ABSTRACT

Despite growing interest in Indigenous health, the lack of end-of-life (EOL) research about the Sámi people led us to explore experience-based knowledge about EoL issues among the Sámi. We aim here to describe Sámi death systems and the extent to which Kastenbaum’s conceptualisation of death systems is appropriate to Sámi culture. Transcribed conversational interviews with 15 individuals, chosen for their varied experiences with EoL issues among Sámi, were first inductively analysed. Kastenbaum’s model of death systems, with functions along a time trajectory from prevention to social consolidation after death, and the components of people, times, places, and symbols/objects, was applied thereafter in an effort to understand the data. The model provides a framework for understanding aspects of the death system that were Sámi-specific, Sámi-relevant as well as what has changed over time. Whereas Kastenbaum differentiated among the components of the death system, our analysis indicated these were often so interrelated as to be nearly inseparable among the Sámi. Seasonal changes and relationships to nature instead of calendar time dominated death systems, linking people, places and times. The extended family’s role in enculturation across generations and EoL support was salient. Numerous markers of Sámi culture, both death-specific and those recruited into the death system, strengthened community identity in the EoL.

Introduction

There is increasing international interest in Indigenous people’s health, and to some extent, end-of-life (EoL) care needs. However, there is relatively little empirical data about the general health status of the Sámi, who are Indigenous peoples in Northern Fennoscandia, an area now called Sápmi. There is even less data about issues relating to death, dying and bereavement, with Indigenous EoL research stemming mostly from Australia, New Zealand and Canada (Gott et al., Citation2017; Kelley, Citation2010). Hassler and Sjölander (Citation2005) reviewed health-related research on Indigenous peoples over a 30-year period, pointing to a growing interest due to lifestyle-related ill health resulting from encounters with mainstream cultures. While they point to discrepancies between the health of the majority and Indigenous populations, respectively, they note that these appear not as pronounced in relation to the Sámi, with the exception of an increased suicide rate, a phenomenon notably difficult to research (Young, Revich, & Soininen, Citation2015). One possible explanation for the lack of research on death-related issues among the Sámi may be understood in relation to Dagsvold’s (Citation2006) description of it as a ‘silent culture’, relying on indirect language or silence in communication about life-threatening disease. Daerga, Sjolander, Jacobsson, and Edin-Liljegren (Citation2012) point to another hinderance in the often problematic encounters between the Swedish health and social care systems and the Sámi, as the Sámi report a need for them to explain, and often defend their lifestyle to the authorities.

In this article, we aim to contribute to filling a notable knowledge gap by exploring experience-based knowledge related to dying, death and bereavement among the Indigenous Sámi people. This empirical data are presented in relation to Kastenbaum’s concept of death systems (Kastenbaum & Moreman, Citation2018). We investigate how acknowledged symbols of specific Sámi cultural identity are related to these death systems and the extent to which Kastenbaum’s conceptualisation is appropriate to Sámi culture.

Background

End-of-life care in Northern Sweden

While Sweden is highly ranked internationally for specialised palliative care (PC), (The Economist, Citation2015) these achievements have not benefited large portions of the population. Depending on diagnosis, region, and place for EoL care (The Swedish Register of Palliative Care, Citation2017), specialised PC reaches only 3–22% of those dying in Sweden. About 38% of the deaths occur in residential care homes, about equal to the proportion dying in acute care hospitals (Håkanson, Öhlén, Morin, & Cohen, Citation2015).

The Northern health care region, in which most indigenous Swedish Sámi live, comprises 50% of Sweden’s area but less than 10% of its population. The region has an exceptionally elderly population, particularly in rural and remote areas (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2018). Supporting EoL care in the region is thus important, particularly in a manner relevant for the Sámi population, more than 70% of whom live in Northern remote areas (Hassler, Johansson, Sjolander, Gronberg, & Damber, Citation2005).

The Sámi and dying, death and bereavement

The number of Sámi in Sweden today is between 17,000 to 20,000 (Wängberg, Citation1990); as ethnic background is not explicitly documented, specific statistics are unavailable. The Sámi are one of five official minority cultures (Gunér, Citation2011), which means that they have a legal right to their own languages, of which the three largest are Southern, Lule and Northern Sámi. Another legal right relates to Sámi traditions of reindeer husbandry, still carried out by 4663 people (Sametinget, Citation2017), organised in 51 ‘sijte’ (Swedish: samebyar), i.e. Sámi economic organisational units and communities which have a set open area in which reindeer may be herded. These can be extensive geographic areas, ranging from the mountains to the coast, within which it is necessary to move with the reindeer according to season (Oskal, Citation2000). This ‘mobile pastoralism’ (Ingold, Citation1980) does not always mesh with the organisation of Swedish society in general and has been found to be a point of conflict (FAO, Citation2016). Reindeer husbandry, along with language, crafts, traditional Sámi song (yoik) and traditional Sámi occupations, e.g. fishing and hunting, are recognised symbols of this culture, which is grounded in a world-view based on relationships between nature and people (Åhrén, Citation2008; Stoor, Citation2007; Tervo & Nikkonen, Citation2010). The Sami community system is organised around the extended family and other social networks. This is in part due to collaborative relationships in reindeer husbandry (Nymo, Citation2011) but also works as a safety system for survival in the harsh northern climate (Myrvoll, Citation2011).

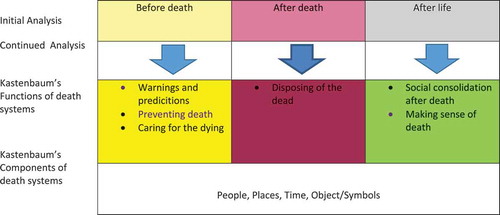

Kastenbaum’s conceptualisation of a death system

Kastenbaum and Moreman (Citation2018) argue that most, if not all societies, have what Kastenbaum calls ‘death systems’ – i.e. socially accepted means of supporting the dying and bereaved, and of taking care of the dead. Weigleitner, Heimerl and Kellehear (Citation2015) have argued that these primarily non-institutionalised resources have been eroded by their dis/replacement by professional services in many societies today. Wegleitner, Heimerl, and Kellehear (Citation2015) and Kastenbaum and Moreman (Citation2018) argue that we need to focus on how our encounters with death are systematically related to the societies in which they occur and thus to basic ways of life. Consideration of death systems draws our attention to how cultural and societal norms, expectations, traditions and symbols affect individual experiences (Kastenbaum & Moreman, Citation2018). Kastenbaum categorises these systems according to both functions and the components which contribute to fulfiling these functions, as shown in . Functions, the purposes a death system serves, are described along a trajectory from Warnings and Predictions, to Preventing Death, Caring for the Dying, Disposing of the Dead, Social Consolidation after Death, Making Sense of Death. Kastenbaum also considers Socially sanctioned Killing, to be part of all cultures. The components Kastenbaum explicitly described as working to fulfil the functions of a death system are People, Places, Times, Objects, as well as Symbols and Images, which might also be considered to include rituals. While most of these components are self-explanatory, objects can consist of those that are both death-system specific as well as everyday objects that are ‘recruited into the death system … ’, so that their ‘meanings are transformed even though the objects themselves remain the same’, as will be seen below (Kastenbaum & Moreman, Citation2018, p. 80).

Methods

The research team in this qualitative interview study was multi-cultural, consisting of two Sámi researchers, a woman who is both a community registered nurse (RN) and doctoral student (initials LK), and a man, with a PhD in Sámi studies (KS), both from the Northern Region of Sweden. They were complemented by two researchers without experiential knowledge of Sámi culture, a Swedish man, who was a PhD RN from the Northern Region (OL), and a woman, also a PhD RN with a minority background born outside Sweden and residing in an urban area in southern Sweden (CT). Due to geographic distance among team members, even those in the Northern region, we met regularly for several days at a time when planning, carrying out, analysing and writing the manuscript, in addition to regular, virtual contact.

Recruitment

While the specific definition of Indigenous Peoples is contested, there is general agreement about a number of shared characteristics. According to the United Nations (United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Citation2018), these include

Self- identification as Indigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community as their member; historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies; strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources; distinct social, economic or political systems; distinct language, culture and beliefs; form non-dominant groups of society; resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.

Working from this criteria, the research group purposely determined potential informants to contact, with different backgrounds and types of knowledge about death and dying among Sámi, with perspectives from both those who define themselves as Sámi according to the above definition and those who are not Sámi. Given our research aim, we sought to interview a variety of people – both Sámi and non-Sámi – with a range of experiential knowledge about EoL issues among the Sámi, aware that this might be a difficult subject for many people to discuss. We included people working in different roles in both the Churches of Sweden and Norway, undertakers, people working in elder care and others, of varied ages and backgrounds. As the Sámi community in Sweden is relatively small, many potential informants were known to members of the research group; suggestions for new informants were received and followed up on throughout the interviewing process.

Data collection

Prior to ethical review, we composed an information letter and informed consent form for participants. These were professionally translated from Swedish to Norwegian and to the major Sámi languages. After ethical review (2016/02-31, 2016/252-32), we began to recruit participants, using purposeful sampling to find informants, later applying snowball sampling when others were referred to us as new potential informants (Heckathorn, Citation2011; Patton, Citation2002). We initially contacted potential informants by telephone due to the sensitive subject matter. We then sent an email or postal information letter with the informed consent form to those interested in participating. We offered to meet participants face-to-face at a place of their choice, or interview by telephone, with the written information also clarifying that we were interested in their experiences and reflections about issues related to the EoL among Sámi. Informants were not all contacted at the same time, but as we were interested in heterogeneity in perspectives, we contacted potential informants with complementary perspectives gradually, making recruitment choices as data collection progressed.

Twenty-five potential informants were contacted. Four were unwilling to participate – one (non-Sámi) undertaker explaining that there was nothing special about Sámi funerals, two (non-Sámi) due to limited time, and one (non-Sámi) who did not return the call as agreed upon, despite multiple efforts at contact. Four potential informants were willing to participate if needed (two Sámi, two non-Sámi), but were not interviewed, and 17 interviews were actually carried out. A telephone interview (Sámi), which was interrupted after 6 min due to the participant’s time constraints, was deemed uninformative and therefore excluded from the analysis. An additional person (Sámi) was interviewed but wished to be excluded due to potential confidentiality issues. Another participant (Sámi) expressed interest in receiving the interview transcript, which occurred in a second meeting with the interviewer, and agreed to continued participation. The database for analysis thus consisted of a total of 15 interviews, two-thirds with Sámi informants. Eleven analysed interviews were conducted by the first author, and two each by the second and last authors. Six interviews took place in the participant’s home, one in a researcher’s home, three at the participant’s workplace and five in a public café or restaurant.

The interviews were all conducted in Swedish or Norwegian, with some Sámi words and phrases. They lasted between 50 and 150 minutes, and were initiated by an open question, asking about special desires, priorities, needs and ways of expression related to end-of-life and bereavement in Sámi culture, often requesting a description of a particular situation as a point of departure. While no predetermined interview guide was consistently used, follow-up questions were asked as needed in these conversational interviews. Fourteen interviews were audio-taped; one person did not wish the interview to be recorded – notes were instead taken during the interview and elaborated upon directly afterwards by the interviewer.

Limited demographic data about informants are presented, in an effort to maintain confidentiality in this relatively small community. Eight informants were women, six of whom were Sámi, and four of the seven men interviewed were Sámi. Their ages ranged from approximately 25–83 years old, with seven of those interviewed over the age of 60. Eleven of the 15 interviewed had some affiliation with a church, which was a primary source of their contact with death-related issues, and three lived in families engaged in reindeer husbandry.

Data analysis

Data analysis was inspired by Interpretive Description (Thorne, Citation2016) and initiated along with the interview process. The first author began with an initial naïve reading of the verbatim transcripts, after which the audio recordings were listened to and the transcripts corrected. Salient features noted at this point related to Sámi societal structures, including interactions with the majority society and with health/social services; descriptions of a sense of community among Sámi; and descriptions of a Sámi identity and how it is maintained on individual, family and community levels.

During this first familiarisation process, the research team met and listened to the first few interviews, to discuss content, interview technique, and continued recruitment strategies. After 13 interviews had been conducted, the team met again for 3 days, during which time we each read two to three different interviews and jointly coded one together to discuss alternative coding schemes for use in NVivo, software supporting qualitative data analysis. We decided to conduct two additional interviews with participants familiar with care of the dying, to complement the focus on funerals and after-death care which we noted in the already-collected data.

Initial coding was close to the text, using codes like language; family; reindeer, nature and landscape; food; funerals; etc. We then developed a matrix, with codes entered on a timeline related to care of the dying before death; from death through the funeral; and after the funeral. Authors LK and OL continued to develop the coding scheme and categorised these into meaningful groups. Codes, categories and how they should be interpreted and presented were repeatedly discussed in meetings of the full research team.

Kastenbaum’s Theory of Death Systems (Kastenbaum & Moreman, Citation2018) was introduced relatively late in the analysis process. Given the familiarity that the Sámi members of the research team had with the culture, we were challenged to find ways of deepening our understanding of the data, beyond that which was already known, and to find means to structure and present our findings. Kastenbaum’s theory did not guide analysis itself but was applied to provide a cohesive framework to facilitate understanding of the results, such that we recoded all data according to a matrix with both Kastenbaum’s functions (based on earlier analysis of timeline) and components. During interviews and in the analysis process, efforts were made to understand what was Sámi-specific, Sámi-relevant, what was changing in the culture over time and could influence the future, as well as exploring interrelationships between different aspects of what we here call death systems.

Findings

Findings are presented along a trajectory in relation to Kastenbaum’s functions of a death system, with relevant components described for each function. We also note points of tension in our material in relation to Kastenbaum’s model.

Before death

Functions: to give warnings and predictions; To prevent death

While this was not a topic intended to be addressed in the interviews, it was touched upon by several informants in stories concerning general advice but even indicating important values in the Sámi culture.

People

In these data, the importance of the traditional Sámi extended family as a means for communicating knowledge across generations is clear. In this context, the substance of traditional knowledge concerned warnings for tangible and intangible dangers, as Maria, an older Sámi minister, described it:

Warning, you know, warning for risks and beasties […] both risks in society and risks in your own life … storytelling became a way to convey further that which you want to communicate to generations to come.

However, it was not the substance of the warnings that was in focus in most interviews, but rather a fear that this type of enculturation was at risk of being lost. Another Sámi woman, Sara, with a health care background, pointed out: ‘There is so much that has changed, like this with the elderly, they end up in institutions and elder care and so on – so these family ties are broken.’ This view was not exclusive for the older generation, even younger Sámi informants expressed concern, as Laila said,

The Sámi way with an extended family – hanging out together across the generations, it has been incredibly important for us and it still is, but – the whole machinery of mainstream society, you get segregated – there’s getting to be a great loss of knowledge about how you choose perspective on things, I really believe that.

Places

The substance of warnings could relate to specific places and respectful behaviour, e.g. Maria warned about the negative consequences of treading in ‘a careless manner’ on a place where someone had lived or was buried. We interpret the gist of such comments as not only indicating a need to show respect but also an implicit warning about diffuse risks in neglecting to do so.

Objects/symbols

A number of informants spoke of signs of impending death, with birds named on several occasions. Other descriptions contained examples of how necessary it is to show respect not only for the dead, but for all living beings. Maria again warned,

… you must be very careful with the animals in the mountains and forest. You need to tread in such places with a “holy foot”, or however it should be expressed … But this is what used to be in the Sámi culture, and still is …

An important point is the link between the past and the present, which many informants emphasised repeatedly.

Function: caring for the dying

An overarching theme in this function is familiarity, with markers of Sámi identity and kinship important as EoL is approached.

People

The central role of the extended family in care of the elderly and the dying, was pointed out by most informants. As Susanne said about her Sámi family: ‘ … in my family, you take care of your own. You care for them in many ways … you help at funerals and you help to care for your elders’. Susanne also told a longer story about caring for a family member, describing the reaction from formal health care providers when they came to their home: ‘That’s what one of them said [non-Sámi hospice staff member]. That this was something special they hadn’t experienced before. That there were so many of us, that it was so natural’. Susanne continued her story, saying that her family member seemed to wait until the season’s reindeer husbandry had been completed before dying, so that other family members could come to the bedside, say farewell, and each receive advice from the dying person.

Places

There were a range of different aspects of place that were raised in relation to caring for the dying. These included places of general cultural importance for Sámi as well as those of individual importance. There was discussion about what was desirable in a place for dying, as well as problems arising with regard to place.

A common denominator was that the environment should be familiar to the dying person. An older Sámi man, Peter, summarised what many described, speaking of his home at a lake in the mountains in a remote area:

For my own part, – to be able to be in a place like this, that would be very, very, desirable … I believe that, having yours and those who matter to you close by … it is the old- old Sámi … [pauses]. Your life was family-based and the relation to the land was very, very strong and continuous … and it’s that, to be able to experience that again, that’s what I think [is important].

Peter speaks both of his individual wishes, linking them to a way of life with both geographical and cultural roots. He expressed a desire for the outdoors positively, whereas others spoke of fears of being shut in as Erik, a Sámi elder and minister, said,

Ending up in a nursing home isn’t nice for anyone, but for a Sámi it is like being a bird with broken wings. [You] have the whole landscape within you, with reindeers’ migrating from the mountains to the coast and then back. A small sterile room must be filled with anxiety …

He continued by suggesting how staff might support older Sámi:

Someone from the staff might take an old person … to see the mountains again and walk on old paths that the elder has walked on before, even if only for a short while. To have a sense of recognition, and to remember, to bring old memories to life.

It should be recognised that informants referred to nature as an intrinsic part of daily life, what Maria called ‘nature as a living room’. The interviewer least familiar with Sámi culture asked someone describing care for a dying family member, ‘I wonder, where do you think “home” is in this context?’ Susanne responded tellingly: ‘Everywhere, I think it is probably everywhere’.

Times

In these data, time points appear to be generally related to nature and seasonal changes, rather than to specific calendar dates, as in Kastenbaum’s U.S.-based examples (Kastenbaum & Moreman, Citation2018). Many examples were related to seasonal changes in reindeer husbandry. Inga, a Sámi woman working with the elderly explained how important this was in providing care:

… there is a kind of knowledge and … a cultural understanding, what it is that happens and how you can deal with it … We had an old woman who kind of started to pack every fall. She started to look for things and pack her stuff, because it was time to move’ [to migrate with the reindeer].

Despite our efforts to code data into separate components, we were not always able to distinguish between place and times in these data, since they are so closely related in the mobile pastoralism that permeates reindeer husbandry and is so closely tied to traditional Sámi culture.

Objects/symbols

While Kastenbaum distinguishes between the components he calls Objects versus Symbols/Images, based on our analysis, we have chosen to combine them here. Our justification for this is that both tangible objects and intangible phenomena described in interviews as relevant in Sámi death systems, have symbolic value in that they are said to be bearers of Sámi identity. Important symbols of Sámi identity described in these data include language, and yoik as another communication form, traditional food, animals, nature, traditional handicrafts, as well as decorations in bright yellow, green, red and blue – traditional Sámi colours now found on Sámi flags.

The interviewees pointed to the importance, not only of familiar places but also of familiar surroundings in elder care and when dying – this is something which is well established, and not Sámi-specific as emphasised by Peter, Sámi himself:

In general … I think it is important for people who more and more realize that my time is coming to an end, so it’s more and more important to hold onto things that they have been close to throughout their lives … and it is the same with food and smells and sounds and all of that.

However, what makes an environment familiar tended to be Sámi-specific, as Sara, experienced in care of elderly, said,

I haven’t encountered so many [elderly and dying] men, but you know, binoculars. Letting them have their binoculars. We’ve seen it [to have a calming effect]. And a knife belt … a knife belt with a wooden knife in it [instead of a real knife] … something that’s been missing that they’ve worn their whole life.

Reindeers are perhaps most Sámi-specific with a strong symbolic value. Their importance is referred to repeatedly in interviews with both Sámi and non-Sámi as part of a lifestyle and in terms of the importance of artefacts made of reindeer products. The importance of traditional food, e.g. from reindeer, in caring for frail and dying elderly people was noted. Inga said:

He basically ate nothing, just potatoes and a piece of meat every now and then, but when we made dumplings [“blodpalt” in Swedish] and sausage from reindeer blood, he piled it up on his plate and carried it into his room, so he could save some for the next day.

Using a Sámi language in caring for the dying was mentioned in most interviews as important – not so much the words used particularly in referring to death and dying, but communication in a familiar language. This was pointed out by both Sámi and non-Sámi, in reference to those elderly with Sámi as their first language. They were said to respond to things in Sámi that they appeared not to hear in Swedish; language was also important for those who didn’t speak Sámi but recognised it as familiar. It should be noted that Sámi languages are endangered, with fewer and fewer people who speak them fluently in younger generations, but, as the young Sámi woman, Laila, explained,

Even if everyone hasn’t mastered [a Sámi language], or speaks it … they’ve heard and understood some words and it is still the language of their heart. And if there are staff who know it … it touches their [the elders’] hearts.

This was said to be particularly important as the EoL approached, and was described by Maria, with her background as minister, as a form of spiritual care.

Sometimes in the last moments of life, if you can do it in the person’s own language – the last rites-passing in that language. Because that’s also a form of care, spiritual care, spiritual needs close to death. Maybe you don’t always think of it yourself, I noticed, if there aren’t relatives.

As minority languages, there is a theoretical right to receive care in one’s native Sámi language in designated areas. But this is a politically sensitive issue, dependent on the initiatives of the caregivers or family. Susanne discussed the need to be proactive:

And dare to demand it [communication in Sámi] in health care. Dare to see that these needs exist, because … imagine if you, as a Swede, – if your relatives had to be [communicating] in a totally different language, compared to their own language, when they have to express what is needed.

Although few addressed it directly, the symbols of Sámi identity could meet the same prejudices in care of the elderly and dying as in the rest of society, as pointed out here by Susanne:

Yeah, it is a little bit like they [other residents in elder care] won’t sit at the same table at mealtimes … they maybe say something [derogatory] about reindeer husbandry or Sámi or something … or that staff have difficulty dealing with Sámi or … those from another background, since they maybe don’t know about the culture.

After death

Function: disposing of the dead

This material, in part due to the choice of interviewees, is rich in descriptions of funerals and their rituals. All descriptions are of Lutheran funerals, but with tension between a conservative, strict Swedish/Norwegian liturgy, which may or may not have Sámi elements, and a more individually adapted interpretation of Lutheran funeral rituals. A stricter position is explained by Laila as ‘you follow the church’s protocol … but then you can add a little Sámi touch’ whereas Peter exemplifies a desire for a more individualised approach, saying

But a Sámi funeral, then I want to choose and you decide yourself your place … with the family in agreement. I think that … the atmosphere around a funeral becomes something different, because then you are in your arena and your area, in your setting.

People

The funeral played a strong social function as a means of gathering together not only extended family, but also a broader social network. John, a Sámi working in the church, compared a Sámi funeral to ‘a formal state funeral’, with people travelling long distances to participate. Monica, a non-Sámi priest, explained ‘ … it was tremendously important, that the family, relatives, neighbours, workmates, really the whole “sameby” [reindeer herding community], was there … it was a point of honour.’ Erik explained this by referring to the position of the Sámi people in society in general:

And it’s clear, [the Sámi are] a vulnerable group … you need each other in a different kind of way … the sense of community, a kinship and the pressure from outside can contribute to keeping the group together. There’s a lot of Sámi hatred out there.

Places

Traditionally most Sámi have been buried, rather than cremated. Depending on the season and location of the reindeer herd, funerals may be held close to the site for winter grazing, whereas the wish for a burial place may be in the mountains which are difficult to access in winter months. Again, the central role of kinship, and also of the landscape, is salient. Monica explained,

It is very important where you are buried, it should be in the earth of your forefathers, or the earth from which you come. These ties to the land and to the earth and family and so on, are very strong.

The importance of connection to the land can lead to a choice between being buried in a particular place or being buried with kin, as Laila noted,

But if I can choose, I think I would like to be buried in the mountains and not among my “maadteraahka” [female ancestors] and “maadteraajja” [male ancestors], who are still in the cemetery …

Times

Traditional Sámi funerals are often full-day events, sometimes beginning with a viewing, days before, as John said, ‘it has to be allowed to take time – we have time for life later.’ He continued,

I know once I was there [at a viewing] a whole day … you sang a psalm and you had a little service and chatted a bit, and then we went out. And there was someone who … wanted to be there by themselves for a while, … and then we needed dinner and – coffee and it was – it took all day.

Anna, a Sámi, noted that it is important to participate in the graveside service, not just the church service:

Mmm, we meet so very rarely, and everyone goes together to the burial site … I was going to say that if people aren’t able to walk, you pretty much wheel them there.

Objects/symbols

As in relation to caring for the dying, the same types of familiar objects and symbols of Sámi identity are often evident in funeral descriptions, e.g. traditional and warm food – often from reindeer – traditional handicrafts, and Sámi colours. There are descriptions of recruited objects that are both Sámi-specific, e.g. wooden hiking sticks, bells worn by reindeer, and drinking mugs made of wood, as well as those that are Sámi-relevant but not specific, as described here by Maria who put woollen socks on the deceased person: ‘I know she isn’t cold anymore … but I do it symbolically, because she used to want them.’

Anna noted that wearing traditional Sámi clothing to funerals was an important sign of respect: ‘You always wear ceremonial clothing, pretty much everyone who owns a “kolt” [traditional clothing] has it on, because this is an occasion for commemoration, leaving the dead.’ There are examples of funeral-specific objects, e.g. special Sámi funeral mittens and shawls worn by those in attendance. While there was consensus among interviewees about most issues raised in the research, whether or not familiar objects should be in the coffin was an exception. Interview data contains both descriptions of placing artefacts from reindeer in the coffin as something familiar, and descriptions where that practice is described as prohibited. The tension between Lutheran liturgy and Sámi traditions was also noted in some interviews, e.g. Anna described doing something ‘pagan’ when she and a friend ‘snuck’ a reindeer antler onto a gravesite.

As noted above, burials have been more common than cremation, although some informants said this was changing. Laila, cited above, who wanted her ashes to be spread in the mountains rather than buried in a cemetery with her forefathers, mentioned this as one reason for her wish. Another reason, which was implied but not explicitly mentioned in these data, may be the history of race biology and fear of Sámi remains being exploited in scientific research. However, there was also resistance to cremation, as Sámi were said to traditionally not burn either human or animal bones. Sara pointed this out:

And you, one hears that, I know that someone has been cremated. It is sort of, well we don’t want to burn bones. A Sámi doesn’t – one elder reacted when he heard that [someone] was going to be cremated. I remember this, when … he [said] “burn, no but, no but we don’t do that, do we?

Another point of tension related to language and yoik, as forms of expression at Sámi funerals. Several people described having a service in a Sámi language as something that should be, but often was not, self-evidently important. Yoik, traditional a cappella Sámi song, was spoken of as a means for remembering, a way of continuing to keep the individual ‘alive’, and the personification of grief. Yoik is both a noun and a verb, and one yoiks not to someone or something, but one yoiks them, one becomes what one yoiks, so it is a form of personification at funerals. Yoiking at funerals has been a source of controversy historically, between those who follow a strict interpretation of Lutheran liturgy who viewed it as sinful, and more liberal interpretations of yoik as a symbol of Sámi identity. Maria summarises the situation:

Yes, yes it is different [nowadays], I’ve understood at some funerals there is yoiking these days, but further back it wasn’t done at all. And I think that it might still be like that for older [Sámi] people, they might have a scepticism to yoiking in general.

It appears that one means of circumnavigating this conflict was through crying. The distinction between crying and yoiking, Kurt, a non-Sámi minister, said was marginal:

So it [yoik] returns when crying comes. And I noticed that even when the day of the funeral arrived and you come to the gravesite, so – crying by the gravesite … it was as close to the yoik as you could come.

As yoiking is both so personal and so culturally significant, several interviewees pointed out, as Peter does here, that a prerequisite for yoiking was a sense of cultural security: ‘you must be very, yes feel very secure and know that, that it is your setting, you do what you feel is natural for you … ’ Another form of expression described at funerals was speaking directly to the deceased person as if they were still alive. Erik makes clear that for Sámi, the dead person remains a key presence: ‘it was just like the dead person wasn’t dead and they spoke directly to them. Many times the memory of the dead was so strong that one is able to see the dead … ’

After life

Functions: social consolidation after death; making sense of death

In our data, social consolidation was seen as one salient means for making sense of death; to do justice to these data, we therefore combine these integrated functions here. A dominant aspect in the interviews was the various means of dealing with grief among Sámi people. While there were clear cultural patterns, there was also great individual and geographic variation in how these came into play.

People

As in other functions in the death system, a sense of community with the extended family and other Sámi is a central feature in all interviews. A number of interviewees spoke of the Verdde system (North Sámi spelling) (Nordin, Citation2002). This is an informal system for balanced reciprocity between a Sámi family working with reindeer husbandry, and one which does not, irrespective of the latter’s background. In the death system, verdde means that the people in mourning are helped and supported with practical aspects of life by non-mourners. As Maria described, ‘It was … this host family [those providing support] that was central to the whole grief process.’

Places

The link between the Sámi and nature continues to be important after death, and this quote from Susanne illustrates several points:

I have a special mountain, where I replenish my soul. It is like my holy place. And I’ve said that I can be cremated and my ashes spread there. ‘Yes, but’ my children say, ‘then we don’t have any … place to go to’. ‘No’, I say, ‘I will be with you anyway.

This woman described her mountain as a spiritually important place for her, but a generation gap, with her children wanting a more formal burial ground, also becomes evident. She also expresses a Sámi belief, heard in many interviews, that her involvement in life does not end with her death.

An aspect which became most evident when speaking about the afterlife was the importance of the church. This is illustrated when Mike, a older Sámi who had worked in a church congregation, spoke about the silence surrounding an old burial ground in the mountains:

There is a very strong influence from the church, these old places, sacred places and such. There used to be complete silence about them. You didn’t say anything, even though you knew that just on the other side of the lake, you have them, but …

Even if surrounded by a mantle of silence, it was repeatedly emphasised that old traditions and places remained central in their importance in helping make sense of death and dying. Mike continued,

… at least not in our generation that comes from these genuine Sámi environments where you’ve grown up [it’s not] possible to just erase, no, because it sort of sits very deeply inside of us.

While making sense of death and dying takes place to a great degree through a sense of community and social consolidation, our data suggest that this is hampered to some extent by the church and a need for discretion, if not secrecy. This lack of openness is also seen in relation to mainstream Swedish society, as noted in this conversation between the researcher (R) and Laila (L):

L: Yes, exactly. We have to obey … the Swedish laws.

R: Yes, that’s the case. Do you think it’s a problem?

L: It has undeniably meant that we have both given up and have had to give up routines; that is, rituals we have had … and those rituals that do exist, people may not talk about them, because then someone else finds out about it and all that … So I absolutely think … there’s a lot that doesn’t exist anymore, because we are part of a larger society.

Times

The integration of time and place is again seen here in relation to the way death is made sense of through rituals for bereavement, as stated simply here by John: ‘It was time for grieving, so they went to the mountains’. In the same manner that time and place are integrated, so are the past and present in these data, with ways of conceptualising proximity to nature and the landscape that test Kastenbaum’s categories. As the elder Sámi minister Erik noted, ‘They live with their past and feel that they are a part of it. And part of it in a very real way’.

Objects/symbols

Ways of making sense of death are seen in relationships to some objects, recruited into the death system as they become clear symbols for bereavement. Sara spoke of the ritual of a wife switching fingers for her wedding ring after her husband’s death. She also talked about how using one’s deceased husband’s traditional Sámi shoe bands was part of a grieving process – a marker for others to see as well as a physical enactment of grief in the minutes it took to ritually tie and untie them each day. Peter also noted the role shoe bands play as a ‘rite of passage’:

But there are … many of these outer signs like a sorrow band and voedtege [traditional shoe bands], they are, yes, a daily reminder of the new situation … Both morning and evening when you have a [deceased spouse], so it’s a reminder.

In Sámi languages, there are ways to denote a change in status between the living and those who have died but remain present. Relatives are spoken of with a word preceding their name to connote their new status as dead, a phenomenon called ‘laahkoestidh’ in the South Sámi language. Laila described this:

… in the Sámi language, when we say “åemie” [term preceding name after death], it is really a very nice thing. It’s such a clear and quick thing to say, that shows … that the person is there, but still shows that the person has travelled on.

Another North Sámi-speaking person, Anna, talked about how naming relatives could include both the past, present and future, laughing about a combination of terms that would indicate her future, but now deceased father-in-law: ‘and then it would be vuohpasássa, rohki’. Keeping a name in an extended family over generations was said to be another sign of how the dead remain present; however, this is only one expression of a key feature in the Sámi culture, as Maria said,

the Sámi way of thinking about this with death and … not just eternally gone, but also eternally remaining present. And therefore … it’s important … that the name lives on in the family.

Several people pointed to the role of the church in supporting bereavement, particularly those with a church affiliation. The need for social consolidation and a sense of identity as a Sámi in the grief process was also addressed. The minister Kurt, not himself Sámi, speaks of yoik as an expression for loss: ‘But in the same way that yoik can be expressed through yoik’s form so that it is something natural … it is as suitable for sorrow’. Another example was the tradition of ‘having to continue’ from the church service to a burial graveside when these occurred together. Peter said this was to be able to ‘leave a little bit of your grief there also.’

Suicide: beyond Kastenbaum’s model?

As previously noted, suicide is perhaps the most well-recognised issue related to death and dying among Sámi in Sweden and was spontaneously addressed by half the interviewees. Kastenbaum’s death system provided no help in interpreting suicide-related issues with respect to the way they were discussed in our data. We therefore make an effort to raise a few pertinent issues here.

Despite raising the issue themselves, several interviewees mentioned how much more difficult it was to speak about suicide, compared with other death-related topics. Mike said,‘… when it’s about suicide … it’s just impossible to talk. There aren’t any openings for conversation … ’. Despite this, funerals of those who committed suicide were described as well attended, and sometimes particularly moving: ‘there was reflection from everyone who was close, and “should have seen something” and “I didn’t notice anything” … even the men were crying too.’ Monica also spoke of the shame felt by those who should have been aware of the impending suicide. There was also discussion about potential causes for, as well as interpretations and responses to, suicide among the Sámi. The conditions for reindeer husbandry were said to have become harder over time, acting as one trigger for the increase in suicide. Susanne commented on the negative cycle she perceived:

Most often you only see it in media [about suicide] that there is a high suicide rate and then … Swedish society is even more like – you see, those people are mentally ill, … . Not much more is said …, except that you have a bigger burden on your shoulders. And you have to defend yourself.

There was also discussion of types of support available, both in terms of prevention of suicide and for those mourning after a suicide. The church was mentioned as an important actor in these formal support structures; however, many comments again focused on the need for strong community engagement among Sámi.

Discussion of findings

In this article, we describe contemporary Sámi death systems, based on 15 interviews with both Sámi and non-Sámi individuals chosen for their substantial experience-based knowledge of EoL issues among Sámi. We also investigate the extent to which Kastenbaum’s model of death systems is relevant in this context. In and , we summarise our main empirical findings in relation to Kastenbaum’s conceptualisation of the components and functions of a death system for Sámi. We conclude that the model provides a cohesive framework for understanding many aspects of the death system that were Sámi-specific as well as what is changing over time. However, whereas Kastenbaum differentiates among the components of the death system, based on our analysis, we found these were often so interrelated as to be nearly inseparable among the Sámi. Seasonal changes and relationships to nature instead of calendar time dominated many aspects of this death system, linking people, places and time – time was more central than were timepoints, or times, the term used by Kastenbaum. The role of the extended family in enculturation across generations and support throughout the EoL was salient. This is noted by Nymo (Citation2011) in her thesis. Sámi identity and sense of community appeared central with numerous markers of Sámi culture, both death-specific and those recruited into the death system, serving to strengthen community identity in the EoL.

Table 1. Components of Sámi death systems.

Table 2. Functions of Sámi death systems.

Walter (Citation2008) points out that Kastenbaum’s model has been surprisingly underused. Recently Noonan (Citation2018) and Liu and van Schalkwyk (Citation2018) appear to have used the model in their research, although only as sensitising concepts (Schwandt, Citation1997) rather than as an analytic tool. Both the Sámi and non-Sámi researchers in our team, who were able to work fruitfully with their complementary experiences, backgrounds and perspectives, found the model helpful when applied after data were collected and analysed. It also was a way to view data that was familiar to the Sámi researchers in a new light, thus providing new understanding. However, the ways in which the model’s limitations could constrain research must also be considered. Åhrén Snickare (Citation2002) points to the limits of generalising and categorising into systems which risk missing the local, specific and contradictory. While there may have been benefits in applying Kastenbaum’s model from the onset, we might have risked missing the manner in which it does not suit the Sámi context. Notably, Kastenbaum’s conceptualisation of discrete but interrelated components using the U.S. as examples appears to derive from a world view which differs from the Sámi, thus impacting on its relevance.

One example can be seen in relation to the component Time(s), with which Kastenbaum refers to particular time-points, e.g. holidays, prayer times and other occasions for commemoration. In our data, time is rarely mentioned in relation to the calendar or to specific time-points but is spoken of in terms of seasons, natural phenomena and mobile pastoralism as well as in terms of things having to ‘take their time’ – from funeral rituals through grief. Time is reflected in language, with strong links between the past, present and future. Indigenous researcher Smith (Citation2012) discusses how different orientations to time and space are reflected in different societies, noting, e.g. the Western perspective as linear. She notes that other temporal perspectives are expressed in many Indigenous communities, e.g. through links to the land and often conflict-filled encounters between traditional and modern societies, which affect relationships with one’s own history and become visible in relation to death. This is reflected in our data, as traditions are to different degrees conveyed over time, rediscovered and adapted, and disappear – not always without generational conflict. As Åhrén Snickare (Citation2002) points out, culture both shapes historical reality and is shaped by it.

Given the importance of culture, what demands can be placed on those providing formal care for EoL? Many terms are used in the literature, with Evans et al. (Citation2012) finding cultural sensitivity most common. We suggest that cultural humility, as defined by Foronda, Baptiste, Reinholdt, and Ousman (Citation2016) might be an alternative, applicable term, which suggests ‘openness’, ‘self-awareness’, ‘egoless’, ‘supportive interactions’, and ‘self-reflection and critique’. The consequences Foronda et al. (Citation2016) found this to have are ‘mutual empowerment’, ‘partnerships’, ‘respect’, ‘optimal care’ and ‘lifelong learning’. These seem to be appropriate characteristics and outcomes for addressing the potential challenges for EoL care we found by exploring Sámi death systems, and which are in line with those described by Caxaj, Schill, and Janke (Citation2018) in relation to palliative care for Indigenous populations. These challenges include those related to environmental and contextual issues, e.g. geographical remoteness; dissatisfaction with general practitioners’ language skills (Nystad, Melhus, & Lund, Citation2008); institutional barriers which in the case of Sámi are exacerbated by mobile pastoralism; and interpersonal dynamics which limit trusting relationships (Daerga et al., Citation2012). Based on our findings and the literature, we join Blix and colleagues (Blix & Hamran, Citation2015, Citation2017) in their call for language and culture-dependent health and care services for the Sámi at the EoL.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by: the Swedish Research Council for Health, Welfare and Working Life (FORTE) (grant # 2014-4071) for the DöBra Research Programme; Umeå University Dept. of Nursing; and the Centre for Rural Medicine.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lena Kroik

Lena Kroik, is a doctoral student at Department of Nursing, Umeå University, from a Sámi reindeer hearding family in northern part of Sweden. She is a district nurse, and presently employed at the Centre for Rural Medicine in Storuman. In addition to conducting research on Sámi experiences, knowledge and needs about dying, death, grief and end-of-life care, also work with education in emergency care and first aid in remote areas.

Olav Lindqvist

Olav Lindqvist, RN, PhD, has mainly worked clinically as a registred nurse in primary care and specialized palliative home-care. He was senior lecturer in palliative care in Umeå University´s Department of Nursing from November 2013 until his death in 2018, and was co-PI of the DöBra research program, through his research position at Karolinska Institutet at LIME. He contributed significantly to the ideas, analysis and conceptual framwork underlying this article until his death.

Krister Stoor

Krister Stoor was born and bred in the north of Sweden. He is presently Director of Várdduo - the Centre of Sámi Research and Associate Professor at Dept. of Language Studies/Sámi dutkan, at Umeå University, Sweden. He is on faculty in the section of Sámi dutkan/Sámi Studies at Umeå University where he earned his Ph.D in 2007, based on folklore and narrative research on yoik (the Sámi way of singing) tales.

Carol Tishelman

Carol Tishelman is a RN, born, bred and educated in the US, but has lived in Sweden for most of her life. She is presently Professor of Innovative Care at Karolinska Institutet´s Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics (LIME), Division of Innovative Care at Stockholm and at Stockholms Health Care Services (SLSO), which is the agency responsible for non-acute health care in the region. She has been a researcher in the field of cancer and palliative care since receiving her doctoral degree in 1993, and is now leading the national DöBra research program, at the intercept of public health and palliative care.

References

- Åhrén, C. (2008). Är jag en riktig same?: en etnologisk studie av unga samers identitetsarbete ( Diss). Umeå universitet, Umeå. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-1935$$DFulltext

- Åhrén Snickare, E. (2002). Döden, kroppen och moderniteten. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Blix, B. H., & Hamran, T. (2015). Helse- og omsorgstjenester til samiske eldre temahefte. Tromsø: Senter for omsorgsforskning i nord, UiT Norges arktiske universitet. Tønsberg: Aldring og helse.

- Blix, B. H., & Hamran, T. (2017). “They take care of their own”: Healthcare professionals’ constructions of Sami persons with dementia and their families’ reluctance to seek and accept help through attributions to multiple contexts. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 76(1). doi:10.1080/22423982.2017.1328962

- Caxaj, C. S., Schill, K., & Janke, R. (2018). Priorities and challenges for a palliative approach to care for rural indigenous populations: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(3), e329–e336.

- Daerga, L., Sjolander, P., Jacobsson, L., & Edin-Liljegren, A. (2012). The confidence in health care and social services in northern Sweden–a comparison between reindeer-herding Sami and the non-Sami majority population. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(6), 516–522.

- Dagsvold, I. (2006). ’In gille huma’. De tause rommene i samtalen: Samiske fortellinger om kreft. (Masteroppgave). Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø.

- The Economist. (2015) Quality of death index. Retrieved from http://www.eiuperspectives.economist.com/healthcare/2015-quality-death-index

- Evans, N., Meñaca, A., Koffman, J., Harding, R., Higginson, I. J., Pool, R., & Gysels, M.; on behalf of Prisma, M. (2012). Cultural competence in end-of-life care: Terms, definitions, and conceptual models from the British Literature. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(7), 812–820.

- FAO. (2016). Understanding mobile pastoralism key to prevent conflict. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/pastoralist-knowledge-hub/news/detail/en/c/449730/

- Foronda, C., Baptiste, D.-L., Reinholdt, M. M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217.

- Gott, M., Moeke-Maxwell, T., Morgan, T., Black, S., Williams, L., Boyd, M., … Hall, D.-A. (2017). Working bi-culturally within a palliative care research context: The development of the Te Ārai Palliative Care and end of life research group. Mortality, 22(4), 291–307.

- Gunér, A. (2011). Språklagen i praktiken: Riktlinjer för tillämpning av språklagen. Stockholm: Språkrådet.

- Håkanson, C., Öhlén, J., Morin, L., & Cohen, J. (2015). A population-level study of place of death and associated factors in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 43, 744–751.

- Hassler, S., Johansson, R., Sjolander, P., Gronberg, H., & Damber, L. (2005). Causes of death in the Sami population of Sweden, 1961–2000. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(3), 623–629.

- Hassler, S., & Sjölander, P. (2005). Vetenskapliga studier av samernas hälsosituation under senare delen av 1900-talet: En litteraturöversikt.

- Heckathorn, D. D. (2011). Comment: Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 41(1), 355–366.

- Ingold, T. (1980). Hunters, pastoralists and ranchers: Reindeer economies and their transformations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kastenbaum, R., & Moreman, C. M. (2018). Death, society, and human experience. New York: Routledge.

- Kelley, M. L. (2010). An indigenous issue: Why now?(editorial). Journal of Palliative Care, 26(1), 5.

- Liu, Y., & van Schalkwyk, G. J. (2018). Death preparation of Chinese rural elders. Death Studies, 1–10. doi:10.1080/07481187.2018.1458760

- Myrvoll, M. (2011). Døden er den andre verden. Religion Og Livssyn, 23(1), 32–37.

- Noonan, K. (2018). Renegade Stories: A Study of of deathworkers using social approaches to dying, death and loss in Australia. ( Social science), Western Sydney University. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kerrie_Noonan/publication/328403568_Renegade_Stories_A_Study_of_deathworkers_using_social_approaches_to_dying_death_and_loss_in_Australia/links/5bcaef4f299bf17a1c620040/Renegade-Stories-A-Study-of-deathworkers-using-social-approaches-to-dying-death-and-loss-in-Australia.pdf

- Nordin, Å. (2002). Relationer i ett samiskt samhälle: en studie av skötesrensystemet i Gällivare socken under första hälften av 1900-talet ( Diss). Umeå: Univ, Umeå.

- Nymo, R. (2011). Helseomsorgssystemer i samiske markebygder i Nordre Nordland og Sør-Troms. Praksiser i hverdagslivet.” En ska ikkje gje sæ over og en ska ta tida til hjelp”. Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø.

- Nystad, T., Melhus, M., & Lund, E. (2008). Sami speakers are less satisfied with general practitioners’ services. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 67(1), 116–123.

- Oskal, N. (2000). On nature and reindeer luck. Rangifer, 20(2–3), 175–180.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283.

- Sametinget. (2017). Renägare nyckeltal 2017 svenska Sápmi. Retrieved from https://www.sametinget.se/statistik/ren%C3%A4gare

- Schwandt, T. A. (1997). Qualitative inquiry. A dictionary of terms. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. London: Zed Books.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2018). Socialstyrelsen. Retrieved from http://oppnajamforelser.socialstyrelsen.se/aldreguiden/Sidor/default.aspx

- Stoor, K. (2007). Juoiganmuitalusat-jojkberättelser: En studie av jojkens narrativa egenskaper (Diss). Samiska studier, Umeå: Umeå universitet.

- The Swedish Register of Palliative Care. (2017). Annual report 2016 [in Swedish]. Retrieved from http://palliativ.se/fou/fou-in-english/

- Tervo, H., & Nikkonen, M. (2010). «In the mountains one feels like a dog off the leash»—Sámi perceptions of welfare and its influencing factors. Vård I Norden, 30(4), 9–14.

- Thorne, S. E. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (2018). Who are indigenous peoples? Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf

- Walter, T. (2008). The sociology of death. Sociology Compass, 2(1), 317–336.

- Wängberg, H. Å. (1990). Samerätt och samiskt språk: Slutbetänkande. ( 91-38-10680-9). Stockholm: Allmänna förl.

- Wegleitner, K., Heimerl, K., & Kellehear, A. (2015). Preface. In K. Wegleitner, K. Heimerl, & A. Kellehear (Eds.), Compassionate communities: Case studies from Britain and Europe (pp. xiii). London: Routledge.

- Young, T. K., Revich, B., & Soininen, L. (2015). Suicide in circumpolar regions: An introduction and overview. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 74(1), 27349.