ABSTRACT

Nation-states have concerns about the health and wellbeing of their citizens and these concerns have directly or indirectly influenced educational reform and curriculum development. In 2000, China issued a directive of ‘Health First’ which applied to all elements of the education system. In its scale and scope, this represented a significant and far-reaching reform, ushering in a period where school leaders and teachers were expected to engage with new policy documents and develop curriculum practices to reflect the ambitions of ‘Health First’. This article provides an opportunity to explore the complex and dynamic processes of teachers’ curriculum enactment within the broader socio-political context. Our analysis offers a unique insight into the legal system in China and how this played an important role in teachers’ decision-making and professional practice. Guided initially by grounded theory, 22 physical education teachers in the north of mainland China were interviewed to explore their experiences of the reform to the curriculum. To develop a better understanding of how ‘Health First’ was taken up and enacted by teachers and specifically recognising the characteristics of a non-western research context, we deployed two theoretical concepts – ‘technologies of the self’ and ‘self-cultivation’. Our findings reveal, rather than prioritising ‘Health First’, curriculum enactment was predicated on ‘safety first’ as a result of the complex interplay between teachers’ awareness of the legal system and their professional ethics, which led to these teachers interpreting the maxim of ‘Health First’ as ‘safety first’.

Introduction

Researchers have highlighted the proliferation of initiatives and policies focusing on health as part of nations’ attempts to reform school curriculum (Kilgour et al., Citation2015; Kirk, Citation2019; Meng et al., Citation2021). Teachers play a central role in curriculum enactment as they explore and embrace the uncertainty of transformative teaching practices to bring about curriculum change (Quennerstedt, Citation2019). China has embarked on a process of wholescale curriculum reform, influenced by globalisation, however, it retains strong features of its roots and traditions in Confucianism (Huang et al., Citation2015). The Chinese government oversees and directs the education of 22% of the world’s students (158 million in elementary and secondary education), an education system on this scale means that any changes have wide and far-reaching effects (MoE, Citation2022). In China, concerns about the declining trend in students’ health compelled the government to issue the ‘Health First’ directive for the education system (CPC and State Council, Citation1999). To align with this policy imperative, the Physical Education (PE) curriculum [体育 tiyu] became the Physical Education and Health curriculum (PE&H) [体育与健康 tiyu yu jiankang], combining health literacy lessons and outdoor practical health-related exercise. The PE&H curriculum explicitly stated that ‘through the teaching of PE&H courses, students can master sport techniques, develop physical fitness, gradually develop a sense of health and safety and a good lifestyle, and promote the coordinated and comprehensive development of their bodies and minds’ (MoE, Citation2011, p. 3).

Curriculum enactment is a dynamic process, and few policies arrive in school fully formed (Ball Maguire & Braun, Citation2012). Thus, the process of curriculum enactment involves teachers navigating policy frameworks and engaging in an ongoing process of decision-making, and in this case, determining what ‘Health First’ would mean and how to develop and adapt their educational practices to meet the stated aims of PE&H. The findings reported in this paper are connected to a larger study and Meng et al. (Citation2021) provided a detailed analysis of the ‘Health first’ policy and PE&H curriculum in China and how changes in curriculum were taken up and responded to by teachers. This paper goes further and affords the opportunity to consider the complexities of PE teachers’ professional judgments concerning safe practice and risk management as they engaged in curriculum enactment related to the PE&H curriculum.

The research was informed by Charmaz’s (Citation2014) grounded theory, as we were aware that given the context of the research, rather than adopting a view that particular elements would enable or restrict curriculum enactment, it would be important to establish the findings from data generated via the qualitative semi-structured interviews with teachers. After engaging with data generated which gathered insights into teachers’ curriculum enactment, we became increasingly aware of the importance of context in our analysis of data. China, with its socialist political environment, a hierarchical legal system, and a curriculum underpinned by Confucius ideology, is considerably different from Western countries where many previous studies considering curriculum enactment have taken place (Alfrey et al., Citation2021; Horrell, Citation2016; Linnér et al., Citation2022). Zinn’s (Citation2019) analysis highlighted that risk practices are embedded within a political and cultural environment, and not mere aggregates of individual choice. Through our grounded approach to the analysis of data, we employed concepts from Foucault’s work, carefully considering the diversity, wideness, and possibilities of social practice in curriculum enactment (Hunt & Wickham, Citation1994). Foucault (Citation2000a, p. 341) stated ‘the exercise of power is a management of possibilities’; therefore, rather than pursue a causal line of inquiry, inferring that teachers’ curriculum enactment is restricted or controlled because of context, we endeavoured to understand the situated nature of practice.

In line with this approach, we have carefully considered the nature of China’s curriculum reform, embedded within a complicated web of meanings comprised of national policies, school governance, and interactions between teachers, students and their parents/carers. Considering the context of our research, Confucianism is also used to explore the interaction between the perceptions of others and individual behaviour within the framework of Chinese culture. Therefore, the heuristic devices – ‘technologies of the self’ and ‘self-cultivation’ – were employed as a conceptual frame to inform how socio-political factors had been experienced by each PE teacher in this study and in turn, influenced the development of their thinking and practical enactment of the curriculum over time. The paper extends the research on curriculum enactment in PE by revealing how teachers’ awareness of the legal system and their professional ethics led to them interpreting the maxim of ‘Health First’ as ‘safety first’. In the following sections, we start by providing an overview of governmentality and China’s legal system, as it was these elements in the teachers’ responses that initially led us to Foucault’s work and specifically ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault, Citation2000a). We then demonstrate how the addition of self-cultivation formed a heuristic device and underpinned our analysis of teachers’ curriculum enactment.

Governmentality and China’s legal system

Educational policies are not neutral in their design (Kelly, Citation2009). They are constructed, often from power struggles about what matters, with the final product comprising diverse discourses about educational values, beliefs about teaching and learning, and interpretations of society (Rossi et al., Citation2009). In the context of this study, safety and risk management have a significant place in teaching and school management. The operations of the legal system and its effect on school systems is not a common topic in policy analysis literature (Burch, Citation2007). However, as subsequent sections of this paper will show, the legal system in China and associated discourses related to safe practice and risk management construct ways of thinking and acting which produce and establish messages about what are ‘normal’ actions for PE teachers in school.

Porsanger and Magnussen’s (Citation2021) findings indicated that due to the nature of activities as part of the PE curriculum teachers adopt a multifaceted approach to managing risk. This approach involves being mindful of the dynamics between students and learning activities, with the teacher being able to respond in different ways to potential risk levels in class contexts. For example, teachers often manage the risks associated with competitive sport activities by imposing particular conditions on student conduct, adapting game play, or teaching prescribed techniques. As Wong (Citation2013, p. 108) mentioned ‘if a person cared for something, she would constitute herself in such a way that there is a bond with that which she cared about’. These processes construct a form of ‘governmentality’. Foucault’s work brought to the fore the importance of considering the ‘conduct of conducts’ (Foucault, Citation2000a, p. 341), and in this case what influences, patterns and shapes discourses and actions.

Foucault’s (Citation2000a, p. 40) analysis of power included the emergence of the legal system in European society, ‘law during this period was a particular way of knowing, a condition of possibility of knowledge whose destiny was to be crucial in the western world’. In many societies, to safeguard working and living conditions, there is legislation and the means to enforce laws via a legal system. It is commonplace for health and safety legislation to apply in all workplaces. Therefore, in many nations schools work within a framework which seeks to provide safe environments for teachers and students, and where there are clear processes for determining accountability and liability. To provide a specific example, in the UK, the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 is the primary piece of legislation covering occupational health and safety. The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 support the Act and together they provide a legal framework for workplaces. According to the explanation from Health and Safety Executive (Citationn.d.), the day-to-day running of the school is usually delegated to the school’s management team, while the local education authority, as the employer, is accountable for the health and safety of school staff and students. Several other countries – Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA – have comparable health and safety at work regulations, which include the safeguarding of students and teachers in schools.

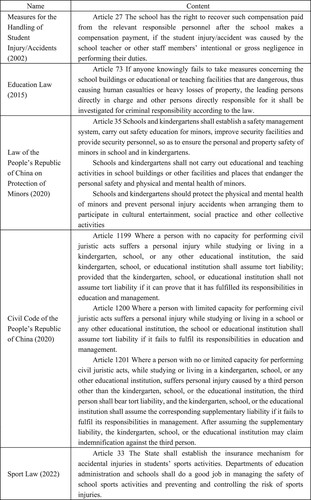

In China, the Education Law and the Law on the Protection of Minors set out the legal obligations of schools in relation to the safety and protection of students. In addition, as set out in , there are other laws which contain explicit statements pertaining to the safety of students in school settings.

Figure 1. Guidance and legislation concerning safety and risk management in schools.

Note. The laws in the were officially translated into English by the Chinese government, with the exception of the Sports Law and the Measures for the Handling of Student Injury/Accidents. For the purposes of this paper a translation has been created by the first author and checked by a licenced lawyer. The Sports Law was revised in 2022 and will come into effect from January 2023. The link to the official translations for other laws are below: Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Minors, http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/c23934/202109/39cab704f98246afbed02aed50df517a.shtml, Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/c23934/202107/7c7f9fc3765947a89627ef67e89e8b84/files/da0d8a6da39a478ab93639efd815b685.pdf, Education Law, http://en.moe.gov.cn/Resources/Laws_and_Policies/201506/t20150626_191385.html.

At present, even though many laws include statements about safety and risk management in schools, issues of legal responsibility and accountability are less clearly defined. The guidance contained in ‘Measures for the Handling of Student Injury/Accidents article 27’ set out that PE teachers can be required to meet the costs of payments to claimants. For schools and teachers, this guidance and the more recent legislative frameworks have created uncertainties about who is liable in the case of accidents, resulting in ambiguities over the sums of compensation payable and who would be responsible for paying these (Ma, Citation2021). As our analysis of data provided by teachers in this study will show, PE teachers are aware of the legal frameworks and were concerned about the extent to which they can be held accountable for incidents that occur in classes (Lan & Li, Citation2019). Drawing on Foucault’s (Citation1994, p. 341) consideration of how power relations impact conduct, our findings reveal how PE teachers’ ‘exercise of power’ reflected their ‘conduct of conducts’ and their ‘management of possibilities’. Therefore, China’s legal system is an important socio-political contextual factor influencing teachers’ decision-making about teaching practices.

Methodology

Charmaz’s (Citation2014) work on grounded theory (GT) was employed as the methodological framework for this qualitative interview-based study. The simultaneous data generating and analysis of this methodological stance helped us to follow early leads in data. It highlighted how various socio-political matters impacted schools and the way in which teachers drew upon their own internal concerns to regulate their thoughts and actions. Data analysed in this paper were generated from a larger study of teachers’ thoughts, attitudes, beliefs and experiences of curriculum enactment. The findings reported in this paper reflect that during the coding process issues of safe practice and risk management featured strongly in teachers’ responses. We sought to understand and uncover why teachers’ concerns about safety and risk management informed their decision-making about curriculum enactment. Specifically, we interrogated teachers’ interpretation of ‘Health first’ as ‘safety first’. An overview of the three phases of our research process is provided below.

Phase 1: interviews, transcription and coding using grounded theory

Situated in northern China, 22 PE teachers (8 female, 14 male) participated in a study focused on their perceptions and experiences of curriculum enactment. All the PE teachers had more than ten years of teaching experience and worked in different schools – state-funded, public-private partnership, and private – thereby ensuring teachers could provide insights into the process of curriculum enactment and the context of these reforms. The first author conducted 45–90 min semi-structured face-to-face interviews with PE teachers. The questions included, What do you think about the ‘Health First’ curriculum reform? How do you understand the new PE&H curriculum? How do you implement the new curriculum? Has the curriculum reform had any impact on your teaching? How do you understand the health element in the new PE&H curriculum? All participants gave informed written consent to take part, and to respect their requests for anonymity, they were given pseudonyms. NVivo 12 Pro was used for the analysis of interview data; the process of coding followed initial, focused and selective steps. The initial coding step was conducted in Chinese by the first author: microanalysis of the transcribed data to decompose the text into independent events and repeated data comparison and the elimination of repetitive or inconsistent codes. Via these steps, from the 377 initial codes, 55 selective codes were grouped to reflect emergent concepts in the data. At this point, these grounded data were taken to the other members of research team and led to phase two.

Phase 2: translating, checking and clarifying meaning of codes

Given that the interviews, transcription, and coding processes were conducted in Chinese by the first author, it was imperative to translate these data into English for subsequent coding and analysis. In order to avoid potential misrepresentation, in the second phase, extensive discussions related to translating, checking and clarifying the meaning of initial and selective codes were undertaken by all the authors. GT requires a complex process of data analysis and coding, which is made more challenging when interviews are not in English, because creating meaningful labels for sections of data is based on ‘gerunds’ (Nurjannah et al., Citation2014). The main concern of non-English writers is the precise expression of their thoughts in the second language (St. John, Citation1987). The aim of this phase was not only to identify the words and terms present in each interview transcript, but also to ensure that the original meanings were not misunderstood or misrepresented due to differences in language backgrounds. Thus, the second and third authors of this article contributed to detailed checking of the context and semantics of data used in the study, which consequently laid the foundation for the third stage of analysis.

Phase 3: analysing using theoretical tools

In the third phase, we recoded data by revisiting the themes generated in phase one and two and engaged in close reading of the raw data contained in transcripts. Consistent with a central tenet of GT, our coding was not initially informed by preconceived theories, and we endeavoured to maintain theoretical sensitivity to a wide range of codes (Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). During the coding process, to enhance the methodological rigour of the study, we ensured the meaning and context of discourse were carefully considered and grounded in data provided by the teachers. Through repeated readings of the coding and data provided by the teachers, ideas about the relationship between core categories and related concepts began to emerge. The ‘safety first’ category emerged as more and more PE teachers made a strong connection between curriculum enactment and safety in their teaching practice. In phase one, initial coding identified 17 distinctive aspects of safe practice and risk management, which then led to two selective codes – ‘safety first’, ‘health and safety’. Therefore, we sought to understand and explore why the teachers’ concerns about safe practice and students’ health were consistent features of their reports of curriculum enactment. The flash of realisation, the ‘Eureka moment’ as Glaser (Citation1978) described it, occurred during this phase, and the value of Foucault’s work on the ‘technologies of the self’ began to emerge as a possible lens through which to consider our analysis of data. As we continued to read all 55 selective codes generated, we recognised that the theoretical insights afforded by Foucault had their limitations. This was because there were selective codes reflecting Chinese cultural characteristics such as ‘teachers’ sense of morality’, ‘the teacher’s sense of responsibility’ and ‘the conscience of PE teachers’. These formed a picture of the decision-making processes of PE teachers in their enactment of the curriculum. This storyline provoked reflections about our analysis and led to discussions about the Confucian concept of self-cultivation, which then led to our further exploration of initial codes and the underlying interview data. Hahm (Citation2001) makes a compelling connection between Confucian ‘self-cultivation’ and Foucauldian ‘technologies of the self’. This is based on the impossibility of removing all elements and traces of power in social and political relationships, and rather than viewing these as inherently bad, reveals the merits of considering the extent to which individuals have scope for initiative, care and freedoms in their practice (Zhao, Citation2019a; Zhao, Citation2019b). Therefore, ‘technologies of the self’ and ‘self-cultivation’ – were employed as the heuristic devices to afford insights into the interpersonal dynamics of curriculum enactment as experienced by the teachers in this study.

Technologies of the self

The Foucauldian concept of ‘relations of power’ refers to special ways of managing people through the guidance of subjects’ conduct, which lies between the tension of technologies of governance of others and technologies of self-governance (Sanchez Garcia & Rivero Herraiz, Citation2013). Power also operates through ‘technologies of the self’ and technologies of self -governance, incorporating the various means by which individuals constitute themselves as subjects. Foucault’s concept of technologies of the self describes processes where individuals actively form ‘the self’ in different ways, thus transforming themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness and perfection (Foucault, Citation2000a; Foucault et al., Citation1988). In this study, ‘technology of the self’ brings into view the political, social and educational sets of practices engaged in by the teachers. In this sense, curriculum enactment is conceived of as a special kind of technologies of the self, requiring forms of self-examination, self-regulation, self-reflection, self-surveillance and self-governance (Foucault, Citation2000b). Foucault (Citation2000b) draws attention to the ‘ethical conduct’ or ‘care’ of the self, a connection not always evident in studies using his work. Retaining a focus on ‘care’ of the self and drawing on the other sub tools of ‘technologies of the self’ is important because understanding the interactions between these elements can reveal how individuals may refuse particular subjectivities (McEvilly, Citation2012). Therefore, our analysis of curriculum enactment is informed by the connections in Foucault’s work between ‘ethics’ and ‘technologies’ or ‘practices of the self’.

Technologies of the self is increasingly used to provide a theoretical frame for research into curriculum and policy issues in general (Greig & Holloway, Citation2016) and specifically in PE (Hardley et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, Foucault stressed that these technologies are always embedded and offered in and by a culture comprised of human beings. The active construction of the self is always mediated by the society where he/she belongs and is not purely self-creating (Sanchez Garcia & Rivero Herraiz, Citation2013). Alert to these considerations, Confucian ‘self-cultivation’ will be offered alongside ‘technologies of the self’, as part of our efforts to move beyond a determining view of discourse and to understand the ‘possibilities’ and ‘conditions’ of PE teachers in this study, which afforded opportunities for reflection and decision-making.

Self-cultivation

While ‘technologies of the self’ has gained traction, the application of Eastern philosophical concepts, such as self-cultivation as a theoretical tool, in the analysis and dissemination of findings in English is in its infancy. Self-cultivation has strong political significance in both ancient and modern Chinese society. ‘Self-cultivation’ is the most commonly accepted English equivalent for the Chinese term Xiu Shen (修身). The Confucian classic text ‘Great Learning’ established that self-cultivation is the foundation of the moral self and stated: ‘the way to great learning is to promote and carry forward good virtues and ethics, observe the sentiments of the people and obey public opinions, until reaching the goal of perfection and beauty’Footnote1 (Confucius & Legge, Citation2013, p. 356). As a result of economic reform, there are profound changes in China’s social structure thereby influencing people’s outlook on life and worldview. For example, Wang (Citation2011) identified the challenges of extreme individualism, hedonism, and the pursuit of wealth brought by the market economy thereby strengthening the necessity and urgency of self-cultivation. Since the 18th Party Congress, the Chinese Central Government has attached great importance to the cultivation of the Core Socialist Values and in 2014, General Secretary Xi Jinping stated, ‘morality is of fundamental importance to the individual and to society, and the first thing to do is self-cultivation’ (Xi, Citation2014, np).

Generally, self-cultivation refers to personal and social development which encompasses the ongoing self-improvement of one’s physical, psychological, spiritual and moral life (Du & Guo, Citation2008). In a narrow interpretation, self-cultivation has a strong moral sense, reflecting peoples’ value expectations for moral cultivation and the diligent pursuit of personal development (Ames, Citation2006). However, it should be noted that the ‘self’ in Confucian self-cultivation is not an isolated or even isolatable individual, but at the centre of all relationships (Tu, Citation1998). The Confucian framework of personal cultivation involves an extension from the self to the other, from the internal to the external, and from the near to the far (Wang, Citation2013). In the process of associating with others, self-cultivation can help the individual to understand the meaning of existence and the way of life, including self-understanding (between body and mind), mutual understanding (between people and others) and ultimate understanding (between people and society). Thus, self-cultivation occupies a pivotal position in the link between the self and the community mediated by a variety of political, social and cultural institutions (Tu, Citation1998). At the personal level, it involves a complex process of empirical studies and mental disciplines. At the social level, self-cultivation can adjust the relationship between people and others, in order to achieve physical and mental harmony (Zhao, Citation2018).

In the field of education, the MoE (Citation2019, np) published a series of documents setting out ‘the requirements for teachers in classroom teaching, student care, teacher-student relationship, academic research and social activities’. These documents highlight the importance of teachers’ acting in particular ways and provide an important dimension when researching curriculum enactment. A teacher’s individual perceptions of the curriculum are mediated through a broader set of concerns as they seek to find a balance consistent with the ongoing process of self-cultivation. Considering the context of the research, we have combined the Chinese Confucian concept of ‘self-cultivation’ with Foucault’s concept of ‘technologies of the self’. The creation of this heuristic device for exploring curriculum enactment in China enabled us to consider the teachers’ perspectives, their individual decision-making, and wider cultural imperatives.

Findings and discussion

Socio-political factors patterning teachers’ curriculum enactment efforts

Our analysis indicted that the PE teachers’ attempts to lead classes in the spirit of ‘Health First’, were enabled and constrained by a number of socio-political factors. Chief among these factors, and the focus of this section, was the interplay between the safety culture in schools and the legal system. Most PE teachers in this study displayed an acute awareness of how considerations for children’s safety directly influenced their teaching practice. While the rhetoric used by Ji Feng and Yuting below may be exaggerated, these extracts capture the serious nature of most teachers’ concerns:

Whether in the news media, in government documents, or in meetings with school leaders, [in PE] students’ safety is always one of the most frequently mentioned words. (Yuting)

If students lose one hair in PE class, parents can ‘kill’ teachers, so PE teachers are very conservative. (Ji Feng)

The operation of the legal system has led to teachers’ heightened awareness of safety, which affects teachers’ decision-making and their practice. The statements from Xiaomin and Jinmei below contain explicit and direct reference to aspects of the legal system, and reflected similar concerns which were also expressed by other teachers:

[The] PE teacher is a vulnerable group. The law protects children. If a student has an accident in your class, it would be lucky to meet a reasonable parent … If you encounter an importunate parent, they will sue the school in court. [Therefore,] the school is not willing to take responsibility, and the fault is passed on to the PE teacher. (Xiaomin)

Of course, there is the chance that you can win the lawsuit, but you will be exhausted. The process of investigation is complicated and time-consuming, and I do not want to get myself in trouble like this. (Jinmei)

A superficial analysis could suggest teachers’ avoidance of risk reflected their attempts to protect themselves from complaints. However, our analysis, informed by Foucault (Citation2000a, Citation2000b), makes the case that legal action and the prospect of paying compensation means that care for the self was also about care for others. This form of ‘technologies of the self – self cultivation’ displayed by the teachers, while heavily constraining the possibilities of achieving the ‘Health First’ goals of the PE&H curriculum, was a necessary step to serve their more pressing concerns about safety. The following sections will demonstrate teachers were not exclusively seeking to protect themselves, they were also prioritising the care of students through the management of safety and risk in their classes.

Safety and risk management in practice

The previous section revealed that for a teacher in China, an accident in a lesson may not just represent an unfortunate event for a student but also creates ethical, moral and financial pressures for PE teachers. Jianhua’s account of a student who, after a gymnastics lesson, returned unsupervised to practice on the horizontal bars serves as a stark reminder that even though a student did not follow the school’s regulations, it was the teacher who was cautioned.

[The curriculum leader for physical education] called me to the office and blamed me: ‘why [do] you need to teach this technique? You need to focus on the students’ PE test’. From then on, I will not teach this kind of ‘dangerous’ technique in class, and the school leaders decided to remove the horizontal bar to avoid the risk. (Jianhua)

The exclusion of curriculum content and the avoidance of specific activities and practices might be a strategy taken to minimise risks, but teachers are also aware that removing all risks is problematic. As the PE&H curriculum requires students to develop ‘a sense of health and safety’ (MoE, Citation2011, p. 3) they have the opportunity to use risk in an educative way. This obligation of education is related to self-cultivation, which is not only founded on more than the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes, but also incorporates a sense of emotional connection to students. As an example of this approach, Haoxiang stated:

Learning and technical training are dangerous to some extent. Therefore, I generally do not teach lessons in strict accordance with the requirements of the curriculum. I pay more attention to [students’] experience, their happiness, and their will to overcome difficulties. (Haoxiang)

Zinn (Citation2019) and Porsanger and Magnussen (Citation2021) made similar observations, noting that teachers did not passively accept risks. Both studies reported that teachers actively considered safety management strategies for activities considered risky and made informed decisions about how to teach safely. However, when compared to these previous studies, we would argue our findings suggest that in China, safety and risk management appear to have a more pronounced impact on curriculum enactment. Through PE teachers’ actions and interactions, they engaged in technologies of self and self-cultivation, as they combined different strategies to deal with risk, in ways that reflected their cultural values, knowledge of their institution and an evaluation of their personal responsibilities.

Health first by teaching safely

PE teachers talked about the necessity to create educative environments where they explicitly taught students how to be safe and manage risks. While safety and risk management were central pillars of their decision-making, the participants in this study still demonstrated a desire to balance ‘Health First’ and ‘teaching safely’. Malin said:

Health education is the most important part of the PE&H curriculum … a very important part of teaching safely is to let students learn how to protect themselves. So, I constantly emphasize safety precautions before and after class. (Malin)

To be honest, I do not really understand the concept of health in [the] PE&H curriculum. If policy makers insist on linking the two words together [tiyu yu jiankang 体育与健康], then I think it means ‘tizhi’ (体质). (Meiying)

The extract below from Jianhua indicates how her and other teachers’ experiences during their teacher education shaped their view that health was strongly connected to training and protecting the body.

I do not remember studying any health-related courses when I was in the university. What we learned was mainly based on sport physiology, such as sports training, sports rehabilitation and sport medicine. In terms of education, a lot of content is related to demonstration and protection. (Jianhua)

Although teachers’ teaching practice of ‘Health First’ is influenced by multiple factors, in this study, the participants still demonstrated a desire to balance ‘Health First’ and ‘teaching safely’. As Weihong indicated,

I think health education in PE is to teach students how to prevent sports injuries. Exercise can make people healthy, but incorrect exercise can also cause injuries. So, keep safety, in other words, safe exercise is the basis for improving health. (Weihong)

Seeking harmony between curriculum ambitions and teaching safely

As discussed above, there are complicated and interconnected socio-political considerations involved in the process of teachers’ curriculum enactment. The directive of ‘Health First’ has led to reform of the PE&H curriculum and the expectation of specific actions from teachers; however, teachers are also aware that school leaders seek to keep all students safe and parents have a high expectation of children’s performance in the PEPE. Surong stated:

If students are not willing to do specific movementsFootnote4, then I will not force them to do it. I try to use some other ways to keep them both safe and active. I did this not only because I was afraid of [school] leaders or accidents, but also because the children were too tired, and I want them to be well. … You know, students pay too much attention to their academic performance. I did not want PE classes [to] put them under pressure. I hope my class is not limited to learning sports techniques and practice exam items. (Surong)

In the process of curriculum enactment, PE teachers were acutely aware of a broad range of concerns. They did not blindly abide by the requirements of the PE&H curriculum and orientate their practice solely towards health first; nor was their practice dominated by the management of risk and safety. Instead, by carefully evaluating the possibilities of their context, these PE teachers endeavoured to achieve a curriculum which reflected their values and cared for students (Chen et al., Citation2017). This Confucian wisdom of seeking self-cultivation helps PE teachers to create an ‘ethical space’ and support students to develop a wider view of health, even in the face of a strict education system and less flexible policies. Therefore, as the discussions in this section have highlighted, curriculum enactment and practice are not only driven by powerful external forces, but are also shaped by teachers through ‘technologies of the self’ and ‘self-cultivation’.

Conclusion

Motivated by the realities and demands of globalisation, China’s government and policy makers have sought to engage in curriculum reform. The key driver of this reform across all elements of the education system is ‘Health First’. With this study taking place in the subject of PE, we investigated how ‘Health First’ was taken up and enacted by PE teachers. Acknowledging this study was located in a non-western country, the heuristic device – ‘technologies of the self’ and ‘self-cultivation’ – was employed with sensitivity following careful and rigorous interrogation of data gathered from teachers. Data analysis indicated that teachers’ curriculum enactment efforts are carried out within a complicated socio-political context, with interplay between ‘technologies of the self’ and ‘self-cultivation’, as teachers sought to be transformative, find personal harmony and navigate the competing demands of stakeholders. Our findings suggested that the reform was not revolutionary; rather than prioritise the ‘Health First’ maxim, teachers prime concern was ‘safety first’. While it could be possible to provide an interpretation that blamed teachers for their lack content knowledge of health education, this would not reflect the constraints of the socio-political context. The research data allowed us to demonstrate that teacher decision-making was not only related to curriculum reform policies and associated regimes of accountability, but also interconnected to the legal system.

While previous studies have considered teachers’ interaction with policy and elements of governmentality, our study has revealed that, in China, teachers’ awareness of their vulnerability within the legal system strongly influenced their curriculum enactment. Therefore, this study provides the first account of how teachers in China adapt to retain a balance between concerns with self, curriculum enactment, interactions with stakeholders, and how they engage with students. There may be other nations where teachers are also acutely conscious of safety and risk management and the findings of this study bring forward new insights in the analysis of teachers’ decision-making. Curriculum enactment is complex and does not follow a linear or predictable translation from policy into practice. If China is to fulfil its ambitions to place ‘Health First’, then teachers of PE require support during their initial teacher education and through professional development, so that teaching health within PE does not have to be a choice between safe practice and health-enhancing experiences in PE.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our thanks to the anonymous reviewers and to the editorial team for their valuable suggestions to improve the clarity and quality of the article. We also wish to thank the participants who agreed to take part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The original ancient Chinese of this phrase in the Great Learning as follows:大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。

2 The introduction of the PEPE as part of the entrance requirements for high schools in China was instrumental in promoting ‘Health First’.

3 The curriculum stipulates specific content and activities should be taught, for example; health education, basketball, football and gymnastics. However, it is important to note that while the curriculum specifies content and activities; this does not preclude different interpretations of how to enact the curriculum and we acknowledge these interpretations have an impact on a teacher’s evaluation as to whether the curriculum as enacted reflects the curriculum as text. Our analysis of the interview data revealed that teachers’ interpretations of the required curriculum were patterned by considerations of safety, rather than the maxim of health first.

4 Surong is referring to the preparation that teachers engage in for the PEPE during PE lessons, see Meng et al. (Citation2021) for further details of the activities students are required to do for the examination.

5 The original ancient Chinese of this phrase in the Analects as follows:子曰:其身正,不令而行,其身不正,虽令不从。

References

- Alfrey, L., Lambert, K., Aldous, D., & Marttinen, R. (2021). The problematization of the (im)possible subject: An analysis of health and physical education policy from Australia, USA and Wales. Sport, Education and Society, 1–16.

- Ames, R. (2006). The common ground of self-cultivation in classical Taoism and Confucianism. Chinese Cultural Studies, 4(3), 1–22.

- Ball Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. Routledge.

- Burch, P. (2007). Educational policy and practice from the perspective of institutional theory: Crafting a wider lens. Educational Researcher, 36(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X07299792

- Chapman, G. (1997). Making weight: Lightweight rowing, technologies of power, and technologies of the self. Sociology of Sport Journal, 14(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.14.3.205

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Chen, X., Wei, G., & Jiang, S. (2017). The ethical dimension of teacher practical knowledge: A narrative inquiry into Chinese teachers’ thinking and actions in dilemmatic spaces. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(4), 518–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1263895

- Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council of the Chinese Central Government (CPC and State Council). (1999). The decisions on deepening educational reform and promoting quality-orientated education. http://www.scio.gov.cn/zhzc/6/2/Document/1003546/1003546.htm.

- Confucius, & Legge, J. (2013). Confucian analects, The great learning & The doctrine of the mean. Dover Publications.

- Curtner-Smith, M. D., & Meek, G. A. (2000). Teachersí value orientations and their compatibility with the national curriculum for physical education. European Physical Education Review, 6(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X000061004

- Douglas, M. 1992. Risk and blame: Essays in cultural theory. Routledge.

- Du, Z. J., & Guo, L. B. (2008). Confucianism thought of self-cultivation and its methods. Chinese Ethical Thought, 3(1), 53–58.

- Foucault, M. (1994). The subject and power. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), Power (pp. 326–348). New Press.

- Foucault, M. (2000a). Technologies of the self. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), Michel foucault: Ethics, subjectivity and truth: Essential works of Foucault 1954-1984 (pp. 223–251). Penguin Books.

- Foucault, M. (2000b). The ethics of the concern for self as a practice of freedom. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), Michel foucault: Ethics, subjectivity and truth: Essential works of foucault 1954-1984 (pp. 281–302). Penguin Books.

- Foucault, M., Martin, L. H., Gutman, H., & Hutton, P. H. (1988). Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison / Michel Foucault; translated from the French by Alan Sheridan. Penguin. (Original work published in 1975).

- Fullan, M. (2007). The New meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology Press.

- Greig, J. C., & Holloway, S. M. (2016). A Foucauldian analysis of literary text selection practices and educational policies in Ontario, Canada. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 37(3), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1043239

- Hahm, C. B. (2001). Confucian rituals and the technology of the self: A Foucaultian interpretation. Philosophy East and West, 51(3), 315. https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2001.0042

- Hardley, S., Gray, S., & McQuillan, R. (2020). A critical discourse analysis of Curriculum for Excellence implementation in four Scottish secondary school case studies. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42(4), 513–527.

- Health and Safety Executive. (n.d.). The role of school leaders - who does what. https://www.hse.gov.uk/services/education/sensible-leadership/school-leaders.htm.

- Holton, J., & Walsh, I. (2017). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative and quantitative data. SAGE Publications.

- Horrell, A. B. (2016). Pragmatic innovation in curriculum development: a study of physical education teachers’ interpretation and enactment of a new curriculum framework [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Edinburgh.

- Huang, Z., Wang, T., & Li, X. (2015). The political dynamics of educational changes in China. Policy Futures in Education, 14(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315612644

- Hunt, A., & Wickham, G. (1994). Foucault and Law: Towards a sociology of law as governance. Pluto Press.

- Kelly, A. V. (2009). The curriculum: Theory and practice, (6th edition). Sage.

- Kilgour, L., Matthews, N., Christian, P., & Shire, J. (2015). Health literacy in schools: Prioritising health and well-being issues through the curriculum. Sport, Education and Society, 20(4), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.769948

- Kirk, D. (2019). Precarity, critical pedagogy and physical education. Routledge.

- Lan, Q., & Li, X. (2019). Liability determination of school sports injury accidents: An analysis framework based on evolutionary game. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183403

- Linnér, S., Larsson, L., Gerdin, G., Philpot, R., Schenker, K., Westlie, K., Mordal Moen, K., & Smith, W. (2022). The enactment of social justice in HPE practice: How context(s) comes to matter. Sport, Education and Society, 27(3), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1853092

- Ma, H. J. (2021). Establishment and improvement of China’s sports legal system—based on the revision of the sports law of the People’s Republic of China. China Sport Science, 41(1), 7–20.

- McEvilly, N. (2012). The place and meaning of ‘physical education’ to practitioners and children at three preschool contexts in Scotland [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Edinburgh.

- Meng, X., Horrell, A., McMillan, P., & Chai, G. (2021). ‘Health First’ and curriculum reform in China: The experiences of physical education teachers in one city. European Physical Education Review, 27(3), 595–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20977886

- Ministry of Education. (2011). Compulsory education physical education and health curriculum. Beijing Normal University Publishing Group.

- Ministry of Education. (2019). Letter of reply to proposal No. 2730 (Political and Legal No. 241) of the second Session of the 13th National Committee of the CPPCC. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/xxgk_jyta/jyta_zfs/201912/t20191206_411124.html.

- Ministry of Education. (2022). National education development statistics bulletin 2021. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202209/t20220914_660850.html

- Nurjannah, I., Mills, E. J., Park, T., & Usher, K. (2014). Conducting a grounded theory study in a language other than English. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014528920

- Page, D. (2017). The surveillance of teachers and the simulation of teaching. Journal of Education Policy, 32(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1209566

- Porsanger, L., & Magnussen, L. I. (2021). Risk and safety management in physical education: A study of teachers’ practice perspectives. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 76. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.663676

- Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Physical education and the art of teaching: Transformative learning and teaching in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport Education and Society, 24(6), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1574731

- Rossi, T., Tinning, R., McCuaig, L., Sirna, K., & Hunter, L. (2009). With the best of intentions: A critical discourse analysis of physical education curriculum materials. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 28(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.28.1.75

- Sanchez Garcia, R., & Rivero Herraiz, A. (2013). ‘Governmentality’ in the origins of European female PE and sport: The Spanish case study (1883–1936). Sport, Education and Society, 18(4), 494–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.601735

- St. John, M. (1987). Writing processes of Spanish scientists publishing in English. English for Specific Purposes, 6(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(87)90016-0

- Tu, W. M. (1998). Self-cultivation in Chinese philosophy. In Routledge encyclopaedia of philosophy (pp. 613–626). Taylor and Francis.

- Vaz, P., & Bruno, F. (2003). Types of self-surveillance: From abnormality to individuals ‘at risk’. Surveillance & Society, 1(3), 272–291. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v1i3.3341

- Wang, D. S. (2011). The modern transformation of chinese educational tradition: A case study of self-cultivation education in late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. East China Normal University.

- Wang, H. Y. (2013). Confucian self-cultivation and Daoist personhood: Implications for peace education. Frontiers of Education in China, 8(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03396962

- Wong, J. (2013). Self and others: The work of ‘care’ in foucault’s care of the self. Philosophy Faculty Publications, 57(1), 99–113.

- Xi, JP. (2014, May 5). Young people should consciously practice core socialist values - Speech at the symposium for teachers and students at Peking University. The People’s Daily, 002.

- Zhao, F. W. (2018). Research on Xi Jinping’s self-cultivation value [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. China University of Mining and Technology.

- Zhao, W. (2019a). Re-invigorating the being of language in educational studies: Unpacking Confucius’ ‘wind-pedagogy’ in Yijing as an exemplar. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(4), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2017.1354286

- Zhao, W. (2019b). ‘Observation’ as China's civic education pedagogy and governance: An historical perspective and a dialogue with Michel Foucault. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(6), 789–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2017.1404444

- Zinn, J. O. (2019). The meaning of risk-taking – key concepts and dimensions. Journal of Risk Research, 22(1), 1–15. doi:10.1080/13669877.2017.1351465