ABSTRACT

During the coronavirus pandemic, internet spaces became important sites of teaching PE remotely. This paper contributes to a better understanding of the emergency online pedagogies transpiring in these internet spaces and the role that digital resources gained in them. We focus on webpages on the platform Padlet.com, which have been identified but not yet investigated as relevant spaces for pedagogical encounters in German-speaking remote PE. Using a theory of practice approach to pedagogy and focusing on discursive practices of responsibilization, we investigate which responsibilities are claimed for PE as a subject, for teachers, students and digital resources on these webpages, and how these parties are thereby related to each other and positioned as recognizable subjects/actors of remote PE. Our qualitative discourse analysis of 14 Padlet webpages (755 posts combined) reveals that the online pedagogy on these webpages is characterized by the discursive positioning of (i) PE as being responsible for activity and sport under special conditions, (ii) teachers as subjects responsible for organizing PE and activating students while delegating pedagogical responsibilities to them and to digital resources, (iii) students as subjects who should care for themselves by taking responsibility for the processes and results of their physical activities and (iv) digital resources as important actors located between education, sport culture and internet economy. Discussing these results, we argue that exploring the actual ways and forms of performing pedagogical responsibility can yield important insights into the social constitution of – increasingly digitized – PE, its social relations, subject positionings and pedagogies.

Introduction

In Germany, lockdowns and school closures due to the pandemic led to two extended periods (spring 2020, winter 2020/2021) of remote physical education (PE). The initial period lacked clear guidelines, and the digital infrastructure of German schools was subpar in international comparison (Eickelmann et al., Citation2019).Footnote1 PE teachers had to improvise digital emergency pedagogies, finding new forms of instruction and content using various digital media to engage students at home. This gave rise to novel interactions between teachers, learners and subject matter in spatially, temporally and personally decentralized PE classrooms, which extended across living rooms, outdoor venues, video conference rooms and other online platforms while introducing new participants such as family members or internet personalities.

With PE facing similar challenges in many other countries, international research suggests that the coronavirus pandemic brought significant changes to the pedagogical practices, approaches and relations of PE (Howley, Citation2022; López-Fernández et al., Citation2023). Thus, research that enhances our understanding of these pandemic-induced PE pedagogies is needed to grasp the impact of these periods on the subject going forward. While many studies focus on educators’ perspectives (e.g. Cruickshank et al., Citation2022; Howley, Citation2022; López-Fernández et al., Citation2023; Nyberg et al., Citation2022; Roth & Stamm, Citation2023), additional research emphasizes the importance of scrutinizing the impact of digital resources, external influences and online platforms on remote PE (Lambert et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). Expanding on the latter perspective, this paper explores the emergency pedagogy within one online space – webpages on Padlet.com (Padlets). Padlets are digital pinboards housing posts that can share words, images, documents, videos or links. Amid school closures, German PE teachers created Padlets to collect online resources like movement-engaging online videos and share them with students. Thus, these webpages emerged as platforms for pedagogical interactions to facilitate remote PE. Yet despite being identified (Opper et al., Citation2021, p. 448), they await in-depth research.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a better understanding of the PE emergency pedagogy that was enacted discursively on digital pinboard webpages on Padlet.com. For this, we adopt a theory of practice perspective that focuses on how pedagogies are constituted through discursive practices of responsibilization (Kuhlmann & Drerup, Citation2023; Wrana, Citation2006). Drawing on a qualitative discourse analysis of 14 Padlets, we reconstruct how teachers, digital resources and external actors claim, assign and perform specific responsibilities within remote PE and thereby establish pedagogical relations between themselves, students and subject matter. Our corresponding research questions are:

Which responsibilities are claimed for PE as a subject, for students, teachers and digital resources in the online communication on Padlets?

How are parties related to each other and positioned as recognizable subjects/actors of remote PE through claiming specific responsibilities?

Addressing these questions, our primary aim is a reconstructive one: We seek to empirically unpack the intricate social and semantic constitution of remote PE pedagogy at a specific online site by reconstructing the discursive enactment of pedagogical responsibilities. In relating our results to previous literature, we also consider critical perspectives on neoliberal developments in PE.

Theoretical framework

Our theoretical framework draws on theory of practice approaches to education. These account for the social orders, processes and practices through which pedagogy is constituted as a sociocultural phenomenon in a particular lesson, school subject or educational site (Edwards-Groves, Citation2018; Rabenstein & Drope, Citation2022). In this perspective, PE is prefigured through cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements, the forms and semantics of which are decided primarily in the interwoven doings and sayings of those involved. Through these doings and sayings, actors relate and position themselves to one another and a subject matter as PE teachers and learners to socially constitute a particular pedagogy.

We particularly adopt theory of practice approaches of subjectivation research. Drawing from Bourdieu, Foucault, Butler and newer theories of practice, these approaches pose that the subject status and subjectivities of those involved in pedagogical practice are not pre-existing but constitute themselves in the doings and sayings of this practice (Gellert et al., Citation2023; Ricken et al., Citation2023). This occurs as these doings and sayings function as forms of addressing and recognizing someone as someone (Ricken et al., Citation2023). For instance, when teachers post on Padlets, they speak from the subject position of PE teachers, enact this position and establish what it means to be recognizable as teacher-subjects in this pedagogy.

Recent approaches focus on how pedagogies and their relational subject-positionings emerge through the enactment of pedagogical responsibilities (Kuhlmann & Drerup, Citation2023). Instead of normative concepts of moral relatedness and obligations between teachers and students (Brennan & Noggle, Citation2007), these approaches empirically reconstruct the intricate discursive assigning, claiming and performing of responsibilities within a particular pedagogy (Kuhlmann & Drerup, Citation2023).

Building on these approaches, we examine Padlets as online sites where the emergency pedagogy of German-speaking remote PE was enacted through the discursive practices of parties posting and appearing on these webpages. We explore the social constitution of this online pedagogy by analyzing which responsibilities are claimed for PE as a subject, for students, teachers and digital resources in the discursive practices articulated on these webpages and how these parties are thereby positioned as recognizable subjects and, in the case of the online resources, digital actors of remote PE.

Previous research

Previous theory of practice research has investigated how social order is established in PE lessons according to a ‘game plan’ (Wolff, Citation2016), how social differences are (re-)produced (Schiller et al., Citation2021) or how PE lessons operate at the fringes of education and sporting activity (Schierz & Serwe-Pandrick, Citation2018). Further, these findings are linked to broader (historical) discourses in which PE lessons are constructed as recovery from other school subjects or support for them, with the physical activity of students being positioned at the core of their pedagogy (Schierz & Serwe-Pandrick, Citation2018, pp. 64–67). Practice theory research on other school subjects has started to focus on digitally mediated pedagogies by investigating which responsibilities are delegated to technologies in pedagogical encounters and how these technologies come to participate as digital actors (e.g. Kuhlmann & Thiersch, Citation2023). Similar studies on PE are still lacking.

Research on subjectivation through practices of responsibilization can be found primarily in the field of governmentality research. There, responsibilization, following Foucault, refers to strategies of assigning personal responsibility to produce prudent, actively self-governing subjects (Juhila & Raitakari, Citation2016). Much PE-related critical research relies on this notion to investigate mostly larger forms and orders of knowledge, power and subjectivity, e.g. regarding certain policy discourses and measures (e.g. Alfrey et al., Citation2023; Jette et al., Citation2016).

Some previous research on PE during the coronavirus pandemic follows similar critical perspectives. Existing scholarship pictures remote PE during the pandemic as a disruptive experience that was met with emergency reactions which (re-)produced narrow, traditional, activity-centered and often fitness- and exercise-styled interpretations of PE (e.g. Cruickshank et al., Citation2022; Howley, Citation2022; Lambert et al., Citation2023; López-Fernández et al., Citation2023). The studies indicate that these interpretations go along with responsibilizations of learners as subjects taking care of their own health and fitness and being accountable for an appropriate physical activity. It is criticized that these responsibilizations feature an over-emphasis on physical activity as a means to become or stay healthy, while paying little attention to the cognitive or emotional development of learners (Coulter et al., Citation2023; López-Fernández et al., Citation2023). Analyzing the ‘PE with Joe’ series, Lambert et al. (Citation2022) further expose the ‘heteronormative, classist, ableist and racist assumptions about movement, bodies, knowledge and even what it means to be physically active’ (p. 17) that discursively circulate in these narrow interpretations of PE and corresponding responsibilizations of students. Bowles et al. (Citation2022) show how these responsibilizations connect to overarching discourses in which PE has been constructed as a vehicle for activating and maintaining the health of children and adolescents while increasingly exhibiting a neoliberal orientation and, in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, calling upon PE to promote self-management of the body through exercise (Malcolm & Velija, Citation2020). They further highlight that Joe Wicks presents a ‘living brand and corporate enterprise’ that acted as a digitally mediated PE teacher while ‘launching an entrepreneurially response to an interrelated health and (physical) education crisis’ (Bowles et al., Citation2022, p. 5).

On a broader scale, the points raised in previous research regarding responsibilization in remote PE relate to discussions about neoliberalism, external provision, commercialization, digitalization, social inequalities and PE (Allen et al., Citation2023; Fitzpatrick & Powell, Citation2019; Gard, Citation2014; Sperka & Enright, Citation2019). These discussions critically reflect on the ideas, interpretations and ‘truths’ conveyed, the actors and positions (un-)able to set and influence these ideas, interpretations and ‘truths’ (e.g. students from the positions of consumers), and the voices, agendas and subjectivities thereby privileged or marginalized when market-oriented assumptions and strategies (including assigning personal responsibility) are applied to PE.

While these critical perspectives provide important reference points, they have not exhausted the potential of responsibilization as a framework for reconstructing the relational subject positionings that shape pedagogies as collective and interconnected social enactments. For instance, theory of practice-inspired studies on open and individualized school lessons in Germany show how their pedagogies constitute themselves through practices, in which students are addressed with the expectation to take responsibility for their own work and learning processes, e.g. regarding time management or the use of learning resources (Breidenstein & Rademacher, Citation2017). Research on professional cooperation reveals how teachers or teams position themselves by asserting competencies and responsibilities (Kuhlmann & Moldenhauer, Citation2021). Kuhlmann and Thiersch (Citation2023) explore how digital tools in classrooms create pedagogical relationships by allocating responsibilities among teachers, learners and tools. Additionally, Dietrich et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate how teachers and officials position themselves during the ‘corona crisis’ through claiming or transferring specific responsibilities.

By asking ‘Who is responsible for what?’, we adopt this predominantly reconstructive approach from theory of practice research, which traces how pedagogies and their subject positionings are constituted through relational practices of attributing and enacting responsibilities, while considering the critical perspectives mentioned above when linking our findings to previous research on remote PE during the coronavirus pandemic.

Materials and methods

To address our research questions, we employed Wrana's (Citation2015a, Citation2015b) methodology of analyzing discursive practices – a qualitative approach rooted in Foucault, Butler and contemporary practice and subjectivation theory, which aligns with our theoretical framework.

Data collection

As part of a broader project exploring ‘PE on the internet’ (Rode & Zander, Citation2022), we recognized Padlets as significant online site of remote PE. We progressively compiled a sample of 14 public Padlets (totaling 755 posts) from links, references and online searches (Google searches, combinations of keywords: Padlet, PE, sports, Corona, pandemic, lockdown, homeschooling). Each Padlet served as a single case. We included cases explicitly related to Covid-restricted PE delivery, excluding others like club sports focused Padlets. Following the idea of permanent comparison, we sought ‘simultaneous maximization or minimization of both the differences and the similarities of data’ (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967, p. 55) based on criteria like number of posts, layout and appearance, author, addressees, participation possibilities (commenting, liking, rating posts; creating own posts), school type, wording in title and description. We ceased including new cases when criteria variation was saturated. We saved the Padlets as text and image files. Notably, the communication within these Padlets occurred naturally, independent of our involvement.Footnote2

Data analysis

Following the qualitative discourse analytic approach of Wrana (Citation2015a, Citation2015b), we analyzed the formulation of a title, a description or a post as discursive acts that, first, produce the phenomena which they explicitly or implicitly speak of (e.g. the goals of remote PE) by performatively posing a particular knowledge construction as recognizable. Second, this draws on certain orders of knowledge (e.g. regarding PE or the coronavirus pandemic) and poses them as (in-)valid or (il-)legitimate. Third, each discursive articulation positions the parties involved in relation to these constructions and orders of knowledge as well as to each other by addressing them in certain ways (e.g. with the expectation to stay fit) and by directly or indirectly constructing certain norms for gaining recognizability (e.g. as self-responsible students) (Wrana, Citation2015a, p. 128). The discursive articulations on the Padlets thus not only have phenomenon- and reality-constituting effects but also subjectivizing effects by asserting certain necessities and possibilities for different parties to be recognizable as subjects of remote PE (Wrana, Citation2015a, p. 128).

Our first step of analysis was to open-code the textual and visual articulations in our material using MAXQDA software and then develop the codes into categories. We were guided by the following questions: Who is (not) speaking/showing? Who is (not) being spoken to/about? What is (not) talked about or what is (not) shown? What is striking about the speaking and showing in this online space? In this first step, it became apparent that the discursive invoking of certain responsibilities facilitated how teachers, students and digital resources were related and positioned in the context of remote PE.

To explore this finding more thoroughly, our second step was a detailed sequential analysis (Wrana, Citation2015a). We selected one webpage, which we characterized as particularly rich after coding, as an anchor case, interpreted the title, description, layout and all posts sequentially, and reconstructed the discursive figures that characterize this case. A discursive figure is the semiotic and pragmatic structure of an articulation that constructs the objects of speech and their meaning as well as positions the speaking and the spoken to/about subjects in a specific way (Wrana, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). We then analyzed all 13 other cases in the same way and compared all cases with each other to identify recurring figures or patterns of invoking, attributing and claiming specific responsibilities. These are presented in the following section in an aggregated form that includes illustrative quotes from the data material.Footnote3

Results: who is responsible for what in remote PE?

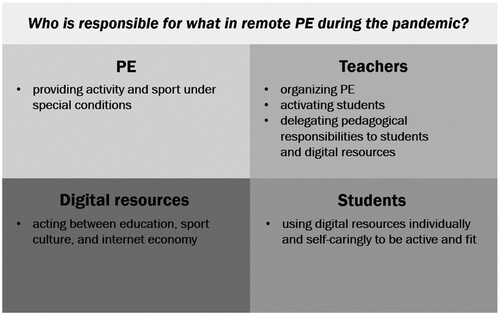

We found that the emergency pedagogy of remote PE transpiring on German-speaking Padlets is characterized by the following – dominant and largely unchallenged – discursive positionings ().

PE being responsible for activity and sport under special conditions

On the Padlets, the discursive claiming of specific responsibilities is embedded in an overarching construction of PE as being responsible for taking care of activity and sport during the special conditions of the coronavirus pandemic.

The headlines and descriptions of the Padlets as well as many posts refer directly to the coronavirus pandemic and construct it as an exceptional situation that has far-reaching effects on different areas of society. The pandemic affects everyone and entail fundamentally different conditions for PE, which are marked as the reason why the Padlets were set up and function as an online space for remote PE. The ‘special conditions’ (CP13, title)Footnote4 of the pandemic are characterized as restrictive and stressful, e.g. by repeatedly referring to ‘at home’ as the central space of action (CP1, title), by addressing a lack of opportunities, e.g. to play with friends (CP1, post 14), by associating the situation at home with work (CP3, post 1) or boredom (CP7, post 32) or by identifying ‘exercises, tips, and podcasts on the topics of stress management, relaxation, healthy eating and sufficient exercise’ as being ‘certainly useful right now’ (CP1, post 27). Crucially, these circumstances are characterized as having negative effects on the activity levels, emotional conditions as well as physical capabilities and capacities of people, through, for example, metaphors like ‘getting rusty’:

Sports ideas for lockdown […] So you don't get rusty:)) (CP3, title and description)

What can we do right now to stay fit, motivated, in a good mood, and performing at our best? (CP1, description)

Thus, at the heart of the online communication on the Padlets is a discursive construction where PE is primarily responsible for encouraging and promoting physical activity. Such a construction has been highlighted in existing research on pandemic PE with critique focusing on the instrumentalization of the school subject, the reproduction of ‘dominant, white, masculinist patriarchal knowledge as particular kinds of truths’ (Lambert et al., Citation2023, p. 10), and the lack of educational and empowering aspects (Bowles et al., Citation2022; Lambert et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). Here, this interpretation of PE is (re-)produced in the discursive articulations of PE teachers as well as ‘external’ digital resources and is tied to a problem construction of the ‘corona circumstances’ (CP4, description) that cites overarching, at times moralizing discourses of concern for body and activity during the pandemic (Malcolm & Velija, Citation2020).

Notably, these discursive constructions are not elaborated, explained or justified on the Padlets, but simply taken for granted. This results in an emergency online pedagogy where there is no discursive space to question or challenge this narrow and inequitable (Lambert et al., Citation2022) construction of remote PE and its core responsibility.Footnote5 At the same time, this taken-for-granted mode of communication can be considered productive for dealing with the uncertainties, insecurities and burdens that remote PE meant for teachers and students (Lambert et al., Citation2023), because invoking a shared fate and a clearcut resulting task can function as a discursive means to establish a sense of community and purpose.

Teachers as organizing, activating and delegating subjects

Self-positioning

In the context of the general responsibility of remote PE just outlined, teachers claim for themselves the responsibility for certain aspects of organizing remote PE and activating students while performatively delegating responsibilities central to pedagogical encounters to students and digital resources.

A recurring pattern is that the teachers posting on the Padlets highlight the importance and necessity of exercising, being active and playing sports in spite or because of the special ‘corona circumstances’ (CP4, description):

[…] since currently many sports offers unfortunately must be cancelled, you can find some suggestions here. Also in these special times, it is important to be active regularly. Let's go …  (CP6, post 1)

(CP6, post 1)

Regarding the actual conducting of remote PE, the main responsibilities that teachers perform are to collect digital resources and to make them available to the students in a structured way (e.g. according to age, grade level or content areas). This is done in the mode of offering ‘tips’ (CP1, description), ‘ideas’ (CP2, description; CP4, description), ‘sports ideas’ (CP3, title), ‘physical education ideas and examples’ (CP8, title), ‘movement ideas’ (CP10, post 3) or ‘suggestions’ (CP2, description; CP6, post 1) through encouraging and motivating semantics: ‘seize this chance!’ (CP9, description). In this way, the teachers show themselves responsible for activating students.

Additionally, they emphasize the need for choosing exercises according to one’s age and ability and for ensuring they are done appropriately and safely:

Take care of your health. We've posted ideas for you to get moving at home. All exercises and offers are suggestions! Listen to your body and stop immediately if something hurts you during an exercise or you have a funny feeling about it. All the activities are marked for which grades they are best suited. The older students can also participate in the exercises for the younger ones without any problems. In almost all exercises, you can make it easier or harder for yourself. (CP3, post 2, emphasis in original)

Note to all students: Sports activities should only be undertaken in consultation and after prior clarification with your parents or guardians and, if necessary, in consultation with a doctor depending on your state of health. (CP7, post 2, emphasis in original)

Additionally, the teachers’ self-positioning is marked by a second figure of delegation in which they attribute the responsibility for actually arranging, instructing and staging movement tasks and exercises to facilitate learning, which traditionally also falls on teachers and might be considered teaching in a narrow sense, to the digital resources:

It [the content of this Padlet] is mainly videos that enable sports activities at your own home. (CP7, post 1)

Learn your first [dance] steps to create your own choreography. (CP5, post 8)

In these figures of delegation that characterize the teachers’ self-positioning, it becomes particularly obvious that responsibilization must be understood as a discursive practice of relational subject positioning. Hence, we will revisit them in the sections on students and digital resources.

External positioning by superior actors

We now present how teachers are addressed by other actors who are positioned higher in the hierarchy of the educational system. Our sample contains two Padlets that do not speak primarily to students, but to teachers: one is authored by a state authority for schools and teacher training (CP4) and a second one by an individual teacher who positions himself in proximity to such official institutions (CP8). These two Padlets also feature posts presenting digital movement-engaging resources to teachers, but these posts are formulated in a more factual and less activating manner than in the Padlets addressed to students. Additionally, these two Padlets contain links to official documents or information pages on official requirements for schools and PE during the coronavirus pandemic, reviews of specialist literature, references to teacher training courses or a digital ‘equipment room manager’ (CP4, post 78). In the communication on these webpages, teachers are addressed with the responsibility of planning and organizing PE under the specific conditions of the coronavirus pandemic:

The content [of this Padlet] is intended to assist in lesson planning, especially in the current time of the pandemic. (CP8, description)

The examples uploaded by users are intended as suggestions and are subject to limited review for legal and professional/pedagogical quality. In particular, check the lesson examples against current pandemic-related guidelines from the state and your region or school district. (CP8, post 1)

Students as self-caring subjects

The discursive construction of remote PE that we presented in the first results section includes a differential discursive figure in which PE teachers and students are both positioned as part of a positively marked group of those who are doing something and staying active in the face of the ‘corona circumstances’ (CP4, description). Together with the discursive figures of delegation that we outlined in the previous section, this results in students being positioned as subjects who are responsible for using the collected digital resources to take care of their individual activity and fitness.Footnote6

This positioning becomes clear when looking at how students are addressed directly by teachers as well as indirectly by the posted digital-resources and the messages they display. As mentioned, the digital resources are labeled by teachers as offerings, ideas or suggestions that cover a wide variety of movement practices, are differentiated by age group or skill level and are updated constantly:

Since PE is now not taking place anymore, you can find different voluntary movement offers here. The offers are amended and updated regularly. Use them and seize this chance! (CP9, description)

Why not try out our tips? You are also welcomed to test the ideas of the older or younger classes. (CP1, description)

What sports goals did you set or already accomplish in the corona time? Can you also do the other challenges? (CP1)

Who can keep it up the whole week? (CP1)

Thus, our data material shows how neoliberal responsibilizing positionings of students, which are also highlighted in existing studies on remote PE, are specifically constructed in the online space of Padlet webpages: On the Padlets, a concern for one’s body and activity, which we outlined in the first results section and which has been shown as a significant aspect of the public problem discourse during the coronavirus pandemic (Malcolm & Velija, Citation2020), is discursively assigned to students as an expected form of self-care. The diverse group of students is addressed with highly demanding expectations of choosing, conducting, evaluating and modifying physical activities that are communicated as taken-for-granted.

In this context, it is important to note that the Padlets represent an online space in which PE teachers – and, through their posts, also digital resources – speak, while students make virtually no use of the opportunities to comment on posts or create their own posts, which are available in some cases. In this online space, students remain in the position of those who are spoken to or about, and who do not respond to the responsibilizing positionings with (affirmative, contesting or subverting) forms of self-positioning.

Digital actors between education, sport culture and internet economy

The digital resources play an important role in all of this. As the main web content that is shared on the Padlets, they consist of online videos or streams, websites or PDF documents from sports federations and clubs, ministries of education, health insurance companies or individual actors that span a broad range of sports-related subject areas but are heavily focused on fitness content. Since the Padlets function as online spaces for instructional communication and appear as makeshift digital curricular, these digital resources come to represent the subject matter of the online pedagogies transpiring on these webpages. Beyond this, they – and the providers, protagonists and personas associated with them – also emerge as central actors of this online pedagogy.

The digital resources predominantly feature formats that present, demonstrate, instruct and explain sports activities, movements tasks, methodical steps or exercises for viewers to join into, imitate or try out themselves either synchronously or asynchronously. In their thumbnails, captions or self-labeling, they claim to promote, support or cause movement learning, fitness improvement or skill development:

Learn handstand at home – without material or help – preliminary exercises and learning steps. (CP5, post 14)

Your way to the perfect handstand #1 – with Marcel Nguyen. (CP8, post 44)

We make children strong – fit with DHB, episode 6. (CP12, post 13)

Looking more closely at how the digital resources present themselves as such actors, we found that their self-presentation positions them at the intersection of education, sport and active lifestyle culture and contemporary internet economy.

As illustrated by the quotes displayed above that refer to a well-known German gymnast (Marcel Nguyen) and the German Handball Federation (DHB), the discursive strategies of claiming the agency and responsibility to stage, instruct and facilitate movement learning or fitness improvement include that the digital resources identify themselves as institutions or persons from the field of movement and sport, that they advertise with experts or well-known personalities from this field, that the providers themselves can be seen as personal actors authentically being active in front of the camera, and that they do not address the viewers primarily as students, but rather as children and youth who are meant to be interested in sports, exercise or training. Through all this as well as through their often modern and trendy overall appearanceFootnote7 and concise activating semantics, the digital resources position themselves as actors of sports and active lifestyle culture.

At the same time, employing experts or well-known persons and turning oneself into a persona or brand that authentically embodies a certain field of interest are strategies of generating trust, attributions of competency and credibility that have long been used in marketing communication (Willems & Jurga, Citation1998) and are also part of the commercial logic geared towards gaining attention, views, clicks and likes that governs contemporary internet and social media cultures (Aronczyk & Powers, Citation2010; Poell et al., Citation2022). In their thumbnails, captions, videos and overall semantics, many of the digital resources, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly, vie for clicks, views or likes, reveal or promote commercial interests, present themselves as a brand and thereby appear as actors of these commercial internet cultures.

Previous scholarship has discussed the entangling of commercial interests and PE as an aspect of neoliberalism and digitalization shaping PE (Allen et al., Citation2023; Fitzpatrick & Powell, Citation2019; Gard, Citation2014; Sperka & Enright, Citation2019). In this context, prior research on PE during the coronavirus pandemic has mainly focused on one specific example (‘PE with Joe’) to discuss how ‘external’ actors brought commercial interests, influencer tactics and popular culture into the remote PE classroom (Bowles et al., Citation2022; Lambert et al., Citation2022). Our analysis expands on this prior research by showing how the online discourse on Padlet webpages attributes specific responsibilities to a broad range of digital resources, awarding them a crucial agency within remote PE. Through this form of responsibilization, remote PE is positioned at the intersection of education, sports and active lifestyle culture and contemporary internet economy.

Discussion

Focusing on German-language Padlet webpages, we have shown how – in a time in which the PE classroom was decentered spatially, temporally and content-wise – internet spaces became important sites of organizing remote PE, addressing digital resources to students and constituting specific emergency online pedagogies. Our study contributes to a better understanding of such internet spaces and their online pedagogies. Using a practice theory perspective and a discourse analytical approach, we found that the online pedagogy transpiring on Padlets is characterized by remote PE being positioned as being responsible for providing physical activity and sports during the particularly ‘concerning’ situation of the pandemic. This concern is reflected in the discursive positioning of students as subjects who should care for themselves by taking responsibility for the processes and results of their physical activities. PE teachers provide the framework for this by acting as subjects who organize remote PE, activate students, but also delegate central responsibilities to them and to digital resources. These digital resources not only represent the subject matter through which the students’ self-care can be achieved, but also emerge as pedagogical actors responsible for aspects of ‘teaching’ remote PE in a narrow sense. In their self-presentation, these actors position themselves – and, by default, this online pedagogy of remote PE – at the intersection of education, sports and active lifestyle culture, and internet economy.

Relating these results to existing scholarship, our study contributes to a better understanding of the continuities and changes that come with the digitalization of PE. Under the specific circumstances of digitally mediated remote education, the emergency online pedagogy transpiring on Padlets appears as a coming-together of larger discourses on body, movement and sports during the pandemic (Malcolm & Velija, Citation2020), of long-established activity-centered and functional interpretations and legitimations of PE (e.g. Schierz, Citation2009, Citation2013), and of newer neoliberal developments that promote the self-government of students while bringing external providers, their economic interests, market-based solutions and lifestyle-framed ideological work into PE (Bowles et al., Citation2022; Fitzpatrick & Powell, Citation2019). We have shown how the constitution of this online pedagogy is a discursive ‘work’ performed not only by the messages and appearances of the digital resources but also by the online ‘classroom communication’ of PE teachers and by the Padlet webpages as online spaces in which students remain mostly silent.

The limitations of our study pertain to its cross-sectional research design, its focus on the German-speaking context, on Padlet webpages as one specific online site and, in relation to the specific conditions of this site, a missing view of students’ practices. Further research could feature longitudinal designs to trace actual continuities and changes. It should extend beyond the German-speaking context, and it should consider other online as well as offline sites of remote but also of regular digitalized PE. Future research should also explore if there were/are other avenues for students to exercise agency. It should ask how exactly the digital resources are used. And it should continue to investigate to what extend these digital resources are part of a comprehensive change of PE as a subject, e.g. by further exploring the perspectives of teachers and students. This should also include analyzing the (re-)production of social inequalities in digital/online PE regarding gender, class, socioeconomic status, body shape/size and race, which we have explored in Rode and Zander (Citation2023).

The central role that responsibilizations played in the online pedagogy we investigated led us to employ an empirically oriented theory of practice perspective that considers discursive practices of assigning und claiming specific responsibilities to be the medium in which social positionings and relations between teachers, learners, other potential actors and subject matter constitute themselves. Our paper thereby raises awareness for the empirical research gap that normative philosophical dialogue about pedagogical responsibility and its legitimacies should be complemented by ‘studies that […] investigate the actual forms and ways of performing pedagogical responsibility’ (Kuhlmann & Drerup, Citation2023, p. 3). Contributing to addressing this research gap, our paper demonstrates how an empirical focus on practices of responsibilization can contribute to research on the social constitution of the pedagogies and subjectivities of PE.

The implications of our study for pedagogical practice also depart from this approach to practices of responsibilization. For physical educators, the question ‘Who is responsible for what?’ should not only lead to reflections on ethical issues or on how to organize PE, but also to reflections on the social relations and subject positionings that are constituted through attributing and claiming certain tasks, competencies and authorities. How responsibility is established, which practices are important for this, and how digital technologies and resources (re-)configure the social relations and subject positionings – and with them the pedagogy – of increasingly digitalized PE, are pressing questions that warrant further exploration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Referring to a relatively poor quality and quantity of available technical infrastructure, such as wireless internet access or learning management systems, and a lack of technical and pedagogical support (Eickelmann et al., Citation2019, p. 27).

2 Ethics approval granted by Salzburg University ethics commission (reference number EK-GZ 27/2021).

3 Data was analyzed in German, all translations were done by the authors from German specifically for this paper.

4 We refer to our data material via the code we assigned to the case (Padlet) and then to the webpage title or description, or to the specific post via the number assigned to each post on the webpage itself.

5 In our overarching project, we found that the comments sections of YouTube-Videos used in digital home-schooling are an example of a discursive space where students questioned, criticized, or deconstructed such narrow interpretations of remote PE.

6 Some results presented in this sub-section are discussed more extensively and within a different overall argumentation in Rode and Zander (Citation2023).

7 Many of the digital resources incorporate the latest developments and styles in areas such as fashion, technology, language, or design, which are presumably perceived by many as contemporary, attractive, and desirable.

References

- Alfrey, L., Lambert, K., Aldous, D., & Marttinen, R. (2023). The problematization of the (im)possible subject: An analysis of health and physical education policy from Australia, USA and Wales. Sport, Education and Society, 28(4), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.2016682

- Allen, J., Quarmby, T., & Dillon, M. (2023). To a certain extent it is a business decision: Exploring external providers’ perspectives of delivering outsourced primary school physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2023.2264319

- Aronczyk, M., & Powers, D. (Ed.) (2010). Blowing up the brand: Critical perspectives on promotional culture. Peter Lang.

- Bowles, H., Clift, B. C., & Wiltshire, G. (2022). Joe Wicks, lifestyle capitalism and the social construction of PE (with Joe). Sport, Education and Society, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2117150

- Breidenstein, G., & Rademacher, S. (2017). Individualisierung und Kontrolle. Empirische Studien zum geöffneten Unterricht in der Grundschule [Individualization and control. Empirical studies on open teaching in elementary school]. Springer VS.

- Brennan, S., & Noggle, R. (2007). Taking responsibility for children. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Coulter, M., Britton, Ú, MacNamara, Á, Manninen, M., McGrane, B., & Belton, S. (2023). PE at home: Keeping the ‘E’ in PE while home-schooling during a pandemic. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 28(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1963425

- Cruickshank, V., Pill, S., & Mainsbridge, C. (2022). The curriculum took a back seat to huff and puff: Teaching high school health and physical education during COVID-19. European Physical Education Review, 28(4), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X221086366

- Dietrich, F., Faller, C., & Kuhlmann, N. (2022). Berufskulturelle (Nicht-)Zuständigkeit. Empirische Rekonstruktionen von Selbst- und Fremdpositionierungen zur ,Corona-Krise‘ [Professional cultural (non-)responsibility. Empirical reconstructions of self- and external positionings towards the ‘corona crisis’]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 68(3), 290–306.

- Edwards-Groves, C. (2018). The practice architectures of pedagogy: Conceptualising the convergences between sociality. In O. B. Cavero & N. Llevot-Calvet (Eds.), New pedagogical challenges in the 21st century – contributions of research in education (pp. 119–138). IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.72920

- Eickelmann, B., Bos, W., & Labusch, A. (2019). Die Studie ICILs 2018 im Überblick. Zentrale Ergebnisse und mögliche Entwicklungsperspektiven [The ICILs 2018 study in overview. Key findings and possible development perspectives]. In B. Eickelmann, W. Bos, J. Gerick, F. Goldammer, H. Schaumburg, K. Schwippert, M. Senkbeil, & J. Vahrenhold (Eds.), Computer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im zweiten internationalen Vergleich und Kompetenzen im Bereich Computational Thinking (pp. 7–31). Waxmann. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:18319

- Fitzpatrick, K., & Powell, D. (2019). Movimento (ESEFID/UFRGS), 25. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.96638

- Flory, S. B., & Landi, D. (2020). Equity and diversity in health, physical activity, and education: Connecting the past, mapping the present, and exploring the future. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1741539

- Gard, M. (2014). eHPE: A history of the future. Sport, Education and Society, 19(6), 827–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.938036

- Gellert, U., Merl, T., Rabenstein, K., & Schierz, M. (2023). Editorial: Fachunterricht und subjektivierung. ZISU – Zeitschrift für Interpretative Schul- und Unterrichtsforschung, 12(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.3224/zisu.v12i1.01

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

- Howley, D. (2022). Experiences of teaching and learning in K-12 physical education during COVID-19: an international comparative case study. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(6), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1922658

- Jette, S., Bhagat, K., & Andrews, D. L. (2016). Governing the child-citizen: ‘Let’s Move!’ as national biopedagogy. Sport, Education and Society, 21(8), 1109–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.993961

- Juhila, K., & Raitakari, S. (2016). Responsibilisation in governmentality literature. In K. Juhila, S. Raitakari, & C. Hall (Eds.), Responsibilisation at the margins of welfare services (p. 24). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315681757

- Kuhlmann, N., & Drerup, J. (2023). Pädagogische Verantwortung revisited: Neueinsätze zur Bestimmung einer pädagogischen Leitkategorie [Pedagogical responsibility revisited: New approaches to the definition of a guiding pedagogical category]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 69(1), 1–5.

- Kuhlmann, N., & Moldenhauer, A. (2021). Sprechen über (Nicht-)Verantwortlichkeiten – Relationierungen von Professionalität und organisationaler Praxis [Talking about (non-)responsibilities – relating professionalism and organisational practice]. In S. Bender, F. Dietrich, & M. Silkenbeumer (Eds.), Schule als Fall. Institutionelle und organisationale Ausformungen (pp. 189–204). Springer VS.

- Kuhlmann, N., & Thiersch, S. (2023). Pädagogische Verantwortung im (digitalisierten) Unterricht: Empirische und professionstheoretische Explorationen [Pedagogical responsibility in (digitized) lessons: Empirical und profession-theoretical explorations]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 69(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.3262/ZP2301054

- Lambert, K., Hudson, C., & Luguetti, C. (2023). What would bell hooks think of the remote teaching and learning in Physical Education during the COVID-19 pandemic? A critical review of the literature. Sport, Education and Society, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2023.2187769

- Lambert, K., Luguetti, C., & Lynch, S. (2022). Feminists against fad, fizz ed: A poetic commentary exploring the notion of Joe Wicks as physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(6), 559–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1911982

- López-Fernández, I., Gil-Espinosa, F. J., Burgueño, R., & Calderón, A. (2023). Physical education teachers’ reality and experience from teaching during a pandemic. Sport, Education and Society, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2023.2254795

- Malcolm, D., & Velija, P. (2020). COVID-19, Exercise and bodily self-control. Sociología del Deporte, 1(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.46661/socioldeporte.5011

- Nyberg, G., Backman, E., & Tinning, R. (2022). Moving online in physical education teacher education. Sport, Education and Society, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2142776

- Opper, E., Worth, A., & Woll, A. (2021). Sportunterricht in der Corona-Pandemie. Rahmenbedingungen und Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten [Physical education in the corona pandemic. Conditions and Design Options]. Sportunterricht, 70(10), 446–450. https://doi.org/10.30426/SU-2021-10-3

- Poell, T., Nieborg, D. B., & Duffy, B. E. (Eds.) (2022). Platforms and cultural production. Polity Press.

- Rabenstein, K., & Drope, T. (2022). Praxistheoretische Unterrichtsforschung und Weiterentwicklung ihrer sozialtheoretischen Grundlegung [Theory of practice classroom research and development of its social-theoretical foundation]. In U. Bauer, U. H. Bittlingmayer, & A. Scherr (Eds.), Handbuch Bildungs- und Erziehungssoziologie (pp. 1–21). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30903-9_41

- Ricken, N., Rose, N., Otzen, A. S., & Kuhlmann, N. (Eds.) (2023). Die sprachlichkeit der anerkennung. Subjektivierungstheoretische Perspektiven auf eine Form des Pädagogischen [The discursivity of recognition. Subjectivation-theoretical perspectives on a form of the pedagogical]. Beltz.

- Rode, D., & Zander, B. (2022). Sportunterricht im Internet. Ethnographische Perspektiven auf ein neues Forschungsfeld [Physical Education on the internet. Ethnographic perspectives on a new field of research]. In J. Schwier & M. Seyda (Eds.), Bewegung, spiel und sport im kindesalter. Neue entwicklungen und herausforderungen in der sportpädagogik (pp. 145–156). transcript. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839458464-013

- Rode, D., & Zander, B. (2023). Remote physical education during the coronavirus pandemic. A discourse analysis of how students are positioned on Padlet webpages. Current Issues in Sport Science (CISS), 8(3), 00004. https://doi.org/10.36950/2023.3ciss004

- Roth, A.-C., & Stamm, L. (2023). Physical education in Germany in COVID times – a qualitative study on changes and challenges from the teachers’ perspective. International Journal of Physical Education, 60(1), 15–27.

- Schierz, M. (2009). Das Schulfach ‚Sport‘ und sein Imaginäres. Bewährungsmythen als Wege aus der Anerkennungskrise [The school subject ‘sport’ and its imaginary. Probation myths as ways out of the recognition crisis. Spectrum der Sportwissenschaften, 21(2), 62–77.

- Schierz, M. (2013). Bildungspolitische Reformvorgaben und fachkulturelle Reproduktion - Beobachtungen am Beispiel des Schulfaches Sport [Educational policy reform guidelines and subject-cultural reproduction - observations using the example of sport as a school subject. Spectrum der Sportwissenschaften, 25(1), 64–79.

- Schierz, M., & Serwe-Pandrick, E. (2018). Schulische Teilnahme am Unterricht oder entschulte Teilhabe am Sport? Ein Forschungsbeitrag zur Konstitution und Nichtkonstitution von ,Unterricht‘ im sozialen Geschehen von Sportstunden. [Participation in school lessons or un-schooled participation in sport? A research contribution on the constitution and non-constitution of ‘instruction’ in the social events of sports lessons]. Zeitschrift für Sportpädagogische Forschung, 6(2), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.5771/2196-5218-2018-2-53

- Schiller, D., Rode, D., Zander, B., & Wolff, D. W. (2021). Orientierungen und Praktiken sportunterrichtlicher Differenzkonstruktionen. Perspektiven praxistheoretischer Unterrichtsforschung im formal inklusiven Grundschulsport [Orientations and practices of constructing differences in physical education. Perspectives of practice-theoretical research in formally inclusive primary school physical education]. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung, 14(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42278-020-00098-0

- Sperka, L., & Enright, E. (2019). Network ethnography applied: Understanding the evolving health and physical education knowledge landscape. Sport, Education and Society, 24(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1338564

- Willems, H., & Jurga, M. (1998). Inszenierungsaspekte der Werbung. Empirische Ergebnisse der Erforschung von Glaubwürdigkeitsgenerierungen [Staging aspects of advertising. Empirical results of research on generating credibility]. In M. Jäckel (Ed.), Die umworbene Gesellschaft (pp. 209–229). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-83294-8_10

- Wolff, D. (2016). Soziale Ordnung im Sportunterricht: Eine Praxeographie [Social order in physical education lessons]. transcript.

- Wrana, D. (2006). Das Subjekt schreiben. Reflexive Praktiken und Subjektivierung in der Weiterbildung [Writing the subject. Reflexive practices and subjectivation in adult education – a discourse analysis]. Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.

- Wrana, D. (2015a). Zur Methodik einer Analyse diskursiver Praktiken [On the methodology of an analysis of discursive practices]. In F. Schäfer, A. Daniel, & F. Hillebrandt (Eds.), Methoden einer Soziologie der Praxis (pp. 121–144). transcript.

- Wrana, D. (2015b). Zur Analyse von Positionierungen in diskursiven Praktiken [On the analysis of positionings in discursive practices]. In S. Fegter, F. Kessl, A. Langer, M. Ott, D. Rothe, & D. Wrana (Eds.), Erziehungswissenschaftliche diskursforschung. Interdisziplinäre diskursforschung (pp. 123–141). Springer VS.