ABSTRACT

More than a decade has passed since the Lisbon Treaty explicated two channels of democratic representation in the European Union (EU): one directly through the European Parliament (EP) and one indirectly through national parliaments. This review article uses a wave of recent case studies to analyse how relations between national parliaments and the EP have evolved in practice in the post-Lisbon period. We develop a conceptual framework of the organisation of inter-parliamentary relations that sets them between patterns of intensive, coordinated action and areas of competition among the involved parliaments. We use the recent case studies to identify the dynamics in different EU policy fields and to assess some first expectations about the factors that drive the variation between them.

Introduction

It has been more than a decade since the Lisbon Treaty abandoned any suggestion that the European Union (EU) would evolve into a federal state in which the main source of democratic legitimacy would be located at the supranational level. Instead the Treaty explicated that the EU is founded on two channels of democratic representation, one directly through the European Parliament (EP) and one indirectly through national governments and the national parliaments to which they are accountable (Art. 10.2 TEU).

This confirms the long-perceived multilevel character of EU governance, which rests on a distinct and novel structure of democratic legitimacy (cf. Bellamy & Kröger, Citation2016; Crum & Fossum, Citation2009). From the perspective of the EU as a multilevel system, the way the ‘vertical’ relation between the EP, on the one hand, and national parliaments, on the other, has shaped up is of particular interest (see also Fromage & Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2021). More than a decade after the Lisbon Treaty entered into force, we are in a position to come to a more comprehensive assessment of the way the relations between national parliaments and the EP have shaped up than the literature has offered so far (see also Fromage & Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2021; Winzen, Citation2022). One reason for that is that it simply requires time for new institutional relations to settle in practice. From early on, the reforms strengthening the position of national parliaments in the EU have provoked considerable academic enthusiasm, tracing initial responses and proposing new theoretical perspectives (Cooper, Citation2012; Lupo & Fasone, Citation2016). Now the initial sentiments of exuberance and antagonism have passed, we can expect the relations between national parliaments and the EP to have been settled by and large.

The early literature on post-Lisbon inter-parliamentary relations has been marked by a tendency to focus on the formal, institutional reforms as they took place (Crum & Fossum, Citation2013; Griglio & Stavridis, Citation2018; Lupo & Fasone, Citation2016). Quite naturally, there has been less systematic evidence for the behavioural responses of the various actors involved. Thus, there is a void in the literature in systematically examining behavioural aspects of inter-parliamentary relations as they might occur in the form of informal contacts or transnational activities across parliaments and their political groups (exceptions are Cooper, Citation2019; Strelkov, Citation2015; Wonka & Rittberger, Citation2014). In reviewing interactions more than ten years after Lisbon, we seek to identify the prevailing relations of national parliaments and the EP in EU decision-making: do they coordinate and are they in intensive contact or do they merely co-exist and shun contact whenever possible? Are their relations marked by cooperation or rather by conflict and competition?

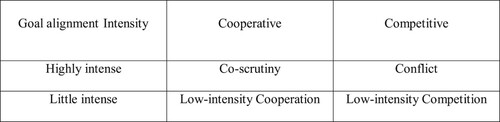

In this article, we develop a conceptual framework to capture the patterns of cooperation or competition between parliaments and to identify the factors that can explain the variation in these patterns across EU policy domains. We conceptualise the parliamentary interactions along two dimensions: their intensity and their level of cooperativeness. We furthermore conjecture that variation along these two dimensions is conditioned by the distribution of competences between the European and the national level and by the extent to which the structure of political contestation coincides with institutional divisions.

This framework is inspired by, and tested against, a wave of case studies that are (a) very recent, (b) explicitly consider the interactions between the EP and national parliaments, and (c) focus on the behavioural rather than the institutional dimension. These case studies cover different EU policy domains, including the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022), Brexit (Högenauer, Citation2021), trade (Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021), the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (AFSJ, Tacea & Trauner, Citation2021), and economic governance (Dias Pinheiro & Dias, Citation2022; Kreilinger, Citation2018). Although most of these studies are very empirical, some offer conceptual tools on which we build here (Crum, Citation2022; Griglio & Stavridis, Citation2018; Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021). In all, this article aims to offer an overarching framework whereby the findings of these studies, and similar future ones, can be located and compared with each other so as to identify trends in the dynamics of inter-parliamentary relations across different EU policy domains.

Our framework and findings speak to two broader strands in current literature on legislative bodies. First, while research on the EP in EU policy-making (e.g. Héritier et al., Citation2019) has recently been paralleled with an emerging body of literature on the role of national parliaments in EU affairs (e.g. Auel et al., Citation2015; Winzen, Citation2012, Citation2022), the ways in which these bodies coordinate or compete are under-researched. We therefore assess relations between national parliaments and the EP across different areas of EU decision-making. Second, we speak to comparative politics literature by evaluating how parliamentarians have adapted to new realities of multi-level governance since the Lisbon Treaty (Bolleyer, Citation2010; Senninger, Citation2017; Strelkov, Citation2015; Wonka & Rittberger, Citation2014).

State of the art

The Lisbon Treaty has fundamentally altered vertical legislative relations in the EU. Following the treaty changes, national parliaments have become increasingly active in EU politics (e.g. Auel et al., Citation2015) and they thereby add to the EP in scrutinising executive actors. Fleshing out the multiple layers of scrutiny and representation in the EU, Crum and Fossum (Citation2009) proposed to understand parliamentary democracy in the EU as a ‘multilevel parliamentary field’. According to this understanding, both parliamentary levels – national and supranational – are inherently important to the EU and mutually reinforce each other. Several scholars picked up this conceptualisation and further refined it (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2016; Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022; Lupo & Fasone, Citation2016).

The increased involvement of national parliaments in the EU has coincided with a rise of Euroscepticism and politicisation (e.g. Fromage & Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2021; Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019). These interrelated observations have provoked a new emerging body of literature, including article collections on parliaments and politicisation (Neuhold & Rosén, Citation2019); national parliaments in politicised European integration (Bellamy & Kröger, Citation2016); or the EU’s poly-crisis and politicisation (Zeitlin et al., Citation2019). Contestation over the EU’s polity and its parliamentary dimension as well as over EU policy is unlikely to end any time soon. Rather, over the last years scholarship observes increasing politicisation in the context of European Union politics (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019; Rauh, Citation2019). Parliaments play essential roles in channelling such contestation.

Under the combined conditions of a new institutional framework and a series of crises, inter-parliamentary relations between the EP and national parliaments have evolved in markedly different ways across EU policy domains. In selected areas, such as Europol, joint oversight by parliaments is formally laid down in the Lisbon Treaty. By contrast, in CFSP, scholarship ascertains tensions between the EP and national parliaments (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2014). In the EU’s trade policy, we can observe a shift from conflict to growing vertical inter-parliamentary cooperation on highly salient issues (Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021). This thus raises the question what are the factors that explain patterns of cooperation or competition between parliaments?

Up until recently there was little research on the way national parliaments have coordinated with the EP in practice since the Lisbon Treaty. Hence, we have little systematic knowledge of whether and why these two kinds of parliamentary bodies, and the politicians and parties involved, are allies or rivals in certain policies or on specific institutional rules. This gap emerges on two sides in the literature. First, research on vertical inter-parliamentary relations exploring concrete instances of decision-making has generally been restricted to particular areas of EU policy-making such as CFSP (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2014; Huff, Citation2015; Peters et al., Citation2010; Wouters & Raube, Citation2012). At the same time, a majority of the literature on inter-parliamentary dynamics explored general patterns of interaction without a particular policy focus (Miklin & Crum, Citation2008; Winzen et al., Citation2015). Hence, beyond idiosyncratic case studies, it was difficult to come to any generalisable statements of inter-parliamentary relations across areas of decision-making.

Second, with few exceptions, research on relations between parliaments has focused on institutionalised patterns of interaction like the Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairs of Parliaments of the European Union (COSAC). Scholarly research, thus, focused on formal, institutionalised forms of inter-parliamentary relations with less attention paid to the informal dimension (Fromage, Citation2016; Hefftler & Gattermann, Citation2015). This leads to overreliance on patterns of cooperation or competition between parliaments over ‘polity’ questions. One example is Cooper’s (Citation2016) analysis of inter-parliamentary relations in the ‘Article 13 Conference’ on economic governance where he focuses on constitutional, institutional and procedural tensions between the EP and national parliaments.

We seek to broaden the perspective of inter-parliamentary relations to behavioural activities on the level of parliaments, political groups or parliamentarians. Existing research on transnational activities is scarce and restricted to the area of CFSP or to selected national parliaments (Finke & Dannwolf, Citation2013; Wonka & Rittberger, Citation2014). The recent case studies on the dynamics of parliamentary interactions in the post-Lisbon EU, on which our framework draws, offer new in-depth empirical information on how parliamentarians use or thwart vertical legislative relations.

Since our focus is on the behavioural patterns between parliaments in the EU’s post-Lisbon policies, we look at ‘informal’ patterns of relations among parliaments on concrete EU policies rather than the institutionalised forms of inter-parliamentary cooperation. While parliaments are our primary units of analysis, we recognise that much of parliamentary interactions across the EP and national parliaments takes place at lower levels, between party groups and parliamentarians (cf. recent research on parties in inter-parliamentary relations, Miklin, Citation2013; Senninger, Citation2019). Thus, to capture fully how parliaments relate to each other in EU politics in practice, we adopt a broad conception of the forms in and the levels at which inter-parliamentary relations take place. At the same time, we restrict our focus to vertical inter-parliamentary relations, i.e. interaction across the levels of the EP and national parliaments rather than horizontal relations among national parliaments.

A wave of recent studies on the ways in which relations between EU parliaments have developed in practice (Crum, Citation2022; Griglio & Stavridis, Citation2018; Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022; Högenauer, Citation2021; Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021; Tacea & Trauner, Citation2021) allow us to advance the conceptualisation of inter-parliamentary relations. These studies provide fine-grained data on inter-parliamentary and transnational interaction that go beyond the current scholarly focus on institutionalised patterns of legislative relations. To map these studies, we seek to apprehend variations in the relations between the EP and national parliaments, setting them between patterns of coordinated action or cooperation and areas of competition among the involved actors. In an effort to grasp possible directions and the intensity of contacts between national parliaments and the EP, we develop a framework that can be used to assess inter-parliamentary relations within and beyond the EU more generally.

Conceptualisation

As we take it that EU decision-making and its legitimacy do indeed depend on a ‘multilevel parliamentary field’ (Crum & Fossum, Citation2009), after ten years into the post-Lisbon period we can actually ask how the EP and national parliaments have come to organise their relations in the EU’s various areas of politics? Have they emerged as allies in holding executive actors accountable or as rivals over legislative competencies? And, do we observe a development towards ‘normal politics’ where parliaments have found their place in the multi-level governance system more than ten years past the treaty’s entry into force? In other words, do we see a ‘settlement’ of the cooperation patterns in the parliamentary field (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022)?

As vertical legislative relations are at the heart of our analysis, we conceptualise inter-parliamentary dynamics along two dimensions. Our primary interest is to understand inter-parliamentary interaction along a continuum that ranges between the extremes of cooperation on the one hand and competition on the other hand (for a more detailed conceptualisation see Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021). This dimension is thus essentially about whether the political goals of national parliaments and the EP align (Griglio & Stavridis, Citation2018). On one end of the extreme, cooperation may resemble an interaction where ‘all actors can maximise their payoffs by agreeing on concerted strategies’ (Scharpf, Citation1997, p. 73). In this case one would ideally see national parliaments and the EP develop synergetic relationships that they recognise to work in their mutual interest, like, specifically, the parliamentarisation of EU decision-making. On the other end of the continuum, legislative actors can also be in competition or ‘pure conflict’ (Scharpf, Citation1997, p. 73). Pure conflict is the exact opposite of cooperation as it illustrates a zero-sum-situation where actors perceive or fear distributive consequences of their interaction.

However, this primary dimension is qualified by a second one that considers the intensity of these relations. The intensity dimension is critical because we know that involvement of, particularly, national parliaments in EU affairs remains limited most of the time. If that is the case, then the notions of both cooperation and competition loose much of their rationale. In contrast, cooperation and competition become of much greater significance if both the EP and national parliaments are actively engaged on a topic. In operational terms, by intensity we mean the extent to which actors on both parliamentary levels ‘invest’ time and resources in the vertical relationship – be it in a cooperative or competitive direction. This understanding of intensity does not necessarily reflect institutional factors like the frequency of inter-parliamentary meetings or the presence of an inter-parliamentary forum. It is rather a function of the salience of an EU policy, especially on the side of national parliaments because that is where we expect such salience to be most volatile. Bartolucci et al. (Citation2020) refer to this dimension as the "effectiveness" of inter-parliamentary cooperation, i.e. the degree to which parliamentary actors fulfil the assigned function of a potential cooperation. In order to deliver on cooperation, inter-parliamentary relations require high-intensity activities from both sides, the EP and national parliaments, including attendance, time, and resources invested (Bartolucci et al., Citation2020; Miklin, Citation2013).

Taking these two dimensions of cooperative versus competitive and low-intensive versus high-intensive interaction together, we develop four ideal types of inter-parliamentary relations: (1) co-scrutiny; (2) conflict; (3) low-intensity cooperation; and (4) low-intensity competition ().

The primary divide here is on the intensive side of the panel between the extremes, which we label co-scrutiny and outright conflict. Indeed, over the last ten years, we have regularly seen national parliaments and the EP vying for power. One example is the way that the EP was inclined to push back on any subsidiarity claims that national parliaments raised through the early warning mechanism (Cooper, Citation2013). Another prominent example is the rather intense confrontations between national parliaments and the EP on the rules of procedure for the inter-parliamentary conferences on Common Foreign and Defence Policy (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2014). However, on other occasions – and arguably increasingly so – relations between the parliaments have been rather collegial and mutually supportive. Conceptually speaking, the positive extreme of such cooperation happens when parliamentary actors work on joint positions or strategies through intensive personal as well as institutionalised interaction on a polity or policy level (e.g. Miklin & Crum, Citation2008, p. 6f.; Wonka & Rittberger, Citation2014).

Domains where vertical relations are less intensive seem initially less interesting, certainly when there is little interdependence and parliaments can ignore each other at little cost. Still, the dynamics that we see when relations are less intense and structured may well be quite telling. One reason is that for many (national) parliaments it is tempting to focus mostly on their own national affairs and to downplay any interdependencies occasioned by the EU context. In those situations, it is even more telling what the basic attitude is when such interdependencies come to the fore in the relationship with other parliaments: are parliaments inclined to a defensive or even hostile attitude or are they rather inclined to go along constructively with the inclinations of others? Much hinges here on the basic trust in the other parliaments.

We offer these four modes of vertical parliamentary relations as categories to organise our observations and the dynamics in the different policy domains. As such, they do not prejudge any normative verdict on the quality of these interactions and their contribution to the democratic legitimacy of the EU. Indeed, we want to resist the suggestion that more cooperative and more intense relations are intrinsically to be preferred over more competitive and extensive relations. There certainly is not an inherent virtue in intensity, as maintaining inter-parliamentary relations is costly and diverts from the primary internal business of parliaments. Thus, there is much to be said to aspire to a clear division of tasks between parliaments at different levels, which allows for more low-intensity relationships.

Similarly, in a political context like EU decision-making, it is essential to question the assumption that cooperative relationships are inherently to be preferred over competitive ones. To the contrary, as a polity that spans a broad range of interests and, at the same time, stands accused of a technocratic approach to politics, the EU needs parliaments to insert diverging points of view and to express political cleavages in their deliberations. Ideally, such division lines become articulated in each parliament, but to the extent that parliaments represent different constituencies, with different identities and different claims to autonomy, it is only natural that inter-parliamentary relations take on a more competitive character. Still, these observations should not lead us to the extreme in which conflict is considered inherently desirable. In the end, the overall effect of the mix of cooperation and competition needs to be assessed on the extent that it is conducive to a more inclusive and better-informed decision-making process in the EU overall. When no such effects can be demonstrated and the decision-making process is eventually left brittle and fragmented, there is little reason to applaud competition for being disruptive only.

Explanations

We expect considerable variation across the different domains of EU activity in the forms that inter-parliamentary relations have come to adopt over the last thirteen years (cf. Bolleyer, Citation2010; Strelkov, Citation2015). Yet, we also expect some patterns to emerge from this variation, for instance between areas that are similar in substance or structure (variation across areas) and in the overall direction in which the different forms of vertical legislative relations have been evolving over time (cf. Eppler & Maurer, Citation2017). To understand such patterns, we need to have an idea about the likely factors that drive them.

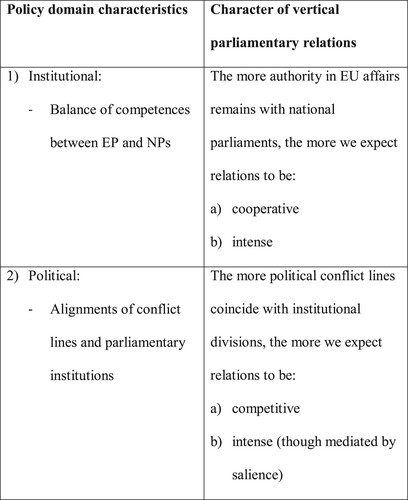

The characteristics of the different policy domains that we expect to drive these variations are either institutional or (party-)political. Firstly, on the institutional side, we expect the character of inter-parliamentary relations to vary in particular with the balance of competences between the EP and the national parliaments (cf. Strelkov, Citation2015). Specifically, we expect that the chances that cooperative relations between the EP and the national parliaments have ensued are higher in policy domains that remain more intergovernmental in character and where, consequently, the EP is forced to recognise the need for some form of coordinated action. In contrast, in policy domains that have become communitarised over time, we expect that the EP has continued to push back on any attempts of involvement by the national parliaments. Based on research on the EP, we can plausibly assume turf battles to occur in cases where it tries to protect its areas of influence (cf. Meissner & McKenzie, Citation2018). Hence, we expect relations to remain more competitive.

Secondly, on the (party-)political side, we expect politicisation to have led to an increase in the importance of the structure of party-political cleavages in EU affairs (see also Senninger, Citation2017). The nature of the main lines of political contestation varies between areas; they may involve the traditional left-right distinction, but also other ideological cleavages (e.g. conservative-progressive or pro-EU versus anti-EU) or indeed coincide with national differences (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009; Winzen et al., Citation2015). We expect these variations to have an impact on the nature of vertical legislative relations. Our focus in this respect is on whether the main political conflict lines coincide with the different institutions or rather run across them.

There are three ways in which political conflict lines can map on the divisions between parliamentary institutions (Crum, Citation2022). The first, along the vertical dimension, is when the political debate is concentrated on the very question whether a certain competence should be exercised at the national or at the supranational level. In that case, it is logical that national parliaments are pitted against the EP (Cooper, Citation2016). Second, along the horizontal dimension, we can find EU issues where conflict lines essentially run between the member states (see also Winzen et al., Citation2015), like the division between creditor versus debtor states in the Eurozone or regional differences between northern or southern, or western and eastern, member states (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019). In the third scenario, there may also be EU issues where the main political conflict lines run transnationally across the parliamentary institutions. Typically, these are conflicts that can be framed in ideological terms that correspond to the classical left-right scheme and the different party-groups that dominate the European political arena. Next to the classical left-right scheme, such differences may also occur in the divide between government and opposition (Miklin, Citation2013) or between culturally liberal and culturally conservative political groups (Winzen et al., Citation2015).

The direction of the effect that this factor is expected to have on the cooperative character of vertical parliamentary relations may be obvious: we expect vertical inter-parliamentary relations to remain more conflictual in those domains where the main lines of political conflict coincide with institutional divisions and to be more cooperative in domains where the main political division lines run across parliaments. In addition, we expect the intensity of vertical inter-parliamentary relations to be greater in policy domains where the main political divisions run across parliaments. In this respect the degree to which the EU domain has become salient (politicised) can be expected to be a contributory factor ().

Empirical patterns

When we consider recent empirical research on parliamentary relations in the EU through the lens of our framework, low-intensity cooperation appears to be the most prevalent form that inter-parliamentary relations have come to adopt in the post-Lisbon EU. Typically, in almost all areas under scrutiny, we find some form of low-intensity exchange of information between parliaments. These relations are pragmatic and display little sign of inter-parliamentary hostility. Low-intensity cooperation by way of exchanging information or debating policy issues stretches across communitarised areas of EU decision-making such as trade (Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021) or AFSJ (Tacea & Trauner, Citation2021), but also the new and less established fields like Brexit affairs (Högenauer, Citation2021) or CFSP (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022).

Indeed, several of the cases suggest that relations between national parliaments and the EP have become institutionalised over time and that, once the rules for these institutions have beenagreed, they have tended to become rather pragmatic and cooperative. Herranz-Surrallés (Citation2022) shows how inter-parliamentary relations in the domain of CFSP have evolved from an "unsettled" to a "settled" policy field. These dynamics can be read as a sign of institutional consolidation whereby the EP and national parliaments have come to develop a consensual practice of vertical legislative relations since the Lisbon Treaty. Similar trends can be observed in the organisation of inter-parliamentary coordination in economic governance (Kreilinger, Citation2018) as well as in joint legislative scrutiny and agency oversight in the AFSJ (Tacea & Trauner, Citation2021). In this vein Crum (Citation2022) also concludes that inter-parliamentary relations have matured into a certain level of institutionalisation when it concerns EU legislation and inter-parliamentary conferences.

Notably, in all the domains in which inter-parliamentary relations have come to be institutionalised (to a lesser or greater degree), it is found that the inter-parliamentary institutions tend to be dominated by EP actors. This is observed for the inter-parliamentary conferences on economic governance (Kreilinger, Citation2018) and on foreign policy (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022). It also applies to the coordination of legislative scrutiny in the AFSJ (Tacea & Trauner, Citation2021). The EP emerges as the one parliament that has an overview of the EU level process, while the national parliaments often remain uncoordinated both in terms of their processes as well as in the substantial positions they adopt. That difference is also clearly apparent in a very intergovernmental and under-institutionalised issue like Brexit (Högenauer, Citation2021). Thus, inter-parliamentary institutions may actually amplify the advantages that the EP holds in terms of information, position, and resources, rather than that they serve as arenas for the political engagement between parliaments on an equal standing.

While low-intensity cooperation emerges as an empirical default, it is particularly the exceptions that call for further analysis. Notably, signs of somewhat higher intensity are typically encountered in domains that are neither fully communitarised (like legislative scrutiny in AFSJ) or remain fully intergovernmental (like the Brexit negotiations), but where the interdependence between the two levels is most pronounced, like in trade, joint scrutiny of Europol and economic governance. Still, the institutionalisation of inter-parliamentary relations that has occurred in these domains appears to have dampened some of the higher levels of intensity that were witnessed in the early 2010s around the euro crisis (Auel & Höing, Citation2015; Closa & Maatsch, Citation2014) and in the domain of CFSP (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2014). A notable case is the involvement of national parliaments in the Recovery and Resilience Facility, which mostly remained limited to the national level and where their involvement at the EU-level has been negligible (Dias Pinheiro & Dias, Citation2022).

These findings suggest that the intensity of parliamentary interactions is not a linear function of the level of integration (less integration increases intensity) but that this relationship is rather curvilinear or a function of the level of interdependence: intensity becomes most likely in those cases where national parliaments and the EP need each other most. Also in terms of the structure of political conflict there is little evidence so far that intensity increases when conflict lines coincide with institutional divisions. Instead, intensity seems to closely track salience in domains like economic governance and trade.

There is more variation along the cooperation–competition dimension, even if it often remains rather episodic. The ‘negative’ exceptions, where inter-parliamentary relations are marked by outright conflict, were expected in policy domains that have already become rather Europeanised and where the main political cleavages run between the different parliaments. The empirics of post-Lisbon inter-parliamentary relations reveal few cases of outright conflict among EU parliaments. Conflict between parliaments, especially in the Europeanised areas of decision-making, seems to be hampered by a lack of engagement of national parliaments in EU affairs.

While we have no examples of outright conflict, the examples of parliamentary competition that the case studies find are more likely to involve institutional divisions and parliamentary competences. In trade policy, for example, Meissner and Rosén (Citation2021) detect two parallel, distinct levels of vertical relations between the EP and parliaments in Austria, Germany, and Sweden. On a partisan level, the party groups turn primarily to a little intense exchange of documents or information in the context of trade negotiations. On an institutional level, however, the Austrian Nationalrat and German Bundestag also engaged in measures to substantiate their competence claims in the EU trade negotiations with Canada and the United States. Such measures can be understood as a competitive relationship albeit little intense.

On the other extreme of the cooperation–competition dimension, we expected ‘positive’ exceptions, where distinctively cooperative and productive relations issue into co-scrutiny, to be most likely in those EU domains where national parliaments retain much of their traditional authority and where the main political cleavage lines run across the different parliaments. These expectations are again challenged by the case studies since the signs of co-scrutiny that we encounter concern those EU areas that are strongly communitarised: trade policy and AFSJ. In EU trade negotiations, the Green party-political groups emerged as a champion of inter-parliamentary cooperation. More specifically, the Austrian and German Greens coordinated joint strategies, organised events, and set up common communications together with their counterpart in the EP in order to scrutinise trade talks. In the case of AFSJ, we find the Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group (JPSG) as an example of co-scrutiny activities of Europol. This might be an obvious example to the reader given that co-scrutiny is even foreseen in the Lisbon Treaty. Tacea and Trauner (Citation2021) provide a more nuanced perspective on how the EP’s LIBE Committee exercises primarily ‘individual oversight’, but the joint co-scrutiny with national parliaments from EU member states adds an additional layer to holding Europol to account.

In contrast, Herranz-Surrallés (Citation2022) finds in her empirical investigation into the Interparliamentary Conference on CFSP/CSDP and the European Defense Fund that, even if relations between the EP-national parliaments have become increasingly settled over recent years, they have not evolved into a fully-fledged co-scrutiny of executive actors. A considerable hindrance to co-scrutiny appears to be the parliamentarians’ subjective understanding of domestic constituencies and sovereignty (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022). Still, it was the EP’s moderation of its own ambition in foreign and security affairs that allowed parliamentary interactions in the CFSP to become more settled (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2022).

The evidence that emerges from the case studies suggests the dynamics in parliamentary interactions in the EU to be both less and more complex than we theorised in the preceding sections. On the one hand, variation is limited as most parliamentary interactions, across all policy domains, remain marked by (very) low intensity and tend to be rather pragmatic and cooperative. However, whenever parliamentary interactions do become more intense, like in trade or in economic governance, interaction patterns may actually go both ways; they can become both more competitive as well as more cooperative. In the complex political context of the EU, in which parliaments do not only have to reckon with each other but also with other executive and administrative institutions (like the governments, the Council, the Commission, and EU agencies), these dynamics may well co-exist or parliaments may oscillate between them. What is more, the dynamics involved can only be captured if parliaments are recognised to be composite rather than unitary actors in which different strategies can be adopted by institutional representatives, political groups, and individual MEPs.

Conclusion

At the outset of this article, we aimed to explore how the relations between the EP and national parliaments have shaped up in the post-Lisbon EU multi-level governance system. To this end, we developed a conceptualisation of inter-parliamentary relations along two dimensions: cooperation and competition as well as high and little intensity (). We expected the institutional characteristics of policy domains and the nature of conflict lines to structure the form of inter-parliamentary relations into this conceptualisation, ranging from co-scrutiny, via low-intensive cooperation and low-intense competition, to outright conflict. By relying on the empirical results of recent case studies we reviewed, we then applied this framework to a set of communitarised EU decision-making areas as well as new, intergovernmental domains such as Brexit or CFSP.

We find that inter-parliamentary relations have become increasingly institutionalised and settled in the post-Lisbon EU. Tensions between the EP and national parliaments have eased in favour of low-intensive cooperation. In fact, little intense cooperation emerges as the empirical default of inter-parliamentary relations across all policy domains under scrutiny: parliamentary actors from EU member states have found fruitful ways to exchange documents and information with their counterparts in the EP. Yet, low-intensity competition accompanies these patterns of cooperation. An example arises in the area of trade policy where the transnational partisan relations live up to cooperative exchange, while the institutional relations between the EP and national parliaments are marked by competing competence claims (Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021).

In our review, we find few instances on the extremes of inter-parliamentary cooperation. Somewhat in contrast to our theoretical expectation, co-scrutiny seems to happen mostly in the communitarised areas of EU decision-making. An example of co-scrutiny is how members across parliaments hold executive actors to account in the negotiation of trade agreements (Meissner & Rosén, Citation2021). Still, in the policy domains where national parliaments are in the driver’s seat – and where we would have expected an ambition by the EP to strive for co-scrutiny – we find a gradual settlement of inter-parliamentary relations to the benefit of more cooperation. It is remarkable that we encounter almost no ‘negative’ cases of outright conflict.

On the whole, the review of the recent case studies suggests that to analyse greater variation we need to unpack EU parliamentary interactions more systematically. Intensity, cooperation, and competition are not structural characteristics of policy domains but rather reflect different episodes. At the same time, to understand these dynamics, also parliaments must be unpacked and to be recognised as the composite actors that they are in which institutional representatives, party groups, and individual MEPs may operate in different directions.

Clearly, the parallel engagement of national parliaments and the EP in EU affairs has become much more visible in the decade since the Treaty of Lisbon. After some initial clashes, particularly around the establishment of the various interparliamentary conferences, relations have become more pragmatic. Some institutionalisation and settlement of relations between the two levels of parliaments has taken place. Still, parliamentarians tend to operate within their own confines and, overall, coordination tends to remain rather low-key. In that sense, whatever ‘multilevel parliamentary field’ is taking shape in the EU, it remains very loosely integrated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katharina L. Meissner

Katharina Meissner obtained her PhD in Political and Social Sciences from the European University Institute (EUI), Florence, Italy. In 2016, she joined the Centre for European Integration Research (EIF), Department of Political Science, University of Vienna. She is Lise-Meitner postdoc and project leader (FWF M-2573).

Ben Crum

Ben Crum is Professor of Political Science at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His research focuses on questions of democratic theory and institutional change in the European Union.

References

- Auel, K., & Höing, O. (2015). National parliaments and the Eurozone crisis: Taking ownership in difficult times? West European Politics, 38(2), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990694

- Auel, K., & Neuhold, C. (2016). Multi-arena players in the making? Conceptualizing the role of national parliaments since the Lisbon Treaty. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(10), 1547–1561. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1228694

- Auel, K., Rozenberg, O., & Tacea, A. (2015). To scrutinise or not to scrutinise? Explaining variation in EU-related activities in national parliament. West European Politics, 38(2), 282–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990695

- Bartolucci, L., Fasone, C., Lupo, N., Kelbel, C., & Navarro, J. (2020). Representativeness and effectiveness? MPs and MEPs from opposition parties in inter-parliamentary cooperation, Working Paper on Interinstitutional Relations in the EU, Lille.

- Bellamy, R., & Kröger, S. (2016). Beyond constraining dissensus? The role of national parliaments in politicizing European integration. Comparative European Politics, 14(2), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.39

- Bolleyer, N. (2010). Why legislatures organise: Inter-parliamentary activism in federal systems and its consequences. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 16(4), 411–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2010.519454

- Closa, C., & Maatsch, A. (2014). In a spirit of solidarity? Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(4), 826–842. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12119

- Cooper, I. (2012). A ‘virtual third chamber’ for the European Union? National parliaments after the Lisbon Treaty. West European Politics, 35(3), 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665735

- Cooper, I. (2013). Bicameral or tricameral? National parliaments and representative democracy in the European Union. Journal of European Integration, 35(5), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.799939

- Cooper, I. (2016). The politicization of inter-parliamentary relations in the EU: Constructing and contesting the ‘Article 13 Conference’ on economic governance. Comparative European Politics, 14(2), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.37

- Cooper, I. (2019). National parliaments in the democratic politics of the EU: The subsidiarity early warning mechanism, 2009–2017. Comparative European Politics, 17(6), 919–939. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-018-0137-y

- Crum, B. (2022). Patterns of contestation across EU parliaments: Four modes of inter-parliamentary relations compared. West European Politics, 45(2), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1848137

- Crum, B., & Fossum, J. E. (2009). The multilevel parliamentary field: A framework for theorizing representative democracy in the EU. European Political Science Review, 1(2), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773909000186

- Crum, B., & Fossum, J. E. (2013). Practices of inter-parliamentary coordination in international politics. The European Union and beyond. ECPR Press.

- Dias Pinheiro, B., & Dias, C. S. (2022). Parliaments’ involvement in the recovery and resilience facility. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 28(3), 332–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2022.2116892

- Eppler, A., & Maurer, A. (2017). Parliamentary scrutiny as a function of interparliamentary cooperation among subnational parliaments. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23(2), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2017.1329989

- Finke, D., & Dannwolf, T. (2013). Domestic scrutiny of European Union politics: Between whistle blowing and opposition control’. European Journal of Political Research, 52(6), 715–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12014

- Fromage, D. (2016). Increasing inter-parliamentary cooperation in the European Union: Current trends and challenges. European Public Law, 22(4), 749–772. https://doi.org/10.54648/EURO2016043

- Fromage, D., & Herranz-Surrallés, A. (Eds.). (2021). Executive-legislative (im)balance in the European Union. Hart Publishing.

- Griglio, E., & Stavridis, S. (2018). Inter-parliamentary cooperation as a means of reinforcing joint scrutiny in the EU: Upgrading existing mechanisms and creating new ones. Perspectives on Federalism, 10(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2478/pof-2018-0031

- Hefftler, C., & Gattermann, K. (2015). Interparliamentary cooperation in the European Union: Patterns, problems and potential. In C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg, & J. Smith (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of national parliaments and the European Union (pp. 94–115). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Héritier, A., Meissner, K. L., Moury, C., & Schoeller, M. G. (2019). EP ascendant: Parliamentary strategies of self-empowerment in the EU. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Herranz-Surrallés, A. (2014). ‘The EU’s multilevel parliamentary (battle)field: Inter-parliamentary cooperation and conflict in foreign and security policy’. West European Politics, 37(5), 957–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.884755

- Herranz-Surrallés, A. (2022). Settling it on the multi-level parliamentary field? A fields approach to interparliamentary cooperation in foreign and security policy. West European Politics, 45(2), 262–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1858609

- Högenauer, A.-L. (2021). Parliamentary scrutiny of Brexit in the EU-27. International Journal of Parliamentary Studies, 1(2), 270–290. https://doi.org/10.1163/26668912-bja10024

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Huff, A. (2015). Executive privilege reaffirmed? Parliamentary scrutiny in the CFSP and CSDP. West European Politics, 38(2), 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990697

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 996–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619801

- Kreilinger, V. (2018). From procedural disagreements to joint scrutiny? The interparliamentary conference on stability, economic coordination and governance. Perspectives on Federalism, 10(3), 155–183. https://doi.org/10.2478/pof-2018-0035

- Lupo, N., & Fasone, C. (Eds.). (2016). Inter-parliamentary cooperation in the Composite European Constitution. Hart Publishing.

- Meissner, K. L., & McKenzie, L. (2018). The paradox of human rights conditionality in EU trade policy: When strategic interests drive policy outcomes. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(9), 1273–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1526203

- Meissner, K. L., & Rosén, G. (2021). Who teams up with the European Parliament? Examining multilevel party cooperation in the European Union. Government and Opposition, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.52

- Miklin, E. (2013). Inter-parliamentary cooperation in EU affairs and the Austrian parliament: Empowering the opposition? The Journal of Legislative Studies, 19(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2013.736785

- Miklin, E., & Crum, B. (2008). Inter-parliamentary contacts of members of the EP: Report of a survey. RECON Online Working Paper 2011/08. Oslo.

- Neuhold, C., & Rosén, G. (2019). Introduction to Out of the Shadows, into the Limelight: Parliaments and politicisation. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2443

- Peters, D., Wagner, W., & Deitelhoff, N. (2010). Parliaments and European security policy: Mapping the parliamentary field. European Integration Online Papers, 1(14), 1–25.

- Rauh, C. (2019). EU politicization and policy initiatives of the European Commission: The case of consumer policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(3), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1453528

- Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Games real actors play. Westview.

- Senninger, R. (2017). Political parties and parliamentary oversight [PhD thesis, Forlaget Politica].

- Senninger, R. (2019). Institutional change in parliament through cross-border partisan emulation. West European Politics, 43(1), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1578095

- Strelkov, A. (2015). Who controls national EU scrutiny? Parliamentary party groups, committees and administrations. West European Politics, 38(2), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990699

- Tacea, A., & Trauner, F. (2021). The European and national parliaments in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice: Does interparliamentary cooperation lead to joint oversight? The Journal of Legislative Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2021.2015559

- Winzen, T. (2012). National parliamentary control of European Union Affairs: A cross-national and longitudinal comparison. West European Politics, 35(3), 657–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665745

- Winzen, T. (2022). The institutional position of national parliaments in the European Union: Developments, explanations, effects. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(6), 994–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1898663

- Winzen, T., Roederer-Rynning, C., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2015). Parliamentary co-evolution: National parliamentary reactions to the empowerment of the EP. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.881415

- Wonka, A., & Rittberger, B. (2014). The ties that bind? Intra-party information exchanges of German MPs in EU multi-level politics. West European Politics, 37(3), 624–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.830472

- Wouters, J., & Raube, K. (2012). Seeking CSDP accountability through interparliamentary scrutiny. The International Spectator, 47(4), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2012.733219

- Zeitlin, J., Nicoli, F., & Laffan, B. (2019). Introduction: The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicization in an age of shifting cleavages. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 963–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619803