ABSTRACT

The paper analyses placemaking in a small Finnish single-industry town through two architectural projects: the municipality’s downtown rejuvenation plan and the new visitor centre of a transnational corporation. It deploys Relph’s concept of placelessness interpreting it relationally with the concept of assemblage, and analyses how the two projects resonate with the place’s material and expressive elements. They represent high-quality architecture but embody placelessness: the visitor centre is physically detached from the town, and the downtown plan neglects industrial heritage. This is a missed opportunity for attractive place-making, and shows an urge for novel public-private collaboration in small town urban design.

Introduction

Small towns have undergone fundamental transformations in the past 20 years due to de-industrialization and negative demographic trends. In Northern Europe and North America, transformations in the forest industry throughout the last 20 years have sparked a major decline in mill-towns’ socio-economic performance (e.g., Halonen Citation2019; Halseth Citation2016; Conolly Citation2010). Because these challenges can threaten the entire existence of a community, shrinking towns are engaging in a variety of planning approaches to counteract decline and negative images (e.g., Conolly Citation2010). In many cases, the approaches include activities aimed at reinventing communities materially and symbolically with the help of revised town strategies, branding campaigns and urban design projects (Halseth and Ryser Citation2016; Martinez-Fernandez et al. Citation2016; Pallagst et al. Citation2017). While some efforts might be restricted to rhetorical attempts at creating a new image, others encompass large structural and strategic changes (Cleave et al. Citation2017; Albrecht and Kortelainen Citation2020).

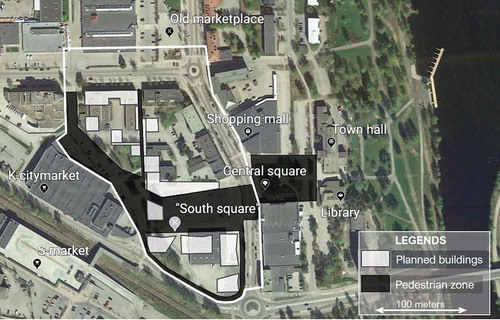

The case study focuses on urban design in Äänekoski, a small industrial town in Central Finland. The study assesses how two architectural projects relate and resonate with various elements of the place (). The role of urban planning and architecture in place-making has been studied predominantly in large cities and metropolitan contexts (Pallagst et al. Citation2017; Friedman Citation2018), yet it is important to focus on various sizes of human settlements because similar renewals are carried out in all kinds of urban localities (Friedman Citation2018). Both the local government and the owner company of the local mill have put extensive efforts on planning and architecture of new built environments as parts of their branding and image building work. First, this article studies how the municipality of Äänekoski utilizes the economic and publicity boom caused by a recent investment, the €1.2 billion bioproduct mill (BPM) by Metsä Group, to recode the place with help of downtown rejuvenation project as part of broader image-building process. Second, it scrutinizes ways how Äänekoski has become a focal point of company recoding by Metsä Group Corporation and how architecture contributes to this process. Focus is on Pro Nemus, a new visitor centre, which combines art, architecture and virtual experiences, and attracts thousands of visitors annually to Äänekoski.

Figure 1. Overview of Äänekoski and locations of the studied architectural projects (Background image: Google Earth)

The paper argues that Edward Relph’s (originally Citation1976) classic concepts of place-making and placelessness still provide means to analyse these processes. Relph’s work has been criticized as essentialist and anthropocentric, and that it ignores supralocal relations in place-making (see Seamon and Sowers Citation2008; Freestone and Liu Citation2016). Keeping these critiques in mind, the study approaches place and placenessness from a relational perspective deploying the assemblage concept (Woods Citation2016; DeLanda Citation2006). These concepts enable it to integrate a wide array of relational spatial processes such as matters of processuality and multiplicity within our analysis (Massey Citation2005; Cresswell Citation2015) and to remediate problematic aspects of Relph’s (Citation1976) original concept. It argues that in spite of extensive planning and branding efforts both projects provide the place with rather placeless solutions. This allows the paper to critically discuss both the town’s and company’s image-building attempts and argue that integrating Pro Nemus with the downtown rejuvenation project would have attenuated the placelessness of both projects.

Relational approach to place and placelessness

In Relph’s early works (e.g., Relph Citation1976), placelessness referred to a weakening identity of place due to the homogenizing processes of modernization. An important role was played by standardized planning associated with a lack of sensitivity to unique local characteristics and imitation of abstract models of urban design. Relph (Citation1976, 117) describes placelessness as a ubiquitous landscape, a flatscape or a meaningless pattern of buildings. In his more recent writings (e.g., Relph Citation2007, Citation2016), he smoothens his stance by stating that postmodernity has dismissed the placelessness of modernity and celebrates diversity instead of standardization. He argues, however, that placelessness still exists as detachment from the particularity of places and is manifest wherever human-planned landscapes have little connection with their geographical contexts.

Conceptually, placelessness still has analytical value for research on urban design. Echoing Dovey (Citation2016), the paper does not regard place and placelessness as binary opposites but more as intertwined qualities of the same thing. The two design and planning projects studied in this article aim at generating unique places. At the same time, however, they possess several placeless features because many of the potential ties to important ‘place-generating’ components are not achieved. The downtown rejuvenation project of Äänekoski is a future-oriented plan which aims to create a vibrant and attractive town centre for residents and commerce. It represents, however, rather typical urban design of our time without any symbolic nor material connection to the forest industry; the main source for various dimensions of local identity. The Pro Nemus visitor centre, instead, indicates a different sort of placelessness as it is physically and symbolically detached from the local community. Although Pro Nemus is located in Äänekoski and contributes to its identity through extensive publicity, it is located inside the closed mill gates and is accessible only for selected visitor groups.

The study aims to link placelessness and related concepts with a relational approach to place and study how the place-making efforts resonate with the elements and properties of the town. When translated to a more relational language, planning and design create placeless constructs when they separate the planned or constructed elements from some crucial identifiers of a place. For this purpose, it uses the assemblage approach to place, which provides a useful conceptual repertoire also for studying urban design and planning. Place’s material and expressive characteristics give it a form and identity, territorializing forces maintain its coherence, coding activities create meanings for it and relations of exteriority connect a place to the wider world (DeLanda Citation2006; Dovey Citation2010; Woods Citation2016; Cresswell Citation2015). This article emphasizes three of the above-mentioned aspects of assemblage conceptualization: coding and material as well as expressive components.

A place’s meaning and identity are affected by coding which is mediated through means of expressive media such as urban design and architecture, for instance. The related concept of decoding has the opposite effect and refers to representations which challenge established meanings in media or other means of communication (Woods Citation2016). Simultaneously with decoding, recoding takes place as new and alternative images of a place’s components are constructed. The local bioeconomy turn and accompanying projects of downtown rejuvenation and the visitor centre development provide illuminating examples of such recoding and the role of material/expressive components for place making.

Planning and design are not only works of art on paper or in virtual worlds, they have to resonate with their local contexts in numerous ways. They always possess various degrees of a sense of place, which in Relph’s terminology does not mean a property of a place but the ‘ability to grasp and appreciate distinctive qualities of places’ (Relph Citation2007, 19). This sensibility can be approached by studying how the planned elements of place (i.e., the downtown project and Pro Nemus) relate to components that have material and expressive roles in the specific identity of a place. The tangible material features of a place are embedded in the natural and built environments, infrastructure, technologies as well as in living beings. Expressivity refers to the essence of elements which arouse emotions and sensations. The identity of each mill town is created by a hybrid mixture of people, buildings, infrastructure, moving objects, natural environment and numerous other elements which are both typical for industrial towns and specific to a particular place. In addition to their material roles, the same elements possess expressive properties that can express themselves differently depending on an observer and situation. For instance, silhouettes of high smokestacks can express themselves as an iconic industrial landscape in one context and as a sign of air pollution in another.

Context of the case study

Until the 1990s, Äänekoski was a rather successful industrial community which had grown around an expanding complex of forest industry production (cardboard mill, pulp mill, paper mill & sawmill) since the end of the 19th century. The local economy changed drastically when Nokia started to develop and produce mobile phones in Äänekoski in the early 1990s, which meant a significant change in the image of the town. The population grew to over 21 000 inhabitants, and the traditional mill town was increasingly perceived as an information age hub. The ICT boom was short lived, however, and Nokia withdrew all its operations from Äänekoski in the beginning of 2000s which resulted in the loss of almost 1000 jobs locally. Also, the Äänekoski paper mill was abolished in 2011 and its 200 jobs disappeared from the town, further speeding up decline. The population of Äänekoski dropped to 18668 by June 2020 (Tilastokeskus Citation2020). Within a few years the image of Äänekoski quickly shifted from an information age growth centre to a shrinking town with all the adjunct material and expressive attributes (Albrecht and Kortelainen Citation2020) including unemployment, outmigration, decreasing tax revenues, emptying commercial spaces and deteriorating street networks (e.g., Äänekoski Citation2015).

The image of Äänekoski started to change in 2014 when Metsä Group decided to build a new generation pulp mill, the so-called Äänekoski bioproduct mill (BPM) which became a widely hyped flagship of the national economic policy and emerging bioeconomy. Metsä Group, a huge Finnish forestry corporation (annual sales c. €5.5 billion and over 9 200 employees), is the majority owner of the Äänekoski mill. The new BPM started operation in 2017 and almost tripled production capacity of the old mill to 1.3 M metric tons annually. The plan was to establish a local bio-production ‘ecosystem’ consisting of innovative companies that would utilize the underutilized side-streams (formerly waste) of pulp production. Yet, the development of new product innovations and investments at the BPM site has been modest up to now (2020), and the decline of local jobs and population has continued (see Albrecht and Kortelainen Citation2020).

The analysis below rests on a mix of qualitative and quantitative data consisting of 14 face-to-face interviews, document analysis, socio-economic statistical data sets and ethnographic observations generated between April 2017 and May 2019. Interviews were conducted with experts from industry, regional and local administrations, local companies and NGOs. Moreover, a questionnaire survey was carried out among young residents of the town. Development and planning documents, town marketing brochures, company bulletins, newspapers, history books, etc. have been utilized in this research (see also Albrecht Citation2019; Albrecht and Kortelainen Citation2020 for details). The integration of multiple data sources, formats and partially competing knowledge claims enables the integration of the processuality and multiplicity of assembling processes which are key to evaluating place-making (Baker and McGuirk Citation2017; Woods Citation2016).

Planning for place branding: town centre rejuvenation

Ageing infrastructure is a typical feature in most restructuring single-industry towns, and especially evident deterioration occurs in obsolescing downtown areas. Local governments of small towns have put special emphasis on core rejuvenation as way to revitalize local economies and attract tourists, new residents and businesses (see Hayter and Nieweler Citation2018; Friedman Citation2018). The municipality of Äänekoski made two major urban planning efforts immediately after the BPM decision. First, it ordered a plan to rejuvenate the town centre. Second, a plan was made to build a new residential area in the vicinity of the centre. The purpose of the latter is to utilize the national government’s investment in a new motor way and hopes for a restart of passenger train transport. It aims to attract new residents from the city region of Jyväskylä (c. 40 km away) by generating alluring housing environments for bioeconomy start-up entrepreneurs. In this paper, however, the focus is on the downtown renewal plan.

The downtown area of Äänekoski began to take shape in the early 20th century spontaneously when industrial workers built their homes and commercial services concentrated there. The first town plan was made in the 1930s and it did not make any radical changes to the freely developed milieu with wooden buildings. As typical during the 1960s and 70s, the old wooden milieu was completely replaced by more placeless forms of architecture and infrastructure, such as taller concrete buildings, wider streets for cars, and supermarkets with parking lots (Mustonen and Saarilahti Citation2014). Later, the downtown area of Äänekoski was enlarged and supplemented by buildings for public and private services throughout the town’s growth period. When the local economy began to decline at the turn of the century, empty commercial buildings, deteriorated streets and overall shabbiness started to characterize the built environment. This strengthened the shrinking city identity of Äänekoski in the 2000s and early 2010s.

There were plans to rejuvenate and restructure the downtown area already in the early 2000s (Äänekoski Citation2012) but the poor financial situation forced the local government to postpone them. The BPM and especially its construction phase from 2015 to 2017 significantly improved the municipal economy through increased tax revenue and state support, which enabled the local government to carry out a wide array of material changes to improve the appearance and functionality of Äänekoski’s town centre. The road network was renewed mainly due to the needs of the BPM’s wood supply by truck transport. The deteriorated streets were repaired and paths for bikes and pedestrians were constructed. Town development efforts included the demolition of some of old communal housing buildings and planning new high-quality residential areas (Äänekoski Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The improved local economy allowed the local government to carry out extensive leisure infrastructures projects, such as the construction of modern sports facilities and significant investments in downtown parks (Äänekoski Citation2017b).

The town and regional development company ordered a new plan for renewal of the town centre just after the decision concerning the BPM was made (). In addition to material and functional improvements, the local government’s aim was to generate an expressive image of an alluring, vibrant and forward-looking place in order to get rid of the place identity as a shrinking problem area. The more practical goal of ‘Reshaping the core centre of Äänekoski’ -rejuvenation plan was to develop the downtown as an active and inspiring node for encounters, housing, commerce and commuting. The starting point was a then recent development of two large retail centres which had been built outside of the core and moved the functional town centre southwards. Commercial services were fleeing the former core and the main street was becoming a route for passage traffic and a parking lot. The town council formulated the goal in a following way:

The goal is to plan an architecturally high quality, interesting and pedestrianised town centre which is accessible by all means of transportation. (Kaupunginhallitus Citation2015)

The rejuvenation plan was prepared by an international consulting agency and a Helsinki-based architecture firm, in close cooperation with managers, planning authorities and the development company of the municipality. Open workshops were organized, and approximately 30 local residents attended them in addition to representatives from the municipality and planning agencies. Feedback was given on the five alternative plans in the workshops and through solicited statements from several local entities and organizations.

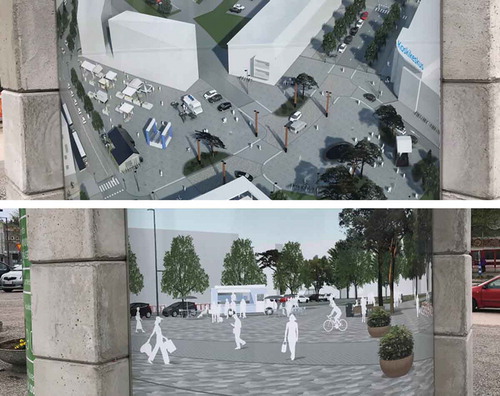

The selected alternative, ‘Etelätori’ (South-square), was based on the idea to move the market square from the northern part of the downtown area a few hundred metres south, close to the new retail centres. One and two-storey commercial buildings () were to be demolished to be replaced by higher buildings for housing and commerce. It was not named as a market square but a multi-purpose square in order to emphasize it as a site for various events and characterized as a ‘common public living room’ framed by cafes and restaurants. Large pedestrian zones connect the square to previously built parks and public facilities () (Äänekoski Citation2012, Citation2017c; Kaupunginhallitus Citation2015). As shows, most of the old buildings have been demolished, and construction of the new square’s surroundings was begun in summer 2019 (Äänekoski Citation2019b).

Figure 3. The site of the future ‘South square’ before the rejuvenation project (2009). (Photo: Google Streetview)

What is striking in this plan is the absence of both the industrial characteristics of the town and the concept of bioeconomy. Although the town was living a bioeconomy boom at that time and strongly emphasizing innovative bioproduction systems in its strategies, these aspects were completely lacking in the downtown plan. It is also difficult to find any reference to the industrial characteristics of a mill town. Finnish words such as ‘tehdas’ (mill/factory), ‘teollisuus’ (industry) or ‘biotalous’ (bioeconomy) are absent from the plan. A hint to the historical identity is given by one minor sentence promoting wood as a suitable construction material because of the towns’ history. Nonetheless, local government is planning to develop industrial tourism and an exhibition for all local bioeconomy producers:

… there is a need for such a space that we could bring all our actors [bioeconomy producers] to present their messages. (Interviewee I)

Yet, these considerations are not integrated in the downtown rejuvenation plan which gives the impression that industry has been purposely left out from the placemaking of the town centre. The illustrations of the multi-purpose square in the plan and information board at the new square’s construction site () are very indicative of this. There are no indications at all that the visual presentations represent the centre of a mill town. If you walk through Äänekoski, however, it is very difficult to miss the mill and industry because the massive constructions, smokestacks and wood-truck traffic dominate the scenery and soundscape.

This indicates a problem of dual objectives in town development strategies and branding. While innovative industry and business are highlighted to attract bioeconomy investments and experts; simultaneously, the town tries to draw new residents working in and commuting to the nearby Jyväskylä city region. An industrial image is not the most alluring for potential new residents who do not work in local industrial jobs as stated by a local politician:

Our problem is that we are not a very attractive living place for people […] because our image is that we are a mill town. Already in the 1990s there was a problem of how to get people here. At that time, we had Nokia here […] we did not have any cure for this. (Interviewee II)

The local government tries to solve the dilemma with a kind of ‘double-edged sword’ -strategy and base branding on two pillars, creating a vision of a pleasant and modern living environment and developing an image of a new kind of innovative and responsible industrial hub. It has produced separate town advertisement leaflets for these two purposes (Äänekoski Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The rejuvenation plan of the town centre is obviously meant to support the former strategic goal. It aims to develop a lively and trendy inner-city commercial centre that would attract urban dwellers and youth. At the same time, the plan creates an image of a rather ordinary future townscape without any reference to the industrial heritage or genius loci of the place. This makes the future inner-city visions rather placeless.

In contrast to optimistic expectations, the huge investment has not brought significant growth in jobs, and constant unemployment and outmigration continue. This also affects town finances and makes the completion of the downtown rejuvenation plan uncertain (Äänekoski Citation2019a). The planned and constructed renewals in the townscape seem to have very limited effects on youth outmigration. The survey among young people in Äänekoski showed that the urban planning and development measures do not convince local youth to stay in town. Almost half of the respondents indicated that the recent changes in local environment are positive, but merely 15% of them are planning to stay there in the future.

Additionally, the open-ended questions in the survey showed that the general perspective among young people remains locked into the rather unattractive industrial features of the mill town, especially bad odours and extensive traffic loads. In principle, these are old features in a forest industry town, but the BPM has revitalized many of these elements. The 200% growth of heavy load truck traffic next to downtown raises negative expressive features concerning safety, noise and particle pollution, countering the image of a fancy and clean town centre portrayed in the plans. Another challenging expressive feature stems from the odours of the mill and biogas station. The new BPM was advertised as stopping the unpleasant smell of pulp processing, yet it continues to cause problems, which are highlighted in the survey, local media, online forums and town council meetings (see also Äänekoski Citation2020).

The visual industrial image of the BPM is easy to ignore, unpleasant odours, even though only punctual and temporary, entail the capacity to jeopardize much of the efforts in upgrading the town’s image. It also shows that it is possible to ignore the industrial characteristics of a place at the architect’s desk, but you cannot escape them on the ground. News, stories and social media discussions about traffic and odorous disturbances erode the solid and clean picture portrayed in the downtown plan and other current recoding efforts. Hence, proactive integration of industrial heritage and current industrial developments into the downtown development could have been beneficial, and there was even a window of (missed) opportunity when Metsä Group announced that it was building the ProNemus visitor centre in 2016.

Branding through a building: Pro Nemus

Echoing the inauguration speech of the BPM by Finnish President Sauli Niinistö, the Finnish media named the Äänekoski BPM the ‘new pride’ of the Finnish forest industry (Helsingin Sanomat Citation2017). The forest-based bioeconomy had just been promoted by the government and industrialists as a solution to rejuvenate the struggling Finnish economy, and then prime minister Juha Sipilä grandiosely called it ‘a new Nokia’ (Keskisuomalainen Citation2015). This political strategy and its supporting schemes encouraged industry to prepare a wide array of new investment plans, particularly large biorefinery plans. However, the Äänekoski BPM is the only big investment that has materialized as of autumn 2020. It has gained much national and international publicity, positioned Metsä Group as front-runner in bioeconomy transformations and has given hope for other declining mill towns in Finland. The bioeconomy boom started to affect some industrial towns’ identities, and had an especially strong influence in Äänekoski as the locus of Metsä Group’s bioeconomy recoding activities. The fact that the BPM was located there started to change the image of the town. Äänekoski was in the spotlight, and the BPM was widely presented as an example of bioeconomy transition in daily news, policy reports and events at the national and EU levels (Albrecht Citation2019; Peltomaa Citation2018).

As the BPM represented the new image of sustainable bioeconomy development for the company, Äänekoski was selected as the showcase of the operations and recoding of the whole corporation. For this purpose, Metsä Group opened the Pro Nemus (‘for forests’) visitor centre at the BPM in 2018. Its aim is to present the corporation’s over 20 production units and the production system from harvesting to wood and paper products. The centre combines wood architecture, artwork, virtual media and guided presentations, and targets various stakeholder groups from foreign clients to the local population. It has no role in material production but acts as an important knowledge producer and expressive media for the whole company. It provides a mix of selective material and expressive features that represent the BPM approach as a frontrunner of bioeconomy development.

Pro Nemus is a 1000 m2 building designed and constructed from 2016 to 2018 (Metsä Group Citation2018). The building itself is rather small and ‘invisible’ compared to the massive industrial constructions surrounding it, but it stands out from other buildings because of its architectural image (). The architects’ commission and vision was to design a building constructed of wood materials produced by the company. Light-coloured wood materials dominate the interior of Pro Nemus, which contrasts to the dark exterior of the building (). The material composition as well as the expressive essence of the building itself is centred around the idea to give visitors a concrete and tangible experience which enables them to see, touch and even smell Metsä Group’s products. As the main planner of the building, states on its web site:

The building itself and its exhibitions show how Finnish wood is converted into different products. Structures of the building and other wood materials are Metsä Group’s products and the aim was that they are shown and can also be felt as authentic as possible. (UKI Arkkitehdit Citation2020)

The experiential character of the exhibition centre was designed and materialized in co-operation with several actors. A company concentrating on experiential branding was responsible for the exhibition concept and designed the walkthrough, ‘experiential journey’ in the building with touch points and story-telling functions. The virtual experience and related digital contents were produced by programming companies specialized in experimental digital design. The walkthrough consists of interactive points with touchscreens, virtual reality headsets and other interactive devices, which aim to create the feeling of authentic experiences and simultaneously provide knowledge about the company’s operations. The experience is completed by human guidance and assistance by professional guides who can serve visitors in several languages. In its entirety, Pro Nemus succeeds in both creating an impressive experience and providing a broad but – as shown below – highly selective information package which supports the brand and promotes the image of an environmentally responsible company. Ilkka Hämälä, CEO of Metsä Group states that:

The world needs responsibly produced renewable materials. Metsä Group wants to be increasingly active in the development of forest-related operations and forest use. The visitor centre allows us to demonstrate how this happens (Metsä Group Citation2018).

Pro Nemus is a constructed place, an assemblage which combines carefully selected material and expressive elements with digital techniques and human-computer interaction and manifests in the form of a wooden building. It relies on relations of exteriority as it brings the entire corporation within the building in the form of tangible encounters, narratives and virtual knowledge. The visitor centre aims to create a sense of place which would give the visitor an impression of a responsible actor and innovative frontrunner. According to the visitor surveys, it has succeeded in this task too. However, it must be remembered that a great majority of the visitors are stakeholders of the company (customers, forest owners, local citizens etc.) who typically have a positive preconception of the forest industry.

Pro Nemus has received several nominations and international prizes for its architecture, exhibition design and content as well as wood material usage (Metsä Group Citation2019). Although it is an impressive construction, its attempts to create a positive expressive picture of Metsä Group are challenged by several uncontrollable features and processes. One of the most important stems from relations of exteriority, i.e., from the growing international and national criticism of the resource exploitation focus and export market orientation of forest-based bioeconomy. The extensive biomass needs of the Äänekoski BPM and planned future mills have caused a lot of critical discussion (e.g., Helsingin Sanomat Citation2017). Researchers, political bodies and foresters have debated over the annual cutting potentials and threshold levels that Finnish forests can sustain while acting as a carbon sink. These discussions strongly challenge the assumptions and message Pro Nemus was planned for and built on. Although the visitor centre aims to give the impression of an open and transparent source of information, these critical discussions are lacking from the exhibition.

Pro Nemus is designed purely to support the company brand, but it also contributes to the image of the entire town as a bioeconomy hot spot. It is a place within a place and thus has a role in both the company’s and the local government’s attempts to brand themselves as bioeconomy frontrunners. Its material presence in Äänekoski forms an expressive element that links and characterizes the locality with positive bioeconomy rhetoric. Pro Nemus has had over 15 000 visitors (as of March 2020) from various parts of the country and abroad, which has also increased recognition of the town. For instance, a trip to the Äänekoski BPM and Pro Nemus was part of a large international bioeconomy conference initiated by the Finnish presidency to the EU in Helsinki in 2019.

When examined more closely, it is easy to recognize that the relationship between Pro Nemus and Äänekoski is characterized more strongly by separation than integration, and thus the influence of the identity of place is indirect and superficial. This was highlighted by another industrial stakeholder operating in Äänekoski:

because it’s little bit remote, and then it is pity that the centre [Pro Nemus] is in the middle of the factory, which is not good for the tourists […]. The buses from Helsinki that bring them in, that’s okay. But, we think we should combine the town museum here and more towards the center. (Interviewee III).

Location of Pro Nemus within the fenced mill site and between huge industrial buildings makes Pro Nemus invisible and detached from the everyday environment of local people. The centre aims to show the entire commodity chain and gather information from the entire company’s production sites. Äänekoski plays only a minor role in this assemblage. This impression is strengthened by the fact that the centre is open predominantly for select stakeholder groups from elsewhere. A limited number of local residents can apply to visit Pro Nemus for two hours once a month. Instead of making the visitor centre a public (or semi-public) space and building it somewhere within the townscape, the company has continued its tendency to withdraw behind the mill gates. As one of the interviewees said:

It´s kind of a town in the town they are more closed than the earlier factory was. (Interviewee II)

Concluding discussion

The studied projects represent high-quality planning and seemingly fulfil the expectations of their clients and many stakeholders. The rejuvenation plan of Äänekoski’s downtown follows many guidelines for urban design offered by current international planning literature. Äänekoski’s multipurpose square surrounded by cafés, commercial spaces, parks and public services is characterized as a ‘common living room’. Friedman (Citation2018), for instance, emphasizes the importance of ‘communal living rooms’ in small towns. They are often conceptualized as third places which, in contrast to routines and schedules of first and second places (home and work), are sites for more spontaneous socializing and relaxation (Oldenburg and Brissett Citation1982). ‘Shared space’ is another concept guiding the downtown plan. New ways of organizing urban space and breaking the conventional segregation between traffic and civic space have become common approaches in contemporary urban design internationally and also in Finland (e.g., Hamilton-Baillie Citation2008). In Äänekoski, traffic arrangements around the new square aim to create a shared space by mixing street traffic and pedestrian zones together.

Pro Nemus is a pioneering project as an experiential and interactive visitor centre for industry. Such aspects have been highlighted in human-computer interaction (HCI) research, which focuses on human interactions and practices with and around digital technologies. Museums and cultural heritage sites have been early adopters of these kinds of interactive technologies. In HCI literature the concepts of place and place-making have been deployed in order to grasp how combinations of digital technologies and tangible elements shape and mediate experiences of cultural heritage (Ciolfi and McLoughlin Citation2018).

However, when analysed through more critical lenses it becomes evident that both projects have a similar problem. They provide a highly selective and favourable picture of their core contents, and in doing so, they detach themselves from many crucial relations with material and expressive identifiers of the place. As stated above, relationally interpreted planning is placeless when it separates the planned or constructed elements from some crucial material and expressive identifiers or relations of exteriority which characterize a particular place assemblage (cf. Relph Citation2007; Dovey Citation2010). Pro Nemus is portrayed as experiential stage providing a transparent and comprehensive picture of the company. However, some of its crucial relations of exteriority are cut off as it is located within the mill area, access to it is strictly controlled and critical voices ignored. The rejuvenation plan of downtown Äänekoski aims to create an attractive, vibrant and innovative town centre. Nevertheless, it disengages the town from its material and expressive identifiers by turning its back to both its industrial past and present bioeconomy developments. This makes the planned place similar to numerous other parallel downtown projects without any indication of a specific and possibly positive or forward-looking industrial spirit of place.

These results indicate that there is a missed urban design opportunity which would have, it can be argued, supported the company’s branding as well as highlighted the identity of place as a ‘new-generation’ mill town. Physical integration of the visitor centre in the downtown rejuvenation would have had many positive effects on both the town and the company. Locating Pro Nemus downtown and a more open visitor policy would have created more visibility for the company and supported its attempts to create an image of a transparent and reliable actor. Moreover, it would have been a means to liven up the downtown area, support the ‘common living room’ (third place) idea and boost local small businesses because the visitor centre would have attracted a large number of tourists and other visitors to the town centre. Finally, locating Pro Nemus downtown would have been a way to avoid the placelessness of both the visitor centre and the planned townscape. Instead of being separated from the rest of town, Pro Nemus would have been an incorporated part of the downtown area. It would also have brought an architectural marker of the industrial identity of the place to the middle of the town. Although this is a missed opportunity in Äänekoski, it could be possible to utilize the lessons learned to argue for more place-based collaborative urban design projects in other industrial towns. At the moment, large number of small towns in Finland and elsewhere are carrying out potentially placeless downtown rejuvenation projects. It would be crucial to gain a more in-depth understanding of the drivers and consequences of such placeless urban design.

This kind of placelessness is more general in mill towns’ strategies and planning because most of them tend to deliberately forget and hide their industrial character (Cleave et al. Citation2017) Companies, instead, have strived for becoming placeless by cutting systematically their ties to the surrounding localities and retreating more tightly behind their mill gates. In the past, industrial companies were major urban developers, hiring leading architects to design the townscapes of mill towns which created, at its best, pathbreaking architecture and town planning (e.g., Chapman and Roberts Citation2014). The findings above suggest, however, that there is an unused potential for new kinds of collaborative public-private urban design projects in industrial towns. Novel collaborative urban design would provide towns and companies with synergies in Äänekoski and elsewhere. These projects could integrate visitor centres or industrial museums with downtowns and utilize wood materials and the companies’ products in their construction. This, particularly in times when green economic strategies (e.g., circular- & bio-economy) are proposed as societal transformation pathways that require active citizen engagement. They could support the companies’ branding, liven up the town centres, attract tourists and also bring an inclusive industrial spirit of place back to the towns. However, such collaboration naturally requires long-term commitment from companies to distinct localities, which does not seem to be a given feature of current corporate governance despite the many social responsibility guidelines and statements.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Äänekoski. 2012. Äänekosken Keskustan Kehittäminen 2010 – 2050. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2015. Äänekosken Kaupunkistrategia. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2017a. Elinvoimaa rakentmisesta: Äänekosken kaupungin kaupunkirakenneohjelma 2017 – 2021. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2017b. Äänekosken kaupunki Tilinpäätös tilikaudelta 1. 1.- 31.12.2016. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2017c. Uudistuvan ydinkeskustan asemakaava I: kaavaselostus. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2018a. Tulevaisuus asuu täällä. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2018b. Hyvä arki asuu täällä. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2019a. Kestävä kehitys. Accessed 12 February 2020. https://www.aanekoski.fi/asuminen-ja-ymparisto/kestavakehitys

- Äänekoski. 2019b. Talousarvio 2020: Taloussuunnitelma 2020 – 2022. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Äänekoski. 2020. Äänekosken Ilmanlaatu Vuonna 2019. Äänekoski: Äänekosken Kaupunki.

- Agnew, J. 2011. “Space and Place.” In The SAGE Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, edited by J. A. Agnew and D. N. Livingstone, 316–331. London: SAGE.

- Albrecht, M. 2019. “(Re-)producing Bioassemblages: Positionalities of Regional Bioeconomy Development in Finland.” Local Environment 24 (4): 342–357. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1567482.

- Albrecht, M., and J. Kortelainen. 2020. “Recoding of an Industrial Town: Bioeconomy Hype as a Cure from Decline?” European Planning Studies 29 (3): 1–18. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1804532.

- Baker, T., and P. McGuirk. 2017. “Assemblage Thinking as Methodology: Commitments and Practices for critical Policy Research.” Territory, Politics, Governance 5 (4): 425–442. doi:10.1080/21622671.2016.1231631.

- Chapman, M., and J. Roberts. 2014. “Industrial Organisms: Sigfried Giedion and the Humanisation of Industry in Alvar Aalto’s Sunila Factory Plant.” Fabrications: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 24 (1): 72–91. doi:10.1080/10331867.2014.901137.

- Ciolfi, L., ., and M. McLoughlin. 2018. “Supporting Place-specific Interaction through a Physical/digital Assembly.” Human–Computer Interaction 33 (5–6): 499–543. doi:10.1080/07370024.2017.1399061.

- Cleave, E., G. Arku, R. Sadler, and J. Gilliland. 2016. “The Role of Place Branding in Local and Regional Economic Development: Bridging the Gap between Policy and Practicality.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 3 (1): 207–228. doi:10.1080/21681376.2016.1163506.

- Cleave, E., G. Arku, R. Sadler, and J. Gilliland. 2017. “Is It Sound Policy or Fast Policy? Practitioners’ Perspectives on the Role of Place Branding in Local Economic Development.” Urban Geography 38 (8): 1133–1157. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1191793.

- Conolly, J. J., ed. 2010. After the Factory: Reinventing America’s Industrial Small Cities. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Cresswell, T. 2015. Place: An Introduction. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons.

- DeLanda, M. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum.

- Dovey, K. 2010. Becoming Places: Urbanism/architecture/identity/power. Oxon: Routledge.

- Dovey, K. 2016. “Place as Multiplicity.” In Place and Placelessness Revisited, edited by R. Freestone and E. Liu, 257–268. London: Routledge.

- EC. 2018. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment – An Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. Brussels: European Commission.

- ELY. 2020. Keski-Suomi työllisyyskatsaus: Joulukuu 2019. Jyväskylä: ELY.

- Freestone, R., and E. Liu. 2016. “Revisiting Place and Placelessness.” In Place and Placelessness Revisited, edited by R. Freestone and E. Liu, 1–19. London: Routledge.

- Friedman, A. 2018. Fundamentals of Sustainable Urban Renewal in Small and Mid-Sized Towns. Cham: Springer.

- Halonen, M. 2019. “Booming, Busting - Turning, Surviving?: Socio-economic Evolution and Resilience of a Forested Resource Periphery in Finland.” Publications of the University of Eastern Finland. Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies, No 205. Joensuu: UEF.

- Halseth, G. 2016. Transformation of Resource Towns and Peripheries: Political Economy Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Halseth, G., and L. Ryser. 2016. “Rapid Change in Small Towns: When Social Capital Collides with Political/bureaucratic Inertia.” Community Development 47 (1): 106–121. doi:10.1080/15575330.2015.1105271.

- Hamilton-Baillie, B. 2008. “Shared Space: Reconciling People, Places and Traffic.” Built Environment 34 (2): 161–181. doi:10.2148/benv.34.2.161

- Hayter, R., and S. Nieweler. 2018. “The Local Planning-economic Development Nexus in Transitioning Resource-industry Towns: Reflections (Mainly) from British Columbia.” Journal of Rural Studies 60: 82–92. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.006.

- Helsingin Sanomat. 2017. Äänekoskella vihittiin Suomen metsäteollisuuden uusi ylpeys: 12 Eduskuntatalon kokoinen sellutehdas. Accessed 12 February 2020. https://www.hs.fi/talous/art-2000005413759.html

- Kaupunginhallitus. 2015. “Uudistuva Äänekosken ydinkeskusta.” Kaupunginhallitus 23.11.2015 liite nro 3 (2/23). https://www.aanekoski.fi/asuminen-ja-ymparisto/kaavoitus/kaavat/kaavat-aakkosjarjestyksessa/Uudistuva_ydinkeskusta_2015_Raportti.pdf

- Keskisuomalainen. 2015. “Juha Sipilä: ”Äänekoski on uuden Nokian Alku”.” Keskisuomalainen 22 (3): 2015. https://www.ksml.fi/kotimaa/Juha-Sipil%C3%A4-%C3%84%C3%A4nekoski-uuden-Nokian-alku/352777

- Martinez-Fernandez, C., T. Weyman, S. Fol, I. Audirac, E. Cunningham-Sabot, T. Wiechmann, and H. Yahagi. 2016. “Shrinking Cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a Global Process to Local Policy Responses.” Progress in Planning 105: 1–48. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2014.10.001.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

- Metsä Group. 2018. “Pro Nemus Visitor Centre Is a Completely New Kind of Forest Experience.” Accessed 2 April 2020. https://www.metsagroup.com/en/media/Pages/CASE-Pro-Nemus-visitor-centre-is-a-completely-new-kind-of-forest-experience.aspx

- Metsä Group. 2019. “International Recognition for Metsä Group´s Pro Nemus Visitor Centre.” Accessed 1 September 2020. https://news.cision.com/metsaliitto-osuuskunta/r/international-recognition-for-metsa-group-s-pro-nemus-visitor-centre,c2995031

- Mustonen, A., and S. Saarilahti. 2014. Äänekosken seutukunta. Äänekosken keskusta-alue, Suolahti, Sumiaianen ja Konginkangas: Keski-Suomen modernin rakennusperinnön inventointihanke 2012–2014. Jyväskylä: Keski-Suomen Museo.

- Oldenburg, R., and D. Brissett. 1982. “The Third Place.” Qualitative Sociology 5 (4): 265–284. doi:10.1007/BF00986754.

- Pallagst, K., H. Mulligan, E. Cunningham-Sabot, and S. Fol. 2017. “The Shrinking City Awakens: Perceptions and Strategies on the Way to Revitalisation?” Town Planning Review 88 (1): 9–13. doi:10.3828/tpr.2017.1.

- Peltomaa, J. 2018. “Drumming the Barrels of Hope? Bioeconomy Narratives in the Media.” Sustainability 10 (11): 4278. doi:10.3390/su10114278.

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion.

- Relph, E. 2007. “Spirit of Place and Sense of Place in Virtual Realities.” Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology 10 (3): 17–25.

- Relph, E. 2016. “The Paradox of Place and the Evolution of Placelessness.” In Place and Placelessness Revisited, edited by R. Freestone and E. Liu, 20–34. London: Routledge.

- Seamon, D., and J. Sowers. 2008. “Place and Placelessness (1976): Edward Relph.” In Key Texts in Human Geography, edited by P. Hubbard, R. Kitching, and G. Valentine, 43–52. London: Sage.

- Sisä-Suomen Lehti. 2019. “”Äänekoskella edessä tuikemmat taloudelliset vuodet” – lue kaupunjohtaja uudenvuoden puhe.” Accessed 12 February 2020. https://www.ksml.fi/sisis/%C3%84%C3%A4nekoskella-edess%C3%A4-tiukemmat-taloudelliset-vuodet-lue-kaupunjohtajan-uudenvuoden-puhe/1488650

- Tilastokeskus. 2020. “Tilastokeskuksen PxWeb-tietokannat.” Accessed 1 September 2020. http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vamuu/statfin_vamuu_pxt_11lj.px/table/tableViewLayout1/

- UKI Arkkitehdit. 2020. “Pro Nemus Exhibition Centre Inaugurated in Äänekoski. Web Site of an Architect Studio.” Accessed 5 March 2020. https://ukiark.fi/en/pro-nemus-exhibition-centre-inaugurated-in-aanekoski/

- Woods, M. 2016. “Territorialisation and the Assemblage of Rural Place: Examples from Canada and New Zealand.” In Cultural Sustainability and Regional Development: Theories and Practices of Territorialism, edited by J. Dessein, E. Battaglini, and L. Horlings, 29–42. Abingdon: Routledge.