ABSTRACT

This paper introduces a novel approach to evaluating urban open spaces (UOS) by developing a mobile application, YouWalk-UOS. Overcoming current limitations and the need for integrating digital technologies and participatory methods into UOS assessment processes, the study establishes a comprehensive framework addressing functional, social, and perceptual dimensions with 36 identified aspects. The framework and the mobile application are tested at Grey’s Monument in Newcastle, England, revealing its potential to capture a thorough perspective of UOS. The findings suggest that mobile technology can revolutionize urban space assessment, emphasizing the value of user-contributed data for various stakeholders, including designers, educators, and policymakers.

Introduction

In the evolving landscape of urban design and planning, assessing urban open spaces (UOS) – encompassing parks, plazas, greenways, and other communal areas – is essential to creating sustainable and vibrant communities. Recognizing the multifaceted nature of these spaces, this study advocates for an integrative approach that accounts for functional, social, and perceptual dimensions, a shift that aligns with the current trajectory towards adaptive and inclusive urban environments. The need for this paradigmatic shift arises from the limitations of traditional UOS assessment methods, which tend to focus primarily on physical aspects, often neglecting the complex interplay of social, ecological, and aesthetic elements that contribute to the vitality of these environments.

Building on this premise, the paper emphasizes the significance of co-assessment methods (Sutherland, Shackelford, and Christian Rose Citation2017) in UOS evaluation. Co-assessment incorporates direct user participation, allowing a more comprehensive understanding of urban spaces beyond physical measurements. This method recognizes the importance of user experiences and perceptions in understanding and reacting to the qualities of urban spaces while promoting more responsive, inclusive, and user-friendly approaches in urban space assessment. The integration of co-assessment methods responds to the growing demand for urban spaces that meet physical requirements and enhance the quality of life for their users.

Transitioning from the theoretical underpinnings to the practical application, the study addresses the gap left by traditional methods, such as physical measurements and observational studies, which may not fully encapsulate users’ experiences in and perceptions of UOS (Gehl and Gemzøe Citation1996; Whyte Citation1980), while revealing what is already evident. Despite the acknowledged importance of UOS (Cozens Citation2008; Talen Citation2022), prior research has paid little attention to methods involving direct user participation. This article addresses this gap using a participatory approach, employing the YouWalk-UOS mobile application for a comprehensive evaluation of UOS. This methodology is fundamental for understanding how users develop judgements about the environments they experience and eventually for developing responsive, inclusive, and user-friendly UOS. The study aims to assess UOS through a multi-dimensional lens – functional, social, and perceptual – utilizing the YouWalk-UOS mobile application. Specifically, it seeks to achieve two objectives: a) utilize the YouWalk-UOS app for assessing UOS in terms of their functional, social, and perceptual aspects, and b) to validate the operational capabilities of the YouWalk-UOS mobile application in real world setting.

Bridging the gap in traditional UOS assessment methods by leveraging the innovative capabilities of the YouWalk-UOS mobile application, this study brings a new perspective and marks a significant stride in integrating technology with participatory urban assessment. By enabling users to actively participate in the assessment process, the study captures a holistic view of UOS that encompasses not just the physical attributes but also the social dynamics and personal perceptions that define these spaces. The findings of this endeavour would offer valuable insights for urban designers, planners, and policymakers, demonstrating how the integration of mobile technology can enhance our understanding, management, and improvement of UOS.

Examining the existing discourse on UOS assessment

The appraisal of the literature aims to examine existing scholarly works related to UOS to grasp their multifaceted qualities, encompassing their perceptual, social, and aesthetic functions within urban settings. A second line of inquiry is to explore the evolving role of mobile applications in urban design and planning, highlighting how technological advancements are reshaping the way in which urban spaces are analysed and understood.

Theoretical underpinnings of urban open space assessment

UOS are central to modern urban planning, reflecting a complex relationship between ecological sustainability, social interaction, and aesthetic value. The significance of conceptual and methodologically sound indicators for assessing the performance of UOS is highlighted by Verma and Raghubanshi (Citation2018) and further supported by the works of Wang and Foley (Citation2021), illustrating the need for robust frameworks in the face of rapid urbanization and environmental challenges (Friedman Citation2021; Mees Citation2021).

Historical evolution and key concepts in urban open space assessment have been shaped by seminal thinkers and the frameworks they have introduced. William Whyte’s The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces underscores the importance of empirical, observational studies, setting a precedent for how seating arrangements, location, and other physical elements impact utilization and social dynamics in urban spaces (Whyte Citation1980; Zapata and Honey-Rosés Citation2020). This empirical approach is mirrored in modern smart city initiatives which integrate sensors and data analytics to capture real-time interactions and behaviours. Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City introduced the concept of imageability, emphasizing the role of identifiable urban elements in personal navigation and place attachment (Lynch Citation1960). His work has influenced digital mapping and augmented reality applications, enhancing personal and collective urban experiences (R. Wang, Nagakura, and Norford Citation2023). Matthew Carmona’s multifaceted approach in Public Places – Urban Spaces stresses the need for aesthetics, functionality, and social considerations in urban design, advocating for spaces that promote community interactions and enhance the quality of urban life (Carmona et al. Citation2010).

Nan Ellin’s (Citation1996) Postmodern Urbanism critiques the homogeneity of modernist urban planning and calls for diverse, flexible, and vibrant urban spaces, a sentiment reflected in contemporary urban design projects like the ‘15-minute city’ concept in Paris (Moreno et al. Citation2021). Yi-Fu Tuan’s (Citation1974) exploration of ‘topophilia’ emphasizes the emotional and cultural connections individuals form with places, influencing how spaces are used and perceived. This emotional dimension is vital in the design and revitalization of culturally significant areas, such as the waterfront in Liverpool (Balderstone, Milne, and Mulhearn Citation2013). Donald Appleyard’s (Citation1980) Livable Streets and Bentley et al.’s (Citation1985) Responsive Environments further contributes to the understanding of urban spaces by examining how road design affects community dynamics and by proposing a user-centric approach to urban design, respectively. Their work advocates for urban environments, prioritizing human experience, adaptability, and social interactions (Fraker and Fraker Citation2013).

Recent advances in evaluating UOS have led to the creation of diverse approaches for such assessments. The Multi-Attribute Value Theory (MAVT) (Oppio, Bottero, and Arcidiacono Citation2018) rates open spaces by measuring factors like accessibility, desirability, energy, and distinctiveness. This method, which was effectively employed in Milan, incorporates a four-stage process that combines planning with GIS-derived metrics, along with socio-economic and land-use information. The RECITAL tool (Knobel et al. Citation2021) focuses on the impact of urban greenery on health and has been used to appraise 149 areas successfully. A different technique involved scrutinizing TripAdvisor feedback about New York’s Bryant Park, offering a perspective on visitor experiences and the design features of the park (Fernandez et al. Citation2022).

Another assessment tool evaluates 12 spatial and managerial aspects of public parks, shedding light on challenges such as decline and excessive commercial use (Aly and Dimitrijevic Citation2022). This tool advocates for an all-encompassing evaluation rather than basic checklists, contributing to the enhancement of open space quality standards. Additionally, a strategic framework tailored to various social groups’ access to urban green spaces was implemented in cities like Catania, Italy, and Nagoya, Japan, proving its effectiveness in diverse city contexts (La Rosa et al. Citation2018). These advancements represent a notable move towards more complex, technologically driven, and user-focused methods in the evaluation of UOS with a view to improve their quality, access, and governance.

Limitations of traditional approaches and the shift towards participatory methods

Urban open space assessment methodologies consistently revolve around several key themes identified in . Accessibility stands out as a top priority, emphasizing the that open spaces should be easily reachable and usable for individuals of all ages and abilities. Community engagement is another pervasive theme since involving users in the assessment process contributes to creating more inclusive and community-centric open spaces. Environmental sustainability remains at the forefront, focusing on integrating green infrastructure, biodiversity, and resource conservation into urban open space design. Quality of life considerations like safety, health, well-being, and overall satisfaction with open spaces are also central to these assessment methods (Ye et al. Citation2023). Furthermore, the trend towards multi-functionality underscores the desire to design open spaces that accommodate diverse uses, from recreation and cultural events to urban agriculture.

Table 1. Frameworks and criteria for the assessment of urban open spaces based on examining the existing discourse.

Yet, UOS assessment methodologies encounter multiple challenges, including collecting accurate and comprehensive data, necessitating extensive resources and careful consideration of privacy concerns (Carmona et al. Citation2010). The siloed approach and inherent subjectivity in criteria such as aesthetics and user perceptions introduce variability and potential biases in the results. This complicates the integration of diverse criteria into a cohesive framework (Nasar Citation1990). These complexities often demand difficult trade-offs and pose certain challenges for smaller communities or organizations with limited resources and expertise. Moreover, resistance from various stakeholders, including residents, developers, and policymakers, can impede the adoption of new methods and the implementation of recommended changes (Healey Citation2006).

Additionally, traditional methods such as observational studies and GIS analyses have been fundamental in understanding UOS, but they often provide only a limited snapshot and frequently miss the dynamic nature of urban life (Whyte Citation1980). These methods might not fully capture the emotional and cultural dimensions of spaces, focusing predominantly on physical and functional aspects (Tuan Citation1974). Besides, the general lack of substantial public engagement in these traditional methodologies may lead to a misalignment between the intended design and actual utilization and use of spaces (Appleyard Citation1980). This recognition has led to various mobile applications, each targeting different attributes and experiences of urban spaces, offering a more dynamic and comprehensive approach to urban space assessment (Gordon and E Silva Citation2011).

Recognizing the need for more inclusive and collaborative methods, co-assessment seeks to involve a wide range of stakeholders in the decision-making process. It integrates the perspectives, localized knowledge, and experiences of community members, ensuring the UOS are assessed, planned, designed, and managed in a way that truly reflects the needs of the users. This approach responds to the identified challenges in traditional urban space assessment methods, aspiring to create more responsive, inclusive, and sustainable urban environments.

Technological advancements in urban open space assessment

The integration of mobile technology in urban space assessment is revolutionizing the way urban planners, designers, and citizens understand and interact with UOS. As observed by Townsend (Citation2013), mobile technology offers new avenues for monitoring, managing, and experiencing urban spaces. Mobile applications equipped with features such as GPS tracking, user surveys, and interactive maps can capture real-time data on use patterns, preferences, and feedback, providing valuable insights that drive informed decisions. Similarly, Gordon and de Souza e Silva (Citation2011) emphasize the transformative role of mobile apps in enhancing public participation in the urban planning process. These tools not only facilitate immediate feedback and suggestions from citizens but also enable democratization of planning and design processes.

The landscape of mobile applications for urban space assessment is diverse, each offering unique functionalities to enhance our understanding of urban environments. PlaceMeter, for instance, employs smartphone cameras to collect data on pedestrian and vehicle traffic, providing insights into the usage of open spaces (Green Citation2017). Community Walk allows users to create interactive walking tours, assessing physical characteristics and amenities in urban neighbourhoods (Prost et al. Citation2023). Similarly, PocketSights offers a unique approach by enabling the creation of self-guided tours, focusing on the cultural and historical significance of urban spaces (PocketSights Citation2016). Participatory GIS apps like GeoODK Collect and Mappt involve community participation in urban space assessment, integrating local knowledge into urban planning (Hartung et al. Citation2010).

Differing from these applications, YouWalk-UOS (Salama and Patil Citation2023, Citation2024) introduces a participatory approach by combining elements of pedestrian navigation, environmental quality assessment, and user-generated content. It allows users to navigate urban spaces and contribute data on diverse qualities, including environmental factors such as noise levels, air quality, and greenery, thereby providing a more holistic view of the urban open space experience.

Methodological approach for developing and validating YouWalk-UOS mobile application

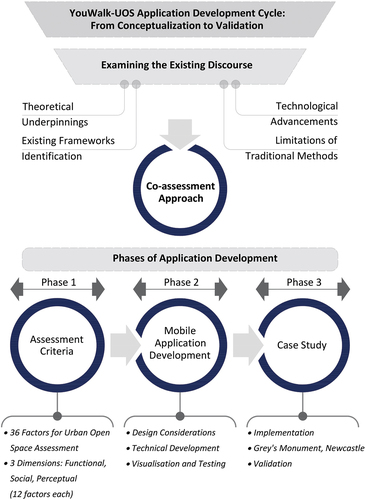

Designed to systematically capture and analyse the multifaceted aspects of UOS using the YouWalk-UOS mobile application, the study adopts a methodological approach that integrates a critical analysis of existing literature, identifies technological advancements, addresses gaps in traditional methods, and implements a co-assessment approach (). This is divided into three phases: development of assessment criteria, mobile application development, and a test case study.

Development of Assessment Criteria: This phase involves formulating cohesive assessment criteria that emanates from examining the existing discourse and are centred on the co-assessment approach. It integrates the three critical dimensions of UOS: functional, social, and perceptual, with 12 key factors identified for each dimension. The initial list of potential aspects was generated through insights from seminal works in the field of urban design (e.g., Whyte, Gehl, Lynch, Carmona, Pallasma, Bentley) and from recent urban open space assessment studies (Vukovic et al. Citation2021). The aspects were then redeveloped into answerable questions included in a walking tour assessment tool which was integrated into this mobile application for adaptability and wider applicability. This phase is important for guiding the subsequent design and functionality of the YouWalk-UOS mobile application and ensures that it aligns with the identified needs and challenges in urban open space assessment.

Mobile Application Development: This phase involves translating the assessment criteria into a practical tool. The technical development of the YouWalk-UOS app was undertaken with a clear focus on cross-platform functionality, employing React Native (Meta Open Source Citation2024) to facilitate deployment on both Android and iOS platforms. This choice was driven by the need to reach a broad user base of smartphone users. The design process prioritized user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) principles to ensure intuitive navigation and interaction with the various modules of the app. Prior to the launch of the application prototyping and usability testing procedures involved target user groups to gather feedback on the app layout, ease of use, and engagement with the assessment process. This participatory approach to the design of the app enabled the identification of usability challenges at the initial stages of the design of the app to enhance its overall user-friendliness. The focus is on creating a user-friendly interface where emphasis is placed on designing an intuitive, user-friendly interface that integrates advanced features like use of images and maps, real-time feedback, and geolocation capabilities to enhance the app’s effectiveness in providing insightful and context-rich data for urban space assessment and analysis.

Case Study Validation and Implementation: This final phase involves the practical application of the YouWalk-UOS app in a real-world setting. The Grey’s Monument, Newcastle, is selected as a case study to implement and validate the app. This phase includes deploying the app, engaging 88 participants for assessment. Participants for the Grey’s Monument case study were selected to represent a balanced demographic mix, with an equal distribution across genders and an age range of 25 to 50. The effectiveness of the app is then evaluated based on its ability to gather diverse perspectives, ease of use, and the relevance and accuracy of the data collected. The analysis of collected data employed statistical methods to quantify user perceptions and interactions within the space, with a focus on reliability and validity. This rigorous analytical approach highlighted patterns and outliers in the data, informing both the conclusions of the case study and broader implications for UOS assessment.

Co-assessment of urban open spaces

The co-assessment approach adopted in evaluating UOS represents a paradigm shift towards more inclusive and collaborative methodologies (Sutherland, Shackelford, and Christian Rose Citation2017). Rooted in the principles of participatory engagement, this approach brings together various stakeholders including residents, urban planners, and policymakers, to evaluate UOS. Unlike traditional top-down assessment methods, co-assessment emphasizes the importance of local knowledge and user experiences, ensuring that the assessment process is not only about expert analysis but also about understanding the needs, preferences, and perceptions of the community that uses and interacts with these spaces daily. Besides, co-assessment embraces technological advancements, including mobile applications, to offer a more holistic and comprehensive understanding of UOS, paving the way for more responsive and inclusive urban planning and design practices (Clark Citation2019). In essence, co-assessment prioritizes participatory engagement and collaborative evaluation, focusing on a democratic and inclusive decision-making process. These qualities can be explained in three terms:

Participatory Engagement: This approach prioritizes integrating the diverse users’ needs and preferences through recording direct impressions. It empowers urban space users to assess their environment acknowledging the essential role of these spaces in reflecting the area’s demographic and cultural diversity.

Collaborative Evaluation: Co-assessment is inherently participatory involving users in evaluating UOS. It recognizes that urban spaces evolve with their contexts where residents or users directly contribute to their assessment and management, aligning with the changing needs and social aspirations.

Collective Decision-Making: The goal of co-assessment is to develop UOS that boost the community’s overall well-being. This may eventually include codesigning or co-creation which fosters the development of spaces that support health, social interaction, and environmental sustainability while contributing to the community’s physical, social, and mental health through shared values and collective decision-making.

Incorporating the principles of participatory engagement and collaborative evaluation, the co-assessment approach transforms urban open space planning into a more inclusive, equitable, and effective process. It leads to spaces that are functionally apt and socially and culturally enriching, fostering a sense of ownership and pride among residents while ensuring that UOS are cherished and sustained as vital parts of the urban ecosystem.

Three Inter-related dimensions for co-assessment: the functional, the social, and the perceptual

The assessment criteria discussed in the existing literature on UOS often fall into broad categories reflecting physical characteristics, social dynamics, and environmental impacts. For instance, many frameworks emphasize accessibility, ecological benefits, and social engagement as key dimensions. However, these frameworks sometimes treat these categories as separate entities rather than interrelated aspects of UOS and thus lack a comprehensive approach that integrates various dimensions into a cohesive assessment tool. Therefore, it was essential to delineate categories that encompass both subjective and objective aspects of UOS.

Elicitation of the three dimensions and specific aspects

The three dimensions and their specific aspects were elicited through a multi-step process:

Literature Analysis: An extensive review of existing frameworks and criteria used in UOS assessments provided an initial list of aspects and dimensions commonly recognized in urban planning and design research.

User Feedback: Preliminary surveys and user feedback sessions were conducted to understand how individuals interact with and perceive UOS. This direct user input was instrumental in identifying and validating the relevance and comprehensiveness of the three dimensions and their specific aspects, ensuring the framework’s alignment with real-world user experiences.

Iterative Refinement: The framework was refined iteratively based on feedback from both experts and potential users. This process ensured that the framework was both theoretically robust and practically relevant, addressing the complexity of UOS in a comprehensive and integrated manner.

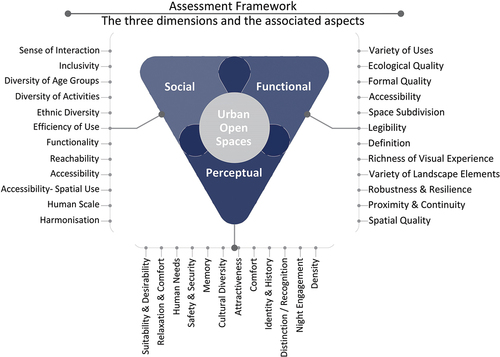

The framework integrated within the application originates by integrating the traditionally separate dimensions into a comprehensive, three-dimensional assessment model. This model includes three critical dimensions of UOS: functional, social, and perceptual. 12 key factors under each dimension have been identified to develop a UOS assessment framework ().

The functional dimension

The functional dimension is central to assessing UOS, serving as a comprehensive framework for evaluating their design, utility, and impact on urban life. Rooted in understanding urban dynamics and human-environment interactions, this dimension scrutinizes how UOS perform across various criteria to ensure they are vibrant, inclusive, sustainable, and positively integrated into the urban fabric.

At the heart of this dimension are 12 critical aspects, detailed in , which collectively define this dimension. These aspects range from diverse activities and accessibility to ecological quality and aesthetic appeal, providing a multifaceted view of how spaces serve community needs. Accessibility is considered from a physical perspective and how spaces foster a sense of belonging and safety for all users. The ecological quality focuses on how these areas harmonize with nature, promoting biodiversity and sustainability.

Table 2. UOS functional assessment aspects (Source: Authors).

Additionally, the aesthetic and formal qualities of UOS are scrutinized for their design and sensory impact, crucial in attracting users and encouraging positive interactions. The spatial organization, including subdivision, legibility, and the relationship between various areas within the space are also evaluated to understand how well spaces are navigated.

The social dimension

The social dimension focuses on the collective and interactive user experiences that urban spaces facilitate including inclusivity, community engagement and social interaction. It examines the complex relationship between people and their environment, extending beyond physicality to shape public spaces’ social dynamics and inclusivity. This dimension includes 12 key aspects that collectively consider interaction, inclusivity, diversity, and a sense of community as detailed in . The social dimension focuses on how UOS promote or impede social well-being. It investigates the design, features, and management of spaces to determine their role in facilitating or hindering social interactions and cohesion. The dimension emphasizes the need for inclusivity and diversity, ensuring spaces are accessible and relevant to all demographics while reflecting and catering to a wide range of cultural, recreational, and social needs.

Table 3. UOS social assessment aspects (Source: Authors).

Safety, security, and the psychological impacts of UOS are also paramount within the social dimension. These factors contribute to the perceived safety and psychological benefits, including stress reduction and mood enhancement. Additionally, it considers the role of UOS in reflecting and shaping community identity and character. In summary, the social dimension, with its 12 critical aspects, guides the creation of vibrant, inclusive, and harmonious communities by ensuring spaces are not only physically accessible but also socially enriching and emotionally supportive.

The perceptual dimension

The perceptual dimension plays a critical role in understanding the impact of UOS on users, emphasizing subjective experiences, emotional connections and sensory perceptions evoked by these spaces. This includes how users perceive and feel about the space regarding aesthetics, safety, and personal attachment. It encompasses twelve key aspects detailed in . It integrates sensory and psychological characteristics that collectively shape how spaces are perceived, experienced, and valued. Together, these aspects determine the overall effectiveness and resonance of UOS with those who use them. Visual elements such as aesthetics, lighting, colour schemes, and the incorporation of art and nature are the first to impact users, influencing their initial impression and sense of indulgence. Auditory experiences from natural or urban sounds create the atmosphere, affecting tranquillity and perceived quality. Olfactory elements enhance or detract from the desirability of the space, while tactile interactions contribute to physical comfort and psychological well-being.

Table 4. UOS perceptual assessment aspects (Source: Authors).

In essence, the perceptual dimension not only examines immediate sensory experiences but also aims to understand long-term perceptions, interactions, and emotional connections. Understanding and thoughtfully designing for these sensory experiences enable designers to create UOS that are functional, deeply resonant, and appealing, enhancing the quality of urban life for all users.

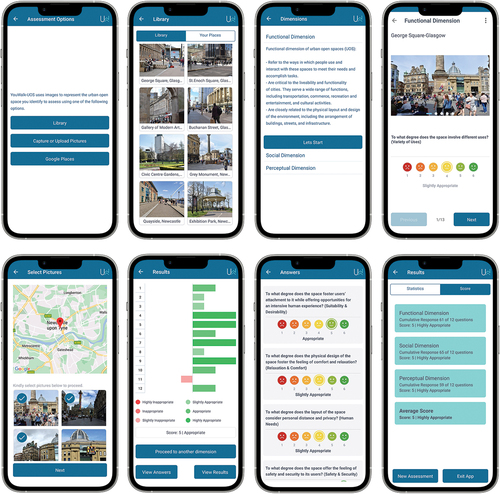

YouWalk-UOS: overview and key features

The YouWalk-UOS mobile application was rigorously developed to serve as a comprehensive tool for assessing UOS. It incorporates detailed features tailored to capture the multifaceted nature of urban environments (), which can be outlined as follows:

Three-Dimensional Assessment Framework: The core functionality of the application is built around assessing UOS through three key dimensions – functional, social, and perceptual. The functional dimension evaluates the physical attributes and infrastructural quality. The social dimension focuses on the social interactions and communal activities facilitated by the space. The perceptual Dimension captures users’ personal experiences and subjective feelings towards the space.

Utilization of Likert Scale for User Feedback: The app employs a Likert scale for user responses, allowing user feedback on various aspects of UOS. This scale enables users to express degrees of agreement or satisfaction with specific attributes of the urban space, providing insights into user perceptions and experiences. 12 questions were developed under the three dimensions to which users should react using the Likert Scale. While the users don’t have opportunity to add text that explains their experience, they are given the facility to introduce an additional question under each category that reflects their own interest based on their experience.

Integration of Images for Enhanced Assessment: Users can upload images to provide visual context to their assessments. This feature enriches the data with visual evidence, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of physical and aesthetic aspects of the space being assessed.

GPS Functionality for Location Identification: The application incorporates GPS technology to identify and tag the location of assessments accurately. This feature ensures that feedback is accurately associated with specific UOS, enhancing the reliability of the data collected.

Data Visualization and Analysis Tools: YouWalk-UOS provides users with tools for data visualization, such as interactive graphs and maps, enabling them to interpret patterns and trends in urban space qualities and use.

Following the development phase, the YouWalk-UOS application underwent a thorough testing process, essential for ensuring its reliability and effectiveness. This testing phase included both technical evaluations and user trials to identify and rectify any functional issues, enhance usability and interface, and confirm the app’s alignment with its co-assessment approach. Technical testing focused on its stability, data accuracy, and integration of features like real-time feedback and geolocation. User trials involved individuals who tested the app in real UOS, providing valuable feedback on its usability and the relevance of the data collected. The app was fine-tuned through this comprehensive testing approach to become a robust tool for UOS evaluation. The development process also prioritized user privacy and data security, adhering to best practices and regulations to protect sensitive information.

The Grey’s Monument, Newcastle, UK- A case study

The Grey’s Monument is a significant historical landmark in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, and a central urban open space that serves as a hub of social and cultural activity. The monument is at the top of Grey Street, a prestigious thoroughfare known for its elegant Georgian architecture and vibrant atmosphere. The street, which leads down from the monument towards the Tyne River, has been acclaimed as one of the most beautiful in England and is lined with various shops, cafes, and cultural institutions (Akkar Ercan Citation2005; Faulkner Citation2000). The open space surrounding Grey’s Monument is a popular meeting point and hosts various events, markets, and social gatherings. The layout of the space is characterized by its openness and accessibility, inviting interaction and congregation. Paved areas and seating around the monument allow people to gather and enjoy the urban setting ().

As an urban open space, the Monument area is well-organized and maintained, reflecting the city’s commitment to preserving its historical and cultural assets while providing a functional and enjoyable public space. The location is a nexus for public transport, with the Monument Metro station nearby, making it a highly accessible and frequented spot by locals and tourists (Akkar Ercan Citation2005; Lloyd Citation1977). The Grey’s Monument and surrounding area symbolize Newcastle’s identity, blending historical significance with contemporary urban life. The space is not only an ode to Earl Grey and the city’s past but also a living, breathing part of Newcastle’s urban landscape, accommodating its community’s social and cultural needs (Faulkner Citation2000).

During the implementation and validation phase of the YouWalk-UOS mobile application, participants were asked to engage directly with the Grey’s Monument. Each participant was provided with the application and tasked to navigate the space, utilizing the app to assess and respond to the series of 12 questions under each of the three dimensions – functional, social, and perceptual. Participants were also encouraged to provide feedback on the app’s functionality, usability, and overall design, contributing valuable insights into its performance and areas for potential improvement. This participatory approach aimed to ensure that the application not only met the technical and theoretical standards of urban space assessment but also resonated with and was accessible to diverse needs and perspectives of actual users.

Discussion of key findings

Validating the operational capabilities of the YouWalk-UOS mobile application, a balanced group of 88 individuals – comprising equal numbers of male and female participants within the age range of 25 to 50—engaged in a comprehensive assessment of the Grey’s Monument in Newcastle. Most of the participants were familiar with the space and have experienced it at least once. However, they were asked to interact with the space for exclusive purpose of assessing it by reacting to the questions underlying the three dimensions.

The case study aimed to validate:

Technical Performance: Ensuring the app’s features worked as intended, including location tagging, image upload functionality, and response recording.

User Experience: Evaluating the app’s ease of use, navigability, and overall user experience in engaging with the assessment process of UOS.

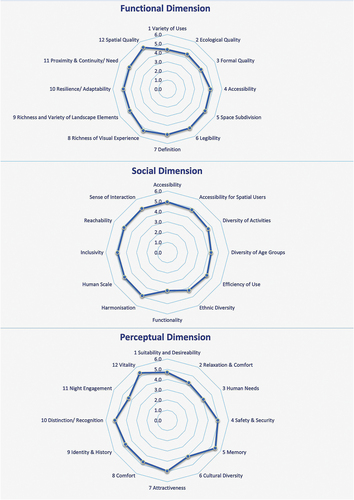

The findings () from this targeted demographic reveal both the strengths and potential areas for improvement.

The functional dimension

The YouWalk-UOS app survey gathered commendable ratings (average scores) for its multifunctionality, ecological consciousness, and thoughtful design. Participants consistently rated the variety of uses and its environmental design with averages above 4.0, indicating a well-received blend of natural elements with urban utility. In physical terms, the design aligns with the ecological setting, suggesting a symbiosis between urban form and natural elements. This balance points to a growing trend in urban planning that places ecological considerations at the forefront.

Moreover, the accessibility is a standout feature, with average scores approaching 5.0, signifying the success of the space as an inclusive gathering hub that accommodates people from all walks of life. The settings within the space, tailored for various social interactions, are evidently successful, facilitating both community events and individual relaxation. The Monument’s distinct architectural features and well-defined edges enhance its legibility, contributing to a strong sense of place that is visually and spatially coherent. This coherence extends to the rich visual and landscaped elements, which participants greatly value, achieving an average score of 4.8, which further enriches the user experience.

In terms of adaptability and urban integration, the space demonstrates resilience and an enduring relevance to the surrounding urban context. Its design anticipates future needs, allowing for modifications that could support evolving community requirements. Such flexibility in designing urban spaces is crucial for long-term utility and sustainability. The Monument’s role within the urban fabric of Newcastle is thus not only a functional amenity but also a pivotal cultural landmark. It represents a harmonious balance of past and present, tradition and innovation, offering a versatile and vibrant environment that enhances the urban experience of users.

The social dimension

The assessment of the social dimension reveals that the space achieved a near-universal commendation for fostering social interaction, with an average score close to 5.0, signifying a vibrant communal atmosphere. This is a strong indicator that the space successfully promotes engagement among its users, a key aspect of social sustainability in urban design. Inclusivity also rated highly, with an average score of 5.0 suggesting that the Monument is welcoming to a diverse population, regardless of background or ability.

Further analysis shows that the space accommodates a diversity of age groups and social activities well, reflecting a versatile and adaptable space to various social needs. It received particularly high ratings, with an average score of 5, for its ability to efficiently promote interaction among different social groups and serve different social purposes, signifying a well-utilized space. However, there were slightly lower scores for ethnic diversity, with average scores 4 and efficiency of use, with average scores 4.5, indicating room for improvement in these aspects. The functionality of the space furniture also received a varied response, suggesting that while it serves multiple users and activities, there may be a need for better accommodation of specific groups or activities.

The reachability and overall accessibility of the space scored exceptionally high (5.0), indicating that the space is well-connected to various modes of transportation and easily accessible from the urban surroundings. Accessibility for those with special needs also received high average scores (4.8), pointing towards a well-cogitated design that considers a wide range of user requirements. Lastly, the assessment showed that the Monument’s design is perceived to respect human scale and harmonize with the surrounding context, suggesting that the space complements its urban setting and contributes to a coherent cityscape.

The perceptual dimension

The space scored exceptionally well in the perceptual dimension as fosters attachment and offers intensive human experience, as seen in the high average scores for suitability and desirability (4.7). This suggests that the space is well-liked and provides a setting where people feel a deep sense of belonging and engagement. The architectural character of the space also made a lasting impression, with high average scores for being memorable (5.4), thus contributing to a sense of place and identity that are crucial for drawing people back to the space.

Comfort and relaxation within the Grey’s Monument were perceived positively, though slightly lower (4.2) than other perceptual aspects, indicating a general sense of ease and tranquillity. The consideration for -human needs was moderately scored (4.1), suggesting that while the space is well-designed, there may be opportunities to improve these aspects to enhance the personal comfort and privacy of its users. Safety and security received one of the highest average scores (4.9), as fundamental aspects of usability, especially during night hours. This sense of security is likely a key factor in the perceived vibrancy and vitality, which also scored highly (5.4), indicating that the space is lively and energetic.

The recognition of the space indicates that participants perceived the space as highly representative of its context with an average score of 5.1. However, scores for cultural diversity considering different groups were comparatively lower (4.1), pointing to potential improvement areas in making the space even more inclusive. The ability of the space to support security and safety at night received mixed responses indicating that while generally seen as secure, there might be a need for enhanced facilities or lighting to further improve night-time engagement.

During the implementation of the case study, participants were actively encouraged to provide feedback on their experiences with the YouWalk-UOS mobile application. It was recorded both on the website designated for the project and through direct verbal conversations with the participants. From this valuable input, two primary points for improvement emerged:

Report Generation with Integrated Visuals: While the app currently offers chart functionalities, users have expressed the need for a report generation feature that integrates these visual data representations. Enhancing the app to compile comprehensive reports that include both the analytical data, and the corresponding charts would facilitate a more effective presentation and interpretation of the findings. Such a feature would enable users to download and share detailed reports, complete with graphical insights, for a range of uses from stakeholder presentations to community discussions.

Enhancing Offline Functionality. Users reported challenges when accessing the app in areas with limited or no internet connectivity, hindering their ability to complete assessments or save their progress in real time. This feedback underscores the necessity for the app to offer robust offline capabilities, allowing users to conduct assessments and save their input seamlessly, irrespective of their connection status. Implementing such functionality would ensure that data can be collected and stored locally on the user’s device and then synchronized with the server once an internet connection is re-established.

Analytical reflections

In interpreting the preliminary findings resulting from the implementation of YouWalk-UOS to assess the Grey’s Monument in Newcastle, it is vital to contextualize the results within the broader discourse of urban design. The initial user group, carefully selected to represent a gender-balanced demographic between the ages of 25 to 50, provided a focused lens through which the application’s capacity to capture the multifaceted experiences of UOS can be evaluated. Functionally, the space excels in visual richness and accessibility which are key aspects of good urban form as outlined by Alexander (Citation1978) and earlier by Sitte (Citation1945). The results confirm the Monument’s alignment with these principles, presenting a space that is not only accessible but also aesthetically engaging. However, the need for improved ecological features and adaptability suggests prioritizing green infrastructure and flexible spaces that respond to changing environmental and social conditions.

The data gathered speaks to a strong sense of social interaction and inclusivity, core tenets of urban social sustainability as urban theorists such as Jacobs (Citation1961), Landorf (Citation2009) Madanipour (Citation2010) and Gehl (Citation2010) espoused. These results underscore the Monument’s role as a civic space that successfully fosters social capital – an aspect that is increasingly recognized as essential to the resilience and vibrancy of urban areas. The moderate scores in age-range inclusivity and furniture functionality, however, point to an area often highlighted in urban theory: the need for adaptable spaces to the full spectrum of user needs. This aligns with the principles of universal design, which argue for creating environments usable by all individuals, irrespective of age or ability, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.

The perceptual experience of urban spaces, as captured by the YouWalk-UOS app, reveals a strong personal and emotional connection in Grey’s Monument, highlighting its success as a space of identity and memory, resonant with concept of ‘imageability’ (Evans, McDonald, and David Rudlin, and Academy of Urbanism (Organization) Citation2011; Madanipour Citation2013; Meenar, Afzalan, and Hajrasouliha Citation2019) and ‘sense of place’ (McCunn and Gifford Citation2021; Pallasmaa Citation2012). The participants’ appreciation for the Monument’s night-time vibrancy and safety points to effective urban design that supports Lynch’s idea of legibility and vitality after dark. However, concerns about noise and the need for enhanced night-time amenities draw attention to the balance between urban buzz and the individual’s comfort, suggesting a need for a more holistic approach to urban design, perhaps through the lens of soundscape planning and design.

These findings have profound implications for the future of urban design, particularly in advancing user-centred and participatory planning approaches. The insights from this validation of the YouWalk-UOS application demonstrate the potential for mobile technology to bridge the gap between users of urban space users, designers, and decision makers. By providing a platform for users to voice opinions on their experiences and perceptions, the application aligns with contemporary participatory design models (Sanoff Citation2000) that value stakeholder engagement and collaborative decision-making.

Conclusion

The exploration into the utilization of the YouWalk-UOS mobile application presents a pioneering contribution to urban design discourse, demonstrating how mobile technology can deepen the understanding of UOS and encourage a more participatory approach to urban assessment. Deployed at Grey’s Monument in Newcastle, this research not only underscores the vital role of UOS in enhancing social engagement and inclusivity but also identifies avenues for increasing the utility and accessibility of such spaces in alignment with principles of promoting community well-being and environmental sustainability.

Across the functional dimension, participants provided high ratings for aspects such as the variety of uses, ecological quality, and formal quality, indicating that Grey’s Monument serves as a vibrant, ecological, and well-designed space within its urban context. In particular, accessibility and space subdivision were rated notably high, underscoring the monument’s integration into the urban fabric and its provision of diverse settings for public use. Furthermore, the legibility of the space and the richness of visual experience were recognized, reflecting the unique architectural character that resonates with residents and visitors alike.

In the social dimension, the space excelled in promoting social interaction, with inclusivity and diversity of age groups also scoring high, although there is room for improvement in areas such as ethnic diversity and efficiency of use. Notably, the space was commended for its reachability and accessibility, catering to users with special needs – a testament to its design’s inclusivity.

The perceptual dimension revealed participants’ strong attachment and sense of desirability towards the space, alongside a considerable degree of comfort and relaxation. However, there were suggestions for a better consideration of personal distance and privacy, which are key factors in human-centric urban design. While safety and security at night received mixed scores, the overall score of the factor of safety and security was deemed excellent. This contributes to the vibrancy and vitality of the space, and is indicative of a well-utilized and cherished public area.

Yet, the study acknowledges methodological limitations, including non-representative sample sizes and the potential for researcher and participant biases, which may impact the objectivity of results and generalizability of findings. The digital divide is a critical challenge, as reliance on mobile technology may exclude the less technologically connected, highlighting the importance of more inclusive assessment methods. Planned updates to the YouWalk-UOS application aim to enhance inclusivity, address the digital divide, and ensure that the application can be utilized by a broader spectrum of the population, including those with limited access to technology. Additionally, adjustments could be made to expand the qualitative data collection by allowing users to add open-ended comments, stories, and experiential narratives.

For both academic and practical contexts, the app provides a platform for real-time and data-driven insights. Academically, it serves as an essential tool within urban studies curricula, enabling hands-on learning experiences for students in urban planning, architecture, and environmental studies. This experiential approach aids students in grasping the complexities of the functionality of urban space and the dynamics of user interaction. Practically, the app provides urban planners and designers with immediate feedback on how spaces are utilized and perceived, allowing for agile adjustments to ongoing interventions and improvement projects. Integrating this tool into the iterative design process would help professionals to continuously refine their projects to better meet community needs, effectively bridging the gap between theoretical planning and real-world application.

Looking to the future planning for further refinement, broadening the demographic reach of YouWalk-UOS users and extending the assessment across different seasons would enrich the quality of the data collected and provide a more comprehensive view of the outcomes. Notably, longitudinal studies could offer further insights into the evolving dynamics between urban spaces and their users, which are critical for future adaptations, adjustments, and responsive improvement interventions.

While this study marks a significant advancement in integrating technology and participatory methods into urban design assessments, it highlights essential challenges that need further enhancement. The limitations identified emphasize the necessity for ongoing refinement of the methodologies adopted as well as a commitment to inclusivity. Addressing these challenges is crucial for fulfilling a profound assessment towards more vibrant, inclusive, and sustainable urban spaces.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to everyone who contributed to this study. We appreciate the support from colleagues and peers at Northumbria University’s Architecture and Built Environment Department, whose perspectives and critiques have been immensely beneficial. We sincerely thank the participants and stakeholders involved, whose cooperation and input were crucial to the testing of the YouWalk-UOS.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akkar Ercan, M. 2005. “The Changing ‘Publicness’ of Contemporary Public Spaces: A Case Study of the Grey’s Monument Area, Newcastle Upon Tyne.” Urban design international 10 (2): 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000138.

- Akkar Ercan, M. 2016. “‘Evolving’ or ‘Lost’ Identity of a Historic Public Space? The Tale of Gençlik Park in Ankara.” Journal of Urban Design 22 (4): 520–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2016.1256192.

- Alexander, C. 1978. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Center for Environmental Structure Series. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Aly, D., and B. Dimitrijevic. 2022. “Assessing Park Qualities of Public Parks in Cairo, Egypt.” Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 18 (1): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/arch-03-2022-0073.

- Amin, A. 2007. “Re‐Thinking the Urban Social.” City 11 (1): 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810701200961.

- Amin, A. 2008. “Collective Culture and Urban Public Space.” City 12 (1): 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810801933495.

- Appleyard, D. 1980. “Livable Streets: Protected Neighborhoods?” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 451 (1): 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271628045100111.

- Balderstone, L., G. J. Milne, and R. Mulhearn. 2013. “Memory and Place on the Liverpool Waterfront in the Mid-Twentieth Century.” Urban History 41 (3): 478–496. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0963926813000734.

- Beatley, T. 2000. Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Bentley, I., A. Alcock, P. Murrain, S. McGlynn, and G. Smith. 1985. Responsive Environments - a Manual for Designers. Oxford: Architectural Press.

- Bosselmann, P. 2012. Urban Transformation: Understanding City Form and Design. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Carmona, M., S. Tiesdell, T. Heath, and T. Oc. 2010. Public Place Urban Space, the Dimension of Urban Design. Oxford: Architectural Press. Second Edi.

- Carr, S. 1992. Public Space. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Chiesura, A. 2004. “The Role of Urban Parks for the Sustainable City.” Landscape and Urban Planning 68 (1): 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.08.003.

- Clark, B. Y. 2019. “Co-Assessment through Digital Technologies.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3479480.

- Cozens, P. 2008. “Crime Prevention through Environmental Design in Western Australia: Planning for Sustainable Urban Futures.” International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 3 (3): 272–292. https://doi.org/10.2495/sdp-v3-n3-272-292.

- Cullen, G. 1961. Townscape. London: Architectural Press.

- Degen, M. M., and G. Rose. 2012. “The Sensory Experiencing of Urban Design: The Role of Walking and Perceptual Memory.” Urban Studies 49 (15): 3271–3287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012440463.

- Dovey, K., and E. Pafka. 2013. “The Urban Density Assemblage: Modelling Multiple Measures.” Urban Design International 19 (1): 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2013.13.

- Ellin, N. 1996. Postmodern Urbanism. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell.

- Evans, B. M., F. McDonald, and David Rudlin, and Academy of Urbanism (Organization). 2011. Urban Identity-Learning from Place. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Ewing, R., and S. Handy. 2009. “Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability.” Journal of Urban Design 14 (1): 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800802451155.

- Faulkner, T. E. 2000. Architects and Architecture of Newcastle upon Tyne and the North East, C. 1760-1960. Doctoral thesis, University of Northumbria at Newcastle.

- Fernandez, J., Y. Song, M. Padua, and P. Liu. 2022. “A Framework for Urban Parks.” Landscape Journal 41 (1): 15–29. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.41.1.15.

- Fraker, H. 2013. “Hammarby Sjöstad, Stockholm, Sweden.” In The Hidden Potential of Sustainable Neighborhoods, 43–67. Island Press/Center for Resource Economics. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-409-3_3.

- Friedman, A. 2021. “Open Spaces as an Urban System.” In Fundamentals of Sustainable Urban Design, edited by A. Friedman, 225–233. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60865-1_24.

- Gehl, J. 2010. Cities for People. 1st ed. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Gehl, J. 2011. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Gehl, J., and L. Gemzøe. 1996. Public Spaces, Public Life. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Architectural Press and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture.

- Gehl, J., L. Johansen Kaefer, and S. Reigstad. 2006. “Close Encounters with Buildings.” Urban Design International 11 (1): 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000162.

- Gordon, E., and A. de Souza e Silva. 2011. Net Locality: Why Location Matters in a Networked World. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Green, J. 2017. “Placemeter Measures the Flow of People through Urban Spaces.” Industry Dive. Accessed 29 April 2024. https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/placemeter-measures-flow-people-through-urban-spaces/.

- Hanyu, K. 2000. “Visual Properties and Affective Appraisals in Residential Areas in Daylight.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 20 (3): 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0163.

- Hartung, C., A. Lerer, Y. Anokwa, C. Tseng, W. Brunette, and G. Borriello. 2010. “Open Data Kit: Tools to Build Information Services for Developing Regions.” Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1145/2369220.2369236.

- Healey, P. 2006. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. 2nd ed. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

- Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1989. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Imrie, R. 1996. Disability and the City: International Perspectives. London: P. Chapman.

- Iwarsson, S., and A. Ståhl. 2003. “Accessibility, Usability and Universal Design—Positioning and Definition of Concepts Describing Person-Environment Relationships.” Disability and Rehabilitation 25 (2): 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/dre.25.2.57.66.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books. New York: Random House.

- Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kellert, S. R., J. Heerwagen, and M. Mador. 2008. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Knobel, P., P. Dadvand, L. Alonso, L. Costa, M. Español, and R. Maneja. 2021. “Development of the Urban Green Space Quality Assessment Tool (RECITAL).” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 57 (January): 126895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126895.

- La Rosa, D., C. Takatori, H. Shimizu, and R. Privitera. 2018. “A Planning Framework to Evaluate Demands and Preferences by Different Social Groups for Accessibility to Urban Greenspaces.” Sustainable Cities and Society 36 (January): 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.10.026.

- Landorf, C. 2009. “Social Inclusion and Sustainable Urban Environments: An Analysis of the Urban and Regional Planning Literature.” In Proceedings of Second International Conference on Whole Life Urban Sustainability and Its Assessment, edited by M. Horner, A. Price, J. Bebbington, and R. Emmanuel, 847–864. Dundee: SUE-MoT.

- Lang, J. T. 1974. Designing for Human Behavior: Architecture and the Behavioral Sciences. Community Development Series. Dowden: Hutchinson & Ross.

- Lloyd, D. 1977. “Urban Evaluation: Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.” Built Environment Quarterly 3 (2): 139.

- Low, S., D. Taplin, and S. Scheld. 2005. Rethinking Urban Parks: Public Space and Cultural Diversity. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, Mass: Technology Press & Harvard University Press.

- Madanipour, A. 2010. “Whose Public Space.” In Whose Public Space? International Case Studies in Urban Design and Development, edited by A. Madanipour, 237. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Madanipour, A. 2013. “The Identity of the City.” In City Project and Public Space. Urban and Landscape Perspectives, edited by S. Serreli, 49–63. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6037-0_3.

- Marcus, C. C., and C. Francis. 1997. People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- McCunn, L. J., and R. Gifford. 2021. “Place Imageability, Sense of Place, and Spatial Navigation: A Community Investigation.” Cities 115 (August): 103245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103245.

- Meenar, M., N. Afzalan, and A. Hajrasouliha. 2019. “Analyzing Lynch’s City Imageability in the Digital Age.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 42 (4): 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456x19844573.

- Mees, C., ed. 2021. Urban Open Space+. De Gruyter. September. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783868599848.

- Mehta, V. 2013. “Evaluating Public Space.” Journal of Urban Design 19 (1): 53–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2013.854698.

- Meta Open Source. 2024. “Create Native Apps for Android, IOS, and More using React.” Meta Platforms, Inc. Accessed 29 April 2024. https://reactnative.dev/.

- Moreno, C., Z. Allam, D. Chabaud, C. Gall, and F. Pratlong. 2021. “Introducing the ‘15-Minute City’: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities.” Smart Cities 4 (1): 93–111. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010006.

- Mosca, E. I., and S. Capolongo. 2020. “Universal Design-Based Framework to Assess Usability and Inclusion of Buildings.” Computational Science and its Applications–ICCSA 2020: 20th International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, July 1–4, 2020, Proceedings, Part V 20, 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58814-4_22.

- Nasar, J. L. 1989. “Perception, Cognition, and Evaluation of Urban Places.” In Public Places and Spaces, edited by I. Altman and E. H. Zube, 31–56. Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-5601-1_3.

- Nasar, J. L. 1990. “The Evaluative Image of the City.” Journal of the American Planning Association 56 (1): 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369008975742.

- Newman, O. 1972. Defensible Space; Crime Prevention through Urban Design. Architecture/Urban Affairs. New York: Macmillan.

- Nikšič, M., and G. Butina Watson. 2017. “Urban Public Open Space in the Mental Image of Users: The Elements Connecting Urban Public Open Spaces in a Spatial Network.” Journal of Urban Design 23 (6): 859–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2017.1377066.

- Oppio, A., M. Bottero, and A. Arcidiacono. 2018. “Assessing Urban Quality: A Proposal for a MCDA Evaluation Framework.” Annals of Operations Research 312 (2): 1427–1444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-017-2738-2.

- Pallasmaa, J. 2012. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

- PocketSights. 2016. “PocketSights Tour Guide Creates Worldwide Tour Platform.” Accessed 1 January 2024. https://pocketsights.wordpress.com/2016/01/20/pocketsights-tour-guide-creates-worldwide-tour-platform/.

- Prost, S., V. Ntouros, G. Wood, H. Collingham, N. Taylor, C. Crivellaro, J. Rogers, and J. Vines. 2023. “Walking and Talking: Place-Based Data Collection and Mapping for Participatory Design with Communities.” Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 2437–2452. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596054.

- Punter, J., and M. Carmona. 1997. “Design Policies in Local Plans: Recommendations for Good Practice.” Town Planning Review 68 (2): 165. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.68.2.k27375u187571462.

- Salama, A. M., and M. P. Patil. 2023. “Co-Assessment: YouWalk, YourVoice, YourCity.” Accessed 25 May 2024. https://youwalkuos.net.

- Salama, A. M., and M. P. Patil. 2024. “‘YouWalk-UOS’ – Technology-Enabled and User-Centred Assessment of Urban Open Spaces.” Open House International. https://doi.org/10.1108/ohi-01-2024-0021.

- Sanoff, H. 2000. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. New York: Wiley.

- Shaftoe, H. 2008. Convivial Urban Spaces: Creating Effective Public Places. London: Earthscan.

- Sitte, C. 1945. The Art of Building Cities: City Building According to its Artistic Fundamentals. New York: Reinhold.

- Southworth, M. 2005. “Designing the Walkable City.” Journal of Urban Planning and Development 131 (4): 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9488(2005)131:4(246).

- Sutherland, W. J., G. Shackelford, and D. Christian Rose. 2017. “Collaborating with Communities: Co-Production or Co-Assessment?” Oryx 51 (4): 569–570. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0030605317001296.

- Talen, E. 2022. “The Urban Design Requirements of Smart Growth.” In Handbook on Smart Growth: Promise, Principles, and Prospects for Planning, edited by G.-J. Knaap, R. Lewis, A. Chakraborty, and K. June-Friesen, 128. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Thielke, S., M. Harniss, H. Thompson, S. Patel, G. Demiris, and K. Johnson. 2011. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs and the Adoption of Health-Related Technologies for Older Adults.” Ageing International 37 (4): 470–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-011-9121-4.

- Thwaites, K., E. Helleur, and I. M. Simkins. 2005. “Restorative Urban Open Space: Exploring the Spatial Configuration of Human Emotional Fulfilment in Urban Open Space.” Landscape Research 30 (4): 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390500273346.

- Townsend, A. M. 2013. Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1974. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Tales and Travels of a School Inspector Series. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Tzoulas, K., K. Korpela, S. Venn, V. Yli-Pelkonen, A. Kaźmierczak, J. Niemela, and P. James. 2007. “Promoting Ecosystem and Human Health in Urban Areas using Green Infrastructure: A Literature Review.” Landscape and Urban Planning 81 (3): 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.02.001.

- Ulrich, R. S. 1983. “Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment.” In Behavior and the Natural Environment, 85–125. Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9_4.

- UN- Habitat. 2020. “City-Wide Public Space Assessment Toolkit- a Guide to Community-Led Digital Inventory and Assessment of Public Spaces.” Nairobi, Kenya. Accessed 19 January 2024. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/07/city-wide_public_space_assessment_guide_0.pdf.

- UN-Habitat. 2006. “The State of the World Cities Report. UN Human Settlement Programme.” Accessed 9 December 2023. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/State_of_the_World’s_Cities_20062007.pdf.

- Verma, P., and A. S. Raghubanshi. 2018. “Urban Sustainability Indicators: Challenges and Opportunities.” Ecological Indicators 93 (October): 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.05.007.

- Vukovic, T., A. M. Salama, B. Mitrovic, and M. Devetakovic. 2021. “Assessing Public Open Spaces in Belgrade – a Quality of Urban Life Perspective.” Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 15 (3): 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/arch-04-2020-0064.

- Wang, J., and K. Foley. 2021. “Assessing the Performance of Urban Open Space for Achieving Sustainable and Resilient Cities: A Pilot Study of Two Urban Parks in Dublin, Ireland.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 62 (July): 127180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127180.

- Wang, R., T. Nagakura, and L. K. Norford. 2023. “City Image: A Dynamic Perspective using Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing.” ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Whyte, W. H. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, D.C.: Conservation Foundation.

- Woolley, H. 2008. “Watch this Space! Designing for Children’s Play in Public Open Spaces.” Geography Compass 2 (2): 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00077.x.

- Ye, X., X. Ren, Y. Shang, J. Liu, H. Feng, and Y. Zhang. 2023. “The Role of Urban Green Spaces in Supporting Active and Healthy Ageing: An Exploration of Behaviour–Physical Setting–Gender Correlations.” Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/arch-04-2023-0096.

- Zapata, O., and J. Honey-Rosés. 2020. “The Behavioral Response to Increased Pedestrian and Staying Activity in Public Space: A Field Experiment.” Environment and Behavior 54 (1): 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916520953147.