ABSTRACT

This study investigates 10th-grade students’ experiences with physical education (PE) units informed by a pedagogical model called the practising model (PM). We apply a theoretical framework that integrates core concepts from phenomenology with empirical investigations of experience by focusing on structures of human existence, such as embodiment, intentionality, intersubjectivity, affectivity, and temporality. Based on qualitative data from observations of 21 PE sessions, 22 student interviews, and the students’ diaries, we discuss three key findings: First, we look into the relational aspect of practising and discuss how three levels of intersubjectivity – primary, secondary, and narrative – affect students’ experiences. Second, we investigate the bodily aspect of practising by discussing how a dialectic orientation between deliberation, conscious reflections, and embodied actions led to a creative and awakened goal-directedness that nurtured future-oriented and meaningful repetitions. This supported the development of new movement capabilities and helped students discover new ways of experiencing meaning in movement landscapes. Lastly, we address the emotional aspects of practising, where we found that affective modes such as excitement, joy, and uncertainty worked as affordances that provided direction and meaning. Uncertainty turned out to be the essential mode to handle for both students and the teacher. Agency, just right challenges, in-depth reflections, creativity, problem-solving strategies, felt progress, and active repetitions over time emerged as crucial components for keeping uncertainty within the productive span. In short, the findings from this study qualify our knowledge of the experience of practising and throw new light on the process in which educative and meaningful experiences can grow from the practising of capabilities.

Introduction

Kretchmar (Citation2006a) presents and warns about The Easy Streets of physical education (PE), where ‘skills are not practiced diligently … new habits are not developed [and] learning plateaus are never encountered because they are never reached’ (p. 349). In such pedagogical scenarios, students are introduced to and entertained by activities. They are, however, not challenged, their habits are not developed, and the good stuff of movement remains hidden. Students are kept busy and happy but rarely turned on (Kretchmar, Citation2006a). Other scholars have raised similar concerns, stating that PE has become a one-size-fits-all, sport technique-based, multi-activity subject, where students are rarely challenged beyond an introductory level (cf. Kirk, Citation2013). Quennerstedt (Citation2019) summarises this development by stating that the E in PE (that is, the educational value) is under attack. Through a particular focus on practisingFootnote1 in PE, this study explores a possible exit from Easy Streets, which simultaneously appears as an intriguing route toward a distinct educational value. The following research question has guided this exploration: How do Norwegian 10th-grade students experience PE teaching informed by the practising model?

Outline of the practising model

Through the work of Aggerholm et al. (Citation2018), the practising model (PM) was coined as an independent pedagogical model, seeking to complement existing models within a models-based practice. Aggerholm et al. (Citation2018) prepare the ground for the PM by showing how Arendt’s (Citation1958) three forms of human activity, labour, work, and action, correspond with three dominating orientations in PE: health and exercise, sport and games, and experience and exploration. Relying on Sloterdijk’s (Citation2013) claim that Arendt’s work is incapable of grasping the human activity of practising, Aggerholm et al. (Citation2018) continue to explore the implications of pedagogy informed by practising. Through this, practising is positioned as an activity that does not rest on necessity (labour), is not an instrumental activity (work), and is not an autotelic disclosure of human plurality (action) (Aggerholm, Citation2015). On these grounds, Aggerholm et al. (Citation2018) describe a framework that conceptualises practising as a meaningful process, primarily informed by phenomenological philosophy and Sloterdijk’s (Citation2013) anthropological analysis of practising. Through four non-negotiable features, the PM framework challenges teachers to acknowledge students’ subjectivity and provide meaningful challenges, to help students focus on their aims, to help specify and negotiate standards of excellence, and to provide the students with sufficient time. The framework also presents seven hallmarks: agency, content, goal, verticality, uncertainty, effort, and repetition. In short, students must have agency in the sense that they actively seek to transform what they can do, and their practising must be grounded in content and directed towards a goal. The goal can be inspired and guided by others, but at the same time, it is self-referential as it involves a transformation of one’s capabilities. This implies an element of verticality as effort is directed towards improvement and refinement of capabilities, which in turn involves uncertainty as students strive towards doing something that is not yet possible. Rather than a monotone repeating of the same, which would have turned the repetitive process into mindless and blind drills, practising requires effort and active and forward-directed repetitions of difference. From this account, and because practising concerns a particular way of relating to what one does, it cannot be determined from a third-person perspective if a student is practising.

The current state of research

A broad body of literature within movement education pedagogy is relevant to this study. Concerning perspectives on the possible aims of movement learning and how learners experience developing new movement capabilities, Barker et al. (Citation2023) draw attention to habits, crises, and creativity, while Croston and Hills (Citation2017) and Nyberg et al. (Citation2020) challenge the understanding of abilities in PE. In addition, Barker et al. (Citation2020a) and Nyberg and Carlgren (Citation2015) describe what there is to know when knowing a movement, while others have focused on movement capabilities concerning feelings of joy (Barker et al., Citation2020b; Ingulfsvann et al., Citation2022), extended student autonomy (Nyberg et al., Citation2021), students’ sense-making (Rönnqvist et al., Citation2019), embodied self-knowledge (Standal & Bratten, Citation2021), and games (Smith et al., Citation2021).

Literature on nonlinear pedagogy, informed by ecological dynamics (Chow, Citation2013) or the constraints-led approach (Renshaw & Chow, Citation2019), contributes valuable perspectives on the development of movement capabilities and how the relationship between individual, environment, and task demands influences the process. However, in this literature, the subjective experience of and meaning-making through such methods is less emphasised (cf. Smith, Citation2022). Thus, the PM can supplement existing research with its dual focus on students’ subjective experience and the developmental aspect of movement learning. This can also feed into discussions of Meaningful PE (cf. Beni et al., Citation2017; Kretchmar, Citation2006b), where six features have been identified as important: social interaction, fun, challenges that are just right, increased motor competence, delight, and personally relevant learning experiences.

Lindgren and Barker (Citation2019) provided a seminal empirical contribution to the PM, discerning how students’ movement dispositions developed during lessons guided by the model. Further research investigated the teacher’s experiences and role enactment when teaching based on the PM (Askildsen & Løndal, Citation2023), while Vlieghe (Citation2013) and Brinkmann and Giese (Citation2023) theorised the broader phenomenon of practising, discussing its relevance from an educational and Bildung perspective.

In summary, existing literature provides a solid body of knowledge for understanding movement capability and meaningful experiences in PE. Nevertheless, from a practical pedagogical stance, the PM remains an underexplored orientation in PE. Even though students have practised something in many of the abovementioned studies, few studies have rigorously conceptualised, applied, and analysed teaching and learning informed by the PM. With this backdrop, by focusing on the students’ experiences of practising, we aim to address this gap within contemporary approaches to PE.

Theoretical framework

Phenomenology is an investigation of the structures of experience, subjectivity, and the lifeworld. In this study, we draw on Køster and Fernandez’s (Citation2023) Phenomenologically Grounded Qualitative Research framework (PGQR) that integrates core concepts from phenomenology with qualitative research by providing ‘an explicit focus on one or more structures of human existence’ (p. 150). Such structures include intentionality, embodiment, affectivity, intersubjectivity, temporality, selfhood, empathy, and spatiality. Variations within the general structures are referred to as modes. Affectivity, for instance, can be experienced in modes like excitement, joy, fun, or uncertainty. The general structures can either inform (front-loaded phenomenology) or be informed (retrospective phenomenology) by the study of experience. In our case, it went both ways. First, the study was frontloaded by the PM’s theoretical and philosophical grounding. Second, additional structures such as affectivity and intersubjectivity showed themselves as significant in the students’ experiences. In what follows, we present relevant structures for our study, structures that we will make use of to discuss student experiences. We acknowledge that these structures fundamentally are a ‘unified phenomenon’ (Køster & Fernandez, Citation2023, p. 152). Therefore, the discussion also aims at illuminating how they are intertwined in experiences of practising.

Intentionality

The phenomenological term intentionality refers to how consciousness is always consciousness of something. The object of consciousness can be oneself or concrete or imagined objects (Merleau-Ponty, Citation2012). This resonates with how practising is always practising of something – it is a way of forming oneself through an active engagement with content (Aggerholm, Citation2021). Still, there can be various ways of being directed at what you practise. On a more practical level, this can be analysed as a sense of agency in different degrees, from deliberate intention, over intention-in-action, to motor intention (Gallagher, Citation2020). Deliberate intention involves planning for the future, intention-in-action involves reflective or perceptual monitoring and adjustment of one’s actions, and motor intention is about the bodily and pre-reflective sense of appropriate movements. Following Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012), it is a central point that all three levels of intentionality rest on our bodily engagement with the world rather than an internal mental state.

Embodiment

Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012) sought to account for embodied subjectivity between intellectualist and mechanistic conceptions of movement and subjectivity. The lived body, he asserted, is ‘the vehicle of being in the world’ (p. 84). Therefore, he revised the Cartesian primacy of I think to argue that consciousness is primarily a matter of I can. This refers to the pre-reflective and bodily way we know how to move without consciously thinking about it. Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012) referred to this pre-reflective realm of being with the notion of habit body, which helps describe the experience of learning new ways of moving. The notion of habit describes learning new movements as a ‘grasping of a motor signification’ where we experience the harmony between what we aim at and what is given, between the intention and the performance (p. 144). Thus, an embodied account of movement capability can be understood as ‘knowledge in our hands, which is only given through a bodily effort’ (p. 145). Growing habits in this way can be described as renewing what Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012) called the body schema, and for a movement to be learned, it must be incorporated into this corporeal schema. Gallagher (Citation2005) developed this concept further by presenting a distinction between body schema and body image. He describes body schema as the coordinated functioning of the body when attention is directed at others or objects in the environment. Body image depicts body awareness when the body is the object of attention, i.e. when one is consciously attending to the body.

Affectivity

Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012) used the term affective intentionality to describe how emotions form part of the directedness of consciousness. To be emotionally directed or oriented by something is an element of experience that Fuchs and Koch (Citation2014) and Fuchs (Citation2016) have elaborated on. They describe how the intentionality of emotions provides a basic orientation about what matters to us and how they contribute to defining our goals and priorities. Fuchs (Citation2016) uses affective affordances to describe how ‘things appear to us as interesting, expressive, attractive, repulsive, uncanny, and so on’ (p. 196). The account of affective intentionality and affordances will inform our analysis of affective modes that we identify in the students’ experiences.

Intersubjectivity

Gallagher and Zahavi (Citation2008) describe how humans are tacitly pulled into intersubjective situations. To employ this perspective in our analysis, it is helpful to distinguish between three levels of intersubjectivity: primary, secondary, and narrative (Gallagher & Zahavi, Citation2008). Primary intersubjectivity describes the relations to others on a perceptual, affective, and bodily level, where experience is grounded in an embodied co-existence. In such relations, the perception of others’ movements can appear attractive and desirable. Aggerholm (Citation2021) describes this as an interaffective goal magnet that directs practising. Secondary intersubjectivity describes shared situations where an object or event is communicated. Here, the pragmatic context of the relation is central, and we find phenomena such as coordinated attention and joint actions. Narrative intersubjectivity involves a social and cultural layer of meaning that shapes the relations to others. It concerns dialogue and shared stories and provides a contextual understanding of the shared practice, which includes values, norms, and expectations.

Temporality

To analyse the temporality of practising, it can be helpful to distinguish between objective time and lived time. Objective time is the linear one we measure by a clock, and although practising undoubtedly takes time in this objective sense, lived time can help describe the experience of time. Here, time is not linear but a network of intentionalities that consists of retentions that carry the past into the present and protentions that anticipate the future (Merleau-Ponty, Citation2012). This can help analyse the repetitive process of practising, where students carry the sedimented experience from the previous movement into their next anticipatory move toward the goal.

Methods

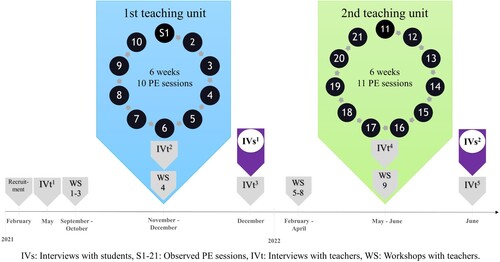

This study draws on data from a phenomenologically informed Interactive Action Research (IAR) project (Postholm, Citation2007) where the first author of this study followed a 10th-grade PE class at a Norwegian lower secondary school (15–16 years old students) through two teaching units of 6 weeks each (). A consistent focus throughout the project was the collaborative work between the first author and the teachers involved. Through nine workshops, we collaborated to translate the PM framework into practical teaching, plan the content of the teaching units, evaluate the teaching, and make revisions before the next session or unit.Footnote2 The first unit challenged students with exercises that related to circus as the overarching theme. The second unit centred around volleyball. provides a detailed description of the content of the teaching units.

Table 1. Overview of the two teaching units.

Both the pedagogical actions and data analysis are phenomenologically grounded. First, the phenomenological account of practising in the PM framework informed the pedagogical work in and around the two teaching units. Second, by drawing on Køster and Fernandez's (Citation2023) PGQR framework, we combine core concepts from phenomenology with the empirical investigation of experience. This approach aligns with recent developments in applied phenomenology (cf. Burch, Citation2021). As such, our data analysis is informed by and throws new empirical light on the structures presented in the theoretical framework.

Data collection

presents the overall design of this study and shows the different data collection methods applied. Since this study focuses on student experiences, only field notes from observations, student interviews, and student diaries are included as data sources.

The first author carried out all the data collection. Drawing on what Tjora (Citation2019) labels participant observation, 21 PE sessions of 60–90 min each were observed. A semi-structured and flexible observational guide was applied, providing some initial categories derived from the PM framework. This allowed the first author to be receptive to aspects such as agency, goal-directedness, effort, and uncertainty but also provided the flexibility needed to pursue incidents that were difficult to predict. Field notes from the observations were rewritten into complete text (101 data pages), and extracts from these notes are used in the findings section.

After each teaching unit, 11 students were selected for individual qualitative research interviews. Twenty-two interviews were conducted, comprising 15 students (nine girls and six boys), lasting approximately 20 min each (147 transcribed data pages). The selection of students to interview was based on observations and discussions with their teacher. Together, we chose students who provided a variety of experiences and represented both genders. As recommended by Køster and Fernandez (Citation2023), an interview guide that worked as ‘a broad hermeneutic roadmap’ (p. 159) was prepared. This steered the interviews through focus points derived from the PM framework.

The diaries the students wrote during this project were set up as digital files. Here, the students could also post images and videos of themselves practising. In advance, we formulated open-ended questions for the students to reflect upon during the project. These questions challenged them to write about their experiences, both the good and the bad, to reflect upon progress, to suggest changes in how they practised, and to compare their experiences from these units against previous PE teaching. Videos and images were meant to stimulate and support reflection and were captured at the beginning, halfway through, and at the end of each teaching unit. In about half of the PE sessions, the students were given time at the end of the session to complete their diaries. Otherwise, diary entries were assigned as homework to be completed before the next session. Twenty-one student diaries were included, comprising an average of 17 diary entries for each diary.

Data analysis

The first author used Braun and Clarke's (Citation2022) reflexive thematic analysis to analyse the collected data material. The entire data material had been continuously transcribed verbatim throughout the project. Grounded in the research question, student experiences were identified and coded, creating 426 initial codes. As recommended by Saldaña (Citation2013), we emphasised empirical sensitivity by preserving the participants’ formulations and choice of words in the created codes. The further analysis was a collaboration between both authors of this study. Based on Køster and Fernandez's (Citation2023) PGQR framework, we used the general structures of human existence to categorise the initial codes. An example is how codes related to the structure of affectivity were brought together to form a main theme that we labelled ‘The emotional aspect’. Here, we focus on students’ particular modes of affectivity, such as excitement, joy, fun, boredom, and uncertainty. This process created three phenomenologically informed themes, presenting central aspects of students’ experiences: (1) The relational aspect, (2) The bodily aspect, and (3) The emotional aspect.

Trustworthiness and ethical considerations

The students we report on in this study were recruited through their teacher, David. Information was first given to students and their guardians through an information letter. Then, the first author visited the class and participated in a parental/guardian meeting at school to inform about the project. Of 27 students, 21 consented to be interviewed and said their diaries could be used in the project. All participants are given aliases, and the study is approved by The Norwegian Centre for Research Data, which ensures that necessary measures have been taken to safeguard the participants’ privacy. Based on Merriam’s (Citation2009) suggestions, we have strived to provide descriptive validity through transparent and thorough descriptions of all aspects of the project. Drawing on Patton's (Citation2002) different triangulation methods, we have applied a data source and analyst triangulation to strengthen the study's overall validity. Data source triangulation was used to compare and cross-check the consistency of information. The analyst triangulation was conducted at two levels. First, the first author and the teacher constantly discussed and analysed sessions to improve practice. Secondly, the first and second authors discussed all aspects of data collection and analysis. Through these steps, we have tried to increase dependability by constantly checking possible researcher bias, challenging each other’s views, and focusing on discovering situations that did not conform to our expectations (Johnson, Citation1997). Concerning potential researcher bias, action research projects rely on close collaboration between researchers and practitioners. Thus, emotional connection through feelings of ownership and responsibility is one such bias that needed monitoring and careful consideration throughout the project.

Findings

This section presents the three themes from our analysis and uses the theoretical framework to discuss students’ experiences.

The relational aspect

I feel like it is just something built in. You want to feel that you belong to something, fit in, and mean something to someone else. (Jenny, IVs2)

Second, observation and imitation of proficient peers emerged as a more prominent feature in the circus unit than in the volleyball unit. An example is how a group of boys observed and imitated each other while practising acrobatic slam dunks. When one of them performed well, the following student in line tried the same trick but often added a new element as well. This process pushed the boys forward, constantly challenging each other and developing their abilities (Field notes, U1, S10). Jonathan was one of the boys in this group. When asked to elaborate on this incident in the interview, he concluded: ‘When I looked at others doing something well, it triggered me to perform the same skill. You convince yourself you can do it too’ (IVs1). Sandra drew attention to another aspect of observation: ‘I was on a higher level, so they watched me juggle, and if I did something well, everyone was like wooow, and then I felt like yeah inside’ (IVs1).

Finally, the analysis revealed relational aspects within both units that stood out as more inhibiting for practising. The following extract presents such an episode:

A group of students stood out today. Even though they were members of different volleyball teams, they abandoned them and instead established their own. They are pulled into an indistinctive and random play-like activity where the focus is showing off, bragging, and making fun of each other. (Field notes, U2, S4)

Gallagher (Citation2020) asserts that social connections are built into action from the very start, and Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012) describes how others’ phenomenal bodies appear as ‘the completion of the system’ (p. 368). As such, the relational aspect was expected to play an important role. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the social web surrounding practising in this study is significantly more visible and defining than in the model's framework. Therefore, to better discern how the relational aspect affected practising, we will discuss the students’ experiences against Gallagher and Zahavi’s (Citation2008) distinctions between primary, secondary, and narrative intersubjectivity.

The verbal and mutual collaboration where students helped each other, discussed solutions, and developed exercises through shared situations can be understood as a form of secondary intersubjectivity. This was a prominent and appreciated feature of both units, although more visible in the volleyball unit. At the end of this unit, many students emphasised the collaborative aspect as an essential source of motivation and progress. In short, it provided an important layer of meaning to the volleyball unit, a layer of meaning that was more incidental and up to the students to initiate in the circus unit.

Concerning primary intersubjectivity, practising within small groups enabled students to engage with each other on an emotional and often non-verbal level. This intersubjectivity was most prominent within the circus unit. Drawing on Fuchs (Citation2016), the gaze of others can be part of such a non-verbal connection to peers and can encompass subjects and situations. As described earlier, Sandra received such gaze in the circus unit. She felt this as a joyful bodily affection filled with pride and recognition. These feelings fuelled her desire to keep on practising. With the words of Fuchs and Koch (Citation2014), Sandra was moved to move; affective impressions triggered physical expressions. Jonathan exemplifies the counterpart in such a primary relationship. He observed and imitated peers practising basketball and felt that if they can, I can too. The displayed capabilities of the other students worked as a goal magnet (Aggerholm, Citation2021) that pulled Jonathan into a tacit relationship that provided a strong sense of agency and desire to develop his movement capability. In this matter, Jespersen’s (Citation1997) term sporting apprenticeship can contribute to our discussion. Jespersen (Citation1997) draws on Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy by asserting that imitation of movement patterns can be explained as a bodily process where another’s movements are immediately comprehended. Imitation can thus be seen as a transfer of body schemas that expands students’ being in the world. This was the case with the boys practising acrobatic slam dunks when they engaged in a creative imitation process, drawing on others’ skills to develop their own. To sum up, primary intersubjectivity played a prominent role during the circus unit, contributing to a tacit connection between peers and stimulating their willingness to continue practising.

Looking into narrative intersubjectivity, Gallagher (Citation2020) asserts that agency is not just in the head of the students; it is also affected by peer pressure and social referencing. As presented, a recurring challenge throughout the project, although most prominent in the volleyball unit, was that some students abandoned their personal practising and instead created exclusive practising groups. In our interpretation, these students complied with established social norms, values, and expectations, embraced the freedom provided less productively than others and had difficulties establishing a solid agency. Since such issues became more visible in the volleyball unit than in the circus unit, a reasonable assumption is that volleyball as content represents stronger norms, values, and expectations. This makes it more difficult for students to break free and pursue personal goals. Conversely, a circus represents more novel activities in the sense that students do not have the same normative reference basis as with traditional activities such as volleyball, football, and basketball. In short, a circus represents artistry, creativity, and barrier-breaking movements, which seem to hold more significant potential for verticality related to personal standards of excellence.

The self-referential aspect of practising might nuance the above reflections. Could the students’ behaviour be seen as a form of agency to challenge themselves within homogeneous groups with coinciding values and expectations? We believe this was true for some of the students, and it shows that it is difficult to assess from a third-person perspective if or if not a student is practising. Moreover, these findings point towards the teacher's role. Askildsen and Løndal (Citation2023) address this topic and highlight the importance of establishing a pedagogical tact built upon close and curious conversations with the students that can provide insight into the practising process, uncover learning obstacles, negotiate the socio-cultural forces in play, and support and challenge the students’ reflections concerning their practising.

The bodily aspect

Physical education is not a subject where we learn that much; it is more about getting to know the body. (Amanda, IVs1)

I MADE IT. I reached my goal today. To do so in session ten is so cool, and I am so proud. This truly is a new milestone for me – being able to juggle with three balls … what’s next … knives? (Diary, U1, S10)

Secondly, within both teaching units, the students displayed an awareness of their bodily experiences that were remarkably detailed and sensitive. They described how different body parts were positioned and used when they felt they were doing something better. They could also articulate the moments when they understood what was needed. Jenny, practising an ollie on the skateboard, provided such reflections:

In the beginning, I was mainly concerned with landing. Later, I understood that what happens in the air is essential. To soar more and gain more airtime, I need to have a snap on my right foot when I pop up the board. Then I get higher and have time to slide my left foot to push the tip down before landing. (Diary, U1, S4)

Finally, students suggested that they could feel something had changed even though it was not necessarily visible. In the second unit, these feelings were mainly connected to game-related situations and feelings of being able to move confidently on the field, predict the ball's direction and teammates’ movements, and position oneself accordingly. Amanda provided insight from the first unit:

One thing that’s difficult to see but that I feel is that I have become much more comfortable with parkour. Doing parkour has been something I have wanted to do, but I have been so nervous before … I am proud to have challenged myself as much as I have during this period. (Diary, U1, S10)

Concerning the in-depth reflections on the development of new movement capabilities, Gallagher’s (Citation2020) description of alignment between deliberate intention, intention-in-action, and motor intention provides a valuable theoretical perspective. Through defining a personal standard of excellence, for instance, being able to juggle effortlessly with three balls or doing an ollie on the skateboard, Ella and Jenny deliberated about what they wanted to achieve at a later point. This created an essential sense of agency in the early phase of practising. Such reflections spurred a more present intention-in-action where they monitored their actions against their goals and engaged in creative exploration of alternative solutions to challenges (see Barker et al. (Citation2023) for a coinciding view on creativity and challenges). This behaviour aligns with Gallagher’s (Citation2005) notion of body image, where one consciously attends to the body. In this process, we have shown how peers came with advice and worked as role models to observe and imitate. Moreover, using video, photos, and diary entries helped students reflect on their development, gradually enabling them to keep actions on track without always turning to conscious and perceptual monitoring. An example is how Ella developed a pre-reflective sense of appropriate movement patterns that made her feel more in control and gave a feeling of time slowing down as she got better at juggling. We suggest that moving back and forth between deliberation, conscious reflections, and embodied actions manifests the agentic goal-directedness of practising and nurtures what is described as active repetitions in the PM framework. Ella and Jenny were not just undertaking passive repetitions that merely sustained the inertia of habits. On the contrary, their habits were developed, and new learning plateaus were encountered through a creative problem-solving process.

The example of students referring to improvements that were difficult to observe nuances the saying practising makes perfect. In the case of Amanda, practising parkour did not make her perfect, at least not if perfect is understood as a narrow, static, and normative skill (Croston & Hills, Citation2017). However, practising certainly changed how she related to the surroundings, in this case, the parkour landscape. Our analyses also uncovered such experiences in the second unit, when students felt more comfortable on the volleyball court. The goal of practising can thus be linked to something that appears as an objective quantity, such as a seamless parkour run or a forearm pass in volleyball. However, the endpoint is best understood as an openness to new experiences. Mastering an ollie ultimately opens new possibilities, such as a kickflip, and improving your volleyball-related skills can make you more receptive to the complexities of a full-scale game. This is indeed ‘knowledge in our hands, which is only given through a bodily effort’ (Merleau-Ponty, Citation2012, p. 145). Through a more fine-meshed body schema, students related to their surroundings in new ways. Aggerholm and Larsen's (Citation2017) research on parkour supports these reflections. They described how parkour athletes try to break and clean a challenge, and by the time they have done so, the horizon has shifted, presenting new possibilities. Moreover, Nyberg et al. (Citation2020) showed that developing movement capabilities can be understood as knowing a movement landscape rather than knowing a movement in the right way. These studies correlate with student experiences in our study, suggesting that practising can broaden our understanding of valuable abilities in PE by providing new ways of experiencing meaning in movement landscapes and broadening students’ movement horizons.

The emotional aspect

I have had four great sessions, but today was so disappointing. I felt that I lost all my abilities. I didn’t manage anything – have no idea what happened. I got so angry. Now I’m going straight home to practise. (Ella’s Diary, U1, S4)

At first, it was fun, but after a few sessions, my mood went down. Lost all motivation. I was just ready to finish. It was kind of just the same all the time. No variation. No progress. Not very valuable if you ask me. (IVs2)

I was proud. I had practised my basketball trick shots for a long time, and many peers were looking at me this time. I showed off what I could do and got a good feeling. That gave me joy – like new energy. (IVs1)

Concerning the student group that remained within the inhibiting sphere of uncertainty, exemplified through Olivia’s experiences, a common feature was that they did not meet just right challenges and lacked the creativity and the problem-solving strategies needed to handle the test they were subjected to. They felt that their actions did not have the intended effect, inevitably diminishing their sense of agency (Gallagher, Citation2020). Even though Olivia kept up the hard work throughout the project, she experienced it as a meaningless process. The challenge was too complicated, and her personal goals were unrealistic to achieve within the timeframe of this project. These reflections connect to the temporal dimension of practising, suggesting that meaningful and productive practising does not arise from more of the same (retentions), as in Olivia's case, but from seeking changes in the future-oriented repetitions of difference (protentions) – just as Ella and Paul did. To facilitate such a process, it seems crucial to help students take on challenges appropriate to their starting point, stimulate reflection, creativity and problem-solving, help them identify progress, and, if necessary, adjust goals and practising strategies.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we asked how students experience teaching informed by the PM. In what follows, we will briefly summarise our findings. First, our discussion of the relational aspect of practising shows how the content of practising brings forth different dominating forms of intersubjectivity. While the circus unit profited from primary connections, such as observation and imitation, the volleyball unit was fuelled with meaning through secondary connections, such as verbally shared and negotiated situations. Narrative intersubjectivity, such as social norms, values, and expectations, had a more normative character in the volleyball unit, making the creation of a strong agency and the definition of personal standards of excellence challenging. Secondly, concerning the bodily aspect, practising brought students to the limits of their movement capabilities, providing an exit from the Easy Streets of PE. A dialectic orientation between deliberation, conscious reflections, and embodied actions led to a creative and awakened goal-directedness that nurtured future-oriented and meaningful repetitions, helping students develop new movement capabilities and discover new ways of experiencing meaning in movement landscapes. Moreover, content mattered, and the movement culture in which circus activities are embedded resonated more neatly with the PM framework. Lastly, affective modes such as excitement, joy, and uncertainty worked as affordances that provided direction and meaning to students’ practising. Uncertainty was the essential mode to handle for both students and the teacher, and agency, just right challenges, in-depth reflections, creativity, problem-solving strategies, felt progress, and active repetitions over time emerged as crucial components for keeping uncertainty within the productive span.

In short, the findings from this study qualify our knowledge of the experience of practising and throw new light on the process in which educative and meaningful experiences can grow from the practising of capabilities. We suggest that such a pedagogical scenario adds educational value to PE by bridging the developmental aspect of movement learning with students’ subjective experiences and meaning-making. Furthermore, we believe the PM can offer a valuable processual perspective on the six features of meaningful PE by shedding light on how meaningful experiences can grow from practising capabilities. Here, we see the potential for further explorations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Concerning the language, we follow Aggerholm et al. (Citation2018) and use the term practising. The nouns and verbs that describe this form of activity (practising) in Norwegian (øving/øve) easily lose meaning when translated into the British English verb practise (with s) or the American English verb practice (with c), the latter also being similar to the noun practice.

2 For a more detailed account of the action research design, the pedagogical actioning, and the collaborative work with teachers, see Askildsen and Løndal (Citation2023).

References

- Aggerholm, K. (2015). Talent development, existential philosophy and sport: On becoming an elite athlete. Routledge.

- Aggerholm, K. (2021). Practising movement. In H. Larsson (Ed.), Learning movements: New perspectives on movement education (pp. 118–133). Routledge.

- Aggerholm, K., & Larsen, S. (2017). Parkour as acrobatics: An existential phenomenological study of movement in parkour. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1196387

- Aggerholm, K., Standal, Ø, Barker, D., & Larsson, H. (2018). On practising in physical education: Outline for a pedagogical model. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1372408

- Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. The University of Chicago Press.

- Askildsen, C.-E. M., & Løndal, K. (2023). Practising in physical education: A study of a teacher’s experiences and role enactment. European Physical Education Review, Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336 ( 231183789

- Barker, D., Larsson, H., & Nyberg, G. (2023). How movement habits become relevant in novel learning situations. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education. Advance online publication, 1–9.https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2022-0272

- Barker, D., Nyberg, G., & Larsson, H. (2020a). Exploring movement learning in physical education using a threshold approach. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(3), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2019-0130

- Barker, D., Nyberg, G., & Larsson, H. (2020b). Joy, fear and resignation: investigating emotions in physical education using a symbolic interactionist approach. Sport, Education and Society, 25(8), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1672148

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Chróinín, D. N. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest (grand Rapids, Mich ), 69(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

- Brinkmann, M., & Giese, M. (2023). Practising the practice. Towards a theory of practising in physical education from a Bildung-theoretical perspective. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, Advance online publication, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2023.2167968

- Burch, M. (2021). Make applied phenomenology what it needs to be: an interdisciplinary research program. Continental Philosophy Review, 54(2), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11007-021-09532-1

- Chow, J. Y. (2013). Nonlinear learning underpinning pedagogy: Evidence, challenges, and implications. Quest, 65(4), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2013.807746

- Croston, A., & Hills, L. A. (2017). The challenges of widening ‘legitimate’ understandings of ability within physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(5), 618–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1077442

- Fuchs, T. (2016). Intercorporeality and interaffectivity. Phenomenology and Mind, 11, 194–209. https://doi.org/10.13128/Phe_Mi-20119

- Fuchs, T., & Koch, S. C. (2014). Embodied affectivity: on moving and being moved. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00508

- Gallagher, S. (2005). How the body shapes the mind. Oxford University Press.

- Gallagher, S. (2020). Action and interaction. Oxford University Press.

- Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2008). The phenomenological mind: An introduction to philosophy of mind and cognitive science. Routledge.

- Ingulfsvann, L. S., Moe, V. F., & Engelsrud, G. (2022). Unpacking the joy of movement – ‘it’s almost never the same’. Sport, Education and Society, 27(7), 816–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1927695

- Jespersen, E. (1997). Modeling in sporting apprenticeship: The role of the body itself is attracting attention. Nordisk Pedagogik, 17(3), 178–185.

- Johnson, R. B. (1997). Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. Education, 118(2), 282–292.

- Kirk, D. (2013). Educational value and models-based practice in physical education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(9), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.785352

- Køster, A., & Fernandez, A. V. (2023). Investigating modes of being in the world: An introduction to phenomenologically grounded qualitative research. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 22(1), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-020-09723-w

- Kretchmar, R. S. (1975). From test to contest: An analysis of two kinds of counterpoint in sport. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 2(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.1975.10654094

- Kretchmar, R. S. (2006a). Life on easy street: The persistent need for embodied hopes and down-to-earth games. Quest, 58(3), 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2006.10491888

- Kretchmar, R. S. (2006b). Ten more reasons for quality physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 77(9), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2006.10597932

- Lindgren, R., & Barker, D. (2019). Implementing the Movement-Oriented Practising Model (MPM) in physical education: Empirical findings focusing on student learning. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(5), 534–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1635106

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2012). Phenomenology of perception. Routledge.

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research. A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Nyberg, G., Barker, D., & Larsson, H. (2020). Exploring the educational landscape of juggling – challenging notions of ability in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1712349

- Nyberg, G., Barker, D., & Larsson, H. (2021). Learning in the educational landscapes of juggling, unicycling, and dancing. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1886265

- Nyberg, G., & Carlgren, I. (2015). Exploring capability to move – somatic grasping of house-hopping. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(6), 612–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.882893

- Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed). SAGE Publication.

- Postholm, M. B. (2007). Interaktiv Aksjonsforskning: Forskere og Praktikere i Gjensidig Bytteforhold. In M. B. Postholm (Ed.), Forsk Med! Lærere og Forskere i Læringsarbeid (pp. 12–33). Damm.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Physical education and the art of teaching: transformative learning and teaching in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport, Education and Society, 24(6), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1574731

- Renshaw, I., & Chow, J. Y. (2019). A constraint-led approach to sport and physical education pedagogy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1552676

- Rönnqvist, M., Larsson, H., Nyberg, G., & Barker, D. (2019). Understanding learners’ sense making of movement learning in physical education. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 10(2), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2019.1601499

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed). SAGE Publications.

- Sloterdijk, P. (2013). You must change your life. Polity Press.

- Smith, W. (2022). Enactive cognition and physical education – a natural coupling. Sport, Education and Society, 27(9), 1061–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1960497

- Smith, W., Ovens, A., & Philpot, R. (2021). Games-based movement education: developing a sense of self, belonging, and community through games. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(3), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1886267

- Standal, Ø, & Bratten, J. (2021). Feeling better’: Embodied self-knowledge as an aspect of movement capability. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(3), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1886268

- Tjora, A. (2019). Qualitative research as stepwise-deductive induction. Routledge.

- Vlieghe, J. (2013). Experiencing (im)potentiality: Bollnow and Agamben on the educational meaning of school practices. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 32(2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-012-9319-2