ABSTRACT

In the Netherlands, until the years mid eighty of the previous century, in accordance with the so called ‘breaking bonds’ paradigm at the time, children who had died around birth, were immediately separated from the parents. There and above, Roman Catholic rules dictated that children who had not been baptized before they died, would be buried anonymously in hideaway, and in the unconsecrated grounds of the graveyard. This article discusses these parents and their stillborn children. Their loss and grief remained for a long time unacknowledged, resulting in feelings of disenfranchised grief. These feelings increased as a result of the shift of paradigm into continuing bonds with a deceased, developing into the nowadays empathic and intimate contact between parents and stillborn children. With the emergence as of the year 2000 of monuments to stillborn children (in the Netherlands around 160 in total),monuments have become a strategy to cope with feelings of disenfranchised grief.

This article concludes that parents of stillborn children benefit from an honourable place to commemorate and pay respect to their long-time publicly neglected child.

Introduction

The birth of a child, it is usually assumed, is one of the happiest moments in the life of a family. Nevertheless, occasionally infants die very soon after birth, or are stillborn and the moment of welcoming new life to this world coincides with saying farewell and acute grieving. When this happens, the support and guidance of medical professionals is of the utmost importance to parents. In a Dutch documentary from 2008 on premature babies with severe health problems, this is clearly shown. A doctor informs the father that they will be unable to save his child, born moments before at 26 weeks of pregnancy. They expect the child to die at any moment. The doctor says to the father: ‘Touch your child, give him a kiss with all you have in you, everything you have on your mind, give it to your child’.Footnote1 The doctor has to repeat her message because the father hardly understands what she is saying. But then he follows her advice, starts to cry and kisses his child farewell. He then leaves the room, probably to go and inform his wife who is been taken care of elsewhere in the hospital.

This documentary offers an insight into the care of babies in danger of death around their birth and bears witness to profound changes in that care over the last forty years. Until the 1980s, the death of children around their birth was handled completely differently by medical professionals as is evident from the testimony of one mother. She was not allowed to see nor touch her child: ‘They did not tell me why I was not allowed to see her. It was my child, our child, there was no explanation nor any comfort’ (Faro, Citation2015) Children who died shortly before, during or shortly after birth were not buried with the traditional funeral rituals and services. The hospital, or the father took care of an anonymous and sober burial and nobody ever spoke again about what had happened. Until the year 2000, children in the Netherlands who died around birth, were only commemorated within the privacy of their own family, not publicly.

The dedication of a monument to stillborn children in 2000, in the Dutch village of Reutum, caused an avalanche of attention in the public media. Since that time more than 160 monuments have been established in the country.Footnote2 Most of them have been erected at the premises of graveyards or crematoria or next to (mainly Roman Catholic) churches (Faro , Citation2011; Peelen, Citation2011).

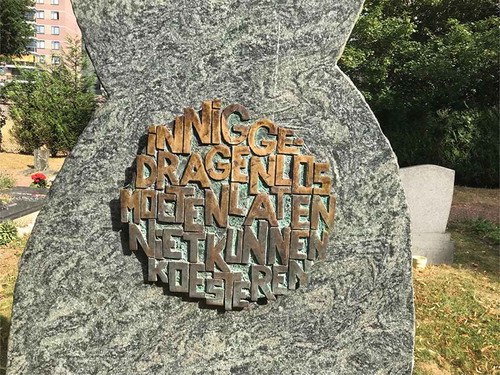

A well-known example is the monument at a cemetery in the city of Sittard, initiated by Ria Ruyters and her husband () in 2009. The monument is in the vicinity of the place where their little daughter was buried and is a sign of recognition of the lost child and validation of long-time hidden and ignored grief:

It is a place of remembrance, to stand still, alone or together, and respect all those children who did not get a name but who became part of our life. The monument allows parents to settle down and come to terms with their silent loss and grief. (Author, Citation2015)

The exact burial place of many stillborn children is not known. Many years after the death of their child, many parents still feel an enormous grief. They remain upset about the about the neglect of their loss and the lack of social support they were offered. Kenneth Doka’s terms ‘unrecognized loss’ and ‘disenfranchised grief’ seem appropriate here (Doka, Citation1989, Citation2002). Seeking the place of burial and erection of monuments and the public attention it brings, even many years after the stillbirth, help parents with their experiences of disenfranchised grief.

In this paper I focus on the meaning these monuments have for parents of stillborn children. I ask: ‘How do Dutch monuments for stillborn children help parents in coping with feelings of disenfranchised grief?’ The objective of this exploration of the meaning of the monuments is to illustrate why a monument constitutes currently such an important element in commemoration practices of parents of children stillborn many years ago. Why do people put so much effort into the erection of a monument, most of the time long after they lost their child? Does a monument ‘repair’ the injustice done to them and to their child?

This paper draws on an exploratory study involving qualitative methods of data collection and analysis. I conducted twenty-six interviews with parents, artists, medical professionals, undertakers and employees of graveyards, representatives of the Roman Catholic church and local municipality. The paper speaks of people directly involved with monuments to stillborn children, in particular the emotions and meaning they associate with the monuments.Footnote3 I will first describe the management of stillbirth up to the mid–1980s and how this has resulted in feelings of disenfranchised grief for many parents. I will then focus the factors that contributed to parents’ feelings of disenfranchised grief, in particular the bereavement paradigm at the time of ‘breaking bonds’ with the deceased (Freud, Citation1917; Neimeyer et al., Citation2002). In this respect the change of paradigm into ‘continuing bonds’ with a deceased will be discussed (Klass & Steffen, Citation2018). Presently the gold standard of care in the Netherlands is to provide parents with information on all relevant issues and allowing them to make informed decisions at the time of stillbirth.Footnote4 Nowadays parents’ grief is acknowledged and respected. Parents have options to pay respect and memorialise their stillborn child in order to continue their bonds with the baby, and they may make their own choices in this respect. This is in sharp contrast with parents in my study. Many of them are still trying to cope with feelings of sorrow, guilt and anger about the neglect and disrespect of their loss. I will explore the strategies that parents have developed in order to cope with their feelings of disenfranchised grief. I focus on parents’ search for the last resting place of their stillborn child and their attempts to mark this place with ritual acts and objects. Finally, I will consider and discuss the function and meaning of monuments in the context of theoretical concepts on place and space. In this respect I will explore the case of the Sittard monument Een glimlach kwam voorbij (‘A smile passed by’). This monument has been selected for discussion in this paper as it is representative of other Dutch monuments that have been studied in the course of the research by the author.

Stillbirth, disenfranchised grief and towards continuing bonds

In the Netherlands, up to the mid-1980’s, doctors, midwives, and nurses, determined what happened at the time of birth. According to the protocols at the time, stillborn children were most often taken away immediately after birth. Mothers were not allowed to see their child, fathers were sometimes able to catch a glimpse. Gynaecologists were taught that emotions should not be raised by acquainting the parents with their stillborn child. It would be more difficult for them to handle their loss once they had held their child. General practitioners attending deliveries at the residences of parents adopted these practices as well. In other countries, these protocols prevailed too. In 1986 in the United States, John Defrain, Leona Martens, Jan Stork and Warren Stork carried out a survey among parents of stillborn children, ‘forgotten parents’ they called them (DeFrain et al., Citation1986, backcover). One of the bereaved parents said: ‘The theory some medical people are operating on, of course, is that not looking makes it easier to “forget”’ (DeFrain et al., Citation1986, p. 54). In her account of pregnancy loss in America, Linda Layne (Layne, Citation2003, p. 223) quotes Michael Berman on his obstetrical training in the 1970s:

That if a child was stillborn or born with a serious, “unsightly” birth defect, the physician should attempt to protect the parents from the “shock” of seeing their dead child by covering it with a blanket, quickly removing it from the delivery area, and sending the body to the morgue to be buried in an unmarked grave. (Berman, Citation2001, p. xvii).

Miscarriages and stillborn children were not considered a loss that should be mourned (Lovell, Citation1983). One of my interviewees, Ria Ruyters, described the stillbirth of her first child thus:

Our first daughter was stillborn in 1969 in the hospital in Sittard. She was full-term, unfortunately she had already died before birth. The baby, a girl, was immediately taken away, I did not see her. Nobody ever spoke about her and I did not ask. My husband saw her, lying in her little coffin, thank goodness nicely dressed by the hospital. He took her to the cemetery where he had to hand her over. My husband was not allowed to attend her burial. And that was is it! I was only 22 years old at the time and let it all happen because I thought that was the way it ought to happen. You came home empty-handed, and the child’s bedroom had already been cleared and everything was soon business as usual. (Author, Citation2015).

Ruyters’ account suggests that at the time, the social environment of parents did not acknowledge their loss of a stillborn child nor were these parents allowed to grieve them in public. Dutch parents were almost ‘forced’ to ‘deny’ and ‘ignore’ their stillborn child as if it had not existed at all. Their grief was marginalised and there was no specific death- or funeral related ritual for their stillborn child.

Questions of how to ‘handle’ the loss of a loved one have long been a subject of research in bereavement studies. Up till the 1990s, the ‘breaking bonds’ approach was dominant. This paradigm is based on the ideas of Freud and suggests that the bereaved should be freed from all ties with the deceased in order to create energy for new relationships (Freud, Citation1917). The management of stillbirth at the time described above, seem to be founded on the breaking bonds paradigm. This has left the parents in my study with feelings of unrecognised loss and empathic failure (Neimeyer et al., Citation2002). Doka coined the term ‘disenfranchised grief’ (Doka, Citation1989, Citation2002), grief experienced when loss is not openly acknowledged. While a loss has been experienced, there does not seem to be a ‘right’ to grieve that loss because the social context does not recognise that loss as a legitimate cause of grief. Doka mentions abortions and miscarriage specifically and says: ‘For example, in earlier eras abortion and miscarriage were rarely addressed, recognized, or mourned. Grief over these events may re-emerge in later life.’ (Doka, Citation2002, p. 164).

In his landmark study on the bereavement of parents whose children had died at a young age, Dennis Klass reports on how parents found solace in retaining an elaborate bond between themselves and the inner representation of their deceased children (Klass, Citation1993, p. 360; Klass et al., Citation1996; Klass & Steffen, Citation2018). This can be seen as the beginning of a shift of paradigm in bereavement studies, from ‘breaking bonds’ to ‘continuing bonds’ (Klass et al., Citation1996; Walter, Citation1996). Tony Walter argues that the bereaved may ‘retain the deceased’ (Walter, Citation1996, p. 23) and the relationship does not have to be severed but may be transformed. In 2018, more than 20 years after the term ‘continuing bonds’ was coined, Klass and Steffen conclude that retaining bonds with the deceased is an accepted option in bereavement processes (Klass & Steffen, Citation2018).

At the end of the 1960s, attention started to be given to the process of grieving of stillborn children (Bourne, Citation1968). In the Netherlands, the first results of scientific research on this mourning process were published in the 1980s (Hohenbruck et al., Citation1985; Keirse, Citation1989; Lambers, Citation1980). It was at that time that medical professionals first became aware of the fact that the bonding between a parent and a child had already started before birth. With respect to this change of paradigm new protocols and guidelines were developed. The practice is now that immediately after a stillbirth parents should be encouraged to spend time with their child instead of separating parents and child. This has become an important element in the grieving processes of parents. Parents are encouraged to hold their child, to hug it, and to take care of it. Deborah Davis observes that nowadays the ‘gold standard of care is to approach parents with the knowledge that this baby is theirs and to support them in spending as many hours or days and nights as they want with their little one.’ (Davis, Citation2016, p. xiii). Lau et al conclude that continuing bonds may help legitimise and concretise the loss (Lau et al., Citation2018, pp. 155–156). Organising a funeral for stillborn babies, with accompanying rituals, has become part of the bereavement process. Coping with the loss should be done by remembering the child, the advice is now. It is considered important to actually ‘create’ remembrances in the short time between the child’s birth and its funeral. Nowadays, pictures are made, footprints or a piece of hair are kept, all matters to identify with the child at a later time (Cadge et al., Citation2016; Meredith, Citation2000; Riches & Dawson, Citation1998).

While guidelines and education have improved care and concern for bereaved parents, perinatal loss is still considered a type of ‘ambiguous loss’ (Lang et al., Citation2011, p. 183). Lang et al conclude that the juxtaposition of the parent’s grief ‘with society’s minimisation often disenfranchises them from traditional grieving processes.’ (Lang et al., Citation2011, p. 183). In fact, awareness of the new approach of continuing bonds, increases already existing feelings of disenfranchisement that the bereaved parents in my study expressed. Their loss happened at a time when the loss of a child at birth was considered to be a medical setback instead of a human tragedy (Lovell, Citation1983). Parents who were at the time not able to see nor bury their stillborn child have noticed that since that time the opinion on how to act when a child is stillborn has changed. For many of them this had an effect their own experiences and they now recognise their experiences as a form of disenfranchised grief that was ‘not openly acknowledged, publicly mourned or socially supported.’ (Doka, Citation1989, p. 4). They now realise how ‘limited social support there was for what may be considered by much of society as a non-event.’ (Cacciatore, Citation2010, p. 135; DeFrain et al., Citation1986).

The Sittard monument, mentioned above, had a snowballing effect as other parents broke the silence around their lost children. All over the country parents began developing strategies to cope with their feelings of unacknowledged loss and disenfranchised grief. I will now discuss these strategies developed by parents of stillborn children to come to terms with their disenfranchised grief and I will take the story of the Sittard monument as an example.

Strategies to cope with disenfranchised grief of stillborn children

The search for the last resting place of stillborn children

Ria Ruyters and her husband learned through the media about a monument for stillborn children in Roermond, a city nearby Sittard. Upon visiting that monument, emotions long time hidden returned. It felt to them as if the silence about their daughter who died so long ago was finally broken. They also became aware of the fact that they were not alone in their sorrow. They met many other parents with similar feelings. Now that the silence had been broken, the first thing they wanted to do was to find out about the place of burial of their own daughter. This place could finally be retraced with the aid of one of the employees of the cemetery. This employee has now assisted many other parents in locating the place where their stillborn child was buried. He explains that in the vicinity of the present monument, hundreds of children have been buried anonymously with only a little sign with a number ():

It happened almost every other day that the undertaker passed by with a stillborn child in a little coffin which we had to bury. The parents did not attend, which I thought was strange, but that was how things were done in those days. A couple of years ago, Mrs. Ruyters came to see me. She asked me if I could help her find the little grave of her daughter, which I could because we have been registering everything, also the stillborn children. Ever since that time, I have been able to help about 100 parents in finding the grave of their child. (Author Citation2015, pp. 213–214).

Ria Ruyters and her husband were lucky to be able to trace the place of burial of their daughter; many other Dutch parents of stillborn children were not. They remain unaware of what happened to their child after it was taken away at the time of stillbirth. If they were Roman Catholic, and the child had not been baptised, the child would have been buried in the unconsecrated grounds of a graveyard. In many cases there would be no registration (Gamble & Holz, Citation1995). With the media attention after the first monument in the village of Reutum had been dedicated in 2000, new facts emerged. Hospitals it turned out, had made ‘arrangements’ with local cemeteries.Footnote5 Pieter Lammers, son of an undertaker in the city of Helmond, informed a local newspaper that in the 1960s, it had been his job to bury stillborn children. He describes a remote corner of the graveyard: ‘They are all over here, that’s where we had to bury them.’ He thinks it is important that parents are finally told where that place is.Footnote6 In the same article Joke Dekkers explains how she has been searching for more than 37 years for the final resting place of her daughter, Lotte. Because of the article in the newspaper many parents of stillborn children requested to be informed about the last resting place of their stillborn child. In a television documentary husband and wife Jan and Clara de Vaan said that for 34 years they had been unaware of the last resting place of their child who had been stillborn in 1967. By means of a well-thumbed notebook, owned by the warden of the local cemetery in the city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, they were able to retrace the exact location.Footnote7

In the city of Roermond, the Laurentius hospital participated actively in the erection of the monument. When parents now ask them about the fate of their stillborn children, they have to disappoint them because, apparently, these children were cremated at the time and no records have been kept. The hospital emphasises with the monument that in a way they feel responsible for what happened at the time (Author Citation2015, pp. 200–211). In the Roman Catholic hospital in the city of Hertogenbosch, nuns told parents of stillborn children that in those days they put them in coffins together with other deceased persons. At the time, parents accepted these stories, but nowadays they doubt them (Author, Citation2015, p. 183). In the village of Liempde, the wardens know for sure that more than 224 stillborn children have been buried at the Roman Catholic graveyard. The children were registered only until the year 1942 so the number in total must be much higher.Footnote8 The monument in Liempde () is placed right before a hedge under which the unconsecrated grounds were located and where unbaptised children were buried. The monument is adorned with memorial objects, handwritten notes, flowers and funeral wreaths.

To many parents, after years of not-knowing, being silenced in their grief, retracing the place of burial is a very emotional affair. The taboo on stillborn children has finally been broken. Many parents that finally their loss has been acknowledged and they ‘allowed’ to openly grief their stillborn children. It is remarkable how discovering the place of burial unlocks long-time hidden memories and emotions and seems to be a beneficial strategy.

I will now discuss from a theoretical perspective, how emotional places and memories function in coping with disenfranchised feelings of loss and grief.

Reclaiming places of burial

I would like to illustrate the evocation of, maybe hidden, memories from the past in relation to a particular place or object, by means of a classic example from the French author Marcel Proust. In his famous novel À la recherche du temps perdu. Du côté de chez Swann Proust describes how memories which seem to have been locked up can resurface by an unexpected incident. The first – person narrator in this novel is having a cup of tea and enjoying a piece of cake, a Petite Madeleine. Through the taste of tea and cake, childhood memories are evoked. More generally speaking, through the confrontation with certain objects or places, suppressed memories may return. Edward Soja coined the term ‘geographical madeleines’ as a remembrance of places (Soja, Citation1996, p. 18). Some specific places may be helpful in returning the memory of events from the past (Soja, Citation1996, p. 18). He typifies this phenomenon as ‘a madeleine for a recherche des espaces perdus’, ‘a remembrance – rethinking-recovery of spaces lost … or never sighted at all.’ (Soja, Citation1996, p. 81). Pierre Nora has similarly discussed places that bring back memories of a collective and public past, what he calls lieux de mémoire, literally ‘places of memory’. Upon visiting these places of memory, Nora says, people are connected with the past. According to Nora it is essential to retain these places, they belong to collective history and collective commemorations: ‘Without commemorative vigilance, history would soon sweep them away.’ (Nora, Citation1989, p. 12).

Parents often have powerful experiences when they are finally confronted with the last resting place of their stillborn child: the events and the emotions of those days may be relived with the same intensity at that particular emotional place. Parents of stillborn children seem to have a need to recall places of burial and their history at the time, and for these places to be publicly recognised. Parents seem to need this, firstly, because of their own grief and secondly, in order to ensure the places stay in collective and public memory. In fact, these places have never before been part of public memory before. The reclaimed place of burial of the children appears to evoke many emotions. Many parents think it necessary to mark this place with a new meaning as part of a strategy to start a mourning process. For parents this is the place where they have never been able, nor allowed, to honour their children by performing any funeral rituals. They may mark the initiation of the mourning process now by individual ritual, performed at the place, for instance, by marking the place with flowers, putting a sign with the name of the child, or by placing ‘melancholy objects’, like toys or cuddly bears, there (Gibson, Citation2004; Maddrell, Citation2013). Rituals may also be performed collectively, in a commemoration ceremony as happens in Sittard and also in the city of Waalwijk where yearly a flower ceremony is organised at the site of the monument for stillborn babies.Footnote9

Marking the reclaimed place of burial

A next step in reclaiming the places of burial of stillborn children is marking that particular place, as may be illustrated at the Sittard cemetery on . Previously, hospitals and cemeteries, together decided where and how stillborn babies would be buried. The ‘conceptualized space’, as Henri Lefebvre called it, the place defined by the dominant parties and the ‘space’ thus attributed to stillborn children, was an anonymous and remote corner of the graveyard (Lefebvre, Citation1974, p. 38). Roman Catholic authorities determined where children of catholic parents would be buried at their graveyards. Dominant parties also decided on death rituals and how the children would be buried. Parents did not have a voice in these matters. Obviously, many years later these facts still cause a lot of emotions like sorrow and anger. Parents blame themselves that they let it all happen and did not object to the course of events. According to Lefebvre, a space with people acting, is always a ‘social space, a tool of thought and action’, as well as an agent of control and power (Lefebvre, Citation1974, p. 26). At the time, authorities controlled the space of burial of stillborn children. Parents were still young, distressed and completely caught off guard did not dare objecting. Many years later, they now take the initiative to mark these places, for example, by erecting a monument exactly at those places formerly controlled by hospital or church authorities. For example, the monument in the village of Den Dungen () is positioned against the wall of the local Roman Catholic Church.

By this parents seek to take control over these places from the dominant parties at the time. They give the places a different meaning by means of signs or monuments and throughout performing rituals. Parents seek to create what Lefebvre called a ‘representational space’, a ‘lived space’, a space with symbolic meaning through the emotions and memories emplaced there (Lefebvre, Citation1974, p. 39). In this these parental practices may be linked to the current tendency to mark scenes of disaster and trauma with spontaneous and temporary, or sometimes permanent monuments (Margry & Sánchez – Carretero, Citation2011; Post et al., Citation2003). At these places people feel connected to their lost loved ones, and there seems to be a need for a lived space of memories.

Kenneth Foote explores how and why sites of tragic and violent events have been memorialised (Foote, Citation2003, pp. 1–35). According to Foote distinctions between these sites are not fixed, changes may occur as time passes by. A site may be marked with flowers, memorial notes or other remembrances to the victims thus creating a temporal or ephemeral memorial which may be transformed into a permanent memorial at a later time. Designating the site is thus often a first step towards what Foote calls ‘sanctification’. Sites of obliteration are sites with active effacement of evidence of particularly shocking or shameful events. At many graveyards, the places where stillborn children were buried could be called places of obliteration.

Honouring the reclaimed place with a public monument

Many parents feel the need to honour the resting places of their stillborn babies. In Foote’s terms they seek to sanctify the place. A condition of sanctification, according to Foote, is a commemoration or dedication ceremony, where it is explicitly mentioned what the meaning of the place is, why it should be commemorated and kept as a sacred place. Parents of stillborn children usually invite an artist to design an appropriate object of art with a symbolic meaning and situate it on the place of obliteration. As an example, the site of the monument in Sittard may now be called a sacred space in terms of Foote. Occasionally, there will be a debate about the exact place of the monument. In Roman Catholic graveyards where the children were buried at the time in the unconsecrated grounds, parents may object to erecting the monument in those locations. They consider that a monument deserves a more prominent place: the children have been put away far too long. However, one could also argue that by placing a monument the place will be transformed: from a ‘lost place’, a non-lieu de mémoire, into a place with emotional and symbolic meaning. Another debate revolves around the dedication of monuments by representatives of the Roman Catholic Church and the consecration of the unconsecrated grounds. In many cases priests have acted in this respect but in other cases parents object against their involvement. Chidester and Linenthal argue, in line with Foote, that by means of the erection of monuments and commemorative rituals, a place is transformed into a sacred place, a place with a special meaning (Chidester & Linenthal, Citation1995, p. 9). The place of burial of stillborn children is now reclaimed from dominant parties and appropriated by parents by means of the monument and dedication rituals. Chidester and Linenthal follow the argument of Michel Foucault on power at sacred places (Foucault, Citation1984, p. 252): space is fundamental in any exercise of power. Parents are able to show their great dissatisfaction about the course of events at the time by reclaiming place and erecting monuments as public signs of power: lest nobody will forget what happened at the time and their continuing sorrow.

In the Netherlands more than 160 monuments have been dedicated to stillborn children. This appears to be a powerful strategy to cope with feelings of disenfranchised grief. Ria Ruyters and her husband followed this strategy of transforming the ‘lost space’ burial of their daughter into a special place and a sacred place by honouring it with a monument. In order to do so they set up a foundation with the name Stil verdriet (‘Silent sorrow’).Footnote10 The main objective of the foundation was to raise funds to have a monument designed and created. The foundation succeeded in this objective with funding from the local municipality and hospital. Ria Ruyters’ sister-in-law, the artist Miep Mostard-Heythuysen, was asked to design the monument. The form of the monument, the heart of the lotus flower with the seeds and the umbilical cord, are a message of love to the deceased child (). A dedication ceremony took place on 18 December 2009. The monument was consecrated by a priest from the Roman Catholic Church. The foundation considers that it has been successful in realising its objectives. By means of the monument a clear and lasting message is given about the character of the place: ‘lest we pass carelessly the place where hundreds of children rest anonymously.’ (Author Citation2015).

A monument as a replacement for a grave: the case of Lies van MelsenFootnote11

Some parents have never been able to find the place of burial of their stillborn child. Mrs. Lies van Melsen’s oldest son was stillborn in 1958 in the Roman Catholic hospital of the Dutch city of Maastricht. Mrs van Melsen has never seen or touched her boy. She explains:

You did not dare ask, I was twenty-two years old, my husband twenty-seven. And that was it. My husband went home and returned with a little white coffin, but I do not know how they put him in the coffin. Was he still naked? Did they dress him … these thoughts, they haunt me nowadays. I am eighty-two years old. My husband died four years ago. Whenever I wanted to talk he would always say: “Oh please, let it be”. (Faro, Citation2018).

When she came home from the hospital everything that might remind her of the baby was gone. She felt that at the time she needed these baby things to mourn. Her mother thought it was best not to think of him anymore. But Mrs. van Melsen says that it did not work. The boy has always been there, in her head. Maybe even more when she and her husband became grandparents. She has no grave to go to and she regrets that the boy has never been named. Mrs. van Melsen feels that in the absence of a grave, the monument at the graveyard near Sint Pieter’s church in the Dutch city of Maastricht functions as a place to honour her eldest boy. She says: ‘I have the monument of my child at Sint Pieter. I think the monument is also a sign of protest, everything was unfair at the time and we did not dare to protest. I just have to talk about what happened, that is important to me.’ (Author, Citation2018).

She feels emotionally involved through the inscription on the monument that refers to her own feelings about her lost child: ‘Silenced indeed, but never forgotten.’ ()

Discussion: the function and meaning of the Dutch monuments in the context of coping with disenfranchised grief

The research questions that informed this paper concern the function and meaning of Dutch monuments in relation to experiences of disenfranchised grief. In this section, I will first discuss the function of monuments and then focus on the meaning of monuments to parents of stillborn children.

The word ‘monument’ derives from the Latin word monere, which means ‘to make public, to remember’. Monuments function to mark important places and events, a lieu de mémoire in Nora’s terms (Nora, Citation1989; Foote, Citation2003, pp. 80–90), to bring aspects of the past to public attention. A second function of monuments can be said to be related to the management of emotions (Post et al., Citation2003, p. 41). Foote refers to the healing properties of monuments, for example, for people affected by loss (Foote, Citation2003, p. 80). Kirk Savage coined the term ‘therapeutic monument’ (Savage, Citation2009) in this context. Commemoration ceremonies and rituals may become part of a collective process of mourning with regard to people directly involved but also with regard to the public.

Adrienne Burk discusses a third ‘counter – hegemonic’ function of monuments. She refers to a type of monument meant to ‘unsettle social relations, rather than provide closure.’ In this respect Burk refers to the German tradition of so called ‘counter monuments’. The design of these monuments is specifically meant to provoke debate (Burk, Citation2003, p. 318). Counter monuments were developed as a result of the sometimes complicated and contested aspects of commemoration, for instance, in Germany after the Second World War. Counter monuments are designed not only to commemorate the past, but also to encourage and provoke spectators to reflect on the process and tradition of commemoration itself. Counter monuments may be considered as a way to provoke public discussion and became part of memory culture, in particular in Germany (Young, Citation1994, pp. 27–48; Carrier, Citation2005, p. 21). Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C., offers an interesting perspective in this context. She considers symbolism less important and emphasises that her monument is not intended to deliver a message. In her opinion, death and loss are personal and private matters. A monument and the memorial place are meant for ‘personal reflection and private reckoning’. Places where ‘something happens within the viewer’. The meaning of the monument should be generated while ‘experiencing’ the commemorative place by means of (ritual) commemoration practices, according to Lin (Lin, Citation1995, p. 13). Edward Casey considers Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial to be an effective monument because it offers a ‘public space in which the spontaneous expression of feeling and the exchange of thought are enabled and enhanced.’ (Casey, Citation2007, p. 31). Effective monuments may be contrasted with ‘ineffective’ monuments like for instance, the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, standing in the middle of heavy traffic at an uninviting place and where it will be difficult to achieve an intimacy between the monument and the commemorator (Casey, Citation2007, p. 31). Savage argues that 21st century monuments are now expected to be ‘spaces of experiences’ involving ‘journeys of emotional discovery’ rather than ‘closed’ objects of art (Savage, Citation2009, p. 21).

Dutch monuments for stillborn children may cover all functions as described above: they may be considered as markers of important events (lieux de mémoire), they may have a healing or therapeutic function and they have certainly raised the debate about what happened to stillborn children at the time and thus acted as counter monuments. The monuments seem to have multiple meanings too. They provide spaces of experience that can evoke different emotions, different meanings for different people. I take for example, the monument at the cemetery in the city of Veldhoven was initiated by representatives of the local Roman Catholic church and was designed by a Benedictine monk. The monument symbolises a woman, holding a child in her arms. Behind the woman, two plates of stone have been placed. On one of these plates a text from the Old Testament has been inscribed: ‘I, the Lord will never forget you.’ The other plate carries a text from the New Testament, an invitation by Jesus: ‘Let the children come to me.’ The monument was consecrated by a local priest on All Souls 2010. In this way, representatives of the church took the initiative to offer solace to parents of stillborn children. The practices of the Roman Catholic Church neglected stillborn unbaptised children and prohibited parents at the time to commemorate their children, something the Church now feels it needs to make amends for. This monument is intended to show parents recognition of the child. The question remains of how parents experience this monument, this expression of regret (Author, Citation2015; Peelen, Citation2011).

Some monuments are a sign of ongoing struggles with difficult feelings. In the village of Made, the pain and sorrow of the parents are the focus of a monument called ‘Het Verdrietmonument’ (‘Monument of Sorrow’). Here no mention is made of solace or resolution. In the city of Uden there is similarly a focus on sorrow and pain as expressed in the poem on the monument:

In the village of Nistelrode, there is monument to stillborn babies called: Een teken (‘A Sign’). In contrast to the monument in Uden, this monument signals consolation as expressed by the poem on the monument:

The erecting of the monuments in public space is also a sign of protest against the events of the time. Some of the monuments are an explicit statement about the injustice felt. The place of these monuments may be interpreted as an appropriation of the place. For instance, in 2003, in the village of Deurne, the remains of 45 unbaptised children which had been buried elsewhere, were reburied together in one coffin at the local cemetery. A grave monument was erected at that particular place, a monument of remembrance and contemplation. At the dedication ceremony the following was said: ‘21 November 2003, at this place, the cemetery in Deurne, we are finally able to say goodbye to our little ones in a respectful manner.’Footnote13 In the village of Groenlo the monument depicts two hands, supporting a baby. The text of the monument reads: ‘To you, because you were very welcome in our heart and in our life, finally the place we would like to have given you before.’ The children are thus, by means of the monument, offered a respectful place, which should have been given to them long time ago. Sometimes the form of the monuments, and in particular writings at the monument, appear as a call for awareness even reproach. The text at the monument in the village of Albergen is a direct accusation of the Roman Catholic Church: ‘In remembrance of all unbaptised children buried at this place. The sorrow remains forever.’ The monument in the city of Heerlen is called: Doodverzwegen kind (‘Silenced child’) ().

The text on the monument reads as follows:

The artist who created the monument and the parents and support group, that were behind its creation, intended the work as an explicit statement, an accusation of the church and all those who acted at the time to silence stillborn children.Footnote14 The monument clearly carries what Post et al call the ‘social critical function of monuments’ (Post et al., Citation2003, pp. 138–156). By brining problematic ideas and emotions into the open by way of protest, the monuments can be regarded as what Burk terms ‘counter-hegemonic’ (Burk, Citation2003, p. 318). According to Burk if monuments truly have a connotation of counter-hegemonic, they should also be analysed in this respect: ‘While physically inert, they nonetheless disturb, and challenge quite directly what we claim our societies remember.’ (Burk, Citation2003, p. 331). Rewriting history and making clear what happened at the time is relevant in this context.

Although the place, form and representation of Dutch monuments for stillborn children differ, altogether they are related in their meaning. They are a sign of consolation for parents regarding the loss of their child and the injustice done to them; they are also as a sign of protest against the course of events at the time. Instead of trying to shape individual identities by creating separate memorial stones, the monuments represent forgotten bereaved parents and their forgotten stillborn children as a collective (Francis et al., Citation2005, p. 173). Joanne Cacciatore and Melissa Flint conclude that parents seemed to use rituals as ‘a means of immortality so that their child could “live on” and [be] remembered, both privately and publicly’ (Cacciatore & Flint, Citation2012, p. 165). Most parents in their study faced a ‘public to private trajectory’ meaning that with the passage of time ‘rituals tended to become more private, at least in part due to questioning or criticising from others. (Cacciatore & Flint, Citation2012, pp. 165–166). In the Netherlands, by means of monuments erected in the public domain, parents seem to have developed a strategy to take their grief from the private to the public realm.Footnote15

Conclusion

The focus of this paper was on parents who have, until recently, been ‘forced’ for different reasons to keep commemoration of their stillborn child within a private context. For a long time, their loss and grief were not acknowledged, resulting in feelings of disenfranchised grief. Feelings of disenfranchised grief have increased due to the shift of paradigm into continuing bonds with a deceased, resulting in the now empathic and intimate contact between parents and stillborn children. Emotions rise when parents, maybe now as grandparents, experience the difference regarding the current approach to stillborn children: why were they at the time not allowed to bond with their stillborn child and give it a proper farewell ritual? With the emergence of monuments to stillborn children, in the 2000s, monuments have become a strategy for parents to cope with their grief.

I have argued, that my material shows that parents of stillborn children need a ‘place’ in order to, finally, come to terms with the loss of their stillborn child and to cope with disenfranchised grief. A monument, or a retraced grave, may ‘work’ in this respect. Sometimes, the monument, place, and commemorative ritual practices, also mean a coming to terms with the disrespectful way in which a stillbirth was handled in those days by others, like for instance, medical professionals and the Roman Catholic Church. In the Netherlands an important and continuing concern of many parents is the whereabouts of their children. Some have been able to locate this place, others have not. A monument may offer such a place instead, a place for ritual commemoration practices, which may help in the process of handling the loss, even many years after the stillbirth of their child.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laurie Faro

Laurie Faro (1957) has been educated in the field of law and culture studies. In 2015 she completed a PhD research project with a focus on people have been burdened with traumatic experiences in the past, and the impact of their ritual commemoration practices, especially at the site of a public monument. At present she is involved as a teacher and researcher at Radboud University, the Netherlands. Her present research project is entitled: Children handling death: reality versus popular culture. She has published and presented on matters of death and mourning involving children.

Notes

1. Documentary on the Neonatology Unit of the Academic Hospital in Groningen, the Netherlands Als we het zouden weten (2008), Petra Lataster – Czisch and Peter Lataster, https://www.2doc.nl/documentaires/series/hollanddoc/2008/als-we-het-zouden-weten0.html accessed 28 May 2019.

2. In this paper, I will follow the definition of stillbirth used at the time of my research by the Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie and Gynaecologie (Society of Dutch obstetricians and gynaecologists) in their patient education brochure on the loss of a child during pregnancy or during birth. In this brochure stillbirth is defined as: ‘the birth of a child who died during pregnancy (so called intra uterine death of foetus) or around birth’: currently the term ‘perinatal death’ would be more appropriate, https://www.nvog.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Nota-Wet-en-gedragsregels-rond-perinatale-sterfte-2.0-31-05-2013.pdf, consulted 7 June 2019. However, with regard to the monuments, the term ‘stillborn’ is generally accepted, in Dutch levenloos or doodgeboren children are common terms.

3. The results of this research were published in my PhD thesis Postponed monuments in the Netherlands. Manifestation, context, and meaning which I defended in 2015 at the Tilburg University, the Netherlands. All participants to this project gave their informed consent to present the results of study.

4. https://www.nvog.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Begeleiding-bij-foetale-sterfte-en-doodgeboorte-1.0-22-05-2014.pdf, consulted 29 May 2019.

5. For example, the Sint Joseph Ziekenhu is in Eindhoven, the Lambertusziekenhuis in Helmond, J. Speelman: ‘Zoektocht naar de graven van ongedoopte baby’s, het verloren kerkhof’, in Eindhovens dagblad, 13 April 2002.

6. Idem.

7. TV-programma Andere tijden, uitzending van 20 November 2001, Dossier Ongewijde aarde, on https://anderetijden.nl/aflevering/572/Ongewijde-aarde, consulted on 29 May 2019.

8. http://www.brabantscentrum.nl/oud_archief_2004/nieuws/0439_ongedoopt.htm, consulted on 29 May 2019.

10. http://www.monumentdoodgeborenkindjes.nl/files/stilverdriet3.pdf, consulted 30 May 2019.

11. https://nursingclio.org/2018/10/17/dutch-monuments-for-stillborn-children/, consulted 30 May 2019.

12. All texts translated from Dutch by the author.

13. http://www.deurnewiki.nl/wiki/index.php?title=Monument_voor_herbegraven_overleden_kinderen, consulted 16 July 2018.

14. http://www.heerlen-in-beeld.nl/Kind.htm, consulted 16 July 2018.

15. Recently another public strategy emerged. As of 10 February 2019, parents of stillborn children in the Netherlands will be able to register their children in the Personal Records Database. The birth of a stillborn child has to be registered if the child was born after 24 weeks of pregnancy. Until now, for many parents, their child was still considered ‘nonexistent’ as it does not exist in the registration of birth but only in the death register. Anybody in the Netherlands who has had a stillborn baby can now register them retroactively in the Personal Records Database, following a change in the law. For many parents who lost their child at birth long time ago, this registration may also work as a sign of recognition of the child, http://www.24oranges.nl/2019/02/06/dutch-finally-allow-the-registration-of-stillborn-children/, consulted 30 May 2019.

References

- Berman, M. R. (2001). Parenthood lost: Healing the pain after miscarriage, stillbirth, and infant death. Bergin & Garvey.

- Bourne, S. (1968). The psychological effects of stillbirths on women and their doctors. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 16(2), 103–112. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2236635/

- Burk, A. L. (2003). Private griefs, public places. Political Geography, 22(3), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(03)00035-0

- Cacciatore, J. (2010). The unique experiences of women and their families after the death of a baby. Social Work in Health Care, 49(2), 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981380903158078

- Cacciatore, J., & Flint, M. (2012). Mediating grief: Postmortem ritualization after child death. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 17(2), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.595299

- Cadge, W., Fox, N., & Lin, Q. (2016). “Watch over us sweet angels”: How loved ones remember babies in a hospital memory book. Omega - Journal of Death and Dying, 73(4), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815590731

- Carrier, P. (2005). Holocaust monuments and national memory cultures in France and Germany. Berghahn Books.

- Casey, E. (2007). Public memory in the making: Ethics and place in the wake of 9/11. https://www.academia.edu/13591009/Public_Memory_in_the_Making_Ethics_and_Place_in_the_Wake_of_9-11

- Chidester, D., & Linenthal, E. T. (1995). Introduction. In D. Chidester & E. T. Linenthal (Eds.), American sacred space (pp. 1–43).Indiana University Press.

- Davis, D. L. (2016). Empty cradle, broken heart. Surviving the death of your baby. Fulcrum Publishing.

- DeFrain, J., Martens, L., Stork, J., & Stork, W. (1986). Stillborn: The invisible death. Lexington Books.

- Doka, K. J. (1989). Disenfranchised grief: Recognizing hidden sorrow. Lexington Press.

- Doka, K. J. (2002). Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges and strategies for practice. Research Press.

- Faro, L.M.C. (2011). Van een glimlach die voorbij kwam en het stille verdriet. Plaats en betekenis van monumenten voor levenloos geboren kinderen. Yearbook for Ritual and Liturgical Studies, 27, 7–28.

- Faro, L.M.C. (2015). Postponed monuments in the Netherlands. Manifestation, context, and meaning. Tilburg: https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/files/15024988/Faro_Postponed_28_01_2015_emb_tot_28_01_2017.pdf

- Faro, L.M.C. (2018). Retrieved from Nursing Clio: https://nursingclio.org/2018/10/17/dutch-monuments-for-stillborn-children/

- Foote, K. E. (2003). Shadowed ground. America’s landscapes of violence and tragedy. University of Texas Press.

- Foucault, M. (1984). Space, knowledge, and power. In Paul Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault reader (pp. 239–256). Pantheon. https://monoskop.org/images/f/f6/Rabinow_Paul_ed_The_Foucault_Reader_1984.pdf

- Francis, D., Kellaher, L., & Neophytou, G. (2005). The secret cemetery. Berg.

- Freud, S. (1917). Trauer und Melancholie [Grief and melancholy]. Internationale Zeitschrift für Artztliche Psychoanalyse, 4, 288–301. https://www.textlog.de/freud-psychoanalyse-trauer-melancholie-psychologie.html

- Gamble, E., & Holz, W. L. (1995). A rite for the stillborn. Word & World, XV(3), 349–359. http://the-puzzle-palace.com/15-3_Gamble-Holz.pdf.

- Gibson, M. (2004). Melancholy objects. Mortality, 9(4), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270412331329812

- Hohenbruck, B., de Kleine, M., Kollee, L., & Robbroeckx, L. (1985). Rouwverwerking en begeleiding bij het overlijden van pasgeboren kinderen. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskund, 129(33), 1582–1585. https://www.ntvg.nl/sites/default/files/migrated/1985115820001a.pdf.

- Keirse, E. (1989). Eerste opvang bij perinatale sterfte. Gedragingen van ouders en hulpverleners. Acco.

- Klass, D. (1993). Solace and immortality: Bereaved parents’ continuing bond with their children. Death Studies, 17(4), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189308252630

- Klass, D., Silverman, R., & Nickman, S. L. (1996). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor and Francis.

- Klass, D., & Steffen, E. M. (2018). Continuing bonds in bereavement: New directions for research and practice. Routledge.

- Lambers, K. J. (1980). Rouw bij perinatale sterfte. Tijdschrift Verloskund, 12, 351–357.

- Lang, A., Fleiszer, A. R., Duhamel, F., Sword, W., Gilbert, K. R., & Corsini - Munt, S. (2011). Perinatal loss and parental grief: The challenge of ambiguity and disenfranchised grief. Omega, 63(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.63.2.e

- Lau, B. H., Fong, C. H., & Chan, C. H. (2018). Reaching the unspoken grief. Continuing parental bonds during pregnancy loss. In D. Klass & E. M. Steffen (Eds.), Continuing bonds in bereavement. New directions for research and practice (pp. 150–160). Routledge.

- Layne, L. (2003). Motherhood lost. A feminist account of pregnancy loss in America. Routledge.

- Lefebvre, H. (1974). The production of space (D. N. Smith, Trans.). Blackwell Publishing.

- Lin, M. (1995). Grounds for remembering: Monuments, memorials, texts. In Christina M. Gillis (Ed.), Doreen B. Townsend center occasional papers 3 (pp. 8–14). Doreen B. Townsend Center. https://townsendcenter.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/publications/OP03_Grounds_for_Remembering.pdf

- Lovell, A. (1983). Some questions of identity: Miscarriage, stillbirth and perinatal loss. Social Science & Medicine, 17(11), 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(83)90264-2

- Maddrell, A. (2013). Living with the deceased: Absence, presence and absence-presence. Cultural Geographies, 20(4), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474013482806

- Margry, P. J., & Sánchez - Carretero, C. (2011). Grassroots memorials. The politics of memorializing traumatic death. Berghahn Books.

- Meredith, R. (2000). The photography of neonatal bereavement at Wythenshawe Hospital. Journal of Audiovisual Media in Medicine, 23(4), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/01405110050198618

- Neimeyer, R., & Jordan, J. (2002). Disenfranchisement and comparative failure: Grief therapy and the co-construction of meaning. In K. Doka. (Ed.), Disenfranchised grief: New directives, challenges and strategies for practise (pp. 95–117). Research Press.

- Nora, P. (1989). Between memory and history: Les lieux de momoire. Representations, 26(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.1989.26.1.99p0274v

- Peelen, J. (2011). Between birth and death. Rituals of pregnancy loss in the Netherlands. Dissertation.

- Post, P., Grimes, R. L., Nugteren, A., Pettersson, P., & Zondag, H. (2003). Disaster ritual. Exploration of an emerging ritual repertoire. Peeters.

- Riches, G., & Dawson, P. (1998). Lost children, living memories: The role of photographs in processes of grief and adjustment among bereaved parent. Death Studies, 22(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811898201632

- Savage, K. (2009). Monuments wars. Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the transformation of the memorial landscape. University of California Press.

- Soja, E. W. (1996). Third space. Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Wiley - Blackwell.

- Walter, T. (1996). A new model of grief: Bereavement and biography. Mortality, 1(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685822

- Young, J. (1994). The texture of memory. Yale University Press.