ABSTRACT

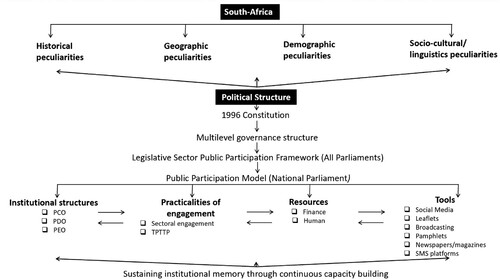

Previous research and observed practices demonstrate that as hubs of public participation in governance, parliaments are devising means and prioritising resources that promote more public-facing initiatives to reach out to different segments of society. The diverse means through which these happen, across contexts, pose the ‘danger’ of randomness and spontaneity which ultimately limits institutional memory and consistency. This article explores how parliaments can enhance content and outcomes through the institutionalisation of public engagement. It demonstrates how legal and institutional frameworks – as a system of rules and formalised standards – are combined to set clearly defined templates, and how these align with processes for enhanced public engagement practices. In using South Africa to frame its analysis, the article draws on the 2022 IPU-UNDP Global Parliamentary Report interviews and document analysis of relevant frameworks and reports. We show how leveraging historical, geographic, social-linguistics, and demographic contexts help to strengthen parliament-public interface through institutionalisation.

Introduction

The ideals of participatory democracy underscore the need for people to be involved in the decisions that affect them, as a demonstration of their civic rights. However, democratic institutions have increasingly become fragile because of rising distrust in public officials. For instance, Perry’s (Citation2021, p. 2) analysis of opinion surveys across countries conducted by Afrobarometer, Eurobarometer and Latinobarometer showed how public trust in governments ‘peaked at 46 per cent, on average, in 2006 and fell to 36 per cent by 2019.’ A likely explanation for this would be the increasing demand for citizen-centric public service delivery and policy focus by the governed (Steiner & Kaiser, Citation2017), and the perceived below-par performance of governments in meeting up with the expectations of an increasingly more aware citizens (Bertsou, Citation2019). Despite the constraints, the normative expectations of democratic governance are still that citizens are involved in the matters that affect their existence, and perhaps their very survival. This constitutes the centrepoint of public engagement with democratic institutions, of which the parliament is a core element. This article is about public engagement design and its implementation in the works of parliaments.

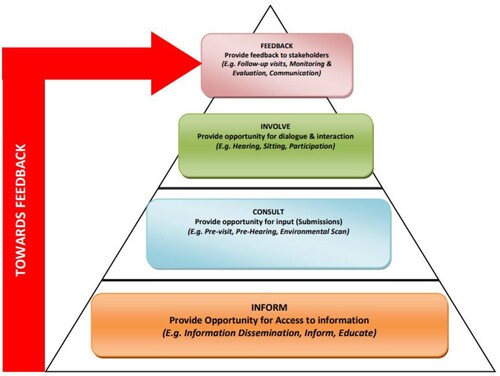

While a plethora of definitions are commonplace for public engagement, it particularly aims at allowing the people to participate in the decision-making processes regarding policies and administration or governance, as a way of ‘empowering [them] in relation to their surroundings’ (Leston-Bandeira, Citation2022, p. 11). It has also been explained in terms of a series of activities or stages, as ‘informing or consulting citizens to involving them, collaborating with them or truly empowering them or even reimbursing them for participating in the policy and decision-making processes’ (Steiner & Kaiser, Citation2017, p. 169). Prior research established that public engagement has the potential to serve the general good. Beyond the legitimacy it confers on leaders, it leads to better decisions and more efficient outcomes (Steiner & Kaiser, Citation2017), increases trust and positive perceptions of public institutions (Clark & Wilford, Citation2012), and, to quote OECD (Citation2009, p. 21), can help to ‘better understand people’s needs, leverage a wider pool of information and resources, improve compliance, contain costs and reduce the risk of conflict and delays downstream.’ To optimise these benefits, Lee and Levine (Citation2016, p. 43) emphasised the need for the public and officials to jointly seek the three aspects of public engagement: ‘communicating about issues of shared concern (deliberation), working together to address those issues (collaboration), and forging effective and enduring relationships (connection).’

Public engagement is particularly crucial for parliaments as politico-democratic institutions, being hubs of public participation in governance. That parliaments represent the face of the public in governance reinforces that the quality of their law-making, oversight and representative functions should be anchored in frameworks that are responsive to citizens’ demands, devote substantial resources to ‘promote ‘‘outreach’’ and direct citizen influence in policymaking’ (Arnold, Citation2012, p. 442). Growing empirical evidence suggests that public engagement is thus becoming a ‘large component of parliamentary policy’ (Prior, Citation2019, p. 29), towards strengthening connections with different segments of the society and increasing the breadth and depth of ideas needed for effectiveness in the work of legislatures (IPU & UNDP, Citation2022; Leston-Bandeira, Citation2012; Odeyemi & Abati, Citation2021). As the IPU and UNDP (Citation2022) have importantly established, legislative public engagement happens mainly in interrelated and interconnected ways through which legislatures inform and educate the public about their roles and significance; communicate with external actors about their activities; and promote public consultation and participation in their processes.

The very diverse means through which public engagement activities happen across parliamentary contexts pose the ‘danger’ of randomness and spontaneity, which, in turn, limit institutional memory and consistency. There is therefore the need to explore ideas of institutionalising public engagement as a core activity. Here, institutionalisation would mean the process through which legal and institutional frameworks are deliberately combined to set clearly defined templates, and monitoring mechanisms are devised to ensure effective engagement of all stakeholders in parliamentary practices. Institutionalisation relies on frameworks – the system of rules and formalised standards that guide public engagement; and the article’s analysis dissects the functionality of such frameworks in ensuring the effective engagement of all stakeholders in parliamentary activities and practices. It focuses on South Africa, described by Barkan (Citation2009, p. 21) as one of the contexts ‘that have advanced the farthest with respect to democratisation in Africa.’ The article draws on different sources, notably the IPU-UNDP Global Parliamentary Report interviews, focus group discussion sessions and analysis of public engagement, as well as document analysis of relevant frameworks and reports. The discussion demonstrates the importance of leveraging historical, geographic, social-linguistics and demographic contexts to strengthen parliament-public interface through institutionalisation.

Conceptualising institutionalisation in the works of democratic institutions

The article proceeds by conceptualising institutionalisation of public engagement in order to converge the various thoughts on what it implies in the works of democratic institutions. We synthesise these different perspectives to arrive at what defines institutionalisation, towards forming the basis of understanding. Institutionalisation is a concept that cuts across the disciplines of social and political sciences. As a sociological concept, it captures embedded societal and organisational norms, behaviours, beliefs and roles, while as a political science concept, it implies creating and organising systems, institutions and bodies to oversee or execute decisions (Keman, Citation2017).

Institutionalisation has also been conceptualised as a process, a goal, and from legal and cultural perspectives. As a process, it is understood as the continuous ‘transformation by which institutions are (re)produced in interactions’, where institutions act as ‘semi-autonomous social agents’ (Tatenhove & Leroy, Citation2000, p. 18). It involves ongoing process of forming, preserving, creating, organising and deconstructing everyday activities and interactions of institutions (Tatenhove & Leroy, Citation2000). To use the words of Ledesma-Gumasing and Zimmermann (Citation2020, p. 208), it aims at ‘achieve[ing] a structure, sets of norms, rules and regulations of expected behaviour.’ It is a procedure of institutional or organisational acquisition of ‘value and stability,’ achieved through the investment activities of ‘actors’ over time, which leads to the ‘increased formalisation of some practices, and increased structure, all of which increase internal capabilities’ (Palanza et al., Citation2016, p. 9).

As a goal, institutionalisation represents the formalisation of a new activity as part of the norm of the organisation – when activities become ‘standard practice’ (Lukensmeyer, Citation2009, p. 232) – with impact on structures, processes, or behaviours of the constituted units. From its legal dimension, institutionalisation is seen as the integration of deliberative actions in the public decision-making structural codes in a legal constitution in order to institute a basic legal-regulatory framework to ensure continuity even in a situation of political change (OECD, Citation2020). The cultural perspective implies the maintained, sanctionable, regulated and recurrent processes that ensure the alignment of new institutions with societal values (OECD, Citation2020). It is the procedure through which ‘the contents and the organisation of policy arrangements are (re)produced in interaction, within the context of long-term processes of societal and political change’ (Tatenhove & Leroy, Citation2000, p. 19). To quote Palanza et al. (Citation2016, p. 8), it is the pathways by which ‘social roles, particular values and norms, or modes of behaviour become embedded within organisations, social systems, or societies as established customs or norms.’ This conception views institutionalisation as targeted at ensuring standardisation of norms, roles, and behaviours to suit existing systems, structures, and institutions.

In synthesising the various conceptions, institutionalisation is interpreted as the formalisation and entrenchment in a recognised framework, of a series of actions as the organisational norm. While this is often a ‘long-term process’ (Martinez, Citation2018, p. 66) that may be time demanding (Opalo, Citation2015), the need to institutionalise processes remains imperative, as the functioning of institutions are metrics to gauge the effectiveness of a political system (Dri, Citation2009). As Palanza et al.’s (Citation2016) comparative study found, deeper levels of legislative institutionalisation enhance human development and quality of public policies. In particular, institutionalisation is key to sustaining public engagement measures, enhancing participatory processes, and strengthening legitimacy (Landry & Angeles, Citation2011; Ravazzi, Citation2016, p. 81). Well-articulated institutionalisation would imply that contexts, processes, norms and goals are synthesised such that historical and political peculiarities are reflected in the parliament’s public engagement practices with the aim of continuously adapting towards good practices.

The institutionalisation of public engagement activities in the work of democratic institutions constitutes some challenges (Davidson & Stark, Citation2011). At the minimum, the process may be time consuming due to the need for the creation of a ‘host of formal policies and institutions,’ and the need for a shift in cultures and the creation of informal organisations, which may be difficult to attain in the face of rigidity (Lukensmeyer, Citation2009, p. 232). This elicits further reactions in the literature about the risk of excessive formalisation and ‘ritualization’ of practices that institutionalisation poses (Ravazzi, Citation2016, p. 3). Indeed, the willingness or otherwise of actors to commit to the evolution of an institutionalised process could threaten or strengthen the development of institutionalisation in parliaments (Palanza et al., Citation2016). To optimise output, therefore, is the need for a well-knitted connection between the institution and its public. The next section begins the case illustration, with a discussion of how a legislature entrenches its public engagement.

Constitutional entrenchment of public engagement: The South African case

The process of public engagement in South Africa is preceded by a historical trajectory of exclusion. The country’s era of apartheid was characterised by widespread segregation and discrimination against non-white citizens. These were translated into formal laws and policies that heightened national division; the divisions became more pronounced with the ascension of, and wielding of political power by, the National Party in 1948. One of such formal documentations of segregation was the classification of South Africans by race in The Population Registration Act of 1950 which described citizens as Bantu (black Africans), coloured (mixed race), whites, and Asian (Indian and Pakistani) (Posel, Citation2001). Segregation influenced the structures of political institutions and nature of political representation. For instance, in 1983, the institutions of parliament were tricameral in nature, such that the Whites, Coloured and Indian/Asian elected members of the House of Assembly, House of Representatives and House of Delegates, respectively, yet, with the exclusion of the Black population.

The journey towards inclusion dates to the 1990s. The Interim Constitution ushering in the new era served as the legal framework for inclusion, and subsequently set the precedence for the 1996 Constitution and its emphasis on the core elements of participatory democracy. The drafting of the 1996 Constitution incorporated wider civil society inputs in a precedence that became standard practice for public engagement in parliament (Madue, Citation2012; Odeyemi & Abioro, Citation2019; Scott, Citation2009). The Constitution in sections 59 and 72 instituted a bicameral legislature at the national level: National Assembly (NA) and the National Council of Provinces (NCOP), collectively named the Parliament of the Republic of South Africa (PRSA). Section 104 further establishes a unicameral legislature for the 9 provinces. At the different levels, the Constitution mandates public participation in the processes of parliament, and its committees at all times, except, in the case of the latter, if ‘it is reasonable and justifiable to [exclude the public and the media] in an open and democratic society’ (RSA, Citation1996, section 59[2]). This institutionalised practice extends to societal activities as the Constitution duly recognises 11 official languages, including a mandate to ensure a response to the needs of the public and their facilitation into the decision-making process (RSA, 1996, section 195[1][e]).

Parliaments at the three levels of government (national, provincial and municipal) actively position themselves as the voice of the public in fulfilling their constitutional mandate, and entrenching public engagement helps to position them as ‘the nerve-centre of people’s power, people’s participation and people-centred governance’ (PRSA, Citation2019, p. 19). As an official of the National Parliament mentioned, ‘everyone, irrespective of race, irrespective of age, irrespective of where you live, […] feel that they are part of this democracy because there are deliberate efforts to involve them’.Footnote1 This is to the extent of erasing the limitations of apartheid where legislative institutions functioned to ‘oppress people [and] to disenfranchise people’.Footnote2 In the democratic era, the functioning of the Parliament is aimed at serving ‘[…] as a vehicle where the aspirations of our people can be expressed and where they can have a direct say in their future and in their destiny’ and as a platform for the public to express their displeasures.Footnote3

Constitution provisions have particularly helped for public engagement institutionalisation – further broken down as frameworks and legislations – in South Africa. This is evident, as Scott (Citation2009) showed, in the manner of vertical accountability of the legislature to citizens, thereby enabling a citizen-responsive policy process. Non-adherence to such provisions allows situations where ‘people can go to court and prove this decision was done, that this law was passed without public participation and the court will not hesitate to declare it unconstitutional’.Footnote4 Constitutional entrenchment thus has prospects of reducing arbitrariness in practice, as perceptible in other African climes. For example, the Constitution of Kenya in Articles 118 and 196 also emplaces public participation as crucial, and mandates the country’s legislatures to ‘ensure that members of the public are engaged in parliament, as public participation is a core value of governance’.Footnote5 However, although engagement ‘has been mainstreamed into legislative process’Footnote6, the absence of a clear legislation to prescribe how this happens in practice – or to give more impetus to it – limits effectiveness and creates ‘the conditions for duty bearers to conduct consultations as a formality’ (Birgen & Okoth, Citation2020). This leaves significant substance gaps, as corroborated in the view of an NGO official that advertisements of engagement activities are often late, so members of the public are ‘not able to engage meaningfully.’Footnote7

As a fallout of the perceived mere formality nature of engagement in Kenya where constitutional provisions are not connected with further legislations, frameworks and institutional provisioning, public inputs into public engagement activities are subjected to what a participantFootnote8 calls predetermined outcome: ‘most of the time, they [parliament] go there with a predetermined outcome. When you have this predetermined outcome, it really doesn't matter what members of the public say or do not.’Footnote9 Thus, to eradicate the dangers of mere formality, ‘civil society organisations and other relevant stakeholders [are] pushing for the establishment of the public participation legislation’ that would ensure that public participation is meaningful, and not just formal.Footnote10 In sum, the South African Parliament thus represents a case of good practices mainly in terms of how institutional practices, including legislation, build on constitutional provisions to establish continuity and uniformity of practice. Subsequent sections explore the development of the institutionalisation processes including the various avenues, structures, platforms, and resources invested in the process.

Good practices: legal frameworks of public engagement

The presence of frameworks is important for building effective collaborations, knowledge sharing, and facilitating a consistent approach in programming and service delivery (Aurbach et al., Citation2019). Here, deliberate strategies and guidelines for public engagement are key to the effective facilitation of public involvement in governance. South Africa provides human and financial resources dedicated to ensuring the implementation of various engagement frameworks for legislatures. Like the Kenyan case, beyond prescribing public engagement, the Constitution does not clearly indicate the manner of approach in practice, thus forming the basis for legal contestations between the citizens and Parliament as regards adequacy of engagement initiatives. This was resolved by the judiciary: the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled that what counts as sufficient engagement are actions geared towards ensuring that the public has been given ‘reasonable opportunity’ for effective participation in legislative activities (Waterhouse, Citation2015). Instructively, this ‘[…] means taking steps to ensure that the public participates in the legislative process’ (PRSA, Citation2017, p. 22).

The Legislative Sector Public Participation Framework (LSPPF), created by the South African Legislative Sector (SALS), constitutes the overarching framework for public engagement (SALS, Citation2013). The SALS, comprising the leaders of the national and nine provincial legislatures, created the framework as a standard for legislatures to establish and institute norms and mechanisms for public involvement in their core processes (PRSA, Citation2017). The framework also exists as ‘a documented platform for shared understanding, alignment and minimum requirements and guidelines for Public Participation’ (PRSA, Citation2017) for the legislatures. The SALS ensures the coordination of standards and peer review mechanisms for public engagement practices, and implementation is monitored by the Legislative Sector Support (LSS), which is the ‘secretariat’ developed within the parliament by the ‘Speakers’ Forum’.Footnote11 These monitoring and evaluation are done on a quarterly basis by the speakers of the legislative institutions to ‘assess how they are doing in their work, implementing this facilitation of public involvement in the processes of [the] legislature’.Footnote12

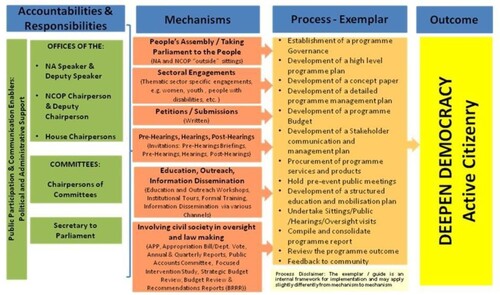

Drawing on the LSPPF, the National Parliament utilises its own Public Participation Model (PPM) as a framework to articulate how human and material resources are devoted towards optimising public input (see below). This ensures the design of the ‘public participation process in such a way that it is inclusive so that the voices of the people [are represented].Footnote13 The PPM delineates the ‘mechanisms and processes through which Parliament can provide for meaningful public involvement and participation in its legislative and other processes’ (PRSA, Citation2019, p. 53). It aims at aiding better communication and support to ‘public education, information provision, and public access to Parliament’s processes in striving to increase the involvement of people from across the socio-economic and geographic profiles of the country’ (PRSA, Citation2019, p. 53).

In living up to the constitutional mandate, in creating the PPM, the Parliament facilitated public contributions through various means, including the use of questionnaires and focus group discussion sessions (PRSA, Citation2017). As shown in the , the PPM cuts across phases intended to Inform (provide opportunity for access to Information), Consult (provide opportunity for input), Involve (provide opportunity for dialogue and interaction) and Feedback (provide feedback to stakeholders). It fosters accountability with the presence of the feedback loop in the public engagement process, and this is also embedded in the oversight functions of parliamentary committees. The prioritisation of public input is likewise evident in the different parliamentary strategy papers and reports discussing the programmes, achievements and challenges of successive parliamentary tenures (PRSA, Citation2014, Citation2015).

The frameworks, models and processes for public engagement are supported through financial and non-financial resource provision including the training and retraining of parliamentary staff. The institution provides resources for ‘[…] all of these steps individually so that they are very effective.’Footnote14 In addition, funding is allocated through committee budgets ‘to ensure that this vital aspect of law-making and engagement with the citizens is not neglected’.Footnote15 Planning is done in ways that ensure an ‘increase in the amount of money that is allocated to public participation, not only in terms of the money’ but also ‘the human resources and the restructuring of internal processes so that we [parliament] can give full expression to the will of the people’.Footnote16 Institutionalisation also extends to a defined regime of capacity building for key actors, including MPs, in order to ensure adequate transfer of knowledge and sharing of norms and practices, as an MP explained:

After each election […] it is important that you bring new members very quickly on board in terms of the modus operandi of public participation and why it is important. You must have dedicated training sessions for members of parliament, where you can also bring in certain elements of civil society, but also former members of parliament who can come and share their experiences with the new members of parliament so that they can pick up the baton and further improve on what we are doing.Footnote17

Channels and structures for engagement

Institutionalisation extends to the creation and activities of structures with tasks related to different elements of the frameworks: these include the Parliamentary Constituency Office (PCO), the Parliamentary Democracy Office (PDO) and the Parliamentary Education Office (PEO) (see ). These structures particularly draw on the peculiarity of the South African electoral system, which reflects the closed party list proportional representation system. As MPs are not directly elected from specific constituencies, the PCOs, for instance, serve as a means of fostering MP-citizen interaction in the constituencies: ‘political parties allocate constituencies to the different members of parliament that are there, which is broadly aligned to the municipal demarcations’.Footnote18 This allows ‘[MPs to] know exactly where [their] operations are and what [they] can do there’.Footnote19 Thus, MP-public interaction is of great importance, and as a matter of fact, ‘absolutely priceless’.Footnote20

The PCOs are run with monthly allowances provided to political parties who in turn make administrative arrangements for how the offices are run. Significantly, PCOs act as ‘an office for the public that is funded by Parliament’.Footnote21 They serve as a means of communication about, and the feedback loop for, the Parliament, on the health of policies and service delivery (SALS, Citation2013). In essence, they are targeted towards inculcating in all stakeholders the notion that public participation in the democratic process does not end with casting votes and the ‘ballot box’; rather, it is for elected officials to also reach out and obtain the people’s inputs for depositing (the inputs) into the processes of Parliament.Footnote22 In the words of an MPFootnote23:

[…] my constituency office is just across the road from the largest public hospital in the Eastern Cape [Province]. So, you have regularly a flow of people when they go to the hospital and they don't get the treatment that they think and the service that they think they should have gotten, they come over to the office and expect you to intervene.

The PEO, as the name implies, undertakes public education on the activities of parliament within the general functioning of the political system. The office has the ‘role to educate the public also as to what can be done, what cannot be done and what their role as the public is.’Footnote28 This office also facilitates the feedback mechanism to the public on the outcomes of their participation in the policy process. Other mechanisms exist to give form and structure to public engagement (see ). A significant part of these mechanisms rest within the confines of, and are coordinated by, the NCOP, constituted by representation from the nine provinces. These diverse mechanisms include the Sectoral Engagements, Taking Parliament to the People (TPTTP), Provincial Week, and the Local Government Week, as further shown in .

Figure 3. Best fit approach to public participation: model. Source: 5th democratic parliament of the Republic of South Africa, September 2020.

The sectoral engagements focus on providing a platform for interest aggregation for politically disadvantaged groups; they also afford the Parliament the opportunity to ‘focus on identified special interest groups by providing them with a platform to raise issues they face daily relating to service delivery, implementation of laws or government policies as well as an opportunity to present recommendations or suggestions for remedial action’ (PRSA, Citation2017, p. 39). The sectoral engagements are facilitated biannually, with the youth parliament every June 16, and women’s parliament in August, where the women are briefed on how the ‘issues of women empowerment’Footnote29 are addressed.

Tools for institutionalised public engagement

Parliament also creatively deploys tools that underscore, as Fung (Citation2009, p. 229) says, ‘how modern societies require contemporary technologies and methods of participation to keep the practice of democracy vital and relevant.’ Institutionalising public engagement extends to the deployment of a communication strategy built on digital and traditional communication platforms and avenues handled by dedicated staff. This communication is aided by sections responsible for communications, including Production and Publishing, PEO and the Public Relations Unit. As explained by an officialFootnote30 ‘we are working together now with the communities, trying to have access to the [..] communities where there’s no access, where there’s no signal or phones, where people don't have these iPhones that they are using.’ These diverse tools and platforms serve as appropriate linkages to the various structures and mechanisms in place to institutionalise engagement, and ‘to ensure that our public has got a choice […] as to where they can go and get us’.Footnote31

The Parliament also extensively uses its website and presence on social media platforms to interface with the public. These platforms, in fact, enabled the legislative institution to quickly adapt social media during the Covid-19 pandemic and the associated lockdown, through live streaming of all House [plenary] and committee sittings on Parliamentary TV, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, in order to promote continuous citizen access to its core business.Footnote32 The parliamentary website undergoes constant revision in order to hone its user functionality to suit emerging trends. One of such revision is the development of the website to a zero-rating status where no data would be charged for accessing the website, to allow free website access for the less financially endowed population.Footnote33 Taking into cognisance the evident digital divide in the polity, Parliament also uses methods such as pamphlets, newspapers, SMS platforms, ‘community radio stations’ and television broadcasts on selected stations including the government-owned South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC).Footnote34 These are to facilitate connections to the deep rural communities (see ).

Institutionalisation and the meaningfulness of engagement

Institutionalisation in South Africa implies a strong commitment in terms of frameworks, resources, initiatives and programmes to the thriving of public engagement and facilitation of citizens’ connection to parliament. The frameworks aid effective patterns of exchanges between representatives and citizens; they also provide quality engagement routes with others seemingly disconnected from digital communication pathways or those who are victims of the country’s digital divide. South Africa’s patterns of embedding societal and institutional behaviours and roles towards enhancing the vertical accountability of the legislature epitomise the sociological axioms of institutionalism. The public engagement framework also attempts to implement a process-oriented institutionalisation (Tatenhove & Leroy, Citation2000) as it has evolved through the processes of forming, preserving, organising, and deconstructing human behaviour towards the institution. This has resulted in South Africa’s legislative institution attaining what can be annotated as ‘value and stability’ (Palanza et al., Citation2016, p. 9), through the sustained investments in institutional structures such the PCO, PDO and PEO.

Studies have documented different facets by which a process of legislative institutionalisation exists; however, standing out are the processes by which a parliament acquires definite autonomous and complex ways of executing its duties or making itself visible. For example, by drawing on the LSPPF, PRSA creatively deploys its own participation model that leverages its organisational structure for maximising inputs and optimising outputs. Public engagement inputs and outputs co-exist with further duties of representation, government oversight, budgetary control, and, law-making. Taken together, the activities are fundamental to sustaining visibility and impact, normalising legislative standards over time, and steering democratisation. Crucially, while the relationship between democratisation and institutionalisation remains complex, the normalisation of standards is foundational to the institutionalisation of legislatures – a function of successful democratisation (Egreteau, Citation2019) – and, in particular, the aspect of the public’s understanding of the role and significance of the institution.

Emerging from the above also are notions drawn from the theory of legislative institutionalisation – an emergence of the analysis of historical trends in the United States Congress by Polsby (Citation1968) to establish interrelations between the institutionalisation of legislative representation and democratic political systems. This is implied by the diversity and opposition that characterises political representation within highly contested and diverse political spaces. It is on this background that Polsby (Citation1968) suggests characteristics of an institutionalised organisation. First, the institution is well-bounded both by its formation, recruitment standards, and differentiation from the environment. The establishment and deepening of boundaries put a control to entry and exit of leaders, such that members are retained within the system, they professionalise their enterprise and limit the chances of new entrants. Second, the organisation is defined by relative complexities arising from the deep interdependence of its internal workings. The growth of internal complexities is indicated by the increasing importance and autonomy of entities and units, such as seen in the structures that PRSA uses to facilitate its engagement with external actors. Third, there is a predominance of universalistic and automatic rather than particularistic and discretionary approaches to conducting its affairs (Egreteau, Citation2019; Polsby, Citation1968).

It can be inferred that institutionalisation leans on the extent and nature of boundaries; and the delivery of outputs and reception of inputs – a course ordered by autonomous but interdependent structures or frameworks. The provisions of South Africa’s LSPPF and PPM, as well as the practicalities, resources and tools of their public engagement, although independent of one other, symbolise a united, multi-channelled approach to strengthening representation and an environment that accommodates meaningful public involvement. It is on this basis that a cultural perspective to institutionalisation buttresses sanctionable, regulated and recurrent processes which are only attained in environments with shared values but are devoid of wanton interference. Furthermore, the formality, legitimacy and resources that the South African legislature boasts of, brings to fore the importance of synthesising legal, cultural and institutional dimensions in a quest to consolidate public engagement. These have been key to developing and sustaining practices across legislative eras.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted examples of good practices on institutionalisation of legislative public engagement – that which focusses on the process through which legal and institutional frameworks are used to set clearly defined templates, and monitoring mechanisms are devised to ensure effective engagement of all stakeholders in parliamentary activities and practices. We have also highlighted the institutional entrenchment of engagement practices including the use of support structures, resources and platforms for carrying out initiatives geared at effective engagement. This suggests that an institutionalised engagement process provides a structural path for the development of public engagement and representative democracy. This article has showed that a complete institutional public engagement process is a function of a right balance between the political and socio-cultural contexts within which the legislature operates, and the deployment of appropriate legal-institutional frameworks and models of public engagement. These are made functional through the right political will to engage, appropriate prioritisation in terms of human and material resources, and adequate monitoring and evaluation to ensure optimum results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Temitayo Isaac Odeyemi

Temitayo Isaac Odeyemi is a doctoral researcher in the School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, UK, where he is working on parliaments and public engagement. He also teaches Political Science at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria. His research has covered different aspects of democratic engagement and mobilisation in Sub-Saharan Africa, including the use of digital technologies by governance actors such as national and subnational legislatures, political parties, police authorities, and electoral stakeholders.

Damilola Temitope Olorunshola

Damilola Temitope Olorunshola is a student of the European Interdisciplinary Master African Studies (EIMAS) programme jointly mounted by the University of Porto, Portugal, University of Bayreuth, Germany and the Bordeaux Montaigne University, France. She has a degree in Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE) from the Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria. Her research interests cut across African studies, small business and sustainable development, governance, and democratic studies.

Boluwatife Solomon Ajibola

Boluwatife Solomon Ajibola works as a Research Manager at the University of Leeds, UK. His research interest lies at the intersection of social movements, ICTs for Development, and democratic studies. He previously obtained a degree in International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies from the London School of Economics, UK – which informs his research and writings on social movements-induced social emergencies and the development-democracy nexus.

Notes

1 Interview with Senior Manager, Core Business – Legislative Sector Support Unit, the Parliament of Republic of South Africa (PRSA), (October 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

2 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

3 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

4 Interview with Chief Public Communications Officer of the Kenyan National Assembly, (November 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

5 Interview with Representative of Mzalendo (Kenyan CSO), (December 2020), Interview with Irena Maanasa.

6 Interview with Chief Public Communications Officer of the Kenyan National Assembly, (November 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

7 Interview with a representative of Mzalendo, (December 2020), Interview with Irena Maanasa.

8 Interview with a representative of Mzalendo, (December 2020), Interview with Irena Maanasa.

9 Interview with a representative of Mzalendo, (December 2020), Interview with Irena Maanasa.

10 Interview with a representative of Mzalendo, (December 2020), Interview with Irena Maanasa.

11 Interview with Senior Manager, Core Business – Legislative Sector Support Unit, the PRSA, (October 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

12 Interview with Senior Manager, Core Business – Legislative Sector Support Unit, the PRSA, (October 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

13 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

14 Interview with Senior Manager, Core Business – Legislative Sector Support Unit, the PRSA, (October 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

15 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

16 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

17 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

18 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

19 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

20 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

21 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

22 Interview with Senior Manager, Core Business – Legislative Sector Support Unit, the PRSA, (October 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

23 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

24 Interview with Team Lead, Parliamentary Democracy Office, Northwest Province, PRSA.

25 Interview with Team lead, Parliamentary Democracy Office, the Northern Cape Province, PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

26 Interview with Team lead, Parliamentary Democracy Office, the Northern Cape Province, PRSA, , (September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

27 Interview with Team Lead, Parliamentary Democracy Office, the Northern Cape Province, PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

28 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

29 Interview with Team lead, Parliamentary Democracy Office, the Northern Cape Province, PRSA,(September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

30 Interview with Team lead, Parliamentary Democracy Office, the Northern Cape Province, PRSA,(September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

31 Interview with Section Manager, Production and Publishing in PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

32 Interview with Section Manager, Production and Publishing in PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

33 Interview with Section Manager, Production and Publishing in PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Maya Kornberg.

34 Interview with the House chairperson responsible for Committees, Oversight and ICT, National Assembly of the PRSA, (September 2020), Interview with Temitayo Odeyemi.

References

- Arnold, J. R. (2012). Parliaments and citizens in Latin America. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 18(3-4), 441–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2012.706055

- Aurbach, E., Kuhn, E., & Niemer, R. K. (24 April, 2019). Organizing and reflecting different types of engagement activities: The Michigan public engagement framework. Retrieved February 26, 2022, from https://www.informalscience.org/news-views/organizing-and-reflecting-different-types-engagement-activities-michigan-public-engagement-framework.

- Barkan, J. D. (2009). African legislatures and the “third wave” of democratization. In J. D. Barkan (Ed.), Legislative power in emerging African democracies (pp. 1–31). Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Bertsou, E. (2019). Political distrust and its discontents: Exploring the meaning, expression and significance of political distrust. Societies, 9(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9040072

- Birgen, J. R., & Okoth, E. M. (2020). Our role in securing public participation in the Kenyan legislative and policy reform process. Natural Justice. Retrieved June 12, 2022, from https://naturaljustice.org/our-role-in-securing-public-participation-in-the-kenyan-legislative-and-policy-reform-process/.

- Clark, A., & Wilford, R. (2012). Political institutions, engagement and outreach: The case of the northern Ireland assembly. Parliamentary Affairs, 65(2), 380–403. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsr039

- Davidson, S., & Stark, A. (2011). Institutionalising public deliberation: Insights from the Scottish parliament. British Politics, 6(2), 155–186. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2011.3

- Dri, F. (2009). At what point does a legislature become institutionalized? The Mercosur Parliament's path. Brazilian Political Science Review, 4(3), 32–38.

- Egreteau, R. (2019). Towards legislative institutionalisation? Emerging patterns of routinisation in Myanmar’s parliament. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 38(3), 265–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1868103419892422

- Fung, A. (2009). Participate, but Do so Pragmatically. In OECD (Ed.), Focus on citizens: Public engagement for better policy and services (pp. 227–230). OECD Publishing.

- Interparliamentary Union (IPU) & United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). Global Parliamentary Report 2022 - Public engagement in the work of parliament. IPU & UNDP.

- Keman, H. (12 October, 2017). Institutionalization. Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/institutionalization Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- Landry, J., & Angeles, L. (2011). Institutionalizing participation in municipal policy development: Preliminary lessons from a start-up process in Plateau-Mont-Royal. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 20(1), 105–131.

- Ledesma-Gumasing, R., & Zimmermann, W. (2020). Institutionalisation of co-production in the reform of a public enterprise: insights from the Philippines. Development in Practice, 30(2), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1662769

- Lee, M. J., & Levine, P. (2016). A new model for citizen engagement. Stanford Social Innovation Review Fall, 14(4), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.48558/4R5V-1G98

- Leston-Bandeira, C. (2012). Studying the relationship between Parliament and citizens. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 18(3-4), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2012.706044

- Leston-Bandeira, C. (2022). How public engagement has become a must for parliaments in today’s democracies. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 37(2), 8–16.

- Lukensmeyer, C. J. (2009). The next challenge for citizen engagement: Institutionalisation. In OECD (Ed.), Focus on citizens: Public engagement for better policy and services (pp. 231–234). OECD Publishing.

- Madue, S. (2012). Perceptions on the institutionalization of public participation in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 3(12), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2012.v3n12p21

- Martinez, K. P. (2018). Local congresses in Mexico. A model to assess their degree of institutionalization. Political Studies (Mexico), 44, 65–91.

- Odeyemi, T. I., & Abati, O. O. (2021). When disconnected institutions serve connected publics: subnational legislatures and digital public engagement in Nigeria. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27(3), 357–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2020.1818928

- Odeyemi, T. I., & Abioro, T. (2019). Digital technologies, online engagement and parliament-citizen relations in Nigeria and South Africa. In O. Fagbadebo & F. Ruffin (Eds.), Perspectives on the legislature and the prospects of accountability in Nigeria and South Africa (pp. 217–232). Springer.

- Oecd (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2009). Focus on citizens: Public engagement for better policy and services. OECD Publishing.

- Oecd (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2020). Innovative citizen participation and New democratic institutions: Catching the deliberative wave. OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/339306da-en.

- Opalo, K. O. (2015). Institutions and political change: The case of African legislatures (PhD thesis. Department of Political Science, Stanford University).

- Palanza, V., Scartascini, C., & Tommasi, M. (2016). Congressional institutionalization: A cross-national comparison. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 41(1), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12104

- Parliament of the republic of South Africa. (2014). 4th parliament legacy report 2009–2014. PRSA.

- Parliament of the republic of South Africa. (2015). The strategic plan of the 5th democratic parliament, 2014–2019. PRSA.

- Parliament of the republic of South Africa. (2017). Public participation model. PRSA.

- Parliament of the republic of South Africa. (2019). Legacy report of the fifth term of parliament 2014-2019. PRSA.

- Perry, J. (2021). Trust in public institutions: Trends and implications for economic security. Policy Brief No 108. United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs.

- Polsby, N. W. (1968). The institutionalization of the U.S. House of representatives. American Political Science Review, 62(1), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953331

- Posel, D. (2001). Race as common sense: Racial classification in twentieth-century South Africa. African Studies Review, 44(2), 87–113. https://doi.org/10.2307/525576

- Prior, A. M. (2019). Living this written life”: An examination of narrative as a means of conceptualising and strengthening parliamentary engagement in the UK (Doctoral dissertation. University of Leeds).

- Ravazzi, S. (2016). When a government attempts to institutionalize and regulate deliberative democracy: the how and why from a process-tracing perspective. Critical Policy Studies, 11(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2016.1159139

- Republic of South Africa. (1996). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Act 108 of 1996). Government Publications.

- SALS (South Africa Legislative Sector). (2013). Public Participation Framework for the South African Legislative Sector.

- Scott, R. (2009). An analysis of public participation in the South African legislative sector (MPA Thesis submitted to Stellenbosch University, South Africa).

- Steiner, R., & Kaiser, C. (2017). Democracy and citizens’ engagement. In T. R. Klassen, D. Cepiku, & T. J. Lah (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of global public policy and administration (pp. 167–178). Routledge.

- Tatenhove, J., & Leroy, P. (2000). The institutionalisation of environmental politics. Political Modernisation and the Environment. In J. Tatenhove, B. Arts, & P. Leroy (Eds.), Political Modernisation and the Environment: The Renewal of Environmental Policy Arrangements (pp. 17–33). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9524-7_2.

- Waterhouse, S. J. (2015). People's parliament? An assessment of public participation in South Africa's legislatures (MPhil in Social Justice dissertation, University of Cape Town, South Africa).