ABSTRACT

Care-experienced children and young people are likely to experience early adversities that place them at increased risk of developing physical and mental health difficulties. Physical activity can help address the varied needs and interests of care-experienced children and young people and become a tool to manage mental health and well-being challenges. Growing research has explored the positive influence that physical activity can have on the lives of care-experienced children and young people, however, the literature has mainly focused on the barriers and enablers of engagement in physical activity. Though there is a growing amount of work in this area, there remains a need for further research that explores the influence that physical activity can have on the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people. A narrative review was conducted to explore the qualitative literature that has captured the influence of physical activity on care-experienced children and young people’s mental health and well-being, including what has been meaningful and why. Additionally, exploring qualitative research has helped to prioritise care experienced children and young people’s voices, which tend to be overshadowed by the views of researchers, carers, or social care professionals. The findings of the review report that physical activity can influence the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people by providing meaningful enjoyment, and the development of relational trust, skills, and emotional regulation. Further research is needed to provide a thorough representation of the changeable and long-term influence of physical activity on the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people, whilst prioritising their voices.

Introduction

“Care experienced” is a holistic term that refers to the journey that individuals can take when they move through the care system (Quarmby & Luguetti, Citation2021; Selwyn et al., Citation2016) and includes those who are currently in or have left care. The journey can range from being cared for at the family home through a compulsory supervision order, or away from home through either kinship care, foster care, residential care, secure units, prospective adopters, adoption, or other community placements, such as supported housing (CELCIS, Citation2022; Quarmby & Luguetti, Citation2021; Who Cares? Scotland, Citation2022).

It is likely that care-experienced children and young people (CECYP) must navigate complex adverse childhood experiences before entering the care system, that can include abuse, neglect, domestic violence, bereavement, family mental health challenges and/or substance use needs, combined with socio-economic disadvantage such as poverty, social isolation, and exclusion (Bakketeig et al., Citation2020; Bruce et al., Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, Green, et al., Citation2021; Selwyn et al., Citation2016; Whitley et al., Citation2022). When children experience early adversities, it can lead to agencies, such as social work, health, and education services, working with families, to ensure that children are cared for and protected either at or away from home. Early childhood adversities can lead to trauma and impact neurological, physiological, and psychological development, and place CECYP at increased risk of developing physical and mental health difficulties, and challenges with education and employment (Allik et al., Citation2022; Quarmby, Sandford, Green, et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2019). Allik et al. (Citation2022) emphasise that these challenges, although unique for CECYP, are avoidable with tailored support and services to better manage the needs of CECYP and their families, particularly before children enter the care system. In this narrative review, the focus is on the experiences of care experienced children and young people, and the term CECYP will be used. A distinction will be made when referring to research that has worked with care leaversFootnote1 that reflect on their experiences as youth.

Physical activity (PA) is an active process and inclusive term for light, moderate or vigorous movement of the muscular skeleton system using energy (Bruce et al., Citation2019; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; World Health Organisation, Citation2022), that can include sport (both competitive and recreational), exercise, fitness, play, curriculum physical education (PE), outdoor recreation, and leisure activities (Bruce et al., Citation2019; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016). PA such as team sports, walking, cycling, athletics, swimming, or dancing, can help to support the healthy growth and development of CECYP and improve health and educational outcomes (Bruce et al., Citation2019; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021). PA can also cater to the varied needs and interests of CECYP and become a tool to manage mental health and well-being challenges (Bruce et al., Citation2019; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, and Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, and Pickering, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021). To explore the influence of PA on mental health and well-being, the following definition of mental health and well-being is used; mental health and well-being are combined concepts that describe an individual’s personal assessment of how they think and feel about themselves, including the utilisation of capabilities and aspirations, development of relationships, coping with difficulties, and cultivating a sense of autonomy, worth, purpose, fulfilment, enjoyment, belonging, and balance (Alliance For Children In Care and Care Leavers, Citation2016; Carless & Douglas, Citation2010; McKenzie, Citation2022; Mental Health Foundation, Citation2022; What Works Centre for Wellbeing, Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2018).

There is a growing body of international research that has explored the positive influence that PA, leisure and free-time activities can have on the lives of CECYP, however, studies and reviews have mainly focused on the barriers and enablers to engagement in PA for CECYP (Bruce et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2021; Green et al., Citation2022; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, & Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019; Quarmby & Luguetti, Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021; Wilson & Barnett, Citation2020). Across the literature, the main enabler of engagement to PA for CECYP is trusting relationships developing with significant others whether that be a family member, carer, peer, or friend. Having trusting relationships as part of engaging with PA can then develop confidence, resilience, a positive sense of self, social skills and a sense of purpose and stability (Bruce et al., Citation2019; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, & Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021). The results of the literature are congruent with mixed-method research, in which CECYP voiced their own views on PA and related activities (Sandford et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). From questionnaire responses (n = 48) CECYP reported that PA provided a sense of fun, and helped to develop friendships and skills, but personal, and environmental barriers prevented engagement, that included limited self-efficacy, transport options, and access to money (Sandford et al., Citation2020).

If PA is to have a positive influence on the lives of CECYP, then PA needs to address the personal and environmental barriers, such as helping CECYP to overcome limited self-efficacy and providing access to funding that can cover the costs for transport, equipment, and fees (Bruce et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2021; Green et al., Citation2022; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, & Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019; Quarmby & Luguetti, Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021; Wilson & Barnett, Citation2020). Pereira (Citation2020) conducted a randomised controlled trial in Portugal with CECYP in residential care to quantitatively measure the mental health and well-being outcomes of the Wave-by-Wave intervention—which is a combined surfing and psychological programme. The intervention aimed to help CECYP overcome personal and environmental barriers, by ensuring that the activities could be accessed at the same time each week, with the same instructors. Additionally, participants were encouraged to recognise and express their experiences, thoughts, and feelings, during group sharing sessions to help develop communication skills and confidence (Pereira, Citation2020). Nevertheless, the CECYP’s responses indicated that the intervention did not influence their mental health and well-being, which contrasted with the staff quantitively reporting that the intervention led to CECYP experiencing fewer emotional and behavioural challenges and increases in pro-social behaviour (Pereira, Citation2020). An inference was not made between the contextual and structural factors of the programme and high retention levels (85%) for the intervention group. For example, the research did not capture the influence of the intervention’s safe and stable environment, with consistent staff that were empathetic, mental health trained, and trauma-informed and therefore sensitive to and responsive to the needs of the group (Pereira, Citation2020). By quantitatively focusing on the effectiveness of the surfing and psychological programme, the study used data collection tools that can be arduous, lengthy, repetitive, and insensitive (Demkowicz et al., Citation2020), and therefore missed the opportunity to capture the CECYP’s views, interpretations, and experiences to explore what worked for them, what did not and why.

This narrative review aims to capture CECYP’s views on the influence that PA can have on mental health and well-being, which is lacking within quantitative research (Pereira, Citation2020). Although comprehensive studies have been carried out on the barriers and enablers to PA for CECYP, there is limited research that has explored the unique, nuanced, and complex experiences of engagement in PA for CECYP. It would seem difficult to assume that PA will lead to defined mental health and well-being outcomes, and instead, a range of influences could arise that are specific to each person, their needs, interests, qualities, abilities, and life circumstances (Carless & Douglas, Citation2010). Therefore, conducting a narrative review can help to explore what works best for whom, under which circumstances, and what does not and why (Carless & Douglas, Citation2010; Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012). Furthermore, existing literature has advocated for more research to centre the voices of CECYP when hearing and learning about their experiences (Bruce et al., Citation2019; De Marco et al., Citation2015; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Pereira, Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, & Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019; Quarmby & Luguetti, Citation2021; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the aim of this narrative review is to explore qualitative literature to understand the personal influence of PA on CECYP’s mental health and well-being.

Methods

A systematic search of peer-reviewed research studies, published in English language only and dated between 1990 and March 2023 (end date of the search) was conducted using the following nine databases: CINAHL, ERIC, MEDLINE, ProQuest Social Sciences, Premium Collection, PsycINFO, ProQuest Psychology Database, Social Services Abstracts and Sports Medicine and Education Index. The following search terms were used:

“young people” OR “young person” OR youth* OR child* OR adolescen*

AND

sport OR “physical activity” OR activ* OR exercise OR fitness OR leisure OR “physical education” OR PA

AND

“care experienced” OR “looked-after” OR “kinship care” OR “residential care” OR “foster care” OR “secure care” OR “out-of-home care” OR “unaccompanied refugee minors” OR LACYP OR “in-care” OR “leaving-care” Footnote2

AND

AND “mental health” OR wellbeing OR “emotional health” OR “psychological health” OR “social health” OR “health benefits” OR “positive development” OR “social capital” OR confidence OR learning OR participation OR engagement.

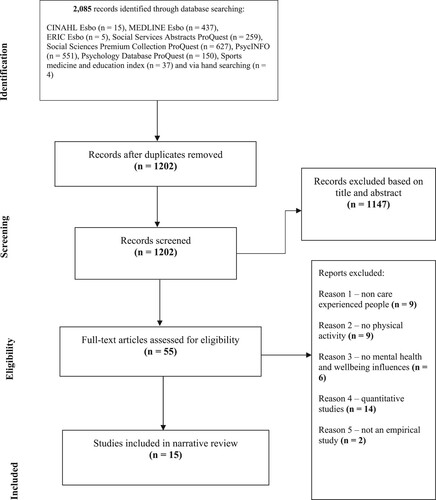

All the articles from each database were imported and saved into a referencing manager software (RefWorks) and duplicates were removed. Additional sources for searching were also used, such as reference lists, citations, and bibliographies of included studies. shows the database search results in four stages: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, presented as the PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., Citation2021).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (i) The population were care-experienced children and young people, who are currently or were previously care experienced, including care leavers, and the period in care was not restricted; (ii) In terms of the intervention, PA was the focus but not all studies had to be intervention studies, as we were interested in studies that broadly considered the relationship between PA and mental health and wellbeing; (iii) The studies needed to include the influence that PA had (or did not have) on the mental health and well-being of participants; (iv) Qualitative and mixed-method studies were included. For the mixed method studies if qualitative data could be separated and explored independently from quantitative data they were included. The exclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (i) participants were non-care experienced children and young people; (ii) no PA; (iii) mental health and wellbeing influences were not reported; (iv) quantitative studies; (v) not an empirical study.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by the first author, and a second author screened 10% of the titles and abstracts. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and changes were implemented where necessary. The first author then read the full paper for each article (n = 55) and documented all decisions on the Excel form, including reasons for excluding articles, and studies that met at least one of the exclusion criteria were rejected (Tod, Citation2019). The research team appraised the quality of the selected papers (n = 15) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [CASP] Qualitative Checklist (Citation2018). The ten questions that are part of the checklist helped to critically analyse the relevance and value of the methodology and findings from the qualitative studies (Long et al., Citation2020). The CASP Qualitative Checklist does not involve numerically scoring the studies, yet Long et al. (Citation2020) have advised organising the studies into three-four categories—high, medium, medium-low, or low quality. Critical discussions between the research team fed into the quality appraisal process and the final presentation of the collated data can be seen in .

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Results

The studies (n = 15) took place worldwide, in six countries, that included Australia (n = 2), England (n = 6), Ireland (n = 4), Netherlands (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), U.S.A. (n = 1). The participants for the studies ranged from care-experienced children, young people, and adults (who have spent time in care), and the carers or professionals that work with them. Studies (n = 6) explored PA experiences within the context of an intervention, including Wilderness Therapy, a Healthy Eating, Active Living (HEAL) programme, a 4-day Leadership and Respite Camp, an Arts and Athletics Camp, an Outdoor Recreational programme, and physical education and school sport (PESS). The remaining studies (n = 9) explored PA experiences with no intervention, by asking participants to share their experiences of unstructured PA (such as leisure time activities) or structured PA (such as recreational or competitive sport).

After the quality appraisal process, each study was treated individually to explore how the findings linked to the aim of the narrative review. Once the research team had an in-depth understanding of each study, an iterative and interpretative method was used, to explore perspectives, interactions, connections, and differences across the studies (Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012). The findings from all the studies were integrated using narrative techniques, such as drawing out similar and contrasting words, quotes, and sentences, that were then weaved together into a story of mental health and well-being experiences and led to an evolving discovery of new insight, meaning, and understanding (Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012). The studies reported a range of mental health and well-being influences that PA can provide for CECYP. Nevertheless, similar mental health and well-being influences emerged across the studies, which informed the development of four key areas: (1) meaningful enjoyment; (2) the development of relational trust; (3) personal and skill development; and (4) emotional regulation. The research team devised a narrative under each key area that explored contextual factors, and the personal influence of PA on CECYP’s mental health and well-being, including what was meaningful, and the complexities surrounding experience (Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012).

Meaningful enjoyment

Limited flexibility and freedom for CECYP to choose the type of PA, where it takes place, and with whom, can negatively influence engagement (McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019). A need for choice and freedom when engaging in PA does not solely apply to CECYP, as research has found that the general population of children are more likely to be active if they can choose the type of activity that matches their level of competence, interest and provides a sense of fun (Emm-Collison et al., Citation2022). Research in the context of Wilderness Therapy in Ireland and an Arts and Athletics Camp in the U.S.A. found that information sessions before a PA project and regular briefings with staff enabled CECYP to feel prepared and informed to make their own choices about engagement, especially because some were trying activities for the first time (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Schelbe et al., Citation2018).

The process of informing the CECYP of plans for the PA, the type of PA available, and giving them the choice about what to engage with and how (for example 1-to-1 or in a group) enhanced the enjoyment, fun and novelty of PA for CECYP (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Schelbe et al., Citation2018). Additionally, as part of outdoor recreational activities in Norway, Haaland and Tønnessen (Citation2022) found that the variety of activities available increased the CECYP's motivation because it differed from their daily routine options, that consisted of staying indoors, inactivity, and feeling bored. It seems that freedom and choice are integral starting points when using PA as a tool to engage CECYP meaningfully.

The development of relational trust

Developing relationships during outdoor recreational activities

The research shows that when CECYP have the choice and freedom over what and how to engage with PA it can sequentially lead to relationships developing with peers or adults. Internationally, outdoor recreational activities can help CECYP feel respected and cared for, which can lead to a trusting rapport developing with peers and adults (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Dare et al., Citation2020; Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022; Schelbe et al., Citation2018). CECYP who took part in Wilderness Therapy shared that when relationships developed it helped them work with others to navigate how much support was required during challenging PA (Conlon et al., Citation2018). With the right balance of support, CECYP were able to cope with the physical strain of activities, which then developed their mental and emotional strength, including increases in self-worth, motivation, and perspective (Conlon et al., Citation2018). Camp counsellors, in the Schelbe et al. (Citation2018) study, shared that during the Arts and Athletics Camp, companionship helped the CECYP overcome feelings of trepidation when trying new and challenging activities, which led to the development of interests and skills (such as perseverance) and increased self-efficacy and a sense of belonging. Dare et al. (Citation2020) worked with grandparents (also known as grandcarers within the context of kinship care), whose grandchildren attended a Leadership and Respite Camp in Australia. Grandcarers shared how their children’s social skills and networks from the friendships that developed during the camp, reduced their social isolation when returning home because they remained in contact with other CECYP.

Haaland and Tønnessen (Citation2022) explored how CECYP engaged in outdoor recreational activities, also known in Norway as “free-air-life.” The findings demonstrated that the social aspect of PA, in which the CECYP were encouraged to take part in PA together, helped them to build positive social connections, and develop feelings of acceptance and belonging (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022). The CECYP shared they could bond with one another through PA, and that differed from their life in residential care, where they usually spend time isolated from one another in their own rooms and on their phones. Additionally, CECYP described how they overcame barriers to engaging in skiing when residential staff provided opportunities for them to take part with their peers, which provided more enjoyment, inspiration, and motivation to ski regularly (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022).

Nevertheless, Haaland and Tønnessen (Citation2022) also described the limitations of free-air-life experiences and the potential negative influence on CECYP. For example, one participant expressed that they felt annoyed by the treatment of a staff member who would not let them use their snowboard during an activity (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022). Another participant explained that they preferred to spend time with staff than their peers because of previous experiences of rejection (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022). Similarly, residential staff in Ireland reported that when some CECYP were encouraged to take part in supervised PA they experienced discomfort when interacting with others, and a fear that they will be judged by peers as their care status could be revealed (McLean & Penco, Citation2020). Therefore, the social aspect of physical activities alone is not enough to create positive shared or social bonding experiences (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022). The mechanisms that are needed to create conditions for social development are ensuring that the staff are supportive and mindful of individual needs and interests, which can help to combat feelings of rejection and vulnerability (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022; McLean & Penco, Citation2020). There is a divergence in approach to PA opportunities in residential care between countries. In Norway, outdoor recreational activities are embedded as part of the CECYP’s residential care, whereas outdoor recreation for CECYP in the UK has been described as “piecemeal”, particularly in residential care (Sandford et al., Citation2021). Sandford et al. (Citation2021) found that from 120 CECYP in England, few mentioned accessing outdoor recreational activities (including being in nature) because of difficulties with access such as travel, and a lack of key staff members promoting the importance of varied PA opportunities.

Developing relationships during physical activity whilst in residential care

Quarmby (Citation2014) explored the views and experiences of CECYP in an English residential care home regarding their engagement in sports and PA. The CECYP explained that spending time with friends was the main reason for engaging in PA because they recognised that it can be the best way to develop and maintain friendships and spend less time alone. Furthermore, CECYP shared they could develop their social skills and networks through leisure-time physical activity with siblings and through youth clubs (Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019).

McLean and Penco (Citation2020) found that residential staff expressed the benefits of sharing a PA experience with CECYP in helping to develop trusting relationships, including nurturing CECYP’s sense of achievement and motivation. Residential staff further explained that within the formality of residential care home practices, it can be challenging to build relationships with CECYP, because of the pressured environment and limited quality time spent with each person (McLean & Penco, Citation2020). Research conducted by Cox et al. (Citation2018) on the influence of the Healthy Eating, Active Living (HEAL) programme in Australia enabled staff to use PA such as team sports, swimming, walking, biking, and the gym to spend time with CECYP away from the formal confines of the residential care settings. Off-site physical activities helped to develop rapport, which led to CECYP developing their confidence to discuss more sensitive topics that were creating emotional or behavioural challenges in their lives (Cox et al., Citation2018). The social skills that the CECYP developed from the relationship building also gave them the confidence to access further PA opportunities in the community and widened their social networks (Cox et al., Citation2018).

Care leavers experiences of developing relationships through physical activity

Across several studies, the findings show that when some CECYP enter the care system, their interest and motivation to engage in PA can reduce, due to multiple changes in both living arrangements and the adults (social workers and carers) supporting the CECYP (McLean & Penco, Citation2020; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021). This instability can continue when CECYP transition out of care, and it can be a time of disruption and unpredictability (Gilligan, Citation1999; Hollingworth, Citation2012; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021). However, the relationships that develop during engagement in PA can equip CECYP with the confidence to move forward, because it can provide a sense of regularity, consistency, and stability when becoming more independent (Gilligan, Citation1999; Hollingworth, Citation2012; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021).

Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al. (Citation2021) conducted a narrative inquiry that empowered care leavers to share their stories of PA, that included varied journeys capturing a range of barriers, engagement levels and support. The stories added depth and rich insight to previous findings by Quarmby, Sandford, and Pickering (Citation2019), by showcasing the unique and complex influence of PA on each of the participants' lives and from their own perspective. One participant described how their PE teacher, foster carer and coach helped to nurture their running talents and they were able to regularly engage with a running club and compete at a national level. Without encouragement, the participant described how difficult it would have been to improve their abilities because they needed support to travel for training and competitions. The participant further described how they could develop connections with people that they would not usually meet, due to running feeling like an activity for middle-class people. Connections became a new support network, that included positive role models, and a source of inspiration, that helped them to develop their willpower to succeed and recover from challenges (Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021). Similarly, Gilligan (Citation1999) and Gilligan (Citation2000) reported case study examples of the commitment and perseverance that significant adults provided to CECYP engaging in PA. Gilligan (Citation2000) found that a foster carer consistently championed a participant's love for dance, despite the challenges of sexism that the participant was dealing with from other people in the foster home. The foster carer's support contributed to the participant overcoming self-doubt and positively changed how the participant viewed themselves, their circumstances, and their future. Additionally, Gilligan (Citation1999) found that a sports coach helped a participant develop their personal, academic, and employment aspirations, including securing part-time work.

Studies from this review and the wider literature have advocated for regular PA opportunities for CECYP regardless of their living situation, and PA “champions” to nurture interest in PA, support engagement, and role model healthy behaviours (Bruce et al., Citation2019; Cox et al., Citation2018; Gilligan, Citation1999; Gilligan, Citation2000; Hollingworth, Citation2012; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Quarmby, Citation2014; Quarmby & Pickering, Citation2016; Quarmby, Sandford, & Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, & Pickering, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021).

Personal and skill development

Gilligan (Citation1999) identified the importance of CECYP engaging in both structured and unstructured PA opportunities outside of the care system, to reduce the stigma that can be felt when CECYP are referred to specialist services because of their care experience. Despite residential staff identifying that stigma and adversity (such as abuse, prior to entering the care system) can be a barrier to engaging in PA, they also reported that positive and diverse PA experiences can help CECYP to develop a sense of achievement, and progressively transform CECYP’s sense of self, such as their qualities and strengths, and what they have to offer, such as their skills and value in a group (McLean & Penco, Citation2020). In the narrative enquiry conducted by Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al. (Citation2021), one participant described an example of positive identity development, by explaining that regardless of their gender, they were still asked to play football by male peers, which helped them feel accepted, especially because there was pressure to dress and behave in a “girly” way. Football provided a more truthful depiction of who they were a “tomboy”, as they describe, and on the pitch, they could be like the rest of the players (Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al., Citation2021).

O'Donnell et al. (Citation2020) explored CECYP’s engagement in physical education and school sport (PESS) in England and found that PE teachers recognised the value and benefits of PESS for all students, including the development of communication and leadership skills and increases in motivation and confidence. One PE teacher highlighted how some CECYP outperformed other students in PESS, but it was dependent on the individual (O'Donnell et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, CECYP highlighted the importance of PA outside of school to support well-being, because they recognised that PESS can be challenging to engage with if they are experiencing multiple negative experiences within school (O'Donnell et al., Citation2020). Sandford et al. (Citation2021) explored the contextual factors that can influence engagement in PA for CECYP and found that most CECYP engaged in unstructured recreational activities outside of school, such as walking and cycling, roller-skating, and playing in parks. Unstructured recreational activities outside of school helped CECYP to use their time productively and provided a sense of purpose that positively contributed to their well-being and physical health. In terms of structured PA, Sandford et al. (Citation2021) found that some CECYP engaged in PA as part of a charitable organisation scheme (St John’s Ambulance, Scouts, or Duke of Edinburgh’s Award) that led to the development of skills needed for independence when transitioning out of care and became valuable experiences they could add to their CV.

Emotional regulation

International research shows that being in nature can help CECYP escape their everyday stressors and worries because they are given the physical, mental, and emotional space that comes with being in open, new, and fresh surroundings (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022). Participants from the Wilderness Therapy (Conlon et al., Citation2018) and Outdoor Recreational programme (Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022), describe how nature was “magical” when they explored the views of the surrounding mountains, the night sky, and the beauty that came with watching the unique images of the landscape. The outdoor environment helped to broaden the CECYP’s perspectives and being in nature combined with PA, helped the CECYP to regulate their emotions, as they started to become more confident in recognising and responding to feelings of distress (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022).

Research that worked with Eritrean Unaccompanied Refugee Minors (URMs) living in residential care in the Netherlands found that PA, such as walking, football, cycling, and swimming, helped participants to release daily stressors, such as financial challenges, and concerns about family (van Es et al., Citation2019). This research is congruent with findings from McLean and Penco's (Citation2020) study, in which residential staff shared the importance of PA in helping CECYP to release emotional tension that can build from experiencing ongoing anger, worry, and stress. Furthermore, PA was embedded in care plans due to the recognition that it can support CECYP with emotional balance and stress management (McLean & Penco, Citation2020). Nevertheless, the experience of stress can equally be a barrier to engagement, and some of the participants in the van Es et al. (Citation2019) study described that when they felt overwhelmed by stress, it negatively influenced motivation, and increased isolation, as they experienced challenges in being able to leave their room and engage in activities (van Es et al., Citation2019).

Another emotion that has been mentioned in the research is fear, and how overcoming feelings of trepidation before and during PA can lead to positive experiences (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Dare et al., Citation2020). Within the context of Wilderness Therapy, Conlon et al. (Citation2018) found that CECYP overcame fear, despite initial setbacks during rock climbing, gorge walking, and hiking, which helped to cultivate feelings of pride, resilience and increases in self-confidence. Grandparents in the Dare et al. (Citation2020) study reported that during the Leadership and Respite Camp, CECYP overcame fear in abseiling, surfing, and kayaking, and they noticed an increase in self-confidence and a sense of achievement when returning home, as the CECYP seemed less afraid to take part in further activities.

Quarmby, Sandford, Hooper, et al. (Citation2021) worked with a participant who described that football was a coping mechanism, that started in primary school and became a regular extra-curricular activity, before progressing into a competitive sport. The participant described how football was their only outlet to escape from life’s challenges, such as difficulties with siblings. They also described that rather than using physical violence to release anger, they were able to emotionally regulate by “pressing pause” on having to deal with serious issues, when engaging in football.

Discussion

This narrative review has captured the views and experiences of CECYP, carers, and professionals, and draws together existing findings that have explored the unique, and nuanced examples of the influence that PA can have on CECYP's mental health and well-being. Furthermore, a range of contexts have been explored, from outdoor recreational activities to unstructured and structured PA, to discover what has been meaningful and why, including the complexities surrounding engagement in PA. CECYP, and the carers and professionals that support them, have described how having the choice and freedom over what and how to engage in PA can bring enjoyment, novelty and fun. From this CECYP can develop relationships, skills, interests, and future aspirations and find ways to emotionally regulate and discover positive identities. These results are congruent with research that has explored the PA experiences of a wider population of children and young people. Emm-Collison et al. (Citation2022), reviewed qualitative literature across the UK to explore children’s perspectives and experiences of PA and reported similar findings on the importance of PA being child-led, and how engagement in PA can provide enjoyment, health, and social development if PA caters to varied interests, and utilises relationship development with others. Bruce et al. (Citation2019) conducted a narrative review of literature that explored PA engagement for the general population of young people, including some studies with CECYP, and found that PA can positively influence physical and mental health and well-being, by facilitating the development of relationships and utilising strengths.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine what type and dose of PA interventions are more effective in influencing the mental health of children and young people (Dale et al., Citation2019; Pascoe & Parker, Citation2019). Additionally, Jetten et al. (Citation2022) emphasise that PA alone does not reduce anxiety or depressive symptoms over time, and instead, the social aspect of PA can help young people manage mental health symptoms. The findings of this narrative review enhance our understanding that a range of mental health and well-being influences might occur when CECYP engage in PA, but the influence is specific and personal to each care-experienced child or young person and dependent on context (Bruce et al., Citation2019; Carless & Douglas, Citation2010; Sandford et al., Citation2021). For example, Haaland and Tønnessen (Citation2022) concurrently found that some CECYP developed their self-efficacy, self-worth, and positive thinking during outdoor recreational activities but other CECYP experienced feelings of rejection and vulnerability. Similarly, residential staff reported that PA helped CECYP develop trusting relationships, a sense of achievement and motivation, but other CECYP feared being judged when engaging in supervised PA (McLean & Penco, Citation2020). Furthermore, CECYP reported the benefits of unstructured PA in supporting the release of daily stressors and supporting well-being, but for others, emotional and behavioural challenges were barriers to engagement in unstructured PA and PESS (O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; van Es et al., Citation2019). Quarmby, Sandford, Green, et al. (Citation2021) have developed five evidence-informed principles to help physical educators and practitioners embed trauma-informed practice and respond effectively to the behaviour and complex needs of children and young people, particularly CECYP. These principles can provide holistic, safe, and consistent support to CECYP, and increase the likelihood of physical education positively supporting the mental health and well-being of CECYP (Quarmby, Sandford, Green, et al., Citation2021). Additionally, in the context of mental health care, Carney and Firth (Citation2021) have recommended that PA opportunities for children and young people are person-centred, flexible and cater to needs and motivations.

The main limitation of the review is the focus on short-term mental health and well-being influences that can arise when CECYP engage in PA. Therefore, further research is needed to provide a thorough representation of the complex, changeable and long-term mental health and well-being influence of PA on CECYP, whilst prioritising their voices (Bruce et al., Citation2019; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Pereira, Citation2020).

Conclusion and recommendations

Recent guidance from Australia for practitioners has been devised by experts in the PA and mental health field, that provides details on the contextual factors that are required for PA to have an influence on the mental health and well-being of the general population, which includes: (1) the type of PA; (2) when the PA takes place and reasons for engagement (3) where the PA takes place; (4) who supports or delivers the PA (5) how the PA is delivered (Vella et al., Citation2023). Interestingly, similar contextual factors are reflected in five of the 15 studies of this narrative review, including where and how the physical activities are delivered, what physical activities are available and who delivers the physical activities (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Sandford et al., Citation2021; Schelbe et al., Citation2018). It seems that for PA to have a positive influence on the mental health and well-being of CECYP, there needs to be an alignment of inclusive, safe, stable, accessible, and supportive contextual factors, including the choice of activities, the environment in which the activities take place, and the people supporting the activities (Conlon et al., Citation2018; Haaland & Tønnessen, Citation2022; O'Donnell et al., Citation2020; Sandford et al., Citation2021; Schelbe et al., Citation2018). When there is an alignment of contextual factors, CECYP can engage in PA in a worthwhile, and enjoyable way, and PA can facilitate the development of trusting relationships, skills, interests, and emotional balance. The practical implications of the findings can benefit practitioners in the health, sport, and exercise sector when working with CECYP because it demonstrates that implementing key contextual factors, combined with trauma-informed principles such as those articulated by Quarmby, Sandford, Green, et al. (Citation2021), within the design and delivery of PA projects can support the healthy development of CECYP (Bruce et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2021; Green et al., Citation2022; McLean & Penco, Citation2020; Quarmby, Sandford, & Elliot, Citation2019; Quarmby, Sandford, Green, et al., Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emily Whyte

Emily Whyte is a PhD Researcher at the School of Health and Life Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University. She has expertise in ethnographic, longitudinal, and participatory qualitative research and completed a Master of Research in 2019. Her current research interests include the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people and their engagement in physical activity.

Bryan McCann

Bryan McCann is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychology at Glasgow Caledonian University. His research interests include a range of sport and exercise psychology topics, in particular the social influences on motivation in sport and experience contexts, and the relationship between physical activity and mental health amongst adolescents. He gained his PhD in 2018, exploring the role of coaches, parents, and peers on athlete motivation during development.

Paul McCarthy

Paul McCarthy is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychology at Glasgow Caledonian University. His research spans social, cognitive, and biological psychology, and includes understanding how emotions influence motivation and attention in sports performance. Additionally, his research also examines challenge and threat motivation in sports performance from a social and biological perspective, and how teams could perform more effectively through personal disclosure and mutual sharing.

Sharon Jackson

Sharon Jackson is the Head of the Department of Social Work at Glasgow Caledonian University. She has research interests in the health, welfare and well-being of children and young people and the professional education and well-being of child protection professionals.

Notes

1 A care leaver is an adult who has spent time in care.

2 “Care-experienced” refers to anyone who is currently in or has been in the care system. The term “looked-after” places less onus on the experience of care, as it refers to children and young people being taken care of by their local authority/state/government. “LACYP” is an acronym that stands for “looked after children and young people.” There are different types of care, and “out-of-home care” is an umbrella term that refers to care outside of the family home. Kinship care refers to being cared for by a relative or close family friend. Residential care refers to living in a residential care home. Foster care refers to living with a foster carer. Secure carer refers to living in secure residential accommodation that restricts the freedom of children under 18. Unaccompanied refugee minors refer to children and young people under 18 without parents or guardians.

References

- Alliance For Children In Care And Care Leavers. (2016, July). Promoting looked after children’s emotional wellbeing and recovery from trauma through a child-centred outcomes framework. https://www.tactcare.org.uk/content/uploads/2017/05/08-16-Alliance-Promoting-Emotional-Wellbeing-Recovery-from-Trauma.pdf.

- Allik, M., Brown, D., Gedeon, E., Leyland, A. H., & Henderson, M. (2022). Children’s Health in Care in Scotland (CHiCS): Main findings from population-wide research. http://doi.org/10.3639/9gla.pubs.279347

- Bakketeig, E., Boddy, J., Gundersen, T., Østergaard, J., & Hanrahan, F. (2020). Deconstructing doing well; What can we learn from care experienced young people in England, Denmark and Norway? Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105333

- Bruce, L., Pizzirani, B., Green (nee Cox), R., Quarmby, T., O'Donnell, R., Strickland, D., & Skouteris, H. (2019). Physical activity engagement among young people living in the care system: A narrative review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 103, 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.05.034

- Carless, D., & Douglas, K. (2010). Sport and physical activity for mental health. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Carney, R., & Firth, J. (2021). Exercise interventions in child and adolescent mental health care: An overview of the evidence and recommendations for implementation. JCPP Advances, 1(4), https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12031

- CELCIS. (2022). Latest statistics about children and young people in and leaving care. https://www.celcis.org/our-work/about-looked-after-children/facts-and-figures.

- Conlon, C. M., Wilson, C. E., Gaffney, P., & Stoker, M. (2018). Wilderness therapy intervention with adolescents: Exploring the process of change. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(4), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1474118

- Cox, R., Skouteris, H., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., McCabe, M., Watson, B., Fredrickson, J., Jones, A. D., Omerogullari, S., Stanton, K., Bromfield, L., & Hardy, L. L. (2018). A qualitative exploration of coordinators’ and carers’ perceptions of the healthy eating, active living (HEAL) programme in residential care. Child Abuse Review (Chichester, England : 1992), 27(2), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2453

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2018). CASP (Qualitative Studies) Checklist. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Dale, L. P., Vanderloo, L., Moore, S., & Faulkner, G. (2019). Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: An umbrella systematic review. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.12.001

- Dare, J., Marquis, R., Wenden, E., Gopi, S., & Coall, D. A. (2020). The impact of a residential camp on grandchildren raised by grandparents: Grandparents’ perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 104535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104535

- De Marco, A. C., Zeisel, S., & Odom, S. L. (2015). An evaluation of a program to increase physical activity for young children in child care. Early Education and Development, 26(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2014.932237

- Demkowicz, O., Ashworth, E., Mansfield, R., Stapley, E., Miles, H., Hayes, D., Burrell, K., Moore, A., & Deighton, J. (2020). Children and young people’s experiences of completing mental health and wellbeing measures for research: Learning from two school-based pilot projects. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 35–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00341-7

- Emm-Collison, L., Cross, R., Garcia Gonzalez, M., Watson, D., Foster, C., & Jago, R. (2022). Children's voices in physical activity research: A qualitative review and synthesis of UK children's perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073993

- Gilligan, R. (1999). Enhancing the resilience of children and young people in public care by mentoring their talents and interests. Child & Family Social Work, 4(3), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2206.1999.00121.x

- Gilligan, R. (2000). Adversity, resilience and young people: The protective value of positive school and spare time experiences. Children & Society, 14(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2000.tb00149.x

- Green, R., Bruce, L., O’Donnell, R., Quarmby, T., Hatzikiriakidis, K., Strickland, D., & Skouteris, H. (2021). “We’re trying so hard for outcomes but at the same time we’re not doing enough”: Barriers to physical activity for Australian young people in residential out-of-home care. Child Care in Practice: Northern Ireland Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Child Care Practice, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2021.1895076

- Green, R., Hatzikiriakidis, K., Tate, R., Bruce, L., Smales, M., Crawford-Parker, A., Carmody, S., & Skouteris, H. (2022). Implementing a healthy lifestyle program in residential out-of-home care: What matters, what works and what translates? Health & Social Care in the Community, https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13773

- Haaland, J. J., & Tønnessen, M. (2022). Recreation in the outdoors—Exploring the friluftsliv experience of adolescents at residential care. Child & Youth Services, 43(3), 206–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2022.2044771

- Hollingworth, K. E. (2012). Participation in social, leisure and informal learning activities among care leavers in England: Positive outcomes for educational participation. Child & Family Social Work, 17(4), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00797.x

- Jetten, J., Haslam, C., Hippel, C. V., Bentley, S. V., Cruwys, T., Steffens, N. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2022). “Let’s get physical” — Or social: The role of physical activity versus social group memberships in predicting depression and anxiety over time. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.027

- Long, H. A., French, D. P., & Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559

- McKenzie, S. P. (2022). Reality psychology: A new perspective on wellbeing, mindfulness, resilience and connection. Springer International Publishing AG.

- McLean, L., & Penco, R. (2020). Physical activity: Exploring the barriers and facilitators for the engagement of young people in residential care in Ireland. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105471

- Mental Health Foundation. (2022). What is mental health? https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/your-mental-health/about-mental-health/what-mental-health.

- O'Donnell, C., Sandford, R., & Parker, A. (2020). Physical education, school sport and looked-after-children: Health, wellbeing and educational engagement. Sport, Education and Society, 25(6), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1628731

- Page, M. J., Mckenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffman, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021, 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pascoe, M. C., & Parker, A. G. (2019). Physical activity and exercise as a universal depression prevention in young people: A narrative review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(4), 733–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12737

- Pereira, A. I. (2020). Effectiveness of a combined surf and psychological preventive intervention with children and adolescents in residential childcare: A randomized controlled trial. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 7(2), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.07.2.3

- Quarmby, T. (2014). Sport and physical activity in the lives of looked-after children: A ‘hidden group’ in research, policy and practice. Sport, Education and Society, 19(7), 944–958. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.860894

- Quarmby, T., & Luguetti, C. (2021). Rethinking pedagogical practices with care-experienced young people: Lessons from a sport-based programme analysed through a Freirean lens. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1976742

- Quarmby, T., & Pickering, K. (2016). Physical activity and children in care: A scoping review of barriers, facilitators and policy for disadvantaged youth. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(7), 780–787. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0410

- Quarmby, T., Sandford, R., & Elliot, E. (2019). ‘I actually used to like PE, but not now’: understanding care-experienced young people’s (dis)engagement with physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 24(7), 714–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1456418

- Quarmby, T., Sandford, R., Green, R., Hooper, O., & Avery, J. (2021). Developing evidence-informed principles for trauma-aware pedagogies in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1891214

- Quarmby, T., Sandford, R., Hooper, O., & Duncombe, R. (2021). Narratives and marginalised voices: storying the sport and physical activity experiences of care-experienced young people. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(3), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1725099

- Quarmby, T., Sandford, R., & Pickering, K. (2019). Care-experienced youth and positive development: An exploratory study into the value and use of leisure-time activities. Leisure Studies, 38(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1535614

- Saini, M., & Shlonsky, A. (2012). Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

- Sandford, R., Quarmby, T., Hooper, O., & Duncombe, R. (2020). Right to be active project report (young people’s version). Loughborough University, Report. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/11638080.v1.

- Sandford, R., Quarmby, T., Hooper, O., & Duncombe, R. (2021). Navigating complex social landscapes: examining care experienced young people's engagements with sport and physical activity. Sport, Education and Society, 26(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1699523

- Schelbe, L., Deichen Hansen, M. E., France, V. L., Rony, M., & Twichell, K. E. (2018). Does camp make a difference?: Camp counselors’ perceptions of how camp impacted youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.022

- Selwyn, J., Wood, M., & Newman, T. (2016). Looked after children and young people in England: Developing measures of subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research, 10(2), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9375-1

- Tod, D. (2019). Conducting systematic reviews in sport, exercise, and physical activity. Springer International Publishing.

- van Es, C. M., Sleijpen, M., Mooren, T., te Brake, H., Ghebreab, W., & Boelen, P. A. (2019). Eritrean unaccompanied refugee minors in transition: A focused ethnography of challenges and needs. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 36(2), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2018.1548917

- Vella, S. A., Aidman, E., Teychenne, M., Smith, J. J., Swann, C., Rosenbaum, S., White, R. L., & Lubans, D. R. (2023). Optimising the effects of physical activity on mental health and wellbeing: A joint consensus statement from Sports Medicine Australia and the Australian Psychological Society. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 26(2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2023.01.001

- What Works Centre for Wellbeing. (2022). What is wellbeing? https://whatworkswellbeing.org/about-wellbeing/what-is-wellbeing/.

- Whitley, M. A., Donnelly, J. A., Cowan, D. T., & McLaughlin, S. (2022). Narratives of trauma and resilience from Street Soccer players. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1879919

- Who Cares? Scotland. (2022). Statistics – Care experienced people are never just a number to us. https://www.whocaresscotland.org/who-we-are/media-centre/statistics/.

- Wilson, B., & Barnett, L. M. (2020). Physical activity interventions to improve the health of children and adolescents in out of home care – A systematic review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104765

- World Health Organization. (2018, March 30). Mental health: strengthening our response. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

- World Health Organization. (2022, October 5). Physical activity. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity.

- Wright, H., Wellsted, D., Gratton, J., Besser, S. J., & Midgley, N. (2019). Use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to identify treatment needs in looked-after children referred to CAMHS. Developmental Child Welfare, 1(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516103218817555