ABSTRACT

Even though California and Canada both legalised medical aid in dying (MAiD) in 2016 and have similarly sized populations, only 853 medically assisted deaths occurred in California versus 13,241 in Canada in 2022, the most recently reported year. Ten testable hypotheses were proposed to explain this 15-fold differential in MAiD utilisation. A demographically representative online survey of adults 60 and older in both jurisdictions (N = 556) revealed no differences in moral acceptance of MAiD or willingness to use it. However, only 25% of Californian participants were aware that MAiD was legally available versus 67% of Canadian participants. Evidence in the public domain revealed that there were 6.0 times more MAiD practitioners per capita in Canada than in California, and there was far greater support for MAiD by Canadian healthcare institutions. The evidence did not support hypotheses presuming more restrictive laws in California or greater access to palliative care/hospice. While other reasons may contribute to the difference in MAiD utilisation, limited public awareness, fewer MAiD practitioners per capita, and sparse support by healthcare institutions may significantly reduce California residents’ ability to exercise their autonomy when making end of life choices.

Introduction

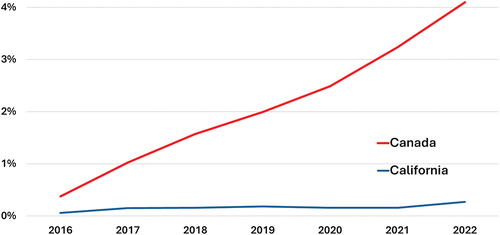

Twenty-three (Buchbinder & Cain, Citation2023) jurisdictions around the world have legalised some form of medical aid in dying (MAiD), but the rate at which people utilise MAiD varies dramatically. According to the responsible agencies’ most recent reports, 5.1% of all deaths in the Netherlands (Regional Euthanasia Review Committees, Citation2023) were assisted, 4.1% in Canada (Health Canada, Citation2023), 2.5% in Belgium (Public Health Food Chain Safety and Environment, Citation2023), 0.56% in Washington State (Center for Health Statistics, Citation2022), 0.53% in Oregon (Public Health Division, Citation2022), and 0.27% in California (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a).

Many factors might influence this variation, including but not limited to cultural differences, the length of time the legislation has been in effect, differences in medical systems and end-of-life care, and whether the patient is required to self-administer MAiD or a physician can perform the procedure. Distinguishing between these possibilities is challenging.

Fortuitously, the situation in California and Canada provides the opportunity for a reasonably well-controlled, but unprecedented (Buchbinder & Cain, Citation2023), natural experiment across both jurisdictions. Both California (State of California, Citation2015) and Canada (Parliament of Canada, Citation2016) first enabled their residents to request MAiD in 2016. Both have substantial populationsFootnote1 and advanced economies. Both provide access to high-quality health care, especially for people 65 and older.Footnote2 There are no substantial differences in the leading causes of death or overall death rates (California Department of Public Health, Citation2022; Statistics Canada, Citation2021). In both jurisdictions, physicians are independent agents, not state employees, and are free to choose the patients they accept and the treatments they are willing to provide. Physicians in both jurisdictions generally subscribe to the North American model of principlist bioethics (Beauchamp & Childress, Citation2019): respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice. Excluding the province of Quebec, both jurisdictions are primarily Anglophonic and share North American culture in addition to a substantial mix of ethnic and linguistic minorities.

In spite of these similarities, their official reports show an increasing difference in the rate of assisted deaths (). In 2016, when MAiD first became available, assisted deaths occurred 6.5 times more frequently in Canada than in California (0.375% vs 0.058% of all deaths respectively), a ratio that grew to 15 times by 2022 (4.1% vs 0.27%) (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a; Health Canada, Citation2023). A change in California’s law in 2021 (State of California, Citation2021) made it easier to access MAiD by reducing the time required between requests for MAiD to the prescribing physician from 15 days to 48 hours. This change increased the rate of assisted deaths substantially – from 0.157% in 2021 to 0.270% in 2022 – but did not fundamentally change the large discrepancy between assisted death rates in California vs Canada.

In order to understand the cause of this discrepancy it is first necessary to characterise which of the many possible contributory factors appreciably contributed to the large discrepancies between the two jurisdictions. We identified ten factors for which empirical methods could reveal the extent of their impact upon inter-jurisdictional discrepancies.Footnote3 For each of these factors, we tested the hypothesis that the inter-jurisdictional discrepancy is of sufficient magnitude to contribute the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates. The ten hypotheses are:

Public awareness – fewer Californians are aware that MAiD is a legally available option than similarly-placed Canadians

Moral acceptability – fewer Californians believe that MAiD is morally acceptable than Canadians

MAiD modality – Californians are less likely to choose MAiD because they are required to self-ingest the lethal doseFootnote4 unlike Canadians who may choose either self-ingestion or injection by a physician or nurse-practitionerFootnote5

Personal acceptability – fewer Californians are willing to consider MAiD when faced with a protracted and painful death than Canadians

Personal knowledge of MAiD recipient – Californians are less likely than Canadians to personally know someone who has used or considered MAiD

Confidence in ability to access MAiD – Californians are less confident in their ability to access MAiD than Canadians

Restrictive access to MAiD – the laws governing access to MAiD are more restrictive in California than Canada

Practitioner availability – there are fewer MAiD practitioners per capita in California than Canada

Institutional support for MAiD – the healthcare system provides less institutional support for MAiD in California than in Canada

End-of-life care access – Californians have better access to palliative and hospice care than Canadians.

In order test the first six hypotheses we conducted an inter-jurisdictional public survey of representative samples of adults aged 60 and older comparing California to Canada (excluding Quebec). The final four hypotheses were tested using data in the public domain. To the best of our knowledge, these are the first studies to use empirical tools to explore inter-jurisdictional differences in rates of MAiD utilisation.Footnote6

Methods

Inter-jurisdictional public survey

Hypotheses (1) to (6) were tested by two simultaneously administered web-based surveys of adults aged 60 years and older resident in California and Canada. The surveys were run concurrently starting on 1 June 2023 and were complete by 4 June (Canada) and 7 June (California). Participants were recruited from survey panels provided by Qualtrics Corporation (Provo UT). Equally-sized samples were drawn from residents of California and residents of Canada, excluding the Province of Quebec, according to demographically representative quotas by gender (male/female) and age group (60–74 years/75 and older).

The age cut-off of 60 years was selected because the overwhelming majority of people choosing MAiD are 60 and over: 91.9% in California (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a) and 92.2% in Canada (Health Canada, Citation2023). People from the Province of Quebec were excluded because including them would have required translating the survey into French, which would have introduced uncontrollable variables into the analysis.

The wording of each survey was specific to its sample’s jurisdiction but, following the contrastive vignette method (Burstin et al., Citation1980), the questions in each survey were phrased identically with only the jurisdictionally-specific words being changed. Appendix I contains the full text of both surveys.

In addition to demographic, consent, and qualifying questions plus a commitment question to improve data quality (Geisen, Citation2022), each participant was asked a series of seven questions concerning their awareness of MAiD, its moral acceptability, their willingness to use MAiD, their confidence in being able to access it, and whether they knew someone who had used MAiD. Appendix I has the full text of all questions, and includes the text as well as the tabulated results.

Surveys received from respondents who were not unique, who were not in the target population of adults 60 years and older, who were not in California or Canada excluding Quebec, who did not accept the quality commitment, or who took less than 120 seconds to answer the surveyFootnote7 were automatically rejected by the survey software. These responses were not accessible to the researchers.

Sampling errors were calculated using the standard error statistic and confidence intervals were calculated to 2 standard deviations, i.e. p = 0.05 (Fowler, Citation2009).

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board (H23–01496).

Structured textual comparison

A structured textual comparison was used to evaluate hypothesis (7) that the laws governing access to MAiD are more restrictive in California than in Canada.

Laws are highly structured documents. At the most detailed level, each element usually specifies a single aspect or criterion of the law. Laws on the same topic from different jurisdictions usually share many of the same elements. Each such element can then be compared directly between the jurisdictions. The presence of a particular element in one jurisdiction’s law and its absence in the other jurisdiction may also be significant in the comparison.

The comparison begins by creating a table identifying each criterion expressed in one or both jurisdictions’ laws. The details specific to each jurisdiction for each of the identified criteria are then added to the table. Finally, the jurisdictional details for each criterion are compared to determine which is more restrictive.

The results are reported quantitatively: the number of criteria for which each jurisdiction is more restrictive, and the number where they are equally restrictive. The results can also be reported qualitatively: detailing the ways in which one jurisdiction is more restrictive than the other.

Results

Results of inter-jurisdictional public survey

Completed surveys from 228 participants in California and 228 participants in Canada (excluding Quebec) are included in the reported results.

The participants’ demographics are shown in . To ensure demographic representativeness, population-matching quotas were enforced for both male and female participants in the age brackets of 60 to 74 years and 75 years and older. The Californian participants were 27% more white than the general population in this age group (78% vs 51%), but the Canadian participants were only 7% more white (90% vs 83%). Both samples were not significantly more likely to have been divorced or never married than the general population in this age group. The Californian and Canadian participants were more likely to have at least some college education than the general population in this age group (86% vs 62% in California and 61% vs 48% in Canada).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of samples.

The tabulated responses to all survey questions are shown in . All the following survey data is available via the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/abv8x/?view_only=f534be5790b84a069336a0f3c0553d20.

Table 2. Participant responses to survey questions.

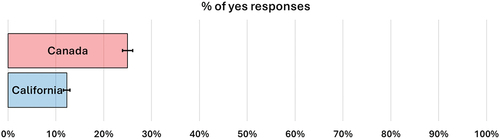

Hypothesis (1) public awareness

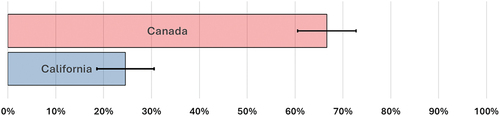

Only 25% of Californian participants reported being aware that MAiD was legally available to them. On the other hand, 67% of Canadian participants stated they were aware of their legal access to MAiD (). In other words, Canadians were found to be 2.7 times more aware of the availability of MAiD as a legal option, suggesting that public awareness of MAiD as a legal option may contribute to the discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (2) moral acceptability

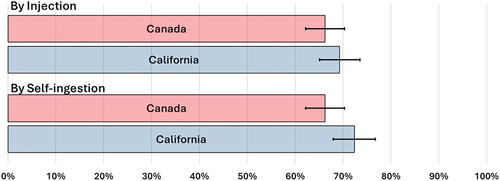

A similar majority of both samples (66% to 72%) agreed that MAiD was morally acceptable. There was no statistically significant difference between Californian and Canadian participants’ responses to the moral acceptability of MAiD (). This evidence does not support the hypothesis that a difference in moral acceptability contributes to the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (3) MAiD modality

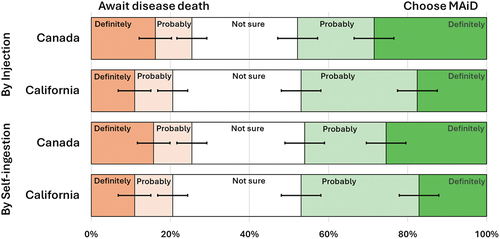

Slightly more California participants responded that MAiD by self-ingestion was morally acceptable than by injection (72% to 69%) but the difference was not statistically significant (). Californian participants’ willingness to personally choose or reject MAiD did not differ whether by self-ingestion or injection (). This evidence does not support the hypothesis that the difference in modality of providing MAiD contributes to the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (4) personal acceptability

The same fraction of both samples (about 47%) expressed a preference to ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ utilise MAiD rather than await death from the disease if facing a long and painful death from a disease like cancer (). Canadian participants were firmer in their opinions: 45% selected the ‘definitely’ option whether accepting or rejecting MAiD by injection, while only 29% of the Californian participants chose the ‘definitely’ option. Similar fractions of both samples were ‘not sure’ about their choice (27% − 32%). This evidence does not support the hypothesis that a difference in the personal acceptability of MAiD contributes to the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (5) confidence in accessing MAiD

Both samples were equally divided about confidence in their ability to access MAiD, with about one-third answering they were confident, one-third answering they were not, and one-third answering they did not know (). This evidence does not support the hypothesis that a difference in confidence in accessing MAiD contributes to the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (6) personal knowledge of a MAiD recipient

25% of Canadian participants and 12% of Californians reported personal knowledge of someone who had used or considered MAiD (). There is a 2× difference between Californians and Canadians, suggesting that personal knowledge of a MAiD recipient may contribute to the discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates. However, since so few participants in either jurisdiction had personal knowledge of a MAiD recipient (), the evidence that this hypothesis contributes to the discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates is relatively weak.

Results from evidence in the public domain

Hypothesis (7) more restrictive MAiD laws in California than Canada

Canada has recently broadened access to MAiD, in particular by removing the requirement for a reasonably foreseeable death (Parliament of Canada, Citation2021) resulting in a substantive difference between the law in Canada and California. After the law was changed in Canada, the number of MAiD procedures that still relied upon the reasonably foreseeable death criterion (so-called Track 1) accounted for 96.5% of MAiD procedures (Health Canada, Citation2023) versus 100% of MAiD procedures in California (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a). Canada’s recent removal of the restriction on this criterion does not account for the discrepancy between the jurisdictions.

We also used a structured textual comparison of the laws governing foreseeable deaths to examine this hypothesis. The analysis revealed 24 eligibility and safeguard criteria (Parliament of Canada, Citation2021; State of California, Citation2021) (Appendix II). Of these, 3 of California’s criteria were more restrictive, 10 of Canada’s were more restrictive, and 11 were essentially identical. The most notable differences were:

Both jurisdictions require MAiD requestors to have incurable and irreversible disease, but only Canada requires the MAiD provider to confirm the requestors’ intolerable physical or psychological suffering [§241.2(c)Footnote8].

Canada requires only that natural death be reasonably foreseeable [§241.3] unlike California’s explicit 6 month requirement [§443.2(r)], but both jurisdictions recognise that any such prognosis is fraught with uncertainty. The authors are not aware of any evidence that MAiD is provided earlier in Canada than California because of the lack of an explicit time limit.

California law is silent on the relationship between the MAiD prescribing physician and the consulting physician who confirms the requestor’s diagnosis, prognosis, and capacity. Canadian law explicitly prohibits mentorship, supervisory, or undue influence between them [§241.2(6)].

Canadian law provides explicit punishments for failure to comply with the safeguards (up to 5 years imprisonment §2.41.3) or failure to report (up to 2 years imprisonment §241.31). California law is silent on punishments for failure to comply or report.

Neither the statistical nor the textual evidence supports the hypothesis that more restrictive legal criteria in California contributes to the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (8) availability of MAiD practitioners

In 2022 Canada reported 1,837 practitioners provided MAiD at least once in the year (Health Canada, Citation2023) while California reported 341 physicians prescribed MAiD drugs at least once in the year (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a). Normalizing these data to the relevant population size, there are 5.2 MAiD providers per 100,000 in Canada vs 0.87 in California. In other words, there are 6.0 times fewer active MAiD practitioners per capita in California than Canada.

Canada permits nurse practitioners to provide MAiD, while California does not. However, 95.0% of all MAiD practitioners in Canada are physicians and they performed 90.6% of all MAiD procedures in 2022 (Health Canada, Citation2023). The availability of nurse practitioners providing MAiD thus does not explain the difference in the availability of MAiD practitioners between the two jurisdictions.

The substantial difference in numbers of MAiD practitioners per capita between California and Canada supports the hypothesis that the availability of MAiD practitioners contributes to the observed discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Hypothesis (9) institutional support for MAiD

In Canada, MAiD services, including referrals, are coordinated through provincial or regional healthcare authorities (Frolic & Oliphant, Citation2022). These authorities publish informative websites with MAiD-specific phone numbers and email addresses, e.g. (Nova Scotia Health, Citation2023; Vancouver Coastal Health, Citation2023)., These authorities also provide professionally-staffed MAiD care coordination services (Simpson-Tirone et al., Citation2022) that accept written requests for MAiD which are then forwarded to an appropriate MAiD practitioner. In 2021, 47.9% of all MAiD procedures across Canada were initiated through an institutional care coordination service (Health Canada, Citation2023, p. 43).

In California there are no regional or local health care authorities from which residents can seek information, let alone assistance. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) which is responsible for reporting on all instances of MAiD in California does not list MAiD or the End of Life Option Act on its main web page, nor in the A-Z index (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023b). Kaiser-Permanente, the largest single healthcare provider in California with over 9 million clients of all ages (Kaiser-Permanente, Citation2023b), does not describe the MAiD option on its ‘Care at the End of Life’ webpages (Kaiser-Permanente, Citation2023a), although it does have pages describing MAiD that are accessible via a Google search.

Informing Californians about the availability of MAiD as an end-of-life option is left to a recently-formed medical society which offers a patient referral service (American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying, Citation2023), a few palliative care physicians who make their services known via their websites (e.g. Empowered Endings, Citation2023), and charitable organisations such as Compassion & Choices (Citation2023) and End of Life Choices California (Citation2023), both of which operate public outreach programs.

Unlike Canadian healthcare institutions which provide robust support for members of the public seeking to access MAiD, neither public nor private healthcare institutions in California provide any support. The substantial differential in institutional support may be a contributory factor to the discrepancy in MAiD utilisation.

Hypothesis (10) access to palliative and hospice care

Palliative and hospice care are available at no cost for most Canadians (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, Citation2023) and most Californians (American Hospice Foundation, Citation2023), especially those 65 and older. However, significant barriers to accessing such care exist because of factors such as providers’ lack of knowledge, reluctance to refer to hospice, and confusion about referral processes in both California (Wang et al., Citation2019) and Canada (Costante et al., Citation2019). These barriers result in relatively low rates of utilisation of hospice and palliative care: 42.3% of Californians who died in 2020 used hospice (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, Citation2022) and 58% of Canadians who died in 2021–2022 (Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citation2023).

MAiD recipients, however, were remarkably more likely to take advantage of hospice and palliative care than the general population: 95% of Californians and 77.6% of Canadians who used MAiD were enrolled in hospice or palliative care (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a; Health Canada, Citation2023). This small difference in enrolment cannot explain the 15-fold difference in MAiD utilisation between the jurisdictions.

Furthermore, as Downar et al. (Citation2023) report, ‘People generally request MAiD because of a loss of autonomy or dignity, or an inability to engage in activities that they used to find enjoyable, rather than pain or physical symptoms’. However, such existential distress cannot yet be relieved by psychotherapeutic interventions (Bauereiß et al., Citation2018). Thus, even if palliative care of the highest quality were available, it would be unlikely to materially change the number of requests for MAiD.

Similarly, differential access to disability support services cannot explain the disparity in rates. Health Canada (Citation2023) reports that 36.8% of MAiD recipients in 2022 required disability support services, but only 4.1% of this 36.8% did not receive them, and of this 4.1% only 25% did not have access. In other words, 25% of 4.1% of 38.9% or 0.40% of MAiD recipients needed disability support services but did not have access. Again this small number cannot explain the 15-fold difference in MAiD utilisation rates between the jurisdictions.

This evidence does not support the hypothesis that differential access to hospice and palliative care contributes to discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates.

Discussion

Of the ten possible factors that might contribute to the 15-fold discrepancy in MAiD utilisation rates between Canada and California, our survey of the general public of California and Canada and evidence in the public domain show that three stand out as likely factors that contribute to the observed discrepancy.

Public awareness of MAiD as a legally available end-of-life option:

2.7 times as many Canadian participants in our public survey reported being aware of MAiD as Californian participants: 67% to 25%.

Availability of MAiD practitioners:

The government agencies charged with tracking MAiD deaths report that there are 5.2 MAiD practitioners per 100,000 people in Canada vs only 0.87 per 100,000 in California, i.e. 6.0 times as many MAiD practitioners per capita in Canada as there are in California.

Institutional support for MAiD:

In Canada, every provincial and regional public health authority in Canada makes accessing MAiD straightforward: full information is readily available on their websites, and almost all provide a professionally-staffed MAiD care coordination service. About half of all MAiD recipients use these institutionally provided coordination services.

However, in California, neither the state’s health department nor any of the major healthcare systems have information about accessing MAiD readily available on their websites, although such information may be available via a Google search. The only organisations that provide physician referral or care coordination are small volunteer-staffed charities.

Most significantly, these results indicate that the discrepancy is not due to social or legal differentials such as differing views of moral acceptability or more restrictive legislation. One could then recast the question in normative terms: Should public awareness and institutional support be increased so that Californians are not denied a choice that is legally theirs?

If the answer to this question is yes, then investigation into the best ways to increase public awareness and institutional support is warranted.

Is there a natural rate of MAiD utilization?

The discrepancy between California and Canada also raises the question of whether there is a natural rate of MAiD utilisation. In other words, if people in both jurisdictions were equally aware of the available choices, had equal access to MAiD practitioners, and were equally well supported in their choices by healthcare institutions, would the rates approach some natural limit?

In Canada assisted deaths as a fraction of all deaths have increased almost linearly by 0.6% each year for the last five years to 4.1% in 2022. Similar trends have been observed in the Netherlands and Belgium which were at 5.1% and 2.5% respectively in 2022. This data indicate that if there is such a limit, it is in excess of 5% of all deaths.

The data from our public survey combined with public domain statistics may provide some guidance in determining what this limit may be.

Two-thirds of people who choose MAiD have been diagnosed with cancer: 63.0% in Canada (Health Canada, Citation2023) and 66.0% in California (California Department of Public Health, Citation2023a). In 2019,Footnote9 80,371 of a total of 285,270 Canadian deaths (Statistics Canada, Citation2021) and 59,828 of a total of 270,952 Californian deaths (California Department of Public Health, Citation2022) were due to cancer.

Our results from show that 25% of Canadians and 17% of Californians claim they would ‘definitely’ choose MAiD rather than face the prospect of a long and painful death from a disease like cancer. When faced with the actual situation, not all of the ‘definitely’ respondents would actually choose MAiD while a few of the others might choose MAiD. The 25% and 17% responses could thus be construed as an upper bound on the likely number of people choosing MAiD if faced with cancer.

Applying these upper bounds to the actual number of cancer deaths suggests that about 20,000 Canadians (25% of 80,371) and 10,000 Californians (17% of 59,828) would choose MAiD each year following a cancer diagnosis. Because cancer patients account for only 2/3 of MAiD recipients in both Canada and California, the total number of people choosing MAiD each year might be 30,000 in Canada (3/2 × 20000) and 15,000 in California (3/2 × 10000). In other words, the upper bound on the natural MAiD utilisation rate might be 10.5% of all deaths in Canada and 5.5% of all deaths in California.

These calculations imply that a two-fold difference in MAiD utilisation rates could be expected between Canada and California because of a combination of demographic differences and different expressed preferences for MAiD, even if awareness, MAiD practitioner availability, and institutional support were equivalent. These calculations also imply that assisted deaths in Canada will continue their steady increase for about another decade.

Conclusion

The dramatically lower rate of MAiD utilisation in California compared to Canada can partially be explained by Californian’s lack of awareness of MAiD as an end-of-life option. Other factors such as one-sixth as many MAiD practitioners per capita and a lack of institutional support for MAiD may also play a part. However, factors such as perceived moral acceptability, willingness to personally consider MAiD, modality of administration, restrictiveness of enabling legislation, and differential access to palliative and hospice care do not appear to have an impact.

High public awareness, strong support from healthcare institutions, and an appropriate number of MAiD practitioners per capita may also contribute to the relatively high MAiD utilisation rates observed in Belgium and the Netherlands. Their lack may also impact the low rates seen in other US states where MAiD is legal.

This natural experiment will continue. The evolution of the two jurisdictions may reveal other factors which influence the end-of-life choices made by apparently similar populations. These and other questions will provide fruitful areas for continued research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adrian C. Byram

Adrian Byram serves on the Board of Directors of End of Life Choices California. Born in the UK, Adrian grew up in Canada and earned BSc and MSc degrees in Mathematics and Physics from the University of Toronto in the late 1960s. He then attended Stanford University, completing his qualification for a PhD in Engineering-Economic Systems before leaving to start his first software company in 1975. In 2013, after nearly 40-years as an entrepreneur and senior executive in the IT industry, Adrian retired and enrolled in the University of British Columbia, earning a PhD in Neuroethics in 2020. His thesis found that the choices made by surrogate decision-makers for ICU patients often failed to meet patients’ values, and suggested new ways to ensure patients’ autonomy is truly respected. After returning to California in 2019, Adrian has continued to focus on ways to enhance personal autonomy in end-of-life situations, including research on advance requests for MAiD after the onset of dementia, and volunteer work with dying patients as well as public outreach.

Peter B. Reiner

Peter Bart Reiner is Professor Emeritus of Neuroscience and Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia. Born in Hungary, Peter arrived in the USA as part of the wave of refugees who escaped during the revolution in 1956. He received his BA, VMD, and PhD degrees at the University of Pennsylvania, after which he moved to UBC as a postdoctoral fellow in the storied Kinsmen Laboratory of Neurological Research. He joined the faculty in 1988 and a decade later became full Professor as well as the inaugural holder of the Louise Brown Chair in Neuroscience and Head of the Graduate Program in Neuroscience. He took leave from the University for six years when he became President and CEO of Active Pass Pharmaceuticals, a biotech company that he founded in order to address the scourge of Alzheimer’s disease. Upon returning to academia, Peter pivoted to neuroethics, co-founding the National Core for Neuroethics in 2007. In this new field he championed the use of applying rigorous empirical methods to neuroethical issues. Peter has testified before the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, the Council of Europe/OECD, and the Special Joint Parliamentary Committee on Medical Assistance in Dying.

Notes

1. California v Canada in 2022: population 39 million v 35 million; GDP $4T v $2T.

2. The US Government provides Medicare to almost all US residents 65 and older (United States Congress, Citation1965). The Canadian Government, through its Provinces and Territories, provides Medicare to all people resident in the country for more than 90 days (Parliament of Canada, Citation1985).

3. In order to identify these factors, the authors primarily relied on their experience. Both authors have been actively engaged in research on MAiD, particularly concerning advance requests for MAiD after a diagnosis of dementia (Byram et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). In his work with End of Life Choices California, Byram frequently makes presentations to and interacts with community groups and hospice workers across California. Pullman (Citation2023) also suggested three possible factors: the difference in MAiD modality, more restrictive laws in California, and greater access to palliative care.

4. The California End of Life Option Act (State of California, Citation2015) requires the patient to swallow the lethal dose or to push the plunger on a syringe connected to a rectal catheter or PEG tube.

5. Canadians can choose to self-ingest the lethal dose instead receiving an injection. However, in 2022 fewer than seven people chose self-ingestion, i.e. <0.05% of all MAiD recipients (Health Canada, Citation2023).

6. There may be an opportunity for a similar study by comparing MAiD rates in Western Australia and New Zealand, both of which enabled the practice in 2019.

7. A cut-off of this type is recommended to eliminate survey responses by bots or participants quickly clicking through the questions (Teitcher et al., Citation2015)

8. The relevant subsection of each law is cited in []. California’s subsections are all subsections of §443 and Canada’s are subsections of §241.

9. 2019 statistics were used to avoid distortions due to COVID-19.

References

- American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying. (2023, July 29). https://www.acamaid.org/about/

- American Hospice Foundation. (2023). FAQ: How is hospice care paid for? https://americanhospice.org/learning-about-hospice/how-is-hospice-care-paid-for/

- Bauereiß, N., Obermaier, S., Ozunal, S. E., & Baumeister, H. (2018). Effects of existential interventions on spiritual, psychological, and physical well-being in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psycho-Oncology, 27(11), 2531–2545. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4829

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2019). Principles of bioethics (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Buchbinder, M., & Cain, C. (2023). Medical aid in dying: New frontiers in medicine, law, and culture. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 19(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110722-083932

- Burstin, K., Doughtie, E. B., & Raphaeli, A. (1980). Contrastive vignette technique: An indirect methodology designed to address reactive social attitude measurement 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 10(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1980.tb00699.x

- Byram, A. C., Reiner, P. B., & Wiebe, E. (2022). Testimony provided to the special joint committee on medical assistance in dying. Parliament of Canada. https://www.parl.ca/documentviewer/en/44-1/AMAD/meeting-24/evidence

- Byram, A. C., Wiebe, E. R., Tremblay-Huet, S., & Reiner, P. B. (2021, June). Advance requests for MAiD in dementia: Policy implications from survey of Canadian public and MAiD practitioners. Canadian Health Policy, 1–9. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/product/advance-requests-for-maid-in-dementia-survey-of-canadian-public-and-maid-practitioners-2/

- California Department of Public Health. (2022). 2014-2021 Final deaths by year statewide. Retrieved August 20, 2023, from https://data.chhs.ca.gov/dataset/7a456555-87b9-4830-817c-72d72e628745/resource/f8bb67bf-923d-4d74-8714-dc2bcf5609b7/download/20221215_deaths_final_2014_2021_state_year_sup.csv

- California Department of Public Health. (2023a). California end of life option act 2022 data report.

- California Department of Public Health. (2023b). A to Z index. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Pages/AtoZIndex.aspx

- Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. (2023, September 6). Hospice palliative care. https://www.chpca.ca/about-hpc/

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2023). Access to palliative care in Canada 2023. CIHI.

- Center for Health Statistics. (2022). 2021 Death with dignity act report. Washington State Department of Health.

- Compassion & Choices. (2023, August 10). https://www.compassionandchoices.org/

- Costante, A., Lawand, C., & Cheng, C. (2019). Access to palliative care in Canada. Healthcare Quarterly, 21(4), 10–12. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2019.25747

- Downar, J., MacDonald, S., & Buchman, S. (2023). What drives requests for MAiD? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 195(40), E1385–E1387. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.230259

- Empowered Endings. (2023, August 25). https://integratedmdcare.com/

- End of Life Choices California. (2023, August 10). https://endoflifechoicesca.org/

- Fowler, F. J. (2009). Survey research methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230184

- Frolic, A., & Oliphant, A. (2022). Introducing medical assistance in dying in Canada: Lessons on pragmatic ethics and the implementation of a morally contested practice. HEC Forum: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Hospitals’ Ethical and Legal Issues, 34(4), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-022-09495-7

- Geisen, E. (2022). Using commitment requests instead of attention checks. Qualtrics.com. https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/attention-checks-and-data-quality/

- Health Canada. (2023). Fourth annual report on medical assistance in dying in Canada 2022.

- Kaiser-Permanente. (2023a). Care at the end of life. Retrieved August 2, 2023, from https://healthy.kaiserpermanente.org/southern-california/health-wellness/health-encyclopedia/he.care-at-the-end-of-life.aa129753#aa129756

- Kaiser-Permanente. (2023b). Our impact in California. Retrieved August 2, 2023, from https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/commitments-and-impact/public-policy/our-impact/news-perspectives-on-public-policy-california

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2022). NHPCO facts and figures: 2022 edition.

- Nova Scotia Health. (2023, August 10). Medical assistance in dying (MAiD). https://www.nshealth.ca/content/medical-assistance-dying-maid

- Parliament of Canada. (1985). Canada health act.

- Parliament of Canada. (2016). Bill C-14 An Act to amend the criminal code and to make related amendments to other acts (medical assistance in dying).

- Parliament of Canada. (2021). Bill C-7 an act to amend the criminal code (medical assistance in dying).

- Public Health Division. (2022). Oregon death with dignity act: 2021 data summary. Oregon Health Authority.

- Public Health Food Chain Safety and Environment. (2023). EUTHANASY – Figures for 2022. Belgium Federal Public Service.

- Pullman, D. (2023). Slowing the slide down the slippery slope of medical assistance in dying: Mutual learnings for Canada and the US. The American Journal of Bioethics, 23(11), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2023.2201190

- Regional Euthanasia Review Committees. (2023). RTE: Annual report 2022. The Hague.

- Simpson-Tirone, M., Jansen, S., & Swinton, M. (2022). Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) care coordination: Navigating ethics and access in the emergence of a new health profession. HEC Forum, 34(4), 457–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-022-09489-5

- State of California. (2015). AB15 end of life option act.

- State of California. (2021). SB380 end of life option act amendment.

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Table 13-10-0394-01 leading causes of death, total population, by age group.

- Teitcher, J. E. F., Bockting, W. O., Bauermeister, J. A., Hoefer, C. J., Miner, M. H., & Klitzman, R. L. (2015). Detecting, preventing, and responding to “fraudsters” in internet research: Ethics and tradeoffs. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(1), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12200

- U.S. Congress. (1965). Social Security Act. Title XVIII: Health insurance for the aged and disabled.

- Vancouver Coastal Health. (2023, August 10). Medical assistance in dying (MAiD). https://www.vch.ca/en/service/medical-assistance-dying

- Wang, S. E., Liu, I.-L. A., Lee, J. S., Khang, P., Rosen, R., Reinke, L. F., Mularski, R. A., & Nguyen, H. Q. (2019). End-of-life care in patients exposed to home-based palliative care vs hospice only. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(6), 1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15844

Appendix I

– Text of survey

The texts of the two surveys are shown below. Each question begins with question number and phrase, and each possible response has a code in (); these were not shown to participants, but are included in the data repository. Differences between the California and Canada texts are shown with the California text in italics/the Canada text underlined.

CQ2 Commitment

This survey asks about possible end-of-life choices. To ensure the most accurate measures of your opinions, it is important that you provide thoughtful answers to each question in this survey.

Do you commit to providing thoughtful answers?

I can’t promise anything (1)

Yes, I will (2)

No, I will not (3)

CQ3 California Resident

Do you live in California?

Yes (1)

No (2)

MQ01 Awareness

Is it legal for a resident of California/Canada with a terminal illness – an illness like Stage 4 cancer that will almost certainly cause death within 6 months – to ask a doctor for Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying so they can benefit from a quick and painless death at the time and place of their own choosing?

Yes (1)

No (2)

I don’t know (3)

MT1 Presented after the awareness question was answered

Here is the correct information:

California, some other US states, and all provinces in Canada/ All provinces in Canada and, in the US, California and several other states allow people with a terminal illness to end their suffering at a time and place of their own choosing, a procedure called Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying. The procedure has been legal in both California/Canada and Canada/California since 2016.

To prevent abuse there is a formal legal process that must be followed before a doctor may provide Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying for a patient. For example, the patient has to make the request twice, a second doctor has to confirm that the patient is eligible, and the patient has to sign a written request in the presence of witnesses who will not benefit from the patient’s death.

We want to learn how you feel about the different approaches to Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying taken in California/Canada and Canada/California.

MQ11 Swallowing morally acceptable

In California, after an eligible patient has requested Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying, the doctor prescribes lethal drugs which the patient can swallow whenever they are ready, resulting in their quick and painless death.

Importantly, the patient demonstrates this is their decision because they choose the time and place, and they must swallow the drugs on their own.

Do you think it is morally acceptable for a doctor to provide Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying by prescribing lethal drugs to be swallowed by the patient?

Yes (1)

No (2)

I don’t know (3)

MQ12 Injection morally acceptable

In Canada, after an eligible patient has requested Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying, the doctor visits the patient whenever they are ready, confirms again that the patient wants to die now, and then injects the patient with lethal drugs through an intravenous (IV) line, resulting in their quick and painless death.

Importantly, the patient demonstrates this is their decision because they choose the time and place, and they must consent to the injection on their own.

Do you think it is morally acceptable for a doctor to provide Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying by injecting lethal drugs into the patient?

Yes (1)

No (2)

I don’t know (3)

MQ21 Willing to swallow

If you were facing a long and painful death from a disease like cancer, would you await death from the disease or would you end your suffering early by swallowing lethal drugs prescribed by a doctor (if it were legal and customary in Canada)?

MQ22 Willing to inject

If you were facing a long and painful death from a disease like cancer, would you await death from the disease or would you end your suffering early by consenting to a lethal injection by a doctor (if it were legal and customary in California)?

MQ23 Access confidence

If you decided to take advantage of Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying, are you confident you would know how to access it?

Yes (1)

No (2)

Not sure (3)

MQ24 Know MAiD

Do you personally know someone who has chosen to end their life with the help of Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying or who has considered doing so?

Yes (1)

No (2)

Not sure (3)

MQ30 Comments

You have responded to questions about Medical Aid/Assistance in Dying. If you would like to share any of your thoughts about this topic, please do so below — doing so is completely optional.

DQ00 Province

Which province do you live in?

Newfoundland (1)

Nova Scotia (2)

New Brunswick (3)

PEI (4)

Quebec (5)

Ontario (6)

Manitoba (7)

Saskatchewan (8)

Alberta (9)

British Columbia (10)

NWT or Yukon (11)

I do not live in Canada (12)

DQ01 Age

How old are you?

Less than 55 years old (50)

55 to 59 years old (55)

60 to 64 years old (60)

65 to 69 years old (65)

70 to 74 years old (70)

75 to 79 years old (75)

80 years or more (80)

DQ02 Gender

How do you describe yourself?

Male (1)

Female (2)

Non-binary / third gender (3)

Prefer not to say (4)

DQ03 Race

Which race or combination do you identify as?

White (1)

Black (2)

American Indian/Native American or Alaska Native/First Nations (3)

Asian (4)

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander/Pacific Islander (5)

Hispanic (6)

Other (7)

Prefer not to say (8)

DQ04 Marital status

What is your current marital status?

Married (1)

Living with a partner (2)

Widowed (3)

Divorced/Separated (4)

Never been married (5)

Prefer not to say (6)

DQ05 Education

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

Some high school or less (1)

High school diploma or GED (2)

Some college, but no degree (3)

Associates or technical degree (4)

Bachelor’s degree (5)

Graduate or professional degree (MA, MS, MBA, PhD, JD, MD, DDS etc.) (6)

Prefer not to say (7)

Appendix II

– Structured comparison: MAiD laws in California and Canada