ABSTRACT

The discipline of performance analysis is founded upon the collection and analysis of objective and reliable data to support the coaching process. While research has begun to identify the potential importance of trust in applied sporting environments, there remains a paucity of inquiry that seeks to explicitly investigate trustworthiness in the work of performance analysts. To redress this situation Jisc online survey data was collected from performance analysts (n = 88, age: 37 ± 11 years, experience: 8 ± 6 years) practising across sporting contexts and geographic areas. Findings showed that: (1) appearing trustworthy to a range of working others was an important goal for performance analysts, (2) trustworthiness was considered essential for building positive working relationships, respect and perceptions of role-related competence (3) being perceived as trustworthy can generate desirable as well as help to avoid undesirable working conditions, including career progression and employment security, (4) analysts often seek to influence others perceptions of their trustworthiness by demonstrating important characteristics such as technical and tactical knowledge, being friendly and approachable, being punctual and hardworking, and evidenced-based, (5) an important facet of this was, often in conjunction with the coaching staff, concealing known information, particularly to athletes regarding poor performance to avoid psychological damage or where the data did not fit the coach’s approach, and (6) most performance analysts suggested the professional preparation and development of performance analysts needs to place greater emphasis on facilitating social sensibilities that practitioners can use to enhance perceptions about their workplace trustworthiness. The findings of this study generate new knowledge regarding the social features of performance analysis work, thus contributing to a growing critical social analysis of sport work in performance environments, as well as raising important practical implications for those responsible for educating the performance analysis workforce.

Introduction

Since the early work of Hughes and Franks (Citation1997) that delineated sports performance analysis as a discipline, performance analysis has become a well-established and integral part of the coaching process (Groom & Cushion, Citation2004; Groom et al., Citation2011, Citation2012; James, Citation2006; Middlemas et al., Citation2018; Middlemas & Harwood, Citation2018; O’Donoghue, Citation2006). Whilst the positive impact and perceived value of performance analysis by athletes and coaches has been demonstrated (Nicholls et al., Citation2018; Nicholls et al., Citation2019; O’Donoghue, Citation2006), the importance of social interactions between athletes and coaches within the coaching process, which underpin the efficacy of pedagogical delivery (Groom et al., Citation2011; Kojman et al., Citation2022; Nelson et al., Citation2014), power relations (Groom et al., Citation2012; Taylor et al., Citation2017; Williams & Manley, Citation2016), and (micro)political actions (Huggan et al., Citation2015) have received less attention.

Recent work has highlighted the importance of better understanding the development of social relationships in the performance analysis workplace through an appreciation of professional self-understanding, interests, and identity (Gibson & Butterworth, Citation2023). A deeper understanding and appreciation of these social skills may further develop the quality and efficacy of formal qualifications and accreditations, supporting analysts’ experiential learning. Thus, social interactions between coaches, athletes, and analysts may enhance the perceived value of performance analysis within the coaching process. Indeed, Martin et al. (Citation2021, p. 857) not only identified ‘building relationships’ as one of the five areas underpinning applied performance analysis work but argued that it is ‘the most fundamental’ aspect of expertise. For them, the effective delivery of performance analysis is predicated on the analyst’s ability to ‘initiate, foster and consolidate professional relationships’ with working others (Martin et al., Citation2021, p. 858). This observation is perhaps understandable, as research is beginning to report some compelling accounts of the interpersonal facets of performance analysts’ work in high-performance sport settings with the importance of building positive working relationships highlighted alongside the consequences of failing to do so effectively.

To achieve productive working relationships with coaches, analysts strategically built their support around the needs of their coaches and avoided workplace conflict, while presenting themselves as hardworking, honest, and approachable practitioners (Bateman & Jones, Citation2019). Relatedly, Huggan et al.’s (Citation2015) micro-political analysis of an experienced soccer analyst’s career experiences revealed how obtaining favourable recognition from not only the head coach, but a diverse range of contextual others, was a valued working condition. The worth significant others attached to the analyst’s position and work directly impacted on how he perceived his standing in the club as well as associated job security, causing him to implement a range of micro-political survival strategies. These included selling the importance of performance analysis technologies to working others, presenting himself as a competent and valuable member of the coaching team, taking on extra duties, seeking to develop positive working relationships with coaching staff and players which included completing work aimed at helping others to appear competent in their role. Research has also started to acknowledge the importance of performance analysts establishing interpersonal trust in the workplace. Indeed, Bateman and Jones (Citation2019, p. 5) reported that performance analysts felt that ‘being trusted and respected was paramount in maintaining open relationships’. Similarly, McKenna et al. (Citation2018) spoke of the importance of establishing trust and rapport in the performance analysis workplace by using a range of tactics to demonstrate competence and commitment. These included completing analysis work quickly, demonstrating sport specific knowledge, observing training sessions, travelling to away matches, and engaging informal conversations. While these studies touch on notions of trust, Francis et al. (Citation2015) remains, to date, the only work to have explicitly focused on interpersonal trust in performance analysis. Analysis of the lead author’s auto-ethnographic reflections on performance analysis work over a 15-month period in a Paralympic sport identified four factors (i.e. appearance and visibility, confidence, honesty and integrity, and self-care) essential for establishing trust between the analyst, athlete, and other staff (Francis et al., Citation2015).

Trust is clearly important to building and maintaining effective working relations and essential to ‘advance the provision of performance analysis within a high-performance sport system’ (Francis et al., Citation2015, p. s48). However, despite its importance, our understanding of trust and distrust in the work of performance analysts (as well as other types of sport work) remains embryonic at best. This situation is somewhat problematic as social scientists have increasingly considered issues of trust and trustworthiness as they relate to social relationships and organisational dynamics (Kramer & Cook, Citation2004; Luhman, Citation2017; Robbins, Citation2016; Sztompka, Citation1999). Trust has been positioned as a relational expression of the confidence someone places in the intentions of another to encapsulate their interests, whereas trustworthiness is identified as the likelihood that someone will act as desired (Hardin, Citation2002, Citation2006). Within such scholarship trust is considered a core ingredient of social and organisational life (Ward, Citation2019), the glue ‘upon which all social relationships ultimately depend’ (Ronglan, Citation2011, p. 155). In contrast to this wider social analysis, the topic of interpersonal trust and trustworthiness has received limited explicit examination in the sociology of sport. One notable exception is the work of Gale et al. (Citation2019) which identified those interactional strategies that participant community sport workers employed to judge the trustworthiness of their colleagues as well as impacts of perceived trustworthiness on how they managed workplace relations and interactions with these individuals. While this study usefully advanced understanding about how sport workers evaluate and respond to the trustworthiness of working others, research must now consider the importance sport workers place on appearing trustworthy as well as those strategies they use to present themselves as trustworthy individuals, including how associated social sensibilities are developed. Indeed, foundational research has started to identify the importance sport workers place on securing the trust and respect of working others through a process of impression management (e.g. Jones et al., Citation2004; Potrac et al., Citation2002). Relatedly, scholarship in the organisational science literature contends the impression management work of organisational actors is often driven by a desire to appear trustworthy (DuBrin, Citation2011; Elsbach, Citation2004). It is in relation to images of workplace trustworthiness that the present study empirically and analytically focuses.

In subscribing to the view that the exploration of trust and trustworthiness matter to our understanding of organisational life, this paper considers the management of trustworthiness perceptions by performance analysts working across sporting and geographic settings. Utilising an online survey comprising quantitative and qualitative questions, novel insights are presented into: (a) the importance that performance analysts place on appearing trustworthy to working others, (b) those strategies they use to try to secure the trust of significant working others, (c) motivations, benefits, and costs of appearing (un)trustworthy to those with whom they work, and (d) reflections about the adequacy of their education and training for preparing analysts for this aspect of their work as well as associated recommendations for the preparation and professional development of the performance analysis workforce. Our findings not only contribute significant and original knowledge to the social investigation of performance analysis work but produce insights and associated analyses with applied value to the field. Given the importance that has been placed on performance analysts building positive workplace relations, the observation that this aspect of professional practice ‘does not seem to be a prominent feature of applied PA training’ would appear somewhat problematic (Martin et al., Citation2021, p. 861). We hope this will further our empirical understanding of this important area and will lead to actions directed towards addressing this deficiency in applied practice.

Methods

Sample

Eighty-eight (n = 88) performance analysts (age: 37 ± 11 years, experience: 8 ± 6 years) participated in the study (see ). The largest proportion of participants identified as holding full-time (62.5%) or part-time (14.8%) employment, with analysts also working on fixed-term contracts (6.8%), in a self-employed capacity (6.8%), being employed on a zero-hours contract (3.4%), working voluntarily (3.4%) and completing work as part of an educational placement (2.3%). Most of the participants were male (83%), and three-quarters (72.7%) based in Europe, followed by Oceania (12.5%). The remaining participants were based in Asia (6.8%), North America (4.6%), Africa (2.3%), and South America (1.1%). Most participants highlighted they worked within soccer (44.3%), rugby union/league (20.5%) or across multiple sports (12.5%). Small numbers worked in tennis (3.4%), Gaelic games, handball, hockey, and netball (2.3% each), athletics, badminton, basketball, equestrian, gymnastics, and ice-hockey (1.1% each) and another category where the sport was not specified (3.5%). This study received ethical approval from Edge Hill University’s Science Research Ethics Committee [ETH2223-0160].

Table 1. Participant demographics across the employment types (values in parentheses are percentages out of the total participant pool).

Procedures

A Jisc online survey (i.e. a tool for creating online surveys) comprising Likert scale and open-ended questions was utilised to develop rich insights into practitioners’ understandings of trustworthiness in their applied performance analysis work. The following approaches were implemented to distribute the survey and gain respondents: (1) A weblink to the survey was emailed out to all International Society of Performance Analysis of Sport (ISPAS) members, (2) the survey link was shared (via email, SMS message, and WhatsApp®) with performance analysts known to the authors, inviting them to complete and share the survey with colleagues; and (3) the online survey was promoted across social media (i.e. Twitter® and LinkedIn®) via the authorship teams’ personal accounts.

Following the presentation of a participant information sheet and informed consent page, the online survey comprised three sections. The first explored the importance respondents attached to appearing trustworthy to working others. This section required participants to respond to 1 Likert scale statement and 4 open-ended questions. The open-ended questions asked the participants to identify their targets of trustworthiness, generative forces for their presentations of trustworthiness as well as those perceived benefits and costs associated with appearing (un)trustworthy. The second section focused on how analysts seek to appear trustworthy to working others. In this section participants completed 2 Likert scale statements and 2 open-ended questions to identify the extent to which specific characteristics are demonstrated to convey trustworthiness as well as which characteristics form part of these presentations. Respondents were also asked to comment on whether analysts conceal work related information, the sharing of which could cause others to question their trustworthiness as well as what information they hide, from whom, and why. The third section explored the participants’ thoughts about how well performance analysis courses adequately develop the ability of analysts to effectively present themselves in trustworthy ways, with reference to specific courses, before commenting on if and how the education of performance analysts could better prepare practitioners to achieve these ends. In this section participants were required to complete 2 Likert scale statements and 2 open-ended questions. The survey ended by asking the respondents if there was anything they would like to share about trustworthiness in performance analysis work that had not been covered by the previous questions.

Data analysis

Likert scale questions from the survey were analysed using Microsoft Excel® to generate descriptive statistics (i.e. frequency and percentages) and bar-charts that visually represent key findings. The responses to open-ended questions (i.e. qualitative data) were subject to iterative data analysis (Tracy, Citation2018, Citation2020). This involved subjecting data to emic and etic coding. Emic analysis entailed the identification of common themes through a process of open coding to develop a rich understanding of the participants’ perceptions and experiences of workplace trustworthiness. Etic analysis was concerned with consulting theories, concepts, and relevant literature to identify means of explaining our research findings. Here, we found scholarship addressing organisational impression management (DuBrin, Citation2011; Elsbach, Citation2004; Goffman, Citation1959), theorisation of the psychology of self (McAdams, Citation2013), as well as the key characteristics of trustworthiness in organisational settings (Mayer et al., Citation1995) to offer analytical utility.

Results

Importance of appearing a trustworthy analyst

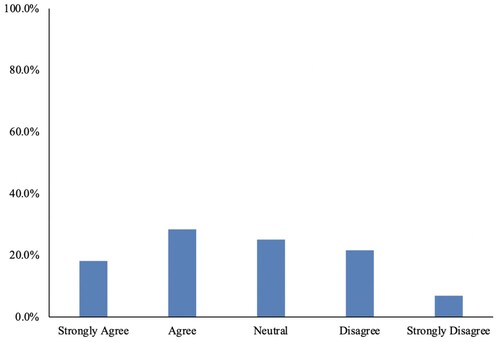

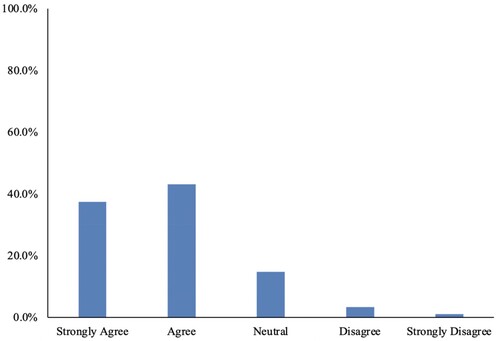

Seventy-seven (87.5%) participants strongly agreed in the importance of appearing trustworthy when working with others in their applied practice (with no disagreements to the statement, ). While coaches and players were most frequently identified as the targets of their efforts, respondents often cited other analysts, sporting directors, managers, and support staff as important trust-dependant co-workers. Appearing trustworthy was considered essential for building positive working relationships as well as convincing others to respect the quality of work analysts completed. The analysts identified a variety of generative forces that influenced their desire to appear trustworthy at work. Some respondents spoke of ‘personal pressures to prove yourself’ (P10) to ‘meet my own standards’ (P15) and ‘do a good job and be trustworthy’ (P51). Others endeavoured to present themselves as trustworthy analysts ‘to keep my job’ (P67), identifying that ‘organisations want to keep trustworthy performers’ (P57). Those seeking a permanent role spoke about needing to ‘leave a good impression to try and acquire a full-time position in the future’ (P65). Another suggested ‘without trust you won’t be offered another contract, fit into the team culture or be recommended for other job opportunities’ (P87). Career aspirations and future employment opportunities clearly mattered and influenced their desire to appear trustworthy at work, recognising that sport is a ‘small world so news travels fast’ (P45). When ‘coaches trust you they are more likely to recommend your work if you’re doing a good job’ (P24). In a similar vein, ‘people talk and reputations spread. If you come across as untrustworthy to just one person, they will tell others about it and that can affect relationships internally and externally’ (P71).

Figure 1. Question – It is important for me to appear a trustworthy performance analyst to the people I work with.

Respondents identified that securing the trust of working others generated several beneficial outcomes. Being seen as someone worthy of trust contributed to their being more ‘involved in the decision making process’ (P66), prompted others to be ‘more open to ideas and receptive to feedback’ (P29), gave them greater ‘freedom of thought and action’ within their work (P77), encouraged ‘further professional learning’ opportunities as ‘people share their experiences more if they trust you’ (P45), and established ‘new job opportunities or higher position in my actual job’ (P72). Essentially, the analysts were conveying that gaining the trust of working others could result in ‘improved collaboration, increased influence and credibility, enhanced professional reputation, stronger client relationships, and overall job satisfaction’ as ‘trust-based relationships foster a positive work environment and open doors to new opportunities and partnerships’ (P79). In contrast, analysts spoke of the actual and/or potential consequences of failing to secure the trust of working others due to appearing untrustworthy. Here, participants spoke of being given ‘less responsibility’ (P28), experiencing ‘strained relationships’ (P79), being ‘shunted from normal day to day responsibilities’ and ‘being outside the decision making process’ (P43), ‘becoming ostracised’ (P3), ‘having coaches and players question your work or second guessing you’ (P24), being ‘ignored’ (P41) by working others, as well as ‘your work not being used’ (P12), leading to a ‘lack of impact’ (P17), and potentially ‘losing your job or get relegated to a minor position’ (P33). Being distrusted was also identified as resulting in a ‘loss of credibility as a practitioner’ (P76) and ‘having a bad name in the sector’ (P42). It is because of these outcomes, especially in relation to retaining and furthering their employment in an insecure work environment, that the participants held garnering workplace trust, and presenting themselves as trustworthy, in such high regard.

Managing images of trustworthiness

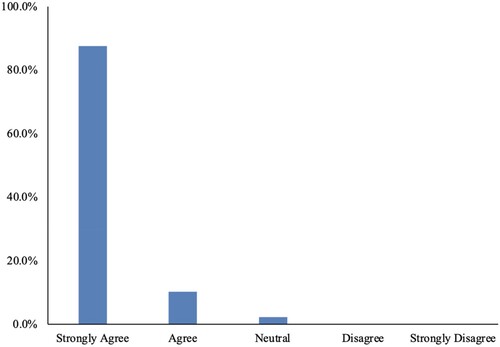

Half of the respondents (50%; ) strongly agreed that there were certain characteristics they attempted to convey to others to appear trustworthy (less than 5% disagreed). Characteristics conveyed to appear trustworthy to working others included having ‘good tactical and technical knowledge’ of the sport (P10), the importance of being ‘friendly, approachable and caring’ (P49), ensuring ‘players and coaching staff ask me questions and interact with me to build trust’ (P21), respecting ‘the confidentiality of conversations with players and management’ (P32). Being punctual and hardworking was also considered important: ‘I try to ensure I am punctual so they know they can trust me to be on time. Furthermore, any work given to me, I make sure is done in good time so they can rely on me to complete tasks before a deadline’ (P65). Respondents placed considerable emphasis on demonstrating the accuracy and reliability of their analysis as well as their ability to produce high quality work in response to those requests made of them. Analysts stressed a need to ‘present work that is completely accurate and evidence-based’ as ‘one mistake or error is enough to put doubt into people's minds’ (P20). Respondents also spoke about needing to appear open and honest ‘so that both players and coaches are aware of what I can (and cannot do) so they have realistic expectations of the analysis that might be conducted’ (P9) as well as being transparent about ‘what the data is and isn’t saying and acknowledging limitations as coaches will smell bullshit’ (P17). For many respondents the demonstration of these characteristics was considered particularly important for establishing their trustworthiness in the eyes of others: ‘As a performance analyst each of these characteristics is individually important because they collectively contribute to establishing trust. Competence, reliability, integrity, objectivity, clear communication, active listening, accountability, and professionalism build credibility, assure stakeholders of my reliability, and create a positive perception of my capabilities and trustworthiness as a performance analyst’ (P79). A small group of analysts expressed ‘I do not try to demonstrate anything’ (P33) as for them work ‘has to be completely natural’ as ‘attempting to portray "trustworthy characteristics" cheapens relationships’ (P41). For one such analyst their focus was, instead, on doing ‘what I believe is right and true’ and ‘if that makes me more trustworthy, great’ (P57). Therefore, the respondents identified a number of strategies that they employed to develop others’ perceptions of their trustworthiness including knowledge-based role requirements (knowledge of the sport), interpersonal skills (e.g. friendliness, approachability, honesty, openness and caring) and personal characteristics (e.g. punctuality, reliability, integrity, and being hardworking and diligence).

Figure 2. Question – I try to demonstrate specific characteristics to others to present myself as a trustworthy performance analyst.

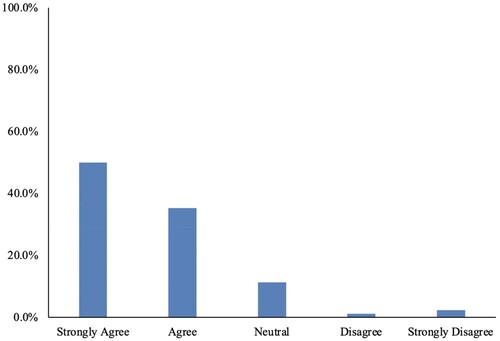

The need to hide work related information from their colleagues was a contentious statement with 46.6% agreeing but 28.4% disagreeing (). While numerous analysts stressed the importance of honesty and owning their errors, it was acknowledged that ‘analysts will hide mistakes as some coaching staff can get angry and not find mistakes acceptable’ (P7). As such, some analysts ‘will need to hide this to prevent loss of trust’ (P55). Similarly, errors were also found to be hidden from athletes: ‘If data hasn’t been recorded properly players will question it and become disengaged if it doesn’t look accurate, so I have seen people change things to make it seem more “normal” to keep player buy-in’ (P22). Indeed, respondents shared several examples whereby they concealed workplace information from athletes to remain trustworthy in the eyes of coaching staff. For example, one respondent explained how ‘data would be hidden from players that already knew they’d not performed to their expectations’ to ‘protect the psychology of the player’ (P40). Another analyst spoke of ‘hiding data from players which may seem counterintuitive to the coaching process that the staff are trying to put forth’ (P43). In the following example the respondent detailed being complicit in the sharing of misinformation during pre-competition and post-competition analysis sessions: ‘Manager may choose to present an opponent in a certain way to justify team selection. In debriefs you can also paint a picture that represents the story the manager wants to be told, rather than a fair representation of the game’ (P63). As one participant explained, ‘data can be manipulated to paint or present information which isn’t true’ (P48). An analyst shared with us that ‘sometimes players would ask for data that would present them in a better light to the coaches, to try to get back into the team. Coaches would sometimes be aware of this and ask myself to not share certain data with certain players’ (P9). Another respondent explained that ‘analysts may not choose to disclose information on team selection or transfer/contract information from athletes’ stating that ‘this is not necessarily the role of the analyst to deliver this information’ (P12). As such, to appear trustworthy at work some analysts found themselves having to conceal information from working others. Here, respondents identified the need to maintain trust through strategies such as hiding mistakes, concealing data that either does not appear accurate or does not support the coaches’ approach (e.g. putting others’ interests first). Other times data may be hidden to preserve an athlete’s confidence after poor performance, to paint a specific partial picture of an athlete’s performance or present a partial picture of an upcoming opponent.

Learning to become a trustworthy analyst

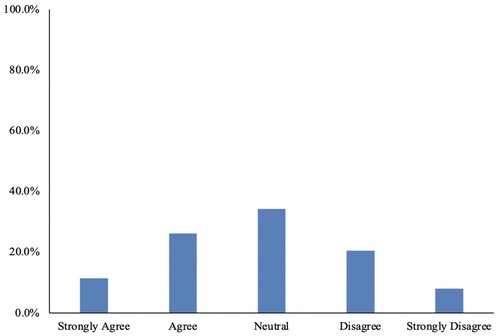

Respondents were ambivalent towards the view that performance analysis courses had provided them with learning to appear trustworthy. Over a third agreed or strongly agreed whereas 28.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed (). To contextualise the efficacy of performance analysis courses in this respect, it should be noted that numerous performance analysts reported that they had not formally studied the subject. This may, in part, be due to some of the participants having been working in the industry before formal performance analysis courses were available, although some participants indicated that they had completed undergraduate degrees in sport science and coaching or undertaken industry specific technology qualifications. Some that had taken specific performance analysis courses believed they did little for developing their workplace trustworthiness: ‘No performance analysis courses focus on intangible skills such as building relationships and trust. They are usually skill-based, which I also believe aren't a great reflection of what performance analysts do for their job’ (P52). Another noted: ‘I am not sure that they did, having watched a number of people from the same courses completely obliterate their trustworthiness in teams. I was fortunate enough to be an athlete myself so already having that understanding of tight teams and trustworthiness was helpful and it is part of my culture and upbringing to be professional and trustworthy in any industry’ (P29). Others acknowledged that while the social development of trust was not explicitly addressed by the courses they completed, the practical knowledge and skills learnt from their attendance had helped them to demonstrate their trustworthiness in applied settings. For one respondent the completion of placement activity was considered particularly beneficial: ‘Postgraduate degree involved a full-time placement where I worked within an academy football (i.e. soccer) setting. This placement presented numerous challenges in which I had to demonstrate that I could build relationships with a range of people and be trusted in a new environment’ (P12). Importantly, respondents highlighted a lack of provision within existing formal performance analysis and coaching courses that focused upon interpersonal skills (e.g. friendliness, approachability, honesty, openness, and caring) and personal characteristics (e.g. punctuality, reliability, integrity and being hardworking and diligent). However, some participants highlighted that they had developed these additional skills and competencies through either their own past experiences being a coach or athlete in sport or through valuable placement experiences learning in situ. Therefore, the integration of workplace experiences appears to be an important vehicle to support analyst’s interpersonal skills and character development.

Figure 4. Question – The performance analysis course I have completed adequately developed an ability to effectively present myself in trustworthy ways.

Most performance analysts (80.7%) suggested they felt the education of future practitioners should better prepare them to appear trustworthy (). Survey respondents provided numerous educational recommendations to develop the ability of analysts to effectively present themselves in trustworthy ways to work with others. In addition to developing knowledge of the sport, performance analysis methods and software packages, data visualisation and working to tight deadlines, participants spoke about the importance of developing the social skills of performance analysts. It was suggested that courses need to emphasise that the job entails ‘more than just providing clips and data – it requires building relationships’ (P40) by ensuring that ‘courses must have intra- and inter-personal skills included as essential elements’ (P13). One analyst argued that those responsible for the professional preparation and development of performance analysts must ‘educate analysts on how to work with different types of people and how to effectively present themselves to different personalities’ explaining that ‘education for me developed my hard skills as an analyst, but it was only through experience in the field that I could develop my soft skills, which are arguably more important if you are to be seen as trustworthy’ (P64). This point was reinforced by another analyst who wrote: ‘I think developing soft skills of working with people is extremely important in the education of performance analysis. If your work is accurate but you cannot develop a relationship with staff, you may not survive or be as useful as possible in the role’ (P87).

Figure 5. Question – I believe the education of performance analysts should better prepare practitioners to effectively present themselves in trustworthy ways.

Participants identified several approaches aimed at facilitating these ends. These included ‘making analysts aware of the management team they are working with and identify strategies to enhance trustworthiness over time’ (P14), ‘giving aspiring analysts different scenarios to see how they would react in each one – then talking through the consequences of their actions’ (P9), role playing scenarios that would prepare analysts ‘for real world problems that arise every day in practical environments’ (P11), ‘bringing in other analysts, coaches, and athletes to share their experiences working with performance analysts’ (P59), permitting analysts opportunities to ‘observe a professional environment to see how everything works so they can feel more prepared’ (P21), providing practical experiences ‘vital for the development of these interpersonal skills [as] meeting new people and understanding different dynamics will allow practitioners to learn through experience’ (P12), developing ‘assessments which allow students to reflect on their personal experiences of developing trustworthiness in applied settings’ (P3). With regards to the later suggestion, it was proposed that ‘placements should be mandatory’ (P82). Underpinning these various recommendations was the belief that: ‘Usually courses have content regarding tools and softwares but I have found none that really show you the personality qualities you need to work in professional sport. For me, technical skills are important as they are the pillars for you to reach professional sport but personal skills are the ones that keep you there. Managing people and relationships is very difficult and that is key for you to do your job with all the people you will find in your career. Work under stress and be able to handle it is hard and develop a strong personality is very important in elite environments for many years and don't get burnt out’ (P33). Whilst participants highlighted a lack of contextualised formal training regarding building relationships in the workplace, specifically regarding how to build trust, how to appear trustworthy and the perils of failing to secure trust, a number of suggested future educational strategies were identified. In addition to developing knowledge of the sport, performance analysis methods and working to tight deadlines (e.g. knowledge, ability, and organisational skills), participants also identified that scenario or problem-based learning approaches and critical reflection as being essential educational strategies to facilitate the development of analysts who are capable of building effective work-place trust-dependant relationships and working with others in high pressure and insecure complex high-performance working environments.

Discussion

This study presents original empirical and theoretical insights into the importance performance analysts attach to appearing trustworthy in the workplace. Data gathered from the survey revealed performance analysts’ perceptions about needing to appear trustworthy to a range of key contextual stakeholders; generative forces that influence their needing to appear trustworthy; outcomes associated with being trusted or distrusted; what characteristics analysts seek to convey to appear trustworthy when working with others; as well as situations that require analysts to conceal information to sustain an image of trustworthiness. Collectively these findings advance foundational work into the place of trustworthiness in performance analysts work (Bateman & Jones, Citation2019; Francis et al., Citation2015; Huggan et al., Citation2015; McKenna et al., Citation2018). In doing so, the study also contributes to a growing critical social understanding of sport work in the context of performance sport.

Our findings can be understood in relation to the theorisation of impression management in the organisational science literature. A longstanding research tradition in the social analysis of work and occupations examines the self-presentations of workers or what is commonly referred to as impression management. The theoretical foundations of impression management can be traced back to Goffman’s (Citation1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, with most organisational science scholars defining workplace impression management as behaviours that employees (actors) use to shape how they are seen by working others (targets) (Bolino et al., Citation2016). Consideration of impression management has garnered increasing attention within the social analysis of sport work, however its implications for understanding trustworthiness in sporting places of work remains under-explored. It could be argued that many of the performance analysts were seeking to manage what Elsbach (Citation2004) termed images of interpersonal trustworthiness, which are attempts ‘to be perceived by others as displaying (now and in the future) competence, benevolence, and integrity in one’s behaviours and beliefs’ (p. 275). Here our findings are consistent with DuBrin’s (Citation2011) observation that ‘for many organisational actors, an importance goal of impression management is to be perceived as trustworthy’ explaining that trustworthiness is ‘both a goal, and an antecedent (or contributing factor) to impression management’ (pp. 45–46). Analysts were clearly seeking to convey themselves as trustworthy to coaches, athletes, support staff, other analysts, and management through a process of impression management.

To appear trustworthy to others, analysts spoke of wanting to convey themselves as knowledgeable practitioners who produce accurate and reliable analysis to a high quality and without errors. Analysts also spoke about showing themselves to be punctual and hardworking individuals able to hit agreed deadlines. Respondents discussed the importance of appearing approachable, friendly, and able to hold open and honest discussions in confidence. Our findings here are indicative of Mayer et al.’s (Citation1995) theorisation of the key characteristics of trustworthiness in organisational settings. According to their analysis, three characterises help to secure the trust of working others: (1) ability (i.e. capacity to competently complete tasks), (2) benevolence (i.e. working with others interests at heart), (3) integrity (i.e. demonstrating consistency and working in principled, credible, and congruent ways). A desire to demonstrate ability, benevolence, and integrity were identifiable in the analysts’ responses. Our findings and analysis here build on those reported in the limited research that has been conducted into the social features of performance analysts’ work (Bateman & Jones, Citation2019; Francis et al., Citation2015; Huggan et al., Citation2015; McKenna et al., Citation2018). Numerous favourable working conditions were identified by the analysts as resulting from establishing themselves as trustworthy to working others. These included better working relationships, greater autonomy in their role, increased impact of the work they had completed, progression in current role as well as enhanced employment opportunities. Perceptions of untrustworthiness were thought to negatively impact on analysts’ working relationships, restrict working tasks and practices expected of them, as well as damage their professional reputation which can potentially result in a loss of employment and/or be harmful to the gaining of future employment. The analysts’ desire to present images of interpersonal trustworthiness were therefore driven not only by wanting to be seen as professional in the eyes of others but to secure those benefits associated with being considered worthy of trust while seeking to avoid those consequences that may result from being identified as untrustworthy.

Our findings here can also be understood in relation to McAdams (Citation2013) theorisation of the psychological self. Consistent with McAdams (Citation2013) analysis, the participants were goal directed in their orientation. They demonstrated a desire to obtain, maintain, and advance their performance analysis careers. They not only wanted to become accepted within the professional but establish themselves as competent and impactful practitioners. In short, they were ‘striving for social acceptance (to get along) and social status (to get ahead)’ (McAdams, Citation2013, p. 274). To achieve these ends, the participants managed their workplace conduct in accordance with the social conventions and expectations of their performance analysis role. McAdams (Citation2013) reminds us that controlling one’s performance is one of the primary objectives of social actors, as ‘losing control can sometimes prove disastrous, for not only does the actor thereby ruin the scene, but he or she may also compromise well-being and reputation for the future’ (McAdams, Citation2013, p. 282). Protecting their occupational reputation as a trustworthy performance analyst was clearly of importance to the participants in this study, especially as it related to their continued and/or future employment. To achieve this end, the participants implemented what McAdams (Citation2013) referred to as ‘effortful control’ by performing behaviours aimed at winning social approval of significant others (p. 283). For the self-continuity of their performance analyst identity to be sustained then, participants conformed to perceived occupational expectations through the enactment of trustworthy social performances not only to secure the positive regard of others but pursue their occupational goals and aspirations.

While conveying honesty was considered an important feature of appearing trustworthy towards working others, consistent with Goffman’s (Citation1959) dramaturgical analysis of impression management, some analysts spoke of having to conceal information to sustain their desired images. Analysts spoke of hiding errors in their work from coaches and athletes to avoid appearing vulnerable. However, consistent with DuBrin’s (Citation2011) analysis, many felt it was ‘better to admit mistakes, thereby appearing more forthright and trustworthy’ as a form of protective impression management (p. 128). The analysts also shared how they demonstrated their trustworthiness to management and coaching staff by concealing from athletes data about their performances, attempts to misrepresent performance data and analysis, as well as known contractual and transfer information. When interpreted in light of Goffman’s (Citation1959) theorisation it could be argued that managing others’ impressions of their trustworthiness required some analysts to conceal what Goffman termed secrets discussed with coaches in the backstage region when interacting with athletes on the frontstage. Their decision to retain the secrets of team performances were to demonstrate dramaturgical loyalty to management and coaching staff. Ironically, then, appearing trustworthy to one group of stakeholders required analysts to (on occasion) conceal information that if known to others might cause them to question their trustworthiness.

Future research should seek to build on our findings and analysis by investigating in greater detail each of these areas as they relate to the everyday realities and challenges that performance analysts face when trying to navigate their workplace relations and interactions. Here, consideration should be given towards where analysts find themselves interacting with working others, who they find themselves interacting with, how they interact with these individuals to present themselves as being trustworthy, as well as the intended and unintended consequences of their decisions and actions. We also encourage scholars to develop a much broader programme of research aimed at understanding the everyday social realities of analysts’ work. To achieve this end, the field might usefully consider related critical social scholarship that has been conducted in relation to other sport workers including coaches, strength and conditioners, sport psychologists, and athletes. Here, scholars have not only investigated the impression management strategies that workers implement to garner the trust and respect of others, but also how sport workers judge the trustworthiness of individuals, interact with colleagues they trust and distrust, as well as contribute towards and repair relationship conflict in the workplace (e.g. Gale et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). Researchers have started to explore the micro-political features of sporting places of work (e.g. Gibson & Groom, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021; Haluch et al., Citation2021; Thompson et al., Citation2013) as well as the political astuteness and skills that practitioners require to effectively navigate their work and working relations (e.g. Nelson et al., Citation2022; Potrac et al., Citation2022), which can include managing their emotions in line with occupational feeling and display rules (e.g. Magill et al., Citation2017; Nelson et al., Citation2013; Potrac et al., Citation2017). Scholarship has also begun to investigate the impacts of perceived precarity (i.e. insecurity about employment, contract, pay and/or employment rights) on how practitioners manage their work, including workplace relations and interactions (e.g. Gilmore et al., Citation2018; Ives et al., Citation2021; Roderick, Citation2006), as well as recognise the importance of studying how employment conditions and working relationships variously impact on the health and wellbeing of the sporting workforce (e.g. Roderick et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2020). It seems particularly important that such insights also be generated in relation to the work of performance analysts, especially if the field is to develop the knowledge necessary to appropriately educate, develop, and support its workforce.

Practical applications

Our findings have important practical implications. Survey respondents were clearly of the opinion that performance analysis courses need to better develop the soft skills of its workforce, thus permitting analysts to demonstrate their trustworthiness more effectively in the workplace. Stakeholders actively involved with the development of professional standards and endorsed educational provision are encouraged to place greater emphasis on the development of analysts’ social skills. It is hoped that this will permit neophyte analysts to more easily develop effective working relations that maximise the impact of their performance analysis work. Recommendations presented by participants in this study offer a useful starting point. Findings from the present study highlighted that courses should seek to take better account of the social aspects of performance analysts’ work, including how they present themselves as trustworthy to secure the ‘buy-in’ of working others. The professional preparation and development of performance analysts is a somewhat fragmented space. A rising number of higher education institutions are offering undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in performance analysis and related areas of study, although the availability of such courses varies between countries. Providers of performance analysis software continue to expand the services they offer, including the provision of courses and educational resources. Sport specific performance analysis certification programmes are starting to be offered by some national governing bodies of sport. In its capacity as the governing body for performance analysts, the International Society of Performance Analysis of Sport (ISPAS) clearly has an important role to play in relation to the education, continuing professional development, and accreditation of its global workforce. In the context of Britain, a British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences (BASES) special interest group for performance analysis convened for the first time in 2022. Among its strategic objectives was the aspiration to ‘work collaboratively with ISPAS, education providers, national governing bodies, and elite sport organisations to review, maintain and develop professional standards, clear accreditation processes and career development frameworks that support members progress and professional recognition’ (BASES, Citationn.d.).

As identified by the participants in this study, performance analysis courses have tended to focus on the development of hard skills (e.g. scientific method of collecting and analysing performance data), with limited attention given to the development of important soft skills (e.g. personal characteristics, interpersonal skills, building productive working relations). The findings of the present study, alongside others that have started to investigate the social features of performance analysis work, clearly demonstrate the need to better prepare analysts for the social realities of working environments as well as equip them with those social sensibilities that will enable them to see, understand, and navigate high-performance sporting work-place contexts more effectively. Here, performance analyst researchers and educators might consider the potential utility of organisational science scholarship demonstrating the importance of developing what has been variously referred to as political skill (Ferris et al., Citation2005), political savvy (Chao et al., Citation1994), political acumen (Perrewé & Nelson, Citation2004), political nous (Baddeley & James, Citation1990), socio-political intelligence (Burke, Citation2006), political sensitivity (Vredenburgh & Maurer, Citation1984), and political astuteness (Hartley et al., Citation2015). Social sensibilities identified by scholars in this area of academic inquiry include the development of important personal skills, the ability to strategically read industry and organisational trends as well as people and situations, effectively networking to build productive alignments and alliance, and executing interpersonal influence for the benefit of self, working others, and employers (Ferris et al., Citation2005; Hartley et al., Citation2015). Those interested in the professional preparation and development of performance analysts (as well as other sport workers) would likely benefit from giving greater consideration towards those soft skills required by its workforce and how these might be developed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank those performance analysts that completed our survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baddeley, S., & James, K. (1990). Political management: Developing the management portfolio. Journal of Management Development, 9(3), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621719010134788

- BASES. (n.d.). New special interest group in performance analysis. https://bases.org.uk/article-new_special_interest_group___performance_analysis.html.

- Bateman, M., & Jones, G. (2019). Strategies for maintaining the coach-analyst relationship within professional football utilizing the COMPASS model: The performance analyst’s perspective. Frontiers Movement and Science and Sport Psychology, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02064

- Bolino, M., Long, D., & Turnley, W. (2016). Impression management in organizations: Critical questions, answers, and areas for future research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 377–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062337

- Burke, R. J. (2006). Why leaders fail: Exploring the darkside. International Journal of Manpower, 27(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720610652862

- Chao, G. T., O'Leary-Kelly, A. M., Wolf, S., Klein, H. J., & Gardner, P. D. (1994). Organizational socialization: Its content and consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(5), 730–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.5.730

- DuBrin, A. J. (2011). Impression management in the workplace: Research, theory and practice. Routledge.

- Elsbach, K. D. (2004). Managing images of trustworthiness in organizations. In R. M. Kramer, & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 275–292). Russell Sage.

- Ferris, G. R., Davidson, S. L., & Perrewé, P. L. (2005). Political skill at work: Impact on work effectiveness. Davies-Black Publishing.

- Francis, J., Molnar, G., Donovan, M., & Peters, D. M. (2015). “Trust within a high performance sport: A performance analyst’s perspective.” In: BASES Conference 2015, 1–2 December 2015, St. George’s Park, Burton upon Trent.

- Gale, L., Ives, B., Potrac, P., & Nelson, L. (2019). Trust and distrust in community sports work: Tales from the ‘shopfloor’. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2018-0156

- Gale, L., Ives, B., Potrac, P., & Nelson, L. (2022). Repairing relationship conflict in community sport work: “offender” perspectives. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2127861

- Gibson, L., & Butterworth, A. (2023). Micropolitics and working as a performance analyst in sport. In A. Butterworth (Ed.), Professional practice in sport performance analysis (pp. 106–119). Routledge.

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2018). The micro-politics of organizational change in professional youth football: towards an understanding of the “professional self”. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(1-2), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1497527

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2019). The micro-politics of organisational change in professional youth football: Towards an understanding of “actions, strategies and professional interests”. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954118766311

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2020). Developing a professional leadership identity during organisational change in professional youth football. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 12(5), 764–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1673469

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2021). Understanding ‘vulnerability’ and ‘political skill’ in academy middle management during organisational change in professional youth football. Journal of Change Management, 21(3), 358–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2020.1819860

- Gilmore, S., Wagstaff, C., & Smith, J. (2018). Sports psychology in the English premier league: ‘It feels precarious and is precarious’. Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), 426–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017017713933

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor.

- Groom, R., & Cushion, C. (2004). Coaches’ perceptions of the use of video analysis: A case study. The FA Coaches Association Journal - Insight, 3(7), 56–58.

- Groom, R., Cushion, C., & Nelson, L. (2012). Analysing coach-athlete ‘talk in interaction’ within the delivery of video-based performance feedback in elite youth soccer. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 4(3), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.693525

- Groom, R., Cushion, C. J., & Nelson, L. (2011). The delivery of video-based performance analysis by England youth soccer coaches: Towards a grounded theory. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.511422

- Haluch, P., Radcliff, J., & Rowley, C. (2021). The quest for professional self-understanding: Sense making and the interpersonal nature of applied sport psychology practice. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(6), 1312–1333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1914772

- Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and trustworthiness. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hardin, R. (2006). Trust: Key concepts. Polity Press.

- Hartley, J., Alford, J., Hughes, O., & Yates, S. (2015). Public value and political astuteness in the work of public managers: The art of the possible. Public Administration, 93(1), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12125

- Huggan, R., Nelson, L., & Potrac, P. (2015). Developing micropolitical literacy in professional soccer: A performance analyst’s tale. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(4), 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2014.949832

- Hughes, M., & Franks, I. M. (1997). Notational analysis of sport. E&FN Spon.

- Ives, B. A., Gale, L. A., Potrac, P., & Nelson, L. J. (2021). Uncertainty, shame and consumption: negotiating occupational and non-work identities in community sports coaching. Sport, Education and Society, 26(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1699522

- James, N. (2006). Notational analysis in soccer: past, present and future. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 6(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2006.11868373

- Jones, R., Armour, K., & Potrac, P. (2004). Sports coaching cultures: From practice to theory. Routledge.

- Kojman, Y., Beeching, K., Gomez, M. A., Parmar, N., & Nicholls, S. B. (2022). The role of debriefing in enhancing learning and development in professional boxing. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 22(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2022.2042640

- Kramer, R. M., & Cook, K. S. (2004). Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches.

- Luhman, N. (2017). Trust and power. Polity Press.

- Magill, S., Nelson, L., Jones, R., & Potrac, P. (2017). Emotions, identity, and power in video-based feedback sessions: Tales from women’s professional football. Sports Coaching Review, 6(1), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2017.1367068

- Martin, D., Donoghue, P. G., Bradley, J., & McGrath, D. (2021). Developing a framework for professional practice in applied performance analysis. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 21(6), 845–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2021.1951490

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- McAdams, D. P. (2013). The psychological self as actor, agent, and author. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(3), 272–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612464657

- McKenna, M., Cowan, D. T., Stevenson, D., & Baker, J. S. (2018). Neophyte experiences of football (soccer) match analysis: A multiple case study approach. Research in Sports Medicine, 26(3), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2018.1447473

- Middlemas, S., & Harwood, C. (2018). No place to hide: Football players’ and coaches’ perceptions of the psychological factors influencing video feedback. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1302020

- Middlemas, S. G., Croft, H. G., & Watson, F. (2018). Behind closed doors: The role of debriefing and feedback in a professional rugby team. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117739548

- Nelson, L., Potrac, P., Gale, L., Ives, B., & Conway, E. (2022). Political skill in community sport coaching work. In B. Ives, P. Potrac, L. Gale, & L. Nelson (Eds.), Community sport coaching: Policies and practice (1 ed, pp. 197–209). Routledge.

- Nelson, L., Potrac, P., Gilbourne, D., Allanson, A., Gale, L., & Marshall, P. (2013). Thinking, feeling, acting: The case of a semi-professional soccer coach. Sociology of Sport Journal, 30(4), 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.30.4.467

- Nelson, L., Potrac, P., & Groom, R. (2014). Receiving video-based feedback in elite ice-hockey: a player's perspective. Sport, Education and Society, 19(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.613925

- Nicholls, S. B., James, N., Bryant, E., & Wells, J. (2018). Elite coaches’ use and engagement with performance analysis within Olympic and Paralympic sport. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 18(5), 764–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2018.1517290

- Nicholls, S. B., James, N., Bryant, E., & Wells, J. (2019). The implementation of performance analysis and feedback within Olympic sport: The performance analyst’s perspective. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954118808081

- O’Donoghue, P. (2006). The use of feedback videos in sport. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 6(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2006.11868368

- Perrewé, P. L., & Nelson, D. L. (2004). Gender and career success: The facilitative role of political skill. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.09.004

- Potrac, P., Hall, E., McCutcheon, M., Morgan, C., Kelly, S., Horgan, P., Edwards, C., Corsby, C., & Nichol, A. (2022). Developing politically astute football coaches: An evolving framework for coach learning and coaching research. In T. Leeder (Ed.), Coach education in football: Contemporary issues and global perspectives (pp. 15–28). Routledge.

- Potrac, P., Jones, R., & Armour, K. (2002). ‘It’s all about getting respect’: The coaching behaviours of an expert English soccer coach. Sport, Education and Society, 7(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357332022000018869

- Potrac, P., Smith, A., & Nelson, L. (2017). Emotions in sport coaching. Routledge.

- Robbins, G. B. (2016). What is trust? A multidisciplinary review, critique and synthesis. Sociology Compass, 10(10), 972–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12391

- Roderick, M. (2006). A very precarious profession: Uncertainty in the working lives of professional footballers. Work, Employment and Society, 20(2), 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006064113

- Roderick, M., Smith, A., & Potrac, P. (2017). The sociology of sports work, emotions and mental health: Scoping the field and future directions. Sociology of Sport Journal, 34(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2017-0082

- Ronglan, T. L. (2011). Social interaction in coaching. In R. L. Jones, P. Potrac, C. Cushion, & L. T. Ronglan (Eds.), The sociology of sports coaching (pp. 151–165). Routledge.

- Smith, A., Haycock, D., Jones, J., Greenough, K., Wilcock, R., & Braid, I. (2020). Exploring mental health and illness in the UK sports coaching workforce. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249332

- Sztompka, P. (1999). Trust: A sociological theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, W. G., Potrac, P., Nelson, L. J., Jones, L., & Groom, R. (2017). An elite hockey player's experiences of video-based coaching: A poststructuralist reading. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(1), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215576102

- Thompson, A., Potrac, P., & Jones, R. (2013). I found out the hard way’: micro-political workings in professional football. Sport, Education and Society, 20(8), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.862786

- Tracy, S. J. (2018). A phronetic iterative approach to data analysis in qualitative research. Journal of Qualitative Research, 19(2), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2018.19.2.61

- Tracy, S. J. (2020). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

- Vredenburgh, D. J., & Maurer, J. G. (1984). A process framework of organizational politics. Human Relations, 37(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678403700103

- Ward, P. R. (2019). Trust, what is it and why do we need it. In M. H. Jacobsen (Ed.), Emotions, everyday life and sociology (classical and contemporary social theory) (pp. 13–12). Routledge.

- Williams, S., & Manley, A.. (2016). Elite coaching and the technocratic engineer: Thanking the boys at Microsoft!. Sport, Education and Society, 21(6), 828–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.958816