ABSTRACT

Memorials of the lay dead in late medieval English churchyards were constructed from perishable materials, with the exhumation and reuse of burial plots suggesting that a timely forgetting of the individual was an accepted part of the commemorative process. From the 13th century onward, remains exhumed from old graves were increasingly redeposited in specific structures known as charnel houses. The collective redeposition of disarticulated skeletal remains in charnels anonymised the deceased, generating mortuary spaces which foregrounded communal rather than individual memory. In this paper, charnelling and its relation to memory in late medieval England is theorised and explored. Following this, early modern developments are investigated, employing the charnel of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, as a central case study. As the country’s largest late medieval charnel, its extreme treatment following the Dissolution of the Monasteries renders it a potent example of how religious reform affected mortuary practice during the period. Through the violent ejection of its contained remains and the structure’s secular repurposing as a print shop, treatments of the ancestral dead were employed to enact and manifest ideological change. This produced changes in London’s mortuary landscape which in turn memorialised the reformatory process itself.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Commonly, extant individual memorials of the late medieval period are located within churches and associated with individuals of high status (Lees, Citation2002). Their investigation has consequently resulted in a top-down view of the subject. In recent years, however, a broadening of the archaeosocial agenda of interpretation has directed increased attention towards lay memorialisation in both performative and material capacities (Tarlow, Citation2010, 4–5; Härke, Citation2002). Within this expanded context, recognition of the exceptionality of substantial intramural memorials has directed renewed attention to burial and memorialisation practices of the general population.

With graves marked temporarily and remains exhumed in order to free up further burial space (Gordon, Citation2015, p. 33), perpetual individualisation in death was an impossibility for many. It is implied that individual forgetting, further to remembrance, was an incorporated function of mortuary practice for the majority of lay individuals. Exhumed remains subsequently underwent collective redeposition in pits or specific structures (Gilchrist & Sloane, Citation2005: 42, p. 195) signifying a reinvestment of individual memory within communal memory. Within the following work, theoretical dimensions of late medieval burial, exhumation and charnel practice will be explored. Through this, social and memorial significances of individual/communal remembering and forgetting will be ascertained.

Following theoretical exploration of late medieval charnelling, the practice’s presence within England will be briefly outlined before the charnel chapel of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, will be pursued as a specific case study. As the country’s largest charnel (Houlbrooke, Citation2000, p. 332), this site held national as well as local significance which was reflected through its singularly extreme treatment following the Dissolution of the Monasteries. While many charnels were cleared during this period (Litten, Citation2002, p. 8), the emptying of St. Paul’s charnel and unceremonious redeposition of its contained remains provides a central case study of counter-memorial change during the period. Theoretical aspects of remembrance and forgetting will be explored through the act and implication of this event, as well as its influence on subsequent mortuary landscape developments through the non-conformist Bunhill burying ground. I will conclude by considering potential applications of the present work within late medieval English mortuary archaeology, as well as within the ongoing investigation of charnelling in England.

Death and memory in late medieval England: individual, inhumation and exhumation

In the late medieval period, the deceased played an active and ‘vital’ role in life, remaining physically and socially prominent through their positioning in churchyards in settlement centres (Ariès, Citation1981: 62; Gordon, Citation2015: 32; Davis, Citation1977: 92; Lambert, Citation2018, p. 28). Their continued spiritual presence was informed by Catholic purgatorial belief, which had been informally longstanding prior to its definition at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, affirming that intercessory prayer was beneficial to souls of the deceased in purgatory (Tittler, Citation1997, p. 286). Material culture in ecclesiastical environments expressed this through endowed decorations and fittings which exhorted prayer and relief through earthly charity (Badham, Citation2014). Memorials gave similar prompts, with inscriptions exhorting the living or divine to pray for, or grant mercy to, the deceased (Sherlock, Citation2010: 34–35; Badham, Citation2014). The living were consequently ‘encouraged not to remember the dead, but to remember and pray for the dead’ (Finch, Citation2003, p. 442).

Intercessory action was situated within ecclesiastical landscapes through general devotion as well as officiated chantries in which priests would pray on the deceased’s behalf for a fee (Roffey, Citation2017), with perpetual activity in chantries ensuring the performative as well as physical presence of memory. While ideally perpetual, intercessory acts were in reality limited in their duration by economic factors when the practice was bought and by the duration of living memory when practised by the laity. Similar impermanence was reflected through physical embodiments of memory in the landscape, with churchyard memorials and their associated burials rendered temporary by grave reuse.

Disorderly churchyard layouts inferred from excavations of intersecting burial clusters and intercut graves (Houlbrooke, Citation2000, p. 332) affirm that schemes of internal order were inconsistent and impermanent. Through successive rounds of inhumation, the imposition of new layouts over old ones resulted in the intercutting and redeposition of prior remains, suggesting that the non-localised power of prayer on behalf of the soul retained greater significance than any perpetual location of the body. As Williams (Citation2003, p. 172) asserts, memory was ‘not fixed in material culture, but mediated by it’, and furthermore held potential to practitionally transcend it.

With the preference for burial in consecrated ground exerting high demand on churchyards within the context of a doubling of the European population between 1000 and 1300AD (Daileader, Citation2019), the clearance and reuse of graves became necessary in order to accommodate further burials. Old remains encountered when digging new graves were sometimes redeposited with backfill, while others underwent collective redeposition in charnel pits or specific structures (Crangle, Citation2016: 81–82, 100–101; Gilchrist & Sloane, Citation2005: 42, 195; Gordon, Citation2015, p. 33). Grave memorials experienced similar transience through their material properties, with the decay of wood and reclamation of stone predisposing them to eventual absence (F. Burgess, Citation1979, pp. 27–29).

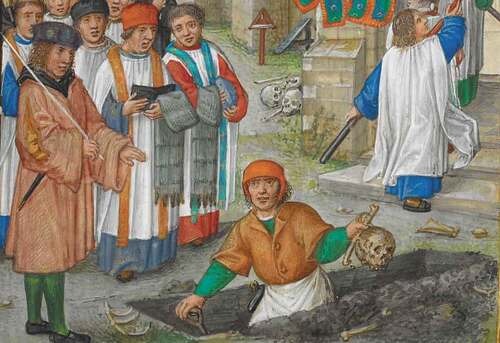

With Holtorf (Citation2015, p. 882) stating that the intended durability of memory is proportionate to the material durability of its memorial, it is inferred that grave marking of the period was undertaken with an intrinsic expectation of timely forgetting. Supporting this, late medieval images of churchyards commonly depict grave markers as wooden crosses bearing eaves with newly dug graves shown surrounded by disturbed charnel, visually associating temporary memorialisation with temporary interment ().

Figure 1. Inhumation amidst upturned charnel, ca. 1420. Hours of the Umfray Family.

Rowlands (Citation1993, p. 144) states that while the raising of memorials represents a ‘material culture of remembering’, materially destructive acts correspond to processes of forgetting. On this basis, late medieval churchyard inhumations can be interpreted as comprising two distinct phases, wherein memory was first recreated and fixed through material construction. The memorial’s subsequent decay or removal, as well as the body’s exhumation and disarticulation, could be characterised as a process of individual forgetting which tied the duration of individualised memorialisation to the duration of individualised mortuary treatment.

Death and memory in late medieval England: communal redeposition

While the transience of graves and markers rendered individual memory materially impermanent, successive interments within landscapes of church and churchyard catalysed social memory through the accumulation of a collective dead (Williams, Citation2003, p. 232). Communal memory, as a shared conception of the past which is malleable and dynamically mediated by the social needs of the present (Tittler, Citation1997, pp. 283–284), was particularly potent in the late medieval period. Within it, notions of individuality were fundamentally orientated around the social context of the supporting collective, with kinship as accessible in social bond as in blood (Tarlow, Citation2010: 120–121; Karant-Nunn, Citation2006, pp. 433–434). This persisted in conceptions of time as well as space, with parish church memorials rarely bearing dates (Mytum, Citation2007, p. 388), suggesting a regard of the community of the deceased as an achronological collective; a singular accumulation of all past souls. This manifested explicitly in charnel assemblages which visibly transcended the social boundaries of relation and time through their lack of individualisation or chronology of remains.

As skeletonisation renders remains unrecognisable as specific individuals, unless biographies are preserved in association (Guerrini, Citation2016: 101–102; Robb, Citation2013, p. 443), their presence in quantity ensured personal anonymity for those deposited there (Ariès, Citation1981, p. 60). Through commingling, individual memory was reinvested both physically and symbolically within a communal memorial assemblage (Marshall, Citation2002: 41; Lambert, Citation2018, p. 30), uniting ‘neighbour and ancestor and stranger alike’ in a ‘newly sanctified … congregation’ (Mullaney, Citation2015, p. 2). Consequently, the charnel house was ‘a destination and an origin’, serving as a material repository of social identity and memory which was both retrospective and prospective (Mullaney, Citation2015: 2; Holtorf, Citation2015, p. 882).

With the continued existence of physical remains necessary in order to facilitate their raising and reunion with associated souls at the time of resurrection (Gragnolati, Citation2000, p. 90), their safeguarding in charnels ensured bodily survival. Disarticulation presented no foil to this end, providing that remains remained on consecrated ground (Musgrave, Citation1997: 65–66; Rugg, Citation2000, p. 265). While disturbed remains had longstandingly been accommodated by communal pit reburial or redeposition via backfill, the church’s 1274 definition of purgatory and establishment of associated chantry practice catalysed the foundation of specific chantry chapels. These sometimes incorporated semi-subterranean chambers for the storage of charnel, becoming specific charnel chapels (Crangle, Citation2016, pp. 151–152). Further to the two-stage model of commemoration/exhumation previously extrapolated from Rowlands (Citation1993), the secondary deposition of remains in charnel structures resituated them within a memorially constructive rather than destructive act. Through their repurposing as components of a charnel assemblage, remains underwent reassociation with communal remembrance via and subsequent to individual forgetting.

Given that notions of the late medieval individual were defined largely by their relational positioning within the living community (Tarlow, Citation2010: 120–121; Karant-Nunn, Citation2006, pp. 433–434), death’s enforcement of individual separation from the collective presented a profound break within social order which required navigation and resolution through ritual practice (Gilchrist & Sloane, Citation2005, p. 18). The tripartite structure of separation, liminality and reincorporation as comprising a rite of passage (Van Gennep, Citation1960) has been applied to late medieval mortuary practices by Gilchrist and Sloane, who outlined preparation of the corpse, burial and commemoration as rituals which guided the remediation of liminality (Gilchrist & Sloane, Citation2005, pp. 18–27). However, post-depositional bodily treatments within English late medieval mortuary practice have not previously been considered as representing a further remediatory stage, though their consideration in broader anthropological literature has been longstanding (i.e. Hertz, Citation1960; Metcalf & Huntington, Citation1991).

It is here suggested that following the separation of death and isolated liminality of individual inhumation, secondary burial via charnel redeposition signified the reincorporation of the deceased individual into the local community. While accumulations of the dead within churchyards have been characterised as socially incorporative through their construction of a collective community of the dead (Williams, Citation2003, p. 230), it is also the case that individual graves simultaneously remain separate microcosms within the macrocosm of the churchyard. In light of this, the redeposition and commingling of skeletal remains in charnels presented an arguably more potent illustration of their reincorporation within a singular community of the collective ancestral dead. Through direct bodily resituation in charnel assemblages which were more permanently situated than individual graves, the individual reattained lasting relational value as a social entity, recreating that which they had held within the community of the living. Having navigated death’s enforced separation from the community as an individual, their communal reincorporation signified a return to place within society.

In this sense, while the forgetting of the deceased as individual might contemporarily be viewed as a rejective process, in its late medieval context it arguably served in an opposite capacity as one of incorporative remediation, signifying a reattainment of social normativity. Through its forgetting, individual memory was reforged within the construction of communal memory (Williams, Citation2003, p. 232). The visibility of remains in charnels ensured public knowledge of this reincorporation, with windows ensuring their illumination (Crangle, Citation2016, p. 173).

In analysing the primary burial process, Schwyzer (Citation2007, p. 122) states that the grave acted simultaneously as a device of remembrance and forgetting which was achieved through the perpetuation of an individual’s memory while withholding knowledge of them – where the act of knowing is interpreted as a process which is specifically mediated by the body. On this basis, a distinction between ‘living memory’ and ‘living knowledge’ can be advanced, with the charnel house reversing the function of an individual grave by perpetuating material knowledge of the dead at the expense of their individual memorialisation.

With visual exposure to ancestral remains constituting material knowledge, the duration of their affective power was freed from the limitations of living memory and reinvested within communal heritage. On this basis, the assembling of human remains in charnels represented not only the individual’s return to communally engaged positioning within local memorial and devotional landscapes, but also contributed towards the cumulative construction of a material ancestral text in a context where literacy was scarce (Alderman & Dwyer, Citation2009, p. 53).

Messages of community, continuity and resurrection (for which the remains were waiting, prepared and expectant) were visually conveyed, akin to the utilisation of mediums such as murals to effect silent preaching (Gill, Citation2002; C. Burgess, Citation2000, p. 47). In this respect, the utilisation of charnel as an iconographic device represents an authoritatively mediated representation of communal memory, employing the past as a tool to legitimise the social order of the present (Alderman & Dwyer, Citation2009, p. 51). Furthermore, charnels facilitated ongoing social cohesion among the living, who remained united by a central assemblage which reflected a shared past and identity (Gibbons, Citation2012, p. 17).

Charnelling in late medieval England

The distribution of charnel structures in late medieval England is a matter of ongoing investigation, with only two examples (Holy Trinity, Rothwell and St. Leonard’s, Hythe) presently extant and accessible (Crangle, Citation2016, p. 193). Following Gilchrist and Sloane’s acknowledgement of the inconsistency of available data (Gilchrist & Sloane, Citation2005, p. 42), Dr. Jennifer Crangle proposed a list of 48 qualifying sites (Crangle, Citation2016) with further augmentation following in 2019 (Craig-Atkins et al., Citation2019). Significantly, these studies evidence the presence of charnel structures in both monastic and parish contexts, with their localised rather than exclusively monastic occurrence suggesting a potentially wide presence. However, confirmatory research regarding their distribution is ongoing (see Farrow, Citation2020).

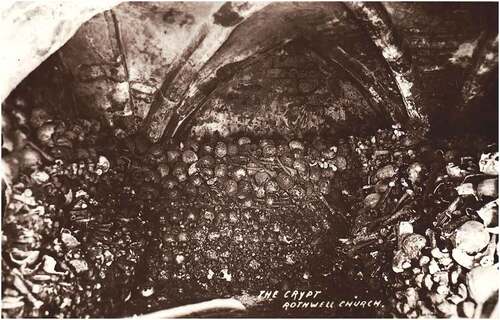

Crangle identified two predominant architectural forms of late medieval English charnel chapel. Within monastic complexes, freestanding two-storey structures accommodating a chantry chapel above a semi-subterranean charnel chamber predominated, while parish examples consisted of chambers beneath churches which housed both charnel assemblages and chantry activities (Crangle, Citation2016, pp. 171–173). In both instances, the incorporation of windows ensured visibility of remains, while in parish examples, the presence of piscinas, murals and access paths generated by stacking remains against walls support the hypothesis of their simultaneous use as charnel crypts and chantry chapels () (Crangle, Citation2016: 191, 198, 220).

Figure 2. Medieval configuration of the charnel crypt at Holy Trinity, Rothwell, prior to restacking in 1912. Bones stacked against walls created central space, while fresco remnants are visible on the rear wall. Unpublished photograph. Author’s Collection.

While charnel chapels in parish contexts affirmed shared communal identity and social cohesion on a local level, Harding noted a concentration of seven examples in London (Harding, Citation1995, p. 134), the largest of which was associated with St. Paul’s Cathedral (Houlbrooke, Citation2000, p. 332). While their increased presence in the metropolis was a practical reflection of the city’s higher population density in relation to available burial space, their social and authoritative significance was multiplied in proportion. In association with the capital’s cathedral, the charnel at St. Paul’s legitimised authority on a national level. As its administration involved both the city government and cathedral community, it furthermore affirmed the interrelation of civic and ecclesiastical powers within the late medieval period (Rousseau, Citation2011, p. 75). This positioning led to a state of heightened significance which was reflected in the arguably extreme character of its treatment following the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

St. Paul’s cathedral, London: Pardon Churchyard

The medieval burying ground of St. Paul’s Cathedral, known as ‘Pardon Churchyard’ or ‘Haugh’, was situated to the cathedral’s North and extended much further than it does at present (Holmes, Citation1896, p. 56). First named in 1301 as ‘le Pardoncherchawe’ (Harben, Citation1918), its providence of pardon rendered it an attractive place for the burial of those who had not received final absolution, including plague victims (Appleford, Citation2014). Pardon was consequently a burial place without particular social esteem, with late medieval accounts including complaints about individuals falling into open graves as well as overcrowding and stench (Wall, Citation2017: 4; Dabbs, Citation2013, p. 46).

In the early fifteenth century, however, Pardon was enclosed by a large cloister, the wall of which was adorned with a ‘Dance of Death’ fresco modelled after that at the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris (Marshall, Citation2002, p. 107). This material investment and implied exclusivity of space led to Pardon Churchyard gaining increased status through the fifteenth century, further reflected in the tailoring of figures in the fresco to characters reflecting London’s higher social classes (Appleford, Citation2014). The cloister was subsequently described as having housed persons of worship and honour, containing memorials which surpassed those of the cathedral in quality (Stow, Citation1633, p. 354).

The cumulative stages of fifteenth century gentrification exhibit the continuing privilege of permanent individual memorialisation in association with individuals of high status, indicated by finely crafted memorials. However, the limited available burial space in relation to the high demand for burial in Pardon ensured that the exhumation of older burials remained an essential practice, rendering the charnel of St. Paul’s an omnipresent feature in the cathedral’s complex.

The charnel chapel of St. Paul’s cathedral

Having accommodated burials since the early seventh century, grave clearance was a necessity of Pardon’s continued function (Besant, Citation1894, pp. 92–93). While a charnel structure had existed on-site since the twelfth century, a private chantry chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary was appended to it in the 1270s (Rousseau, Citation2011: 75; Harben, Citation1918aa). In 1282, this chapel was incorporated into the common charnel with funds for its institution raised by shops adjoining the churchyard () (Stow, Citation1633: 356; Harben, Citation1918), and from 1302 onward was made open to pilgrims on Fridays and specified feast days (Rousseau, Citation2011, p. 75).

Figure 3. Plan of the precinct of the old St. Paul’s Cathedral, showing the charnel house’s location to the North West.

Specific requests for burial within the charnel in wills of the mid-late fifteenth century (Sharpe, Citation1890: 473–479; James & Jones, Citation2004, pp. 26–47) suggest an acquired status subsequent to the gentrification of Pardon, with the contained remains ‘decently piled together’ and treated ‘with great respect and care’ (Dugdale, Citation1658, p. 126). However, theological reform consequent to the Dissolution of the Monasteries undermined this standing by rendering charnel chapels as incongruous and offensive remnants of repudiated purgatorial doctrine (Walsham, Citation2012, p. 97).

While first planned in 1545, the dissolution of chantry institutions was delayed owing to the death of Henry VIII (Morgan, Citation1999, p. 142). However, in December 1547 the first parliament of Edward VI instructed that chantries were to be abolished and their properties surrendered to the crown (Houlbrooke, Citation2000, p. 117). The enforcement was sudden and effective immediately, with many chantries operating in no diminished capacity until the eve of their formal dissolution (Woodward, Citation1982: vii). Upon this surrender, the properties were inventoried, and their assets surveyed in preparation for private sale (Kitching, Citation1980; Woodward, Citation1982), with subsequent treatments of chantry structures in private hands varying greatly.

While some were demolished or left to ruin, some became private memorial chapels for wealthy families. Others were repurposed civically, serving as domestic dwellings, storehouses or even stables (Roffey, Citation2017, pp. 169–173). A number of examples, such as the extant structures at Norwich Cathedral and Kingston upon Thames, were repurposed as grammar schools with royal dedications (Gilchrist, Citation2006: 102–103; Ward & Evans, Citation2000). Remaining consistent throughout was the enforcement of a newfound state of deconsecration, achievable equally through material destruction or by lasting reassociation with secular commercial or civic functions (Walsham, Citation2012: 101; Gibbons, Citation2012, p. 16).

Where chantries accommodated charnel chambers, clearance of their contained remains facilitated the repurposing of structures (Curl, Citation1980, p. 136). With holy remains as relics having been characterised as idolatrous by Protestant reformers since the 1530s, notions of direct and ongoing relationships between the individual’s spiritual and bodily remains had been consistently challenged by the time of the Dissolution (Walsham, Citation2010, pp. 121–123). By extension and further to the rejection of purgatory, the curation of lay remains in charnel chapels was of no spiritual consequence within the new regime.

The unceremonious listing of St. Paul’s charnel as ‘charnel chapel and shed’ in the inventory of 1548 (Kitching, Citation1980, p. 59) effected administrative desanctification by refusing its recognition as a site of any elevated significance. The cloister of St. Paul’s was subsequently acquired by the Duke of Somerset, who had been personally involved in arranging and executing Edwardian reform, and who set about razing the landscape in order to recover building materials and ready the land for redevelopment (Morgan, Citation1999, p. 143).

The demolition of structures within Pardon Churchyard commenced on 10 April 1549 ‘so that nothing of them was left but the bare plot of ground’ (Weever, Citation1631, pp. 378–379). Recovered material was repurposed in the construction of the Duke’s new residence in the Strand (Noorthouck, Citation1773: 122–130; Thornbury, Citation1878: 89–95; Besant, Citation1894, pp. 92–93), actively affirming ideological reform through the repurposing of sacred material as secular material. With the destruction of the cloister came also the destruction of memorials held there (Noorthouck, Citation1773, pp. 122–130), which was carried out irrespective of status and included the alabaster memorials of a knight and two former mayors of London (Weever, Citation1631, pp. 378–379). Stow (Citation1633: 356) described how the charnel’s bones were removed and dumped at Finsbury Fields, amounting to ‘more than one thousand cart loads’, while the contemporary Greyfriars’ Chronicle offers an alternative estimate of four to five hundred cart loads (Nichols, Citation1852, p. 57). The remains were shortly thereafter covered over by ‘soylage of the citie’, forming such a mound that three windmills (later six) were erected on the site to take advantage of the raised terrain (Stow, Citation1633: 356; Buckland, Citation1988).

While records of popular feeling are notably absent from 16th century accounts of the clearance (i.e. Stow, Citation1633; Nichols, Citation1852, p. 57), perhaps indicating an unwillingness to publish what could have been interpreted as criticism of reform, Somerset’s actions are retrospectively reported to have been poorly received by both Catholic and Protestant communities. In 1643, the chronicler Sir Richard Baker stated that Somerset’s act ‘did something [to] alienate the people’s minds from him’ (Baker, Citation1670, p. 305), while the antiquary Samuel Pegge later reported that while Catholic reactions were inevitably unfavourable, Protestants who did not object to iconoclastic destruction still took offence to the bodies of friends being irreverently exhumed and their remains dumped on unconsecrated ground (Pegge, Citation1806, pp. 48–49). Later during the 19th century, the act was characterised as ‘unblessed by the church or the people or the poor’ (Thornbury, Citation1878, pp. 89–95).

The property was divided, with plots bought up predominantly by individuals in the growing printing industry, establishing St. Paul’s precinct as the centre of the English book trade in the late sixteenth century (Maguire, Citation2012). While some later accounts assert that the charnel structure was pulled down during the levelling of the churchyard (i.e. Dugdale, Citation1658, p. 130), Stow’s eyewitness account specifically states that while all else in the precinct was levelled, ‘the Chapell and Charnell were converted into dwelling houses, ware-houses and sheds before them, for Stationers in place of the Tombes’ (1633: 356).

The charnel structure was purchased by the stationer Reyner Wolfe, who oversaw the removal of the bones so that the property could be repurposed as retail premises (Kisery, Citation2012, p. 373). Though the building was renamed the ‘Black Bear’, a 1638 lease notes that it was ‘sometimes called the Charnell howse’ (Blayney, Citation1990, p. 23) indicating that awareness of its original purpose persisted through oral history. At a time when the posthumous works of poets were often marketed as ‘remains’, amidst an established literary association of corpse with corpus (Kerrigan, Citation2013, p. 240), the sale of such works from the property became something of a macabre in-joke within the precinct (Kisery, Citation2012, p. 373).

Owing to Somerset’s personal involvement in arranging Edwardian reform (Morgan, Citation1999, p. 143), the charnel’s clearance can be interpreted as reflecting attitudes of the crown. Wolfe also bore royal connection, having received appointment as printer to the King for works in Latin, Greek and Hebrew in 1547 (Raven, Citation2007, p. 31). Consequently, his purchase of the charnel from Somerset was a matter of mutual convenience, being economically beneficial to both men while simultaneously supportive of royal patronage and reformed ideology. This connection may also help to account for the discrepancy between contemporary estimates of the volume of remains removed from the charnel, with Wolfe’s self-reported account of a thousand cart loads of bones being approximately double that given in the Greyfriars’ Chronicle. Owing to royal Protestant allegiances, Wolfe may have felt encouraged to maximise his role, while the Catholic Greyfriars may have felt motivated to minimise the disturbance. The scale remains large either way, with Wolfe’s business motivation affirming the efficacy of private enterprise as a mechanism of desanctification.

St. Paul’s charnel in the landscape: pre-dissolution

The charnel’s location within the cathedral complex positioned it in sight of Paul’s Cross, rendering it the backdrop for numerous social functions, gatherings and events (). Paul’s Cross had existed on-site since at least the thirteenth century (Stpauls.co.uk, Citation2020), hosting the announcement of royal proclamations and papal bulls (Kirby & Stanwood, Citation2014, p. 1) as well as judicial events such as the punishment of heretics and their penitent acts (Kingsford, Citation1910: 1–17; Northbrooke, Citation1571: VIII–IX). Furthermore, its function as the traditional site of the folkmoot and as a place of protest and grievance imbued it with the status of a people’s space (Kirby & Stanwood, Citation2014, p. 1).

Figure 4. Late nineteenth century interpretation of the medieval cathedral. Paul’s Cross (centre) is shown relative to the charnel (right).

This cultural significance rendered it central to ongoing navigations of changing urban identities throughout the dissolution (Azevedo et al., Citation2013), hosting both public renunciations by Catholic preachers in the 1540s and proclamations of new unity with Rome following acts of repeal in the 1550s (Beer, Citation1985: 262, p. 267). In the late medieval period, however, it most significantly served as a place of preaching, which frequently occurred outside rather than within churches in accommodation of increasingly large audiences (Carlson, Citation2003, p. 253).

Through its visibility from Paul’s Cross, the charnel situated the events of the present in continuity of the past through the close physical proximity of the collective ancestral dead. Furthermore, their affective presence as human remains harnessed imagery of mortality in legitimisation of the church as a socially controlling body, emphasising its power by employing memory as a tool to legitimise the order of the present (Alderman & Dwyer, Citation2009, p. 51).

St. Paul’s charnel in the landscape: post-dissolution

The sixteenth century saw substantial changes in the carriage and employment of memory, with social and mnemonic practices coming to be perceived as subjective and fallible by comparison to the objectifiable and empirical qualities of print (Sherlock, Citation2010). Alongside this broad cultural change, the rejection of Catholic purgatorial belief significantly redefined English relationships between memory and the dead. With the redundancy of intercessory prayer came the violent ejection of material culture associated with its exhortation, as with reformers noting the profound influence of the visual over ordinary people, it was considered necessary to manifest change materially in order to render it real (Perham, Citation1980, p. 51). Consequently, widespread iconoclasm, the abolition of chantries and the destruction of their associated charnels (Crangle, Citation2016: 209; Orme, Citation1996, p. 102) channelled reformatory zeal toward the historic dead as material signifiers of purgatorial belief (Marshall, Citation2002, p. 107).

While most charnels underwent clearance prior to demolition or repurposing during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Curl, Citation1980: 136; Roffey, Citation2017: 171; Litten, Citation2002, p. 8), churchyard overcrowding in the metropolis remained an issue. Houlbrooke (Citation2000, p. 335) describes the continued employment of charnel pits in London but states that remains were treated with little respect. In 1616, for example, John Aubrey described regular rounds of exhumation, with remains removed to the ‘dung-wharf’ for reuse as fertiliser (Houlbrooke, Citation2000, p. 335). Where structures remained in use, they were stripped of religious connotation (Taylor, Citation1821: xvi; Houlbrooke, Citation2000, p. 333), with church accounts referring to ‘bonehouses’ rather than charnels (i.e. Gittings, Citation1984, p. 139). The practice was thus disassociated from its prior Catholic nomenclature, emphasising functionality through pragmatic connotation.

While the emptying of charnels was common, the treatment afforded at St. Paul’s constituted the dissolution’s largest single disturbance of remains and monuments (Marshall, Citation2002, p. 107) and should be regarded as exceptional in its extremity. Further to a rejection of memory, the treatment represented its active degradation (Mullaney, Citation2015, p. 1). With deposition in unconsecrated ground being the single most extreme injury of remains occasionable in the period (Schwyzer, Citation2007, p. 121), their subsequent covering by the city’s ‘soylage’ added insult by equating the dead to literal excrement owing to their status as purgatorial signifiers.

The physical remains of the ancestral dead, as a repository of communal folk memory, were repositioned from a central location within a landscape of living community to a peripheral space of wastage beyond city walls, thereby marked as beyond the purview of the living. In this way, cultural and ideological changes were made physically manifest through the effecting of change in the built environment (Kisery, Citation2012, p. 373), with reformation of the physical memorial landscape reflecting reformation of sociocultural landscapes of memory, ideology and identity.

Further to spatial relocation, the translation of remains from orderly curated stacks to an exposed and jumbled mass further compounded contemporary disregard through the public nature of its extreme visual illustration. Just as charnel structures had employed the orderly display of remains to silently preach purgatory, their translation to a state of disorder repurposed the material of message, subverting established iconography so that it instead preached reformation. The act thus constituted a plain material assertion that the ancestral past was of zero value in the radical reshaping of the present, wherein the traditional norms of memory were being rewritten by the actions of an elite engaged in the construction and legitimisation of a new social order via the redefinition of spiritual and physical landscapes of identity, power and normativity (Alderman & Dwyer, Citation2009).

A legacy in landscape: Bunhill fields

The site of redeposition retained affective presence in the landscape through its naming, with the area’s modern designation ‘Bunhill’ deriving from the earlier ‘Bone Hill’, referring to a literal hill comprised human bones (Garrard & Parham, Citation2011; Weil, Citation1992, p. 77). That the redistribution of remains from a centralised to peripheral landscape effected profound changes in terrain indicates the physical as well as symbolic scale of the act, further affirmed by the construction of windmills on the hill in the 1550s, capitalising immediately on the raised land (Buckland, Citation1988).

While the dumping of remains at Finsbury Fields is most plainly interpretable as a counter-memorial act, its effecting of change in the landscape simultaneously produced a memorial to the dissolution itself. While Catholic traces were frequently removed from physical landscapes during the period, it was sometimes considered more potent to retain them in a ruined state. In this way, the stumps of beheaded crosses and the ruins of abbeys and chapels served a revised purpose as monuments to the successes of reform, symbolising the overcoming of papal influence through the physical depiction of its ruin (Walsham, Citation2012, pp. 147–148). On this basis, the bone hill at Finsbury Fields would have offered testament to the physical discarding of papal superstition, being further compounded through the siting of windmills upon it. In the same way that the material remains of sacred architecture underwent deconsecration through secular repurposing, the material human remains of purgatorial belief became literal foundations for civic industry. In a reversal of chantry economics, the bones now served in financial support of the living, not the dead.

Following the initial deposition of remains from St. Paul’s charnel, the site was further augmented through Elizabethan charnel clearances while additionally serving as a place of burial for heretics (Curl, Citation1980: 136; Holmes, Citation1896, p. 134), emphasising its marginal perception. In the seventeenth century, plague led to Bunhill’s proposal as an emergency burial ground and its enclosure by the City in 1665 (Lacquer, Citation2015, p. 119). However, this purpose was not fulfilled, with the site instead functioning as a dissenter’s burial ground from the late seventeenth century on (Weil, Citation1992, p. 77).

Bunhill’s popular status in decades following its enclosure is attested by publications detailing its inscriptions (i.e. Curll, Citation1717), evidencing that its use fell in line with the period’s broader trends towards permanent individual rather than communal or temporary memorialisation. Bunhill was administered by the City until the Common Council took over its lease in 1778 and managed the site until 1855, before it was acquired by the Corporation of London in 1866 who ceased its use as a burial ground and repurposed it as a public park (Lacquer, Citation2015, p. 300). Notably, the site does not feature any memorials to the initial deposition of remains which formed its foundation, and the nominal corruption of ‘Bone Hill’ to the more pleasant ‘Bunhill’ illustrates a process of reincorporation into a broader landscape of the living.

While an awareness of the original purpose of the charnel structure at St Paul’s is known to have persisted for at least a century in spite of its rebranding as the ‘Black Bear’ (Blayney, Citation1990, p. 23), the precinct’s destruction in the Great Fire of 1666 and consequent redevelopment removed all visible traces of the structure from the metropolitan landscape. With this, the last remaining material prompt for continued social awareness of the prior charnel of St. Paul’s was erased. The nominal shift of ‘Bone Hill’ to ‘Bunhill’ also appears to have occurred following the fire, as while mid-17th century sources refer to the area as ‘Bone Hill’ or ‘Finsbury Fields’, by the early eighteenth century the term Bunhill was predominant (Curll, Citation1717).

Conclusion

Following exploration of temporary inhumation and grave marking in late medieval English churchyards, the social and memorial implications of exhumation and secondary burial in charnel assemblages were interpreted as representing a rite of passage. The physical redeposition of individual remains into communal charnel assemblages anonymised the deceased, reinvesting the individual’s material remains within communal memorial assemblages. Following death’s enforced separation of the individual from the community, collective redeposition represented the dead’s return to place within late medieval society.

While the distribution of charnelling in late medieval England is a matter of ongoing investigation, it occurred in both parish and monastic contexts. Within London, the charnel of St. Paul’s Cathedral was the largest of seven known examples, taking on national significance through its accommodation of a communal memorial assemblage within a space which had longstandingly served as a point of central significance throughout ongoing navigations of social and cultural identity. Consequently, throughout the process of Edwardian reform following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the precinct’s charnel was the subject of singularly extreme treatment on account of its significance and status.

Owing to their status as signifiers of Catholic purgatorial belief, the communal ancestral dead within charnels became targets of reformatory zeal, with chantry institutions desanctified through their private sale and clearance. The charnel structure of St. Paul’s underwent desanctification through its repurposing as commercial premises, while the unceremonious clearance and relocation of its contained remains effected substantial change within the landscape at Finsbury Fields. The hill of dumped human bones served as an explicit visible memorial to ideological change and religious reform which was preserved physically in the landscape. Beyond the duration of its physical monumentality, reference to the site’s 16th century function has been retained nominally to this day.

With the investigation of charnelling in late medieval England being an area of ongoing investigation, much remains to be explored. However, in providing the first dedicated study of the country’s largest example, the present paper has sought to provide an account which might serve as a key point of reference within future work. Furthermore, the paper has offered theoretical discussion of late medieval burial and exhumation in relation to individual and collective memory, while also exploring the social significance and function of charnelling. The practice was situated within broader literatures of secondary burial through its interpretation as a rite of passage, with further exploration along these lines holding potential for future theoretical advancement.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Professor Howard Williams for his comments and suggestions on an early version of this paper, and for his encouragement and support of its development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas J. Farrow

Tom Farrow holds an MA in the Archaeology of Death and Memory from the University of Chester, UK. His interests include the post-depositional curation and display of human remains in charnel assemblages, as well as affective components of interaction with exhumed skeletal material.

References

- Alderman, D. H., & Dwyer, O. J. (2009). Memorials and monuments. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (Vol. 7, pp. 51–58). Elsevier.

- Appleford, A. (2014). Learning to die in London, 1380–1450. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Ariès, P. (1981). The hour of our death. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Azevedo, M., Markham, B., & Wall, J. N. (2013). Acoustical archaeology - Recreating the soundscape of John Donne’s 1622 gunpowder plot sermon at Paul’s cross. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, 19(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4799054

- Badham, S. (2014). Commemoration of the dead in the late medieval English Parish: An overview. Church Archaeology, 16(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.5284/1081961

- Baker, R. (1670). A chronicle of the kings of England. George Sawbridge.

- Beer, B. L. (1985). John Stow and the English reformation, 1547–1559. The Sixteenth Century Journal, 16(2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.2307/2540915

- Besant, W. (1894). The history of London. Longmans, Green and Co.

- Blayney, P. W. M. (1990). The bookshops in Paul’s cross churchyard. The Bibliographical Society.

- Buckland, J. S. P. (1988). Technical notes on 16th and 17th century London windmills. Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 60(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1179/tns.1988.008

- Burgess, C. (2000). ‘Longing to be prayed for’: Death and commemoration in an English Parish in the later Middle Ages. In B. Gordon & P. Marshall (Eds.), The place of the dead: Death and remembrance in late medieval and early modern Europe (pp. 44–65). Cambridge University Press.

- Burgess, F. (1979). English churchyard memorials. SPCK.

- Carlson, E. J. (2003). The boring of the ear: Shaping the pastoral vision of preaching in England, 1540–1640. In L. Taylor (Ed.), Preachers and people in the reformations and early modern period (pp. 249–297). Brill.

- Craig-Atkins, E., Crangle, J., Barnwell, P. S., Hadley, D. M., Adams, A. T., Atkins, A., McGinn, J. R., & James, A. (2019). Charnel practices in Medieval England: New perspectives. Mortality, 24(2), 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2019.1585782

- Crangle, J. N. (2016) A study of post-depositional funerary practices in Medieval England. PHD Thesis. University of Sheffield. Online. Accessed 28. 3.20: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/13315/

- Curl, J. S. (1980). A celebration of death: an introduction to some of the buildings, monuments and settings of funerary architecture in the Western European tradition. Constable.

- Curll, E. (1717). The inscriptions upon the tombs, grave-stones, &c. in the dissenters burial place near Bunhill-fields. E. Curll.

- Dabbs, T. W. (2013). Paul’s cross churchyard and shakespeare’s Verona Youth. In A. Shifflett & E. Gieskes (Eds.), Renaissance papers 2012 (pp. 41–52). Camden House.

- Daileader, P. (2019) How Europe’s population in the Middle Ages doubled.The Great Courses Daily [Online] Accessed 19. 2.20 https://www.thegreatcoursesdaily.com/how-europes-population-in-the-middle-ages-doubled/

- Davis, N. Z. (1977). Ghosts, kin and progeny: Some features of family life in early modern France. Daedalus, 106(2), 87–114. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20024478

- Dugdale, W. (1658). The history of St Pauls cathedral in London. Thomas Warren.

- Farrow, T. J. (2020) Dry bones live: A brief history of English charnel houses, 1300–1900AD. EPOCH 1. Online. Accessed 24. 11.20: https://www.epoch-magazine.com/farrowdryboneslive

- Finch, J. (2003). A reformation of meaning: Commemoration and remembering the dead in the Parish church, 1450–1640. In D. M. Gaimster & R. Gilchrist (Eds.), The archaeology of reformation 1480–1580 (pp. 437–449). Routledge

- Garrard, D., & Parham, H. (2011). Listing Bunhill fields: A descent into dissent. Conservation Bulletin, 66(1), 18–20 https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-bulletin-66/cb-66/

- Gibbons, D. R. (2012). Rewriting spiritual community in Spenser, Donne and the ‘Book of Common Prayer’. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 54(1), 8–44. https://doi.org/10.7560/TSLL54102

- Gilchrist, R. (2006). Norwich Cathedral close: The evolution of the English cathedral landscape. The Boydell Press.

- Gilchrist, R., & Sloane, B. (2005). Requiem: The medieval monastic cemetery in Britain. Museum of London Archaeology Service.

- Gill, M. (2002). Preaching and image: Sermons and wall paintings in later Medieval England. In C. A. Muessig (Ed.), Preacher, sermon and audience in the Middle Ages (pp. 155–180). Brill.

- Gittings, C. (1984). Death, burial and the individual in early modern England. Croom Helm.

- Gordon, B. (2015). The living and the dead. In P. Marshall (Ed.), The Oxford illustrated handbook of the reformation (pp. 32–41). Oxford University Press.

- Gragnolati, M. (2000). From decay to splendor: Body and pain in Bonvesin da la Riva’s book of the three scriptures. In C. W. Bynum & P. Freedman (Eds.), Last things: Death and the Apocalypse in the Middle Ages (pp. 83–100). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Guerrini, A. (2016). Inside the Charnel house: The display of skeletons in Europe, 1500-1800. In R. Knoeff & R. Zwijneberg (Eds.), The fate of anatomical collections (pp. 93–112). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Harben, H. A. (1918). Patrick’s court, Houndsditch - Paul’s (St.) Prebends. In H. A. Harben (Ed.), A dictionary of London. H. Jenkins Ltd. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/dictionary-of-london/patricks-court-pauls-prebends#h2-0020

- Harben, H. A. (1918a). Chapel of Bethlehem - charterhouse rents. In H. A. Harben (Ed.), A dictionary of London. H. Jenkins Ltd. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/dictionary-of-london/chapel-of-bethlehem-charterhouse-rents#h2-0006

- Harding, V. (1995). Burial choice and burial location in later medieval London. In S. Basset (Ed.), Death in towns: Urban responses to the dying and the dead, 100-600 (pp. 119–135). Leicester University Press.

- Härke, H. (2002). Interdisciplinarity and the archaeological study of death. Mortality, 7(3), 340–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357627021000025487

- Hertz, R. (1960). A contribution to the study of the collective representation of death. In R. Needham & C. Needham (Eds.), Death and the right hand (pp. 29–88). The Free Press.

- Holmes, B. (1896). The London burial grounds: Notes on their history from the earliest times to the present day. Macmillan And Co.

- Holtorf, C. (2015). Archaeology and cultural memory. In K. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioural sciences (Second ed., pp. 881–884). Elsevier.

- Houlbrooke, R. (2000). Death, religion and the family in England 1480–1750. Clarendon Press.

- James, N. W., & Jones, V. A. (2004). The bede roll of the fraternity of St Nicholas. London Record Society.

- Karant-Nunn, S. C. (2006). Reformation society, women and the family. In A. Pettegree (Ed.), The reformation world (pp. 433–460). Routledge.

- Kerrigan, J. (2013). Shakespeare, elegy and epitaph 1557–1640. In J. Post (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Shakespeare’s poetry (pp. 225–244). University Press.

- Kingsford, C. L. (ed.). (1910). Two chronicles from the collections of John Stow. Camden Society.

- Kirby, T., & Stanwood, P. G. (2014). Introduction. In T. Kirby & P. G. Stanwood (Eds.), Paul’s cross and the culture of persuasion in England, 1520-1640 (pp. 1–19). Leiden.

- Kisery, A. (2012). An author and a bookshop: Publishing Marlowe’s remains at the Black Bear. Philological Quarterly, 19(3), 361–392. http://real.mtak.hu/34922/

- Kitching, C. J. (ed.). (1980). London and Middlesex chantry certificate. London Record Society.

- Lacquer, T. (2015). The work of the dead. Princeton University Press.

- Lambert, E. M. (2018). Singing the resurrection: Body, community and belief in reformation Europe. Oxord University Press.

- Lees, H. (2002). Exploring English churchyard memorials. Tempus.

- Litten, J. (2002). The English way of death. Robert Hale.

- Maguire, L. E. (2012). The craft of printing (1600). In D. S. Kastan (Ed.), A companion to Shakespeare (pp. 434–449). Blackwell.

- Marshall, P. (2002). Beliefs and the dead in reformation England. Oxford University Press.

- Metcalf, P., & Huntington, T. (1991). Celebrations of death: The anthropology of mortuary ritual (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, P. (1999). Of worms and war: 1380–1558. In P. C. Jupp & C. Gittings (Eds.), Death in England: An illustrated history (pp. 119–146). Manchester University Press.

- Mullaney, S. (2015). The reformation of emotions in the age of Shakespeare. University of Chicago Press.

- Musgrave, E. (1997). Memento Mori: The function and meaning of breton ossuaries 1450–1750. In P. C. Jupp & G. Howarth (Eds.), The changing face of death (pp. 62–75). Macmillan Press Ltd.

- Mytum, H. (2007). Materiality and memory: An archaeological perspective on the popular adoption of linear time in Britain. Antiquity, 81(312), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00095259

- Nichols, J. G. (ed.). (1852). Chronicle of the grey friars of London. J.B. Nichols and Son.

- Noorthouck, J. (1773). A new history of London including Westminster and Southwark. R. Baldwin.

- Northbrooke, J. (1571). Spiritus est Vicarius Christi in Terra. John Kingston.

- Orme, N. (1996). Church and chaple in Medieval England. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 6(1), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.2307/3679230

- Pegge, S. (1806). Curialia, or an historical account of some branches of the Royal Household &c &c, Parts IV and V. J. Nichols and Son.

- Perham, M. (1980). The communion of saints. SPCK.

- Raven, J. (2007). The business of books: Booksellers and the English book trade 1450–1850. Yale University Press.

- Robb, J. (2013). Creating death: An archaeology of dying. In S. Tarlow & L. Nilsson Stutz (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the archaeology of death and burial (pp. 441–458). Oxford University Press.

- Roffey, S. (2017). Chantry chapels and medieval strategies for the afterlife. Gloucestershire: The History Press.

- Rousseau, M.-H. (2011). Saving the souls of medieval London: Perpetual chantries at St Paul’s. Ashgate Publishing.

- Rowlands, M. (1993). The role of memory in the transmission of culture. World Archaeology, 25(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1993.9980234

- Rugg, J. (2000). Defining the place of burial: What makes a cemetery a cemetery? Mortality, 5(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/713686011

- Schwyzer, P. (2007). Archaeologies of English renaissance literature. University Press.

- Sharpe, R. R. (ed.). (1890). Calendar of wills proved and enrolled in the court of husting, London: Part 2, 1358-1688. HMSO.

- Sherlock, P. (2010). The reformation of memory in early modern Europe. In S. Radstone & B. Schwarz (Eds.), Memory: Histories, theories, debates (pp. 30–40). Fordham University Press.

- Stow, J. (1633). The survey of London. Elizabeth Purslow.

- Stpauls.co.uk (2020) Paul’s cross in the reformation. St Paul's Cathedral History & Collections [ Online] Accessed 28. 4.20: https://www.stpauls.co.uk/history-collections/history/reformation500/pauls-cross-in-the-reformation

- Tarlow, S. (2010). Ritual, belief and the dead in early modern Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, R. (1821). Index monasticus. Richard and Arthur Taylor.

- Thornbury, W. (1878). Old and New London (Vol. 3). Cassell, Petter & Galpin.

- Tittler, R. (1997). Reformation, civic culture and collective memory in English provincial towns. Urban History, 24(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926800012360

- Van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Wall, J. N. (2017). The contested pliability of sacred space in St Paul’s cathedral and Paul’s churchyard in early modern London. In J. Pearce & W. J. Risvold (Eds.), Renaissance papers 2017: The Southeastern Renaissance Conference (pp. 1–16). Camden House.

- Walsham, A. (2010). Skeletons in the cupboard: Relics after the English reformation. Past & Present Supplement, 206(Suppl. 5), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtq015

- Walsham, A. (2012). The reformation of the landscape: Religion, identity and memory in early modern Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press.

- Ward, D. W., & Evans, G. W. (2000). Chantry chapel to Royal Grammar School: The history of Kingston Grammar School 1299-1999. Gresham Books.

- Weever, J. (1631). Ancient funerall monuments within the united monarchie of Great Britaine, Ireland, and the Islands adjacent. Thomas Harper.

- Weil, T. (1992). The cemetery book. Barnes & Noble.

- Williams, H. (2003). Remembering and forgetting the medieval dead. In H. Williams (Ed.), Archaeologies of remembrance: Death and memory in past societies (pp. 227–254). Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

- Woodward, G. H. (ed.). (1982). Calendar of Somerset chantry grants, 1548–1603. Somerset Record Society.