ABSTRACT

The paper presents results of a phenomenological longitudinal qualitative study undertaken with mentors associated with the Big Brothers Big Sisters programme in the Czech Republic. Ten mentors were interviewed during the first month and after 5 and 10 months of their mentoring involvement employing phenomenological in-depth semi-structured interviews. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was subsequently applied using QSR NVivo software for data analysis. This paper reports the findings of an IPA analysis of one of the central theme of mentors‘ experience, common to all interviewed mentors: initial motivation to volunteer in formal youth mentoring relationships (FYMRs). The findings of the IPA analysis are discussed using the framework of self-determination theory (SDT) with its continuum of autonomous and controlling motivations. As a result, we argue that the initial motivations of mentors can be assessed according to the level of autonomy in mentors' motivation, in other words, congruence of their motivations with the authentic self. We argue that the level of congruence of mentors‘ motivation with the authentic self can be considered as the quality feature of the mentors’ motivation. We conclude that, in theory, this feature has an impact on the subsequent dynamics and perceived satisfaction of formal youth mentoring relationships. We recommend that the mentors‘ motivation, and specifically, the level of autonomy in mentors‘ motivation to volunteer with socially disadvantaged children be assessed in mentoring programmes as a qualitative feature in mentorś training and recruitment.

Introduction

Formal youth mentoring interventions (FYMIs) aim to foster the benefits of natural mentoring relationships for children and young people who lack the presence of significant adults in their lives. Formal youth mentoring relationships (FYMRs) aim to achieve the qualities of natural mentoring relationships and provide the benefits of natural mentoring relationships to vulnerable socially-disadvantaged children and youth with the formal assistance of a third party - youth mentoring programme. Due to the relationships’ formal nature, however, not all FYMRs are beneficial, and some are even harmful (e.g. Grossman & Rhodes, Citation2002; Morrow & Styles, Citation1995; Spencer, Citation2007).

It has been argued that the features and dynamics of FYMRs that mediate the benefits of mentoring to children have not been explored sufficiently to date (DeWit et al., Citation2016; Zand et al., Citation2009). Previous studies explored mentors’ initial motivation and its subsequent impact on satisfaction in the mentoring role (Larsson et al., Citation2016) with the application of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000). In addition, motivation in formal mentoring relationships was the subject of several earlier studies in the youth mentoring field. Perceived low motivation, insufficient feedback and a lack of effort or appreciation on the mentee's part were often mentioned by mentors as sources of dissatisfaction in the mentoring role and the reason for early termination (Grossman & Rhodes, Citation2002; Spencer, Citation2007). Furthermore, a perceived discrepancy between the mentor's expected and experienced role was a predictor of their intention to remain in the relationship. The more significant the negative discrepancy between the mentor's ideal and current role found, the lower the intention of mentors to engage in long-term mentoring relationships (Madia & Lutz, Citation2004). Previous research using SDT found that the quality of the initial motivations of helpers (whether autonomous or controlling) impacted the perceived benefits of the helping relationships reported by recipients (Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). Thus, it is relevant for youth mentoring to identify the quality of initial motivations of mentors in the light of SDT. We argue that an analysis of this nature will enhance our understanding of how the initial motivations of mentors influence the characteristics and dynamics of FYMRs. It will also be beneficial for formal youth mentoring programmes to better understand the differing motivations of mentors and how these dispositions can impact mentoring practice.

In this paper, we draw on the findings of a small scale qualitative study using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Smith et al., Citation2012) to answer the research question: Why did mentors initiate volunteering in the youth mentoring programme? The study was conducted in the Big Brothers Big Sisters/Pět P programme in the Czech Republic (BBBS/5P CZ).Footnote1 The findings are discussed and explained in the light of the SDT motivational continuum. Firstly, however, literature in relation to the initial motivation of mentors and its quality, according to SDT, is reviewed (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000).

Motivation in the light of Self-Determination theory

Motivation is defined as a set of interrelated beliefs and emotions that influence and direct behaviour (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985). According to SDT, action is directed towards meeting the Basic Human Needs (BHN) of autonomy, relatedness and competence (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010).

Basic human needs as motivation for behaviour

Autonomy refers to behaviour that one feels authentically emanating from the self. The term “authentic” literally means “really proceeding from its reputed source or author” (Ryan, Citation1991, p. 212; cf Wild, Citation1965, p. 61). The need for autonomy is a need to experience these qualities in one's actions and interactions’ (Ryan, Citation1993, pp. 9–10). In other words, autonomous actions are integral to the person, reflecting the relative unity of the self behind someones’ actions (Ibid). Autonomous behaviour is regulated by one's choice and characterised by flexibility and lack of pressure (Ryan, Citation1993; Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000).

The need for competence can be defined as the need to experience an optimal challenge. People are intrinsically motivated to use their creativity and resourcefulness to master their unique skills and potential. In other words, SDT argues that people typically seek activities that offer the development of their perceived competence (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, p. 130).

Finally, the need for relatedness concerns the need to experience emotional and personal bonds with other people. It reflects the need for the human experience of belonging facilitated in socialising, grouping, and mutual sharing with others (Ryan, Citation1991).

Controlling motivations and amotivation

The SDT distinguishes heteronomous or controlled behaviour that is experienced as not genuinely emanating from the self but is driven by introjected contingencies, ego-involvement or external incentives that originate from outside self - Extrinsic Perceived Locus of Causality (EPLOC; Ryan, Citation1993).

Behaviour initiated with external regulations is performed as an instrumental behaviour directed towards achieving the contingency extrinsic to the activity itself. A contingency is a goal to be reached as an outcome of the performance. The person intends to experience BHN through the incentives, objects or goals s/he aims to achieve through the activity. The satisfaction of basic human needs is diminished during the contingency's performance. The response to the instrumental behaviour is experienced as the self being controlled from EPLOC. As a result, the individual feels external control, pressure and tension in action itself (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, p. 31; Deci; Ryan, Citation1991, Citation1993).

Introjections are internally driven regulations that are not experienced as a part of the autonomous self but are instead controlled from EPLOC. They are contingencies that drive the activity as well as the person who performs it (Ibid). Thus, introjections represent a partial internalisation, where regulations are not a part of the integrated cluster of motivations, cognitions, and emotions that frame the authentic self. Besides, introjections regulate those behaviours that are motivated out of 1) internal ego-rewards such as feelings of pride or contingent self-esteem; 2) avoidance of punishments such as feelings of guilt or anxiety. Thus, introjection is a regulation of behaviour with ego-involvement (Ibid), regulating behaviour with instruments to defend the ego from uncomfortable feelings, actions, and events. For instance, people motivated with introjections aim to demonstrate their competence to avoid conflictual feelings of guilt, failure, or shame (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, p. 72).

Amotivation is a form of behaviour characterised by a lack of intention to act, lack of a sense of competence, and by inactivity in performance due to perceived lack of control over one's behaviour (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, p. 72). Amotivated people do not act at all or act without intention; they only go through motions automatically.

Autonomous motivations

SDT argues that if basic human needs are experienced with a high degree of autonomy and congruence with the self, it pertains to whether the activity originates from the self - from the internal emergent centre of activity (Intrinsic Perceived Locus of Causality or IPLOC; Ryan, Citation1993). Behaviour originating from IPLOC is regulated with autonomous motivations and expresses the endorsement of and relative unity between the self and the exhibited behaviours (Ryan, Citation1993; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, Citation1985; Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). The highest self-determination in an activity initiated from IPLOC is evident in intrinsically motivated behaviour when an individual initiates an action out of the interest, enjoyment, or excitement they expect to feel in its performance (Intrinsic motivation). An action may also be initiated with high self-determination from external sources (extrinsic autonomous motivations) that the individual identifies with or that are congruent with one's values and attitudes (Identification, Integration). As a result, the individual experiences basic human needs in action. The action itself is perceived as inherently satisfying for the activity's performance as one performs out of own choice and with a high degree of congruence with the authentic self (Ryan, Citation1991; Ryan & Deci, Citation1985). Thus, autonomous motivation in SDT is defined as a need to experience self-determined competence in action (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985).

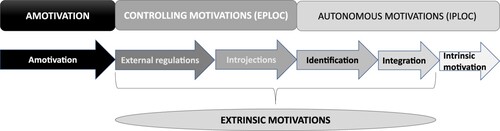

In summary, as displayed in , SDT identifies a continuum of behavioural regulations (or motivation types) that vary according to the degree of autonomy (self-determination) in the behaviour. Behaviour itself varies in the degree to which it is autonomous, controlled, or amotivated (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985). The more autonomous the actions are, the more congruent they are with the authentic self of the person and the more they express the endorsement, authenticity and unity between the self and exhibited behaviours (Ryan, Citation1993; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, Citation1985; Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). As such, SDT distinguishes the quality of motivation in human performance according to the level of autonomy - the congruence of the motivation of the performed behaviour with the authentic self. Besides, SDT argues that the quality of the initial motivation in helping behaviour affects the perceived benefits of the help reported by recipients (Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). It is, therefore, essential to assess the initial motivations of volunteers who come forward to mentor socially-disadvantaged children and youth.

Figure 1. Motivation continuum in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985).

Context of the study: Czech Big Brothers Big Sisters programme

The analysis presented in this paper forms part of a more extensive longitudinal phenomenological study of the characteristics, dynamics and perceived benefits of 10 formal youth mentoring relationships tracked over 12 months (Brumovská, Citation2017).Footnote2 The study's fieldwork and data collection took place in the BBBS/5P programme in the Czech Republic between 2011 and 2012.Footnote3 Affiliates of BBBS/5P CZ recruited, trained, matched, and supervised voluntary mentors in line with BBBS International's standards of practice. Two BBBS/5P CZ affiliates took part in the research study.

Methodology

The study adopted a social-constructivist qualitative interpretive framework (Creswell, Citation2013), which allowed for exploration of the subjectivity of experiences and meanings in their historical, cultural and social contexts (Creswell, Citation2013, p. 23). Within the social constructivist paradigm, longitudinal qualitative case-studies with a phenomenological approach to in-depth interviews (Kvale, Citation1996), and Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Smith et al., Citation2012) were employed in the research design. The phenomenological approach to data collection and analysis was chosen because it foregrounds the examination of how people make sense of their significant life experiences (Smith et al., Citation2012). IPA interprets experiences as both individuals’ accounts that are socially constructed relative to the individuality of human beings and experiences that are generalisable as lived phenomena. In IPA, generalisation derives from the in-depth idiographic analysis of particular cases. Thus, IPA was viewed as a suitable method for in-depth exploration of mentor's experiences concerning mentoring phenomena.

Sample

The sample consisted of ten volunteer mentors who were sought from a group of volunteers who were recruited, trained, and matched in autumn 2010 in two participating BBBS CZ affiliates. Written consent to take part in the research study was obtained from afilliate organisation and from all participants in the study. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the authors’ institution. Participating mentors were aged between 18 and 28 years, with eight females and two males. They were either high school students (1), college students (4), or employed (5).

Mentees in the ten tracked mentoring matches were referred from social workers and special-education professionals in schools, child psychologists or psychiatrists, and teachers. Mentees were aged between 6 and 14-years and had various difficulties such as minor disabilities, ADHD or socio-economic disadvantage. All experienced difficulties in relationships with their peers or parents.

In-depth semi-structured interviews with mentors on their initial motivations to volunteer in BBBS/5P CZ were conducted during the first month using a phenomenological approach to interviewing (Kvale, Citation1996). Interviews lasted between 20 and 50 min. Regarding the theme of initial motivation, all ten mentors spoke about their expectations for the mentoring role, what they would like to gain from their involvement in the mentoring programme and why they applied for the volunteering role. Their hopes and expectations were then analysed as initial motivations.

Data analysis was conducted using the IPA method (Brumovská, Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2012). The transcripts of the ten interviews were downloaded to QSR NVivo 10 software. In keeping with the idiographic approach, each interview was divided into parts and categories (emergent themes) (Bazeley, Citation2009; Smith et al., Citation2012). In the first hermeneutic round of analysis, an in-depth idiographic thematic analysis on each of the mentors’ experiences was conducted (Smith et al., Citation2012). The themes derived from each of the mentors’ experience were further compared and contrasted between cases. As a result, ten themes emerged from IPA analysis that were common to all ten mentors’ experience. Finally, Self-Determination theory was applied to generalise, interpret and discuss the results of the IPA analysis. The theme of ‘The Initial Motivation of Mentors for Volunteering in the Youth Mentoring Programme’ was the first theme of the common mentoring experience derived from the IPA analysis’. Names and minor details were changed to protect the anonymity of participants. The results are presented and discussed using the SDT concepts of Controlling and Autonomous motivations (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

Findings 1 discussed with SDT: amotivation and controlling motivations of mentors

Six volunteers expected to gain extrinsic rewards from their mentoring involvement sourced out of EPLOC to satisfy their BHN by becoming mentors (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000). Mentors with controlling motivations particularly expected to feel emotionally supported by the other volunteers; to attest their competenceFootnote4 (Weiss, Citation1973) in the mentoring role; and to feel needed, helpful, and useful for the child. They also expressed amotivation for mentoring involvement.

One mentor had severe doubts about getting involved in the mentoring relationship and was amotivated for becoming involved as she recalled her initial hesitation and doubts about the purpose and future enjoyment of her future mentoring role. In the beginning of her involvement, she contrasted her mentoring involvement with her private relationships and was deciding which of these relationships would provide her with a better opportunity to experience her need for relatedness (Ibid):

‘Initially, when I came to the BBBS training, I saw the other girls how excited they were about it […]. I wasn't excited about it at all […]. I was almost about to leave, to say: ‘Look, I am sorry but I don't want to be here, I am going back home, I don't want it anymore.’

(Luisa, Affiliate 1, Interview 1)

‘[…] I was thinking about starting my own family and having a baby at that time, my own child, so I wouldn't have that much time to give it. I asked myself what was I doing there actually? […] well, and then I stayed and started to look forward to it […] and another phase I doubted then was when they found and offered me a match with Denisa. I was deciding if I actually really wanted it, if I am able to commit to it for that 1 year at least …

Int: And you decided that you were (able to commit to it)?

L: I realised that it didn't look like I’ ‘m going to have a baby yet.’

(Luisa, Affiliate 1, Interview 2)

Besides, mentors were motivated to initiate involvement in the mentoring relationship by expecting the extrinsic benefit of their volunteering. Matylda intended to use the formal certificate provided by the BBBS/5PCZ programme at the end of the mentoring contract to help her pursue her future profession. Hence, we argue that the achievement of the certificate was an external regulation with which the mentor initiated the mentoring commitment (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000):

‘[…]I'd kind of need the paper from BBBS that certifies that I went through the training and can work (elsewhere).’

(Matylda, Affiliate 2, Interview 1)

Luisa was motivated by the expectation of experiencing emotional support from other volunteers. She expected that her involvement in the BBBS supervision meetings would fulfil her emotional integration needs (Weiss, Citation1973).Footnote5 Thus, she expected to benefit from involvement in the BBBS programme rather than from involvement in the mentoring relationship. It can be argued that she was motivated by EPLOC with external regulation, being regulated by the need for relatedness she expected to experience in the group of volunteers:

‘As I am employed in IT, we do’ not communicate with our peers; this is something special for me. It is like giving candy to a kid. You suddenly have a space to talk about what you're worried about … which is something I don't usually have available that much in my life.’

(Luisa, Affiliate 1, Interview 1)

Moreover, mentors were motivated from EPLOC with introjections; the data shows evidence of ego-involvement in mentors’ initial motivations (Ryan, Citation1991, Citation1993; Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000). Firstly, mentors were motivated to initiate volunteering to attest their competence in the different roles they expected to encounter in the mentoring relationship. For instance, Marta was regulated by the expectation of attesting her competence for a future professional role. She chose to volunteer for BBBS/5P CZ as she presumed the programme would provide her with an opportunity to experience the need for competence (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1973):

‘My first motivation was simply to gain experience in this NGO because I was thinking about my future studies at college in psychology where they require previous experience so it was my first motivation - that's how I got the idea to become involved in something like that.’

(Marta, Affiliate 1, Interview 1)

‘[…] you don't really know what you can give the child (without experience) …

Int: What do you mean in particular?

M: (You see) if you have any skills or any particular views on life that you can show and explain to the child … so I wanted mainly to find out if I am suited to working with people … ’

(Marta, Affiliate 1, Interview 2)

Another volunteer, Květa, became a mentor with the expectation that she would be seen as a female role model for a child, hence mediating her female attitudes and experiences to the mentee. In other words, Květa became involved as a mentor to satisfy the need for competence and reassurance of her worth (Weiss, Citation1973) in the specific female roles she constructed in the relationship. It can be argued that Květa was motivated by introjected regulation of ego-involvement to fulfil her need for reassurance of worth (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1973) through the experience of a mentoring relationship. Thus, her need for reassurance of worth functioned as the extrinsic regulation that controlled her mentoring involvement from EPLOC (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1973):

‘The idea that you can inspire someone with your example […] so I thought that I'm not that entirely bad and that it could work out … .Moreover, I became interested in her because I felt that there would be a need for, well, I am always saying a female role model even though I am no superwoman at all (Laugh) […] but as she misses her mum I thought it is kind of sound that the girl would be meeting with a female and that I could show her how things work from a female perspective.’

(Květa, Affiliate 1, Interview 1).

Similarly, Luisa intended to be reassured about her worth as the respected role model she intended to become in the mentoring relationship. In particular, she expected to be appreciated by the child for her involvement, which would reinforce her self-esteem. The controlling ego-involvement that regulated Luisa's engagement in the mentoring relationship from EPLOC was expressed in terms of an expectation that the child would achieve more positive development and well-being as a result of her actions in the mentoring role:

‘I expect to feel good that she will be able to see something new thanks to me, she will learn new things, she will enjoy the time - thanks to me … otherwise, she would only be sitting at home on her computer and stuff.’

(Luisa, Affiliate 1, Interview 1)

Besides, mentors’ involvement was also motivated by intentions to feel needed, useful, and responsible for a child. There was an expectation that, in turn, they would feel good about themselves. We argue that these mentors were regulated by an introjected controlling motivation with ego-involvement driven towards the need for relatedness, specified as a need for an opportunity for nurturance (La Guardia, Citation2009; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1973).

For example, Matylda expected to help someone in need who would, in turn, appreciate her support. She felt sympathy for the child in need she would volunteer with and expressed the hope that “saving at least one child in need” in the mentoring role would increase her sense of self-worth. Similarly, Viki expected that the feeling of being needed by the child in the mentoring relationship would make her feel good about herself:

‘Int: How would you describe what the volunteer does? What would you expect?

M: They are helping the people who are in need and who appreciate it. They just have a feeling that they want to help someone. And I felt kind of sorry for those kids in some ways. I know I won't save the world, but I hope I can help at least one child […] if it was one child only, it would still be better than no one.’

(Matylda, Affiliate 2, Interview 1)

‘V: I thought I would spend my time meaningfully and that I would help someone … and that it will help me at the same time …

Int: And can you say in what ways for instance?

V: That feeling of someone's need; that someone knows that I am here for him, that I am doing something meaningful.’

(Viki, Affiliate 2, Interview 1)

Luisa mentioned that a lack of opportunity for nurturance with her partner caused her feelings of emptiness (Weiss, Citation1973) and led to her involvement in the BBBS programme. Thus she was motivated by a need for relatedness in terms of a nurturing connection (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1973) whereby she expected to feel useful by taking responsibility for a mentee’ s care and well-being:

‘I thought I would spend more time with my boyfriend … however it turned out that he was not interested in it that much so I was looking for something else that would be meaningful […] someone who would be interested (in my time) […] so I thought it would be interesting to try to be useful for someone, helpful … to feel kind of useful by doing something.’

(Luisa, Affiliate 1, Interview 3)

Finally, some mentors initiated a mentoring relationship out of their relational needs for the friendship and emotional support they expected to experience in the mentoring role. Barbel initiated her mentoring relationship to share social events, interests, and experiences with the child. She expected to be better integrated into her new community. However, even though the BBBS/5P CZ programme's goal is to create a match in which interests and experiences can be shared, the primary goal is that social integration is facilitated for children. Hence, it could be argued that Barbel's initial motivation to volunteer was driven from EPLOC as the mentoring relationship was supposed to become an instrument for the satisfaction of her need (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1973):

‘I found this by the way and decided I wanted to try it because I like these opportunities … in particular, I can have a friend here because I'm new in this place, not even here for 3 months.’

(Barbel, Affiliate 2, Interview 1)

Findings 2 discussed with SDT: initial autonomous motivations

Mentors with initial autonomous motivations got involved in the programme due to their interests in volunteering. Their involvement was based on their pro-social values and attitudes that were reflected inthe BBBS/5P CZ programme's mission, and in the character of the mentoring role as they understood it. They expected that their values and beliefs could be realised through involvement in a mentoring role. Thus, they became involved as they identified themselves (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000) with the mentoring programme's values and the values of the mentoring role as they perceived them.

Secondly, mentors were intrinsically motivated (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985) to build a nurturing relationship with a child. Their mentoring involvement was driven intrinsically by the interest, enjoyment, and excitement (Ibid) they felt about the prospect of a relationship with a child. Thus, there was an expectation that the mentoring relationship would be experienced as inherently satisfying (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000). Their statements about their motivation for mentoring involvement had a more general character in comparison to the particular expectations and focus on “me” of mentors with controlling motivations. In addition, their motivations were stated clearly and expressed without hesitation.

In particular, Tina mentioned that the mission of the programme attracted her as it reflected her pro-social values:

‘[…] I got interested due to its mission, the values it promotes … ’

(Tina, Affiliate 1, Interview 2)

Similarly, as a volunteer, Ivan believed he could contribute to the community and “give back” to society in return for the social benefits he had received in the past. In general, he felt that the experience of volunteering in BBBS CZ would be in congruence with his pro-social attitudes. Hence, the role of mentor in BBBS was expected to be autonomously satisfying as Ivan expected it would facilitate the experience of the lived universal values and attitudes he identified with:

‘I am a volunteer … I am not sure if since 2004 or 2006 […] but my motivation is still the same … I feel that … as I've received many social benefits from society, I think it is necessary to give back … ’

(Ivan, Affiliate 1, Interview 2).

Moreover, similar to mentors with controlling motivations, Sára and Nina expected to experience an opportunity for nurturance in the mentoring role (Weiss, Citation1973). However, contrary to mentors with controlling motives, Sara and Nina expected that the mentoring experience would be inherently satisfying due to the character of the relationship with the child. They had experienced informal mentoring relationships with children before and hoped to repeat the experience as they perceived it to be inherently satisfying.

In particular, Sára became interested in the programme when she saw her friend volunteering with a mentee. She liked the general idea of a mentoring relationship and the BBBS CZ programme because she felt participation in it would be congruent with her pro-social values and attitudes. Thus, Sára identified with the mission of the mentoring role. She had experienced a similar mentoring relationship as a childcare worker before and expected to experience the same satisfaction in the mentoring role. Hence, it can be argued that her involvement was autonomously regulated by identification with the pro-social values of the mentoring role (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985); and out of the intrinsic enjoyment of the relationship with the child she presumed the mentoring role would offer her (Ibid):

‘Int: How did you get to know about the programme?

S: From a volunteer in here (BBBS) … I got information on it from her, and … I liked the idea of it in general … One wants to do something to feel that apart from work and duties there is still something else I do for someone else, not for myself only; and at the same time, I do it for myself because it is satisfying … It is a meaningful activity, and I like children in general … and especially the relationship with them … do silly things with them, and it is a different dimension of love, I mean the dimension of some kind of emotion the adult keeps towards the child … .I worked as an au-pair before so I experienced something similar … .so I applied for it.’

(Sára, Affiliate 1, Interview 1)

Nina similarly presumed to be satisfied due to the nature of the mentoring relationship. She chose the BBBS/5P CZ programme because of its focus on children and for the nature of the mentor's role. Like Sára, Nina expected that the experience would be inherently satisfying for her due to the enjoyment and fun with the child she would share in the relationship. She based her expectation on previous positive experiences with children:

‘I always wanted to volunteer […] I wanted to do something I could have a satisfying feeling with and even have fun and get to know many new things … and I think it changes you, for sure it does. Just the relationship, as it is unique, different from those I have with my peers […] I like children. I always did childmind at our family parties and stuff, but I don't know any boy of this age, I don't know how they act, the games they like and stuff so it is a change for me and a very beneficial thing that I can experience.’

(Nina, Affiliate 1, Interview 2).

Summary and conclusion

According to the continuum of motivation offered in SDT and applied to the data of mentors’ initial motivations, this paper has shown that mentors’ initial motivations ranged on a scale from amotivation through controlling motivations with extrinsic regulations to the autonomous motivations with intrinsic motives to volunteer with children. As summarises, the motives of mentors were expressed in terms of expectations about the mentoring role they were starting and its benefits for them personally.

Table 1. Summary of mentors’ motivation on SDT continuum.

Firstly, the data analysis clearly showed that six out of ten mentors were initially amotivated, or regulated for mentoring involvement from EPLOC with controlling external or introjected regulations (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985). We argued that mentors with initial controlling motivations were regulated by an expectation to experience satisfaction of their needs through the mentoring role. In particular, mentors with controlling motivations wanted to attest to their competence and satisfy their need for reassurance of worth (Weiss, Citation1973). They also intended to experience relatedness as an opportunity for nurturance (Ibid) whereby they aimed to experience feelings of being needed by children (Weiss, Citation1973). The need for social and emotional integration (Ibid) also controlled mentors’ involvement. Thus, these mentors were involved in the mentoring relationship with controlling introjected motivations regulated out of EPLOC with ego-involvement (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985). Finally, the data showed that amotivation also appeared in “mentors” motivations and complemented the initial controlling motivations (La Guardia, Citation2009; Ryan, Citation1991, Citation1993; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, Citation1985).

Secondly, all four autonomously motivated mentors mentioned that they volunteered because they identified their values and attitudes with the BBBS CZ programme's mission and saw the opportunity to experience these values in the mentoring role. At the same time, they emphasised that they became involved because they expected to experience enjoyment, interest, or excitement in the relationship with the child. In other words, they recognised the intrinsically satisfying character of the mentoring relationship. They presumed that the mentoring role would provide them with the opportunity to experience the satisfaction of BHN (Ryan & Deci, Citation1985, Citation2000). We argued that these mentors saw the mentoring role as congruent with their values, attitudes, and authentic self. Their mentoring involvement was thus driven autonomously with self-determination from IPLOC (Ibid).

Mentors’ motives ranged in quality according to the degree of autonomy and congruence with their authentic self in the mentoring role (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). In other words, mentors’ motives predicted the extent to which mentors would be authentic and act with high integrity in congruence with their authentic self while developing a mentoring relationship with mentees.

SDT (Ryan, Citation1991, Citation1993; Ryan & Solky, Citation1996) argues that children's positive development is facilitated in social interactions with significant adults. Thus, SDT draws attention to the quality of interactions and their impact on children's positive development. Previous research using SDT showed that carers’ initial motivation was a moderator of quality in helping behaviour and helping relationships (Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). We argue that the quality of initial motivation according to its Controlling and Autonomous dimensions is likely to predict mentors’ abilities to cope with mentoring challenges and develop a trusting, secure, supportive relationship with the child (Brumovská, Citation2017). In particular, the level of congruence between the mentoring role and the authentic self is likely to predict the degree to which mentors’ basic human needs of relatedness, autonomy and competence are fulfilled in the mentoring role. The more autonomously the mentor is motivated for action in the mentoring role, the more they are likely to fulfill basic human needs while engaging with their mentees directly in the relationship (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Brumovská, Citation2017). Thus, we argue that the level of autonomy in mentors’ initial motivation predicts the approach they subsequenty develop and eventually their level of satisfaction in the mentoring role (Brumovská, Citation2017). In simple terms, it predicts the comfort of the mentor and the mentee in the relationship. For instance, due to the experience of BHN in the mentoring role, mentors with autonomous motivations may feel higher self-efficacy and competence while developing a close, trusting and supportive relationship with the child. Furthermore, because the autonomously motivated mentors will be inherently satisfied with the mentoring activity, their feelings of satisfaction are likely to enhance the prospects of their developing a close bond with the child.

On the contrary, mentors with controlling motives may seek extrinsic incentives. Instead of feeling satisfaction in the mentoring activity itself, they might search for external sources of satisfaction in the mentoring role. In turn, this may also impact on the quality and benefits of their relationship with the child (Brumovská, Citation2017).

In conclusion, we argue that the assessment of motivation and its quality according to the level of autonomy or control in the mentoring role is essential as it is likely to predict the future level of satisfaction for mentors in the mentoring role and implicitly the quality of the mentoring relationship the mentor develops with the child (Brumovská, Citation2017). As a result, assessing the motivations of mentors can be an important task for formal youth mentoring programmes when recruiting and training new volunteers for mentoring roles. Further research on mentors’ motivation and its subsequent impact on relationships’ dynamics and quality is needed to support our findings and discussion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tereza J. Brumovská

Dr Tereza J. Brumovská is a Lecturer in the School of Liberal Arts and Humanities and an MSCA IF Research fellow at Charles University in Prague in the ENCOUNTER project exploring experiences of natural mentoring phenomena in children and young people in the Czech context. Tereza publishes on different themes regarding children and young people, including youth mentoring, participation, inclusion, education, child-and-youth-centred approaches and arts-based qualitative research methods.

Bernadine Brady

Dr Bernadine Brady is a Lecturer in the School of Political Science & Sociology and Associate Director of the UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre at NUI Galway. Bernadine has published widely on themes related to young people, including youth work, mentoring, participation, empathy and civic engagement.

Notes

1 Pět P (5P) is the name of the Czech version of the Big Brothers Big Sisters International programme implemented and operating under BBBS International standards of practice in the Czech Republic since 1997.

2 The BBBS/5P CZ programme aims to foster one-to-one relationships between a supportive adult volunteer and a vulnerable child or youth who experience any form of disadvantage in their life. The aim of the relationship is to meet up once a week for 2–3 h, spend time with enjoyable activities in the match over at least 10 months of mentoring involvement. The experience of the relationship is supposed to be supportive and beneficial for the mentee.

3 The first author of this article is a native Czech speaker. The data were collected in the Czech language and translated into English by the first author of the study for the purpose of analysis and reporting of research results.

4 Weiss (Citation1973) developed a theory on the functions of social relationships where “attest of one’s competence” is one of the functions of the dyadic relationships he identified. In particular, mentors in relationships with mentees intended to test their abilities and relational skills in relationships with children, and be recognised and assured about these – by the programme or by expectations on feedback from mentees.

5 “Emotional integration is provided in relationships that offer the stabilization of emotions through acceptance and supportive interactions” (Weiss, Citation1973).

References

- Bazeley, P. (2009). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. SAGE Publishing.

- Brumovská, T. (2017). Initial Motivation and its Impact on Quality and Dynamics in Formal Youth Mentoring Relationships: A Longitudinal IPA Study. Doctoral dissertation. School of Political Science and Sociology. National University of Ireland, Galway. https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/handle/10379/7119

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE Publishing.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the Self-Determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- DeWit, D. J., David DuBois, D., Erdem, G., Larose, S., Lipman, E. L., & Spencer, R. (2016). Mentoring relationship closures in Big Brothers Big Sisters community mentoring programs: Patterns and associated risk factors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(1-2), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12023

- Grossman, J. B., & Rhodes, J. E. (2002). The test of time: Predictors and effects of duration in youth mentoring relationships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014680827552

- Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews. SAGE Publishing.

- La Guardia, J. G. (2009). Developing who I am: A Self-Determination theory approach to the establishment of healthy identities. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832350

- Larsson, M., Pettersson, C., Eriksson, C., & Skoog, T. (2016). Initial motives and organisational context enabling female mentors’ engagement in formal mentoring – A qualitative study from the mentors’ perspective. Children and Youth Services Review, 71, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.026

- Madia, B., & Lutz, C. J. (2004). Perceived similarity, expectation-reality discrepancies, and mentors’ expressed intention to remain in Big Brothers Big Sisters programs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(3), 598–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02562.x

- Morrow, K. V., & Styles, M. B. (1995). Building relationships With youth in program settings: A study of Big brothers/Big sisters. Public/Private Ventures.

- Ryan, R. M. (1991). The nature of the self in autonomy and relatedness., in. In J. Strauss, & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), The self: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 208–238). Springer-Verlag.

- Ryan, R. M. (1993). Agency and organisation: Intrinsic motivation, autonomy and the self in psychological development. In J. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 1–56). University Of Nebrasca Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and Self-Determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Solky, J. A. (1996). What Is supportive about social support? In. In G. R. Pierce, B. R. Sarason, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Handbook of social support and the family. The Springer series on stress and coping (pp. 249–267). Springer.

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2012). Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: theory, method and research. SAGE Publishing.

- Spencer, R. (2007). It’s not really what I expected: A qualitative study of youth mentoring relationship failures. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(4), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407301915

- Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for pro-social behaviour and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016984

- Weiss, R. S. (1973). Materials for a theory of social relationships. In W. G. Bennis (Ed.), Interpersonal dynamics: Essays and readings on human interaction (pp. 103–110). Dorsey.

- Wild, J. (1965). Authentic existence: A new approach to „value theory“. In J. M. Edie (Ed.), An invitation to phenomenology: Studies in the philosophy of experience (pp. 59–78). Quadrangle.

- Zand, D. H., Thomson, N., Cervantes, R., Espiritu, R., Klagholzd, D., LaBlance, R., & Taylor, A. (2009). The mentor–youth alliance: The role of mentoring relationships in promoting youth competence. Journal of Adolescence, 32(1), 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.12.006