ABSTRACT

Care after the death of a child and support of their bereaved family is an important element of the services offered by children’s hospices in the United Kingdom. The study aims to explore the emotional challenges of those delivering care to families of children in hospice cool rooms. An internet-based questionnaire was sent to all practitioners to explore their perspectives of providing care to bereaved families whilst the child’s body was in the hospice, as well as caring for a child’s body after death. In total, 94.9% (n = 56) of staff responded. Two key themes were identified that represent the emotional challenges perceived by staff: the impact of deterioration of a child’s body; and witnessing the acute grief of families. Practitioners seek to provide care that recognises the importance of family and demonstrates family-centred care, as well as supporting families to deal with the changes that occur after death. Organisations can support practitioners to deliver care in cool rooms by providing training and education on anticipating and managing the pathophysiological changes that occur after death as well as training in grief and loss, and how to support a bereaved family.

There are more than 86,000 babies, children and young people (hereafter children) living with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions in the UK (Fraser et al., Citation2020). There are 54 children’s hospices that provide a range of palliative care services for these children and their families, in hospice buildings or community settings, such as family homes (Widdas et al., Citation2013). The term ‘palliative care’ is often misunderstood to include only care during dying, but as shown in the definition by Together for Short Lives (Chambers, Citation2018) in , the term describes an active and total approach to care and includes care after death.

Figure 1. Definition of children’s palliative care (Chambers, Citation2018, p. 9).

This paper focuses on the care offered to families immediately after the death of their child, in children’s hospice cool rooms: specially designed rooms that allow the bodies of deceased children to be cared for (Forrester, Citation2008). Care of the child’s body includes managing any physical post-mortem deterioration, as well as supporting the child’s family in washing and dressing the body, meeting any religious or spiritual needs and creating memory-making artefacts, including hand and footprints, hand casts and photography. For some families, this can also include supporting tissue donation (Sque et al., Citation2018). The length of time bodies can stay in hospices varies between organisations, however one constant is the delivery of care that is family centred.

Family-centred care is described as ‘a cornerstone of children and young people’s nursing in the UK’ (Tatterton & Walshe, Citation2019b, p. 110), widely recognised as an important component of neonatal, child and adolescent health care (Foster & Shields, Citation2020; Kuo et al., Citation2012; Shields, Citation2018). The involvement of family members, particularly parents, in the provision of nursing care to children and young people has evolved over the last six decades to reflect the social context of family. Nursing philosophy has progressed from parental presence, through parental participation and partnership to what is currently regarded as contemporary family-centred care (Smith & Coleman, Citation2010). Research interest and scholarship has tended to focus on defining ‘family’, broadening family-centred care practice to include members of the extended family, such as grandparents (Tatterton & Walshe, Citation2019a) and to recognise alternative families, such as LGBTQ+ parents (Chapman et al., Citation2012) and adoptive families (Goldberg et al., Citation2020). To our knowledge, no research to date has explored the provision of family-centred care after the death of a child. In this paper we explore the perspectives of nurses, allied health professionals and care support workers caring for families of children after death to identify sources of emotional challenge and suggest ways in which organisations can support practitioners delivering this care.

The emotional challenges of providing palliative care are well documented (Chan et al., Citation2015; Melvin, Citation2012; Slocum-Gori et al., Citation2013), and can result in high levels of emotional exhaustion and ‘burnout’, describing complex physiological and psychological experiences or responses to prolonged exposure to stress (Slater et al., Citation2018). These challenges not only affect practitioners but may also impact on the quality of care provided (Salyers et al., Citation2017). Chan et al. (Citation2015) describe the ability to cope with the challenges of working in hospice care as a competence that palliative care practitioners need to acquire.

Martin House is a 15 bed hospice for children and young people, covering the Yorkshire and Humber region in the North of England. The hospice has three cool rooms, used to care for children after death for a period of up to five days. Care is delivered by members of the care team – usually those who knew the child prior to their death, although a growing number of children are referred to the hospice after death (Tatterton et al., Citation2019). The care team, more than 50% of which are registered nurses with the remainder including allied health and social care professionals and non-registered staff, deliver care to families of deceased children, on the same 1:1 basis as children before death. In preparing a policy for care of a child after death it became apparent that there was no published evidence focusing on this area of children’s hospice care.

Qualitative approaches are useful in areas that are complex and under-researched or novel (Silverman, Citation2013). Due to the limited amount of research that has been conducted surrounding the provision of family-centred care after the death of a child, an exploratory study has been designed using a qualitative methodology. Although there are some published studies that explore the emotional challenges of supporting families following the death of a child in environments such as the neonatal unit (Gibson et al., Citation2018; Kilcullen & Ireland, Citation2017) and intensive/critical care (Jones et al., Citation2016; Pawar et al., Citation2018), to our knowledge no studies have focused on the setting of children’s hospices or cases where care has extended beyond the hours immediately following death. Owing to the limited knowledge base and size of the hospice care team, we used a questionnaire to enable us to survey all members of staff to develop a broad understanding of the experiences of those involved in caring for the families of children after death.

Aim

The aim of this study is to explore the sources of emotional challenge, perceived by children’s hospice staff, caring for the families of children in a children’s hospice cool room.

Method

A survey was developed to explore the perspectives of hospice practitioners around the care of children after death, and their perceptions of providing care to the bereaved families, whilst the child’s body remained in the hospice. The survey comprised open questions designed to help practitioners reflect on their practice and encouraged them to consider how their values and previous experiences impact on their approach to care. Practitioners were not offered any incentive to participate.

Design

Data was collected using a Google Forms survey, comprising 11 questions. Demographic information was collected on length of service and professional background. The survey employed open questions and free text boxes, designed to allow respondents to discuss their responses, in order to collect in-depth qualitative data. The design of the survey was based on discussions with a professional development group of staff, from nursing, allied health professional, care and counselling backgrounds. The survey was piloted with 10 members of staff in order to gather feedback to inform the final version of the survey.

Ethical considerations

Health Research Authority approval was sought, however not required. Local approval was granted by the hospice Research Committee. Participants were informed both verbally and in writing that completion of the questionnaire was voluntary, and that they could withdraw at any time without offering reason (see Evans et al., Citation2002). Questionnaires were analysed anonymously. Data was stored electronically on an encrypted drive, complying with GDPR regulations (Summers, Citation2018).

Data analysis

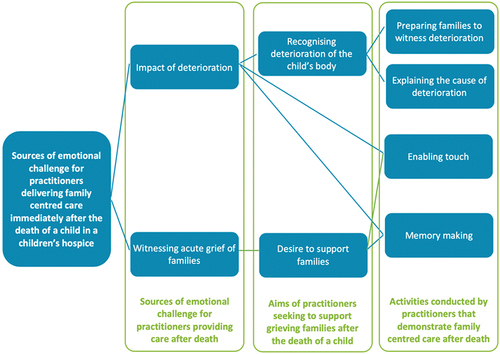

An inductive approach to thematic analysis was undertaken (Boyatzis, Citation1998), using NVivo (Version 12.6). We followed the six-phase framework (Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017) to assure rigour in coding and thematic development. Responses to individual questions were amalgamated by MT, independently read and re-read to ensure familiarity with the data by MT and AH, and notes on initial impressions and potential connections were made. Line-by-line coding was used to develop initial codes, which were again, developed independently, before being discussed and scrutinised by the wider project team. A priori codes were not used. From this, preliminary themes were identified by grouping codes together, predominantly by frequency or patterns. For example, respondents discussed their roles in enabling parents, brothers, sisters and grandparents to kiss, cuddle, stroke and hold the deceased child. These codes were collated into an initial theme ‘enabling touch’. We ensured that all data derived from the completed surveys was represented in the thematic framework before progressing. Themes were then reviewed and refined to ensure that they made sense and were supported by the data. At this stage, we separated ‘supporting families in witnessing the deterioration of the child’s body’ to two distinct, but related themes: ‘preparing families to witness deterioration’ and ‘explaining the cause of deterioration’. Finally, we identified the essence of the theme, arranging a thematic map, which illustrates the relationship between themes that explain the sources of emotional challenge for practitioners delivering family-centred care immediately after the death of a child in a children’s hospice.

Participants

Participants all worked at Martin House as either permanent or bank members of staff. All practitioners were involved in delivering care to families of children in hospice cool rooms and provided direct care to the bodies of deceased children.

Of 59 practitioners invited to complete the survey, a total of 56 surveys were returned and analysed (94.9% response rate). The professional background of staff is shown in , the majority of which comprises registered nurses. 80% of participants have worked for the organisation for more than two years ().

Table 1. Professional background of staff.

Table 2. Length of service.

Findings

Findings have been organised into two core themes which represent the emotional challenges of delivering family-centred care immediately after the death of a child: the impact of deterioration of a child’s body after death and witnessing the acute grief of families. These are outlined, using quotes from practitioners to illustrate analysis and to retain the voice of practitioners throughout. Although the themes are presented individually, there was strong overlap between themes, each impacting on the other, as illustrated in . Secondary grouping of the themes (shown in green) illustrates the primary sources of emotional challenge for practitioners providing care after death, the aims of practitioners when supporting families, and activities conducted by practitioners that demonstrate family-centred care after death.

Family-centred care after death

Family-centred care was highlighted prolifically throughout the study, which set out to explore the experiences of practitioners involved in the care of children’s bodies after death, in a children’s hospice. Following death, bodies can remain in the hospice for up to five days, together with the bereaved family. During this time the child’s body and bereaved family are cared for by the nursing team. Practitioners conceptualise the bodies of children as children, referring to them as such throughout the research:

‘I remember caring for a [deceased] toddler-aged child [in the cool room] that I would usually have rolled, but I lifted him off the bed for a cuddle whilst we changed the sheet.’

From the point of death to the child’s body leaving the hospice, practitioners discussed the provision of family-centred care, which shaped the decisions they made and the care they provided to the family. Examples include consistently referring to individuals by their relationship to the child, supporting family members to deliver or shape care and involving whole families in care provision. Staff discussed these elements of family-centred care, and how they compound the experience of an emotional challenge for practitioners, when supporting bereaved families. Practitioners also drew comparisons between caring for children before and after death, noting that there is little difference in the family-centred aspects of care:

Taking account of the dignity required for the child and the emotions of the child’s family – holding that pain is an element; preparing those around you and being sensitive to their needs which may only be obvious, or change, in the moment. It actually isn’t that different from other times.

Practitioners discussed the care of parents most frequently, followed by siblings and other family members, including grandparents. Practitioners noted that the focus of care when caring for a living child is always the child, regardless of their age, condition or abilities. Following death however, with the exception of very few practical tasks, the focus of care is shifted, predominantly, to the child’s parents where the child is used as a means to express empathy, control and recognition of an individual’s continuing bond and relationship to the deceased child. For example, one respondent answered:

I knew it was important for dad to carry him down to the [cool room] – [Dad] talked about it before he died. He said it was the last thing he could do for his little boy. It was important that I enabled Dad to do what he needed to.

A family-centred approach to care influenced both the aims of the care provided to families following the death of a child and the activities of practitioners. These are broken down and explored below.

Impact of deterioration of the child’s body

The physical deterioration of a child’s body after death was discussed by many participants, both in terms of the impact this has on care of the body and on the support required by and given to the bereaved family.

Recognising deterioration of the child’s body

The findings suggest that practitioners felt pressurised to recognise the deterioration of a child’s body after death. Three drivers were highlighted; the first of these relate to the needs of practitioners, the second and third drivers to the desire of practitioners to support grieving families. Practitioners wanted to feel prepared when entering the cool room, ‘knowing what to expect’, and to feel confident in being able to recognise and predict normal post-mortem deterioration (driver 1). The ability to recognise deterioration would allow practitioners to appropriately care for a child’s body (driver 2), as well as support families by providing information on current and anticipated changes to the condition of the body (driver 3), as expressed by one participant:

[I]t’s not just knowing what to look for, but being prepared for what the changes mean to the care [in the cool room] and how their families will feel. It’s a lot of pressure for staff, who at the end of the day, are not mortuary-trained or undertakers.

Experienced practitioners felt more confident in recognising and anticipating these changes, and the implications of them, when caring for a child in the cool room, particularly when working with less experienced colleagues. Practitioners discussed the provision of informal education and emotional support to junior colleagues, recognising the emotional challenge of providing protracted care after death, beyond last offices, as expressed by one participant:

I think it is everyone’s responsibility to remind each other that we should still move the person with the same care, attention and aids (i.e. PAT slide) as we would when they were alive. It’s important to prepare the person assisting prior to moving (if it’s their first time) that the child/young person will look/feel very different (cold/solid to touch). This will ensure they’re not shocked.

Members of staff with less experience expressed concern in being able to anticipate post-mortem changes to the body and to recognise normal versus concerning deterioration. These concerns added to the experience of emotional challenge, often discussed alongside feelings of anxiety, dissatisfaction and inadequacy. For this group of practitioners, it appeared that concerns around their ability to recognise deterioration stem from their need for reassurance to enable them to provide direct care to a child’s body, rather than to support family members.

Preparing families to witness the deterioration

Although staff discussed physiological changes in relation to the care they provide, the dominant reason for concern surrounded anxieties in being able to prepare families for the deterioration they were likely to witness, recognising the impact of this on parents and other family members, including siblings, as expressed by one respondent:

[W]e see more children who have come after organ donation or have died from sudden/traumatic deaths. Helping those families prepare for changes can be huge, particularly when often the child was well until the incident that led to their death. It’s important we prepare parents, grandparents and brothers and sisters too.

Staff with previous experience appeared to struggle less with this but, nevertheless, took their role in offering family-centred bereavement support very seriously. Family-centred approaches to care were characterised by facilitating parental control, decision making and involvement in caring for the child’s body. Practitioners discussed how an understanding of physiological deterioration enables the provision of family involvement in care, increasing the confidence and scope of staff and therefore the opportunities presented to families. Examples of care in these instances included holding, changing and moving the deceased child.

Some practitioners expressed the dual challenge of recognising deterioration and providing support to families, acknowledging the knowledge, skills and confidence required in both the assessment of a deceased body and counselling and interpersonal skills required to support grieving individuals. For some, the need for both sets of skills increased their perception of challenge and led them to seek support form colleagues, as expressed here:

Each situation is very different you tend to react with what you’re presented with at any given time. You can always have guidelines but they’re not always appropriate depending on what’s going on. You have to be very mindful of the child, their family and yourself and do what you feel is right and safe at that time. In my experience I have learnt from working with more experienced colleagues asking their advice and drawing on their knowledge which is invaluable.

Some practitioners perceived that despite training being provided, competence could only be achieved through the provision of direct care, working with and learning from more experienced colleagues at the bedside. This was often cited alongside the recognition that the experience of families differ, valuing individualised, family-centred care.

Explaining the cause of deterioration

Feeling that they needed to be able to explain the physical deterioration of a child’s body to a family added to the emotional challenge of caring for children after death. Practitioners were concerned in their ability to be able to both confidently and sensitively explain the physical changes happening to the child’s body. As one respondent reported:

[I]t can be hard to tell families what’s happening to the body. Not because I don’t know, but because it’s upsetting. It can be hard to find the words to say things kindly. The parents have been through enough without me making things worse by explaining changes. Sometimes there’s no easy way to say things. I dread being asked.

Enabling touch

Touch was discussed by many practitioners, who recognised the therapeutic benefit for bereaved families. Means of physical contact varied; handholding was most frequently highlighted by practitioners, but also included cuddling deceased children either by taking the child out of the bed or by encouraging parents to lay next to the child’s body. Practitioners also provided examples where touch was used when delivering care such as transferring the child from their bedroom into the cool room, dressing the child after death, or partaking in memory making activities:

[T]he last time I did art activities in the [cool room], I did the prints while a parent cuddled the child

Touch was also used as a means for practitioners to demonstrate sustained recognition of the relationship between the deceased child and family member and as a basis for discussion around family life before death. Examples included supporting parents to touch their child as they would ‘as part of a bedtime routine’, such as laying with and kissing their child. Practitioners perceived that this developed and consolidated the therapeutic relationship between the family and practitioner and allowed the practitioner to show that they value the relationship between the deceased child and family member: ‘he is still the child’s grandad.’

Witnessing the acute grief of families

Practitioners found witnessing the grief of family members challenging, regardless of their length of service, although it appeared that less experienced staff found the experience more difficult. Practitioners were keen to learn from more experienced members of the team, and to show families they cared:

I get a lot of support from more experienced staff. I’ve cared for a few children in the [cool room] now, but still feel reassured that I can turn to colleagues for support.

It’s important that families know we care about their child. For most families, they get that because we nursed their child before death, but for families who come after death, it’s important that we get that message across. I think parents recognise and are reassured to see that we are very respectful to the child/young person

Desire to support families

The desire to support families following the death of their child is congruent with the model of care offered by the hospice, a deeply rooted child-focused, family-centred model of care. Practitioners found their perception of their ability to support families affected their experience of bearing witness. Practitioners who felt able to support grieving families reported less challenge and distress from observing the experience of bereaved parents and siblings. Conversely, staff who felt less confident in their ability to support families reported greater distress in bearing witness to that grief.

Memory making

Memory making was viewed by all staff as being an important element of care offered in the hospice cool room. Memory-making activities range from simple fingerprints on tiles or canvases, to much larger hand and footprint collections of the whole family. ‘Artistic ability’ was highlighted by practitioners here; those who perceive themselves as being less artistic as well as those with less experience found this area of care challenging. Staff perceived artefacts made during memory making as ‘treasures’ for families to keep forever, adding to the pressure of needing to ‘get things right’. As one respondent reported:

families may want to wash [their child] for religious reasons or prepare them in particular clothes. We give more time and handling is slower and at the pace of the person you are with. I want to get it right for them as much as I can it’s a memory they will keep and try make such a sad and difficult time for them as easy going as possible so much for them to process

Finally, practitioners placed great significance on the fact that care in the cool room represents the last opportunity for most families to have physical contact with the deceased child, and to make memories. In this sense, memories include artefacts created to remember the child (referred to as ‘treasures’ by some practitioners), as well as memories of time in the cool room more broadly. Staff discussed the ‘beauty’ and ‘privilege’ of being able to care for families at this time, represented neatly in this quote: ‘It’s hard, but very special to be part of’.

Discussion

This paper highlights the perspectives of practitioners working in a children’s hospice and caring for families immediately after the death of their child, whilst the child’s body was resident in a hospice cool room. Eight sub-themes were identified around the sources of emotional challenge for practitioners delivering care in hospice cool rooms, derived from the two key themes of the impact of deterioration of the child’s body and witnessing the acute grief of families. The eight themes were arranged into three groups: sources of emotional challenge, the aims of practitioners seeking to support grieving families and activities conducted by practitioners that demonstrate family-centred care.

Family-centred care

The care provided by practitioners reflected the principles of family-centred care (Smith & Coleman, Citation2010). These were demonstrated in the provision of practical nursing care, through communication and the conceptualisation of loss, discussed by practitioners involved in the care of families. Practitioners described the development of a relationship with families as a core element of their role. The role of practitioners in the hospice is to provide care throughout the continuum of palliative care, described by Together for Short Lives (Widdas et al., Citation2013) which includes care during a child’s illness, death and in bereavement. Models of care used in children’s hospices are grounded in family-centred care philosophy (Tatterton & Walshe, Citation2019b), with almost equal emphasis placed on the needs of family members as there is on the referred child (Together for Short Lives, Citation2017). Developing partnerships with families is considered to be an important element of family-centred care by practitioners (Trajkovski et al., Citation2012) and provides practitioners with a degree of job satisfaction. This correlates with the findings of this study regarding experienced members of staff, however more junior practitioners found this added to their experience of emotional challenge. The notion of developing effective professional and therapeutic relationships with families attracts some practitioners into palliative and hospice care (Parola et al., Citation2018). Establishing therapeutic relationships with families comes at a cost to practitioners through bearing witness to the grief and sadness experienced by family members following the death of their child (Olsman, Citation2020).

Effective communication with families was central to this work. Practitioners were driven to establish and maintain effective therapeutic relations with families, strengthened through the use of effective interpersonal skills. Genuine interest in meeting the needs of families was demonstrated in the way that staff communicated with family members, providing emotional support in response to grief, and fulfiling requests in relation to the care of their deceased child.

The ability of staff to respond to both the perceived and expressed needs of family members was affected by that awareness of the physiological processes that occur after death. Staff are keen to aid the understanding of family members through providing and receiving information from families. Walker and Deacon (Citation2016) describe the same phenomena in the adult critical care setting which leads to opportunities for shared decision-making participation and choice in various elements of care. The importance of providing families with timely information is well documented (Fanslow, Citation1983; Fraser & Atkins, Citation1990; Van Der Klink et al., Citation2010; Walker & Deacon, Citation2016). However, their ability to comprehend information can fluctuate (Mayer et al., Citation2013; Rejnö et al., Citation2013), strengthening the argument for building effective therapeutic relations with families, encouraging families to express their needs openly. Organisations should therefore provide staff with the resources to enable the development of effective therapeutic relationships with families facing acute grief. Examples of the ways in which practitioners engage with families include gestures such as making drinks, referring to relatives by their name, and their relationship to the deceased child. Similar findings were reported in a study exploring after death care of adults (Olausson & Ferrell, Citation2013).

Opinions on the expression of empathy when supporting bereaved family members is mixed; studies conducted in adult critical care environments suggest that practitioners can be reluctant to discuss the needs of family members, concerned that doing so may be more upsetting (Page et al., Citation2019), or believing that they did not wish to speak about their loss (Broden & Uveges, Citation2018).

Supporting and validating grief

Staff anxiety around their ability to engage in the provision of bereavement support is well documented in current literature (Jensen et al., Citation2017; Lin & Fan, Citation2020; McAdam & Erikson, Citation2016). Published evidence suggests that there are many reasons for this including the lack of standardisation of needs (Lin & Fan, Citation2020). Predicting the way in which family members may react (De Vleminck et al., Citation2013) and concerns around personal emotional well-being (Walker & Deacon, Citation2016) influence how practitioners feel when supporting the bereaved family members. Walker and Deacon (Citation2016) note that anxieties around professional ability to support bereaved individuals adequately leads to practitioners feeling reluctant to provide this element of care, considered synonymous with hospice work (Tatterton et al., Citation2019).

The Royal College of Nursing recognise the requirement for those working in children’s palliative care to be able to meet the needs of the bereaved family (Royal College of Nursing, Citation2018). In order to enable staff to meet the needs of bereaved family members, practitioners require training, education and support to enable them to ‘understand grief reactions, manage negative emotional responses, accept the grief reactions of […] family members, and provide support.’ (Lin & Fan, Citation2020, p. 4). This approach can help staff to realise their potential and feel more comfortable in the role (Raymond et al., Citation2017), leading to increased job satisfaction (Friedrichsdorf & Bruera, Citation2018), reducing the emotional burden of their work (Meller et al., Citation2019). Research by Olausson and Ferrell (Citation2013) support this, suggesting that effective professional education can lead to positive experiences of death facilitating engagement and increasing the retention of staff.

Strengths and limitations

This study has provided novel insight into the perspectives of practitioners who support bereaved families, whilst caring for deceased children in children’s hospice cool rooms. Despite the theoretical transferability of this study to policy and practice surrounding contemporary family-centred care, there are a number of limitations that should be considered.

This study was conducted in a single children’s hospice, providing limited perspectives on which to base finings. Additionally, the exploration of family-centred care was not the intended focus of this study and therefore questions did not directly relate to the provision of family-centred care after the death of a child. Related to this, the use of a questionnaire to collect qualitative data may have impacted on the disclosure of participants. The use of interviews in data collection or a phenomenological design may have led to the sharing of deeper and richer experiences of those involved in caring for families after the death of a child in a children’s hospice cool room. Research with bereaved families, exploring their experiences in the days that follow the death of their child would enable the development of hospice-based cool room care.

Implications to practice

Family-centred care has been highlighted throughout this paper, demonstrating the importance of continuing to offer family-centred care after the death of a child. Insights provided by practitioners showed that this approach to care is well-entrenched in children’s hospices. However, organisations can support the development of practice through the provision of training and education, and ensuring that staff have the resources to meet the needs of families in the days that follow the death of a child.

Practitioners should be provided with training and education focusing on the importance of family-centred care, grief and loss, as well as the physiological changes that occur after death. In addition to theoretical learning, these findings suggest that staff would benefit from peer mentorship where support is provided by more experienced members of the care team.

Finally, organisations must ensure that they provide sufficient time for practitioners to meet the needs of bereaved families in the days following death, whilst the child’s body is resident. Not only does this allow care to be responsive to families but reduces their perception of pressure and the need to manage conflicting priorities by those providing care.

Implications for policy

The emotional challenge of supporting bereaved families is clear both from existing literature and from the findings of this study. As such organisations must provide staff support to practitioners who care for families after the death of a child, which recognises and supports the experience of caring for deceased children and bereaved members of the deceased child’s family.

Conclusion

Family-centred care is a fundamental principle on which British children’s nursing is based and has been used as a guiding philosophy to inform the design, delivery and evaluation of children’s hospice services. The role and needs of individuals within a family should be recognised by hospice practitioners at all stages of care: through illness, dying and bereavement care after the death of a child. There are a number of emotional challenges faced by practitioners when caring for children in cool rooms, both around the practical care of the deceased child and supporting the needs of the child’s family. Practitioners seek to provide care that recognises the importance of family and support families to deal with the changes that occur after death.

Organisations can support practitioners to deliver care in cool rooms by providing training and education on anticipating and managing the pathophysiological changes that occur after death as well as training in grief and loss, and how to support a bereaved family. The provision of adequate training alongside staff support that recognises the emotional challenges of providing this kind of care can result in increased job satisfaction and staff retention, reducing burnout and improving the experiences of newly bereaved families.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael J Tatterton

Dr Michael J Tatterton is an associate professor of children’s nursing in the School of Nursing and Healthcare Leadership at the University of Bradford and a former consultant nurse in children’s palliative care at Martin House Children’s Hospice, where he led on nursing, research and education. His research interests include palliative care for babies, children and young people, family centred care, family nursing and grief, loss and bereavement. You can follow Michael on Twitter: @MJTatterton

Alison Honour

Alison Honour is an Occupational Therapist at Martin House Children’s Hospice. She works both as a generic care team member and as an OT and has worked with bereaved sibling groups. She is part of the Moving and Handling Team and is a qualified Moving and Handling Trainer. Prior to working at Martin House Alison worked in the NHS for 20 years, primarily working with children with disabilities and their families in their own homes. You can follow Alison on Twitter: @alison_honour

Judith Lyon

Judith Lyon is a dual-qualified adult and children’s nurse at Martin House Children’s Hospice, where she has worked for 31 years. In addition to her role on the Care Team, Judith leads the bereavement support for grandparents and previously supported bereaved parents through visits and group work.

Lorna Kirkby

Lorna Kirkby is a children’s nurse at Martin House Children’s Hospice, providing care to children and young people with life limiting conditions. In addition to her clinical role, Lorna is studying an MSc in palliative care at Newcastle University.

Mary Newbegin

Mary Newbegin is an Occupational Therapist who has worked at Martin House for over 18 years, initially on the care team and later as a Care Team Leader. During this time, she has worked for many years as a Moving and Handling trainer and also led the Bereaved siblings Group, having completed a Diploma in Childhood bereavement. She is currently working as the Transition and Discharge lead.

Jo Webster

Jo Webster is a bereavement counsellor at Martin House Children’s Hospice, providing emotional support to children and families before and after the death of a child.

References

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Broden, E. G., & Uveges, M. K. (2018). Applications of grief and bereavement theory for critical care nurses. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 29(3), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2018595

- Chambers, L. (2018). A guide to children’s palliative care (4th ed.). Together for Short Lives. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2014.04.011

- Chan, W. C. H., Fong, A., Wong, K. L. Y., Tse, D. M. W., Lau, K. S., & Chan, L. N. (2015). Impact of death work on self: Existential and emotional challenges and coping of palliative care professionals. Health & Social Work, 41(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlv077

- Chapman, R., Wardrop, J., Freeman, P., Zappia, T., Watkins, R., & Shields, L. (2012). A descriptive study of the experiences of lesbian, gay and transgender parents accessing health services for their children. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(7–8), 1128–1135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03939.x

- De Vleminck, A., Houttekier, D., Pardon, K., Deschepper, R., Van Audenhove, C., Vander Stichele, R., & Deliens, L. (2013). Barriers and facilitators for general practitioners to engage in advance care planning: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 31 (4), 215–226. Scand J Prim Health Care. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2013.854590

- Evans, M., Robling, M., Maggs Rapport, F., Houston, H., Kinnersley, P., & Wilkinson, C. (2002). It doesn’t cost anything just to ask, does it? The ethics of questionnaire-based research. Journal of Medical Ethics, 28(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.28.1.41

- Fanslow, J. (1983). Needs of grieving spouses in sudden death situations: A pilot study. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 9(4), 213–216.

- Forrester, L. (2008). Bereaved parents’ experiences of the use of “cold bedrooms” following the death of their child. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 14(12), 578–585. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.12.32062

- Foster, M., & Shields, L. (2020). Bridging the child and family centered care gap: Therapeutic conversations with children and families. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 43(2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2018.1559257

- Fraser, L. K., Gibson-Smith, D., Jarvis, S., Norman, P., & Parslow, R. (2020). “Make every child count” estimating current and future prevalence of children and young people with life-limiting conditions in the United Kingdom. Bristol, UK: Together for Short Lives.

- Fraser, S., & Atkins, J. (1990). Survivors’ recollections of helpful and unhelpful emergency nurse activities surrounding sudden death of a loved one. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 16(1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:009917679090261F

- Friedrichsdorf, S., & Bruera, E. (2018). Delivering pediatric palliative care: From Denial, Palliphobia, Pallilalia to palliactive. Children, 5(9), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5090120

- Gibson, K., Hofmeyer, A., & Warland, J. (2018). Nurses providing end-of-life care for infants and their families in the NICU. Advances in Neonatal Care, 18(6), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000533

- Goldberg, A. E., Frost, R. L., Manley, M. H., McCormick, N. M., Smith, J. A. Z., & Brodzinsky, D. M. (2020). Lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents’ experiences with pediatricians: A mixed-methods study. Adoption Quarterly, 23(1), 27–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926755.2019.1675839

- Jensen, J., Weng, C., & Spraker-Perlman, H. L. (2017). A provider-based survey to assess bereavement care knowledge, attitudes, and practices in pediatric oncologists. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(3), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0430

- Jones, J., Winch, S., Strube, P., Mitchell, M., & Henderson, A. (2016). Delivering compassionate care in intensive care units: Nurses’ perceptions of enablers and barriers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 3137–3146. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13064

- Kilcullen, M., & Ireland, S. (2017). Palliative care in the neonatal unit: Neonatal nursing staff perceptions of facilitators and barriers in a regional tertiary nursery. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0202-3

- Kuo, D. Z., Houtrow, A. J., Arango, P., Kuhlthau, K. A., Simmons, J. M., & Neff, J. M. (2012). Family-centered care: Current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(2), 297–305. 1 0.1 007/s10995-011-0751-7

- Lin, W. C., & Fan, S. Y. (2020). Emotional and cognitive barriers of bereavement care among clinical staff in hospice palliative care. Palliative & Supportive Care, 18(6), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895152000022X

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 8(Autumn), 3. https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335/553

- Mayer, D. D. M., Rosenfeld, A. G., & Gilbert, K. (2013). Lives forever changed: Family bereavement experiences after sudden cardiac death. Applied Nursing Research, 26(4), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.007

- McAdam, J. L., & Erikson, A. (2016). Bereavement services offered in adult intensive care units in the United States. American Journal of Critical Care, 25(2), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2016981

- Meller, N., Parker, D., Hatcher, D., & Sheehan, A. (2019). Grief experiences of nurses after the death of an adult patient in an acute hospital setting: An integrative review of literature. Collegian, 26 (2), 302–310. Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.07.011

- Melvin, C. S. (2012). Professional compassion fatigue: What is the true cost of nurses caring for the dying? International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 18(12), 606–611. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.12.606

- Olausson, J., & Ferrell, B. R. (2013). Care of the Body After Death. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17(6), 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.CJON.647-651

- Olsman, E. (2020). Witnesses of hope in times of despair: Chaplains in palliative care. A qualitative study. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2020.1727602

- Page, P., Simpson, A., & Reynolds, L. (2019). Bearing witness and being bounded: The experiences of nurses in adult critical care in relation to the survivorship needs of patients and families. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(17–18), 3210–3221. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14887

- Parola, V., Coelho, A., Sandgren, A., Fernandes, O., & Apóstolo, J. (2018). Caring in Palliative Care. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 20(2), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000428

- Pawar, S., Jacques, T., Deshpande, K., Pusapati, R., & Meguerdichian, M. J. (2018). Evaluation of cognitive load and emotional states during multidisciplinary critical care simulation sessions. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning, 4(2), 87–91. 1 0.1 136/bmjstel-2017-000225

- Raymond, A., Lee, S. F., & Bloomer, M. J. (2017). Understanding the bereavement care roles of nurses within acute care: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26 (13–14), 1787–1800. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13503

- Rejnö, Å., Danielson, E., & Berg, L. (2013). Next of kin’s experiences of sudden and unexpected death from stroke - a study of narratives. BMC Nursing, 12(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-12-13

- Royal College of Nursing. (2018). RCN competencies: Caring for infants, children and young people requiring palliative care| Royal college of nursing (Second ed.).

- Salyers, M. P., Bonfils, K. A., Luther, L., Firmin, R. L., White, D. A., Adams, E. L., & Rollins, A. L. (2017). The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(4), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9

- Shields, L. (2018). Why international collaboration is so important: A new model of care for children and families is developing. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 38(2), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057158518765072

- Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research (Fouth ed.). Sage.

- Slater, P. J., Edwards, R. M., & Badat, A. A. (2018). Evaluation of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology, and palliative care services group. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 10, 67–85. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S176848

- Slocum-Gori, S., Hemsworth, D., Chan, W. W. Y., Carson, A., & Kazanjian, A. (2013). Understanding Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue and Burnout: A survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliative Medicine, 27 (2), 172–178. Palliat Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311431311

- Smith, L., & Coleman, V. (Eds.). (2010). Child and family-centred healthcare: Concept, theory and analysis (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sque, M., Walker, W., Long-Sutehall, T., Morgan, M., Randhawa, G., & Rodney, A. (2018). Bereaved donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation, and perceived influences on their decision making. Journal of Critical Care, 45, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.002

- Summers, S. (2018). The general data protection regulation (GDPR): Research and archiving FAQs. UK Data Service, UK Data Archive.

- Tatterton, M. J., Summers, R., & Brennan, C. Y. (2019). A Qualitative Descriptive Analysis Of Nurses ’ perceptions of hospice care for deceased children following organ donation in hospice cool rooms, 25(4), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2019.25.4.166

- Tatterton, M. J., & Walshe, C. (2019a). Understanding the bereavement experience of grandparents following the death of a grandchild from a life‐limiting condition: A meta‐ethnography. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(7), 1406–1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13927

- Tatterton, M. J., & Walshe, C. (2019b). How Grandparents Experience the Death of a Grandchild With a Life-Limiting Condition. Journal of Family Nursing, 25(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840718816808

- Together for Short Lives. (2017) . The state of the UK children’s hospice nursing workforce: A report on the demand and supply of nurses to children’s hospices (Issue April).

- Trajkovski, S., Schmied, V., Vickers, M., & Jackson, D. (2012). Neonatal nurses’ perspectives of family-centred care: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(17–18), 2477–2487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04138.x

- Van Der Klink, M. A., Heijboer, L., Hofhuis, J. G. M., Hovingh, A., Rommes, J. H., Westerman, M. J., & Spronk, P. E. (2010). Survey into bereavement of family members of patients who died in the intensive care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 26(4), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2010.05.004

- Walker, W., & Deacon, K. (2016). Nurses’ experiences of caring for the suddenly bereaved in adult acute and critical care settings, and the provision of person-centred care: A qualitative study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 33, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2015.12.005

- Widdas, D., McNamara, K., & Edwards, F. (2013). A core care pathway for children with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions (Third). Together for Short Lives.