ABSTRACT

The study of land use dynamics in emerging cities will inform sustainable development in the future. Doha has witnessed urban transition phases. The study objectives are: (1) conduct a review of neighbourhood planning theories and (2) develop a prototype for downtown land use dynamics in emerging cities. The developed prototype considers physical and socioeconomics aspects. The research tools are: content analysis of real-estate reports, observation study, and preferences survey. Fereej Abdulaziz has been selected as an example. The study emphasizes the importance of policymakers in analysing the changes of neighbourhood, with an overarching aim of guiding future growth.

Introduction

Emerging cities have become major sites for business investment with unique opportunities to drive economic growth and foster social inclusion (UN Habitat Citation2016). Prominent examples of emerging cities include the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) cities. Other worldwide cities include, but are not limited to: Jakarta, Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, New Delhi, etc. The dynamics of emerging cities will result in three main aspects. Namely, new urban living aimed at the well-being of people, new patterns of behaviour and resource use, and new opportunities. According to IDB (Citation2014), an emerging city is an urban area classified as intermediate in terms of the total population, with a steady population and economic growth. Another definition outlines that an emerging city has characteristics of a developed city but does not satisfy standards to be termed a developed or a global city (MSCI Citation2014). The urban area tends to have high population growth and high growth rates in gross-domestic-product per capita, demographic and economic trends that help to boost returns. In such cities, there is an important opportunity to build it right the first time, with respect to the infrastructure that will determine the economic competitiveness and quality of life for decades (IDB Citation2014).

In the face of rapid urban growth and population growth, many emerging cities have accrued huge housing shortages. Housing is providing employment and contributing to urban growth (UN Habitat Citation2016). The future of cities and the benefits of urban growth strongly depend on future approaches to housing, specifically relating to land use dynamics which allow for a holistic development and sustainable growth. The study of dynamics of emerging cities enriches the understanding of the distinctive urban development processes. This article makes an attempt to examine the land use dynamics in the emerging Doha city. The case of Doha city presents a unique study, witnessing several transition phases in the rapid urbanization process. Like many other cities in the Middle East, Doha is becoming increasingly important in the long-term regional and global context. Doha has witnessed fundamental change in its urban fabric over the recent years. The introduction of a new vision for Doha as a developing regional and global service hub by Qatar has led to the initiation of various strategies in the form of public investments.

The investigation of land use dynamics of downtown neighbourhood in Doha is developed based on prominent theories on neighbourhood planning, including the physical and socioeconomic perspectives for emerging cities. The analysis of the physical and socioeconomic aspects aims to develop a prototype for neighbourhoods in emerging cities. This is with the aim of achieving an improved policy-oriented vision for planning. Accordingly, the objectives of this paper are to: (1) conduct a critical review of neighbourhood planning theories across the international, regional, and local contexts of emerging cities and (2) develop a prototype for Downtown Land Use Dynamics in emerging cities and to be applied for the case study of Doha city.

Research background

Neighbourhood planning allows local communities to develop a vision and to shape the neighbourhood’s development and growth. A particular form of social reproduction includes the following human activities: daily life, social interaction, political and economic commitment, is taking place (Patricios Citation2002). A neighbourhood is a group of people who share services and some level of cohesion in a geographically bounded place. Three keywords defining neighbourhoods are noted as; place, people and cohesion. Among these terms, place is the most noticeable term to distinguish neighbourhoods from other terms like community. Community refers to a group of people with a unity of values, beliefs, circumstances, interests, and culture regardless of geographical boundary (Chaskin Citation1998; Keller Citation1968). Neighbourhoods, on the other hand, are communities with a more tangible and geographic concept that is useful for many planning purposes such as analysis, service, delivery, and intervention (Wellman and Leighton Citation1979; Forrest and Kearns Citation2001; Mullan, Phillips, and Kinman Citation2004). Hence, defining the geographical and physical conditions of a neighbourhood provides the foundation for planning and research at the neighbourhood level.

The idea of grouping housing units into a neighbourhood was proposed in the 1920s after the industrial revolution (Silver Citation1985). The Neighbourhood Concept was first introduced in the 1920s by Clarence Perry to solve urban issues related to housing areas and city centres (Perry Citation1929). The concept has provided specific guidelines for the spatial distribution of housing, community facilities, businesses, and streets (Verburg et al. Citation2004; Serag El Din et al. Citation2013). Perry (Citation1929) has studied Forest Hill Gardens neighbourhood in New York and developed the basic elements for neighbourhood planning. These elements are applicable for neighbourhoods in emerging cities as they aim at adapting population growth in urban centres. It also took into account the level of accessibility of residents from their houses to schools and community centres (Rohe Citation2009; Brody Citation2013). According to Patricios (Citation2002), Perry has stated that the ‘neighbourhood unit is described as a scheme of arrangement for the family life community’, where it offers residents a convenient access to the neighbourhood facilities such as schools, parks, shops, and public facilities.

Schoenberg and Rosenbaum (Citation1980) have supported Perry’s theory in terms of the neighbourhood elements. They have emphasized that a neighbourhood exists if boundaries are identified, a name is associated with the area, an institution is centralized and neighbours share at least one common tie through a social network or shared use of public space. Wang (Citation1965) has redefined the physical elements of the neighbourhood to include social aspects, and the neighbourhood principles have been modified as: (1) people and environment, (2) street system, (3) institution, (4) shopping centre, (5) housing, (6) recreation, and (7) school. A neighbourhood is an area for people to live and to possess a house, where they have people with different sizes of families, incomes, and preferences (Wang Citation1965; Delmelle, Haslauer, and Prinz Citation2013; White Citation2015). Similarly, Gillette (Citation1983) has considered the social aspects should not only have physical proximity of houses, school, shops, and institutions but should have many social activities.

The theoretical basis of this paper is from the original theory developed by Clarence Perry and supported by other theories. The Neighbourhood Concept theory has contributed to improve the standards of developing residential environments. This is based on six solid principles: (1) an institution at the centre of the neighbourhood; (2) local shopping areas along the perimeter; (3) area dedicated for parks and open spaces; (4) arterial streets along the perimeter; (5) local street network; and (6) size of the neighbourhood for the preservation of positive social value (Perry Citation1929; Choguill Citation2008). Depending on the size, level of cohesion and services shared, neighbourhoods are defined at multiple scales.

Prior literature introduces a hierarchy of neighbourhoods based on the criteria of physical conditions and social relationships. Physical conditions are most commonly associated with clarifying a neighbourhood hierarchy. In the 1940s, Pan Nelson analysed a hierarchy of neighbourhood. In terms of the services provided, public education, in particular, was viewed to associate with each category of neighbourhood (Park and Rogers Citation2014). In 1945 Nelson (cited in Bailly Citation1959) introduced four categories of neighbourhoods as follows :

A residential neighbourhood is the smallest unit organized around children-related facilities. It has a population of about 1,200.

A neighbourhood is usually organized around an elementary school facilitating with, community centres. It has a population of about 5,000.

A district has a secondary school that is surrounded by social and recreational facilities. It has a population of about 25,000.

A section is the largest category which is likely to have a college with a cultural centre, social and recreational facilities. It has a population of about 75,000.

Moreover, Marans and Rodgers (Citation1975) also used physical conditions and separated the neighbourhood into three categories as follows:

A micro-neighbourhood refers to a very small neighbourhood with an immediate cluster of housing units.

A macro-neighbourhood is often characterized by an elementary school. It is larger than a micro-neighbourhood and is likely to be a neighbourhood-based community scale.

A community which is frequently defined by a political jurisdiction.

The American Planning Association (Citation2006), classified neighbourhood based on Chaskin (Citation1998) and Suttles (Citation1972), and presented the physical requirements of a neighbourhood into three categories:

Physical closeness of face-block neighbourhoods encourages individual and interpersonal relationships,

A residential neighbourhood consists of several face-blocks, in which it shares amenities and services to evoke direct participation from residents,

An institutional neighbourhood includes several residential neighbourhoods and bounded by official limits of institutions. Its size should accommodate several services and financial institutions.

In Hakim (Citation1986) study, the development of building and urban design principles focused primarily on housing and access. The development was integrated based on Islamic law, becoming semi-legislative in nature. As building and achieving sufficient development of communities is a continuous process, related rules and guidelines were in constant demand. Hakim (Citation1986) has incorporated the physical components of downtown area in an Arabic-Islamic city which includes: grand mosque, a government office and a market.

Birch et al. (Citation1979), Galster and Hesser (Citation1982) have concluded four categories for neighbourhood planning:

The primary neighbourhood refers to a one-block radius around the home where children can play and consist of a multiple of housing units.

The secondary neighbourhood is an area where it comprises several blocks and residents have a relatively homogeneous socioeconomic status.

A heterogeneous neighbourhood shares means such as identity and facilities. It is often bounded by a shared school, district service or major transportation arterials.

Subareas of cities refer to larger areas that share an official identity such as suburbs, townships, or sub-metropolitan regions.

Focusing more on personal relationship and political voice than physical conditions, Jacobs (Citation1961) proposed three levels of neighbourhoods.

Neighbourhoods highlight the acquaintances and personal relationships through the existence of streets. Because of overlapping perceptions and personal relationships, the boundaries of street neighbourhoods are not well defined. Although it was hard to say which elements of the neighbourhoods is more important, she highlighted street neighbourhoods as the smallest but the most vital and effective self-governing units.

A large district refers to an area with a recognizable name and consists of 100,000 or more people. Large districts have moderate political power to meet the needs of residents, visitors, and workers.

The city as a whole is rarely referred to as a neighbourhood. However, she assumed the city would be one of the neighbourhood units having a complete range of services and common interests allowing people to associate with each other. She argued that bonding to the city as a whole is the greatest asset.

In the same field, Lang and Moleski (Citation2010) have defined the social dimension of neighbourhoods through functionalism. The study focuses more on the socioeconomic aspects of communities, which are based on interaction patterns among their members. Their focus is centred around psychological aspects of communities, with a sense that people have something in common with each other. They further described affordances of different behavioural patterns in community formation, which is the main concern in the functionalism concept. Both authors have classified the term neighbourhood into three categories:

Complete territorial communities

Communities of limited liabilities

Community as society

The ground base theory for neighbourhood planning was founded first by Perry (Citation1929) where he established the basic aspects of the formation of any neighbourhood (Herbert Citation1963; Lawhon Citation2009; Dempsey Citation2012). From this theory, other researchers and theorists have based their studies on Perry’s concept (Citation1929) of categorizing the aspects into two dimensions, as to be taken into account when analysing a neighbourhood; physical and socioeconomic aspects. One of the theories that evolved from Perry (Citation1929) theory belongs to (Park and Rogers Citation2014), introducing that the classification of neighbourhoods is based on central arrangement of physical educational elements. The social aspect in the theory is interpreted based on the population size. Alternatively, Marans and Rodgers (Citation1975) classify neighbourhoods based on the neighbourhood size, in which the facilities are being provided based on the number of housing clusters to create a social interaction between residences. The classification of Chaskin (Citation1998) and Suttles (Citation1972) is based on the spatial arrangement of physical facilities in relation to the social aspects in either face-block/s or supported by facilities. The classification of neighbourhoods in Islamic cities as stated by (Hakim Citation1986) is based on the mix of primary uses of physical components, which are essential to the formation of social relationships and neighbouring principles. Birch et al. (Citation1979) and Galster and Hesser (Citation1982) classified neighbourhoods based on physical aspects, in relation to the socioeconomic status of the residents, with reference to the income level. Jacobs (Citation1961) defined neighbourhoods based on the physical boundaries, in which the street network defines the neighbourhood. The boundaries provide a complete range of services and common interests allowing individuals to associate with each other. The understanding of a neighbourhood can be investigated through the socioeconomic aspects, which were discussed in Lang and Moleski (Citation2010) theory, as the cultural background of the residents can assist in defining a neighbourhood.

In reference to the above, the prototype developed for emerging cities is based on previous theories. This includes the physical and social requirements for neighbourhood planning. The framework has further modified the requirements to include socioeconomic factors, such as the income level. Therefore, the concluded factors are shown in () to include the following:

Physical factors: land use mix, boundaries, housing, and the centre of the neighbourhood.

Socioeconomic factors: income level, and cultural background of the residents.

Methodological approach

Three main research tools were implemented in this study:

A content analysis of real estate reports and census data based on governmental documents have been reviewed to understand the neighbourhood planning from a governmental point of view. It aims at analysing the changing conditions of the local market, which affects the dynamics of the physical and socioeconomic aspects of neighbourhoods.

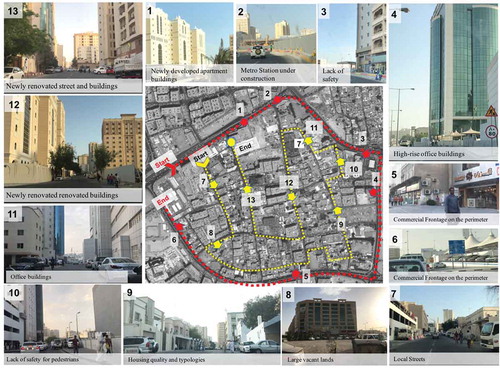

An observation study of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood (physical aspects): which is conducted to investigate the physical features including the activities performed by the residents. Fereej Abdulaziz was observed twice during weekdays and twice during weekends following a defined circulation route, during afternoon and evening times. In the beginning, the observation was dedicated to the investigation of the neighbourhood’s perimeter and surrounding boundaries. This has resulted in annotating the external observation route. The next stage of the observation was dedicated to the investigation of local roads and developments where various features have been recorded; which has resulted in annotating the internal observation route.

A questionnaire survey of residents’ preferences in Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood has been distributed to include 130 residents’ samples, where 103 are valid and to be considered in the survey. The survey aims at understanding physical and socioeconomic aspects from residents’ point of view in neighbourhoods. According to questionnaire survey, expatriates comprise the highest percentage (99%) of the total respondents (Asians, Arabs, and Westerners), while nationals (Qataris) comprise 1% of the total respondents. Male respondents are more than female respondents (56% males and 44% females). This confirms that the questionnaire data are parallel to Doha’s actual population profile, in which the majority of residents are expatriate males (67% males and 33% females) (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics Citation2015).

In emerging cities like Doha, the neighbourhood is in a transition phase from a residential neighbourhood into a cultural and economic neighbourhood. Urban intensification has given rise to the replacement of traditional residential and local retailing with modern offices and apartment blocks. During this process, many Qatari households have relocated to their preferred lower density neighbourhood lifestyles in Doha suburban areas. More recently, iconic cultural complexes such as the Museum of Islamic Art along with innovative urban regeneration schemes, namely, Souq Waqif and Musheireb Downtown Doha are providing a strong cultural heritage focus for a revitalized downtown Doha.

The downtown area of Doha is the economic, cultural, and administrative heart of the country. This is where urban design and public realm improvements will be undertaken to improve the quality of the living and working environments. Therefore, the downtown neighbourhoods are selected for a study based on the following:

The different development stages that took place during previous decades, which have resulted in diverse urban and land use changes in the area,

The imbalanced demographic structure where expatriates are the dominant population in the area and

The governmental vision to revive the old centre of Doha, which plays a major role in enhancing city identity, memory and belonging.

The rethinking of the urban structure and land use pattern will enhance the downtown neighbourhoods and will firmly define their role as the premier location for cultural and community living in Doha.

Land use dynamics in emerging cities: the case of Doha–Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood

In this section, a brief historical background is presented to introduce the study area of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood which is selected based on: its typical land use pattern of Doha downtown neighbourhoods, demographic structure of the expatriate population, and governmental vision of retrofitting its physical form. Also, the analysis of the physical aspects of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood through analysing the physical aspects (land use mix, neighbourhood boundaries, housing, and centre of the neighbourhood) and the socioeconomic aspects (income level and cultural background) is concluded. The analysis of this section will propose an innovative insight into land use dynamics for downtown neighbourhood in emerging cities.

Historical background

During the second half of the twentieth century, Doha has witnessed its first urbanization period due to the increase in oil production processes. The rapid economic growth has led to the transformation of Doha’s built environment. The governmental strategies of economic diversification and living condition improvements were set to build the city image (Hutzell, El Samahy, and Himes Citation2015). This has resulted in rapid population growth and high expatriates-to-nationals ratio.

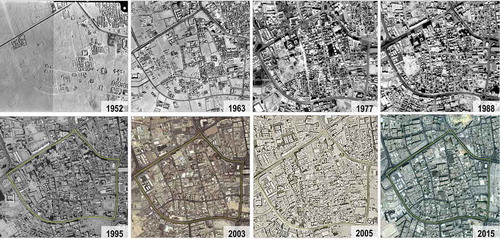

The urban fabric of Doha was shaped as a result of landfill policies over the recent decades, which began in the downtown area, forming a radial form of planning. Throughout the years, the planning policies in Doha have been expanding towards the Northern and Western directions, creating various projects that contribute to the urban development (Nagy Citation2008; Murray Citation2013; Al Shawish Citation2015). Since the 1960s, urban planning in Doha has envisioned the development of neighbourhoods aiming at creating communities away from the downtown area (). According to Shandas, Makido, and Ferwati (Citation2017), the typical neighbourhood planning in Doha has been formed based on the planning of the road network. Within the road grids, it was anticipated that there would be neighbourhood units.

Figure 2. Evolution of neighbourhoods of Doha based on the attached housing agglomerations (Source: Skyscraper City Citation2007; Al Malki Citation2017; Lockerbie Citation2018).

In the North of Doha, a new downtown area has been developed by the government as the premier location for business and high-end residential living in the city (Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2014). It is administered as an expansion of a growing modern city centre.

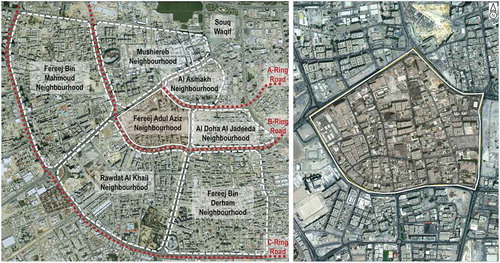

Fereej Abdulaziz is located in Zone 14, between the B and A Ring roads within the municipality of Doha. It is located in a central location in the downtown area where significant projects and areas are adjacent. Fereej Abdulaziz is located near popular places with historical and national significant landmarks, such as Souq Waqif. It is surrounded by Mushiereb and Al Asmakh neighbourhoods from the North, Al Doha, Al Jadeeda and Fereej Bin Derham neighbourhoods from the East, Fereej Bin Mahmoud neighbourhood from the West, and Rawdat Al Khail neighbourhood from the South. Several main roads, specifically the A-Ring and B-Ring roads define the neighbourhood ().

Figure 3. The location of the study area: Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood in Doha as highlighted (Source: Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2015, adapted by the authors).

Fereej Abdulaziz is one of the early-formed neighbourhoods in the downtown area. It has high-density housing, cultural, and economic activities. It is comprised of mid to high-rise apartment buildings surrounded by retail activities. Another prominent aspect of the neighbourhood is the inhabitants who are predominantly Asian male workers.

Fereej Abdulaziz has witnessed a rapid urban and population growth since the 2000s. In the 2015 census conducted by the Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, it was revealed that the neighbourhood had a population of 15,706, with 447 residential and residential/commercial buildings, and 28 establishment buildings. The population density as of 2015 is 29,513 people/km2, which indicates that Fereej Abdulaziz is highly dense as compared to other neighbourhoods of the same size. It is noted that Fereej Abdulaziz’s population has increased rapidly from 2004 onwards, and the population increased by approximately 315 (12%) between 2010 and 2015. The male population was 10,517 and female population was 5,189. Therefore, it can be inferred that Fereej Abdulaziz is male-dominant with the male population comprising 67% of the neighbourhood’s total population (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics Citation2015).

The urban morphology of Fereej Abdulaziz has evolved combining both organic and grid-like planning. The earliest houses in the neighbourhood were traditional Arabic houses within a closely intertwined network of streets and passageways. The development of Fereej Abdulaziz has started since the 1950s where few houses were scattered in remote settings (Jaidah and Bourennane Citation2009). Streets were constructed to define the perimeter of the neighbourhood, and the initial planning of land parcels had started.

During the 1960s, stand-alone houses became a popular housing typology. New land uses have been introduced to the neighbourhood, such as commercial, industrial and religious buildings (for example, mosques). In the 1970s, high-rise buildings were constructed in the neighbourhood. This period has shown a clear vehicular influence, in which a new requirement for parking spaces has appeared.

In the 1980s, several governmental institutions have evolved as a new land use. Ring roads have evolved defining the boundaries of the downtown neighbourhoods in Doha. Expatriates have started to inflow in response to the rapid urbanization. New housing typologies have emerged such as apartments and hotels, which are designated as multi-family residential in the planning documents.

In the 2000s, local streets became clearly defined, and vacant lands have been utilized as random parking areas. Expatriates comprise the highest percentage, occupying 89% of the total population in Doha in 2017 (Snoj Citation2017). Since then, the residents of Fereej Abdulaziz are almost all expatriates. The downtown area has started to be characterized by overcrowding, high number of single male expatriates and a predominantly low-income expatriate population. With the absence of a clear planning vision, the neighbourhood has failed to promote a quality of urban life. Nationals have moved away to settle in suburban neighbourhoods, leaving the downtown with low conditions in terms of physical, mobility and social aspects.

During the 2010s, new governmental projects have started focusing on reviving the downtown area, where there were strong needs to define the character of the city. The concentric urban structure, which dominated the early evolution of Doha, is still visible today. This forms a key element in the legibility of Doha and its downtown area ().

Figure 4. Urban evolution of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood in Doha (Source: Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2015), Archive Department of Doha Satellite Imageries in 1995, 2003, and 2010.

Analysis of the physical aspects

In this section, the physical aspects of Fereej Abdulaziz are analysed to investigate the physical environment of the neighbourhood. This includes the analysis of: land use mix, boundaries, housing, and the centre of the neighbourhood.

Land use mix

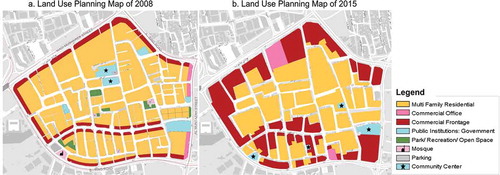

In terms of the land use mix, the residential land use makes-up most of Fereej Abdulaziz, followed by commercial land use. According to the land uses in 2008, other uses are planned to provide urban services, such as recreational uses (green open spaces), religious uses (mosques), community centres, and governmental institutions (). According to Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (Citation2015), the total number of completed buildings in Fereej Abdulaziz is 475 buildings, in which 442 buildings are residential, 5 buildings are mixed-use (residential and commercial), and 28 are establishment buildings (religious, governmental institutions, etc.)

Figure 5. Land use planning map of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood (Source: Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2015).

The updated land use in 2015 of Fereej Abdulaziz shows that the amount of commercial land uses has increased as compared to the 2008 land use. The increase can be viewed as a result of governmental vision to reinforce the commercial identity of downtown Doha through providing new economic activities (Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2014). Open spaces have been removed and replaced by residential land uses and community facilities. Residential land uses remained as multi-family residential. The land use of commercial offices has been relocated along the Northern and Southern sides of the neighbourhood’s perimeter, ().

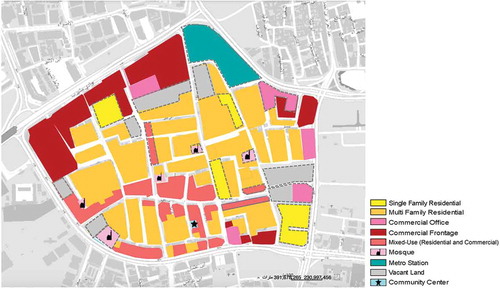

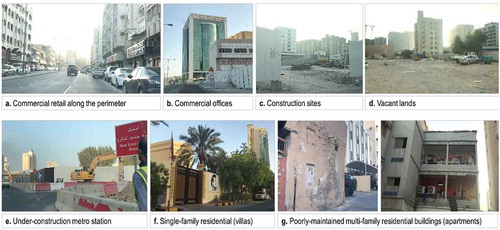

The observation of the existing land uses shows more homogeneity of land use mix in comparison to the planned land use in 2015. Single-family residential (such as villas) and utility land uses (such as the under-construction metro station, have been observed along the perimeter of Fereej Abdulaziz. Significant types of commercial uses have been also observed, such as restaurants and hotels. However, a number of vacant lands exist in the centre and perimeter areas of the neighbourhood ().

Figure 6. Existing land uses where land use changes are outlined (Source: Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2015, adapted by the authors based on the observation survey).

Fereej Abdulaziz is characterized by mixed-use commercial frontage in the form of shops along the perimeter, and commercial offices on the Eastern side (). Construction sites of new apartment buildings are distributed across the neighbourhood (). Numbers of vacant lands are used as random parking spaces, and as sites for construction wastes in some locations (). The Northern end of the neighbourhood is a large-scale construction site for the metro station (). Lack of open spaces causes inefficiency of land use planning and prevents the support of public activities. Few existing villas represent high-quality housing in the neighbourhood, as compared to the poorly maintained apartment buildings in surrounding areas ().

Figure 7. Significant differences in the land use mix in Fereej Abdulaziz (Source: the authors based on the observation survey).

According to the survey of residents’ preferences, it is concluded that 77% of the respondents prefer to have mix of land uses. A high preference was given to commercial uses, followed by educational and religious uses (). In terms of open space preferences, 66% of the respondents preferred the presence of open spaces in Fereej Abdulaziz, which can be provided in the future. Open spaces would improve the physical environment in view of three benefits: diversify the land use in which recreational uses would be provided, improve the neighbourhood’s climate and ecology, and create an aesthetically appealing urban environment. ().

Figure 8. Residents’ preferences in terms of land use mix in Fereej Abdulaziz (Source: the authors based on the questionnaire survey).

Land use mix in Suttles (Citation1972) and Chaskin (Citation1998) study is based on the spatial arrangement of the neighbourhood, in which it should accommodate several services and financial institutions along with the residential. Land use mix is emphasized in the development of Islamic cities as discussed by Hakim (Citation1986). The neighbourhood formation is based on three basic land uses: religious, retail and institutional along with residential land use. In the case of Fereej Abulaziz, it follows a governmental vision for economic activities; therefore, the existing land use mix is retail-oriented.

Neighbourhood boundaries

The boundaries of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood are defined by main streets, in which four main streets provide direct access to the neighbourhood facilities. The accessibility is analysed based on vehicular, pedestrian, and cyclist movements. The analysis aims at improving local conditions for walking, cycling, as well as facilitating safe access to the neighbourhood facilities (such as shops, mosques, parks) and public transport services. ().

The traditional urban patterns of pedestrian streets (sikka) that reflect the past have been lost and replaced by vehicle-dominated streets and indiscriminate parking that create pedestrian barriers, isolating residents from the sense of community. It has been observed that the streets lack signage system, which affects the neighbourhood’s legibility. Therefore, social connectivity and legibility are constrained in most locations. ().

Figure 10. Vehicle-dominated streets where safe mobility considerations for pedestrians are lost (Source: the authors based on the observation survey).

According to the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (Citation2014), higher densities of population have been exhibited within the C-Ring Road. However, outside the C-Ring the population densities are far less, with no promotion of mixed-use centres or employment hubs to promote increased densities, accessibility, convenience and vitality. This existing pattern of development has promoted low-density urban sprawl, which in turn is highly dependent on the private vehicle for access to highly centralized locations of employment, shopping, and public facilities.

Based on the survey of residents’ preferences, 50% of the respondents considered work travel distance as a significant travel consideration. Therefore, streets connecting workplaces and houses should be highly accessible. Moreover, diverse modes of travel were preferred to access the different facilities in Fereej Abdulaziz. The main mode of travel is public transportation (75% of the respondents) which implied the need for integrating taxis and public buses in the street network design ().

Figure 11. Accessibility preferences in Fereej Abdul Aziz neighbourhood (Source: the authors based on the questionnaire survey).

The neighbourhood boundaries are defined in Jacobs’s study (Citation1961) in the form of streets which are emphasized as the smallest and the most vital and effective self-governing units. Suttles (Citation1972) has stated that the neighbourhood should be bounded by official limits of institutions. In the case of Fereej Abdulaziz, main roads and metro stations define the neighbourhood boundaries. The North-Eastern edge of the neighbourhood is developed by the government as transit-oriented area.

Centre of the neighbourhood

The centre of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood is determined by attributes of both the activity patterns and the transportation system. Several nodes are considered as central gathering nodes in the neighbourhood based on the spatial distribution of activities, as well as the transportation system that links such activities.

The main type of activity in Fereej Abdulaziz is commercial transactions and retailing, which define the main purpose for pedestrians to move between different land uses. The significant presence of pedestrians in the neighbourhood reflects that most of the trips are walking trips.

Despite the importance of the pedestrian travel mode, the design consideration for pedestrian facilities across Fereej Abdulaziz is very minimal. According to the observation survey, vehicles are considered the main mode of travel with a clear absence of pedestrian sidewalks and cyclist lanes (). Thus, the neighbourhood is characterized by unsafe street life where pedestrians and cyclists are mixed with vehicles (). Consequently, the central nodes in Fereej Abdulaziz need improvement to comfortably accommodate all street users and to support the adjacent land uses ().

Figure 12. General street life in Fereej Abdul Aziz neighbourhood (Source: the authors based on the observation survey).

In 1945 Nelson defined the neighbourhood centre with educational land use as a central node surrounded by residential and recreational land uses (cited in Bailly Citation1959). Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood does not have a clear centre. People tend to gather in central nodes distributed across the neighbourhood such as mosques and mega retail shops.

Housing

Housing is a significant social parameter in investigating the neighbourhood dynamics. A well-planned mix of housing supports socially cohesive communities while enabling efficient urban operation.

According to the Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (Citation2015), the rapid population growth in Doha is anticipated to continue over the years as employment growth increases in conjunction with Qatar’s position as a host for the FIFA World Cup 2022. In addition, Fereej Abdulaziz has a total of 3,324 housing units in which 40 units are villas, 245 units are Arabic houses (traditional Arabic houses or single-story villas), 2,990 units are apartments, and 49 units are separate rooms as part of establishment buildings. Housing in Fereej Abdulaziz is represented in the form of mixed apartment typologies. Based on the regulations, the neighbourhood is originally planned for 10 storey apartment housing typologies: 20% studio apartments, 40% one-bedroom apartments, 30% two-bedroom apartments, and 10% three-bedroom apartments of the total housing (Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2014). Despite this, it can be indicated that housing in Fereej Abdulaziz lacks a regulated mix of housing typologies.

The quality of housing is considered low as a result of the random practices of residents. Random gatherings in front of retail shops were observed along the street, which indicates that there is a need for open spaces. The existence of the same can provide recreational and aesthetic values to residents as well as serving a variety of psychophysiological values related to neighbourhood attachment and community belonging. This would effectively discourage nationals to move back to downtown Doha, therefore limiting future housing and causing imbalance to the demographic structure of the neighbourhood.

According to the survey of the residents’ preferences, 48% of the respondents preferred diverse types of housing such as villas followed by 26% for compound apartments. Lifestyle-based housing was preferred through the development of residential compounds where 72% of the respondents preferred serviced compounds and 28% prefer high-rise apartments. Residential compounds provide mixed housing typologies supported by common gathering locations where diverse housing attributes such as typology and cost can be met. Generally, the social environment of the neighbourhood would be revived if diverse housing typologies were accessible to diverse groups of residents. ().

Figure 13. Housing preferences in Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood (Source: the authors based on the questionnaire survey).

Marans and Rodgers (Citation1975) have highlighted that housing defines the neighbourhood size. When more housing blocks are provided, more facilities are introduced to support the neighbourhood needs. Birch et al. (Citation1979) and, Galster and Hesser (Citation1982) have based their discussions on housing as the major element that defines the residents’ type, identity, and facilities of the neighbourhood. In the case of Fereej Abdulaziz, housing is the dominant land use as it plays a major role in defining the physical environment of the neighbourhood. Housing reveals the demographic structure of the residents and the type of activities in the area.

Analysis of the socioeconomic aspects

In this section, the socioeconomic aspects of Fereej Abdulaziz are analysed to investigate the social conditions in the neighbourhood based on the income level and the cultural background of the residents.

Income level

According to Colliers International Doha (Citation2014), an analysis of monthly income levels suggests that the low-income bracket is defined as less than 20,000 Qatari Riyals which affords rental levels between 1,700 and 6,800 Qatari Riyals per month. In Fereej Abdulaziz, the neighbourhood is categorized as a community which combines low-income expatriates. According to the questionnaire survey, the income level of Fereej Abdulaziz residents is characterized as low, in which 63% of the respondents earn a monthly salary less than 20,000 Qatari Riyals. Housing diversity and affordability are, therefore, considered a critical need for the local residents of the neighbourhood. ().

Figure 14. Income level of residents in Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood (Source: the authors based on the questionnaire survey).

Housing availability for low-income residents is not envisioned where medium to low-quality apartments are dominant. Most of the housing is devalued through neglect, lack of services, and incompatible built form ().

Figure 15. Income level indication based on the general housing quality in Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood (Source: the authors based on the observation survey).

Birch et al. (Citation1979); Galster and Hesser (Citation1982) have discussed the socioeconomic aspects of the neighbourhood and the income level of the residents. The neighbourhood should share the common facilities where it comprises several housing blocks, and residents have a relatively homogeneous socioeconomic status. In the case of Fereej Abdulaziz, this is reflected on the residents who use the common neighbourhood facilities which correspond to their income level.

Cultural background

According to the Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (Citation2015), the population profile of Doha shows that the majority of the expatriate population are males (67% males and 33% females). Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood has male dominance with different cultural backgrounds (56% males and 44% females). According to the questionnaire survey, expatriates (Asians, Arabs, and Westerners) comprise the highest percentage (99%) of the total respondents, while nationals comprise 1% of the total respondents.

Lang and Moleski (Citation2010) have referred to the cultural background of residents which indicate that they have something in common. The cultural background describes the affordances of different patterns of behaviour settings in community formation. In the case of Fereej Abdulaziz, territorial communities are observed to be dominant in several locations which is based on the gatherings of similar cultural groups.

A developed prototype for downtown land use dynamics: the case of Doha – Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood

In this section, the analysed aspects land use dynamics of Fereej Abdulaziz are interpreted into a prototype that can be used for downtown neighbourhoods in emerging cities. The prototype is developed based on the existing conditions of Fereej Abdulaziz and the applicability of the analysed aspects to define the neighbourhood characteristics. The prototype reconsiders the urban structure and land use pattern of Fereej Abdulaziz which will enhance the downtown neighbourhoods and will define their role as the premier location for cultural and community living in Doha. It combines the field observation for the physical environment, and residents’ preferences for the socioeconomic characteristics of Fereej Abdulaziz.

The observation route was based on the physical aspects of the neighbourhood. The observation was dedicated to the investigation of the neighbourhood’s perimeter and surrounding boundaries (external observation route). The next stage of the observation was dedicated to the investigation of the local roads and developments where various features have been recorded (internal observation route), ().

Figure 16. Annotated map of the observation survey route in Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood (Source: Ministry of Municipality and Environment Citation2015, adapted by the authors).

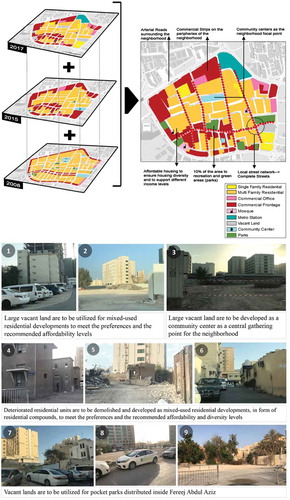

The prototype integrates the developed land use map by Ministry of Municipality and Environment (Citation2015) in addition to the edited map by authors based on the observation survey. The land use prototype is based on the analysis of the physical and socioeconomic aspects, in which both rely on the content analysis, field observation, and residents’ preferences.

In the developed prototype, a community centre is introduced as a physical central node of Fereej Abdulaziz to create the base for social gathering and community bonding. Vacant lands in the South, East, and West of Fereej Abdulaziz have been transformed to a variety of land uses such as green open spaces for recreation and urban revival purposes.

Likely, major improvements to the neighbourhood boundaries and mobility are attempted where accessibility, diversity, and connectivity should be considered. The complete street concept is recommended for the local street network where all modes of transportation are accommodated in a safe and standard design of public right-of-ways. The prototype attempts to improve through the provision of affordable lifestyle-oriented housing to ensure diversity, accessibility, and equity measures. This can be addressed through the provision of mixed-use residential developments (such as residential compounds) that account for housing preferences and diversity. Design suggestions for Fereej Abdulaziz are attempted to contribute towards a policy-oriented vision to downtown neighbourhood enhancement that serves the country’s approach towards urban and community development.

The prototype is developed based on the following; ():

The vacant land in the centre is replaced with a proposed community centre.

Single-family housing (villas) that belong to nationals are maintained to preserve the local identity of the neighbourhood.

Mixed-use residential developments are proposed to consider housing diversity, affordability, and accessibility. Residential compounds provide preferred housing typologies supported by facilities.

The metro station is envisioned to provide a transit-oriented improvement and enhanced accessibility measures in the neighbourhood where public transportation modes are provided.

A number of vacant lands along the perimeter have been replaced with green open spaces serving as the neighbourhood’s pocket parks for recreational and social bonding activities.

Commercial offices on the Eastern edge are maintained to diversify the land use mix.

Significant local roads are proposed to follow the complete streets concept where accessibility and safety measures are highly considered. Pedestrian walkways, cyclist lanes, and landscape buffers are introduced to the streets to account for safe mobility patterns in the neighbourhood, ().

Table 1. Proposed planning for Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood- Existing and Future development (Source: developed by the authors).

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, a prototype for downtown land use dynamics in emerging cities has been developed based on the original theory of Perry (Citation1929) and other theories that discussed the classification of neighbourhoods. The analysed aspects for land use dynamics of neighbourhoods in emerging cities were implemented to the case study of Doha city; Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood. The selected neighbourhood is one of the major downtown neighbourhoods in Doha as it is considered a major economic hub.

This study emphasizes the significance of studying land use dynamics through the physical and socioeconomic aspects. It is essential for policymakers to analyse the changes in the physical and socioeconomic aspects in order to place decisions that can support the future land use of the urban context. In the case of Doha, the extensive changes in land use dynamics occur as a result of major demographic and economic changes, and infrastructural development.

The overall analysis of the physical aspects (land use mix, boundaries, housing, and the centre of the neighbourhood) and socioeconomic aspects (income level, and cultural background of the residents) has led to developing a prototype for downtown neighbourhood planning for Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood. A summary of the study aspects is discussed based on the current realities of urban governance. This is to achieve an improved policy-oriented vision for neighbourhood planning and development in emerging cities.

It is concluded that the analysed aspects in Fereej Abdulaziz have resulted in disjointed built environment. The study aspects were ineffective in responding to urban realities, placing more emphasis on the economy and neglecting social, economic and cultural realms of development. Downtown Doha presents challenges that have resulted in an irregular and inadequate public realm. The trend of land use dynamics in downtown Doha is considered unregulated as it reflects the preferences of developers and not residents.

In terms of the physical aspects, the current zoning and development practices promote the domination of single-use commercial corridors, with the existence of a significant number of vacant lands. In terms of the boundaries of the neighbourhood, some of the commercial shops are difficult to access by foot or bicycle which are confirmed to be major modes of transportation. In downtown Doha, little attention is given to the design of neighbourhoods, where there is a lack of a clear central node. However, a promising governmental attempt highlights the transit-oriented development of the downtown which would fulfil the neighbourhood needs. In terms of the socioeconomic aspect, real estate developers have focused on quick housing solutions to accommodate the growing, diverse population. Less consideration is given to the low-income residents which are the majority of the downtown population.

The diversity of the downtown residents requires planners to consider community and participatory methods, otherwise they risk relying on misconceptions. An advocacy role can be played by real estate experts to encourage an informed public discourse on the development of downtown neighbourhoods in Doha.

The planning approach should play an active role in guiding the neighbourhood through sustainable solutions in terms of economic, social, and environmental expansions, which should be sought jointly and simultaneously through the planning process. This indicates that sustainable development should be an integral part of planning to respond to social needs and individual preferences, as in the case of Fereej Abdulaziz neighbourhood.

The concept of the developed prototype is applicable for other neighbourhoods in emerging cities where they are growing physically as a result of rapid urbanization and economic growth of the country. They have received expatriates and they are emerging because of novel features and properties that cannot be easily described by existing urban theories mainly delivered from typical cities. The city of Doha shares some features with other third world emerging cities in their undeveloped economies and challenges brought about by urbanization, which has created a distinctive political economy and urban spatial structure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al Malki, A. 2017. “Investigating Livability of Mixed-Use Neighborhood Case Study of Najma in Doha, Qatar: A Thesis in Urban Planning and Design.” Master’s thesis, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar. http://qspace.qu.edu.qa/handle/10576/5801

- Al Shawish, A. 2015. “Evaluating the Impact of Gated Communities on the Physical and Social Fabric of Doha City.” In Proceedings of the 12th International Postgraduate Research Conference, 67–79. http://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB_DC28789.pdf

- American Planning Association. 2006. Planning and Urban Design Standards. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Bailly, P. C. 1959. An Urban Elementary School for Boston. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Birch, D. L., E. S. Brown, R. P. Coleman, D. W. Da Lomba, W. L. Parsons, L. C. Sharpe, and S. A. Weber. 1979. The Behavioral Foundations of Neighborhood Change. Vol. 363. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Brody, J. 2013. “The Neighborhood Unit Concept and the Shaping of Land Planning in the United States 1912–1968.” Journal of Urban Design 18 (3): 340–362. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.800453.

- Chaskin, R. J. 1998. “Neighborhood as A Unit of Planning and Action: A Heuristic Approach.” Journal of Planning Literature 13 (1): 11–30. doi:10.1177/088541229801300102.

- Choguill, C. 2008. “Developing Sustainable Neighborhoods.” Habitat International 32 (1): 41–48. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2007.06.007.

- Colliers International Doha. 2014. Residential Market and Affordability Levels in Doha: Market Performance, Trends, and Affordability. Retrieved April 28, 2016, from http://www.colliers.com/-/media/562F03BEE6D54CA0B7BA140DF287C911.ashx?la=en-GB

- Delmelle, E., E. Haslauer, and T. Prinz. 2013. “Social Satisfaction, Commuting and Neighborhoods.” Journal of Transport Geography 30: 110–116. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.03.006.

- Dempsey, N. 2012. “Neighborhood Design: Urban Outdoor Experience.” International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home 29–42. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-047163-1.00542-7.

- Forrest, R., and A. Kearns. 2001. “Social Cohesion, Social Capital, and the Neighborhood.” Urban Studies 38 (12): 2125–2143. doi:10.1080/00420980120087081.

- Galster, G., and G. Hesser. 1982. “The Social Neighborhood an Unspecified Factor in Homeowner Maintenance?” Urban Affairs Quarterly 18 (2): 235–254. doi:10.1177/004208168201800205.

- Gillette, H. 1983. “The Evolution of Neighborhood Planning: From the Progressive Era to the 1949 Housing Act.” Journal of Urban History 9 (4): 421–444. doi:10.1177/009614428300900402.

- Hakim, B. S. 1986. Arab-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles. London: Kogan Page.

- Herbert, G. 1963. “The Neighborhood Unit Principle and Organic Theory.” The Sociological Review 2 (11): 165–213. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1963.tb01231.x.

- Hutzell, K., R. El Samahy, and A. Himes. 2015. “Inexhaustible Ambition Two Eras of Planning in Doha.” Architectural Design 85 (1): 80–91. doi:10.1002/ad.1857.

- IDB. 2014. “Emerging and Sustainable Cities: Methodological Guide.” https://issuu.com/ciudadesemergentesysostenibles/docs/methodological_guide__esci

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Jaidah, I., and M. Bourennane. 2009. The History of Qatari Architecture. Milan: Skira.

- Keller, S. 1968. The Urban Neighborhood: A Sociological Perspective. Vol. 33. New York: Random House.

- Lang, J., and W. Moleski. 2010. Functionalism Revisited: Architectural Theory and Practice and the Behavioral Sciences. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Lawhon, L. 2009. “The Neighborhood Unit: Physical Design or Physical Determinism.” Journal of Planning History 2 (8): 111–132. doi:10.1177/1538513208327072.

- Lockerbie, J. 2018. “The Old Buildings of Qatar.” http://www.catnaps.org/islamic/islaqatold.html

- Marans, W., and W. Rodgers. 1975. “Toward an Understanding of Community Satisfaction.” In Metropolitan America: Papers on the State of Knowledge, edited by A. H. Hawley, B. J. L. Berry, J. M. Degrove, and M. M. Webber, 310–352. Washington, DC: U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

- Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2015. The Simplified Census of Population, Housing and Establishments, 2015. Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/General/Census/Population_Households_Establishment_QSA_Census_AE_2015.pdf

- Ministry of Municipality and Environment. 2014. “Qatar National Master Plan: Doha Municipality Vision and Development Strategy.” 1 (1). http://www.mme.gov.qa/QatarMasterPlan/Downloads-qnmp/MunicipalityStrategy/English/Doha%20Dec%202017.pdf

- Ministry of Municipality and Environment. 2015. Archive Department. Doha Satellite Imageries in 1995, 2003, and 2010.

- MSCI. 2014. “Market Classification Framework.” https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/1330218/MSCI_Market_Classification_Framework.pdf/d93e536f-cee1-4e12-9b69-ec3886ab8cc8

- Mullan, F., R. L. Phillips, and E. L. Kinman. 2004. “Geographic Retrofitting: A Method of Community Definition in Community-Oriented Primary Care Practices.” Family Medicine 36 (6): 440–446.

- Murray, M. 2013. “Connecting Growth and Wealth through Visionary Planning: The Case of Abu Dhabi 2030.” Planning Theory & Practice 14 (2): 278–282. doi:10.1080/14649357.2013.793576.

- Nagy, S. 2008. “Dressing up Downtown: Urban Development and Government Public Image in Qatar.” City and Society 1 (12): 125–147. doi:10.1525/city.2000.12.1.125.

- Park, Y., and G. Rogers. 2014. “Neighborhood Planning Theory, Guidelines, and Research: Can Area, Population, and Boundary Guide Conceptual Framing?” Journal of Planning Literature 30 (1): 18–36. doi:10.1177/0885412214549422.

- Patricios, N. 2002. “Urban Design Principles of the Original Neighborhood Concepts.” Urban Morphology 6 (1): 21–32. https://works.bepress.com/nicholas_patricios/15/

- Perry, C. 1929. The Neighborhood Unit: From the Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs. Routledge/Thoemmes Press. ISBN 04-15160855.

- Rohe, W. 2009. “From Local to Global: One Hundred Years of Neighborhood Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 75 (2): 209–230. doi:10.1080/01944360902751077.

- Schoenberg, S., and P. Rosenbaum. 1980. Neighborhoods that Work. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-0901-7.

- Serag El Din, H., A. Shalaby, H. Farouh, and S. Elariane. 2013. “Principles of Urban Quality of Life for a Neighborhood.” Housing and Building National Research Center Journal 9: 86–92. doi:10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.02.007.

- Shandas, V., Y. Makido, and S. Ferwati. 2017. “Rapid Urban Growth and Land Use Patterns in Doha, Qatar: Opportunities for Sustainability.” European Journal of Sustainable Development Research 1 (2): 1–13. doi:10.20897/ejosdr/70093.

- Silver, C. 1985. “Neighborhood Planning in Historical Perspective.” Journal of the American Planning Association 51 (2): 161–174. doi:10.1080/01944368508976207.

- Skyscraper City. 2007. “Qatar in the past Century.” http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=433902&page=2

- Snoj, J. 2017. Population of Qatar by nationality. Priya DSouza Consultancy. http://priyadsouza.com/population-of-qatar-by-nationality-in-2017/

- Suttles, G. 1972. The Social Construction of Communities. University of Chicago Print. ISBN 9780226781891.

- UN Habitat. 2016. “Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures.” World Cities report 2016. ISBN: 978-92-1-133395-4. https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/WCR-%20Full-Report-2016.pdf

- Verburg, P., T. de Nijs, J. Eck, H. Visser, and K. Jong. 2004. “A Method to Analyze Neighborhood Characteristics of Land Use Patterns.” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 28 (6): 667–690. doi:10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2003.07.001.

- Wang, C. 1965. “An Evaluation of Perry’s Neighborhood Concept: A Case Study in the Renfrew Heights Area of Vancouver: A Thesis in Community and Regional Planning.” Master’s thesis, University of British Colombia, Vancouver, Canada. https://open.library.ubc.ca/media/download/pdf/831/1.0104825/1

- Wellman, B., and B. Leighton. 1979. “‘Networks, Neighborhoods, and Communities: Approaches to the Study of the Community Question.” Urban Affairs Quarterly 14 (3): 363–390. doi:10.1177/107808747901400305.

- White, J. 2015. “Future Directions in Urban Design as Public Policy: Reassessing Best Practice Principles for Design Review and Development Management.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (3): 325–348. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1031212.