ABSTRACT

Physical education (PE) has significant potential to shape how young people experience their own and others’ bodies. This potential has not always been realized in positive ways and some research suggests that experiences in PE have contributed to young people’s dissatisfaction with their appearances. The broad aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive understanding of body image as a pedagogical issue within PE. A narrative approach to the review is adopted that enables us to summarize, compare, explain and interpret various types of research relevant to our aim. From the databases ERIC, SCOPUS and PsycInfo, 25 articles were identified that deal with either body image in typical PE lessons or researcher-led attempts to influence students’ body image (what we have termed ‘pedagogic interventions’). Main findings are that: (1) PE has been presented as both part of the cause and a potential site of intervention to the problem of negative body image; (2) Researchers have based pedagogic interventions on four types of guiding principles; and (3) Researchers have made an array of recommendations for practitioners relating to gender, time, professional development and the characteristics of the pedagogical interventions. Findings are discussed in relation to broader research on body image in society and in PE with a focus on how the findings might inform further scientific practice.

Introduction

Physical education (PE) has significant potential to shape how young people experience their own and others’ bodies (Azzarito & Katzew, Citation2010; Kerner et al., Citation2018). This potential has not always been realized in positive ways and a considerable amount of research suggests that PE experiences have contributed to a global trend of body dissatisfaction (Doolittle et al., Citation2016; Nutter et al., Citation2019; Tinning, Citation1985). Various reasons have been proposed for the school subject’s negative impact with explanations centring on dominant discourses related to health and fitness in PE (Rich et al., Citation2015; Wright, Citation2000a). These discourses assign value to slim, toned bodies and underscore individuals’ responsibility for attaining such bodies (Crawford, Citation1980). According to a number of PE scholars, health and fitness discourses have helped produce hierarchies of bodies and have resulted in feelings of shame, embarrassment and discontent for many students (Kirk, Citation1990; Varea, Citation2014).

Recent research suggests that some physical educators are sensitive to the effects the school subject can have on young people’s understandings of bodies (Barker et al., Citation2021). A growing number of investigations have also examined how PE practices can be modified to improve young people’s body images (Oliver & Lalik, Citation2000). Further, several relatively recent reviews on topics related to body image in PE exist. Kerner et al. (Citation2018), for example, focus on body image disturbances in PE from a psychological perspective. Sabiston et al. (Citation2019) offer a useful review of body image in the context of physical activity and sport. And Aartun et al. (Citation2022) examine pedagogical aspects of embodiment in general. This paper complements these earlier reviews by focusing on recent investigations that deal specifically with pedagogical issues connected to body image in PE. The aim of the review is to provide a comprehensive understanding of body image as a pedagogical issue within PE. In addressing this aim, our intention is to prompt theoretical and methodological reflection and stimulate productive new approaches to the issue.

Body image in society and in PE

The term ‘body image’ appeared in scientific literature in the mid-twentieth century. Schilder (Citation1950) defined body image as ‘the picture of our own body which we form in our mind, that is to say, the way in which the body appears to ourselves’ (p. 11). As a theoretical construct, ‘body image’ has been used in the field of psychology largely in Schilder’s sense – to indicate that an individual’s experience of their appearance may not match the social ‘reality’ of their appearance (Cash, Citation2004). Cash (Citation2004) provides an expanded definition, suggesting that body image can be thought of as a ‘multifaceted psychological experience of embodiment [and] one’s body-related self-perceptions and self-attitudes’ (p. 1). Despite developing within psychology, the term has been used in different arenas, including clinical practice and schools, and has taken on differing meanings in these arenas. An emphasis on psychological aspects has resulted in criticism, including suggestions that the concept of body image is to an extent, individualistic, moralized and instrumental (Wolszon, Citation1998). Despite varying connotations and closely related terms (McCabe & Ricciardelli, Citation2004), ‘body image’ has been consistently associated with body weight and shape (Wright & Leahy, Citation2016). Our intention in this paper is to hold on to the term in a flexible and reflective way. We acknowledge that body image has taken on varying meanings in various discursive constellations, and we attempt to illustrate some of this variation in the second half of the paper.

In terms of the societal significance of body image, statistical research suggests that many people do not feel particularly comfortable in their bodies. Research has shown that around 50% of 13-year-old American girls reported being unhappy with their body, and that this number grew to nearly 80% by the time girls reached 17 years of age (Kearney-Cooke & Tieger, Citation2015). In a sample of 160 African American adult women, 47% were dissatisfied with their body, 11% felt that they were unattractive, and 75% were somewhat unsatisfied with their weight (Jackson et al., Citation2014).

While much body image scholarship has focused on women, the significance of body image to men and boys has also been recognized for some time. In an investigation of French university students, more than 85% of male participants were dissatisfied with their muscularity (Valls et al., Citation2014), and among 15,624 American high school students, 30% of males reported a desire to gain muscularity (Nagata et al., Citation2019). Scholars have noted that irrespective of gender, body dissatisfaction can have numerous negative consequences. These include eating and exercise disorders (McLean & Paxton, Citation2019), muscle dysmorphia (Tylka, Citation2011) and the consumption of dangerous substances, such as steroids (Bonnecaze et al., Citation2020), laxatives and diuretics (Ferreira da Silva et al., Citation2020).

Body image has been a central issue within PE largely because of the centrality of bodies within the school subject (Armour, Citation1999; Kirk, Citation2002; Tinning, Citation2010). Some PE syllabi include ‘body image’ or related terms such as ‘body ideals’ or ‘identity’ as a specific content. For example, in the Swedish context in which we are working, the curriculum for upper secondary school states that PE should help students to learn about the ‘characteristics and consequences [of] different body ideals’ for health and wellbeing (Skolverket, Citation2011). On the other side of the world, the New South Wales syllabus in Australia emphasises critically analysing information from media messages, such as body image, fad diets and appearance, and students should examine ‘the impact that body image and personal identity have on young people’s health’ (NSW Education Standards Authority [NESA], Citation2018). The New Zealand Curriculum for Health and Physical Education states that pupils aged 15–16 will ‘critically evaluate societal attitudes, values, and expectations that affect people’s awareness of their personal identity and sense of self-worth in a range of life situations’ (NZ Ministry of Education, Citation2014).

While body image has become a curricular issue in some countries recently, historically PE theorists have been concerned to identify the implicit or ‘hidden’ work that the school subject achieves on bodies (Kirk, Citation1990; Citation1993). In the 1980s, Tinning (Citation1985) proposed that by advocating health and fitness principles, physical educators may contribute to a ‘cult of slenderness’. Later, scholars issued similar cautions. Laker (Citation2006), for example, pointed out that attitudes towards bodies are reflected in the teaching of PE and health (see also Quennerstedt, Citation2019), while O’Dea and Abraham (Citation2001) claimed more directly that PE teachers may inadvertently do more harm than good when attempting to educate adolescents about bodies. Around the same time, Wright (Citation2000b) proposed that physical educators should pay close attention to the kinds of fitness and health activities that they promote and the forms of embodiment they produce. More recently, Tinning (Citation2010, p. 110) claimed that ‘[t]here is no doubt that the body (or more specifically the firm, slender body and its antithesis – the fat/obese body) has become a central focus of our field’ (see also, Varea, Citation2014).

In short, young people’s understandings of their own and others’ bodies have often been framed as deleterious. Earlier PE scholarship suggested the school subject did little to remedy the situation, despite placing the body in the centre of pedagogical practices. Indeed, many scholars suggested that rather than facilitate critical, reflective understandings of bodies, PE may well have compounded the problem by promulgating simplistic notions of health and fitness (see also Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; van Amsterdam & Knoppers, Citation2018). In this review, we are interested in scholarship that examines body image and pedagogical practices in PE. The aim of the review is to provide a comprehensive understanding of body image as a pedagogical issue within PE. In the following section, we describe how we approached this task.

Methods

To address our aim, we adopted a narrative review approach. A narrative approach involves summarizing, comparing, explaining and interpreting various types of research relevant to a particular question or aim (Mays et al., Citation2005). In a narrative review – as in other types of interpretive review – the essential tasks comprise induction and interpretation of literature (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2005). Narrative reviews are less concerned with assessing the quality of evidence than systematic reviews (Mays et al., Citation2005) and are particularly useful when the main aim is not simply to convert research results into a common metric (Snilstveit et al., Citation2012).

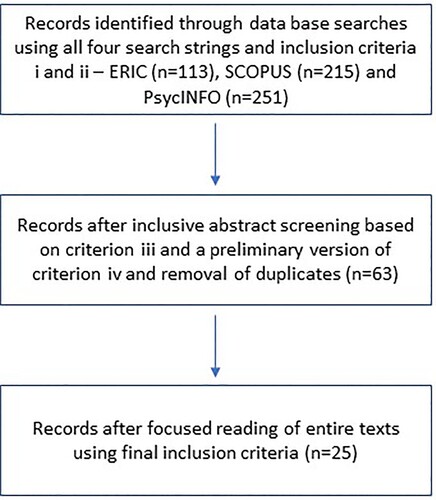

Literature searches were performed in June 2021 in the databases ERIC, SCOPUS and PsycINFO. Databases with diverse audiences were used since our ambition was to gather research that dealt with individuals’ experiences of their bodily appearances (Cash, Citation2004) in PE settings within different disciplines. The search strategy combined search terms that were developed in line with the specific aim of our investigation. Since a number of texts with ‘body image’ in the title or abstract referred to ‘body ideals’ in the main text, the term ‘body ideals’ was added. This move accorded with the presence of the term ‘body ideals’ in curricula (Skolverket, Citation2011) and we anticipated that by including ‘body ideals’, we might find socio-culturally oriented literature about students’ experiences of their appearances. Ultimately, four search strings were employed.

‘Physical education’ AND ‘body image’ AND (‘pedagogy’ OR ‘teach*’ OR ‘learn*’);

‘Physical education’ AND ‘body ideals’ AND (‘pedagogy’ OR ‘teach*’ OR ‘learn*’);

‘Physical education’ AND ‘body image’ AND (‘module’ OR ‘curriculum’ OR ‘unit’ OR ‘intervention’), and;

‘Physical education’ AND ‘body ideals’ AND (‘module’ OR ‘curriculum’ OR ‘unit’ OR ‘intervention’) (see , below).Footnote1 The search involved academic journal articles as defined by each database published after 2011, giving a 10-year reviewing period. The time frame was chosen to provide a picture of the field in which significant changes have taken place, notably the emergence of body positivity/acceptance movements (Mahlo & Tiggemann, Citation2016), increasing criticality in schools (Azzarito et al., Citation2016) and the expanding influence of social media on topics related to body image (Goodyear et al., Citation2022).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) published between 2011 and June 2021; (ii) published in an academic journal as defined by each database; (iii) includes empirical material (review and methodological papers were excluded), (iv) focuses on body image in school PE. Articles focusing on after school programmes, university programmes, or sport programmes were excluded. Articles that focused on PE as part of a wider school approach were included. An initial selection was carried out by the first and third authors using the results of the search strings with each database. In this step, the first and third authors read the abstracts of the articles and using inclusion criterion (iii) and a preliminary version of inclusion criterion (iv), decided whether the articles were potentially relevant to the aim of the review. The preliminary version of criterion (iv) was that articles needed to focus on a pedagogic intervention. During selection however, we decided to include naturalistic articles (i.e. investigations of PE in its current or traditional form) as these could also help to address our first and third analytic questions (see below). Initial selection was conducted inclusively and if any doubt existed, the paper was included. Duplicate articles were removed as the first and third authors conducted the searches in each database. The article abstracts from the initial selection process (n = 63) were sent to the other co-authors. After reading entire texts, each co-author proposed a final selection list. Through dialogue, the authors then agreed to modify inclusion criterion (iv) and include naturalistic investigations, and remove articles that did not clearly meet all four criteria (removed articles: n = 38). The final sample consisted of 25 articles which are listed in the ‘Findings’ section.

Once the final sample had been determined and in line with our attempt to synthesize various types of evidence, a narrative analytic procedure was adopted (Snilstveit et al., Citation2012). Following Juntunen and Lehenkari (Citation2021), our review process involved four steps. First, we read and re-read the selected articles. Second, we systematically extracted information relevant to our aim. Here, we used three specific analytic questions that we developed reflexively as we read and discussed the literature together: (i) How have researchers formulated the relationship between body image and PE? (ii) What types of approaches have been used to address body image in PE? and (iii) What recommendations have researchers made for teachers? These questions helped us to maintain our focus on pedagogy and since responses to these questions could be found across the literature, they facilitated synthesis of the research corpus as a whole. Information corresponding to each analytic question was identified and copied into three separate Microsoft Word documents. Third, we searched within each document for recurring themes in an inductive manner. The results of this third step are presented in the ‘Findings’ section. In our fourth and final step, we developed an interpretation of the findings. This last step involved abstraction and was facilitated through discussion between the authors about how the findings related to other PE research. This interpretation is presented in the ‘Discussion’ section.

Findings

A summary of the literature’s general characteristics is presented in . A more detailed presentation of our findings is included in three subsections that align with our analytic questions. Findings from research based on naturalistic approaches (12 articles) appear predominantly in the first and third subsections while research that involves the implementation of pedagogic interventions (13 articles) appears across all three subsections.

Table 1. Summary of the literature’s general characteristics.

The relation between body image and PE

Researchers examining body image and school PE in the last decade have tended to see body image as: (i) reflexive, in that it involves viewing oneself from an external point of view (Cox et al., Citation2017; Grosick et al., Citation2013; Robertson & Thomson, Citation2014); (ii) problematic for school students due to bodily changes accompanying puberty (Carmona et al., Citation2015); and (iii) influenced by family, friends and media, though media has been seen as most significant (Carmona et al., Citation2015; Cox et al., Citation2017). Amongst other influences, schools (Robertson & Thomson, Citation2014; Yager et al., Citation2019) and PE specifically (Catunda et al., Citation2017) have been presented as uniquely suited to improving young people’s body images. Two reasons have been offered to support this contention: PE curricula already have a focus on health and the body (Öhman et al., Citation2014), and PE is part of mandatory schooling and consequently can ‘reach’ many young people (Catunda et al., Citation2017).

Despite its apparent suitability as a site of intervention, PE is frequently presented as a context in which students learn to negatively evaluate their bodies (Carmona et al., Citation2015; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015). Researchers have noted practical issues in PE that can impact on students’ body image, for example, that bodies are often on display (Ballı et al., Citation2014) and that the need for changing and/or showering can result in body-related bullying (Lodewyk & Sullivan, Citation2016). Others have pointed to the role of the teacher, suggesting that PE teachers often hold fat biases (Carmona et al., Citation2015; Robertson & Thomson, Citation2014). Olive and colleagues (Citation2019) draw attention to elementary school teachers but suggest that it is an absence of professional development opportunities rather than fat bias that limits their ability to work with body image.

The most widely cited explanation for PE’s negative influence on students’ body image concerns cultural discourses that are seen to permeate all aspects of PE (Walseth et al., Citation2017). Scholars have underscored the significance of healthism (Wiltshire et al., Citation2017) and the ways in which ideas about weight and physical activity have been at the fore of PE practices (Beltrán-Carrillo et al., Citation2018; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015). Healthism locates responsibility for weight and physical inactivity with the individual, creating shame and perceptions of difference (Johnson et al., Citation2013). Johnson et al. (Citation2013) ascribe teachers some blame (see Carmona et al., Citation2015; Robertson & Thomson, Citation2014) but contend that the problem runs far deeper than lack of training or personal bias. Azzarito et al. (Citation2016) add that fitness-driven PE curricula are often gender- and racially-normative and therefore have ‘potentially damaging consequences for the ways that young people view, understand, and act on their bodies’ (p. 54).

Types of approaches used to address body image in PE

Given that PE has been identified as an ideal site to work with body image but that it has also been criticized for negatively impacting young people’s body image, it is not surprising that researchers have attempted to develop pedagogic interventions that can be used to improve PE practices. These interventions can be broadly grouped according to their guiding principles: (i) interventions based primarily on cognitive and/or behaviourist principles (four articles), (ii) interventions based primarily on embodied principles (three articles), (iii) interventions based primarily on principles of critical reflection (three articles) and (iv) interventions based primarily on the idea that increased physical activity leads to improved body image (three articles).

The four cognitive and/or behaviourist interventions assume that providing students with information about topics such as body image, performance enhancing drugs and physical activity will alter students’ understandings of the world (cognitive effect) and lead to improved body image and behaviours deemed to be healthy (behavioural effect) (Annesi et al., Citation2015; Yager et al., Citation2019). The logic is essentially that knowledge will affect desire and intention, which in turn, will affect behaviour (Yager et al., Citation2019). Sundgot-Borgen and colleagues’ (Citation2018, Citation2019) main aim was cognitive, in that they tried to ‘change attitudes, beliefs and knowledge to combat the internalization of sociocultural ideas about body shape’ (Sundgot-Borgen et al., Citation2018, p. 5). It is not uncommon for cognitive/behaviourist interventions to be based on multiple psychological and medically oriented theories. Sundgot-Borgen and colleagues (Citation2018) drew on positive psychology, an aetiological model of risk and protective factors, and the elaboration likelihood model. The ‘elaboration likelihood model’ suggests that repeated exposure to a message increases the likelihood that the message will be remembered (Sundgot-Borgen et al., Citation2018).

The three interventions primarily based on embodied principles assume that by immersing themselves in the movement experience, students can re-orient their attentional focus and become more connected with their bodies. Both Halliwell et al. (Citation2018) and Cox et al. (Citation2017) introduced yoga activities within PE curricula with the aim of increasing students’ feelings of ‘competence and empowerment’ (Halliwell et al., Citation2018, p. 196). Relating to a different movement culture, Baena-Extremeraet al. (Citation2012) also invited students to focus on their subjective experiences. In these researchers’ investigation, an adventure education programme was used in an attempt to improve self-concept and self-esteem. In contrast to cognitive/behaviourist interventions, teachers using embodied interventions did not explicitly teach about body image but attempted to influence students’ body images through experiences.

A third group of interventions aims primarily to help students critically reflect on bodies and body ideals. These three interventions are concerned with helping students evaluate societal messages about bodies and – based on some form of critical theory – assume that cultural stereotypes are potentially harmful. Azzarito et al. (Citation2016), for example, implemented a ‘Body Curriculum’ informed by the feminist theory which aimed to help young people ‘critically deal with the media narratives of perfect bodies they consume in their daily lives’ (p. 54). The intervention was not entirely media-focused, and students also explored their embodied identities in relation to cultural narratives. Schubring et al.’s (Citation2021) intervention also concentrated on body ideals. As in Azzarito and colleagues’ (Citation2016) work, students reflected on their relationships to cultural norms (see also McHugh and Kowalski’s (Citation2011) work with young Canadian aboriginal women). In critical reflection interventions, body image and related themes were discussed and dealt with explicitly.

Finally, three interventions are based on the idea that increasing student physical activity levels will improve their body image (Bonavolontà et al., Citation2021). This idea is supported by research that suggests that people who are more physically active have more positive images of their bodies (Fernández-Bustos et al., Citation2019).Footnote2 Following this notion, Bonavolontà et al. (Citation2021) provided students with walking and running exercises in PE lessons (see also, Catunda et al., Citation2017), while Olive and colleagues’ (Citation2019) research involved increasing pupils’ participation in PE in grades 3–6 through an emphasis on inclusivity and enjoyment, and a decreased emphasis on competition. In physical activity interventions, as in the interventions based on embodied principles, teachers tended not to teach about body image directly, but instead tried to influence students’ body images through increased physical activity.

Recommendations for teachers/practitioners

Researchers gleaned practical insights and provided many pedagogical recommendations. The most persistent recommendation – regardless of whether the research involved an intervention or was based on current practice – is for PE teachers to recognize differences between boys and girls (Ballı et al., Citation2014; Grosick et al., Citation2013; Olive et al., Citation2019). Recognizing differences can mean addressing boys’ and girls’ needs separately (Lodewyk & Sullivan, Citation2016) or ensuring that male and female students are catered for within co-educational classes (Sundgot-Borgen et al., Citation2019). Walseth et al. (Citation2017) proposed that even though the girls in their investigation wanted more fitness and less sport in PE, a desire for more fitness may be the result of traditional (and disempowering) femininity norms. They consequently recommended that teachers remain cognizant of gender norms. Wiltshire et al. (Citation2017) suggest that teachers need to be sensitive to student diversity more broadly and avoid activities that emphasize distinctions in physical capital.

Scholars have made a range of recommendations regarding the characteristics of pedagogical interventions. Many of these recommendations relate to timing and/or duration. Halliwell et al. (Citation2018), for example, proposed that schools need to begin in elementary school years. This recommendation is noteworthy given that most innovations were conducted with students aged 12 and over (see ). Others have focused on the duration of interventions. Annesi et al. (Citation2015), for instance, maintained that five lessons were probably too many while Azzarito et al. (Citation2016) claimed that seven lessons were too few, a claim supported by McHugh and Kowalski (Citation2011). Along with timing and duration, scholars have raised the issue of student involvement. Active participation and the need to involve students in development and implementation appear to be important (McHugh & Kowalski, Citation2011; Schubring et al., Citation2021), as does providing students with feelings of competence (Beltrán-Carrillo et al., Citation2018; Catunda et al., Citation2017).

Professional development opportunities for teachers constituted a recurring theme whether the investigation contained an intervention or not. Several texts implied that either teachers are insufficiently skilled when it comes to addressing body image or body image is a particularly challenging topic to work with (Beltrán-Carrillo et al., Citation2018; Olive et al., Citation2019). Robertson and Thomson (Citation2014) suggested that teachers need support to develop criticality and the ability to interrupt norms in their lessons. In a slightly different vein, Schubring et al. (Citation2021) proposed that teachers need to consider how their own embodiment relates to their professional identities and practices. According to these scholars, self-awareness gained from reflection-based professional development may facilitate more sensitive pedagogies (see also, Öhman et al., Citation2014).

Discussion

In line with our focus on researching pedagogical practices, we want to consider insights that researchers might gain from the findings. First, we want to draw attention to how body image is framed as a problem and simultaneously how solutions are construed. There is considerable agreement concerning the nature of the problem, agreement that is contiguous with earlier PE research (O’Dea & Abraham, Citation2001; Wright, Citation2000b). The problem is that ‘society’ convinces young people that their bodies are somehow incorrect or flawed (Catunda et al., Citation2017). This transmission formulation places responsibility on others – ‘family’ and ‘peers’, or more often, ‘the media’ (Grosick et al., Citation2013). By locating the problem with these entities, researchers frame children and adolescents as naïve, and ignore young people’s agency in constructing norms and ideals. An alternative reading which tallies with Azzarito et al.’s (Citation2016) suggestion that adolescents struggle to free themselves from cultural ideals, is that young people are actively entangled in the construction of body ideals and have stakes in how bodies are perceived. Many work on their waistlines or biceps to gain the capital to which Powell and Fitzpatrick (Citation2015) and Wiltshire and colleagues (Citation2017) refer. In fact, the notion of capital reveals a line of difference that separates the approaches to body image adopted within the literature reviewed here: those investigations that are based on an implicit acceptance of body norms and that aim to help students gain capital by conforming to those norms through physical activity and those that are based on a rejection of body norms and that aim to help students deviate from those norms through either increased knowledge and behavioural strategies, redirected focus or critical reflection.

While there is consensus concerning the problem, scholars have presented – at times vastly – different solutions (compare Cox et al., Citation2017, for example, with Olive et al., Citation2019). We have specified four types of pedagogical intervention. An obvious question for researchers is, ‘which type is most effective in bringing about positive body image?’ This question is, nevertheless, complicated. From a quantitative methodological perspective, there is an insufficient number of investigations in each category and too great a variety of empirical material to allow for generalized conclusions (Snilstveit et al., Citation2012). From our narrative perspective, we are more inclined to point out that while different types of interventions have been used in PE to address body image, each has a different solution in view. Embodied interventions aim, for example, to produce students who concentrate on the subjective experience of moving (Baena-Extremera et al., Citation2012; Halliwell et al., Citation2018). Physical activity interventions in contrast aim to produce students who are committed to being physically active (Annesi et al., Citation2015; Catunda et al., Citation2017). In an important sense, improved body image is not the immediate goal of any of the interventions, but an ancillary outcome of the pedagogical work undertaken. It is difficult to pinpoint factors that determine the principles used to guide pedagogical interventions, but our impression is that researchers’ theoretical and methodological assumptions have as much impact as the official curricular or practical context into which they enter. The issue of researcher reflexivity has received scant consideration, and in our view, warrants further attention.

It is rather late in the piece, but it is worth asking whether ‘improving students’ body image’ is an educational aim. On one hand, body image can be described as an aspect of psychological wellbeing (Ballı et al., Citation2014) and influencing students’ body images can more accurately be described as public health intervention than pedagogical work. At the same time, if simply being in PE lessons does, as scholars have suggested, affect how students understand themselves and their bodies regardless of intended educational aim (Kirk, Citation1993; Tinning, Citation2010), then a distinction between educational and public health outcome becomes somewhat arbitrary. Following Wright (Citation2000b), our recourse for researchers and pedagogues is to ask, ‘what do students stand to learn about their bodies in any given situation?’ This question in our view, encourages physical educators to maintain a broad and circumspect focus on what students can learn about bodies during pedagogical interventions (see Aartun et al., Citation2022, for more discussion of this issue).

From a research point of view, it is useful to consider the taken for granted assumptions in this literature. Much of this corpus frames body image as a ‘trait’ that one has (see Kerner et al., Citation2018; see also Johnson et al., Citation2013; McHugh & Kowalski, Citation2011, for exceptions). This assumption is contingent on the epistemological and methodological principles of post-positivist sciences on which many of the investigations are based, principles related for example, to the reification and measurement of body image at different time points (Fernández-Bustos et al., Citation2019; Halliwell et al., Citation2018; Sundgot-Borgen et al., Citation2019). While PE may have been heavily influenced by the natural sciences (Aartun et al., Citation2022), physical educators are bound neither in practice, nor in principle to the same epistemological and methodological rules as researchers. It may thus be the case that research-driven interventions diverge from the ordinary epistemologies and pedagogies of practitioners (see Barker et al., Citation2021). Our sense is that it is useful for physical educators to remain open to the possibility that students can ‘try on’ different views of their selves and that their views may change according to the contexts in which they find themselves (Kerner et al., Citation2018). Working from this standpoint, physical educators may be inclined to work reflectively and critically with body image interventions.

Gender is another area where important assumptions have been made (Kerner et al., Citation2018). In most investigations, gender is divided into two categories and as noted, a recurring recommendation for practitioners is to treat boys and girls differently because they have different ideals in view (Ballı et al., Citation2014; Grosick et al., Citation2013; Olive et al., Citation2019). This recommendation ignores non-binary dimensions to gender and has the potential to exclude how many young people understand themselves. Somewhat paradoxically, it also ignores reciprocal aspects of body image and the possibility that one’s body image may be influenced by how one thinks one is seen by members of another sex. To ignore this reciprocity is to bracket out an important part of the pedagogical situation on which researchers are trying to shed light.

Finally, dissatisfaction and anxiety (Lodewyk & Sullivan, Citation2016; Yager et al., Citation2019) are often presented alongside a pressure to strive for a positive body image (Beltrán-Carrillo et al., Citation2018). The construction of a body image dichotomy on which many individuals sit at the ‘wrong’ end is a recognizable part of a pathogenic approach to health. Like pathogenic thinking in general, it does a great deal to justify intervention, but it also invites a deficit view of individuals. A deficit view can lead to student misrecognition, where teachers assume that students inevitably feel anxious and worried about their bodies. Misrecognition can result in students becoming alienated or disillusioned with forms of PE that lack meaning (Aartun et al., Citation2022) or it can result in students ‘learning’ to be dissatisfied with their bodies. Perhaps even more problematic though is that dichotomous thinking closes down opportunities for thinking about body image (and body ideals) as somewhat positive, simultaneously positive and negative, or neither positive nor negative. Changing one’s body is in our view, not necessarily problematic and may be a source of meaningfulness and joy in one’s life (see Shusterman, Citation2008, for a comprehensive discussion of this theme). One might also be extremely satisfied with aspects of one’s body and not satisfied with others. Current body image research provides few ways to handle such situations (Annesi et al.’s (Citation2015) work constitutes an exception). Alternatively, ‘positive/negative’ or ‘satisfied/dissatisfied’ may not be the most relevant descriptors of one’s relation with one’s self. Feeling ‘curious about’ or ‘committed to’ one’s self might at times say something more insightful about a person than how satisfied they are with their body. And of course, how people feel about themselves is likely to be affected by a range of person- and context-specific factors (relationships, maturity, biographical events, for example) that are beyond the capacities of most educators to discern, let alone control. There is, for this reason, a need to avoid simplifications.

In various ways, this review has showed that bodies are still of primordial importance in PE, whether it is through interventions dedicated to improving body image or through engaging students in critical reflection. The embodied identity of PE (Macdonald & Kirk, Citation1999) continues to be at the heart of the profession. Cautions like the ones proposed by Laker (Citation2006) and O’Dea and Abraham (Citation2001) are still present when it comes to educating students about body image. The main points of concern for researchers centre on how teachers manage the sensitive topic of body image with young people.

Conclusion

The aim of the review has been to provide a comprehensive understanding of body image as a pedagogical issue within PE. In addressing our aim, we first demonstrated how researchers have related body image to PE. Here, we showed how PE has been presented as both parts of the cause and potential remedy to the problem of negative body image with school-aged young people. We then described the approaches that researchers have used to address body image in PE, classifying interventions according to their guiding principles. These included: (i) cognitive and/or behaviourist principles, (ii) embodied principles, (iii) principles of critical reflection and (iv) the principle that increased physical activity leads to improved body image. Finally, we discussed recommendations that researchers have made for teachers/practitioners. We grouped recommendations into three categories relating to gender, the characteristics of the pedagogical interventions and professional development.

We want to finish with one final reflection concerning the implications of our findings for researchers. In some respects, there is an overlap between the concerns of scholars and the concerns of practitioners. That much existing research contains clear demarcations between boys and girls, for example, is of as much interest to researchers attempting to explain the phenomenon of body image as it is to practitioners working with body image in schools. Equally, that most of the body image literature reviewed here frames the topic as something concrete and ignores fluid, transient aspects of body image warrant attention from both practitioners and scholars. In other respects, though, there is a divergence of interests. Scholars specifically can benefit from considering how investigations of body image connect with research from other perspectives and how their own starting assumptions influence the kinds of questions they ask and the kinds of data they generate. We have stressed that the interventions employed in the investigations here are based primarily on diverging principles but there are areas of similarity and potential synergy. We hope that the framework provided for categorizing body image interventions and the points raised in our discussion will provide useful stimuli for dialogue between researchers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The search strings were used ‘in all fields’ except in the SCOPUS searches, where search strings 1 and 3 were used only in the ‘title’, ‘abstract’ or ‘keyword’ fields. The decision to narrow the fields was necessary to make abstract screening possible as there were more than 3000 articles if ‘in all fields’ was used.

2 Note that Fernández-Bustos et al.’s (Citation2019) investigation was naturalistic and did not contain an intervention.

References

- Aartun, I., Walseth, K., Standal, Ø, & Kirk, D. (2022). Pedagogies of embodiment in physical education – A literature review. Sport, Education and Society, 27(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1821182

- Annesi, J. J., Trinity, J., Mareno, N., & Walsh, S. M. (2015). Association of a behaviorally based high school health education curriculum with increased exercise. The Journal of School Nursing, 31(3), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840514536993

- Armour, K. (1999). The case for a body-focus in education and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 4(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357332990040101

- Azzarito, L., & Katzew, A. (2010). Performing identities in physical education: (En) gendering fluid selves. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2010.10599625

- Azzarito, L., Simon, M., & Marttinen, R. (2016). ‘Stop photoshopping!’: A visual participatory inquiry into students’ responses to a body curriculum. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0166

- Baena-Extremera, A., Granero-Gallegos, A., & Ortiz-Camacho, M. (2012). Quasi-experimental study of the effect of an adventure education programme on classroom satisfaction, physical self-concept and social goals in physical education. Psychologica Belgica, 52(4), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-52-4-369

- Ballı, ÖM, Erturan-İlker, G., & Arslan, Y. (2014). Achievement goals in Turkish high school PE setting: The predicting role of social physique anxiety. International Journal of Educational Research, 67, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2014.04.004

- Barker, D. M., Quennerstedt, M., Johansson, A., & Korp, P. (2021). Physical education teachers and competing obesity discourses: An examination of emerging professional identities. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40(4), 642–651. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2020-0110

- Beltrán-Carrillo, V., Devís-Devís, J., & Peiró-Velert, C. (2018). The influence of body discourses on adolescents’(non) participation in physical activity. Sport, Education and Society, 23(3), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1178109

- Bonavolontà, V., Cataldi, S., & Fischetti, F. (2021). Changes in body image perception after an outdoor physical education program. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21, 632–637. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2021.s1074

- Bonnecaze, A. K., O’Connor, T., & Aloi, J. A. (2020). Characteristics and attitudes of men using anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS): A survey of 2385 men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 14(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988320966536

- Carmona, J., Tornero-Quinones, I., & Sierra-Robles, Á. (2015). Body image avoidance behaviors in adolescence: A multilevel analysis of contextual effects associated with the physical education class. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.09.010

- Cash, T. F. (2004). Body image: Past, present and future. Body Image, 1(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1

- Catunda, R., Marques, A., & Januário, C. (2017). Perception of body image in teenagers in physical education classes. Motricidade, 13(1), 91–99.

- Cox, A., Ullrich-French, S., Howe, H., & Cole, A. (2017). A pilot yoga physical education curriculum to promote positive body image. Body Image, 23, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.07.007

- Crawford, R. (1980). Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. International Journal of Health Services, 10(4), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.2190/3H2H-3XJN-3KAY-G9NY

- Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., & Sutton, A. (2005). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal Health Services Research & Policy, 10(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581960501000110

- Doolittle, S. A., Rukavina, P. B., Li, W., Manson, M., & Beale, A. (2016). Middle school physical education teachers’ perspectives on overweight students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0178

- Fernández-Bustos, J. G., Infantes-Paniagua, Á, Cuevas, R., & Contreras, O. R. (2019). Effect of physical activity on self-concept: Theoretical model on the mediation of body image and physical self-concept in adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(1537), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01537

- Ferreira da Silva, A., Seabra Moraes, M., Custódio Martins, P., Valim Pereira, E., Marcio de Farias, J., & Santos Silva, D. A. (2020). Prevalence of body image dissatisfaction and association with teasing behaviours and body weight control in adolescents. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1980-6574202000010198

- Goodyear, V., Andersson, J., Quennerstedt, M., & Varea, V. (2022). #Skinny girls: Young girls’ learning processes and health-related social media. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1888152

- Grosick, T. L., Talbert-Johnson, C., Myers, M. J., & Angelo, R. (2013). Assessing the landscape: Body image values and attitudes among middle school boys and girls. American Journal of Health Education, 44(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2012.749682

- Halliwell, E., Jarman, H., Tylka, T. L., & Slater, A. (2018). Evaluating the impact of a brief yoga intervention on preadolescents’ body image and mood. Body Image, 27, 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.10.003

- Jackson, K. L., Janssen, I., Appelhans, B. M., Kazlauskaite, R., Karavolos, K., Dugan, S. A., Avery, E. A., Shipp-Johnson, K. J., Powell, L. H., Kravitz, H. M. (2014). Body image satisfaction and depression in midlife women: The study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 17(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0416-9

- Johnson, S., Gray, S., & Horrell, A. (2013). I want to look like that’: Healthism, the ideal body and physical education in a Scottish secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 34(3), 457–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2012.717196

- Juntunen, M., & Lehenkari, M. (2021). A narrative literature review process for an academic business research thesis. Studies in Higher Education, 46(2), 330–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1630813

- Kearney-Cooke, A., & Tieger, D. (2015). Body image disturbance and the development of eating disorders. In L. Smolak & M. D. Levine (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of eating disorders (pp. 283–296). Wiley.

- Kerner, C., Haerens, L., & Kirk, D. (2018). Understanding body image in physical education: Current knowledge and future directions. European Physical Education Review, 24(2), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17692508

- Kirk, D. (1990). Knowledge, science and the rise of human movement studies. ACHPER National Journal, 127(7), 8–11.

- Kirk, D. (1993). The body, schooling and culture. Deakin University Press.

- Kirk, D. (2002). Social construction of the body in physical education and sport. In A. Laker (Ed.), The sociology of sport and physical education: An introductory reader (pp. 79–90). Routledge.

- Laker, A. (2006). Book review: Body knowledge and control: Studies in the sociology of physical education and health. European Physical Education Review, 12(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X06065184

- Lodewyk, K. R., & Sullivan, P. (2016). Associations between anxiety, self-efficacy, and outcomes by gender and body size dissatisfaction during fitness in high school physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(6), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2015.1095869

- Macdonald, D., & Kirk, D. (1999). Pedagogy, the body and Christian identity. Sport, Education and Society, 4(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357332990040202

- Mahlo, L., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). Yoga and positive body image: A test of the embodiment model. Body Image, 18, 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.06.008

- Mays, N., Pope, C., & Popay, J. (2005). Details of approaches to synthesis. A methodological appendix to the paper: Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy making in the health field [online]. http://www.google.co.uk/url?a=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CEoQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fciteseerx.ist.psu.edu%2Fviewdoc%2Fdownload%3Fdoi%3D10.1.1.113.2530%26rep%3Drep1%26type%3Dpdf&ei=6FkOUPWlEuHT0QWx4YCQDA&usg=AFQjCNHRxbH1y4UNKCMGS8GjdL5jcfZz3A

- McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2004). Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan: A review of past literature. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(6), 675–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00129-6

- McHugh, T. F., & Kowalski, K. C. (2011). ‘A new view of body image’: A school-based participatory action research project with young Aboriginal women. Action Research, 9(3), 220–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750310388052

- McLean, S. A., & Paxton, S. J. (2019). Body image in the context of eating disorders. Psychiatric Clinics, 42(1), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.006

- Nagata, J. M., Bibbins-Domingo, K., Garber, A. K., Griffiths, S., Vittinghoff, E., & Murray, S. B. (2019). Boys, bulk, and body ideals: Sex differences in weight-gain attempts among adolescents in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.09.002

- New South Wales Education Standards Authority. (2018). Personal development, health and physical education K-10 syllabus. Retrieved September 22, 2021, from https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/learning-areas/pdhpe/pdhpe-k-10-2018

- New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2014). The New Zealand curriculum online. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum/Health-and-physical-education/Achievement-objectives

- Nutter, S., Ireland, A., Alberga, A. S., Brun, I., Lefebvre, D., Hayden, K. A., & Russell-Mayhew, S. (2019). Weight bias in educational settings: A systematic review. Current Obesity Reports, 8(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00330-8

- O’Dea, J., & Abraham, S. (2001). Knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors related to weight control, eating disorders, and body image in Australian trainee home economics and physical education teachers. Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(6), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60355-2

- Olive, L. S., Byrne, D., Cunningham, R. B., Telford, R. M., & Telford, R. D. (2019). Can physical education improve the mental health of children? The LOOK study cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(7), 1331–1340. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000338

- Oliver, K. L., & Lalik, R. (2000). Body knowledge: Learning about equity and justice with adolescent girls. Peter Lang.

- Öhman, M., Almqvist, J., Meckbach, J., & Quennerstedt, M. (2014). Competing for ideal bodies: A study of exergames used as teaching aids in schools. Critical Public Health, 24(2), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.872771

- Powell, D., & Fitzpatrick, K. (2015). ‘Getting fit basically just means, like, nonfat’: Children’s lessons in fitness and fatness. Sport, Education and Society, 20(4), 463–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.777661

- Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Healthying physical education-on the possibility of learning health. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1539705

- Rich, E., De Pian, L., & Francombe-Webb, J. (2015). Physical cultures of stigmatisation: Health policy and social class. Sociological Research Online, 20(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3613

- Robertson, L., & Thomson, D. (2014). Giving permission to be fat? Examining the impact of body-based belief systems. Canadian Journal of Education, 37(4), 1–25.

- Sabiston, C. M., Pila, E., Vani, M., & Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. (2019). Body image, physical activity, and sport: A scoping review. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 42, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.010

- Schilder, P. (1950). The image and appearance of the human body. International Universities Press.

- Schubring, A., Bergentoft, H., & Barker, D. M. (2021). Teaching on body ideals in physical education: A lesson study in Swedish upper secondary school. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 12(3), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2020.1869048

- Shusterman, R. (2008). Body consciousness: A philosophy of mindfulness and somaesthetics. Cambridge University Press.

- Skolverket. (2011). Läroplan, examensmål och gymnasie gemensamma ämnen för gymnasieskola 2011. Skolverket.

- Snilstveit, B., Oliver, S., & Vojtkova, M. (2012). Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 4(3), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2012.710641

- Sundgot-Borgen, C., Bratland-Sanda, S., Engen, K. M., Pettersen, G., Friborg, O., Torstveit, M. K., Kolle, E., Piran, N., Sundgot-Borgen, J., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2018). The Norwegian healthy body image programme: Study protocol for a randomized controlled school-based intervention to promote positive body image and prevent disordered eating among Norwegian high school students. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0221-8

- Sundgot-Borgen, C., Friborg, O., Kolle, E., Engen, K. M., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Rosenvinge, J. H., Pettersen, G., Klungland Torstveit, M., Piran, N., & Bratland-Sanda, S. (2019). The healthy body image (HBI) intervention: Effects of a school-based cluster-randomized controlled trial with 12-months follow-up. Body Image, 29, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.03.007

- Tinning, R. (1985). Physical education and the cult of slenderness: A critique. ACHPER National Journal, 107, 10–14.

- Tinning, R. (2010). Pedagogy and human movement: Theory, practice, research. Routledge.

- Tylka, T. L. (2011). Refinement of the tripartite influence model for men: Dual body image pathways to body change behaviors. Body Image, 8(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.008

- Valls, M., Bonvin, P., & Chabrol, H. (2014). Association between muscularity dissatisfaction and body dissatisfaction among normal-weight French men. Journal of Men’s Health, 10(4), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1089/jomh.2013.0005

- van Amsterdam, N., & Knoppers, A. (2018). Healthy habits are no fun: How Dutch youth negotiate discourses about food, fit, fat, and fun. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 22(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459316688517

- Varea, V. (2014). The body as a professional ‘touchstone’: Exploring Health and Physical Education undergraduates’ understandings of the body [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. University of Queensland.

- Walseth, K., Aartun, I., & Engelsrud, G. (2017). Girls’ bodily activities in physical education: How current fitness and sport discourses influence girls’ identity construction. Sport, Education and Society, 22(4), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1050370

- Wiltshire, G., Lee, J., & Evans, J. (2017). ‘You don’t want to stand out as the bigger one’: Exploring how PE and school sport participation is influenced by pupils and their peers. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(5), 548–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1294673

- Wolszon, L. R. (1998). Women’s body image theory and research: A hermeneutic critique. American Behavioral Scientist, 41(4), 542–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764298041004006

- Wright, J. (2000a). Bodies, meanings and movement: A comparison of the language of a physical education lesson and a Feldenkrais movement class. Sport, Education and Society, 5(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/135733200114424

- Wright, J. (2000b). Disciplining the body: Power, knowledge and subjectivity in a physical education lesson. In A. Lee & C. Poyton (Eds.), Culture and text: Discourse and methodology in social research and cultural studies (pp. 152–169). Allen & Unwin.

- Wright, J., & Leahy, D. (2016). Moving beyond body image: A socio-critical approach to teaching about health and body size. In E. Cameron & C. Russell (Eds.), The fat pedagogy reader: Challenging weight-based oppression through critical education (pp. 141–149). Peter Lang.

- Yager, Z., McLean, S. A., & Li, X. (2019). Body image outcomes in a replication of the ATLAS program in Australia. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 20(3), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000173