ABSTRACT

Background

Cerebral palsy (CP) is one of the most common childhood disorders requiring comprehensive and coordinated care over time. This study aimed to add knowledge about health, educational and social services received by children and families throughout early childhood, with special attention on coordination services provided.

Methods

The study was designed as a prospective longitudinal cohort study utilising data from two CP registers in Norway. Fifty-seven families with children with CP aged 12–57 months with different levels of mobility limitations classified according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System were included. Services were mapped via the parent-reported Habilitation Service questionnaire at least three times. The relationships between mobility limitations and the number of services and type of coordination services were explored using a linear mixed model and Chi Square/Fischer’s exact test. Continuity in the provision of services was explored by identifying interruptions in the longitudinal reports on services received.

Results

Most of the families received both health, education and social services as well as some types of coordination services. The number and type of services received varied to some extent depending on the children’s mobility limitations. Multidisciplinary team and an individual service plan were widespread coordination services, while having a service coordinator was most common among the families raising a child with severe mobility limitations. Interruptions in the longitudinal reporting of services were frequent, especially in the receiving of coordination services.

Conclusion

The comprehensiveness of the provided services emphasises the need for coordination services. The relatively low proportion of families provided with a coordinator and the frequent interruptions in the longitudinal reports on services indicate some persistent challenges in the service system.

Introduction

Improving the quality of care for children with complex disabilities and their families is a persistent objective in rehabilitation services. Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common childhood motor disorder, characterised by impairments in movement and posture that lead to varying degrees of mobility limitations (Rosenbaum, Paneth, Leviton, Goldstein, & Bax, Citation2007). Several additional conditions are commonly seen, including disturbances of sensation, cognition, communication and behaviour, as well as seizure disorders and musculoskeletal complications (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2007). This implies that most children with CP require long-term multidisciplinary care involving both health and educational services. The family holds a unique position in the follow-up of young children with disabilities, and in line with a family-centred approach, child-directed services are expected to be accompanied by services aimed at supporting the entire family.

When the multiple services provided for children with disabilities exceed organisational boundaries, there will be a need for service coordination in order to effectively provide family-centred care (G. King & Chiarello, Citation2014) and ensure coherence and continuity in the provision of services (Reid et al., Citation2002). In Norway, two types of coordination services have been established as statutory for everyone in need of coordinated long-term services: being entitled to a service coordinator and an individual service plan (ISP) (Ministry of Health and Care Services, Citation2011). A service coordinator plays a key role in childhood rehabilitation by helping families navigate a complex service system (Trute, Citation2007), and he or she is assigned the responsibility for the child’s ISP (Ministry of Health and Care Services, Citation2011). A well-functioning ISP has proven to have the potential to increase empowerment (Holum, Citation2012) and participation in collaborative processes (Hedberg et al., Citation2018; Holum, Citation2012) and may provide an efficient way of working in multidisciplinary teams (Hedberg et al., Citation2018). Such teams have long traditions in Norway beyond statutory services and have been associated with high levels of parental empowerment (Kalleson et al., Citation2019). However, the extent to which families raising a child with CP receive these services and the way in which the type of coordination service relates to child age and mobility have not been previously explored.

Another important aspect of quality of care is the sustained continuity of services over time (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Even though there is general agreement that continuity is a quality indicator for rehabilitation services (World Health Organization, Citation2018), there is a striking lack of studies exploring the provision of services for children with disabilities and their families within a longitudinal perspective.

As far as we know, this is the first study that systematically maps health, education, social and coordination services provided to children with disabilities and their families over time. The study aims to increase knowledge about the comprehensiveness, coordination and continuity of care for children with CP and their families during early childhood. Three specific research questions are addressed:

How comprehensive are the child- and family-directed services that young children with CP and their families receive, and is there a relationship between the number of services received and the child’s age and the severity of mobility limitations?

What kind of coordination services do the families receive, and does the type of service differ based on the severity of the child’s mobility limitations?

How continuous is the provision of services during early childhood?

Methods

Study Design and Participants

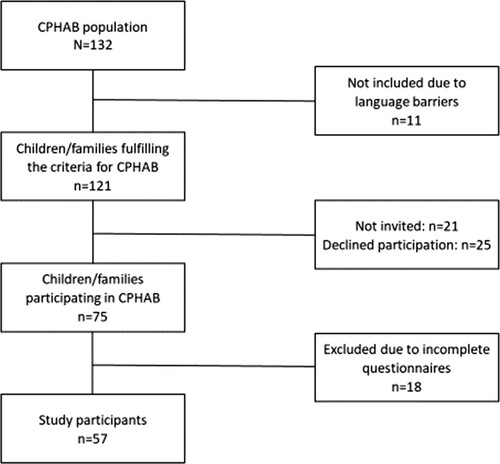

The study was designed as a prospective longitudinal cohort study based on registry data from two CP registries in Norway: the Cerebral Palsy Follow-up Program (CPOP) and Habilitation Trajectories, Interventions and Services for Young Children with CP (CPHAB). The CPOP is an ongoing national registry monitoring motor function and related interventions, and CPHAB was developed as an additional research registry conducted as a project from 2012 to 2016. It included parent-report questionnaires mapping extended child functioning, aspects of the family situation and the child- and family-directed services received. The inclusion criteria of CPHAB, and thus this study, were children with CP who were four years or younger when registered for the first time in the CPOP between January 2012 and December 2014, as well as parents capable of answering questions in Norwegian or English. Thirteen of the twenty-one pediatric rehabilitation units in Norway participated in the CPHAB project, which represented small, medium and large units spread over large parts of the country. A total of 132 children were registered in these units during the inclusion period of CPHAB. Of these, eleven families were excluded due to language barriers. Twenty-one families were not invited to participate in CPHAB, mainly due to a lack of resources at the rehabilitation units. Twenty-five families declined participation, and 18 families were excluded from the present study due to returning incomplete questionnaires or completing fewer than three assessments. Ultimately, 57 families were included in the study (see ). The families completed the CPHAB questionnaires in conjunction with their child’s regular follow-up at the rehabilitation units twice a year during the first two years of follow-up, and thereafter once or twice a year according to the families’ own preferences.

Questionnaires

Child characteristics, including age, subtype of CP and gross motor functioning, were retrieved from the CPOP registry. The subtypes of CP were spastic (unilateral or bilateral), dyskinetic and ataxic (Cans, Citation2000). Gross motor functioning was classified according to the five levels of the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) (Palisano et al., Citation1997), where level I represents the least severe mobility limitations and level V represents the most severe limitations. According to the GMFCS children at level I are expected to be able to walk without limitations, children at GMFCS level II will be able to walk in most settings, but with some limitations for instance on uneven surfaces and in crowds, children at level III may walk with a hand-held mobility device and prefer to use a wheelchair or powered mobility outdoor and in the community, at level IV children use wheeled mobility in most settings, while children at level V have severely limited self-mobility and a need for extensive help in most areas. The GMFCS has demonstrated good reliability, predictive validity and stability (Alriksson-Schmidt et al., Citation2017; Palisano et al., Citation2000; Wood & Rosenbaum, Citation2000).

Family concerns about their financial situations and housing and information about children attending kindergarten were retrieved from the Norwegian version of the “Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms” questionnaire (Taylor et al., Citation1986) included in the CPHAB registry.

Information about services received was retrieved from the Habilitation Service questionnaire (HabServ) included in the CPHAB registry. This questionnaire has previously been used in four studies (Kalleson et al., Citation2019; Klevberg et al., Citation2017; Myrhaug et al., Citation2016; Myrhaug & Østensjø, Citation2014). In the present study, parental reports on the child- and family-directed services received in the preceding six months were utilised. A description of the Norwegian social services and benefits included in the questionnaire is provided in .

Table 1. Overview of social services and benefits for families raising a child with chronic illness or disability.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Descriptive statistics were compiled for the relevant child characteristics and aspects of the family situation. The number and percentage of families receiving each of the included child- and family-directed services and benefits during the project period were calculated. Due to a small number of families receiving personal assistant (n = 3) and support contact (n = 1), these services were merged into the category “respite care services”, together with respite care home. A linear mixed model was used to explore the relationships between the number of services reported at each assessment and the child’s age and mobility limitations, which could be grouped as mild (GMFCS level I), moderate (GMFCS levels II and III) or severe (GMFCS levels IV and V).

The number and percentage of families receiving each of the three coordination services, coordinator, ISP and multidisciplinary team, were calculated. The relationships between the type of coordination service received and the child’s mobility limitations were explored by performing a Chi-Square test for independence and Fischer’s exact test.

Most services and benefits were expected to remain continuous throughout preschool age. When a previously received service or benefit was not reported by the parents on the following assessment(s), this was identified as an interruption. For each of the services and benefits for which continuity was expected, the number and percentage of participants with interruptions in their follow-ups were calculated. Intensive rehabilitation programmes; parent training/courses; and some financial benefits, such as training allowances, car subsidies, and housing grants, were all expected to be periodic in nature and were, in consequence, excluded from these analyses.

Results

Participating families completed the questionnaires between three and six times (median four) within a time period of 12–43 months (median 27 months). shows that the child’s age at the first assessment ranged from 12 to 57 months (median 27). Almost half of the children was classified at the GMFCS level I, which indicates the least restricted mobility, while the functioning of the remainder of the children was distributed across GMFCS levels II–V. The number of additional impairments ranged from zero to seven, with about half of the children having at least one additional impairment. All children except one were attending kindergarten at least three days per week. More than one-third of the families reported financial concerns, and almost half of them reported concerns about their housing situation during the child’s early years. Thirty-two families (56%) reported having concerns about either their financial situation or housing at least once during their children’s early years.

Table 2. Child characteristics and family situation.

Child-directed and Family-directed Services Received

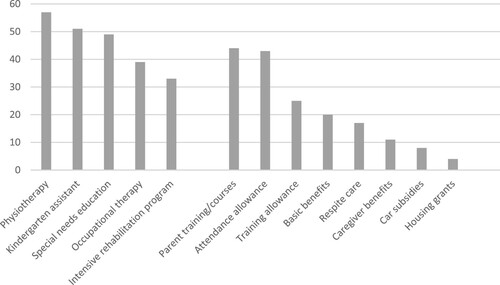

Regarding child-directed services, all the children reported receiving physiotherapy (PT), the great majority received help from a kindergarten assistant and/or special education teacher and about two-thirds received occupational therapy (OT). More than half of the children attended intensive rehabilitation programmes during their early years (see ).

Figure 2. Number of families receiving child- and family-directed services and benefits during early childhood.

Among family-directed services, the most common services were parent training and courses, which were received by more than three-quarters of the parents during the children’s early years. The training and courses were centred around the CP diagnosis and its consequences, child-directed interventions (motor training, play and stimulation, augmentative/supplementary communication), working processes (goal setting, ISP) and family issues (parenting, rights of families with a disabled child). Among potential financial benefits, an attendance allowance was the most frequently reported service, followed by a training allowance and basic benefits. Less than one-third of the families received respite care services, and only a small minority received caregiver benefits, car subsidies, or housing grants.

In total, 49 out of the 57 participating families (86%) received both child- and family-directed services, while eight families received only child-directed services during the child’s early years. Number of services and benefits received in the preceding six months ranged from zero to fourteen per assessment, with an average of 5.6 (SD 2.7). No association was found between the number of services received and the child’s age (see ). In contrast, the results showed that child mobility was associated with the number of services provided. Families raising a child classified at GMFCS level I (least limitations) received significantly fewer services than families having a child with moderate (GMFCS levels II–III; p = 0.02) and severe mobility limitations (GMFCS levels IV–V; p = 0.00). Post-hoc analyses setting families with children classified with the most severe mobility limitations (GMFCS levels IV–V) as redundant revealed no statistically significant differences between this group and the group of families raising children with moderate mobility limitations (GMFCS levels II–III; p > 0.05).

Table 3. Relationship between number of services received and the child’s age and GMFCS level.

Coordination Services

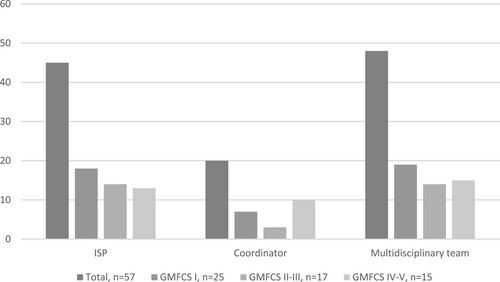

In total, 52 out of 57 families (91%) reported receiving one or more coordination services. Having a multidisciplinary support team and an ISP were the most widespread type of coordination services and were received by about 80% of the families, while only about one-third reported having a service coordinator (see ). Eighteen families (31%) received all three types of coordination services, 25 families (44%) received a combination of a multidisciplinary team and an ISP, nine families (16%) received only a multidisciplinary team or an ISP as the only coordination service and five families (9%) received none of the services.

The families receiving an ISP and a multidisciplinary support team were quite evenly distributed across the children’s mobility levels. Fischer’s exact test indicated no significant associations between the child’s mobility limitations and families receiving an ISP (p = 0.55) or multidisciplinary team (p = 0.12). Regarding having a service coordinator, however, a Chi-Square test for independence revealed significant association between the child’s mobility limitations (classified according to GMFCS levels) and having a coordinator (p = 0.01). Two-thirds of the families raising children with the most severe mobility limitations (GMFCS levels IV–V) reported having a coordinator, while less than one-third of the families with a child classified with less severe limitations (GMFCS levels I, II or III) reported the same.

Interruptions in the Continuity of Services and Benefits

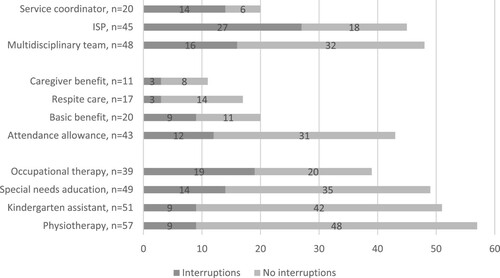

Interruptions in coordination services were widespread among those having a service coordinator (70% of the families) and an ISP (60%), whereas they were less frequently identified in those receiving a multidisciplinary support team (33%). Regarding family-directed services and benefits, the interruption rate was highest among those receiving basic benefits (45%). Among the child-directed services, interruptions were most commonly identified among those receiving OT (almost half of the families) and special education (more than one-fourth). Regarding family-directed services and benefits, the interruption rate was highest in those receiving basic benefits (45%) ().

Discussion

This study confirms that children with CP are supported by a welfare system recognising the complex needs of children and families. The comprehensiveness of services corresponds well with a bio-ecological perspective on child development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) and a family-centered approach to childhood rehabilitation (Dempsey & Keen, Citation2008). However, some challenges were revealed regarding the coordination of services and longitudinal continuity in service provision.

Most families reported receiving a variety of child- and family-directed services. However, the number of services received varied greatly. Families raising children with minor mobility limitations (GMFCS I) received significantly fewer services than families raising children with moderate (GMFCS II–III) or severe limitations (GMFCS IV–V). This may indicate that the burden of caring for a child with mild mobility limitations does not differ much from of care what is expected for all families raising young children, whereas more extra services are needed when the child's disability is more pronounced. The severity of mobility limitations is found to be associated with several additional impairments, such as disturbances of cognition, vision, hearing, speech, and epilepsy (Delacy & Reid, Citation2016), which may reinforce the need for more comprehensive services among families raising a child with mobility limitations classified at GMFCS levels II–V compared with those at level I. However, the lack of difference in the number of services received between children with moderate and severe mobility impairment indicates that service needs are affected by more than motor function. Thus, the interplay between motor functioning and additional impairments and aspects of the family situation must be considered when services are planned and provided in a rehabilitation context.

The finding that there was no significant association between the number of services received and the child’s age indicates that the need for services persists through the child’s early years. While children without disabilities increase their mobility and independence relatively quickly, this is not the case for children with complex disabilities. This difference may explain why some children with disabilities will continue to need more extensive help in everyday situations in a long-term perspective.

Regarding child-directed services, all children received physiotherapy (PT), the great majority reported receiving special education and a kindergarten assistant and more than two-thirds received occupational therapy (OT). This finding highlights the need for cooperation across organisational boundaries in order to efficiently promote child development, learning and well-being.

When it comes to family-directed services, training and courses were the most widespread and were received by more than three-quarters of the families. This corresponds well with a family-centred approach in pediatric rehabilitation, focusing on parent competence and involvement in interventions (S. King et al., Citation2004). Almost as widespread was the receipt of the financial benefit known as an attendance allowance, which aims to compensate for the need for extra care and supervision due to the child’s limitations in performing everyday activities and expectations of parental involvement in different interventions. The finding draws attention to the burden of raising a child with a disability like CP. As many as one-third of the parents received respite care, which indicates that even families with a young child must be relieved of their care situations sometimes.

Although some family-directed services appear to be quite widespread, it is worth noting that the percentage of families receiving some of the available financial benefits was low. The most striking example was the low number of families receiving housing grants, especially considering that almost half of the families reported concerns about their housing. Whether this is due to lack of information or an application being rejected could not be revealed by the study. It has been documented that a large percentage of municipalities do not offer housing grants, even if they have been allocated funds by the Norwegian State Housing Bank (Proba Research, Citation2014). Housing grant in Norway is a means-tested benefit based on an assessment of the family’s overall financial situation. In Sweden, where subsidies for housing adaptations are right-based instead of means-tested, it seems that such services are more widespread in use (Proba Research, Citation2014). In any case, the frequent reporting of concerns about finances and housing during the child’s early years emphasises the need for social services to support and strengthen parents in caring for their child.

The multiple services involved in caretaking for children with CP and their families highlight the need for coordination services to support collaboration among service providers within and across organisational units (Reid et al., Citation2002). The coordination of services is considered a prerequisite for providing effective family-centred care (G. King & Chiarello, Citation2014) and has been a prioritised area of health policy in Norway for nearly two decades (Ringard et al., Citation2013). This is reflected in the study, revealing that most families receive one or more types of coordination services, independent of the severity of the child’s mobility limitations. However, compared to having an ISP or a multidisciplinary team (about 80%), being assigned a coordinator is far less widespread (35%). This difference is notable because the coordinator is assigned the responsibility for the planning and follow-up for the ISP (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2015). The discrepancy between reporting having a coordinator and the other types of coordinating services may be substantial; however, it could also be seen an under-reporting due to unclear boundaries and overlapping roles, for instance, when the child’s physiotherapist also holds the role of coordinator (Appleton et al., Citation1997), as has been identified as a problem in previous studies (Hannigan et al., Citation2018; Alve et al., Citation2013; Nilsen & Jensen, Citation2012).

In contrast to having a multidisciplinary team and an ISP, being assigned a service coordinator was significantly related to the child’s mobility limitation severity. Two-thirds of families raising children with the most severe limitations (GMFCS IV–V) reported having a coordinator, as compared with less than one-third of the families raising children with mild to moderate limitations (GMFCS I–III). This indicates a more pronounced need for a dedicated person to help families navigate the service system when the child’s motor limitations are extensive, especially given the relationship between the severity of mobility limitations and the number of additional impairments (Delacy & Reid, Citation2016).

Another important aspect of coherent and integrated care is sustained continuity in service provision over time (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Some rehabilitation services included in the study were expected to be periodic during early childhood, such as an intensive rehabilitation programme, parental training and grants for the current home or car. Other services were expected to be provided more or less continually. Among those, relatively few interruptions were identified in PT and kindergarten assistant, while interruptions were more frequently seen for OT and special education services. The interruptions may be explained by planned periodic involvement, and they thus do not necessarily represent a problem or a challenge in the service system. However, previous research indicates that continuity in the provision of therapies seems to be the preferred service model from a parental perspective (Beresford et al., Citation2018).

Frequent interruptions were also identified for several of the family-directed services and benefits. As Demiri and Gundersen (Citation2016) have documented in a review of the familieś experiences with health and social services in Norway, there are several challenges associated with the process of gaining access to services, such as the need for repeated applications. From the parents’ perspective, repeated applications were perceived as both time-consuming and demanding, and expressed as an ongoing struggle (Demiri & Gundersen, Citation2016). Such negative experiences may have prevented some families from applying for social services and benefits on some occasions.

Interruptions were surprisingly widespread among coordination services, being identified in one-third of the families with a multidisciplinary support team, more than half of the families with an ISP and more than two-thirds of the families with a service coordinator. Previous research has revealed multiple barriers when service coordination is to be implemented in healthcare (Hannigan et al., Citation2018; Holum, Citation2012; Nilsen & Jensen, Citation2012). In a Norwegian context, one previously identified challenge is the ISP ultimately becoming a “desk document” instead of a “live document” (Nilsen & Jensen, Citation2012). The existence of an inactive plan may explain why some parents did not report having an ISP in the six months preceding an assessment. Challenges are also reported regarding the implementation of a service coordinator (Nilsen & Jensen, Citation2012). In some cases, the coordinator does not have sufficiently in-depth knowledge of the child and family situation or is not actively involved in the regular follow-up, leading to more irregular and infrequent encounters with the families (Nilsen & Jensen, Citation2012). The interruptions in coordination services recognised in the present study complement previous research and support a call for quality improvements in such services (G. King & Chiarello, Citation2014).

The study was exploratory in nature and aimed to increase the understanding of the complex services offered to young children with CP and their families in a longitudinal perspective. However, the study has certain limitations. First, by using registry data based on a mapping of services, information that went beyond descriptions of services received was not available. For instance, the questionnaires included were not designed to reveal the reasons for not receiving a service, which restricted possibilities for linking perceived needs to the services received. Further, whether parents perceived the interruptions in services received as a lack in continuity in care was not possible to explore with the available data. This points to the need for further research to deepen the knowledge about the service provision and how it is experienced by the families.

Another limitation was that relatively small number of participants, variations in the children’s age when included and differences in the regularity and number of assessments limited the potential for more sophisticated analyses of service trajectories. This limitation implies the use of larger samples in forthcoming quantitative studies.

It should also be noted that the percentage of children at each GMFCS level differed somewhat from the total population of children with CP in Norway, with fewer participants being classified at GMFCS I (44% compared with 53%) (CPRN/CPOP Annual Report 2019). Because the study indicates that families raising children at GMFCS level I receive fewer services than other families, the average number of services and the percentages of families receiving each of the services may have been slightly higher than would have been expected with a more representative sample in terms of GMFCS levels.

In conclusion, the widespread provision of child- and family-directed services indicates a holistic approach in the service system. Multiple services crossing organisational borders indicate the need for the coordination of services to ensure family-centred and coherent care. While multidisciplinary teams and ISPs were frequently reported, the low proportion of families reporting having a service coordinator raises concerns about the implementation of this service in a rehabilitation context. Furthermore, the frequent interruptions in several services draw attention to longitudinal continuity as a persistent concern in childhood rehabilitation. Thus, both coordination and continuity in service provision appear to be areas in need of quality improvement and further research.

Ethics and Consent

Participation in the CPHAB project was voluntary. Written consent was obtained from the parents of all participating children prior to the study. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics of South-Eastern Norway (registration number 2017/782).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the parents who have participated and spent their valuable time filling out the questionnaires, and the staff at the regional rehabilitation units for recruitment and data collection. We further value the contribution from others involved in the CPOP and CPHAB registers.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Runa Kalleson

Runa Kalleson, PT, M.Sc, ph.d. student.

Reidun Jahnsen

Reidun Jahnsen, PT, ph.d., professor.

Sigrid Østensjø

Sigrid Østensjø, PT, ph.d., professor.

References

- Alriksson-Schmidt, A., Nordmark, E., Czuba, T., & Westbom, L. (2017). Stability of the Gross Motor Function Classification System in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A retrospective cohort registry study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 59(6), 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13385

- Alve, V., Madsen, H., Slettebø, Å., Hellem, E., Bruusgaard, K.A., & Langhammer, B. (2013). Individual plan in rehabilitation processes: a tool for flexible collaboration?, Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 15(2), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2012.676568

- Appleton, P. L., Böll, V., Everett, J. M., Kelley, A. M., Meredith, K. H., & Payne, T. G. (1997). Beyond child development centres: Care coordination for children with disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 23(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2214.1997.839839.x

- Beresford, B. A., Clarke, S., & Maddison, J. R. (2018). Therapy interventions for children with neurodisability: A qualitative scoping study of current practice and perceived research needs. Health Technology Assessment, 22(3), 1–150. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta22030

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (Vol. 1, 6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley.

- Cans, C. (2000). Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: A collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 42(12), 816–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2000.tb00695.x

- Delacy, M. J., Reid, S. M., & Group, A. C. P. R. (2016). Profile of associated impairments at age 5 years in Australia by cerebral palsy subtype and Gross Motor Function Classification System level for birth years 1996 to 2005. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 58(S2), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13012

- Demiri, A. S., & Gundersen, T. (2016). Tjenestetilbudet til familier som har barn med funksjonsnedsettelser. Oslo Metropolitan University – OsloMet: NOVA.

- Dempsey, I., & Keen, D. (2008). A review of processes and outcomes in family-centered services for children with a disability. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 28(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121408316699

- Hannigan, B., Simpson, A., Coffey, M., Barlow, S., & Jones, A. (2018). Care coordination as imagined, care coordination as done: Findings from a cross-national mental Health systems study. International Journal of Integrated Care, 18(3), https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.3978

- Hedberg, B., Nordström, E., Kjellström, S., & Josephson, I. (2018). “We found a solution, sort of” – A qualitative interview study with children and parents on their experiences of the coordinated individual plan (CIP) in Sweden. Cogent Medicine, 5(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2018.1428033

- Holum, L. C. (2012). “It is a good idea, but … ” A qualitative study of implementation of ‘individual plan’ in Norwegian mental health care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 12(1), e15. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.809

- Kalleson, R., Jahnsen, R., & Østensjø, S. (2019). Empowerment in families raising a child with cerebral palsy during early childhood: Associations with child, family, and service characteristics. Child: Care, Health and Development, 46(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12716

- King, G., & Chiarello, L. (2014). Family-centered care for children with cerebral palsy: Conceptual and practical considerations to advance care and practice. Journal of Child Neurology, 29(8), 1046–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073814533009

- King, S., Teplicky, R., King, G., & Rosenbaum, P. (2004). Family-centered service for children with cerebral palsy and their families: A review of the literature. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 11(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2004.01.009

- Klevberg, G. L., Ostensjo, S., Elkjaer, S., Kjeken, I., & Jahnsen, R. B. (2017). Hand function in young children with cerebral palsy: Current practice and parent-reported benefits. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 37(2), 222–237. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2016.1158221

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. (2011). Act relating to municipal health and care services, etc. (Health and Care Services Act). Retrieved from: https://app.uio.no/ub/ujur/oversatte-lover/data/lov-20110624-030-eng.pdf

- Myrhaug, H. T., Jahnsen, R., & Østensjø, S. (2016). Family-centred practices in the provision of interventions and services in primary health care: A survey of parents of preschool children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493514551312

- Myrhaug, H. T., & Østensjø, S. (2014). Motor training and physical activity among preschoolers with cerebral palsy: A survey of parents’ experiences. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 34(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2013.810185

- Nilsen, A. C. E., & Jensen, H. C. (2012). Cooperation and coordination around children with individual plans. Cooperation and Coordination Around Children with Individual Plans, 14(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2010.507376

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. (2015). Rehabilitering, habilitering, individuell plan og koordinator. Nasjonal veileder [Rehabilitation, habilitation, individual plan and coordinator. National guidelines]. Retrieved from https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/rehabilitering-habilitering-individuell-plan-og-koordinator

- Palisano, R., Hanna, S., Rosenbaum, P., & Russell, D. (2000). Validation of a model of gross motor function for children with cerebral palsy. Physical Therapy, 80(10), 974–985. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/80.10.974

- Palisano, R., Rosenbaum, P., Walter, S., Russell, D., Wood, E., & Galuppi, B. (1997). Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 39(4), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x

- Proba Research. (2014). Evaluering av tilskudd til tilpasning [Evaluation of grants for adaptions]. Proba Research report 2014 [Accessed 22 Feb 2020]. Retrived from https://proba.no/wp-content/uploads/evaluering-av-tilskudd-til-tilpasning.pdf

- Reid, R. J., Haggerty, J., McKendry, R., & University of British Columbia. (2002). Defusing the confusion: Concepts and measures of continuity of health care. Vancouver, B.C: Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia.

- Ringard, Å., Sagan, A., Sperre Saunes, I., Lindahl, A. K., & Ringard, Å. (2013). Norway: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 15(8), 1–162.

- Rosenbaum, P., Paneth, N., Leviton, A., Goldstein, M., & Bax, M. (2007). The definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 1–44.

- Taylor, E., Schachar, R., Thorley, G., & Wieselberg, M. (1986). Conduct disorder and hyperactivity: I. Separation of hyperactivity and antisocial conduct in British child psychiatric patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 149(6), 760–767. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.149.6.760

- Trute, B. (2007). Service coordination in family-centered childhood disability services: Quality assessment from the family perspective. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 88(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3626

- Wood, E., & Rosenbaum, P. (2000). The Gross Motor Function Classification System for cerebral palsy: A study of reliability and stability over time. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 42(5), 292–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2000.tb00093.x

- World Health Organization. (2018). Continuity and coordination of care: A practice brief to support implementation of the WHO framework on integrated people-centred health services. World Health Organization.