ABSTRACT

In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, people can choose to donate their bodies post-mortem to Medical School Anatomy Units. The body donation (BD) process is facilitated by anatomy unit staff (AUS). However, little is known about the extent and nature of AUS work with families, including when a body cannot be accepted. To address this gap, this paper draws on data from an ethnographic study, including a survey of 15 anatomy units (AUs) in England and Northern Ireland, a case study of one AU, 20 semi-structured interviews with 31 AUS and document analysis. We reveal the number of bodies (878) that are refused across AUs and examine how AUS deal with refusals. We argue that activities around refusals constitutes ‘over and above’ work for AUS, as it goes beyond their expected role. We suggest that this is done out of a duty of care, and is related to the discomfort of refusing the BD gift. Attention is given to the ‘over and above’ work of the AUS which allows for an exploration of gift relationships and emotion management in a new arena. We conclude with recommendations to address the lack of recognition and training around AUS refusal work.

Introduction

This paper explores the work of Medical School Anatomy Unit staff (AUS) when donor bodies cannot be accepted for body donation (BD). BD, also known as anatomical bequeathal or anatomical gifting, is the voluntary donation of the body after death for the purposes of medical and health professionals education and research (Cornwall & Stringer, Citation2009). When a body is donated to a Medical School Anatomy Unit in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, it usually remains there for three or more years, thus disrupting ‘normal’ post-death processes (where a death is closely followed by a funeral). AUS facilitate and manage the process of BD and are the initial and continuing point of contact for prospective donors and their families (including significant others who are not related to the donor). However, little is known about the extent and nature of AUS work with families, including the work they do when a body cannot be accepted post-mortem. This paper seeks to address this gap: it will reveal the number of bodies refused across anatomy units (AUs) in England and Northern Ireland and examine what AUS do to deal with these refusals and manage the emotions of families through the refusals process.

In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, donated bodies are seen as an essential resource for teaching anatomy to medical students (Aziz et al., Citation2002; Black, Citation2018; Cornwall, Citation2011; Cornwall & Stringer, Citation2009). BD relies on the willingness of the public to donate their body after their death (Bolt et al., Citation2010; Cornwall et al., Citation2012; Smith, Citation2018). As facilitators of this process, AUS have the daily task of ensuring the smooth-running of the BD process for the families of donors and non-donors (those unable to donate). This is especially pertinent given the fact that BD often runs in families, meaning a good experience may help generate future donations (Bolt et al., Citation2010; Cornwall et al., Citation2012).

There is substantial literature on BD globally including research around: the work that AUS do with medical students for example, when introducing them to anatomical dissection, including a focus on the management of students’ emotions (Black, Citation2018; Goss et al., Citation2019; Hildebrandt, Citation2010; Prentice, Citation2013); body donor monuments and thanksgiving services (Bolt, Citation2012; Strkalj & Pather, Citation2017); ethical considerations (Habicht et al., Citation2018; Hildebrandt & Champney, Citation2020; Jones & Whitaker, Citation2009); practice recommendations (Jones, Citation2015); donor information, donor attitudes and motivation (Cornwall et al., Citation2018; Zealley et al., Citation2021); and, historical accounts (Laqueur, Citation2015; Richardson, Citation1988; Tarlow, Citation2011). However, there is scant research on the work of those who facilitate body donation, particularly the work AUS do with families of donors and non-donors. Currently, there are also no standardised working guidelines for AUS in the UK around refusals (although other areas of BD practice have been addressed and debated in the literature) (e.g Human Tissue Authority [HTA] Citation2017, Citation2019; Jones, Citation2015; Riederer, Citation2016).

The act of BD is often conceptualised as a ‘gift’; for example, the UK’s Human Tissue Authority (HTA, the organisation that regulates the use of human tissue and organs), describes BD as ‘a valuable gift’ where the ‘[…] donation will become an important resource for training healthcare professionals or for research’ (Human Tissue Authority [HTA], Citation2022). Some of the existing research on BD also draws on gift theory to understand the giving of donor bodies and how these are honoured through memorial services and body donor monuments, such as benches, plaques, and memorial statues (Bolt, Citation2012; Strkalj & Pather, Citation2017). Bolt (Citation2012) hypothesised that body donor monuments were an act of reciprocity by anatomy staff who felt a duty to give back to the donor families. Within the related field of organ donation (OD), health professionals facilitating donation have been conceptualised as ‘guardians of the gift’ as they ‘decide, oversee, facilitate and handle the exchange of organs in their daily work’ (Jensen, Citation2017, p. 113). Whilst this work has provided important insights into gifting within donation and the role of staff in facilitating the acceptance and reciprocation of the gift, we want to pose the question about what happens when a ‘gift’ – in this case, the whole body – is refused, and the implications this might have for families and the work of AUS.

Gift exchange theory was developed from Marcel Mauss’ (Citation1990) observations of potlatch (feasts given as gifts) in the Pacific Northwest, where giving, receiving and the obligation to reciprocate were central to the interaction. Gift exchange theory posits a tacit social contract to accept and reciprocate a gift. According to Mauss (Citation1990), the refusal of a gift displayed the proposed receiver’s fear that they could not reciprocate. Subsequently, they lost power and dignity. Drawing on Mauss (Citation1990) theory, Goldman-Ida (Citation2018, p. 341) argued that the social bond between giver and potential receiver that was created by gift giving was disrupted by the refusal as ‘[…] to refuse to receive is to reject the social bond […]’. In their work on OD and transplantation in the US, Fox and Swazey (Citation1992, p. 40) asserted that there was a moral and psychological burden caused by the unreciprocated gift, what they termed the ‘tyranny of the gift’. On these bases, to refuse the gift of a BD could then have multiple implications, not only for relatives of the deceased, but also for those staff who facilitate this process and, more broadly, the social contract involved in BD.

Whilst little is known about refusals in BD, research in the field of deceased OD has documented related issues, although this is mainly focused on what happens when families refuse consent for donation. This research has considered the ethical issues around family decision making processes (Bastami et al., Citation2016; de Groot et al., Citation2015; de Moraes & Massarollo, Citation2008; Jacoby & Jaccard, Citation2010; Sque et al., Citation2018) and families overruling the patient’s decision to donate (Morgan et al., Citation2018; Shaw & Elger, Citation2014; Shaw et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Evidently, refusals in the context of OD are a complex issue, and staff have difficult roles as mediators. As Sharp (Citation2006, p. 75) put it: ‘[…] procurement staff walk a tightrope between respecting the emotional fragility of kin and remaining true to the ideological premises that drive their work’. There is also an emerging field which has documented family experiences when OD cannot proceed. For example, Taylor et al. (Citation2018) research on non-proceeding donation after circulatory death (DCD) found multiple harms for consenting family members such as an inability to honour their loved one’s wishes and make sense of the organs going to waste. In Taylor’s study, non-donation was due to institutional requirements around DCD, such as the patient not dying within the allotted time. This type of non-donation is outside of the families’ control. It has similarities with BD refusal, which can be due to medical and non-medical institutional reasons, such as lack of storage facilities. Non-donation in BD could have similar harms for families, which would have implications for AUS. However, BD differs from OD in that it requires the agreement of the donor prior to death and is not agreed on by the family post-mortem.

Considerations of the emotional aspects of such work have been explored in research on OD coordination (Jensen, Citation2017; Sothern & Dickinson, Citation2011). For example, Jensen’s work (Jensen, Citation2017) on transplant coordinators in Denmark applied gift and emotion theory to posit health professionals involved in OD and transplantation as ‘guardians of the gift’ where they take on its emotional burdens and face difficult decisions in their daily work. The field of inquiry into emotion stems from the seminal work of Hochschild (Citation1979, Citation1983) who used the term ‘emotional labour’ to describe ‘the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display; emotional labour is sold for a wage and therefore has an exchange value’ (Hochschild, Citation1983, p. 7 – emphasis in original). Critiquing Hochschild’s (Citation1983) emotional labour theory, Bolton (Citation2000) developed a multidimensional typology of emotion management (EM). She differentiated EM into four types: prescriptive; pecuniary; presentational; and philanthropic, which range from that which is commissioned by managers according to organisational rules of conduct, to that which is given as a gift and is chosen to be completed by staff (Bolton, Citation2000).

The purpose of this paper is to understand what happens when a prospective donated body is refused and the implications this might have for families and the work of the AUS. In what follows, we draw on data from a wider ethnographic study on BD to uncover the daily realities of AUS work around refusals. We will reveal the number of bodies that are refused each year in England and Northern Ireland AUs and examine the nature and extent of AUS work when the gift of the body is refused.

Methodological and ethical considerations

This paper is based on data from an ethnographic doctoral study which explored what happens around BD, with a focus on the work AUS do with the families of donors.

The study received ethical approval by the Hull York Medical School ethics committee (reference number: 1611). All participant information and identifying features of the AUs have been anonymised and pseudonyms assigned to participants. ZM conducted fieldwork between 2015 and 2019, which encompassed a survey and semi-structured interviews with AUS, an ethnographic case study of one AU, participant observations of AUS at thanksgiving services, and document analysis of AU documentation. A practical sampling approach (Henry, Citation1990) was taken, aiming to include all AUs in England, Northern Ireland and Wales and their AUS within the study. However, the lack of response from AUs in Wales resulted in the study only including AUs from England and Northern Ireland. In total, 18 AUs were sent a letter of invitation to take part in the research study, and a response was received from 17. Of the 17 AUs who responded to the study invitation, 15 completed the survey and 31 AUS across 14 AUs completed at least 1 in-depth semi-structured face-to-face interview, group interview or telephone interview (20 interviews with 31 participants with interviews lasting between 34 and 232 minutes). ZM also conducted participant observations during tours 7 AUs gave when ZM visited the units for interviews. A 6-month ethnographic case study of 1 UK AU with 7 AUS was used to contextually situate the issues raised by the survey and interviews. ZM conducted non-participant observations of the day-to-day occurrences at the unit, such as participating in staff activities and discussions, attending meetings, visiting the crematorium, and eating lunch with staff. This unit was selected as it was considered exemplary of AUS work by the HTA (identified through the HTA AU inspection reports). These observations were recorded in the form of fieldnotes. The data were analysed iteratively, and key themes emerged from the fieldwork which shaped the data collection process (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Mason, Citation2012). Thematic analysis was used to analyse the final dataset (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Mason, Citation2012). An ethnographic approach to analysis meant that the data set was analysed holistically alongside understandings from the literature and wider social and institutional contexts (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007).

Results

In this section, we reveal the extent of refusals in body donation (BD) in England and Northern Ireland and the extensive work of Anatomy Unit staff (AUS) when dealing with refusals.

AUS roles

The main roles within the AU we focus on are the Bequeathal Secretary (BS), Mortuary Manager (MM) and Designated Individual (DI). BSs are individuals who have many roles within the AU including the facilitation of BD, whereby they are the initial and continuing point of contact for prospective donors and families. The MM is the individual that runs and coordinates the storage, preservation, and use of the bodies for teaching and external courses. DIs, who are usually (but not exclusively) academic staff, ‘have a legal duty to ensure that statutory and regulatory requirements are met. They are responsible for supervising licenced activities and ensuring suitable practices are taking place’ (HTA, Citation2019).

Refusals

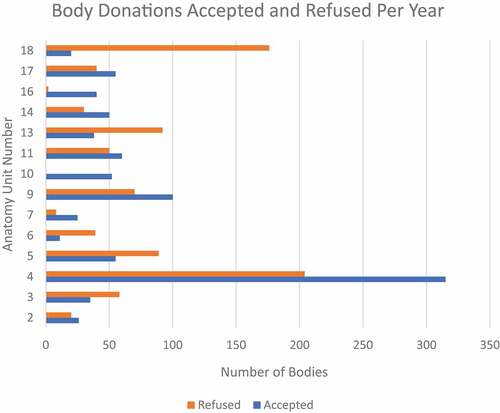

Before this study the number of refusals for BD in England and Northern Ireland was unknown. In the study, survey of anatomy units (AUs) we uncovered that the number of refusals for BD is surprisingly high (reasons for which we describe below). Across all 15 UK AUs that took part in the survey in 2016, AUS reported that out of 1,760 bodies offered on average each year across the units, almost half of these (878 bodies) were refused. presents the number of bodies which were accepted and refused per year across all 14 units. The maximum and minimum number of bodies accepted and refused have been calculated as some units provided an annual range. illustrates the numbers of bodies accepted and refused from each AU. Of the 15 AUs that completed the survey, 14 out of 15 units responded to the question about how many bodies were accepted per year, and for the question regarding how many bodies are refused per year, 13 out of 15 units provided answers. Considering this large number of refusals, we explore the extensive AUS work involved in refusals. Before doing so we outline the initial and expected work involved in refusing bodies to contextualise family reactions to these refusals and the ‘over and above’ work AUS do in response.

Figure 1. Body donations accepted and refused per year across 14 anatomy units in England and Northern Ireland.

Table 1. Total number of bodies accepted and refused per year across 14 anatomy units in England and Northern Ireland.

Initial and expected work around refusals

From ethnographic fieldwork and interviews with AUS the initial and expected work around BD refusals was as follows. Upon the death of the individual who had signed up to be a body donor, the family or executor (the person dealing with the estate of the deceased) phone their local AU to inform them of the death of the potential donor. The AUS then check the cause of death and where the body is currently residing. There are criteria for acceptance outlined in the HTA (Citation2017) guidelines for AUs which are based on safety and the need for bodies to be, what is described as, anatomically ‘normal’ for teaching. The main reasons for non-acceptance of a body include if: a Coroner’s post-mortem is necessary; there is a transmissible infection, such as tuberculosis, HIV, MRSA, or hepatitis; an individual dies abroad; or if an individual is obese. However, in some cases, there are non-medical institutional reasons why the body cannot be accepted, for example, a lack of storage facilities, because the AU was closed, or because of staff shortages. With the information on the potential donor’s cause of death and pre-existing conditions, and considering any institutional issues, the AUS can decide whether they can accept the body. When the AU accepts a body they pay for the funeral, however, if the body is refused it remains the responsibility of the next-of-kin and they pay for the funeral. This is made clear to the potential donor when signing up to donate their body. The potential donor is also encouraged by AUS to discuss their plan for donation with their family prior to signing donation documents. In this respect, the interaction at this initial phone call stage should be generally short and requires seemingly straightforward work from the AUS. However, as we will demonstrate, in practice, this was not always a linear process; families reacted in a wide range of ways, which caused extra work for staff.

Family reactions to refusals

During interviews, the AUS described a range of reactions from families to the refusal of their relative’s body for donation, from relief to upset.

In some cases, AUS reported that families were relieved by the refusal and were pleased that the body could not be accepted. On these occasions, families accepted the refusal and continued with their own funeral plans.

AUS interpreted the families’ relief in two ways. First, that families were relieved the body could not be donated because they disagreed with their loved one’s wish. One bequeathal secretary (BS) outlined that ‘[…] sometimes they’re relieved because they weren’t happy with it [body donation]’. (Lynne, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 4). Some families found it difficult to accept their relative’s wish due to personal or religious reasons, such as not wanting their loved one to be dissected or their religion not accepting BD. It was also likely that the potential donor had discussed the possibility of refusal with their families prior to death.

The second way this relief was understood was rooted in the family wanting ‘normal’ post-death arrangements, such as a funeral, memorial service, plaque, or bench. Another BS speculated:

[…] for some people they may have been carrying out the wishes of their loved one because that was their wish, but haven’t really got their heads around the idea of body donation and weren’t really up for the idea of not having a normal funeral so they make the call [to the AU] (laughs), I think hoping deep down inside that we’re not able to accept because they just want things to be normal, and so sometimes you can hear a sigh of relief if you’re not able to accept.

(Nikki, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 13)

However, in their interviews AUS described this relief reaction from families as being uncommon; in their experience, most families were upset when they were told that their relative’s body could not be accepted, and this was sometimes angrily expressed, for example, they raised their voices and cursed or blamed the AUS for not accepting their relative’s body:

[…] sometimes you get them, and they are really angry, especially if you have to turn down, […] they are just reacting out of emotion really. Yeah, they might be really mad that we can’t accept them.

(Charlotte, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 11)

Charlotte perceived that this anger was an expression of extreme emotion which helped her to comprehend the family’s behaviour. However, for most AUS this anger was extremely difficult to receive:

[…] there are times that I’ve been quite upset, moved by it, umm I found it very difficult when we have to decline, and the family are upset, that always bothers me.

(Alice, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 9)

[…] if you had to turn one down and they took it badly […] sometimes it’s more sad […]

(Annie, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 17)

This upset and anger was interpreted by AUS to be for two main reasons. First, AUS understood that some families felt that they had been let down by the AUS as they believed erroneously that there was a guarantee of acceptance when their loved one joined the BD register. It appeared then that the AUS had thus reneged on the donation ‘contract’, and it was the AUS that received the blame. One BS described a case where several upset siblings contacted her as they believed that the AU had ‘[…] let [their mum] down badly by not accepting when the time came’:

[…] even though we try to be as clear as possible that there’s no guarantee, they feel that when their mum or dad or whoever it is registered with us that somehow, we made a promise that we would accept them when the time came […]. I had different siblings on the phone (laughs) sort of upset in different degrees because they felt that we had entered into a contract with mum by adding her to our register […]

(Nikki, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 13)

As a BS, Nikki was the individual who bore the brunt of the families upset due to her rejection of the donation (on behalf of the AU). Second, AUS perceived that some family members’ reactions to the refusal were due to the financial implications they would incur because they would have to cover the funeral costs. This is explained to potential donors when they consent, and they are advised to inform their family members. It was evident, however, that in some cases families did not know of, or had forgotten, the possibility of non-acceptance and were faced with financial implications for which they were unprepared. Steve, a mortuary manager (MM), explained:

[…] sometimes you can get some relatives who are very, very disappointed who say, I don’t know what I’m going to do then, or I don’t know how I’m going to pay for a funeral […]

(Steve, Mortuary Manager, unit 3)

This is linked with the aforementioned assumption made by families that the BD contract will not be reneged on by the AU.

The spectrum of over and above work following refusals

As most families were upset by the refusal, the majority of respondents explained how they felt compelled to complete extra work to make refusals easier for the families. A Designated Individual (DI) at one AU revealed:

[…] over and above the job description it’s just going into, it’s delving into the personal interaction that is over and above what you would be expected to do [in the case of refusals] […]. So, in a sense there’s more a listening ear, a counsellor type role, which is definitely not something that is in our job descriptions at all.

(Anthony, Designated Individual, unit 2)

This ‘over and above’ work, was seen as such because it was not part of their formal job role. AUS chose to complete such work in response to family reactions. There was a spectrum of ‘over and above’ work ranging from initial mitigation work, that took less time and effort to complete, to referral work, which took much time and effort. Initial mitigation work involved the AUS taking time to reassure and explain the situation to family members who expressed their upset/anger at the donation refusal. For example, Nikki discussed how she successfully navigated situations where families were upset by the refusal:

[…] if you can navigate that [the families upset in response to the refusal] successfully, as in they appreciate and understand that you have done everything that you can do, and you’ve assured them that they’ve done everything that they can do by carrying out their loved one’s wishes, and they feel sort of content with that and that’s quite an important process really.

(Nikki, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 13)

Nikki describes her practice of taking time to explain to the families and assure them that the AU had done everything they could to accept the body, which often resulted in families being content with the refusal.

Similarly, Charlotte described her approach of responding calmly to families, breaking down the reasons for the refusal to assist with the family’s acceptance of the situation.

[…] I guess you’ve just got to be calm and reasonable really and not get upset about it […] as long as you’ve got a valid reason for it and you can explain it to them then they’re usually, they usually accept it even though they might not be very happy about it. (laughs).

(Charlotte, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 11)

In some cases, MMs were called on if BSs or technicians did not feel they could deal with the situation. This usually happened if the family were perceived as being very angry or upset at the situation. In these cases, the MM would be asked to take the call or follow-up with the family. For example, Sean, a MM, explained:

[…] sometimes I end up having to speak to a relative that might be upset about [the refusal] just to explain why fully so that they understand that we just can’t accept everyone […]

(Sean, Mortuary Manager, unit 16)

Cases where families were extremely upset took extra staff, time, and effort to manage. Usually, the MM would not be involved in the initial refusal conversations as their main duties lie in running and coordinating the storage, preservation, and use of the bodies for teaching and external courses. However, they often became involved in the refusal conversations with distressed families with the aim of reducing the upset refusal caused.

AUS therefore went ‘over and above’ to take the time to verbally mitigate these situations where the family were upset and would not initially accept the refusal. It was clear that this work took extra time and effort, detracted from, or added additional duties to their role and was not expected of them.

In addition, it was evident that some AUS undertook additional work, beyond that of mitigation, by referring the deceased to another AU which might be able to accept the body. This ‘referral work’ was a frequently used method by the AUS with the aim of reducing refusals and thus family upset. Monica, a technician, declared:

Yes, refusals are the most difficult and the referral lessens the blow [of the refusal on the families].

(Monica, Technician, unit 2)

Referral work required varying levels of time and effort from the AUS, and we characterise this work as occurring at three levels in order of increasing time and effort, namely: (1) a hybrid approach, where there was a shared onus between the family and the AUS, (2) the onus was on the AUS, or (3) additional referral work where the AUS sought external donation options. This referral work was not required or practical for the AUS to complete as AUs were successfully meeting their annual body number targets without referral work. Therefore, it was clear that the motivation for referral work was not to reduce the number of refusals, but to mitigate the upset that refusals caused for the families of potential donors.

The first level of referral work, we characterise as a hybrid approach, where the family and the AUS shared the job of seeking referral in response to the family reaction. However, AUS were balancing this with the demands on their time. For example, in the ethnographic case study ZM observed that both the MM and the families rang AUs to seek referral. During one phone call when the AU could not accept a body, the MM arranged with the family member that they would ring several medical schools while he rang the others. This MM was balancing the time constraints of needing the body to be accepted within 5 days after death alongside his work duties by handing over some of the work to the family. Similarly, in the ethnographic case study ZM observed that the BS received a voicemail from a relative whose mum had passed away, enquiring whether any other medical schools could accommodate her as their local medical school could not. Unfortunately, on this occasion the BS, on returning the call, explained that the AU was at capacity, and they could not accept.

The second and most common level of referral work was when the AUS went out of their way to seek referral themselves. This level of referral work most often occurred when refusals were for non-medical institutional reasons. For example, if the original AU did not have enough storage space or AUS to embalm the body. In these circumstances, the AUS felt that the onus was on them to seek referral. Ben, a DI, highlighted:

[…] we work really hard if we aren’t able to accept for any other reason that may be a general medical criterion which institutions would be reluctant to proceed on, we work hard to still place our donors in institutions, Jo [the BS] or I will ring around other institutions.

(Ben, Designated Individual, unit 18)

Similarly, Dawn, a BS, confirmed that if the refusal was due to a logistical reason at the AU, then AUS made extra effort to refer the body.

If we are not accepting because the DR [Dissection Room] is closed for any reason, then we nearly all [AUS across AUs] try and muck in and help each other out.

(Dawn, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 10)

Here, Dawn describes how BSs from multiple AUs would often work together to find referral options for such individuals.

However, there were also certain medical conditions that were not accepted at some AUs yet were at others, such as Alzheimer’s Disease. In such cases staff sought referral even though it was unlikely that the body could be referred. As Ben, a DI, explained:

If there is a chance I would normally call [unit 9] and describe to them that there’s a medical criteria issue for us, are they embarking for any specific fresh frozen courses where that [medical issue] might not have an impact. So, there’s always a small chance that we might be able to refer you even though the medical criteria are not right for our purposes.

(Ben, Designated Individual, unit 18)

As an extension to the referral work that most AUS completed, some AUS also did referral work when the body could not be referred for BD. For example, when a body could not be accepted to unit 10 for medical or non-medical reasons, the BS, Dawn, referred to a brain bank with which she had a referral relationship.

I do a lot of referral work to say the brain bank and I will explain to the family, ‘look it’s not the same as full body donation, […] but if you are interested here is the number of the research nurse down there’. I use that particular project because I know it’s ongoing and they’re not going to close their doors.

(Dawn, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 10)

This referral relationship with the ‘brain bank’ required effort to sustain but was a way some AUS managed refusals. Many AUS also suggested external research studies that may accept the refused bodies. AUS were doing this work in part to secure the reputation of the AU but the degree and extent of it meant they did ‘over and above’ work.

Reasons AUS completed ‘over and above’ work

There were several reasons why AUS chose to complete their ‘over and above’ work. These we characterise as including: a duty of care for the potential donor and their families, which provided staff with job satisfaction, and the emotional impact the refusal had on the AUS.

In an interview, Ben and Jo, a DI and BS, explained this ‘over and above’ work and why they performed it:

Ben: […] it’s just a duty of care to help, not just the donor but also the next-of-kin and the families, to place, to place our donors elsewhere if possible.

Jo: Yeah that’s part of the job really, we’ve made that part of the job, it wasn’t necessary - it’s not in our job description to do it, it’s not written anywhere, but that’s part of doing the job well and going home at the end of the day and thinking yep we couldn’t place that donor but we tried, we spoke to the family, they understood and we’ve closed that one off.

(Ben, Designated Individual, and Jo, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 18)

These AUS recognised that they were voluntarily doing ‘over and above’ work by detailing how they have made it ‘part of the job’ despite it not being necessary for their role. It was clear that AUS chose to perform this work out of a ‘duty of care’ to the donor and their families. They felt that they owed the family to fulfil the BD.

In the excerpt above, Jo highlights that completing this work also gives her job satisfaction and enjoyment; this was ‘part of doing the job well’ and clarified why AUS voluntarily completed such work. Jo also highlighted that doing this allows her to leave work at work and establish the closure of the BD relationship between the AUS and the families.

AUS also described how they would experience upset in response to a family’s distress at a refusal. This was because they felt that they had let the family down by reneging on the perceived BD contract, even though it was expected that the family be prepared for the refusal.

That [refusing] is awful actually. I hate having to tell someone we can’t accept […]

(Sheila, Bequeathal Secretary, unit 17)

At first I found it quite daunting, it’s quite difficult, the most difficult is when we can’t accept, […] the one time I really found it the most difficult is when they [the donor] hadn’t consented […] then just having to tell the family no we can’t do that for them because they haven’t consented […]

(Monica, Technician, unit 2)

Refusals therefore not only had an emotional impact on the families, but they were also distressing for the AUS. It was thus understandable why AUS went out of their way to reduce or mitigate refusals since they were personally invested in this process. Like family reactions to the breaking of the perceived BD contract, the AUS also felt uncomfortable rejecting the donation offer even when it was not their fault that they could not accept. Completing work around refusals with non-donor families was described as particularly emotional by AUS as it allowed them to feel that they had salvaged something from a situation which caused both them and the families upset.

Discussion and recommendations

In this paper, we have documented the extent of BD refusals in England and Northern Ireland and the AUS work that goes into dealing with these refusals. We have shown how AUS took on the responsibility of not accepting and receiving the gift and the emotional, moral, and psychological burden this created. With this, we argue that AUS take on a double burden as not only are they refusing a gift, but they are refusing one that is ‘so extraordinary that it is inherently unreciprocal’ (Fox & Swazey, Citation1992, p. 40). Fox and Swazey (Citation1992) refer to this as the ‘tyranny of the gift’. Despite this double burden, AUS had the task of refusing bodies and managing the upheaval this caused while ensuring the process was as positive for the families as possible. We argue that AUS encounter a ‘tyranny of responsibility’ like that experienced by transplant professionals when a transplant is unsuccessful (Jensen, Citation2017, p. 119). AUS made up for the refusal and overcame their double burden as they felt such discomfort in the refusal and not fulfilling their side of this tacit social contract to accept the BD gift (Fox & Swazey, Citation1992; Goldman-Ida, Citation2018; Mauss, Citation1990). We argue that AUS did this by doing ‘over and above’ work.

This ‘over and above’ work, we assert, was given philanthropically by AUS due to a duty of care they felt towards the potential donors and their families. Rather than this work being a prescribed part of their job, AUS completed this work voluntarily as they felt they owed it to the family. We demonstrate that this was because they were emotionally involved in the BD process and refusals had a negative emotional impact on them. We liken this to Testart’s (Citation1998) assertion that acts in reciprocation to the gift were performed because individuals felt that they should.

In the AUS work around refusals, we can see some of the main facets of Bolton’s (Citation2000) philanthropic emotion management (EM), referring to that which is given as a gift and is chosen (our emphasis) to be completed by staff. For example, when AUS went beyond what is expected. They became attuned to the needs of families, felt empathy, and chose to do their ‘over and above’ work; this was over and above the prescriptive or pecuniary types of emotion management work (Bolton, Citation2000; Bolton & Boyd, Citation2003). Furthermore, we argue that AUS ‘over and above’ work was initiated by naturally felt emotions (Randolph & Dahling, Citation2013) rather than the organisational feeling rules which are implicit in Hochschild’s (Citation1983) emotional labour theory. Thus, building on Bolton’s (Citation2000) work, we argue that Hochschild’s term ‘emotional labour’ (Hochschild, Citation1983, p. 7) does not capture the range and comprehensiveness of AUS work as AUS were not prescribed to complete their ‘over and above’ work but nonetheless felt that they should. AUS voluntarily made this a part of their role which elicited job satisfaction, enjoyment (Theodosius, Citation2006), and the ability to leave work at work.

Supporting the AUS: recommendations

The findings indicate the need for guidelines and support for AUS work around refusals, particularly as this work is not formally acknowledged in AUS job descriptions or training. We provide the following recommendations which may be transferrable to the BD community globally:

Formal recognition for AUS work around refusals: this could be done by making refusal work part of AUS job descriptions.

Develop support and training around refusals for AUS: for example, development of training packages for all AUS which provides guidance and support for managing refusals.

Develop a shared database to manage referral work: this could include AU availability and list current external research projects. This would help limit the labour involved in referral work for AUS.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to capture estimates of rates of refusals for BD and look in-depth at AUS work around refusals. The triangulated ethnographic approach and the high response rate (83%) from AUs, meant that we were able to present a comprehensive understanding of refusals and associated AUS work. Our findings may therefore be transferable to other BD contexts outside of England and Northern Ireland. Despite the high response rate, AUs in Wales did not respond to the survey request, which resulted in the study only including AUs from England and Northern Ireland; the response rate to some of the survey questions was also reduced as some AUs did not respond to all questions. This implies that the actual refusal number may be higher than we have presented in our data. The ethnographic fieldwork with AUS gave unique access to their interactions with donors’ families during the facilitation of BD and the navigation of refusals from the perspective of the AUS. However, due to the ethical and logistical difficulties involved in interviewing and observing donor/non-donor families, it was not possible to include this aspect of the relationship in the study. Future research should focus on family experiences of the refusal process.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated in this paper the importance of the AUS’s nuanced ‘over and above’ work around refusals in making the process of BD as positive as possible for families of non-donors. We have also revealed a new arena, around refusals, in the donation literature where gift relationships and philanthropic EM were acted out by AUS. However, there is an evident lack of recognition, support, and training for the AUS’s ‘over and above’ work around refusals; recommendations for this have been made above and discussed elsewhere (Murphy, Citation2019) which provide a practical addition to the BD community. In this paper, we have recognised AUS work around refusals, however, we acknowledge the danger in recognising and routinising this ‘over and above’ work as a formal part of their job role. This could lead to it becoming expected practice and could remove the AUS’s agency and detract from the job satisfaction that AUS received in voluntarily performing this work. This would move this work from being philanthropic EM (Bolton, Citation2000) to emotional labour (Hochschild, Citation1983) as it would become a waged and/or expected part of their role. Moreover, we recognise that this work was done because the AUS wished to and felt that they should; it was the AUS’s way of voluntarily reciprocating the gift of BD. Although this work was done specifically in the context of Medical School Anatomy Units in England and Northern Ireland, we believe that the findings may be transferrable to global BD contexts.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available as participants only provided their consent for the data to be published anonymously in a PhD thesis, academic conference papers and academic journals.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the anatomy unit staff who generously gave their time and made this project possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Z. N. Murphy

Z. N. Murphy, PhD, MAnth, PGCert, is a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at City, University of London in the Division of Health Services Research and Management in the School of Health and Psychological Sciences. She is working on the Consent project funded by NHS Blood and Transplant which explores consent for interventional donor research in organ donation. Zivarna completed her PhD in Human Sciences which explored body donation with a focus on identifying good practice in the interactions between Medical School Anatomy Unit staff and families after donor death. She is interested in the social aspects of body and organ donation; qualitative research methodologies and analysis, particularly ethnographic approaches; public and community engagement, outreach and widening participation; and the display of human remains in museums and archaeological sites.

J. Cooper

J. Cooper, PhD, MA, BA is a Senior Lecturer in the Sociology of Health in the School of Health & Psychological Sciences at City, University of London. Her research focuses on the social and ethical implications of organ donation and transplantation. This includes work on the institutional production of the ‘minority ethnic organ donor’, the ethics-in-practice of Donation after Circulatory Death, and critically examining consent for interventional organ donor research.

P. J. Bazira

P. J. Bazira, MBChB, MSc, EdD, SFHEA, is a Professor of Clinical Anatomy and Medical Education, the Director of the Centre for Anatomical and Human Sciences, and the Designated Individual for the anatomy facilities at Hull York Medical School, UK. He teaches clinical anatomy to medical students, surgical trainees, and doctoral students and his research interests are in clinical anatomy, anatomy education, authenticity in learning and assessment in the context of medical and health professions education, and medical education in general.

T. Green

T. Green, PhD, PG.Cert, BA (Hons) was a Senior Research Fellow at the Hull York Medical School from 2011 until her retirement in 2019. A qualitative researcher with an interest in mixed methodologies, her main academic interest was within the field of death studies. She has published widely on cancer-related topics and natural burial.

J. Seymour

J. Seymour, BSc, MA (Econ), PhD, SFHEA was a Reader in Sociology at Hull York Medical School up to retirement in 2019. Her research investigated family dynamics in health, hospitality and migration. She was a member of the ESRC funded Seminar Series, ”On Encountering Corpses: Political, Socio-economic and Cultural Aspects of Contemporary Encounters with Dead Bodies’ (ES/M002071/1).

References

- Aziz, M. A., McKenzie, J. C., Wilson, J. S., Cowie, R. J., Sylvanus, A. A., & Dunn, B. K. (2002). The human cadaver in the age of biomedical informatics. The Anatomical Record, 269(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.10046

- Bastami, S., Krones, T., & Biller-Andorno, N. (2016). Relatives’ experiences of loved ones’ donation after circulatory and brain death. A qualitative inquiry. Bioethica Forum, 9(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.24894/BF.2016.09004

- Black, S. (2018). All that remains: A life in death. Penguin Random House.

- Bolt, S. (2012). Dead bodies matter: Gift giving and the unveiling of body donor monuments in the Netherlands. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 26(4), 613–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12010

- Bolt, S., Venbrux, E., Eisinga, R., Kuks, J. B. M., Veening, J. G., & Gerrits, P. O. (2010). Motivation for body donation to science: More than an altruistic act. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger, 192(2), 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2010.02.002

- Bolton, S. C. (2000). Who cares? Offering emotion work as a ‘gift’ in the nursing labour practice. Journal of Advances Nursing, 32(2), 580–586. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01516.x

- Bolton, S. C., & Boyd, C. (2003). Trolley dolley or skilled emotion manager? Moving on from Hochschild’s managed heart. Work, Employment and Society, 17(2), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017003017002004

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Cornwall, J. (2011). The diverse utility of wet prosections and plastinated specimens in teaching gross anatomy in New Zealand. Anatomical Sciences Education, 4(5), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.245

- Cornwall, J., Perry, G., Louw, G., & Stringer, M. D. (2012). Who donates their body to science? An international, multicenter, prospective study. Anatomical Sciences Education, 5(4), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1278

- Cornwall, J., Poppelwell, Z., & McManus, R. (2018). “Why did you really do it?” A mixed‐method analysis of the factors underpinning motivations to register as a body donor. Anatomical Sciences Education, 11(6), 623–631. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1796

- Cornwall, J., & Stringer, M. D. (2009). The wider importance of cadavers: Educational and research diversity from a body bequest program. Anatomical Sciences Education, 2(5), 234–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.103

- de Groot, J., van Hoek, M., Hoedemaekers, C., Hoitsm, A., Smeets, W., Vernooij-Dassen, M., & van Leeuewn, E. (2015). Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors. BMC Medical Ethics, 16(64). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0057-1

- de Moraes, E. L., & Massarollo, M. C. (2008). Family refusal to donate organs and tissue for transplantation. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 16(3), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692008000300020

- Fox, R. C., & Swazey, J. P. (1992). Spare parts: Organ replacement in American society. Oxford University Press.

- Goldman-Ida, B. (2018). Hasidic art and the kabbalah. Brill Press. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004290266

- Goss, A. L., Viswanathan, V. B., & DeLisser, H. M. (2019). Not just a specimen: A qualitative study of emotion, morality, and professionalism in one medical school gross anatomy laboratory. Anatomical Sciences Education, 12(4), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1868

- Habicht, J. L., Kiessling, C., & Winkelmann, A. (2018). Bodies for anatomy Education in medical schools: An overview of the sources of cadavers worldwide. Academic Medicine, 93(9), 1293–1300. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002227

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice. Routledge.

- Henry, G. T. (1990). Practical sampling. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985451

- Hildebrandt, S. (2010). Developing empathy and clinical detachment during the dissection course in gross anatomy. Anatomical Sciences Education, 3(4), 216. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.145

- Hildebrandt, S., & Champney, T. H. (2020). Ethical considerations of body donation. In L. K. Chan & W. Pawlina (Eds.), Teaching anatomy (pp. 215–222). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43283-6_23

- Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575. https://doi.org/10.1086/227049

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press.

- HTA. (2019). Roles and Responsibilities. Retrieved June 6, 2022, from https://www.hta.gov.uk/roles-and-responsibilities

- HTA. (2022). Body Donation to Medical Schools. Retrieved August 11, 2022, from https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-public/body-organ-and-tissue-donation/body-donation-medical-schools

- Human Tissue Authority. (2017). Code C: Anatomical Examination: Code of Practice and Standards. Retrieved june 27, 2022, from https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-professionals/codes-practice-standards-and-legislation/codes-practice

- Jacoby, L., & Jaccard, J. (2010). Perceived support among families deciding about organ donation for their loved ones: Donor vs nondonor next of kin. American Journal of Critical Care, 19(5), e52–61. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2010396

- Jensen, A. M. B. (2017). Guardians of ‘the gift’: The emotional challenges of heart and lung transplant professionals in Denmark. Anthropology & Medicine, 24(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2016.1193329

- Jones, D. G. (2015). Searching for good practice recommendations on body donation across diverse cultures. Clinical Anatomy, 29(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22648

- Jones, D. G., & Whitaker, M. I. (2009). Speaking for the dead: Cadavers in biology and medicine (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Laqueur, T. W. (2015). The work of the dead: A cultural history of mortal remains. Princeton University Press.

- Mason, J. (2012). Qualitative researching. Sage.

- Mauss, M. (1990) The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies ( W. D. Halls, Trans.; 2nd ed.). W. W. Norton.

- Morgan, J., Hopkinson, C., Hudson, C., Murphy, P., Gardiner, D., McGowan, O., & Miller, C. (2018). The rule of threes: Three factors that triple the likelihood of families overriding first person consent for organ donation in the UK. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 19(2), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143717738194

- Murphy, Z. N. (2019). After body donation for medical education: Identifying good practice in the interactions between Medical School Anatomy Unit staff and families after donor death [ PhD thesis]. University of York. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/29567/

- Prentice, R. (2013). Bodies in formation: An ethnography of anatomy and surgical Education. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv111jhxr

- Randolph, K. L., & Dahling, J. J. (2013). Interactive effects of proactive personality and display rules on emotional labor in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(12), 2350–2359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12184

- Richardson, R. (1988). Death, dissection and the destitute. Penguin.

- Riederer, B. M. (2016). Body donations today and tomorrow: What is best practice and why. Clinical Anatomy, 29(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22641

- Sharp, L. A. (2006). Strange harvest: Organ transplants, denatured bodies, and the transformed self. University of California Press.

- Shaw, D., & Elger, B. (2014). Persuading bereaved families to permit organ donation. Intensive Care Medicine, 40(1), 96–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3096-4

- Shaw, D., Georgieva, D., Haase, B., Gardiner, D., Lewis, P., Jansen, N., Wind, T., Samuel, U., McDonald, M., Ploeg, R., & ELPAT Working Group on Deceased Donation. (2017). Family over rules? An ethical analysis of allowing families to overrule donation Intentions. Transplantation, 101(3), 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001536

- Shaw, D., Lewis, P., Jansen, N., Samuel, U., Wind, T., Georgieva, D., Haase, B., Ploeg, R., & Gardiner, D. (2020). Family overrule of registered refusal to donate organs. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 21(2), 179–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143719846416

- Smith, C. F. (2018). The silent teacher: The gift of body donation. Anatomically Correct.

- Sothern, M., & Dickinson, J. (2011). Repaying the gift of life: Self-help, organ transfer and the debt of care. Social and Cultural Geography, 12(8), 889–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.624192

- Sque, M., Walker, W., Long-Sutehall, T., Morgan, M., Randhawa, G., & Rodney, A. (2018). Bereaved donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation, and perceived influences on their decision making. Journal of Critical Care, 45, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.002

- Strkalj, G., & Pather, N. (Eds.). (2017). Commemorations and memorial: Exploring the human face of anatomy. World Scientific Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1142/10118

- Tarlow, S. (2011). Ritual, belief and the dead in early modern Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511778629

- Taylor, L. J., Buffington, A., Scalea, J. R., Fost, N., Croes, K. D., Mezrich, J. D., & Schwarze, M. L. (2018). Harms of unsuccessful donation after circulatory death: An exploratory study. American Journal of Transplantation, 18(2), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14464

- Testart, A. (1998). Uncertainties of the ‘obligation to reciprocate’: A critique of Mauss. In W. James & N. Allen (Eds.), Marcel Mauss: A centenary tribute (pp. 97–110). Berghahn Books.

- Theodosius, C. (2006). Recovering emotion from emotion management. Sociology, 40(5), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038506067512

- Zealley, J. A., Howard, D., Thiele, C., & Balta, J. Y. (2021). Human body donation: How informed are the donors? Clinical Anatomy, 35(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23780