic and Monetary union. Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, B., Bernauer, T., & Kachi, A. (2019). Does international pooling of authority affect the perceived legitimacy of global governance? The Review of International Organizations, 14(4), 661–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9341-4

- Arras, S., & Braun, C. (2018). Stakeholders wanted! Why and How European Union agencies involve Non-state stakeholders. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(9), 1257–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1307438

- Beetham, D. (1991). The legitimation of power. Palgrave.

- Braun, B. (2017). Two Sides of the same coin? Independence and accountability of the European Central bank. Transparency International EU.

- Braun, C., & Busuioc, M. (2020). Stakeholder engagement as a conduit for regulatory legitimacy? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(11), 1599–1611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1817133

- Buiter, W. H. (1999). Alice in euroland. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 37(2), 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00159

- Buiter, W. H. (2020). Central banks as Fiscal players: The drivers of Fiscal and Monetary policy space. Cambridge University Press.

- Busuioc, M., & Jevnaker, T. (2022). Eu agencies’ stakeholder bodies: Vehicles of enhanced control, legitimacy or bias? Journal of European Public Policy, 29(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1821750

- Chang, M., & Hodson, D. (2019). Reforming the European Parliament’s Monetary and Economic dialogues: Creating accountability through a Euro area oversight subcommittee. In O. Costa (Ed.), The European Parliament in times of EU crisis: Dynamics and transformations (pp. 343–364). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Claeys, G., & Domínguez-Jiménez, M. (2020). How can the European Parliament better oversee the european central bank?. Note for the European Parliament’s committee on economic and monetary affairs, PE 652.747.

- Clark, I. (2003). Legitimacy in a global order. Review of International Studies, 29(S1), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210503005904

- Collignon, S. (2014). Central bank accountability in times of crisis. The monetary dialogue: 2009–2014. Note for the european parliament’s committee on economic and monetary affairs, PE 507.482.

- Collignon, S., & Diessner, S. (2016). The ECB’s Monetary Dialogue with the European Parliament: Efficiency and accountability during the Euro crisis? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(6), 1296–1312. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12426

- Curtin, D., & Fasone, C. (2017). Differentiated representation: Is a flexible European Parliament desirable? In B. De Witte, A. Ott, & E. Vos (Eds.), Between flexibility and disintegration: The trajectory of differentiation in EU Law (pp. 118–145). Edward Elgar.

- Dawson, M., Maricut-Akbik, A., & Bobic, A. (2019). Reconciling independence and accountability at the European Central Bank: The false promise of proceduralism. European Law Journal, 25(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12305

- de Boer, N., & van ‘t Klooster, J. (2020). The ECB, the courts and the issue of democratic legitimacy afterweiss. Common Market Law Review, 57(6), 1689–1724. https://doi.org/10.54648/COLA2020765

- De Grauwe, P., & Ji, Y. (2013). Self-Fulfilling crises in the eurozone: An empirical test. Journal of International Money and Finance, 34, 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2012.11.003

- Dermine, P. (2019). Out of the comfort zone? The ECB, financial assistance, independence and accountability. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 26(1), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X18822793

- Diessner, S. (2018). Does the Monetary Dialogue further the ECB’s accountability? In Think Tank Europa (Ed.), Enhancing Parliamentary Oversight in the EMU: Stocktaking and Ways forward (pp. 25–30). Think Tank Europa.

- Diessner, S. (2019). Essays in the Political Economy of central banking [Doctoral dissertation]. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Diessner, S. (2020a). Mainstreaming Monetary Finance in the COVID-19 crisis. Positive Money Europe. http://www.positivemoney.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Mainstreaming-Monetary-Finance.pdf

- Diessner, S. (2020b). Can greater central bank accountability defuse the conflict between the bundesverfassungsgericht and the European Central bank? LSE EUROPP Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2020/05/13/can-greater-central-bank-accountability-defuse-the-conflict-between-the-bundesverfassungsgericht-and-the-european-central-bank/

- Diessner, S. (2022). The Politics of Monetary Union and the ECB’s democratic legitimacy as a Strategic actor. In D. Adamski, F. Amtenbrink, & J. de Haan (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook on European Monetary, Economic and Financial Market integration. Cambridge University Press. (forthcoming).

- Dinçer, N., Eichengreen, B., & Geraats, P. (2019). Transparency of monetary policy in the postcrisis world. In David G. Mayes, Pierre L. Siklos, and Jan-Egbert Sturm (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Central Banking (287–336). https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-the-economics-of-central-banking-9780190626198?cc=nl&lang=en&

- ECB. (2021). ECB listens – summary report of the ECB listens portal responses. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/search/review/html/ecb.strategyreview002.en.html

- European Parliament. (1998). Report on accountability in the 3rd phase of EMU. Committee on economic and monetary affairs and industrial policy, brussels: European Parliament.

- European Parliament. (2015). The ECB’s role in the design and implementation of (Financial) Measures in crisis-hit countries. Compilation of notes for the European Parliament’s Economic and Monetary Affairs committee.

- European Parliament. (2022). ECON committee meetings. EP website [last retrieved 23 January 2022]. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/econ/home/highlights

- Ferrara, F., Masciandaro, D., Moschella, M., & Romelli, D. (2021). Political voice on Monetary policy: Evidence from the parliamentary hearings of the European Central bank. BAFFI CAREFIN Working Papers, 21159. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3820745

- Fraccaroli, N., Giovannini, A., & Jamet, J.-F. (2018). The evolution of the ECB’s accountability practices during the crisis. ECB economic bulletin, issue 5/2018.

- Fraccaroli, N., Giovannini, A., & Jamet, J.-F. (2022). The ECB in face of the crises: Does the ECB speak differently when in parliament? Journal of Legislative Studies.

- Fromage, D. (2018). A parliamentary assembly for the eurozone? ADEMU Working Paper, 2018/134. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3200043

- Fromage, D., Dermine, P., Nicolaides, P., & Tuori, K. (2019). ECB independence and accountability today: Towards a (necessary) redefinition? Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 26(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X19827819

- Fromage, D., & Ibrido, R. (2018). The ‘banking Dialogue’ as a model to improve parliamentary involvement in the Monetary dialogue? Journal of European Integration, 40(3), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1450406

- Goodhart, C. A. E. (2010). The changing role of central banks. BIS Working Papers, 326. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1717776

- Gros, D. (April 2004). 5 years of Monetary dialogue. CEPS Briefing Paper.

- Heldt, E. C., & Müller, T. (2021). Bringing independence and accountability together: Mission impossible for the European Central bank? Journal of European Integration. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2021.2005590

- Högenauer, A.-L., & Howarth, D. (2019). The parliamentary scrutiny of Euro area national central banks. Public Administration, 97(3), 576–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12576

- Issing, O. (1999). The eurosystem: Transparent andAccountable or 'Willem in euroland'. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 37(2), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00175

- Jones, E. (2009). Output legitimacy and the global financial crisis: Perceptions matter. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(5), 1085–1105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.02036.x

- Jourdan, S., & Diessner, S. (2019a). From Dialogue to scrutiny: Strengthening the parliamentary oversight of the European Central bank. Positive Money Europe.

- Jourdan, S., & Diessner, S. (2019b). The EU can do better than gentlemen’s agreements behind closed doors. Euractiv. www.euractiv.com/section/economic-governance/opinion/ecb-reshuffle-the-eu-can-do-better-than-gentlemens-agreements-behind-closed-doors/

- Kluger Dionigi, M. (2018). How Effective is the Economic Dialogue as an accountability tool? In Think Tank EUROPA (Ed.), Enhancing Parliamentary Oversight in the EMU: Stocktaking and Ways forward (pp. 20–24). Think Tank Europa.

- Koop, C., & Reh, C. (2019). Europe’s bank and Europe’s citizens: Accountability, transparency – legitimacy? Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 26(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X19827906

- Lagarde, C. (2021, July 8). Opening remarks at Press conference. Frankfurt am main.

- Lastra, R. (2020). Accountability Mechanisms of the bank of England and of the European Central Bank. Study for the committee on Economic and Monetary affairs. European Parliament.

- Lenaerts, K. (2021, November 25). Proportionality as a matrix principle promoting the effectiveness of EU Law and the legitimacy of EU action. Speech at the ECB legal conference.

- Macchiarelli, C., Gerba, E., & Diessner, S. (2019). The ECB’s unfinished business: Challenges ahead for EMU monetary and fiscal policy architecture. Note for the European Parliament’s committee on economic and monetary affairs, PE 638.423.

- Macchiarelli, C., Monti, M., Wiesner, C., & Diessner, S. (2020a). The growing challenge of legitimacy amid central bank independence. In C. Macchiarelli, M. Monti, C. Wiesner, & S. Diessner (Eds.), The European central bank between the Financial crisis and populisms (pp. 103–121). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Macchiarelli, C., Monti, M., Wiesner, C., & Diessner, S. (2020). The European central bank between the Financial crisis and populisms. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Markakis, M. (2020). Accountability in the Economic and Monetary Union: Foundations, policy, and governance. Oxford University Press.

- Monnet, E. (2021). La Banque providence: Démocratiser les Banques centrales et la monnaie. Éditions du Seuil.

- Nielson, D. L., Hyde, S. D., & Kelley, J. (2019). The elusive sources of legitimacy beliefs: Civil society views of international election observers. Review of International Organizations 14 (4): 685–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9331-6

- Quaglia, L., & Verdun, A. (2021). The european central bank and the pandemic: Whatever it takes 2.0?. Paper presented at the european university institute, Florence, 9 December.

- Reus-Smit, C. (2007). International crises of legitimacy. International Politics, 44(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800182

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Schelkle, W. (2014). Fiscal Integration by default. In P. Genschel, & M. Jachtenfuchs (Eds.), Beyond the Regulatory polity? The European Integration of core state powers (pp. 105–123). Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, outputand‘throughput’. Political Studies, 61(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

- Schmidt, V. A. (2020). Europe's crisis of legitimacy: Governing by Rules and ruling by numbers in the eurozone. Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A., & Wood, M. (2019). Conceptualizing throughput legitimacy: Procedural mechanisms of accountability, transparency, inclusiveness and openness in EU governance. Public Administration, 97(4), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12615

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C., Dann, C., & Chapman, J. (2022). The accountability Gap: Deliberation on Monetary policy in britain and America during the financial crisis. European Journal of Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2022.102209

- Smismans, S. (2003). European civil society: Shaped by discourses and institutional interests. European Law Journal, 9(4), 473–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0386.00187

- Socialists and Democrats (S&D). (2021). Enhancing ECB’s democratic legitimacy must accompany its rise to crucial crisis fighter. S&D website [last retrieved 23 January 2022], https://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/newsroom/enhancing-ecbs-democratic-legitimacy-must-accompany-its-rise-crucial-crisis-fighter-say

- Stanley, L. (2014). ‘We're reaping what We sowed’: Everyday crisis narratives and acquiescence to the Age of austerity. New Political Economy, 19(6), 895–917. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.861412

- Tallberg, J., & Zürn, M. (2019). The legitimacy and legitimation of international organizations: Introduction and framework. The Review of International Organizations, 14(4), 581–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7

- Tesche, T. (2019). Instrumentalizing EMU’s democratic deficit: The ECB’s unconventional accountability measures during the Eurozone crisis. Journal of European Integration, 41(4), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1513498

- Torres, F. (2013). The EMU’s legitimacy and the ECB as a strategic political player in the crisis context. Journal of European Integration, 35(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774784

- Tucker, P. (2021). How the European central bank and other independent agencies reveal a Gap in constitutionalism: A spectrum of institutions for commitment. German Law Journal, 22(6), 999–1027. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2021.58

- van der Cruijsen, C. A., & Eijffinger, S. C. W. (2010). From actual to perceived transparency: The case of the European Central bank. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(3), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2010.01.007

- Wyplosz, C. (2005). European Monetary union: The dark sides of a major success. Economic Policy, 21(46), 207–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2006.00158.x

- Zeitlin, J., & Pochet, P. (Eds.) (2005). The open method of Co-ordination in action: The European employment and Social inclusion strategies. Peter Lang.