ABSTRACT

There are a variety of different psychological interventions used to treat recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Active components in these interventions are unclear. Parents play an important role when it comes to their children's response to pain and management of pain, and are regularly involved in interventions. Four electronic databases were searched (CINAHL Complete, Medline, APA PsychArticles and APA PsychInfo) in order to examine in what ways parents are involved across different therapeutic modalities, and interventions delivered in a variety of formats. In this descriptive review of the literature, 30 studies were included with a total of 1848 participants ranging from age 4–18. The review also discusses the outcomes of studies involving parents. Most of the studies in this review involved parents through psycho-education about pain and strategies for managing pain, however, it remains unclear how parental involvement impacts outcomes. Further research is needed to determine the active components in psychological interventions for recurrent abdominal pain. This research should also include how parental involvement impacts these interventions.

Introduction

Recurrent Abdominal Pain (RAP) is a common complaint seen in child health and medical settings, where repeated stomach aches are the central difficulty, and where no organic cause for the pain has been identified (Plunkett & Beattie, Citation2005). While no specific cause has been identified for RAP, research identifies a variety of factors which can be linked to the condition, and thus it is proposed that a bio-psycho-social model is best used to conceptualise RAP (Deacy et al., Citation2019; Nieto et al., Citation2020). Bio-psycho-social factors include, but are not limited to, early life experiences, parental behaviours, co-morbid anxiety, social stressors and gut permeability (Van Oudenhove et al., Citation2016).

RAP can lead to school absences, hospital admissions, emotional problems, functional impairment and significant levels of distress in the child and their family (Weydert et al., Citation2003). RAP is associated with high healthcare costs to both families and healthcare systems (Groenewald & Palermo, Citation2015; Hoekman et al., Citation2015). Given the impact RAP has on individuals, families and the healthcare system, it is important that the condition is treated appropriately and promptly to minimise distress and impact on quality of life.

Before a diagnosis of RAP is given, families tend to undergo several procedures to try identifying a cause or rule out particular illnesses. Typically, only after this has been completed are families referred for psychological assessment (Schurman & Friesen, Citation2010). This can lead to the process being quite protracted for families, resulting in increased worry (Bufler et al., Citation2011).

Increased levels of parental anxiety, preoccupation with health concerns, stress within the family, and parental marital difficulties are highlighted as precipitating factors in relation to RAP (Chambers, Citation2003; Robins et al., Citation2005). It is hypothesised that social learning theory plays a role, as children model how their parents respond to pain. Research indicates that parents of children with RAP are more likely to catastrophise their own experience of pain and unintentionally reinforce pain behaviours (Chambers, Citation2003; Logan & Scharff, Citation2005). Chambers (Citation2003) also lists parental reinforcement of sick behaviours, parental over-involvement and other family environment factors as contributing towards ineffective pain management.

There are a variety of psychosocial interventions for RAP, including behavioural or cognitive behavioural techniques, family-centred approaches, psychotherapy, guided imagery, hypnotherapy, yoga or multi-component therapies (Abbott et al., Citation2017). Interventions have been delivered individually or in group format, and recent research has examined web-based interventions. Some interventions focus solely on the child with others also involving parents. There is little consensus on which treatments to offer children and adolescents with RAP, which can lead to an inconsistent approach to treatment (Abbott et al., Citation2017). As treatment options vary, so too does parental involvement in interventions. There is empirical support suggesting that parental involvement in treatments of chronic pain in childhood supports the maintenance of treatment effects, and the benefits of modelling and reinforcement have been explored (Chambers, Citation2003).

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there is a need for further research into active components in psychosocial interventions for RAP (Abbott et al., Citation2017). Given how parental facets have been highlighted as predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors in relation to RAP, this paper provides a descriptive review of the literature of how parents are involved in psychological interventions for RAP. This review will increase our understanding of how parents are involved in psychological interventions for RAP, and begin to explore how parents may be helpful as part of a therapeutic approach. This review can also support the development of effective interventions and aid effective service delivery.

Method

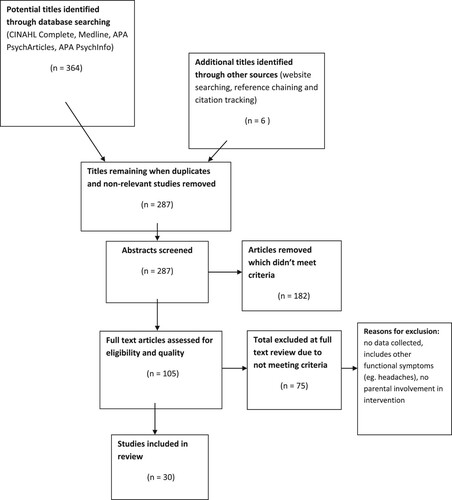

The following four electronic databases were searched: CINAHL Complete, Medline, APA PsychArticles and APA PsychInfo. The databases were searched using the search terms outlined below in . Boolean operators were used to ensure maximum numbers of relevant articles were retrieved. These databases were searched between October 2020 and April 2021, checking monthly for any newly published articles. This gave a total of 364 articles, and further hand-searching took place to ensure all relevant articles were included. Articles were scanned for eligibility and articles which were selected for full text review were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. A quality assessment for each article was undertaken using the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines (Moola et al., Citation2020). A Prisma flow chart of article selection is detailed in .

Table 1. A table outlining search terms and Boolean operators for the review study.

Inclusion criteria for the review were;

(a) Studies with participants below age 18 with diagnosis of RAP or functional abdominal pain disorders

(b) Studies where participants underwent psychological intervention related to pain

(c) Studies where this intervention involved parents.

Exclusion criteria for the review were;

Studies where there was no data collection

Studies where there was an organic cause or medical explanation for the abdominal pain

Studies where there were no psychological interventions related to the abdominal pain

Studies with no parental involvement in the intervention

Studies of general chronic pain not specific to abdominal pain.

Following review of inclusion and exclusion criteria and quality assessment a total of 30 articles were reviewed for data extraction and synthesis. The list of included studies is detailed in the supplemental file available online. In analysing and synthesising the data from the studies, the researcher examined the treatment modality used, number of sessions, how parents were involved in the intervention, outcomes of the intervention, and compared and contrasted these. This involved examining ways parents were involved in treatment and how treatment outcomes were measured.

Analysis

Details of studies included in the review are outlined below in .

Table 2. A table outlining descriptions of studies included in the review.

Studies used a variety of therapeutic modalities, which will be explored in further detail below. As the majority of studies used a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) approach, this category was sub-divided into ways the CBT programme was delivered; individual, group and remote.

Individual CBT

Eight studies involved use of individual CBT, delivered face-to-face with each child, or parent and child. These studies varied in terms of the age range used, sample size, content of the interventions, and how outcomes were measured. Sanders et al. (Citation1989) used an eight session CBT intervention with 16 participants and targeted ages 6-12. Compared to a control group, the treatment group experienced significant decrease in pain reports in both parent and child pain ratings. Using the same sample, Sanders et al. (Citation1990) found that the treatment sped up the rate of recovery.

Zucker et al. (Citation2017) also targeted a younger child age group, and explored a CBT treatment specifically targeting 24 children age 5–9 years old. This 10 week programme featured parental involvement through therapists providing a formulation of their child as sensitive to their internal experience and also the world around them. Sanders et al. (Citation1989), Sanders et al. (Citation1990), and Zucker et al. (Citation2017) had parental involvement as central aspects to the intervention, which is to be expected given that these interventions were specifically aimed at younger children.

In relation to co-morbidities, Masia Warner et al. (Citation2009) evaluated CBT for individuals aged 8–15 with anxiety disorders and medically unexplained abdominal pain. Parents attended the beginning and end of each of their child's 12 sessions to discuss progress and go over session content and homework exercises. While all children showed improvements in relation to pain experiences, the sample size of seven was very small, and the study lacked a control group.

Van der Veek et al. (Citation2013) completed a randomised controlled trial where a six session CBT treatment was compared to intensive medical care in children and adolescents age 7–18. However, in this study, the CBT treatments were individualised with children receiving different modules depending on their individual needs. Twenty four of the 51 participants in the CBT condition received parental involvement as part of their CBT intervention, which included parents receiving education about the role of avoidance and frequently asking about pain as maintenance factors.

Levy et al. (Citation2010) used a relatively large-sample size of 200, and a varied age range of 7–17 where children and adolescents in the social learning and CBT treatment condition received three sessions focusing on relaxation training, modifying family responses to pain behaviours and cognitive restructuring. Compared to a control group, participants in the treatment condition showed greater decreases in pain and symptom severity according to parental reports, and parents showed greater decreases in solicitous responses to their child's symptoms compared to controls.

In a follow-up study, Levy et al. (Citation2013) found that improvements were maintained at follow-up, with the CBT group reporting greater decreases in symptom severity and greater improvements in coping responses. To investigate mediators of treatment outcomes, Levy et al. (Citation2014) completed a multiple mediation analysis on this sample, and found that reductions in parental perceived threat in relation to the pain, and children's catastrophising about the pain mediated reductions in reported symptom severity and pain experience in both parent and child reports.

In summary, the studies of individually delivered CBT are considerably varied, in terms of age ranges and length of interventions, ranging from three sessions to twelve sessions. Parental involvement also differs related to the age of the child or adolescent. The studies also vary in how outcomes are measured, such as comparing to control groups or treatment as usual, or discussing pre-intervention and post-intervention outcomes. Again, these are also varied with studies measuring parental reports of pain, child reports of pain, symptom severity or distress about symptoms. However, all studies show how involving parents in these interventions can be effective, although the mechanisms of how parents impact treatment outcomes are unknown. Levy et al. (Citation2014) does show very preliminary evidence of how these interventions might work through changing parental cognitions, however, there is a need for further research in this area to identify active components of these interventions, and indeed, active components in parental involvement.

Group CBT

Two studies entailed direct involvement with parents as part of CBT group intervention. Both studies used small sample sizes of 29 and with targeted age ranges in middle childhood. Groß and Warschburger (Citation2013) evaluated a six session “Stop the pain with Happy-Pingu” cognitive–behavioural group for children aged 6--11, and which had a further session for parents. Calvano et al. (Citation2017) also used the “Stop the pain with Happy-Pingu” intervention for children aged 6--12, however, the parent session also focused on building trust in the competencies the child had acquired through treatment. Parents were given detailed information about the contents of their children's group sessions, and asked to reflect on their own roles in perpetuating the pain. Children showed a significant decrease in pain symptoms, as perceived by their mothers.

Remotely delivered CBT interventions

Nine studies used a web-based or telephone-based CBT intervention with a variety of sample sizes from 9 to 316 and across a variety of age ranges. Nieto et al. (Citation2015) examined the effects of an online intervention known as DARweb. Parental sessions covered information about functional abdominal pain, triggers, goal setting and thought management. Parents were also given training in different communication styles, particularly assertive communication. The intervention covered material on parental responses to their child's pain and their own pain, discussing the importance of having positive role models and using strategies to promote well behaviours. Nieto et al. (Citation2019a) found that the intervention had significant impact on parent's ratings of pain severity and quality of life scores. When compared to a control group, Nieto et al. (Citation2019b) found significant reduction in pain frequency and significant interactions for parents’ solicitous responses and promoting well behaviours.

A similar intervention was developed by Lalouni et al. (Citation2017), who completed an internet-delivered CBT treatment targeted at age 8–12 where both children and parents completed 10 modules each. Outcome measures found significant large effect sizes on child-rated symptoms and significant improvements on a number of other measures such as quality of life, pain intensity, school attendance, anxiety and depression. Lalouni et al. (Citation2021) completed a mediation analysis and found that high levels of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety and gastrointestinal-specific avoidance were associated with larger effects on parent-reported abdominal symptoms.

While the research into DARweb and the research by Lalouni and colleagues involved separate parent and child content, Bonnert et al. (Citation2019) involved sessions where parent and child attended together. Bonnert et al. (Citation2019) used an internet-based exposure intervention, where parents and children attended all sessions together. There were large significant effects on pain intensity and gastrointestinal symptoms. However, this study used an uncontrolled design. In contrast to DARweb studies and research by Lalouni and colleagues web-based interventions, this study was targeted at adolescents, aged 13–17. This is interesting as in the CBT interventions delivered face-to-face, there was less parental involvement with this age group, yet parents were heavily involved in this study.

While the interventions described above were exclusively web based, Cunningham et al. (Citation2018) evaluated a treatment called Aim to Decrease Anxiety and Pain Treatment (ADAPT) which involved two in-person sessions and four web-based sessions, as well as weekly 15 minute phone calls with a therapist. One session focused on parent guidelines related to the pain and calls involved a review of skills learned and experience of pain and anxiety.

One study involved the use of telephone-based intervention. Levy et al. (Citation2017) used a brief telephone-delivered CBT intervention delivered to parents, and compared this to a control group. This study, unlike others, did not involve children in the intervention, and was exclusively parent based. The study also used a large-sample size of 316. There were significant improvements in the treatment group in relation to parental solicitousness, pain beliefs and catastrophising, and parent reported pain behaviours, functional disability and visits to child healthcare services. There were no significant effects on pain severity. Many of the studies mentioned earlier reported decreased pain severity following intervention.

Therefore, the studies into remotely delivered CBT interventions, like the other modes of CBT delivery, are considerably varied in terms of age range and in relation to how parents are involved in the intervention. What can be understood from the remotely delivered interventions is that they vary considerably in terms of the degree of parental involvement. The parental involvement in these intervention focuses on parental responses to pain, communication styles, and strategies for promoting well-behaviours. There is also emerging evidence from Levy et al. (Citation2017) of telephone interventions being similarly effective to in-person interventions. Further research could compare web-based interventions to in-person interventions for RAP.

Cognitive behavioural family interventions

Four studies identified their intervention as Cognitive Behavioural family interventions (CBFI). Sanders et al. (Citation1994) compared a CBFI to standard paediatric care and reported that those receiving CBFI had lower levels of relapse and improvements on engagement of activities of daily living. Sanders et al. (Citation1996) examined predictors of clinical improvement and found that those with the greatest reductions on self-reported pain were those whose mothers used more adaptive care-giving strategies or where stress was a precipitator.

Another randomized controlled trial involved comparison of CBFI and standard medical care to standard medical care alone, where parents attended three out of five offered sessions (Robins et al., Citation2005). Parents were provided with information on the stress-pain connection and shown relaxation techniques. The aim was to encourage active management of pain and results showed that those who completed CBFI reported significantly less abdominal pain and better school attendance. While these studies have identified themselves as CBFI, their involvement of parents in interventions is similar to what is discussed in other CBT interventions with this population.

Sieberg et al. (Citation2011), however, compared CBT to Family CBT in children with co-morbid RAP and anxiety disorders. In the family CBT condition, parents were involved with the aim of improving family members’ understanding of their children's difficulties. After treatment, no significant group differences were found, however, this study used a very small sample size, with only four participants in each condition, limiting ability to uncover group differences.

Guided imagery

Two studies involved use of guided imagery as a treatment for RAP, both of which involved parents as indirectly involved in the intervention. Ball et al. (Citation2003) completed a pilot study where each child attended four 50-minute sessions focused on deep abdominal breathing, muscle group relaxation, and once relaxed, completing a guided imagery exercise. The study reported decreases in number of days with an episode of pain following intervention. Weydert et al. (Citation2006) compared those who learned guided imagery with progressive muscle relaxation to those who learned breathing exercises alone. The study found those learning guided imagery had significantly greater decrease in days with pain and decrease in days with missed activities. Both studies were brief, 4-session interventions supporting evidence for guided imagery, with indirect involvement from parents as part of the intervention. However, as parents were not directly involved in sessions, and their role was mainly in documenting how the pain progressed throughout intervention, it appears the outcomes of this study could not be attributed to parental factors, but further exploration would make this hypothesis clearer.

Hypnotherapy

Three studies involved the use of hypnotherapy as treatment for RAP, one study used individual therapy, and in two studies the intervention was delivered in a group format. Gulewitsch et al. (Citation2012) completed an intervention called “Sun in the belly” comprising 2 parent sessions and 2 child sessions. Participants showed decrease in frequency of pain and impairment, and improved health-related quality of life, with parents reporting strategies taught as helpful.

In another study, Gulewitsch et al. (Citation2013) used a hypnotherapeutic-behavioural group intervention where children participated in 2 hypnotherapy sessions and parents attended 2 sessions comprised information about functional gastrointestinal disorders and their links to stress and anxiety, discussion of triggers and information about management strategies related to operant learning mechanisms.

A recent study by Pas et al. (Citation2020), however, compared the use of hypnotherapy with the use of hypnotherapy plus a pain neuroscience education programme for children. In this study, the control group received 2 sessions of hypnotherapy, and the experimental group received one hypnotherapy session and PNE4Kids which involved an explanation and reassurance on the cause of pain, summary of pain mechanisms and the role of factors which precipitate and maintain pain. In both conditions, parents attended sessions, however they did not interact. This study found no significant differences between the groups, concluding that combining PNE4Kids did not result in better clinical outcomes. As parents were indirectly involved in this study, again it is difficult to conclude the impact of parental involvement.

Multi-component

Two studies used a multi-component therapeutic approach, comparing these two studies is difficult considering how their approach and methods are very different. Finney et al. (Citation1989) reported that interventions were tailored for each patient, with all participants completing self-monitoring, and others completing some or all of other components. This appears to fit with what can happen in practice, where treatment is individualized depending on presenting needs. Self-monitoring involved parents keeping a record of the frequency of pain discussions that occurred with their child. Those who completed the limited parental attention component were told to reduce their discussions of pain episodes with their children and to review their self-monitoring records during these discussions. The required school attendance component involved parents showing sympathy for their child's pain, but insisting on their child's attendance at school. It is impossible to decipher the effectiveness of each treatment component as results were not given in this way. Therefore, the impact of parental involvement here is unknown.

Humphreys and Gevirtz (Citation1999), however, completed an analysis of four treatment protocols. Sixty-four participants were randomized to receive either; 1. increased dietary-fibre only (comparison group), 2. increased dietary-fibre and biofeedback, 3. increased dietary-fibre plus biofeedback and CBT, and 4. increased dietary-fibre, biofeedback, CBT plus parental support. The addition of CBT and parental support did not increase effectiveness, and effectiveness of group 3 and group 4 showed no differences in outcomes. The study reported a mild trend for those receiving combination treatments to have poorer outcomes than those with simpler treatment options, and it was hypothesized how there was a vast amount of material in a short time which may not have allowed for appropriate learning. This type of study design, however, could be beneficial for evaluating different treatment components and evaluating the impact of parental involvement, which would increase understanding of active treatment components in interventions for RAP.

Discussion

The studies included in this review convey a vast range of parental involvement in psychological interventions for RAP in childhood. A recent Cochrane review reported on inconsistent approaches to treatment in relation to RAP (Abbott et al., Citation2017). This review highlights how parental involvement in interventions can also be inconsistent across different therapeutic modalities.

Involving parents in interventions can be effective across a number of treatment modalities. Involving parents can also appear different depending on ages, and across a variety of interventions. There is preliminary evidence related to parental involvement changing parent cognitions, and studies investigating how the addition of parent and family input impacts treatment outcomes. There is also a need for larger-scale studies, with larger-sample sizes and longer follow-up periods, in order to make these findings more robust.

Involving parents appears to be effective in facilitating therapy and improving treatment outcomes. Literature on pain and mental health research has suggested a role for parental involvement, which fits with psychological knowledge of social learning theory, modelling and reinforcement. However, while clinical experience and empirical evidence suggest parents are important, it is still unclear of what the active ingredients are in parental involvement in interventions for recurrent abdominal pain.

Future research, should investigate how parental involvement in differing treatment modalities can impact intervention outcomes. A recent Cochrane review has highlighted the need to investigate the active components to psychosocial interventions for RAP (Abbott et al., Citation2017). All studies in the Cochrane review included parental involvement to differing degrees, thus, if and how parental involvement is an active component in treatments for this presentation also need to be investigated. Research into chronic illnesses in childhood and adolescents have highlighted how parental involvement increased effectiveness (Eccleston et al., Citation2015). While Sieberg et al. (Citation2011) and Humphreys and Gevirtz (Citation1999) did examine this, more robust findings in this area are needed to decipher if parental involvement increases treatment effectiveness for RAP interventions.

It does appear that some of the studies in this review use a model of understanding the pain through psycho-education and also some studies which address parental misconceptions or cognitions about pain, as well as changing parental behaviour in how they relate to pain, and changing parental behaviour in how they support the child in their management of pain. It would be useful to evaluate how involving parents using a psycho-educational approach to pain may differ from interventions which focus on changing parental cognitions and changing parental behaviours. This would increase understanding of active components of parental involvement in interventions for RAP.

While research suggests that parental factors are important for the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders, there are mixed results in this area as to the benefits of involving parents in treatment (Wei & Kendall, Citation2014). This review however, indicates that parental involvement may be beneficial, but this remains an emerging area of research. Research on anxiety interventions indicate that parent training, parental anxiety management and transfer of control can be beneficial aspects of parental involvement (Wei & Kendall, Citation2014). While aspects of these appear to be used as part of parental involvement in RAP interventions, how effective, or not, these components are in improving treatment outcomes remains unknown.

Strengths of this review include providing increased awareness of the role that parents can play in interventions, and that parental role in interventions should be evaluated as to whether this enhances intervention outcomes or not. Another strength is that it examines across many different treatment modalities to decipher how parents are involved across different types of treatment. Limitations include that as studies were so varied and involved parents in many different ways, there was a lack of consistency in how treatment outcomes are measured. There were difficulties evaluating how specific parental involvement impacted interventions. Another limitation is that very few studies included direct examination of how parental involvement impacted the intervention, highlighting the need for more robust research in this area.

In relation to clinical implications, clinicians should consider the variety of ways that parents can be involved in interventions for RAP across different modalities. As research remains unclear as to if and how parental involvement improves treatment outcomes, clinicians should seek feedback from families as to helpful components of interventions and consider these when developing interventions. Clinicians may also decide to involve parents differently in interventions on a case-by-case basis.

In terms of research implications, there is a clear need to investigate the active components in interventions and then target these in psychosocial interventions for RAP. In addition to this, parental mediators to treatment outcomes should also be investigated. While a small number of studies have begun to explore mediating factors, there is a need for much more robust findings in this area. It would also be worth investigating how parental changes, as a result of their involvement, mediate child outcomes. Another area of useful research would be further examining parental changed responses to pain versus child changed responses to pain using different intervention components, and then focusing treatments on the more effective strategies.

Conclusion

Psychological interventions for RAP are quite varied across different therapeutic modalities, and how these treatments are delivered, either in individual, group or family format, or in-person or remotely delivered. In addition to this, parental involvement in interventions is also considerably varied. Studies which detail parental involvement typically cover psycho-education about RAP, covering maintenance factors, and using operant strategies to manage the impact of pain on children and their families’ lives. In contrast, some studies have very limited involvement of parents in interventions. Mechanisms of change remain unclear, not just at the level of intervention for the child, but in how parental involvement impacts treatment. To date, there has been no robust research around how parental involvement in interventions impact treatment outcomes, and as this review highlights, this area would be worth investigating in order to improve upon psychological service delivery in this area. As active components are investigated, these can then be targeted in the continued development of psychological interventions for RAP.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alannah McGurgan

Dr Alannah McGurgan is a Clinical Psychologist currently working in Adult Intellectual Disability Services in the Western Health and Social Care Trust. This research was completed as part of Alannah's Doctorate in Clinical Psychology at Trinity College Dublin.

Charlotte Emma Wilson

Dr Charlotte Wilson is a Clinical Psychologist and an Assistant Professor in Clinical Psychology based in Trinity College Dublin.

References

- Abbott, R. A., Martin, A. E., Newlove-Delgado, T. V., Bethel, A., Thompson-Coon, J., Whear, R., & Logan, S. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), 25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010971.pub2

- Ball, T. M., Shapiro, D. E., Monheim, C. J., & Weydert, J. A. (2003). A pilot study of the use of guided imagery for the treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children. Clinical Pediatrics, 42(6), 527–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000992280304200607

- Bonnert, M., Olén, O., Lalouni, M., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Särnholm, J., Serlachius, E., & Ljótsson, B. (2019). Internet-Delivered Exposure-Based cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents With functional abdominal pain or functional dyspepsia: A Feasibility study. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 177–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.05.002

- Bufler, P., Gross, M., & Uhlig, H. H. (2011). Recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(17), 295–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2011.0295

- Calvano, C., Groß, M., & Warschburger, P. (2017). Do mothers benefit from a child-focused cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for childhood functional abdominal pain? A randomized controlled pilot trial. Children, 4(2), 13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/children4020013

- Chambers, C. T. (2003). The role of family factors in pediatric pain. In P. J. McGrath, & G. A. Finley (Eds.), Context of Pediatric pain: Biology, family, culture (pp. 99–130). IASP Press.

- Cunningham, N. R., Nelson, S., Jagpal, A., Moorman, E., Farrell, M., Pentiuk, S., & Kashikar-Zuck, S. (2018). Development of the Aim to Decrease Anxiety and Pain Treatment for Pediatric functional abdominal pain disorders. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, 66(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000001714

- Deacy, A. D., Friesen, C. A., Staggs, V. S., & Schurman, J. V. (2019). Evaluation of clinical outcomes in an interdisciplinary abdominal pain clinic: A retrospective, exploratory review. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 25(24), 3079–3090. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i24.3079

- Eccleston, C., Fisher, E., Law, E., Bartlett, J., & Palermo, T. M. (2015). Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4(4), CD009660. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub3

- Finney, J. W., Lemanek, K. L., Cataldo, M. F., Katz, H. P., & Fuqua, R. W. (1989). Pediatric psychology in primary health care: Brief targeted therapy for recurrent abdominal pain. Behavior Therapy, 20(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80074-7

- Groenewald, C. B., & Palermo, T. M. (2015). The price of pain: The economics of chronic adolescent pain. Pain Management, 5(2), 61–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.14.52

- Groß, M., & Warschburger, P. (2013). Evaluation of a cognitive–behavioral pain management program for children with chronic abdominal pain: A randomized controlled study. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(3), 434–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9228-3

- Gulewitsch, M. D., Müller, J., Hautzinger, M., & Schlarb, A. A. (2013). Brief hypnotherapeutic–behavioral intervention for functional abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in childhood: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Pediatrics, 172(8), 1043–1051. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-013-1990-y

- Gulewitsch, M. D., Schauer, J. S., Hautzinger, M., & Schlarb, A. A. (2012). Therapy of functional abdominal pain in childhood. Concept, acceptance and preliminary results of a short hypnotherapeutic-behavioural intervention. Schmerz (Berlin, Germany), 26(2), 160–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-011-1139-8

- Hoekman, D. R., Rutten, J. M., Vlieger, A. M., Benninga, M. A., & Dijkgraaf, M. G. (2015). Annual costs of care for pediatric irritable bowel syndrome, functional abdominal pain, and functional abdominal pain syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics, 167(5), 1103–1108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.058

- Humphreys, P. A., & Gevirtz, R. N. (1999). Treatment of recurrent abdominal pain: Components analysis of four treatment protocols. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 31(1), 47–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00005176-200007000-00011

- Lalouni, M., Hesser, H., Bonnert, M., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Serlachius, E., Olén, O., & Ljótsson, B. (2021). Breaking the vicious circle of fear and avoidance in children with abdominal pain: A mediation analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 140, 110287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110287

- Lalouni, M., Ljótsson, B., Bonnert, M., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Högström, J., Serlachius, E., & Olén, O. (2017). Internet-Delivered Cognitive behavioral therapy for children With pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders: Feasibility study. JMIR Mental Health, 4(3), e32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.7985

- Levy, R. L., Langer, S. L., Romano, J. M., Labus, J., Walker, L. S., Murphy, T. B., Tilburg, M. A., Feld, L. D., Christie, D. L., & Whitehead, W. E. (2014). Cognitive mediators of treatment outcomes in pediatric functional abdominal pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 30(12), 1033–1043. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000077

- Levy, R. L., Langer, S. L., van Tilburg, M., Romano, J. M., Murphy, T. B., Walker, L. S., Mancl, L. A., Claar, R. L., DuPen, M. M., Whitehead, W. E., Abdullah, B., Swanson, K. S., Baker, M. D., Stoner, S. A., Christie, D. L., & Feld, A. D. (2017). Brief telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy targeted to parents of children with functional abdominal pain: A randomized controlled trial. Pain, 158(4), 618–628. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000800

- Levy, R. L., Langer, S. L., Walker, L. S., Romano, J. M., Christie, D. L., Youssef, N., DuPen, M. M., Ballard, S. A., Labus, J., Welsh, E., Feld, L. D., & Whitehead, W. E. (2013). Twelve-month follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with functional abdominal pain. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(2), 178–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.282

- Levy, R. L., Langer, S. L., Walker, L. S., Romano, J. M., Christie, D. L., Youssef, N., DuPen, M. M., Feld, A. D., Ballard, S. A., Welsh, E. M., Jeffery, R. W., Young, M., Coffey, M. J., & Whitehead, W. E. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents decreases pain and other symptoms. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 105(4), 946–956. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.106

- Logan, D. E., & Scharff, L. (2005). Relationships between family and parent characteristics and functional abilities in children with recurrent pain syndromes: An investigation of moderating effects on the pathway from pain to disability. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(8), 698–707. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj060

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K., & Mu, P. F. (2020). Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis (p. 5). JBI, 2020. Available from https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687372/Chapter+7%3A+Systematic+reviews+of+etiology+and+risk

- Nieto, R., Boixadós, M., Hernández, E., Beneitez, I., Huguet, A., & McGrath, P. (2019a). Quantitative and qualitative testing of DARWeb: An online self-guided intervention for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents. Health Informatics Journal, 25(4), 1511–1527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458218779113

- Nieto, R., Boixadós, M., Ruiz, G., Hernández, E., & Huguet, A. (2019b). Effects and experiences of families following a Web-based psychosocial intervention for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents: A mixed-methods pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain Research, 12, 3395–3412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S221227

- Nieto, R., Hernández, E., Boixadós, M., Huguet, A., Beneitez, I., & McGrath, P. (2015). Testing the Feasibility of DARWeb. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(6), 493–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000199

- Nieto, R., Sora, B., Boixadós, M., & Ruiz, G. (2020). Understanding the experience of functional abdominal pain through written narratives by families. Pain Medicine, 21(6), 1093–1105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz147

- Pas, R., Rheel, E., Van Oosterwijck, S., Foubert, A., De Pauw, R., Leysen, L., Roete, A., Nijs, J., Meeus, M., & Ickmans, K. (2020). Pain neuroscience education for children with functional abdominal pain disorders: A randomized comparative pilot study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(6), 1797. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061797

- Plunkett, A., & Beattie, R. M. (2005). Recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 98(3), 101–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680509800304

- Robins, P. M., Smith, S. M., Glutting, J. J., & Bishop, C. T. (2005). A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(5), 397–408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsi063

- Sanders, M., Morrison, M., Rebgetz, M., Bor, W., Dadds, M., & Sheperd, R. (1990). Behavioural treatment of childhood recurrent abdominal pain: Relationships between pain, children’s psychological characteristics and family functioning. Behaviour Change, 7(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0813483900007373

- Sanders, M. R., Cleghorn, G., Shepherd, R. W., & Patrick, M. (1996). Predictors of clinical improvement in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 24(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800016817

- Sanders, M. R., Rebgetz, M., Morrison, M., Bor, W., Gordon, A., Dadds, M., & Shepherd, R. (1989). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of recurrent nonspecific abdominal pain in children: An analysis of generalization, maintenance, and side effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 294–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.2.294

- Sanders, M. R., Shepherd, R. W., Cleghorn, G., & Woolford, H. (1994). The treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children: A controlled comparison of cognitive-behavioral family intervention and standard pediatric care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(2), 306–314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.2.306

- Schurman, J. V., & Friesen, C. A. (2010). Integrative treatment approaches: Family satisfaction with a multidisciplinary paediatric abdominal pain clinic. International Journal of Integrated Care, 10(10), e51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.551

- Sieberg, C. B., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Plante, W. (2011). Children with co-morbid recurrent abdominal pain and anxiety disorders: Results from a multiple-baseline intervention study. Journal of Child Health Care: For Professionals Working with Children in the Hospital and Community, 15(2), 126–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493511401640

- Van der Veek, S. M., Derkx, B. H., Benninga, M. A., Boer, F., & de Haan, E. (2013). Cognitive behavior therapy for pediatric functional abdominal pain: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1163–e1172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0242

- Van Oudenhove, L., Levy, R. L., Crowell, M. D., Drossman, D. A., Halpert, A. D., Keefer, L., Lackner, J. M., Murphy, T. B., & Naliboff, B. D. (2016). Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: How central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1355–1367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.027

- Warner, M., Reigada, C., Fisher, L. C., Saborsky, P. H., & Benkov, A. L., & J, K. (2009). CBT for anxiety and associated somatic complaints in pediatric medical settings: An open pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 16(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-008-9143-6

- Wei, C., & Kendall, P. C. (2014). Parental involvement: Contribution to childhood anxiety and its treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(4), 319–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-014-0170-6

- Weydert, J. A., Ball, T. M., & Davis, M. F. (2003). Systematic review of treatments for recurrent abdominal pain. Pediatrics, 111(1), e1–e11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.e1

- Weydert, J. A., Shapiro, D. E., Acra, S. A., Monheim, C. J., Chambers, A. S., & Ball, T. M. (2006). Evaluation of guided imagery as treatment for recurrent abdominal pain in children: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatrics, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-6-29

- Zucker, N., Mauro, C., Craske, M., Wagner, H. R., Datta, N., Hopkins, H., Caldwell, K., Kiridly, A., Marsan, S., Maslow, G., Mayer, E., & Egger, H. (2017). Acceptance-based interoceptive exposure for young children with functional abdominal pain. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 97, 200–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.009