ABSTRACT

Past research in Health and Physical Education has repeatedly highlighted that curriculum development is an ongoing, complex and contested process, and that the realisation of progressive intentions embedded in official curriculum texts is far from assured. Drawing on concepts from education policy sociology this paper positions teacher educators as key policy actors in the interpretation and enactment of new official curriculum texts. More specifically, it reports research that has explored four teacher educators’ engagement with a specific feature of the new Australian Curriculum in Health and Physical Education (AC HPE); five interrelated propositions or ‘key ideas’ that underpinned the new curriculum and openly sought to provide direction for progressive pedagogy in Health and Physical Education. The paper provides conceptual and empirical insight into teacher educators consciously positioning themselves as policy actors, motivated to play a role in shaping policy directions and future curriculum practices. As such, the teacher educators in this project are identified as policy entrepreneurs and provocateurs. The paper details a dialogic research process between the researchers that was designed to make curriculum interpretation a more transparent, collaborative and generative process. The data reported illustrates the research process supporting teacher educators to engage in productive debate about the possible meanings and enactment of the five propositions. Analysis reveals differing perspectives on the propositions and a shared investment in efforts to support their progressive intent. Empirically, the paper highlights the critical role that teacher educators will play in the ongoing enactment of a new curriculum that is overtly identified as ‘futures oriented’. Conceptually, the paper adds depth and sophistication to understandings of teacher educators as policy actors. Methodologically, we propose that the research process described can be usefully adopted by other teacher educators and teachers engaged in similar processes of curriculum development, interpretation and enactment.

Introduction

Attempts to advance ‘futures oriented’ curriculum developments at a national level are by no means new in education. Indeed, many readers will be familiar with developments that have purported to respond to calls for education to meaningfully engage with changing societies, jobs and technologies. Many readers may also reflect upon an apparent gap between the progressive rhetoric and pedagogical reality of many curriculum reforms. Finally many may, like ourselves, be teacher educators and researchers. The research reported in this paper puts a spotlight on the role of teacher educators in supporting the realisation of progressive pedagogical intentions associated with new curriculum. Specifically, our research relates to the Australian Curriculum Health and Physical Education (AC HPE) (ACARA, Citation2018a), that not only made explicit futures orientations, but that also encompassed an arguably unique foundation to facilitate the advancement of new pedagogic directions in Health and Physical Education (HPE) (Macdonald, Citation2013). This foundation took the form of five propositions or key ideas that underpinned the development of the new curriculum specifications: a focus on educative purposes, taking a strengths-based approach, value movement, develop health literacy, and include a critical inquiry approach (ACARA, Citation2018b). While these propositions have been lauded as central facets of an innovative curriculum, as we discuss below, their positioning in the curriculum was notably fragile and their pedagogic meanings uncertain and fluid, destined to emerge amidst varied interpretation as the AC HPE was adapted and enacted across Australia’s education jurisdictions, within teacher education programmes, and in schools (Penney, Citation2013).

This research reflected that as teacher educators, we recognised both the fragility and the innovative potential that the propositions presented for HPE. It focuses specifically on teacher educators as key policy actors (Ball, Maguire, Braun, & Hoskins, Citation2011a, Citation2011b) in the interpretation and enactment of new official curriculum texts. In our view teacher educators should be actively questioning, unpacking and debating policy in order to shift it from abstractions to school/classroom realities and meaningful visions of future practice, and explore tangible ways in which overall goals and visions of curriculum reform can be enacted in/as curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. The project was therefore designed to extend conceptual and empirical insight into teacher educators positioning themselves as policy actors, motivated to play a role in shaping policy directions and future curriculum practices. This research sought to positively engage with the personal, local and global contexts of policy enactment (Braun, Ball, Maguire, & Hoskins, Citation2011), move beyond discourses and processes that appear inherently limiting, and instead facilitate generative engagement with/in policy enactment.

The paper details a dialogic research process between the researchers that was designed to make curriculum interpretation a more transparent, collaborative and generative process that enabled teacher educators to engage in productive debate about the possible meanings and enactment of the five propositions. Our findings capture both specific detail of teacher educators’ curriculum interpretation and a research process that we suggest can usefully be adopted by other teacher educators and teachers engaged in similarly complex processes of generating pedagogic meanings from new official curriculum texts. In analysis and discussion we engage with Ball and colleagues’ conceptual insights (Ball et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Braun et al., Citation2011) and draw further on the Foucauldian perspectives that underpin their work in policy, to critically engage with the commonalities, disparities, constraints and possibilities that are articulated in our work as teacher educators consciously and subconsciously shaping curriculum discourses and practices in HPE.

Policy enactment, curriculum reform and teacher education

As indicated, this research draws on Ball et al.’s (Citation2011a) conceptualisation of policy actors that sought to identify ‘different sorts of roles, actions and engagements embedded in the processes of interpretation and translation’ and that categorised these in terms of eight ‘types of policy actor or policy positions’ (p. 625, original emphasis); narrators, entrepreneurs, outsiders, transactors, enthusiasts, translators, critics, and receivers (Ball et al., Citation2011a, p. 626). Our research has viewed policy positions as fluid rather than fixed and has also been open to exploring positions that are not clearly represented in Ball et al.’s original categorisation. Hence, our focus is in part captured in the notion of policy ‘entrepreneurs’ engaged in ‘advocacy, creativity and integration’ (Ball et al., Citation2011a, p. 626). Alongside this, we identify with a role of provocateur. Accordingly, this paper explores ways in which teacher educators can simultaneously provoke, contribute to and extend policy debates at a critical point of curriculum policy needing to be de- and re-contextualised in order for curriculum intentions to be meaningfully connected with teachers’ practices.

In important respects, therefore, this project and our analysis focuses attention on the interface of teacher education and curriculum futures. In stating this we acknowledge the distinctly unfinished nature of official curriculum texts and recognise that their enactment is destined to involve ‘creative processes of interpretation and translation, that is, the recontextualisation through reading, writing and talking of the abstractions of policy ideas into contextualised practices’ (Braun et al., Citation2011, p. 586). As Braun et al. (Citation2011, p. 586) explain, policy is ‘complexly encoded in sets of texts and various documents and it is also decoded in complex ways’. Ball et al.’s (Citation2011a) original analysis recognised the distinct ways in which individual teachers engage with policy, bringing individual value positions to their readings, while in different positions of authority, in particular institutional circumstances and at particular times. While other research in HPE has pointed to the limited impact that teacher education appears to have on established practice (Macdonald, Hunter, Carlson, & Penney, Citation2002), this research reflects that we know little about how policy developments are contextualised into the everyday practices of teacher educators, and what it therefore means for teacher educators to ‘do policy work’ (Ball et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b) in and amidst curriculum reform, through their own pedagogic practice. This paper therefore directs attention to processes of interpretation and translation, or de- and re-coding of curriculum policy texts, by four policy actors who shared a specific desire to bring to the fore the innovative potentialities of complexly encoded curriculum texts. Following Braun et al. (Citation2011) we associate such policy action with creativity and also a degree of caution, to effectively navigate the imperatives of global and supranational forces currently driving curriculum policy reform (Ball, Citation1998; Savage & O’Connor, Citation2015) and framing what become recognised and established as the pedagogic possibilities of policy (Ball, Citation1998; Ball, Maguire, Braun, & Hoskins, Citation2011b). As we explain later in the paper, practically, as a process this policy action requires multiplicity of reading, writing and most especially talking.

Picking up the Ball: teacher educators make sense of policy and giving meaning to policy

As indicated above, this research acknowledged that teacher educators need to similarly be understood as policy actors, and as at least to some extent, able to pursue various policy roles and thereby generate multiple meanings in their policy work with prospective future teachers. Expanding on enactment Ball et al. (Citation2011b) proposed that it is valuable to distinguish between the meanings generated in an initial, ‘sense-making’ reading of policy, and subsequent understandings of the possibilities presented by policy. As Ball et al. (Citation2011b) emphasise, both need to be understood as embedded with, and reflective of, particular power relations, and individual and institutional frames. Our research therefore sought to critically examine both the initial ‘sense making’ and ways in which each of us as teacher educators recognised, and felt able to pursue, particular pedagogic possibilities presented by the AC HPE. This reflected that certainly from our perspective, teacher educators are positioned as important mediators of the continuities and disparities that are continuing to arise amidst the ongoing recontextualisation and adaptation of Australian curriculum texts by state-based curriculum authorities (Penney, Citation2018; Savage, Citation2018). Furthermore, we anticipated variability in our decoding and recoding of policy and saw this as both important to explore, and something that would be inherently generative.

While foregrounding our ‘policy work’ as teacher educators and policy actors, following Ball et al. (Citation2011b) we necessarily also draw attention to the ‘work of policy’ in shaping contemporary contexts of teacher education and impacting us as ‘policy subjects’ (p. 611). Internationally, teacher education as a whole and physical education teacher education specifically, has been and remains clearly impacted by discourses of performativity, accountability, corporatisation and regulation (Kirk, Citation2014). Our emphasis is that talk of agency needs to be understood as arising from and inevitably framed by this contemporary context of teacher education, with its inherent accreditation requirements, economic challenges, and pragmatic pressures for teacher educators seeking to simultaneously fulfil expectations associated with teaching and learning, research and service in higher education – while also staying true to personal professional values. Our later reporting of data illustrates the central role that these values and positionality (Maguire, Braun, & Ball, Citation2015) played in our interpretation and enactment of new curriculum policy, and reaffirms the messy nature of agency ‘inside policy’ (Lambert, Citation2018a).

Before detailing our research approach, we provide additional important background about the curriculum text that as teacher educators, we were charged with embedding into our practice.

An Australian story: curriculum reform and policy paradoxes in HPE

It is not possible here to comprehensively dscribe what continues to be a complex, contested and fragile curriculum development and implementation process across the federated education systems in Australia. We therefore confine our focus to the five propositions that have variously been defined and positioned as new and different (Macdonald, Citation2013; McCuiag, Quennerstedt, & Macdonald, Citation2013), radical and productive (Hickey, Kirk, Macdonald, & Penney, Citation2014), full of opportunity and potential (Penney, Citation2013) and as pointing towards pedagogical and assessment practices (Wright, Citation2014). Our focus on the propositions also reflects important paradoxes – firstly, around who is speaking, engaging and interpreting (i.e. the role of teacher educators in curriculum policy reform) and who is listening (or not); and secondly, matters of ‘presence but silence’ in relation to the five propositions. In respect to this latter point, State-based curriculum developments have signalled clear support for the five propositions, while at the same time doing little to clearly connect them with matters of content and assessment that are an inevitable priority for teachers (Lambert & O’Connor, Citation2018b). Hence, whilst the propositions remain a point of prospective commonality across Australia, divergences in enactment of the AC HPE across jurisdictions has identified that the policy and educative potential of the propositions remains largely untapped (Lambert & O’Connor, Citation2018b; Penney, Citation2018).

As teacher educators familiar with both the perils and potentialities of curriculum policy reform in HPE, we recognised the propositions as advancing curriculum reform into somewhat uncertain and possibly, innovative territories. The propositions serve dual roles, as the essence of the ‘front end’ of the curriculum (guiding ideas, rationales, and philosophies) and as prospectively strong frames for pedagogy. We fully anticipated that they would mean different things to different people in different places, and that they could be seen to be both legitimising and denying various (innovative and conservative) curriculum possibilities (Penney, Citation2013). Commentaries addressing each of the propositions and the five as a collective, are highly contestable and their meanings notably fluid (Alfrey & Brown, Citation2013; Brown, Citation2013; Dinan Thompson, Citation2013; Hickey et al., Citation2014; Leahy, O'Flynn, & Wright, Citation2013; Macdonald, Citation2013; McCuiag et al., Citation2013; Penney, Citation2013; Wright, Citation2014). Subsequent research with teachers has reaffirmed these expectations (Lambert & O’Connor, Citation2018b).

The focus of this project was on exploring how in our work as teacher educators, we would interpret and enact the propositions, and why? We began the research with a set of interpretive questions that prompted us to reflect upon, put into writing, and talk about, the meanings, purpose, application, and value of the propositions in our everyday work as teacher educators, and to also consider any uncertainties or concerns that we had about them. We asked ourselves the following prompt questions, responses to which are the focus of our findings and discussion sections.

How would you define each of the five propositions?

What do you see as the purpose of the five propositions? How do you see them working individually, collectively? Why do you view them in these ways?

What other lens, frameworks, ideas, theories or notions are you drawing upon to make sense of the five propositions?

In the sections that follow we seek to illustrate the value of a research process that supported the generation of varied readings, meanings, and interpretations of policy texts, and in doing so, both challenged and extended what could be envisaged as legitimate and possible courses of enactment. We present this process as an important means of extending our own knowledge and practices as teacher educators.

Research design

This research was a case study investigation of four teacher educators’ policy interpretation and enactment. At the time we were all teaching into a four-year undergraduate Bachelor of Education (HPE) course preparing teachers to teach primary and/or secondary HPE in Victoria, Australia. We worked together on this project for 12 months. We came to the project with notable points of difference with regards to formal degree training, teaching experience, research interests, age, professional goals, motivations, academic position/level, engagement with higher education agendas, experience in curriculum policy analysis and theoretical inclinations. We draw attention to these in order to foreground our personal, professional and theoretical starting points or positionality. As the data that follows illustrates, our subjectivities differ and converge, making us each a particular kind of HPE policy actor with particular understandings and motivations. Remaining reflexive of our subjectivities and biases has been an important aspect of this project and was central to the research process detailed in a moment.

Participant positionality: who are we as teacher educators?

Each of the teacher educators in this project had different career histories of involvement in teacher education and research associated with physical education and HPE. The distinction between the ‘physical education’ and HPE is made here to acknowledge that two of the teacher educators had previously worked UK-based settings of physical education teacher education (PETE), whilst the other two went through training in Australia, one in sports science, and the other a HPE specialised degree. Given we are claiming teacher educators play a significant role in curriculum enactment we felt it important to share a little about who we each are in relation to our teacher educator identities. We do this below.

Researcher 1 (author 1) (female, lecturer, new to team): I have a long history of teaching HPE at both secondary and tertiary level. As a new member to the Faculty I was keen to explore research grant opportunities as well as work with my new colleagues. My enthusiasm for the project overshadowed my relative research and publication inexperience, and whilst I found it a little disconcerting to be driving a project such as this, I was encouraged and supported by my three colleagues.

Researcher 2 (author 2) (female, professor): My background includes involvement in teacher education in UK, Australian and New Zealand universities and a long history of research in curriculum reform in HPE. I firmly identify as a HPE teacher educator. I brought extensive knowledge of HPE curriculum developments, policy ‘dynamics’, and research. At the same time, I was aware that the research process generated some anxiety, about how contributions and/or responses to others’ responses would be received by colleagues. Author 1 led the project and coordinated our responses and next steps with this ‘positionality anxiety’ very clearly foregrounded.

Researcher 3 (female, senior lecturer): My expertise within teacher education relates to movement and physical activity, curriculum development, and professional learning. I was enthused to work on the project because it presented an opportunity to work with a new research team at the same time as reflecting and improving my teaching practice, whilst also holding promise of supporting pre-service teachers in the future.

Research 4 (male, course leader, senior lecturer): My initial degree was in sports science and I focused my research on motor learning and the development of motor skills. I now consider myself to be more well-rounded and can work across many boundaries that relate to health and physical education. I was excited to be involved in this project to explore my own practice whilst learning from the rest of the team. The trust in the team was an important part of this project.

A process of shared discovery: text responses and reader responses

The research occurred over a 12-week semester in 2016 and was conducted as part of university funding supporting innovation in teaching and learning. The project had two phases. The first involved ‘shared discovery’ of the meanings we each ascribed to the propositions, and why. The second focused on our experiences of applying the propositions in specific units we each had responsibility for teaching. This paper reports upon Phase 1, with aspects of Phase 2 reported elsewhere (Lambert, Citation2018a).

This process for ‘shared discovery’ in Phase 1 had two steps. In step 1, we individually generated a commentary about each of the five propositions by responding to the three prompt questions. We refer to these initial commentaries as the text responses. In step 2, all text responses were de-identified and circulated to everyone by the lead author as Word documents. These documents were then read and responded to directly using Word ‘tracked changes’ and comment functions. We called these texts the reader responses. As teacher educators and researchers we agreed to emphasise a dialogic process of sense-making and meaning-making, and our intention was to frame the ‘reader responses’ as ‘thought bubbles’ that provided a commentary/conversation back to the author and that also represented a conversation ‘with ourselves’ about the propositions. It was ‘out loud’ in the margins in order to capture our responses to each other’s ideas. We sought to make this exchange an open, honest, accessible and spontaneous dialogue that we could also ‘step back from’ and reflect upon. In saying this we reflect that while we represented varying levels of academic appointment (Professor, Senior Lecturer, and Lecturer), within and beyond this project we collectively sought to maintain mutually respectful and open collegial relationships, and recognised the different professional experience and insights that we variously brought to our reading of the AC HPE and our work as teacher educators. The research process was thus designed to simultaneously capture and challenge our thinking. We encouraged a conversational as opposed to critical tone, while at the same time taking a critical stance to what we were reading. For example, we agreed that it was OK to disagree or agree, and that explaining why was especially important. Tensions, clarity, questions, confusion, frustration, agreement, disagreement, uncertainty were all variously voiced in our responses, that sat out in the open in the margins of another’s thinking ().

Methodologically this is interesting work because it’s not the usual kind of journaling or writing often deployed in research, nor is it simply back and forth email journaling, conversations or documenting. Rather, following Freire (Citation1970), we conceptualise ‘tracked changes’ as research/dialogue, a form of dialogic research or dialogue as research (MacInnis & Portelli, Citation2002) and as an ethical meaning making and data collecting mode of communication with transformative potential (Costantino, Citation2008). The instrument/method i.e. ‘tracked changes’ is a computer-mediated form of communication and collaboration, yet is individualised. The ‘tracked changes’ and comments represented and stimulated conversations at the same time, thus opening the policy space to new, generative understandings. Responding to each other’s ‘tracked changes’ provided a further ‘layer’ of data alongside the original ‘text responses’, and moved the work closer to the political and emancipatory aims of Freire (Citation1970). In the Freire (Citation1970) sense our dialogue was collegial and relational, open and safe in that we were able to express our ideas, values, and perspectives with the aim of solving a problem and/or creatively engaging in mutual inquiry – we sought to learn something. Our sense-making process prompted critical reflection as well as sensitive analysis. We were each exposed and challenged to ‘take a stance’ in relation to the propositions through the writing and response process. The process provided a colleagial means of exploring ideas, fleshing them out, critiquing and questioning, that expanded our collective understanding of the five propositions.

Data analysis

The data was analysed sequentially, focusing on one question at a time, working across the four participants. As we had a hunch (Yom, Citation2015) that our individual meanings might differently or similarly emerge from our real-world conditions (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Citation2013), subjectivities, positionalities, experiences and motivations, we decided to move inductively backwards and forwards, up and down and across the data and the theorising (Yom, Citation2015). These multiple readings of the raw data in conversation with theory helped us to tease out frequently occurring ideas, concepts, and themes as well as dominant discourses (Eisenhardt, Graebner, & Sonenshein, Citation2016). We were progressively seeking to ascertain our meaning-making (interpretations and views) around each proposition, identify where our views converged or diverged, and where particular meanings and responses ‘came from’. Our stance on purpose (Q2) and our personal lens (Q3) provided insights into how we came to have particular views. These responses thus indicated the discourses we variously drew upon in order to make sense of firstly, the propositions, and subsequently, others’ commentaries on them.

There were three layers of data analysis in this research, reflecting the layered process of data generation described above.

The individual ‘text response’

In a fairly typical initial analysis process each individual’s response to each question were highlighted in order to tease out the essence of each answer (e.g. what each proposition meant or was defined as by each participant). Responses were summarised as a mind map in order to develop a list of all meanings/definitions across the responses for each proposition, with recurring themes/definitions highlighted via a tick with similar ideas clumped together to get towards a theme. For example, Strengths Based Approach was consistently defined as a shift from a deficit model and linked to social justice agendas. One theme became ‘not risk/deficit’ and another ‘equity’.

(2) The ‘reader response’

Initial coding of the ‘tracked changes’ similarly used the process of highlighting and mind-mapping. The ‘reader responses’ were scrutinised for similarities and differences which then formed the coded themes. Words like ‘I agree/disagree’, ‘but’, ‘however’, ‘nice idea’, ‘I think’ signalled similarities/differences. We also found comments like ‘what about’, ‘have you thought about’ prompted or initiated an extension/enhancement of ideas that were neither similar nor different but that emerged synergetically between the dialogue. We coded these as emergent ideas, they included: ‘value’, ‘definitions’, ‘connections’, ‘concerns’, ‘equity’, ‘criticality’ and ‘positionality’.

(3) Thematic analysis

When the themes and emergent ideas from 1 to 2 above were read collectively across the four participants and five propositions, a number of common notions about the propositions were identified. These were: ‘valuable and important’, ‘familiar’, ‘connected’, ‘critical’. Alongside these we also expressed some ‘concerns’ around ‘equity’ and ‘positionality’. In concert with Q2 and especially Q3 responses, these commonalities were then used to identify some of the emerging deeper themes at play in our de- and re-contextualisation of the five propositions; namely, ‘concern and loss’, ‘knowledge and power’, and ‘hope and resistance’. It is these themes that guide the discussions that follow.

Findings and discussion

The data generated illustrates that both the meaning given to any individual proposition and how the propositions are collectively being interpreted (i.e. meaning, function and purpose), are important in relation to the pedagogic possibilities that will and will not be generated and legitimated within and through teacher education. We therefore first report data relating to individual propositions, and then explore insights associated with the propositions collectively. Finally, we direct attention to the discourses drawn upon and deployed in our process of reading, writing and speaking curriculum policy. In reporting data, we display quotations presented in regular text as an individual’s ‘text response’, and use italicized text for extracts from ‘reader responses’. Screenshot figures are also provided to support the points being made and to demonstrate the ‘tracked changes’ methodology. P1, P2, etc. is used to designate the teacher educator participants.

Viewing the propositions individually

Focus on educative purposes (FOEP)

This proposition speaks to the perception that HPE does not have a high standing in education, and an associated failing of HPE educators to consistently and convincingly convey this value and purpose (Kirk, Citation2010; Penney, Citation2013). We each expressed a frustration that there is a need to explicitly state that HPE should have educative purpose/value.

P1: Seems so obvious. If it were math or English, so why do we need to state this in PE?

P2: Such an obvious thing so why do you think it needs to be here at all?

P3: … why is this such a ‘new’ notion? … I mean surely HPE teachers associate educative outcomes to what they do? Don’t they???

P4: It’s almost ridiculous that we have to re-frame towards education.

Our data indicated recognition of the simple message that this proposition conveys, that learning should be at the heart of HPE.

P2: For me this reflects the need to simply ask ‘what is it intended that students will learn? … ‘educative’ I tend to equate with ‘learning’.

As we explored the proposition more deeply a greater appreciation of the scope and relevance of the proposition emerged. For example, our commentaries and responses engaged with what it might mean in terms of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment practices, how it can productively intersect with and inform enactment of the other propositions, and its connection to broader visions of equity supposedly driving curriculum reform ().

P1: I see this particular proposition sitting across other propositions

P2: There is certainly a case … but I’m also aware a case can be made for different positioning with others – eg critical inquiry – similarly cross-cutting the rest.

Strength based approach (SBA)

The following extracts reflect that this proposition gave rise to varied responses inherent in which were multiple meanings, diverse interpretations and a number of specific theoretical deployments, including socio-cultural perspective, health and wellbeing, equity and inclusion, complexity and systems theory, and Antonovsky’s salutogenic framework (see McCuiag et al., Citation2013).

P1: I like to think about complexity and interrelated systems of influence … I do find Antonovsky theory a bit closed off from broader ecological (enviro/policy) influences and is perhaps too focussed on the individual or local community but I am able to navigate and reconcile this

P2: It raises fundamental questions about health and wellbeing … I now also firmly link it to my interests in equity and inclusion

P3: The approach must be fair and equitable and take the socio-cultural factors of students’ lives into account every single day

P2: I like the idea of drawing on strengths rather than focussing on what you don’t have

P3: It’s about untapping potential in safe and supportive environments and helping it to bust out

P4: … [it’s] about moving beyond a deficit, reactive model

Concerns were also expressed about whether and how these features would be realised in practice. For example, tensions were identified between the orientation of many current resources and the expectation that teachers could re-work them to reflect a SBA ().

P2: This is for me the approach most teachers will ‘get’ and be positive about adopting – but I’m not sure many resources etc support the stance

P3: I agree though am concerned here about the PE teacher values thing here, and the ways in which teachers perpetuate inequity everyday and yet are totally unaware … [a] very hard nut to crack in a society predicated upon and reinforcing ‘normalised views’

There was also an awareness that this proposition ‘can mean many things to many people’ (P2). This person connected strongly with a socio-ecological perspective in reflecting upon the differing ways in which the proposition may be read and enacted:

P2: I do find this a little too focussed on the individual though … Strengths can be more than developing ‘their’ (reads individual) strengths, even in collective ways. Could the strengths sit outside the individual or the potential for individual development? In the ACHPE, it states communities have strengths which is important

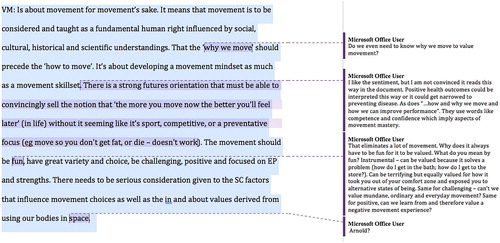

Valuing movement (VM)

Collectively we contested the ‘official’ representation of this proposition. Key to this was a shared frustration that this proposition was seemingly grounded in the work of Peter Arnold (and specifically, his framework of education ‘in’, ‘through’ and ‘about’ movement, see Brown, Citation2013), and yet from our perspective, the influence of that work is opaque in the AC HPE. Our collective frustration reflected our anticipation that key elements of Arnold’s work will not find an expression in the everyday practices of teachers, amidst a ‘simplistic’ translation of VM, and that this will translate into a maintenance of status quo in relation to the forms of movement that are privileged in HPE ().

P2: Arnold’s framework [see Brown, Citation2013] underpins my reading of the proposition – or more, what I take to the proposition to give it meaning

P3: Assuming teachers know what this is? Was lost in translation …

P4: … proposes that movement should be valued for its own sake as opposed to being viewed as instrumental in achieving other means (e.g. health, fitness, skill)

P3: What’s to stop teachers from just doing the same old footy units as always?

At the same time this proposition stimulated debate around the core business of HPE, what the legitimate purpose and position of movement in the curriculum is, and most especially, what it means to value movement. Variously, our responses called into question what enactment of this proposition might mean for HPE: to what extent and in what ways might embodied learning/knowing be valued?; would current understandings of ‘what counts as movement’ be challenged?; what is the role of movement in HPE?; and by association, what is the link between this and other propositions?

P3: The movement should be fun, have great variety and choice, be challenging, positive and focussed on educative purposes and strengths

P1: I like the sentiment but am not convinced it reads that way in the document … They use words like competence and confidence which imply aspects of movement mastery

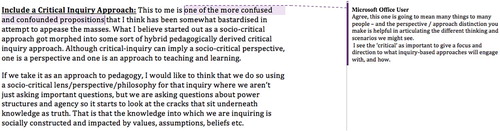

Critical inquiry (CI)

This proposition was also one we could each readily relate to and easily define in relation to our personal standpoints on HPE and as tertiary educators. We could all see it spanning the learning area, as both a lens and pedagogy to inform curriculum enactment. Once again, we also saw connections to/with other propositions ().

P2: This is another proposition that I interpret as strongly cross-cutting the others and presenting a lens that can underpin and inform HPE curriculum pedagogy and assessment in powerful ways.

Our concerns were about where such a way of thinking might head or play out in practice/reality related to the notion of ‘critical’, including its deployment, relationship to inquiry, and the influence of teacher values and how they guide practices ().

P2: I feel it particularly open to varied interpretations – centring on what ‘critical’ is taken to mean.

P3: … [others] have very strong views about the ‘critical’ in CI … whilst I agree heartedly with them – is this stance accessible to teachers?

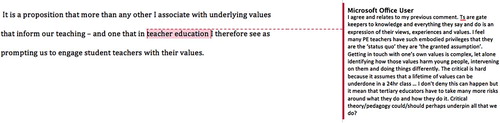

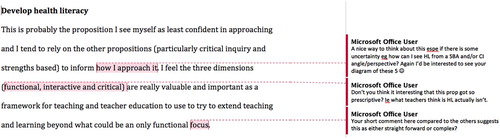

Health literacy (HL)

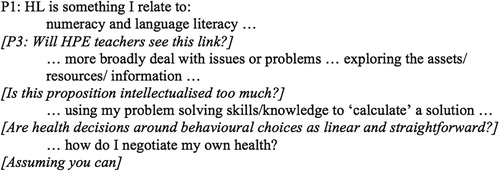

Of all the propositions this generated the most limited commentary. This almost certainly reflects the prescriptive structure of the proposition in the official curriculum text i.e. it’s defined in terms of three dimensions of functional, interactive, and critical (ACARA, Citation2018b). Unlike the other propositions, there is a clear framework for our own and teachers’ engagement with health HL ().

P4: If we take the lead of Freebody, Luke, Nutbeam then HL is conceptualised on 3 levels: Functional (basic – can understand …), Interactive (intermediate – can apply …), and Critical (advanced – can critically …)

The flip side of this apparent clarity is that the official text seemingly closes down space for varied interpretations, raising concern that this might limit further exploration and expression of the proposition in practice. We expressed this influence of the text, as shown by our brief one-line commentaries that firmly aligned with the definitions provided in the official text, and did not really go beyond these. In addition, the absence of expansion may suggest limited familiarity with the three dimensions (and the health promotion context that they originate from), and/or a reluctance to engage with what in some instances was perceived as a functional framework. However, the dialogues below show some tensions as we pushed the boundaries of HL, as well as each other.

P3: HL is about how we GET health or get to be healthy … it’s about feeling ‘health’ and its various dimensions

P2: Again I like the stance but think many people will be taking a more detached look at HL

Despite some fruitful divergences we overwhelmingly agreed that unless a critical perspective is embedded in the interpretation and enactment of HL, it will sit at odds to the overarching vision of the curriculum and broader national goals ().

Viewing the propositions collectively

Whilst each proposition has individual meanings, we all recognised a need to explore the connections and relationships between propositions, and the limitations of viewing them in isolation. We maintain that these interrelationships enhance the meanings of all of the propositions, such that each is enhanced by the possibilities of the others. Our view was that ‘the whole is more than the sum of the parts’; if you take any of the propositions out of the picture, the meanings generated through any of the others will be limited. Interestingly the importance or benefits of making links between and across the five propositions is not made explicit in the AC HPE, nor is it suggested as a strategy to adopt in efforts to express the propositions in practice. Yet our experiences unequivocally suggest that this ‘melding’, ‘merging’, ‘relating’, foregrounding and backgrounding, is absolutely key to their enactment.

P1: I really enjoy the idea of inquiry as a student-centred pedagogy that can incorporate a SBA and draw on HL. I see this [CI] as an integrated proposition that can employ others as part of its enacting

P2: I do see them as inter-weaving and linked – and think it’s important for people to explore many inter-relationships in the process of engaging with them

P3: I see the 5 being closely aligned though at times ‘used’ differently. In some situations (contexts, content, learners) one may be more important or prominent than others. I place FOEP and SBA at the core as the key aim/goal (and always present) with the others circling around as ways to teach and/or skills to develop

P4: I view the propositions as working collectively but each will take the fore at different times

In making the links in this way we have brought the propositions into alignment with each other, subtly shifting meanings to achieve this. In pondering why and how this was possible for us (and not necessarily for all readers), we highlight the importance of the individual perspectives, values, and experiences that we bring to our readings of them. Especially evident in this regard is our shared approach to social justice, equity and a socio-critical view of health and movement. In bringing our individual perspectives to the propositions we saw them as legitimating and supportive of particular sets of discourses and practices, whilst simultaneously troubling others. We acknowledge that not all readers will bring the same perspectives to bear on either the propositions or their policy work, signalling that the propositions will mean different things to different people. On the one hand this is positive, as localised and personalised readings are key to people investing in enactment of the propositions. At the same time this is potentially problematic because it opens the door to using the propositions to legitimate discourses and practices that we would argue fly in the face of the AC HPE curriculum and more specifically, would represent ‘creative non-implementation’ (Ball, Citation1994, p. 20). This brings to the fore issues of power and knowledge circulating in, from and around policy development processes, interpretations, and enactments.

Discourses at play in and amidst our interpretations

Notions of power and discourse form the cornerstone to Foucault’s thinking about subjectivity (within and through multiple workings of power relations) and underpin Ball and colleagues’ conceptualisations of policy (Ball, Citation1994; Citation1998; Ball et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Braun et al., Citation2011; Maguire et al., Citation2015). Following Foucault (Citation1978) we treat discourses as complex, multiple, discontinuous and unstable bodies of knowledge and social practice, and therefore as strongly linked to understanding processes of subjectivity. Foucault (Citation1978, p. 100) views discourses as polyvalent, that is, multiple and circulating and routinely produced by power, with the concept of ‘polyvalence of discourses’ a way of understanding strategies and subjectivity. By viewing discourse as both an instrument and effect of power, as a hindrance and a stumbling block, Foucault (Citation1978, p. 101) invites an exploration of points of resistance within power and discourse and presents us with the opportunity to identify a ‘starting point for an opposing strategy’. Arguably this is central to Ball et al.’s (Citation2011a) conceptualisation of policy actors playing amongst policies, interpreting and enacting them in variously instrumental and resistant ways, while simultaneously being spoken into being by discourse, and produced as the objects about which they speak (Foucault, Citation1978).

From our analysis, the following key discourses appear to be at play in our de- and re-contextualisation of the five propositions, and arguably their de – and re – contextualisation of us: ‘knowledge and power’, ‘concern and loss’, and ‘hope and resistance’.

‘Knowledge and power’

P1: Social ecology, social justice

P2: Bernstein’s work … critical education policy sociology … Ennis’s work on values and beliefs … Green’s work on philosophies

P3: Socio-cultural view of HPE … feminism; poststructural theory … neuroscience …

P4: Critical theory, socio-cultural theory, salutogenesis, Arnold, Nutbeam, Luke & Freebody

It is clear above that the theoretical resources we respectively drew upon to understand curriculum reform are nuanced and complex. By association we are complicit in processes that wield and resist power in uncertain ways. We acknowledge we are in a privileged position as engaging with and generating these kinds of readings of curriculum policy is our core business as critical teacher educators, policy entrepreneurs and provocateurs. Issues of language, definitions, or whose knowledge counts are inherently tied to issues of positionality and subjectivity. We are positioned and position ourselves as amongst those responsible for critiquing, challenging, and rethinking HPE. We are therefore able to engage with and deploy multiple meanings to make sense of what the propositions might mean for pedagogy, curriculum, and assessment in HPE. Individually we vary with regards to the discourses we draw upon and resources we have to engage with the propositions, but what has emerged through this research process, is the value and ‘power’ of combining those discourses and resources in imaginative ways.

Foucault (Citation1978) carefully points out that power is not merely a mode of subjugation, a method of ensuring subservience or system of domination of one group over another, it can also be productive and is not simply oppressive or repressive. A Foucauldian understanding of power considers it to be neither institutional or structural, nor a particular kind of strength. Rather power, in the Foucauldian sense, is a network of relationships, and power is a word which ‘one attributes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society’ (Foucault, Citation1978, p. 93). Critically, it is power understood in this way that is integral to Ball et al.’s (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) and Braun et al.’s (Citation2011) articulation of policy actor-context dynamics and that enables us to move beyond the dichotomous logic that is so often read into both power and policy. This is particularly important in the context of policy enactment where ‘teacher’, ‘student’, ‘school’, ‘academic’ identities are advocated by, and through policy politics and processes that give the appearance of rendering a range of actors relatively powerless (Kirk & Macdonald, Citation2001).

‘Concern and loss’

P2: … [the propositions] are in danger of being completely overlooked in many readings of the curriculum … I think it’s important that we don’t slip into paying lip-service to them or taking a checklist approach

Given the history of ‘creative non-implementation’ (Ball, Citation1994, p. 20) in contexts of national curriculum reforms, it is unsurprising that a key discourse to emerge from our musings is one of ‘concern’. This centres on our consistent and shared view that the likelihood of meaningful engagement with the propositions is low. This is in part due to the complexities of interpretation (meanings, language – knowledge) but is also strongly related to teacher starting points, skills, inclinations, values and theoretical perspectives; as well as the contextual realities of schools and schooling (Ball et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b).

P3: My main concern is in moving away from the definitions of these terms and towards the translation of them to practice. Modelling how they look and work as opposed to defining and describing

Our concerns lie within the teacher and their context and a prediction that there is an inevitability that enactment in many instances equating to surface readings, minor tweaks, minimal change, the maintenance of what is ‘known’/safe practice, in short reinforcing the status quo.

P4: I think if we look at the fate of similar approaches OS [overseas] (e.g. NCPE [National Curriculum Physical Education] in UK) I think there is a real chance they will get lost

We anticipate that things, including the generative potential of engaging and talking with each other, the depth and possibilities of each proposition, and the interrelated nature of the propositions, will likely be ‘lost in translation’. We hold these concerns in our own work as well.

P1: There are uncertainties about the extent to which I can make these explicit and alive in the classes I take

‘Hope and resistance’

P2: I’d emphasise the strength of the propositions as a basis of a professional philosophy that can stand the test of time and will be relevant across variations in curriculum throughout Australia and over time

Foucault (Citation1978, p. 95) contends that ‘where there is power, there is resistance’ because of the ‘relational character of power relationships’. For Foucault resistance is never exterior to power, and so by refusing to separate resistance from power Foucault initiates multiple points of resistance from within the system. Following this we maintain that policy actors, including ourselves regularly stand in resistance to power.

P1: The propositions present a unique approach that gives opportunities to impact the ways in which curriculum gets interpreted and enacted

Our hope therefore, springs from optimism associated with the realisation of the possibilities of what the AC HPE could become and mean in practice. In this state of becoming resistance is essential to realising hope, in part because dominant features and structures of the official text could very easily push enactment in different directions and/or reaffirm the status quo in HPE pedagogy. We are resisting by working hard to counter versions of policy enactment that may reconstitute and reinforce established practices that we are concerned to challenge.

P4: Whilst I acknowledge that policy is not constant, and that aspects of curriculum may have limited influence on teachers’ practice, I feel that these … [propositions] can allow for HPE to go beyond sport and competitive team games

Collectively we rest our hopes on the enduring nature of the propositions amidst ongoing policy change. In remaining cognisant that teachers’ fears around curriculum reforms coming and going limits both engagement and enactment, we regard the propositions as a framework that will stand the test of time and prospectively, therefore have a sustained influence on pedagogy, regardless of future government changes and associated shifts in priorities. The fact that the propositions are unlikely to be the focus of future curriculum changes, and the capacity that they have to support and generate multiple meanings in and through multiple contexts, are key strengths in this regard.

P3: I feel that [our students] will get a deeper appreciation of ‘how’ to teach in empathetic and human ways as opposed to just delivering content

On another level, we are hopeful that when teachers engage with the propositions, issues of equity cannot be avoided, because of the questions and issues the propositions generate around/for teaching, learning, and assessment. We see it as our job to resist simplistic readings of the propositions and promote greater awareness of their links to equity.

Conclusion

The research reported in this paper was undertaken amidst recognition of the significant potential that the propositions incorporated into the AC HPE present for innovation in HPE curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. Our data and discussion speaks strongly to teacher educators being key actors in the realisation of this potential. In pursuing the conceptualisation of teacher educators as policy actors, and more particularly, entrepeneurs and provocateurs, this research has sought to shed fresh light on teacher educators’ purposeful work with and amidst policy. Alongside this, the project has illustrated a collaborative, generative process that could be applied by other teacher educators internationally facing similar challenges and possibilities of working amidst major curriculum reform. Our research thus opened up a set of recontextualised complexly encoded texts (Braun et al., Citation2011) to honesty, scrutiny and most importantly, non-threatening interpretation and translation. At the same time, it was a process that reaffirmed the need for teacher educators to engage with multiple interpretations and thereby develop enhanced capacity to initiate important policy conversations with colleagues, teachers and teacher education students. The project has heightened our awareness of the different ways in which we variously engage with a new curriculum, the responsibilities and possibilities associated with doing so, and the value of committing to a process designed to both expose and extend our curriculum understandings.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible as the result of a twelve-month Moansh Education Academy (MEA) Better Teaching Better Learning (BTBL) small grant awarded in 2015. The contribution to the project from our two colleagues and co-researchers Dr Laura Aflrey and Dr Justen O’Connor is also acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Karen Lambert http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7406-4013

Dawn Penney http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2000-8953

References

- Alfrey, L., & Brown, T. D. (2013). Health literacy and the Australian curriculum for health and physical education: A marriage of convenience or a process of empowerment? Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 159–173. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.805480

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2018a). Australian curriculum health and physical education (v 8.4). Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/health-and-physical-education/

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2018b). Australian curriculum health and physical education: Key ideas. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/health-and-physical-education/key-ideas/

- Ball, S. J. (1994). Education reform: A critical and post-structuralist approach. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Ball, S. J. (1998). Big policies/small world: An introduction to international perspectives in education policy. Comparative Education, 34(2), 119–130. doi: 10.1080/03050069828225

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011a). Policy actors: Doing policy work in schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 625–639. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2011.601565

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011b). Policy subjects and policy actors in schools: Some necessary but insufficient analyses. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 611–624. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2011.601564

- Braun, A., Ball, S., Maguire, M., & Hoskins, K. (2011). Taking context seriously: Towards explaining policy enactments in the secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 585–596. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2011.601555

- Brown, T. D. (2013). ‘In, through and about’ movement: Is there a place for the Arnoldian dimensions in the new Australian curriculum for health and physical education? Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 143–157. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.801107

- Costantino, T. E. (2008). Dialogue. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research (Vol. 213). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/10.4135/9781412963909.n109

- Dinan Thompson, M. (2013). Claiming ‘educative outcomes’ in HPE: The potential for ‘pedagogic action’. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 127–142. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.801106

- Eisenhardt, K. M., Graebner, M. E., & Sonenshein, S. (2016). Grand challenges and inductive methods: Rigor without rigor mortis. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1113–1123. doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.4004

- Foucault, M. (1978). The will to knowledge: The history of sexuality volume one. New York: Pantheon Books. R. Hurley, Trans.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury.

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. doi:10.1177/10944281124521 doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151

- Hickey, C. J., Kirk, D., Macdonald, D., & Penney, D. (2014). Curriculum reform in 3D: A panel of experts discuss the new HPE curriculum in Australia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 5(2), 181–192. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2014.911057

- Kirk, D. (2010). Physical education futures. London: Routledge.

- Kirk, D. (2014). Making a career in PESP in the corporatized university: Reflections on hegemony, resistance, collegiality and scholarship. Sport Education and Society, 19(3), 320–332. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2013.879780

- Kirk, D., & Macdonald, D. (2001). Teacher voice and ownership of curriculum change. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 33(5), 551–567. doi: 10.1080/00220270010016874

- Lambert, K. (2018a). Practitioner initial thoughts on the role of the five propositions in the new Australian curriculum health and physical education. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, doi: 10.1080/25742981.2018.1436975

- Lambert, K., & O’Connor, J. (2018b). Breaking and making curriculum from inside ‘policy storms’ in an Australian pre-service teacher education course. Curriculum Studies, doi: 10.1080/09585176.2018.1447302

- Leahy, D., O'Flynn, G., & Wright, J. (2013). A critical ‘critical inquiry’ proposition in health and physical education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 175–187. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.805479

- Macdonald, D. (2013). The new Australian health and physical education curriculum: A case of/for gradualism in curriculum reform? Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 95–108. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.801104

- Macdonald, D., Hunter, L., Carlson, T., & Penney, D. (2002). Teacher knowledge and the disjunction between school curricula and teacher education. Asia-pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 30(3), 259–275. doi: 10.1080/1359866022000048411

- MacInnis, C., & Portelli, J. P. (2002). Dialogue as research. Journal of Thought, 37(2), 33–44. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/42590273

- Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Ball, S. (2015). ‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’: The social construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(4), 485–499. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2014.977022

- McCuiag, L., Quennerstedt, M., & Macdonald, D. (2013). A salutogenic, strengths-based approach as a theory to guide HPE curriculum change. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 109–125. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.801105

- Penney, D. (2013). From policy to pedagogy: Prudence and precariousness; actors and artefacts. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(2), 189–197. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.808154

- Penney, D. (2018). Health and physical education: Transformative potential, propositions and pragmatics. In A. Reid & D. Price (Eds.), The Australian curriculum: Promises, problems and possibilities (pp. 103–114). Deakin West, ACT: ACSA.

- Savage, G. C. (2018). A national curriculum in a federal system? Historical tensions and emerging complexities. In A. Reid & D. Price (Eds.), The Australian curriculum: Promises, problems and possibiltiies (pp. 241–252). Deakin West, ACT: Australian Curriculum Studies Association.

- Savage, G. C., & O’Connor, K. (2015). National agendas in global times: Curriculum reforms in Australia and the USA since the 1980s. Journal of Education Policy, 30(5), 609–630. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2014.969321

- Wright, J. (2014). The role of the five propositions in the Australian curriculum: Health & physical education. Active & Healthy Magazine, 21(4), 5–10.

- Yom, S. (2015). From methodology to practice: Inductive iteration in comparative research. Comparative Political Studies, 48(5), 616–644. doi: 10.1177/0010414014554685