ABSTRACT

The island of Seili, in the south-western archipelago of Finland, is famous for its history as a leprosy colony and mental asylum. The island formed a small, hierarchical community run by priests and hospital officials. In this article, we examine the history of the burial crypt in Seili church by comparing information from historical documents and observations made during archaeological fieldwork. The material gathered from these two sources is conflicting, suggesting an interesting history in the use of the burial crypt. It seems that women’s coffins could easily be moved elsewhere from the crypt when new coffins belonging to males were interred. It is argued that identifying the buried individuals would be necessary for a taphonomic study of the mummification processes and ensuring that the information about the crypt is based on facts. However, the identification is difficult due to inconsistent historical records. This underlines the importance of Post-Medieval archaeology in studying sites connected to family histories.

Introduction

Burials were carried out in Finnish churches from the Middle Ages to the early 19th century. Churches were expensive and exclusive burial places, often available only to wealthy and distinguished families (e.g. Mytum, Citation2017, p. 801; Valk, Citation1994, p. 62;). These mainly included nobles, priests, officials and wealthy landowners (e.g. Moilanen & Hiekkanen, Citation2020, p. 49; Paavola, Citation1998). It is sometimes possible to determine the identity of these individuals through written documents (e.g. Alterauge et al., Citation2017; Väre et al., Citation2015, Citation2021). In addition, the interdisciplinary research of these remains offers an insight into how narratives about the dead are formed at the intersection of history, oral history, material culture and the lived past. The church burials in the Seili church provide an interesting case study for comparing oral tradition and historical sources to the field documentation of burials.

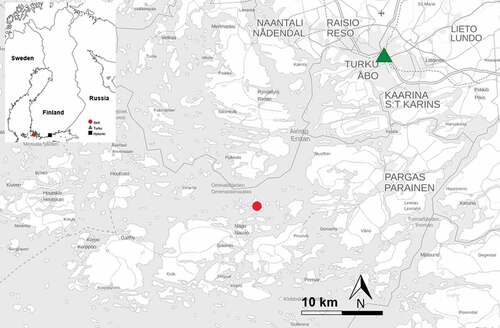

The island of Seili is located in the south-western archipelago of Finland, about 30 kilometres south of the city of Turku (). The small island is only 2,5 kilometres long and 1,5 kilometres wide, but it has a rich history. It is well-known for its leprosy colony and mental asylum. Both were founded in the early 17th century and operated on the island partly simultaneously, the mental hospital until 1962. Today, Seili is a popular destination for summer tourists and researchers working at the University of Turku Archipelago Research Institute located on the island (Räikkönen et al., Citation2021).

Figure 1. Map of southwestern archipelago in Finland, and the location of Turku and Seili island. Map: Ulla Moilanen and Sofia Paasikivi.

The wooden church of Seili was built in 1733 on the site of an earlier chapel, which was demolished after falling into disrepair (Vuorinen, Citation2020, p. 66). The church is a unique building in many ways, as it has a separate enclosed space for leprosy patients to prevent them from infecting other parish members. A stone-built burial vault can be found under the church floor. The crypt is located at the transept of the church and is covered with a wooden hatch. Under the hatch, four stone steps lead to the crypt’s iron door. Neither the crypt nor its entrance is shown on the architectural drawings of the church from 1733 (19th century copies, CitationOulu Provincial Construction Archives), but it can be assumed that it was built at the same time as the wooden church. It is not known who was originally intended to be buried in the crypt when it was built. According to the historical records of deaths and burials in the parish, several individuals were buried inside the church in the 18th century, but only some of them were placed in the crypt. In most cases, the exact location of the burial is described in detail. For example, Anna Christina Björkroth, the widow of comminister (priest) Tilenius, was buried in February 1756 ‘in the choir, on the men’s side (the south side), under the window’ (The National Archives of Finland, Seili, Church records of deaths and burials Citation1723–1840). The records mention Henrik Andersson, who died of leprosy in 1766 and was somewhat unusually buried ‘inside the church, by the door of lepers’. The burial crypt is well-known, but these descriptions of burying individuals also elsewhere in the church indicate that there are more graves under the church floor than previously known. As a very distinctive structure with a separate access by stairs, the burial crypt was likely the most prestigious burial place in the church, with the other under-floor burials valued almost as highly. In some rare cases the church graves at Seili were also available to patients in addition to the clergy and hospital staff.

Several archaeological excavations and surveys have been carried out on the Seili island (Helminen, Citation2010, Citation2012; Pesonen, Citation2016) but no graves have been excavated. The crypt and its content have not previously been studied or documented. In this article, the crypt is examined for the first time in the research literature. We aim to describe the sequence of burials made there in order to detail more precise information about the use of the crypt and the most likely dating of the burials.

The individuals buried in the Seili crypt are part of the narratives associated with the site. We seek to identify the individuals buried in the crypt through historical documents, as their identity is currently based only on oral tradition and stories told by tour guides. Identifying the buried individuals would help to correct anecdotal stories and increase the understanding of the historical community at Seili and the individuals valued within it. From a practical perspective, identifying individuals and their dates of death may help to explore how the mummification process occurs and progresses in different environments and during different seasons. It can also be argued that any individuals have the right to be identified and remembered as the persons they were in life (c.f., Moilanen, Citation2021, p. 86). From this point of view, the study is also linked with commemoration, remembrance, and family histories: who were considered important enough to be buried in a place regarded as the most prestigious on the island, and whose remains were allowed to remain in the crypt when new burials were made and older ones needed to be moved out of the way?

The historical community at Seili

Seili was permanently settled in the Middle Ages. In 1619, King Gustav II Adolf ordered a leprosy hospital to be constructed on the island. Leprosy was considered an incurable disease, and it was widely believed that patients should be isolated from the healthy to avoid the risk of infection. Four years later, leprosy patients of St. George’s Hospital and the poor, disabled individuals from the poorhouse of Holy Spirit in Turku, were transported to the island with their caregivers (Niitemaa, Citation2010, pp. 189–191).

Approximately 28–60 patients suffering from leprosy and mental illnesses were treated in the hospital simultaneously. Once admitted to the island, one was unable to leave. The patients were required to bring 20 thalers and boards for their own coffins upon arrival. The mortality rate among the patients was high, up to 20–30% per year (Turunen & Achté, Citation1976). Currently, there is a 19th–20th-century hospital cemetery on the northern side of the church, but it is unknown when the cemetery was established and whether it was used for burying the leprosy patients (Pesonen, Citation2016).

By the mid-18th century, the number of leprosy patients had declined, and growing numbers of mentally ill patients began to be admitted to Seili. From 1755 onwards, the hospital was reserved exclusively for the latter. The asylum was particularly notorious as a permanent residence for chronically ill female patients, who were forced to live in almost prison-like conditions (Pylkkänen, Citation2012). Sickness and especially mental illnesses were seen as God’s punishment for sins. Because contemporary medicine considered women easily prone to sin and weaker-minded than men, they were often at greater risk of ending up in asylums. Communities occasionally considered unmarried women as a risk, and it was possible, if not probable, that some women ended up in mental hospitals for social rather than health reasons (Ahlbeck-Rehn, Citation2006, pp. 51–57, 60–67, 107). In some cases, political or religious dissidents were also sent to the Seili. In 1745, the Swedish priest Olof Norman was sent to the island for his radical religious teachings. He died on Seili in 1773 (Niitemaa, Citation2010, pp. 190–191).

The hospital patients had separate quarters on the island (Turunen & Achté, Citation1976). The other residents on the island included the hospital caretakers and officials, priests, servants, a blacksmith, a miller, and their families. Just like in other rural parishes at the time, the clergy and officials constituted the upper class in the community. The priests were also heavily involved in the administration of the asylum from the beginning.

The crypt and the burials

The burial crypt measures 2,2 × 2,1 metres, and it is c. 1,4 metres high. Although the church door can be locked, curious persons have regularly visited the crypt in the past decades. We have heard several informal accounts of people visiting the crypt just for excitement. According to several descriptions, the crypt and the mummies were regarded as an unofficial tourist attraction until the 1960s, similar to the 17th-century Northern Finnish mummy of vicar Rungius (Väre et al., Citation2015). We also heard several anecdotal stories from our colleagues who had visited the crypt during their studies. A common story was that students attending biology or geology courses on the island heard about the crypt and visited it later, usually at night. Therefore, regarding archaeological and ancient-DNA research, the crypt cannot be considered uncontaminated or undisturbed.

According to oral tradition, the Seili crypt contains the remains of the hospital director Erik Litander, his wife, and their daughter. The island guides often tell tourists that Erik Litander and his family were awarded a grave in the church for Erik’s long service to the hospital or for a significant donation he made to the parish (Museum church of Seili, Citation2013). However, according to church records, Erik Litander moved to Rymättylä in the mid-1700s, where he died on November 17th, 1772. His burial is recorded in the Rymättylä parish records, which state that he was buried in the church of Rymättylä, not Seili (The National Archives of Finland, Rymättylä, Church records of deaths and burials Citation1716–1785). The story’s claim of a burial place being awarded to someone is also strange since burial places inside churches were expensive and highly valued. Wealthy individuals could also purchase crypts from previous owners (Korhonen, Citation1929, p. 308).

It has generally been assumed that there are three burials in the crypt (Museum church of Seili, Citation2013). However, during fieldwork in 2021, it was revealed that there are five coffins instead of three in the crypt. All are adult-sized plank coffins, and they fill the crypt floor entirely (). All the coffins are trapezoidal in shape, tapering towards the foot end, and they have high tiered lids. All coffins have been assembled with wooden pegs without iron nails or rivets. However, the coffins cannot be examined in detail without transferring them from the crypt. Three of the coffins are in relatively good condition, although they are not intact.

Figure 2. The coffins 1–3 in the crypt. Coffin 4 is located under coffin 2 and is not visible in the photograph as it is surrounded by the collapsed planks and the lid of the upper coffin. The completely collapsed coffin is located under coffin 3. Photo: Ulla Moilanen.

Burial 1

Burial 1 is a coffin closest to the crypt door. The coffin looks unpainted, but it could be varnished or oiled. It is equipped with metal handles and grip plates typical of late 18th and early 19th-century coffins (e.g. Hoile, Citation2018; Kjellberg, Citation2015). The human remains were partially visible through the broken coffin lid. As the coffin is located at the entrance to the crypt, at least part of the damage may have been caused by curious visitors wanting to catch a glimpse of the mummy – especially as both local residents and tourists have been aware of the existence of mummies in the crypt.

The remains belong to an adult male individual, whose right side of the upper body and upper limbs are mummified. The fingernails are intact on both hands. The body lies in the coffin in an extended supine position with the head slightly turned to the left. The right arm is semi-flexed over the abdomen, and the left arm is semi-flexed over the pelvis. Both lower limbs have been skeletonised. The left lower limb is extended, and the right femur is rotated to the right. The bones below the knee are slightly displaced. The face of the mummy is well-preserved, but there is no hair left. Only small textile fragments and a fragment of a copper pin were found at the pelvic area. This indicates that the individual was initially clothed for the burial (c.f., Kuokkanen & Lipkin, Citation2011, pp. 149–154). There is a layer of sawdust at the bottom of the coffin.

Burial 2

Burial 2 is located on top of burial 4. The coffin has been painted white, and there is a large black cross on the lid. The coffin has collapsed, and the floor and the side planks have fallen to the sides of the lower coffin. Both coffins have tiered lids. As a result, the floor planks of coffin 2 are located in a slanted position on the left side of the coffin 4 lid. The human remains in coffin 2 are fully skeletonised, and they have fallen into the niche between the left side of the lid of coffin 4 and the displaced side planks of coffin 2. Because of this, the bones are in a tightly adducted position, and the skull has rotated upside down, the foramen magnum upwards. The right side of the pelvis and right lower limb were originally located at the right side of the coffin, and the bones were found from the area between coffins 1 and 4. The current position indicates that the coffin collapsed after the soft tissues had decayed and the movement of bones happened freely (see Duday, Citation2009; Peyroteo Stjerna, Citation2016, p. 146). The bones belong to a 35–45-year-old adult male (Liira, Citation2022). The bones also have remains of insect pupae attached to them.

Burial 3

Burial 3 is located between burial 4 and the northern wall of the crypt. The coffin and the lid are painted white, and there is a large black cross on the lid. The inner sides of the side planks have been decorated with a grid carving (). The individual lies in the coffin in an extended supine position, legs straight, arms semi-flexed over the pelvis. The individual is almost entirely skeletonised, with only remains of skin on the skull and the bones of the upper body. The bones are well preserved. It was impossible to examine the upper part of the burial properly without removing burials 2 and 4. However, based on the pubic symphysis, the bones belong to 30–50-year-old adult male (Liira, Citation2022). Documentation and sampling had to be done from the foot-end of the coffin, and therefore, only the area below the femurs was accessible. There is a layer of sawdust at the bottom of the coffin.

Burial 4

Burial 4 is located between burials 1 and 3, and under burial 2. The coffin has been painted white, and there is a large black cross on the lid. The sides are equipped with metal handles and grip plates with Bible verses. There are also decorative plates at the head, and the foot ends, but only the one at the head end could be examined. It was impossible to examine the burial in detail because of the difficult placement of burial 2 on top of the lid. It could, however, be observed that the burial belongs to an adult female. No textiles or garments were observed. The upper body, head, and upper limbs are completely mummified, but the lower limbs have been skeletonised. The foot end of the coffin is broken, and the side planks are partially displaced, as are the feet bones.

Burial 5

Burial 5 is located under burial 3. The collapsed coffin and a mummified elbow of the buried individual are only partially visible, and documentation of the burial is impossible due to its location.

The human remains interred in coffins 1–5 do not show evidence of secondary handling or disturbance, and the collapsed coffin can explain the position of individual number 2. None of the individuals are wearing clothes, which is likely because of taphonomic reasons. The taphonomic processes of funerary textiles are very complex, especially in the context of mummified human remains (Lipkin, Ruhl, et al., Citation2021). However, there are also examples of people visiting crypts and taking pieces of garments as souvenirs (e.g. Alterauge et al., Citation2017; Virkkala, Citation1945, p. 24). An anecdotal story told by the Seili tour guides about burial 1 having had a head covering only a few years ago suggests that the lack of funerary clothing might, in this case, be a combination of taphonomic processes and human actions.

Burial sequence and the identity of buried individuals

In order to establish a chronology of the burials and to identify the individuals buried in the crypt, it is necessary to examine the sequence in which the coffins were placed in the crypt. Due to limited space in the crypt, it can be assumed that either burial 5 or 3, being the closest to the back wall, was placed there first. If burial 5 was the first in the crypt, the second burial in the crypt could be burial 3 if it was later lifted on top of coffin 5. The third burial in the crypt could be burial 4, which was placed next to coffin 5. It could be speculated that burial 2, which is currently located on top of burial 4, was the fourth burial in the crypt. It was likely lifted on top of coffin 4 when the last coffin (burial 1) was interred. This would provide the following burial sequence from the oldest to the youngest: 5 (unknown) − 3 (male) − 4 (female) − 2 (male) − 1 (male). The coffins 3, 4 and 2 were painted white with a large black cross on the lid. Similar finishing may indicate that they were constructed approximately at the same time. The youngest coffin is unpainted, but possibly varnished or oiled.

Given the history of the church building, the burials in the crypt should date between 1733 and the early 19th century. Based on the styles of the coffins, the most likely period is mid to late 18 h century (Kiiskinen & Aaltonen, Citation1992, pp. 16–17; Kjellberg, Citation2015; Ströbl, Citationin press). According to the historical records, seven individuals were buried ‘in a vault’ (murade grav) inside the church. Of these, six were adults (three males and three females) and one infant (female), and they are introduced in . The same term (murade grav) has occasionally been used for brick graves under the church floors (Gardberg et al., Citation2003, pp. 30–32), but it is not known whether such structures exist in the Seili church. Here, the term may refer only to the stone crypt, especially since the records describing both Maria Cavonia and Eva Mattsdotter’s (see ) burial state that they were buried ‘in the vault under church floor’ as if there was only one such structure under the church floor. In Johan Salonius’ case, the burial place is referred to as the ‘manager’s vaulted grave’ (föreståndarens murade graf). This description is interesting since it is very similar to the oral tradition that claims the crypt belonged to the hospital manager Litander. There is, however, no evidence in the historical documents that the crypt was used as a burial place for any hospital managers or their close relatives.

Table 1. Burials ‘in the vault inside the church’ according to the records of deaths and burials of Seili parish (The National Archives of Finland, Seili, Church records of deaths and burials 1723–1840).

There is an apparent discrepancy between the historical records and the information provided by archaeological fieldwork. The number of coffins in the crypt is five. This is fewer than the historical records indicate. There was also no sign of a child’s coffin in the crypt. It seems that the coffins of one adult and a child were removed from the crypt. This should have happened soon after the initial burials because all the crypt burials at Seili were made between 1765–1799, according to the parish records ().

According to the order of deaths and burials listed in the historical records, the individuals should have been interred in the following order: Male – Female child – Female – Female – Male – Female – Male. If this information is compared to the observed burials and their likely sequence (unknown – male – female – male – male), it could be assumed that one of the coffins at the back of the crypt (burial 3) might belong to Johan Salonius, and the coffin nearest to the door (burial 1) to Gottfried Blomberg. The individuals in these coffins are adult males, and osteological analysis (Liira, Citation2022) suggests that the age estimates are reasonably consistent with the ages mentioned in the historical records. Coffin 2 could, in theory, belong to Samuel Tilenius, as he is the third man mentioned in the historical records, but there are uncertainties in the identification. The third male was skeletonised, and the insect pupae attached to his bones may indicate that the burial may have taken place in a warmer season. However, none of the males mentioned in the historical records died in the summer months. It seems clear that at least some coffins were transferred from the crypt and relocated elsewhere (c.f., Alterauge et al., Citation2017). Burials 1, 4 and 5 contain mummified human remains, while burials 2 and 3 were almost completely skeletonised. The female in burial 4 is very well preserved. Natural mummification is not uncommon in Finnish churches (e.g. Joona & Ojanlatva, Citation1997; Joona et al., Citation1997; Joona, Citation1997; Lipkin & Kallio-Seppä, Citation2020; Núñez et al. Citation2008; Väre, Citation2015). It can occur in environments with low humidity, cold temperatures, and constant ventilation – factors that have been considered important specifically for mummification in Finnish churches (Núñez et al., Citation2021; 423–4; Väre et al., Citation2020). The process can also be influenced by the season of burial, the age of the deceased, the burial clothing, and the content of bodily fluids (Lipkin, Ruhl, et al., Citation2021; Väre et al., Citation2020). However, partial mummification and the mummification of the skin do not require these optimal conditions (Leccia et al., Citation2018). Mummification of internal organs is less common (Leccia et al., Citation2018) and could not be documented in the case of Seili. The individuals in burials 1 and 4 were only partially mummified but skeletonised below the pelvis.

However, the environment in the Seili crypt may differ from the ventilated spaces under wooden floors. The crypt is an enclosed stone structure, with an opening only at the door. Air does not flow freely in the space. Although the stone vault prevents airflow into the crypt, it also keeps the temperature of the crypt relatively stable and cool and protects the site from the outside elements. The environment stays relatively dry, and the human remains are less exposed to soil microbes and fungi than the remains in underground burials. It has been observed that the sand under churches absorbs moisture and keeps many church sites dry (Nurminen et al., Citation2018). Mummification is possible in relatively humid conditions (Väre et al., Citation2020), but dry conditions may have contributed to the taphonomic processes in the Seili crypt. The crypt has a dirt floor, and the soil around the church is sandy, which may have contributed to stabilising the humidity inside the crypt.

In addition to the microclimate of the crypt, many other factors, such as certain plants in the coffins, the season of death, and the time between death and interment, could have contributed to the mummification process. Although embalming was not practised in Finland at the time, plant material placed under the body may have absorbed fluids, kept insects away, and even slowed down the decomposition process (Karsten & Manhag, Citation2018; Núñez et al., Citation2021). The Seili coffins contained sawdust and wood chips, which may have had the same drying effect. The use of sawdust from the coffin-making process has been common in Finland and may have had several purposes. In addition to keeping the body dry during viewing, it was considered comfortable bedding for the deceased. In eastern Finland, it was also believed that sawdust from a coffin had magical properties and that leaving it outside the coffin could cause the deceased to return as ghosts (Kiiskinen & Aaltonen, Citation1992).

A few small textile fragments were preserved on the bodies, which indicates the presence of burial clothes. One of them had a possible fragment of a pin (University of Turku Archaeological Collections, TYA 981:17) attached to it. Simple linen, cotton, and nettle-weave garments were common during the period, and other materials like silk and wool were used in stockings and hats (Lipkin, Ruhl, et al., Citation2021). Simple burial clothing was often folded and pinned to make it appear like everyday clothes. In some cases, coarse wool textiles may have contributed to mummification, and the effect of textiles on corpses has been relatively well studied (e.g. Nurminen et al., Citation2018; Peacock et al., Citation2020). However, Lipkin et al. (Citation2021) note that although textile preservation is generally good in the case of mummified human remains, the process of textile decomposition itself requires further research. The absence of clothing in the Seili crypt raises interesting questions about taphonomic processes as well as the possibility of looting.

It could be assumed that the individuals buried in warmer seasons and with a long period between death and burial would have begun decaying in the coffins before the burial. According to historical records, Maria Cavonia was the only woman buried in a colder season, making it thus possible that burial 4 belongs to her. Her date of death and burial correlates with the degree of mummification and the burial sequence proposed above.

Interestingly, the possible males in the crypt, Johan Salonius and Gottfried Blomberg died in late November/early December, when temperatures are usually low. However, the individual in coffin 3 is almost entirely skeletonised, while the individual assumed as Blomberg is partially mummified. Salonius was buried about a week after his death, but Blomberg’s funeral was held more than a month after his death. The delay in Blomberg’s burial could indicate that his coffin was stored in a cold, ventilated space before the burial. It also seems likely that a previously placed coffin was removed from the crypt before his coffin was interred.

The time between Blomberg’s death and burial is unusually long in 18th-century Finland, and one can speculate whether it is because the harsh winter conditions made it difficult for the relatives to travel to Seili for the funeral. Seili is located in a marine environment in the archipelago, which is generally a more temperate area than the inland. February is usually the coldest month (CitationFinnish Meteorological Institute). It is possible that in December it was difficult to reach the island, whereas in February the sea ice could be strong enough to allow the relatives to reach the island by sledge and hold the funeral. Although there is some evidence of the climate beginning to warm in Southwestern Finland in the 18th century (Norrgård & Helama, Citation2019), there are no precise climate records from the period. It is therefore impossible to say whether winter temperatures were significantly different at the time of each burial. However, it seems that seasonal variation alone does not explain why only some individuals were mummified. It is likely that several taphonomic factors influenced the decomposition processes inside the crypt.

Discussion

Curious tourists have often visited the burial crypt in the church of Seili. This is both an ethical issue as well as a problem for research as people may move objects in the crypt, disturb archaeological contexts, and contaminate the site with additional DNA or even plant or insect material. Visiting the crypt can also affect the temperature and humidity and increase risks such as moulding.

Historical data allowed the probable identification of two males buried in the crypt. The identification of the others is less conclusive, and the information from historical sources conflicts with the fieldwork findings. Burial places carry various social meanings, and they can be used to communicate ownership and individuality (Rugg, Citation2010). For example, in the Cathedral of Turku, the burial crypts often changed ownership through trade, and new owners could relocate the coffins of previous owners to a new location to make space for new ones. However, this was not officially recommended and sometimes even frowned upon (Korhonen, Citation1929, p. 308). According to historical records, three adult females, one female child, and three adult males were buried in the Seili crypt, but only one female and three males were found during fieldwork. According to the historical sources, the last four individuals buried in the crypt were connected to each other either through biological kinship or social relationships (), which also indicates that the crypt was owned by this family. However, the sexes of the buried individuals do not correspond to these four persons. This means that the historical sources fail to record a possible rearrangement of coffins in the crypt.

Figure 4. Social and kinship relationships between the individuals buried in the crypt according to historical sources. Burial dates are included in the figure. Figure: Ulla Moilanen and Sofia Paasikivi.

The absence of female bodies in the crypt could suggest that some of the women’s coffins were relocated when new male burials were interred. This is significant new information and possibly reflects the status of women on the island. Seili forms a unique micro-community, different from the usual agrarian and urban parishes in Sweden and Finland in the 18th century. Even though the women buried in the crypt were not patients, the status of women on the island and the patriarchal class society of 18th century Finland probably influenced the way women’s societal value was perceived in life and death on the island. According to the Civic Code of 1734, women could not represent themselves and were required to have a male guardian (Keskinen, Citation2020, pp. 201–2). Nevertheless, widowhood and old age could give women more freedom and power. A widow could be the guardian of her children and continue running the business of her late husband (Keskinen, Citation2020, p. 202). Although young widows were usually expected to remarry, older widows with stable means and respect from their peers could gain more independence and stay unmarried (Keskinen, Citation2020, p. 196). All the adult women buried in the Seili crypt were elderly, and age probably contributed to their burial in the most prestigious place in the church. However, the possible later handling of their coffins may suggest that men were valued over women when deciding who was allowed to remain in the crypt. The Seili community was closely associated with the hospital, and as previously mentioned, women were generally considered prone to both sin and mental illnesses. Although similar attitudes were not uncommon in other places in Finland, they may have been even more prominent in Seili, where the attitudes towards the female patients could have been reflected even in attitudes towards women of higher socioeconomic status.

Given the time between the burials and their removal, the relocation of women from the crypt is interesting. Valborg Vendell, the mother of Samuel Tilenius and the wife of Johan Tilenius and Gottfried Blomberg, was buried in the crypt only a year before the death of her second husband. If we accept that the only female still present in the vault is Maria Cavonia, Valborg Vendell’s remains would have been moved after only a brief period of interment.

Based on the sequence of burials in the historical records, we consider it unlikely that coffin 5 would be Valborg’s. This is because she was the sixth person to be buried in the crypt, and placing her coffin at the back of the crypt would have required the removal of several earlier burials and significant rearrangement. It could be speculated that the rearrangement in the crypt was done the easiest way, by lifting coffins on top of each other (c.f. Mytum, Citation2020, p. 34). The fifth coffin does, however, complicate the identification of buried individuals in the crypt. If burial 5 is male, there is one additional male in the crypt. In this case, the interment of Erik Litander cannot be ruled out.

The possible removal of female coffins raises further questions. Would only a year’s rest in the crypt have been appropriate in Valborg Vendell’s case? The third adult female buried in the crypt according to the records was Helena Didrichsdotter, sister of Gottfried Blomberg. She died 13 years before her brother, but it is possible that her coffin was removed from the crypt earlier, either when Samuel Tilenius or Valborg Vendell were buried. As mentioned earlier, there was no sign of a child’s coffin in the crypt, which leads us to believe that Eva Mattsdotter’s remains were also removed from the crypt. Despite the high mortality rate among children in 18th century Finland, it was not uncommon for them to be buried in a prestigious location, often close to high-ranking clergymen (Lipkin, Niinimäki, et al., Citation2021; Moilanen & Hiekkanen, Citation2020, pp. 42–3). It is interesting that Eva Matdotter’s coffin has been removed from the crypt, as the small coffin would have fit easily on top of the adult coffins. It is unlikely that Eva’s remains were removed from the crypt due to lack of space. Relocation of coffins and human remains is common in post-Medieval burials, and it could have taken place within buildings or sites, or between buildings or towns (Anthony, Citation2015; Paavola, Citation1998; 170–1; Virkkala, Citation1945, p. 24; Väre et al., Citation2021; Weiss-Krejci, Citation2005, p. 168). Although there is no written evidence of relocation of any of the Seili coffins, Eva Mattsdotter may well have been moved to a parent’s grave.

The status of the men buried in the crypt was relatively modest compared to the members of society in larger cities, such as the priests and nobles buried in Turku Cathedral. Locally, however, these three individuals: two men of God and a hospital administrator, would have had considerable power and status in their island community. Although we cannot be sure whether the only female in the crypt is Maria Cavonia, her societal status as a bourgeoisie dowager and her considerable age of 85 may have been reasons to give her a respectable resting place rather than the younger women. Practical reasons must also be considered. The newer coffins were presumably in better condition, and their location closer to the crypt entrance made their removal the easiest solution. However, based on the sequence of deaths and the order of the coffins, it does not seem likely that the decision for removal was solely based on accessibility, otherwise the coffin of Samuel Tilenius would also have been removed. One must also question whether Gottfried Blomberg’s stepson Samuel Tilenius was allowed to remain in the crypt if Samuel’s mother, Valborg, was removed.

Although reburial of remains when the graves under the church floor were full, was not uncommon in the 18th century, the practice was known to cause distress and unhappiness among the relatives of the deceased (Virkkala, Citation1945, pp. 17–8, 23–5). The relatives usually paid a large sum to have their loved ones buried in a prestigious location in the church, and it is reasonable to assume that removing the remains from the crypt to a new, less prestigious location would have caused emotional distress. At a church assembly in Valkeala in 1767, there was a heated debate between the citizens and the clergy; people were upset about the removal of burials from the vault to another location underneath the church floors after only three years of interment (Virkkala, Citation1945, p. 28). Although the general attitude in Post-Medieval Western Europe did not always include a requirement for a permanent burial place (Ariès, Citation1974) and reburying human remains was not uncommon, removal of Valborg Vendell from the crypt only after a year’s rest would not have been considered usual practice.

When considering the motives behind Valborg Vendell’s assumed reburial, it is worth noting that her marriage to Gottfried Blomberg was her second one. In the 18th century, it was common for widows of clergymen to marry the next incumbent, since the house and much of the property were tied to the office and neither the widow nor her children could inherit them. This often led to marriages of convenience, often between younger men and older women, and these marriages were called ‘protecting the ‘widow’ and were often considered unhappy (Vainio-Korhonen, Citation2009, pp. 50–1). Although Valborg Vendell and Gottfried Blomberg were the same age, it is possible that their marriage was more of a financial transaction than an emotional partnership, which may have contributed to the way Valborg Vendell’s remains were treated after the death of her husband, whose status in the community was higher than that of his wife.

Social class was reflected in the death culture in post-medieval Finland. Aristocratic families, the clergy and wealthy merchants required burial places appropriate to their social status, and proper burial was not only an important mourning ritual for the family but played a role in consolidating the social wealth and class system (Ilmakunnas, Citation2019; 139–46, Virkkala, Citation1945, pp. 23–4). In his early research on Finnish cemeteries in the historical period, Ilmari Virkkala notes that the class hierarchy was particularly evident in winter burials; in most of western Finland, there were winter graves (fin. talvihauta), which were usually small wooden buildings next to the fence of the churchyard. People who died in winter and could not be buried in frozen ground waited for spring in these burial houses, and in some cases, the remains of the poorest people were moved directly into a common bone pit (Virkkala, Citation1945, pp. 23–4). According to Virkkala (Citation1945, pp. 23–4), the only way to be buried in midwinter was to be rich and be able to buy a burial plot inside the church. Social classes were as separate in death as they were in life.

The Seili crypt was accessible all year round, and although the space is small, it would have been possible to accommodate seven coffins by stacking them. Therefore, the possible removal of women’s coffins – and perhaps the small coffin of a child – has not been a decision only based on the space available. It seems reasonable that some of the older remains were reburied elsewhere after perhaps ten years, but as mentioned earlier, Valborg Vendell may have been removed only a year after her burial. It is unlikely that this was for purely practical reasons, and the possible removal of the burials of Eva Mattsdotter, Helena Didrichsdotter and Valborg Vendell can be seen as a reflection of how age, sex and gender were an integral part of class society and the culture of death in 18th-century Seili.

Conclusions

The discrepancy between the archived documents and archaeological material is a significant issue not only in the context of individual sites or cases but also in historical archaeology in general. Historical archaeology can explore issues beyond traditional historical research and written records, and this article demonstrates how archived sources can provide an incomplete account of historical events and how archaeological research can complement the picture.

The archaeological documentation suggests that the Seili crypt has been rearranged several times and coffins may have been relocated elsewhere, although there is no mention of such actions in the historical records. Examining these later transfers can reveal, for example, how the dead were treated and valued at different times. It also allows us to approach the idea of a burial place as a permanent, eternal resting place and how real and meaningful this concept was for people in the past. In this case, especially women and children may have been more likely to be removed from the crypt. Thus, the crypt provides an interesting insight to the culture of death and burial in the 18th century Finnish archipelago, and how the culture is linked to class and gender and to the history of the island as a mental hospital run by the clergy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sari Mäntylä from the Finnish Heritage Agency, Tapani Tuovinen from the Metsähallitus Parks & Wildlife Finland, Amelie Alterauge, Anne-Mari Liira, Andreas Ströbl, and Veli Pekka Toropainen for all the valuable help during the research process. The research was conducted with the support of Kuopion Luonnon Ystäväin Yhdistys, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, Turku University Foundation, Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation, and Kone Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ulla Moilanen

Ulla Moilanen is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki. She specializes in burial archaeology and interdisciplinary research of mortuary culture from the Iron Age to the Early Modern Period. Twitter: @umoilanen [email protected]

Sofia Paasikivi

Sofia Paasikivi is a doctoral student at the University of Turku. Her work is focused on bioarchaeological methods, the ethics of working with human remains and the intersections of multidisciplinary archaeology with natural sciences as well as museum studies. [email protected]

References

- Ahlbeck-Rehn, J. (2006). Diagnostisering och disciplinering: medicinsk diskurs och kvinnligt vansinne på Själö hospital 1889–1944. Åbo Akademis förlag Print.

- Alterauge, A., Kellinghaus, M., Jackowski, C., Shved, N., Rühli, F., Maixner, F., Zink, A., Rosendah, W., & Lösch, S. (2017). The Sommersdorf mummies—an interdisciplinary investigation on human remains from a 17th–19th century aristocratic crypt in southern Germany. Plos One, 12(8), e0183588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183588

- Anthony, S. (2015). Hiding the body: Ordering space and allowing manipulation of body parts within modern cemeteries. In S. Tarlow (Ed.), The archaeology of death in post-medieval Europe (pp. 170–188). De Gruyter Open.

- Ariès, P. (1974). Western attitudes toward death, from the middle ages to the present. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Duday, H. (2009). The archaeology of the dead: Lectures in archaeothanatology. Oxbow Books.

- Finnish Meteorological Institute. Climate guide: Temperature. Present climate – 30 year mean values. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://ilmasto-opas.fi/en/ilmastonmuutos/suomen-muuttuva-ilmasto/-/artikkeli/1c8d317b-5e65-4146-acda-f7171a0304e1/nykyinen-ilmasto-30-vuoden-keskiarvot.html.

- Gardberg, C. J., Degerman, H., & Savolainen, I. (2003). Maan poveen: Suomen luterilaiset hautausmaat, kirkkomaat ja haudat. [To the earth: Lutheran cemeteries, churchyards and graves in Finland]. Schildt.

- Helminen, M. (2010). Länsi-Turunmaa (ent. Nauvo) Seili. Kiinteiden muinaisjäännösten inventointi ja Seilin Kirkkoniemen koetutkimukset 2009. Seilin saaren arkeologia –hanke. [West-Turunmaa (formerly Nauvo) Seili. Survey of archaeological sites and test excavation Kirkkoniemi in Seili 2009. Archaeology in Seili -project] [ Unpublished fieldwork report]. Archaeology, University of Turku.

- Helminen, M. (2012). Parainen (ent. Nauvo) Seili. Kohteiden Seili Mielisairaalanpuisto, Seili Skreddarens hus ja Seili Kirkkoniemi (Myllymäki 6) tarkastukset sekä kohteiden Seili Utridarens tomt ja Seili Dårhusen koetutkimukset vuonna 2011. Seilin saaren arkeologia –hanke. [Parainen (formerly Nauvo) Seili. Inspections of Seili Mielisairaalanpuisto, Seili Skreddarens hus and Seili Kirkkoniemi (Myllymäki 6), and test exvacation of Seili Utridarens tomt and Seili Dårhusen in 2011] [ Unpublished fieldwork report]. Archaeology, University of Turku.

- Hoile, S. (2018). Coffin furniture in London c. 1700–1850: The establishment of tradition in the material culture of the grave. Post-Medieval Archaeology, 52(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00794236.2018.1515399

- Ilmakunnas, J. (2019). Säätyläiset ja kuolemakulttuuri 1600-luvulta 1800-luvulle. [Gentry and the culture of death from the 1600s to the 1800s]. In I. Pajari, J. Jalonen, R. Miettinen, & K. Kanerva (Eds.), Suomalaisen kuoleman historia. [History of Finnish Death] (pp. 126–154). Gaudeamus.

- Joona, J.-P. (1997). Haukiputaan kirkon hautakammiot. [Burial vaults in Haukipudas church]. In J. Alakärppä & K. Paavola (eds.). Haukiputaan kirkkohaudat. [Church graves in Haukipudas]. Meteli, 13, 13–18.

- Joona, J.-P., & Ojanlatva, E. (1997). Keminmaan kirkon kuoriosan hautakammiot ja hautaukset. [Grave vaults and burials in the choir of Keminmaa Church]. Meteli, 14, 32.

- Joona, J.-P., Ojanlatva, E., Paavola, K., Pöppönen, S., Tikkala, E., Tuovinen, O., & Alakärppä, J. (1997). Kempeleen kirkkohaudat. [Church graves in Kempele]. Meteli 11. University of Oulu.

- Karsten, P., & Manhag, A. (2018). Antikvarisk rapport gällande undersökningen av biskop Peder Winstrups kista och mumifierade kvarlevor. [Report on the examination of the coffin and mummified remains of Bishop Peder Winstrup], Lund University.

- Keskinen, J. (2020). Porvarisperhe ja sen monimuotoisuus 1700-1800-lukujen Porissa. [The bourgeois family and its diversity in Pori in the 1700s–1800s]. In J. Ilmakunnas & A. Lahtinen (Eds.), Perheen jäljillä - Perhesuhteiden moninaisuus Pohjolassa 1400–2020. [Tracing the family – the diversity of family relations in the Nordic countries 1400–2020] (pp. 177–212). Vastapaino.

- Kiiskinen, K., & Aaltonen, L. (1992). Hautauskulttuuri Suomessa: Suomen hautaustoimistojen liiton 50-vuotisjuhlakirja. [Funeral culture in Finland: 50th anniversary book of the Finnish association of funeral services]. Suomen hautaustoimistojen liitto.

- Kjellberg, J. (2015). To organize the dead – stratigraphy as a source for typology in post-medieval burials. META Historiskarkeologisk tidskrift, 163–171.

- Korhonen, A. (1929). Turun tuomiokirkko vv. 1700–1827. [The Cathedral of Turku between 1700–1827]. Turun Historiallinen arkisto 3.

- Kuokkanen, T., & Lipkin, S. (2011). Hauta‐asut elämän kuvaajina – Oulun Tuomiokirkon kuolinpuvuista. [Funerary costumes as portraits of life – The funeral costumes at Oulu Cathedral]. In J. Ikäheimo, R. Nurmi, & R. Satokangas (Eds.), Harmaata näkyvissä. Kirsti Paavolan juhlakirja [Festschrift for Kirsti Paavola] (pp. 149–163). Waasa Graphics.

- Leccia, C., Alunni, V., & Quatrehomme, G. (2018). Modern (forensic) mummies: A study of twenty cases. Forensic Science Internationall, 288, 330.e1–330.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.04.029

- Liira, A.-M. (2022). Parainen Nauvo Seilin kirkko 2021. Osteological analysis report. Finnish Heritage Agency.

- Lipkin, S., & Kallio-Seppä, T. (2020). Introduction: Studying under-floor church burials in Finland––Challenges in stewarding the past for the future. Historical Archaeology, 55(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/S41636-020-00267-Z

- Lipkin, S., Niinimäki, S., Tuovinen, S., Maijanen, H., Ruhl, E., Niinimäki, J., & Junno, J.-A. (2021). Newborns, infants, and adolescents in postmedieval Northern Finland: A case study from Keminmaa. Historical Archaeology, 55(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-020-00265-1

- Lipkin, S., Ruhl, E., Vajanto, K., Tranberg, A., & Suomela, J. (2021). Textiles: Decay and preservation in seventeenth- to nineteenth-century burials in Finland. Historical Archaeology, 55(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-020-00270-4

- Moilanen, U. (2021). Variations in inhumation burial customs in Southern Finland (AD 900–1400): Case studies from Häme and Upper Satakunta. Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, Hum. B, Tom 555. University of Turku.

- Moilanen, U., & Hiekkanen, M. (2020). Atypical burials and variations in burial customs in the church of Renko, Finland. In T. Äikäs & S. Lipkin (Eds.), Entangled beliefs and rituals: Religion in Finland and Sápmi from stone age to contemporary times. Monographs of the archaeological society of Finland 8 (pp. 35–53). Archaeological Society of Finland.

- Museum church of Seili. (2013). Erik Litander. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://seilinmuseokirkko.blogspot.com/2013/08/erik-litander.html.

- Mytum, H. (2017). Mortuary culture. In C. Richardson, T. Hamling, & D. Gaimster (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of material culture in early modern Europe (pp. 154–167). Routledge.

- Mytum, H. (2020). Burial crypts and vaults in Britain and Ireland: A biographical approach. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Archaeologica, (35), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.18778/0208-6034.35.02

- The National Archives of Finland, Rymättylä, Church records of deaths and burials 1716–1785.

- The National Archives of Finland, Seili, Church records of deaths and burials 1723–1840.

- Niitemaa, T. (2010). Genius aboensis: Tarinoita Turun yliopistosta. [Genius aboensis: Stories from the University of Turku]. I. Kirja-Aurora.

- Norrgård, S., & Helama, S. (2019). Historical trends in spring ice breakup for the Aura River in Southwest Finland, AD 1749–2018. The Holocene, 29(6), 953–963. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683619831429

- Núñez, M., Paavola, K., & García-Guixe, E. (2008). Mummies in northern Finland. In P. A. Peña, C. R. Martin, & M. Á. R. Rodríquez (Eds.) Mummies and Science, World Mummies Research, Proceedings of the VI World Congress on Mummy Studies (pp. 123–128). Academia Canaria de la Historia.

- Núñez, M., Väre, T., Costas, O. L., & Tranberg, A. (2021). Conditions contributing to the natural mummification of corpses deposited below north Finnish churches. Canarias Arqueológica, 22, 432–436.

- Nurminen, N., Lipkin, S., Kuha, A., Väre, T., Marjakangas, S., Niskanen, M., & Junno, J. (2018). Experimental mummification in northern Finland. Fennoscandia Archaeologica, XXXIV, 146–151. http://www.sarks.fi/fa/PDF/FA34_146.pdf

- Oulu Provincial Construction Archives. Jäljennökset Seilin kirkon, kruununmakasiinin ja kellotapulin piirustuksista [Copies of the drawings of the Seili Church, the Grain Storage and the Belfry] (1858–1972), 39:14.

- Paavola, K. (1998). Kepeät mullat: Kirjallisiin ja esineellisiin lähteisiin perustuva tutkimus Pohjois-Pohjanmaan rannikon kirkkohaudoista [Sit tibi terra levis: The church graves of the Northern Finnish coastal area according to written and material sources]. Acta Universitatis Ouluensis B Humaniora 28. University of Oulu.

- Peacock, E. E., Tegnhed, S., Maltin, E., & Turner-Walker, G. (2020). The Gällared shroud – a clandestine early 19th century foetal burial. Archaeological Textiles Review, 62, 152–163.

- Pesonen, P. (2016). Parainen Seili Kirkkoniemi. Historiallisen ajan hospitaalin ja hautausmaan arkeologinen kaivaus 25.7. –4.8.2016. [Parainen Seili Kirkkoniemi. Excavation of historical hospital and graveyard 25.7.–4.8.2016] [ Unpublished Fieldwork Report]. Finnish Heritage Agency.

- Peyroteo Stjerna, R. (2016). On death in the mesolithic. Or the mortuary practices of the last hunter-gatherers of the South-Western Iberian Peninsula, 7th–6th Millennium BCE. Occasional papers in archaeology 60. Uppsala University.

- Pylkkänen, K. (2012). Finnish psychiatry—past and present. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 66(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2011.590604

- Räikkönen, J., Grénman, M., Rouhiainen, H., Honkanen, A., & Sääksjärvi, I. E. (2021). Conceptualizing nature-based science tourism: A case study of Seili Island, Finland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1948553

- Rugg, J. (2010). Defining the place of burial: What makes a cemetery a cemetery? Mortality, 5(3), 259–275. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1080/713686011

- Ströbl, A. R. (in press). Zwischen Tradition und Mode – Zur Typologie neuzeitlicher Holzsärge. Das Altertum, (67), 71–80.

- Turunen, S., & Achté, K. (1976). Seilin hospitaali 1619–1962. [Hospital of Seili 1619–1962]. Käytännön lääkäri no 1. Leiras.

- Vainio-Korhonen, K. (2009). Suomen herttuattaren arvoitus: Suomalaisia naiskohtaloita 1700-luvulta. [The mystery of the duchess of Finland: Fates of Finnish women in the 1700s]. Edita.

- Valk, H. (1994). Neighbouring but distant: Rural burial traditions of Estonia and Finland during the Christian period. Fennoscandia Archaeologica, XI, 61–76.

- Väre, T., Lipkin, S., Suomela, J. A., & Vajanto, K. (2021). Nikolaus rungius: Lifestyle and status of an early seventeenth-century northern Finnish vicar. Historical Archaeology, 55(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-020-00268-y

- Väre, T., Núñez, M., Niinimäki, J., Junno, J.-A., Niinimäki, S., Vilkama, R., & Niskanen, M. (2015). Fame after death: The unusual story of a Finnish mummy and difficulties involving its study. Thanatos, 2, 68–97.

- Väre, T., Tranberg, A., Lipkin, S., Kallio-Seppä, T., Väre, L., Junno, J., Niinimäki, S., Nurminen, N., & Kuha, A. (2020). Temperature and humidity in the base-floors of three northern Finnish churches containing 17th–19th-century burials. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Archaeologica, (35), 189–215. https://doi.org/10.18778/0208-6034.35.12

- Virkkala, I. (1945). Suomen hautausmaiden historia. [History of Finnish cemeteries]. WSOY.

- Vuorinen, I. (2020). Seili: Elon kirjoa ( Ensimmäinen painos). Kustannus Aarni.

- Weiss-Krejci, E. (2005). Excarnation, evisceration, and exhumation in medieval and post-medieval Europe. In G. F. M. Rakita, J. Buikstra, L. A. Beck, & S. R. Williams (Eds.), Interacting with the dead: Perspectives On mortuary archaeology for the new millennium (pp. 155–172). University Press of Florida.