ABSTRACT

The child welfare service in Norway is in the spotlight internationally after the European Court of Human Rights (EMD) convicted Norway of human rights violations in several child welfare cases. Norwegian child welfare services are presented as having weaknesses in competence, prioritization, structure and supervision. The child welfare service in Norway has a decentralized structure, and most tasks are a municipal responsibility. The paper explores what leadership challenges the municipal child welfare leaders are facing at a time when the service is under great pressure, and how we can understand these challenges using paradox theory. The empirical data are based on qualitative interviews with child welfare leaders from different municipalities in Norway. The study shows that Norwegian child welfare leaders have to deal with increasing complexity, and experience tensions between contradictory demands. Child welfare leaders manage multiple, interrelated paradoxes, and handle tensions in different ways. Further, the study shows that paradoxical tensions challenge the professional judgement and that the child welfare leaders’ managerial discretion is reduced. Finally, we discuss the findings as well as the practical implications for managing child welfare services in Norway.

Introduction

Norway’s child welfare service is in the spotlight internationally. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has convicted Norway of human rights violations in several child welfare cases and 35 Norwegian child protection cases have been referred to the ECHR. This is attracting international attention (Hansen, Citation2019), and Norwegian child welfare is being presented as a system with weaknesses in competence, prioritization, structure and supervision (Totland, Citation2019).

The child welfare service in Norway has a decentralized structure, and most tasks are assigned at the municipal level. The article highlights what leadership challenges the leaders of municipal child welfare are facing at a time when this service is under great pressure, and how we can use paradox theory to improve our understanding of these challenges. The article is based on interviews with 20 municipal child welfare leaders in various Norwegian municipalities.

Child welfare leadership is often characterized as challenging and demanding (McFadden, Campbell, & Taylor, Citation2014; Moe & Gotvassli, Citation2016b; Moe & Valstad, Citation2014; Toresen, Citation2014). New ideals of governance and reforms in the public sector have both led to changes in the conditions for child welfare leadership. Child welfare leaders have been given more responsibility for budgets, departments and staff (Shanks, Lundström, & Wiklund, Citation2015). This implies that leadership has to be exercised in new ways and adapted to new situations. Leadership skills are in increasing demand, and expectations towards leaders are clearer. In Norway, expectations and requirements for leadership in the child welfare service have been specified in a professional recommendation from the state level (The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs, Citation2017). It contains a clear expectation that the leadership should be professionalized.

Contradictory and competing demands are part of everyday life in many organizations, including child welfare. Leaders in the municipal child welfare service in Norway are responsible for the service’s strategic, professional and value-based platform, which can lead to a perception that demands and expectations work against each other (Agevall, Citation2000; Gaim & Wåhlin, Citation2016; Hood, Citation1991; Hood & Peters, Citation2004; Kirkhaug, Citation2015; Kvello & Moe, Citation2014; Pettersen & Solstad, Citation2014; Wällstedt & Almqvist, Citation2015). The intersection of demands and expectations can lead to paradoxical tensions (Knight & Paroutis, Citation2017). Paradox theory offers a way to understand and address the tensions that arise as a result of these conflicting demands and can supplement existing theory on leadership (Schad, Lewis, Raisch, & Smith, Citation2016).

The purpose of the article is firstly to identify the leadership challenges that municipal child welfare leaders face; secondly, to describe and explain these challenges in light of paradox theory; and thirdly, to contribute to an increased knowledge base on child welfare leadership. The problem at hand is twofold: What leadership challenges do municipal child welfare leaders face, and to what extent can paradox theory help us describe and explain these challenges?

There is an increased scope for the use of paradox theory for understanding both organizational tensions and leadership challenges (Schad, Lewis, & Smith, Citation2019). Research on paradoxes within organizations and management is to be found not only in management studies, but also in interdisciplinary social sciences writ large (Putnam, Fairhurst, & Banghart, Citation2016). Despite this, reviews by Schad et al. (Citation2016) and Heiberg Johansen (Citation2018) demonstrate that paradox theory has been applied to leadership in child welfare and social work to only a limited extent.

To date, there has been little research on the leadership of child welfare (Shanks et al., Citation2015; Toresen, Citation2014). The research that does exist focuses principally on child welfare leaders’ professional leadership and decision-making in child welfare issues (Falconer & Shardlow, Citation2018; Kvello & Moe, Citation2014; Moe & Gotvassli, Citation2016a, Citation2017; Nyathi, Citation2018). This research helps to underline how complex the field of child welfare is, and how challenging leadership of it can be.

The Norwegian child welfare services

The child welfare service in Norway is part of a publicly organized system of care that is often referred to as the Nordic welfare state model. Unlike the welfare states in continental Europe, the Nordic welfare state mainly provides the health and care services itself (Gunnarsdóttir, Citation2016; Hvinden, Citation2009). The child welfare service in Norway is organized into state and municipal components in which the most essential child welfare functions are a municipal responsibility. All municipalities must have a child welfare service that performs the day-to-day tasks required by the Child Welfare Act (Ministry of Children and Families, Citation2016). The service is responsible for targeted in-home child protection services for “at-risk” families in particular, predominantly given on a voluntary basis (e.g. kindergarten, counselling and economic assistance), out-of-home placements and approval of foster homes (Pösö, Skivenes, & Hestbæk, Citation2014). Out-of-home placement is used only as a last resort and when home-based assistance has proved to be insufficient. The Child Welfare Act regulates the child welfare service, as well as the measures available to assist children in need of protection. In Norway, the principles “the best interests of the child”, “the biological principle” and “the principle of “the least intrusive” form of intervention” are important guidelines in the child welfare legislation (Kristofersen, Citation2018; The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs, Citation2020).

Norway has a decentralized structure for child welfare services, and the municipalities have great autonomy both in the execution of the work and in the organization of the service. Due to the variation in both size of the municipality and how each municipality have organized the child welfare service, we thus find a variety of leadership structures and approaches to the delegation of functions (Moe & Gotvassli, Citation2016a). Over time there has been a transfer of responsibility and functions from the state level to the municipal (Oterholm, Citation2016). Regardless of municipal organization, the objective is that everyone should receive the same offering, irrespective of place of residence. This is a challenge to the municipal child welfare services and contributes towards making the leadership of child welfare complex and intricate. Child welfare leaders describe their lives as leaders as demanding, emotionally charged and unpredictable, with frequent shifts in focus. Colby Peters (Citation2018, p. 32) points out three elements that characterize leadership in this context. Leadership contains a powerful emotional aspect and is largely based on collaboration with others; also, leadership is guided by the service objective, which is to ensure individual and social welfare and security. It thus also deals with the implementation and follow-up of state and organizational instructions and guidelines (Popa, Citation2012). In this way, child welfare leaders are subject to conflicting pressures between differing normative requirements (Sullivan, Citation2016). The services provided are individualized and require a high degree of discretion, while at the same time having to be allocated and granted following current laws and regulations. Difficult prioritizations often have to be made, placing great demands on leaders. The combination of differing demands often appears contradictory and contributes to the perception of paradoxical tensions.

Theoretical framework—leadership seen through a paradox lens

The perception of a complex and changing environment has resulted in several organizational and leadership theories regarding complexity. According to complexity theory, organizations consist of many factors working in concert. The factors can be technological, structural, cultural, social and operational (Heiberg Johansen, Citation2018; Kirkhaug, Citation2015). Leadership is one of these factors, and the various factors interact with differing degrees of predictability. From a complexity perspective, leadership can be conceived of as a factor that both influences and is influenced by its changing surroundings. For this reason, leadership will be subject to constant change (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2018).

Within the literature on leadership, there has traditionally been a focus on the difference between administration and management. More recent literature on management has largely departed from this distinction and instead uses the term leadership (Crosby & Bryson, Citation2018, p. 1268). This encompasses the development and safeguarding of employees, putting the collegiate ahead of the individual, and taking into account all stakeholders (Crosby & Bryson, Citation2018; Kirkhaug, Citation2015). It has become more common to view leadership as an integrated function in which totality, balance, vision, philosophy and science assume a central place. Leaders should face all the challenges that arise when all primary stakeholders (service users, co-workers, and owners) are also taken into consideration, which is regarded as vital to ensuring legitimacy, balance and stability (Crosby & Bryson, Citation2018; Kirkhaug, Citation2015; Orazi, Turrini, & Valotti, Citation2013; Ospina, Citation2017). Thus, more recent approaches to leadership view it as a complex, paradoxical and situational function (Kirkhaug, Citation2015).

In this study, leadership in child welfare is viewed from a paradoxical perspective. Complexity theory is seen as a necessary basis for paradox theory. While complexity theory focuses on unpredictable and complex interactions between a variety of factors within organizations, paradox theory emphasizes that some contradictions exist simultaneously and persist over time (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011, p. 382). The paradox perspective emerged in the late 1970s and has since increased in scope because other perspectives do not sufficiently accommodate the increasing complexity of organization and leadership (Heiberg Johansen, Citation2018; Lewis & Smith, Citation2014; Schad et al., Citation2016; Schad et al., Citation2019; Smith & Lewis, Citation2011).

Paradoxes can occur at different organizational levels, such as conflicts between models of governance, objectives, or the contradictory ideals of leadership practices (Heiberg Johansen, Citation2018, p. 13). The paradoxes can be divided into four typologies (Jarzabkowski, Lê, & Van de Ven, Citation2013, pp. 247, 248; Lewis, Citation2000): the paradoxes of organizing, performing, belonging and learning.

The paradox of organizing has been identified as an ongoing tension of organizational integration and differentiation (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013). There will be boundaries between those inside and those outside the organization and through the marking of internal dividing lines. Tensions arise between structure and actions and between stability and change (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008). The paradoxes of organizing provide the framework for the other paradoxes. The challenge for leaders is to find the optimal organization in which one can benefit from the advantages while stemming the disadvantages of the tensions that arise.

The paradox of performing addresses tensions in demands and expectations. Leaders experience paradoxes related to execution and effort through conflicting roles and functions (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013; Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008; Smith & Lewis, Citation2011). There may be different expectations related to behaviour and results—that is, contradictions in what is to be achieved and how it is to be achieved. Within child welfare leadership, tensions may arise between the quality of the services provided and the time available to provide the service.

The paradox of belonging concerns contradictions in identity and relationships. The leader may experience tensions and contradictions between different groups both within and outside the organization, and the leader’s identity and belonging can be challenged. The ability to execute the leadership function will, therefore, be related to how the child welfare leader sees herself concerning the different groupings (Heiberg Johansen, Citation2018).

The paradox of learning deals with tensions in the perception of time. It is challenging to simultaneously stabilize and change the organization (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013). Often, managers have to juggle the demands for both a short-term and a long-term perspective on what one does. For child welfare leaders, time is a scarce resource (Olsvik & Saus, Citation2019), which can lead to one being more concerned about the short-term perspective than the organization’s long-term needs. The tensions between exploitation and exploration may emerge as a paradox.

The study focuses on the micro-level in leadership, in which the child welfare leader’s experiences of paradoxes and paradoxical tensions are investigated. Paradox scholars centre their analyses at one level, primarily the organizational level (Waldman, Putnam, Miron-Spektor, & Siegel, Citation2019). The paradoxes are experienced in leaders’ “everyday interactions” related to functions, and where roles and activities are often contradictory (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017). The paradoxes are concrete, and the leaders perceive them as tensions in thoughts and emotions. This means that they are mental conceptions and that what we perceive as contradictions are not necessarily so in reality (Kirkhaug, Citation2015).

The child welfare leaders are key actors in the formal structure of municipal child welfare, and play a crucial role in collaboration with other actors, such as health nurses and schools. This means that leaders have to navigate between differing expectations of other actors in and around the organization. They may, therefore, encounter role complexity and may perceive themselves as being pulled between directives from the national authority, the wishes of key stakeholders, and the perspectives of co-workers and collaborators (Heiberg Johansen, Citation2018, p. 103). Child welfare leaders may also experience role divergence in that different expectations can make leaders feel caught between conflicting demands.

Method

Data collection was conducted using semi-structural qualitative interviews. This method gives exploratory access to data (Justesen & Mik-Meyer, Citation2012), and allows for precise descriptions of the child welfare leaders’ everyday lives (Kvale, Citation2014). A hermeneutic-phenomenological perspective (King, Citation2004a) provides an opportunity to understand and describe the challenges that child welfare leaders face and what they perceive as paradoxes based on the contexts in which these arise and are performed (Kelly & Bakr Ibrahim, Citation1991). This is underpinned by the methodological foundation of paradox theory, which has a holistic approach with a phenomenological perspective (Lewis & Smith, Citation2014, pp. 141, 142). Leadership is regarded as context-dependent (Mintzberg, Citation2001) and thus emphasis is placed on the child welfare leader’s interpretation (Hollis, Citation2002) of his/her reality.

The sample consists of 20 municipal child welfare leaders, of which 18 are women and 2 men. The leaders are geographically located throughout the country and manage child welfare services that vary in size. The services are organized in different ways, and the size of the services varies in the number of employees and in the size of the population they serve. The smallest services serve a population of 5,500 inhabitants and the largest up to 80,000 inhabitants. Of the sample, 13 have formal leadership training in addition to formal education. Half of the leaders have less than five years of experience as child welfare leaders, five have 5–10 years of experience, and five have more than 10 years of experience ().

To cover a large geographical area and services with different size, the membership list of NOBO (Organization for Norwegian child welfare leaders) was used in the recruitment of informants. The membership list was available on the NOBOs website (Norsk barnevernlederorganisasjon, Citation2018). A total of 128 child welfare leaders were contacted by email. 8 replied that they did not want to participate. 5 emails returned as a result of invalid email addresses. 95 of our emails were not answered, nor after a reminder. The interviews were conducted in parallel with the recruitment of new informants. After 20 interviews, the interviews did not add new elements related to our research questions. We considered the data material as large enough, in line with Mason (Citation2018, pp. 62, 63) specification of the saturation point and of when data material is sufficiently large. This study is based on limited data material. The sample still covers the entire country and variation in the size of municipalities and services. Despite limitations, the study will provide insights and knowledge in the form of general trends about leaders’ perceived challenges and paradoxical tensions, which is a little-explored area.

The interviews were conducted during the period of July 2017–June 2018: eight of them during face-to-face interviews, and 12 during telephone interviews. Semi-structured qualitative interviews are usually conducted as face-to-face interviews, while telephone interviews are generally used in structured interviews or in situations where face-to-face interviews are not possible. Use of the telephone in semi-structured interviews is increasing (Ward, Gott, & Hoare, Citation2015), and it is not uncommon to find qualitative studies in which all or some of the interviews have been carried out by telephone (Irvine, Drew, & Sainsbury, Citation2012).

Norway is a country of great geographical distances. Telephone interviews were used for those farthest away to obtain a sample that reflects the variation in Norwegian municipal child welfare services.Footnote1 In addition to geographical diversification, this resulted in savings in both time and travel costs, which is highlighted as one of the advantages of telephone interviews (Irvine et al., Citation2012; Sturges & Hanrahan, Citation2004).

All leaders were contacted in advance, which is recommended if conducting semi-structured qualitative interviews over the telephone (Trier-Bieniek, Citation2012). The interviews lasted from 50–90 min, and there was no difference in length or detail between the face-to-face and the telephone interviews. The content of the interviews was not altered by the change of medium, something that is supported by comparisons made of the quality of data collected using both methods in the same study (Sturges & Hanrahan, Citation2004). However, combining the two interview types into one study requires an awareness of the differences. In the case of a telephone interview, a visual meeting will be absent. Such absence can limit our understanding and the possibility of a “natural” meeting, which is important for generating rich qualitative data (Novick, Citation2008). To preserve the credibility (Tracy, Citation2010) and consistency of the data (Olsen, Citation2003), “thick descriptions” that go into greater depth are sought (Sweet, Citation2002). Artefacts that do not require visual contacts, such as humour and silence, are preserved over the telephone, while nods and other artefacts that require a visual encounter naturally cease to apply in telephone interviews. The interviews were recorded and transcribed and sent to the leaders for review. From the printouts, it is not possible to distinguish the telephone interviews from the face-to-face interviews, and it is, therefore, difficult to point out any systematic bias in the data material that would be decisive for the analysis. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data and was conducted following ethical guidelines.

Thematic analyses have been used in the analysis of the data. This is a coding process that seeks to unearth the themes salient in a text at different levels (Attride-Sterling, Citation2001, p. 387). The study contains information from all participants on the same themes, which is a premise for theme-centred analyses (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, Citation2017). Deductive and inductive approaches are combined in the coding of the data (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006), which is recommended to avoid “overcoding” and to make the analyses more transparent, and simpler to complete (Overgaard & Bovin, Citation2014, p. 244). Nvivo was used to assist in the process of analysis. The use of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS), such as Nvivo, can lead to a reduction in the overall picture of theory, data and analysis process. Since the coding process can be done quickly, increased coding with the use of software in comparison to manual coding may occur (Welsch, Citation2002). Such programs should therefore only be considered as an aid (King, Citation2004b; Mason, Citation2018). The criticism that has been directed at theme-centred analysis is grounded in the failure to take an overall perspective (Nowell et al., Citation2017). To maintain a comprehensive understanding of the data material, the statements from each interview were compared with the interview as a whole, and analyses of the relationship between the themes were performed.

Results and analyses

This section presents the analysis of the data material. The analysis shows that the data material is twofold. It centres in part on what challenges the child welfare leaders face, and in part on whether the child welfare leaders experience these challenges as paradoxical tensions. When there is congruence in what the leaders perceive as challenges, it is referred to as the “child welfare leaders”. When there are differences in the leaders’ answers, these are described.

Contradictory elements in the child welfare leaders’ everyday practice

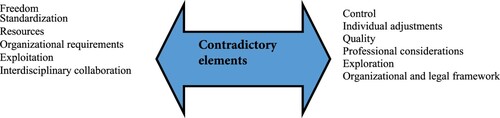

In the interviews with child welfare leaders, it emerges that their ordinary working lives consist of many contradictory considerations and that they experience a great deal of pressure from different quarters. Some say that they find themselves at the intersection of conflicting pressures between expectations and demands from employees, professional leaders, superiors and political groups. summarizes the contradictions to which child welfare leaders have to relate. We use the figure in further analysis.

Freedom and control

The child welfare leaders experience a great deal of freedom in the exercise of their leadership functions. 18 of 20 say that despite constraints on resources, they have managerial discretion to attend to operations in an acceptable manner. At the same time, they are experiencing greater control via increased requirements for reporting and documentation, as well as an increased focus on the service from national authorities, agencies with which they cooperate, and wider society. The mandate forms part of the framework for the child welfare leaders’ managerial discretion. The leaders’ main emphasis is that they have a clear mandate for the job as child welfare leader. Only 2 leaders considered the mandate as unclear. They highlighted that in the administrative part of the position it is unclear what the mandate entails, and believe this is because the administrative part of the job has grown without clarifying what the responsibilities of the leader are. When asked whether the child welfare leaders can attend to their mandate, the response is divided. Half of the leaders say that they can. Half say that they are only capable of fulfilling part of the mandate, at the same time pointing out some of the challenges that make it difficult to adequately fulfil the mandate. Lack of time means that they cannot perform all the functions properly. Broader functions, an increase in the number of concern reports and complex issues, growing expectations and increased requirements for knowledge and competence all render it challenging to fulfil the mandate.

Standardization and individual adjustments

All the leaders are experiencing an increasing demand for standardization in the form of manuals and national programs in the work with children and their families. It is still expected that individual adjustments are made. In the work with the staff, situation-based leadership is expected to be arranged for each staff member to the greatest degree possible. Having to make individual adjustments while fulfilling expectations of an efficient service is perceived as a contradiction.

Resources and quality

The child welfare managers talk about lack of resources or wrongly assembled resources in the form of time, initiatives, expertise, finances and personnel, while at the same time there is a need to satisfy differing quality requirements related to the profession, expertise, documentation and reliability. The child welfare leaders describe the increasing degree of national regulations and believe that they do not always have the necessary managerial discretion to fulfil these. The conflicting considerations they have to make are often perceived as contradictory.

Organizational requirements and professional considerations

All of the child welfare leaders highlights that organizational requirements often have to give way to professional considerations. Achieving ideal solutions for children and families, it is perceived that professional and professional considerations, as well as the safeguarding of staff, may constitute a contradiction to the resources available. It is often expected that one has clear answers, something that child welfare leaders find difficult to provide in a service characterized by discretion.

Exploitation and exploration

All of the leaders perceive the relationship between exploitation and exploration as challenging and contradictory. Requirements and expectations for work on development and transformation can be met to a lesser degree, and the focus on day-to-day tasks is what draws their attention. The leaders point out that it is challenging to make time for development because the service has increased in scope and the resources are not commensurate with the functions of the work. In the absence of resources, daily operations are prioritized over other tasks. The data material shows that the child welfare leaders are largely task-oriented when it comes to what the leaders devote their attention to. They are oriented towards functions and employees. Very few (3 out of 20) are oriented towards the work of transformation, and none towards strategy. Task orientation is displayed through statements from child welfare leaders that they aim to act properly, solve daily tasks, be gatekeepers to prevent poor decision-making, provide sufficient resources, plan, as well as create reliable structures and frameworks.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and organizational and legal framework

When it comes to demands for interdisciplinary and interagency cooperation, child welfare leaders experience both organizational and legal barriers. As an example, child welfare, health care and psychiatry are all governed by differing legislation. This is not perceived as a common offering, rather several offerings side by side. They describe a situation characterized by the duplication of effort, and one where it is difficult to achieve seamless coordination for children and young people. This is perceived as contradictory when seen against the demands and expectations for cooperation for the benefit of the child.

That which the child welfare leaders perceive as contradictory considerations are twofold. This is in part a question of contradictions related to how national demands and expectations can be satisfied in their municipal service, and in part of contradictions related to their expectations of the service. For example, some child welfare leaders want more room for discretion, while at the same time seeking clearer legislation and guidelines. Both are perceived as paradoxical tensions, and centre upon how the child welfare leaders perceive their situations as leaders and their scope for action to lead.

Discussion

Our analysis and shows that child welfare leaders perceive contradictory elements. The elements work together and trigger paradoxical tensions. This section contains a discussion on how we can understand the leadership challenges that child welfare leaders face based on paradox theory.

In each context, such as child welfare leadership, the identification of paradoxes depends on what actors perceive as contradictory yet interrelated elements (Keegan, Brandl, & Aust, Citation2019; Putnam et al., Citation2016). Child welfare leaders experience paradoxical tensions, and they face multiple—not just single—paradoxes. The paradoxes are experienced in connection with leaders’ job functions, in which roles and activities are often contradictory (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017). The paradoxes are particularly evident in an environment where scarcity occurs, where working life is characterized by change, or where we find ourselves in the context of a plurality of institutional logics, actors and demands. Logic can be defined as norms, values and incorporated ways of thinking that guide judgements and decisions (Blomgren & Waks, Citation2015), meaning that managers have to adhere to many different rules of play (Heiberg Johansen, Citation2018, p. 19; Smith & Lewis, Citation2011).

Drawing on the paradox typologies presented earlier, child welfare leaders experience conflicting and paradoxical situations related to the paradox of organizing, the paradox of performing and the paradox of learning. To a lesser degree, paradoxical tensions can be explained by the paradox of belonging. Under the paradox of organizing, there are contradictions between freedom and control, organizational requirements and professional considerations as well as interdisciplinary cooperation and organizational and legal frameworks. The child welfare leaders encounter the demands of different teams, both nationally and locally, and ordinary working life is characterized by plurality in institutional logics. National authorities emphasize different considerations than local partners and to some extent the child welfare leaders themselves do, and the leader has to deal with these often contradictory logics. There are expectations from national authorities that the leadership role of the child welfare leader is professionalized through the clarification of leaders’ understandings of roles, and the strengthening of leadership competence (The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs, Citation2017). It is expected that the child welfare leader has broad competence, practices effective leadership, as well as exercises professional discretion that is legally grounded. The child welfare leader has to be able to master different types of leadership: child welfare management, professional management, strategic management, personnel management, financial management and public management (The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs, Citation2017). Comparing this with the child welfare leaders’ description of their challenges, we see that this lays the groundwork for paradoxical tensions to arise.

Under the paradox of performing, discretion is challenged and paradoxical tensions are experienced between demands and expectations for standardization and individual adjustments. This applies both to assistance given to the individual child and family, and to employees. Paradoxical tensions arise when there are contradictions in demands and expectations both in how the work is performed and of the efforts invested in it. It is difficult to achieve a balance between execution and effort if, as a child welfare leader, one experiences scarcity in finances, staff, time and expertise.

The paradox of learning centres on tensions in the perception of time. Child welfare leaders have to concurrently stabilize and transform the organization. Turnover is a major problem in Norwegian child welfare services (Johansen, Citation2014), and child welfare leaders must, therefore, ensure that employees are recruited with the right expertise and at the same time prevent a large degree of turnover in positions. This is done through the supervision and follow-up of the employees. National authorities have pointed to a lack of expertise in Norwegian child welfare (The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs, Citation2016). Increasing and retaining the expertise in each municipal child welfare service requires that child welfare leaders have both a short-term and a long-term perspective on what they do. We see that with child welfare leaders, demands and expectations for both exploration and exploitation lead to paradoxical tensions, and they, therefore, prioritize exploitation over exploration. For many leaders, the expectations to work strategically with long-term operational, adaptive and development goals while at the same time making a pragmatic budgetary priority where children at greatest risk are ensured optimal assistance first (The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs, Citation2017, p. 10) can actuate paradoxical and contradictory situations. (text moved from the previous page). To deal with this situation, they prioritize short-term over long-term actions.

We are not able to identify child welfare leaders as perceiving paradoxes related to belonging—that is, tensions related to their identities as leaders or their belonging in the organization. This may be because the child welfare leaders have a strong affinity for their professions (Toresen, Citation2014, p. 292), and that one has specialized expertise in a demarcated area. In this way, both one’s identity and belonging are strengthened, and one appears confident in one’s role.

The child welfare leaders experience these paradoxes at different levels across level, time and phenomenon—such as fewer resources—but increased expectations of quality and impact. One of the consequences of paradoxical tensions is that doubts about professional discretion are formed. At the same time, child welfare leaders have to manage scarce resources, innovate and improve quality all while developing new core competencies and becoming better at utilizing existing expertise.

Coping with and working through paradoxes

The analysis shows that child welfare leaders perceive tensions between contradictory demands and deal with them in different ways. The perception of paradoxical tensions can trigger various responses; research has identified several different types, see for example Smith and Lewis (Citation2011) and Poole and Van de Ven (Citation1989). The responses are grouped based on whether they lead to negative or positive implications, such as defensive, avoidance-based or proactive responses (Keegan et al., Citation2019). Defensive responses provide short-term relief from paradoxical tensions; proactive responses try to deal with paradoxes on a longer-term basis (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017).

Paradox scholars focus on how alternative strategies for handling tensions can foster virtuous and avoid vicious cycles (Keegan et al., Citation2019). How child welfare leaders respond to tensions, and whether responses lead to virtuous and vicious cycles, is dependent on many factors. One of these factors is whether leaders are open to contradictions and avoid simplification, such as by choosing one or the other. Defensive responses to paradoxes foster vicious cycles. Vicious cycles can emerge when child welfare leaders simplify paradoxical tensions, prioritize either one or another contradictory element, and choose between them (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011).

The child welfare leaders’ reactions to paradoxes can be viewed as an interactive and dynamic process in which the leaders negotiate with themselves while experiencing the situation as paradoxical, and often switch from one reaction to another. The child welfare leader prioritizes exploitation over exploration—that is, the leader prioritizes one element and allows it to dominate or override the other element of the paradox. The child welfare leader is suppressing demands (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013). This is a defensive response. The child welfare leader faces the paradoxical tensions between professional considerations and organizational requirements by a splitting response.

That is, dealing with tensions by separating elements temporarily, such as dealing with one, then the other (Keegan et al., Citation2019). The professional considerations are first solved by the fact that the child welfare leaders are task-oriented and largely concerned with the process-active leadership functions. They are concerned with the procedural, such as coordinating, motivating and providing social support by follow-up and supervision of employees (Kirkhaug, Citation2019, pp. 83, 84). The principal focus seems to be the emphasis on professional leadership, in which guidelines are laid down for how the job should be performed and what professional standards should be maintained in the service.

Concerning most of the paradoxical tensions described by the child welfare leaders, they relate to both elements of the paradoxes and make it known that both elements are important, that they are mutually dependent, and that both must be accommodated. One such way of responding to paradoxical tensions is called adjusting, and is a proactive response (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013). To achieve virtuous cycles, one must effect a proactive response to paradoxical tensions. In this way, negative and paralysing emotions associated with paradoxical tensions can be overcome (Keegan et al., Citation2019).

In attempting to understand child welfare leadership from a paradoxical perspective, it is important to assume that a dynamic relationship exists between the conflicting forces that create paradoxical tensions. This requires a processual perspective so that we can understand how each element of the paradoxes continuously informs and defines the others. It is also important to understand what constitutes the sources of paradoxical tensions. Both structures and child welfare leaders’ perceptions are sources of paradoxical tension, and leaders may only experience these tensions under particular circumstances (Fairhurst et al., Citation2016). When child welfare leaders have to deal with paradoxes, it is a question of an on-going process of “coping with” or “working through” paradoxes. Awareness of paradoxical tensions helps leaders to focus on how their response is constructed “in everyday practice” (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017). Paradoxes can cause paralysis and indecision, and they can foster creativity and innovation. An important skill for the child welfare leader is therefore to practice paradoxical thinking. Paradoxical thinking contributes to complexity management rather than to complexity reduction. When the everyday working lives of leaders are complex, we often desire simplification, standardization and alignment (Nielsen et al., Citation2018). This is perceived as both easier to relate to and easier to control.

Concluding comments

This article identified challenges that leaders of Norwegian child welfare services face in their everyday practice. These are described and explained from a paradoxical perspective. The analyses show that child welfare leaders manage multiple, interrelated paradoxes. Child welfare leaders have to relate to ever-increasing complexity, both strategically and practically. Against the current situation in Norwegian child welfare, it can seem as though child welfare leaders prioritize professional considerations and standards over national organizational requirements for deadlines, manuals, requirements for documentation and procedures, and that they see that their value and professional standards are often difficult to reconcile with national bureaucratic demands.

Leadership contains dilemmas and paradoxes, and we see that the number of paradoxes has increased and that priorities and leadership decisions have a limited shelf life. Paradoxical tensions foster doubts about professional judgement. We are seeing this today in the contours of Norwegian child welfare. Professional judgement is being placed under the microscope and is framed by the introduction of requirements for expertise, more rules and procedures, the use of manuals, as well as growing requirements for documentation and control. Professional judgement is viewed from a bureaucratic understanding of knowledge (Bjørnebekk, Citation2010) in which the exercising of discretion is transformed into a technical exercise that is impersonal, cognitive and rational. This leads to paradoxical tensions for the child welfare leader, who largely exercises collective judgement, alongside his or her colleagues, in which personal, relational and situational factors play a role (Olsvik & Saus, Citation2019). The child welfare leaders point out that there is too much focus on doing things right rather than doing the right things. This contributes to reducing the leaders’ managerial discretion.

If we are to fully understand child welfare leadership, we need to see it from different angles, and then paradox theory can contribute with its approaches (Kirkhaug, Citation2015 Schad et al., Citation2016;). Paradox theory focuses on approaching paradoxes dynamically over time based on a recognition that such tensions never go away (Keegan et al., Citation2019). Such an approach would be able to give leaders awareness of and a tool to deal with the paradoxical tensions that they perceive. Yukl (Citation2013) emphasizes that leadership must be adapted to circumstances. This means that leadership skills must also be adapted to the circumstances, which can be challenging in a leader’s ordinary working day challenged by scarcity, change and a great diversity in institutional logics. Learning to live and thrive with paradoxes will be a vital skill of child welfare leaders. Despite the relatively low number of informants, we have demonstrated the relevance of paradox theory for understanding the leadership in child welfare. We recommend further research in this area.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bodil S. Olsvik

Bodil S. Olsvik is a Ph.D. student at Department of Child Welfare and Social Work, UiT—The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

Merete Saus

Dr Merete Saus is an associate professor at Department of Education, UiT—The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

Notes

1 We considered use of skype instead of telephone interview, but because of the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (The European Parliament, Citation2016), recording of personally identifiable material such as audio and video files became more strictly regulated. Both national guidelines (NSD- Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Citation2020) and policy at UiT The Arctic University of Norway (Citation2020) do not allow devices (e.g. mobile phones and laptops) connected to the network to be used for recording sound or image. We used a speaker telephone and the interviews were recorded on a recorder with an external memory card.

References

- Agevall, L. (2000). Hur välfärd organiseras—Spelar det någon roll? Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 103(1), 18–42.

- Attride-Sterling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Bjørnebekk, W. (2010). Utfordringer for utviklingen av et kunnskapsbasert barnevern. Fontene Forskning, 1/10, 91–103. Retrieved from http://fonteneforskning.no/forskningsartikler/utfordringer-for-utviklingen-av-et-kunnskapsbasert-barnevern-6.19.264804.9be01ebe50

- Blomgren, M., & Waks, C. (2015). Coping with contradictions: Hybrid professionals managing institutional complexity. Journal of Professions and Organizations, 2(1), 78–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/jou010

- Colby Peters, S. (2018). Defining social work leadership: A theoretical and conceptual review and analysis. Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(1), 31–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2017.1300877

- Crosby, B. C., & Bryson, J. M. (2018). Why leadership of public leadership research matters: And what to do about it. Public Management Review, 20(9), 1265–1286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1348731

- The European Parliament. (2016). General Data Protection Regulation. ELI: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

- Fairhurst, G. T., Smith, W. K., Banghart, S., Lewis, M. W., Putnam, L. L., Raisch, S., & Schad, J. (2016). Diverging and converging: Integrative insights on a paradox meta-perspective. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 173–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1162423

- Falconer, R., & Shardlow, S. M. (2018). Comparing child protection decision-making in England and Finland: Supervised or supported judgement? Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(2), 111–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1438996

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Quality Methods, 5(1), 80–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Gaim, M., & Wåhlin, N. (2016). In search of a creative space: A conceptual framework of synthesizing paradoxical tensions. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 32(1), 33–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.12.002

- Gunnarsdóttir, H. M. (2016). Autonomy and emotion management. Middle managers in welfare professions during radical organizational change. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 6(S1), 87–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.19154/njwls.v6i1.4887

- Hansen, A. (2019). Sjokkangrep mot norsk barnevern. Dagbladet. Retrieved from https://www.dagbladet.no/nyheter/sjokkangrep-mot-norsk-barnevern/71363829

- Heiberg Johansen, J. (2018). Paradoksledelse. Jagten på værdi i kompleksitet København: Jurist- og økonomiforbundets forlag.

- Hollis, M. (2002). The philosophy of social science: An introduction (Rev. and updated ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Hood, C., & Peters, G. (2004). The middle aging of new public management: Into the age of paradox? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (JPART), 14(3), 267–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muh019

- Hvinden, B. (2009). Den nordiske velferdsmodellen: Likhet, trygghet - og margenalisering? Sosiologi i dag, 1, 11–36.

- Irvine, A., Drew, P., & Sainsbury, R. (2012). ‘Am I not answering your questions properly?’ clarification, adequacy and responsiveness in semi-structured telephone and face-to-face interviews. Qualitative Research, 13(1), 87–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112439086

- Jarzabkowski, P., & Lê, J. K. (2017). We have To Do this and that? You must be joking: Constructing and responding to paradox through Humor. Organization Studies, 38(3-4), 433–462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640846

- Jarzabkowski, P., Lê, J. K., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Responding to competing strategic demands: How organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strategic Organization, 11(3), 245–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127013481016

- Johansen, I. (2014). Turnover i det kommunale barnevernet SSB Rapport nr. 18/2014. Oslo: Statistisk Sentralbyrå.

- Justesen, L., & Mik-Meyer, N. (2012). Qualitative research methods in organisation studies. København: Gyldendal.

- Keegan, A., Brandl, J., & Aust, I. (2019). Handling tensions in human resource management: Insights from paradox theory. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(2), 79–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002218810312

- Kelly, J., & Bakr Ibrahim, A. (1991). Executive behavior: Its facts, fictions, and paradigms. Business Horizons, 34(2), doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90063-2

- King, N. (2004a). Using interviews in qualitative research. In C. Cassell, & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (Vol. 2, pp. 11–23). London: SAGE Publications.

- King, N. (2004b). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell, & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (Vol. 2, pp. 256–270). London: SAGE Publications.

- Kirkhaug, R. (2015). Lederskap. Person og funksjon. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Kirkhaug, R. (2019). Lederskap. Person og funksjon (2nd ed.). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Knight, E., & Paroutis, S. (2017). Becoming salient: The TMT leader’s role in shaping the interpretive context of paradoxical tensions. Organization Studies, 38(3-4), 403–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640844

- Kristofersen, L. B. (2018). Regionale variasjoner i barneverntiltak: Et gammelt problem i ny drakt? Fontene Forskning, 11(1), 56–71.

- Kvale, S. (2014). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative interviewing (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Kvello, Ø, & Moe, T. (2014). Barnevernledelse. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. The Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 760–776. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/259204

- Lewis, M. W., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Paradox as a metatheoretical perspective: Sharpening the focus and widening the scope. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(2), 127–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886314522322

- Lüscher, L. S., & Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: Working through paradox. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2), 221–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2008.31767217

- Mason, J. (2018). Qualitative researching (3rd ed.). E-reader version. Retrieved from https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/#/books/9781526422019/

- McFadden, P., Campbell, A., & Taylor, B. (2014). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1546–1563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct210

- Ministry of Children and Families. (2016). The Child Welfare Act. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/the-child-welfare-act/id448398/

- Mintzberg, H. (2001). Managing exceptionally. Organization Science, 12(6), 759–771. doi: https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.6.759.10081

- Moe, T., & Gotvassli, K-Å. (2016a). Ledelse og beslutningspraksis. In Ø Christiansen, & B. H. Kojan (Eds.), Belutninger i barnevernet (pp. 195–214). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Moe, T., & Gotvassli, K-Å. (2016b). Å lede til barns beste - Hvordan kan lederutdanning i barnevernet svare på barnevernets behov for økt lederkompetanse? Tidsskriftet Norges Barnevern, 92(03-04), 166–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-1838-2016-03-04-03

- Moe, T., & Gotvassli, K-Å. (2017). Barnevernledelse - skjønnsutøvelse og ansvarliggjøring. In O. J. Andersen, T. Moldenæs, & H. Torsteinsen (Eds.), Ledelse og skjønnsutøvelse (pp. 132–155). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Moe, T., & Valstad, S. J. (2014). Lederutfordringer, lederansvar og en modell for barnevernledelse. In Ø Kvello, & T. Moe (Eds.), Barnevernledelse (pp. 22–40). Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Nielsen, R. K., Hjalager, A.-M., Holt Larsen, H., Bévort, F., Duus Henriksen, T., & Vikkelsø, S. (Eds.). (2018). Ledelsesdilemmaer - og kunsten at navigere i moderne ledelse. København: Djøf forlag.

- Norsk barnevernlederorganisasjon. (2018, April 13). Medlemsliste. http://www.barnevernledere.no/medlemmer-nobo/#medlemsliste/?view_25_page=1

- The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs. (2016). Kartlegging av kompetansebehov i det kommunale barnevernet. Oslo.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs. (2017). Operativ ledelse i barnevernet. Beskrivelse av krav og forventninger. Oslo.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Children; Youth and Family Affairs. (2020). Role and structure of the Norwegian child welfare services. Retrieved from https://bufdir.no/en/English_start_page/The_Norwegian_Child_Welfare_Services/role_of_the_norwegian_child_welfare_services/

- Novick, G. (2008). Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Research in Nursing & Health, 31, 391–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20259

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data. (2020, March 4). NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data. https://nsd.no/nsd/english/index.html

- Nyathi, N. (2018). Child protection decision-making: Social workers’ perceptions. Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(2), 189–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1448768

- Olsen, H. (2003). Kvalitative analyser og kvalitetssikring. Tendenser i engelsksproget og skandinavisk metodelitteratur. Sociologisk Forskning, 40(1), 68–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.37062/sf.40.19395

- Olsvik, B. S., & Saus, M. (2019). Skjønn i praktisk barnevernledelse. Kollektiv prosess med organisatoriske begrensninger. Norges barnevern (4).

- Orazi, D. C., Turrini, A., & Valotti, G. (2013). Public sector leadership: New perspectives for research and practice. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 79(3), 486–504. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852313489945

- Ospina, S. M. (2017). Collective leadership and context in public administration: Bridging public leadership research and leadership studies. Public Administration Review, 77(2), 275–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12706

- Oterholm, I. (2016). Kompetanse til arbeid i barneverntjenesten - ulike aktørers synspunkter. Norges barnevern, 93(3-4), 146–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-1838-2016-03-04-02

- Overgaard, D., & Bovin, J. S. (2014). Hvordan bliver forskning i sygepleje bedre med NVivo? Nordisk sykeplejeforskning, 4(3), 241–250. doi: https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1892-2686-2014-03-06

- Pettersen, I. J., & Solstad, E. (2014). Managerialism and profession-based logic: The use of accounting information in changing hospitals. Financial Accountability & Management, 30, 4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12043

- Poole, M. S., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1989). Using paradox to build management and organization theories. (Special Forum on Theory Building). Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 562. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/258559

- Popa, A. B. (2012). A quantitative analysis of perceived leadership practices in Child Welfare Organizations. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 6(5), 636–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2012.723974

- Pösö, T., Skivenes, M., & Hestbæk, A.-D. (2014). Child protection systems within the Danish, Finnish and Norwegian welfare states—time for a child centric approach? European Journal of Social Work, 17(4), 475–490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2013.829802

- Putnam, L. L., Fairhurst, G. T., & Banghart, S. (2016). Contradictions, dialectics, and paradoxes in organizations: A constitutive approach. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 65–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1162421

- Schad, J., Lewis, M. W., Raisch, S., & Smith, W. K. (2016). Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 5–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1162422

- Schad, J., Lewis, M. W., & Smith, W. K. (2019). Quo vadis, paradox? Centripetal and centrifugal forces in theory development. Strategic Organization, 17(1), 107–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127018786218

- Shanks, E., Lundström, T., & Wiklund, S. (2015). Middle managers in social work: Professional identity and management in a marketised welfare state. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(6), 1871–1887. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu061

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. The Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2011.59330958

- Sturges, J. E., & Hanrahan, K. J. (2004). Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qualitative Research, 4(1), 107–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104041110

- Sullivan, W. P. (2016). Leadership in the social work: Where are we? Journal of Social Work Education, 52(sup1), 51–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1174644

- Sweet, L. (2002). Telephone interviewing: Is it compatible with interpretive phenomenological research? Contemporary Nurse, 12(1), 58–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.12.1.58

- Toresen, G. (2014). Barnevernlederen - et kommunalt kinderegg? In T. Moe, & Ø Kvello (Eds.), Barnevernledelse (pp. 286–293). Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Totland, T. W. (2019). Hvordan havnet 26 norske barnevernssaker i Strasbourg?. Aftenposten. Retrieved from https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kronikk/i/rAXmgR/hvordan-havnet-26-norske-barnevernssaker-i-strasbourg-thea-w-totland

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “Big-Tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Trier-Bieniek, A. (2012). Framing the telephone interview as a participant-centred tool for qualitative research: A methodological discussion. Qualitative Research, 12(6), 630–644. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112439005

- Uhl-Bien, M., & Arena, M. (2018). Leadership for organizational adaptability: A theoretical synthesis and integrative framework. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 89–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.009

- UiT The Arctic University of Norway. (2020). Retningslinjer for personvern i forskings- og studentprosjekt. Retrived from https://uit.no/forskning/art?dim=179056&p_document_id=604029

- Waldman, D. A., Putnam, L. L., Miron-Spektor, E., & Siegel, D. (2019). The role of paradox theory in decision making and management research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.04.006

- Ward, K., Gott, M., & Hoare, K. (2015). Participants’ views of telephone interviews within a grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(12), 2775–2785. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12748

- Wällstedt, N., & Almqvist, R. (2015). From ‘either or’ to ‘both and’: Organisational management in the aftermath of NPM. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 19(2), 7–25.

- Welsch, E. (2002). Dealing with data: Using NVivo in the qualitative data analysis process. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2), Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/865/1880&q=nvivo+manual&sa=x&ei=zah_t5pqoyubhqfe9swgbq&ved=0cc4qfjaj

- Yukl, G. A. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed., Global ed. ed.). Essex: Pearson.