ABSTRACT

In recent years, and especially due to COVID-19, a large number of telehealth interventions have been implemented. The large amount of information requires a differential analysis with an emphasis on rurality and the practice of parents/caregivers in the care and attention of children. The objectives of this study were to synthesize the available evidence on telehealth interventions aimed at parents and caregivers of children living in rural settings, and to identify relevant methodological aspects that are considered in such interventions. A systematic review was conducted in the Medline (Ovid), Embase, Scopus, APA—PSYCNET, Web of Science and LILACS databases. Studies published between 2000 and 2020 were considered. A narrative synthesis of the main results of the studies was performed, including basic characteristics, details of the interventions, and the main outcome measures. The quality of the studies included was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools. A total of 596 potential studies were identified, of which only nine were included. Quality assessment was consistent in all nine studies. Parents and caregivers of children with speech and language impairment, motor impairment or problems in performing activities of daily living, with behavior problems, and with autism spectrum disorder were the main populations groups benefiting from the interventions. Telehealth interventions were implemented by means of online sessions, pre-recorded sessions and self-learning modules, among others. Results, although variable, evidence positive outcomes regarding the development of multiple skills in children, their parents and family members, as well as the opportunity to provide timely access to health services. Finally, Telehealth is increasingly becoming a useful tool to provide counsel and knowledge to parents and caregivers living in rural areas that will enable them to properly manage health problems.

Introduction

Telehealth is known as the possibility of providing health care, health education and health counseling services remotely through different information and communications technologies including videoconferencing, mobile connection applications, and monitoring and assistance tools, among others (Catalyst, Citation2018; Waller & Stotler, Citation2018). Although the terms telehealth and telemedicine have been used interchangeably, the former comprises a large number of services that improve the quality of health care, access to health services, the productivity of health workers, increased health access coverage in rural areas, reduced healthcare provision-related costs, and even facilitate the provision of such services during health crises such as the current COVID-19 pandemic (Smith et al., Citation2020; Koonin et al., Citation2020).

By March 2021, a search in the Medline (PubMed) database using the “telehealth” and “telemedicine” terms yielded more than 35,000 records, of which, 54% have been published in the last five years, which makes it evident that not only publications addressing this topic, but also the use of telehealth has increased. Within these records, there are many related to technology, intervention programs, innovations in infrastructure, new adaptations such as simulated use and 3D, among others. Furthermore, it is worth noting that, at least in the United States, more than 50% of health institutions have some telehealth program (Tuckson et al., Citation2017), and that the number of specialized services using this technology is increasing, including telepsychiatry, teleophthalmology, telerehabilitation, and recently, even teletherapy (Fairweather et al., Citation2022).

Multiple studies and reviews have shown the benefits of telehealth, particularly in the rural context. Telehealth has overcome physical displacement, geographical and technological barriers and has had a positive impact on many processes involved in the provision of health services in rural areas (Jennett et al., Citation2003).

Additionally, it is considered as one of the necessary tools for the provision of specialized health services to people living in remote areas (Jarvis-Selinger et al., Citation2008; Jennett et al., Citation2003), to those living in vulnerable communities and in those where the general health status is worse, and/or who lack the necessary resources to go to a hospital for assistance (Smith et al., Citation2008; Moffatt & Eley, Citation2010). It is considered a necessary tool for providing health care services to all those who live in remote areas, which is estimated to be more than 44% of the world population, as more than half of them need health care services (World Bank Group, Citation2019; Mikou et al., Citation2019).

Thus, rurality is understood as the population, housing, context and sociocultural development that implies living outside an urban area or urban cluster, having a population of less than 10,000 people or living in places with limited access to public services due to geographical barriers (Hart et al., Citation2005; Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Citation2021).

In this sense, rural populations with the above conditions have been benefiting more frequently from the use of telehealth in terms of access to health services; in recent years, the satisfaction of this population with this technology has been measured by several studies, which have reported significant positive outcomes, including the reduction of waiting times for receiving care, the avoidance of exhausting and costly trips, and the reduction of the burden on the family members of patients, among others, as they are no longer required to go to intermediate or large cities (Orlando et al., Citation2019).

The general characteristics of telehealth interventions in the rural context include the possibility of receiving health assistance via videoconference, completing specific forms and questionnaires live, evidencing current health needs, and actively interacting with trained health professionals (Fischer et al., Citation2020; Speyer et al., Citation2018; Tuckson et al., Citation2017).

Regarding the place where this technology is used, it has been described that telehealth interventions are usually carried out in local schools and primary care centers or hospitals, which involves the mobilization of people even in rural areas (Campbell et al., Citation2020; Hilty et al., Citation2020). Among the population groups using telehealth in rural areas, it has been reported that there is a great diversity of groups that benefit from it (Disler et al., Citation2020; Hilty et al., Citation2020) including the family, and especially children, one of the most important target populations at present (Harrison et al., Citation2014; Hilty et al., Citation2020).

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a new challenge for parents and caregivers of children since, given the measures implemented to slow down the transmission of the virus, their possibility of attending schools and other care centers has been limited (Cruz & Zeichner, Citation2020) although this situation has been questioned lately (Ludvigsson, Citation2020). In fact, according to data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), worldwide more than 1.5 billion students have been affected by the physical closing of schools and universities, while 9.4% of the world population have been affected by the closing of schools alone (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, Citation2021). As time passes, we obtain more data that allows the measurement of the negative impact of the current pandemic on the well-being, development and health of children around the world (Van Lancker & Parolin, Citation2020; Xiang et al., Citation2020).

The pandemic has not only affected children, but also their parents and caregivers, especially those who are socioeconomically vulnerable, a situation which was worsened by the pandemic (unemployment, informal employment, etc.), and/or live in remote or rural areas, since they generally don’t have the time or financial resources to support the learning processes of their children, nor the minimum tools to support, with the help of a health professional, the mental, physical, social and relational well-being of their children (Masonbrink & Hurley, Citation2020; Van Lancker & Parolin, Citation2020).

The reasons for conducting this review are summarized in the different abovementioned sections. Firstly, we are aware of the general and specific benefits of telehealth in rural areas. Secondly, we are currently facing a pandemic that tests the development, use and application of this technology in the general population. In this sense, children, together with their parents, have been one of the population groups most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, since their roles at home have been modified, thus affecting different skills related to the fulfillment of children’s health, educational and social development needs, among others.

Finally, understanding the above scenario in rural communities, as well as their vulnerability, makes it necessary to rethink how telehealth interventions can be improved in the context of global health crises such as the current pandemic. The final aspect is the information gap that we identified regarding rural telehealth interventions that do not require the mobilization of people, even to physical spaces (e.g. local schools or primary care centers) in their rural communities.

Therefore, The objectives of this study were to synthesize the available evidence on telehealth interventions aimed at parents and caregivers of children living in rural settings, and to identify relevant methodological aspects that are considered in such interventions.

Methods

Design

A systematic review was conducted following the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., Citation2019) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Study selection criteria

- Types of participants: parents and caregivers of children aged 2–12 years or parent/caregiver-child dyads.

- Types of interventions: Telehealth, telemedicine, telerehabilitation, telecare interventions and/or interventions derived from the practice of medicine and/or health sciences to deliver care at a distance by means of video and audio tools.

- Types of outcome: The basic characteristics of the studies, the intervention details and the main outcome measures will be described.

- Types of studies: All types of primary studies are included.

- Context: Studies focused on the implementation of these interventions in rural settings. Due to the possible variability of the term “rural” in different countries, studies that explicitly stated that the intervention was carried out outside major cities or places considered as urban areas or in places with limited access to public and private services due to geographic aspects were included.

- Exclusions: Interventions that involved the mobilization of participants to training centers (schools) or health centers (rural primary care centers) or any other institution, or their physical attendance to a meeting held in a specific location, even if such places were located in rural areas.

Search methods

An advanced search was carried out in January 2021; studies published between January 2000 and December 2020 were considered. The search was conducted in the following databases: Medline (OVID), Embase, Scopus, APA—PSYCNET, Web of Science, and LILACS. The search strategy was based on the use of controlled and free terms such as “parent”, “father”, “mother”, “caregiver” with “child” and “children” for the population group, and “telemedicine”, “telehealth”, “telecare”, “remote consultation” with “rural” for the intervention. Studies published in languages other than English were not included. The full search strategy and search reports are presented in Appendix 1.

Search by other resources

A complementary search was carried out in Google Scholar; likewise, a snowball search was also conducted.

Data extraction and analysis

Studies were independently selected by two authors after reading their titles and abstracts, as well as by performing a full-text reading; disagreements were solved through open discussion. Finally, the data of the selected studies were extracted independently by other two other authors who used a standardized format for such purpose. The meta-aggregation synthesis of the evidence was based on the identification of similarities between the documents that were retrieved, and a categorical analysis of the information was performed by establishing variables and making comparisons between studies in terms of study population, objective of the intervention, type of intervention and outcome measurements. The analysis was conducted with an emphasis on interventions and results, thus promoting a comprehensive view of the evidence.

Quality evaluation

The risk of bias of the selected studies was assessed by four authors using the Joanna Briggs Institute tools, particularly the critical appraisal criteria for Quasi-experimental studies (Tufanaru et al., Citation2020), Qualitative research (Lockwood et al., Citation2015) and Case series (Munn et al., Citation2020).

Data synthesis

A description of the results of each study was made by emphasizing the basic characteristics of each one (referencing data, country, participants, specific setting), the details of the intervention (objective and operational details), and the main outcome measures. Due to the high heterogeneity among the studies selected, a pooled analysis of results was not possible.

Results

Search results

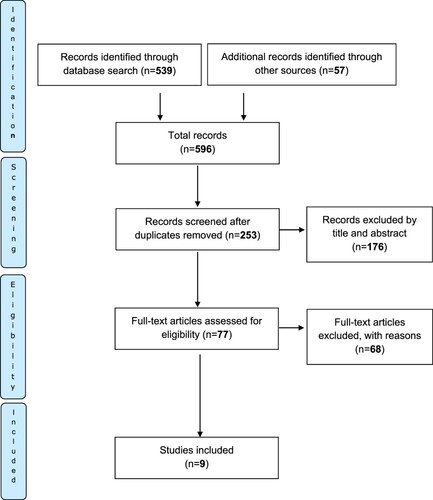

The initial search yielded a total of 596 records; after duplicates were removed, 253 studies were screened by reading their titles and abstracts; of these, 77 were selected for full-text reading, and 68 were rejected for inclusion due to specific reasons, which are described in Appendix 2. Finally, nine studies were included for full analysis (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). The screening and selection process of studies is shown in in accordance with the PRISMA standards.

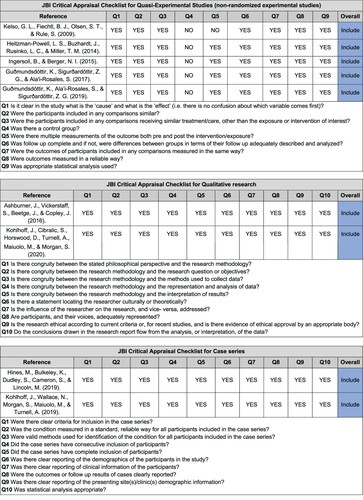

Quality evaluation results

All nine studies were evaluated and included according to the assessment tools; the specific details of this evaluation are described in . There were five quasi-experimental studies (Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009) none of them had a control group, and only one (Kelso et al., Citation2009) did not report multiple measurements; in addition, all of them properly reported the measurements, how their samples were obtained, and the statistical analysis of data according to the study design proposed.

As for the qualitative studies (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2020), they fully complied with the items evaluated by the assessment tool, obtaining outstanding results in terms of research methodology, social representation and the resulting analysis. Finally, case series studies (Hines et al., Citation2019; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019), fully reported the proposed evaluation, being noteworthy the inclusion criteria, the identification of the methods used and of participants, together with the most relevant results, which were correctly analyzed.

General characteristics

Regarding study design, as noted above, five were quasi-experimental two, qualitative (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2020) and two, case series (Hines et al., Citation2019; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019). Most of them (44%) were conducted in Australia (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Hines et al., Citation2019; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), followed by the United States of America (33%) (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009) and Iceland (Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

All studies included in this review comprised a total of 64 parents and caregivers along with 15 nuclear families. Regarding the specific characteristics of participants, children with any kind of speech and language impairment, motor impairment or problems in performing activities of daily living (Kelso et al., Citation2009), with behavior (control or reaction-related) problems (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), and with autism spectrum disorder (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015). Further information is presented in .

Table 1. General characteristics and population of the studies.

Interventions

The interventions reported by the nine studies, as well as the means used for their implementation, are described in . Interventions varied in including speech and language therapy, occupational therapy and physical therapy activities and services (Kelso et al., Citation2009), as well as psychology and specific behavioral interventions (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020) and actions aimed at providing knowledge and training on the management of the autism spectrum disorder variability (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015).

Table 2. Main interventions, means and results.

Intervention actions focused on providing training and counseling with the purpose of achieving the early promotion of different skills including language, daily living activities and behavior through multiple strategies carried out by therapists and that considered the context of the family as a social unit (Kelso et al., Citation2009).

Regarding behavioral interventions, a parent–child interaction therapy program based on behavioral learning, attachment theory and social-emotional aspects was identified; the goals of said intervention were to improve the quality of the parent–child relationship, to provide parents with skills for the adequate management of child behavior problems, and to provide them with proper knowledge about the characterization of child behavior so that they were able to treat their behavior adequately (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019). In addition, another study reporting an intervention with a similar structure was also identified; in this case, however, the intervention included the training of parents or caregivers to give direct orders and develop skills related to positive parenting, language improvement and the provision of differential care of problematic behaviors in children (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2020)

Regarding autism, the component most frequently addressed by the studies included in this review, an online training program on autism and ABA (applied behavior analysis) procedures known as OASIS (Online and Applied System for Intervention Skills) was identified. This program was composed of eight modules that allowed online participation and included online activities addressing generalities of autism, ABA procedures, how to control challenging behaviors, and the development of skills for their proper management (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014).

Another online training program known as ImPACT Online was also identified: this program consisted of 12 self-learning lessons that required participants to dedicate more than 80 min for successful completion; the intervention was designed to be implemented in only one group which was asked to log in to the site where the lessons were to be taken, and in another group in which a therapist held up to 24 30-min sessions per week (Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015).

Another study reported an intervention in which both face-to-face and remote programs were combined by including five daily 1.5-hour sessions with families, group intervention activities, the participation of therapists and specialized health care providers, and the promotion of behavioral management skills and communication and social interaction skills, as well as of better practices involving children’s feeding, play engagement, emotions, and independence (Ashburner et al., Citation2016).

Other programs consisted of, on the one hand, reality-based behavioral and social-communicative interventions aimed at parents and adapted from previous interventions such as Sunny Starts Teaching; and, on the other, the teaching of specific components based on parent and child components of decision, organization, current response, evaluation, and contemplation (Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2019). Finally, collaborative coaching emerges as a technique that seeks parents and teachers to develop a series of skills necessary for the management and care of children (Hines et al., Citation2019).

The technological tools most commonly used included cameras, microphones, loudspeakers and computers, the latter owned by the families (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020) or provided by those responsible for conducting the study (Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015), as well as smartphones and tablets (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020).

On the other hand, the main means used to perform such interventions included general videoconferencing (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015), web conferencing (Kelso et al., Citation2009; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019), self-learning modules (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014) and live video teleconferencing (VTC) for telehealth purposes (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2020). Finally, Skype (Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015), Health Direct Video Call (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), Macromedia Breeze and Adobe Connect Pro (Kelso et al., Citation2009), Cisco WebEx Meeting Center™ (Ashburner et al., Citation2016) and Learning Management Systems (LMS) (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014) were the programs most frequently used.

Outcomes

Different outcomes were identified in the interventions reported by the nine studies. Parents reported having learned new therapeutic techniques for the comprehensive development and substantial improvement of communication with their children (Kelso et al., Citation2009). Regarding behavioral management, the reduction of disruptive behaviors to non-clinical levels, a decreased frequency of behavioral crises, and a higher level of trust between parents and children were reported (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019). In addition, according to another study, the main outcomes included substantial improvements in children's behaviors, parental well-being and family relationships (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2020).

Regarding studies focusing on children with autism spectrum disorder, an increased level of knowledge by parents (a 39 percentage points increase) and a significant improvement in the implementation of procedures (a 41.23 percentage points increase) was evidenced after the intervention (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014). Other results include the fact that the mediation of a therapist in the intervention allows for a higher program completion rate (p = 0.03) and that parents attended more content lessons along with activity lessons (p = 0.05) (Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015). Furthermore, qualitative analyses reported that parents indeed improve their skills with the help of health care providers, and that they prefer support to and from home, together with the improvement of family relationships (Ashburner et al., Citation2016).

Furthermore, results here identified confirmed the potential of telehealth as a mediator for achieving the acquisition of knowledge, improving the skills of families, increasing their access to evidence-based interventions, and improving the skills of children, especially social skills, thus obtaining positive responses in everyday life (Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

Other findings included being able to refer to and review session recordings at different times (Kelso et al., Citation2009), the parents’ preference for leading the interaction with children (Kelso et al., Citation2009) and the parents’ perceived high or very high overall satisfaction with the interventions (Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009). In relation to the technology used, parents expressed concerns with technological tools such as computer accessories and peripherals (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Kelso et al., Citation2009) and Internet connection (Ashburner et al., Citation2016). However, and despite such concerns, they preferred and recommended the use of these technologies as an approach to modernity (Kohlhoff et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

Undoubtedly, the literature on telemedicine, as well as its uses and applications have changed over time due to technological advances (Marcin et al., Citation2015) but above all due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Smith et al., Citation2020; Wosik et al., Citation2020). For this reason, given the scarce information about telehealth interventions in rural settings, and as an extended response to the current pandemic, we conducted a systematic search of studies published between 2000 and 2020 reporting the implementation of telehealth interventions aimed at parents and caregivers of children living in rural areas and that did not require them to mobilize to a rural health center or educational institution.

In general, it was found that most interventions consisted of online or videoconference sessions, specifically designed teleconferences, pre-recorded sessions, self-learning modules, among other tools. Likewise, interventions were focused on the development of skills in both children and parents, and main outcomes included the enhancement of independence, communication, behavior management and daily life skills of children, their parents, relatives and caregivers.

In this review only a few studies reporting telehealth interventions met the inclusion criteria and the objective of the study and thus were included for analysis (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). This is a relevant finding, since this panorama had been previously suggested by Banbury et al. (Banbury et al., Citation2018) who reflected on the potential of videoconferencing to reach homes located not only in urban but also in rural areas.

It should be noted that the low number of studies included in this review may be explained by the situation reported by Bradford et al. (Bradford et al., Citation2016) who described a low reporting trend despite identifying a wide range of health services (especially medical specialties) using this technology in Australia or, as it has been proposed, by the fact that, unfortunately, projects aimed at bringing telehealth to rural areas are not properly identified in middle or low-income countries where, in fact, this technology is needed the most (Combi et al., Citation2016).

As for the interventions, these predominantly consisted of videoconferences or audio and video calls (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Kelso et al., Citation2009; Kohlhoff et al., Citation2019) a trend that has already been described as the best option at the time (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Campbell et al., Citation2020; Orlando et al., Citation2019).

In relation to the devices used, it was evident that computers continue to be the most used and that tablets or smartphones are used to a lesser extent (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Campbell et al., Citation2020). In this regard, although a possible increase in the use of the latter had been noted (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Bradford et al., Citation2016), as of the cut-off date of the search (2020), a higher use of these devices than the one already reported was not evidenced. Regarding the technological structure used to reach rural areas, all nine studies reported the use of a common infrastructure focused on the possibilities of rural Internet (Campbell et al., Citation2020; Orlando et al., Citation2019).

As it has been the case of other reviews, we also identified a wide range of health outcomes measures, mainly described qualitatively and/or suggested by parents in relation to their children (Banbury et al., Citation2018). Specifically, results are in line with what has been reported by other studies, mainly general acceptance of interventions by parents (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Bradford et al., Citation2016; Campbell et al., Citation2020; Parsons et al., Citation2017), adherence and proper use of technology (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Parsons et al., Citation2017) or specific outcomes such as skills related to communications, behavior, control of health activities, autonomy and independence (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Bradford et al., Citation2016; Brophy, Citation2017; Parsons et al., Citation2017). We then agree with multiple perspectives that advocate for a better way of measuring outcomes right from the start of the intervention by considering both clinical and other outcomes to effectively justify the use of telehealth (Armfield et al., Citation2014; Bradford et al., Citation2016).

In terms of outcomes obtained in families with children with autism spectrum disorder, this review joins a set of reviews that state the possibility of improving behavioral, socioemotional, and communication skills using telehealth as a valid alternative (Ashburner et al., Citation2016; Guðmundsdóttir et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Heitzman-Powell et al., Citation2014; Hines et al., Citation2019; Ingersoll & Berger, Citation2015; Parsons et al., Citation2017). Although we are aware that this topic must be extensively addressed in the rural setting, we believe this is a first approach to the autism spectrum disorder-rural setting relationship and to develop specific interventions aimed at parents in this situation (Parsons et al., Citation2017). Other outcomes such as satisfaction and perception of rural telehealth interventions remain underexplored despite the fact that less than two years ago the need to increase the availability of relevant literature was discussed (Orlando et al., Citation2019).

As it has been described by previous reviews, it was evident that studies included for analysis had a small sample size, which makes it moderately complex to measure the results in terms of impact. This finding was also reported by other reviews where in fact the low sample size, together with the lack of sufficient statistical power, the absence of sufficient statistics and the inclusion of repetitive data were criticized (Banbury et al., Citation2018; Brophy, Citation2017; Parsons et al., Citation2017).

Some reviews have reported the presence of technical difficulties, especially in the implementation and execution of the sessions; somehow, the studies included in this review did not report such difficulties in depth (Banbury et al., Citation2018). Therefore, a more detailed description of these problems is important to know how technological characteristics are configured in rural areas and even more in the context of remote communication (Brophy, Citation2017; Combi et al., Citation2016).

It is widely known that most high-income countries, especially those in North America, Europe and Oceania, have a greater technology infrastructure, while low- and middle-income countries face greater difficulties in providing their inhabitants with access to internet services and advanced information and communication technologies (Akhlaq et al., Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation2012). Although worldwide the use of internet, social networks and smartphones has increased in general, low- and middle-income countries still face challenges in terms of funding, identification of priorities in the provision of eHealth and mHealth services, the implementation of educational interventions aimed at achieving a proper use of technological tools, and the development of healthcare applications.

Finally, rurality must not be only considered as a geographical or infrastructure barrier, but also as an opportunity to design better interventions (eHealth and mHealth) with rurality in mind, as rural populations live in a completely different setting than most of the people for which these interventions are usually designed for. Several studies have highlighted the opportunities for telehealth to conquer spaces, contexts and services that can still be modified and adapted for the community (Shah & Badawy, Citation2021).

Limitations

As mentioned above, only studies published in English between 2000 and 2020 and indexed in the databases described in the methodology section were considered in this review, so it is likely there are other studies meeting the inclusion criteria that were not included. Another limitation was the complex definition of “rurality” as an inclusion criterion, since a large number of studies were excluded as they failed to meet such definition, especially those conducted in rural contexts but with occasional visits to rural centers or home visits, or those conducted in peri-urban areas that, in a very broad sense, could be considered as initial transition areas to rural areas.

Conclusions

Undoubtedly, telehealth is a useful tool to provide counsel and knowledge to parents and caregivers living in rural areas that will enable them to properly manage health problems affecting their children. This review compiles a series of studies describing interventions that can benefit people living in rural areas without requiring them to mobilize to specific centers, even if such places are also located in rural areas, and that can be currently used in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on the results reported here, it is possible to say that most interventions focused on therapeutic and behavioral management aids, as well as on improving the understanding of the autism spectrum disorder. In general, positive outcomes include the improvement of children’s skills to perform activities of the daily living, a better control of disruptive behaviors, improved parent–child and family relationships and functional independence, as well as the reduction of costs and waiting times to access health services, among others. Finally, rethinking the analysis of purely rural telehealth interventions is one of the most important areas for further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jaime Moreno-Chaparro

Jaime Moreno-Chaparro, OT, MSc (c). Is an Occupational Therapist and Junior Researcher of the Occupation and Social Inclusion Research Group and “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia. He's currently a MSc Candidate in Clinical Epidemiology at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Bogotá, Colombia).

Eliana I. Parra Esquivel

Eliana I. Parra Esquivel, OT, MEd, PhD. She's an Occupational Therapist, Full Professor and Researcher at the Department of Human Occupation, the Occupation and Social Inclusion Research Group and the “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Master's in education from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and PhD in Education from Universidad Santo Tomás (Bogotá, Colombia).

Angy Lucia Santos Quintero

Angy Lucia Santos Quintero, OT. She's an Occupational Therapist and Researcher of the “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Bogota, Colombia).

Laura Paez

Laura Paez, OT. She's an Occupational Therapist and Researcher of the “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Bogota, Colombia).

Sandra Martinez Quinto

Sandra Martinez Quinto, OT. She's an Occupational Therapist and Researcher of the “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Bogota, Colombia).

Bayron Esteven Rojas Barrios

Bayron Esteven Rojas Barrios, OT. He's an Occupational Therapist and Researcher of the Occupation and Social Inclusion Research Group and “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Bogota, Colombia).

Juan Felipe Samudio

Juan Felipe Samudio, OT. He's an Occupational Therapist and Researcher of the “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Bogota, Colombia).

Karol Madeline Romero Villareal

Karol Madeline Romero Villareal, Eng. She's a Biological Engineer and Researcher of the “Telehealth for Childhood Wellbeing” Research Group of the Undergraduate School, Academic Direction, Vice-rectory at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (La Paz, Colombia).

References

- Akhlaq, A., McKinstry, B., Muhammad, K. B., & Sheikh, A. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to health information exchange in low- and middle-income country settings: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 31(9), 1310–1325. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw056

- Armfield, N. R., Edirippulige, S. K., Bradford, N., & Smith, A. C. (2014). Telemedicine - is the cart being put before the horse? Medical Journal of Australia, 200(9), 530–533. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja13.11101

- Ashburner, J., Vickerstaff, S., Beetge, J., & Copley, J. (2016). Remote versus face-to-face delivery of early intervention programs for children with autism spectrum disorders: Perceptions of rural families and service providers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.011

- Banbury, A., Nancarrow, S., Dart, J., Gray, L., & Parkinson, L. (2018). Telehealth interventions delivering home-based support group videoconferencing: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(2), e25. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8090

- Bradford, N. K., Caffery, L. J., & Smith, A. C. (2016). Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: A systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural and remote health, 16(4), 3808. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH3808

- Brophy, P. D. (2017). Overview on the challenges and benefits of using telehealth tools in a pediatric population. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 24(1), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2016.12.003

- Campbell, J., Theodoros, D., Hartley, N., Russell, T., & Gillespie, N. (2020). Implementation factors are neglected in research investigating telehealth delivery of allied health services to rural children: A scoping review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(10), 590–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X19856472

- Catalyst, N. E. J. M. (2018). What is telehealth? NEJM Catalyst, 4(1). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0268

- Combi, C., Pozzani, G., & Pozzi, G. (2016). Telemedicine for developing countries: A survey and some design issues. Applied Clinical Informatics, 7(4), 1025–1050. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2016-06-R-0089

- Cruz, A. T., & Zeichner, S. L. (2020). COVID-19 in children: Initial characterization of the pediatric disease. Pediatrics, 145(6), e20200834. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0834

- Disler, R., Glenister, K., & Wright, J. (2020). Rural chronic disease research patterns in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand: A systematic integrative review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 770–777. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08912-1

- Fairweather, G. C., Lincoln, M., Ramsden, R., & Bulkeley, K. (2022). Parent engagement and therapeutic alliance in allied health teletherapy programs. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e504–e513. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13235

- Fischer, S. H., Ray, K. N., Mehrotra, A., Bloom, E. L., & Uscher-Pines, L. (2020). Prevalence and characteristics of Telehealth utilization in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), e2022302–e2022302. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22302

- Guðmundsdóttir, K., Ala’i-Rosales, S., & Sigurðardóttir, Z. G. (2019). Extending caregiver training via telecommunication for rural Icelandic children with autism. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 38(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870518783522

- Guðmundsdóttir, K., Sigurðardóttir, Z. G., & Ala'i-Rosales, S. (2017). Evaluation of caregiver training via telecommunication for rural Icelandic children with autism. Behavioral Development Bulletin, 22(1), 215–229. http://doi.org/10.1037/bdb0000040

- Harrison, J. K., Fearon, P., Noel-torr, A. H., McShane, R., Stott, D. J., Quinn, T. J. (2014). Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) for the diagnosis of dementia within a general practice (primary care) setting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 7, article number CD010771. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010771.pub2

- Hart, L. G., Larson, E. H., & Lishner, D. M. (2005). Rural definitions for health policy and research. American Journal of Public Health, 95(7), 1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). (2021). Defining rural population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html

- Heitzman-Powell, L. S., Buzhardt, J., Rusinko, L. C., & Miller, T. M. (2014). Formative evaluation of an ABA outreach training program for parents of children with autism in remote areas. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357613504992

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hilty, D. M., Gentry, M. T., McKean, A. J., Cowan, K. E., Lim, R. F., & Lu, F. G. (2020). Telehealth for rural diverse populations: Telebehavioral and cultural competencies, clinical outcomes and administrative approaches. MHealth, 6(20), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2019.10.04

- Hines, M., Bulkeley, K., Dudley, S., Cameron, S., & Lincoln, M. (2019). Delivering quality allied health services to children with complex disability via telepractice: Lessons learned from four case studies. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31(5), 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-019-09662-8

- Ingersoll, B., & Berger, N. I. (2015). Parent engagement with a Telehealth-based parent-mediated intervention program for children with autism spectrum disorders: Predictors of program use and parent outcomes. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(10), e227. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4913

- Jarvis-Selinger, S., Chan, E., Payne, R., Plohman, K., & Ho, K. (2008). Clinical telehealth across the disciplines: Lessons learned. Telemedicine and E-Health, 14(7), 720–725. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2007.0108

- Jennett, P., Jackson, A., Healy, T., Ho, K., Kazanjian, A., Woollard, R., Haydt, S., & Bates, J. (2003). A study of a rural community’s readiness for telehealth. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 9(5), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763303769211265

- Kelso, G. L., Fiechtl, B. J., Olsen, S. T., & Rule, S. (2009). The feasibility of virtual home visits to provide early intervention A pilot study. Infants and Young Children, 22(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181b9873c

- Kohlhoff, J., Cibralic, S., Horswood, D., Turnell, A., Maiuolo, M., & Morgan, S. (2020). Feasibility and acceptability of internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy for rural Australian families: A qualitative investigation. Rural and Remote Health, 20, 5306. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5306

- Kohlhoff, J., Wallace, N., Morgan, S., Maiuolo, M., & Turnell, A. (2019). Internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy: Two clinical case reports. Clinical Psychologist, 23(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12184

- Koonin, L. M., Hoots, B., Tsang, C. A., Leroy, Z., Farris, K., Jolly, T., Antall, P., McCabe, B., Zelis, C. B. R., Tong, I., & Harris, A. M. (2020). Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic —United States, January-March 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(43), 1595–1599. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3

- Lewis, T., Synowiec, C., Lagomarsino, G., & Schweitzer, J. (2012). E-health in low-and middle-income countries: Findings from the center for health market innovations. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(5), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.099820

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

- Ludvigsson, J. F. (2020). Children are unlikely to be the main drivers of the COVID-19 pandemic—A systematic review. Acta Paediatrica, 109(8), 1525–1530. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15371

- Marcin, J. P., Rimsza, M. E., & Moskowitz, W. B. (2015). The use of telemedicine to address access and physician workforce shortages. Pediatrics, 136(1), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1253

- Masonbrink, A. R., & Hurley, E. (2020). Advocating for children during the COVID-19 school closures. Pediatrics, 146(3), e20201440. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1440

- Mikou, M., Rozenberg, J., Koks, E. E., Fox, C. J. E., & Peralta Quiros, T. (2019). Assessing rural accessibility and rural roads investment needs using open source data. The World Bank.

- Moffatt, J. J., & Eley, D. S. (2010). The reported benefits of telehealth for rural Australians. Australian Health Review, 34(3), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH09794

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097–e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Munn, Z., Barker, T. H., Moola, S., Tufanaru, C., Stern, C., McArthur, A., Stephenson, M., & Aromataris, E. (2020). Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2127–2133. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

- Orlando, J. F., Beard, M., & Kumar, S. (2019). Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLoS One, 14(8), e0221848. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221848

- Parsons, D., Cordier, R., Vaz, S., & Lee, H. C. (2017). Parent-mediated intervention training delivered remotely for children with autism spectrum disorder living outside of urban areas: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(8), e198. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6651

- Shah, A. C., & Badawy, S. M. (2021). Telemedicine in pediatrics: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Pediatr Parent, 4(1), e22696. https://doi.org/10.2196/22696

- Smith, A. C., Thomas, E., Snoswell, C. L., Haydon, H., Mehrotra, A., Clemensen, J., & Caffery, L. J. (2020). Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(5), 309–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20916567

- Smith, K. B., Humphreys, J. S., & Wilson, M. G. A. (2008). Addressing the health disadvantage of rural populations: How does epidemiological evidence inform rural health policies and research? Australian Journal of Rural Health, 16(2), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.00953.x

- Speyer, R., Denman, D., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Chen, Y.-W., Bogaardt, H., Kim, J.-H., Heckathorn, D.-E., & Cordier, R. (2018). Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 50(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2297

- Tuckson, R. V., Edmunds, M., & Hodgkins, M. L. (2017). Telehealth. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(16), 1585–1592. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1503323

- Tufanaru, C., Munn, Z., Aromataris, E., Campbell, J., & Hopp, L. (2020). Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-04

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2021). Global education coalition. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition

- Van Lancker, W., & Parolin, Z. (2020). COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e243–e244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0

- World Bank Group. (2019). Urban population (% of total population). World Bank Open Data.

- Waller, M., & Stotler, C. (2018). Telemedicine: A primer. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 18, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-018-0808-4

- Wosik, J., Fudim, M., Cameron, B., Gellad, Z. F., Cho, A., Phinney, D., Curtis, S., Roman, M., Poon, E. G., & Ferranti, J. (2020). Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(6), 957–962. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa067

- Xiang, M., Zhang, Z., & Kuwahara, K. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents’ lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 63(4), 531–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013