ABSTRACT

Debates about the importance of mental health and well-being in the context of education and physical education have burgeoned in recent years. Yet, despite the recognition that good teachers have their students’ mental health and well-being high on their agenda, participation in PE lessons does not provide universally positive experiences to all students. Furthermore, there is very little understanding of how PE teachers promote positive mental health and well-being in their lessons. The present study was designed to understand Maltese PE teachers’ and sports lecturers’ perceptions and practices concerning the role of PE in relation to children’s mental health and well-being. Interviews with nine Maltese PE teachers and three sports lecturers were structured to explore how PE teachers defined mental health and well-being, their perceptions concerning the role of PE for mental health and well-being, and what they did to promote mental health and well-being in their lessons. The different definitions these teachers provided highlighted the interconnection between mental health and well-being. In line with scholarly work and curriculum debates, these teachers believed that due to the content, nature and context of the lessons, PE can play an important role in promoting students’ mental health and well-being. To fulfil this, teachers advocated the creation of a stimulating, inclusive and safe environment through the implementation of different practices which resonated with some of the core features of inclusive and student-voice pedagogies. They also elicited external challenges, a degree of uncertainty, and a lack of clarity as important factors hindering the implementation of such practices. The paper suggests that targeted professional development must be available for all stakeholders within PE so that a clear identification about its role in addressing the mental health and well-being of students is instilled. Further research is needed to establish what type of training is the most effective to address the different perceptions and to offer the necessary skills, knowledge and resources required.

Background and study purpose

Debates about the importance of mental health and well-being (hereafter abbreviated to MHW) have burgeoned in recent years. In an unpredictable and ever-changing world, supporting adolescents becoming social agents and well-rounded, active and engaged citizens is more important than ever (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2018). The curriculum subject of Physical Education (PE) is increasingly implicated in debates about MHW. This is not surprising given growing confidence in the links between physical activity and mental health (Rodriguez-Ayllon et al., Citation2019), and established rhetoric – and some research – on the wider contribution of the subject to various learning outcomes in the cognitive, social and affective domains (Harris, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2019). In recent years, children’s physical and mental health have been located at the forefront of curriculum debates. Yet, it is also acknowledged that for these important goals to be achieved, a ‘paradigmatic shift’ in teachers’ thinking and practices is required, moving away from narrowly defined PE content and pedagogies (OECD, Citation2019). Given the variety in the ways PE is enacted in different national and local contexts and evidence that participation in PE lessons does not provide universally positive experiences to all students (García-Carrión et al., Citation2019), understanding PE teachers’ current thinking and practices is important.

Research on what teachers believe and do to support their students’ MHW is at an embryonic stage of development. Unsurprisingly, the existing small body of research suggests that whilst teachers are willing to teach in ways that positively affect the MHW of their students (Graham et al., Citation2011; Reinke et al., Citation2011), they also appear somewhat apprehensive of this requirement or expectation, claiming that there is a significant lack of targeted professional development to support them (Maclean & Law, Citation2022). Within the PE literature, recent publications place emphasis on the potential of PE to improve students’ motivation and feelings of sadness (Cecchini et al., Citation2020), and to decrease exam-related stress (Cale et al., Citation2020). Yet, there is also an acknowledgement that not all students accrue the full benefits of PE (Hortigüela-Alcalá et al., Citation2021). With PE causing stress to some students, Åsebø and Løvoll (Citation2023) suggested that teaching coping strategies could provide a significant new direction. Yet, despite an increasing body of research on social and emotional learning in PE (Barker et al., Citation2020; Dyson et al., Citation2021; Richards et al., Citation2019), and a small number of studies on PE for mental health (Rocliffe et al., Citation2023), there is little understanding of the kind of PE practices teachers adopt to yield positive outcomes on children’s MHW.

The present study was designed to address this gap by exploring Maltese PE teachers’ (including secondary school teachers and college lecturers) perceptions and practices concerning the role of PE in relation to children’s MHW. Two research questions were set:

How do Maltese PE teachers define and understand the notions of MHW?

In what ways do these PE teachers support students’ MHW in their lessons?

Teaching quality is perceived as one of the most significant school-based factors influencing student learning (Hattie, Citation2009). Thus, what, how, why and the extent to which PE teachers afford positive learning experiences to all students can have profound implications in not only supporting lifelong and purposeful engagement in physical activity (UNESCO, Citation2014) but also making a positive contribution to children’s MHW. Eliciting the views of teachers can offer valuable insights about the realities of current and possible pedagogies for MHW, informing policy and practice on how best to afford teachers the knowledge, skills and resources required to have a positive and sustained contribution to this significant contemporary matter.

In Western thought and literature, the concepts of mental health and well-being are open to various interpretations, often used interchangeably, but also not always clearly defined. Debates on the appropriate use of the term mental health in schools can be traced back in the 1960s, when mental illness was separated from that of mental health to reduce stigma (Rowling et al., Citation2002). The World Health Organisation (WHO, Citation2022) defines mental health as the absence of mental illness and mental disorders, and as a state of well-being in which an individual can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and be a contributor to the community while realising his or her own abilities. Yet, mental health is not a continuum that is simply and primarily something that signals an absence of mental illness.

Often described as a ‘multidimensional concept’ (Granlund et al., Citation2021, p. 7), the research team’s understanding of MHW was in line with Keyes’ (Citation2002) definition of mental health, as being connected – and thus understood in relation – to two traditions of well-being: the hedonic (i.e. the feelings of happiness, satisfaction and interest in life) and the eudaimonic (i.e. the regulation of negative emotions leading to life satisfaction and vitality) well-being (Kryza-Lacombe et al., Citation2019; Ortner et al., Citation2018; Ryan & Deci, Citation2001). Crucial, Keyes’s (Citation2002) assertion that it is erroneous to understand mental health as involving a definite categorisation of individuals who are either flourishing at one end of a continuum and others who are languishing at another is significant. Keyes (Citation2002) argued that distinguishing mental health (labelled as flourishing) from mental illness is important, with studies confirming that individuals with bouts of mental illness during certain episodes in life, does not mean that they might not flourish during others (Agenor et al., Citation2017; Fredrickson & Losada, Citation2005). This brings us to another important observation, which is particularly relevant in the context of the present study: namely, that the state of one’s mental health is not solely dependent on the individual but also on the environment, other people and one’s relationships, as well as the wider context and available opportunities (Keyes, Citation2002).

Educational policy documents often cite WHO’s definition of mental health and refer to mental health and well-being interchangeably and without offering an elaborate interpretation of their meaning. Achieving clarity on the meaning of this study’s central concepts was a necessity since this study was an introduction to a subsequent study focusing on Physical Education (PE) for MHW. Instead of providing our own interpretation of MHW, and as explained in the methods section, we asked the study participants to share their own personal constructions / understandings of the two concepts separately (i.e. Mental Health and Well-being), and to reflect on their practices for achieving both MHW in the context of their personal understandings.

The study context

Malta is the smallest state in the European Union and is an island found in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, with a population of around 521,000 (National Statistics Office, Citation2023). In Malta, compulsory schooling is between the ages of 5 and 15, up till the end of Year 11 at secondary school. Education in Malta is provided by the state, by the Church and a few private, Independent schools, and includes both formative and summative assessment procedures, with students sitting end-of-year exams between Year 5 in primary school and Year 11. At the end of compulsory schooling, at the age of 16, students can opt to sit for Secondary Education Certificate (SEC) exams, which are a prerequisite to proceed to post-secondary education. Around 80% of all school leavers at the age of 16 opt to further their education at post-secondary institutions after completing compulsory education (National Statistics Office, Citation2023), putting Maltese students at sixth place amongst all EU countries. Educational policies in Malta reflect the EU’s vision and policies, especially regarding vocational education and training, higher education, employability and transference of skill (European Commission, Citation2023).

Regarding mental health, in 2021, the Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health and the Malta Council for the Voluntary Sector published data confirming that 40% of children and adolescents in Malta between the age of 5 and 16 are at risk of a mental disorder (Balzan, Citation2021). In this context, it is not surprising that MH is becoming an urgent matter. The recently developed Mental Health Strategy considers schools and workplaces as priority hubs for mental illness prevention, with schools expected to support students’ mental well-being (Ministry of Health, Citation2019). Preventative actions include training teachers to use appropriate language when discussing mental health with children and adolescents; employing qualified specialists, such as inclusion coordinators and counsellors, to offer one-to-one sessions with referred students; promoting physical activity to decrease sedentariness in adolescence; and incorporating MHW-related content in the compulsory Personal, Social and Career Development (PSCD) syllabus.

Within the 2012 National Curriculum Framework, which is the document providing the overall vision about the purpose of education in Malta and the aims of each subject area, there is no explicit mention of MHW. Yet, significant references to matters related to MHW are evident. One such example is the importance placed on creating the right inclusive environment to address the needs of all Maltese students (Ministry of Education and Employment, Citation2012). To achieve the vision of the curriculum, each subject area has an associated Learning Outcomes Framework, which is a tool to support teachers to effectively deliver teaching and learning experiences in schools. The new Learning Outcomes Framework (DQSE, Citation2018) was designed to give teachers more autonomy and a degree of flexibility to make decisions about curriculum content that addresses the needs of students. The implementation of the subject-specific Learning Outcomes Framework for PE commenced in 2016 within the primary year groups and then was gradually implemented within the middle year groups (year 7 and year 8) (2017) and the senior school groups (year 9 to year 11) (2018).

The learning outcomes for PE have three main strands: (1) personal/physical learning (e.g. LOFI9.8 I can measure my heart rate and can determine my aerobic and training zone); (2) cognitive learning (e.g. LOIG10.7 I can help my team-mates to exploit the defensive disorganisation of the opponents, by performing fast offensive transitions); and (3) social learning (e.g. LOHD10.11 I can lead my team-mates within the group/team to achieve a good standard of performance). The content is presented in a progressive way so that students build upon previous learning experiences. For example, LO7.1 in Athletics states that ‘I can start sprinting from a standing and a 3-point start’, then LO8.1 expects students to ‘set and use the blocks to start sprinting’, whilst in LO9.1, ‘I can get off the starting blocks forcefully at an angle and raise the body gradually while accelerating’ (DQSE, Citation2018, p. 30). As previously noted, currently, there are no learning outcomes specific for MHW and no direct reference to related pedagogical practices. Yet, student well-being is a priority in the education system and in the Maltese society more broadly. In this study, teachers were encouraged to reflect on their perceptions and practices about PE for MHW in the context of this curriculum framework.

Methods

Research paradigm, design, and sampling

The study was grounded in the social constructivist paradigm, as its purpose was aligned with the key philosophical position that multiple experiences, perceptions and realities exist and that interactions with participants are necessary for the researcher to understand and interpret participants’ unique perceptions (Guba & Lincoln, Citation2005). A case study research design was deemed the most appropriate to explore the phenomenon of mental health and well-being in relation to PE by promoting reflections on the kind of perceptions and practices practitioners have and adopt (Thomas, Citation2017).

Teacher recruitment was purposive and based on convenience. The intention was to recruit teachers working in different schools within the Maltese educational system – including State, Church, Independent and Post-Secondary institutions responsible for Initial Teacher Training (ITT) degree programmes for prospective PE teachers; as well as teachers identifying as having different genders and years of experience (from novice to experienced teachers). An experienced Maltese teacher herself, the first author utilised her local knowledge to approach teachers with these professional characteristics, and who were perceived to be highly competent and well-informed practitioners (Bernard, Citation2002) as well as willing, available, and ready to embark on this reflective journey (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). In total, twelve PE teachers (eight males and four females) were recruited. Three out of the 12 participants were sports lecturers in a post-secondary institution which offers degree programmes for prospective PE teachers. Details about the participants are listed in . Ethical approval to carry out the research was received, and study information letters were distributed to each participant. What the study involved, and withdrawal information were explained to the participants before asking for consent.

Table 1. Information about participants.

Interviews

Interviewing is a widely used method in educational research, enabling gathering data about thoughts, feelings, and values (Branthwaite & Patterson, Citation2011). It was thus an appropriate method to explore teachers’ perceptions and practices. A semi-structured approach was adopted to allow for key topics to be discussed but also flexibility to allow participants to focus on issues of importance to them (Thomas, Citation2017). The interview included five sections starting with questions aimed at exploring how PE teachers define MHW, followed by questions about school strategies/approaches to promote MHW, the role of PE in this context, and their specific practices to support MHW but also practices that they perceived as detrimental. Due to Covid-19 restrictions, interviews were conducted online using different platforms chosen by the participants (primarily Zoom and Teams). The interviews were carried out between May and September 2021, at a date, time and location convenient to the teachers and lasted an average of 90 minutes each.

The purposive selection of participants, based on their reputation of implementing best practice within their different contexts led to learning from the ‘best’, but further research is needed to get a more holistic, all-rounded understanding of PE teachers’ diverse and unique perceptions and practices. The biggest issue experienced by the researcher during the interviews was what Oliffe et al. (Citation2021) described as the absence of the presence. Even though all participants kept their cameras switched on throughout the whole interview, a lack of eye contact was noticed, and it was hard for the researcher to observe any body language that could provide deep understanding (Oliffe et al., Citation2021). Covid restrictions also made it impossible to collect first-hand data about their practices, for example through lesson observations. Future on-site research is needed to delineate how possible it is to fulfil MHW-related outcomes in the limited time PE has in the curriculum.

Data analysis

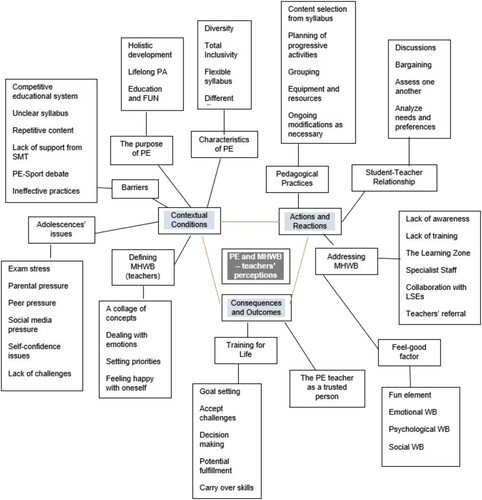

Qualitative data was analysed using grounded theory, involving open coding, axial coding, and ultimately selective coding to condense and draw themes from the data (Charmaz, Citation2006). Specifically, once interviews were transcribed, the researcher engaged in initial coding – an incident-by-incident analysis seeking to describe phenomena and attach names or labels to data extracts. Initial coding was also supported by memo writing (i.e. initial interpretations of evidence) and constant comparisons between codes to decide which belonged together (Charmaz, Citation2006). Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2015) analytical tool was used during the axial coding process (creation of categories), with the researcher grouping codes linked to contextual conditions (i.e. the participants’ current understandings and knowledge about MHW), to actions and interactions (i.e. the practices which participants implemented and which they perceived to address the students’ MHW) and the consequences and outcomes (i.e. the possible outcomes of these practices). shows the codes which emerged from this analysis.

Figure 1. Codes derived from the analysis of the twelve interviews following Corbin and Strauss’ consequential matrix (Citation2015).

Following the completion of this interactive process, three themes relevant to the papers’ research questions were created: Defining MHW, the role of PE as a tool in promoting MHW and current PE pedagogies for MHW. Apart from their current practices, participants brought up their concerns and gave relevant and practical suggestions towards a reimaged subject to address MHW.

Trustworthiness and reflexivity

The trustworthiness of the interview data was established by participant reflections (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018) that were conducted both during and following the end of the interviews. Whenever possible during the interviews, participants were probed to clarify or elaborate on issues discussed, to collect rich, detailed, and accurate data. At the end of the interview, a summary of key points discussed was created by the researcher and discussed with all participants to ensure that the researcher’s interpretations reflected their perspectives, and to generate additional data which might have been omitted or not extensively discussed previously.

The qualitative design of this research means that the findings cannot be generalised in the traditional sense. It is acknowledged that the ways these participants interpreted MHW are likely to differ from others in different contexts. However, it is also important to acknowledge that, as Stake (Citation2005) explained, one of the greatest strengths of interviews is that they allow readers to experience the particular, the ordinary, the exceptional or the unique experiences and views of others. The results reported in this paper, presented in detailed, rich descriptions of participants’ interpretations and practices, have the potential to be generalised in two ways: (i) by allowing the readers (who might be school leaders, teachers, tutors, or other CPD stakeholders) to recognise the similarities and differences between the reported results and their own lives and professional practices, and as a result develop their knowledge and understanding (naturalistic generalisation); and (ii) by encouraging readers to reflect upon the main findings and to consider adopting ideas or practices that are relevant to their context and priorities (transferability) (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018).

When conducting a qualitative study, the researcher’s positionality and the extent of the relationship with the participants must be made fully transparent in relation to the study’s rigour, quality and credibility (Berger, Citation2015). Given the fact that the primary researcher is a former PE teacher in Malta, who has recently moved to teaching diploma and degree students specialising in Sport, Exercise and Health at the tertiary level, the researcher can still be considered an ‘insider’ (Dodgson, Citation2019, p. 220). It was imperative to engage in reflexivity in all cycles of the project, to understand the participants’ beliefs, and their influence on the research process (Jamieson et al., Citation2022). A profile of each participant and of the context in which they teach was compiled at the beginning of each interview and this helped the researcher get an initial snapshot of the current context adopting a learning outcomes framework. This pre-interview research transformed the interviews into discussions, with both the researcher and participants intervening with own opinions. The researcher was careful to do this subtly and without influencing and directing the answers of the participants towards certain responses.

Results

Theme 1: the meaning of MHW

Participants found the quest to define mental health and well-being (MHW) as separate concepts a challenge. Their definitions had significant overlaps with similar responses given for both mental health and well-being. Specifically, most definitions of mental health were positioned more towards the emotional domain. Being in control of one’s actions, thoughts, and decisions (n = 6) and feeling happy (n = 4) were considered significant indicators of good mental health. As Therese explained, ‘MH is all about setting priorities and do what is necessary to feel happy’, whilst Peter focused on the importance of ‘feeling good about yourself’, by for example ‘training our minds to control the daily challenges, to face problems and to empathise with others’. Some of the participants, instead of providing a definition, mentioned factors which they believed mental health depended on. Elton referred to the continuous bombardment in social media which affects one’s self-respect. The various relationships we [people, including children] engage in, either out of choice (e.g. partners and friends) or necessity (e.g. classmates), were also identified by most participants (n = 7) as affecting one’s mental health.

When asked to define well-being, seven participants linked well-being to a range of domains – the physical, the social, the cognitive and the emotional and of significance was the idea of being a complete individual. George defined well-being as ‘the whole individual, totally complete’ while Lisa explained how well-being is seen by her as a wide concept affecting all aspects of health. After previously giving a definition for mental health, five participants found it hard and confusing to define well-being as a separate concept and ended up providing definitions similar to those they gave for mental health. The ‘feel-good’ factor and ‘happiness’ both leading to a ‘sense of fulfilment’ were amongst the common denominators of both definitions (n = 8). For example, Lisa said that the same factors she mentioned when defining mental health, ‘feel-good factor, enjoyment’, fit the same definition of well-being. Anton linked well-being to happiness in the same way that he defined mental health as a state in which the individual avoids what is worrying and seeks what leads to happiness.

Theme 2: the role of PE as a tool in promoting mental health and well-being

When participants were asked about the purpose of PE, six participants made explicit connections between PE and the promotion of healthy active lifestyles as an avenue to achieve broader health benefits. Positive experiences of physical activity (PA) were important for them. PE was seen as an ‘investment’ (Peter), ‘equipping students with the necessary skills’ (Janice) to become aware of the importance of PA and to reap its lifelong, holistic benefits. Four participants were, however, concerned that the purpose of PE is somewhat ‘muddled’ (Javier). Lisa argued that this is the result of the wrong perception, often advocated by policy makers, that PE and organised competitive sport in Malta cannot be separated. Building upon this argument, Javier added that this sentiment results in inconsistencies at different levels, with PE provision taking a more sport-oriented stance due to the pressure from authorities towards success in organised sports. Through her experiences and observations of prospective teachers, Lisa was concerned that, at times, ‘we forget that PE is a curriculum subject, is part of the education of young people’.

When asked explicitly to articulate their views concerning the role of PE for MHW, some participants (n = 4) felt that the flexibility permitted in setting local PE learning outcomes enables teachers to ‘be flexible and creative’ (Keith) and to focus on different aspects of children’s development. This curriculum flexibility and especially the affordance given to students to achieve those outcomes ‘at their own pace, either individually or with others’ (Keith), was seen as an important aspect in relation to supporting MHW. Keith explained how allowing the students to choose their areas of interest and to engage in tasks gradually, according to their abilities, ‘helps them achieve more, believe in themselves and be confident in face of challenges’.

Some teachers (Peter, Elton, Therese and Anton) drew attention to the ‘scaffolded’ and ‘progressive way’ outcomes are presented, enabling teachers to teach the content in an appropriate way for learner diversity; in other words, facilitating adaptation to different abilities. This ‘scaffolding’ experience specifically helps to give the students ‘the right challenge to explore ways to fulfil their potential, and to accept that at times failure also occurs’ (Lisa). Furthermore, there was consensus that the more relaxed context in which learning takes place in PE puts the subject in a unique position to support children’s MHW. Learning outside of a traditional classroom ‘can inspire a sense of freedom which for most students results in a fun experience’ (George), makes students ‘move, think and act at the same time’ (Elton) while teachers can ‘easily address students’ needs and desires individually without the need of addressing the whole class’ (Keith).

For PE to have a meaningful contribution to children’s MHW, some of the participants argued that several changes – at all levels, from policy to practice – must occur. At policy level, George argued that the status of PE is low, with the subject being considered inferior compared to other curriculum areas. The large number of students in a class (Javier and Elton), the lack of facilities in certain schools (Lisa, Anton and George) and the little time allocated to PE in the weekly timetable (James, Therese and Janice) can prevent the enactment of practices that promote MHW. At the school level, Tiziana suggested that PE teachers must attract the attention of the Senior Management Team within schools to get the support and resources required to make an impact. Keith focused on significant bureaucratic and knowledge-sharing barriers. For example, information about students’ particular needs is not explained to teachers or teachers are not aware about certain background issues which might affect a student’s performance in class. As he argued: ‘Red tape must be removed within schools to avoid misunderstandings in approaching students and to give all students the support they need’.

According to Keith, Peter, Anton and Lisa, there are certain attitudes and behaviours which teachers should adopt in their approach to promote positive MHW. Specifically, Keith suggested that teachers must themselves believe more in the potential of PE and in their own potential, while Peter added that teachers should ‘think outside the written learning outcomes and take the initiative to create outcomes based on the students’ needs’. Anton also talked about the need for teachers to be ‘creative in presenting enjoyable and effective content’ which appeals to adolescents. To achieve this, Lisa pointed out that teachers need ‘space to implement what they deem fit for their students, instead of having a one size fits all approach’. A significant matter that inhibited appropriate implementation of these wider outcomes, including MHW outcomes, according to six participants and like what was argued previously about PE more widely, was the heavy emphasis placed on the performance element of PE, as well as the predominant assessment of physical competences.

Theme 3: current PE pedagogies for mental health and well-being

Participants were asked to reflect on the pedagogies they implemented and which they believed contributed to their students’ MHW. The participants highlighted the challenges they faced when implementing such pedagogies and gave practical suggestions on how to overcome them. George, Keith and James talked about the importance of getting to know the individual students’ needs, desires and abilities. Knowing the child, according to George, informs content adaptations, ‘how I set-up the groups, the type of language I choose to keep the students active, motivated and above all have fun’. According to seven of the participants, the way students are grouped and the level and type of interaction with each other within these same groups, can affect the students’ MHW. There was no consensus whether it was more beneficial for students to be divided according to ability (n = 3) ‘to avoid frustration’ (Peter) or else mixed (n = 4) ‘to learn to respect the different abilities’ (Keith). From Anton’s perspective, mixing abilities meant ‘the real inclusion where everyone learns to empathise with others’.

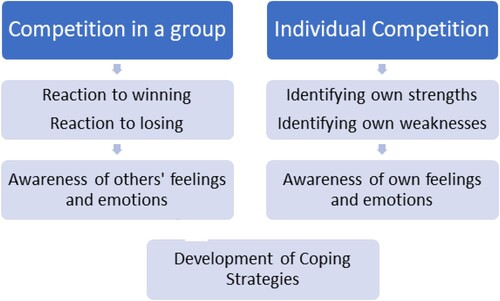

The way students are grouped is relevant to another debated matter that five participants believed was key for MHW: the inclusion of competition. The participants explained that they included competitive tasks in order to make students more aware of not only their abilities/performance but also their feelings. This was possible both in tasks where they competed together as a team, presenting opportunities for students to ‘become aware of’ how they and ‘their peers express different emotions’ (Elton); and where they competed against their own selves to ‘make them further aware of their own personalities, how they tackle aggressiveness, how they react under pressure’ (Thomas). Most participants acknowledged that competition was frequently embedded in team games. Some believed that the overdominance of team games was problematic especially for students with specific personalities, as team games might fail to provide the right content and context for promotion of MHW. George, for example, insisted that team games could be experienced by some students as ‘a threat’; particularly ‘students with introvert traits’ or ‘low ability’. On the contrary, Anton believed that engagement in team games, involving interactions, tension and competition, matches ‘real-life situations’ and is thus both challenging and exciting. From this perspective, competition and team games can be used appropriately to promote students’ MHW.

Despite this degree of disagreement about the place of team games and competition when it comes to MHW, there was agreement about the value of even negative or challenging situations, as these can provide opportunities for growth (Peter, Therese, Anton, George, Elton and Tiziana). These participants believed that overcoming movement challenges offers students the opportunity to develop their autonomy, improve their self-esteem, and to experience a reality in which success is not guaranteed. For Peter, it was important for students to become aware of and accept their different abilities (and their own strengths) as they encounter ‘different kind of challenges’. These skills could be further enhanced through ‘constant motivation’ (Therese), ‘support to overcome fear’ (Elton) and ‘constructive feedback’ (Tiziana and Anton) given by the teacher. This support was likely to improve students’ self-esteem, to encourage them to ‘reflect individually or in a group’ (Tiziana, Lisa and Keith), to ‘take decisions and evaluate’ (Peter) and eventually to ‘come up with goals themselves to improve’ (George and Anton). Lisa argued that teachers need to find the right ‘teachable moments to allow students to be more autonomous in reflecting about the good feeling of success and the disappointment of failure through reflection’.

These participants believed that implementing these practices regularly and constantly during the lessons helped towards the development of the students’ MHW. Being more aware of their strengths and capabilities enabled students to feel better and ‘positive about themselves’ (Elton). This further led the students to ‘develop strategies to cope in front of challenges presented’ (Lisa). Lisa added that these strategies could be useful for the students when faced with challenges outside the school context. Tiziana and Lisa mentioned how they [the teachers] empowered their students by engaging in PE-related discussions with them. During these discussions, they could identify the students’ preferences and encouraged them to reflect on both the content and the way it was presented.

Discussion and conclusion

The present study was designed to understand Maltese PE teachers and sports lecturers’ perceptions and practices concerning the role of PE in relation to children’s MHW. Findings drew attention to three important considerations: the meaning of MHW which reflects a salutogenic understanding of health; the PE pedagogical practices for MHW; and finally the challenges faced by the teachers in the implementation of such practices. Together, these themes reflect the participants’ belief in the potential of PE to promote positive MHW.

The meaning of MHW: reflecting a salutogenic understanding of health

The first finding relates to teachers’ understandings of MHW. When encouraged to discuss their subjective, personal interpretations of MHW, most participants acknowledged the interconnections between the notions of mental health and well-being, but also reported difficulty in identifying their differences. Yet, it was promising to observe that their responses reflected elements of a salutogenic understanding of health with a greater focus on a wider number of factors that contribute towards the promotion of health (Brolin et al., Citation2018). Signalling a significant departure away from the biomedical understanding of health (which tends to concentrate on identifying and treating diseases or pathological conditions), a salutogenic perspective is centred on the idea that health is not simply the absence of diseases (Keyes, Citation2015; Keyes et al., Citation2017). Being healthy is rather understood as a reflection of a positive and dynamic state of well-being (Schramme, Citation2023; White, Citation2008). The implications of a salutogenic understanding of health for PE provision have been discussed in previous publications, which are worth revisiting here:

In the PE environment, a salutogenic understanding of health directs attention to the qualities, abilities, and knowledge that students develop as tools for personal growth and empowerment so that individuals live a good life. (Quennerstedt, Citation2008)

PE pedagogies for positive MHW

Most participants were committed to placing their students’ MHW at the forefront of their practices and believed that PE has the potential to have a unique and positive impact on children’s MHW, because of the informal context it takes place, the flexibility of the curriculum, and the nature of learning. For example, the flexible PE curriculum learning outcomes allow teachers to choose the content and level of challenge in response to their learners’ needs, which is one of the most significant aspects of effective teaching and learning (Coe et al., Citation2020). For these teachers, this tailored provision can also lead to positive feelings and MHW as students engage positively with learning experiences. Positive MHW was also believed to be experienced during PE when students are owners of their own learning, identify their strengths and weaknesses, and come up with solutions to improve their performances. PE can thus provide opportunities for students to learn how to respond to different situations and challenges, and to develop coping skills (Åsebø & Løvoll, Citation2023; Lang et al., Citation2016), which can be significant in other facets of their lives.

Participants also advocated a stimulating, inclusive and safe environment as a fundamental prerequisite for positive MHW. In fact, many of the participants’ reflections resonated with some of the core features of inclusive pedagogy. Understanding their learners’ needs and starting points, offering choices and adaptations, and setting appropriate challenges with scaffolding, all speak about the type of inclusive, supportive learning environment that the participants believed can develop students’ confidence, co-dependence and independence (Baroutsis et al., Citation2016; Rautio & Jokinen, Citation2016). Participants also talked about establishing the right social environment as a key prerequisite for positive MHW. Feeling connected with and accepted by others is a basic psychological need; and a sense of belonging is crucial to life satisfaction, happiness, mental and physical health (Chen et al., Citation2015). In this context, the importance for teachers to foster positive peer interactions and relationships is a significant factor not only for academic achievement (Brown, Citation2019) but also for student satisfaction and enjoyment of school learning (Fabes et al., Citation2019). So, theory, research and practice on inclusive pedagogy can provide a powerful framework, and starting point, for delineating the core components of PE for MHW.

Whilst there was consensus about the importance of inclusion and positive peer interactions for MHW, there was a degree of disagreement about the ideal grouping strategies that promote positive MHW. Wilkinson et al. (Citation2016) have described the practice of grouping as a transient and complex one; and the participants in this study underlined the importance of carefully thinking about the most appropriate grouping approach, by taking into consideration existing power dynamics, students’ needs in the context of positive MHW, as well as the nature of the task. Another PE practice debated was if, how and when to include competition during PE, and the potential effect of competitive activities on students’ MHW. Scholarly work suggests that if implemented appropriately, competition can attribute to the development and strengthening of attitudes and behaviours that are linked to MHW (Aggerholm et al., Citation2018; Smee et al., Citation2021). The participants mentioned how the implementation of both group competition and self-competition during lessons can have a positive impact on students’ MHW. The framework presented in , developed based on the responses provided by the participants in the present study, summarises key principles for PE teachers to consider when they enact competition for positive MHW.

For these participants, when students compete together as a group, they not only become aware of how they feel and react in both ‘successes and ‘failure’, but they also have first-hand experience of how other people react to success and / or to defeat. If these matters (and feelings) are acknowledged and discussed, according to some participants, it can support students to develop respect for others’ abilities, reactions and personalities. The participants also spoke about self-competition in the form of engaging in individual challenges which help students to understand their own abilities and become aware of their own emotions and feelings in regards of their performance. By engaging in such opportunities offered during the PE lesson, and in line with the relevant literature, students can develop coping skills and strategies (Jakobsson, Citation2014; Shields & Bredemeier, Citation2011). This is where the subject can add significant value in relation to the promotion of positive MHW. Therefore, the place and enactment of competition needs to be carefully considered and further researched, in the context of the heightened importance of PE for positive MHW for all.

PE for MHW: challenges

Although the value of PE for positive MHW can be significant, these participants were also aware of the key barriers in achieving this in practice. The main concerns revolved around logistical problems they face daily (e.g. lack of space in case of inclement weather, lesson disruption due to other activities in school), and constraints posed by limited resources (e.g. including lack of equipment, limited professional development (Armour & Yelling, Citation2007), restricted timetabled PE time). Lack of professional development, specifically, means leaving teachers operating in isolation and without official, evidence-informed dialogue on the purpose of PE. This, thus, enables the perpetuation of conflicting messages and practices about the place and role of PE.

Historically, the purpose and enactment of PE have been shaped in significant ways by strong and diverse discourses (Kirk, Citation2013). Internationally, the health discourse is a prominent one, but debates have tended to place more emphasis on the role of PE in addressing the ‘issues’ of childhood obesity and physical inactivity (Burson et al., Citation2021; Cawley et al., Citation2013) as opposed to mental health (a trend that appears to be shifting in recent years). PE as a tool / strategy / subject that could enhance positive MHW is, however, a distinctive matter and these participants did not feel there is sufficient clarity in what PE teachers are trying to achieve as far as MHW is concerned. The participants also talked about the dominance of a sports and performance discourse, promoting competition more or rather than participation (Herold, Citation2020; Penney, Citation2000). For decades, this discourse – these teachers argued – has shaped in significant ways the purpose, importance and enactment of PE in Malta. Thus, whilst these teachers appeared to have clarity about the meaning of MHW, a degree of confusion and concern about the place of MHW in the context of these competing discourses was expressed. Exploring the interplay and influence of these diverse and prevailing discourses is therefore a significant direction in better understanding how to effectively incorporate and promote the language and pedagogies for positive MHW.

Final thought

This study is considered timely in light of the heightened importance currently being placed on MHW within different contexts, including education. The implications from this study are clear: with significant ambiguity about what teachers should know about MHW and variability in the degree of professional responsibility for MHW, there is still a vacuum about what the future of PE and professional development should consist of to understand how teachers can meet the complex and diverse needs of children and young people. There is also a clear need for further research on the key pedagogies which can lead to positive MHW. Practices such as inclusion, peer interactions and competition, and others which can lead to the development of coping strategies, need to be better understood to inform professional development activities for teachers. We acknowledge that evidence reported in this paper relied on teachers’ perceptions alone. Students’ experiences and viewpoints about PE and MHW were missing. Yet, within the new sociology of childhood (Papadopoulou & Sidorenko, Citation2022), it is imperative to place increasing value on student voice, which can inform and shape future policies and practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agenor, C., Conner, N., & Aroian, K. (2017). Flourishing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 915–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1355945

- Aggerholm, K., Standal, ØF, & Hordvik, M. M. (2018). Competition in physical education: Avoid, ask, adapt or accept? Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich), 70(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1415151

- Armour, K. M., & Yelling, M. (2007). Effective professional development for physical education teachers: The role of informal, collaborative learning. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 26(2), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.26.2.177

- Åsebø, E. K. S., & Løvoll, H. S. (2023). Exploring coping strategies in physical education. A qualitative case study. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 28(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1976743

- Balzan, J. (2021, September 13). Over 35,000 children at risk of mental disorder, study finds. Newsbook.

- Barker, D., Nyberg, G., & Larsson, H. (2020). Joy, fear and resignation: Investigating emotions in physical education using a symbolic interactionist approach. Sport, Education and Society, 25(8), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1672148

- Baroutsis, A., McGregor, G., & Mills, M. (2016). Pedagogic voice: Student voice in teaching and engagement pedagogies. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 24(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1087044

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Bernard, H. R. (2002). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Alta Mira Press.

- Branthwaite, A., & Patterson, S. (2011). The power of qualitative research in the era of social media. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 14(4), 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522751111163245

- Brolin, M., Quennerstedt, M., Maivorsdotter, N., & Casey, A. (2018). A salutogenic strengths-based approach in practice – An illustration from a school in Sweden. Curriculum studies in health and physical education, 9(3), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2018.1493935

- Brown, M. (2019). The push and pull of social gravity: How peer relationships form around an undergraduate science lecture. The Review of Higher Education, 43(2), 603–632. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0112

- Burson, S. L., Mulhearn, S. C., Castelli, D. M., & van der Mars, H. (2021). Essential components of physical education: Policy and environment. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 92(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2021.1884178

- Cale, L., Harris, J., & Hooper, O. (2020). Debating health knowledge and health pedagogies in physical education. In S. Capel & R. Blair (Eds.), Debates in physical education (2nd ed., pp. 256–277). Routledge.

- Cawley, J., Frisvold, D., & Meyerhoefer, C. (2013). The impact of physical education on obesity among elementary school children. Journal of Health Economics, 32(4), 743–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.04.006

- Cecchini, J., Fernandez-Rio, J., Mendez-Gimenez, A., & Sanchez-Martinez, B. (2020). Connections among physical activity, motivation and depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. European Physical Education Review, 26(3), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20902176

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

- Coe, R., Rauch, C. J., Kime, S., & Singleton, D. (2020). Great teaching toolkit: Evidence review.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage.

- Directorate for Quality and Standards Education (DQSE). (2018). Learning outcomes framework. Ministry for Education and Employment.

- Dodgson, J. E. (2019). Reflexivity in qualitative research. Journal of Human Lactation, 35(2), 220–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419830990

- Dyson, B., Howley, D., & Wright, P. M. (2021). A scoping review critically examining research connecting social and emotional learning with three model-based practices in physical education: Have we been doing this all along? European Physical Education Review, 27(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20923710

- European Commission. (2023). Malta ongoing reforms and policy developments. europa.eu.

- Fabes, R. A., Martin, C. L., & Hanish, L. D. (2019). Gender integration and the promotion of inclusive classroom climates. Educational Psychologist, 54(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1631826

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American psychologist, 60(7), 678. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678

- García-Carrión, R., Villarejo-Carballido, B., & Villardón-Gallego, L. (2019). Children and adolescents mental health: A systematic review of interaction-based interventions in schools and communities. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 918. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00918

- Graham, A., Phelps, R., Maddison, C., & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teachers and Teaching, 17(4), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.580525

- Granlund, M., Imms, C., King, G., Andersson, A. K., Augustine, L., Brooks, R., Danielsson, H., Gothilander, J., Ivarsson, M., Lundqvist, L. O., & Lygnegård, F. (2021). Definitions and operationalization of mental health problems, wellbeing and participation constructs in children with NDD: Distinctions and clarifications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041656

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 191–215). Sage.

- Harris, J. P. (2018). The case for physical education becoming a core subject in the national curriculum. Physical Education Matters, 13(2), 9–12.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Herold, F. (2020). ‘There is new wording, but there is no real change in what we deliver’: Implementing the new national curriculum for physical education in England. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 920–937. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19892649

- Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Barba-Martín, R. A., González-Calvo, G., & Hernando-Garijo, A. (2021). ‘I hate physical education’; An analysis of girls’ experiences throughout their school life. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(6), 648–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1937077

- Jakobsson, B. (2014). What makes teenagers continue? A salutogenic approach to understanding youth participation in Swedish club sports. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 19(3), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.754003

- Jamieson, M. K., Govaart, G., & Pownal, M. (2022). Reflexivity in quantitative research: A rationale and beginner’s guide. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xvrhm.

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2015). Human flourishing and salutogenetics. In Genetics of psychological well-being: The role of heritability and genetics in positive psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 19). Oxford Academic.

- Keyes, C. L., Martin, C. C., Slade, M., & Martin, C. C. (2017). The complete state model. In Wellbeing, recovery and mental health (pp. 75–85). Cambridge University Press.

- Keyes, C. L., Sohail, M. M., Molokwu, N. J., Parnell, H., Amanya, C., Kaza, V. G. K., Saddo, Y. B., Vann, V., Tzudier, S., & Proeschold-Bell, R. J. (2021). How would you describe a mentally healthy person? A cross-cultural qualitative study of caregivers of orphans and separated children. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1719–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00293-x

- Kirk, D. (2013). Educational value and models-based practice in physical education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(9), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.785352

- Kryza-Lacombe, M., Tanzini, E., & Neill, S. O. (2019). Hedonic and eudaimonic motives: Associations with academic achievement and negative emotional states among urban college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(5), 1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9994-y

- Lang, C., Feldmeth, A. K., Brand, S., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., Pühse, U., & Gerber, M. (2016). Stress management in physical education class: An experiential approach to improve coping skills and reduce stress perceptions in adolescents. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2015-0079

- Maclean, L., & Law, J. M. (2022). Supporting primary school students’ mental health needs: Teachers’ perceptions of roles, barriers, and abilities. Psychology in the Schools, 59(11), 2359–2377. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22648

- Ministry of Education and Employment. (2012). A national curriculum framework for all. NCF.pdf (gov.mt).

- Ministry of Health. (2019). A mental health strategy for Malta 2020–2030: Building resilience, transforming services. https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/Documents/National-Health-Strategies/Mental_Health_Strategy_EN.pdf

- National Statistics Office. (2023). Regional statistics Malta 2023 edition. Regional-Statistics-Malta-2023-Edition.pdf (gov.mt).

- Oliffe, J. L., Kelly, M. T., Gonzalez Montaner, G., & Yu Ko, W. F. (2021). Zoom interviews: Benefits and concessions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211053522.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). Education at a glance 2018: OECD indicators. READ online (oecd-ilibrary.org).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). Making physical education dynamic and inclusive for 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/OECD_FUTURE_OF_EDUCATION_2030_MAKING_PHYSICAL_DYNAMIC_AND_INCLUSIVE_FOR_2030.pdf

- Ortner, C. N. M., Corno, D., Fung, T. Y., & Rapinda, K. (2018). The roles of hedonic and eudaimonic motives in emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 209–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.006

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Papadopoulou, M., & Sidorenko, E. (2022). Whose ‘voice’ is it anyway? The paradoxes of the participatory narrative. British Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3770

- Penney, D. (2000). Physical education, sporting excellence and educational excellence. European Physical Education Review, 6(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X000062003

- Quennerstedt, M. (2008). Exploring the relation between physical activity and health-a salutogenic approach to physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 13(3), 267–283.

- Rautio, P., & Jokinen, P. (2016). Children’s relations to the more-than-human world beyond developmental views. In B. Evans, J. Horton, & T. Skelton (Eds.), Play and recreation, health and wellbeing (pp. 35–49). Springer.

- Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022714

- Richards, K. A. R., Ivy, V. N., Wright, P. M., & Jerris, E. (2019). Combining the skill themes approach with teaching personal and social responsibility to teach social and emotional learning in elementary physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 90(3), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2018.1559665

- Rocliffe, P., Adamakis, M., O’Keeffe, B. T., Walsh, L., Bannon, A., Garcia-Gonzalez, L., Chambers, F., Stylianou, M., Sherwin, I., Mannix-McNamara, P., & MacDonncha, C. (2023). The impact of typical school provision of physical education, physical activity and sports on adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. Adolescent Research Review, 9 (2) 1–30.

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Cadenas-Sánchez, C., Estévez-López, F., Muñoz, N. E., Mora-Gonzalez, J., Migueles, J. H., Molina-García, P., Henriksson, H., Mena-Molina, A., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., & Catena, A. (2019). Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(9), 1383–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01099-5

- Rowling, L., Martin, G., & Walker, L. (Eds.). (2002). Mental health promotion and young people: Concepts and practice. McGraw-Hill.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Schramme, T. (2023). Health as complete well-being: The WHO definition and beyond. Public Health Ethics, 16(3), 210–218.

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish. Free Press.

- Shields, D. L., & Bredemeier, B. L. (2011). Contest, competition, and metaphor. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 38(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2011.9714547

- Smee, C., Luguetti, C., Spaaij, R., & McDonald, B. (2021). Capturing the moment: Understanding embodied interactions in early primary physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(5), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1823959

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). Sage.

- Thomas, D. R. (2017). Feedback from research participants: Are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2016.1219435

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2014). World-wide survey of school physical education. https://en.unesco.org/inclusivepolicylab/e-teams/quality-physical-education-qpe-policy-project/documents/world-wide-survey-school-physical

- White, S. C. (2008). But what is wellbeing? A framework for analysis in social and development policy and practice.

- Wilkinson, S., Penney, D., & Allin, L. (2016). Setting and within-class ability grouping: A survey of practices in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 22(3), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15610784

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health fact sheets. Mental health (who.int).