ABSTRACT

Exposure to parental suicide or substance-related death can be a risk factor for unwanted developmental trajectories. The stigma and taboo that often follow a death subject to being morally sanctioned in society (‘special deaths’) pose an extra challenge for the surviving child and family. The support of informal and formal networks is an important factor in adaptive coping; however, when the death is not socially recognised, the child’s access to support can be limited. This article presents the results of a systematic literature review seeking to explore children’s access to support when parentally bereaved as the result of suicide or a substance-related death. All six studies included address access to support after a suicide-related death. All studies focus on how children can be supported by loss-oriented activities, particularly how to facilitate open communication between the child and their surroundings. Based on this review, the authors recommend developing research on: 1) support for child survivors in the aftermath of substance-related death, 2), children’s everyday grieving practices, including their access to support for restoration-oriented activities, 3) the effects of social support on mental health outcomes, and 4) to developing research designs that allow for disturbing the phenomena of stigma production.

Introduction

Losing a parent in childhood is a stressful and traumatic experience, and we know from research undertaken in recent decades that it represents a risk factor in child development. Amongst the known outcomes, it may impair the child’s ability to cope with adversity (Coffino, Citation2009) and increase the child’s risk of developing delinquent behavioural (Berg et al., Citation2019; Draper & Hancock, Citation2011) and emotional problems (Berg et al., Citation2016). Additionally, parental loss increases the risk of substance abuse (Hamdan et al., Citation2013), deliberate self-harm and suicide (Burrell et al., Citation2017; Guldin et al., Citation2015; Jakobsen & Christiansen, Citation2011), as well as psychiatric disorders (Appel et al., Citation2013; Dowdney, Citation2000; Høeg et al., Citation2017; Stikkelbroek et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, the studies examined here show that some causes of death pose significantly higher risk of unwanted outcomes. A tendency visible across these studies is that suicide, as an unnatural and intentional death, poses a significantly higher risk than does natural death (such as from illness) (Brent et al., Citation2012; Burrell et al., Citation2017). Unnatural deaths are defined by Sjögren et al. (Citation2000, p. 1) as ‘resulting from unintentional events such as traffic accidents, falls, fires, and drownings, as well as those resulting from intentional events such as suicides and homicide’.

Substance/drug-related death is another unnatural death (Titlestad et al., Citation2021), that has proven to cause major physical and mental problems amongst people bereaved as adults. Research has shown high levels of prolonged grief symptoms (Titlestad & Dyregrov, Citation2022), increased risk for PTSD and depression compared to those bereaved by sudden, natural losses (Bottomley et al., Citation2022) and even early death (Christiansen et al., Citation2020). A systematic review on bereaved people’s experiences found no studies on the experiences of children (Titlestad et al., Citation2021), but based on research on adults, and research on consequences for children bereaved by suicide loss, it is reasonable to believe that being bereaved by substance-related death represents a major challenge also for child survivors.

Substance-related deaths and suicide deaths have by Guy and Holloway (Citation2007) been termed ‘special deaths’, referring to deaths that are morally sanctioned in society and thus not recognised as ‘grievable’. It is well documented from research with adults, that support is a significant factor in adaptive coping following bereavement (Bottomley et al., Citation2017; Dyregrov & Dyregrov, Citation2008; Dyregrov et al., Citation2018), but that in the case of ‘special deaths’, the survivors have less access to support (Bache & Guldberg, Citation2012; Dyregrov, Citation2004; Dyregrov & Selseng, Citation2022; Dyregrov et al., Citation2022). In a survey of adults bereaved by drug-related death, only 26% of respondents with children in the family (n = 100) reported to have received help for the children, and only 29% out of these were satisfied (to a high degree) with the help provided (Kalsås et al., Citation2022). There is no reason to think that support is any less important for children than for adults when it comes to adaptive coping after a loss. For example, a supportive relationship with- and care received from a caring adult, such as a family member, have been found helpful and are especially important for bereaved children (Loy & Boelk, Citation2013). What we know too little about, though, is how to succeed in supporting these children in ways that reduce risk and increase resilience. Support is a multifaceted concept, but a widely used definition on social support from Cobb (Citation1976) describes support as ‘information leading the subject to believe that he is cared for and loved, esteemed, and a member of a network of mutual obligations’. Support can take many different forms (e.g. practical support, economic support, emotional support, and informational support) (Dyregrov, Citation2004), and can be given both by professional helpers, network or by peers.

Stigma related to suicide and substance-related death

The term ‘disenfranchised grief’ (Doka, Citation1999) refers to how social norms for grieving practices produce legitimate and illegitimate grief. The stigma and shame attached to types of death that are not socially recognised can reduce the support offered by others to the bereaved and hinder the bereaved individual’s efforts to seek support (Doka, Citation1999).

Researchers have documented the stigma attached to suicide (Cvinar, Citation2005; Sudak et al., Citation2008), drug-related death (Dyregrov & Selseng, Citation2022), and substance-related death (Valentine et al., Citation2016). In death caused by illicit drug use, stigma also relates to criminality and a morally reprehensible lifestyle (Feigelman et al., Citation2012). The sociologist Erving Goffman (Citation1963) indicated that family is forced to an extent to share the negative associations linked to the stigmatised person/family member. Sheehan and Corrigan (Citation2020) introduce the concept of associative stigma to explain how close family, friends, and professionals, through their relationships with the stigmatised person/family member, can themselves be affected by stigma. In cases of drug-related death, research has shown how the stigma attached to the deceased’s drug use influences, for example, comments and support to the bereaved after the death of their loved one (Dyregrov & Selseng, Citation2022).

Stigma and feelings of guilt and shame can also cause the bereaved to withdraw from their social networks (Dyregrov et al., Citation2022). Withdrawal from others has been interpreted as a self-protection strategy to avoid further social harm in situations where the individual is experiencing shame and the self is threatened (De Hooge et al., Citation2010). Bache and Guldberg (Citation2012) explored the experiences of young adults bereaved by parental death due to alcoholism and found that the bereaved struggled with contradictory emotions and feelings of guilt that made it difficult to utilise social networks outside of the family.

Support in cases of suicide and substance-related death

Bereavement by an unexpected death that is potentially not socially recognised, such as suicide or a substance-related death, creates a post-death family context that differs from the context created by other deaths. Research shows that after a ‘special death’ the bereaved often suffer severe psychological and physical health consequences (Dyregrov et al., Citation2003; Kristensen et al., Citation2012; Titlestad & Dyregrov, Citation2022). These health consequences, and other grief-related reactions, affect the remaining caregiver’s ability to provide care and shape the developmental context for the bereaved child (Brent et al., Citation2012).

Development psychologist Arnold Sameroff has shown that we need to understand developmental trajectories as highly complex transactional processes: processes where children and contexts shape each other over time (Sameroff, Citation2009). Knowing that parental death because of ‘special deaths’ represents a risk factor in development, and that support may reduce risk and bolster resilience, does not in itself involve knowledge about the transactional mechanisms that function to make support work. As a starting point to gaining this kind of knowledge, this article will systematically review the research literature on all forms of support (professional, network, and peer support) for bereaved children following suicide or substance-related death.

Methods

This review has been guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Liberati et al., Citation2009). A review protocol has been published on the Open Science Framework platform (https://archive.org/details/osf-registrations-kjtym-v1).

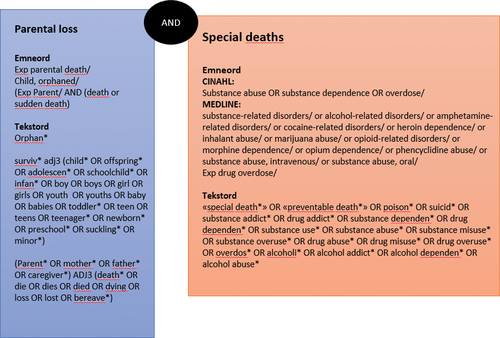

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in close collaboration with an experienced librarian. Based on the study’s aims, relevant keywords and search terms were identified. A search string was developed and piloted in Medline by the librarian, then adjusted accordingly. The search string combined mesh terms (subject headings) and text words relating to 1) parental death and survivors and 2) terms related to ‘special deaths’ and cause of death. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to combine these two elements, thus requiring both elements to be present. A detailed overview of the search string is provided (Appendix A). In mid-March 2022, the librarian conducted the final search in the following databases: Medline (1946-), Embase (1974-), PsycINFO (1806-), Cinahl (1981-), SocIndex (1908-), Scopus and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (1861-). A hand search was also conducted by all authors in different sources. A citation search was performed in all of the studies included for full-text reading, in one book (Loy & Boelk, Citation2013), and in one review article (Ratnarajah & Schofield, Citation2007). In addition, two relevant journals, Omega – Journal of Death and Dying and Death Studies, were searched by hand. The search included all relevant articles published between January 2012 and August 2022. An updated search was performed on 2 February 2023.

Eligibility criteria

In accordance with the PRISMA framework recommendations, we used PIOS elements to identify eligibility criteria (Liberati et al., Citation2009). The acronym PIOS stands for (P)articipants, (I)ntervention/phenomena, (O)utcome, and (S)tudy design.

Studies were included if participants (P) were a) bereaved persons who suffered the loss of a parent as a minor (aged 0–18 years) due to suicide or substance use, b) the surviving parents of parentally bereaved children of such a death, or c) professional helpers for children parentally bereaved as the result of such a death. Research on parents’ views were included when their perspectives on the support received by their children were provided. Studies where the phenomenon under study (I) was support to parentally bereaved children by either suicide or substance-related death were included.

In this review, the concept of support (I) is defined broadly and comprises the following three categories: a) professional help/formal assistance (e.g. psycho-social follow-up, grief counselling or therapy, support from kindergartens and schools), b) network support (e.g. family, friends, neighbours, social media support), and c) peer support (including internet support groups). Studies whose outcomes (O) related to children’s access to support, their perceptions of the support received, or studies that contributed to the knowledge on barriers to support were included. Studies whose study design (S) was qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method were included. Only empirical studies were included. Retrospective studies – for example studies of adults who had experienced the death of a parent when they were under the age of 18 – were included. There was no restriction regarding cultural context or publication date.

Studies were excluded if the full text was not in a Scandinavian language or English. Studies were excluded if they also included bereavement following death by other causes (unnatural or natural causes) or bereavement within other types of relationships, if it was not possible to distinguish between different causes of death or relationship types in the analysis and the results. All types of reviews were excluded. Studies were excluded if the parentally bereaved person was older than 18 when the death occurred, or if the studies included parentally bereaved children both under and over the age of 18 at the time of the death and the results did not distinguish between these groups.

Search process and outcome

A total of 9,579 record hits were imported into ENDnote (a reference-management software). Of these, 3,929 duplicates were deleted automatically and an additional 715 deleted manually. 4,935 records were then imported into Rayyan. Rayyan is a web-based software for conducting systematic reviews with double-blind screening within the researcher team. Here, an additional 286 duplicates were deleted. Then a total of 4,649 records were screened by abstract and title. The screening process was accomplished double-blind by dividing the references in Rayyan among three groups comprised of the authors of the current article (IJH and TKG, MAR and NB, MAR and SK). The three groups categorised the references as ‘include’, ‘exclude’, or ‘maybe’, then met to discuss their screening results, with any disagreements and references categorised as ‘maybe’ being discussed until consensus was reached.

Nineteen articles were found to be eligible as a result of the abstract screening and were then read in full text, independently and double-blind, by the three groups (IJH and NB, IJH and SK, MAR and TKG). The articles were categorised as ‘include’ or ‘exclude’ and the results were discussed by the three groups until consensus was reached. An extraction sheet developed for the assessment process by the first author (MAR) comprised various features of the included articles that were relevant to the purpose statement, such as the included articles’ purpose, sample, and methodology, and it included a column for the hand search in the reference list. After the hand search, an additional 25 records were identified and screened by abstract and title. Three of these articles were considered eligible for full-text reading. Overviews of the articles included for full-text reading (Appendix B), excluded articles and reasons for exclusion (Appendix C) are provided. An updated search yielded 312 new records, two of which were found eligible and read in full text. A Prisma Flow Diagram has been developed to illustrate the review process ().

Six qualitative articles were found eligible for quality appraisal (including one from the updated search). Quality appraisal was accomplished using the CASP checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Program, Citation2018), which consists of three broad issue areas that require consideration to appraise a study’s quality:

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Will the results help locally?

Each issue area is addressed by several questions that can be answered ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘can’t tell’. All six articles were found to be of satisfactory quality, although the scores varied (see ).

Table 1. Quality appraisal overview.

Analysis

The first and last authors (MAR and IJH) carried out the analysis that followed the quality appraisal. The analysis process was guided by analytical questions that sought to explore and synthesise data from the six included studies that contributes to the knowledge on bereaved children after ‘special deaths’, i.e. their access to support in general and the support they receive to practise grieving in particular. The analysis questions were both descriptive and explorative:

What characterises the included studies?

What kind of support do the studies focus on?

In what context were the studies conducted?

What possibilities are described for support to participate in grieving processes?

In this process, we made use of the CASP checklist, which functioned to systematise the reading relative to the studies’ characteristics. In addition, an analytical scheme was developed to plot the answers to the different elaborative questions and later synthesise them in discussions between the first and last authors. Through this process the two authors (MAR and IJH) searched for patterns and distinctive features in the selected data.

This analytical process was inspired by interpretative methodology (Haavind, Citation2000), and the two authors conducted several rounds of interpretation and discussion. Finally, the analysis was presented and discussed with the other three authors. Based on the analysis findings, we found that Dual Process Model of Bereavement (DPM) would function as a theoretical model to expand on the results to understand more about how to support children to adaptive grieving.

Characteristics of the included studies

The six studies have all been published in the last 15 years, four of them recently (Cutrer-Párraga et al., Citation2022; Regehr et al., Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2021; Wilson et al., Citation2022). Four studies are from the USA, one from Australia, and one from Sweden.

Aim of studies, design, and sample

Three studies (Cutrer-Párraga et al., Citation2022; Regehr et al., Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2021) sought to explore bibliotherapy as a way of supporting children after a parent’s death by suicide. One study explored child survivors’ perception of support following a parent’s suicide (Wilson et al., Citation2022), and the last two studies discussed how suicide may affect access to social support (Silvén Hagström, Citation2013) and social support as a key aspect of suicide’s effects on the family unit (Ratnarajah & Schofield, Citation2008). Although this review defined the concept of support broadly and included professional, network, and peer support, the result does not reflect this broad support perspective. Apart from the study by Wilson et al. (Citation2022) exploring both informal support and professional help, the studies generally approached support as an interpersonal phenomena dependent on communication within the family and the child survivor’s network.

All six of the included studies are qualitative studies. Additionally, Regehr et al. (Citation2021) include a quantitative rating of different books that the participants assessed for use in bibliotherapy. All six studies explore different aspects of support after suicide. None of the studies address support after substance-related death. The number of participants in the included studies varies from three (Cutrer-Párraga et al., Citation2022) to seventeen (Wilson et al., Citation2022). Five of the studies explored the experiences of suicide-bereaved children in retrospect (Ratnarajah & Schofield, Citation2008; Silvén Hagström, Citation2013; Watson et al., Citation2021; Wilson et al., Citation2022), while one study explored paraprofessionals’ perspectives on bibliotherapy (Regehr et al., Citation2021).

All five studies exploring child survivors’ experiences were based on individual in-depth interviews (Cutrer-Párraga et al., Citation2022; Ratnarajah & Schofield, Citation2008; Silvén Hagström, Citation2013; Watson et al., Citation2021; Wilson et al., Citation2022). Watson et al. (Citation2021) also included observation while the participants were looking through, and commenting on, different books, and Cutrer-Párraga et al. (Citation2022) invited the participants to review three different children’s picture books.

Analytical framework and results

Two of the studies applied a narrative analytical framework (Ratnarajah & Schofield, Citation2008; Silvén Hagström, Citation2013), while Wilson et al. (Citation2022) used a hermeneutic approach and Watson et al. (Citation2021) and Cutrer-Párraga et al. (Citation2022) described a combination of within-case analysis and cross-case analysis through different steps. Regehr et al. (Citation2021) took a hermeneutical phenomenological approach to the analysis. The studies included generally were short on theoretical perspectives and their analyses were mainly descriptive. The only theoretical model of bereavement referred to in the included studies was Worden’s Tasks of Grief (Worden, Citation1996), found in the study by Watson et al. (Citation2021) and Cutrer-Párraga et al. (Citation2022). Cutrer-Párraga et al. (Citation2022) also grounded their study in Cohen’s trauma-focused behavioural therapy (Cohen et al., Citation2017) that highlights the importance of opening up communication about the trauma.

As for results, the studies all emphasised open communication about both the suicide and its causes as an important supportive practice. The most significant barriers to openness mentioned were dysfunctional family patterns, stigma (both societal and self-imposed), and feelings of guilt and blame from family or networks. Summaries of characteristics of included studies are provided in Appendix D.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed as sufficient (see ), although some deficits were identified. The lowest scores related to ethical considerations and reflections on relationships between researcher and participants and how these influenced interview situations and data. For example, only one included study (Cutrer-Párraga et al., Citation2022) discusses how the interview situation is effective at producing the data material as part of the meaning-making processes that find place in the context of the research interview.

There is a general tendency for transparency and details about the analytical process to be lacking, which challenges the trustworthiness of the results. Additionally, the studies could generally have benefited from more reflections upon sample and recruitment processes. For example in the retrospective studies we found great variance in time since death, ranging from 5 to 70 years in Ratnarajah and Schofield’s (Citation2008) study to 8 months to 10 years in Silvén Hagström’s (Citation2013) study. Apart from Watson et al. (Citation2021) and Cutrer-Párraga et al. (Citation2022), who studied adults’ retrospective experience of suicide loss at a very young age (both studies use the same data material), none of the retrospective studies discussed the possible limitations of the participants’ recalling their experience many years after their parent’s suicide. None of the included studies explored the experiences of children under the age of 18 at the time of the interview.

Discussion

Based on the analysis of the six included studies, we identified some key characteristics of the understanding of, and approach to, support for children parentally bereaved after suicide. Noticeable, no studies on substance-related death were included. In the following, we will discuss the tendency among the six included studies to depict bereavement processes as individualised, isolated processes located mainly within the grieving child.

Across the studies, we found that the support, or lack thereof, of the child’s family was highlighted as an important factor influencing the child’s individualised bereavement process. From this perspective, it follows that an important means of support is facilitating openness (about the death and its cause) and communication, either within the family or between the family and its network (professional and/or informal). The focus remains on how to encourage the child to talk about the loss and process it emotionally. Following on from this, the suggested ways of support also remain individualised, with bibliography as an illustrative example (Cutrer-Párraga et al., Citation2022; Regehr et al., Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2021).

The focus on facilitating communication as the (only) mean to support children to adaptive grieving identified in the included studies, risk to undermine domains of support (e.g. practical, economical, information), and forms of support (professional, network, peers) that can be equally important in buffering the negative effects of the loss. Research has for example found that adults bereaved after ‘special deaths’ wish for help from both professionals, network, and peers, and they emphasise that it is not either /or, but different forms of support for different needs and to different time in the bereavement process (Dyregrov & Dyregrov, Citation2007). We can assume that this need for a broad and inclusive approach to support also will be the case for bereaved children, and from this point of view the focus on individualised bereavement processes in the included studies can be contested.

Depicting bereavement processes as individualised, isolated processes located mainly within the grieving child, fit with traditional, stage models of coping with loss. Earlier models of coping with loss were strongly influenced by attachment theory (e.g. Bowlby, Citation1980) and build on a linear understanding of grief where the bereaved confronts the loss and ‘works through the grief’ in different stages. An example is Worden’s Tasks of Grief (Worden, Citation1996). Theoretical understandings of how individuals come to terms with bereavement and adapt to life after loss have however been renewed over the past 10 to 20 years (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999, Citation2010, Citation2015). More recent models of bereavement encompass a more dynamic and coping-oriented understanding of the bereavement process, an example being the Dual Process Model of Bereavement (DPM) (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999, Citation2010).

DPM and a processual and relational perspective on bereavement

DPM was originally developed to address grief among adults, but it has also been used with bereaved children (Blueford et al., Citation2021; Popoola & Mchunu, Citation2015; Stokes et al., Citation1999). The DPM describes the processing of grief or adaptive coping with grief as oscillation between loss-oriented activities (or stressors) and restoration-oriented activities (or stressors) (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999, Citation2010). Loss-orientation processes are emotion-focused and include confronting the loss and mourning the deceased, which is consistent with the traditional view of bereavement. Restoration-orientation processes focus on restoring and developing one’s everyday life after the loss and include establishing new routines without the deceased, such as by focusing on activities. Empirical studies suggest that in healthy bereavement processes, the grieving individual oscillates between these processes of bereavement (Stroebe et al., Citation2007). In the following, we adapt the DPM to a sociocultural psychological perspective by highlighting the oscillation process as a relational and active process of practising grief.

Limited opportunities for children to practise restoration-oriented grieving?

The depiction of grief as individualised and emotion-focused, as we find in this review, corresponds only to the loss-orientation aspect of the DPM. The understanding that grief can be dealt with by way of cognitive and loss-oriented strategies, has gained little support in research, and may according to Wortman and Silver (Citation1989) be considered a myth. Sociocultural perspectives highlight how children’s developmental processes cannot be understood without seeing the child as a participant in social and cultural practices. This involves seeing the child as an agent who makes meaning together with others and contributes actively to arranging his or her own developmental conditions (Gulbrandsen, Citation2017). A study of 18 suicide-bereaved adolescents who had lost a family member or friend underscores the importance of agency and found it to be an important factor in what makes support helpful from these adolescents’ perspectives (Andriessen et al., Citation2022). The dominance of loss-oriented practices that we find in the studies included in this review limit the opportunities for children to practise grieving in more restoration-oriented ways. Hence, there seems to be a scarcity of knowledge about how bereaved children can be supported to oscillate between loss- and restoration-oriented grieving practices, which has been deemed necessary to healthily adapt to and cope with grief (Stroebe & Schut, Citation2010).

The strong focus on individualised loss-oriented support found in this review can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, it can be seen as children’s access to support being limited to loss-oriented support activities (for example, facilitating open communication about the deceased). On the other hand, it may be the result of the researchers’ perspectives and the theoretical perspectives or lack of such perspectives that has guided the research process and informed the data collection. The results of this systematic review contribute to Wortman et al’.s research in that they confirm that ‘myths of coping with loss’ persist, even in recently published studies (Wortman & Boerner, Citation2012; Wortman & Silver, Citation1989). Hence, research itself contributes to consolidating and reproducing these myths and pose an additional risk of reproducing ineffective ways of supporting bereaved individuals with consequences for bereavement outcomes. The reproduction of myths may contribute to limiting children’s opportunities to practise restoration-oriented grieving. Another central consequence for knowledge production of depicting bereavement processes as individualised processes, is the lack of addressing sociocultural dimension of stigma production.

Reproducing hegemonic narratives about grief and suicide bereavement?

All the included studies discuss how the taboos or silence surrounding a death can obstruct the processing of grief and receipt of support. It is known from previous research that after a suicide or substance-related death, the surviving family members experience less access to support due to social stigmatisation and self-stigmatisation (Bache & Guldberg, Citation2012; Dyregrov, Citation2004; Dyregrov & Selseng, Citation2022; Dyregrov et al., Citation2022). There is a prevailing understanding in the included studies of the dysfunctionality in the bereaved families that contributes to an overall picture of a marginalised population. However, the individual understanding of grief means the studies reviewed do not capture the complex transactional processes involved in stigma production. According to Goffman’s theory (Goffman, Citation1963), stigma is socially constructed in a cultural and historical context, where social practices – for example, silencing, avoiding etc. – contribute to constructing deviance. Hence, reducing the stigma related to suicide deaths cannot be accomplished individually or by opening communication within the family system alone; it must also involve changes at the societal level. A consequence of the individual understanding of grief is that the studies end up reproducing the cultural hegemonic narratives of being a child survivor of suicide and possibly fuelling the stigma attached to it.

Strengths and limitations of the review

The conduct of the review adhered to a rigorous framework, PRISMA (Liberati et al., Citation2009), which supported the quality of the review by assuring that all review elements and steps were considered thoroughly and that the process was documented and, as such, is transparent for the reader. Search terms were developed and tested collaboratively in several rounds by all authors and the librarian. Prior to the final search, a pilot search was conducted, and the search string adjusted. The search was carried out in six databases; a comprehensive hand search was also carried out. An update search was conducted prior to submission. We argue that, taken as a whole, this strengthens the review as it increases the likelihood of the relevant literature being covered. The double-blind process of reviewing the records and assessing the studies’ quality also affects the overall quality of the review. As a result of this process, we became aware of elements in the review protocol that could be assessed differently and thus reached a common understanding of the eligibility criteria.

The review has limitations that also need to be mentioned. Application of a strict methodological framework cannot entirely preclude relevant studies not being identified, because of the search terms and mesh terms chosen, or the databases selected. The search string (see Appendix A) and an overview of the databases have been provided so that the reader can self-assess the relevance and appropriateness of the search. Another limitation worth mentioning is that, although the main search included all years and all countries, the hand search in the two selected journals was, due to time restrictions, limited to articles published in the last ten years. We also decided not to include dissertations, books, reports, or other grey literature in the review and limited the review to peer-reviewed articles published in journals. The inclusion of additional publications channels might have influenced the review results. We restricted this review to studies that include parentally bereaved children and did not include, for example, children bereaved by the death of a sibling or friend. We argue that the relationship between the deceased and the bereaved affects the grieving context and the children’s need for and access to support, and therefore requires exclusive attention.

Conclusion and implications for further research

Based on the results of this review, we conclude that studies on children’s access to support after a ‘special death’ is scarce. There is a need for further studies that can contribute to our knowledge of measures that can effectively support children in terms of both loss- and restoration-oriented practices. Specifically, we stress the need for research on child survivors after substance-related death. More generally, there is a need for culturally sensitive studies with a transparent design and analysis on child survivors in the aftermath of any type of ‘special death’. This will enhance the studies’ trustworthiness and play an important role in their overall contribution to knowledge and the transferability of their results.

The results of this review also show the need for further research exploring the phenomenon from different theoretical and methodological angles to provide a broader and more comprehensive understanding of the complexity surrounding child survivors in the aftermath of a ‘special death’. Quantitative and mixed method designs are lacking, as are ethnographic studies. Additionally, studies should include the perspectives and experiences of research participants under the age of 18.

From studies of the adult population is documented that social support can be important for counteracting negative effects of the loss (Hibberd et al., Citation2010; Lobb et al., Citation2010), thus there are also some inconclusive findings regarding the effect on social support on for example complicated grief (Stroebe et al., Citation2005). Hence more research is needed to examine the mental health outcomes for all populations. Given the knowledge that no research so far has examined social support for children after substance-related loss, and the scarce research found on children’s access to support after suicide, there certainly is a need for more research also on social support as predictor for adaptive grieving and to examine more in detail the effectiveness of different forms of support. In this regard, longitudinal studies should be developed.

Research can play an important role in counteracting persistent stigmas and taboos surrounding ‘special deaths’, but it is important to pay more attention to the development of research designs and conduct more rigorous analyses to disrupt the phenomena of stigma production rather than reproduce them. To better understand the mechanisms of support with regard to the stigma of parental suicide or substance-related death in childhood, research designs could be developed that are closer to the child’s everyday life. For example, insight into the contexts of family, school life, and activities will enhance the understanding of the child’s opportunities to participate in grieving practices. Such knowledge is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the practical everyday aspects of how professional and informal networks work, or do not work, and can hence contribute to the knowledge about how to optimise bereaved children’s access to support and thereby diminish negative consequences of the loss.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Monika Alvestad Reime

Monika Alvestad Reime, PhD, social worker. Reime is Associate Professor at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. She has a PhD in Administration and Organization theory from the University of Bergen. Her research interests include public policy, child welfare, grief and bereavement research and improvement of health and social services. She is currently working as a post doctor in a national project on Drug-death Related Bereavement and Recovery (the END-project).

Tine K. Grimholt

Tine K.Grimholt, PhD, RN, Grimholt is Professor at VID Specialized University Oslo Norway and researcher at Oslo University Hospital She has a PhD in Suicidology from University of Oslo. Her research interests include suicidology, mental health, next of kin and offspring research. She is currently working with projects that include Children and Adolescent research on parental exposure (The CARPE project).

Siri Kjoelaas

Siri Kjoelaas, PhD, MPhil Psych, is a consultant at Centre for Rare Disorders at Oslo University Hospital. Her research interest include children, rare disorders, and grief.

Nina Bringedal

Nina Bringedal, is a PhD candidate at the department of Health, Function and participation at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research project is about children left behind by drug-related parental death. Bringedal is also a member of a national project on Drug-death Related Bereavement and Recovery (the END-project).

Ingrid Johnsen Hogstad

Ingrid Johnsen Hogstad, PhD, MPhil Psych, is Associate Professor at the Department of Health and Social Care at Molde University College, Norway. Her research focuses on developmental conditions for children in the welfare states, including the child-professional-encounter, child involvement/participation and professional practices. Both in research, teaching, and professional practice she has been particularly concerned with children experiencing parental death in early childhood.

References

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Rickwood, D., & Pirkis, J. (2022). “Finding a safe space”: A qualitative study of what makes help helpful for adolescents bereaved by suicide. Death Studies, 46(10), 2456–2466. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1970049

- Appel, C. W., Johansen, C., Deltour, I., Frederiksen, K., Hjalgrim, H., Dalton, S. O., Dencker, A., Dige, J., Bøge, P., Rix, B. A., Dyregrov, A., Engelbrekt, P., Helweg, E., Mikkelsen, O. A., Høybye, M. T., & Bidstrup, P. E. (2013). Early parental death and risk of hospitalization for affective disorder in adulthood. Epidemiology, 24(4), 608–615. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182915df8

- Bache, M., & Guldberg, A. (2012). Young people who have lost a parent because of alcoholism need special attention. Nordic Psychology, 64(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2012.693718

- Berg, L., Rostila, M., Arat, A., & Hjern, A. (2019). Parental death during childhood and violent crime in late adolescence to early adulthood: A Swedish national cohort study. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0285-y

- Berg, L., Rostila, M., & Hjern, A. (2016). Parental death during childhood and depression in young adults–A national cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(9), 1092–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12560

- Blueford, J. M., Thacker, N. E., & Brott, P. E. (2021). Creating a system of care for early adolescents grieving a death-related loss. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 7(3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2021.1973262

- Bottomley, J. S., Burke, L. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2017). Domains of social support that predict bereavement distress following homicide loss: Assessing need and satisfaction. OMEGA - Journal of Death & Dying, 75(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815612282

- Bottomley, J. S., Campbell, K. W., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2022). Examining bereavement‐related needs and outcomes among survivors of sudden loss: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(5), 951–970. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23261

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. Hogarth Press.

- Brent, D. A., Melhem, N. M., Masten, A. S., Porta, G., & Payne, M. W. (2012). Longitudinal effects of parental bereavement on adolescent developmental competence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 778–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.717871

- Burrell, L. V., Mehlum, L., & Qin, P. (2017). Risk factors for suicide in offspring bereaved by sudden parental death from external causes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 222, 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.064

- Christiansen, S. G., Reneflot, A., Stene-Larsen, K., & Johan Hauge, L. (2020). Parental mortality following the loss of a child to a drug-related death. European Journal of Public Health, 30(6), 1098–1102. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa094

- Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38(5), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

- Coffino, B. (2009). The role of childhood parent figure loss in the etiology of adult depression: Findings from a prospective longitudinal study. Attachment and Human Development, 11(5), 445–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730903135993

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2017). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Cutrer-Párraga, E. A., Cotton, C., Heath, M. A., Miller, E. E., Young, T. A., & Wilson, S. N. (2022). Three sibling survivors’ perspectives of their father’s suicide: Implications for postvention support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(7), 1838–1858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02308-y

- Cvinar, J. G. (2005). Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: A review of the literature. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 41(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0031-5990.2005.00004.x

- De Hooge, I. E., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2010). Restore and protect motivations following shame. Cognition and Emotion, 24(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802584466

- Doka, K. J. (1999). Disenfranchised grief. Bereavement Care, 18(3), 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682629908657467

- Dowdney, L. (2000). Annotation: Childhood bereavement following parental death. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(7), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00670

- Draper, A., & Hancock, M. (2011). Childhood parental bereavement: The risk of vulnerability to delinquency and factors that compromise resilience. Mortality, 16(4), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2011.613266

- Dyregrov, K. (2004). Micro-sociological analysis of social support following traumatic bereavement: Unhelpful and avoidant responses from the community. OMEGA -Journal of Death and Dying, 48(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.2190/t3nm-vfbk-68r0-uj60

- Dyregrov, K., & Dyregrov, A. (2007). Sosial nettverksstøtte ved brå død. Hvordan kan vi hjelpe? [Social network support in case of sudden death. How can we help?]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Dyregrov, K., & Dyregrov, A. (2008). Effective grief and bereavement support: The role of family, friends, colleagues, schools and support professionals. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Dyregrov, K., Kristensen, P., & Dyregrov, A. (2018). A relational perspective on social support between bereaved and their networks after terror: A qualitative study. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 5, 233339361879207. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393618792076

- Dyregrov, K., Nordanger, D., & Dyregrov, A. (2003). Predictors of psychosocial distress after suicide, SIDS and accidents. Death Studies, 27(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180302892

- Dyregrov, K., & Selseng, L. B. (2022). “Nothing to mourn, he was just a drug addict” - Stigma towards people bereaved by drug-related death. Addiction Research & Theory, 30(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2021.1912327

- Dyregrov, K., Titlestad, K. B., & Selseng, L. B. (2022). Why informal support fails for siblings bereaved by a drug-related death: A qualitative and interactional perspective. OMEGA - Journal of Death & Dying, 003022282211293. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221129372

- Feigelman, W., Jordan, J. R., McIntosh, J. L., & Feigelman, B. (2012). Devastating losses: How parents cope with the death of a child to suicide or drugs. Springer Publishing Co.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Penguin Psychology.

- Gulbrandsen, L. M. (2017). Barn, oppvekst og utvikling [Children, childhood and development]. In L. M. Gulbrandsen (Ed.), Oppvekst og psykologisk utvikling: Innføring i psykologiske perspektiver [Childhood and psychological development: Introduction to psychological perspectives] (2nd ed., pp. 15–50). Universitetsforlaget.

- Guldin, M.-B., Li, J., Pedersen, H. S., Obel, C., Agerbo, E., Gissler, M., Cnattingius, S., Olsen, J., & Vestergaard, M. (2015). Incidence of suicide among persons who had a parent who died during their childhood: A population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2094

- Guy, P., & Holloway, M. (2007). Drug-related deaths and the ‘special deaths’ of late modernity. Sociology, 41(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038507074717

- Haavind, H. (2000). Kjønn og fortolkende metode: metodiske muligheter i kvalitativ forskning [Gender and interpretative method: Methodological possibilities in qualitative research]. Gyldendal.

- Hamdan, S., Melhem, N. M., Porta, G., Song, M. S., & Brent, D. A. (2013). Alcohol and substance abuse in parentally bereaved youth. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 828–833. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.13m08391

- Hibberd, R., Elwood, L. S., & Galovski, T. E. (2010). Risk and protective factors for posttraumatic stress disorder, prolonged grief, and depression in survivors of the violent death of a loved one. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(5), 426–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2010.507660

- Høeg, B. L., Appel, C. W., von Heymann-Horan, A. B., Frederiksen, K., Johansen, C., Bøge, P., Dencker, A., Dyregrov, A., Mathiesen, B. B., & Bidstrup, P. E. (2017). Maladaptive coping in adults who have experienced early parental loss and grief counseling. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(14), 1851–1861. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316638550

- Jakobsen, I. S., & Christiansen, E. (2011). Young people’s risk of suicide attempts in relation to parental death: A population‐based register study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02298.x

- Kalsås, Ø. R., Titlestad, K. B., Dyregrov, K., & Fadnes, L. T. (2022). Needs for help and received help for those bereaved by a drug-related death: A cross-sectional study. Nordic Studies on Alcohol & Drugs, 14550725221125378. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725221125378

- Kristensen, P., Weisæth, L., & Heir, T. (2012). Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: A review. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 75(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

- Lobb, E. A., Kristjanson, L. J., Aoun, S. M., Monterosso, L., Halkett, G. K., & Davies, A. (2010). Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Studies, 34(8), 673–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2010.496686

- Loy, M., & Boelk, A. (2013). Losing a parent to suicide: Using lived experiences to inform bereavement counseling. Routledge.

- Popoola, T., & Mchunu, G. (2015). How later adolescents with adult responsibilities experience HIV bereavement in Nigeria: Application of a bereavement model. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 26(5), 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2015.06.003

- Ratnarajah, D., & Schofield, M. J. (2007). Parental suicide and its aftermath: A review. Journal of Family Studies, 13(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.327.13.1.78

- Ratnarajah, D., & Schofield, M. J. (2008). Survivors’ narratives of the impact of parental suicide. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 38(5), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.618

- Regehr, L. J., Heath, M. A., Jackson, A. P., Nelson, D., & Cutrer-Párraga, E. A. (2021). Storybooks to facilitate children’s communication following parental suicide: Paraprofessional counselors’ perceptions. Death Studies, 45(10), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1692972

- Sameroff, A. J. (2009). The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other (1st ed.). American Psychological Association.

- Sheehan, L., & Corrigan, P. (2020). Stigma of disease and its impact on health. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.ch139

- Silvén Hagström, A. (2013). ‘The stranger inside’: Suicide-related grief and ‘othering’ among teenage daughters following the loss of a father to suicide. Nordic Social Work Research, 3(2), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857x.2013.801877

- Sjögren, H., Eriksson, A., & Ahlm, K. (2000). Role of alcohol in unnatural deaths: A study of all deaths in Sweden. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(7), 1050–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04649.x

- Stikkelbroek, Y., Prinzie, P., de Graaf, R., ten Have, M., & Cuijpers, P. (2012). Parental death during childhood and psychopathology in adulthood. Psychiatry Research, 198(3), 516–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.024

- Stokes, J., Pennington, J., Monroe, B., Papadatou, D., & Relf, M. (1999). Developing services for bereaved children: A discussion of the theoretical and practical issues involved. Mortality, 4(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685977

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. OMEGA - Journal of Death & Dying, 61(4), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.61.4.b

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2015). Family matters in bereavement: Toward an integrative intra-interpersonal coping model. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 873–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615598517

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet, 370(9603), 1960–1973. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61816-9

- Stroebe, W., Zech, E., Stroebe, M. S., & Abakoumkin, G. (2005). Does social support help in bereavement? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(7), 1030–1050. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.1030

- Sudak, H., Maxim, K., & Carpenter, M. (2008). Suicide and stigma: A review of the literature and personal reflections. Academic Psychiatry, 32(2), 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.136

- Titlestad, K. B., & Dyregrov, K. (2022). Does ‘time heal all wounds?’ the prevalence and predictors of prolonged grief among drug-death bereaved family members: A cross-sectional study. OMEGA - Journal of Death & Dying, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221098584

- Titlestad, K. B., Lindeman, S. K., Lund, H., & Dyregrov, K. (2021). How do family members experience drug death bereavement? A systematic review of the literature. Death Studies, 45(7), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1649085

- Valentine, C., Bauld, L., & Walter, T. (2016). Bereavement following substance misuse: A disenfranchised grief. OMEGA - Journal of Death & Dying, 72(4), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815625174

- Watson, C., Cutrer-Párraga, E. A., Heath, M., Miller, E. E., Young, T. A., & Wilson, S. (2021). Very young child survivors’ perceptions of their father’s suicide: Exploring bibliotherapy as postvention support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111384

- Wilson, S., Heath, M. A., Wilson, P., Cutrer-Parraga, E., Coyne, S. M., & Jackson, A. P. (2022). Survivors’ perceptions of support following a parent’s suicide. Death Studies, 46(4), 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1701144

- Worden, J. W. (1996). Children and grief: When a parent dies. Guilford Press.

- Wortman, C., & Boerner, K. (2012). Beyond the myths of coping with loss: Prevailing assumptions versus scientific evidence. Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342819.013.0019

- Wortman, C. B., & Silver, R. C. (1989). The myths of coping with loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.57.3.349

Appendices Appendix A.

Search strategy